EUROPEAN COMMISSION

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Brussels, 4.10.2017

SWD(2017) 325 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

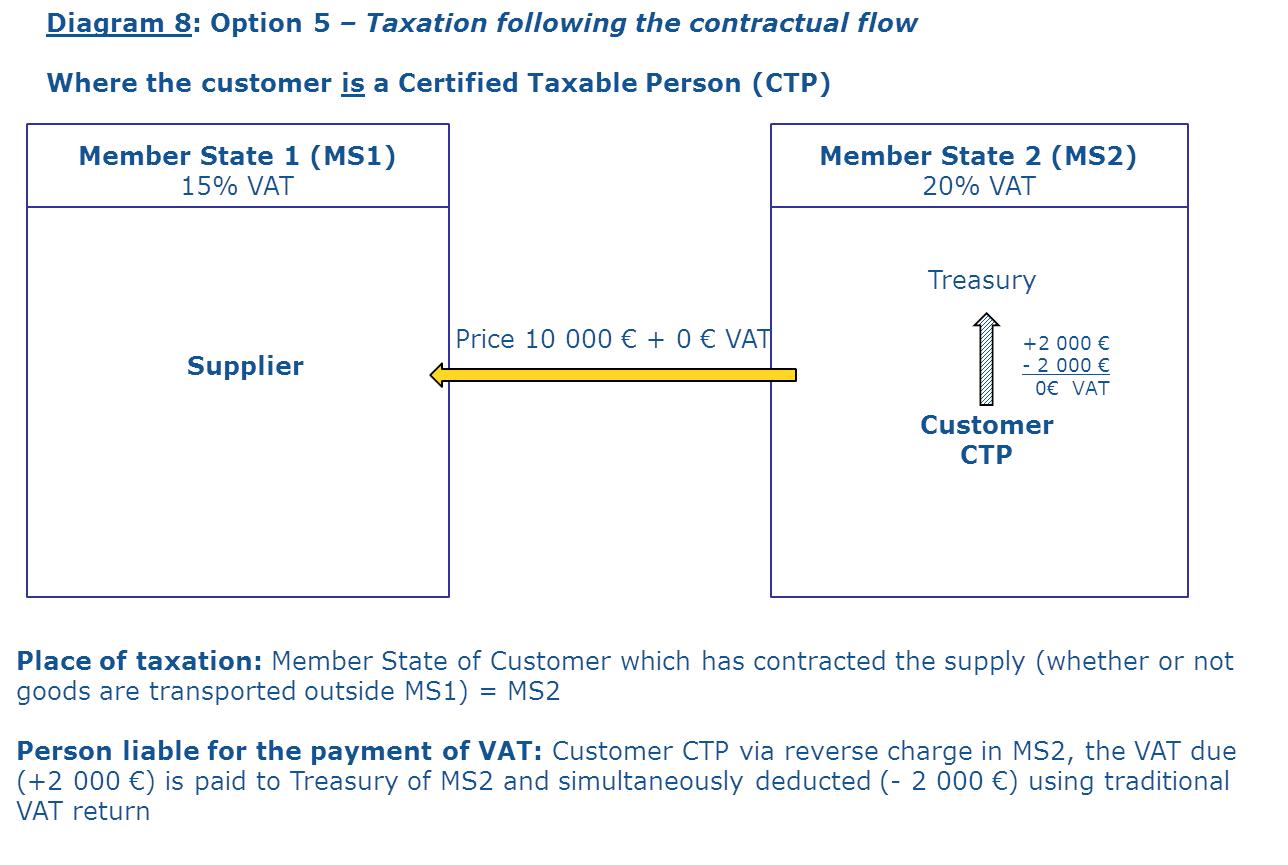

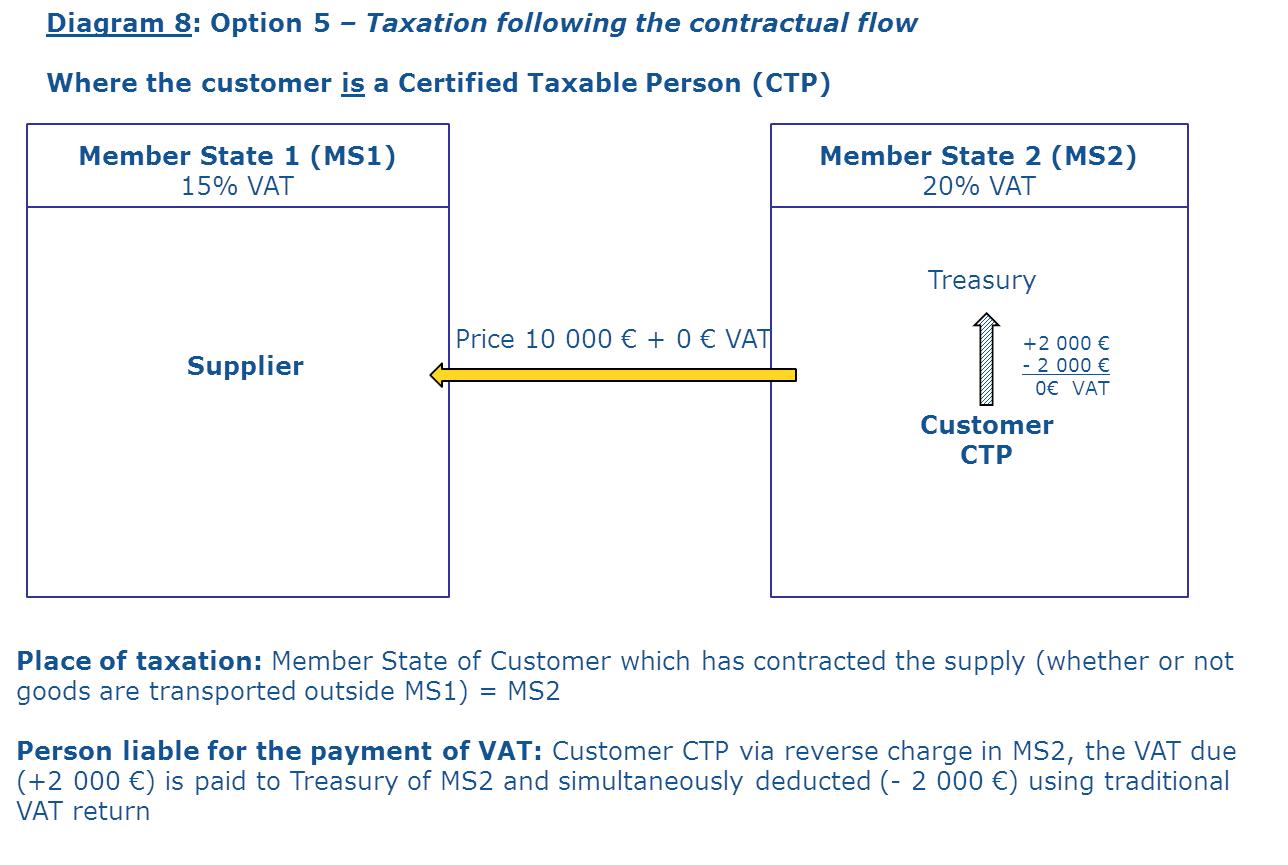

IMPACT ASSESSMENT

Accompanying the document

Proposal for a Council Directive

amending Directive 2006/112/EC as regards harmonising and simplifying certain rules in the value added tax system and introducing the definitive system for the taxation of trade between Member States

{COM(2017) 567final}

{COM(2017) 568 final}

{COM(2017) 569 final}

{SWD(2017) 326 final}

Table 5:

Table 5:

Main features of the options

Table 6:

Table 6:

Summary

impacts on Member States in net monetary terms (EUR millio

ns)

Table 7:

Table 7:

Summary

impacts on compliance costs of businesses

Table 8:

Table 8:

Summary analysis of impacts

Table 9:

Table 9:

Monitoring

and evaluation framework

Table 10: Stakeholders consulted

Table 10: Stakeholders consulted

Table 11: Consultation activities

Table 11: Consultation activities

Table 12: Primary data collection instruments

Table 12:

Primary data collection instruments

Table 13: Criteria for defining business types

Table 13:

Criteria for defining business types

Table 14:

Table 14:

Forecasts of the macroeconomic variables under the baseline (3-year cumulative growth)

Table 15:

Table 15:

Difference in % of the 3-year cumulative growth of the macroeconomic variables under each of the five policy options differ from the baseline

