Table of Contents of the Annexes (1/2)

Annex 1

Procedural information …………………………………………………….1

Annex 2:

Stakeholder consultation …………………………………………………....9

Annex 3:

Who is affected and how? …………………………………………………18

Annex 4:

Analytical model used ……………………………………………………..20

Annex 5:

Minutes of the Ecodesign Consultation Forums ………………………...28

Annex 6:

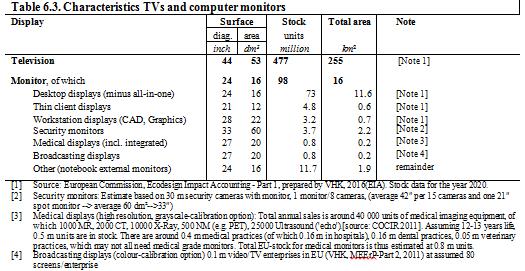

The market of electronic displays ………………………………………..58

Annex 7:

The Ecodesign and Energy Labelling Framework ……………………...75

Annex 8:

Existing Policies, Legislation and Standards on electronic displays …...79

Annex 9:

Evaluation of current regulations (REFIT) ……………………………...90

ANNEXES

Annex 1

Procedural information

1.Lead Directorates General (DG), Decide Planning/CWP references

DG GROW and DG ENER are Co-Chef de File for Ecodesign. DG ENER is the lead DG for this product group. DG ENER is Chef de File for energy labelling.

The Decide number of the underlying initiative for the review of ecodesign requirements for electronic displays is 2014/ENER/011 (no inception impact assessment because this is initiative predates the requirement).

The Decide number of the underlying initiative for the review of energy labelling for electronic displays is 2013/ENER/066 see above for the IIA & OPC.

The following DGs (Directorates General) were invited to contribute to this impact assessment: ENER (Energy), SG (Secretariat-General), GROW (Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs), ENV (Environment), CNECT (Communications Networks, Content and Technology), JUST (Justice and Consumers), ECFIN (Economic and Financial Affairs), REGIO (Regional policy), RTD (Research and Innovation), CLIMA (Climate Action), COMP (Competition), TAXUD (Taxation and Customs Union) EMPL (Employment), MOVE (Mobility and Transport), TRADE (Trade) and the JRC (Joint Research Centre) were consulted on the draft IA in May 2018.

2.Organisation and timing

The review of the ecodesign and energy labelling for televisions and television monitors started in 2012 and a review study was conducted for this purpose. This evaluated the impact of the current legislation, as reported in Annex 9, also looked at the technological and economic evolution of the sector and at stakeholders' views. Results from the study have been used directly as input to the analysis model of Annex 4.

The review process ran far longer than usual, with four Ecodesign Consultation Forums (in October 2009, October 2012, December 2014 and in July 2017; see Annex 5), while usually only one is needed. This happened largely because of political scrutiny at College level which led to long delays and the subsequent need to take into account technology evolution, market changes and new features introduced for TVs and displays.

The last Ecodesign Working Plan 2016-2019, adopted in November 2016, confirmed that televisions and electronic displays continue to be a priority product group. Furthermore, the recent Energy Labelling Regulation (EU) 2017/1369 stipulated that televisions are one of the five priority subjects for which the Commission should adopt a new energy label regulation in accordance with the said overall regulation by 2 November 2018.

Article 19 of the Ecodesign Directive foresees a regulatory procedure with scrutiny for the adoption of implementing measures. Article 17 of the Energy Labelling Regulation foresees consultation of the energy labelling expert group before the adoption of a delegated act. Subject to qualified majority support in the Regulatory Committee and after scrutiny of the European Parliament and of the Council, the adoption of the measures by the Commission is planned for the end of 2018.

3.Consultation of the RSB

The Regulatory Scrutiny Board (RSB) delivered a negative opinion on a draft of the Impact Assessment on 18 June 2018 after the meeting on 13 June. The draft report was subsequently improved, based on the Board’s Opinion and the “Horizontal issues for discussion” sent to DG ENER on 8 June 2018, and was resubmitted to the Board. A positive 2nd opinion with reservations was issued on 4 July 2018, containing further recommendations for improving the report The table below shows how those two sets of recommendations are addressed in this revised Impact Assessment report.

|

RSB Opinion

|

Where and how the comments have been taken into account

|

|

(B) Main considerations

|

|

|

(1) The report does not clearly draw conclusions from the evaluation(s) to support the problem definition.

It is unclear about the success of the previous measures and the discontinuity in projections.

|

Information has been added to section 1.1 and to the problem definition which gives more information on how the evaluation process fed into the problem definition. Information has also been added to section 6.

In Annex 2 a description of the full review process, started in 2012, with even preliminary discussion in 2009, is now presented. The results of the preparatory study/evaluation are summarised as well as the evolution of the need to act

Information on the savings achieved has been added to the introduction, see pages 3-4, as well as at the end of the new section 1.5 on need to act and in Annex 9.

Sections 1 and 2 in particular have been enriched and content partially reorganised to better describe the success of the current Regulations in reducing energy consumption and the need to act to capture the relevant future potential savings that, otherwise, would be missed in a BAU scenario.

|

|

(2) The report is not precise enough on the content of the options and does not sufficiently explain future developments in prices and energy savings.

It contains factual and numerical errors, which do not provide the necessary guarantees for the choice of the preferred option.

|

Section 6.1 illustrates the methodology and key assumptions in respect to prices.

A graph in this same section (Figure 18) illustrates the expected progress in terms of populating the highest energy classes.

In the specific market sector of electronic displays, the evolution of prices has no demonstrated correlation with energy efficiency improvements. Moreover, for the same efficiency class, the cost of new products tends to decrease. This is clarified in sections 6.4, 6.6.1 and in Annex 6.

The values in the tables related to the Ambi scenario have been corrected (see Annex 4, tables 4.4 and 4.5), however no change in future projections resulted for inputs.

|

|

(3) The report does not integrate circular economy aspects comprehensively and in a way which is consistent across ecodesign products. It does not impact assess them either.

|

See new information added to sections 2.3, 6.2.3 and Annex 15. It is also explained that while circular economy aspects were not specifically impact assessed, they were discussed at the Consultation Forums (2012 – 2017).

|

|

(C) Further considerations and adjustment requirements

|

|

|

(1) The report should clarify whether horizontal and/or product specific evaluations were conducted to prepare this initiative.

In addition, it should clarify what the expectations were of the original legislation, to what extent the results deviate from them, and what are the lessons to draw for this.

Key conclusions should directly feed the scope and problem definition. In particular, the report should explain very clearly why the predicted savings on energy consumption in 2025 are now 27% lower than what was predicted in previous impact assessment from 2007.

|

The 2012 Review study was specifically on TVs and also covered monitors and signage.

Additional details evaluations and discussion with stakeholders along a process lasting over 6 years (including 4 Consultation Forums, a previous impact assessment approved by the IAB, a public consultation and WTO notification–Ecodesign only on a previous draft proposal) have been added to Annex 2.1.

