Table of contents

1.Introduction: political and legal context9

2.Problem definition13

2.1.What is the problem?13

2.2.What are the problem drivers?20

2.3.How would the problem evolve23

3.Why should the EU act?23

3.1.Legal basis23

3.2.Subsidiarity: Necessity of EU action24

3.3.Subsidiarity: Added value of EU action25

4.Objectives: What is to be achieved?26

4.1.General objectives26

4.2.Specific objectives26

5.What are the available policy options?28

5.1.What is the baseline from which options are assessed?28

5.2.Description of the policy options32

5.3.Options discarded at an early stage39

6.What are the impacts of the policy options?40

6.1.Social impacts40

6.1.1.Impacts on health40

6.1.2.Impacts on health inequalities44

6.2.Economic impacts45

6.2.1.Impacts on direct costs for businesses and public authorities45

6.2.2.Impacts on consumers47

6.2.3.Internal Market impacts49

6.2.4.Competitiveness and trade impacts50

6.2.5.Impacts on SMEs51

6.3.Environmental impacts53

6.4.Impacts of combined options55

7.How do the options compare?55

7.1.General objective 1: Ensuring a high level of health protection for EU and Specific objective 1: Reduce intake of industrial trans fats in the entire EU for all population groups56

7.1.1.Direct health impacts56

7.1.2.Direct and indirect economic impacts of changes in health status56

7.2.General objective 2: Contribute to the effective functioning of the Internal Market for foods that could contain industrial trans fats and Specific objective 2: Ensure that the same rules/conditions apply in the EU to the manufacturing and placing on the market of foods that could contain industrial trans fats, so as to ensure legal certainty of EU food business operators within and outside the EU58

7.3.General objective 3: Contribution to reducing health inequalities, one of the objectives of Europe 202060

7.4.Effectiveness60

7.5.Efficiency (balance of costs and benefits)62

7.6.Coherence with other EU policy objectives65

7.7.Proportionality65

7.8.Specific tests: SME test66

8.Preferred option68

9.How will actual impacts be monitored and evaluated?71

ANNEX 1: Procedural information72

1.Lead dg, decide planning72

2.Organisation and timing73

3.Consultation of the RSB74

4.Evidence, sources and quality77

ANNEX 2: Stakeholder consultation78

1.Introduction78

2.Stakeholder groups covered by the consultation activities78

3.Consultation activities already carried out before the launch of the IA79

4.Outline of the Consultation strategy for the IA on an initiative to limit industrial trans fats intakes in the EU80

5.Results of the Consultation activities for the IA on an initiative to limit industrial trans fats intakes in the EU81

6.Conclusion87

ANNEX 3: Who is affected and how?89

1.Practical implications of the initiative89

2.Summary of costs and benefits91

ANNEX 4: Analytical methods93

1.Study methodology development93

2.Data collection and review93

3.Screening of impacts and assessment of significance98

4.Analysis of impacts98

5.Validation consultation103

6.Strengths and limitations of the method105

7.Discussion of information gaps and uncertainties106

ANNEX 5: Trans fats – a general presentation108

ANNEX 6: Trans fats consumption and its negative impact on health and intake recommendations111

ANNEX 7: Health effects of ruminant versus industrial trans fats and the potential to limit the associated health problem by addressing their intake116

ANNEX 8: Current status of EU and national measures addressing the trans fats problem and consumer knowledge regarding trans fats118

ANNEX 9: Additional information on trans fats intakes in the population and presence in foods123

ANNEX 10: Discussion of the baseline scenario139

ANNEX 11: Intervention logic for the different options143

ANNEX 12: Impacts screening152

ANNEX 13: Assumptions for the health impacts assessment162

ANNEX 14: Additional information on the Sensitivity Analysis168

1.Impact on health care costs (direct and indirect)168

2.Impact on disability-adjusted life years168

ANNEX 15: Impacts on health inequalities and details on appraisal of general objective 3: contribution to reducing health inequalities, one of the objectives of Europe 2020169

ANNEX 16: Impacts on administrative costs for businesses, understanding the requirements and verify compliance175

ANNEX 17: Impacts on compliance costs for businesses179

1.Compliance costs – product testing179

2.Costs of reformulating products181

3.Costs of ingredients187

4.Costs of labelling189

ANNEX 18: Administrative cost for public authorities192

1.Costs of establishing the policy192

2.Costs of consumer information campaigns193

3.Costs of monitoring and enforcement194

ANNEX 19: Assumptions for the impact assessment on consumer prices197

ANNEX 20: Evidence collected by the external contractor concerning the assumptions for the impact assessment on product attributes200

ANNEX 21: Expected impact of each option on the Internal Market201

ANNEX 22: Details on the expected impact of each option on competitiveness and international trade205

ANNEX 23: Evidence on the impacts on SMEs and expected impact of each option on SMEs206

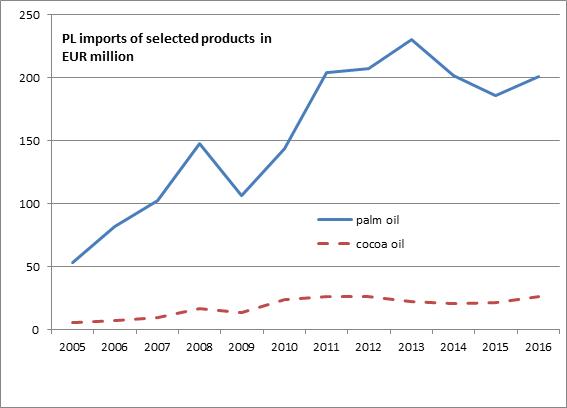

ANNEX 24: Evidence on substitutes for partly hydrogenated oils, environmental impacts of palm oil as well as environmental impacts of alternatives; expected impact of each option on the environment207

ANNEX 25: Impacts of combined options212

1.Combining mandatory labelling with legislation (2 + 1b or 2 + 3b)212

2.Combining mandatory labelling with voluntary agreement (2 + 1a or 2 + 3a)213

ANNEX 26: Further details for appraisal of General objective 1 specific objective 1215

1.Additional details for section 7.1.1 on direct health impacts215

2.Additional details for section 7.1.2 direct and indirect economic impacts of changes in health status216

3.Further details for appraisal of specific objective 1: Reduce intake of industrial trans fats in the entire EU for all population groups216

ANNEX 27: Further details for appraisal of specific objective 2: Ensure that the same rules/conditions apply in the EU to the manufacturing and placing on the market of foods that could contain industrial trans fats, so as to ensure legal certainty of EU food business operators within and outside the EU219

ANNEX 28: Ex ante analyses in the US and Canada on Evidence on legislation to ban partly hydrogenated oils221

ANNEX 29: Consolidated information collected through interviews with EU level business associations by223

ANNEX 30: Aggregated evidence for each type of impact: a list of indicators; the description of the evidence obtained, either quantitative or qualitative; and sources for that evidence304

ANNEX 31: Validation consultation by ICF, survey instrument439

ANNEX 32: ICF Country profiles461

ANNEX 33: Questionnaire for the Open Public Consultation466

List of abbreviations

CAOBISCO

Association of Chocolate, Biscuit and Confectionery Industries of

the European Union

CI

Confidence Interval

EFSA

European Food Safety Authority

FEDIOL

EU vegetable oil and protein meal industry association

HOTREC

Association of hotels, restaurants and cafés in Europe

IA

Impact Assessment

IIA

Inception IA

IMACE

European Margarine Association

ISG

Inter-services Steering Group

JRC

the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission

NGO

Non-governmental Organisation

OPC

(On-line) Open Public Consultation (carried out for this IA)

