EUROPEAN COMMISSION

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Brussels, 9.7.2020

SWD(2020) 126 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

Accompanying the document

REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS

Report on Competition Policy 2019

{COM(2020) 302 final}

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

Accompanying the document

REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS

Report on Competition Policy 2019

Table of Contents

I.

LEGISLATION AND POLICY DEVELOPMENTS

1.

Antitrust and cartels

1.1.

Guidance in antitrust and cartel proceedings

1.2.

Important judgments by the European Union Courts

1.3.

The fight against cartels remains a top priority

1.4.

Continuing close cooperation within the European Competition Network and with national courts

2.

Merger control

2.1.

Recent enforcement trends

2.2.

Increased relevance of digital issues

2.3.

The ongoing evaluation of EU merger control

3.

State aid control

3.1.

Uptake of the State Aid Modernisation

3.2.

State Aid Modernisation continues

3.3.

Monitoring, recovery, evaluation and cooperation with national courts

3.4.

Significant judgments by the European Union Courts in the State aid area

4.

Developing the international dimension of EU competition policy

5.

External Communication

6.

The Single Market Programme

II. SECTORAL OVERVIEW

1.

Energy & environment

2.

Information and Communication Technologies and media

3.

Financial services

4.

Taxation and State aid

5.

Basic industries and manufacturing

6.

Agri-food industry

7.

Pharmaceutical and health services sectors

8.

Transport and postal services

This Staff Working Document (SWD) accompanying the 2019 Annual Competition Report reflects the main developments in EU competition policy during the year 2019 and contains a number of analyses and assessments of challenges in specific industries or for particular enforcement instruments. Consequently, the SWD does not cover the disruptive economic developments caused by the Covid-19 pandemic that broke out in early 2020, and their impact on EU competition policy.

I.LEGISLATION AND POLICY DEVELOPMENTS

Competition policy empowering citizens and businesses for the benefit of all

With more than half a billion consumers and 24.5 million companies, the internal market is one of the EU’s greatest achievements and its greatest asset. EU competition policy goes hand in hand with the development of a deeper and fairer internal market. Enforcing EU competition rules makes markets function better for the benefit of consumers - households as well as businesses - and for society as a whole. Competitive markets play an important role supporting the Commission's efforts to achieve a strong and prosperous EU. Moreover, EU competition policy aims at fostering a competition culture both within the EU, for instance by promoting competition-friendly regulation, and worldwide.

DG Competition's competition policy activities in 2019 targeted a wide range of sectors in the EU economy, thereby promoting open and efficient markets so that both businesses and citizens can get a fair share of the benefits of economic growth. Moreover, EU competition policy continued to support key political priorities of the Commission, in particular its objectives linked to the internal market, digitalisation, fair taxation, as well as energy and climate as set out in the Commission President's Political Guidelines and the Commission Work Programme. The present Staff Working Document is composed of two parts, the first part presents the main legislative and policy developments in 2019 across the three competition instruments (antitrust, including cartels, mergers and State aid), while specific actions are detailed in the sectoral overview part.

Articles 101, 102 and 106 TFEU

According to Article 101 TFEU, anti-competitive agreements are prohibited as incompatible with the internal market. Article 101 TFEU prohibits agreements with an anti-competitive object or effects where companies coordinate their behaviour instead of competing independently. However, even if a horizontal or a vertical agreement could be viewed as restrictive it might be allowed under Article 101(3) TFEU if it ultimately fosters competition (for example by promoting technical progress or by improving distribution).

Article 102 TFEU prohibits abuse of a dominant position. It is not in itself illegal for an undertaking to be in a dominant position or to acquire such a position. Dominant undertakings, as any other undertaking in the market, are entitled to compete on the merits. However, Article 102 TFEU prohibits the abusive behaviour by dominant undertakings that, for example, directly or indirectly impose unfair purchase- or selling prices or other unfair trading conditions.

Finally, Article 106 TFEU prevents Member States from enacting or maintaining in force measures contrary to the Treaty rules regarding public undertakings and undertakings to which Member States grant special or exclusive rights.

