EUROPEAN COMMISSION

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Brussels, 10.5.2017

SWD(2017) 154 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

Accompanying the document

Report from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament

Final report on the E-commerce Sector Inquiry

{COM(2017) 229 final}

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

Accompanying the document

Report from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament

Final report on the E-commerce Sector Inquiry

Table of Contents

A. INTRODUCTION

1. The wider context: The Digital Single Market strategy

2. The reasons for launching the sector inquiry

3. The purpose of the sector inquiry

4. The main steps of the sector inquiry

5. Analytical framework

6. Selection of addressees: goods

6.1 Selection of retailers

6.2 Selection of manufacturers

6.3 Selection of marketplaces, price comparison tools and payment system providers

6.4 Responses received

7. Selection of addressees: digital content

7.1 Selection of digital content providers (retail markets)

7.2 Selection of right holders (wholesale markets)

B. E-COMMERCE IN GOODS

1. Characteristics of respondents

1.1 Retailers

1.2 Manufacturers

1.3 Marketplaces

1.4 Price comparison tools

1.5 Payment service providers

2. Main features of competition in e-commerce in goods

2.1 The concentration of manufacturers and retailers in the sectors covered by the sector inquiry

2.2 Main parameters of competition

2.3 Pricing

2.4 Differences between online and offline offers

3. Distribution strategies

3.1 Distribution strategies of manufacturers

3.1.1 Sales channels

3.1.2 Trends in manufacturers' distribution strategies

3.2 Distribution strategies of retailers

3.3 Different types of distribution agreements used

3.3.1 Territorial exclusive distribution agreements

3.3.1.1 Prevalence of territorial exclusive distribution

3.3.1.2 Reasons for using territorial exclusive distribution agreements

3.4.3 Selective distribution

3.4.3.1 Overview and development of selective distribution

3.4.3.2 The reasons for opting for selective distribution

3.4.3.3 The selection criteria

3.4.3.4 Pure online players in selective distribution

3.4.3.5 General considerations on selective distribution

3.4.4 Agency agreements

4. Restrictions to sell and advertise online

4.1 Motivations for restrictions

4.1.1 Product quality, brand image and price

4.1.2 Customer services, promotion and advertising

4.1.2.1 Types of customer services

4.1.2.2 Financing of customer services

4.1.2.3 Promotion and advertising

4.1.3 Customers' purchasing behaviour and free-riding between the online and offline retail channel

4.2 Overview of restrictions

4.3 Cross-border e-commerce and geographic restrictions to sell and advertise online

4.3.1 Geographic sales strategies of manufacturers

4.3.2 Geographic sales strategies of retailers and cross-border e-commerce

4.3.2.1 Retailers not selling cross-border

4.3.2.2 Cross-border visits and transactions on retailers’ own websites

4.3.2.3 The role of online marketplaces for cross-border sales

4.3.2.4 The role of price comparison tools for cross-border sales

4.3.2.5 Geo-blocking measures

4.3.2.6 Geo-filtering and cross-border price and offer differences

4.3.2.7 Commercial reasons for not selling cross-border and costs of supplying abroad

4.3.3 Contractual territorial restrictions to sell and/or advertise online

4.3.3.1 Agreements between manufacturers and retailers restricting cross-border online sales

4.3.3.2 Monitoring of customer location

4.3.3.3 Geo-blocking measures, territorial restrictions and the EU competition rules

4.3.3.4 Indications of contractual territorial restrictions

4.4 Restrictions to sell on online marketplaces

4.4.1 Importance of marketplaces as a sales channel for retailers

4.4.2 Impact of sales through marketplaces on the business of manufacturers

4.4.3 Prevalence and characteristics of marketplace restrictions

4.4.4 Reasons put forward for marketplace restrictions by manufacturers

4.4.5 Reasons for marketplace restrictions reported mainly by retailers and some marketplaces

4.4.6 Possibilities offered by marketplaces to address quality requirements

4.4.7. Notice and take down procedures on marketplaces

4.4.8 Marketplace restrictions under EU competition rules

4.5 The use of price comparison tools and restrictions on the use of price comparison tools

4.5.1 Usage of price comparison tools by retailers

4.5.2 Restrictions on the use of price comparison tools

4.5.3 Reasons put forward for restrictions to use price comparison tools

4.5.4 Restrictions on the use of price comparison tools under EU competition rules

4.6 Pricing restrictions

4.6.1 Price setting at retail level

4.6.2 Monitoring of recommended retail prices

4.6.3 Retailers' compliance with price indications and reasons

4.6.4 Pricing restrictions under EU competition rules

4.6.5 Charging different wholesale prices for different sales channels

4.6.6 Online price transparency and the use of price monitoring software

4.7 Exclusivity and parity agreements ("MFN" clauses) between retailers and marketplaces and/or price comparison tools

4.7.1 Agreements between retailers and marketplaces

4.7.2 Agreements between retailers and price comparison tools

4.8 Other types of restrictions to sell or advertise online

5. Other observations

5.1 Data

5.1.1 Data collected by marketplaces and price comparison tools

5.1.2. Data collected by retailers

5.1.3 The use of data in e-commerce and potential competition concerns

C. E-COMMERCE IN DIGITAL CONTENT

1. Characteristics of respondents

1.1 Digital content providers

1.1.1 Types of operators

1.1.2 Business models

1.1.3 Size of activities

1.1.4 Revenue breakdown and advertising revenues

1.2 Right holders

1.2.1 Types of right holders

1.2.2 Size of activities of right holders

1.3 Types of content

2. Market trends and licensing practices

2.1 Market trends in the provision of online digital content services

2.2. Licensing practices

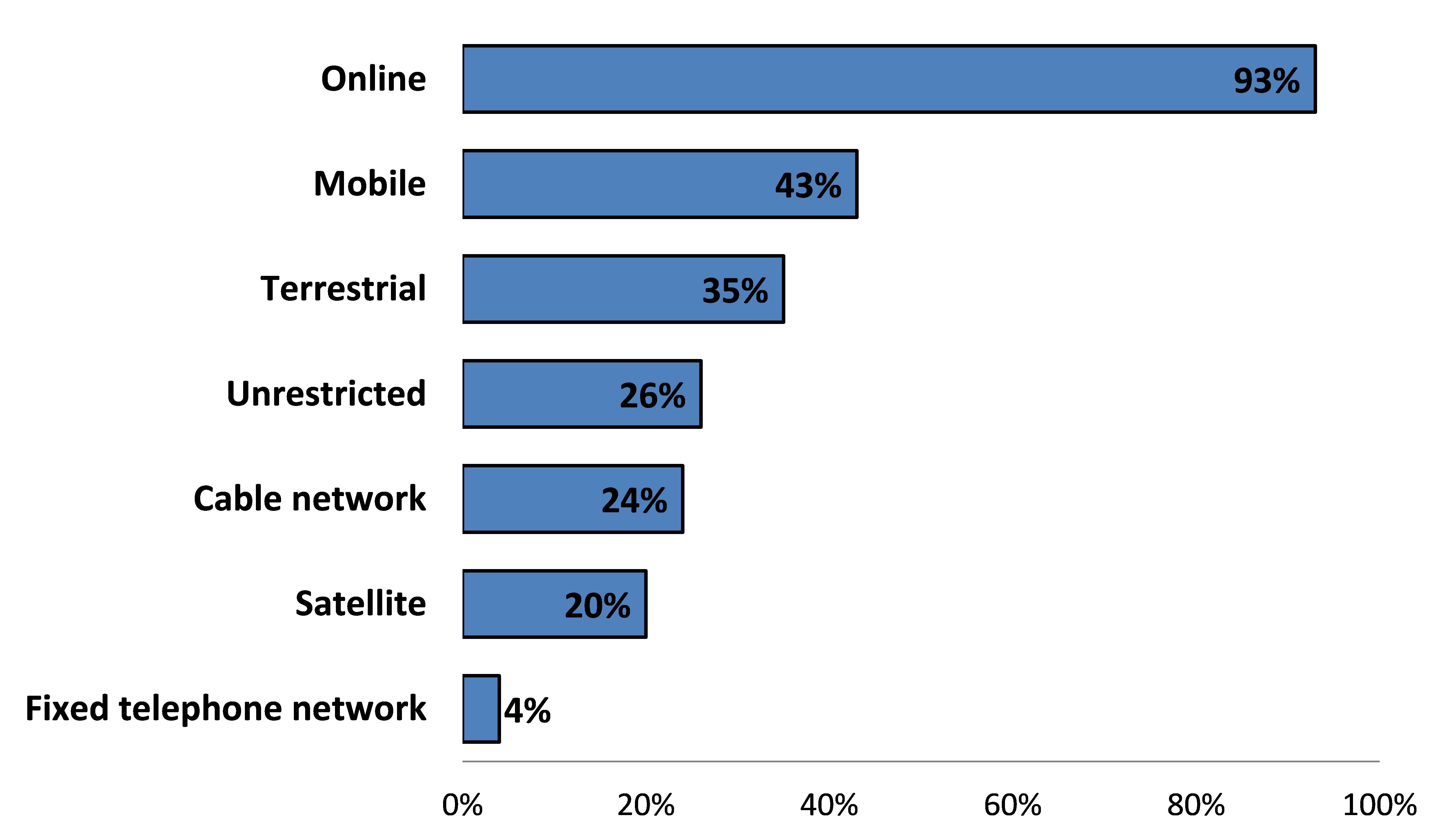

3. The scope of licensed rights: technologies

3.1 Definitions and data set

3.2. The scope of reception technology rights

3.3 The scope of ancillary and usage rights

3.4 Exclusive technology rights

3.5 Bundling of rights

3.5.1 Prevalence of bundling of rights

3.5.2 Bundling of rights

4. The scope of licensed rights: territories

4.1 Introduction

4.2 The territorial scope of online rights

4.2.1 The territorial scope of online rights in relation to different types of digital content

4.2.2 The territorial scope of online rights in relation to different types of digital content providers

4.2.3 The territorial scope of online rights in relation to the different business models used by digital content providers

4.3 Exclusive territorial rights