RR

Relative Risk

RSPO

Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil

SKU

Stock Keeping Unit

SMEs

Micro, Small and Medium-sized Enterprises

SWD

Commission Staff Working Document

TFEU

Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

WHO

World Health Organisation

Glossary

|

Term or acronym

|

Meaning or definition

|

|

Cardio vascular disease

|

a class of diseases affecting the heart or blood vessels. It includes coronary artery disease as well as stroke, heart failure, arrhythmia, aortic aneurysms, among others

|

|

Coronary artery disease

|

a group of diseases that includes: stable angina, unstable angina, myocardial infarction, and sudden cardiac death. It is within the group of cardio vascular diseases of which it is the most common type

|

|

Coronary heart disease

|

a health condition that reduces blood flow through the coronary arteries to the heart and typically results in chest pain or heart damage. It is the outcome of coronary artery disease

|

|

Deforestation

|

the action or process of clearing of forests

|

|

Disability adjusted life years

|

one disability adjusted life year can be thought of as one lost year of "healthy" life. The sum of disability adjusted life years across the population, or the burden of disease, can be thought of as a measurement of the gap between current health status and an ideal health situation where the entire population lives to an advanced age, free of disease and disability. Disability-adjusted life years measure overall disease burden. It expresses that burden as the number of years lost due to ill health, disability or early death

|

|

Food business operator

|

the natural or legal person responsible for ensuring that the requirements of food law are met within the food business under their control

|

|

Isocaloric

|

having similar caloric values

|

|

Labour cost

|

the total expenditure borne by employers in order to employ workers, including social security contributions and other non-wage labour costs

|

|

Markov model

|

a state-transition model used to model randomly changing systems where it is assumed that future states depend only on the current state not on the events that occurred before it

|

|

Mortality rate

|

a measure of the number of deaths in a given population per unit of time

|

|

Non-prepacked food

|

foods sold without packaging

|

|

Partially hydrogenated oil:

|

a liquid oil which has only been processed through partial hydrogenation and is semi-solid

|

|

Pre-packed food

|

any food that is put into packaging before being put on sale and that cannot be altered without opening or changing the packaging (as defined article 2 (2) (e) of Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011)

|

|

Trans fats

|

also called Trans fatty acids and sometimes abbreviated as TFAs, are a particular type of unsaturated fatty acids that are present in foods .'Trans' describes the specific and rather unusual configuration of the unsaturated bond in a fatty acid, while generally fats in foods contain unsaturated fatty acids in 'cis' configuration

Annex I point 4 of Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 on the provision of food information to consumers defines: ' " trans fat" means fatty acids with at least one non-conjugated (namely interrupted by at least one methylene group) carbon-carbon double bond in the trans configuration'

There are two sources of trans fats: those produced industrially (so called industrial trans fats) and those naturally produced by ruminant animals (ruminant trans fats), which are present in derived food products, such as dairy products or meat from cattle, sheep or goats

|

1.1.

1.Introduction: political and legal context

Trans fats (also called 'trans fatty acids' and sometimes abbreviated as TFAs) are a particular type of unsaturated fatty acids that are present in some foods as natural trans fats in ruminant (dairy and meat) products or as industrially manufactured trans fats. Industrial trans fats, in the form of partial hydrogenated oils, are added to improve stability or texture or for other technological reasons, in a variety of products including pastries and chocolates. One of the common substitution fats with similar technological and cost advantages is palm oil. Trans fats are not synthesised by the human body and are not required in the human diet.

There is scientific consensus that trans fats intake has a negative effect on human health: more specifically, consumption of trans fats has a negative impact on blood cholesterol levels and increases the risk of coronary heart disease more than any other macronutrient compared on a per-calorie basis; the risk of dying from heart disease is 20-32 % higher when consuming 2 % of the daily energy intake from trans fats instead of consuming the same energy amount from carbohydrates, saturated fatty acids, cis monounsaturated fatty acids and cis polyunsaturated fatty acids.

The European Food Safety Authority recommends that trans fats intakes should be 'as low as is possible within the context of a nutritionally adequate diet'. The World Health Organisation recommends that less than 1 % of dietary energy intake should come from consuming trans fats (which equates to maximum 2,2 g of trans fats per day for a person requiring 2000 kilocalories). Currently, in total 7 Member States have introduced legislation regarding intakes of industrial trans fats. In particular, 6 Member States (Denmark, Austria, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania and Slovenia) have set legal limits and one (Romania) has recently notified a draft legal measure. The legal limit of maximum 2 % of industrially produced trans fats in foods introduced in several Member States is in line both with the intake recommendations of the European Food Safety Authority and of WHO: typical intakes of total fat in European countries are reported to be at a maximum of 48 % of the daily energy intake (95th percentile). Provided that all foods contain trans fats at 2 % in a very unlikely, extreme scenario, intake levels would be at 0.96 % of energy intake, below the WHO recommendation. Assuming a 2000 kilocalorie diet, 0.96 % of daily energy intake equates to a maximum of 2.1 g of industrial trans fats intake per day. Empirical evidence from Denmark, where a 2 % legal limit per 100 g fat content applies, suggests that (in 2014) the average industrial trans fats intake was 0.009 % of energy intake.

This very low level could be considered to be in line with the recommendation of the European Food Safety Authority ('as low as possible'). In this context it is noteworthy that some small amounts of trans fats are generated during the normal processing and production of foods. Ruminant trans fats sources typically contribute between 0.3 and 0.8 % of the daily energy intake depending on dietary habits across Europe. Thus, even the combination of ruminant and industrial trans fats typically amount to 0.309 to 0.809 % of daily energy intake.

The issue of trans fats was intensively debated during the negotiations that preceded the adoption of Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 on food information to consumers. This Regulation does not include trans fats in the list of mandatory nutrition declaration since the co-legislator was not convinced that the introduction of trans fats amounts on food labels would consistently enable consumers to identify the healthier choice. In addition, the efficiency of such measure was questioned since it would not apply to non-pre-packed foods, all of which may contain high levels of industrial trans fats. Finally, trans fats labelling would not distinguish between ruminant and industrial trans fats. Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 also prohibits operators from declaring the trans fats content of foods on nutrition labels on a voluntary basis. It was considered that this possibility would be used as a marketing tool by some operators only and could lead to consumers' confusion. Therefore, the co-legislator agreed that instead of looking only into the labelling aspect, the Commission should assess the impacts of all means to enable consumers to make healthier choices, including restrictions on the use of trans fats. A report was requested by Article 30(7) of Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and the Council on the provision of food information to consumers.

In its 2015 report, the Commission noted that average trans fats intake in the EU is below nationally and internationally recommended levels, however, this conclusion is not valid for all population groups. Food products with high industrial trans fats content remain available on the EU market, thus, reducing industrial trans fats intakes entails public health gains. The report concluded that a legal limit for industrial trans fats would be the most effective measure in terms of public health, consumer protection and compatibility with the Internal Market but that further investigation is required.

Numerous calls for a reduction of trans fats intakes in the EU have emerged from the agenda of the European Parliament and the Council, individual Member States, and stakeholders. Member States' concerns on industrial trans fats had been voiced in the context of the High Level Group on nutrition and physical activity where 22 Member States indicated industrial trans fats as one of the priorities with respect to reformulation or nutrient policy. Health EU Ministers exchanged views on trans fats at two informal Council meetings: in April 2015 in Riga, a large majority of intervening delegations expressed support to the necessity of reducing industrial trans fats levels in food products. In September 2015 in Luxembourg, Member States discussed possible solutions to reduce industrial trans fats levels in foods. Some delegations called for legal limits to industrial trans fats presence in foods at EU level, while others favoured self-regulatory approaches based on product reformulation.

Council Conclusions of 2014 and of 2016 noted with concern

'the high intake of …trans fatty acids…' and

'The prevalence of overweight, obesity and other diet-related non-communicable diseases in the European population is too high and is still rising. This has a negative impact on life expectancy, reducing Union citizens' quality of life and affecting society, for example by threatening the availability of a healthy and sustainable workforce and inducing high healthcare costs which may affect the sustainability of the healthcare systems. It thus also imposes an economic burden on the Union and its Member States. (…) Nutrition plays an important role in this context, alongside other lifestyle-related matters: (…). In some Member States, people are still exposed to high amounts of trans fatty acids'.

The European Parliament adopted on 26 October 2016 a resolution calling on the Commission to propose legislation setting a limit on industrial trans fats within two years and to carry out an impact assessment evaluating impacts on operators and consumers.

Following the adoption of the Commission report, a considerable number of external stakeholders, such as associations representing producers and consumer representatives have expressed a keen interest in this issue. All stakeholders that intervened in the debate on trans fats so far have welcomed the Commission's report and/or supported an EU initiative to set legal limits to industrial trans fats in foods, both on the consumers' side and on the industry's side.

In this context, of particular note is the joint letter21 addressed on 15 October 2015 to the European Commission by four major food manufacturers, together with leading consumers' and health NGOs and the Standing Committee of European Doctors. Also of note are the number of reformulation commitments to lower the content of industrial trans fats in foods made in the past years by food manufacturers in the EU Platform for Diet, Physical Activity and Health. The positions of industry stakeholders (also well summarised in a statement by Food Drink Europe of 19 November 2015) indicate that the industrial trans fats content of foods can effectively be lowered without disproportionate cost, that an EU initiative would benefit consumers and the industry by setting a level playing field in the Internal Market, and that particular support might be needed for SMEs.

