EUROPEAN COMMISSION

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Brussels,7.3.2018

SWD(2018) 207 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

Country Report Spain 2018

x0009

Including an In-Depth Review on the prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances

Accompanying the document

COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK AND THE EUROGROUP

2018 European Semester: Assessment of progress on structural reforms, prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances, and results of in-depth reviews under Regulation (EU) No 1176/2011

{COM(2018) 120 final}

Contents

Executive summary

1.Economic situation and outlook

2.Progress with country-specific recommendations

3.Summary of the main findings from the Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure In-Depth Review

4.Reform priorities

4.1.Public finances and taxation

4.2.Financial sector and private sector debt

4.3.Labour market, education and social policies

4.4. Investment

4.5.Public administration

4.6. Sectoral policies

Overview TableAnnex A:

Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure ScoreboardAnnex B:

Standard TablesAnnex C:

References

LIST OF Tables

Table 1.1:Key economic and financial indicators — Spain

Table 2.1:Overall assessment of progress with 2017 CSRs

Table 3.1:Current account balance and net international investment position sensitivity analysis

Table 3.2:MIP Matrix

Table 4.2.1:Financial soundness indicators, all banks.

Table B.1:The Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure scoreboard for Spain ( AMR 2018)

Table C.1:Financial market indicators

Table C.2:Headline Social Scoreboard indicators

Table C.3:Labour market and education indicators

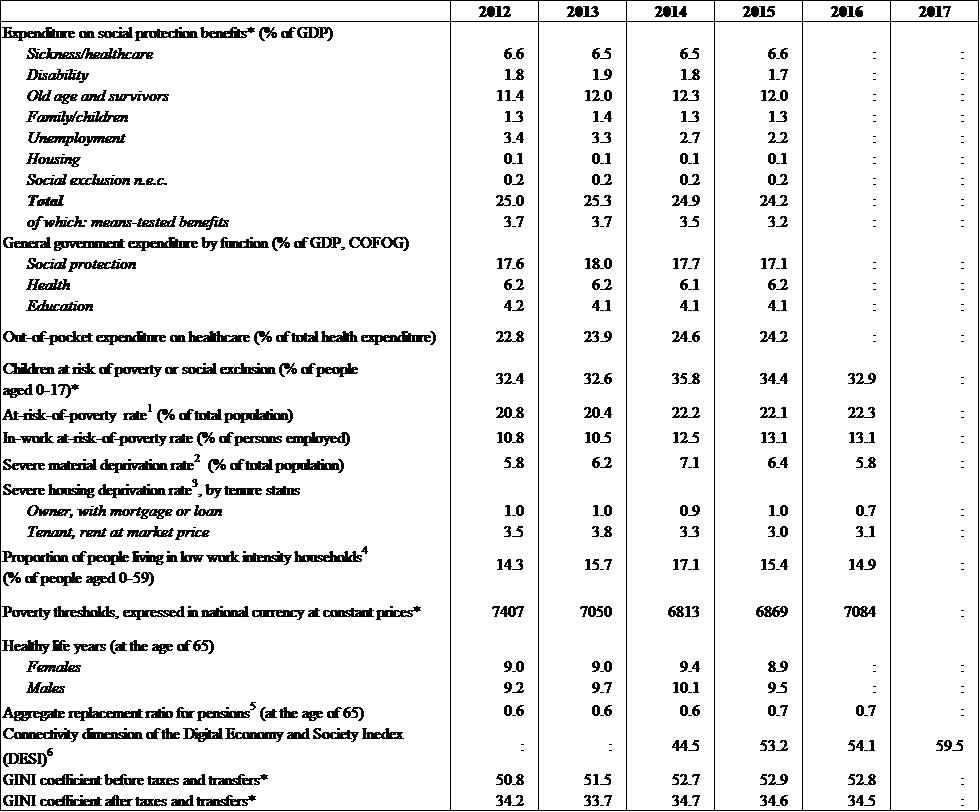

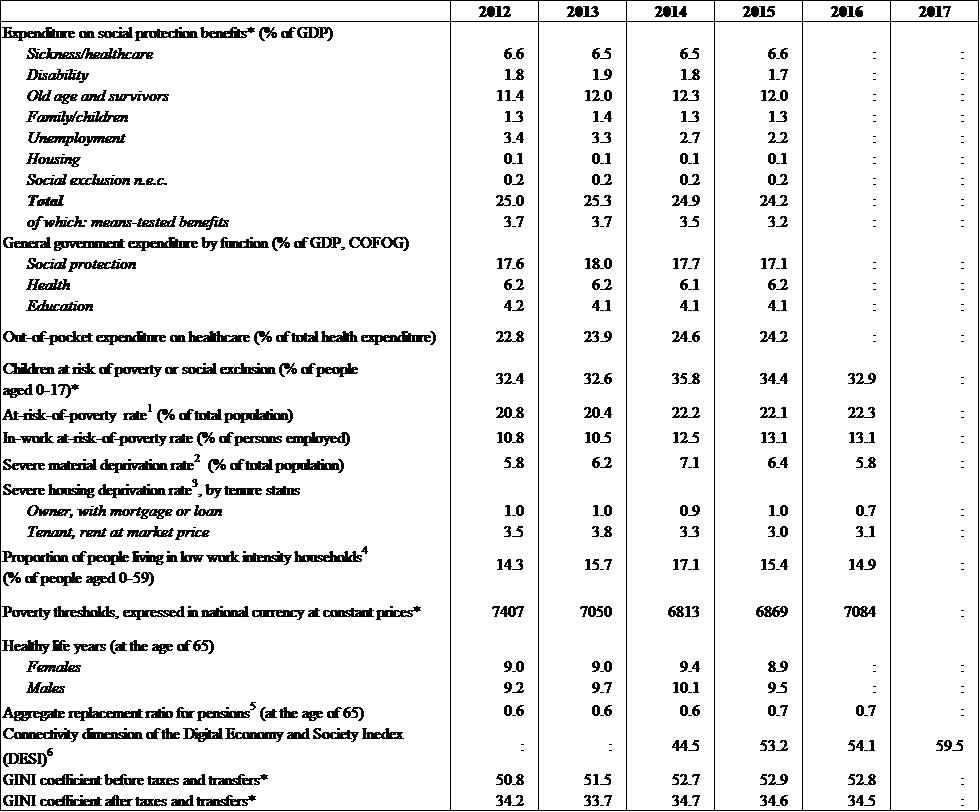

Table C.4:Social inclusion and health indicators72

Table C.5:Product market performance and policy indicators

Table C.6:Green growth

LIST OF Graphs

Graph 1.1:

Composition of GDP growth

Graph 1.2:

Contributions to potential growth

Graph 1.3:

Net lending / borrowing by sector

Graph 1.4:

Analysis of unit labour costs (ULC)

Graph 1.5:

Activity, unemployment, long-term unemployment, youth unemployment, NEET

Graph 1.6.1.a:

Regional disparities GDP per head1

Graph 1.6.1.b:Drivers of regional disparities GDP per head 2

Graph 1.6.2:

Spain — Breakdown of regional disparities in GDP per head (Theil index)

Graph 1.6.3:

GDP per head and total factor productivity, the activity and the unemployment rates for NUTS-2 regions from DE, ES, IT, FR and NL. 2014 data1, 2

Graph 2.1:

Overall multiannual implementation of 2011-2017 CSRs by February 2018

Graph 3.1:

Current account balance and net international investment position

Graph 3.2:

Analysis of the rate of change of NIIP — Spain

Graph 3.3:

External liabilities by sector-type of financial assets: change 2013-2017

Graph 4.1.3:

Government revenue by category

Graph 4.1.4:

Share of regions having complied with fiscal rules over 2013-2016 by GDP per head and by year (100% = 17 regions)

Graph 4.1.5:

Improvement in regional and local governments’ budget balance by component

Graph 4.2.1:

Sources of financing of the Spanish economy

Graph 4.2.2:

Loans to the private sector

Graph 4.2.3:

Composition of debt — ES

Graph 4.2.4:

Decomposition of y-o-y changes in debt-to-GDP ratios, households (ESA 2010) — Spain

Graph 4.2.5:

Gap to the fundamental-based and prudential benchmarks, HH and NFC

Graph 4.2.6:

Decomposition of y-o-y changes in debt-to-GDP ratios, quarterly non-consolidate data, non-financial corporations (ESA 2010) — ES