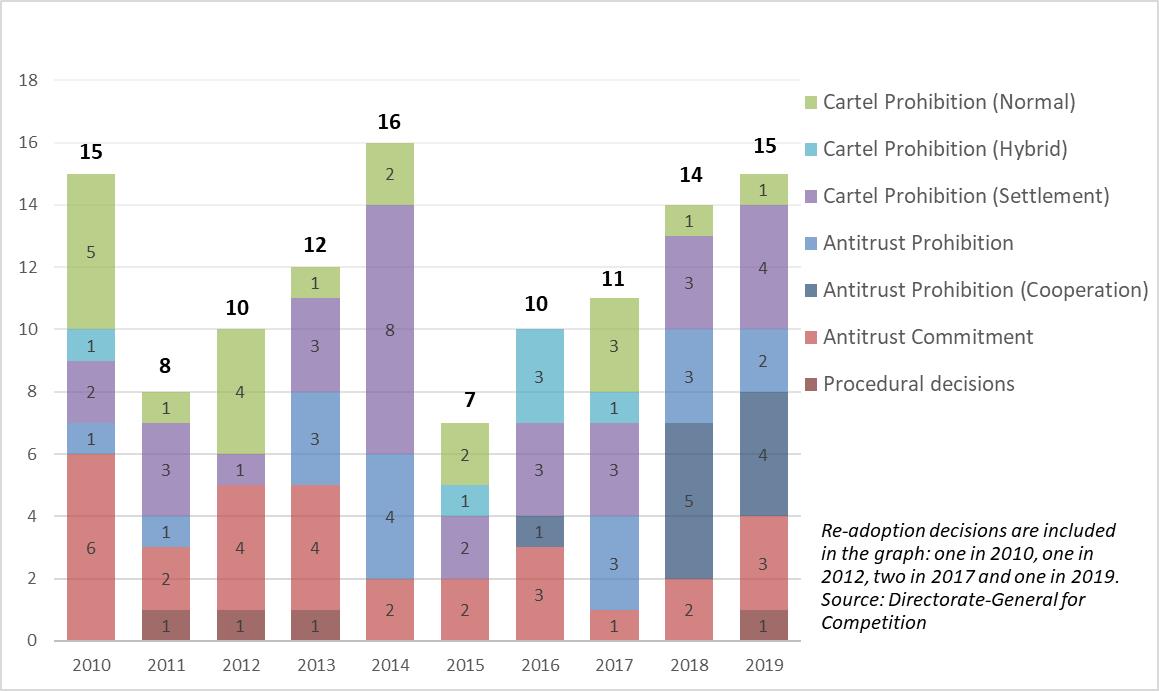

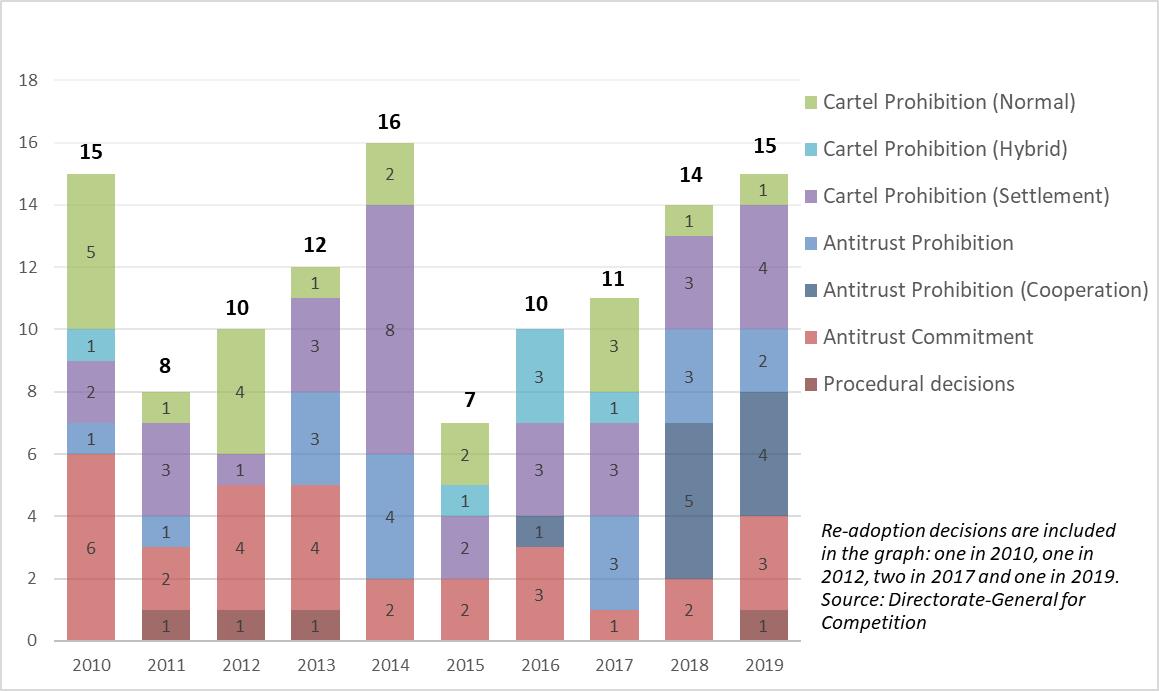

Antitrust and cartel decisions 2010-2019

1.1.Guidance in antitrust and cartel proceedings

The Commission’s enforcement in 2019 demonstrated its continued intention to strictly enforce competition rules to fight collusive agreements between undertakings and avoid that companies abuse their dominant positions to the detriment of consumers. While in parallel engaging in a thorough reflection process to assess how to boost enforcement with the tools available to it, throughout 2019 the Commission adopted a total of 15 decisions sanctioning anticompetitive conduct. This is the highest number of sanctions since Margrethe Vestager took office as Commissioner for Competition in 2015.

Importantly, 2019 also marked the Commission’s continued efforts to make competition policy more efficient, effective and responsive to the needs of modern society. In this respect, throughout 2019 the Commission successfully pursued four antitrust cases on the basis of cooperation procedures.

This voluntary practice – similar to cartel settlement but outside the context of a cartel – has proven very successful in a number of recent fining decisions. The four cases of 2019 brought the number of this type of cases to a total of ten since the first time it was used in 2016

and allowed the Commission to levy fines of almost EUR 1 billion. The use of cooperation procedures allows both the companies investigated and the Commission to substantially increase administrative efficiencies while preserving the supervisory role inherent to competition law enforcement. By voluntarily engaging in a cooperation procedure, companies benefit from fine reductions in exchange for the acknowledgment of the infringement. Moreover, companies may merit additional reductions in their fines if they also provide evidence with significant value for the investigation or design and implement remedies contributing to the improvement of competitive conditions and the good functioning of the European Single Market. The individual reductions granted so far in this type of procedures have ranged between 10% and 50%, depending on the timing of the cooperation (both in terms of the acknowledgement of liability and the evidence) as well as the extent to which the evidence provided strengthened the Commission's case. The use of cooperation procedure also results in speedier and better targeted fining decisions.

In an additional attempt to improve the effectiveness of its procedures, the Commission launched in March 2019 its “eLeniency” online tool.

eLeniency is designed to make it easier for companies and their legal representatives to submit statements and documents as part of leniency and settlement proceedings in cartel cases, as well as non-cartel cooperation cases. eLeniency allows companies and their lawyers to submit these documents – including leniency applications and settlement submissions – with the same guarantees in terms of confidentiality and legal protection as under the traditional procedure. These safeguards include the protection against discovery in civil litigation of corporate statements made under the Leniency Notice.

As regards the speed of investigations, 2019 also saw the Commission impose interim measures on chipset manufacturer Broadcom.

Designed to target “the risk of serious and irreparable damage to competition”

, interim measures had not been used for eighteen years. The interim measures decision ordered Broadcom to (i) unilaterally cease to apply certain anticompetitive provisions identified by the Commission and to inform its customers that it would no longer apply such provisions; and (ii) refrain from agreeing or enforcing the same provisions or provisions having an equivalent object or effect in other agreements with its customers. In its decision, the Commission obliged Broadcom to comply with these measures within 30 days or face a penalty of up to 10% of its total turnover.

During 2019 the Commission made substantial progress in its evaluations of the rules exempting certain vertical

and horizontal agreements

from the EU’s general competition rules. In line with the Better Regulation requirements, the Commission is following the same thorough process for the evaluation of both sets of rules. They are made up by one or two Block Exemption Regulations and a set of accompanying Guidelines.

The two workstreams have so far included the publication of the roadmaps for each review and their respective calls for contributions from stakeholders. The purpose of these evaluations is to allow the Commission to decide whether to let the rules lapse, prolong their duration or revise them. Stakeholders will be able to provide further comments at subsequent stages of the review process. The vertical and horizontal rules expire in May and December 2022, respectively. The rules applicable to categories of technology transfer agreements will also be up for review in the coming years.

The Commission also launched the review of the Motor Vehicle Block Exemption Regulation (MVBER) which will expire in May 2023 and mandates the production of an evaluation report by May 2021. In February 2019, an evaluation roadmap was published, followed by a four-week online consultation with stakeholders. In parallel, a fact-finding study has been commissioned, to allow for a better understanding of how market conditions have evolved in the motor vehicle sector over the last decade. The study, which is expected to be delivered by mid-summer 2020, will then feed into the public consultation with stakeholders, currently scheduled for late 2020.

On 9 December 2019, Executive Vice-President Vestager announced the planned review of the Commission Notice on the definition of relevant market for the purposes of Community competition law (“Market Definition Notice”),

which provides guidance as to how the Commission applies the concept of relevant product and geographic market in its ongoing enforcement of EU competition law. The main reason for launching this review is to ensure that the Notice reflects how the Commission’s and the European courts’ practice in defining markets has evolved over the past twenty years. The main objective of the review is to give guidance that remains accurate and up-to-date, setting out a clear and consistent approach to both antitrust and merger cases across different industries, in a way that is easily accessible.

1.2.Important judgments by the European Union Courts

Preliminary rulings

Ne bis in idem

The case Powszechny Zakład Ubezpieczeń na Życie concerns a request for a preliminary ruling about the interpretation of the principle of ne bis in idem, enshrined in Article 50 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, in the area of EU competition law. According to established case law, the principle of ne bis in idem precludes an undertaking being found liable or proceedings being brought against it again on the grounds of anti-competitive conduct for which it has been penalised or declared not liable by an earlier decision that can no longer be challenged.

The request was made by the Polish Supreme Court in its proceedings concerning a decision of the Polish Office of Competition and Consumer Protection (“UOKiK”) to fine Powszechny Zakład Ubezpieczeń na Życie S.A., a Polish insurance company, for abusing its dominant position on the market for group life insurance for employees in Poland by taking measures to prevent the creation or development of competition. The UOKiK imposed a fine both based on national law and on the basis of Article 102 TFEU in the same decision. The part of the fine that was based on national law covered the period of the infringement prior to Poland’s accession to the EU up to the date of UOKiK’s decision and the part of the fine based on Article 102 TFEU covered the period post accession up to the date of UOKiK’s decision.

The Polish Supreme Court asked: (i) whether Article 50 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, could be interpreted as meaning that the application of the ne bis in idem principle presupposes not only that the offender and the facts are the same but also that the legal interest protected is the same and (ii) whether Article 3 of Regulation 1/2003, read in conjunction with Article 50 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, was to be interpreted as meaning that the rules of EU competition law and of national competition law which are applied in parallel by the competition authority of a Member State protect the same legal interest.

