EUROPEAN COMMISSION

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Brussels, 4.2.2022

SWD(2022) 24 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

Cohesion in Europe towards 2050

Accompanying the document

COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS

on the 8th Cohesion Report: Cohesion in Europe towards 2050

{COM(2022) 34 final}

Chapter 9 The impact of cohesion policy

·EU funding for cohesion policy over the 2014-2020 period averaged EUR 112 a year per person in the EU and close to EUR 400 a year in some of the least developed regions.

·From 2014 to 2020, cohesion policy supported over 1.4 million enterprises. Projects selected indicate that this number could rise to over 2 million by the end of the programming period.

·Evaluations show that the support to enterprises produced tangible results. In the Czech Republic, for example, 90% of the companies supported by the “Knowledge Transfer Partnerships” programme have introduced product or process innovations.

·By the end of 2020, 11.3 million people had benefited from the flood protection measures co-financed by cohesion policy in the 2014-2020 period. When all selected projects are completed, 24 million people overall should be better protected.

·Thanks to cohesion policy, 1 544 km of railway lines had been laid or upgraded from 2014 to the end of 2020 and a further 3 500 km will be by 2023, once the projects selected are completed.

·Investment in the construction of new roads and the upgrading of others have increased road safety and reduced the number of accidents – the latter by 54% in Poznań and 74% in Lublin in Poland, for example – while reducing journey times and air pollution in cities.

·From 2014 to 2020, programmes helped 45.5 million participants to integrate into the labour market and receive education and training and 5.4 million people had been helped to find a job.

·Over the same period, the healthcare facilities constructed or improved with the support of the ERDF, mainly in the central and eastern Member States, provided an improved service for 53.3 million people.

·Some 15.2 million square metres of open space had been created or rehabilitated from 2014 to 2020 and the completion of the projects selected would bring this up to 53.4 million.

·By the end of 2023, it is estimated that the investment financed by cohesion policy in the 2014-2020 period will have increased GDP in some of the least developed regions in Europe by up to 5%.

·Macroeconomic model simulations show that in the long-run all EU regions benefit from cohesion policy. Every 1 euro spent on cohesion policy in the 2014-2020 period is estimated to generate a return, 15 years after the end of the period, of 2.7 euros in the form of additional EU GDP.

Contents

Chapter 9 The impact of cohesion policy

0. INTRODUCTION

1.

Part 1 Monitoring and Evaluation Evidence

1.1 PO1 SMARTER EUROPE

1.1.1.Progress in investment and monitoring of key outputs

1.1.2.Examples of thematic evaluation findings in Member States

1.2. PO2 GREENER EUROPE

1.2.1. Progress in investment and monitoring of key outputs

1.2.2. Evaluation findings

1.3 PO3 CONNECTED EUROPE

1.3.1. Progress in investment and monitoring of key outputs

1.3.2. Evaluation findings

1.4 PO4 SOCIAL EUROPE

1.4.1. Progress in investment and monitoring of key outputs

1.4.2. Evaluation findings

1.5 PO5 Europe Closer to citizens

1.5.1.Progress in investment and monitoring of key outputs

1.5.2. Evaluation findings

2. Interreg

3. Part 2 Macroeconomic impact of funding

3.1 2014-2020 Cohesion policy programmes

3.2. Impact of 2014-2020 cohesion policy

Figure 9.1 Cohesion policy funding per head of population by type of region, 2014-2020 (annual averages, EUR at current prices)

Figure 9.2 EU cohesion policy budget (2014-2020) by major Objective

Figure 9.3: EAFRD average aid intensity, 2007-2020

Figure 9.4: CAP average aid intensity, 2007-2020

Figure 9.5: Connecting Europe Facility funding for Cohesion and other countries by transport mode, 2014-2020

Figure 9.6 Impact of cohesion policy investment, 2014-2020, on EU GDP2014-2043

Map 9.1 Eligibility of regions for cohesion policy funding (ERDF + ESF), 2014-2020

Map 9.3: Horizon 2020 funding by NUTS 3 region, 2014-2020

Map 9.4 CAP EAFRD expenditure by NUTS 3 region, 2007-2020

Map 9.5 ERDF Cross-border cooperation programmes, 2014-2020

Map 9.6 Cohesion policy allocation 2014-2020, % of GDP of NUT 2 regions, yearly average

Map 9.7 Impact of the 2014-2020 cohesion policy programmes on GDP in NUTS 2 regions in 2023

Map 9.8 Impact of the 2014-2020 cohesion policy programmes on GDP in NUTS 2 regions in 2043

Table 9.1 ‘Smarter Europe’ indicators: 2023 targets and achievements up to end-2020

Table 9.2 ‘Greener Europe’ indicators: 2023 targets and achievements up to end-2020

Table 9.3 ‘Connected Europe’ indicators: 2023 targets and achievements up to end-2020

Table 9.4 ‘Social infrastructure indicators: 2023 targets and achievements up to end-2020

Table 9.5 ‘Europe closer to citizens’ indicators: 2023 targets and achievements up to end-2020

Table 9.6 Interreg indicators: 2023 targets and achievements up to end-2019

Table 9.7 Cohesion policy allocation by area of intervention, 2014-2020

0. INTRODUCTION

Cohesion policy is the EU’s main source of investment in economic and social development across the Union. It is financed by three funds, the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), the Cohesion Fund and the European Social Fund (ESF). The ERDF, the largest of the three, is allocated to regions (at the NUTS 2 level) on the basis of their GDP per head and other indicators, such as the unemployment rate, less developed regions, defined as those with a level below 75% of the EU average receiving the most, Transition regions, with a level between 75% and 90% of the average, the next largest amount, and more developed regions – the remaining ones – the smallest amount (

Map

9.

1

). In addition, some of the ERDF is also allocated to European trans-border cooperation (Interreg), providing support to border regions, large areas in the EU covering several countries, such as the Danube or Baltic Sea regions, and regions in different Member States adopting a joint approach to tackle common issues.

The Cohesion Fund, allocated at the national level, is restricted to Member States with Gross National Income (GNI) below 90% of the EU average and is limited to financing investment in transport, environmental infrastructure and energy. The ESF, the main source of finance for investment in people, is also allocated at the national level to Member States, taking account of their population, unemployment and levels of education. This was supplemented in 2014-2020 by the Youth Employment Initiative (YEI) to provide support to young people under 25 not in employment, education or training (NEETs) living in regions where youth unemployment was over 25% in 2012.

In 2014-2020, the investment financed by the three Funds was aimed at supporting 11 broad priorities, or Thematic Objectives:

-strengthening RTDI

-enhancing access to, and use and quality of, ICT

-enhancing the competitiveness of SMEs

-supporting the shift towards a low-carbon economy

-promoting climate change adaptation, risk prevention and management

-preserving and protecting the environment and promoting resource efficiency

-promoting sustainable transport and removing bottlenecks in key network infrastructures

-promoting sustainable and quality employment and supporting labour mobility

-promoting social inclusion, combating poverty and discrimination

-investing in education, training and vocational training for skills and lifelong learning

-enhancing institutional capacity of public authorities and efficient public administration

The ERDF was targeted at the first 7 objectives but also financed infrastructure investment in the other four. ,The first four objectives accounted for between 50% and 80% of total ERDF expenditure, depending on the level of regional development (more going on these objectives in the more developed regions). The ESF was concentrated on financing expenditure under the last four objectives, though it also supported (current) spending under the other 7.. The outbreak of Covid-19, however, was followed quickly by two Commission initiatives (CRII and CRII+) to allow governments substantial flexibility to divert unspent cohesion policy funding to finance pandemic-related expenditure, such as on medical equipment and support to jobs and businesses hit by the restrictions put in place to arrest the spread of the virus.

Map 9.1 Eligibility of regions for cohesion policy funding (ERDF + ESF), 2014-2020

This chapter is divided into two parts. First, it sets out the monitoring and evaluation evidence on the results of cohesion policy funding for the 2014-2020 period, examining the allocation of funding between broad investment objectives, the progress made in spending the funding allocated, the output and results so far achieved and the findings from evaluations carried out up to now by Member States. Note that the expenditure financed under the 11 Thematic Objectives listed above is reorganised under the 5 Policy Objectives (POs) for 2021-2027 so as to enable the allocation of funding in the two periods to be directly compared.

Secondly, it considers the impact of funding over this period on GDP across EU regions using a macroeconomic model to attempt to capture the full and wider effects, indirect as well as direct.

The chapter also includes a number of boxes on other EU initiatives and policies whose remits are close to cohesion policy, notably regional state aid, Horizon 2020, the Just Transition Fund, the Common Agricultural Policy and the Connecting Europe Facility.

