EUROPEAN COMMISSION

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Brussels, 20.7.2021

SWD(2021) 190 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

IMPACT ASSESSMENT

Accompanying the

Anti-money laundering package:

Proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on the prevention of the use of the financial system for the purposes of money laundering or terrorist financing

Proposal for a DIRECTIVE OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on the mechanisms to be put in place by the Member States for the prevention of the use of the financial system for the purposes of money laundering or terrorist financing and repealing Directive (EU)2015/849

Proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL establishing the European Authority for Countering Money Laundering and Financing of Terrorism, amending Regulations (EU) No 1093/2010, (EU) 1094/2010 and (EU) 1095/2010

Proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on information accompanying transfers of funds and certain crypto-assets

{COM(2021) 420 final} - {SEC(2021) 391 final} - {SWD(2021) 191 final}

Table of Contents

1Introduction: Political and legal context

2Problem definition

2.1What is/are the problems?

2.2What are the problem drivers?

2.2.1

Lack of clear and consistent rules

2.2.2

Inconsistent supervision across the internal market

2.2.3

Insufficient coordination and exchange of information among FIUs

2.3How will the problem evolve?

3Why should the EU act?

3.1Legal basis

3.2Subsidiarity: Necessity of EU action

3.3Subsidiarity: Added value of EU action

4Objectives: What is to be achieved?

4.1General objectives

4.2Specific objectives

5What are the available policy options?

5.1What is the baseline from which options are assessed?

5.2Description of the policy options

5.2.1

Strengthen EU anti-money laundering rules, enhance their clarity and ensure consistency with international standards

5.2.2

Improve the effectiveness and consistency of anti-money laundering supervision

5.2.3

Increase the level of cooperation and exchange of information among Financial Intelligence Units

6What are the impacts of the policy options and how do they compare?

6.1Strengthen EU anti-money laundering rules, enhance their clarity and ensure consistency with international standards

6.2Improve the effectiveness and consistency of anti-money laundering supervision

6.3Increase the level of cooperation and exchange of information among Financial Intelligence Units

7Preferred options

7.1Effectiveness

7.2Efficiency

7.3Coherence

7.3.1

General remarks on coherence

7.3.2

Coherence between the preferred options and other Commission policies

The draft regulation on crypto-assets provides a legal framework for crypto-assets and crypto assets services providers, including a definition of ‘crypto-assets’ and a list of recognised crypto-asset services that transposes in the EU law the recommendations of the Financial Action Task Force. Other provisions of the draft regulation on licensing and registration requirements, rules for supervision, preservation of financial stability and investors protection will be cross-referred in this legislative proposal.

7.3.3

Coherence between the preferred options and the EU data protection framework

7.4Summary of impacts of selected options

8REFIT (Simplification and improved efficiency)

9How will actual impacts be monitored and evaluated?

Annex 1: Procedural information

Annex 2: Stakeholder consultation

Annex 3: Who is affected and how?

1.Practical implications of the initiative

2.Summary of costs and benefits

Increased effectiveness of AML/CFT rules, consistent supervision across the internal market and efficient exchange of information among FIUs is the main objective of the initiative. This should reduce the quantity of illicit funds which are laundered or used to finance terrorism, either through greater detection or deterrence.

Preferred Options:

-Ensure a greater level of harmonisation in the rules that apply to entities subject to AML/ CFT obligations and the powers and obligations of supervisors and FIUs.

-Direct supervisory powers over selected risky entities in the financial sector subject to AML/ CFT requirements and indirect oversight over all other entities.

-The EU FIUs’ Platform to become a mechanism as part of the AML Authority, with power to issue guidance and technical standards and to organise joint analyses and training, carry out trends and risk analysis.

Annex 4: Evaluation

Annex 5: EU AML Authority: organisational institutional, resource and budget issues

Annex 6: Areas for greater harmonisation of rules

Annex 7: Interconnection of bank account registers

Annex 8: EU policy towards third countries with strategic deficiencies in their AML/CFT regimes

Annex 9: Introduction of cash limits

Glossary

|

Term or acronym

|

Meaning or definition

|

|

AI

|

Artificial Intelligence

|

|

AML

|

Anti-Money Laundering

|

|

AMLA

|

Anti-Money Laundering Agency/Authority (not yet in existence)

|

|

AMLD

|

Anti-Money Laundering Directive (Directive (EU) 2015/849 of 20 May 2015 on the prevention of the use of the financial system for the purposes of money laundering or terrorist financing, as amended by Directive (EU) 2018/843)

|

|

BO

|

Beneficial Owner (natural person who ultimately benefits from a registered company, often indirectly via a chain of companies)

|

|

CASP

|

Crypto Asset Service Provider

|

|

CDD

|

Customer Due Diligence

|

|

CFT

|

Countering the Financing of Terrorism

|

|

EBA

|

European Banking Authority

|

|

EDD

|

Enhanced Due Diligence

|

|

ESMA

|

European Securities and Markets Authority

|

|

Europol

|

European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation

|

|

FATF

|

Financial Action Task Force (international standard-setting body in the field of AML/CFT)

|

|

FIU

|

Financial Intelligence Unit (national enforcement body which receives STRs from OEs and forwards them, as appropriate to criminal investigation authorities)

|

|

GDPR

|

General Data Protection Regulation

|

|

HRTC

|

High Risk Third Country

|

|

KYC

|

Know Your Customer

|

|

ML

|

Money Laundering

|

|

OE

|

Obliged Entity (legal or natural person within the scope of AMLD and subject to AML/CFT rules)

|

|

SNRA

|

Supranational Risk Assessment

|

|

SRB

|

Self-Regulatory Body (e.g. bar association)

|

|

SSM

|

Single Supervisory Mechanism

|

|

STR

|

Suspicious Transaction Report

|

|

TF

|

Terrorism Financing

|

|

|

|

1Introduction: Political and legal context

Money laundering is the process through which proceeds of crime, their true origin and ownership, are changed so that they appear legitimate. Together with terrorism financing it represents an ongoing challenge to the integrity of the European Union (EU) financial system and the security of its citizens.

Combating money laundering and terrorist financing has been part of the European Union political agenda for over thirty years. In this time the EU has developed a regulatory framework, going beyond the international standards adopted by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), to prevent and manage the associated risks. This framework must continuously evolve to keep pace with growing sophistication of financial crime, technological developments allowing for new means to launder money and the increasing openness of the EU Internal Market.

The first EU anti-money laundering Directive (AMLD) was adopted in 1991. It applied only to financial institutions and focused on combatting the laundering of proceeds from drug trafficking. The AMLD has since undergone three major reforms (in 2001, 2005 and 2015) and substantial amendments in 2018. Today, it addresses the prevention of money laundering as a result of all serious criminal offences and lays down obligations for a number of non-financial activities and professions including lawyers, notaries, accountants, estate agents, art dealers, jewellers, auctioneers and casinos. The concept of beneficial ownership has been introduced to increase transparency of complex corporate structures, and enforcement follows a risk-based approach to focus resources where risks are the highest.

Since 2017, during the implementation phase of AMLD4 and AMLD5, a number of high-profile alleged money laundering cases have surfaced across the EU, involving billions of euro laundered through EU credit institutions or with the involvement of professionals and undertakings operating outside the financial sector, such as auditors, tax advisors and trust and company service providers. These prominent alleged cases revealed structural weaknesses of the current system. The limitations of the current framework were analysed and summarised in the July 2019 package of Commission documents concerning anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism, including a so-called ‘post-mortem’ report on alleged money laundering cases involving EU banks. The obtained evidence points to a fragmented, inconsistent and uncoordinated implementation and application of EU anti-money laundering rules. The 2019 Communication concluded that the problems identified were of a structural nature and could not be remedied by the most recent review of EU rules in this area (the 5th Anti-Money Laundering Directive of 2018).

This view is supported by the European Parliament and the Council. In its resolution of 19 September 2019, the European Parliament called for more impetus to be given to initiatives that could reinforce AML/CFT actions at EU level and for speedy transposition of EU rules by Member States. On 5 December 2019, the Economic and Financial Affairs Council (ECOFIN) adopted conclusions on strategic priorities for AML/CFT, inviting the Commission to explore actions that could enhance the existing framework.