The Court of Justice of the European Union considered the two questions together and concluded that the principle of ne bis in idem did not apply in the particular case because the UOKiK had taken a single fining decision on the basis of a concurrent application of national and EU competition law. Consequently, the "bis" component was missing. The Court stated that the protection which the principle of ne bis in idem aims to afford against the repetition of prosecution leading to a criminal sentence bore no relation to the situation in which national and EU competition law are applied in parallel in a single decision. The Court also stated, as in the Toshiba case, that competition rules at EU and national level view restrictions on competition from different angles and their areas of application do not coincide. The Court finally stated that where a national competition authority imposes two fines in a single decision in respect of an infringement of national competition law and an infringement of Article 102 TFEU, that authority must ensure that, taken together, the fines are proportionate to the nature of the infringement.

Review of cartel decisions

In 2019, the European Courts confirmed the Commission’s cartel enforcement activities across most areas: the use of the Commission’s investigative powers in inspections, the way in which the Commission conducts its cartel investigation proceedings and the use of evidence for proving infringements of EU competition law and in relation to certain aspects of the Commission’s fine calculations.

Inspections

In Bio-ethanol, the Court of Justice rejected Alcogroup’s appeal against the General Court’s 2018 judgment, where the General Court rejected as inadmissible an action for annulment against (i) an inspection decision and (ii) a subsequent letter refusing the applicant’s request to suspend the investigation. The Court of Justice confirmed that the General Court was correct to conclude that (i) the validity of an inspection decision cannot be affected by acts subsequent to its adoption, in this case by the conduct of that inspection; and that (ii) the Commission’s rejection letter could not be challenged, because this was only a preliminary act. Finally, the Court of Justice considered that the right to the protection of confidentiality of correspondence between a lawyer and his client must in principle be respected by the Commission and its inspectors, irrespective of the scope of the mandate given to them by the inspection decision. As regards the Commission’s rejection letter, the Court of Justice held that, contrary to the Akzo jurisprudence, this could not constitute a formal decision rejecting a request for confidentiality or a decision confirming an implied decision rejecting such a request.

Rights of defence

Pleas by Pometon alleging a violation of the principles of impartiality and presumption of innocence in the staggered hybrid settlement proceedings relating to the Steel Abrasives case were rejected by the General Court. In this case, the Commission adopted first a decision following the settlement procedure with the settling parties, and later on a decision following the standard procedure against Pometon, which opted out of the settlement procedure. Pometon had alleged that the Commission had acted partially and violated the presumption of innocence by referring to Pometon in the description of the facts in the settlement decision and showing bias against it in the standard proceedings leading to adopting the contested decision. The General Court held that the settlement decision did not contain any legal assessment concerning Pometon’s participation in the infringement. The references to Pometon were limited to a description of the facts. It did therefore not consider that there was a violation of the presumption of innocence as alleged. This judgment thus confirms the possibility for the Commission to pursue a staggered hybrid settlement if one party drops from the settlement.

In Retail Food Packaging, the General Court confirmed the Commission’s discretion in conducting its adversary proceedings against a suspected cartelist. Silver Plastics alleged an infringement of its procedural rights to equality of arms and to a fair trial in that examination of witnesses named by Silver Plastics and the adversarial examination of a witness used against them was, following several requests, refused. According to the General Court, an undertaking’s right to be heard was sufficiently protected by responding to the Commission’s Statement of Objections – a right to confront a key witness supporting the Commission’s findings, however, was not part of an undertaking’s rights of defence.

In Power Cables, the Court of Justice confirmed that the rights of defence and the right to a fair trial were not infringed by addressing requests for information and a statement of objections to a German-operating company in Switzerland in English (as opposed to in German). Furthermore, the Court of Justice confirmed in the same judgment that addressees of a Statement of Objections do not have the automatic right to access other parties’ responses to the same Statement of Objections. It is for the addressee to give a first indication how access to these responses would be useful for the exercise of their rights of defence.

Finding of the infringement

In all but one judgment, the General Court confirmed that the Commission acted within the boundaries of existing case law when holding undertakings liable for participating in a single and continuous infringement.

In Optical Disk Drives (ODD), the General Court confirmed the qualification of the cartel – consisting of a set of predominantly bilateral contacts – as a single and continuous infringement of Article 101 TFEU. The General Court summarised its position concerning the existence of the single and continuous infringement by recalling that the very concept of a single and continuous infringement presupposes a complex of practices. Furthermore, the General Court confirmed that the Commission has demonstrated to the requisite standard that all parties were aware or could reasonably have foreseen the conduct planned or put into effect by the other cartel participants and could therefore also be held liable for that conduct.

Moreover, the General Court confirmed in two judgments relating to Retail Food Packaging that the Commission had fulfilled the standard of proof and correctly applied the criteria for qualifying anti-competitive conduct as a single and continuous infringement. In particular, the General Court confirmed that a single and continuous infringement might concern several products belonging to distinct product markets. The General Court, therefore, fully confirmed the finding of the infringement in the decision.

In the case of Car Battery Recycling, the General Court confirmed the Commission’s findings that the addressees of the infringement decision were engaged in a purchasing cartel violating Article 101(1) TFEU. The General Court confirmed that the Commission had proven to the requisite legal standard the anticompetitive nature of the six collusive contacts in which Campine was found to have been involved. However, the General Court upheld Campine’s claim concerning a lack of proof for the entire duration of its participation in the infringement and partially annulled the Commission’s infringement decision in this respect.

In Power Cables, the Court of Justice confirmed that the General Court had not erred in law when confirming the Commission’s position that, based on the evidence available, companies had participated in the infringement and had failed to fulfil the criteria for applying the open and public distancing test. The Court of Justice also confirmed that the General Court had correctly observed that the Commission had relied not just on the absence of public distancing, but also on other factors when establishing the participation in the cartel.

Also in Power Cables, the Court of Justice partially annulled the Commission’s decision against ABB (the immunity applicant) based on the finding that the General Court failed to have regard to the evidential requirements in finding that the collective refusal to supply the power cable accessories also covered accessories for underground power cables with voltages from 110 kV and below 220 kV. The Court of Justice found that the General Court effectively relied on an unsubstantiated presumption in that regard, while leaving it to the appellants to rebut that presumption in respect of those accessories.

Reasoning for fines

In 2019, EU courts provided further guidance for the reasoning required by the Commission to impose fines on cartelists on the basis of the 2006 Guidelines on fines.

Point 37 of the 2006 Guidelines on fines state that the Commission may depart from its standard fining methodology if it is justified by the particularities of a given case or if there is a need to achieve deterrence in that particular case. In Steel Abrasives the General Court recalled that when basing itself on point 37, the Commission’s motivation should be all the more precise as it benefits from considerable discretion, and it should not discriminate in determining the fines applicable to the various participants in the same cartel. In this respect, the General Court found that the contested decision was insufficiently motivated, as it did not allow assessing whether the applicant had been treated equally to the settling parties. Exercising its power of full jurisdiction, the General Court decided to reduce the fine while confirming the infringement and Pometon’s participation in the cartel.

In relation to the imposition of fines against cartel facilitators applying point 37 of the Commission’s 2006 Guidelines on Fines, the Court of Justice upheld in the Yen Interest Rate Derivatives (YIRD) case the General Court judgment annulling the fine imposed on broker ICAP for facilitating several infringements that formed part of the YIRD cartel. While the Court of Justice accepted the characterisation of ICAP as a cartel facilitator, it was critical of the fact that a five-step process used to calculate the fine was not explained in the decision, but only disclosed during the court proceedings. The Commission had considered it necessary to establish such a methodology for the setting of the fine, instead of imposing a lump sum like in previous cases involving a facilitator, in order to ensure that the same approach was taken with regard to ICAP (non-settling) and the other settling facilitator fined in this case. The Court of Justice considered that, although the Commission is not required to provide all of the figures concerning each of the steps relating to the method of calculating the fine, it has a duty to explain the weighting and the assessment of the factors taken into account. The Court of Justice also distinguished ICAP from AC-Treuhand by pointing out that in AC-Treuhand the Commission had defined the basic amount as a lump sum and that AC-Treuhand was the sole facilitator in the cartel.