1.Part 1 Monitoring and Evaluation Evidence

Some EUR 355 billion was allocated by the EU to cohesion policy for the 2014-2020 period, with national financing increasing this to EUR 482 billion. Overall, EU funding for cohesion policy over this period amounted to an average each year of EUR 112 for each person in the 27 Member States. The average, however, varied markedly between regions across the EU as well as between countries. It was largest per head of population in less developed regions in Hungary and Slovakia, at around EUR 390 and was just under EUR 380 in both Estonia and less developed regions in Portugal (

Figure

9.

1

). On the other hand, it was under EUR 200 in Italy and around EUR 150 in Romania and Bulgaria.

Figure 9.1 Cohesion policy funding per head of population by type of region, 2014-2020 (annual averages, EUR at current prices)

Note: Cohesion policy funding includes the ERDF, Cohesion Fund, ESF and YEI. The Cohesion Fund is assumed to be allocated evenly across countries in relation to population. The same is the case for the YEI and European Transnational Cooperation funding under the ERDF. Funding for interregional cooperation under the latter is excluded from the Figure. This was very small, amounting to much less than EUR 1 per person on average. Countries are ordered in terms of the funding going to less developed regions relative to their population and then by the funding going to transition and more developed regions per head of population, according to which is the largest.

Funding going to the Outermost regions, which is relevant for Spain, France and Portugal, is excluded, as is the funding going to the Northern sparsely-populated regions, which is relevant for Finland and Sweden. In each case, this amounted to EUR 33.6 per person living in these regions.

Source: DG REGIO calculations.

Funding per person in transition regions was around half or less of the average in less developed regions in most countries, while also varying between countries according to their level of GDP per head. Funding going to more developed regions was smaller again, though relatively large in relation to population in the regions concerned in Slovakia, Poland and Slovenia. In each case, this is partly because of the amounts received from the Cohesion Fund, which are assumed to be the same per person in these regions as in less developed ones. As in the case of the funding going to the transition regions, the amount varies markedly between countries, reflecting their relative levels of prosperity.

In terms of the kinds of investment financed, almost a third of EU funding went to pursuit of the Social Europe objective in support of inclusion measures and just over a quarter to Smart Europe in support of investment in R&D, innovation and competitiveness, while just under 20% went to both ‘Green Europe’ and ‘Connected Europe’ (

Figure

9.

2

).

Figure 9.2 EU cohesion policy budget (2014-2020) by major Objective

Note: The funding allocated to the 11 Thematic Objectives for 2014-2020 is approximately mapped to the 5 Policy Objectives for 2021-2027. The ‘Europe closer to the citizens’ objective covers a number of integrated territorial measures included under various Thematic Objectives and the funding involved can only be roughly estimated.

Source: Cohesion Open Data – https://cohesiondata.ec.europa.eu/d/aesb-873i

The monitoring of cohesion policy expenditure was strengthened significantly in the 2014-2020 period compared to the previous one (2007-2013). More detailed, and more structured, financial data are available three times a year, together with a more complete set of common output indicators for the support provided by the ERDF, ESF and Cohesion Fund and common result indicators for ESF support showing the direct achievements of expenditure. Transparency and accountability have also been improved by the regular publication of monitoring data on the ESI Funds Open Data Platform.

When interpreting the financial data and common indicators, it is important to bear in mind that

-Expenditure financed by 2014-2020 funding can continue up to the end of 2023, so that in many cases, projects or measures were still ongoing at the end of 2020, which the indicator values relate to, implying that the outcomes that are so far evident give a very incomplete picture of the full achievements of the programmes concerned.

-Much of the ERDF and Cohesion Fund expenditure is on infrastructure projects and on measures, such as support for RTDI, which take time to produce their full effects. The output and monitoring indicators, as well as the evaluations carried out so far, therefore, tend to understate the effects of the expenditure undertaken up to now, in many cases considerably.

-The focus here is on the long term strategic priorities set before the COVID-19 response was implemented in 2020 and 2021 under the Coronavirus Response Investment initiatives (CRII and CRII+). The main reason for this is that full information on the reprogramming involved is not yet available.

-The overview here does not cover the additional EUR 50 billion for Next Generation EU/REACT which the EU made available during 2021. Implementation of the investment funded by this is still at an early stage.

(The Commission presents annual reports to the EU institutions on the implementation of the 2014-2020 cohesion policy programmes under Article 53 of the Common Provisions Regulation. The 2021 report adopted in December 2021 and previous reports are available online.)

Box 9.1 Cohesion policy confronting the Covid crisis: a fast, flexible and effective response

|

When facing the socio-economic crisis caused by the Covid pandemic, cohesion policy has been the in the forefront of the EU response, responding, in particular, to the two main immediate effects of this unprecedented shock: the major strain on the healthcare sector and the substantial liquidity risk to business, notably small businesses, forced to cease their activities, with millions of jobs at stake, together with an irreversible loss of skills and capacity.

In record time, the European institutions adopted two new regulations– the two Coronavirus Response Investment Initiatives, enlarging the eligibility of cohesion policy funds and increasing the flexibility offered to programming authorities. Over EUR 20 billion was reallocated by the end of 2020 to secure vital personal protective equipment, ventilators and ambulances. Businesses were able to benefit from emergency grants and low-interest rate loans, which allowed them to stay afloat during lockdowns. New employment measures, in particular short-time work arrangements, were put in place to make sure people did not find themselves without income from one day to another. In parallel, simplification measures have been promoted, easing audit procedures and relaxing reporting deadlines, enabling Member States to cope with the workload by first addressing the urgent needs of the community, while reporting on the achievements at a later stage.

To assist with dealing with the pressure on public budgets, Member States were allowed exceptionally to keep EUR 7.6 billion in unspent cohesion policy funds in their national budgets and use it immediately for the worst affected sectors. 100% EU co-financing for a larger share of projects has been introduced and, again exceptionally, it became possible to finance completed projects that directly helped to tackle the crisis. 188 cohesion policy programmes made use of this possibility, accelerating the absorption of funds by disbursing an additional €12.6 billion.

The recovery process has been further consolidated through the introduction of the REACT-EU initiative, which has been the first to mobilise resources under Next Generation EU. Thanks to its high rate of pre-financing, Member States have already been able to start working on new projects to help medical institutions, business owners, employees and vulnerable people. This injection of EU funds will allow the resumption of projects previously halted in favour of emergency needs. Moreover, special attention has been given to green and digital priorities, which are essential for a smart, sustainable and resilient recovery, consistent with the EU’s broader political agenda.

REACT-EU resources are designed to target the geographic areas and cities most affected by the impact of the Covid pandemic, without being required to be broken down by category of region, so hence increasing the speed and effectiveness of the recovery process.

Lessons from the crisis have also been drawn in the delivery mechanisms of cohesion policy for 2021-2027. In particular, the Commission has been empowered to take implementing decisions for limited periods of time, if unexpected adverse economic events occur. The adaptability of the policy has also been reinforced, including through the mid-term review, enabling Member States to accommodate new challenges and unexpected events. Lastly, the effectiveness of smart specialisation strategies has been strengthened, allowing Member States and regions to further diversify their economies and so reduce their vulnerability to shocks.

Overall, cohesion policy has proved to be agile and effective in adapting rapidly to the crisis, providing Member States, regions and cities with a comprehensive and tailored toolkit to address the uneven territorial social and economic effects of the pandemic..

|

While the financial data and common output and result indicators used to monitor expenditure cover the whole EU, the evaluation evidence on the 2014-2020 period comes so far from the evaluations commissioned by national and regional Managing Authorities in Member States. This evidence, therefore, relates to the measures or projects carried out in individual countries or regions, or, in the case of Interreg programmes, in two or more Member States.

Accordingly, the evidence is inevitably specific to the countries or regions concerned and cannot necessarily be assumed to apply elsewhere. Nevertheless, in many cases, much the same findings on the effects of the measures supported emerge from evaluations carried out in different contexts, so it is reasonable to consider them applicable more generally.

Expenditure under each of the Policy Objectives is considered in turn below, in each case, examining:

I)the extent to which the funding available for the 2014-2020 period has been spent up to now, what it has been spent on and the immediate results according to the common indicators for which data are reported annually for national and regional programmes;

II)typical evidence from the evaluations so far carried out in Member States on the effects of the expenditure concerned on policy objectives.