Stakeholders also broadly supported national initiatives that set limits to the presence of industrial trans fats in foods.

At the global level, calls for reduction of trans fats intakes led to the REPLACE initiative ('trans fat free by 2023') of WHO in May 2018.

WHO recommends to ‘legislate or enact regulatory actions to eliminate industrially-produced trans fats’.

The objective of this impact assessment is to enable an informed decision on how to deal with trans fats, taking into account the potential economic, social and environmental impacts of different policy options, including implementing the option of a legal limit for industrial trans fats. In this context, the factual situation, as regards the issue of excessive trans fats intakes in the EU and its underlying causes and the policy implications of available alternative approaches to setting a legal limit, i.e. mandatory labelling of trans fats and voluntary approaches to food reformulation, are examined. Besides the public health dimension and ensuring a sound basis for consumer choice, the impact assessment also examines the consequences of the policy options available for the businesses, including SMEs and the Single Market.

In addition to the report adopted by the Commission in 2015 on trans fats, the impact assessment takes into account various studies on trans fats at the European level and internationally, investigating the impacts of trans fats and the potential effects of alternative policy options to limit their use. These build on analyses by the Joint Research Centre of the Commission (JRC), scientific opinions of the European Food Safety Authority5, international reports by the World Health Organization6 and academic studies. In 2017, the European Commission commissioned an external study by the contractor ICF to support this IA.

2.Problem definition

2.1.What is the problem?

Trans fats are an important risk factor for the development of coronary heart disease5 37, the single leading cause of mortality in the EU. Cardio vascular disease comprises a range of diseases that affect the heart, including heart failure (which can be caused by coronary heart disease, among other factors), arrhythmia (abnormal heart beat) and heart valve problems, and imposes substantial health burdens in the EU. It is estimated that 49 million people live with cardio vascular disease and that the condition imposes costs of more than €200 billion each year in the EU.

The European Food Safety Authority and the World Health Organization recommend that their consumption is limited or minimised.5 6 Industrial trans fats intakes are particularly high among consumers with lower income, who are also the most at risk of coronary heart disease and intakes continue to contribute to the absolute health and economic disease burdens of cardio vascular disease.

The precise contribution of trans fats intake to health risks and associated economic problems are difficult to assess for the entire EU due to limited data available for trans fats intakes in the entire EU. There is empirical evidence that the introduction of a legal limit for industrial trans fats reduced deaths caused by cardiovascular disease.

Over 3 years following the introduction of the legal limit, mortality attributable to cardiovascular disease decreased on average by about 14.2 deaths per 100,000 people per year relative to a synthetic control group, meaning that the Danish limit on industrial trans fats saves around 700 people a year in Denmark.

Further evidence of the effectiveness of legal measures is available from outside the EU: in Argentina, near elimination of industrially produced trans fats from food is estimated to be associated with an annual 1,3 to 6,3 % reduction in coronary heart disease events. In New York, people living in counties in New York State with restrictions on industrial trans fats in food had a 7,8 % greater decrease in hospital admissions for heart attacks between 2007 and 2013 than people in counties without restrictions.

How widespread are trans fats in the EU?

There is limited availability of comparable/EU-level data on the intakes of trans fats in the different population groups or on the presence of trans fats in foods in the different Member States. Evidence from a number of countries indicates that the intake of trans fats in the EU has decreased considerably over recent years but that the situation is not homogeneous for all products consumed by all population groups in all EU Member States. Studies summarised by the JRC in its 2014 report concluded that:

·Average daily trans fats intakes for the overall EU population are below 1 % of daily energy intake. Yet some population groups have (or are at risk of having) higher intakes.

Examples of such sub-populations are low-income citizens (British male and female participants of the Low Income Diet and Nutrition Survey where all age groups had intake levels above 1 % of energy intake, ranging from 1.2 to 1.4 % of energy intake) or male or female university students aged 18 to 30 years (data from Croatia, intake levels ranging from 1.1 to 1.2 % of energy intake). Also, according to surveys collected by the JRC, Swedish boys aged 8 and 11 years exceeded the WHO recommendation (1 % of energy intake), as well as Spanish males and females aged 18 to 30 years (1.05 % of energy intake) and French females over 55 years of age (1 % of energy intake) and between 3 to 10 years (1.02 % of energy intake). As calculated by the JRC, up to 25 % of surveyed individuals aged 20-30 years have trans fats intakes above 1 % of daily energy intake. Annex 9 provides more details. Latest information collected during the OPC confirm this assessment.

·Most of the analysed food products contain trans fats at amounts below 2 % of the total fat content of the food and 77 % of these contain trans fats at amounts below 0.5 % of the total fat content of the food. However, there are still products in the European food market with high levels of industrial trans fats (e.g. biscuits or popcorn with industrial trans fats values in the order of 40-50 % of the total fat content of the food). While most of the analysed products are pre-packed products, there are also several reported cases of non pre-packed foods with trans fats levels above 2% of the total fat content in food. Examples of products found to contain trans fats in considerable amounts in Member States, generally of industrial origin, are frying fat also for industrial use, stick margarines, margarine used to produce pastry products, bakery products, biscuits, wafers, confectionary products including those with cocoa coatings such as covered puffed rice, soups and sauces. Further recent studies about trans fats content in food in the EU were published after the finalisation of the JRC36 work:

oA study focused on the market for pastries, confectionery, and potato products in Poland in the period 2009-2010 and reported a great diversity of trans fats content (0.1 % to 24.8 % of total fat content). Wafers were characterized by the highest average content of trans fats in the group of pastries (1.94 % of total fat content);

oA research in Germany in 2017 quoting data from the Federal Office for Consumer Protection and Food Safety noted that in the period 2014 to 2017 the mean trans fats content in certain sampled fried bakery products was higher than 10 % of total fat content, sometimes even more than 30 %;

oTests carried out by the Czech consumer association found that more than half of the tested margarines, 60% of wafers and 20 % of chocolate waffles tested were above the 2 % limit.

·Quantitative comprehensive data of industrial trans fats use for particular food sectors, or particular regions or sorted by company size in the EU is not available. However, available data has shown significant presence of trans fats in different food categories, such as convenience products, cereal products, confectionary, crisps, savoury, biscuits, fast food products, fats and oils, without however a distinction between prepacked and non-prepacked, locally produced produce or not. Given that larger companies were more likely to participate in reformulation campaigns than SMEs, the residual share of products still high in trans fats is considered to be higher among SMEs.

Consultation with Member States confirmed the findings in the JRC report. In some Member States high intake levels prompted activities to reduce intake levels of trans fats, contributing to enhanced reformulation activities and reduced levels.

A study noted that, in different Member States, industrial trans fats levels in some foods were still above 2 % of their total fat content and that, in some EU countries, industrial trans fats levels in pre-packed biscuits, cakes and wafers have not dropped meaningfully since the mid-2000s. The authors of this study continued analysing the evolution of the market in six countries in South East Europe covered by the previous study (including two EU Member States) and noted that availability of popular foods with high amounts of industrial trans fats increased from a high level in 2012 to an even higher level in 2014. Another study specifically focused on the Portuguese market showed that, in 2013, total trans fats content in different foods ranged from 0.06 % to 30.2 % of the total fat content of the food (average 1.9 %), with the highest average values in the 'biscuits, wafers and cookies' group (3.4 % of the total fat content of the food). 50 samples out of 268 (19 %) contained trans fats at amounts higher than 2 % of the total fat content of the food. Replies during the OPC revealed that 78 % and 77 %, respectively, of respondents agreed with the problem description above with regard to intake levels and content in foods, while 9 % and 8 disagreed, all but one disagreeing respondent stated that intake level and contents in food were actually higher that described above. An unpublished study in Hungary confirmed a steadily increasing trend of trans fats content in foods from 2009/2010 until 2012, which was reverted only in 2013 when the decision ona national legal limit of trans fats was notified to the Commission (further details are provided in section 5.1).

Sources of trans fats

Ruminant trans fats in dairy products or meat from cattle, sheep or goat

are present in relatively constant, low proportions of the fat part of those foods, at levels most commonly around 3 % (ranging from 2 to 9 %) of the total fat content.