Clarifications have been introduced in section 1.1 with a graph extended beyond 2025, better showing that the predicted and now achieved savings exceed predictions by about 7%)). It has been clarified how the lack of accuracy in the previous preparatory work was due to an unprecedented evolution of the sector during the preparatory work and in the lack of sales/stock data (now available and reliable).

Section 1.1 now better illustrates the situation and explains that real savings calculated on more reliable 2017 data show that projections to 2020 are in fact 7% better than predicted.

|

|

(2) The report should better explain the scope of the initiative and why it adds (only) signage displays.

The description of the options should become more precise.

The report should be clearer about what elements that have already been agreed upon and how stakeholder views shaped the options and influenced the choice of the preferred option.

Any divisive issues between stakeholders should be better explained.

|

Information has been added to section 2.2 “problem of outdated scope” to better explain the current scope and the proposed future scope, which covers computer monitors and signage displays as well as TVS.

Text has been added to section 5.2 to give more details on the options.

Annex 5 gives information on what aspects were discussed, and possibly agreed upon, by stakeholders in the Consultation Forum meetings (also summarised in Annex 2).

Stakeholder views have been added throughout section 5, see also Annex 2 section 4.

|

|

(3) The report should provide a more thorough analysis of the circular economy dimension of the initiative.

The limits to the approach need to be more transparent. The report should in particular expand on the impacts on the health and safety of the use of flame-retardants. The report should present the views of the different stakeholders and explain how it addressed them.

|

See answer B 3 above. A new section on “Effects on health” has been added to Annex 15, also summarised in section 6.2.3.

Stakeholder views are set out in 5, measure 5.

|

|

(4) The report should explain the evolution of the baseline in more detail. In particular, it is currently not clear why the ongoing trend of increasing energy efficiency seems to stop in 2024.

Errors in the impact analysis need to be corrected. In particular, inconsistencies across tables on the energy efficiency of the ambitious scenario need to be resolved. Assumptions around this scenario should be better substantiated.

The international comparison of ecodesign limits gives the impression that the proposed EU ecodesign limits are less ambitious than those of US, India and Korea. This issue should be better explained and the figure, if necessary, revised

|

See new text in section 5.2.1.

Figure 1 (previously in Annex 8) shows a comparison between the projections in the preparatory study of 2007 (up to 2025) and current projections (up to 2030). The trend to increasing energy use continues beyond 2025 but no prediction is available which is why the graph appears to stop.

The tables have been corrected to avoid any incorrect data interpretation. The two values spotted in table 4.4 were the result of the retroactive application of the modelling, with no consequence on the forecast for 2020

The previous graph for comparison of eco-design limits has been replaced by 3, more relevant graphs: see figures 11 (Proposed EU Ecodesign limits for 2020, 2022, 2024 compared to best performance grades in the US, India and Korea), 12 (Proposed Labelling top class compared with non EU energy efficient top class displays) and 14 (Proposed label classes compared with non-EU labelling schemes for a 40" (44dm2) HD display). These show that the proposed ecodesign limits are not less ambitious than those of US, India and Korea

|

|

(6) The monitoring and evaluation section should be strengthened to reflect how progress in this specific product group will be assessed.

|

The section has been integrated, particularly answering the question on "main indicators" to proof the success of the measure.

|

|

(7) This report should be streamlined as far as possible with the impact assessments accompanying the other proposals in this package of proposals for implementing legislation regarding ecodesign and energy labelling. It requires in particular that the specific characteristics of the product come out more clearly in the different sections of the impact assessment.

|

The structure of the report and the annexes has been harmonised as far as possible with the other impact assessments and further explanations of the specificities of TVs and monitors have been added to Annexes 6 and 14.

|

|

Horizontal Issues

|

|

|

1)

Evaluation of how product regulations have worked is not systematic.

|

See answer to B1

|

|

2)

The need to act is not always clear.

|

A new section 1.5 has been added.

|

|

3)

The approach to defining energy labelling bands for specific products does not seem consistent.

|

Information has been added to section 1.2.

|

|

4)

The reports are not transparent about what elements have already been agreed upon (and on what basis), and what is left open for political decision, i.e. what is to be assessed in an impact assessment.

|

See information added to section 5.1.

|

|

5)

The addition of circular economy requirements appears artificial

|

See answer B.3 above.

|

|

6)

There is no critical discussion whether the applied methodological approach (MEErP) is consistent with the extension of the framework

|

See new information in section 6.1 on the methodology used.

|

|

7)

The approach to a range of issues going beyond energy efficiency as such – new testing methods, scope, exceptions – is not explained for all product groups

|

See for example problem definition 2

|

|

8)

The assessment of some impacts is unclear, e.g. as regards the employment effects, potential cash-flow problems and business revenues

|

See section 6 on assessment of options

|

|

9) The choice of the preferred option is not always sufficiently well justified with the presented analysis.

|

See section 8.1

|

|

10) As the ecodesign and energy labelling proposals are to be adopted in a package, information about contributions from particular product groups need to be presented systematically and in ways that allow for comparisons.

|

See section 8.1

|

|

RSB Overall (second) Opinion 04.07.2018 – Positive with reservations

|

Where and how the comments have been taken into account

|

|

(B) Main considerations

|

|

|

The Board acknowledges the improved coverage of circular economy aspects and a better description of the consultation process. However, the report still contains significant shortcomings that need to be addressed. As a result, the Board expresses reservations and gives a positive opinion only on the understanding that the report shall be adjusted in order to integrate the Board's recommendations on the following key aspects.

(1) The report does not sufficiently distinguish between energy savings from technological changes that were the result of the current regulation and those that would likely have happened without it. Because of a similar issue in the analysed future scenarios, the effects of the proposed measures is likely to be overestimated.

(2) There are inconsistencies and errors in data in the report and annexes. Although this does not undermine the choice of preferred option, it puts into doubt the evidence supporting the intervention.

|

Additional text has been included in section 1.1.

The modelling has been checked and modified, and the revised data has been added to the report and the annexes where appropriate, in particular in Sections 6 and 7 of the main report and Annex 4.

|

|

(C) Further consideration and recommendations for improvement

|

|

|

(1) The report should present more evidence or analysis to distinguish the effects of autonomous technological progress from those of the current regulation. This is also of importance to establish an appropriate baseline. The current baseline assumes that energy savings for monitors will stop in 2018 and for televisions in 2027. The report should justify this assumption in a sector with strong technological progress (which is the argument to leave classes A and B of the proposed energy label empty).

|

Additional text has been added to Sections 1.1 and 5.2.1 on the baseline option.

|

|

(2) Numerical errors persist. The energy saving potential and greenhouse gas reductions presented in the graphs in the report are not consistent with the data in annex 4. Moreover, the corrected figures in the annex are not internally coherent. This should be fixed with adequate explanation for the non-expert reader to understand. Solid justification for the initiative depends on robust energy savings estimates.

|

The modelling has been checked and modified, and the revised data has been added to the report and the annexes where appropriate, in particular in Sections 6 and 7 of the main report and Annex 4.