4.4 Reasons for non-availability of content across borders

4.5 Catalogue differences

4.6 Reasons for catalogue differences

4.7 Reasons provided by right holders why online rights are not licensed for certain territories

4.8 Geo-blocking of digital content services

4.8.1 Existence and extent of geo-blocking

4.8.2 Geo-blocking required by licensing agreements

4.8.3 Geo-blocking measures used to restrict cross-border access and portability

4.8.4 Restrictions on access and use in the terms of service for users

4.8.4.1 Unilateral restrictions on access and use in the terms of service for users

4.8.4.2 Contractual restrictions on access and use in the terms of service for users

4.9 Contractual provisions concerning monitoring, sanctions and compensation in relation to geo-blocking

4.9.1 Monitoring provisions

4.9.2 Sanctions and compensation for non-compliance with territorial and geo-blocking clauses

4.10 Use of VPN and IP routing services

5. The Scope of licensed rights: Release windows

6. Exclusive rights in content in licensing agreements between right holders and digital content providers

7. Duration of licensing agreements and contractual relationships

7.1 Duration of on-going licensing agreements

7.2 First time agreements

7.3 Length of the existing contractual relationships

7.4 Renewal clauses and rights of first refusal

7.4.1 Right of first refusal

7.4.2 Renewal clauses

7.5 Matching offer rights

8. Payment structures in digital content licensing agreements

8.1 Definitions and data set

8.2 Payment structures for online rights: Overall, by product type and by type of operator

8.3 Payment structures: combinations of specific payment mechanisms

8.4 Level of payments

9. Financing of digital content products

D. Key findings

1. Key Findings: Goods

1.1 Key features of e-commerce with a substantial effect on distribution strategies

1.1.1 Price transparency leading to an increase in price competition

1.1.2 Free-riding

1.1.3 Increased direct retail activities by manufacturers

1.1.4 Expansion of selective distribution

1.2 Potential barriers to competition

1.2.1 Cross-border sales restrictions

1.2.2 Restrictions on the use of marketplaces

1.2.3 Restrictions on the use of price comparison tools

1.2.4 Pricing restrictions

1.2.5 Other types of restrictions to sell or advertise online

1.2.6 The use of data in e-commerce

2. Key Findings: Digital Content

2.1 Licensing of rights: A key factor for competition in online digital content services

2.2 Contractual restrictions in relation to transmission technologies, timing of releases and territories

2.3 Duration of the agreements

2.4 Payment structures

2.5 Impact of licensing practices

A. INTRODUCTION

1. The wider context: The Digital Single Market strategy

(1)On 6 May 2015, the Commission adopted the Digital Single Market strategy.

(2)The Digital Single Market strategy outlines several key actions under three pillars by means of which the Commission envisages to create a Digital Single Market. One of these pillars relates to ensuring better access for consumers and businesses to goods and services via e-commerce across the EU.

(3)Under this pillar the Commission has already undertaken and will further undertake several actions, including legislative proposals in the following areas: (i) harmonised EU rules on contracts for the supply of digital content and for the online and other distance sales of goods and the cooperation between national authorities responsible for the enforcement of consumer protection laws, (ii) efficient and affordable cross-border parcel delivery, (iii) unjustified geo-blocking, (iv) simplified VAT rules and (v) copyright modernisation. The Commission is also assessing the role of online platforms and intermediaries.

(4)Under this pillar of the Digital Single Market strategy, the Commission decided on 6 May 2015, on the basis of the EU competition rules, pursuant to Article 17 of Regulation 1/2003,

to launch a sector inquiry into trade of consumer goods ("goods") and digital content in e-commerce in the EU.

(5)While most of the actions of the Digital Single Market strategy essentially seek to address regulatory barriers to cross-border online trade in goods and services, the sector inquiry into e-commerce investigated barriers created by companies.

(6)The sector inquiry focused on distribution agreements for goods and services that may create barriers to e-commerce. With respect to online platforms, the sector inquiry gathered information on conduct of companies active in e-commerce (notably marketplaces and price comparison tools). It does not relate to conduct of online platforms more generally. The sector inquiry therefore complements the Commission's legislative proposals and the initiatives on online platforms under the Digital Single Market strategy.

2. The reasons for launching the sector inquiry

(7)E-commerce in the EU has grown steadily over the past years. Today the EU is one of the largest e-commerce markets in the world. Based on Eurostat data, the percentage of individuals aged between 16 and 74 having ordered goods or services over the internet, has continuously grown from 30 % in 2007 to 55 % in 2016.

(8)The proportion of online buyers varies from Member State to Member State, but it is growing steadily everywhere. The highest percentage of online buyers can be found in the United Kingdom (where 87 % of the total population aged between 16 and 74 made purchases online) and the lowest in Romania (where 18 % of the total population aged between 16 and 74 made purchases online). There is a positive correlation between the percentage of customers engaging in online shopping and the internet penetration rate.

Figure A. 1: Internet users who bought or ordered goods or services for private use over the internet in the previous 12 months, 2012 and 2016 (% of internet users) - Source: Eurostat

(9)

Figure A. 2

below presents the estimated evolution of online and total retail sales in the EU between 2000 and 2014. During that period, the estimated average annual growth rate in the online sales of goods was approximately 22 %, despite the 2008 economic crisis and the drop in overall retail sales between 2007 and 2012. At the same time the proportion of companies engaging in online sales did not grow significantly between 2004 and 2014.

Figure A. 2: Estimated evolution of the total and online retail sales in goods, 2000-2014 (in billion EUR) - Source: Duch-Brown and Martens

(10)E-commerce in the EU is geographically concentrated: the United Kingdom, Germany and France concentrate more than 60 % of EU online sales.

(11)The proportion of individuals aged between 16 and 74 in the EU, who ordered goods or services over the internet for private use reached 66 % in 2015.Despite the growth of e-commerce, in the same year 18 % shopped online from a seller established in another Member State.