The primary dietary source of industrial trans fats is partly hydrogenated oils which contain various amounts of trans fats (up to more than 50 % of the total fat content). The partial hydrogenation process turns oils into semi-solid and solid fats. Industrial trans fats in the form of partly hydrogenated oils have been used or introduced into manufacturing processes of foods in order to achieve at comparative low prices a particular technological function, such as a solid fat texture at room temperature (e.g. in vegetable fat cocoa coatings). Other than partly hydrogenated oils, industrial trans fats can also be the result of refining of unsaturated oils or of heating and frying of oils at too high temperatures (> 220°C).

Reduction of intake levels of industrial trans fats is technologically feasible. However, the fat composition of ruminant fats with regard to their trans fats content is not modifiable to a significant degree, therefore their intake cannot totally be avoided when consuming ruminant derived foods that are important in the EU diet of the EU population as they contribute essential nutrients. Also, ruminant trans fats sources generally contribute in a limited way to high total trans fats intake. National public health policies generally address the problem of intake of ruminant trans fat intake already by initiatives to reduce saturated fat intake. Although different actions were taken in several Member States and intakes have decreased over the past years, industrial trans fats are still present at levels of concern in certain foods and intakes are still excessive in certain cases. The evidence collected by ICF also suggests that gains obtained in recent years through voluntary industry initiatives may have reached their limits. The issue is of particular relevance in certain Member States and for particular population groups. This results in the following problems:

·Protection of consumers' health

Different levels of protection of consumers' health currently exist in the EU, depending on the presence of foods with high industrial trans fats content in the Member State's market (presence influenced by the existence or not of national regulatory or not-regulatory initiatives) and on consumers' consumption patterns. Consumption patterns are influenced by socio-economic factors (e.g. consumers with lower income are more likely to consume products with high industrial trans fats content that are generally sold at a lower price

so that this situation contributes to the perpetuation of health inequalities in the EU.

In light of the global trend to reduce intakes of trans fats and the WHO's recent REPLACE initiative ('trans fat free by 2023') recommending to ‘legislate or enact regulatory actions to eliminate industrially-produced trans fats’, a number of countries worldwide have acted and others are expected to act. Therefore, not taking any action at EU level could entail a reputational risk for the EU of not adequately addressing a serious health concern of global dimension.

·Functioning of the Internal Market and international trade

Only some Member States have taken action on industrial trans fats, which is problematic for the effective functioning of the Internal Market: food business operators active in countries where no limit on industrial trans fats exists have no related reformulation costs and are therefore at a competitive advantage vis-à-vis operators active in countries where legal limits exist or operators abide by self-regulatory commitments. The current lack of a consistent approach at EU level means that there is not a level playing field between operators that have reformulated their products in order to reduce or fully remove ingredients containing industrial trans fats, due to self-regulation, voluntary agreements with national governments or legal measures, and those that have not. Generally, manufacturers face higher cost if they produce different varieties of a food with different ingredients to meet diverging national legal limits, rather than benefitting from economies of scale regarding one recipe for a food product. Producers that have not taken any steps to reduce industrial trans fats may save costs as they do not invest in reformulation and through use of lower priced ingredients. This may provide a competitive advantage in the market.

This is particularly relevant for operators active in different Member States. At the same time, operators active in countries where no limit on industrial trans fats exists are negatively affected by the legal uncertainty over whether new initiatives to reduce industrial trans fats intakes will be adopted at national level and might have difficulties in planning R&D investments. The above described situation also hampers international trade: operators from third countries exporting their foods to the EU are subject to different conditions depending on where their foods are marketed. Similar considerations also apply to EU exporters to third countries. In countries without legal measures but with industry complying with voluntary agreements, industry may face unfair competition with producers in third countries. This issue in relation to external trade stems from import of products with high industrial trans fats contents into the EU. Eastern European countries may be at heightened risk for such imports due to their geographical position and the price sensitivity of consumers. Empirical evidence supports this description. Of note, all national legal measures apply to all foods sold in the country, including both foods produced nationally and foods imported from other Member States or from third countries.

Types of stakeholders affected

1.EU consumers are directly exposed to trans in foods and would be affected by any EU initiative on the matter through reductions in their trans fats intakes. Consumers will benefit from reduced risk of contracting coronary artery disease when industrial trans fats intakes are reduced, but they may experience an increase in the price and potentially a change in the quality and attributes of certain food products. Consumers in Member States where foods containing high levels of industrial trans fats are still on the market and consumers with high trans fats intakes are particularly affected.

2.Healthcare providers and healthcare systems are affected by the impact the presence of industrial trans fats has on the incidence of coronary heart disease and associated costs of healthcare.

3.Food businesses, including SMEs, would be impacted by action to limit industrial trans fats in food and additional costs. More specifically:

·Manufacturers of pre-packed foods placed on the market in the EU or exported outside the EU operating chiefly in the following sectors: manufacture of margarine and similar edible fats, bread, fresh pastry goods and cakes, rusk and biscuits, preserved pastry goods and cakes, cocoa, chocolate and sugar confectionery, condiments and seasonings, preserving of potatoes;

·Mass caterers providing non pre-packed foods to consumers (e.g. fries) which (might) contain industrial trans fats, restaurants and businesses offering mobile food service (different sizes of business: multinational, national, SMEs);

·Manufacturers of ingredients placed on the market in the EU or exported outside the EU which contain industrial trans fats or are trans fats-free and can, in the latter case, be used as replacement of industrial trans fats-containing ingredients (e.g. frying oils) (mainly large operators);

·Retailers distributing foods which (might) contain industrial trans fats: they will be indirectly affected (different sizes of business).

·Third-country-based food business operators exporting into the EU would be affected by any EU initiative on the matter.

All food business operators have a role in determining the level of industrial trans fats in their products. Many of the large players have reduced industrial trans fats levels through reformulation. In this context, major producers and associations of the food industry have supported the implementation of a recommendation of a legal limit of industrial trans fats.

Manufacturers of oils and fats have a critical role to play as suppliers of ingredients that may contain industrial trans fats to food manufacturers, particularly to SMEs. A number of manufacturers have already acted on this issue, while others have not (in particular smaller and less organised businesses).

4.Public authorities of EU Member States are directly affected by the problem and by EU action as they will be responsible for implementing, publicising, administering and enforcing the new rules, incurring costs as a result.

5.Populations around the globe are affected, especially given concern about the potential impact on palm oil consumption and its effects on climate change and biodiversity.

2.2.What are the problem drivers?

The drivers of industrial trans fats intake are partly a matter of efficiency of industrial recipe and process and related lower costs, partly one of different national approaches and partly related to consumer behaviour.

Industrial recipe and process

High trans fats intake results from consumption of food products containing high levels of industrial trans fats. Industrial trans fats are used in the manufacturing process and in the recipe of certain foods for technological reasons. Especially, partly hydrogenated oils are solid at room temperature and relative stable, either to rancidity over storage time or when heated repeatedly as frying oils.

In addition, they may be chosen due to their competitive price. Alternative ingredients need to be found when replacing ingredients with high trans fats levels, and sometimes developed, so that the product presents similar characteristics of texture, taste, etc. after reformulation.

Reformulation can entail substitution or development of a new product, and sometimes changes to the manufacturing equipment to accommodate new ingredients. This poses various challenges to industry, and chiefly to smaller businesses, which may be dependent on suppliers to provide alternative ingredients.

In order to overcome cost-related barriers to replace ingredients with a high industrial trans fats content with alternatives, a stimulus to change by the market or regulators, may be needed, such as market pressure, legal obligations or other action by public authorities. The level of corporate social responsibility as well as responsiveness of food business operators vary depending on the Member State.

Different national approaches

National authorities have the power to limit industrial trans fats levels in foods through initiatives at national level if they find it necessary to protect public health. However, evidence shows that national authorities have different approaches to industrial trans fats, with some acting and others not.

Among the Member States that have introduced legislation, a limit of 2 % of industrial trans fats of fat was the preferred choice. However, additionally, 4 Member States have complemented this with different limits established for lower fat products. Due to those differences, all foods that contain between 3 and 20 % of fat with industrial trans fats levels between 2 and 4 % of fat would comply in 4 Member States but not comply in 3 Member States and all foods that contain less than 3 % of fat with industrial trans fats levels between 4 and 10 % of fat would comply in 2 Member States but not in 5 Member States. Those differences are in practice significant, as the majority of food products are below 20 % of fat and many are below 3 % of fat per 100 g of food. Tall existing Member States measures have in common the general 2 % limit for all foods with more than 20 % of fat content, while this food category represents generally a minor share of the total food offer. In Member States where voluntary measures have been taken, reductions were achieved, however, not always in line with legal limits mentioned above.