|

|

(3) The report presents the options in more detail. However the report should be clearer on the rationale between the ecological option ('Eco') and the ambitious option ('Ambi'). The report should be more transparent on the implications on health and safety of maintaining flame retardants in the 'Eco' option, despite their serious toxicity, ecotoxicity and threat to the health of workers in the recycling industry. The report should explain the necessity of an option excluding signage displays from the scope of Energy labelling given the large consensus among stakeholders on the need to address signage displays.

|

Additional justifications have been added to section 5.2.2, page 33 on signage displays and section 5.2.2, page 34 on halogenated flame retardants.

|

|

(4) More specific indicators have been identified regarding monitoring. The report should provide information on how often progress will be assessed and it should also refer to the next review or evaluation planned or required by the parent legislation.

|

Text of Section 9 in the main IA report has been updated.

|

|

(5) The attached quantification tables of the various costs and benefits associated to the preferred option of this initiative need to be adjusted to reflect changed estimations of costs and benefits.

|

The relevant tables have been adjusted where appropriate as per the updated modelling results. See Annex 3.

|

4.Evidence, sources and quality

This impact assessment builds on the previous version that had been approved by the Impact Assessment Board on 4/9/2013. For this deep review and update, the main supporting studies were as follows:

·Review study 2012

·Study assessing consumer understanding of a draft energy label for electronic displays (2017)

·Evaluation of the Energy Labelling and Ecodesign Directives SWD(2015) 143 final

JRC studies were also relevant I particular on "circular economy" aspects such as durability, recyclability and flame retardants (see References in Annex 17). An external consultant was used to examine specific technical aspects.

Energy-relevant data about over 400 televisions on the market and other displays was also analysed

.

The Commission also established a dataset (see Annex13 for last dataset used) containing information about the environmental performance of electronic displays in support of the possible ecodesign and energy labelling measures, to support a proper ambition level and to reflect recent technology developments. The dataset was based on energy data been provided by industry representatives and integrated with additional data collected from official documentation of industry on the WEB. The different data sources have been compared to fine tune technology progress evolution and trends and update the impact assessment.

Based on these studies and this preparatory work, the Commission drafted the policy options presented in this Impact Assessment.

Stakeholder input received during the above review studies, the four Consultation Forums and the consultation on the Inception Impact Assessment for the Energy Label were also been taken into account.

Annex 2:

Stakeholder consultation

This Annex gives a brief summary of the consultation process. Details are given of how and which stakeholders were consulted. In addition, it explains how it was ensured that all stakeholders’ opinions on the key elements relevant for the IA were gathered.

There has been extensive consultation of stakeholders during the review studies, and before and after the Consultation Forum meetings. Further external expertise was collected and analysed during this unusually long process. The results of four stakeholder consultation forums are further described in this section.

1.Review study, evaluation and stakeholder consultations

In the period observed by the original preparatory study of 2006/2007 for the 2009 regulations and until 2008, the average energy consumption of displays did not decrease (see figure 2.1, from the 2012 preparatory study) and new technologies such as LCD panels with LED backlighting were considered just only a niche market. Since that time, the rapid development and market adoption of this technology and other energy saving technologies resulted in industry-led energy efficiency improvements faster than had been originally anticipated, with not efficient technologies voluntarily abandoned (such as "plasma" technology) by industry.

The new process of reviewing the ecodesign and energy labelling regulations on televisions and television monitors started in 2012 when stakeholders in the Consultation Forum agreed with the Commission that the existing regulations needed to be revised. EU and international stakeholders and Member State experts were consulted from the very beginning of the review work. Furthermore, displays other than televisions and television monitors, such as computer monitors or digital photo frames were included in the first Ecodesign Working Plan 2009-2011 (as ENER Lot 3) and possible measures were discussed at a Consultation Forum meeting on 8 October 2009.

The Review study was completed in August 2012. It provided the Commission with technical and market data used to evaluate the existing 2009 television regulations and to support the development of the new ecodesign and energy labelling proposals for electronic displays. Furthermore, market and technical data was acquired through several bilateral and multilateral meetings with stakeholders (in particular with DigitalEurope and EERA) from 2013 to 2017.

The review work included:

·analysis of power consumption of the products per unit of screen size for the various levels and label classes, in order to reassess minimum energy performance standards (MEPS) and energy classes and comparison with other non EU legislation for MEPS or voluntary labelling;

·discussion of the impact of the Ecodesign and Energy Labelling Regulations to that date, with a historical review of the market changes over the previous five years;

·an overview of the key issues that required consideration in the context of reviewing and revising the Regulations;

·discussion of scope of coverage and definitions, technology trends and product features (i.e., screen size, LED back lit LCD displays, 3D, smart products, automatic brightness control, fast start and stand-by);

·an overview of the existing ecodesign requirements and an analysis on test data for televisions;

·a brief discussion of the measurement methods.

Among the different aspects that emerged from the data collection, studies and review , the following are the most relevant in this context:

·test standards and possible “defeat devices” (gaming);

·Signage displays, a new market and out of scope starting to emerge on the market;

·Auto Brightness Control (ABC) started to emerge as a feature; unprecedented technology progress in the area of display panels was observed;

·Ultra High Definition (UHD) was starting to come to the market in "premium" products, possibly involving a higher energy use; Monitors without "an included tuner" were increasingly used to watch video content;

·a linear limit, as in the current Regulations, provides an advantage to the biggest displays; (the weight of components not depending from the display size is smaller) and a misleading signal to customers;

·additional needs to for justifying the urgency of update the existing test standard and compliance control methods in order to prevent "defeat devices" in new "smart" products;

·need to provide a more realistic energy efficiency calculation for the biggest displays, in light of the trend to increase size and eliminating what appearing as a kind of privileged treatment;

·need to improve treatment of displays under the WEEE Directive form displays, by making disassembling/dismantling quicker and more effective and improving the yields of recyclable materials;

·the existing test standard IEC 62087, based on measuring the energy use of a television or other display when inputting from an external player a video test loop made of a collection of typical broadcast content from broadcasters worldwide, appeared already as possibly prone to "gaming", i.e. "smart" displays could detect the typical luminance test pattern and modify their energy use patterns to give misleading results.

2.Working document and Consultation Forum

The Commission services prepared Working Documents with ecodesign and energy labelling requirements which were circulated to the members of the Ecodesign Consultation Forum for the meeting on 8 October 2009. New working documents, based on the results of the Review Study 2012, were circulated to the members of the Ecodesign Consultation Forum for the meetings on 8 October 2012 and 10 December 2014. The last version was circulated and discussed at the Ecodesign Consultation Forum meeting of 6 July 2017. The Ecodesign Consultation Forum represents all EU Member States and EEA countries, together with industry associations and NGOs in line with Article 18 of the Ecodesign Directive. The Working Documents and the stakeholder comments received in writing before and after the Consultation Forum meetings were posted on the Commission’s CIRCA system. Minutes of the Consultation Forum meetings can be found in Annex 5.