Figure A. 3: Domestic and cross-border online shopping, EU-28, 2008-2016 (% of people aged 16 to 74) - Source: Eurostat

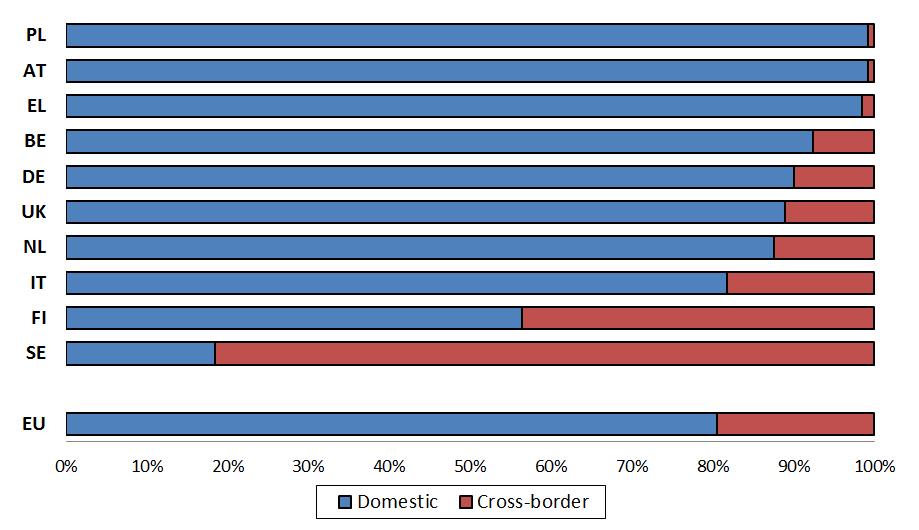

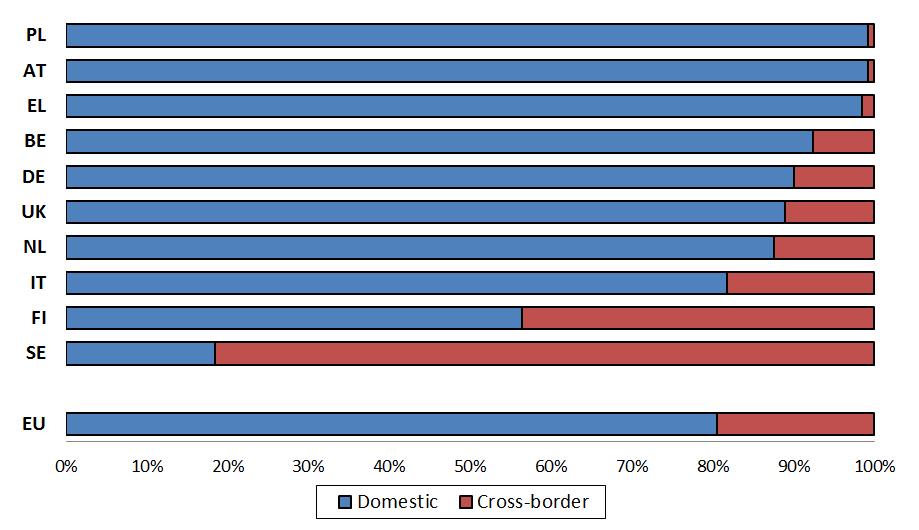

(12)Eurostat data reveal that in 2014 in the EU 19 % of companies engaged in online sales, but only 8 % of them made online sales to customers located in other Member States. In 2014, 85.4 % of online sales of companies stem from domestic sales and 10.3 % stem from EU cross-border sales.

(13)A mystery shopping survey conducted on behalf of the Commission at the end of 2015 found that only 37 % of websites allow cross-border EU customers to reach the stage of successfully entering payment card details, i.e. the final step before completing a purchase.

(14)There are also significant differences between Member States when it comes to the proportion of customers in a particular Member State that shop online from retailers located cross-border. For example, while 70 % of residents of Luxembourg engage in cross-border online shopping, only 2 % of residents of Romania do the same. As a general trend, the relative (population-weighted) intensity of cross-border e-commerce is inversely related to population size: customers in smaller Member States are more active in cross-border purchases than those of larger ones.

Figure A. 4: Cross-border internet purchases by individuals, 2016 (% of people aged 16 to 74)

Source: Eurostat

(15)Digital content in the EU accounted for 32 % of online trade by individuals buying online in 2014. A total of 40 % of individuals used the internet to access media content online in 2014, up from 21 % in 2007.

(16)A Eurobarometer report

indicates that in 2014, around half of the EU citizens responding to the survey accessed or downloaded audio-visual content and music online, with 30 % of them doing so via subscriptions or individual transactions. However, only a third of them could find the audio-visual content they wanted. While a minority of customers reported trying to access online digital content cross-border (8 %), this proportion is substantially higher for younger people (17 %) and is growing, as they look for digital content which is available outside their Member State of residence. According to the same report, more than 50 % of customers have experienced problems when trying to access digital content cross-border.

(17)Different studies point to a wide range of reasons, both on the side of customers and on the side of the retailers that may explain the modest growth of cross-border e-commerce in the EU. For instance, according to a Eurobarometer report, the most common difficulties companies encounter when selling online are related to cost. Retailers are concerned that delivery costs are too high (51 %), that guarantees and returns are too expensive (42 %), or that dispute resolution is too expensive (41 %). According to the same report, for almost one third (32 %) of retailers slow internet speeds are a problem, and for 15 % of retailers, the complications or costs of dealing with foreign taxation is a major problem. Additional reasons for not engaging in cross-border sales are lack of knowledge of applicable laws and lack of foreign language skills.

(18)When it comes to customers, they are more confident in making domestic online purchases (61 %) than they are in purchasing online from retailers in other Member States (38 %). Surveys and studies invoke different reasons for this difference. Concerns regarding delivery and return possibilities, as well as doubts about misuse of payment card information and personal data may deter customers from shopping online from retailers in another Member State. This adds to the more subjective obstacles to cross-border sales, such as language differences and customer preferences.

(19)Similarly to private persons, when companies purchase online, they are mostly concerned that delivery costs are too high (57 %), that resolving complaints and disputes cross-border is too expensive (53 %), and that their data are not well protected in another Member State (44 %).

(20)However, there are also indications that companies establish barriers to cross-border online trade through contractual provisions or concerted practices that limit the ability of retailers or service providers in one Member State to serve online customers located in another Member State. For example, according to a 2015 Eurobarometer report, 16 % of companies that sold online in 2014 or tried to do so indicate that the existence of restrictions imposed by their suppliers on selling to customers located in another Member State is a problem (and for 6 % it is a major problem).

(21)The growth of e-commerce provides for a number of challenges for companies in terms of their distribution strategies.

(22)New distribution methods and models emerge online. Smartphones and mobile apps are increasingly used for e-commerce. New apps also allow customers to scan product codes, compare prices and purchase products online. Based on Euromonitor data, mobile internet retail amounts to more than one-third of total e-commerce.

(23)Companies and customers increasingly use platforms, in particular marketplaces and other intermediaries/price comparison tools. An increase in online sales puts challenges to existing distribution networks, in particular to brick and mortar retailers. Some companies react to these challenges with recourse to vertical restraints.

(24)Over the last decade certain National Competition Authorities have been particularly active in assessing contractual restrictions in e-commerce. For instance, in 2012 the French Authority conducted a sector inquiry into e-commerce; while the German, French, UK and other National Competition Authorities carried out several investigations into different types of contractual restrictions used in e-commerce.

(25)These cases indicate that certain contractual restrictions used in e-commerce have given rise to concerns and warrant closer scrutiny from the Commission in order to ensure effective competition across the EU and to contribute to a consistent interpretation of the existing rules.

3. The purpose of the sector inquiry

(26)Sector inquiries are investigations that the Commission decides to carry out in sectors of the economy or types of agreements when there are indications that competition may be restricted or distorted within the internal market.

(27)A sector inquiry is a systematic investigatory tool used to obtain a better understanding of the functioning of a given sector and the types of agreements used in this sector. Through this sector inquiry, the Commission sought to understand how the growth of e-commerce has influenced the choices made by companies regarding the distribution of their products and services and to what extent the growth of e-commerce has led to an increase in contractual restrictions or the emergence of new types of contractual restrictions.