There is evidence collected by ICF about the effectiveness of both legal as well as voluntary measures in Europe. For example, in Denmark, a legal limit led to virtually eliminating industrial trans fats from the Danish food supply. Data collected in Austria before and after the introduction of the legal measure indicate that from bakery products controlled over time, once before the introduction of the legal measure and twice afterwards, 18 out of 30 samples were not compliant while 3 years after the measure came into force 1 out of 68 samples was not compliant and two years later all samples were compliant. Data collected in Hungary before and after the introduction of the legal limit point to a reduction of industrial trans fats intakes per person foods in the order of 40 % to 75 %.

While it could be assumed that more Member States would take action in the absence of EU intervention, there are no precise indications for all Member States, taking into account that incentives for food business operators to act can vary significantly and national authorities have different approaches to industrial trans fats. If parallel action is not undertaken at national level in all EU Member States, operators would remain subject to different conditions for the manufacturing and placing on the market of foods that could contain industrial trans fats and obstacles to the functioning of the Internal Market would persist. At the same time, products with high industrial trans fats levels would remain on the market in some parts of the EU and intakes of trans fats would remain excessive for certain consumer groups. This would negatively affect the protection of consumers' health and would contribute to the perpetuation of health inequalities in the EU.

Even if action was undertaken at national level in all EU Member States, it is very likely that differences would exist in the timing of the interventions (i.e. not all national actions would be launched at the same time) and in their content (i.e. it is possible that different measures would set different legal limits or cover different products). This explains the clear added value of an EU-based, EU-wide action: the possibility to ensure a level playing field in the Internal Market and the same high level of protection of consumers' health by the means of an initiative that would apply simultaneously in the entire EU and would minimise the risk of national regulatory interventions (further) fragmenting the Internal Market.

Consumer behaviour

Low consumer awareness of the risks associated with the consumption of trans fats may also contribute to industrial trans fats intake. The evidence in the EU points to low levels of consumer information and consumer awareness on trans fats, including which ingredient that is declared on the label or which non prepacked foods may contain trans fats. Many foods are potential sources that are difficult to avoid totally as this would lead to very restricted dietary choices.

Not all consumers can relate the information on the use of partly hydrogenated oils required by Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 to the presence of industrial trans fats in foods and not all consumers can use that information to effectively compare different products taking into account their overall nutritional composition.

Finally, other considerations may influence consumer behaviour (e.g. cost, taste, habits) stronger than the intention to reduce trans fats intake.

2.3.How would the problem evolve

Whether the decline in industrial trans fats levels in food product and industrial trans fats intake observed in the past years will continue at the same speed and achieve a near elimination of industrial trans fats in the EU is not certain. Contrary, there is some evidence of new products that contain high levels of industrial trans fats being introduced to the market in recent years. Consumer health would continue to be at risk in a number of Member States, particularly in the Eastern and Southern part of the EU. The perspectives provided by stakeholders in the consultation conducted by ICF in the context of the study to support this IA suggested that the problem would remain in the absence of EU action but also that many Member States would act unilaterally in the absence of EU action. Based on previous experiences, national legal measures introduced for public health protection, would likely differ to a certain degree in scope and content and could contribute to fragmenting further the Single Market for food products.

3.Why should the EU act?

3.1.Legal basis

EU action could be taken within the framework of Article 114 TFEU, in order to ensure the functioning of the Internal Market, whilst ensuring a high level of protection for health and consumers. The adoption of a legal measure to set limits to trans fats presence in food can be considered through the implementation of existing legislation, more specifically, on the basis of Regulation (EC) No 1925/2006 on the addition of vitamins and minerals and of certain other substances to foods. That Regulation aims at providing a high level of consumer protection whilst ensuring the effective functioning of the internal market. The Regulation empowers the Commission to take measures restricting the addition of certain substances to foods or the use of such substances in the manufacture of foods in view of harmful effects on health which have been identified in relation to a particular substance. For the specific case of the presence of trans fats in food, harmful effects have been identified based on scientific advice provided by EFSA, as explained under point 1.

3.2.Subsidiarity: Necessity of EU action

The existing situation on industrial trans fats negatively affects the protection of consumers' health and contributes to the perpetuation of health inequalities. Excessive intakes of industrial trans fats are associated with avoidable suffering and pose burden on public health care systems.

Industrial trans fats are still present at levels of concern in certain foods in many Member States and particularly in Member States where no national action has been undertaken so far (voluntary or regulatory) to reduce such levels. While average daily trans fats intakes for the overall EU population are below 1 % of daily energy intake, some population groups have (or are at risk of having) higher intakes, including low-income groups and younger population groups (18 to 30 years).36 As calculated by the JRC, up to 25 % of surveyed individuals aged 20-30 years have trans fats intakes above 1 % of daily energy intake.36 But even if population average intake levels are around or slightly below 1 % of daily energy intake, this level can be considered as excessive, taking into account the recommendation from the European Food Safety Authority that intakes should be as low as possible. Empirical evidence supports this view, as reducing intake levels of industrial trans fats from below 1 % or daily energy intake to minimal levels in Denmark, mortality attributable to cardiovascular disease decreased on average by about 14.2 deaths per 100,000 people per year relative to a synthetic control group.

According to the ICF research, levels of industrial trans fats are not necessarily declining in the coming years. While data gathered for the ICF study confirm a trend towards industrial trans fats reduction in food products, it shows also that the limits of the current approach with no action taken at EU level have been reached. Levels of industrial trans fats appear to remain high in certain countries, predominantly Eastern and Southern Europe, and certain sub-groups of food businesses, particularly SMEs. Levels were still above 2 % of their total fat content and in some Eastern and South-Eastern EU countries, industrial trans fats levels in pre-packed biscuits, cakes and wafers have not dropped meaningfully since the mid-2000s. The authors of this study continued analysing the evolution of the market in six countries in South-East Europe covered by the previous study (including two EU Member States) and noted that availability of popular foods with high amounts of industrial trans fats increased from a high level in 2012 to an even higher level in 2014. Another study specifically focused on the Portuguese market showed that, in 2013, total trans fats content in different foods ranged from 0.06 % to 30.2 % of the total fat content of the food (average 1.9 %), with the highest average values in the “biscuits, wafers and cookies” group (3.4 % of the total fat content of the food). 50 samples out of 268 (19 %) contained trans fats at amounts higher than 2 % of the total fat content of the food. Several consultations and triangulation of data have confirmed these findings.

Even under the assumption that a decline in industrial trans fats intake would take place over time without EU level action, evidence suggests that from a society benefit/cost point of view, taking EU level legal action is a highly efficient measure. Therefore, opportunity cost for not acting at EU level are high, and they could be reduced the faster action is taken and measures are implemented, with resulting benefits for human health and cost to society.

3.3.Subsidiarity: Added value of EU action

The existing situation on industrial trans fats hampers the effective functioning of the Internal Market.

Whilst action has been taken by some countries, and others may be expected to act in the absence of an EU initiative, rapid and universal action on industrial trans fats by Member States is currently not envisaged. Products with high industrial trans fats content would therefore remain on the EU market and industrial trans fats would continue to contribute to health impacts and health inequalities.

In addition, legal measures and voluntary initiatives taken by Member States so far differ, as different national views in relation to acceptable levels exist. Additional measures at Member State level could lead to further differences in approach, adding complexity and cost for food business operators.

Furthermore, as a basis for the Internal Market in foods, the EU has a detailed and rather comprehensive system of general and specific food laws, ensuring that products can be freely traded, but also that consumers can be confident that products offered are safe. To address potential health concerns, food safety measures ensure a high level of health protection of consumers. Excessive industrial trans fats in foods pose risks from a food safety angle. In case a food constituent is linked to serious health concerns, confirmed by an opinion by EFSA, their presence should be either prohibited or limited, both for products produced in the EU and for imported products. Recent EFSA opinions in relation to the presence of industrial trans fats in food ingredients recommended that the Commission considers revising the specifications for the ingredients, ‘including maximum limits for trans fatty acids’.

Added value at EU level thus derives from the possibility to ensure a level playing field in the Internal Market and the same high level of protection of consumers' health.. In this context, it is of note that

in the consultation that preceded the adoption of the Commission's report, several Member States proactively signalled their preference for an EU level initiative on industrial trans fats.

4.Objectives: What is to be achieved?

