EUROPEAN COMMISSION

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Brussels, 18.11.2020

COM(2020) 745 final

REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION

TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK AND THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE

Alert Mechanism Report 2021

(prepared in accordance with Articles 3 and 4 of Regulation (EU) No 1176/2011 on the prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances)

{SWD(2020) 275 final}

|

|

|

|

This alert mechanism report (AMR) initiates the tenth annual round of the macroeconomic imbalance procedure (MIP). The procedure aims at detecting, preventing and correcting imbalances that hinder the proper functioning of Member State economies, the economic and monetary union or the Union as a whole, and at spurring appropriate policy responses. The implementation of the MIP is embedded in the European Semester of economic policy coordination to ensure consistency with the analyses and recommendations made under other economic surveillance tools (Articles 1 and 2 of Regulation (EU) No 1176/2011).

This year's surveillance cycle of the European Semester, including the implementation of the MIP, is being adjusted in light of the creation of the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF). The annual sustainable growth strategy (ASGS), adopted in mid-September 2020, took stock of the economic and social situation in Europe, set out broad policy priorities for the EU as well as provided strategic guidance for the implementation of the RRF.

The AMR analysis is based on the economic reading of a scoreboard of selected indicators, complemented by a wider set of auxiliary indicators, analytical tools and assessment frameworks and additional relevant information, including recently published data and forecasts. This year's AMR includes a reinforced forward-looking assessment of risks to macroeconomic stability and for the evolution of macroeconomic imbalances. The AMR includes also an analysis of the euro area-wide implications of the Member States macroeconomic imbalances.

The AMR identifies Member States for which in-depth reviews (IDRs) should be undertaken to assess whether they are affected by imbalances in need of policy action (Article 5 of Regulation (EU) No 1176/2011). Taking into account discussions on the AMR with the European Parliament and within the Council and the Eurogroup, the Commission will then prepare IDRs for the Member States concerned. The IDRs will be published in spring 2021, and will provide the basis for the Commission assessment regarding the existence and severity of macroeconomic imbalances, and for the identification of policy gaps.

|

1.Executive Summary

This Alert Mechanism Report (AMR) is carried out against the backdrop of the COVID-19 crisis. Given the rapid and marked change in economic conditions brought about by the COVID-19 crisis, this report’s economic reading includes a reinforced forward-looking assessment of risks to macroeconomic stability and for the evolution of macroeconomic imbalances. To this end, it is necessary to look beyond the AMR scoreboard final annual data, which in this year's AMR covers the period up to 2019. Thus, this year's report, compared with previous years, makes a greater use of forecasts and high-frequency data to gauge the potential implications of the COVID-19 crisis.

The current surveillance cycle of the European Semester is being temporarily adjusted to ensure consistent and effective implementation of the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), and this will also affect the implementation of the Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure (MIP). The 2021 Annual Sustainable Growth Strategy (ASGS), which was adopted in mid-September, launched this year's European Semester cycle and set out strategic guidance for the implementation of the RRF. The RRF foresees that Member States will adopt Recovery and Resilience Plans (RRPs) which set out reforms and investment that address key economic challenges and are aligned with EU priorities, which includes the country-specific recommendations addressed to the Member States in recent years and in particular in the 2019 and 2020 Semester cycles. The RRF is therefore an opportunity for Member States to implement reforms and investments in line with MIP-related recommendations that address the underlying and long-standing structural causes of existing macroeconomic imbalances. Specific Monitoring of policy responses to existing macroeconomic imbalances is not taking place in autumn 2020, but instead monitoring will take place in the context of the assessment of the RRPs. The next vintage of in-depth reviews (IDRs) will be published in spring 2021, jointly with the assessment of Stability and Convergence Programmes, and will look closely into the gravity and evolution of already identified imbalances and inquire the risks of emergence of new ones.

Most existing macroeconomic imbalances have been undergoing a process of correction amid favourable macroeconomic conditions up until the outbreak of the COVID-19 crisis. Flow imbalances, such as excessively large current account deficits or buoyant credit growth, had been corrected in the years following the 2008 financial crisis, in a context of broad-based private sector deleveraging. The economic expansion that started in 2013 supported the correction of stock imbalances, which has started later and progressed more slowly, by prompting the reduction of private, public, and external debt-to-GDP ratios and by strengthening bank balance sheets. At the same time, over recent years, the economic expansion has brought some overheating risks, mainly at the level of house prices dynamics and cost competitiveness developments, especially in countries where economic growth was buoyant.

A number of existing macroeconomic imbalances are being aggravated by the COVID-19 crisis, and new risks may loom. In particular, government and private debt-to-GDP ratios are on the rise. Going forward, private sector debt repayment might be challenged by subdued levels of economic activity, bankruptcies, and a weak labour market. Such debt distress would affect banks’ balance sheets and further impair their profitability. At the same time, excessively buoyant labour cost and house price dynamics that characterised the recent past are expected to fade, but concerns may arise if such adjustment turns into excessive downward corrections, notably of house prices in Member States with already high household debt.

The horizontal analysis presented in the AMR leads to a number of conclusions:

·Developments in current accounts in most EU Member States following the COVID-19 crisis are likely not to be major. Current account deficits remain moderate in most countries. Some large current surplus persist although narrowing in recent years. Current accounts are forecast to move relatively little with the COVID-19 crisis. This is in sharp contrast with the developments during the global financial crisis, when deficits in EU countries were significant and the crisis triggered their unwinding. The stability of current account figures however masks big shifts in the contribution of different sectors to the overall external position, as large increases in the net lending position of the private sector are being offset by substantial worsening of the net lending position of governments in their efforts to cushion the impact of the crisis.

·The improvements recorded in the net international investment position (NIIP) of most Member States in past years are expected to stop. While large stock of external imbalances persist in a number of Member States, NIIP improvements continued in 2019 in most EU countries, driven by current account outturns above NIIP-stabilising levels, nominal GDP growth, and sometimes large positive valuation effects. Going forward, improvements in the NIIP-to-GDP ratio are expected to come to a halt, on the back of the large GDP contraction in 2020 and relatively stable current account outturns.

·Some external financing tensions surfaced at the onset of the COVID-19 crisis in some non‑euro area Member States. Capital movements and exchange rates of some non‑euro area Member States were subject to market pressure over a brief period in late March and April in light of increased risk aversion. Such pressures have since eased amid improved financial market outcomes.

·The labour market impact of the COVID-19 crisis has so far been relatively mild compared to the scale of the recession, thanks also to policy measures such as short-time work schemes, but unemployment is expected to rise. The crisis ended years of improving labour markets across the EU. To date, it has led mostly to a fall in average hours per worker while headcount unemployment has only increased a little. This phenomenon of labour hoarding, i.e. of companies holding on to their employees, which has characterised many EU economies in 2020 is largely owed to government-subsidised initiatives to preserve jobs, notably temporary short-time work schemes. Unemployment is however expected to increase with some lag, as it typically happens after recessions. There are in particular risks of significant job losses in the sectors strongly affected by the pandemic, depending both on how long lasting these effects will prove, and on the strength of the policy response.

·Unit labour costs (ULCs) have been accelerating in various EU countries in recent years given wage increase and weak productivity growth, but are expected to moderate going forward, following a stark increase in 2020. Strong ULC dynamics in a context of robust economic growth was recorded in several central and eastern European and Baltic countries in recent years. Falling labour productivity, stemming from the fall in production coupled with maintaining jobs, is projected to push ULC growth up in 2020, despite a marked slowdown in wage growth. In 2021, the projected gradual recovery in economic activity is expected to imply a rebound in headline productivity, which would partly offset the ULC increase in 2020.