(28)Sector inquiries do not target specific companies. However, the results of a sector inquiry may point to potentially anti-competitive practices and the Commission may – following a sector inquiry – decide to open case-specific investigations. Thus, sector inquiries allow the Commission to set priorities in the enforcement of EU competition rules.

(29)In view of the purpose and nature of the e-commerce sector inquiry, the data collected and presented in the Report should be read as summaries of the qualitative information obtained. They are not intended to be read as statistically relevant figures in the strict sense.

4. The main steps of the sector inquiry

(30)Following the decision

to launch the sector inquiry, the Commission started a large-scale fact finding exercise, on the basis of requests for information pursuant to Article 17 of Regulation 1/2003 ("questionnaires") between June 2015 and March 2016.

(31)Questionnaires were sent to various actors in the EU in relation to online sales of both goods and digital content.

(32)As an interim step, the Commission published in March 2016 initial findings on geo-blocking in an Issues paper. On 15 September 2016 the Commission published a Preliminary Report.

(33)The publication of the Preliminary Report was followed by a public consultation open to all interested stakeholders. The public consultation ended on 18 November 2016. Altogether, the Commission received 66 submissions.

(34)Interested stakeholders also expressed their views at a stakeholder conference in Brussels on 6 October 2016. The event provided an opportunity for different stakeholders to put forward their views on the Preliminary Report.

(35)The sector inquiry is completed by the adoption of a Communication from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament. The Communication is accompanied by this Report which summarises the main findings of the sector inquiry.

5. Analytical framework

(36)The following paragraphs outline briefly the relevant analytical framework underlying the analysis of the data gathered in the sector inquiry. The aim is not to provide a comprehensive summary of the possible positive or negative effects on competition of contractual restrictions used in e-commerce, but to set the legal and economic background in the light of which the information provided during the sector inquiry will have to be read.

(37)On the one hand, vertical restraints may affect the market structure and the intensity of competition, mainly through foreclosing markets, softening competition and facilitating collusion. Importantly, and as acknowledged in the Vertical Guidelines, competition concerns with vertical restraints would normally arise only if there is insufficient competition at one or more levels of the supply chain. Moreover, an important objective which guides any assessment under European competition law is that of achieving an integrated internal market. As a result, the creation of obstacles to market integration is a concern with regard to vertical restraints.

(38)In relation to goods, the sector inquiry examines the prevalence of certain distribution models, such as exclusive and selective distribution agreements, as well as contractual provisions limiting the ability of retailers (i) to sell cross-border within the EU, (ii) to sell on marketplaces, (iii) to use price comparison tools, and (iv) to set the retail price freely. Such provisions may restrict competition and may lead to the partitioning of the internal market in breach of the EU competition rules. A detailed assessment of the different restrictions and the applicable legal framework is presented in the sections dedicated to the specific restrictions.

(39)In relation to digital content, the sector inquiry investigates the presence of territorial restrictions and geo-blocking in the online distribution of digital content, with a focus on music and audiovisual content. The sector inquiry also examines the prevalent copyright licensing models for online distribution and their possible impact on competition, in particular, with respect to market entry and the possibility of developing new business models or new services.

(40)The focus is on exclusive licensing and in particular its modalities which, under certain conditions, could raise concerns of input foreclosure and the resulting reduction of competition at the distribution level. Exclusive licensing may also raise concerns about exclusion of actual or potential competing distributors at the distribution level. The issue of access to digital content and potential exclusion of digital content providers is particularly important given the nature of digital content distribution, where offering certain (premium) content may be necessary in order to attract customers.

(41)On the other hand, vertical restraints may benefit customers, mainly, but not only, through allowing companies along the supply chain to internalise external effects arising either vertically (between a supplier and its distributors) or horizontally (between distributors or between suppliers). Vertical restraints may also help avoiding hold-up in case of relationship-specific investments, alleviate capital market imperfections and, more generally, reduce transaction costs. Dynamic considerations related to investments in the creation of new products may also be relevant for the assessment of certain vertical restraints.

(42)Vertical externalities arise because of the complementary nature of the role of suppliers and distributors in the process through which goods and services reach customers. The decisions and actions taken at the different levels of the supply chain determine aspects of the product offering such as price, quality, service level and marketing, which affect not only the company taking the decisions but also its commercial partners at other levels of the supply chain.

(43)For instance, retail investment in assuring a particular quality or brand image and, more generally, the offering of demand-enhancing customer services, such as promotion, pre-sale advice by specialised selling staff, or post-sale assistance, do not only benefit distributors but also their suppliers. However, a distributor deciding independently on the level of such services will not take into account the profits accruing to the supplier from each additional sale or from maintaining a reputation for high quality. Hence, he may choose a suboptimal level of these services from the point of view of the supplier and, under certain conditions, also from the point of view of customers.

(44)Similarly, independent retail price setting may lead to higher retail prices and lower joint profits compared to a situation where decisions of suppliers and distributors were to be coordinated with a view to maximising their joint profits.

(45)Horizontal externalities may arise between distributors of the same product when a distributor cannot appropriate fully the benefits of his (costly) sales effort. For instance, demand-enhancing pre-sale services offered by one distributor, such as personalised product advice, may lead to increased sales from competing distributors offering the same product and, thus, create incentives among distributors to free-ride on costly services provided by others. For example, customers may visit a brick and mortar shop to try out a product or obtain other useful information on the basis of which they take the decision to purchase, but then order the product online from a different distributor.

(46)The possibility of such free-riding and the respective inability of the distributor that offers customer services to appropriate fully the benefits, may lead to suboptimal provision (in terms of quantity and/ or quality) of such services from the point of view of the vertical supply chain.

(47)In the presence of such externalities, suppliers have the incentive to control some aspects of the distributors' operations. In particular, through establishing common ownership of the different levels of the supply chain (vertical integration) or through employing different vertical restraints, suppliers could internalise the abovementioned external effects, increase the joint profit of the vertical supply chain and, under certain circumstances, consumer welfare.

(48)For example, granting exclusivity or setting up a selective distribution system may be a way for suppliers to alleviate free-riding and to restore the incentives of retailers to increase sales effort. Imposing price restraints could achieve the same objective. Free-riding concerns among retailers and the need for exclusivity may be particularly relevant in cases where establishing a new brand or an existing brand in a new market requires substantial (sunk) investments on the retailer side.

(49)A selective distribution system may also help suppliers build reputation for high quality and convey a desired brand image. Sometimes it may be important for a supplier to signal its quality through limiting its distribution to certain distributors that have a reputation for selling high quality products only and this can be achieved, for example, through exclusive or selective distribution.

(50)Vertical restraints could also be employed to deal with opportunistic behaviour that may arise with the so-called relationship-specific investments, i.e. investments that have little value outside the specific vertical relationship.

(51)Once such investment has taken place and to the extent that it is largely sunk, the party which bears the cost of the investment could find itself in a weak bargaining position vis-à-vis its trading partner who may have an incentive to engage in opportunistic renegotiation of the terms of the deal. In anticipation of this, the incentives to invest are likely to be weaker and, therefore, the level of investment may be suboptimal from the point of view of the vertical supply chain.

(52)Such situations may arise with respect to investments made both by distributors and by manufacturers. For instance, distributors may have to invest in special retail facilities, which cannot be used for the distribution of other manufacturers' products. Granting exclusivity could be a way for manufacturers to provide sufficient investment incentives to distributors.

(53)Finally, exclusivity may contribute to the alleviation of problems related to the presence of asymmetric information in the context of capital provision. Such considerations could be particularly relevant for the digital content sectors, where one may encounter high uncertainty on the demand side and high sunk production costs on the supply side.

(54)Often the same objective could be achieved through different vertical restraints but their effectiveness in solving the problems mentioned in the previous paragraphs and the extent to which customers benefit will depend on the specific circumstances of the vertical relationship.

(55)Different vertical restraints can also play a complementary role, as sometimes the impact of a vertical restraint may be limited when it is employed in combination with another type of vertical restraints.

(56)The sector inquiry is not case-specific and does not aim at assessing in detail whether certain restraints are justified in the context of a particular vertical relationship but rather to provide insights into the motivation of companies to employ vertical restraints in relation to e-commerce and to explain the considerations viewed by the Commission as relevant for the analysis of those restraints.