4.1.General objectives

To address the problems that industrial trans fats intake is an important risk factor for the development of coronary heart disease and contributes to the perpetuation of health inequalities within the EU, the identified general objectives of EU action on industrial trans fats to be achieved are:

·To ensure a high level of health protection for EU consumers;

·This will also contribute to reducing health inequalities, one the objectives of Europe 2020;

To address the problem of obstacles to the functioning of the Internal Market (unfair competition, legal uncertainty), the identified general objective is:

·To contribute to the effective functioning of the Internal Market for foods that could contain industrial trans fats.

4.2.Specific objectives

The following specific objectives of EU action on industrial trans fats to be achieved are:

·To reduce intake of industrial trans fats in the entire EU for all population groups;

·To ensure that the same rules/conditions apply in the EU to the manufacturing and placing on the market of foods that could contain industrial trans fats, so as to ensure legal certainty of EU food business operators within and outside the EU

Data collected during the Impact Assessment support the view, that trans fats are particularly a problem in Eastern and South-Eastern Europe, a region that generally also suffers from relatively high rated of heart disease and lower life expectancy than Western Europe. The results of a study suggest that industrial trans fats levels in pre-packaged biscuits, cakes and wafers in some Eastern and South-Eastern European countries have not dropped meaningfully since the mid-2000s. This suggests that in certain parts of the EU little progress has been made, while in some Western EU countries reductions were achieved. The European consumer association BEUC highlighted in their position paper on trans fats in 2014, that regional inequalities between Western versus Eastern EU countries persist, citing results from product testing, which showed consumers in Eastern EU countries are more exposed to industrial trans fats than their Western neighbours. A test on margarines and wafers carried out by the Czech consumer association in 2013 and 2014 confirmed that reformulation efforts have not been equal in Eastern and Western EU countries. According to a published study, the same product categories would contain minimal amounts of industrial trans fats, while in Eastern Europe, substantial contents of trans fats were found. Figure 1 summarises the problems, drivers and objectives associated with industrial trans fats in the EU.

Figure 1 Illustrative summary of the problems, drivers and objectives associated with industrial trans fats in the EU

Figure 1 Illustrative summary of the problems, drivers and objectives associated with industrial trans fats in the EU

5.What are the available policy options?

5.1.What is the baseline from which options are assessed?

In the baseline scenario, option 0, no initiative would be taken on trans fats at EU level. The qualitative and quantitative analysis was informed by the baseline scenario of a study completed by the JRC and the qualitative evidence collected in the external study by ICF.

The JRC study highlighted that the assumed baseline of 10 years in their modelling exercise was chosen as a rather conservative approach to show that measures which are cost effective under this very conservative assumption would prove even more cost effective under any further, less conservative baseline scenario.

The assessment methodology was designed to accommodate uncertainty about the future trend in industrial trans fats intake in the absence of EU action (the baseline scenario). The purpose was to reinforce the analysis by referring to three possible future trends (baselines), taking into account uncertainty rather than focusing on one scenario only.

It is suggested that industrial trans fats levels in food have been declining over time under the influence of various factors, while there is also some evidence that the decline has levelled off, according to the ICF study. In its recent public health economic evaluation32, the JRC extrapolated from available evidence and based its modelling on the assumption that industrial trans fats would be completely removed from the EU food supply chain in 10 years. While data gathered for the study by ICF confirm this trend, it shows also that most changes that could be triggered in the absence of EU policy action have already taken place, either as a result of voluntary initiatives or national legislation. Nevertheless, levels of industrial trans fats in foods appear to remain high in certain countries and certain sub-groups of food businesses, particularly SMEs.

A continuous downward trend in the years to come is not certain. Industry in some Member States has not acted voluntarily on industrial trans fats, and the evidence from certain Member States collected by ICF suggests that a voluntary approach may not deliver any progress there. Data on the industrial trans fats content of foods manufactured and sold in some Member States

suggests that, in spite of reductions in certain categories of products, levels of industrial trans fats in other food products remain high. The evidence on voluntary industry initiatives collected by ICF strongly suggests that potential action by those sectors willing to act and sufficiently well organised at national and EU level to carry out coordinated reductions in industrial trans fats havs already been carried out. Other sectors and countries that have not acted voluntarily are highly unlikely to do so in the near future. Further evidence collected in six countries (including the EU Member States Croatia and Slovenia) has found that the number of packages of food products (considering the group of biscuits, cakes, wafers) that contained more than 2% of total fat as industrial trans fats had doubled between 2012 and 2014

, indicating that food industry operators had expanded their offer of products with high industrial trans fats content, contradicting the notion of a general downward trend. Further evidence for actual increases of industrial trans fats exposure, particularly in Eastern Europe, is provided in a recent, unpublished study in Hungary, the outcome of a collaborative agreement between the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe which supported the process and technical product, and the Ministry of Human Capacities of Hungary. Hungary introduced its national legal limit in February 2014 with a transition period of 1 year. In the years proceeding to the enforcement of the national legislation, a steady increase in the percentage of products above the legal limit could be observed: 2009/2010 16% of products surveyed, 2011 27 %, 2012 29 %, respectively.

Figure 2: Compliance with the Hungarian national legal limit by year (%)

Substantial improvements were only seen from the period where the national legal limit had been decided and notified to the EU, in 2013 with 11% of the sampled products above the legal limit, with following steady declines, 2014 7%, 2015 6 % and 2016 2%, showing the effectiveness of a legal limit to revert an increasing trend of products with high industrial trans fats levels on the market. This development is illustrated in Figure 2

Likewise, mean trans fats content in products was seen to steadily increase on the Hungarian market until a national legal limit was decided, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Mean trans fats content (g/100 g food) in the food samples by year in Hungary

|

Year

|

N

|

Mean

|

SD

|

Minimum

|

Maximum

|

|

2009/2010

|

396

|

0.55

|

1.46

|

0

|

15.36

|

|

2011

|

125

|

0.76

|

1.67

|

0

|

11.84

|

|

2012

|

210

|

0.70

|

1.41

|

0

|

10

|

|

2013

|

169

|

0.53

|

2.02

|

0

|

14.43

|

|

2014

|

306

|

0.26

|

0.42

|

0

|

3.46

|

|

2015

|

266

|

0.29

|

0.99

|

0

|

10.19

|

|

2016

|

114

|

0.20

|

0.41

|

0.004

|

3.53

|

Possible reasons for increased levels of industrial trans fats in foods are, for instance, availability of food ingredients with high industrial trans fats levels at low prices, a high price sensitivity of consumers, low responsiveness of food business operators to respond to calls for voluntary reformulation and a perceived low reputational risk for food business operators linked to the offer of products with high levels of industrial trans fats. For the Hungarian example described above, it was not possible to determine whether products with high industrial trans fats levels were imported as information was only available about the distributor and not about the manufacturer.

Of note, the national legal measures prohibit the sale of non-complying foods on the national territory, while non complying foods may still be legally produced for export.

A number of published evidence, including research articles, were available for citation to provide evidence, apart from data on trans fats levels collected by JRC, showing and confirming higher levels of industrial trans fats, particularly also in Eastern European countries . Despite this fact, the validity of assuming a baseline scenario of no change has been confirmed by ICF. ICF conducted an online consultation to maximise their ability to validate the data collected during desk research and expert interviews and triangulate the findings from the impact assessment with a wide range of stakeholders. This enabled ascertaining the validity of key elements of the analysis. The first part of the consultation posed general questions on current and predicted industrial trans fats use under different policy options. Overall the results from the ICF consultation have confirmed the appropriateness of the assumptions and estimates, while they have helped to qualify the baseline scenario. According to the ICF research, levels of industrial trans fats are not necessarily declining in the coming years. While data gathered for the ICF study confirm a trend towards industrial trans fats reduction in food products, it shows also that most changes that could be triggered in the absence of EU policy have already taken place, either as a result of voluntary initiatives or national legislation.

This suggests that obstacles stand in the way of further changes and of further diffusion of initiatives, either private or public, to that part of the EU food industry that has not yet reduced industrial trans fats levels in its products. Whether these obstacles would be removed in the absence of EU activity is not clear from the evidence that has been gathered by ICF. A continuous downward trend in the years to come is therefore not certain.