Table 16: Inventory of possible options

Table 16: Inventory of possible options

Abbreviations

|

B2B

|

Business to Business

|

|

B2C

|

Business to Consumer (not VAT registered)

|

|

CJEU

|

Court of Justice of the European Union

|

|

CTP

|

Certified Taxable Person

|

|

EU

|

European Union

|

|

EUR

|

Euro

|

|

FTE

|

Full Time Equivalent

|

|

GDP

|

Gross Domestic Product

|

|

GFV

|

Group on the Future of VAT

|

|

MOSS

|

Mini One Stop Shop

|

|

MTIC fraud

|

Missing Trader Intra-Community (MTIC) fraud

|

|

OSS

|

One Stop Shop

|

|

SME

|

Small and Medium-sized Enterprises

|

|

VAT

|

Value Added Tax

|

|

VEG

|

VAT Expert Group

|

|

VIES

|

VAT Information Exchange system.

|

Glossary of terms in their meaning within this document and for its specific purpose

|

Administrative costs

|

Costs for tax administrations.

Administrative costs for a tax administration will include costs relating to the following activities: processing VAT registrations, undertaking VAT audits, reviewing VAT returns, reviewing recapitulative statements, helpline and written query handling and the implementation of new legislation.

|

|

Business types

Large business

Micro business

SME Type 1

SME Type 2

|

A large business is defined as a business with a turnover exceeding EUR 50 million, having more than 250 employees, and possessing VAT registration in six or more Member States. For further details on the definition of a large business, please see Annex 4.