6. Selection of addressees: goods

(57)The e-commerce sector inquiry is carried out on the basis of responses to questionnaires sent to a large number of companies active in e-commerce.

6.1 Selection of retailers

(58)There is no single data source covering the population of retailers selling online in the Member States. Therefore, for the list of addressees to the retailers' questionnaire, the Commission relied on a number of databases, such as Amadeus, Euromonitorand Veraart Research, as well as information received from professional associations. The Commission also conducted desk research to verify the relevance of potential addressees of questionnaires and, ultimately, to refine the list of selected addressees.

(59)In order to ensure that the list of addressees included companies of different sizes, and also covered a large part of the market in terms of sales, the Commission followed a two-step approach.

(60)First, all companies relevant for the purposes of the sector inquiry and for which contact details could be obtained were selected among the "large" and "very large" companies active under given NACE code contained in the Amadeus database, as well as among the companies contained in the Euromonitor database.

(61)Second, a number of smaller companies were randomly chosen for each Member State from the Amadeus database (excluding the "very large" and "large" companies) and the data received from professional associations. For some Member States, a dataset from Veraart Research was also used to cross-check and complement the list of addressees.

(62)The Commission also sought to achieve a broad geographic coverage with a minimum of 20 addressees per Member State. The Commission relied on available Eurostat data to obtain a rough approximation of the distribution of companies selling online across Member States.

(63)Specifically, the datasets used contained, per Member State, the total number of companies with at least 10 employees, as well as the percentage of companies having received orders via computer mediated networks, belonging to NACE code G in 2012. On the basis of these data, the Commission approximated the distribution of companies selling online across the Member States and calculated weights for the 28 Member States.

(64)The number of responses received per Member State was then affected by varying response rates in the Member States, the inclusion of additional websites that were reported by addressees of the questionnaires as well as by spontaneous requests for participation and de-activation of questionnaires for companies that were either never active or no longer active in e-commerce.

6.2 Selection of manufacturers

(65)The questionnaire addressed to retailers requested a significant amount of data on their business relationships with manufacturers. The responses provided by retailers were useful for selection of the companies to which a "manufacturer questionnaire" was addressed. In addition, the Commission sought to include manufacturers in all the product categories covered by the sector inquiry and to ensure that the major players in those product categories were included.

6.3 Selection of marketplaces, price comparison tools and payment system providers

(66)Relevant marketplaces and price comparison tools were identified based on information received from professional associations and complemented by desk research. The selection includes the most important marketplaces and price comparison tools in the EU, including both the biggest international players and the most relevant regional ones, covering the sale and price comparison of all products within the scope of the sector inquiry. Similarly to retailers, marketplaces were requested to respond on a per website basis.

(67)Payment service providers were identified based on information received from professional associations and complemented by desk research. The selection includes players that could provide information about their services in most of the Member States, as well as the most important regional players that offer their services in only one or a few Member States.

6.4 Responses received

(68)Different questionnaires were sent to online retailers ("retailers"), marketplaces, price comparison tools, payment system providers and manufacturers.

(69)Questionnaires to retailers, marketplaces and price comparison tools had to be filled out on a per website basis, which means that some companies have received and responded to several questionnaires for each website they operate (in one or more Member States). Each such website specific response is counted separately and included in the number of respondents. Therefore throughout this Report the terms "retailer" and "respondent to the retailers' questionnaire" refers to a response with regard to a retailer website. Questionnaires were sent out to companies in all Member States.

(70)

Table A. 1

shows the number of respondents to the retailers' questionnaire per Member State as well as the number of respondents to the questionnaires sent to other market participants.

Table A. 1: Respondents to the sector inquiry in relation to goods

(71)The 1453 respondents submitted in total 2605 agreements related to the distribution of goods.

(72)Questionnaires were mainly sent to market participants active in the product categories most sold online, namely:

(a)Clothing, shoes and accessories;

(b)Consumer electronics (including computer hardware);

(c)Electrical household appliances;

(d)Computer games and software;

(e)Toys and childcare articles;

(f)Media: books (including e-books), CDs, DVDs and Blu-ray discs;

(g)Cosmetics and healthcare;

(h)Sports and outdoor equipment (excluding clothing and shoes); and

(i)House and garden.

7. Selection of addressees: digital content

(73)The part of the sector inquiry related to digital content aims at identifying potential contractual restrictions between suppliers (right holders) and providers of online content services.

7.1 Selection of digital content providers (retail markets)

(74)The sector inquiry focuses only on companies offering online services as part of, or as the entirety of, their services. At the retail level, i.e. at the level of services provided directly to users, such companies are referred to as digital content providers.

(75)For the purposes of this Report a digital content service is considered as being offered online when it is transmitted using the packet switching protocol standard used on the internet, i.e. TCP/IP, when being delivered to end users' premises.

(76)The starting point for the digital content provider addressee list was a database comprising more than 2 000 online audio-visual operators across the EU. The list was then narrowed down, with a view to ensuring that the final list of addressees would include the following three categories of providers in each Member State:

(a)The most important market operators in each Member State;

(b)Any potential recent entrant or operator using innovative business models; and

(c)A sufficient number of smaller / local operators.

(77)Given the nature of digital content services the final list includes a relatively limited number of operators in each Member State which however account for the majority of the audience / market. They are referred to as digital content providers from Member States.

(78)Some of the operators contacted, have a relatively large cross-border presence, either directly or via subsidiaries. These groups were identified separately and defined as those which have operations in at least five Member States. They are referred to as large groups.

(79)A number of additional questionnaires were addressed to operators which offer online content through agreements whereby such operators host service providers within a hosting environment with a specific set of characteristics, either via software ("hosting online operator") or via hardware ("hosting device"). A revenue sharing agreement can be part of the relationship between the service provider and the hosting operator, while the relationship with the customer may be directly with the former or with the latter, depending on the specific situation. This category of providers is referred to as hosting operator.

(80)Respondents belonging to each of the three categories above were chosen on the basis that they offer an online service. The online service did not need to be their exclusive or even main activity. However the questionnaires only refer to the online service and not any other aspect of the companies’ offer. A set of questionnaires was sent to providers of VPN

and IP routing services, which are often accessed by users to bypass geo-blocking. Many of these companies are not established in the EU, even though they might provide services to customers in the EU. Therefore the number of respondents was unsurprisingly low for this category.

(81)Digital content providers were asked to submit information in relation to the following categories of products:

(a)Films: Feature films and motion pictures;

(b)Sports: Sports events and sports programmes, including commentaries;

(c)Television fiction: Television comedy, drama and animation series or programmes;

(d)Children television: Television programmes and series aimed at children, excluding feature films;

(e)News: Television news and current affairs programmes and series;

(f)Non-fiction television: Television content other than films, television fiction, children's programmes, news and sports events; and

(g)Music: Recorded music, excluding music contained in audiovisual content such as background music in films and television programmes.

(82)A total of 278 digital content providers submitted information in the context of the sector inquiry, including 6 426 licensing agreements. A further 9 companies offering VPN and IP routing services responded to their questionnaire.

Table A. 2

below provides the number of respondents per Member State and by category of respondent identified above.

Table A. 2: Respondents to the sector inquiry in relation to digital content (digital content providers)

7.2 Selection of right holders (wholesale markets)

(83)Questionnaires were also sent to right holders. Right holders were asked to submit information solely in relation to licensing agreements covering, partly or fully, the rights for digital content services provided online.

(84)Right holders were selected on the basis of the information provided by digital content providers about their main suppliers and with a view to ensuring a relatively broad coverage across the EU and sufficient diversity across product types.

(85)Compared to the questionnaires sent to digital content providers, fewer product types were covered in those sent to right holders. In particular, films were excluded in order to avoid any potential overlaps with an investigation into the cross-border provision of films by pay-TV providers

that the Commission is conducting. News and non-fiction television products were also excluded from the questionnaire to right holders, since these products were already amply covered in the questionnaires to digital content providers.