1.1 PO1 SMARTER EUROPE

1.1.1.Progress in investment and monitoring of key outputs

In 2014-2020, EUR 96 billion of the ERDF for the period, or 27% of total cohesion policy funding, was devoted to ‘Smarter Europe’ objectives, for support to research, technological development and innovation (RTDI), ICT and SME competitiveness. Up to the end of 2020, the funding for the projects selected for support amounted to around 114% of the total EU allocation – i.e. more than the sum available (reflecting a policy of allowing for the likelihood that at least some projects will not actually go ahead) - while an estimated EUR 52 billion of funding, 54% of the total available, had been spent.

The common indicators give an indication of the immediate outputs from this expenditure as well as how these relate to the targets set. The indicators under the Smarter Europe objective show that over 610 000 enterprises received support up to the end of 2019 and that another 480,000 or so will receive support if the projects selected are completed (

Table

9.

1

). They also show that 17 500 enterprises receiving support had introduced new products and another 18 000 will do so by the end of 2023 if all projects selected are undertaken. They show, in addition, that the targets set are likely to be reached, or exceeded, by the end of 2023 in all cases, except for population with access to broadband. In this case, support is concentrated in Spain, Italy and Poland, where progress in implementation has been relatively slow in aggregate and so the population given broadband access amounted to only 46% of the 2023 target by the end of 2020. However, the target will almost be reached if the projects selected for funding are completed.

Table 9.1 ‘Smarter Europe’ indicators: 2023 targets and achievements up to end-2020

|

|

2023 target

|

Projects selected

|

Implemented, number and

% of target

|

|

The number of enterprises cooperating with research institutes

|

62 000

|

78 000

|

44 800

72%

|

|

The number of enterprises introducing new products to the market

|

30 250

|

40 600

|

23 900

79%

|

|

The number of researchers benefiting from RTD infrastructure

|

85 400

|

112 000

|

44 800

52%

|

|

The number of enterprises receiving support

|

1 780 000

|

2 011 000

|

1 442 333

81%

|

|

The number of jobs created in the enterprises supported

|

361 900

|

451 700

|

238 300

66%

|

|

New enterprises supported

|

178 000

|

195 000

|

124 900

70%

|

|

Population with access to broadband

|

11 900 000

|

11 550 000

|

5 518 000

46%

|

Source: Cohesion Open Data

https://cohesiondata.ec.europa.eu/d/aesb-873i

1.1.2.Examples of thematic evaluation findings in Member States

1.1.2.1.Support for knowledge transfer, business innovation and cooperation between enterprises and research centres

Much of the support for research and innovation has been directed to increasing collaboration between companies, particularly SMEs, and universities and other research centres. This has been achieved through both the creation of new links and the expansion of existing ones. Successful examples of support leading to increased collaboration of this kind are evident across the EU, such as in the Czechia where the measures financed greatly exceeded the targets for firms supported and cases of collaboration between companies and research centres. Some 70% of companies have launched further joint research initiatives after support came to an end, demonstrating the long-term sustainability of the links established.

Such sustainability is also evident in respect of the Germany-Netherlands Interreg OP where support has led to the creation and development of cross-border technology transfer networks, as well as in Austria, where measures supporting investment in technology and R&D in SMEs have resulted in increased knowledge transfer and strengthened the innovation environment. In addition, in Nordrhein-Westfalen, in Germany, support provided has led to a deepening of existing collaboration between enterprises and research centres and to the creation of new networks, which, as a consequence, has helped to increase the capacity of firms to enter new markets.

Direct support for R&D and innovation has boosted the capacity of enterprises to develop new products and processes across the EU. In Dolnośląskie in Poland, for example, the measures financed have increased R&D activities in SMEs, as well as strengthening employee competences and, in Śląskie, increasing the scale of operations, employment and profitability. In Germany, measures funded by the Sachsen OP led to new products and services being introduced by SMEs and existing products being improved, which, in turn, increased turnover and employment. In the Czech Republic, 90% of the companies supported by the “Knowledge Transfer Partnerships” programme have introduced product or process innovations. In the Czech Republic too, the financing provided to increase the availability of infrastructure for enterprises (the Real Estate programme) has enabled recipients to expand production, to innovate and to enlarge the number of products.

In many cases, support for RTDI has focused on furthering the pursuit of Smart Specialisation Strategies and on helping to develop a more innovative and competitive economy. This is the case, for example, in Wielkopolskie in Poland, where such support has helped to eliminate barriers to innovation, especially by increasing investment outlays and reducing the costs involved, while in Portugal, Valencia in Spain and Puglia in Italy, the companies supported have increased exports and .their participation in international markets.

Evidence from evaluations carried out on the 2007-2013 programmes, which have had longer to produce their effects, confirm these positive findings. in Latvia, for example, support for research institutes helped to improve cooperation with industry and to increase the active participation of researchers in international projects. A similar increase occurred in Poland as a result of the support provided under the Innovative Economy OP.

1.1.2.2.SME competitiveness

The support from the ERDF for R&D and innovation has the ultimate objective of increasing competitiveness and so the growth potential of regions and firms. Indeed, in the case of SMEs, the funding concerned often has the dual aim of increasing their capacity to innovate and of strengthening their competitiveness, especially in international markets. .This applies to the support going to companies in Portugal, Valencia and Puglia, mentioned above, where the investment financed has achieved both aims.

In Portugal, the support which was provided under the 2007-2013 programme led to growth in both national and international markets, while in Puglia, the measures financed in this earlier period resulted in a significant growth of exports.

In Poland, the more general support to SMEs for investment provided by the 16 regional OPs has led to an increase in productivity and exports, but has also helped to increase output and employment. Similarly, in Piemonte in Italy, support for the development of innovation poles over the 2010-2015 period led to increased value-added, productivity and employment, especially in manufacturing. In Thüringen, in Germany, the start-up fund and the growth fund created for SMEs in their first years have enabled firms to access additional capital and have led to an increase in their competitiveness and improved their access to new markets. In addition, the Thuringia Invest programme, designed to strengthen the competitiveness of SMEs, has accelerated their investment and/or led to larger projects being undertaken in 75% of cases

In Estonia too, there is evidence of the beneficial effects of the 2007-2013 programme in the form of the creation of a large number of start-ups in knowledge-intensive service sectors and an increase in the number employed, the return on sales and value-added per employee in the companies supported.

1.1.2.3 ICT development

Cohesion policy funding for digitalisation has led to the development of ICT products and services, including e-government ones by public authorities. For example, in Mazowieckie, in Poland, the implementation of the e-services supported has been followed by 68% of residents and 72% of businesses in the region making use of them. This, in turn, has increased the transparency of public sector activities and people’s awareness of them as well as helping to reduce the extent of digital exclusion among older people. This continued the support provided to ICT in the earlier period, when in Podkarpackie, financing from the ERDF helped to construct 59 km of broadband network, and 206 km of local-area networks and to modernise a further 240 km, mainly in rural areas.

Other examples of the effects of funding for ICT in the 2007-2013 period are, in Latvia, an improvement in the overall efficiency of the public administration through digitalisation and a reduction in the administrative burden on individuals and businesses and, in Prague, the expansion of public broadband and e-government services which has similarly led to the city’s administration becoming more efficient.

Box 9.2 State aid in support of regional development

Aim and scope of regional State aid

The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (Article 107(3)a and 107(3)c) provides for specific cases where State aid is considered compatible with competition in the internal market. Specifically, State aid must be exclusively aimed at promoting the economic development of outermost regions and areas where the standard of living is abnormally low or where there is serious underemployment or at facilitating the development of particular economic areas in the EU where aid does not significantly affect competition. These types of State aid are known as regional aid, regional aid schemes needing to form an integral part of a regional development strategy with clearly defined objectives.

For aid to be compatible with competition in the internal market, its adverse effects in terms of distorting competition and affecting trade between Member States must be limited and must not outweigh the positive effects to an extent that would be contrary to the common interest. The primary objective of State aid control in respect of regional aid is to ensure that aid for regional development and territorial cohesion does not adversely affect trading conditions between Member States to an undue extent.

As a general principle, Member States must notify regional aid to the European Commission, with the exception of measures that fulfil the conditions laid down in the General Block Exemption Regulation (GBER) for regional investment aid. The European Commission then assesses the aid notified according to the principles set out in the Guidelines on regional State aid. These were issued as part of an ongoing review of competition rules to ensure they are fit for an evolving market environment.