Graph 4.3.2:

Responsiveness of wages to unemployment by region

Graph 4.3.3:

Responsiveness of wages to productivity developments and regional changes in unemployment by sector (2012-2016)

Graph 4.3.4:

Employment by type

Graph 4.3.5:

Characteristics of temporary employment

Graph 4.3.6:

Share of temporary contracts in total employment by sector, ES v. EU

Graph 4.3.7:

At risk of poverty and social exclusion and its subcomponents

Graph 4.3.8:

At-risk-of-poverty gap

Graph 4.3.9:

In-work poverty by employment type

Graph 4.4.1:

Change in the balance of trade goods and services: exports and imports contribution

Graph 4.4.2:

Import content of GDP components in Spain

Graph 4.4.3:

ULC by sector

Graph 4.4.7.a:

Main determinants of Spanish exports

and imports performance(1)

Graph 4.4.7.b: Long term elasticities of imports (2)

Graph 4.4.4:

Spain's productivity gap vs. average of Germany, France and Italy, 2010 EUR/hour

Graph 4.4.8.1:

Change in share of GVA (1.a) and exports as % of gross output (1.b) by sector

Graph 4.4.8.2:

Change in FTE employment (2.a), and change in productivity (2.b), by sector

Graph 4.4.8.3:

Change in share of employment and productivity (3.a), and productivity and sectoral reallocation (3.b)

Graph 4.4.5:

Distribution of labour productivity growth in Spain (real value added by employee)

Graph 4.4.6:

R&D intensity projections, 2000-2020

LIST OF Boxes

Box 1.6: Spain. Regional disparities in GDP per head

Box 2.2: Tangible results delivered through EU support to structural change in Spain

Box 3.4.1: Euro area spillovers

Box 4.1.1: Medium-term projections of general government debt

Box 4.1.2: The Spanish pension system — reforms and challenges

Box 4.3.1: Monitoring performance in light of the European Pillar of Social Rights

36

Box 4.4.7: Assessing structural changes in Spanish exports and imports of goods and services: long-run elasticities to demand and competitiveness

49

Box 4.4.8: Sectoral rebalancing in Spain

51

Box 4.4.9: Investment challenges and reforms in Spain

57

Box 4.6.1: Policy highlights

63

Executive summary

Spain's continuing strong recovery is an opportunity to reinvigorate the reform momentum and complete earlier achievements. Economic activity and employment grew again strongly and imbalances further unwound in 2017. However, productivity is increasing slowly due to low innovation capacity and investment in knowledge and skills; and strong labour market segmentation and uneven social policy outcomes risk entrenching high income inequality. Addressing those challenges and ensuring full implementation of initiated reforms — such as in product markets regulation — could reduce the risk of a slowdown should the external economic environment and financial conditions become less supportive ().

The Spanish economy continued to grow above expectations and the euro area average in 2017. In its fourth year of expansion, Spanish real GDP surpassed its 2008 pre-crisis peak. Economic growth was driven by domestic demand, in particular private consumption, supported by high job creation. Investment, especially in equipment, also grew robustly. Exports consolidated their positive contribution to growth, supported by an increasing internationalization of Spanish firms and further cost-competitiveness gains. Overall, the growth of economic activity continued on a more balanced pattern than before the crisis.

Growth is expected to decelerate but remain robust. Ambitious structural reforms in the aftermath of the crisis set the foundations for the strong recovery. However, other supporting factors - namely low oil prices and the stimulus from tax cuts and improving financing conditions - are set to gradually subside. Private consumption is therefore set to moderate but remain a robust driver of growth. Investment growth is forecast to ease only slightly.

The economic rebalancing progressed further, but high debt levels and unemployment still represent vulnerabilities. External debt is still very high, despite the continued reduction driven by a sustained current account surplus. Private sector debt reduction also progressed, only slowed down by new credit finally starting to grow again. The public debt ratio has so far declined slowly, leaving sustainability risks elevated in the medium term. Unemployment has continued its rapid decline, but remains among the highest in the EU.

Spain represents a source of potential spillovers to the rest of the euro area. Simulations show that a decisive implementation of product market reforms in Spain would have a limited but positive impact on the growth of other euro area countries.

Spain has made overall limited progress in addressing the 2017 country-specific recommendations (CSRs). Spain made some progress in reforming public procurement, limited progress in strengthening the fiscal framework, and some progress in undertaking a comprehensive spending review. Some progress was achieved in reinforcing coordination between public employment services and social services. There was limited progress in promoting hiring on open-ended contracts, addressing disparities in income guarantee schemes and improving family support, as well as in increasing the labour market relevance of tertiary education and addressing regional disparities in educational outcomes. Finally, Spain made limited progress on the implementation of the law on market unity and on research and innovation investment and governance, although there was some improvement in the latter area.

Regarding progress in reaching the national targets under the Europe 2020 strategy, Spain is performing well in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and on track to achieve its renewable energy and energy efficiency targets. The tertiary education rate is close to the target. While sizeable gaps remain concerning the employment rate and early school leaving, they were again substantially reduced. By contrast, there was little progress towards the targets for R&D investment and reducing poverty risk.

Spain faces challenges with regard to a number of indicators of the Social Scoreboard supporting the European Pillar of Social Rights. As past efforts to promote employment creation are bearing fruit, the creation of permanent employment is slowly increasing in prevalence, but the use of temporary contracts remains widespread. Income inequality stabilised but it remains relatively high. Early school leaving keeps improving but, together with a high risk of poverty among children, weighs on equality of opportunities. The shares of people at risk of poverty and social exclusion and of young people not in employment, education and training are decreasing but call for close monitoring. The impact of social transfers (other than pensions) on poverty reduction is weak.

The main findings of the in-depth review contained in this report and the related policy challenges are as follows:

·Spain does not face immediate risks of fiscal stress, but medium-term sustainability risks remain high. The general government debt ratio is still high. Its reduction is projected to slightly accelerate in 2018-2019, also supported by strong nominal GDP growth, but the debt ratio is expected to remain around 95 % of GDP in the medium term. Projected savings in age-related expenditure attenuate fiscal sustainability risks. The efficiency of some spending items may benefit from the recently initiated spending review and the implementation of a new public procurement law.

·Private debt reduction has continued, but certain groups of firms and households remain highly indebted. Private debt both of companies and households has fallen further overall. Nominal GDP growth is increasingly driving the debt ratio reduction, allowing credit flows to households and firms, especially SMEs, to pick up in 2017. The still high level of indebtedness of some households and non-financial corporations, in particular low-income and jobless households and companies in the construction and the real estate sector, reduces their ability to weather potential shocks.

·Structural improvements in trade performance underpin the slow reduction of Spain's external liabilities. Exports' increasing geographical diversification and a rising number of regularly exporting companies have led to gains in export market shares, indicating a structural shift in Spain's export performance. Furthermore, the economy's increased reliance on domestically produced goods has restrained import growth. As a result, in 2017, the current account registered a surplus for the fifth consecutive year. Current account surpluses will need to be sustained for an extended period of time to decisively bring down the still very high external liabilities.

·Employment continued to grow at a robust pace and unemployment further fell rapidly, but is still very high. The strength of the labour market recovery is partly due to the impact of the past reforms and wage moderation. Both helped to increase the responsiveness of employment to economic growth. However, the unemployment rate remains among the highest in the EU. This is especially true for young people, implying a considerable untapped skills potential. Almost half of the unemployed have been jobless for more than a year. Spain is stepping up activation policies targeting the long-term unemployed, young people, and older workers. Nevertheless, their effectiveness largely depends on regional public employment services' capacity and coordination with employers and social services, which is only slowly improving.

·Productivity has grown in some sectors, but weak innovation and investment entrenches the productivity gap between the best and worst performers. Since the recovery started, productivity has grown more in the tradable than non-tradable sectors, both in manufacturing and services. In some tradable sectors — where Spain has some competitive advantage — productivity growth compares favourably with other large euro area countries. Still, the productivity performance across firms within sectors is very heterogeneous, which can be partly explained by weaknesses in innovation capacity and, to a lesser extent, investment in knowledge-based capital.

Other key structural issues analysed in this report, which point to particular challenges for Spain's economy, are the following:

·Spanish banks continued their stabilisation, while access to finance improved. The banking system as a whole comfortably meets the regulatory capital requirements and non-performing loans have been further reduced. The successful resolution of one bank in June 2017 contributed to strengthening the stability of the financial sector. Policies to support equity funding are proving effective.