(86)Right holders were asked information in relation to the following product types:

(a)Sports: A sports event, such as a football match, or a set of sports events, such as a football season, which is the object of a broadcast production or productions;

(b)Television fiction and children television: Television series, comedy, drama, or entertainment programmes, excluding feature films, and television programmes and series aimed at children, excluding feature films; and

(c)Music: Recorded music, excluding music contained in audiovisual content such as background music in films and television programmes.

(87)A total of 53 right holders replied to the sector inquiry and submitted a total of 282 licensing agreements (

table A. 3

).

Table A. 3: Respondents to the sector inquiry in relation to digital content (right holders)

B. E-COMMERCE IN GOODS

1. Characteristics of respondents

1.1 Retailers

(88)Overall, the Commission received responses to its questionnaire from 1051 retailers. Respondent retailers cover a wide variety of companies in terms of size, measured either by the number of employees or by the annual turnover generated.

Figure B. 1

shows the distribution of retailers across predefined ranges in terms of the number of employees. About half of the respondent retailers have less than 49 employees and more than one third have less than 9 employees.

Figure B. 1: Proportion of retailers by number of employees

22 % of the retailers generated a turnover of less than EUR 500 000 in 2014, whereas 28 % had a turnover above EUR 100 million, with an approximately equal distribution of retailers of intermediate sizes.

(89)Approximately 30 % of the respondent retailers are also acting as wholesalers and/or manufacturers: 26 % of the respondent retailers are active both at the retail and wholesale level, while 9 % are (also) active in manufacturing.

(90)The respondent retailers are mainly active in nine broad product categories (a tenth category covers all "other" products):

Figure B. 2: Distribution of retailers across product categories (number of retailers)

(91)A significant number of retailers are active in several product categories: 46 % are active in one product category, nearly 20 % in two categories, 8 % in three categories, 11 % sell products in four or five different categories and more than 15 % sell products in at least six different product categories.

(92)The majority of respondent retailers are selling both offline and online while a considerable proportion is only selling online without any brick and mortar shop.

Figure B. 3: Proportion of retailers by sales channel, 2014

(93)92 % of respondent retailers are selling via their own website (which does not exclude that they also sell via other sales channels). Around a third of respondent retailers are selling via a marketplace or supply data-feeds to price comparison tools in order to advertise their products. 38 respondents (representing approximately 4 % of respondent retailers) were selling online only via marketplaces, i.e. without having their own website.22 of these respondents were not selling offline. For them, marketplaces are the only sales channel they rely on.

Figure B. 4: Online sales and advertisement activities of respondent retailers

(94)For the purposes of this Report, the terms "pure offline players" and "brick and mortar retailers" refer to retailers that only sell in their offline (physical) shop. "Pure (online) players" refers to retailers that only sell online, whether via their own website and/or via third party websites (i.e. marketplaces). "Click and mortar" retailers, "brick and click" retailers and "hybrid" players refer to retailers that sell both online and offline.

1.2 Manufacturers

(95)Respondent manufacturers are evenly distributed in terms of size as measured by the number of employees:

Figure B. 5: Proportion of manufacturers by number of employees

(96)In terms of revenues generated in 2014 in the EU, 13 % of respondent manufacturers have a turnover of less than EUR 10 million, approximately 50 % between EUR 10 million and EUR 500 million, and approximately 35 % above EUR 500 million.

(97)Respondent manufacturers are active in all product categories covered by the sector inquiry, with 26 % active in at least two product categories.

Figure B. 6: Distribution of respondent manufacturers in terms of product categories (number of manufacturers)

(98)For the purposes of this Report, in relation to e-commerce of goods, the terms "manufacturers" or "suppliers" refer to both manufacturers that (fully or partially) own the manufacturing facilities and control the manufacturing process, and those that (fully or partially) outsource manufacturing, but own the brand and control distribution strategies.

1.3 Marketplaces

(99)Online marketplaces are multi-sided platforms bringing together different user groups (sellers, buyers and potentially advertisers) and facilitating transactions between them. They allow sellers to list their products on the marketplace and allow buyers of the marketplace to find and buy these products.

(100)37 marketplaces responded to the questionnaire addressed to marketplaces. The respondents to the questionnaire operate marketplaces targeting altogether customers in 14 Member States. The Member States which are most targeted by marketplaces are Germany and France.

(101)The "oldest" marketplaces in the sample were launched in the EU between 1998 and 2001. The marketplaces that were established first tend to be the biggest marketplaces today. Nonetheless, seven respondents launched their marketplaces in 2013 or later. The size of marketplaces varies widely and ranges from marketplaces with a 2014 turnover exceeding EUR 1 billion to marketplaces with a 2014 turnover of less than EUR 100 000.

(102)The business models followed by marketplaces vary significantly between different marketplace operators.

(103)Some marketplace operators provide solely the sales platform without engaging in any activity as a seller on that platform ("pure" marketplaces). Other marketplace operators also act as a retailer in addition to offering the sales platform to sellers. In this case, they typically present the products for which they are a retailer together with products of other sellers on the marketplace website. In many cases, they sell the same products in direct competition with those of other sellers on the platform.

(104)The proportion of third party sales on such marketplaces compared to own retail sales varies from one marketplace to the other and depends to a large extent on the chosen business model of the operator and whether its business started as a retailer or as a marketplace provider. As can be seen from

figure B. 7

, out of the 37 respondent marketplaces, more than two thirds are pure marketplaces, while approximately a third also acts as a retailer.

Figure B. 7: Proportion of "pure" marketplaces and marketplaces that act as a retailer

(105)Marketplaces also differ in terms of the sellers they accept and the selection criteria they apply in relation to sellers. Most marketplaces are open to all interested sellers that comply with basic requirements,

accept the conditions of the marketplace and are considered sufficiently professional and reliable. However, some marketplace operators do not open their marketplace to all third party sellers. The main business model of these operators is typically that of a retailer.

(106)Third party sellers in such "closed" marketplaces are usually sellers whose product range complements the product portfolio offered by the marketplace operator/retailer in question or sellers that pre-existed as suppliers of the marketplace operators/retailer in question. A customer buying a product via a "closed" marketplace will not necessarily know that there is a third party involved in the sale.

(107)Most marketplaces allow sales of all products, provided that such products can legally be sold and the retailer is able to provide the product information required by the marketplace. A number of marketplaces reported that they only accept new products and do not allow the listing of second-hand products. Some marketplaces do not allow sales of products which are sold under a selective distribution agreement, unless the retailer can prove that he or she is authorised to sell them.

(108)There are also a number of differences between marketplaces concerning the contractual arrangements with customers. The party contracting with the customer is not necessarily the third party seller in all marketplaces. Some marketplaces report that they are either separately or jointly with the third party seller contractually liable vis-à-vis the customer. Approximately 8 % of respondent marketplaces indicate that they act as an agent for the seller.

(109)While, in general, marketplaces established earlier cover a broad range of different product categories, more recent market entrants tend to launch their marketplace to target niche product segments or specific customer groups. Such marketplaces may, for example, specifically target customers in a certain city or region, sellers aiming to get rid of overstock, or specialise in certain product categories or fair-trade products. However, more than 80 % of the respondents report being active in all product categories covered by the sector inquiry.

(110)Many marketplaces allow sales only by professional sellers, i.e. trading as a business. Some marketplaces offer different remuneration models depending on the intended level of activity of the seller. Others accept also private sellers, i.e. individual persons selling on their own account. On average, approximately 78 % of sellers on the respondent marketplaces are professional sellers, whereas 22 % are either private sellers or sellers which chose a remuneration scheme for limited sales activities.

Some marketplaces have initially started as platforms targeting private sellers and only later opened up to professional sellers. The amount of active professional sellers

reported by marketplaces range from less than 50 to more than 300 000 for 2014.

(111)The business models of marketplaces also differ in terms of services offered to sellers.

As can be seen from

figure B. 8

, more than half of the respondent marketplaces provide sellers with a standard layout for product presentation, offer advertising possibilities, customer services (including complaints handling), and dispute resolution assistance as well as payment services. Less than a third of the marketplaces that responded to the questionnaire offer delivery services, product return management services or storage space.