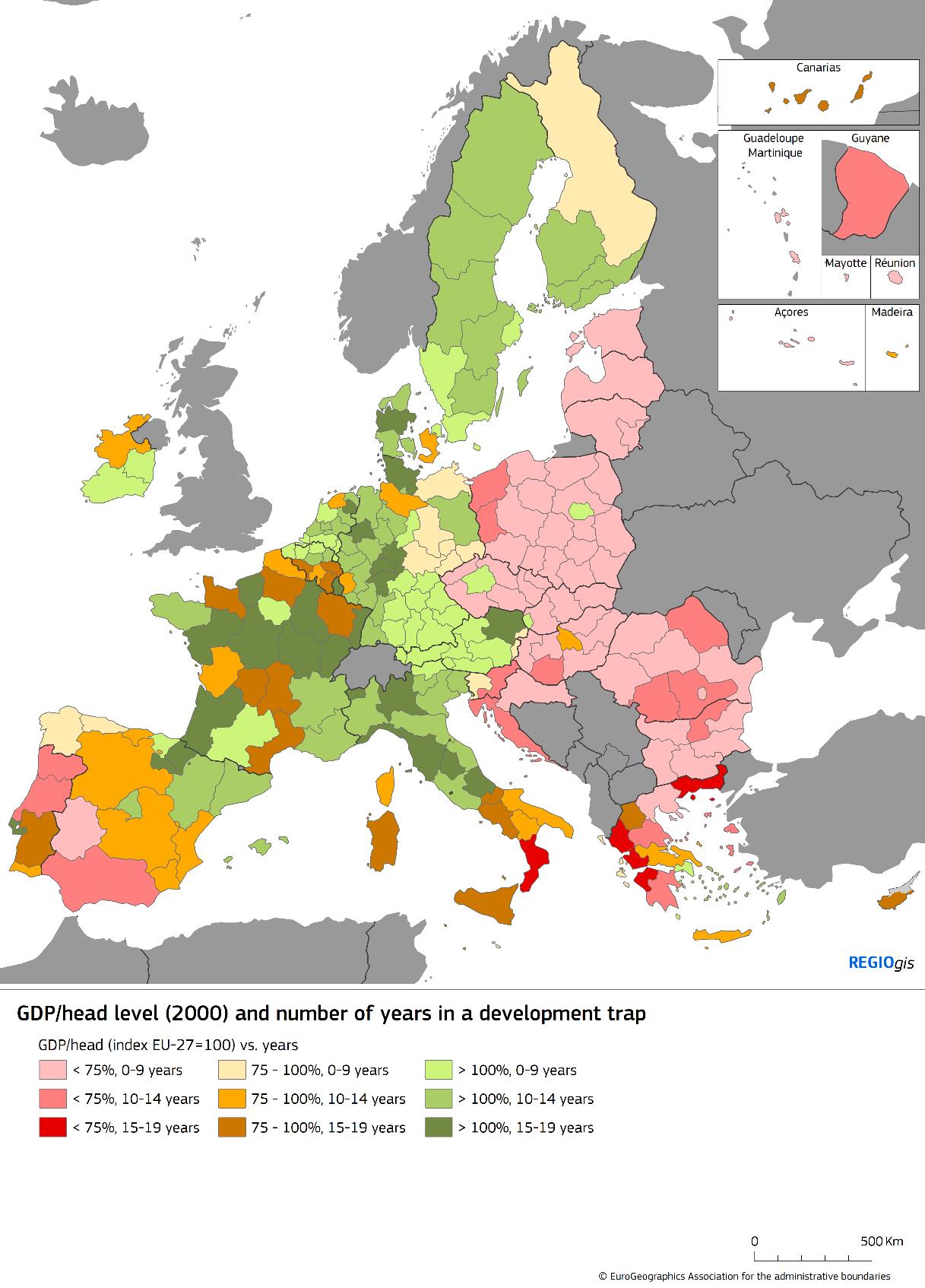

Types of area for regional aid

In accordance with the prescriptions of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, the Annexes to the Guidelines identify two types of area that qualify as a target for regional aid in the period 2021-2027 (

Map 9.2

):

·The ‘a’ areas which include the outermost regions, and NUTS2 regions where GDP per head in PPS is 75% of the EU27 average or less (based on the average of Eurostat regional data for 2016-2018).

·The predefined ‘c’ areas which include NUTS 2 regions formerly designated as ‘a’ areas in 2017-2020 and sparsely populated areas, i.e. NUTS 2 regions with fewer than 8 inhabitants per square km or NUTS 3 regions with fewer than 12.5 inhabitants per square km (based on Eurostat data on population density for 2018).

There is another category of ‘c’ areas, which is regions that a Member State may at its own discretion designate as being in nerd of support, though it has to demonstrate that they fulfil certain socioeconomic criteria (these are known as non-predefined ‘c’ areas). In this respect, the Guidelines state that the criteria used by Member States for designating ‘c’ areas should reflect the range of situations in which granting regional aid may be justified. The criteria should, therefore, relate to the socioeconomic, geographical or structural problems likely to be encountered in ‘c’ areas and should provide sufficient safeguards that granting regional State aid will not affect trading conditions to an extent contrary to the common interest.

The overall maximum coverage of ‘a’ and ‘c’ areas is set at 48% of the EU-27 population in 2018.

For the period 2022-2027, eligible ‘a’ areas are mostly concentrated in eastern European countries and regions in southern Europe; predefined ‘c’ areas are mostly in the northernmost part of Sweden and Finland and central Spain where they coincide with sparsely-populated regions and in some eastern European countries.

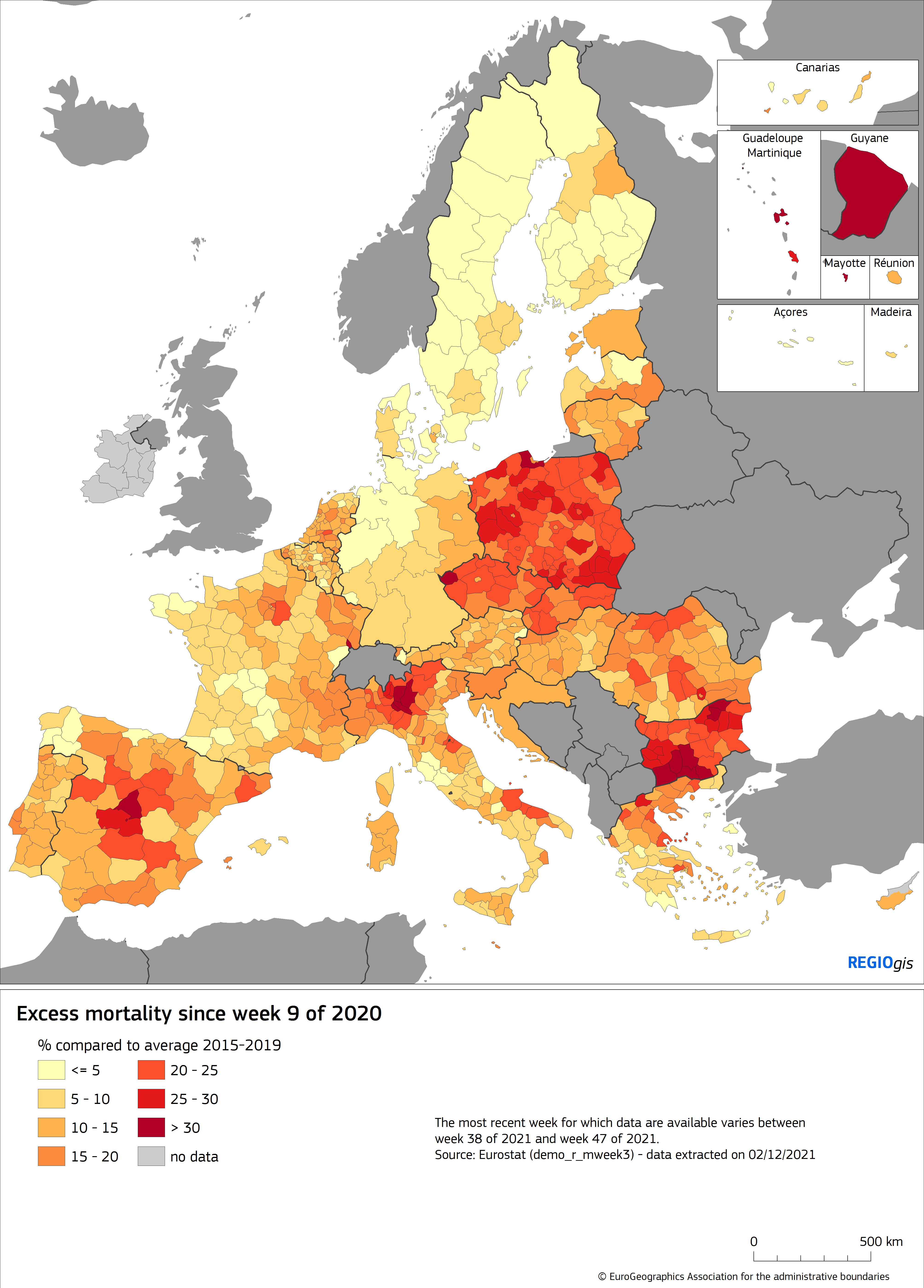

In response to the economic disturbance created by the COVID-19 pandemic, the European Commission has put in place targeted instruments, such as the Temporary Framework for State aid measures. The pandemic may have more long-lasting effects in certain areas than in others., though at this point in time, it is too early to predict the its long-term impact and to identify which areas will be particularly affected. The Commission, therefore, plans a mid-term review of the regional aid maps in 2023, which will take into account the latest available statistics.