·The widespread use of temporary contracts negatively affects productivity growth and income inequality. While permanent contracts are on the rise amongst newly employed workers, the share of employees on temporary contracts is still high. Young and low-skilled workers are most affected by temporary employment, which often fails to lead to a permanent job. This outlook reduces incentives for workers and employers to invest in training and lifelong education, thus eroding human capital formation, which in turn impedes faster productivity growth. Moreover, temporary workers are at a higher risk of poverty and tend to accumulate lower entitlements to social benefits. Spain is fighting the abuse of temporary contracts with growing success and plans to increase the share of permanent posts in the public administration. However, incentives to promote open-ended contracts in the private sector have so far had only small effects.

·Skills mismatches and gaps in educational outcomes also weigh on productivity growth. Tertiary graduates face difficulties in finding adequate jobs, and both over- and under-qualification are widespread in Spain. Though decreasing, the early school leaving rate remains amongst the highest in the EU and educational outcomes continue to vary considerably across regions. A high share of teachers is recruited on temporary contracts. The teaching and acquisition of digital skills is a challenge, which recent initiatives have started to address.

·The social situation continued to improve with economic and job growth, but income inequality and the share of population at risk of poverty remain high. The employment situation of household members plays an important role in this context. In 2016, the share of people at risk of poverty and social exclusion again decreased slightly, but remains high especially for jobless and single-earner households, as well as for children. In addition, family policies and social benefits, notably income guarantee schemes, suffer from uneven coverage and low effectiveness. High levels of income inequality, early school leaving and child poverty may negatively affect the equality of opportunities.

·While public procurement and the fight against corruption saw progress, advances to improve the business environment have slowed down. The law on market unity, subject of several rulings by the Constitutional Court in 2017, is still to be fully implemented. Regulatory disparities and restrictions keep mark-ups high, geographical mobility of companies and workers low, and productivity growth restrained. By contrast, a new law on public procurement, if implemented well, is likely to improve the efficiency and transparency of public procurement. The justice system's efficiency is being increased and the implementation of anti-corruption laws is making the business environment more attractive. The perception of the justice system's independence has improved.

·The innovation performance remains weak, despite governance improvements. Public and private investment in R&D remains subdued. Low capacity of small and medium enterprises to adopt innovations and take advantage of digitisation is a drag on Spain's longer-term productivity growth. Governance of research and innovation has been streamlined and made more inclusive, but coordination between government levels is still uneven and the lack of systematic evaluations prevents policy learning.

·Cross-border transport and energy connections, as well as water infrastructure, face investment gaps. Bottlenecks at Spain's borders impede a closer integration in the EU electricity and gas markets and slow down trade flows. Water governance is being improved, but there is underinvestment in supply and wastewater infrastructure.

1.

Economic situation and outlook

Economic growth

Economic growth continued exceeding expectations in 2017. The volume of GDP finally surpassed its pre-crisis peak in the second quarter of 2017, and growth remained robust in the third quarter, at 0.8 % q-o-q. According to the GDP flash estimate, growth slightly decreased to 0.7% q-o-q during the fourth quarter, bringing the annual growth rate for 2017 to 3.1%. The expansion is underpinned by a more balanced growth pattern than before the crisis. Domestic demand, and specifically private consumption, remains the main driver of growth, but net exports have also been contributing firmly to growth since 2016. The strength of the recovery and of job creation partly reflects the impact of the structural reforms implemented in the early years of the crisis, in particular the financial sector and labour market reforms.

|

Graph 1.1:Composition of GDP growth

|

|

|

|

Source: European Economic Forecast, autumn 2017

|

As favourable tailwinds subside, growth is expected to decelerate but remain robust. Real GDP growth is forecast to moderate to 2.6 % in 2018 and 2.1 % in 2019 (see Graph 1.1). () Private consumption is expected to slow down as job creation decelerates and the tailwinds that supported the growth of disposable income in recent years - i.e. declining oil prices, tax cuts and improving financial conditions - abate. However, private consumption is still projected to remain the main contributor to growth until 2019, as disposable income continues to increase and the financial position of households improves. After decelerating in 2016, growth of investment is expected to have rebounded in 2017, driven by residential construction. It is then set to ease slightly in 2018 and 2019, as equipment investment growth moderates in line with final demand. Downward risks to the outlook nevertheless exist, as uncertainty linked to the political situation in Catalonia could have a negative impact on growth, the size of which cannot be anticipated at this stage. At the same time, a stronger than expected recovery in other euro area countries is an upside risk for export growth.

|

Graph 1.2:Contributions to potential growth

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|

Potential growth is projected to increase slightly. After plummeting during the crisis years, potential output growth has started to recover, and is estimated to reach 1.2 % in 2019, but still remaining below the euro area average (1.5 %) (see Graph 1.2). More than half of this increase can be explained by a higher contribution of labour to potential output growth. Whereas the contribution of capital and total factor productivity (TFP) to potential output is now in line with the euro area average, the contribution of labour is still lower on account of a slowly declining, structural unemployment rate (NAWRU).

External position

The external sector is expected to continue contributing to GDP growth until 2019. Since 2016, import growth has remained contained, despite strong growth of domestic demand and accelerating exports, pointing to a reduction in import propensity (see Box 4.4.1). At the same time, structural improvements in export performance, underpinned by cost-competitiveness gains and an increase in the number of regular exporters, have contributed to sizeable gains in market shares in recent years. Both exports and imports are expected to have accelerated in 2017 as Spain's export markets recovered, before moderating in 2018 and 2019. Exports are expected to continue outpacing imports, and net trade should make a positive contribution to growth until 2019.

In 2017, the Spanish economy registered a current account surplus for the fifth year in a row. The current account surplus, after increasing in 2016, is expected to remain broadly stable at almost 2 % over the period 2017-19, as swings in the terms of trade due to oil price increases are largely offset by changes in export and import volumes. Given its large net stock of external debt, reductions in the cost of debt in recent years had a positive impact on Spain's income balance. However, the scope for additional improvements seems contained, as interest rates are not expected to reduce further. In cyclically-adjusted terms, the current account has continued to improve, again suggesting that the external surplus is increasingly driven by structural factors.

Current account surpluses are slowly translating into a reduction of Spain's net external liabilities. Despite the current account surpluses registered since 2013, negative valuation effects (partly reflecting improvements in confidence and higher value of Spanish assets) are limiting the improvements in the net international investment position (NIIP). Still, the NIIP has improved by more than 16 pps of GDP since its peak, but at -83.2 % of GDP in Q3-2017, it remains very negative. Changes in the structure of external liabilities in recent years in terms of sectors (e.g. being increasingly composed of public sector and central bank liabilities), type of instruments (e.g. a higher share of equity than in the past), and maturity (e.g. longer maturity of public debt), can mitigate some of the vulnerabilities associated with a highly negative NIIP. Going forward, the strong GDP growth, pickup in inflation and net external surpluses projected until 2019 should facilitate further improvements of the NIIP (See Section 3.2).

Private and public debt

The reduction in private sector debt is progressing but has slowed down. Despite its rapid decline, private sector debt remains high and deleveraging needs remain for both corporates and households (see Section 4.2). Nominal GDP growth has now become the main driver of the reduction in debt ratios. The deleveraging process has slowed down as new credit is growing strongly, especially for households and SMEs. Debt reduction, however, is taking place at a faster speed than suggested by fundamentals for both companies and households, indicating the excess of debt accumulated in the past is unwinding at a sufficient pace (European Commission 2017) (see Chapter 4.2).

The reduction of public sector debt is expected to gather pace. The general government debt ratio is expected to decline from 99 % in 2016 to about 95.5 % in 2019. After narrowing to 4.5 % of GDP in 2016, Spain’s general government deficit continued to decrease in the first three quarters of 2017, by 1.4 pps (see Graph 1.3). This reduction has relied on the improved macroeconomic outlook but also on restraint on public expenditure growth. For the year as a whole, a general government deficit of 3.1 % of GDP is expected. At unchanged policies, the deficit is expected to narrow to 2.4 % and 1.7 % of GDP in 2018 and 2019, respectively. The structural deficit is expected to narrow from 3.3% of GDP in 2016 to 3.1% of GDP in 2017 and then remain almost unchanged in the two subsequent years.