In light of the priority that AML/CFT represent for the EU under the priority of the von der Leyen Commission “An economy that works for people”, the Commission presented on 7 May 2020 an Action Plan for a comprehensive Union policy on preventing money laundering and terrorism financing. The Action Plan sets out the measures that the Commission will undertake to better enforce, supervise and coordinate the EU’s rules on combating money laundering and terrorist financing, with six priorities or pillars:

1.Ensuring the effective implementation of the existing EU AML/ CFT framework,

2.Establishing an EU single rulebook on AML /CFT,

3.Bringing about EU-level AML/ CFT supervision,

4.Establishing a support and cooperation mechanism for FIUs,

5.Enforcing EU-level criminal law provisions and information exchange,

6.Strengthening the international dimension of the EU AML/CFT framework.

The first pillar is being implemented by the Commission’s ongoing transposition and compliance control of the existing AML/CFT rules. Since January 2020, when the most recent EU AML/CFT rules had to be transposed, the Commission has opened 23 infringement cases for non-communication or partial communication of transposition. In parallel, the Commission referred three Member States to the European Court of Justice and issued five reasoned opinions for incomplete transposition of the AML/CFT rules adopted in 2015. Four Member States received letters of formal notice for failing to correctly transpose such measures. Moreover, the Commission proposed in May 2020 that the Council issue recommendations on AML/CFT for eleven Member States under the European Semester exercise. The Commission has also requested the Council of Europe to carry out an assessment of the implementation of the current rules in Member States. Administrative letters have already been addressed to those Member States for which the assessment by the Council of Europe has been completed to follow up on any issues detected.Beyond these areas, enforcement action continues, with the actions covered by the Council’s 2018 AML Action Plan being almost fully completed, leading to better understanding and coordination among prudential and AML authorities in the financial sector. One of the key focus areas will be the reduction of divergences among Member States and the establishment of common rules that apply throughout the Union. In future, directly applicable rules in a Regulation will remove the need for transposition and reduce delays in the application of EU rules, whilst also freeing up resources for enforcement purposes.

However, better implementation of the current rules alone is not sufficient. In view of the nature of the identified problems, the current AML/CFT framework requires a reform that aims to ensure a more uniform implementation of the rules across the EU, by reducing the margin of interpretation left to Member States and by making the implementation and application of the rules more consistent across the internal market. This requires a structural change as well as introduction of new rules. To this end, the Action Plan contains a commitment to propose legislation in Q1 2021 to create a single rulebook, set up an EU-level AML/CFT supervisor, and to establish an EU coordination and support mechanism for FIUs, in all cases “based on thorough impact assessment of options”. This present impact assessment therefore focusses on pillars 2, 3, 4 and in part pillar 6 of the Action Plan.

In relation to the fifth pillar, the Commission will issue guidance and share good practices for the public-private partnerships between entities subject to AML/CFT obligations and public authorities. The sixth pillar, which is discussed in annex 8, concerns inter alia a more granular risk based approach by requiring obliged entities to apply enhanced customer due diligence to certain transactions with certain third countries. It also provides for a stronger role of the European Union in the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). As the global standard-setter in the AML/CFT field, the FATF develops recommendations to ensure resilience of the financial system against criminals trying to misuse it for money laundering, terrorist financing or proliferation financing purposes. These standards largely serve as inspiration for national AML/CFT legislation. More and more, EU standards are going beyond FATF standards, and in recognition of this the Action Plan advocates for a stronger role of the EU in the FATF to shape international standards.

The positioning of the co-legislators in favour of a bold reform of the EU AML/CFT framework, echoed by the vast majority of stakeholder that responded to the Commission’s public consultation, indicate that there is a clear understanding and willingness from all sides that the EU should do more in this area. On 4 November 2020, the ECOFIN Council adopted further Conclusions supporting each of the pillars of the Commission’s Action Plan. Such further action should address structural weaknesses of the EU AML/CFT framework and enhance its capacity to effectively counter money laundering and terrorist financing so as to reduce the exposure of our financial system to such risks and improving the functioning of the internal market.

While the current reform does not touch aspects pertaining to investigations and prosecutions of criminal cases, nor freezing/confiscation of criminal assets, the planned changes to the preventative framework will contribute to the quality and relevance of information provided to law enforcement authorities and increase the rate of transaction freezing in view of the opening of a case. It is however important to note that other factors outside the scope of this reform affect investigation and prosecution, including the prioritisation of money laundering cases by law enforcement and prosecutors and the effectiveness of national judicial systems (e.g. overload of cases).

The general principle of free movement of capital enshrined in Article 63 TFEU does not exclude that Member States and/or the European Union have a monitoring role on capital movements. Protection of citizens against activities for money laundering purposes is necessary and it has been long seen as one of the exceptions to the free movement of capital by the Court of Justice of the EU (the “Court”).

Box 1: How does the EU Anti-money laundering framework work?

Box 2: The architecture of the EU AML/CFT framework

This architecture comprises several private and public sector actors, tasked with specific but interrelated roles. The framework has a preventive and a repressing arm.

The AML/CFT preventive policy aims at the prevention of ML/TF by the setting of specific obligations for financial institutions and certain non-financial institutions and professionals. By virtue of their activity, these entities are well placed to intercept those transactions and operations that criminals need to carry out in order to conceal and integrate illegal money into the legitimate economic and financial environment. Therefore, such entities are subject to specific obligations. On the one hand, they are required to carry out customer due diligence to identify and verify the identity of customers and beneficial owners, to obtain information on the business relationship and to monitor it. On the other hand, they are obliged to report transactions in case they identify any suspicion. The scope and nature of these obligations is based on the intrinsic risk posed by clients, transactions and nature of the business relationship (risk-based approach).

National AML supervisors are tasked with ensuring compliance with these requirements. The intensity of supervision is based on the degree of risk that a given entity incurs. Supervisors have to make sure that entities’ internal controls and compliance procedures are commensurate to AML/CFT risk. National supervisors must cooperate with their counterparties in other jurisdictions for the supervision of cross-border entities.

In the financial sector, AML supervision in Member States is often concentrated in a single public authority. While AML supervision is always a distinct function from prudential supervision, a number of Member States have a single authority carrying out both types of supervision of some or all financial sector entities. In many Member States the Financial Intelligence Units have supervisory powers over at least some financial sectors. In a few Member States certain non-financial sectors are supervised by a self-regulatory body, such as the bar association.

Suspicious transactions are reported to Financial Intelligence Units (FIUs) FIUs are central national units, responsible for receiving and analysing information from private entities on transactions which are suspected to be linked to money laundering and terrorist financing, as well as for receiving cash-related data from customs authorities. FIUs exchange information amongst themselves by means of secure communication channels, such as FIU.net. They disseminate the results of their analyses to law enforcement and tax authorities for further investigations and prosecution where there are grounds to suspect money laundering, associated predicate offences or terrorist financing, and can order temporary freezing of transactions. FIUs provide feedback to private entities on effectiveness of and follow-up to reports of suspected ML/TF.

The AML/CFT repressive policy aims at punishing criminals through the application of criminal law and the imposition of measures such as seizure, definitive freezing of transactions and confiscation of assets. FIUs, Law Enforcement Agencies (LEAs) and judicial authorities play a prominent role. LEAs receive relevant information and analysis from FIUs and, if there are sufficient grounds, they can open a criminal investigation.

2Problem definition

2.1What is/are the problems?

Money laundering and the financing of terrorism pose a serious threat to the integrity of the EU economy and financial system and the security of its citizens. In September 2017, Europol warned that between 0.71 and 1.28% of the EU’s annual Gross Domestic Product is ‘detected as being involved in suspect financial activity’. In 2019 alone, this amounted to a value of between EUR 117 and 210 billion of suspicious activities and transactions occurring through the EU’s financial system and economy. Only a minor share of these suspicious transactions and activities are detected, with about 2% of assets seized and only 1% ultimately confiscated, allowing criminals to invest into expanding their criminal activities and, ultimately, infiltrate the legal economy. While this low rate of effectiveness is linked to a number of other factors such as prioritisation of investigations and duration of court proceedings, some shortcomings pertain to the preventive aspect of anti-money laundering, as discussed in the Commission’s 2019 Communication and 2020 Action Plan.