·Corporate debt is expected to increase considerably across the board in 2020, notably on account of liquidity needs. Borrowing to finance working capital surged with the COVID-19 outbreak, and credit to non-financial corporations has increased in most countries. Credit guarantees have helped businesses to borrow in support of their operations, and also to strengthen their liquidity positions. Debt repayment moratoria also contributed to the debt increase. Growing debt levels, combined with the significant drop in GDP in 2020, are expected to sharply increase debt-to-GDP ratios especially in the short term. Going forward, the dynamics of debt-to-GDP ratios are likely to improve with the recovery but servicing debt could be challenging particularly in sectors impacted by the pandemic in a more lasting way. This would impact the balance sheets of lenders too.

·Household debt dynamics appear relatively contained. Before the COVID-19 crisis, household credit started growing again at a dynamic pace in a number of countries after years of deleveraging or subdued dynamics. The evolution of the household debt stock appears to be somewhat decelerating in 2020. This is happening despite the impact of debt moratoria, which have eased liquidity pressures from indebted households and reduced the pace of repayments. Household debt-to-GDP ratios are mechanically growing in 2020 in light of the drop in GDP. At the same time, household savings have risen amid a sharp drop in consumption. Debt repayment prospects for households are clouded by the deterioration in labour markets.

·House price growth remained robust into 2020, with accelerations in some countries, but a moderation and possible downward corrections look likely. In 2019, house prices kept growing at high rates, also in a number of countries that were showing risks of overvaluation. The impact of the crisis on employment prospects and household incomes will normally be reflected in a moderation of house price dynamics. Latest quarterly data already point to a softening of housing markets in more than half of the EU countries. House price growth forecasts suggest downward corrections in a large majority of Member States over the period 2020-2021.

·After having followed a downward trend in recent years on the back of stronger nominal GDP growth, government debt is currently on the rapid rise in all Member States, especially in those where the COVID-19 crisis had the most severe impact. In recent years, government debt has kept declining in most Member States, while in a few high-debt countries reductions were absent or limited. During the crisis, governments across the EU have let automatic stabilisers function and have provided direct fiscal and liquidity support to mitigate the health crisis and the private sector spending retrenchment. Government debt ratios are increasing more where pre-crisis debt levels were already the highest, reflecting also the fact that the recession has been deeper in those countries. Exceptional monetary easing and various EU and euro area level initiatives have kept financing costs at historically low levels and supported confidence. While some countries have taken advantage of the high liquidity and demand by investors to lengthen the maturity structure of their sovereign debt, the structure of government debt might entail risks for others, notably on account of short maturity structures and high shares of debt denominated in foreign currency.

·Conditions in the banking sector improved in past years, but the COVID-19 shock could test the resilience of the EU banking sector. Conditions in the banking sector have improved considerably since the global financial crisis, with stronger capital ratios and liquidity buffers than a decade ago. However, the sector has remained challenged by low levels of profitability in a low interest rate environment, and, in a few countries, by still relatively high levels of non-performing loans. Ample liquidity provided by central banks helped avoiding a credit crunch after the COVID-19 outbreak and the suspension of dividend payments and some temporary regulatory relief is also giving further breathing space to banks. The crisis is expected to harm asset quality and profitability prospects. Rising debt repayment difficulties by corporations and households would translate into non-performing loans (NPLs) going forward, especially once debt moratoria have expired. Downward corrections in house prices may affect collateral valuations and therefore bank balance sheets.

The COVID-19 shock is exacerbating existing imbalances within the euro area, which highlights the need of making the best use of the EU support measures. According to the Commission autumn 2020 economic forecast, the Member States most impacted economically by the COVID-19 crisis because of the gravity of the pandemic or of the dependence on highly exposed sectors are characterised by relatively large stocks of government and external debt. The COVID‑19 crisis thus appears to be accentuating existing patterns within the euro area regarding domestic and foreign indebtedness. A number of the countries highly impacted by the COVID‑19 crisis were in the recent past characterised by anaemic potential growth. Hence, the pandemic could also be exacerbating economic divergences. In parallel, despite the large fall in world demand, a trade surplus is currently projected to persist for the euro area as a whole, highlighting that there could be further room to expand domestic demand at the euro area aggregate level to foster the recovery, while supporting the ECB efforts to reach the inflation target. In light of growing indebtedness in all Member States, the RRF and other financial support instruments put in place at euro area and EU level, including SURE, REACT-EU and higher flexibility in the use of remaining EU funds, can help Member States create the conditions for a durable recovery and strengthen resilience. Going forward, it is important that supportive policy measures, reforms and investments put in place across the euro area are combined in such a way to address effectively macroeconomic imbalances, in particular where they are excessive.

All in all, with the COVID-19 crisis, risks appear to be on the rise in countries already identified with (excessive) imbalances. To some extent, the COVID‑19 crisis is a setback in the gradual reduction in imbalances in many Member States, which was mainly driven by the economic expansion since 2013. At the same time, pre-existing overheating pressures related to strong house price and unit labour cost growth now appear as less of a risk in the medium term, possibly even facing downward corrections. While pressures on capital flows and exchange rates were proved short-lived in 2020 so far, market sentiment might remain volatile. Hence, surveillance needs to focus on countries where risks appear on the rise, which mainly coincide with countries already identified with imbalances. In addition, developments need to be monitored closely in other Member States, including in a few non‑euro area economies, where external sustainability concerns have manifested into market pressures during spring and well as in Member States with very high debt levels.

The increase in private and government debt-to-GDP ratios in 2020 calls for careful monitoring while not requiring at this stage new IDRs. Risks to macroeconomic imbalances, notably those linked to growing debt-to-GDP ratios, are aggravating especially in countries already identified with imbalances or excessive imbalances. The significant debt-to-GDP ratio increases in 2020 are to a large extent linked to the mechanical effect of temporary but large recessions reducing the denominator of that ratio. These increases in government debt and corporate debt are also linked to the adjustment to the large one-off COVID-19 shock and the outcome of deliberate and temporary policy efforts (also linked to measures such as bank guarantees and moratoria on repayments) to cushion the impact of the crisis and prevent an even bigger repercussion of the pandemic on economic activity, incomes and macroeconomic stability going forward. Preventing the recession from becoming deeper and entrenched is a necessary response to improve debt prospects going forward even if implying temporary debt increases.

IDRs will be prepared for the Member States already identified with imbalances or excessive imbalances. In line with the established prudential practice, IDRs will be conducted to assess whether existing imbalances are unwinding, persisting or aggravating, while taking stock of corrective policies implemented. The preparation of IDRs is thereby foreseen for the 12 Member States identified with imbalances and excessive imbalances in light of the findings of the February 2020 IDRs.

Nine Member States are currently identified with imbalances (Croatia, France, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, Spain, and Sweden), while Cyprus, Greece, and Italy are identified with excessive imbalances.

This AMR highlights potentially risky developments in a number of Member States for which IDRs will not be prepared. Following the COVID-19 outbreak, risks have surfaced in some non-euro area countries linked to external financing. Hungary appears as a case where the interplay between government borrowing and external financing deserves monitoring. Government debt is partly financed in foreign currency, which reflects the open nature of the economy and the fact that part of the revenues of the public sector and of the private sector are in foreign exchange. However, government debt has very short maturity and with relevant holdings by the domestic banking sector, while official reserves in early 2020 were close to prudential minima. While market pressures have eased since spring and there are currently no solid indications that there are risks of imbalances, such risks may resurface in the future and therefore require careful monitoring. The implications of growing debt-to-GDP ratios also deserve monitoring in a number of Member States not currently under MIP surveillance. In, both private and government debt are expected to further grow above the MIP thresholds. Member States where private debt is forecast to be on the rise and above threshold are Denmark, Finland, and Luxembourg. Government debt is expected to further grow above 60% of GDP in Austria and Slovenia. The extent to which those developments entail additional risks for macroeconomic stability is surrounded by large uncertainty, given in particular the need to take also into consideration medium and longer-term growth prospects, and how they are affected by COVID-19 crisis,. Therefore, while the projected increase in debt ratios requires careful monitoring, there is at this stage no need to carry out an IDR for additional Member States.