Map 9.2 Regional State aid areas, 2022-2027

Box 9.3 The HORIZON 2020 EU R&D Framework Programme

|

Horizon Europe is the EU’s main funding programme for research and innovation with a budget of EUR 95.5 billion for the period 2021-2027. It is the successor to Horizon 2020 (2014-2020) which had a budget of nearly EUR 80 billion. The objective of both programmes is to support research excellence wherever it takes place via EU-wide calls for research proposals. The programmes do not use pre-determined national envelopes or otherwise differentiate their allocation of funding by regional, group or territory. Funding is far from being evenly distributed across EU Member States and regions (

Map

9.

3

) and is generally in line with their expenditure on R&D. However, the ‘Widening Participation and Spreading Excellence’ activities under Horizon Europe,, with funding nearly three times greater than the equivalent support under Horizon 2020, should help to build research and innovation capacity in the countries lagging behind.

The main recipient regions from Horizon 2020 tended to be those in the north-west of Europe where capital cities (Paris, Brussels) or major universities are located, whereas regions in the east of the EU received much lower levels of funding. Germany and France, on average, received less funding per inhabitant than other countries in the north-west, but some of the regions in these countries are among the largest recipients.

Map 9.3: Horizon 2020 funding by NUTS 3 region, 2014-2020

|

1.2. PO2 GREENER EUROPE

1.2.1. Progress in investment and monitoring of key outputs

Total EU funding of EUR 68 billion from the ERDF and Cohesion Fund was devoted to “Greener Europe” objectives in 2014-20020, targeting increases in energy efficiency and renewable energy, improvements in environmental infrastructure, the development of the circular economy, mitigation of, and adaptation to, climate change, risk prevention, biodiversity and clean urban transport. The funding represents 19% of the total available under cohesion policy for the period.

At the end of 2020, funding for projects selected under these objectives exceeded the EU financing available by around 112 %, while an estimated €29 billion (42% of the total EU amount allocated) had been spent on investment projects.

Investment in sustainable energy was supported in the period in nearly all Member States, while that on environmental infrastructure (to improve water supply, wastewater treatment and waste management) and on risk prevention is concentrated mainly in developing Member States in eastern Europe and less developed and transition regions in the southern EU. Investment in clean urban transport (on metro lines and tramways) is supported in only a small number of countries. The common indicators reported relate to the same groups of countries and regions.

The indicators show, for example, that 11.3 million people had benefited from the flood protection measures supported by the end of 2020, 41% of the target for 2023, and that overall 42 million would benefit if the projects selected were all completed (implying that the projects still to be completed cover, on average, a much larger number of people than those already undertaken) (

Table

9.

2

).

Table 9.2 ‘Greener Europe’ indicators: 2023 targets and achievements up to end-2020

|

|

2023 target

|

Selected projects

|

Implemented, number and

% of target

|

|

Number of households with improved energy consumption classification

|

600 000

|

663 000

|

359 400

60%

|

|

Decrease of annual primary energy consumption of public buildings (gigawatt /hours)

|

6 480

|

7 069

|

1 892

29%

|

|

Renewables: Additional capacity of renewable energy production (megawatts)

|

6 618

|

7 404

|

2 734

41%

|

|

Estimated annual decrease of greenhouse gasses (million tonnes CO2 equivalent)

|

20.8

|

23.4

|

4.4

21%

|

|

Total length of new or improved tram and metro lines (km)

|

478

|

542

|

137

29%

|

|

Population benefiting from flood protection measures

|

27 700 000

|

42 000 000

|

11 300 000

41%

|

|

Additional population served by improved water supply

|

14 900 000

|

19 500 000

|

3 500 000

24%

|

|

Additional population served by improved wastewater treatment

|

600 000

|

663 000

|

359 400

60%

|

Source: Cohesion Open Data

https://cohesiondata.ec.europa.eu/d/aesb-873i

The indicators also show that, for many of them, outcomes at the end of 2020 were very much lower than the targets set (only 21% of the target in the case of the reduction in GHG emissions). This, in part, reflects the relatively slow implementation of projects, as implied by the relatively low rate of expenditure, but it also reflects the fact that the projects concerned predominantly consist of investment in infrastructure that takes several years to plan and several further years to carry out. It is only when the construction is completed and the infrastructure is operational that outcomes are reflected in the indicators.

Two other factors might also play a role. The issue of the capacity of the environmental bodies concerned to secure funds, manage and implement multi-annual investments has been raised in evaluations for previous periods. More technically, some of the green indicators are being widely used for the first time in 2014-2020, which might mean there are delays in reporting on them (learning effects). The experience at the end of 2007-2013 was that significant achievements were reported for comparable indicators in the last two years of expenditure on projects (2014 and 2015). Indeed, the figures for projects selected suggest that if these are completed, then the targets set for 2023 will be met for four of the environmental indicators. However, for the indicator on reductions in GHG emissions, the two on energy efficiency and the one on renewables, there is a risk that outcomes will fall short of targets, though substantial achievements are still likely to be made.

Box 9.4 Just Transition Fund

|

The Just Transition Fund (JTF), as part of the Just Transition Mechanism (JTM) is one of the EU’s key instruments set up to respond to the effects of the transition towards climate neutrality by 2050. Reaching this objective will require a transformation of both society and the economy Some Member States and regions , however, are likely to be more affected than others and the JTM is crucial to avoiding regional disparities increasing further and to ensure that no one is left behind. It is composed by three pillars: 1) the Just Transition Fund, 2) a dedicated Just Transition Scheme under InvestEU designed to pull in private investment and 3) a Public Sector Loan Facility to leverage additional public investment in cooperation with the European Investment Bank.

The JTF is implemented under shared management and is incorporated in cohesion policy. Though it does not contribute per se to the transition towards climate neutrality. Its objective is to alleviate the socio-economic costs resulting from tis. While all Member States could benefit from the JTF, support is focused on regions that are most likely to be affected by the transition, notably those that still rely heavily on mining and extraction activities (especially coal, lignite, peat and oil shale) and GHG-intensive industries. Some of these activities will need to be phased out or transformed to be more sustainable, and the JTF will be crucial in helping to diversify the local economies and alleviate the adverse effect on employment.

The fund is endowed with EUR 17.5 billion (at 2018 prices), of which: EUR 7.5 billion will be financed from the EU budget for 2021-2027 and EU 10 billion from the European Recovery Instrument within Next Generation EU, the latter being made available from 2021 to 2023.

In addition, Member States may, on a voluntary basis, transfer resources from their national allocations under the ERDF and the ESF plus to the JTF, provided that the total amount transferred does not exceed three times the JTF allocation. Spending from the EU budget will be supplemented by national co-financing according to cohesion policy rules. Overall, therefore, the Fund is expected to mobilise around € 55 billion of financing for investment.

The JTF will support productive investment in SMEs and the creation of new firms. It may also support investment in areas such as RTDI, environmental rehabilitation, clean energy, upskilling of workers, job-search assistance and the active inclusion of jobseekers, as well as the transformation of existing carbon-intensive installations, when these investments lead to substantial cuts in emissions and job protection.

The governance of the JTF and, more generally, the JTM is built on the Territorial Just Transition Plans (TJTPs) that Member States need to prepare in cooperation with relevant stakeholders and the European Commission. The plans are intended to identify eligible areas, corresponding to NUTS 3 regions or parts of them, which are affected most by the transition. The plans detail, for each area, an assessment of the needs and the socioeconomic challenges, linked to the conversion or closure of activities involving high GHG intensity, and the adaptation to the resulting changes in the labour market.