The General Court, furthermore dealt with the reasoning for an adaptation of the value of sales in its HSBC judgment in the Euro Interest Rate Derivatives (EIRD) case, a cartel case concerning the financial sector. In this particular case, the Commission could not use ‘value of sales’ in the traditional sense as the starting point for calculating the basic amount of the fine, because the trading activity in question did not produce sales as such. Instead, the Commission chose a proxy based on another metric (cash receipts), resulting in very high starting amounts. These high starting points were then reduced by a significant reduction factor (98.849%) in view of combining deterrence and proportionality of the fine. In its judgment, while confirming the infringement and accepting the proxy for value of sales retained by the Commission, the General Court annulled the fine imposed on HSBC due to insufficient reasoning of the basis for the reduction factor of 98.849%. According to the General Court, the reasoning must be sufficient to enable the undertakings concerned to understand how the Commission arrived at this specific reduction factor. The General Court must be able to carry out an in-depth review, in law and in fact, of this factor as a part of a full judicial review.

As for the application of inability to pay (ITP) principles under point 35 of the Commission’s 2006 Guidelines on Fines, the General Court annulled in one of the appeals relating to Retail Food Packaging

the fine imposed on CCPL due to an insufficient reasoning of the Commission setting out the exact level of the 25% ITP reduction granted. The Commission’s infringement decision explained the elements, which led to a reduction by 25%, but did not sufficiently quantify them, which made it impossible to assess the method used to calculate the reduction and to establish whether this reduction was proportionate.

Calculation of fines

In addition to analysing the Commission’s reasoning, the General Court also exercised in the Steel Abrasives case its unlimited jurisdiction concerning fines. In doing so, the General Court compared the situation of the appellant, Pometon, with that of the other parties in view of its involvement in the infringement, value of sales and total turnover in the last year of the infringement. As a result, while confirming the infringement, the General Court increased the fine reduction for Pometon from 60% to 75%.

In the Envelopes Cartel, the General Court, in the exercise of its unlimited jurisdiction, confirmed the fine re-imposed on Printeos for its participation in the cartel, dismissing Printeos’ pleas concerning non-discrimination and breach of the principle of equal treatment. In doing so, the General Court made a full comparison between Printeos and each one of the other parties. The General Court concluded that the Commission had respected the principle of equal treatment. Although it clarified that in the case of one other party the Commission had not correctly applied the fining methodology, this fact did not justify reducing the fine for Printeos because on the one hand, Printeos confirmed in its appeal that it did not dispute the fines imposed on the other parties and, on the other hand, the fines imposed on the other parties were final and binding. However, for equity reasons, the Court decided to award the costs of the appeal of Printeos to the Commission.

The General Court confirmed the Commission’s method for calculating the fine imposed against Sony Optiarc in the Optical Disk Drives case. In particular, the General Court rejected Sony Optiarc’s argument that the Commission had double-counted its sales by not deducting revenues passed on to Quanta (another addressee of the Commission’s infringement decision) under a revenue-sharing arrangement between the two addressees. Deducting such sales “would undermine the effectiveness of the prohibition on cartels, since it would then be sufficient for undertakings to associate themselves with a participant in the cartel in order to reduce the amount of their fine”. It also confirmed the fines imposed on all the participants for their participation in the cartel.

In Power Cables, the Court of Justice found that the General Court had not erred in law when refusing to qualify an undertaking’s individual involvement in the cartel as a “fringe” player, thus confirming the original fine calculation by the Commission, which did not reduce the undertaking’s fine by an additional 5% because Silec’s participation was not comparable to that of the fringe players in the cartel. This refusal to grant an additional 5% reduction did not discriminate against the undertaking.

Furthermore, the Court of Justice confirmed the Commission’s application of point 18 of the Fining Guidelines, which allow for an adjustment of the value of sales used for calculating the basic amount of a fine in case of a cartel whose geographic scope goes beyond the EEA in order to properly reflect the undertaking’s participation in the infringement. In addition, the Court of Justice confirmed the Commission’s methodology to set the value of one undertaking’s sales based on an apportionment of sales between two companies belonging to the same group.

Finally, the General Court also confirmed the Commission’s approach to increase the value of purchases in the Car Battery Recycling purchasing cartel by 10% under point 37 of the 2006 Guidelines on Fines. This uplift was aimed at taking into account the specific nature of a purchasing cartel. In such a case, the value of purchases was likely to underrepresent the economic significance of the infringement. This is because the more successful a purchasing cartel is in lowering prices, the lower its fines would be under the standard approach. The General Court also found that the 10% uplift was sufficiently reasoned in the decision and that the fact that the Commission did not announce the intended fine increase in the Statement of Objections, but in a letter sent to the parties after the adoption of the Statement of Objections, did not infringe the parties’ rights of defence or the principle of good administration. The General Court also confirmed the Commission’s decision to grant Eco-Bat a 30-50% reduction under point 26 of the Leniency Notice and Recylex a 20-30% reduction, because Recylex had only been the second undertaking to provide evidence that had significant added value.

1.3.The fight against cartels remains a top priority

Cartels are secret agreements between sellers or buyers of the same product or service. They are made with the objective of fixing prices, limiting output or allocating clients and suppliers. Cartels harm the consumers at all levels of the value chain and the economy as a whole. Cartelists charge inflated prices, limit the choice of the consumers and block innovation. Only undistorted competition guarantees that scarce resources are used in the most efficient way. The Commission's action to stop hard core cartels prevents companies from continuing to profit from illegal overcharges and thereby contributes to fair and balanced business relationships. The significant sanctions imposed by the Commission deter companies from entering into cartels or from remaining in cartels, sending a clear signal that operating a cartel will ultimately not pay off.

The Commission's strong enforcement record against hard-core cartels continued in 2019 and remains strong and effective with five decisions and fines in excess of EUR 1.4 billion. The Commission adopted cartel decisions in important sectors, which directly affected EU consumers and EU business, notably in car parts and food products. Four of the five decisions issued in 2019 came under the settlement procedure, which again proved to be a successful and efficient tool to resolve cartel cases.

The Commission fined two producers of car safety equipment – Autoliv and TRW (Sanyo received immunity) – a total of EUR 368 million for participating in a cartel. It was the second time that car safety equipment suppliers were fined for entering into illegal cartel arrangements. On this occasion the parties exchanged commercially sensitive information and coordinated their market behaviour for the supply of seatbelts, airbags and steering wheels. All three parties acknowledged their involvement in cartel conduct and agreed to settle. The cartel is likely to have hurt EU consumers and had an adverse impact on the competitiveness of the EU automotive sector. This case represents the 11th decision in the car parts sector and shows the Commission is able to produce the ‘domino effect’ of successive cases within its existing framework.

The Commission also continued its work against cartels in the financial sector. In two settlement decisions it fined five banks at total of EUR 1.07 billion for taking part in two cartels in the Spot Foreign Exchange (Forex) market for eleven currencies, including the Euro, British pound, US dollar and Japanese yen. The first decision (the so-called ‘Three Way Banana Split’ cartel) imposed a total fine of EUR 811 million on Barclays, The Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS), Citigroup and JPMorgan. The second decision (the so-called ‘Essex Express‘ cartel) imposed a total fine of just under EUR 258 million on Barclays, RBS and MUFG Bank (formerly Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi). The investigation revealed that individual traders in charge of Forex spot trading (where transactions are executed on the same day at the prevailing exchange rate) had, on behalf of their respective banks, exchanged sensitive information and trading plans, and occasionally coordinated their trading strategies through various online professional chatrooms. With the adoption of these decisions, eight decisions in total were adopted in the financial sector. This illustrates the cyclical nature of cartel enforcement where cases in a particular sector can come in waves.

In the agri-food sector, the Commission imposed a total fine of EUR 31.7 million on Coroos and Groupe CECAB (Bonduelle received immunity). The three parties were involved for more than 13 years in a cartel for the supply of certain types of canned vegetables to retailers and/or food service companies in the EEA. The three companies admitted their involvement in the cartel and agreed to settle the case. The cartel lasted from 2000 to 2013 and was composed of three agreements: one covering private label sales of canned vegetables such as green beans, peas, peas-and-carrots mix, vegetable macedoine to retailers in the EEA; a second one covering private label sales of canned sweetcorn to retailers in the EEA; and a third one covering both own brands and private label sales of canned vegetables to retailers and to the food service industry specifically in France. The nature of the product, the long duration and the EEA wide scope meant that the cartel had a direct and significant impact on EU consumers.