First, the application of AML/CFT rules across the EU is both ineffective and insufficient. The 2019 Commission ‘post-mortem’ report on the assessment of recent alleged money laundering cases involving EU credit institutions points to a number of deficiencies in the application of AML/CFT measures by the private sector. While these were sometimes the result of neglect or excessive risk appetite by private operators, the report also notes how they link directly to the lack of clarity in current EU rules, which leads to divergent application.

Useful insights into such divergences are provided by credit institutions operating in several EU countries. For example, following media revelations regarding its involvement in alleged money laundering cases, Swedbank commissioned a report from the law firm Clifford Chance to investigate its internal anti-money laundering measures, which it released in March 2020. The report notes for example how the different branches and business lines of Swedbank diverged in their assessment of the risks related to specific transactions, clients and products, resulting in different levels of scrutiny into (prospective) clients and the nature of the business relationship. This in turn led to inconsistent decisions regarding whether to open and maintain a business relationship and the identification and reporting of suspicious transactions and activities. As a result of these shortcomings, the report identifies payments worth EUR 37.7 billion carrying a high risk for money laundering that were made through Swedbank’s Baltic subsidiaries during 2014-2019.

The scope of the current rules is also ineffective in dealing with new threats arising from innovation. As Europol notes, the growing popularity and adoption of cryptocurrencies has also led to their increasing use in money laundering schemes. While the EU had paved the way internationally in imposing AML/CFT obligations on providers involved in the transfer between fiat currency and crypto assets, criminal schemes have evolved and are resorting to more complex solutions to launder money, going beyond the services currently covered by EU AML/CFT rules. The EU’s exposure to risks related to cryptocurrencies is confirmed in the Chainalysis 2020 Geography of Cryptocurrency Report, which notes that both Eastern and Northern/Western Europe have similar and substantial illicit cryptocurrency activity, and estimates that about 1 percent of Northern and Western Europe’s cryptocurrency activity is illicit. The report indicates that “both regions receive similar, high shares of all funds sent from addresses associated with darknet markets and ransomware attacks, [and they] are largely receiving these funds from the same specific criminal entities.”

Chainanalysis, 2020 Geography of Cryptocurrency Report

Finally, the current rules are ineffective in ensuring adequate protection of the EU’s financial framework while allowing legitimate transactions to take place. For example, the European Banking Authority (EBA) found that under the current framework, in the absence of a conviction or formal charge, there is no public authority that can act to stop a pay-out to a client even if there are indications that the failing credit institution was set up to facilitate money laundering. On the other hand, in another opinion EBA also found that a narrow focus on compliance with customer identification and verification requirements appears to have contributed to certain customers, in particular vulnerable ones, being excluded from access to and use of payment accounts with basic features.

This is also true in relation to supervisory activities. In the absence of an explicit link between ongoing supervision and ML/TF risk, not all supervisors consistently take ML/TF concerns into account, and when they do, not all act on these risks in a timely and effective manner. Such failure has been a major contributing factor to serious AML/CFT failures in recent years. Furthermore, there is uncertainty regarding the extent to which a prior sanction for AML/CFT breaches or a final decision of the supervisor identifying the AML/CFT breaches would be a precondition for a withdrawal of authorisation of a financial institution.

Second, insufficient oversight of how entities subject to AML/CFT rules apply them also affects the protection of the EU’s internal market and financial system from criminals. While legal obstacles to cooperation among national supervisors have been removed, the level of coordination is left to the individual authorities to decide, and has been limited so far due to a focus on national risks. As shown in the Commission’s post-mortem report, this has allowed criminals to turn these shortcomings to their advantage.

Example: Danske Bank

One example of the limits of such arrangements is the alleged money laundering case involving Danske Bank’s Estonian branch, where suspected payments worth EUR 200 billion were processed for non-resident clients between 2007 and 2015. The lack of cooperation between the Danish and Estonian supervisors in this case was revealed in a series of public statements by the two authorities. This affected their capacity to intervene to remedy the shortcomings in the bank. In fact, despite the regulatory measures taken since 2015, the remedies imposed did not prove sufficient and the Estonian AML/CFT supervisor had to order the bank to close its Estonian operations in 2019. While more recent cases have seen better cooperation between national AML/CFT supervisors, such a voluntary approach is insufficient to ensure that all entities implement in a coherent and effective manner common rules and are all subject to supervision of the highest quality.

The insufficient intensity of supervision is even more apparent in the case of entities subject to AML-CFT rules in the non-financial sectors. Data submitted for 2019 indicate that in a third of Member States no or close to no inspection was performed on accountants and tax advisors, lawyers or trust and company service providers. In some Member States, all these inspections were followed up by an instruction or remedial measure, while in other Member States no action was taken upon any inspection. The sanctions imposed vary significantly for the same group of professionals and breaches from one Member State to another (EUR 2 000 - 30 000). Overall, the intensity of supervisory measures remains insufficient to oversee adequate application of AML/CFT rules by these professionals, which continues to be lower than in the financial sector. Country A provides an example in this sense. In 2019, it performed twice as many inspections on financial institutions than on non-financial entities. Yet, twice as many breaches of AML/CFT rules were detected in the inspections covering the non-financial sector.

Furthermore, risk-based supervision is seldom applied when supervision is delegated to self-regulatory bodies (SRBs) with no or close to no public oversight over their work, as the examples below from Member States show.

Examples from Member States (anonymised) – supervision by self-regulatory bodies

Country B regulates the provision of trust and company services, which require registration and authorisation. Legal professionals are also authorised to operate as trust and company service providers under the supervision of the SRB. This service is considered more exposed to ML/TF risk but the SRB does not collect statistics to identify who are the professionals requiring more intense supervision.

In country C, the SRB does not keep data on the number of inspections where AML/CFT breaches were detected, nor of the instructions/warning issued following inspections. The SRB does not keep data on the aggregated number of high-risk costumers a professional would have either, as it considers this against the secrecy obligation.

In response to the public consultation, one national supervisor concluded that “the FATF MER process has demonstrated that the AML/CFT supervision of [the non-financial sector] is often of a lower standard than that of financial institutions. FATF has specifically stated that the supervision of CASPs should not be carried out by [SRBs] – this appears to be explicit recognition that the AML/CFT supervision by SRBs has not been of the expected or required standard”.

This results in a situation where the number of suspicious transactions or activities reported by these professionals, with the exception of gambling operators and notaries in some Member States is extremely low (e.g. for some professions, such as trust and company service providers, the number of suspicions reported is rarely above 20 and often in the single digit), and they might act as enablers that criminals exploit to launder money. For example, the Slovak FIU indicated that no notary or other professionals involved in the provision of company services reported any suspicions regarding the acquisition of companies or real estate in the country by the convicted Italian mafia member whom journalist Ján Kuciak was investigating prior to his murder. As such, the criminal’s investments in about fifty companies were allowed to go unnoticed, and only banks, not other entities such as accountants or real estate agents, reported suspicious transactions that involved him.

Third, insufficient detection of suspicious transactions and activities by Financial Intelligence Units (FIUs), particularly in cross-border cases, limits their capacity to suspend transactions and to disseminate relevant information to competent authorities and other FIUs quickly and effectively so that money laundering and where possible also the related predicate offences can be stopped. Despite the significant amount of suspicious reported to EU FIUs in 2019 (on average about 50 000 per FIU, but with significant divergences between them), less than half of them were actively followed up, and about 70 transactions were suspended on average (for an average total value of 60 million EUR). Extrapolating these averages to all FIUs, these figures indicate that, at best, the ratio between suspicious flows stopped at an early stage and estimated proceeds laundered within the EU is 1:100.

The number of suspicious transactions and activities reported by the private sector continues to grow since 2014. At the same time, the capacity in FIUs to cope with these volumes of data has not increased commensurately, and only a couple of FIUs reported to the Commission having witnessed substantial increases in their budget and staffing. Despite this, data submitted indicate that FIUs tend to analyse all suspicious transactions reported to them. This has an impact on a significantly increasing backlog, on the speed of their analysis and on their capacity to identify from this amount of data transactions of significance, which also affects the exchange of information between them.