3.Results of stakeholder consultation during and after the Consultation Forums

The 2012 review study was first discussed with stakeholders during a Consultation Forum on 8 October 2012 (see minutes in Annex 5.3).

The proposal then presented was based on the findings that had already emerged at that stage: a rapid evolution of TV technology, the introduction of new types of TVs, demand for improved picture quality, as well as strong competition between manufacturers.

A majority of stakeholders, including Member States, were in favour of a review of the Regulations, with increased stringency in Ecodesign, the use of the same formula in the Labelling regulation, widening the scope to include computer monitors and signage displays, and not providing an advantage to the biggest displays. Some Stakeholders already asked for the introduction of "non-energy" requirements in Ecodesign and the use of flame retardants was signalled as hindering recycling.

An overwhelming majority of Member States and NGOs agreed on a proposed extension of the requirements to electronic displays other than TVs, including but not limited to computer monitors and digital photo frames, with manufacturers requesting exceptions for specialised displays with distinct characteristics.

The majority of stakeholders accepted the proposed approach for regulating on-mode power demand of electronic displays and were in favour of a proposal that was based on a logarithmic regression line.

A majority of stakeholders were in favour of including in the proposal requirements on non-energy related aspects, including recyclability. At the same time they noted a need for proper measurement methods and questioned the enforceability of such requirements.

Results of the CF of 2014: The proposed ecodesign requirements for electronic displays were generally supported by Member States and stakeholders. A new Consultation Forum was held on 10 December 2014 (Minutes in Annex 5.2) with an improved ecodesign proposal including a first set of material efficiency requirements in the light of the "Circular Economy" strategy adopted in the meantime. Stakeholders, however, suggested in the meeting to suspend the preparation of the labelling proposal because of the ongoing review, at that time, of the Energy Labelling framework Directive.

Proposed resource efficiency requirements were supported by the overwhelming majority of stakeholders. Some specific requirements, however, criticized by industry representatives, were withdrawn from the draft proposal to avoid non-cost-effective burdens on the industry.

The working documents fully took on board comments expressed by Member States and stakeholders at and after the Consultation Forum meetings of 8 October 2012 and of 10 December 2014 (and thus differs in a number of aspects from the Commission’s original proposal as contained in the original working documents prepared for the consultation process).

Based on these inputs the Commission started reviewing the already approved 2013 Impact Assessment (see Annex 10) for the Ecodesign Regulation of electronic displays. Shortly after, the internal procedure was stalled again until the Commission adopted its Ecodesign Working Plan 2016-2019 where the revision of the implementing act for electronic displays is mentioned as one of the priorities. It also reports the situation that indeed the Ecodesign measure had been through the inter service consultation (ISC) and WTO notification and that a primary energy saving of 83 TWh was expected. In accordance with the “default” primary energy factor (PEF) of 2.5 set in the Energy Efficiency Directive (2012/27/EU) this means a saving of (at least) 33 TWh/year in electricity for the year 2030.

Public consultation

A previous version of the proposed ecodesign measure was notified in the "better regulation" web portal on 21 December 2016. 16 comments were received, mostly from manufacturers' representatives. A number of "position papers" were sent by manufacturer representatives to the Commission and members of the Consultation Forum as well.

Result of public consultations, WTO opinions and manufacturers positions expressed:

·the draft proposal included in the scope electronic displays "integrated" in a number of products subject to the WEEE Directive and possibly having a wide diffusion in future, such as computers refrigerators, vending machines, etc. however all manufacturers expressed concern about having different eco-design regulations on different components of the same product and clearly voiced a preference for "vertically" regulating the products (i.e. by including in the review of Ecodesign for a specific product the requirements for integrated displays, if any).

·Industries and associations of the chemical industry were against the specific wording in the draft proposal, referring to specific technology or techniques to glue components: this was mostly due to an unclear wording that has been corrected.

·Mandatory labelling of displays for presence or absence of mercury or cadmium was criticised, voicing for a mandatory requirement only for signalling "presence" of such dangerous substances.

·Environmental NGOs and recycling industries welcomed the proposal possibly banning use of welding or firm gluing for components to be removed at the recycling plant.

A further Consultation Forum was held on 6 July 2017 (Annex 5.1) where a new labelling proposal, in line with the new Energy Labelling framework Regulation 2017/1369 was discussed. The meeting also discussed a possible new label layout and the indicators to include, following the results of an on-going consumer understanding survey.

During the Consultation Forum, the "disputed" aspects of the Ecodesign proposal were discussed with stakeholders and in particular:

·"vertical" regulation: the Commission announced to stakeholders the clear preference of industry for regulating displays in the context of the product where they are integrated into;

·Use of glue: the Commission presented a new wording for the dismantling requirement that found industry relieved but the recycling industry disappointed;

Plastic marking and flame retardants: the Commission proposed to set a limit for marking of plastics parts only above 50 grams; the comments of the main stakeholders on key features of the Commission services’ Working Document received during and after the Consultation Forum can be summarised as follows:

·Scope: stakeholders agreed that integrated displays should not be covered, but agreed to the inclusion of signage displays.

·Energy Efficiency Index: stakeholders were concerned that the label be easily understood and support for the proposed double scale showing the energy efficiency in HDR mode was therefore mixed;

·Energy label classes: as the consumer study was still on-going discussion was to some extent limited, but DE, IT, NL, SE, ANEC/BEUC, DIGITALEUROPE, ENEL, and EED said it would be complicated to explain to consumers the relevance of the standardised EPS;

Circular economy aspects: EURIC, supported by EERA and FEAC, stressed the need for better design to facilitate recycling and fully capture the 'circular economy' potential.

4.Open public consultation

An online public consultation (OPC) took place from 12th February to 7th May 2018, with the aim to collect stakeholders' views on issues such as the expected effect of potential legislative measures on business and on energy consumption trends.

The OPC contained a common part on Ecodesign and Energy labelling, followed by product specific questions on (i) refrigerators, (ii) dishwashers, (iii) washing machines, (iii) televisions, (iv) electronic displays and (v) lighting.

1230 responses were received of which 67% were consumers and 19% businesses (of which three quarters were SMEs and one-quarter large companies). NGOs made up 6% of respondents, and 7% were "other" categories. National or local governments were under 1% of respondents, and 0.25% came from national Market Surveillance Authorities.

The countries of residence of the participants were predominantly the UK (41%) and Germany (26%), with a second group of Austria, Belgium, France, the Netherlands and Spain comprising together some 17%. Nine other Member States comprised another 9.5% of replies, but residents in 12 EU Member States gave either zero or a negligible number of responses. Non-EU respondents comprised around 5% of replies.

It should be noted that of the 1230 respondents, 719 (58%) replied only to lighting related questions as part of a coordinated campaign related to lighting in theatres. This was considered to significantly distort the replies, and for some questions the “lighting respondents” were removed from the calculation. Furthermore, as respondents did not have to reply to all questions, a high rate of “no answer” was observed (from 5% - up to 90%), in addition to those who replied “don’t know” or “no opinion”. To reflect better the actual answers, the number of “no answers” was deducted and the remaining answers treated as 100%.