The preparation of the TJTPs is being guided by the analysis carried out by European Commission in the 2020 country reports, assessing the situation in the areas expected to be the most affected. The Commission is also channelling support to Member States for the preparation of the TJTPs, and a Just Transition Platform has been created to provide technical assistance and advice to help ensure that the best use is made of the JTM. In addition, each pillar of the JTM provides assistance for preparing operations that are eligible.

|

1.2.2. Evaluation findings

1.2.2.1. Promoting energy efficiency and use of renewable sources and reducing greenhouse gas emissions

In 2014-2020, support for the shift towards a low-carbon economy in the EU focused on energy production from renewables and improving energy efficiency in enterprises and public and private buildings. While it is clear that in many countries significant expenditure was allocated to projects of these kinds, evidence on the impact of the measures concerned is yet limited because projects are still underway and results take time to materialise.

For example, in Nordrhein-Westfalen, the focus of investment support was on the development of new renewable technologies, which means that the results in terms of the energy sources used are so far relatively limited and visible only in the medium-to-long term. Indeed, in many German Länder , the global visible effects are limited because of emphasis on the use of the ERDF to finance innovative projects.. This is, for example, the case in Bayern, where such an emphasis almost inevitably means that tangible outcomes in terms of energy use or improvements in efficiency are not yet evident. In addition, in a number of cases, funding went to increasing energy efficiency in SMEs and although there is evaluation evidence that this has been effective in the firms concerned (such as for instance in Rheinland-Pfalz), the global visible effects are limited because of the small size of firms supported.

Promoting energy efficiency and use of renewable sources was also one of the objectives of many Interreg programmes. Under the Germany-Netherlands Interreg OP, for example, pilot projects were undertaken to reduce CO2 emissions and this has helped raise awareness of the opportunities for trans-border cooperation as regards product and process innovation.

1.2.2.2. Promoting sustainable multimodal urban mobility

Support from cohesion policy programmes across the EU in 2014-2020 went to the development or improvement in transport systems in cities to make them more environmentally-friendly, more accessible and safer. In Poland, for example, EU-funded investment in public transport projects helped to improve traffic flow and road safety in cities, as well as the connections between different modes of transport, while reducing air pollution. The evaluation of a new tramway in Florence, for example, found that it has strengthened the attractiveness of the city as a business centre and, by speeding up journey times, has made it more possible for people to commute from the peripheral areas served to the centre. By the same token, it has reduced the use of private cars and increased that of public transport.

Similarly, in the 2007-2013 period, ERDF support helped to create a more sustainable and integrated urban environment in Prague by improving barrier-free access to the metro system, improving bus and metro services and constructing a network of cycle path, while In Hungary, investment in intelligent transport systems helped to improve environmental sustainability.

1.2.2.3. Supporting adaptation to climate change and preventing disasters

In a number of countries, support for investment focused on strengthening resilience to natural disasters and improving systems for managing the risks involved. In Romania, projects funded have helped to improve the monitoring of severe weather events and so to limit floods, reduce the damage from these and provide appropriate emergency equipment. In the Polish region of Świętokrzyski, funding have helped to develop a disaster recovery system and improve the Volunteer Fire Brigade.

Funding was also allocated to this broad area under many Interreg programmes. In particular, joint measures for managing climate change were implemented under the Italy-France (Maritime) programme and the joint risk management projects undertaken under the Czech Republic-Poland programme increased the capacity of the authorities concerned to tackle crises and emergency situations.

1.2.2.4. Preserving and protecting the environment

In several countries, funding also went to projects to protect and preserve the natural heritage, which, along with supporting the cultural heritage, have helped to boost tourism, such as in the Polish region of Malopolskie. At the same time, many projects with a similar aim were financed by Interreg. These have helped to create a new environmental management system in the Northern Periphery and Arctic area, to protect cross-border ecosystems through developing green infrastructure in the Italy-France Interreg (Maritime) area and to boost the development of the circular economy through the more efficient use of natural resources under the France-Belgium-Netherlands-UK programme.

In the 2007-2013 period too, there are many examples of the support provided improving the environment, such as in Slovakia and Lithuania, where investment helped to improve air quality, in Estonia, where investment in modernising the water supply network gave 454 000 people access to clean drinking water, in Friuli, Venezia, Giulia in Italy, where support led to an increase in the accessibility of natural areas and improved the conservation of flora and fauna, and in Romania., where support for environmental investment increased the attractiveness of the country as a tourist destination.

Box 9.5 The Common Agricultural Policy

|

About 8.8 million people worked in agriculture in 2019 which corresponds to just under 5% of total employment in the Union. While employment in agriculture is generally less than 3% in the most developed EU countries, it remains a big employer in others, particularly in Romania, where it accounts almost one person in every four employed (23% in agriculture, hunting and related service activities in 2019).

Within the EU, the farming sector operates under the common agricultural policy (CAP). The objectives of the CAP in the 2014-2020 period (which has been extended to cover the years 2021 and 2022) are to support farmers and improve agricultural productivity, to ensure a stable supply of affordable food and that farmers can make a reasonable living, and to keep the rural economy alive by promoting jobs in farming, agri-food industries and associated sectors. The CAP includes the following measures:

-income support through direct payments to ensure income stability;

-market measures to deal with difficult market situations such as a sudden drop in demand due to a health scare or a fall in prices as a result of a temporary oversupply on the market;

-rural development measures to address the specific needs and challenges facing rural areas.

The CAP is financed through two funds which are part of the EU budget:

-the European agricultural guarantee fund (EAGF) provides direct support and finances market measures. It is referred to the “first pillar” of the CAP.

-the European agricultural fund for rural development (EAFRD) finances rural development support. It is referred to the “second pillar” of the CAP.

The EAFRD is aimed at improving the competitiveness of agriculture, encouraging sustainable management of natural resources and action in response to climate change and achieving a balanced territorial development of rural economies and communities

. It helps rural areas in the EU to respond to a wide range of challenges and opportunities that face them in terms of economic, environmental and social development.

The main beneficiaries of the EAFRD are located in the eastern and southern EU, though also in Ireland and some regions of France, Finland and Sweden (

Map 9.5

).

Map 9.4 CAP EAFRD expenditure by NUTS 3 region, 2007-2020

In general, aid intensity under the EAFRD is higher in less developed regions (averaging EUR 42 per inhabitant each year between 2007 and 2020) than in transition regions (EUR 27 per inhabitant) and more developed regions (EUR 12) (

Figure 9.3

). Aid intensity under the first pillar of the CAP is much higher, and it is highest in transition regions (EUR 119 per inhabitant ), followed by less developed regions (EUR 103) and more developed regions (EUR 52) (

Figure 9.4

).

Figure 9.3: EAFRD average aid intensity, 2007-2020

Source: DG AGRI, EUROSTAT and DG REGIO calculations.

Figure 9.4: CAP average aid intensity, 2007-2020

Source: DG AGRI, EUROSTAT and DG REGIO calculations.

|

1.3 PO3 CONNECTED EUROPE

1.3.1. Progress in investment and monitoring of key outputs

Financing of EUR 64 billion from the ERDF and Cohesion Fund was allocated to the “Connected Europe” objectives in 2014-2020, targeting improvements in rail and road networks and other strategic transport goals This represented 18% of total cohesion policy funding for the period.

By the end of 2020, projects selected in pursuit of these objectives exceeded the EU funding available by around 14 %, while an estimated €37 billion of such funding (58% of the total available) had been spent on investment.

The investment concerned was mainly in the less developed Member States (those in receipt of the Cohesion Fund) and in less developed and transition regions elsewhere. The indicators show that just under 2 400 km of new roads had been constructed by the end of 2020, most of them on the TEN-T, and another 6 000 km had been upgraded (

Table

9.

3

). In both cases, this amounts to around two-thirds of the targets set for 2023 while the completion of the projects selected would mean the lengths of road concerned exceeding the targets substantially.

Table 9.3 ‘Connected Europe’ indicators: 2023 targets and achievements up to end-2020

|

|

2023 target

|

Selected projects

|

Implemented, number and

% of target

|

|

Total length of reconstructed or upgraded railway line (km)

|

5 260

|

4 590

|

1 540

29%

|

|

Of which TEN-T

|

3 640

|

3 051

|

1 080

30%

|

|

Total length of newly built roads (km)

|

3 727

|

5 078

|

2 382

64%

|

|

Of which TEN-T

|

2 500

|

3 530

|

1 680

67%

|

|

Total length of reconstructed or upgraded roads (km)

|

11 220

|

15 390

|

6 036

54%

|

|

Of which TEN-T

|

870

|

918

|

727

84%

|

Source: Cohesion Open Data

https://cohesiondata.ec.europa.eu/d/aesb-873i

On the other hand, the output of projects for upgrading the rail network up to the end of 2020, both those on the TEN-T and others, was well below the 2023 target, which is more typical of large scale multi-annual infrastructure investments, which usually need a significant amount of time to be completed (as in the case of the green investments above). However, in this case, the figures for projects selected suggest that the targets will not be achieved, which continues a long-term tendency evident in earlier periods for rail projects to experience more difficulty in being completed than road projects.