The Commission also re-adopted a cartel decision against five Italian manufacturers of reinforcing steel bars for concrete, namely AlfaAcciai, Feralpi Holding, Ferriere Nord, Partecipazioni Industriali (Riva Fire) and Valsabbia Investimenti / Ferriera Valsabbia. The Commission imposed total fines of EUR 16.074 million for the companies' participation in a price fixing cartel between December 1989 and July 2000. The case demonstrates the Commission’s practice of re-adopting decisions when annulled on procedural grounds in order to ensure proper enforcement of the competition rules and appropriate deterrence.

Also in 2019, the Commission revealed greater details of the recent steps it has taken to reinforce its ex officio policy in the detection and fight against cartels. The enhanced risk of detection will not only lead to more ex officio cases but will also serve to encourage leniency applications. Three key measures were put in place. First, the development of new digital investigation methodologies, which allow enhanced intelligence gathering and improved investigative data analysis. A dedicated unit in DG Competition was set up, staffed by professionals specialised in such practices. Second, the creation and the management of a centralised intelligence network from multiple information channels - other Commission DGs, other EU institutions and other non-competition national enforcers. Third, the launching of the anonymous whistle-blower tool, which encourages informants to come forward safely knowing that their identities will be protected.

Moreover, the Commission launched on 19 March 2019 eLeniency in order to streamline the way leniency materials can be submitted to it. This new and modern tool reduces the costs and the burden of doing so. Under the EU leniency programme, companies or their lawyers can approach the Commission either by email to a functional mailbox or through the oral procedure to submit their leniency statements. While the email is user-friendly but not secure, the oral procedure ensures a high protection against discovery but is costly, time consuming and burdensome for both the law firms and the Commission.

eLeniency is a third way to deliver the leniency submissions and offers the same high level of protection as the oral procedure but in an user friendly manner from the company's or the law firm's computer directly in the Commission's server. This tool can be used as well for documents submitted in the context of the settlement or cooperation procedures. Since the launch of eLeniency the Commission has received a high number of statements through it.

Cartel decisions 2019

|

Case name

|

Adoption date

|

Fine imposed

EUR

|

Undertakings concerned

|

Prohibition Procedure

|

|

Occupants Safety Systems (II)

|

05/03/2019

|

368 277 000

|

3

|

Settlement

|

|

Forex (Three Way Banana Split)

|

16/05/2019

|

811 197 000

|

5

|

Settlement

|

|

Forex (Essex Express)

|

16/05/2019

|

257 682 000

|

4

|

Settlement

|

|

Reinforcing steel bars

re-adoption

|

04/07/2019

|

16 074 000

|

5

|

Prohibition

|

|

Canned Vegetables

|

27/09/2019

|

31 647 000

|

3

|

Settlement

|

1.4.Continuing close cooperation within the European Competition Network and with national courts

Cooperation with national competition authorities within the European Competition Network

Since 2004, the Commission and the national competition authorities in all EU Member States cooperate with each other in the European Competition Network (ECN). The objective of the ECN is to build an effective legal framework to enforce European competition law against companies who engage in cross-border business practices which restrict competition.

In 2019, the Commission continued to ensure the coherent application of Articles 101 and 102 through the ECN. Two of the key supporting cooperation mechanisms in Regulation 1/2003 are the obligation on national competition authorities to inform the Commission about a new investigation at the stage of the first formal investigative measure and to consult the Commission on envisaged decisions. In 2019, 138 new investigations were launched within the network and 95 envisaged decisions were submitted, compared to 165 new investigations and 75 envisaged decisions in 2018. These figures include Commission investigations and decisions, respectively.

On top of the cooperation mechanisms set out in Regulation 1/2003, other ECN cooperation work streams ensure a coherent enforcement of the EU competition rules. The network meets regularly to discuss cases, policy issues, as well as matters of strategic importance. In 2019, 28 meetings across horizontal working groups and sector-specific sub-groups were organised, where competition authorities’ officials exchanged views.

Directive (EU) 2019/1 of the European Parliament and of the Council to empower the competition authorities of the Member States to be more effective enforcers and to ensure the proper functioning of the internal market

The ECN+ Directive

empowering Member States' competition authorities to be more effective enforcers of EU competition rules in the field of antitrust entered into force on 4 February 2019. The Directive is based on the Commission proposal of March 2017

following a public consultation between November 2015 and February 2016.

The ECN+ Directive will ensure that when applying the same legal provisions – the EU antitrust rules – national competition authorities have the effective enforcement tools and the resources necessary to detect and sanction companies that infringe Articles 101 and 102 TFEU. It will also ensure that they can take their decisions in full independence, based on the facts and the law. The new rules contribute to the objective of a genuine single market, promoting the overall goal of competitive markets, jobs and growth.

The Commission will monitor the transposition process and assist the Member States in incorporating the Directive into national law by 4 February 2021.

Empowering NCAs to become more effective enforcers

Once transposed by Member States into national law, NCAs will:

•

benefit from minimum guarantees of independence when applying EU competition rules;

•

have the basic guarantee of the human and financial resources they need to perform their tasks;

•

have an effective investigative and decision-making toolbox, including to gather digital evidence stored on mobile devices;

•be able to impose deterrent fines, for example companies will no longer be able to escape fines by restructuring;

•

have effective leniency programmes in place which encourage companies to report cartels throughout the EU;

•

provide each other with mutual assistance so that, for example companies with assets in other Member States cannot escape from paying fines.

The importance of companies' fundamental rights is underlined: appropriate safeguards will be in place for the exercise of NCAs' powers, in accordance with the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights and general principles of EU law.

Cooperation with national courts

Effective overall enforcement of antitrust rules in the EU, for the benefit of both EU households and businesses, requires interplay between public and private enforcement. In addition to its cooperation with NCAs in the context of the ECN, the Commission also continued its cooperation with national courts under Article 15 of Regulation 1/2003. The Commission helps national courts to enforce the EU competition rules in an effective and coherent manner by providing case-related information or an opinion on matters of substance or by intervening as amicus curiae in proceedings pending before the national courts.

Following approval from the concerned courts, the Commission publishes its opinions and amicus curiae observations on its website.

Private enforcement

Directive 2014/104/EU on antitrust damages actions (Damages Directive)

aims at ensuring that anyone harmed by infringements of the EU competition rules can effectively avail itself of the right to compensation before national courts.

The deadline to implement the Damages Directive in Member States' legal systems expired on 27 December 2016. All Member States had transposed the Directive by the end of the 2nd quarter 2018 and the Commission could close all the infringement proceedings previously opened for non communication of implementing measures. The Commission is currently assessing the implementing measures.

In addition, as foreseen in Article 16 of the Damages Directive and following a targeted consultation of stakeholders, the Commission adopted in August 2019 guidelines for national courts on how to estimate the share of overcharge which was passed on to the indirect purchaser ("Passing-on Guidelines").

Furthermore, between July and October 2019 the Commission consulted stakeholders on a draft communication on the protection of confidential information for the private enforcement of EU competition law by national courts.

The Commission is in the process of assessing the contributions received during the consultation period.

Finally, as foreseen in Article 20 of the Damages Directive, by the end of 2020, the Commission will submit a report about the implementation of the Damages Directive to the European Parliament and the Council.

EU merger control

The purpose of EU merger control is to ensure that market structures remain competitive while enabling smooth restructuring of the industry. This applies not only to EU-based companies, but also to any company active on the EU markets. Industry restructuring is an important way of fostering efficient allocation of production assets. However, there are also situations where industry consolidation can give rise to harmful effects on competition, taking into account the merging companies' degree of market power and other market features. EU merger control ensures that changes in the market structure which lead to harmful effects on competition do not occur.