Inflation

Core inflation is expected to gradually increase. After negative growth in the harmonised index of consumer prices (HICP) in 2016, inflation rebounded strongly in the first half of 2017 due to the increase in oil prices. HICP inflation moderated in the second half of last year to an annual average of 2 % in 2017, and is expected to decline further in 2018 and 2019 on account of oil price developments. Core inflation should recover gradually over 2018 and 2019 as wages pick up and the output gap turns firmly positive.

|

Graph 1.3:Net lending / borrowing by sector

|

|

|

|

Source: AMECO

|

Labour market

The labour market situation continues to improve, supported by wage moderation and the labour market reforms implemented in previous years. Employment is expected to have expanded by 2.7 % in 2017. It is then projected to decelerate but remain robust at 2.1 % and 1.7 % this year and in 2019, respectively. The unemployment rate keeps decreasing, down to 16.6 % in Q4-2017 from 18.6 % one year earlier, and is expected to fall to about 14 % by 2019. The recovery in the labour market has also allowed for a reduction of disparities in GDP per head across Spanish regions (Box 1.6). After remaining subdued until 2017, nominal wage growth is expected to gradually increase in 2018 and 2019, as the cyclical slack in the economy narrows. Productivity is expected to grow only moderately, leading to modest increases in nominal unit labour costs (ULC) until 2019 (Graph 1.4). However, further cost competitiveness gains are expected, as ULC are projected to grow more slowly than in the rest of the euro area.

|

Graph 1.4:Analysis of unit labour costs (ULC)

|

|

|

|

Source: AMECO, European Commission

|

A high level of labour market segmentation and long-term unemployment act as a drag on potential growth. The youth unemployment rate has progressively decreased (from 53 % in 2014 to 37.5 % in Q4-2017), and so has the long-term unemployment rate (from 12.9 % in 2014 to 7.1 % in Q3-2017) (Graph 1.5). However, both rates continue to be among the highest in the EU, suggesting that unemployment has become entrenched at least for some among these groups. At the same time, the proportion of employees on temporary contracts relative to the total employment has continued to rise by 0.3 pps year-on-year up to 26.8 % in Q4-2017, and is amongst the largest in the EU. However, the share of open-ended contracts in net employment growth increased to 54 % on average in 2017, although the longer term impact on the overall share of temporary employment cannot be assessed yet.

Poverty, inequality and social inclusion

Though declining, the share of the population at risk of poverty or social exclusion remains high. The proportion of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion declined for the second consecutive year in 2016 (based on 2015 income ()), reaching 27.9 % of the total population, but it remains well above the 2008 level of 23.8 %. The decrease owes to a drop in severe material deprivation and in the share of people living in households with very low or low work intensity, which despite having improved, remains very high. The share of people at risk of monetary poverty remained stable in 2015 at 22 %, and much higher than the EU average. Flash estimates () indicate that for Spain no significant changes in this indicator are expected for the income year 2016. Although improving, challenges remain in the situation of children and young people as reflected by the high shares of early school leavers, young people not in employment, education, or training, and children in poverty. Work intensity is one of the most important drivers of poverty and inequality.

|

Graph 1.5:Activity, unemployment, long-term unemployment, youth unemployment, NEET

|

|

|

|

Source: Eurostat, LFS.

|

Income inequalities remain high and real income growth is lower than GDP growth. Since the recovery started, real gross household disposable income (between 2014 and 2017) has grown more slowly than GDP and social indicators point at various vulnerabilities. Income inequality, as measured by the income quintile ratio, registered a slight decline in 2016 (based on income from 2015), but continues to be one of the highest in the EU, as the richest 20 % share of the population earns about 6.6 times more income than the bottom 20 %. Inequality is mainly driven by a high unemployment rate, skills polarisation and labour market segmentation. It is especially high at the bottom of the income distribution. The redistributive power of the tax and benefits system is relatively low compared to other EU Member States. It reduces income inequality by only 34.6 %, as measured by comparing the Gini coefficients () of market income (i.e. before taxes and transfers) and disposable income (i.e. after taxes and transfers), below the EU average of 40%.

|

Box 1.6: Spain. Regional disparities in GDP per head

GDP per head is unevenly distributed across regions. Disparities in GDP per head in Spain fell steadily before the start of the 2008 global crisis, increased after 2008 and declined again slightly in 2015. Despite the post-2008 increase, regional disparities are lower than in Italy and France and broadly similar to those in Germany (Graph 1.6.1.a). (

I

) Especially for France, dispersion in GDP per capita as measured by the weighted coefficient of variation is driven by the capital region, which is richer and more populated than other regions.

The contribution of employment and productivity to disparities in GDP per head varies across countries. GDP per head is the product of output per worker (i.e., productivity) times the ratio of employment to total population (i.e., the employment rate), which can be broken down into the share of the working population, the activity rate and the share of the active population that is employed (which is inversely related to the unemployment rate). While productivity plays a big role in explaining disparities in GDP per head between regions in Germany, France and the Netherlands, the employment rate is more influential in Spain and Italy (Graph 1.6.1.b).

Differences in employment rates across Spanish regions are the main driver of disparities in GDP per head. The lower dispersion in GDP per capita in 2008 compared to 2000, as shown in Graph 1.6.1.a, is largely due to some regional convergence in the employment rate, and in particular the share of the active population that is employed. Similarly, the higher dispersion in GDP per capita after 2008 is attributable to the asymmetric impact of labour shedding across regions (Graph 1.6.2). The recovery in the labour market started in 2014 has led to the small decline of disparities in GDP per capita in Spain, which remain larger than in the pre-crisis period.

In most Spanish regions, productivity was relatively low and unemployment relatively high in 2014. Several regions in Spain recorded some of the lowest values for total factor productivity, with no region appearing in the group of high productivity regions (Graph 1.6.3). Even more strikingly, no region recorded a below-EU average unemployment rate. In addition, unemployment rates are highly dispersed across regions in Spain: the largest regional unemployment rate is more than twice the rate of the region with the lowest unemployment. Regional disparities in the labour market are mirrored by disparities in other welfare variables such as the share of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion.

|

|

|

|

Table 1.1:Key economic and financial indicators — Spain

|

|

|

|

Source: Eurostat and ECB as of 30 Jan 2018, where available; European Commission for forecast figures (Winter forecast 2018 for real GDP and HICP, Autumn forecast 2017 otherwise)

|

|

|

2.

Progress with country-specific recommendations

Progress with the implementation of the recommendations addressed to Spain in 2017 has to be seen in a longer term perspective since the introduction of the European Semester in 2011. Since then, Spain has overall advanced comparatively well in implementing CSRs. Looking at the multi-annual assessment of the implementation of the Country Specific Recommendations (CSRs) since these were first adopted, 42 % of all the CSRs addressed to Spain have seen 'some progress' in their implementation. On 35 %, Spain made 'substantial progress' or fully implemented them. 23 % of the CSRs recorded 'limited' or 'no progress' (see Graph 2.1). Reforms carried out during economically challenging times contributed to the Spanish economy's strong performance since its emergence from the crisis. The decisiveness and speed of implementation have however weakened somewhat since 2014. The current minority government seems to concentrate its political capital on few selected policy issues, as well as on preventing roll-back of earlier reforms. In several policy areas subject to CSRs, both the national and regional levels of government are involved in reform implementation. In those areas, coordination and accountability remain challenges for CSR implementation.

Recommendations concerning the financial sector, the insolvency framework and the long-term sustainability of public finances have been addressed to a large extent. The restructuring of banks that had received state aid is well advanced, and the successful resolution of Banco Popular in June 2017 reinforced confidence in the stability and resilience of the Spanish banking sector as a whole. The 2011 and 2013 pension reforms made public finances more sustainable in the long term. The fiscal framework has seen various improvements since 2012. The reform of the corporate and personal insolvency frameworks has facilitated private debt reduction and made company defaults less onerous.