The inadequate feedback from FIUs to private sector entities acting as obliged entities, in particular given the cross-border nature of many transactions, perpetuates this negative cycle. Indeed, only in a minority of cases did the FIUs report providing elaborate feedback on trends and typologies in money laundering tailored to specific categories of obliged entities. Left without information on trends in money laundering and terrorism financing, private sector entities are unable to detect those activities and transactions that are genuinely suspicious and to improve the quality of the information reported. As such, reporting has become an automated process, leading to an increase in reports of no significance (the so-called ‘false positives’). Indications confidentially provided by credit institutions to the Commission estimate that between 50% and 75% of reports submitted to FIUs would fall under this category. The sector also shared that based on existing studies the level of false positives could be even higher, as shown in the graphs below which point to around 10% of all STRs submitted as being of use.

Usefulness of SARs and false positives - sources: Europol and PWC

This results in deviation from the objective of detecting suspicious criminal activity and in a failure to implement the risk-based approach on which the AML/CFT framework is based. In many cases, only 1 in every 10 suspicions reported to the FIU is subject to an analysis shared with law enforcement authorities, although important divergences exist among FIUs based on the dissemination practices in place in each of them.

Feedback to other authorities is also insufficient. Every year, customs administrations receive around 100 000 cash declarations and detect around 12 000 cases where there was a failure to the obligation to declare cash above the threshold of EUR 10 000 when crossing of the EU external border. This information is reported to the FIUs but only seldom do customs administrations receive feedback. This is confirmed by the FIUs, but the very limited feedback is rather linked to an absence of obligation in the legal framework to provide any feedback on these reports to customs authorities. However, this feedback is particularly important in the case of infringements of the obligation to declare such sums. According to the above-mentioned Europol report, 38% of the suspicious transactions reported originate in cash-related data.

These three problems interact with one another to create a situation that continues to provide an economic lifeline for criminals. This allows them not only to jeopardise public security, but also to infiltrate the legal economy to obtain extra gains, with detrimental effects on welfare and public resources, including EU funds. These weaknesses also impact the soundness and reputation of the EU’s financial system, as some EU banks have had to terminate all or part of their business. From a broader economic perspective, as the International Monetary Fund notes, money laundering discourages foreign investment, which might in turn slow down the economic recovery following the COVID-19 pandemic.

At the same time, the current AML/CFT framework can impinge on the provision of services. Recent cases where financial institutions chose to de-risk by ceasing to offer certain services instead of managing the risks associated with certain sectors or customers have affected economic investments in some Member States and, as noted by several stakeholders including the European Banking Federation, might also obstruct financial inclusion.

2.2What are the problem drivers?

Three problem drivers are directly relevant for the initiatives to which this impact assessment relates, and are described in greater detail below.

2.2.1Lack of clear and consistent rules

The current EU AML/CFT legislation centres around an anti-money laundering directive (AMLD), which provides a comprehensive regulatory environment to prevent and combat money laundering and terrorism financing. However, the lack of clarity, and limited nature, of some of the rules adopted at EU level, combined with different approaches in gold-plating, have resulted in diverging implementation of the EU legal framework across Member States and across obliged entities.

These divergences encompass a wide array of provisions. Regarding the scope, that is natural and legal persons that are subject to AML/CFT requirements, some have gone beyond the list in the Directive in different ways to cover crowdfunding platforms (Lithuania), the administrator of the emission trading registry (Czech Republic) or the administrator of the companies register (France). While in some cases specific risk situations might justify national divergences, the examples above are entities that share comparable risk levels across the EU, but which as a result of divergent approaches have not been consistently subjected to AML/CFT rules.

Unclear EU rules also lead to uncertainty as to how AML/CFT requirements must be applied by the private sector. This is exemplified in the report investigating alleged money laundering through Swedbank’s Baltic subsidiaries by Clifford Chance.

Example: Swedbank

Employee A: “[i]t is ludicrous to create separate KYC functions or banks in each Swedbank entity. It is not required by local law and is not required by the [supervisor, the] FSA (they would have said so if anyone would have bothered to ask them).”

Employee B: “AML Manual is clear that our Baltic colleagues are requested by the local FSA to conduct their own KYC and independently come to a conclusion if they want to run a relationship or not.”

Employee C: “[Swedbank and the Baltic subsidiaries] are separate legal entities and the relevant FSAs require a risk assessment of the customers by the relevant entity.”