2.

the changing economic outlook: implications for euro area macroeconomic imbalances

The COVID-19 pandemic acted as a one-of-a-kind shock to the economy. The outbreak of the pandemic was followed by restrictive measures to limit the contagion starting in March 2020, which were gradually eased starting in May in most Member States. The measures put in place were broadly proportional to the severity of the health emergency but with relevant differences across countries. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, a massive demand shock affecting consumption was compounded by supply restrictions during lockdowns. Consumption dynamics remain subdued compared with pre-COVID trends, notably for service activities where human contact is more difficult to avoid. Investment remains hampered by substantial uncertainty. Reduced income and employment growth, as well as subdued export market dynamics, will keep holding back demand down the road. The disruption of some value chains and distancing measures on the workplace keep affecting supply, denting on productivity. The EU and other world areas are currently in the middle of a new outbreak of the pandemic, whose severity and duration is surrounded by major uncertainty. Overall, the Commission autumn 2020 economic forecast expects GDP to fall by -7.8% in the euro area and -7.4% in the EU in 2020. Despite the recovery expected for 2021, GDP levels are forecast to be below the 2019 pre-crisis levels (Graph 1).

Exceptional policy responses helped cushion the economic fallout of the COVID-19 crisis. Tremendous policy action was put in place across the EU and in major world areas to prevent the collapse in incomes following restrictive measures and reduce the risk of large job losses and corporate bankruptcies. Governments provided fiscal support by means of short-term working schemes and beefed‑up income support to the unemployed. Moratoria were provided for tax payments and loan mortgage repayments. Guarantees for bank loans were provided to prevent credit being squeezed. The ECB took a broad range of supportive measures to preserve financial stability and the smooth functioning of financial markets, including additional liquidity provision for banks, eased collateral requirements, as well as substantial additional purchases of public and private sector assets under the Asset Purchase Programme (APP) and the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP). The Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) relaxed regulatory requirements on banks in a counter-cyclical way. The European Stability Mechanism (ESM) made available to all euro area Member States a Pandemic Crisis Support, based on its Enhanced Conditions Credit Line (ECCL). The EU and its Member States put in place three safety nets for workers, companies and sovereigns: a facility for temporary Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency (SURE), the European Investment Bank’s Pan-European Guarantee Fund and the ESM’s Pandemic Crisis Support. The Commission made proposals for new instruments to foster the recovery (Next Generation EU) that were agreed by the European Council in July, notably a large-scale Recovery and Resilience Facility. This facility provides grants and loans to foster reforms and investment to enhance the growth potential, strengthen economic and social resilience and facilitate the green and digital transition, consistent with the Union objectives in that regard. A range of other policy measures were taken, including speeding up and making more flexible the use of remaining EU funds, putting in place a temporary state aid framework and activating the General Escape Clause under the Stability and Growth Pact.

|

Graph 1: GDP in constant prices in comparison with pre-crisis levels

|

Graph 2: Economic sentiment and stock market index, 2013-2020

|

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission autumn 2020 economic forecast

|

Source: European Commission and ECB, provided by DataStream

|

The COVID-19 outbreak was followed by strong initial reactions on financial markets. Financial markets anticipated a major recession soon after the outbreak of the COVID crisis. Stock markets plunged against the backdrop of revised expectations on corporate profits. Bond market valuations reflected flight-to-safety dynamics, with risk premia rising on government bonds perceived more risky by investors and corporate bond spreads increasing notably for low rating segments. Exchange rate dynamics reflected pressures on emerging markets amid capital outflows and major downward corrections in oil and commodity prices. Some downward pressures were felt also on the currencies of a few non‑euro area Member States. Tensions were particularly noticed also in some of the currencies and bond yields of non‑euro area Member States adopting flexible exchange rate regimes amidst augmented volatility in capital flows.

Financial market conditions have improved substantially following the support measures by public authorities, decoupling from real economy prospects. Stock and bond markets recovered amid narrowing risk premia. Exchange rate markets stabilised, as well as commodity markets. Losses accumulated following the COVID-19 outbreak have been substantially reduced, and market volatility has been contained. In a context of massive, timely and credible interventions by public authorities, financial markets appear to have decoupled from real economy prospects, which are still surrounded by substantial downside risks (

Graph 2

).

There is an elevated degree of uncertainty surrounding the economic outlook related to the evolution of the pandemic, as well as policy responses and behavioural changes by economic agents. The effects of the spring 2020 recessions have not fully unfolded yet for what concerns implications on employment, bankruptcies, and banks’ balance sheets. The currently unfolding of the ongoing second outbreak of the pandemic is impacting the growth outlook through the introduction of new containment measures. These are expected to weigh on economic activity and sentiment in the short run, with negative effects on consumption and investment, though to a lesser extent than in the spring, as the approach so far has been more targeted. Accordingly, after a strong rebound in the third quarter, EU GDP growth looks set to stall in the fourth quarter of 2020. In addition, trade tensions and geo-political tensions may re-emerge. The supportive stance of fiscal and monetary authorities has so far been judged as credible by financial markets, and a premature withdrawal of policy measures would be a risk. A re-appraisal of risks and possible new episodes of financial stress cannot be ruled out especially in countries that combine high indebtedness, weak external positions, and large financing needs that cannot be fully financed domestically. On the upside, faster progress in controlling the pandemic and the implementation of ambitious and coordinated policies within the EU could enable a faster recovery.

Current economic developments have implications for macroeconomic imbalances. Government and private debt-to-GDP ratios are on the rise in a majority of Member States. This is due to both the mechanic outcome of the recessions reducing the denominator of debt-GDP-ratios and increased borrowing by the public and the corporate sector to cushion the impact of the COVID-19 crisis. Ultimately, worsening prospects for government and private debt is a risk that could impact financial sector balance sheets, which would also be directly impacted by the COVID-19 shock in terms of reduced profitability. At the same time, the trends that were observed in a number of Member States for what concerns deteriorating cost and price competitiveness and strong house prices growth are now likely to come to a halt. However, this raises instead questions about the implications of a reversal in those patterns. In particular, weak or negative developments in labour income may imply reduced repayment capacity for households, while downward corrections for house prices, especially if taking place in countries with high levels of household debt and unfolding in a disorderly fashion, may affect banks' balance sheets by leading to lower collateral values.

|

Graph 3: Recessions, Oxford Stringency Index and pre-COVID-19 debt levels

|

Graph 4: Euro area output, domestic demand, net exports and core inflation

|

|

Source: Eurostat, European Commission autumn 2020 economic forecast and Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker

|

Source: AMECO and European Commission autumn 2020 economic forecast.

Note: while the difference between GDP and domestic demand should equal the trade balance by definition, data are not fully aligned due to intra-euro area reporting discrepancies.

|

The COVID-19 shock appears to exacerbate existing imbalances within the euro area.

While the level of debt does not appear to have been a factor which significantly aggravated post-COVID recessions, a majority of countries that were hit the hardest by the COVID-19 pandemic and had to put in place containment measures happened to be characterised by relatively large stocks of public or private debt (

Graph 3

). This implies that, because of relatively strong recessions, debt-to-GDP ratios are on the rise especially in countries where debt stocks were already comparatively high. Some of the net-debtor countries that were hard hit by the pandemic are also characterised by a relatively high share of tourism revenues (e.g., Cyprus, Greece, Portugal, Spain), which are particularly exposed to the COVID crisis, with implications also for their external balances. In a nutshell, the COVID crisis appears to be reinforcing existing patterns within the euro area regarding economic divergences, domestic and foreign indebtedness.

In view of the massive fall in aggregate demand, the gradual reduction in the euro area trade balance surplus is projected to come to an end. The euro area trade surplus has been declining since 2017, and is projected to remain broadly stable in 2020 and 2021. The fall of GDP in 2020 and its recovery in 2021 is expected to be broadly in line with the evolution of domestic demand. By the same token, the dynamics of euro area imports are projected to be closely aligned with those of exports. The trade surplus at euro area level is therefore not expected to further decline, against the backdrop of a deterioration of the output gap in 2020 that is forecast to be larger than the one observed in 2009 after the financial crisis. In parallel, core inflation is expected to remain subdued (

Graph 4

).

|

Graph 5: Euro area current account evolution: breakdown by country

|

Graph 6: Euro area net lending/borrowing

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Eurostat Balance of Payments and European Commission autumn 2020 economic forecast.