In labour market and social policies, significant gaps remain despite substantial progress in earlier years. The labour market reforms carried out since 2012 have made employment creation more responsive to economic growth. Increased flexibility and continuing wage moderation has been aiding this development. Still, policy efforts to address the high segmentation in the labour market have remained limited and have not prevented the share of temporary contracts from increasing. Progress has also been less prominent in social policies, notably concerning income support schemes and family policies, and in education.

|

Graph 2.1:Overall multiannual implementation of 2011-2017 CSRs by February 2018

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|

Progress has been more muted in implementing product market reforms and improving research and innovation, also seen from a multi-annual perspective. Over the past few years, Spain has received recommendations to address regulatory fragmentation in its internal market and to strengthen research and innovation, a prerequisite for sustainable productivity growth. Although the law on market unity has been in force for four years, the adaptation of sectoral legislation to its principles has been slow. The renewed commitment of regions and the central government in January 2017 to strengthen cooperation on market unity has so far not translated into tangible results. No policy measures have been taken to reform size-contingent regulation or liberalise professional services, which had been the subject of previous years' CSRs. Both public support and promotion of private funding for research and innovation have seen only modest increases. There were only a few isolated advances in innovation governance and public-private cooperation in research and tertiary education, although some measures taken may need more time to generate measurable impact.

|

|

|

Table 2.1:Overall assessment of progress with 2017 CSRs

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|

|

|

Spain has made limited () progress in addressing the 2017 Country-specific Recommendations (see Table 2.1). In fiscal policy and governance (CSR 1), a new law on public procurement has been adopted which improves transparency and control mechanisms. Its effectiveness, in particular at regional and local level, will however depend on proper. While no legislative initiatives have been taken to strengthen the fiscal framework in 2017, the government has continued implementing the measures already set out in the law. An expenditure review, focusing on subsidies in several policy areas, was kicked off in 2017. Some progress has thus been made in implementing CSR 1, thereby also addressing aspects of the 2017 Council Recommendations for the Euro Area to ensure sustainable public finances.

In labour market, social and education policies (CSR 2), some regions have advanced towards better coordination between public employment and social services. Spain reinforced labour inspectorates to fight more effectively against the abuse of temporary contracts. Initial steps were taken to reduce the number of interim contracts in the public administration. Measures to promote open-ended contracts in the private sector, however, have shown limited effectiveness so far or have not yet moved to the implementation stage. The roll-out of the Universal Social Card in 2018 will make the receipt of social benefits more transparent, but will not necessarily improve the effectiveness of income guarantee schemes and family support across the country. Some measures to increase labour market relevance of tertiary education have been initiated or pursued further, but are still too recent to have a noticeable effect on outcomes. Efforts to improve educational outcomes have not reduced the persisting regional disparities. Some measures to strengthen teacher training and to support students, notably those at risk of leaving school early, were approved in 2017. Work in Parliament on the "National Pact for Education" had not resulted in decisions as of February 2018. Overall, progress on CSR 2 has been limited, implying few achievements on the Euro Area Recommendation to promote social fairness and convergence.

Innovation funding saw modest increases, but this has so far not led to increased investment in terms of GDP share. However, Spain took a number of steps towards making the governance of research and innovation more inclusive (CSR 3.1). There were few advances in the further implementation of the law on market unity. The consequences of the constitutional court rulings declaring some of its articles null and void remain to be seen (CSR 3.2). This results in limited progress on CSR 3, which also means few substantial achievements concerning the Euro Area Recommendation to prioritise reforms that increase productivity and improve the business and investment environment.

European Structural and Investment Funds are pivotal for addressing key challenges to inclusive growth and convergence in Spain. Among others, they support SME competitiveness, strengthening of digital skills and vocational training, and women's labour market participation. They are also instrumental for fostering investment in regions' relative strengths in the framework of smart specialisation and for reducing regional disparities in the medium term (see Box 2.2).

|

Box 2.2: Tangible results delivered through EU support to structural change in Spain

Spain is a beneficiary of significant European Structural and Investment Funds (ESI Funds) support and can receive up to EUR 39.8 billion until 2020. This represents around 1 % of GDP annually over the period 2014-2018 and 17 % of public investment. By 31 December 2017, an estimated EUR 11.7 billion (30 % of the total) had been allocated to projects on the ground. So far, this has paved the way for around 39 300 enterprises to receive support, of which more than 15 200 are start-ups. By the end of 2016 almost 1.6 million participations in European Social Fund (ESF)/Youth Employment Initiative (YEI) activities were recorded, from which close to 900 000 (55 %) involved unemployed people (including long-term unemployed). Some 44 000 participants gained a qualification upon leaving and 43 800 were in employment, including self-employment. EUR 1.7 billion from the total amount is to be delivered via financial instruments, a two-fold increase compared to the 2007-2013 period.

ESI Funds help address structural policy challenges and implement country-specific recommendations. Actions financed cover, among others, promoting private R&D and innovation capacity; improving the competitiveness of SMEs and their growth and internationalisation potential; the creation of new enterprises through financial and non-financial support; strengthening digital skills and improving the efficiency of the administration through the development of e-government; improving the effectiveness of the justice system; supporting womens' participation in the labour market particularly through developing childcare facilities; and strengthening the links between vocational training and the labour market. Funds are also contributing to better respond to jobseekers’ needs in activation and support the creation of sustainable and quality jobs promoting open-ended contracts. The funds are also used to support the fight against early school leaving and the upskilling of the older population, as well as to strengthen the links between vocational training and lifelong learning opportunities, in line with the Skills Agenda priorities.

Spain has already undertaken various reforms to fulfil the preconditions for ESI Funds support. Smart Specialisation Strategies for research and innovation were developed to concentrate investments on regions' relative strengths and foster specialisation on products with strong market potential. This has also improved cooperation between enterprises and public research institutions, and promoted the usage of evaluations of R&D support. The national and regional transport plans have allowed the timely preparation of projects, implemented not only with support from ESI Funds, but also from the Connecting Europe Facility (CEF), European Investment Bank (EIB) loans and national funding. Reform of public procurement will increase the efficiency of public spending. After a slow start, the YEI implementation has made significant progress in 2017. Spain is the largest recipient of this Initiative, and will receive EUR 418 million for 2017-2020 in addition to the EUR 943 million allocated for 2014-2015 to continue investing in the young people and ensure their sustainable integration in the labour market.

Spain is advancing the take up of the European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI). As of December 2017, overall financing volume of operations approved under EFSI amounted to EUR 5 billion, which is expected to trigger total private and public investment of EUR 30.8 billion. 54 projects involving Spain have been approved so far under the Infrastructure and Innovation Window (including 14 multi-country projects), amounting to EUR. 4.8 billion in EIB financing under EFSI. This is expected to trigger a total investment of about EUR 22.9 billion. Under the SME Window, 16 agreements with financial intermediaries have been approved so far. These amount to EUR 779 million financed by the European Investment Fund and enabled by EFSI, which is expected to mobilise around EUR 8.9 billion in total investment. Some 96 500 smaller companies or start-ups will benefit from this support.

Funding under Horizon 2020, the Connecting Europe Facility and other directly managed EU funds is additional to the ESI Funds. By the end of 2017, Spain had signed agreements for EUR 976 million for projects under the Connecting Europe Facility. From 2014-2016 Spain has been the 4th beneficiary of Horizon 2020 with a share of 8.8% of the total Horizon 2020 EU contribution.

https://cohesiondata.ec.europa.eu/countries/ES

|

3.

Summary of the main findings from the Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure In-Depth Review

3.1.Introduction

The in-depth review for the Spanish economy is presented in this report. In spring 2017, Spain was identified as having macroeconomic imbalances, in particular relating to high levels of external and internal debt, both public and private, in a context of high unemployment. The 2018 Alert Mechanism Report (European Commission, 2017i) concluded that a new in-depth review should be undertaken for Spain to assess developments relating to the identified imbalances. Analyses relevant for the in-depth review can be found in the following sections: Public finances (Section 4.1.1); Financial sector and private sector debt (Sections 4.2.1 and 4.2.3); Labour market (Section 4.3.1); and Investment (Section 4.4). Potential spillovers to the rest of the euro area are discussed in Box 3.4.1.

3.2.Imbalances and their gravity

Spain's net international investment position (NIIP) remains very negative. The large stock of net external liabilities (-83.2 % of GDP in Q3-2017) leaves the country exposed to adverse shocks or shifts in market confidence. Favourable changes in their composition somewhat mitigate the associated vulnerabilities.