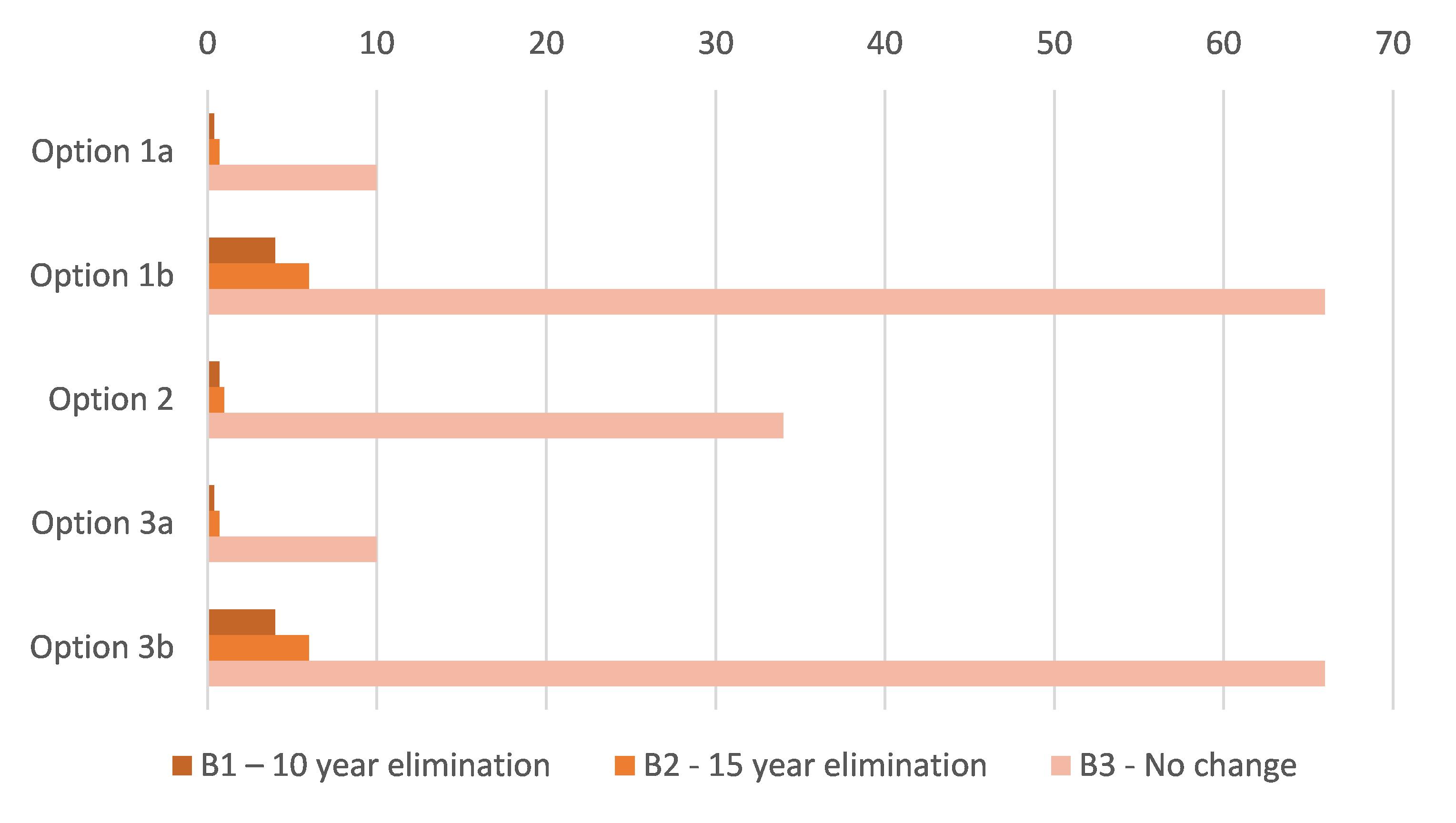

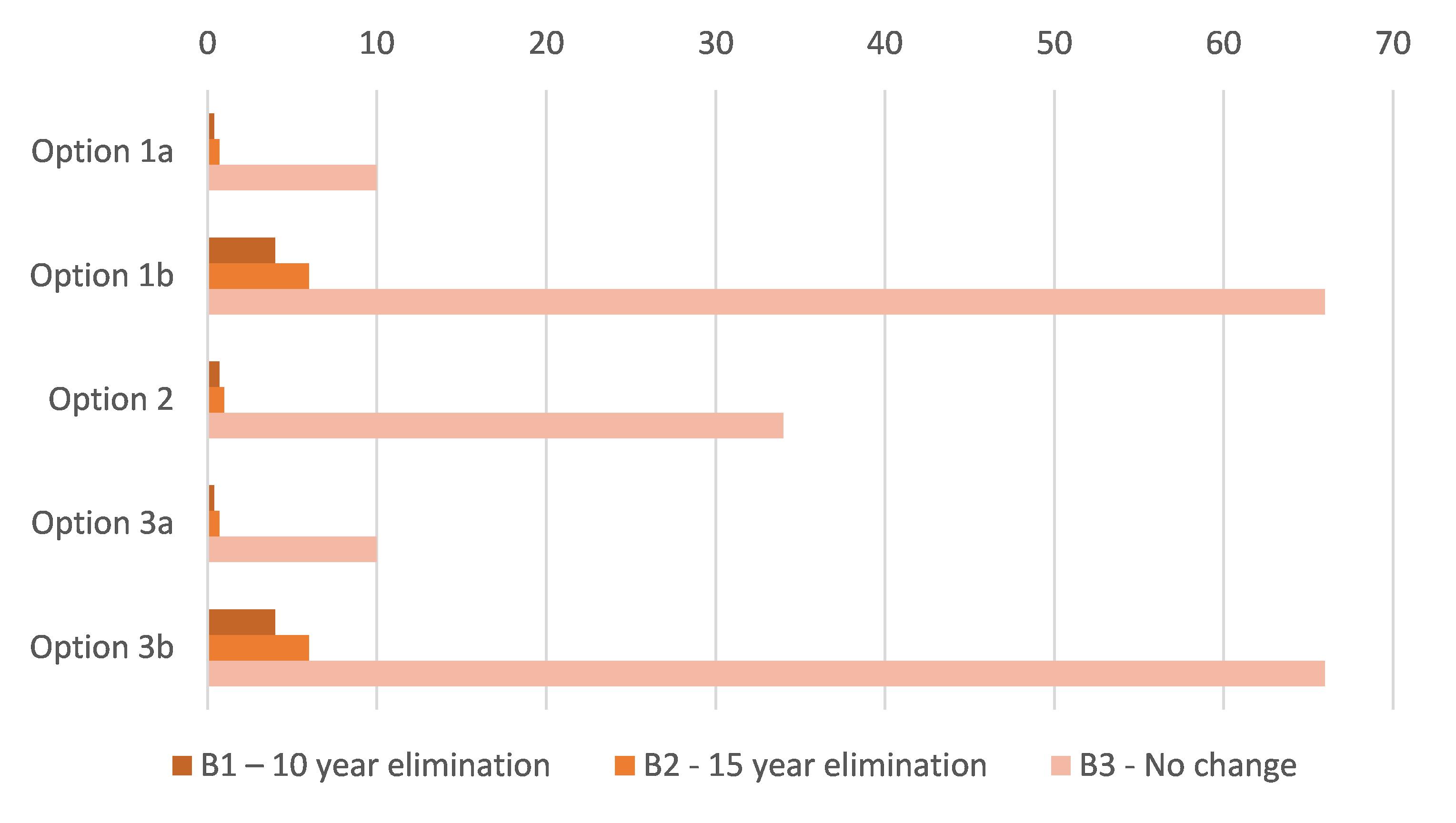

This uncertainty in the baseline is mitigated by the analytical approach; three variants of the baseline scenario have been adopted to capture that uncertainty, about how trans fat intakes may develop in the future. The policy options are compared against each variant. This approach helps to ensure that the conclusions about the absolute and relative impacts of options are robust in the context of all foreseen reference scenarios, thereby accommodating the uncertainty about future evolution of the problem in the absence of further EU action (cf Figure 2):

·A continuous decrease leading to the complete elimination of industrial trans fats from the food chain over a period of 10 years (B1 – ’10 year elimination’);

·A continuous decrease leading to the complete elimination of industrial trans fats from the food chain over a period of 15 years (B2 – ’15 year elimination’);

·Industrial trans fats intake remains constant at current levels (B3 – ‘no change’).

The three variants of the baseline represent the spectrum of expected possible trajectories – industrial trans fats intake remaining constant at current levels, a linear decline in industrial trans fats intake to zero over 15 years and an accelerated linear decline to zero over 10 years.