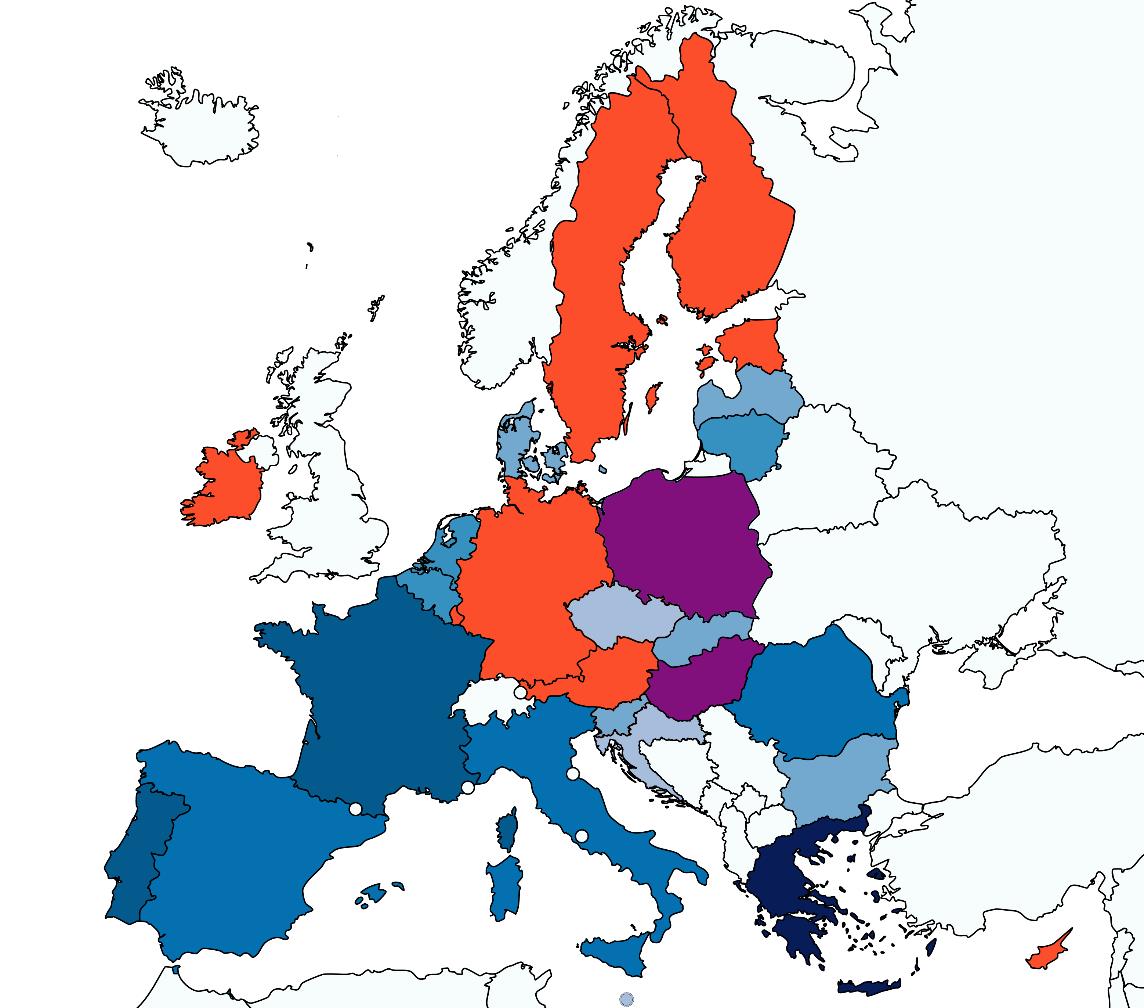

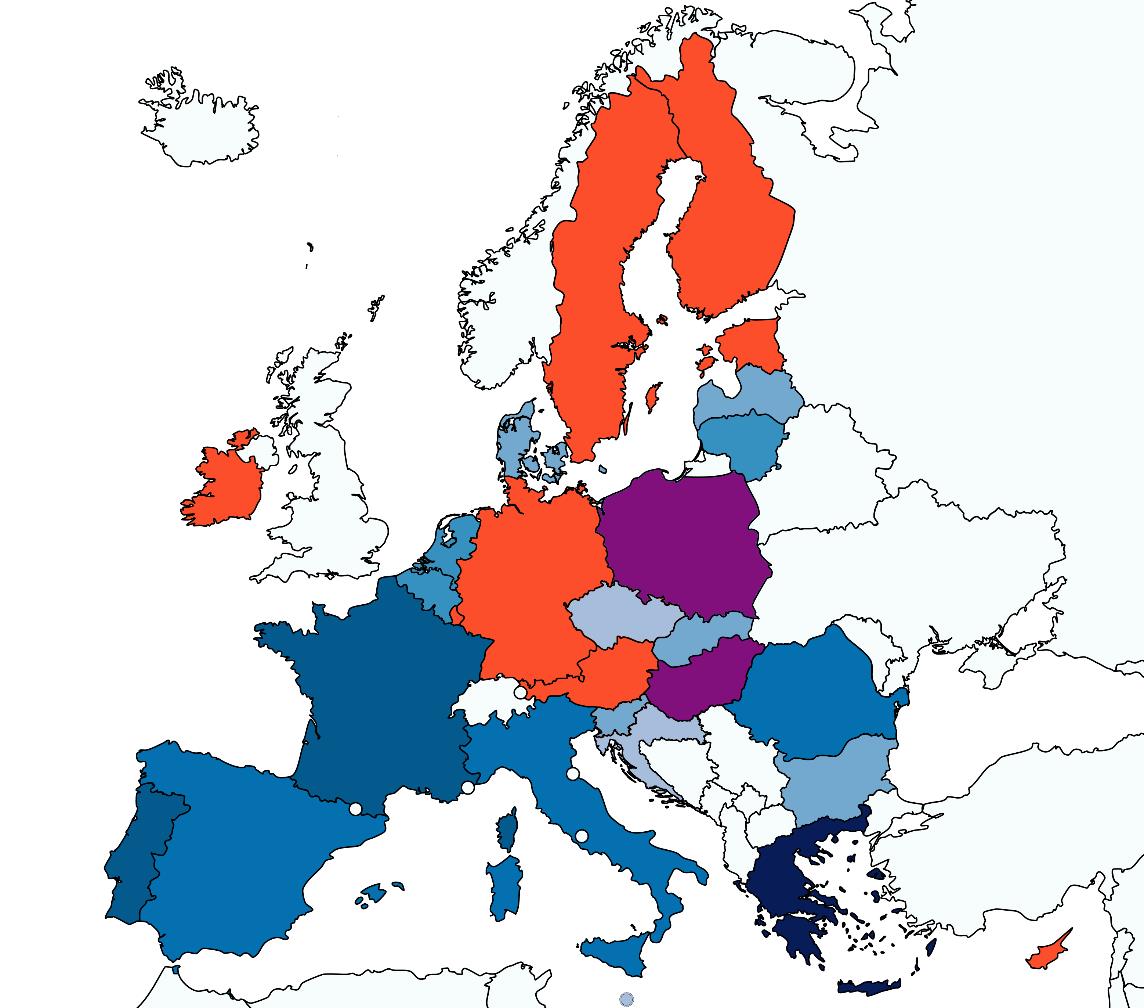

Further, the degree of transparency imposed by Member States regarding the beneficial ownership of companies and trusts often goes beyond the minimal requirements of the Directive, resulting in variation. While the majority of Member States have imposed a threshold of holding 25% of shares in a company to be entered into the register of beneficial owners, only two countries (Latvia and Spain) have opted for a lower threshold of 10% in order to enhance the transparency of corporate ownership. Current rules are subject to divergent interpretations, and result in different methods to identify beneficial owners of a given legal entity due to inconsistent ways to calculate indirect ownership. Below is a graphic example that compares the rules in three different Member States.

As shown, the application of the relevant national rules leads to inconsistent results as to which person or persons are considered to be the beneficial owner(s) of the same legal entity. This creates serious problems in terms of transparency and hampers the ability to spot potential suspicions in one Member State as compared to another.

A further prominent case of inconsistent rules concerns the identification of obliged entities, with specific regard to the example of crowdfunding platforms, mentioned above. Some national legal systems impose AML/CFT rules also to crowdfunding platforms, which are then subject to supervision and face specific requirements such as mandatory registration and transparency obligations. However, in the majority of Member States such entities are not supervised and regulated for AML/CFT purposes. This national approach is particularly inadequate considering that, as recognised by the Commission’s 2019 Supranational Risk Assessment, crowdfunding platforms present risks and vulnerabilities that are horizontal and that affect the internal market as a whole. An inconsistent identification of such platforms is not justified by the presence of local risks that characterise only specific national realities, and leads to inability of the AML/CFT framework to monitor anonymous cross-border financial flows which are typical of such platforms.

The powers of national AML/CFT supervisors also vary significantly. The Bank of Italy (the AML/CFT supervisor for the financial sector in Italy) has the power to issue all ranges of administrative sanctions, and has gone beyond the sanctions towards natural persons set out in the AMLD (i.e. 5 million EUR), when the benefit is higher (sanction is at most twice the amount of the benefit obtained). On the other hand, Estonia is in the process of increasing the administrative sanctions that can be imposed by its financial supervisor, which are deemed too low. In the non-financial sector, the Irish Ministry of Justice can issue instructions to comply or revoke authorisations, but has no power to issue administrative sanctions. Similarly, the Danish supervisors of legal professions have no power to issue pecuniary sanctions on supervised professionals.

Similarly, not all FIUs share the same powers. Some FIUs, such as the Finnish and Greek FIUs, have been granted administrative powers to freeze assets for a certain period of time in view of a judicial freezing order in the context of a criminal investigation. While all FIUs have powers to issue requests for information to professionals subject to AML/CFT requirements, the timeframe for responding to such requests varies significantly across Member States, from 5 to 20 working days. Due to their varying status, not all FIUs are able to access directly and share swiftly all relevant information (financial, administrative and law enforcement information). Moreover, the 2016 Mapping exercise on FIUs’ powers and obstacles to exchange and access information and the 2019 Commission report assessing the framework for cooperation between FIUs demonstrated that there are problems linked to the timeliness of replies to requests, as some FIUs indicate that they reply to requests from other FIUs within one month on average, which is far longer than the average time for exchange of information between authorities under other EU instruments with detrimental effect on the effective use of such information and the adoption of measures where needed. EU law does not impose any deadlines for the exchange of information between FIUs.

In addition, current rules do not provide for an EU-wide interconnection of the centralised bank account registries. The 2019 Commission report assessing the technical feasibility of such interconnection confirmed that this would be possible. These registries allow the identification of any natural or legal persons holding or controlling payments accounts, bank accounts and safe deposit boxes and as the 2019 report notes will be an important component in the fight against money laundering, associate predicate offences and terrorist financing. The lack of interconnection of centralised bank account registries hampers timely access to bank account information and cross-border cooperation among FIUs as well as AML/CFT competent authorities.

Finally, some Member States have taken measures to deal with the specific risks posed by cash by setting ceilings for large cash payments, whereas others have not. The 2019 SNRA concluded that the money laundering vulnerability of payments in cash is very high (the highest threat level). This is due to a number of facts, among which the large sums that can be engaged speedily and anonymously, including across borders, exposure across all sectors and low level of risk awareness. The current rules which provide for the application of AML/CFT measures to traders in goods for transactions of or above 10 000 EUR have not achieved the expected results. This is partly because of no framework/controls in place, or because enforcement of the controls is not efficient. Even where controls are in place, the transactions reported do not allow triggering a sufficient level of suspicion that would allow producing financial intelligence for the support of investigations.