Despite a significant reduction, private sector indebtedness is still well above prudential and fundamental-based levels. Private sector debt, in non-consolidated terms, amounted to 159.9 % of GDP in Q3-2017 (of which 61.8 % of GDP was household debt and 98.1 % of GDP non-financial corporate debt). A high level of debt increases vulnerability to interest rate shocks, and its associated financial burden constrains domestic demand. The financial position of Spanish households has strengthened thanks to improvements in the labour market and lower income taxes. Furthermore, the financial burden of household debt has been reduced by the prevailing low interest rates. With sustained GDP growth, household debt reduction is likely to continue, but prudential and fundamental-based benchmarks show that household debt remains high and deleveraging needs persist (see Section 4.2.3). On the corporate side, the debt reduction process has taken place simultaneously with new credit flowing towards the less indebted and most productive firms, supporting investment (Banco de España, 2017d). Despite its significant decline, the outstanding debt of non-financial corporations remains above what prudential and fundamentals-based benchmarks warrant (see Section 4.2.3).

The general government debt ratio is expected to have decreased slightly further in 2017, albeit remaining at a very high level. The Commission 2017 autumn forecast projects a decrease by 0.6 percentage points (pps) in 2017, to 98.4 % of GDP. Despite this downward trend, the high stock of public debt continues to be a vulnerability in the face of potential changes in market sentiment and the prevailing low interest rate environment.

Unemployment, though still very high, has continued its rapid decline. Unemployment is estimated at 17.2 % for the whole of 2017 and is forecast to decline to 15.6 % in 2018. This constitutes a fall of more than 10 pps since its peak in 2013. Long-term and, especially, youth unemployment saw a similarly steep fall during this period, but more than one third of the active population under 25 years of age did still not have a job in Q4-2017. 34% of the increase in employment between Q4-2016 and Q4-2017 has taken the form of temporary contracts. This increase is however lower than the increase in the share of permanent contracts.

The relatively large size and economic integration of the Spanish economy with the rest of the EU make it a potentially significant source of spill-overs to other member states, especially those with which Spain has significant trade, financial and/or banking linkages. Box 3.4.1 illustrates how structural reform measures in Spain can carry both a positive domestic and cross border effect. The simulations presented therein follow the spirit of the 2017 Council Recommendations for the Euro Area, in particular as regards increasing productivity and potential growth, and improving the institutional and business environment.

3.3.Evolution, prospects, and policy responses

The persistent current account surplus is increasingly driven by structural factors. Despite the key role of domestic demand in driving the economic recovery, Spain has been recording a current account surplus since 2013. Also, between 2013 and 2017, Spain's net lending capacity has remained relatively stable at almost 2 % of GDP, despite the shrinking output gap. Initially, cyclical and transitory factors (such as low oil prices or low interest rates) drove the improvement in the current account balance, but, more recently, structural factors are playing an important role in preserving the improved external position. Accordingly, in cyclically adjusted terms, the current account balance has continued to improve (see Graph 3.1), exceeding the level suggested by current account norms, that is, the one explained by fundamentals (close to 0.4 % of GDP in 2017) (). Export market share increases and signs of import substitution (whereby foreign imports are replaced with domestic production), confirm the perception that a structural change has taken place in the Spanish economy (see Box 4.4.1).

Current account surpluses are slowly translating into a reduction of Spain's net debtor international investment position. Complemented by high nominal GDP growth, the surpluses are driving a slow but steady reduction of Spain's negative NIIP (see Graph 3.2) (). Negative valuation effects prevented a larger improvement in 2013 and 2014, and again in 2017 with the appreciation of the euro. Continued current account surpluses and high nominal GDP growth projected until 2019 are expected to facilitate a further improvement of the NIIP.

|

Graph 3.1:Current account balance and net international investment position

|

|

|

|

Source: Eurostat.

|

The change in the composition of Spain's external liabilities in terms of asset type helps to mitigate the vulnerability risks. Since 2013 the proportion of equity instruments in total external liabilities has been increasing, although from a very low level. Equity does not carry the same risks as debt for external sustainability, as its remuneration, i.e. dividend payments, can be adjusted during economic downturns. The change in the composition of external indebtedness towards public and central bank liabilities, with generally lower refinancing and liquidity risk, also mitigates to some extent the external vulnerability of the Spanish economy (see Graph 3.3). Additionally, most of the external debt has maturities of one year or more (about 74 % of general government and private sector external debt, excluding intercompany loans).

Spain would need to maintain current account surpluses over a sustained period of time to decisively improve its still large external liabilities. While the current account surpluses recorded since 2013 have put the NIIP onto a declining path, the amount of Spain's net external liabilities is still far from having achieved a level that could be considered prudential or in line with fundamentals. This gap warrants further and sustained adjustments (see Graph 3.2) (). Even under a relatively benign growth scenario, maintaining current account surpluses over a long period of time would be required to decisively bring down the large NIIP (see Table 3.1). It is therefore crucial for Spain to pursue fiscal consolidation and preserve the competitiveness gains made in the past years. While the latter have so far been largely driven by wage restraint, advances based on productivity growth and non-cost competitiveness more generally continue to pose a challenge.

|

Graph 3.2:Analysis of the rate of change of NIIP — Spain

|

|

|

|

Source: Eurostat

|

Private sector deleveraging is increasingly driven by GDP growth as new credit continues to grow. Private sector debt has been reduced by about 58 pps of GDP since its peak in 2010. Most of this reduction is due to a decline in corporate debt (about 35 pps of GDP), but progress in household debt reduction (over 23 pps of GDP) has also been significant. Even so, deleveraging needs remain for both households and companies, as debt of both institutional sectors remains above their estimated prudential and fundamentals-based levels (see Section 4.2.3). Thanks to the robust nominal GDP growth, the private debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to continue decreasing, even as bank lending resumes. Indeed, although the outstanding volume of credit to the private sector continues to shrink, new bank lending to households and to the most productive and/or less indebted firms continues to increase, underpinning Spain's strong economic growth (Banco de España, 2017d).

|

Graph 3.3:External liabilities by sector-type of financial assets: change 2013-2017

|

|

|

|

Source: Eurostat, own calculations.

|

In 2017, the quality of bank assets improved further. The stock of non-performing loans went down further to 8.1 % as of November 2017, and is now close to the euro area average. On aggregate, the banking system comfortably meets the regulatory capital requirements. The resolution of Banco Popular on 7 June 2017 has strengthened the Spanish banking sector at large, with no losses for taxpayers and depositors.

After the sharp adjustment that largely prompted the financial sector crises, the housing market and construction sector have consolidated their recovery. Housing prices have risen for almost four years in a row. However, there remains a large stock of unsold houses, notably in some regions, and the recovery does not show potentially harmful price dynamics (Philiponnet and Turrini, 2017). The development of the real estate market remains crucial for banks’ profitability.

The insolvency reforms over the past years have facilitated private debt reduction. The use of pre-insolvency proceedings has increased by about 50 % and out-of-court agreements have become common for natural persons. The overall number of insolvency proceedings has started to increase in the first two quarters of 2017, by 3.9 % and 4.3 % quarter-on-quarter, respectively. In the prevailing context of high economic growth and improving access to finance, such figures indicate that insolvency procedures have become more conducive to deleveraging (see Section 4.2.2).

The reduction of public sector debt is expected to gather pace. Despite strong nominal GDP growth and debt-decreasing stock-flow adjustments in 2015 and 2016, the decline in the debt ratio has been muted, totalling 1.4% of GDP between 2014 and 2016. This is due to the still high, though declining, general government deficit. Since 2014, the reduction of the deficit has relied to a large extent on the positive macroeconomic outlook and the improving financing conditions. As the deficit is forecast to continue narrowing in 2017 and 2018 (to 3.1 % and 2.4 % of GDP, respectively) thanks to the continuation of the economic upswing as well as some expenditure restraint, the debt ratio is forecast to decrease further to just below 97 % of GDP in 2018. While there appears to be no immediate risk of fiscal stress, risks to fiscal sustainability remain significant in the medium term (see Section 4.1.1).