4.1.Overall results

The first part of the questionnaire asked general questions aimed at EU citizens and stakeholders with no particular specialised knowledge of ecodesign and energy labelling regulations.

When asked regarding whether their professional activities related to products subject to Ecodesign or Energy Labelling, two-thirds (67%) of business respondents replied in the positive, and one-third (33%) in the negative, with no "no answer" replies. Almost the same percentages for "yes" (63%) and "no" (37%) were given when the business entities were asked whether they or their members knew of the Ecodesign requirements for one or more of the product groups concerned by the questionnaire, although this was reduced to 50% "yes" and 50% "no" when asked about Energy Labelling.

In reply to the question: "In your opinion, does the EU energy label help you (or your members) when deciding which product to buy?" 56% of the total respondents to the OPC gave a positive answer. Of the remainder, around 22% cited "don't know or no opinion", 3% did not reply and 19% responded negatively.

However, looking only at the ‘lighting respondents’ (526 of the total 1230), 73% of them replied ‘No’, ‘Don't know or no opinion’, or ‘no answer’. Given that the ‘lighting respondents’ mainly focused their comments on a narrow issue related to the current exemption for theatre lighting under ecodesign, the replies of these respondents to the earlier questions cannot necessarily be considered representative. Therefore, the calculation was also done with “lighting respondents” removed. Then, 84% of the respondents to the OPC agree that the EU Energy Label helps when deciding which product to buy. Of the remainder, around 7% cited "don't know or no opinion" or did not reply and 9% responded negatively.

When asked where they would look to find additional technical information about a product, respondents listed the following (more than one response permitted), ranked by the options provided: manufacturer's website (82%), the booklet of instructions (50%), [the Ecodesign] product information sheet (47%), internet user fora (39%), the retailer's website (18%), and consumer organisations (10%).

Some 63% of the participants were in favour of including Ecodesign requirements on reparability and durability, and 65% of respondents considered that this information should be on Energy Labels.

Regarding the reparability of products, participants valued mostly as "very important" to "important" (in the range 62%-68%) each of the following: a warranty, the availability of spare parts, and a complete manual for repair and maintenance. The delivery time of spare parts was rated as 56% "very important" to "important".

Small and Medium Enterprises (SME) Consultation [SMEs < 250 employees]

One of the aims of the OPC was to gather specific information on SMEs' roles and importance on the market, and to acquire more knowledge on how the aspects related to the environmental impacts of these six product groups were considered by SMEs.

The quali-quantitative evaluation of the effect on SMEs of potential regulatory measures for the environmental impact of all six product categories gave the following results. Approximately 10.5% or replies were from SMEs. These SMEs were involved in the following activities (most popular cited first): (i) product installation, (ii) rent/ leasing of appliances, (iii) repair, (iv) retail of appliances or spare parts, (v) final product manufacture/ assembly, (vi) sale of second-hand appliances, (vii) "other" activities, and (viii) manufacture of specific components.

In the OPC responses, SMEs reported that they were aware of the Ecodesign and EU Energy Label requirements applicable to the products they were involved in. Nevertheless, SMEs mostly declined to respond (90%) or replied in "don’t know/ no opinion" (6%) when asked about the potential impact on their businesses per se, or potential impacts on SMEs compared to larger enterprises, of the introduction of resource efficiency requirements in the revised Ecodesign and Energy Labelling regulations. Of those SMEs who gave an opinion, some 3-4% considered that the impacts could be negative, and around 1% thought that the effects would be positive.

4.2.Responses relating specifically to electronic displays

The consultation was mainly intended to gather opinions about information to be included on a redesigned energy label for displays regarding energy efficiency and durability, intended to be clear, self-explanatory and helpful to consumers making purchase choices.

Electronic displays are a relatively complex product. The label has to be designed in order to make instantly comparable different products with possibly very different technical characteristics. The power use of a display is influenced by its screen area, its resolution level, its backlighting technology, possibly the use of high dynamic range (HDR), refresh frequency and more. The label needs to be clear and not excessively crowded by information not crucial for comparison (more complete information can be found in an associated information sheet).

To help assess the user relevance of the information to be put on the label, the following questions where asked and the responses are illustrated below:

|

A new standard for improving image quality is HDR (High Dynamic Range). A display may even double its power use when displaying content filmed and broadcast in HDR. Would the indication of the power consumption in HDR mode be a relevant information for your purchase choice?

|

|

|

The current energy label for televisions indicates the "annual" energy consumption of the television. What assumptions should be used if the same indication will be provided in the new label (for televisions, computer monitors or other displays)?

|

|

|

One of the components more likely to fail in electronic products is the power supply (e.g. because of electric surges). Would you prefer a display with a standardised external power supply (as a USB with type-C connector) that you could easily buy and replace yourself?

|

|

|

What information would you like to have clearly provided when you buy an electronic display (television, computer display or similar)?: Measured average power used when "on" in normal mode (Watt)

|

|

|

What information would you like to have clearly provided when you buy an electronic display (television, computer display or similar)?: Measured average power used when "on" in HDR mode (Watt)

|

|

|

What information would you like to have clearly provided when you buy an electronic display (television, computer display or similar)?: Diagonal size (cm/inches)

|

|

|

What information would you like to have clearly provided when you buy an electronic display (television, computer display or similar)?: Resolution (horizontal x vertical) in pixels

|

|

|

What information would you like to have clearly provided when you buy an electronic display (television, computer display or similar)?: Nickname of the resolution level (e.g. UHD, WQHD, …)

|

|

|

What information would you like to have clearly provided when you buy an electronic display (television, computer display or similar)?: The power supply is external and standardised (e.g. USB Type-C)

|

|

|

What information would you like to have clearly provided when you buy an electronic display (television, computer display or similar)?: Presence of a TV tuner (i.e. to distinguish a TV from another display)

|

|

|

What information would you like to have clearly provided when you buy an electronic display (television, computer display or similar)?: Presence of a processor (i.e. to distinguish a smart TV)

|

|

|

What information would you like to have clearly provided when you buy an electronic display (television, computer display or similar)?: Network interfaces (i.e. WiFi, RJ45, etc.)

|

|

5.Impact Assessment (IA)

An IA is required when the expected economic, environmental or social impacts of EU action are likely to be significant.

The data collected in the review studies, see Annex 1.4, served as a basis for the IA. Additional data and information was collected and discussed by the IA study team with industry and experts, and other stakeholders including Member States.

This impact assessment builds on the previous version that had been approved by the Impact Assessment Board on 4/9/2013 (see Annex 10). In light of the rapid technology evolution, an update of the Impact Assessment was then deemed necessary, based on updated data, provided by industry and representing the market situation in July 2014. This new database of energy data was the evidence basis for re-visiting the draft Commission proposals, in particular the energy efficiency index calculation and the parameters to be set as minimum requirements and for establishing the energy class boundaries.