EU rules are not only transposed and applied in a divergent manner, they are also not fully consistent with the latest international standards that have evolved since the latest amendment to the AMLD, as they fail to include all crypto assets service providers among the professionals who must apply AML/CFT requirements and are not adapted to the risks stemming from innovation. The lack of coherence with international standards also covers the traceability of the crypto assets transfers and the information sharing obligations between crypto assets services providers, as current EU rules, as laid down in Regulation (EU) 2015/847 only identified funds as “banknotes and coins, scriptural money and electronic money”, but not crypto assets. In their recent joint opinion, the EU supervisory authorities identified specific risk-increasing factors in respect of new business models and products (i.e. fintech), first of which is the provision of unregulated financial products and services that do not fall within the scope of AML/CFT legislation.

Lack of clarity also exists in the interplay between AML/CFT rules and other sectoral legislation. The EBA recently identified the lack of explicit provisions regarding such interplay as a key source of the ineffective application of AML/CFT rules by supervisors and entities subject to AML/CFT supervision alike. In its 2019 Opinion on deposit guarantee scheme pay-outs, the EBA identified gaps in the EU legal framework that have contributed to the adoption of divergent approaches by Member States to such pay-outs in situations where ML/TF concerns exist. Similarly, the lack of harmonised customer due diligence provisions has led to situations where Member States have transposed the Payment Account Directive and AML/CFT rules in a way that may prevent the application of a risk-based approach and result in denial of access to a basic payment account.

The consequence is an insufficient and ineffective application of AML/CFT obligations that fails to adequately prevent criminals from exploiting the EU’s financial system to launder the proceeds of their illicit activities.

2.2.2Inconsistent supervision across the internal market

AML/CFT supervision within the EU is currently Member State-based. Its quality and effectiveness are uneven, due to significant variations in resources and practices across Member States. In some cases, the variations cover the human and financial resources devoted to it. For example, only ten staff members are tasked with supervising compliance with AML/CFT rules by the financial sector in Finland as opposed to 27 staff members in Austria, despite financial sectors of a similar size and the presence in both countries of significant financial groups. In the non-financial sector, Belgium and the Netherlands allocated more than 10 staff members to the supervision of real estate professionals, whereas Croatia allocated 1 person to this task and Germany indicated having allocated 15 persons to the supervision of the whole non-financial sector (about 1 million entities).

As recent cases of alleged money laundering involving EU credit institutions show, the approach to cross-border situations is not consistent. The EBA’s recent report on approaches of competent authorities to AML/CFT supervision confirmed that despite progress, not all competent authorities are able to cooperate effectively with domestic and international stakeholders.

The methods to identify risks and to apply the risk-based approach to supervision also diverge. While some risks remain national in nature, others are of horizontal nature or may impact the entire Union financial system. Member States stressed the need for a common, consistent methodology to assess and identify risks in reply to the targeted questionnaire circulated by the Commission as part of the public consultation launched when adopting the Action Plan on 7 May 2020.

In addition to the divergences in supervisory powers already described, the EBA also notes that national AML/CFT supervisors might not always be willing to use the full set of powers available.

Excerpt from EBA report:

These challenges included translating theoretical knowledge of ML/TF risks into supervisory practice and risk-based supervisory strategies; shifting from a focus on testing compliance with a prescriptive set of AML/CFT requirements to assessing whether banks’ AML/CFT systems and controls are effective, and taking proportionate and sufficiently dissuasive corrective measures if they are not.

This leads not only to inadequate supervision at national level, but also to insufficient supervision of professionals providing services across borders, which create risks for the whole Single Market.

2.2.3Insufficient coordination and exchange of information among FIUs

FIUs serve as national centres for the receipt and analysis of suspicious transaction reports by the private sector and all cash-related data from customs administrations and other information relevant for the detection of money laundering and financing of terrorism. The results of such analyses should be consistently disseminated to other FIUs and competent authorities to investigate cases, inform supervisory activities and allow other measures (e.g. by tax authorities) to be taken.

Most FIUs have developed their own reporting templates and methods to identify suspicious activities and while a common template has been developed by the FIU Platform, it is not binding. As a result, the nature and extent of the information collected by FIUs is not always comparable.

Even when the reports have a comparable content, the non-binding nature of the existing template results in a situation where not all EU FIUs use it. This makes the information contained in the report hardly recognisable or usable in timely manner by other FIUs, which hinders effective actions to identify and tackle potential cross-border money laundering or related predicate offences including tax crimes as well as terrorist financing activities. Performing joint analyses also becomes difficult when reports and the approach to analysing them differ substantially. Indeed, while 8 FIUs indicated using GoAML, a reporting system developed by the United Nations, 11 indicated that they have put in place their own reporting system, whether based on IT systems or analogic (e.g. fax). Similarly, when it comes to analysing these reports, 11 FIUs indicated that they do this without support from IT tools, 11 FIUs have an IT tool at their disposal to support the analysis, while only 4 FIUs indicated resorting to Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools (2 FIUs are in a testing phase).

Data shared by FIUs also reveals the absence of a common approach to data sharing. While almost all FIUs used the available tools such as FIU.net to disseminate reports, analyses or to request information, the use of more advance tools such as matching techniques was less widespread. The figures show significant variation in the amount of information exchanged. For example, FIU A shared 200 analysis, while FIU B shared 6. Behind the overall numbers, divergences exist in terms of what is shared (whether it is the report as submitted by the obliged entity itself or rather the analysis performed by the FIU) and when it is shared (e.g. automatically when the report contains a reference to a Member State or only when that report is relevant).

All recent major money laundering cases reported in the EU had a cross-border dimension. The detection of these financial movements is however left to the national FIUs and to cooperation among them. While this reflects the operational independence and autonomy of FIUs, the absence of a common structure to underpin this cooperation leads to situations where joint analyses are not performed for lack of common tools or resources. Indeed, only half of the FIUs indicated they use the current tools to build joint cases. Moreover, exchanges of practices and mutual learning remains marginal (only 5 FIUs reported having engaged in trainings with other FIUs), and in a number of cases FIUs have turned to the private sector to receive the kind of training that another FIU with experience in the field (e.g. trends in the misuse of corporate vehicles) would have been best placed to provide.

These divergences hamper cross-border cooperation, and thereby reduce the capacity to detect money laundering and terrorism financing early and effectively. This results in a fragmented approach that is exposed to misuse for money laundering and terrorist financing and that cannot timely identify trends and typologies at Union level.

2.3How will the problem evolve?

Unless the EU adopts a new, comprehensive approach to preventing money laundering and terrorism financing that tackles the identified problem drivers, the EU economy and financial system will remain exposed to risks. While the current tools have gone a long way towards tackling these risks, they are not sufficient to address problems that due to a fast evolving context have become structural in nature.

Recent decisions by credit institutions to exit some markets and interrupt correspondent banking services provide an indication that any failure to act at EU level to ensure consistent application of the rules might have negative effects on legitimate business. At the same time, there is no indication that de-risking brings benefits in terms of preventing money laundering or terrorist financing, as laundering techniques continuously evolve. The private sector often lacks information on new trends to apply a smart approach that could differentiate suspicious activities from legitimate ones.

As Europol notes, money laundering risks are likely to increase during the recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. The volatile economic situation will make the EU financial system, as well as sectors such as real estate and cash-intensive businesses, particularly exposed. In the longer term, laundering techniques are likely to become more sophisticated and involve an increase in the use of shell companies, trusts and trade-based money laundering. Without a consistent response by the private sector, supported by adequate supervision, the EU AML/CFT framework will be unlikely to resist such attempts. This presupposes an understanding of the risks, which the current level of feedback by FIUs and cooperation among all authorities cannot grant.

New threats accompanying innovation in financial services will also appear. As Europol notes, “[a] growing number of online platforms and applications offer new ways of transferring money and are not always regulated to the same degree as traditional financial service providers. This makes money laundering a technical challenge for law enforcement authorities to investigate”. In the absence of specific obligations on providers of such services to apply AML/CFT measures and to report any suspicious transactions or activity, criminals will continue laundering their illegal proceeds through these systems undetected.