The labour market has continued to improve, but unemployment and segmentation remain high. Strong job creation has continued throughout 2017, and is expected to slow down but remain robust through 2019. Employment growth has been underpinned by wage moderation and the labour market reforms implemented in 2010-2012. However, it still occurs to a large extent through temporary contracts, the proportion of which in total employment is significantly higher than the EU average, and has increased further throughout 2017 (to 26.8% in Q4-2017). This has a potential negative impact on productivity growth and social cohesion. Spain is taking measures to strengthen individual support to the long-term unemployed, but their impact relies on the capacity of the regional public employment services. This has remained limited despite increases in resources and improved coordination with social services in some regions (see Section 4.3.1). Addressing education and skills gaps is critical to reducing structural unemployment and supporting the reallocation of human resources towards more productive activities.

|

|

|

Table 3.1:Current account balance and net international investment position sensitivity analysis

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission's calculations

|

|

|

3.4.Overall assessment

The reduction of macroeconomic imbalances in Spain has progressed further, but the still high stocks of external, public and private debt mean that significant vulnerabilities remain. Private sector debt reduction has continued to advance, and the slower debt reduction pace in 2017 is due to credit flows turning positive. Public sector debt has been slightly reduced, a process that is expected to accelerate somewhat as government deficits are forecast to narrow further. Improvements in the external balance are increasingly sustained by structural factors supporting the growth of exports and limiting that of imports. Nevertheless, in order to decisively bring down its stock of external liabilities, Spain will have to record current account surpluses over an extended period of time. Although unemployment has been declining rapidly, it remains very high with a large proportion of it being long-term, and the share of temporary employment remains high.

|

|

|

Table 3.2:MIP Matrix

|

|

|

|

|

|

(Continued on the next page)

|

|

Table (continued)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|

|

|

|

Box 3.4.1: Euro area spillovers

Given its economy's relatively large size, structural reforms in Spain could have spill-over effects on other euro area countries. CSRs to improve the business environment by implementing product market reforms have been addressed to Spain since 2011. This box illustrates the potential spill-over effects from the full implementation of the Law on Market Unity (LMU), aimed at reducing regulatory disparities across regions in Spain, and of a liberalisation of professional services. Both supply-side reforms are expected to lead to a more efficient reallocation of resources and to boost competitiveness gains in Spain. Using the Commission's QUEST model (

II

), the impact of reforms in Spain on real GDP in Spain and other euro area countries is simulated (see Graph 3.4.1). Monetary policy rates in the euro area are assumed to remain unchanged during the first two years.

Under the scenario of full LMU implementation (

III

), the administrative burden on Spanish firms declines, making them more competitive, both in domestic and in foreign markets. As a result, the Spanish real GDP after 5 years is about 2 % higher than in the baseline scenario. The impact on real GDP of other euro area countries is a fraction of the former, but persists over the simulation period. The effect is larger in countries with strong economic ties to Spain, such as France.

Liberalising professional services also yields a positive, albeit smaller, impact on Spanish real GDP. This scenario assumes that the Spanish product market regulation (PMR) indicator in professional services approaches the values of the best performers in the EU (

IV

). This reform, by improving competitiveness in product markets, leads to a slow and modest increase in Spanish real GDP of about 0.24 % after 10 years. The impact on real GDP of other euro area countries is limited, but positive.

In addition, the two reforms may have a positive impact on economic agent's confidence, which is captured by adding a positive confidence shock to the model. Positive confidence effects that lead to a strengthening of private-sector demand can amplify the positive spillovers to other euro area economies. The confidence shock is simulated as a reduction of the sovereign-debt spread between Spain and Germany (currently at about 100 basis points) to zero, of which 50 % is passed on to firm lending rates (assumption based on Zoli, 2013). This improvement in financial conditions boosts Spanish investment and increases real GDP by about 0.6 % after 10 years. The spill-over effect on other euro area countries' real GDP is greater but still limited.

|

4.

Reform priorities

4.1.

Public finances and taxation

4.1.1.General government debt *

Spainʼs general government debt ratio remains high. After rising sharply in the years following the financial crisis, the general government debt ratio peaked at slightly over 100 % of GDP in 2014, about 65 pps above its low point of 2007. The Commission 2017 autumn forecast projects that the debt ratio will decrease from 98.4 % of GDP in 2017 to 95.5 % of GDP in 2019, as relatively strong nominal GDP growth increasingly offsets the narrowing deficits. As the private debt ratio has declined faster than the government debt ratio, general government debt now makes up a much larger share of the total indebtedness of the economy – at around 37 % in 2016 relative to around 20 % in 2010, the year in which private debt peaked (See Graph 4.2.3).

Spain does not appear to face immediate risks of ʻfiscal stressʼ. () This is thanks to the improved macro-financial situation, while the short-term challenges from the fiscal side are not sufficiently severe to generate short-term fiscal stress at the aggregate level. In particular, Spain still has a sizeable negative net international investment position and low household savings rate. However, risks are mitigated by the strong real GDP growth, positive current account balance and regained cost competitiveness, as well as the low proportion of short-term debt among non-financial corporations and households and subdued private sector credit flow. Short-term risks stemming from the fiscal side are larger and are mainly related to the high general government debt ratio and relatively high gross financing needs. These elements are mitigated by an improved headline balance, a relatively low share of short-term debt (as % of GDP), a low interest/growth rate difference and subdued government expenditure growth.

Spain faces high fiscal sustainability risks in the medium term. Debt sustainability analysis shows that under normal economic conditions and assuming a constant structural primary balance after the last Commission forecast year (2019), the Spanish general government debt is expected to remain at around 95 % of GDP by 2028 (last projection year). This projection is driven by the gradual improvement in the primary balance over the projection period offsetting an increasing interest rate-growth differential, especially in the last part of the period. The analysis also shows that the level of the debt ratio is highly sensitive to shocks (see Box 4.1.1). Furthermore, Spainʼs structural primary balance would need to improve by as much as 5.3 % of GDP in cumulative terms over a five-year period (from 2019 until 2024) relative to the baseline no-fiscal policy change scenario to reach the 60 % public debt-to-GDP ratio reference value by 2032. In the Commission's assessment of debt sustainability, this increase is well above the threshold that qualifies a country as facing high risks in the medium term.

In the longer term, risks to fiscal sustainability due to the unfavourable initial budgetary position are mitigated by savings in age-related expenditure. Savings on non-health ageing related spending (pensions and unemployment benefits) amount to about 2.4 % of GDP, due to the 2011 and 2013 pension reforms and other factors. By contrast, public expenditure on health care and long-term care adds 1.5 % of GDP to the fiscal sustainability gap. This projection is based on current expenditure trends and the expected demographic changes.

The persistent deficit of the social security system and the continued application of the minimum pension revaluation rate are receiving policy attention. While two successive reforms of the pension system, in 2011 and 2013, will help contain pension expenditure in the long term, they are also likely to result in less generous pensions. The parliamentary committee dedicated to pension issues held meetings in 2017 to discuss possible further reforms. To date, these have not led to a consensus. For a summary of the current situation and remaining challenges, see Box 4.1.2.

|

Box 4.1.1: Medium-term projections of general government debt

The public debt trajectory has been simulated under different scenarios. Under the baseline scenario, the general government debt is forecast to decrease slightly during the projection period to reach about 95.1 % of GDP in 2028 (the end of the projection horizon). The baseline has been derived from the Commission’s 2017 autumn forecast, consistent with the forecast implicit interest rate and the shares of short-term and long-term public debt. It makes a number of technical assumptions. First, over the post-forecast period, the structural primary balance is set constant at the value projected for 2019. The cyclical component of the primary balance is calculated using (country-specific) budget balance sensitivities over the period until output gap closure is assumed (2022). Second, the long-term interest rate on new and rolled-over debt is assumed to be 3 % in real terms by the end of the projection period, while the short-term real interest rate reaches an end-of-projection value that is consistent with the 3 % long-term real interest rate and the value of the euro area yield curve. Third, the GDP deflator is assumed to change linearly until it reaches 2 % in 2022 and remain constant thereafter. Fourth, the stock-flow adjustment is set to zero after 2019. Finally, medium-term real GDP growth projections are based on the T+10 methodology agreed with the Economic Policy Committee and implies that medium-term real GDP growth is assumed to average 1.5 % in 2017-2022 and to slow to 1.2 % on average in 2023-2028.

More favourable assumptions on real growth would lead the debt ratio to follow a lower path to reach 90. % of GDP in 2028. By contrast, under more unfavourable assumptions on real GDP growth or interest rates, the debt ratio would increase to 100.5. % of GDP or 101.4. % of GDP by 2028, respectively.

|

|

Box 4.1.2: The Spanish pension system — reforms and challenges

The continuing large deficit in the social security sector balance and the gradual erosion of the Social Security Reserve Fund built up with surpluses of the social security system during the boom years have prompted a debate about the need to further reform the pension system in Spain, following the two substantial reforms of 2011 and 2013. Since October 2016, the parliamentary committee dealing with pension reform has held discussions about a new set of recommendations (the so called "Toledo Pact" process), but the committee has still not reached a conclusion.