Note: The EA19 CA for years 2020 and 2021 correspond to the European Commission autumn 2020 forecast adjusted figure, which accounts for in intra-euro area reporting discrepancies by the different national statistical authorities (see footnote 17).

|

Source: AMECO, Eurostat, European Commission autumn 2020 economic forecast.

Note: The EA19 Total Economy figures for 2020 and 2021 correspond to the European Commission autumn 2020 forecast adjusted figures. For the earlier years, the EA19 Total Economy figures correspond to net lending/borrowing in the Eurostat BoP data. Households and the Corporations sector data for 2020 and 2021 are computed as the sum of the EA19 countries except Malta, for which no data are available.

|

Graph 7: Nominal effective exchange rates (NEER)

Source: ECB

The current account surplus of the euro area as a share of GDP has been falling since 2017 and is projected to further decline in 2020. The euro area current account rose until 2017 amid widespread deleveraging, and, since then, it has shown a reduction. In 2019, the euro area current account balance is estimated at 2.3% of GDP (

Graph 5

).

While between 2017 and 2018, the reduction of the current account surplus was mainly associated with developments in the trade balance for goods, notably linked to trade policy tensions and a more expensive energy bill, in 2019, the drop was largely accounted for by the services balance. Nevertheless, the 2019 euro area current account surplus remained the largest worldwide in nominal terms. Its value, also when adjusted for the cycle, was slightly above a current account norm in line with economic fundamentals estimated at 2% of euro area GDP.

At unchanged policies, the euro area current account surplus is expected to further decrease to 1.8% of GDP in 2020 and to edge up to 1.9% of GDP in 2021 according to the European Commission autumn 2020 forecast, thus falling below the current estimate of the current account norm. The forecast reduction in the euro area surplus is partly due to a reduced energy bill; the substantial appreciation of the euro that started in early 2020 (

Graph 7

) would also imply a reduction in the current account going forward.

The geographical breakdown of the euro area current account surplus remains stable, while the major changes are taking place for what concerns the contribution of the different sectors of the economy. The euro area surplus still reflects mainly the large, but steadily falling, surpluses recorded in Germany and the Netherlands, whose combined external balances accounted for 2.7% of euro area GDP in 2019. Euro area current account balances are expected to display a certain stability across countries also in 2020 and 2021 (

Graph 5

). The stability of current account figures masks however considerable changes in the net lending positions across sectors of the economy, as the large increase in the net lending position for the private sector is almost fully offset by a deterioration in that of the government sector (

Graph 6

). This pattern, observed for the euro area as a whole, holds also within countries. In 2020, the large increase in savings by the households sector is largely linked to lockdown measures and subdued dynamics in the consumption of services allowing for little physical distancing, as well as precautionary savings to deal with heightened uncertainty. The upward jump in the net lending position of corporations is partly associated with a drop in investment and partly the result of an increase in precautionary savings. The falling government revenues and the fiscal measures put in place to cushion the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on incomes translate into a substantial deterioration of the net lending position of the government sector. Similar patterns, although less marked, are forecast for 2021.

Going forward, addressing the growing macroeconomic risks require an effective implementation of the EU support measures.

·The current crisis is fundamentally different than the 2008 financial crisis. While the latter was largely the result of the unwinding of unsustainable imbalances (financial sector overleveraging, housing bubbles, large and growing external deficits, and government debts rising in good times), the COVID-19 crisis is the result of shocks to the economy originating from government restrictions and changed behavioural patterns related to health concerns. These shocks take place in a context where, thanks to recent favourable economic conditions, most external positions moved to balance or surplus, financial sector deleveraging over the past years created solid capital buffers in the banking sector, private sector deleveraging has taken private debt-GDP back to levels well below the peaks observed before the 2008 financial crisis, and public debt-to-GDP ratios embarked into a downward trajectory in most euro area Member States.

·Going forward, debt repayment prospects crucially depend on ensuring the economic recovery and strengthening the economic fundamentals, which requires a supportive policy stance throughout 2021. A sustainable recovery is crucial both for the government sector, in terms of dynamics for government revenues, and for the financial and non-financial corporate sector, with repayment capacity depending on profitability, and for households, with prospects for mortgage debt sustainability depending on employment and income dynamics.

·An effective use of available instruments put in place at euro area and EU level, with effective implementation of the necessary reforms and investment, would help fostering a durable recovery and strengthening resilience. It will be crucial that EU financing is fully absorbed and channelled to the most productive uses. This would both strengthen the economic impact of the funds and prevent the risk that such increased spending in a short‑time frame fuels an excessive growth of non-tradable activities and external imbalances in countries where inflows account for a large share of GDP.

·Going forward, it is important that supportive policy measures, reforms and investments put in place across the euro area are combined in such a way to address effectively macroeconomic imbalances, in particular where they are excessive.

3.

Imbalances, Risks and Adjustment: main developments across countries

The AMR builds on an economic reading of the MIP scoreboard of indicators, which provides a filtering device for detecting prima-facie evidence of possible risks and vulnerabilities. The scoreboard includes 14 indicators with indicative thresholds in the following areas: external positions, competitiveness, private and government debt, housing markets, the banking sector, and employment. It relies on actual data of good statistical quality to ensure data stability and cross-country consistency. In accordance with the MIP regulation (Regulation (EU) No 1176/2011), scoreboard values are not read mechanically in the assessments included in the AMR, but are instead subject to an economic reading that enables a deeper understanding of the overall economic context and taking into account country-specific considerations.

A set of 28 auxiliary indicators complements the reading of the scoreboard.

In comparison with previous AMRs, the present report makes a greater use of forecasts and high-frequency data to gauge also the implications of the COVID-19 crisis amid large uncertainty. Those implications cannot be captured from the official AMR scoreboard, as it only reflects data up to 2019. Values of scoreboard variables and other relevant variables for MIP analysis for 2020 and 2021 have therefore been estimated using Commission forecast data and nowcasts from infra-annual data (see Box 1 for details per scoreboard variable). While such exercise appears necessary to gauge ongoing developments, it is also necessary to recall the substantial uncertainty underlying those forecasts. In the AMR assessment, as in previous years, insights from assessment frameworks, as well as findings in existing IDRs and relevant analyses, are also taken into consideration. The Commission analysis continues to be subject to the principles of transparency about analysis and data used, and prudence on the conclusions on account of awareness of caveats with data quality.

Scoreboard data suggest that the recent correction of stock imbalances would come to a halt, while risks of overheating observed in recent years are expected to cool with the crisis. The counting of values beyond the thresholds in the AMR scoreboard over the years reveals a number of patterns as follows (

Graph 8

).

·The economic expansion that started in 2013 helped reducing private and government debt-to-GDP ratios, thanks to the favourable denominator effects. This is reflected in the falling number of countries exhibiting debt ratios beyond thresholds until 2019. The COVID-19 crisis appears to put an end to this trend.

·After the correction of the large current account deficits of the 2000s, the past decade was marked by the accumulation of large current account surpluses for some economies, which were reduced in latest years. The COVID crisis is not expected to fundamentally change the external adjustment as its impact on the external accounts is expected to be limited, with the number of countries exceeding the thresholds for current account balances and NIIPs being only marginally affected.

·Fast growing unit labour costs and house prices have led to more readings beyond the relevant thresholds in the latest number of years. Those overheating pressures that manifested in fast-growing countries are expected to phase out with the COVID crisis. That is most visible at the level of house prices, which are expected to cool down and fewer cases risk being beyond the threshold. ULC growth may also recede but only after a temporary but sharp hike in 2020 with over half of the Member States risking being beyond the threshold. This reflects the mechanical effect of a visibly lower productivity on account of the sharply reduced activity and less affected employment. REERs are projected to exceed thresholds largely in light of nominal exchange rate developments.