A micro-business is a business which has fewer than ten employees and a turnover or balance sheet total of less than EUR 2 million.

An SME (Small and Medium-sized Enterprises) Type 1 business is defined as a business with a turnover of less than EUR 50 million, having less than 250 employees and a single VAT registration in its Member State of establishment. Further details on the definition of an SME Type 1 business are available in Annex 4.

An SME (Small and Medium-sized Enterprises) Type 2 business is defined as a business with a turnover of less than EUR 50 million, having less than 250 employees and VAT registrations in more than one (but less than six) Member States. Further details on the definition of an SME Type 2 business are available in Annex 4.

|

|

Compliance costs

|

Costs for businesses.

Compliance costs for businesses will include costs relating to the following activities: registration for VAT, completion of periodic VAT returns, dealing with a VAT audit, obtaining customer's VAT registration details, completing recapitulative statements and obtaining proof of the intra-EU movement of goods.

|

|

Cross-border trade

|

Refers solely to intra-EU cross-border B2B trade.

The terms "trading across the EU", "trading cross-border", "trading in another Member State", "doing business in other Member States", "doing business across the EU", "intra-EU transactions, "intra-EU trade" refer to any situation where a business: (i) makes supplies of goods taxable in a Member State other than that in which he is established; (ii) acquires goods from a business established in another Member State; or (iii) supplies goods to a customer established in another Member State.

|

|

EU VAT Forum

|

The EU VAT Forum was set up by a decision of the European Commission 2012/C198/05 of 3 July 2012 and offers a discussion platform where business and VAT authorities meet to discuss how the implementation of the VAT legislation can be improved in practice.

|

|

EUROFISC

|

EUROFISC is a network for the swift exchange of targeted information between Member States. See information under following link

EUROFISC

.

|

|

Expert stakeholders

|

Members of the VAT Expert Group

|

|

Full Time Equivalent

(FTE)

|

A Full Time Equivalent is a unit that indicates the workload of an employed person of a business or a Member State Tax Authority. For the purposes of this document, it is defined as forty hours per week.

|

|

Group on the Future of VAT (GFV)

|

The Group on the Future of VAT is an informal Commission expert group set up in 2011 in response to the need for a forum where more in-depth discussions on the topics raised in the 2010 Green Paper can be held. The Group is composed of delegates (VAT experts) from the 28 EU Member States' tax administrations and serves as a forum for in-depth discussion and exchange of opinions on the Commission's pre-legislative initiatives and the preparation of future VAT legislation.

|

|

Treasury

|

A government department related to finance and taxation of a particular jurisdiction (of a Member State or a third country)

|

|

VAT Committee

|

Under Article 398 of the VAT Directive (Directive 2006/112/EC), the VAT Committee deals with the obligatory consultations required by certain Articles of that Directive. In addition, it examines questions on the application of the Community VAT provisions raised by the Chairman on his own initiative or at the request of a Member State. The VAT Committee is also a forum for the exchange of views in order to reach guidelines on a uniform application of common practices with regard to VAT provisions.

|

|

VAT Expert Group (VEG)

|

The VAT Expert Group was set up in 2012 by Commission Decision 2012/C 188/02 of 26 June 2012 in response to the request by stakeholders for greater involvement in the process of preparing EU VAT legislation expressed during the public consultation launched by the 2010 Green Paper on the future of VAT. The Group is composed of 40 members: individuals with the requisite expertise in the area of VAT and organisations representing in particular businesses, tax practitioners and academics, and serves as a bilateral forum to allow for an open, structured and transparent dialogue between the Commission and stakeholders on any matter relating to the preparation and implementation of EU legislation and other policy initiatives taken at EU level in the field of VAT.

|

|

VIES

|

Electronic means of validating VAT-identification numbers of economic operators registered in the European Union for cross-border transactions on goods or services.

See more info on:

http://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/vies/

|

1.Introduction and context

1.1.Introduction

Value Added Tax (VAT) is a general tax on consumption applied to supplies of goods and services along the whole production and distribution process. It is a major and growing source of tax revenue in the European Union (EU). VAT raised slightly more than EUR 1 trillion in 2015, which corresponds to 7% of EU GDP or 17.6% of total national tax revenues

. One of the EU's own resources is also based on VAT (12.4% of the EU budget in 2015)

. As a broad-based consumption tax, it is considered to be one of the most growth-friendly forms of taxation.

One of the key strengths of VAT is that, by allowing businesses to exactly offset the tax incurred in previous stages of the production chain, it is much better suited than other types of indirect taxes to operate an internal market free of tax distortions. This was the main reason for its early adoption by the EU. It is governed by the VAT Directive

which aims at ensuring that the principles underlying the functioning of this tax apply consistently in all Member States.