Spain's Social Security System has moved from a position of comfortable surpluses in the years preceding the financial crisis to widening deficits, with the latter reaching 1.6 % of GDP in 2016. This is the result of nominal GDP stagnating and contributory pension expenditures, in particular, continuing to grow due to demographic factors and a rising average pension. In the face of deteriorating fundamentals, Spain undertook two major reforms (adopted in 2011 and 2013, respectively) to improve the fiscal sustainability of the pension system. The 2011 reform aimed to restrict access to pensions by gradually increasing the legal pensionable age and reduce the generosity of pensions. The 2013 reform introduced a mechanism adapting the level of the initial pension to the evolution of life expectancy at the time of retirement (the ʻsustainability factorʼ) and a mechanism called the pension revaluation index (PRI), which aims to adapt the expenditure of the pension system so as to ensure its long-term sustainability. This is achieved by, within certain limits, setting the annual revaluation of existing pensions at such a level so as to gradually bring expenditure in line with revenue. Hence, if the system is in deficit, the PRI acts by gradually reducing the generosity of existing pensions. As a result, the sustainability of the pension system in its current form is virtually ensured by design as long as its various mechanisms are allowed to work as intended.

Despite the minimum 0.25% revaluation having been applied for the last four years, the subdued inflation has so far implied that the real value of pensions has not been eroded. However, as inflation has picked up in 2017, this may no longer be the case and continued application of the minimum revaluation may lead to a gradual decline in the real value of existing pensions.

Based on a number of demographic and economic assumptions and including the impact of the two reforms, the European Commission 2015 Ageing Report projects public pension expenditure to be 0.8 % of GDP lower in 2060 compared to its 2013 level. The ratio is first expected to rise from 11.8 % of GDP in 2013 to 12.5 % of GDP in 2045 as the retiring baby boom generation is driving up the dependency ratio, and then, to come down to 11 % of GDP by 2060, as this baby boom effect fades out. In this baseline scenario, the benefit ratio - i.e. average public pensions in relation to average wages - declines by about 20 pps to around 40 % by 2060, generating savings amounting to 4.4 % of GDP. A further 0.6 % of GDP is saved by changes to the coverage ratio, i.e. who is eligible for a pension. Reflecting the same process, the replacement rate (i.e. the average first public pension as a share of the average wage at retirement) is also expected to fall by over 30 pps to slightly below 50 %. These reductions are among the largest in the EU, with a potential strong negative impact on the living standards of the elderly Spanish population, although Spain would still have benefit and replacement ratios around the EU average level in 2060

V

. The most recent projections for Spain confirm that, due to a large fall in the benefit ratio, pension expenditure will remain contained relative to the euro area and the EU (DG Economic and Financial Affairs, 2018).

The adequacy of future pensions will also crucially depend on the capacity to address current labour market challenges, such as the widespread use of temporary contracts (and especially those shorter than 3 months), the incidence of part-time employment (in particular involuntary part-time employment), the incidence of short professional careers, especially among women (

VI

), and the need to improve working conditions and adapt the work place to allow for longer working life.

|

4.1.2.Taxation

Spain has a relatively low tax-to-GDP ratio and relies less on labour taxes than other EU countries. In 2016, Spainʼs tax burden accounted for 33.3 % of GDP, compared to an EU average of about 38.9 % and euro area average of 40.1 %. Spain raises roughly equal shares of revenues from indirect taxes, direct taxes and social contributions. Following a steep fall during the crisis (from 12.4 % of GDP in 2006 to 8.7 % in 2009), the share of indirect taxes has largely recovered (to 11.8% of GDP in 2016) as a result of higher VAT rates, improved VAT compliance and the economic recovery. Personal income taxes and social contributions have seen more limited changes, while corporate income taxes have varied significantly with the cycle and were still much below their pre-crisis level as a share of GDP. In 2015 and 2016, both personal and corporate income taxes were affected by legislated tax cuts. Some of the reduction of the corporate income tax was reversed in 2017, as the corporate tax base was broadened by reducing the deductibility of some items. In 2015, the implicit tax rate on labour stood at 31.3 %, below the EU average of 35.9 %, and the tax wedge () in 2016 for an average single wage earner was 39.5 % compared to an EU average of 40.6 %. Employersʼ social contributions make up a relatively large part of the tax burden, particularly at low wage levels, resulting in a less progressive system.

Despite a standard VAT rate in line with the EU average (21 % vs EU average of 21.6 %), Spain has a relatively large VAT policy gap. The 'actionable policy gap' – the policy gap remaining after excluding those items where charging VAT would be either impractical or is beyond the control of national authorities ‒ stood at 27 % in 2015, of which just over half was due to the use of reduced and super-reduced rates. Simulations conducted by the European Commission based on the EUROMOD model (See Box 4.1.2 in the 2017 Country Report) show that reducing the incidence of these reduced rates would increase revenues by 0.2-1.4 % of GDP, depending on the scope and extent of the reduction. Negative distributional effects can be reduced or avoided by giving priority to items where the reduced rate has a regressive effect or be compensated through other means, such as social transfers.

In some cases, reduced VAT rates tend to have a regressive impact. All VAT rate reductions potentially benefit all consumers regardless of their income level. As such they are not an effective tool for income redistribution. While, on average, the reduced rates in Spain have some progressive effect, which is almost entirely due to foodstuff, for many items they have a strongly regressive effect. For instance, this is the case of the reduced rate for restaurants and hotels.

The VAT compliance gap continued to decrease. The gap – calculated as the difference between the theoretical VAT liability and the revenue actually received as a percent of the former – amounted to 3.5 % in 2015 (down from a peak of 13 % in 2011), which is significantly below the EU average of 13 %. In July 2017, Spain put in place a new information system (SII) that requires medium and large enterprises to inform the tax administration about their commercial transactions with a much shorter delay.

Environmental taxes are still below the EU average, despite increases in recent years. Environmental taxes in Spain amounted to about 1.9 % of GDP in 2016, compared to an EU average of about 2.4 % of GDP. In particular, energy taxes (including transport fuel taxes) yielded little revenue, which reflects the low level of excise duties on both unleaded petrol and diesel. This is particularly the case for diesel, on which Spain applies the minimum excise duty, despite diesel having a higher carbon and energy content than unleaded petrol. Finally, taxes on transport, such as vehicle taxes, only yield half as much revenue in Spain as the EU average (0.2 % compared with 0.5 % of GDP).

Spain relies to a relatively low extent on recurrent taxes in the area of property taxation. While revenues from property taxation in Spain are slightly above the EU average (2.8 % compared with 2.6 % of GDP in 2015), the recurrent element is below the EU average (1.3 % of GDP compared with 1.6 % in 2015), while transaction taxes exceed the EU average (1.6 % compared with 1 % of GDP). Recurrent property taxes are considered among the taxes least detrimental to growth and preferable to transaction taxes, as the former allow a more efficient allocation of assets and higher labour mobility. No major policy changes have been introduced in the area of property taxation in recent years, except for the gradual phasing out of mortgage deductibility.

|

Graph 4.1.3:Government revenue by category

|

|

|

|

Source: Ameco.

|

The Spanish tax system features elements hindering investment. A high debt bias hampers developments in equity markets (see Box 4.4.1 in the 2017 Country Report). The difference in the cost of capital for new equity-funded investment, on the one hand, and debt-funded investment, on the other, was still one of the largest in the EU in 2016, despite having improved somewhat.

4.1.3.FISCAL FRAMEWORK

Spain’s fiscal framework sets out the obligation for subnational governments to comply every year with a deficit, debt and expenditure rule target. At regional level, compliance with fiscal targets improved considerably in 2016 (Graph 4.1.4). Over 2013-2016, the debt target was met most frequently, followed by the expenditure rule target. However, deficit targets have had the worst compliance record, even though the regional public deficit has gone down over 2013-2016 (Graph 4.1.4 left-hand side). Nevertheless, in 2016 nine regions complied with the deficit target, the highest number since 2013. Over 2013-2016, fiscal rules were in general more frequently observed by regions falling within the medium GDP per head groups (Graph 4.1.4).

|

Graph 4.1.4:Share of regions having complied with fiscal rules over 2013-2016 by GDP per head and by year (100% = 17 regions)

|

|

|

|

Source: Ministry of Finance and European Commission

|