Figure B. 8: Proportion of marketplaces offering certain services in addition to marketplace function

(112)Remuneration models also differ between the various respondent marketplaces. Most operators use a fixed (monthly) fee and a per sale transaction fee/commission, which requires the seller to pay a certain proportion of the sales value to the marketplace operator. The level of the per sale transaction fee/commission may differ between different marketplaces as well as between different product categories and the margins achievable by retailers in these product categories. Fee levels are typically lower for consumer electronics than for other products. Some respondents also indicate that they only charge a per sale transaction fee/commission without a fixed fee. Some marketplaces additionally charge a fee per item that is being listed on the marketplace for sale. Rebates offered by marketplaces to sellers take the form of discounts on the per sale transaction fees to either key sellers or to sellers that make use of specific offerings of the marketplace (i.e. top rated seller programs) or sellers that establish a seller shop on the marketplace.

(113)The majority of the contractual relationships that marketplaces have in place with sellers are based on standard agreements. Only 13 % of the marketplaces indicate that more than 10 % of the agreements they have in force with professional sellers are negotiated individually.

(114)More than half of the marketplaces indicated to supply data-feeds to price comparison-tool providers

and to use external online payment systems.

86 % of marketplaces report that some of their professional sellers are using third parties for managing their business processes on the marketplace. Such third parties can help sellers to upload their product, inventory and price information on one or more marketplaces, process orders, manage inventory and assist with cross-border trade. They can provide sellers with easily accessible data on their sales activities across multiple online sales channels.

(115)Some marketplaces do not only offer a website, but also an app which can be easily accessed with mobile devices such as smartphones.

1.4 Price comparison tools

(116)Price comparison tools are websites/apps that allow customers to search for products and compare their prices across several retailers and provide links that lead directly or indirectly to the product offerings. They do not offer the possibility to purchase the products directly through the website/app of the price comparison tool. Price comparison tools typically do not charge buyers for access to the services on their websites or apps. They are rather financed via payments by the sellers whose products are listed on the websites/apps. Price comparison tools allow customers to quickly compare prices for the same product across a large number of sellers, thereby increasing price transparency and allowing them to find the best available purchase option.

(117)89 price comparison tools responded to the Commission's questionnaire addressed to price comparison tools.

The respondents to the questionnaire operate price comparison tools which altogether target customers in 22 different Member States. The Member States which are targeted by most price comparison tools are Germany, UK and France.

(118)The majority of the price comparison tools each generated revenues below EUR 500 000 in 2014.

Figure B. 9: Proportion of price comparison tools per total turnover in 2014

(119)Price comparison tools are rarely specialised in comparing products for specific product categories. 78 % of respondents indicate that they provide pricing information on eight or more of the product categories covered by the sector inquiry. Almost all respondents provide pricing information in relation to consumer electronics (98 %) and household appliances (97 %), followed by computer games (94 %) and cosmetics and healthcare (82 %).

(120)The "oldest" price comparison tools in the sample were launched between 1997 and 1999. Price comparison tools normally do not require a registration of the customers and they can easily move from using one price comparison tool to another.

(121)Business models of price comparison tools differ considerably in terms of remuneration schemes, additional features such as product reviews and methods of data collection on product offerings.

(122)The majority of price comparison tools finance themselves via per unit charges to sellers. As can be seen from

figure B. 10

most respondents operate on a pay-per-click basis

whereby sellers are charged each time a customer is re-directed to the seller's website. The majority of respondents indicated that they (also) charge fees on a pay-per-sale/order basis.

Such fees often represent only a small proportion of the income of the respective price comparison tools and are frequently only applied to sales by a limited number of important sellers. Per unit charges typically differ between different product categories, reflecting the different profit margins of the products. Some respondents also charge fixed monthly fees to the sellers or allow them to bid to improve the placement of their products on the price comparison tool. Only a quarter of the respondents offer rebates to the sellers that list their products on the price comparison tool (such as volume discounts or free listings).

Figure B. 10: Per unit charges applied by price comparison tools

(123)There are a number of ways in which price comparison tools obtain the relevant product and pricing information which is displayed on their website/app. 9 out of 10 price comparison tools indicate that they receive relevant data feeds from the sellers. The majority of price comparison tools also source data from third parties which consolidate information from various sources. Some respondents also use publically available information (e.g. crawling and indexing seller's websites) on product offerings and prices.

Figure B. 11: Collection of relevant information by price comparison tools

(124)Price comparison tools frequently offer a number of other services to customers next to the price comparison function. These include, for example, customer reviews concerning products or web shops, professional product reviews, information on price history, price alarms and newsletter functionalities. Some operators also offer the possibility to ask product related questions or create lists of favourite products. Additional services which price comparison tools offer to sellers include provision of performance data, premium placement of offers, or advertising.

(125)As can be seen from

figure B. 12

price comparison tools often offer a range of possible product ranking criteria, the default ranking usually being according to price.

Figure B. 12: Proportion of price comparison tools offering certain ranking criteria

(126)Price comparison tools usually accept listing products if they fall within a tool's product category catalogue, the seller is able to provide the required information, and the seller is legally allowed to sell the product. Many price comparison tools report that they do not accept listing second hand goods. Price comparison tools typically also verify whether the seller's website is trustworthy and complies with basic legal obligations.

1.5 Payment service providers

(127)In total, 17 online payment service providers replied to the relevant questionnaire. The respondents range from large multinationals with a turnover over EUR 1 billion to a small regional player that achieved a turnover of below EUR 2 million in the last financial year.

(128)The value of online purchases that these payment service providers processed for retailers established in the EU grew by approximately 25 % per year since 2012.

(129)In terms of geographic coverage, the majority of respondent payment service providers provide services across the 28 Member States of the EU, and only three respondents serve fewer than 10 Member States.

(130)The main function of payment service providers is to facilitate payments between retailers and customers. For this reason, payment service providers tend to form partnerships with various financial entities in order to cover as many payment methods

as possible. On average, there are approximately 20 different payment methods for e-commerce available via payment service providers, according to the replies received. Some payment service providers accept over 50 different payment methods.

(131)The number of methods payment system providers accept varies from one Member State to another: several payment system providers accept more than 20 different payment methods in one Member State and less than 10 in others.

Summary

Manufacturers and retailers of all sizes are represented in the sample both in terms of number of employees and in terms of turnover. The majority of the respondent retailers sell products in more than one product category covered by the sector inquiry, but more than 25 % sell in at least four product categories. More than half of the respondent manufacturers also sell directly to customers. About one-third of respondent retailers use marketplaces to sell their products.

The business models as well as remuneration schemes of respondent marketplaces and price comparison tools are diverse. Sales via marketplaces occur directly on the website of the marketplace whereas price comparison tools only re-direct the customer to the website of the seller on which the transaction subsequently takes place. A third of the respondent marketplaces also act as retailers in addition to providing platforms that bring together third party sellers and buyers. Marketplaces as well as price comparison tools typically offer or display a wide range of products to attract customers and most offerings cover multiple product categories.

The coverage of Member States by payment service providers is fairly broad, while the number of methods available may significantly vary depending on the Member State.

2. Main features of competition in e-commerce in goods

2.1 The concentration of manufacturers and retailers in the sectors covered by the sector inquiry

(132) The degree of market power of parties to an agreement is a relevant aspect for the assessment of vertical restraints, as acknowledged by the Vertical Block Exemption Regulation ("VBER"). While the sector inquiry covers broad product categories that do not constitute relevant markets for the purposes of EU competition law, the results of the sector inquiry offer general insights regarding the level of concentration in the product categories covered, both at the retailer and manufacturer levels.

(133)In order to approximate the level of concentration of manufacturers and retailers in the product categories covered by the sector inquiry, the Commission requested manufacturers and retailers to name their "most important competitors" in the product categories in which they are active.

(134)The main manufacturers are active in the majority of Member States, with the exception of the category of house and garden where most manufacturers are only active in a few Member States. In clothing and shoes, more than 20 manufacturers are mentioned in each Member State, with the same 5 to 10 brands listed throughout all Member States. In the toys and childcare category, also the same 5 to 10 manufacturers are typically mentioned as main competitors in all regions of the EU. More than 20 manufacturers are mentioned in consumer electronics, in all Member States, referring largely to the same players. 10 to 20 manufacturers are reported in electrical household appliances, and sports and outdoor equipment. Over 20 main brands are mentioned in all Member States in cosmetics and healthcare, with a significant portion of those listed in the majority of Member States.