In recent years, however, the VAT system has been unable to keep pace with the challenges of the global economy and the opportunities offered by new technologies. Therefore, the Commission adopted on 7 April 2016 an Action Plan on VAT

(hereinafter "Action Plan") setting out ways to modernise the VAT system so as to make it simpler, more fraud-proof and business-friendly. In this context, the Commission announced its intention to adopt in 2017 four VAT-related proposals:

1)a definitive VAT system for intra-EU cross-border trade based on the principle of taxation in the Member State of destination in order to create a robust single European VAT area (first legislative step);

2)a modernised VAT rates policy so as to allow Member States greater autonomy on setting the VAT rates;

3)a comprehensive simplification VAT package for SMEs;

4)a proposal to enhance VAT administrative cooperation and

EUROFISC

.

This impact assessment relates to the first mentioned proposal on a definitive VAT system for intra-EU trade (hereafter the "initiative").

This initiative is part of the Commission's Regulatory Fitness and Performance Programme (REFIT). All the options (except baseline) of this initiative will likely have significant impacts on simplification and will reduce administrative burden and compliance costs. These benefits for businesses (including SMEs) would have a positive impact on economic growth and competitiveness.

1.2.Scope of the initiative

1.2.1.Taxation of trade between Member States

The VAT Directive defines the way in which VAT is to be collected both on domestic transactions (involving one single Member State) and on cross-border transactions (involving more than one Member State). As explained in Section 1.4 below, the current system for the taxation of trade between Member States is based since 1993 on "transitional arrangements".

These transitional arrangements suffer from numerous shortcomings which result in the VAT system being neither fully efficient nor compatible with the requirements of a true single market. This has been confirmed by the large majority of stakeholders during the broad based public consultation on the Green Paper on the future of VAT and by more recent feedback received from business stakeholders via the

REFIT Platform

(see further details in Annex 2 and Annex 5, Section 3). The European Parliament, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Tax Policy Group also confirmed the need to reform the VAT system.

Further consultation with the Member States and other stakeholders in the framework of specialised and structured forums for discussion, respectively the Group on the Future of VAT (GFV) and the VAT Expert Group (VEG) (see more detailed information in Annex 1, Section 4), led to the conclusion that the transitional arrangements are too complex and costly for the growing number of businesses operating cross-border. It also showed that the transitional arrangements leave the door open to fraud.

While the reform of the taxation of trade between Member States regarding transactions between businesses and final consumers (hereafter "B2C transactions") has started to be effective as from 1 January 2015 and its further development is currently the subject of negotiations in Council, the initiative that is here being assessed is focussed exclusively on transactions between businesses (hereafter "B2B transactions").

The purpose of this initiative is to put in place a definitive VAT system so as to pave the way for the creation of a genuine single EU VAT area for the internal market. This means a VAT system simpler for businesses trading across the EU while at the same time more robust to fraud, to the benefit of the Member States and also of compliant businesses. The efficiency of the VAT system needs to be further improved, in particular by exploiting the opportunities of digital technology and by enhancing greater trust between business and tax administrations and between EU Member States' tax administrations.

1.2.2.Rationale for a two-step approach

As announced in the Action Plan, the introduction of the definitive VAT system will be made through a gradual two-step approach. As a first legislative step, the VAT treatment of intra-EU B2B supplies of goods would be settled. As a second legislative step, this treatment would be extended to all cross-border supplies, therefore also covering supplies of services. Only the first legislative step is the subject of the initiative that is here being assessed.

There are several reasons for this. In the first place, the introduction of the definitive VAT system means, above all, doing away with the transitional arrangements. These arrangements basically refer to goods. This owes to the fact that prior to 1 January 1993 only cross-border intra-EU supplies of goods (and not of services) gave rise to imports and exports. The transitional arrangements were a practical means of accommodating this situation. Therefore any attempt to replace those transitional arrangements will have to focus essentially on goods.

Second, the application of the principle of taxation at destination becomes particularly necessary when it comes to goods. As regards services, on 4 December 2007 the Council reached a political agreement on two draft Directives and a draft Regulation (the so-called "VAT package") aimed at changing the rules on VAT so as to ensure that VAT on services accrues to the Member State where consumption occurs, i.e. according to the principle of taxation at destination. Its adoption by the Council on 12 February 2008 was an important step towards simplification for businesses.

The rules regarding B2B supplies of goods remained however unchanged. Despite the fact that, in practice, their taxation effectively occurs at destination (i.e. where the goods arrive) the logic of the origin principle with its two transactions still remains.

Third, intra-EU B2B trade in goods still requires a number of obligations which do not exist for services (e.g. proof of intra-EU transport of the goods, need to register in another Member State for particular transactions like consignment stocks, need to ascribe the intra-EU transport to a specific supply in the case of chain transactions - see further explanation under Section 2.4). There is therefore now a particular need to simplify the rules for goods.