1.3.2. Evaluation findings

1.3.2.1. Support for enhancing mobility

Support for improving mobility in 2014-2020 was centred mainly on developing road and rail networks. This is particularly the case in Poland, where evaluations have verified that the objectives of the investment involved have largely been achieved. The construction of new roads and the upgrading of others have, therefore, improved road safety, reduced the number of accidents (in Poznań, by 54% and in Lublin, by 74% for instance), increased average vehicle speeds and shortened journey times, as well as reducing road noise and air pollution in cities. Investment in railways has also increased the capacity of the network, speeded up journey times and improved the connections between major cities and between the main economic centres. As a result, it has led to increased use of the railways in the country, though the quality of service still needs to be improved to attract more people.

As in the case of environmental infrastructure, transport projects typically extend over lengthy periods of time and many span two or even more programming periods. Moreover, since they tend to be part of networks, forming perhaps a section of a motorway or railway line, it is often the case that their effects cannot be fully assessed until other sections have been completed and the network as a whole is fully operational, which can take many years.

A number of evaluations of support for transport investment have, therefore, extended over the 2007-2013 period as well as the 2014-2020 one. In Estonia, the investment in railways undertaken in the two periods has improved the quality of rail travel, reduced journey times and led to the increased use of trains, expanding passenger numbers. The same is the case in Wales, where 70 stations in the East Wales and the Valleys regions were improved through ERDF support over the two periods.

Evaluations carried out in the 2014-2020 period on the effects of investment in the previous period show similar effects. They indicate a reduced number of road accidents in Poland and fewer traffic bottlenecks from investment in new motorways and improved safety and reduced journey times in Latvia and Spain from the construction of new roads and upgrading of existing ones. In Latvia too, the modernisation of the rail network financed from EU funds made trains more competitive for both passenger and freight transport, increasing the use by both, while in Spain, modernisation and general improvements led to significantly reduced travel times, especially on high-speed train routes, and to increased passenger numbers.

|

Box 9.6 The Connecting Europe Facility

The Connecting Europe Facility (CEF) is an important funding instrument for EU transport policy, complementing the ESI funds by supporting cross-border projects and those to remove bottlenecks or build missing links on sections of European transport, energy and digital networks.

Over the 2014-2020 period, CEF funding amounted to EUR 22.6 billion, divided roughly equally between the Cohesion countries and other Member States, funding averaging EUR 95 per inhabitant in the former, almost three times more than in the latter (EUR 33) (

Figure 9.5

). In both groups, the bulk of funding went to rail transport. In the non-cohesion countries, the funding for air and inland shipping was more than in the Cohesion countries.

Figure 9.5: Connecting Europe Facility funding for Cohesion and other countries by transport mode, 2014-2020

Source: INEA, DG REGIO calculations.

In 2021-2027, the CEF will continue to fund major transport projects as well as digital and energy ones.

·It will have an overall budget of EUR 33.71 billion (at current prices), EUR 25.81 billion going to transport, including EUR 11.29 billion for Cohesion countries.

·For transport, it will help networks to become more interconnected, multimodal and safe by investing in the development and modernisation of railway, road, inland waterway and maritime infrastructure.

·Priority will be given to further developing the trans-European transport network (TEN-T), focusing on missing links and cross-border projects with an EU added-value. EUR 1.56 billion will go to financing major rail projects between Cohesion countries.

|

1.4 PO4 SOCIAL EUROPE

1.4.1. Progress in investment and monitoring of key outputs

Total funding of EUR 111 billion, mainly from the ESF and YEI but also from the ERDF (for infrastructure and equipment), was devoted to ‘Social Europe’ objectives targeting support for employment and labour market integration, education and training and social inclusion. Funding represents 31% of the overall cohesion policy budget for 2014-2020.

By the end of 2020, EU funding for the projects selected under Social Europe was 1% more than the amount available, while an estimated €60 billion, or 54% of the EU allocation, had been spent on the projects concerned.

The common indicators cover all EU Member States in respect of the ESF and the 20 countries for the YEI where this applies . They show that up to the end of 2020:

-there were 45.5 million participants in the programmes supported, including nearly 17.3 million who were unemployed and 17.2 million who were inactive (in the sense of not actively seeking employment);

-5.4 million participants in EU-funded schemes had found a job;

-48% of participants had a low level of education (only up to compulsory schooling or less); and 15% were migrants, had a foreign background, or were from ethnic minorities;

-overall there were slightly more women (53%) than men among participants.

Three common indicators – one relating to investment in improving health services, one to investment in childcare and education facilities and one to investment in tourist and cultural infrastructure – are used to track the outcomes of ERDF support for Social Europe objectives (

Table

9.

4

). The investment concerned on health and education is mainly undertaken in less developed and transition regions in eastern and southern Member States, though the indicator for investment in education is dominated by Italy. Support for investment in tourist and cultural sites is more widely spread and the indicator covers 17 Member States, with 6 (Poland, Italy, Spain, Portugal, France, and Hungary) predominating.

Table 9.4 ‘Social infrastructure indicators: 2023 targets and achievements up to end-2020

|

|

2023 target

|

Selected projects

|

Implemented

% of target achieved (2019)

|

|

Population covered by improved health services

|

66 470 000

|

88 880 000

|

53 307 000

80%

|

|

Capacity of supported childcare or education infrastructure (students)

|

17 800 000

|

25 333 000

|

19 757 000

111%

|

|

Increase in expected number of visits to supported sites (cultural, natural heritage and attractions)

|

64 000 000

|

69 950 000

|

25 360 000

40%

|

Source: Cohesion Open Data

https://cohesiondata.ec.europa.eu/d/aesb-873i

Up to the end of 2020, the health service facilities constructed covered 53.3 million people, already 80% of the target for 2023, and if projects selected for funding go ahead, then some 88.9 million will be covered by improved services, well above the target. Investment in childcare and education infrastructure had already improved or increased capacity for 19.8 million children or students by the end of 2020, well above the target, and if the projects selected are completed, this will increase to over 25 million. The outcome of investment in tourist and cultural sites is more modest in relation to the target, with an increase in visitor numbers to the sites concerned of 25.4 million by end-2020, only40% of the target for 2023. In this case, however, the dramatic effect of the Covid-19 pandemic might well see visitor numbers fall well short of the target.

Indeed, the pandemic has already had a massive effect on tourism and visits to cultural sites and put a significant strain on healthcare facilities. There has been a large net increase in planned allocations to health services, but it is not yet clear to what extent the response to the pandemic has also led to the investment originally planned for strategic improvements in the capacity of the services being diverted away to cope with the increased numbers requiring care.

1.4.2. Evaluation findings

1.4.2.1.Support for the employability of the non-employed

A large proportion of the ESF in 2014-2020 has gone to helping people, especially young people, to find work, the measures funded, often being combined into a tailor-made support package and taking the form of training programmes, traineeships and work experience. A number of evaluations find that the chances of a person being employed are increased significantly by participation in such measures. In Italy, for example, traineeships supported in Marche increased employment rates among participants by 13-15 percentage points 12 months after the traineeship ending as compared with a comparable group of non-participants (i.e. the control group). The same is true of voucher schemes in Piemonte, where 16 months after using them, 41% of participants were in employment as against 30% for the control group.

Similarly, in Germany, support for measures to help integrate the non-employed into the labour market, especially the long-term unemployed led, by the end of 2019, to 43% of participants being in employment 15 months afterwards, 10 percentage points more than for non-participants. In Poland, measures targeted at young people are found to have increased the chances of the long-term unemployed, the low educated and those from villages and rural areas finding a job.

The funding provided in Poland also helped participants to improve their entrepreneurial skills, 14% of them starting their own business within 6 months of receiving training. Other successful examples of ESF measures leading to the creation of new businesses are in Śląskie, in Poland, where support was found to be crucial to the establishment of new start-ups and to their chances of survival (it is estimated that without support 45% start-ups would not have been established), and in Piemonte in Italy, where new businesses supported had a 10 percentage point higher probability of being in operation 4 years after being formed than non-supported ones

1.4.2.2 Support for the adaptation of employees and enterprises to change

ESF financing has also gone to improving the skills of those already in work, as well as of entrepreneurs, so that they are able to adapt better to changing market conditions. In Sachsen-Anhalt, in Germany, the training funded improved the labour market situation of employees, 48% of participants performing an activity requiring more qualifications afterwards and over a third being given more responsibilities. In Thüringen, the support given to SMEs to recruit skilled workers from abroad led to firms being able to employ more of them.