Graph 8: Number of Member States recording scoreboard variables beyond threshold

Source: Eurostat and Commission services calculations (see also Box 1)

Note: The number of countries recording scoreboard variables beyond threshold is based on the vintage of the scoreboard published with the respective annual AMR. Possible ex-post data revisions may imply a difference in the number of values beyond threshold computed using the latest figures for the scoreboard variables compared with the number reported in the graph above. For the approaches followed for the forecasts of the scoreboard indicators in the years 2020 and 2021, see Box 1. Forecasts for the following indicators are performed for 2020 only: Private credit flow, Private debt, Financial sector liabilities, Long-term unemployment, Youth unemployment.

|

Box 1: Nowcasts of the headline scoreboard indicators

To enhance the forward-looking elements in the scoreboard reading, the AMR analysis builds also, whenever possible, on forecasts and projections for 2020 and 2021 and ‘nowcasts’ for the current year. Whenever available, such figures are based on the Commission autumn 2020 forecast. Otherwise, figures display nowcasts based on proxy indicators, prepared by Commission services specifically for the purpose of this AMR.

The table below summarises the assumptions used for the forecasts and ‘nowcasts’ figures of headline scoreboard indicators. Note that the GDP figures used as denominators in some ratios stem from the Commission autumn forecast.

In case of multi-annual rates of change (such as the five-year change of export market shares), only the 2020 and 2021 component is based on forecasts, whereas components related to 2019 or earlier years use the Eurostat data underlying the MIP scoreboard.

|

|

Table: Approaches to forecasts and nowcasts for MIP scoreboard headline indicators

|

|

Indicator

|

Approach

|

Data sources

|

|

Current account balance, % of GDP (3 year average)

|

Values from Commission autumn forecast of the current account balance (Balance of Payments concept)

|

AMECO

|

|

Net international investment position (% of GDP)

|

The Commission autumn forecasts for total economy net lending/borrowing provides the NIIP change that reflects transactions; other effects (e.g. valuation changes) are taken into account until 2020Q2, and assumed to remain nil thereafter.

|

AMECO, Eurostat

|

|

Real effective exchange rate - 42 trading partners, HICP deflator (3 year % change)

|

Values from the Commission autumn forecast

|

AMECO

|

|

Export market share - % of world exports (5 year % change)

|

Figures are based on the Commission forecast of i) nominal goods and services (G&S) exports for EU Member States (national accounts concept), and ii) Commission forecast of (G&S) exports in volumes for the rest of the world, translated to nominal levels by the Commission US import deflator and EUR/USD exchange rate forecasts

|

AMECO

|

|

Nominal unit labour cost index, 2010=100 (3 year % change)

|

Values from the Commission autumn forecast

|

AMECO

|

|

House price index (2015=100), deflated (1 year % change)

|

Model-based forecasts computed on the basis a housing valuation model shared with Member States in the context of the EPC LIME working group. The forecasts represent real house price percentage changes expected based on economic fundamentals (population, disposable income forecast, housing stock, long-term interest rate, and the price deflator of private final consumption expenditure), as well as the error correction term summarising the adjustment of prices towards their long-run relation with fundamentals.

|

Eurostat, Commission services

|

|

Private sector credit flow, consolidated (% of GDP)

|

The figure for 2020 represents a proxy of credit flows 2020Q1-2020Q3, using consolidated data from ECB quarterly sectoral accounts for 2020Q1-Q2, plus proxies for some credit flow components from 2020Q3. The latter uses ECB BSI MFI loan flows to the private sector to project 2020Q3 bank loan components, and ECB SEC nominal debt security issuance to project 2020Q3 bond issuance.

|

ECB (QSA, BSI, SEC)

|

|

Private sector debt, consolidated (% of GDP)

|

The figure for 2020 proxies private sector debt as at end-2020Q3. It uses consolidated data from ECB quarterly sectoral accounts for 2020Q2. This figure is projected forward to 2020Q3 using bank loan figures (based on ECB BSI) and bond liability data (based on ECB SEC).

|

ECB (QSA, BSI, SEC)

|

|

General government gross debt (% of GDP)

|

Values from the Commission autumn forecast

|

AMECO

|

|

Unemployment rate (3 year average)

|

Values from the Commission autumn forecast

|

AMECO

|

|

Total financial sector liabilities, non-consolidated (1 year % change)

|

2020 figure represents ECB MFI liabilities growth until September 2020.

|

ECB (BSI)

|

|

Activity rate - % of total population aged 15-64 (3 year change in pp)

|

The 2020 and 2021 rate of changes are based on the Commission autumn forecast for the change in the entire labour force (all ages) minus the Commission autumn forecast for the population change (15-64 age group).

|

AMECO

|

|

Long-term unemployment rate - % of active population aged 15-74 (3 year change in pp)

|

The nowcast for 2020 is based on latest data (2020 Q1-Q2, assuming constant rate for rest of the year)

|

Eurostat (LFS)

|

|

Youth unemployment rate - % of active population aged 15-24 (3 year change in pp)

|

The nowcast for 2020 is based on latest data (2020 Jan-Sep, assuming constant rate for rest of the year)

|

Eurostat (LFS)

|

3.1 External sector and competitiveness

Current account were overall fairly stable in 2019. After a general trend towards weakening current account positions in 2018 amid weakening world export demand and rising oil prices, current account changes between 2018 and 2019 did not exhibit a clear pattern and remained relatively contained (

Graph 10

). In 2019, notable improvements were observed in Bulgaria, Denmark and Lithuania, while the current account of Cyprus moved more deeply into negative territory. Some large surpluses reduced somewhat, including in Germany and the Netherlands.

·Two Member States record current account deficits beyond the MIP scoreboard lower threshold in 2019. The large deficit of Cyprus deteriorated further in 2019, and thereby the 3-year average remained below the MIP threshold, and below the respective current account norm and the level required to bring the NIIP to prudential territory over the next 10 years. Following a small further worsening in the current account of Romania, its 3-year average came at the MIP threshold in 2019, and such a reading is also visibly worse than the respective norm.

·In 2019, in most Member States, current account deficits were above country-specific benchmarks, with some notable exceptions (

Graph 9

).

Cyclically-adjusted current accounts were mostly close to or above the headline balances, reflecting the negative impact of a cooling economic cycle. The current account balances of Cyprus and Romania are below the current account norm justified by fundamentals. The deficits of Cyprus, Greece, and Portugal are below the level required to ensure the convergence of the NIIP towards a prudent level.

·Three EU countries continue recording current account surpluses that exceeded the MIP scoreboard upper threshold and country-specific benchmarks. That has been the case for Denmark, Germany, and the Netherlands for nearly a decade. While Denmark expanded its surplus in 2019, the balances of Germany and the Netherlands have continued to gradually move down. In the Netherlands, current account balances are also driven by the activities of multinational corporations that affect both the trade and income balances.

Forecasts point to a certain stability of current account readings also in 2020 and 2021, but with major changes for what concerns the contribution of the different sectors of the economy to the external position. The COVID-19 crisis is bringing a major drop in exports and in imports, of roughly similar proportions. Although the aggregate net lending position of EU countries is not moving much, marked changes are taking place for what concerns the net lending position of different sectors of the economy. In 2020, the government positions experienced substantial declines as result of the support measures they took to cushion the sharp recession, which countervail the higher net savings by households and corporations (

Graph 11

).

·Current account figures of some net-debtor countries with strong reliance on export of tourism services are expected to deteriorate. This is the case notably of Croatia, Cyprus, Greece, and Malta.

·Large surpluses would fall in 2020, with substantial decreases in Germany and the Netherlands over 2020 and 2021 together.