Fourth, as will be seen further the preferred option for the definitive VAT system builds on certain new technical solutions (a one-stop-shop mechanism (OSS) which includes the right to deduct input VAT - see further explanation in box 5 below). It seems reasonable to provide for a staged application of these solutions so that once they have proven to be efficient on transactions in goods, they will be also extended to intra-EU supplies of services. Such an approach has the advantage of limiting to one category the number of transactions that will be affected by the new rules and of reducing the amounts of VAT channelled through the OSS.

In this regard, the staged approach is consistent with the one taken in VAT matters regarding the OSS. Initially a Mini One Stop Shop (MOSS - see further explanation in box 5 below) was established for B2C telecommunications, broadcasting and electronic services provided by third country suppliers. That MOSS was later extended to intra-EU cross border supplies of those same services. Next, it is foreseen in the e-commerce proposal for the OSS to be extended to intra-EU B2C supplies of goods and services and to supplies of goods imported from third countries or third territories. The initiative means a further step in this direction targeting intra-EU B2B supplies of goods. Finally, the process will be completed at a later stage with the extension of the OSS to intra-EU B2B supplies of services.

In any event, the stage embodied by the initiative is an essential one since, as can be seen from the figures below, goods remain the main elements that are being traded across the EU as services represent only one third of the share of goods' transactions. In focussing on goods, as a first step, the objective of reducing VAT losses resulting from cross-border fraud would also be better targeted.

|

Cross-border transactions in the EU single market, 2015

|

|

Intra-EU 28 trade (2015)

|

In billion EUR

|

|

Goods

|

|

|

Export (dispatches)

|

3.068

|

|

Imports (arrivals)

|

2.993

|

|

Services

|

|

|

Export (credit)

|

1.016

|

|

Imports (debit)

|

923

|

Source: Eurostat

In addition and with a view to accommodate the specific request from Member States in Council, the initiative will also propose certain improvements to the current VAT legislation. These improvements (hereafter the "quick fixes") are meant to address specific concerns with the current rules and are without prejudice to the more fundamental reform aimed at.

1.3.Interaction of the initiative with the upcoming VAT proposals on rates, SMEs and administrative cooperation

The initiative on the definitive VAT system is an important step towards a modernised VAT system. It builds upon previous initiatives and creates opportunities for the following particular areas that will each give rise to own legislative proposals.

1.3.1.VAT rates

Although the destination principle has been progressively implemented since 2008, the initiative operates a fundamental (and therefore "definitive") change in the basic logic of the VAT system. The choice of a destination-based system raises the question of whether, and to what extent, the existing legal limits on rates are still necessary. Indeed, while harmonisation of the VAT rates is needed under an origin-based system to avoid distortions of competition, this is not the case under a destination-based system. That is what the proposal on VAT rates will address. However, even without a change in the current VAT rates structure, the initiative will have consequences on the collection of VAT. Therefore, the initiative will, independently from the proposal on VAT rates, provide for a central web-portal that will include information on the VAT rates applicable in all Member States.

1.3.2. SMEs

The fundamental nature of the changes made by the initiative means that all businesses will be impacted. While the simplification measures provided for under the initiative would also benefit SMEs, they are not specifically targeted to help SMEs. The difficulties of SMEs, in particular when trading cross-border, will be addressed through a specific proposal.

1.3.3.Administrative cooperation

As will be explained later, one of the problems the initiative intends to tackle is VAT cross border fraud. However, since the full operation of the initiative will take some time, it is necessary to already improve the mechanisms in place in order to fight this type of fraud. Improved administrative cooperation between the Member States and a better functioning of the VIES system (which will allow enhancing the quality and reliability of the information exchanged between the Member States) are elements which, at the same time, will in the short term improve the fight against fraud and in the medium term will support each step of the implementation of the definitive VAT system. Further, it will allow building trust between the Member States, which will facilitate the proper operation of the initiative.

As can be seen, there is a direct link between the four proposals in that they together result in a coherent reform as put forward in the Action Plan. This is why they are planned to be adopted by the Commission this year as a package. However, although they are logically connected, the four proposals are nevertheless technically not linked. This means that each proposal can work on its own independently of the others although it would be preferable, for the sake of soundness of the reform, to have them all adopted by the Council.

1.4.Functioning of the common system of value added tax

1.4.1.Basic principle: the fractioned collection of VAT

VAT is assessed on the value added to goods and services that are bought and sold for use or consumption in the EU. It is, as a rule, collected fractionally by businesses and, as a consumption tax, is borne ultimately by the final consumer.

This system of partial payments allows the tax to be collected at each stage in the production and distribution chain and ensures the self-policing character of this tax (see box 1 below).

Box 1: VAT system based on fractioned payments

On each supply made by a business, VAT is charged to its customers at the rate applicable. That business then deducts from the VAT collected from its customers the amount of tax it has itself paid to other businesses on purchases used for its own business activities. Where the customer is also a business, this system is replicated until it reaches the final consumer. At this last stage of the supply chain, the VAT is no more deductible and the tax is definitively vested to the Treasury.