For these reasons, the AML/CFT legislative framework will need periodic updating and amendment, at least as regards the scope of Obliged Entities which are covered, and possibly other aspects of rules. Such updating can be facilitated by certain elements of the selected options described in sections 6 and 7 below, including directly applicable key rules and the existence of an EU AML/CFT Authority which can provide analyses and guidance on an ongoing basis. It is however anticipated that the basic institutional and legislative framework provided by the present package of proposals, if not always the detailed rules, will be “future proof” in the face of evolution in the practices of money launderers and financers of terrorism.

PROBLEM TREE

3Why should the EU act?

3.1Legal basis

The legal basis of most parts of this the initiative, like previous initiatives in the area of AML/CFT, will be Article 114 TFEU, which allows the legislator to adopt rules in order to achieve the objectives announced in Article 26 TFEU and aims at ensuring the proper functioning of the Internal Market. Article 114 TFEU provides a legal basis for the approximation of national laws with the final objective of ensuring the proper functioning of the internal market. As held by the Court in its judgement in Case C 58/08 Vodafone and others, the resort to Article 114 TFEU is justified where there are differences between national rules which have a direct effect on the functioning of the internal market. Equally, the Court held, that where an act based on Article 114 TFEU has already removed any obstacle to trade in the area that it harmonises, the Union legislature cannot be denied the possibility of adapting that act to any change in circumstances or development of knowledge having regard to its task of safeguarding the general interests recognised by the Treaty.

The situation as presented in the problem definition confirms that these divergences are actual and current and have a direct effect on the functioning of the internal market and experience with the current AMLD framework has shown weaknesses that justify being addressed. This justifies the adoption of clearer rules to avoid such differences. Similarly, the development of national AML/CFT laws aimed at integrating international recommendations in relation to crypto assets is likely to lead to the emergence of new obstacles to trade, which the Court also held as justifying the adoption of measures under Article 114 TFEU. EU action is needed to prevent the emergence of such new obstacles and the proposed measures must be designed to do so.

Finally, the Court held that the measures for the approximation covered by Article 114 TFEU are intended to allow a margin of discretion, depending on the general context and the specific circumstances of the matter to be harmonised, as to the method of approximation most appropriate to achieve the desired result. As explained in the problem definition, the existing issues are of a structural nature and require measures that aim at introducing EU-level structures in support of national ones.

In light of the above, and in respect of the jurisprudence of the Court, the aim of this initiative is to provide a harmonised approach to strengthening, taking into account experience, the EU’s existing AML/CFT preventive framework by reducing divergences in national legislation and by introducing structures that would deliver a real harmonization effect, thus allowing effective implementation of the framework.

As noted in Annex VII, the extension of access to interconnected bank account registers to law enforcement authorities will have to have as legal base article 87(2) of the Treaty, the same legal basis as for Directive 1153/2019, which extended access to domestic bank account registers to national law enforcement authorities. That is the only element of the present package concerning law enforcement as opposed to upstream prevention or detection of money laundering and terrorist financing.

3.2Subsidiarity: Necessity of EU action

The current fragmentation of rules and their implementation framework has resulted in weak links in the EU anti-money laundering framework. The alleged money laundering cases that involved EU credit institutions and professionals since 2018 show significant cross-border dimensions that cannot be sufficiently addressed though the minimum harmonisation provided by AMLD.

As the previous section shows, the issues are of a structural nature and cannot be remedied by Member States acting alone. An ineffective AML/CFT framework in one Member State or differences between rules across Member States, may be exploited by criminals and have consequences for other Member States. Member States alone cannot ensure consistent integration of the latest international standards in the EU framework, nor increased consistency with other EU rules to the extent needed to solve the problems identified.

Member States acting alone are also not able to ensure the consistency of rules and their supervision across the EU. This affects the capacity of Member States to protect the integrity of the internal market, but also the ability of companies to operate freely or for customers to easily contract financial services across borders.

Action by Member States alone is not sufficient to ensure effective coordination and exchange of information among FIUs to identify cross-border transactions and activities that are susceptible to be connected to money laundering and terrorist financing.

It is therefore important to act at EU level. This has been recognised in the five previous iterations of the AML Directive, and is still the case as regards this legislative package.

3.3Subsidiarity: Added value of EU action

The actions needed to address the problems set out in chapter 2 can be better implemented at Union level. This would improve the robustness of the EU’s AML/CFT framework and help reduce the fragmentation of measures taken to address money laundering and terrorism financing risks. It would also avoid implementation of unilateral measures and conflicts in legislation between Member States, in line with the objective of Article 114 TFEU and existing case law.

It would also ensure a more effective and coherent implementation and enforcement. Individual national solutions are likely to lead to conflicting outcomes when confronted with the free movement of capital inherent to the internal market. A multiplication of national rules would also make it disproportionately difficult for professionals to provide services across borders.

The replies provided to the public consultation confirm that EU action in this area is likely to deliver better outcomes than Member States action in that it would deliver a real harmonization effect to close the loopholes that currently expose the EU’s financial system and economy to money laundering and terrorist financing. Of all options available for taking further steps to fight money laundering and terrorist financing, respondents considered that action at EU level was likely to be the most effective, and also the least likely to be ineffective.

4Objectives: What is to be achieved?

4.1General objectives

The general objective is to achieve a comprehensive AML/CFT framework that will adequately protect the EU’s economy and financial system from criminal infiltrations, as well as to ensure public security. Such a framework should be flexible enough to adapt to the evolving nature of the threats, risks and vulnerabilities facing the EU. It should approach risk in a smart manner to reduce negative effects on economic activity or citizens’ right to privacy and protection of personal data to what is absolutely necessary and proportionate.

4.2Specific objectives

This general objective translates into three specific objectives:

-Strengthen EU anti-money laundering rules and enhance their clarity while ensuring consistency with international standards and other EU legislation;

-Improve the effectiveness and consistency of anti-money laundering supervision, and

-Increase the level of cooperation and exchange of information among Financial Intelligence Units.

5What are the available policy options?

5.1What is the baseline from which options are assessed?

The baseline scenario coincides with the first pillar of the Commission’s Action Plan effective application of existing rules, i.e. the EU anti-money laundering framework consisting of the current Directive and the Wire Transfer Regulation. The former would be transposed by Member States, with possible significant delays. The Commission would monitor such transposition and would open infringement proceedings in case of incomplete or incorrect transposition. However, the Commission would have no power to reduce divergences among Member States. The rules would indeed remain subject to broad margins of interpretation by Member States, due to the lack of detail. Thus, the fragmented application of EU rules and divergent national standards would persist. The Commission would use the European Semester exercise to identify situations where the effectiveness of national anti-money laundering frameworks needs improving, but would only be able to propose non-binding recommendations. The current inconsistencies between anti-money laundering rules and other EU legislation would continue to exist.

Supervision would continue to be fragmented, with national competent authorities solely responsible for ensuring compliance with AML requirements by private sector entities within their national jurisdictions. For entities that operate on a cross-border basis, multiple supervisory authorities would remain involved in supervision, based on a strict home-host distribution of supervisory responsibilities. The European Banking Authority would continue to perform a coordinating role. In the financial sector, EBA would continue to fulfil its current mandate in the area of AML/CFT, specifically with regard to: 1) harmonisation of the regulatory requirements for supervisory policy approaches by means of issuing binding technical standards, guidelines and recommendations; 2) promoting convergence in supervision by, inter alia, conducting peer and staff reviews of national competent authorities; 3) facilitating cooperation and information exchange between national competent authorities by establishing and hosting a data hub and participating on the work of AML colleges; 4) contributing to effective enforcement of Union law using all the tools at its disposal for that purpose, including, where necessary, breach of Union law powers. However, EBA’s governance structure might make it difficult to take action against a national supervisor which is ineffective in enforcing the rules.

The FIUs would continue to provide advice and expertise to the Commission on operational issues, and to exchange information on cooperation-related issues in the context of the current informal EU FIUs’ Platform. However, matters pertaining to international cooperation, the identification of suspicious transactions with cross-border dimension, the use of IT tools such as the FIU.net system and the adoption of common templates or performance of joint analyses would be on an individual, voluntary basis. Trends in money laundering and terrorist financing would also be discussed, but there would be no tool available to go beyond exchanges of views and of information. Thus, the current shortcomings of the framework for exchange of information and cooperation between FIUs would continue to exist and affect negatively their ability to detect and prevent money laundering and the financing of terrorism.