Graph 9: Current account balances and benchmarks in 2019

Source: Eurostat and Commission services calculations.

Note: Countries are ranked by current account balance in 2019. Cyclically-adjusted current account balances: see footnote 23. Current account norms: see footnote 22. The NIIP-stabilising current account benchmark is defined as the current account required to stabilise the NIIP at the current level over the next 10 years or, if the current NIIP is below its country-specific prudential threshold, the current account required to reach the NIIP prudential threshold over the next 10 years.

Graph 10: Evolution of current account balances

Source: Eurostat, European Commission autumn 2020 economic forecast and Commission services calculations.

Note: Countries are presented in increasing order of the current account balance in 2019.

Graph 11: Change in net lending/borrowing by sector, from 2019 to 2020

Source: AMECO and European Commission autumn 2020 economic forecast

Note: A part of the change in corporate sector net lending in Ireland is off the scale in the above graph.

NIIPs have kept improving in most Member States, but large stocks of external liabilities persist and the crisis might make some of those burdens heavier. NIIP improvements continued in 2019 in most EU countries, driven by current account outturns above NIIP-stabilising thresholds, nominal GDP growth, and sometimes large positive valuation effects. Yet NIIPs remain large and negative in a number of EU countries. In 2019, 11 Member States recorded NIIPs beyond the scoreboard threshold of -35% of GDP, one fewer than in 2018. In those countries, values are below those that could be justified by fundamentals (NIIP norms), and in most cases also below the respective prudential thresholds (

Graph 12

). The crisis is halting improvements in the more negative NIIPs-to-GDP ratios.

·Some euro area countries continue to have largely negative NIIPs below -100% of GDP, such as Cyprus, Greece, Ireland, and Portugal. In these four countries, NIIPs are well below both NIIP norms and prudential thresholds. In Ireland, as well as in Cyprus, NIIP levels reflect to a large extent cross-border financial relations of multinational corporations and the high importance of special purpose entities. These four countries, together with Spain, show a strong incidence of debt liabilities in their NIIPs as indicated by the very negative NIIP excluding non-defaultable instruments (NENDI). In Greece, the large external public debt, often at highly concessional terms, accounts for the bulk of the NIIP. In 2020, the expected strong declines in GDP should have some negative effect on their NIIP-to-GDP ratio, which are often projected to deteriorate.

·In countries with more moderately negative NIIPs beyond the scoreboard threshold, the NIIPs are below what is expected from country-specific fundamentals but sometimes close to or better than prudential thresholds. These countries, namely Croatia, Hungary, Latvia, Poland, Romania and Slovakia, as well as other central and eastern European and Baltic countries, tend to be large net recipients of FDI, so that NENDI figures are more favourable. The changes expected for those countries in 2020 are mostly mild to moderate.

·Most of the large positive NIIPs keep increasing in 2019. Germany, Denmark, and the Netherlands record positive NIIPs surpassing 70% of GDP, with their increase in 2019 supported also by substantial positive valuation effects. The NIIPs of Belgium, Malta, and Luxembourg exceed 50% of GDP. In all those cases, NIIPs readings are visibly above the respective norms, i.e. what could be justified by or expected on the basis of country-specific fundamentals.

The COVID-19 crisis outbreak was followed by external borrowing tensions in some non-euro area countries. At the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, capital flights and depreciations took place in most emerging economies with floating exchange rates. Markets anticipated possible trade-offs by monetary authorities between supporting their economies and stabilising their currencies. Some tensions were visible also in some of the currencies of non‑euro area Member States adopting flexible exchange rate regimes. Depreciations took place especially in March and April, notably in Hungary, but the pressure abated and the currencies stabilised in May, and in some cases appreciated in the following months. While the financial market tensions and, thereby external financing risks seem to have declined afterwards, a few non‑euro area Member States may remain vulnerable in case heightened risk aversion in global financial markets or capital flows volatility re-emerge. A number of conditions, including the prospects for foreign financing needs, including of the government, and the availability of foreign-exchange reserves may play a role in this respect.

Graph 12: Net international investment positions (NIIP) 2018-2021 and benchmarks in 2019

Source: Eurostat and Commission services calculations (see also Box 1).

Note: Countries are presented in decreasing order of the NIIP-to-GDP ratio in 2019. NENDI is the NIIP excluding non-defaultable instruments. For the concepts of NIIP norm and NIIP prudential threshold, see footnote 25. NENDI for IE, LU and MT are out of the scale.

Unit labour cost (ULC) continued growing dynamically in various EU countries in 2019 but those trends are bending down with the COVID-19 crisis. The scoreboard shows the ULC growth indicator beyond the threshold in eight countries in 2019, the same number as in the previous year: Bulgaria, Czechia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Romania, and Slovakia; apart from Luxembourg, all of them had been beyond the threshold already in 2018. Since 2013, ULC growth accelerated in the Baltic and in various central and eastern European countries in a context of high economic growth, tight labour markets and skills shortages.

Developments after the outburst of the COVID-19 outbreak are expected to be marked by a one-off increase in ULCs in 2020 followed by more moderated dynamics. With the COVID-19 crisis, ULC growth is projected to rise markedly further across the EU in 2020 as productivity declines nearly everywhere. However, that is projected to partly be reversed in 2021 as with the projected economic recovery, productivity would rebound and lead to a notable drop or stagnation in ULC in a context of decelerating wages (

Graph 13

, upper panel).

·Wage growth kept being the strongest driver of ULC growth in many countries in 2019 but the crisis is now leading to marked wage moderation. The crisis is putting an end to overheating pressures observed until 2019. Wage and compensation are forecast to grow more moderately in most EU countries in 2020 and 2021. In 2020, that reflects mainly the effect of reduced hours, largely in the context of temporary short-time work schemes. Under such schemes, workers maintain employment but at reduced hours and pay.

·Labour productivity gains remained limited in 2019 and the crisis is further denting productivity in 2020. In 2020, productivity is forecast to drop sharply in nearly all EU countries when measured in terms of output per person employed. The 2020 recession was matched by a drop in labour inputs. However, this was mainly on account of reduced hours, while headcount employment moved little. Hence, when productivity is measured in terms of output per hour worked, the losses appear more moderate (

Graph 13

, fourth panel). The substantial and pervasive labour hoarding observed across the EU has been much favoured by the wide use of governments-subsidised short-time work schemes.

In 2021, as the recovery sets in, an upward jump in productivity figures is expected. Yet, level-wise, productivity is forecast to remain around or below the pre-crisis readings in most cases.

|

Graph 13: Unit labour cost growth in recent years, compensation and productivity

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: AMECO; 2020 and 2021 data come from the European Commission autumn 2020 economic forecast. The data refer to the number of employees and of persons employed.

Note: In each graph, countries are presented in increasing order of the respective variable in 2019.

From a euro area perspective, ULC developments are expected to become slightly less supportive of rebalancing than in the past. In 2019, ULC growth was slightly higher in a number of net-creditor countries, including Germany, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, than in some net-debtor countries, including Cyprus, Greece, Ireland, Spain and Portugal. However, over 2020 and 2021 together, ULC growth is forecast to grow at almost the same rate in both country groups and thereby not contribute to further rebalancing in external positions (

Graph 14

). At the same time, a number of net-debtor countries have been among those more affected by the COVID-19 crisis (see also Section 2) and thereby record a more pronounced slack in activity, so that cost and wage pressures could be less prevalent in those countries going forward.

Graph 14: Unit labour cost growth across the euro area

Source: AMECO, 2020 and 2021 data come from the European Commission autumn 2020 economic forecast.

Notes: Countries with NIIP > +35% of GDP are DE, LU, NL, BE, MT. Countries with NIIP between 35% and -35% of GDP are FI, EE, IT, LT, FR, SI, AT. Remaining countries are in the NIIP < -35% of GDP group. The country split is based on NIIP average values in the 2017-2019 period. Net-creditor countries recorded an average current account surplus over the same period. Figures concern GDP-weighted averages for the three groups of countries.