Example: VAT rate is 20%

A, B, C and D are businesses, i.e. taxable persons with a right to deduct input VAT

A sells goods to B for 100 and charges 20 VAT which is paid over to the Treasury. B supplies the goods to C for a total amount of 240 (including 40 VAT). B then deducts its input VAT of 20 from the 40 received from C and pays the difference of 20 to the Treasury. C sells these goods on to D for 360 (including 60 VAT). Then C deducts its input VAT of 40 from the 60 received from D and pays the difference of 20 to the Treasury. Finally, D sells the goods for 480 (including 80 VAT) to a final consumer. D deducts its input VAT of 60 from the 80 received and pays the difference of 20 to the Treasury.

At each stage, VAT is paid to the Treasury on the added-value. For a given business that is the difference between the price paid to it by its customer and the amount paid by the business to its supplier.

The self-policing character of the VAT system is linked to the need for each customer to pay VAT and to hold an invoice in order to be allowed to deduct the VAT paid to its supplier who, in turn, is discouraged from evading taxes (as it has issued an invoice). In case of fraud by the retailer (D) or anyone else in the chain (A, B or C), EUR 20 is lost, but not the total amount of EUR 80.

1.4.2.VAT treatment of intra-EU supplies of goods before 1993

When the common system of VAT was established in 1967, intra-EU cross-border supplies of goods between businesses were treated differently as compared with domestic transactions (see box 8 in Section 1 of Annex 5). They gave rise to exports exempted in the Member State of origin (Member State of departure of the goods) and were taxed upon import in the Member State of destination (Member State of arrival of the goods), according to the principle of taxation at the Member State of destination (for further explanation on origin and destination concepts see Section 2 of Annex 5).

However, the commitment was made already at that time to establish a definitive VAT system, based on the principle of taxation in the Member State of origin, which would therefore operate within the EU in the same way as it would within a single Member State.

1.4.3.VAT treatment of intra-EU supplies of goods since 1993

The abolition of fiscal frontiers between Member States by the end of 1992, of which the objective and timing were set out in the Single European Act, made it necessary to reconsider the way in which trade in goods was taxed in the EU. That was due to the fact that exports and imports were no longer possible for VAT purposes as far as intra-EU cross-border trade in goods was concerned. At that time, the goal remained that goods would be taxed in the Member State of origin, perfectly reflecting the idea of a genuine internal market.

Under that origin system, a business established in a Member State ("MS1") would invoice its cross-border supplies of goods to other Member States ("MS2") in exactly the same way as the domestic supplies in MS1; i.e. by charging the VAT of MS1. The taxable customer would be allowed to deduct that VAT, collected by MS1, in his VAT return submitted in MS2. Because of that so-called cross-border deduction, a compensation or clearing system had to be put in place for reallocating the revenues between the Member States. This system would, in practice, create a collective responsibility whereas under the then existing system each Member State was individually responsible for the administration, control and collection of its own VAT. A high degree of trust between Member States was therefore a pre-condition for the new system.

Another essential element in order for the origin system to work properly was the convergence or approximation of VAT rates (and some other technical aspects such as exemptions). Otherwise major distortions of competition would occur since consumers would tend to acquire goods, for fiscal reasons, from Member States applying low VAT rates. This would run counter to the basic principle of VAT neutrality.

However, on these two essential points Member States were unable to agree before the foreseen date and since the political and technical conditions were not ripe, transitional arrangements were instead adopted and entered into force on 1 January 1993 (see box 2 below). These arrangements split the cross-border intra-EU movement of goods into two different transactions: an intra-EU supply of goods exempt in the Member State of origin (the supplier does not charge VAT on his supply) and an intra-EU acquisition of goods taxed in the Member State of destination (the customer self-accounts for the VAT due via a mechanism equivalent to a "reverse charge"). With some few exceptions, these arrangements are essentially equivalent to the previous export/import customs system.

These rules were intended to be temporary (initially four years) but are still in force. Further, the currently applicable VAT legislation provides that these temporary arrangements (hereinafter referred to as the "current transitional VAT system") have to be replaced by definitive arrangements based on the principle of taxation in the Member State of origin.

Box 2: Transitional VAT system since 1993

As from 1 January 1993, the fiscal frontiers and all corresponding export/import schemes between Member States have been abolished and replaced by a system of exempt supplies in the Member State of origin and taxed 'intra-EU acquisitions' (a new taxable event) in the Member State of destination thus mirroring, but without customs procedures, the previous scheme. As customs documentation no longer guaranteed the follow-up of the physical flow of the goods, a new reporting system was put in place: the VAT Information Exchange System (VIES). Via a system of listings, submitted by the supplier in the Member State of origin (Member State 1) and subsequently sent to the Member State of destination (Member State 2), the latter is informed about the arrival of goods on its territory destined for D, a business registered for VAT purposes in Member State 2 and obliged to declare this intra-EU acquisition in its VAT return. Preceding supplies (A to B and B to C) and subsequent supplies (D-E) are, as in the previous system, domestic supplies taxed with VAT. Both the VAT charged on the supply made by A to B, by B to C and by D to E and the VAT due by D on the intra-EU acquisition are as a rule deductible (as regards C through a refund since there is no output VAT on the supply made by C against which the deductible VAT of 30 can be offset). With regard to the intra-EU acquisition, D will account for VAT and deduct it in the same VAT return; the result is therefore nil.