(135)At the retail level, in clothing and shoes, consumer electronics, as well as in cosmetics and healthcare, a significant number of retailers are mentioned as main competitors, with however a few retailers being active in nearly all Member States, and the leading (most mentioned) retailers varying from one Member State to the other. In household appliances, computer games and software; and in media, apart from one online player that is active in most Member States, the main retailers differ from one region of the EU to another.

(136)The findings of the sector inquiry do not indicate a high level of concentration at the manufacturing or retail level in the covered product categories. These findings are, however, without prejudice to the assessment of the relevant product and geographic markets in a particular case.

Summary

The responses provided in the sector inquiry do not generally point to a high level of concentration at the manufacturing or retail level in relation to the covered product categories: the number of manufacturers and retailers perceived as main competitors is significant throughout the different regions of the EU.

2.2 Main parameters of competition

(137)In order to understand better the competitive landscape in the sectors covered by the sector inquiry, the Commission sought the views of both retailers and manufacturers regarding the importance of various parameters of competition.

Figure B. 13: Rating the parameters of competition by manufacturers

(138)Although there are some differences between product categories in terms of the importance of each parameter, product quality, brand image and the novelty of the product are given the greatest importance by manufacturers in all product categories (with the exception of media products

). Ranked on the basis of the proportion of respondent manufacturers that have attached to it the highest level of importance, price only comes at between the fourth and sixth place, with on average only about 20 % of the manufacturers considering it as highly important.

(139)Under "other" parameters, manufacturers mostly stress the importance of the creative / innovative nature, the safety, the design, the ease of use of the product, the quality of the distribution network, the individual shopping experience, the ability to offer personalised advice, the satisfaction of individual customer needs, the number of points of sale, the delivery time, the diversity of products and environmental/sustainability considerations in the production process.

(140)Responses by retailers show a different picture. In particular, ranked on the basis of the proportion of respondents that have attached to it the highest level of importance, price emerges as either the most or the second most important parameter of competition throughout all product categories. The range of brands, availability of the latest models and quality are the next three most important parameters of competition. However, the importance of parameters varies according to the sales channel the retailer uses.

Figure B. 14

shows the responses by hybrid players which operate both offline and online shops, while

figure B. 15

represents the responses by pure online players.

Figure B. 14: Rating the parameters of competition by hybrid players

Figure B. 15: Rating the parameters of competition by pure online players

(141)Price is the parameter which is considered highly important by the highest proportion of both hybrid and pure players in nearly all product categories.

(142)However, in terms of proportion of retailers which attach to it a high level of importance, quality and customer service is often higher ranked by hybrid players, while the range of brands and/or availability of latest models are typically higher ranked by pure online players. In the product category of cosmetics and healthcare, a higher number of both hybrid and pure online players attach the highest level of importance to quality, rather than to price.

(143)Marketplaces were also asked about the importance of various parameters of competition with other marketplaces for buyers. For them, the range of available products as well as the marketplace image and user-friendliness of the website precede price considerations.

Figure B. 16: Rating the parameters of competition with other marketplaces for buyers

(144)Marketplaces were also asked to indicate the level of importance of a number of pre-defined factors for attracting sellers to their platform. On average, across product categories, the factors to which marketplaces attach the highest importance are number of buyer visits followed by conversion rates and charges to professional sellers.

Figure B. 17: Rating the parameters of competition with other marketplaces for sellers

(145)Price comparison tools were asked about the importance of several factors for competing with other price comparison tools for buyers. As can be seen from

figure B. 18

, price comparison tools consider the availability of the latest product models as well as the range of available products as important. User-friendliness and the number of registered sellers are also factors considered as important. The ability to be found by search services, speed, and the accuracy of data/prices were also mentioned as key factors for competing with other providers.

Figure B. 18: Importance of certain parameters of competition with other price comparison tools for buyers

(146)Price comparison tools were also questioned about the importance of several factors in attracting more sellers on their website/app. The factors considered of highest importance by the largest proportion of respondents are the number of customer visits and charges applied to sellers followed by the image of the price comparison tool and the quality of product presentation. Geographic coverage as well as product and customer reviews were considered as less relevant.

Summary

Product quality and brand image are considered to be the most important parameters of competition by manufacturers, while price is considered as most important for both pure online and hybrid retailers. Quality and range of available brands are the second and third most important parameters for hybrid players, while the range of available brands and availability of the latest models are respectively the second and third most important parameters for pure online players. Marketplaces consider the range of available products, the marketplace image, user-friendliness, and the price of products as the parameters of the highest importance for their ability to compete for buyers.

2.3 Pricing

(147)The results of the sector inquiry show that the increased price transparency online is the feature that most affects the behaviour of customers and retailers. It lowers search costs for customers who are able to instantaneously obtain and compare product and price information online and switch swiftly from one channel to another (online/offline). Manufacturers and retailers are also able to easily monitor prices.

(148)The ability to directly compare prices of products across a number of online retailers, leads to increased price competition, affecting both online and offline sales. The ability to easily compare prices furthers cross-border trade as customers can more easily compare between products or services from different Member States and benefit from price differentials of competing retailers.

Likewise, if a retailer in one Member State is contemplating entering the market in another Member State, this is facilitated by better awareness of the conditions in that market.

(149)53 % of the respondent retailers track the online prices of competitors, out of which 67 % use automatic software programmes for that purpose. Larger companies have a tendency to track online prices of competitors more than smaller ones. The majority of those retailers that use software to track prices subsequently adjust their own prices to those of their competitors (78 %).

For more details on price tracking and price adjustments, see section B.

4.6

Pricing restrictions

.

(150)The frequency of online price adjustments depends on the sector, but daily and promotional price changes are reported as the most prevalent ones, as can be seen from the

figure B. 19

below.

Figure B. 19: Frequency of modifying online prices

based on the responses of retailers

(151)Price comparison tools report that daily online price changes are prevalent across sectors, whereas weekly price changes are also frequent. Seasonality plays a role for the category house and garden, and somewhat for sport and outdoor equipment, as well as clothing. Marketplaces indicate that almost one-third of prices change on a weekly basis. Most of them report daily changes for computer games, software and consumer electronics.

(152)Dynamic/personalised pricing, in the sense of setting prices based on tracking the online behaviour of individual customers, is reported as rather rare. 87 % of the retailers participating in the sector inquiry declare that they do not apply that type of pricing. No pattern in terms of size or profile can be established among the few retailers (2 %) explicitly declaring that they use or have used such dynamic/personalised pricing. Such pricing strategies may, however, be used more frequently in the future, as the technical ability to collect and analyse large amounts of customer-specific data increases possibilities to differentiate between customers and provide targeted, individualised advertisements or offers (see also section B.

5.1.3 The use of data in e-commerce and potential competition concerns

).

(153)In order to understand the pricing strategies of the different market players, the Commission requested information on various aspects of manufacturers' and retailers' pricing, and in particular on (i) the differences between online and offline pricing of goods; (ii) pricing in case of cross-border transactions; and (iii) agreements on pricing between manufacturers and retailers. This section reports on online and offline pricing. The findings on the latter two issues are set out in sections B.

4.3.2.6 Geo-filtering and cross-border price and offer differences

and B.

4.6 Pricing restrictions

respectively.

(154)Most hybrid retailers that responded to the specific question (80 %

) do not set different prices online and offline. Retailers that do so give diverse reasons for setting different prices. According to their explanation, the response depends among others on the business model of the company. Some respondents see their online business as ancillary to their offline activities. For instance, they sell online only to clear/liquidate stock and therefore set lower prices online. Others have the opposite business model. They are mainly active online and have a few showrooms to complement their online activities. Other respondents do not treat their online and offline activities interdependently and manage their online and offline businesses separately. Finally some of the respondents have a genuine omni-channel approach and consider these channels as parts of one single distribution system.