Real effective exchange rates (REER) dynamics are increasingly driven by volatility in nominal exchange rates. Between 2016 and 2018, REERs were on the rise in most Member States in light of the euro appreciation (

Graph 15

). Competitiveness losses were most evident when measured in terms of unit labour costs. However, in 2019, competitiveness improved in light of a transitory euro depreciation. In light of these developments in 2019, only Estonia was beyond the thresholds on account of an appreciated HICP-based REER, compared to six countries in 2018, reflecting also muted inflation dynamics. Going forward, the appreciation of the euro in 2020 is expected to imply global competitiveness losses across euro area countries, while the currencies of some non‑euro area countries have witnessed depreciations.

·Nominal depreciations were common in 2019, while larger cross-country differences are observed in currency developments in 2020. Most EU countries recorded nominal depreciations in 2019, which was even stronger for some Member States outside the euro area, notably Hungary, Romania and Sweden. In 2020, the euro started to appreciate again after the COVID-19 outbreak. Outside the euro area, currencies have either broadly followed the euro, or have been appreciating markedly (Sweden), or depreciating considerably, notably in the case of Hungary, and to a lesser extent Czechia and Poland.

·ULC-based REERs appreciated in a majority of Member States in 2019, but less strongly than in recent years and the crisis is further dampening appreciation trends. Notably, a number of central and eastern European countries continued to exhibit stronger real appreciation in 2019. This includes some euro area countries, notably the Baltics and Slovakia and non‑euro area countries, notably Bulgaria, Czechia and Romania. Among net-creditor countries, only Germany and Malta exhibited a notable REER appreciation. After real appreciations forecast for 2020 in most countries reflecting the temporary jumps in ULC, the dampened ULC growth forecast for 2021 is expected to also lead to contained real appreciations in most EU countries.

·Price-cost margin compression is still observed in a majority of Member States. Dynamics in ULC-based REERs above those in the GDP-based REER have been observed in recent years and continued until 2019 although at lower pace, which suggests a further compression of profit margins.

This trend continued in 2020, most visibly for some central and eastern European countries, Belgium, Greece, Malta and Spain.

·Going forward, also REER measures suggest that cost competitiveness developments may be becoming less supportive of rebalancing than in the past. Over 2020 and 2021, large net-debtor countries or countries that have been more affected by the COVID-19 recession, such as Croatia, France, Italy, Portugal or Spain, are forecast to record only limited or no competitiveness gains vis-à-vis Germany and the Netherlands.

·The level of REER indexes appears above benchmark mostly in Member States that have been characterised by more prolonged trends of strong relative price dynamics. This is notably the case of central and eastern European countries.

Graph 15: Nominal and real effective exchange rates (NEER and REER) dynamics

Source: AMECO, 2020 and 2021 data come from the European Commission autumn 2020 economic forecast.

Note: Countries are presented in increasing order of the average annual variation of the Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER) based on the ULC deflator over the years 2017 to 2019. The REERs and the Nominal Effective Exchange Rate (NEER) are computed vis-à-vis 37 trading partners. The GDP-based REER index level is expressed as percentage difference with respect to a benchmark representing the REER consistent with economic fundamentals. The reading in the graph gives the gap of the observed REER level with respect to the REER benchmark level: positive index values indicate overvaluation, and negative index values undervaluation.

The growth of export market shares decelerated in 2019 and is expected to further fall for a majority of Member States. In 2019, no Member State recorded export market share losses below the scoreboard threshold (based on cumulated share change over 5 years). The COVID outbreak is shaping a much different trade environment, with implications for export market shares.

·Export market shares in 2020 are expected to fall in about half of the EU Member States. The crisis is reducing more markedly intra-EU trade as compared with extra-EU trade. This is because the COVID crisis has so far impacted more strongly the EU compared with other world areas. As EU countries trade mainly among themselves, their major export markets have shrunk compared with that of other world areas, which also implies a loss of market shares for a majority of EU countries.

·Export market shares fall most markedly for countries that export intensively services, notably tourism. Trade is falling especially in services, notably tourism which is strongly affected by restrictions on foreign travel and changed behaviour of consumers. In 2020, export market shares are forecast to decline the most in Croatia, Cyrus, Greece, France, Italy, Portugal and Spain, all characterised by heavy dependence on the battered tourism sector. Instead, Germany and the Netherlands are forecast to gain export market shares.

3.2 Private debt and housing markets

Private sector debt as a share of GDP has been falling in a majority of Member States until 2019 amid favourable economic developments but debt levels remain elevated in some countries. Eleven Member States exceeded the scoreboard threshold for total private debt in 2019, compared to 12 in 2018: Cyprus, Denmark, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Sweden record private debt-to-GDP ratios of over 200%, reflecting also the high importance of multinational enterprises and special purpose vehicles in several of those countries. Belgium, Finland, France and Portugal record lower levels but are also beyond the threshold. Debts differ widely across countries in light of structural country-specific factors which justify such differences. However, debts appear high in some EU countries also when compared with benchmarks that account for these country specific economic fundamentals. In some countries debts appear high also with respect to prudential thresholds.

·Private sector deleveraging continued in 2019 with most EU countries recording lower private debt ratios. Reductions in the debt-to-GDP ratio between 2018 and 2019 were mainly accounted for by nominal GDP growth (“passive deleveraging”), as borrowing accelerated in a growing number of countries in recent years.

·In recent years, borrowing was increasingly dynamic especially for the household sector. Despite mostly positive net credit flows, debt-to-GDP ratios for non-financial corporations (NFCs) have been falling in all EU countries between 2018 and 2019 except Denmark, Finland, France Germany, Luxembourg and Sweden. For what concerns households, reductions in debt ratios were observed in only about half of the Member States. Over recent years, the dynamics of the debt stock (transactions affecting the stock of credit and outstanding debt securities) has been relatively strong for what concerns households (see Alert Mechanism Report 2020). The same pattern was observed again between 2018 and 2019.

·NFCs debt remained above benchmarks in a number of countries in 2019. In Belgium, Cyprus, Denmark, France, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Malta, Portugal, Spain and Sweden, NFC debts have been above levels justified by both economic fundamentals and prudential thresholds. NFC debt is expected to hoover close to prudential thresholds in Austria, Croatia, Greece and Italy and to continue to exceed prudential levels in Finland in 2020 (

Graph 16

). In a number of countries, notably Belgium, Cyprus, Ireland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, NFC debt is significantly impacted by cross-border intra-company and special purpose entities’ debt.

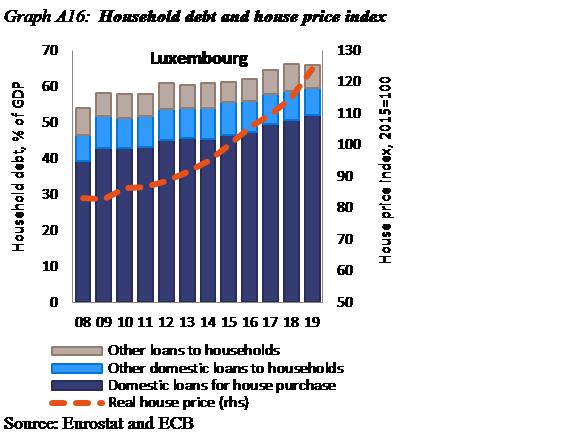

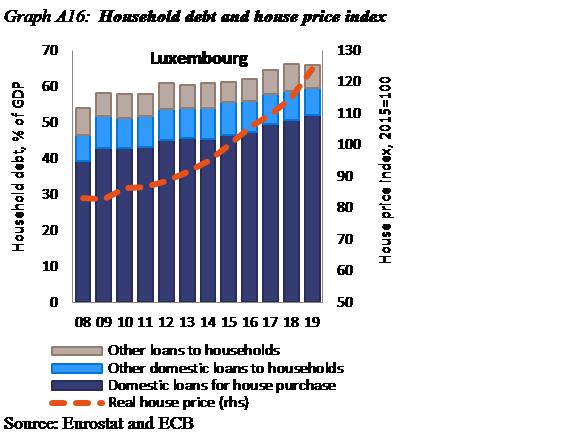

·Household debt remained above benchmarks in several Member States in 2019. In Denmark, Finland, France, Greece, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and Sweden debt levels are above both the fundamental-based benchmark and the prudential thresholds (

Graph 21

). Household debt exceeds prudential levels in Belgium and Cyprus and are close to prudential thresholds in Austria, Germany and Italy. In some countries, debt ratios for the household sector appear considerably higher when computed as a share of household gross disposable income. This is the case of Ireland, Luxembourg and Malta.