EU merger control seeks to maintain open and competitive markets, which is the best way to ensure that businesses and final consumers obtain fair outcomes. It strives to protect all aspects of competition. As a result, merger control helps to preserve market structures, in which companies compete not only on price, but also on other competitive parameters such as quality and innovation. Moreover, the Commission takes due account of the increased digitisation of our economies.

EU merger control contributes to ensure that all firms active in EU markets can compete on fair and equal terms. Notified transactions which may distort competition are subject to close scrutiny by the Commission. If necessary to protect competition, the merging firms have the possibility to dispel competition concerns by offering commitments. If adequate and sufficient commitments cannot be found or agreed upon, the Commission shall prohibit the transaction.

In its assessments, the Commission also takes into account efficiencies brought about by mergers, which may have positive effects on costs, innovation and other aspects, provided that such efficicencies are verifiable, merger-specific and likely to be passed on to consumers.

As highlighted in previous reports on competition policy, the Commission continuously evaluates the substantive and procedural rules that make up the legal framework for merger control. Such reflections are conducted both internally, based on experience, and by using external input. In this context, the Commission regularly assesses concerns and suggestions for further improvements expressed by stakeholders.

EU merger control, and more generally EU competition policy, significantly contributes to the competitiveness of the EU economy and of EU companies. Competition enables growth, promotes efficiency and stimulates innovation. It ensures that EU companies have the incentive to invest more, to innovate, to limit their costs, to offer better products. This contributes to their success – at home as well as globally.

1.5.Recent enforcement trends

In 2019, 382 mergers were notified to the Commission. After years of continuous and significant increase in the number of notifications received (including an all time record in 2018 with the highest number of notifications ever received), the number of notifications remained in 2019 at a very high level despite a small decrease compared to 2018. While in the period 2010-2014, the Commission received on average 290 notifications per year, in the period 2015-2019 the yearly average increased to 375. Moreover, there were 28 reasoned pre-notification submissions by notifying parties, requesting referral of a case from the Commission to a national competition authority or vice versa.

Like in the previous years, most mergers notified in 2019 did not raise competition concerns and could be processed speedily. The simplified procedure was used in 77% of all notified transactions in 2019, showing the continuous positive impact of the simplification package adopted by the Commission in December 2013. The proportion of simplified cases in the period 2004-2013 was substantially lower, at 59%.

Nevertheless, 2019 involved intensive work by the Commission both due to the large number of notified transactions and the complexity of a significant number of cases. An increasing number of notified transactions concerned already concentrated industries, such as basic industries (steel, copper or aluminium) or the railway sector. This required the Commission to carefully assess their potential impact on competition, employing sophisticated quantitative techniques and comprehensive qualitative investigations.

In 2019, the Commission opened in-depth investigations (second phase) in eight cases. These cases concerned diverse sectors such as plane manufacturing, fuel and other petroleum products, TV distribution and ship building.

The Commission adopted 362 merger decisions in 2019,

and intervened in 19 cases, a slightly lower number than previous years but that remains in the 5-7% range (out of total decisions adopted) of previous years.

In 2019, three mergers were prohibited, ten mergers were cleared subject to commitments in first phase and six were cleared with remedies after a second phase. In 2019 the Commission did not adopt any unconditional clearance decision after a second phase investigation. In three cases the Commission had to adopt prohibition decisions since the remedies proposed by the Parties were unsuitable to address the significant competition concerns identified by the Commission. Finally, in 2019, no case was abandoned during the in-depth investigation.

Most remedies accepted by the Commission in 2019 consisted of divestitures of tangible or intangible assets.

This confirms the Commission’s general preference for structural remedies in merger cases as best suited to address in a durable manner competition concerns arising from a concentration. The prohibition decisions adopted in 2019 are a good illustration of the need for sound and solid remedies to solve the important competition concerns that some transactions give rise to. For instance, in Siemens/Alstom the parties chose to propose a remedy package which was inadequate in scope, very complex and gave rise to significant dependencies and implementation risks. This proposal failed to address the competition concerns, and the Commission had no choice but to prohibit the merger. This is in contrast with other cases such as Harris/L3 where the parties offered straightforward divestitures of a viable business which fully alleviated the competition concerns. In a few cases in 2019, the Commission accepted non-divestiture remedies,

where they were considered to solve effectively the underlying competition concerns.

Moreover, in 2019 the Commission continued its efforts to enforce procedural obligations under the EU Merger Regulation.

In 2019 the Commission imposed a fine of EUR 52 million on General Electric for providing incorrect information during the review of its acquisition of LM Wind, and a fine of EUR 28 million on Canon for partially implementing its acquisition of Toshiba before notification and approval by the Commission (so-called gun jumping). These decisions follow the fine of EUR 110 million imposed on Facebook in 2017 for providing misleading information during the review of its acquisition of WhatsApp

, and the fine of EUR 124.5 million imposed on Altice in 2018 for implementing its acquisition of PT Portugal before notification or approval by the Commission (so-called gun jumping).

Two other procedural infringement cases were under investigation in 2019. One against Merck GmbH (including Sigma-Aldrich) concerning their alleged provision of incorrect and/or misleading information during the Commission's merger review, and one against Telefonica for breach of the commitments given in relation to its acquisition of E-Plus in 2014.

Merger cases 2010-2019

1.6.Increased relevance of digital issues

The Commission increasingly has to assess mergers involving digital issues, both in the digital and traditional industries, and their number is likely to continue growing. That is why the Commission welcomed the input provided by the three independent Special Advisers in their report of April 2019 on digitisation and competition law. The report contained specific analysis and suggestions on merger control issues, both from a jurisdictional and a substantive perspective.

The Special Advisors believe that a change to the EU Merger Regulation is not necessary at this point in time. Regarding jurisdiction, the Special Advisers consider it premature to amend the notification thresholds of the Merger Regulation to cater for acquisition of small but valuable start-ups. As regards substantive merger assessment, the Special Advisers find that the current test remains a sound basis for assessing mergers in the digital economy. However, they propose to revisit certain theories of harm, to assess acquisitions of small start-ups by dominant platforms or ecosystems, in particular where such acquisition can eliminate a potential competitive threat and further lock users within their ecosystem. The conclusions and recommendations in the report will be duly considered in the ongoing reflection process how to address competition aspects in the digital economy.

1.7.The ongoing evaluation of EU merger control

EU merger control has three main objectives: i) to ensure that the Merger Regulation covers all types of concentrations that may significantly affect the internal market; ii) to deal as efficiently as possible with those types of cases which typically are unlikely to raise competition concerns, cutting red tape where possible for undertakings, and iii) to allow investigating efficiently and comprehensively those cases that may bring competitive harm, adopting sound decisions grounded on facts, evidence and economic analysis; where concerns are confirmed, they need to be fully and effectively solved before letting the merger go ahead.

In 2016, the Commission launched an evaluation of selected procedural and jurisdictional aspects of EU merger control. This evaluation, which is still ongoing, seeks to explore two areas where there may be some scope for improvements of EU merger rules. The evaluation builds notably upon the results of the public consultation on the 2014 Commission White Paper "Towards more effective EU merger control",

and focusses on four topics, namely (i) possible further simplification of EU merger control, (ii) the functioning of the jurisdictional thresholds, (iii) the functioning of the referral system, and (iv) specific technical aspects.

Two public consultations were held in 2017

and 2018 whose results will feed into the evaluation together with the findings in the Special Advisers’ 2019 Report.

Moreover, the Commission is monitoring, as part of its evaluation, the experience of the Austrian and German jurisdictions where additional jurisdictional thresholds were introduced in their merger control systems in 2017. The Commission is currently carrying out further research on the different topics covered by the evaluation.

2.4.

Significant judgments by the European Union courts in merger control

In 2019, the EU Courts adopted two judgments in the field of merger control.

In its judgment of 16 January 2019, the Court of Justice upheld the General Court’s judgment annulling the Commission’s decision prohibiting the acquisition of TNT Express by UPS due a to procedural irregularity. The Court concluded that the General Court was entitled to find that UPS’s rights of the defence had been infringed in so far as the Commission had not disclosed, during the administrative procedure, the amendments introduced in an econometric model it later relied upon in its merger decision.