5.2Description of the policy options

5.2.1Strengthen EU anti-money laundering rules, enhance their clarity and ensure consistency with international standards

Option 1:

EU rules would remain as they are with no modifications

Option 1 would constitute the baseline scenario described above in Section 5.1.

Option 2:

Ensure a greater level of harmonisation in the rules that apply to obliged entities and leave it to Member States to detail the powers and obligations of competent authorities

Under this option, a number elements of the current framework that apply to entities subject to AML/CFT obligations would be made more consistent across the EU by more detailed rules, in a directly-applicable Regulation, while remaining in a minimum harmonisation system which allows Member States to go beyond. The logic of such an intervention is to carry out a structural reform of the rules with the aim to reduce the margins of interpretation that Member States have today. This would be achieved by detailing the current rules in a coherent way across the EU. This reform would address needs that are different in nature from those that led to the 5th AMLD. The latter, indeed, was adopted for the purpose of updating the framework in view of the FATF standards and to go beyond them (however, since then new FATF standards regarding CASPs have been adopted, which need to be incorporated into the EU framework). On the contrary, under option 2 and 3 (see below), this reform would not seek to introduce major new rules, but essentially to restructure and detail the current ones to ensure a coherent implementation across the EU.

Under Option 2, as stated above, this harmonisation would not concern all the current rules, but only key elements of those applicable to obliged entities. One example of such an element is the measures related to customer due diligence (CDD). In this regard, a homogeneous approach would be ensured in required procedures to identify and verify customers and beneficial owners, as well as in relation to the monitoring of transactions and business relationships and the related reporting obligations in case of suspicion. Harmonisation would also concern simplified and enhanced CDD measures to be adopted in lower/higher risk scenarios. This would include an adapted policy towards third countries to bring about a greater degree of granularity in definition of mitigating measures. Further, this option would cover rules applicable to reliance on third parties for the performance of CDD and to internal controls that entities subject to AML/CFT controls must have in place, including data protection requirements. Provisions regulating the use of digital identities for digital customer identification and verification would also be included. Such rules, however, could still be sufficiently flexible for the specific purpose of accommodating a risk-based approach at the level of obliged entities, in line with international standards, and leaving scope for adopting specific rules to go further, with a high level of granularity. This could be achieved through regulatory technical standards to be developed by the EU AML Authority (see discussion of other problems).

Also, under this option a consistent approach would be introduced to the beneficial ownership (BO) transparency regime. This would include making sure that the same information is collected on beneficial owners of legal entities and legal arrangements across the EU, and that the same parameters are used for the definition of beneficial ownership. Moreover, consistent rules on the collection and storing of BO information in central registers would be put in place.

This option would also include interconnection of bank account registers for AML/CFT authorities, as discussed in more detail in Annex 7, which considers the main policy options available, i.e. interconnection of the bank account registers and access to them by FIUs only or interconnection of the bank account registers and access by FIUs as well as other competent authorities, namely those covered by Directive (EU) 2019/1153. Options regarding the introduction of limits to large cash transactions are discussed in more detail in Annex 9. Those are: keeping the status quo by relying on traders in goods while allowing Member States to define stricter rules, introduce an upper EU-wide limit for large cash payments while allowing Member States to adopt stricter limits at national level or introducing an EU-wide harmonised limit to large cash payments.

Furthermore, this option would entail the adoption of a more harmonised list of obliged entities across all Member States. In line with the risk-based approach that lies at the basis of the AML/CFT system, the new rules would also provide a mechanism to allow Member States to add other entities, if evidence shows this is necessary in order to address specific risks at national level. This option would also address the relationship with other EU laws interacting with AML rules (see section 7.3 below).

Among the obliged entities to be added, in addition to crowdfunding platforms (see annex 6), there is the need to introduce important categories of crypto assets services providers recently covered by the FATF standards. FATF also recommends to introduce harmonised EU processes to share information on crypto assets transfers, both between crypto assets services providers at the two ends of such transfers (beneficiary and originator crypto assets services providers), but also by keeping this information available for competent authorities.

Areas proposed for a greater level of harmonisation under option 2

·Customer Due Diligence (CDD) ;

·list of obliged entities;

·beneficial ownership transparency regime;

·central registers for bank accounts – providing the legal basis for the interconnection at Union level;

·Limits to large cash transactions

·AML/CFT systems and controls, including governance arrangements;

·Suspicious Transaction Reporting;

·occasional transactions;

These are the main areas for greater harmonisation; Annex 6 discusses in more detail all the areas proposed for improved harmonisation.

Option 3:

Ensure a greater level of harmonisation in the rules that apply to entities subject to AML/CFT obligations and the powers and obligations of supervisors and FIUs

This option would include the elements covered by option 2 and, in addition, it would provide for greater consistency also with regard to the powers and obligations of AML/CFT supervisors and Financial Intelligence Units. The legislative proposal would lay down minimum common rules covering the performance of key supervisory tasks such as the risk categorisation of obliged entities, the obligation to perform sectorial risk assessments, minimum rules for on-site supervisions, as well as minimum powers that AML supervisors should have. The rules would also cover operational aspects of cooperation among national AML supervisors, as well as the cooperation with a possible EU AML supervisor, if appropriate (see section 5.2.2. below. Consistency across the EU would also be introduced concerning the circumstances, the criteria and the thresholds for application of administrative sanctions by supervisors towards obliged entities in case of breach of AML/CFT obligations. Furthermore, an obligation would be introduced in line with FATF standards to ensure that when AML supervision is performed by self-regulatory bodies such as bar associations, they are themselves subject to supervision by a public authority. As regards FIUs, this option would involve defining their core tasks in relation to the production and dissemination of financial intelligence and a minimum set of powers (e.g. powers to freeze a transaction). Moreover, this option would allow enhanced cooperation with other competent authorities such as customs and tax authorities (for example, FIUs could be obliged to share with tax authorities information about large undeclared cash movements into the EU).

Areas proposed for a greater level of harmonisation under option 3 (more details in annexes 6, 7 and 9)

·Customer Due Diligence (CDD) ;

·list of obliged entities;

·beneficial ownership transparency regime;

·AML/CFT systems and controls, including governance arrangements;

·Suspicious Transaction Reporting;

·occasional transactions;

·tasks and powers of supervisors and FIUs;

·operational cooperation between relevant national competent authorities;

·administrative sanctions – criteria and thresholds;

·central registers for bank accounts – providing the legal basis for the interconnection at Union level;

·limits to large cash transactions.

5.2.2Improve the effectiveness and consistency of anti-money laundering supervision

Option 1:

Anti-money laundering supervision would continue to be performed at national level, with the European Banking Authority in charge of overseeing this supervision in the financial sector

Option 1 would constitute the baseline scenario described above in Section 5.1.

Option 2:

Establish indirect oversight over all obliged entities

Similarly to the baseline scenario, under this option AML supervision in the Union would remain primarily at national level, with national competent authorities retaining full responsibility and accountability for direct supervision of obliged entities. This model would build on the AML mandate currently carried out by EBA but strengthen it further with respect to both competences and powers. At EU level, an AML Authority would be granted adequate powers to ensure that supervisory actions at national level are consistent and of a high quality across the EU.

For this, the EU AML Authority would need to have extensive access to real time information from national supervisors about their activity, and this access could be used to identify and communicate trends and risks, conduct more targeted reviews of national supervisory approaches, and foster information exchange and cooperation. Through its indirect oversight capacity, the AML Authority would contribute to enhancing supervisory convergence, cooperation and information exchange between national competent authorities.

The scope of the activity of this Authority would expand to cover the non-financial sector, where it would facilitate convergence of supervisory practices, exchanges of good practices and peer reviews. In specific cases where national supervision is insufficient, it would be given powers to recommend specific actions to the national supervisors.

Option 3:

Direct supervisory powers over selected risky entities in the financial sector subject to AML/CFT requirements and indirect oversight over all other entities