In 2020, private debt ratios appear on the rise in most Member States, notably for what concerns NFCs. Estimates of debt-GDP ratios for NFCs and households (based on available information from monthly data for what concerns debt stocks) point to non-negligible increases in most EU countries. Such increase in debt ratios is largely the mechanical result of reduced GDP figures at the denominator of the ratio. However, in particular for what concerns NFCs, dynamics in the debt stock also play a role. Net credit flows are indeed expected to be large in 2020 in most EU countries, notably in Belgium, Finland, France, Ireland, Luxembourg, Spain and Sweden, in some cases markedly larger than in 2019.

Graph 16: Non-financial corporations debt

Source: Eurostat sectoral financial balance sheet accounts – loans (F4) plus debt securities (F3), AMECO and Commission services estimates (see Box 1).

Note: Countries are presented in decreasing order of the NFCs debt-to-GDP ratio in 2019. Numbers below the country codes indicate the year when that debt ratio peaked. For the definition of fundamental-based benchmarks and prudential thresholds see footnote 34.

For what concerns NFCs, sharp losses and liquidity shortages explain the increased borrowing needs in 2020.

·Debt ratios in 2020 appear on the rise most notably in countries where the COVID-19 outbreak is denting more severely NFC profits and cash flows. In general, the countries where net operating profits of corporations are expected to fall substantially in 2020 tended to be the same recording the strongest net credit flows (transactions) as a share of 2019 GDP (see

Graph 20

).

·Increased borrowing was needed to finance NFC working capital to build liquidity buffers, implying that NFC net debt did not raise as much as gross debt. Part of the borrowing was used to replenish and beef up cash buffers to cope with the increased uncertainty on the economic situation and to profit from temporary special measures to support credit flows. Borrowing to finance investment has played a minor role. In all, despite the substantial borrowing in 2020, the saving position of corporations is expected not to fall substantially. Moreover, due to reduced investment, corporate net savings are expected to rise in all EU countries (see

Graph 11

).

·Borrowing was facilitated by a number of policy measures. In addition to ample liquidity provision to banks by monetary authorities and an adaptation of prudential regulations, government credit guarantees helped maintaining credit flows, notably for small and medium enterprises.

·Debt repayment moratoria contribute to inflate debt dynamics in 2020. The delay in debt repayment by NFCs allowed by the moratoria across the EU, either as a government measure or as voluntary initiative by lenders, imply a mechanical increase in the dynamics of the debt stock. This is confirmed by a much stronger positive relation in 2020 between the change in NFC debt and the “pure new” MFI lending (excluding renegotiations and repayments) than the one observed in 2019 (see

Graph 17

and

Graph 18

). In 2020, the dynamics of debt were therefore less affected by repayments as compared with the past, arguably as a result of moratoria.

·Going forward, dynamics in the debt-to-GDP ratio are expected to be more contained for a number of reasons. First, the mechanical increase in debt ratios due to a reduction in the denominator is expected to be short-lived as the debt-GDP ratio in 2020 increases mainly on account of a temporary cyclical downturn (see

Graph 19

). Second, the exceptional measures put in place in 2020 will be gradually phased out. The expiration of debt moratoria will lead to increased repayments. The phasing out of credit guarantees will imply reduced borrowing possibilities for firms under dire conditions. Moreover, survey data suggests that going forward, a tightening of lending conditions may take place. Third, NFCs will have the possibility to run down liquidity buffers as an alternative to new borrowing.

·Protracted hardship for the NFC sector may dent on investment and debt repayment prospects. Profitability will remain deeply affected especially in service sectors exposed to the pandemic. This may not only imply subdued investment, but also difficulties in paying back existing debt. More generally, the expiration of debt moratoria will imply a higher debt burden because of accumulated interests.

|

Graph 17: New MFI loans to NFCs vs evolution of NFC debt-to-GDP, 2019

|

Graph 18: New MFI loans to NFCs vs evolution of NFC debt-to-GDP, 2020

|

|

|

|

Source: ECB MIR database, AMECO, Eurostat and Commission services calculations (see also Box 1 for private debt forecasts).

Note: New MFI loans refer to “pure new” credit by monetary financial institutions (MFIs) and comprises only new loans extended by MFIs to NFCs, excluding renegotiations and repayments. It excludes Belgium, Cyprus and Luxembourg as outliers, and Bulgaria, Denmark, Ireland and Sweden due to data availability.

|

Graph 19: Decomposition of the change in NFC debt-to-GDP (2019 – 2020)

|

Graph 20: Evolution of gross operating surplus in 2020 and net credit (transactions) to NFCs

|

|

|

|

|

Source: AMECO, Eurostat and Commission services estimates (see Box 1) and calculations based on ECB monthly data on MFI loans and debt securities transactions (flows) with the private sector from the BSI database, European Commission autumn 2020 economic forecast.

|

|

Note: Net credit flows (debt transactions) correspond to transaction of loans (F4) and debt securities (F3) from the Eurostat sectoral financial transactions accounts. NFC gross operating surplus not available for Bulgaria, Croatia and Malta.

|

Graph 21: Household debt

Source: Eurostat sectoral financial balance sheet accounts – loans (F4) plus debt securities (F3), AMECO and Commission services estimates (see Box 1).

Notes: Countries are presented in decreasing order of the households debt-to-GDP ratio in 2019. Numbers below the country codes indicate the year when that debt ratio peaked. For the definition of fundamental-based benchmarks and prudential thresholds see footnote 34.

Regarding households, the COVID-19 outbreak appears to have led to more subdued borrowing dynamics in light of reduced income prospects and increased savings.

·Net credit flows (debt transactions) to households are expected to be close to zero or moderate in 2020 for most EU countries. As shown in

Graph 22

, the growing household debt-to-GDP ratios across the board are largely driven by the slump in GDP and not by credit and security transactions, which are rather limited, and appear to have shrunk in nearly all EU countries compared with 2019. Decelerations in households borrowing appear justified by worsened income prospects for households coupled by increased savings, partly precautionary and partially because of restrictive measures hampering consumption possibilities. Cross-country differences are possibly linked to the severity of lock-downs and a halt in house purchases, different degrees of government support to household incomes and credit conditions, and also to housing market conditions.

·The deceleration in household borrowing is taking place despite the effect of moratoria. As with NFCs, debt moratoria has a positive effect on the evolution of the debt stock on account of lower repayments. Because of this effect, the stock of household debt appears to be falling at reduced speed.

·Household debt dynamics are likely to remain subdued and repayment difficulties may emerge as labour markets deteriorate. Despite continued supportive financial conditions and government measures to cushion the fallout of the crisis on the labour market and on households, household incomes will remain under pressure. In particular, after having declined until 2020, unemployment rates are forecast to increase across the board through 2021. That will reflect also job losses following the phasing out of the measures that governments have taken to cushion the impact of the pandemic, notably subsidised short-time work schemes, which are supposed to be temporary to avoid keeping jobs in unviable firms. Increased debt repayment difficulties for households could materialise also in countries already characterised by a relatively high household debt burden (

Graph 23

).

|

Graph 22: Decomposition of the change in household debt-to-GDP (2019 – 2020)

|

Graph 23: Household debt and unemployment

|

|

|

|

|