In its judgment of 23 May 2019, the General Court dismissed KPN’s action for annulment of the Liberty Global/Vodafone/Dutch JV conditional clearance decision. The General Court considered that the Commission’s approach not to further segment the market for premium pay TV sports channels was correct. The General Court also validated the Commission’s assessment concluding that the merged entity would not have the ability to engage in input foreclosure, based on the lack of significant market power in the upstream market.

State aid control is an integral part of EU competition policy and a necessary safeguard to preserve effective competition and free trade in the single market.

The Treaty establishes the principle that State aid which distorts or threatens to distort competition is prohibited in so far as it affects trade between Member States (Article 107(1) TFEU). However, State aid, which contributes to well-defined objectives of common interest without unduly distorting competition between undertakings and trade between Member States, may be considered compatible with the internal market (under Article 107(3) TFEU).

The objectives of the Commission's control of State aid are to ensure that aid is growth-enhancing, efficient and effective, and better targeted in times of budgetary constraints and that aid does not restrict competition but addresses market failures for the benefit of society as a whole. In addition, the Commission acts to prevent and recover State aid which is incompatible with the internal market.

1.8.Uptake of the State Aid Modernisation

Since 2014, as part of the State Aid Modernisation (SAM), there has been a surge in State aid granted without prior notification to the Commission, indicating an important reduction in red tape. The 2019 State Aid Scoreboard confirms that modernisation has led to quicker implementation of public support by Member States. This is possible due to the General Block Exemption Regulation (GBER), adopted in the context of the State aid reform, which simplifies the aid-granting procedure for Member States by authorising - without prior notification - a wide range of measures fulfilling certain criteria and specific EU objectives in the common interest. For the aid categories covered by the GBER, only cases with the largest potential to distort competition in the single market have to be notified.

As shown in the graph below, expenditure under GBER represented in 2018 approximately 45 billion EUR, entailing an increase of some 123% compared to 2013. Approximately 89% of all measures with reported expenditure (that is to say not only new measures), fell under the block exemption in 2018.

The 2014 GBER introduced new aid categories and to a large extent, the reported increase in expenditure of GBER measures reflects the impact of the new Regulation. In 2018, as compared to 2014, total GBER spending for aid to culture and heritage conservation has increased dramatically(+ 805%). Large increases were also recorded for environmental protection and energy savings (+95.7%), for research, development and innovation (+74.3%) and for aid to compensate damages caused by natural disasters (+130.7%). However, the GBER expenditure has decreased for regional development (- 11.1%). The GBER was further extended in 2017, especially as regards aid to ports and airports (included in the category Sectoral development). It is therefore to be expected that block-exempted aid as a share of total aid granted by Member States will increase even further in the coming years.

GBER State aid expenditure by objective in the EU, excluding aid for agriculture, fisheries and railways

The growing share of spending falling under the GBER and registered by the Commission implies that on average the Member States implement State aid measures much more quickly than in the past. The average time to implement State aid measures decreased from about 2.2 months in the pre-SAM period to 0.6 months in the post-SAM period. However, notified measures that are still subject to scrutiny tend to cover bigger budgets and spending than in the past, in line with the Commission's approach to be 'big on big things and small on small things'. The median annual budget for notified measures is higher than for GBER measures. Since 2014, it has increased from around 12 million EUR to more than 17.5 million EUR in 2018. Median annual budgets of GBER measures have increased even more significantly, from around 6 million EUR in 2014 to almost 12 million EUR in 2018 growing by around 100% in 4 years.

Cooperation with Member States

The SAM Working Group met three times in 2019, with France chairing until June 2019 and then co-chaired by Hungary and Denmark. The SAM Working Group addressed several policy and compliance topics related to SAM implementation, such as specific aspects related to aid to innovation clusters and important projects of common European interest. The SAM Working Group reported to the High Level Forum (held in June 2019) the main topics discussed during the past year and on the follow-up to recommendations made by past chairs (Finland, Sweden and the United Kingdom). The High Level Forum also endorsed the work plan submitted by the co-chairs for the period 2019-2020.

In 2019, the Commission continued its bilateral cooperation with the Member States. Launched in 2015, the overall objective of this process is to achieve both good State aid policy and effective State aid control at the national level. Tailored to each Member State's specific needs, bilateral cooperation generally deals with horizontal cross-cutting State aid issues, such as country-specific compliance and implementation issues, governance issues and issues concerning State-owned enterprises, as well as cases in problematic sectors. Each Member State also has a dedicated State Aid Country Coordinator at the Commission, who acts as a first entry point for this Member State's horizontal State aid questions. The Commission conducts periodic country visits to the Member States in order to assess specific bilateral cooperation issues.

Transparency Award Module

The transparency provisions currently part of SAM are in force since 1 July 2016 and require Member States to publish information about the beneficiaries of aid awards above EUR 500 000. Member States have six months starting from the date of granting to provide the required aid awards' data, with the exception of awards in the form of fiscal aid for which the information needs to be provided within one year from the date of granting. The Commission facilitated compliance with this requirement by developing, in cooperation with Member States, the Transparency Award Module (TAM) – an informatics tool for submission and publication of data required under the transparency provisions.

The TAM ensures that information submitted by granting authorities is consistent and comparable across Member States. In addition, the associated transparency public search page provides all stakeholders, i.e. citizens, competitors and researchers, with a single entry point allowing them to make comparable extractions and analysis. For these reasons, the Commission pursues efforts to improve the user friendliness and the interoperability capabilities of the tools, to incentivise those Member States already having National State Aid Registries in place to use the TAM as well. At the end of 2019, 25 Member States have joined the TAM and more than 73 000 aid grants to more than 33 000 individual beneficiaries have been published by 25 Member States and Iceland.

The Commission services support the implementation of the TAM by organizing annually and facilitating, together with Member States' representatives, the Transparency Steering Group and by organising dedicated training courses upon request. The last Transparency Steering Group was held on 11 October 2019 in Brussels and focused on the use of TAM data to support State aid monitoring and control.

In addition, the Commission conducts annual compliance checks to verify the completeness and accuracy of the information published by Member States under the transparency requirements through either the TAM or National State Aid Registries. After a first round carried out in 2018, in 2019 the Commission launched a second exercise that enlarged the scope of the analysis by including State aid awards from 2016 to 2017. The second round of compliance checks launched at the end of May 2019 is expected to be completed during the first half of 2020.

Evaluation of aid schemes

Evaluation of aid schemes is another requirement introduced by SAM. The aim is to gather the necessary evidence to better identify impacts, both positive and negative, of the aid and to provide input for future policy-making by the Member States and the Commission.

Since 1 July 2014, evaluation is required for large GBER schemes in certain aid categories as well as for a selection of notified schemes under the new generation of State aid guidelines.

By the end of 2019, the Commission had approved evaluation plans covering 45 State aid schemes. Three additional schemes are currently under analysis, covering a total of 15 Member States. Most of these decisions concerned either large regional aid projects or Research, Development and Innovation (RDI) aid schemes under the GBER or notified energy and broadband schemes. These schemes account, in total, for over EUR 54 billion of annual State aid budget. By the end of 2019, the Member States had delivered to the Commission 16 interim and four final evaluation reports, which were assessed by the Commission services and considered to be of average to good quality.

In 2019, the Commission also outsourced a fact-finding study to assess the implementation of the evaluation requirement as foreseen by the GBER and relevant guidelines.

The Commission has continued to accompany the implementation of the evaluation requirement by publishing policy briefs and by organising dedicated workshops with Member States' representatives and evaluation experts. The current priority of the Commission concerns the comprehensive assessment of evaluation reports, both intermediate and final, to: i) give appropriate feedback to Member States, ii) make sure that results are effectively used for better policy-making, and iii) provide relevant evidence to accompany the reflections for future legal developments.