From an impact appraisal perspective, the first variant (B1) is conservative: An option that is cost-effective under the first variant (B1) would be even more cost-effective under the other variants.

Figure 3 Dynamic baseline: illustrative representation of how benefits of industrial trans fats control arise compared to the variants of the baseline scenario(source: ICF)

iTFA : industrial trans fats

5.2.Description of the policy options

Overall, three options were considered, option 1 and 3 were subdivided into two sub options each to consider different instruments. Logic models and theories of change for each option are presented in Annex 11, Figure 4 describes potential dietary sources of trans fats and indicates where the different options affect those sources.

Figure 4 Overview of potential dietary sources of trans fats and where the different options affect the (% trans fats are given as % of fat content)

FBO: food business operator

Option 1 – Establishment of a limit for the industrial trans fats content in foods

In this option, the EU would establish a limit for the presence of industrial trans fats in foods, both pre-packed and non-pre-packed.

Different limits could be considered, one possibility would be to set the limit of industrial trans fats at 2% of the total fat content of the food, in line with the approach followed in seven Member States that have already taken legislative action on the matter. This limit could be set through different instruments:

Option 1a: Voluntary agreement with the relevant food business operators to set a limit for industrial trans fats content in foods

In option 1a, a limit for industrial trans fats content in foods would be established by a voluntary agreement at European level between relevant food business operators. The agreement as a form of self-regulation would be under the auspices of the Commission, and involve EU-level representative organisations from the industry, themselves representing both national federations of companies and large companies operating across many countries of the EU.

Since some industry sectors are not organised and represented at EU level, this would not be fully inclusive. Voluntary agreements would primarily focus on foods sold to the consumer (and not include ingredients that are sold as inputs to final products).

The agreement is assumed to include an annual reporting requirement for participants. Industry associations would collect and report the information on behalf of their members. This information could be commercially sensitive, and business associations would need to operate as a “safe space”

, collecting and anonymizing the information from its members so that it may then be publicised. Such arrangements would build upon the examples of voluntary agreements to reduce industrial trans fats content in food which have been implemented in Germany and in the Netherlands.

It is assumed that the agreement would set a target of achieving levels of industrial trans fats in food products below 2% of fat within a period of 3 years. The evidence collected by ICF suggests that such a timespan would enable producers to factor reformulation into their regular cycle of product review and reformulation (whereas legislation might impose a shorter transition period for businesses).

Reporting obligations (and so the associated costs) would continue to apply even after the participating sectors had reduced industrial trans fats content to below the threshold. A review mechanism and ‘sunset clause’ by which reporting requirements lapsed a specified period after objectives had been met would mitigate ongoing costs incurred even after industrial trans fats had been reduced to levels below 2% of fat. There would be a credible incentive for Member States that legislation would be introduced in the absence of progress.

A part of the food business operators that participated in the consultations favour a voluntary approach with regard to a legal limit, as more flexibility to act would be given. Generally, neither consumers nor NGOs favour this approach as it does not guarantee a high level of health protection. Public authorities think this option is somewhat appropriate as it could deliver some results, while most Member States support a harmonised, legal European approach (option 1b) ensuring the Internal Market and fair competition between food business operators in all EU Member States.

Option 1b: Legally-binding measure to set a limit for industrial trans fats content in foods

In Option 1b, EU legislation would set a limit industrial trans fats content of 2% of the total fat content of final food products sold to the consumer, following the example of 2% limits to final food products in some Member States' legislation. The 2% limit assuming it applies to all products consumed in a very conservative scenario means in practical terms an intake of between 0.6 and 0.7 % of energy intake from industrial trans fats for a large number of average consumers (between 33 and 60 %) in the EU. A 2 % limit applies to the content in the particular food or product and it would still enable minimal use of partly hydrogenated oils as raw ingredients containing industrial trans fats by the industry, e.g. for the manufacture of additives. Such additives could continue to be used, provided that the total industrial trans fats content of the final food sold to the consumer meets the 2% limit on fat basis.

In order to implement option 1b, it is assumed that the majority of food ingredients in the EU will comply with the legal limit, so that food manufacturers are sure to comply with the legal limit and that most food manufacturers that buy ingredients will ask for a industrial trans fats specification of not more than 2% of their supplier. In specific cases, ingredients with higher industrial trans fats levels could be used, as explained above. The enforcement of option 1b includes testing of final food products in the market for their industrial trans fats level. The JRC has proposed assessment methods for industrial trans fats and developed a standardised calculation method to estimate the industrial trans fats level in a food that contains industrial and ruminant trans fats.

Alternatively, a more differentiated approach could be chosen, with higher limits (above 2% of total fat) for products with low fat content, and 2% of total fat for food categories with high fat content. Such differentiated limits have been adopted in some Member States. Consistently with the modelling study by the JRC, a transition period of 2 years is assumed.

A large part of the food business operators that contributed during the various consultations favour this option that is achievable and provides a level playing field and avoids any further fragmenting of the EU Internal Market. Also, most public authorities and Member States, as well as consumers, and NGOs favour this approach as it guarantees a high level of health protection, is in line with certain national legal measures already in force in the EU, as it is ensuring the Internal Market and fair competition between food business operators in all EU Member States.

Limits below 2 % of fat content were not considered in detail in this IA. During the normal refining steps (deodorisation) of oils that contain high levels of polyunsaturated fats industrial trans fats can be formed, even if the oil is not undergoing partial hydrogenation. Oils with a high content of polyunsaturated fats, providing essential nutrients, are generally recommended as a part of a healthy diet. Also, in food service establishments, during normal frying processes trans fats are formed to a certain degree. It would not be proportionate to ask small food business operators active in food service to frequently control the level of trans fats produced in the frying oils to ensure that a low threshold limit is not exceeded. The 2 % limit on fat basis has been found to be in line with the need to accommodate trans fats levels generated during normal oil and food processing. However, empirical evidence shows, that with this threshold, very low average intake levels of industrial trans fats, in the order of 0.009 %, were achieved with the legal limit of 2 % per 100 g fat content. Therefore, the 2 % limit was assumed to achieve a high level of health protection while being technologically feasible for food business operators.

Option 2 – Introduction of the obligation to indicate the trans fats content of foods in the nutrition declaration

Option 2 involves the introduction of an obligation to indicate the trans fats content as part of the (mandatory) nutrition declaration for pre-packed foods. This would provide incentives to the industry to reformulate and reduce trans fats from food products and enable consumers to make informed food choices.

The labelling obligation would be required for all foods that carry a nutrition declaration, with resulting costs even for foods free of trans fats, while non pre-packed foods e.g. in restaurants, are out of scope. Where applicable, the nutrition declaration would describe total trans fats content, both ruminant and industrial trans fats.

A two-year transition period, would allow a majority of businesses to process label changes into their normal cycle of label updating.

A large part of the food business operators that contributed during the various consultations do not favour this option due to the high administrative burden and linked costs. Generally, food business operators active in the vegetable oils sector have been more favourable in principle, given that this measure also covers ruminant trans fats, while food business operators providing ruminant fat sources are not favourable to this option as they are unable to reformulate the basic fat composition of ruminant fats and fear negative impacts on the overall diet of consumers as a potential consequence. Consumers often point to their desire for transparency in relation to the foods they eat and prefer to be provided with comprehensive information, so they supported this option. Public authorities generally 'do not favour' this measure or only 'favour it somewhat' according to the results of the OPC; also NGOs do not largely support this option, one of the reason here being that labelling covers only part of the food offer, pre-packed foods, and therefore only part of the trans fats problem.

Option 3 – Prohibition of the use of partly hydrogenated oils in foods

In this option, the EU would follow a similar approach as adopted in the US and would prohibit the use of partly hydrogenated oils in foods, as primary dietary source of industrial trans fats. This could be achieved through a voluntary agreement with the relevant food business operators (sub-option 3a), or a legally-binding measure (sub-option 3b).

Option 3a – Voluntary measure to eliminate the use of partly hydrogenated oils

In Option 3a, partly hydrogenated oils would be removed from foods through a voluntary agreement negotiated and managed at European level. Food business operators would commit to the ban individually or through their representative associations.

The arrangements for the voluntary agreement would be similar to that for option 1a. There is currently no definition of partly hydrogenated oils in EU law or in the Codex Alimentarius. For the implementation of Option 3a, a definition of partly hydrogenated oils would need to be established at EU level, linked to a measurable indicator, which could then be relied on for monitoring purposes. The US Food & Drug Administration