1.4.2.3.Support for active inclusion

The ESF was also targeted at helping the vulnerable and disadvantaged to find work. In Asturias, in Spain, the ‘Integrated Activation Pathways’ scheme was found not only to increase the chances of vulnerable people finding a job but also to reduce markedly their risk of suffering a mental disorder (this being cut by around 45% after participation in the scheme). In Toscana, in Italy, measures tailored to the needs of people with disabilities and other disadvantaged groups, led, between October 2018 and November 2019, to 20% of recipients having a job one year after receiving support.

1.4.2.4. Support for healthcare infrastructure and services

In many of the less developed Member States, a significant part of the ESF went to support of health services and this was complemented, in some cases, by ERDF investment in buildings and equipment. A number of evaluations found that the projects concerned increased access to healthcare and improved its quality. In Lithuania, for example, the projects funded were found to have helped to reduce mortality from cardiovascular diseases and the suicide rate.

1.4.2.5. Support for good quality education

Measures to improve the quality of education and increase access to schooling were included in many ESF programmes, especially in less developed Member States and regions. In Thüringen, in Germany, measures supporting the active participation of young people in learning were found to have reduced early school leaving and improved the integration of migrants, as well as attitudes towards school. The training of teachers also facilitated the development of new methods of communication and conflict resolution.

In Lithuania, where support was targeted at higher education, it led to universities becoming more internationalised, with foreign students accounting for 8% of the total and around 1 600 domestic students spending part of their studies abroad.

1.4.2.6. Support for transition from education to work

EU funding was also directed at improving the links between education and the labour market, to ensure closer correspondence between teaching, qualifications and employer needs. Measures to strengthen vocational education in Podlaskie, in Poland, helped students to choose suitable courses, increased cooperation of VET schools with employers and improved teachers’ competences in advising on career choices. In Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, in Germany, measures to facilitate the transition from education into work involved local entrepreneurs identifying suitable companies for visits and work placement, so helping students discover whether occupations fitted their skill-sets and interests.

In Marche, in Italy, the technical training courses supported increased the chances of participants being in employment 12 months after, especially women. In Piemonte too, participation in the VET courses receiving ESF support led to a higher probability of being in work afterwards (up to 20 percentage points higher than for non-participants).

1.4.2.7. Support for culture and sustainable tourism

In addition to providing labour market support, significant cohesion policy funding also went into preserving cultural sites and encouraging sustainable tourism. Evaluations have identified a number of instances where support produced positive results. These include investment in safeguarding the archaeological site at Pompei and improving accessibility, which helped to increase visitors by 62% between 2012 and 2019, directly adding some 1.9 million to their number. They also include investment in natural and cultural assets in Świętokrzyskie, which has led to the creation of an integrated network of tourist sites in the region.

Projects to preserve cultural sites and strengthen the cultural heritage have been important in furthering cross-border cooperation too, such as under the Bayern- Czech Republic Interreg programme and under the Estonia-Latvia programme.

1.5 PO5 Europe Closer to citizens

1.5.1.Progress in investment and monitoring of key outputs

Unlike the other Policy Objectives, ‘Europe Closer to citizens’ cannot easily be matched to the Thematic Objective classification used for the 2014-2020 period. Nevertheless, investment in Community-led local development (CLLD), support for Integrated Territorial Investment (ITI) and other territorial measures relating to urban regeneration in particular, which form a large part of this Policy Objective and which were funded under various Thematic Objectives, can be tracked.

Overall EU support amounting to EUR 31 billion from the ERDF, ESF and Cohesion Fund is estimated to have been devoted to ‘Europe Closer to Citizens’ for the period, just under 10% of the overall cohesion policy budget.

At the end of 2020, projects selected under this Objective entailed EU funding of EUR 27.5 billion, 11% less than the amount allocated, while an estimated €12 billion, 39% of the allocation, had been spent on investment. This is less than in the case of the other Policy Objectives, reflecting the fact that much of the investment concerned involves mobilisation of local communities and/or the formulation of development plans involving a number of different sectors or aspects, which tend to increase the time needed for carrying it out.

The common indicators show that 15.2 million square metres of open space had been created or rehabilitated through the investment undertaken up to end-2020 and that if the projects selected are completed and deliver what they plan, this will be increased to 53.4 million by the end of 2023 (

Table

9.

5

). They also show that, although the buildings constructed or renovated in the urban areas supported amounted to only 30% of the target in terms of the space involved, the target will be exceeded if the projects selected are completed.

Table 9.5 ‘Europe closer to citizens’ indicators: 2023 targets and achievements up to end-2020

|

|

2023 target

|

Selected projects

|

Implemented

% of target

|

|

Population living in areas with integrated urban development strategies

|

42 695 000

|

44 714 000

|

25 279 000

59%

|

|

Open space created or rehabilitated in urban areas (sq. metres)

|

39 910 000

|

53 427 000

|

15 221 000

39%

|

|

Public or commercial buildings built or renovated in urban areas (sq. metres)

|

2 403 000

|

3 075 000

|

716 000

30%

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Cohesion Open Data

https://cohesiondata.ec.europa.eu/d/aesb-873i

1.5.2. Evaluation findings

1.5.2.1. Support for urban development and regeneration

A deliberate effort was made in the 2014-2020 programming period both to involve local communities in the design and implementation of measures to develop and regenerate urban areas and to make them more socially inclusive. At the same time, a conscious attempt was made to ensure that the measures concerned were properly integrated into a development strategy which took explicit account of the interaction between measures and the potential complementarity, and reinforcing nature, of their effects. Two cross-cutting instruments were created as part of these efforts: Community-led local development (CLLD) and Integrated Territorial Investment (ITI). Although, because of the nature of the investments concerned and the long time-scale over which their results are likely to become visible, there is limited evidence so far on their effects. Nevertheless, a number of evaluations have indicated that they have been implemented successfully in many places across the EU.

For example, in Poland, local development strategies in Podlaskie were found to have been formulated with the close involvement of local people and organisations, and that many who had not previously applied for EU funding had submitted projects for CLLD funding, with a focus on how their projected results would further the overall strategy. In Świętokrzyskie, the ITI approach to policy-making in respect of investment in natural and cultural assets was found to have worked efficiently and effectively and to have helped increase the attractiveness of the areas concerned, reducing the pace of the decline in biodiversity and increasing the opportunities for tourism.

In the Netherlands, the ITI approach in Amsterdam, the Hague, Rotterdam and Utrecht has led to the closer integration of social with economic aspects of policies and increased cooperation between municipalities, schools and companies., while in Bretagne, it has helped to improve cooperation between the Regional Council and local people and organisations on the ground.

Evaluations carried out in 2014-2020 of the effects of integrated urban development strategies financed by the ERDF in the 2007-2013 period also show positive results. In Lubelskie, again in Poland, the regeneration projects funded increased the attractiveness of the areas redeveloped as places to live, work and locate investment in. In Romania, the investment financed helped to improve public spaces, stimulate economic and social activity, reduce traffic congestion and increase traffic safety, raise visitor numbers and revitalise cultural life as well as to develop new social services.

1.5.2.2. Support for cross-border cooperation at local level

In a number of cases, the measures funded led to increased cooperation between local bodies in different countries and wider involvement of locals in decision-making, so laying the basis for more inclusive and effective policies.

Under the Bayern-Czech Republic Interreg programme, for example, the projects supported led to increased institutional cooperation and networking across the border at the local level. The same is true of measures financed under the Czech Republic-Poland Interreg programme which also increased long-term cooperation between local bodies on the two sides of the border.

2. Interreg

The sections above include the Interreg programmes financed under the European Trans-national Cooperation objective, under which funding was also allocated to the 11 Thematic Objectives which cohesion policy was aimed at pursuing. In total, some EUR 10.1 billion went to Interreg over the 2014-2020 period, around two-thirds going to regional cross-border programmes, the rest going to transnational and interregional programmes (

Map 9.

5

).

Map 9.5 ERDF Cross-border cooperation programmes, 2014-2020

The indicators for the expenditure funded under the Interreg programmes show that in many cases the targets set to be achieved by 2023 had already been reached by the end of 2020, which suggests perhaps that these could have been set at a more ambitious level (

Table

9.

6