Aid for research, development and innovation

While one of the headline targets of the Europe 2020 Strategy is for Research, Development and Innovation (RDI) investments in the EU to reach 3% of EU GDP, RDI spending in the EU has been lagging behind major global competitors, mainly due to lower levels of private investment. To achieve the greatest possible impact with the available budgets RDI aid measures should not replace or crowd out private financing. On the contrary, efforts should be directed at encouraging more private investments. RDI aid can help where market forces alone do not deliver necessary investments in promising but high-risk innovative projects. Therefore, the State aid rules for RDI help ensure that public funding goes to projects that otherwise would not be realised due to market failures. In particular, this includes projects that truly go beyond the state of the art, and which bring innovative products and services to the market and ultimately to consumers. These State aid rules provide for flexible and simple criteria for assessing the compatibility of State aid. Therefore, they facilitate the implementation of support for RDI projects by Member States.

The very purpose of RDI aid is that it should bring added value where markets and companies do not deliver the investments for promising but highly risky innovative projects. Therefore, the State aid rules for RDI help ensure that public funding goes to research projects that would not otherwise be realised due to market failures, that is to say projects that truly go beyond the state of the art and which bring innovative products and services to the market and ultimately to consumers. The RDI Framework, using flexible and simple criteria for assessing the compatibility of State aid, facilitate the implementation of support for RDI projects by Member States.

In 2019, the Commission continued to ensure that aid schemes and individual measures notified or pre-notified under the RDI Framework were well targeted to projects enabling ground-breaking research and innovation activities. Its State aid control activities covered a variety of sectors including the aeronautic, virtual research and technology infrastructures, as well as innovation clusters.

In a significant number of cases the Commission cooperated with Member States with a view to enabling them to adjust certain envisaged RDI measures and bring them in line with the GBER. This way, aid measures could be granted swiftly without having to be notified to the Commission, thereby speeding up public support for RDI. It is noteworthy that following the State Aid Modernisation in 2014, 96% of all RDI measures (84% in value terms) in the Union are implemented under the GBER.

The Commission also proposed in 2019 the RDI related amendments to its General Block Exemption Regulation to facilitate and simplify the way in which the centrally managed funding from Horizon Europe can be combined or, in cases of projects having received a Seal of Excellence, substituted by national funding. The proposed amendments align certain aspects of State aid rules on the one hand and Horizon Europe rules on the other. This should allow to prevent potential discrepancies causing delays or difficulties in the roll-out of RDI funding under the next Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF). More concretely, the GBER proposal provides for exemptions from the notification obligation and from the requirement to carry out at national level an assessment of the quality of a RDI project already assessed as excellent under Horizon rules in the following areas:

·Aid for SMEs for research and development projects as well as for Marie Skłodowska-Curie actions awarded a Seal of Excellence quality label under Horizon 2020 or Horizon Europe (Article 25a);

·Aid provided to co-funded projects, which have been independently evaluated and selected following transnational calls under Horizon Europe (Article 25b);

·Aid provided to Teaming actions, which have been independently evaluated and selected following transnational calls under Horizon Europe. This includes the possibility to provide State aid for project-related infrastructure investments under such Teaming actions (Article 25b).

Finally, in the area of State aid rules for RDI, the Commission contracted a study to provide an independent evidence-based evaluation on the implementation of the State aid rules for RDI in force since 2014, as well as of their effects on RDI investments and competition within the internal market. The objective of the study is to assess whether the current State aid rules in the area of RDI are fit for purpose taking into account the general State Aid Modernisation objectives, the specific objectives of the legal framework and the current and future challenges (also considering the EU research and innovation policy). This study is expected to be finalised in the first trimester of 2020 and its results will be publicly available.

Aid enabling Member States jointly to support important projects of common European interest

In June 2014, the Commission adopted a Communication on Important Projects of Common European Interest (IPCEI). The Communication establishes the conditions under which Member States can support projects making a clear contribution to economic growth, jobs and the competitiveness of the EU. The IPCEI Communication complements other State aid rules such as the General Block Exemption Regulation and the RDI Framework, and allows support of large and integrated transnational innovative projects while ensuring that potential competition distortions are limited. The rules therefore promote ground-breaking research and innovation and sharing of the results widely, whilst ensuring that the support by taxpayer money truly serves EU citizens.

In December 2019, the Commission found that an integrated project jointly notified by seven Member States (Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Poland and Sweden) for research and innovation covering the whole strategic value chain (from materials to recycling and re-use) of batteries for e-mobility and energy storage, is in line with EU State aid rules and contributes to a common EU interest. The seven Member States will provide in the coming years up to approximately EUR 3.2 billion in funding for this project, which is expected to unlock an additional EUR 5 billion in private investments. The Commission has identified batteries as one of the key enabling technologies and strategic value chains deemed to be crucial for future industrial development. This second case of an IPCEI in the area of RDI demonstrates that the instrument can deliver intra-EU RDI cooperation and coordination for key enabling technologies and strategic value chains, including investment into first industrial deployment.

During the second half of 2019, in line with the Commission's battery alliance initiative, discussions with a group of Member States and companies for a possible second IPCEI in the area of batteries for e-mobility and energy storage have intensified. This is in line with the Commission's policy for a shift from the use of environmentally harmful fossil fuels to alternative fuel technologies.

In addition, during 2019, in line with the recommendations of the strategic forum for IPCEI, discussions with a group of Member States and companies for a possible IPCEI in the area of hydrogen technologies and systems and in the area of low carbon industry were initiated. This is in line with the environmental and climate targets of the EU and the Commission’s Green Deal.

Regional aid

Regional aid is an important instrument in the EU toolbox to promote economic and social cohesion. The 2014-2020 regional aid framework is in place since July 2014.

In 2019, the Commission continued advising Member States’ authorities on how to interpret and implement the regional aid provisions of the GBER, thus helping them to make a success of the reforms introduced under SAM to the benefit of both consumers and businesses.

In 2019, the Commission outsourced a study aiming to provide an evidence-based assessment of the implementation of the regional aid framework applicable since 2014, which will constitute the basis for the retrospective evaluation of the current regional aid rules. In parallel, from June to July 2019, the Commission ran a targeted public consultation to gather stakeholder opinions on the application of the regional aid framework 2014-2020 with a view to assessing whether the rules are still fit for purpose.

The Commission adopted several decisions on notified regional investment aid measures under the Regional Aid Guidelines. It authorised regional investment aid for two large investment projects, namely aid to LG Chem (for electric vehicles batteries production in Poland) and aid to Navigator Tissue Cacia (for production of sanitary goods in Portugal). It approved three evaluation plans for large block-exempted regional aid schemes in Hungary, Italy and Poland, the extension of a French scheme providing support for productive investments in outermost regions, and the revision of the regional aid map for France.

Finally, the Commission initiated formal investigation procedures in relation to three large investment projects. The first project is Samsung SDI’s expansion of its existing electric vehicles battery production facility in Hungary, for which the Hungarian authorities intend to grant aid. The second project is Peugeot’s investment in its existing car plant in Spain, for which the Spanish authorities plan to provide public support. The third project is PCC’s investment in Poland into a new plant to produce ultra-pure monochloroacetic acid that already benefitted from two different support measures. Poland considered both support measures to be covered by the 2008 General Block Exemption applicable at the time and therefore did not notify the measures to the Commission. However, after receiving a complaint from a competitor, the Commission decided to open an in-depth investigation to assess whether the respective measures are in line with applicable State aid rules.

Infrastructure

On 28 February 2019, the Commission opened an in-depth investigation to assess whether Danish and Swedish public support for the Øresund

fixed rail-road link is in line with EU State aid rules. Moreover, in June 2019, the Commission opened an in-depth investigation to determine whether the public financing model of the Fehmarn Belt

fixed rail-road link, between Denmark and Germany, is in line with EU State aid rules. Both in-depth investigations follow the General Court's annulment of previous Commission decisions approving the respective support.

1.9.State Aid Modernisation continues

Further extension of the scope of the GBER

The

General Block Exemption Regulation (GBER)