2.What is the problem and why is it a problem?

2.1.Problem tree

The following figure summarises the problems, the problem drivers and the consequences as explained in the next sections.

2.2.Evaluation of the EU VAT system and other sources attesting to the problems

A comprehensive retrospective evaluation of the EU VAT system

was conducted in 2011 and its findings have been used as a starting point for the examination of the current transitional VAT system. This evaluation was a comprehensive exercise that covered all important aspects for the design of an improved VAT system.

The evaluation had been carried out before the Better Regulation Guidelines were put in place. This means in practice that the structure of the 2011 evaluation was not organized around the five evaluation criteria (Relevance, Effectiveness, Efficiency, Coherence and EU added value) that became mandatory later on. Nevertheless, the evaluation provided solid analysis of the problems underlying the current transitional VAT system, the results of which have been confirmed by further consultation of stakeholders (open public consultations, targeted stakeholder consultation through the GFV and the VEG - see Annex 2) as well as recent studies (see Annex 6). It looked in particular into the design and implementation of the most important elements of the current VAT system, including the functioning of the transitional VAT arrangements, and assessed their effectiveness and efficiency in terms of results (meeting objectives they were serving) and impacts (direct, indirect, expected and unexpected) they had created. It also examined their relevance and coherence with the smooth functioning of the single market and the requirement to avoid distortion of competition specified in Article 113 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

The findings of the evaluation are therefore still valid and relevant for use in this impact assessment. A summary of the key elements of this evaluation organised around the five evaluation criteria mentioned above is provided in Annex 6.

According to the evaluation and further research, there are two fundamental problems regarding the current transitional VAT system:

1)The existing levels of VAT fraud within the EU caused by fraudulent activities such as Missing Trader Intra-Community fraud (hereinafter MTIC fraud).

This problem is referred to as "Intra-EU cross-border VAT fraud".

2)The complexity of the current transitional VAT system leading to additional costs for those businesses which engage in intra-EU cross-border trade.

This problem is referred to as "Complexity of the current transitional VAT system".

The problems, their drivers and consequences are further developed below. For more details on the reform process and the sources attesting to the existence of the problems see respectively Sections 3 and 4 of Annex 5.

2.3.Problem 1: intra-EU cross-border VAT fraud

2.3.1.The problem and its EU dimension

The evaluation of the EU VAT system underlined the revenue losses that the Member States face as a result of the high levels of VAT fraud. According to this evaluation, although most of the VAT fraud is considered to be domestic, it has increased at EU level because of the growth in the phenomenon of MTIC fraud following the abolition of the EU’s internal fiscal frontiers. This particular fraud is associated to the fact that the current transitional VAT system allows trading VAT free across Member State borders (see further explanation under Section 2.3.3).

The size of the VAT fraud is difficult to measure but the VAT gap offers a useful and also unique EU-wide indicator. According to the latest Commission report on the VAT gap which relies on data from 2014, the overall EU VAT gap in nominal terms is estimated at almost EUR 160 billion in revenue losses each year or 14.06% of the total expected VAT revenue. The VAT gap varies considerably between Member States. The smallest gaps are observed in Sweden (1.24%), Luxembourg (3.80%), and Finland (6.92%). The largest gaps are registered in Romania (37.89%), Lithuania (36.84%) and Malta (35.32%). Overall, half of the EU-27 Member States record a gap above 10.4% (see Figure 1 below).

That VAT fraud problem has been made worse, according to views expressed by certain Member States in the GFV and in the VAT Committee by the case-law of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). According to that case-law the exemption of an intra-EU supply of goods cannot be refused if the material conditions for the exemption are met, even in absence of the VAT identification number of the customer acquiring the goods.

The problem created by this case-law stems from the fact that the EU legislator established the VAT identification number as the basic tool to control the proper functioning of the current transitional VAT system for intra-EU trade. In fact, the recapitulative statements and the VIES system, which are also essential elements of control in this regard, are all based on the VAT identification number and cannot work without it.

Figure 1: VAT Gap as a percent of the VAT Total Tax Liability (VTTL) in EU-27 Member States, 2014 and 2013 (source CASE, 2016)

Very few Member States publish estimates of the size of MTIC fraud, supposedly because the nature of this type of fraud makes it difficult to measure. However, a recent study commissioned by the Commission confirmed the findings of the evaluation as MTIC fraud alone is found to be responsible for VAT revenue losses of approximately EUR 45 billion to EUR 53 billion annually.