Annex 3:

Who is affected and how?

This annex explains the practical implications of a potential ecodesign and energy labelling measures based on implementation of the preferred policy option, see Section 6.

1.PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS OF THE INITIATIVE

The ecodesign regulation will apply to the manufacturers, importers and authorised representatives of displays (televisions and monitors) in the scope of the regulation.

The energy labelling regulations will apply to the suppliers and the dealers of displays (televisions and monitors) and signage displays in the scope of the regulations

They will need to with comply the ecodesign requirements summarised in the table below:

Summary of the Ecodesign requirements

2.SUMMARY OF COSTS AND BENEFITS

For the preferred option,

Tables

3.1 and 3.2 present the costs and benefits that were identified and assessed during the impact assessment process.

Table 3.1: Overview of Benefits (total for all provisions) as compared to the baseline– Preferred Option

Annex 4:

Analytical model used

1.GENERAL INTRODUCTION

General data availability for the scenario analyses of electronic displays is not good. For sales, stock and prices of displays there are GfK-studies periodically acquired by e.g. NGOs such as TopTen. For energy efficiency, however, data have been compiled ad-hoc, either by DigitalEurope or by researchers such as Intertek, Bob Harrison, CLASP and VHK.

For the impact analysis the dataset for 2017 was added. The reliability of most data could be checked by various sources and ultimately the data were confirmed by stakeholder consensus in various stakeholder meetings, bilateral and plenary. Employment impacts are derived from revenue per employee, again checked against reported revenue totals for the sector and anecdotal information from annual reports of individual manufacturers.

As regards the various monetary rates, the impact assessment study conforms to the MEErP. This means e.g. that (industrial) energy prices were assessed from Eurostat data and for future projections an escalation rate of 4% was used. All prices and costs are expressed in Euro 2010, calculated with historical inflation rates and a 2% inflation for future projections. For investment-type considerations, a discount rate of 4% is used.

In addition, a sensitivity analysis was carried out that calculates energy costs and consumer expenditure at an escalation rate of 1.5%. In short, this means that electricity tariffs in 2030 are not €0.36/kWh, but €0.24/kWh (all in Euro 2010).

For greenhouse gas emissions, the emission rate (in kg CO2 eq./kWh) does vary over the projection period in line with overall EU projections as indicated in MEErP.

2.MAIN CHARACTERISTICS OF THE MODEL

The impact assessment uses a stock model developed by VHK first in the context of the MEEuP 2005 methodology and then further developed in the MEErP 2011 and the VHK EIA-studies for the Commission. It has been used successfully, i.e. to the satisfaction of stakeholders and Commission, in over 20 impact assessment studies for Ecodesign and Energy Labelling studies where VHK assisted the Commission.

The stock model has been specifically developed and paid for by the Commission (DG GROW and DG ENER) and is thus subject to the same intellectual property provisions as other contract work for the Commission.

Over the years, as it was part of various Commission contracts it has been scrutinised by many Commission officials of various DGs as well as experts from various stakeholder groups (industry, Member States and NGOs).

3.MODEL STRUCTURE

The general structure of the model follows the format and conventions as laid down in the VHK EIA-study

. The following figure gives an illustration of the parameters used. The parameters with extension BAU are used for the baseline scenario. The parameters with extension ECO are used for one or more policy options (ECO1, ECO2, etc.).

Figure 4.1: Structure of core calculation

The model is built in a spreadsheet, using a 1 year time step. Every parameter name corresponds to an Excel sheet. Auxiliary sheets are added for the calculations.

In the case of electronic displays, 4 scenarios are calculated: BAU, ECO, Leni(ent) and Ambi(tious) scenarios all with televisions, monitors and signage displays in the scope.

The tables hereafter give the details of main inputs and outputs of the model.

4.INPUTS

|

Table 4.1. Inputs scenario calculation

|

|

Economic and energy data split-up by display type in scope

|

|

SALES, in million units

|

1990

|

1995

|

2000

|

2005

|

2010

|

2015

|

2020

|

2025

|

2030

|

2040

|

|

TV No NA ('standard')

|

26

|

29

|

34

|

46

|

56

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

TV LoNA

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

9

|

21

|

13

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

TV HiNA ('Smart')

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

9

|

21

|

39

|

60

|

69

|

70

|

|

subtotal TV

|

26

|

29

|

34

|

47

|

74

|

42

|

52

|

60

|

69

|

70

|

|

PC Monitor

|

10

|

13

|

17

|

22

|

25

|

14

|

14

|

14

|

14

|

14

|

|

Signage display

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

2

|

4

|

3

|

3

|

3

|

|

total

|

36

|

42

|

51

|

69

|

99

|

58

|

70

|

77

|

86

|

87

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

STOCK, in million units

|

1990

|

1995

|

2000

|

2005

|

2010

|

2015

|

2020

|

2025

|

2030

|

2040

|

|

TV No NA ('standard')

|

215

|

259

|

323

|

356

|

327

|

231

|

92

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

TV LoNA

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

18

|

98

|

164

|

109

|

27

|

0

|

|

TV HiNA ('Smart')

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

19

|

98

|

241

|

411

|

581

|

700

|

|

subtotal TV

|

215

|

259

|

323

|

357

|

364

|

426

|

497

|

520

|

608

|

700

|

|

PC Monitor

|

13

|

69

|

100

|

129

|

172

|

130

|

98

|

98

|

98

|

98

|

|

Signage display

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

7

|

21

|

31

|

31

|

30

|

|

total

|

443

|

586

|

745

|

842

|

901

|

990

|

1114

|

1169

|

1345

|

1528

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SURFACE/UNIT, in dm²/unit

|

1990

|

1995

|

2000

|

2005

|

2010

|

2015

|

2020

|

2025

|

2030

|

2040

|

|

TV average all types

|

10

|

11

|

13

|

19

|

28

|

43

|

51

|

59

|

68

|

92

|

|

PC Monitor average

|

5

|

6

|

8

|

10

|

11

|

13

|

16

|

18

|

20

|

25

|

|

Signage display average

|

16

|

18

|

21

|

32

|

46

|

71

|

84

|

97

|

113

|

151

|

|

sales wt.'d average

|

9

|

10

|

11

|

16

|

24

|

37

|

46

|

53

|

62

|

83

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SURFACE EU28, in km²

|

1990

|

1995

|

2000

|

2005

|

2010

|

2015

|

2020

|

2025

|

2030

|

2040

|

|

TV all types

|

21

|

29

|

40

|

69

|

102

|

185

|

253

|

306

|

415

|

642

|

|

PC Monitor

|

1

|

4

|

8

|

12

|

20

|

18

|

16

|

18

|

20

|

24

|

|

Signage display

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

5

|

18

|

30

|

34

|

45

|

|

total

|

22

|

33

|

48

|

82

|

122

|

207

|

287

|

353

|

469

|

711

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

On-mode specific electric power consumption of SALES in W/dm2

|

|

TV HD:

|

1990

|

1995

|

2000

|

2005

|

2010

|

2015

|

2020

|

2025

|

2030

|

2040

|

|

BAU

|

8,85

|

7,69

|

7,71

|

5,56

|

3,70

|

1,27

|

0,97

|

0,79

|

0,65

|

0,44

|

|

Leni/ECO/Ambi

|

8,85

|

7,69

|

7,71

|

5,56

|

3,70

|

1,27

|

0,96

|

0,60

|

0,35

|

0,35

|

|

TV UHD/3D:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3D/UHD% stock

|

0%

|

0%

|

0%

|

0%

|

4%

|

20%

|

50%

|

75%

|

100%

|

100%

|

|

BAU

|

8,85

|

7,69

|

7,71

|

5,56

|

3,78

|

1,40

|

1,21

|

1,08

|

0,97

|

0,66

|

|

Leni

|

8,85

|

7,69

|

7,71

|

5,56

|

3,78

|

1,40

|

1,20

|

0,83

|

0,53

|

0,53

|

|

ECO/Ambi

|

8,85

|

7,69

|

7,71

|

5,56

|

3,78

|

1,40

|

1,06

|

0,69

|

0,42

|

0,42

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Monitor HD:

|

1990

|

1990

|

1990

|

2005

|

2010

|

2015

|

2020

|

2025

|

2030

|

2040

|

|

BAU

|

8,85

|

7,69

|

7,71

|

5,56

|

3,70

|

1,27

|

1,16

|

1,05

|

0,95

|

0,78

|

|

Leni/ECO/Ambi

|

8,85

|

7,69

|

7,71

|

5,56

|

3,70

|

1,27

|

1,16

|

0,74

|

0,41

|

0,35

|

|

Monitor UHD:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

UHD% stock

|

0%

|

0%

|

0%

|

0%

|

2%

|

10%

|

25%

|

38%

|

50%

|

50%

|

|

BAU

|

8,85

|

7,69

|

7,71

|

5,56

|

3,74

|

1,33

|

1,30

|

1,24

|

1,19

|

0,97

|

|

Leni

|

8,85

|

7,69

|

7,71

|

5,56

|

3,74

|

1,33

|

1,31

|

0,88

|

0,51

|

0,43

|

|

ECO/Ambi

|

8,85

|

7,69

|

7,71

|

5,56

|

3,74

|

1,33

|

1,22

|

0,80

|

0,45

|

0,38

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Signage displays

|

as TVs multiplied by 2.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Standby mode electric power consumption of sales in W

|

|

|

|

|

1990

|

1995

|

2000

|

2005

|

2010

|

2015

|

2020

|

2025

|

2030

|

2040

|

|

TV No NA ('standard')

|

8,00

|

6,25

|

4,50

|

2,75

|

1,00

|

0,23

|

0,10

|

0,05

|

0,05

|

0,05

|

|

TV LoNA

|

0,00

|

0,00

|

0,00

|

2,00

|

2,00

|

2,00

|

2,00

|

2,00

|

2,00

|

2,00

|

|

TV HiNA ('Smart')

|

0,00

|

0,00

|

0,00

|

0,00

|

0,00

|

6,39

|

5,00

|

4,50

|

4,00

|

3,00

|

|

PC Monitor

|

9,00

|

7,07

|

5,14

|

3,20

|

1,27

|

0,41

|

0,25

|

0,15

|

0,15

|

0,15

|

|

Signage display

|

15% of on-mode energy use

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Standby mode hours per day

|

|

|

|

All scenarios

|

1990

|

1995

|

2000

|

2005

|

2010

|

2015

|

2020

|

2025

|

2030

|

2040

|

|

TV

|

6,00

|

9,50

|

13,00

|

16,50

|

10,00

|

10,00

|

10,00

|

10,00

|

10,00

|

10,00

|

|

PC Monitor

|

4,00

|

4,00

|

4,00

|

4,00

|

4,00

|

4,00

|

4,00

|

4,00

|

4,00

|

4,00

|

|

Signage display

|

15% of on-mode energy use

|

|

Note 1: For TVs and monitors average viewing hours are 4h/day. For signage 12h/day (average with wide spread). 365 d/yr.

|

|

Note 2: Until 2009 the non-viewing hours are considered standby-hours are considered a mix of passive standby (No NA) and hard off-switch (0W); in 2010 and later networked standby is considered significant and the power values are a mix of passive standby and networked standby.

|

|

Note 3: Signage displays have a high share of networked standby. It is considered that larger sizes have added complexity in that respect and thus standby is calculated as a percentage of on-mode.

|

|

Note 4: Meeting (networked) standby test data is not critical for display makers. That is why all scenarios have the same values in the model (although small differences can exist, but no specific information could be found). Networked standby can be problematic at the level of service providers overriding power management

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Retail prices (incl. VAT, in euros 2010 per unit)

|

|

|

|

|

1990

|

1995

|

2000

|

2005

|

2010

|

2015

|

2020

|

2025

|

2030

|

2040

|

|

TV

|

800

|

800

|

800

|

500

|

450

|

450

|

450

|

450

|

450

|

450

|

|

PC Monitor

|

200

|

200

|

200

|

200

|

170

|

170

|

170

|

170

|

170

|

170

|

|

Signage display

|

1600

|

1600

|

1600

|

1000

|

900

|

900

|

900

|

900

|

900

|

900

|

|

sales wt'd average

|

633

|

615

|

604

|

405

|

383

|

408

|

445

|

434

|

435

|

435

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Electricity Rates applied for displays (residential rates), in €/kwh elec (inflation corrected to euros 2010)

|

|

|

1990

|

1995

|

2000

|

2005

|

2010

|

2015

|

2020

|

2025

|

2030

|

2040

|

|

Default (4% escalation)

|

0,18

|

0,18

|

0,16

|

0,15

|

0,17

|

0,20

|

0,25

|

0,30

|

0,37

|

0,55

|

|

Sensitivity (1,5% escalation)

|

0,18

|

0,18

|

0,16

|

0,15

|

0,17

|

0,19

|

0,21

|

0,23

|

0,24

|

0,28

|

|

escalation rate applies from 2014 onwards (before 2014 historical prices)

|

5.OUTPUTS

|

Table 4.2. Outputs scenario calculation

|

|

OUTPUTS

|

per year

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

On-mode specific electric power consumption of STOCK in W/dm2

|

|

TV HD:

|

1990

|

1995

|

2000

|

2005

|

2010

|

2015

|

2020

|

2025

|

2030

|

2040

|

|

BAU

|

8,83

|

8,32

|

7,93

|

7,22

|

4,72

|

2,52

|

1,64

|

0,93

|

0,77

|

0,52

|

|

Leni/ECO/Ambi

|

8,83

|

8,32

|

7,93

|

7,22

|

4,72

|

2,52

|

1,64

|

0,87

|

0,57

|

0,35

|

|

TV UHD/3D:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3D/UHD% stock

|

0%

|

0%

|

0%

|

0%

|

4%

|

20%

|

50%

|

75%

|

100%

|

100%

|

|

BAU

|

8,83

|

8,32

|

7,93

|

7,22

|

4,82

|

2,78

|

2,05

|

1,28

|

1,15

|

0,79

|

|

Leni

|

8,83

|

8,32

|

7,93

|

7,22

|

4,82

|

2,78

|

2,05

|

1,20

|

0,85

|

0,53

|

|

ECO/Ambi

|

8,83

|

8,32

|

7,93

|

7,22

|

4,82

|

2,78

|

1,80

|

1,00

|

0,68

|

0,42

|

|

Average TVs

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BAU

|

8,83

|

8,32

|

7,93

|

7,22

|

4,73

|

2,57

|

1,84

|

1,20

|

1,15

|

0,79

|

|

Leni

|

8,83

|

8,32

|

7,93

|

7,22

|

4,73

|

2,57

|

1,84

|

1,12

|

0,85

|

0,53

|

|

ECO/Ambi

|

8,83

|

8,32

|

7,93

|

7,22

|

4,73

|

2,57

|

1,72

|

0,97

|

0,68

|

0,42

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Monitor HD:

|

1990

|

1995

|

2000

|

2005

|

2010

|

2015

|

2020

|

2025

|

2030

|

2040

|

|

BAU

|

9,51

|

8,25

|

7,64

|

7,26

|

5,06

|

2,93

|

1,25

|

1,11

|

1,01

|

0,83

|

|

Leni/ECO/Ambi

|

9,51

|

8,25

|

7,64

|

7,26

|

5,06

|

2,93

|

1,25

|

1,00

|

0,59

|

0,35

|

|

Monitor UHD:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

UHD% stock

|

0%

|

0%

|

0%

|

0%

|

2%

|

10%

|

25%

|

38%

|

50%

|

50%

|

|

BAU

|

9,51

|

8,25

|

7,64

|

7,26

|

5,11

|

3,08

|

1,40

|

1,32

|

1,26

|

1,03

|

|

Leni

|

9,51

|

8,25

|

7,64

|

7,26

|

5,11

|

3,08

|

1,40

|

1,18

|

0,74

|

0,44

|

|

ECO/Ambi

|

9,51

|

8,25

|

7,64

|

7,26

|

5,11

|

3,08

|

1,31

|

1,07

|

0,65

|

0,39

|

|

Average Monitors

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BAU

|

9,51

|

8,25

|

7,64

|

7,26

|

5,06

|

2,95

|

1,28

|

1,19

|

1,13

|

0,93

|

|

Leni

|

9,51

|

8,25

|

7,64

|

7,26

|

5,06

|

2,95

|

1,28

|

1,07

|

0,66

|

0,40

|

|

ECO/Ambi

|

9,51

|

8,25

|

7,64

|

7,26

|

5,06

|

2,95

|

1,26

|

1,02

|

0,62

|

0,37

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Signage displays

|

as TVs multiplied by 2. Leni and ECO follow TV BAU. Ambi follows TV ECO

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stock wt'd avg of the above, all types of displays

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1990

|

1995

|

2000

|

2005

|

2010

|

2015

|

2020

|

2025

|

2030

|

2040

|

|

BAU

|

8,87

|

8,30

|

7,86

|

7,23

|

4,84

|

2,69

|

1,82

|

1,25

|

1,20

|

0,83

|

|

Leni

|

8,87

|

8,30

|

7,86

|

7,23

|

4,84

|

2,69

|

1,82

|

1,17

|

0,89

|

0,55

|

|

ECO

|

8,87

|

8,30

|

7,86

|

7,23

|

4,84

|

2,69

|

1,71

|

1,02

|

0,70

|

0,43

|

|

Ambi

|

8,87

|

8,30

|

7,86

|

7,23

|

4,84

|

2,69

|

1,51

|

0,87

|

0,62

|

0,39

|

|

|

|

OUTPUTS

|

per year

|

accumulative

|

|

EU electricity consumption (in TWh/a, of stock)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1990

|

2005

|

2010

|

2015

|

2020

|

2025

|

2030

|

2040

|

2021-'30

|

2021-'40

|

|

BAU

|

36

|

92

|

92

|

98

|

94

|

90

|

98

|

98

|

927

|

1922

|

|

Lenient

|

36

|

92

|

92

|

98

|

94

|

86

|

82

|

75

|

863

|

1619

|

|

ECO

|

36

|

92

|

92

|

98

|

92

|

80

|

76

|

73

|

813

|

1538

|

|

Ambi

|

36

|

92

|

92

|

98

|

83

|

64

|

59

|

53

|

651

|

1178

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

EU GHG emissions (in Mt CO2 eq./a)

|

|

|

|

|

1990

|

2005

|

2010

|

2015

|

2020

|

2025

|

2030

|

2040

|

2021-'30

|

2021-'40

|

|

BAU

|

16

|

39

|

38

|

39

|

36

|

32

|

33

|

29

|

332

|

648

|

|

Lenient

|

16

|

39

|

38

|

39

|

36

|

31

|

28

|

23

|

309

|

550

|

|

ECO

|

16

|

39

|

38

|

39

|

35

|

29

|

26

|

22

|

291

|

522

|

|

Ambi

|

16

|

39

|

38

|

39

|

31

|

23

|

20

|

16

|

233

|

401

|

|

Consumer expenditure (in bn Euros 2010)

|

|

|

|

|

1990

|

2005

|

2010

|

2015

|

2020

|

2025

|

2030

|

2040

|

2021-'30

|

2021-'40

|

|

BAU

|

30

|

43

|

54

|

43

|

53

|

60

|

73

|

90

|

619

|

1448

|

|

Lenient

|

30

|

43

|

54

|

43

|

53

|

59

|

67

|

78

|

598

|

1316

|

|

ECO

|

30

|

43

|

54

|

43

|

53

|

57

|

65

|

77

|

581

|

1285

|

|

Ambi

|

30

|

43

|

54

|

43

|

50

|

52

|

58

|

66

|

531

|

1144

|

|

Acquisition costs (in bn Euros 2010, incl. VAT)

|

|

|

|

|

1990

|

2005

|

2010

|

2015

|

2020

|

2025

|

2030

|

2040

|

2021-'30

|

2021-'40

|

|

All scenarios

|

23

|

28

|

38

|

23

|

29

|

32

|

36

|

37

|

325

|

691

|

|

Energy costs (in bn Euros 2010)

|

|

|

|

|

1990

|

2005

|

2010

|

2015

|

2020

|

2025

|

2030

|

2040

|

2021-'30

|

2021-'40

|

|

BAU

|

6

|

14

|

16

|

20

|

23

|

27

|

36

|

53

|

289

|

747

|

|

Lenient

|

6

|

14

|

16

|

20

|

23

|

26

|

30

|

41

|

268

|

615

|

|

ECO

|

6

|

14

|

16

|

20

|

23

|

24

|

28

|

40

|

251

|

585

|

|

Ambi

|

6

|

14

|

16

|