The MTIC fraud portion of the VAT gap ranges from 12% in Bulgaria to 39% in France (see Figure 2 below on the share of MTIC fraud in the VAT gap). On average (weighted average) it is estimated that 24% of the overall VAT gap is due to MTIC fraud. The rest of the VAT gap is attributed to losses of revenue due to domestic fraud and evasion, tax avoidance, bankruptcies, financial insolvencies, as well as miscalculations.

Figure 2: Share of MTIC fraud in the VAT gap (source "Own calculations" based on EY, 2015 study)

2.3.2.Evolution of the problem

Monitoring at EU level of VAT collection by individual Member States is relatively recent as the first study on the VAT gap dates back to 2009. The methodology is continually improved and annual updates of the study include the latest revised figures. Although the Commission is seeking to develop methods to extract data on fraud from the VAT gap, such information is still not available. The next VAT gap study is expected for 2018. The above estimations on MTIC fraud were provided by one specific study and, contrary to the VAT gap study, no further data on its trend evolution is available.

The trend of the VAT gap over the period 2010-2014 is shown in Table 1 below. For the EU-26 as a whole, the VAT gap has increased from 13.53% in 2010 to 14.06% in 2014, which in absolute monetary terms amounts to an increase of about EUR 25 billion..

Table 1: VAT Gap estimates, 2010 - 2014

|

EU-26

|

2010

|

2011

|

2012

|

2013

|

2014

|

|

VAT Gap (EUR million)

|

134 806

|

152 237

|

162 537

|

161 442

|

159 460

|

|

VAT Gap (%)

|

13.53

|

14.41

|

14.97

|

14.75

|

14.06

|

|

VAT Gap (change pp)

|

|

0.88

|

0.56

|

-0.22

|

-0.69

|

Source: CASE, 2016 and own calculations based on CASE, 2016.

Information on the VAT gap and on MTIC fraud for the period 1993-2009 (which followed the entry into force in 1993 of the current transitional VAT system put in place at the time the fiscal frontiers between the Member States were abolished) is not available, although it is likely that MTIC fraud (which finds its roots in the way the transitional VAT system is designed) has taken a few years to appear and to develop.

2.3.3.Problem driver: the endemic weakness of the current transitional VAT system resulting from the break in the fractioned collection of VAT

In domestic trade, as a rule, the collection of VAT is based on fractioned payments. VAT is collected at each stage in the production and distribution chain and this ensures the self-policing character of this tax (see box 1 above). Customers pay the VAT due on their purchases to their suppliers who will remit it to the Treasury after deduction of the VAT charged to them by their own suppliers. The collection of VAT on behalf of the Treasury is therefore ensured by suppliers through direct payments received from their customers.

In intra-EU trade in goods, this fractioned payment system is broken. The rules of the current transitional VAT system split every cross-border sale of goods between businesses into an exempted supply in the Member State of origin (i.e. no VAT is charged by the supplier to his customer) and a taxable acquisition in the Member State of destination (i.e. the customer is liable to pay the VAT due to the Treasury but no VAT is actually paid as he has an immediate right of deduction - see further explanation in box 2 above). It is like a customs export-import scheme, but lacks equivalent border controls and is therefore at the root of MTIC fraud, the typical intra-EU cross-border fraud.

MTIC fraud exploits the endemic weakness of the current VAT system (which was meant to be transitional – see explanation in box 2 above), that allows for goods to be bought cross-border VAT-free because of the break in the fractioned payment chain. The basic MTIC fraud scheme (see further details in box 3 below) involves a cross-border purchase of goods by a fraudster, followed by a domestic supply by that fraudster. The cross-border purchase of goods allows the fraudster to make a VAT neutral purchase (no payment of VAT, either to the supplier or to the Treasury). The subsequent domestic supply allows the fraudster to charge and collect the VAT from his customer. Instead of paying the whole of this VAT over to the Treasury, he takes the VAT with him and disappears.

Another type of fraud which must be mentioned here is "diversion fraud". Although not considered as typical intra-EU cross-border fraud because it mainly happens regarding exportation of goods to third countries, diversion fraud also exploits the rules of the current transitional VAT system.

Intra-EU diversion fraud occurs when a fraudster reports an intra-EU supply of goods but then "diverts" the goods to the domestic market so that they remain in the same Member State and are sold without leaving the territory. The VAT fraud is crystallised in the amount of VAT charged by the fraudster to the customer, which is not accounted for to the Treasury (since the fraudster has reported to the authorities a fake intra-EU supply exempt from the VAT) (see Section 5, box 9 in Annex 5).

MTIC fraud can be committed in many different ways and the schemes become more elaborated every time. During the nineties of the last century, the fraudsters started their fraudulent activities in the simplest way. The typical MTIC fraud was committed by three or four companies involving two Member States. The most serious form of the fraud – known as carousel fraud – involves a series of contrived transactions within and beyond the EU, with the aim of creating large unpaid VAT liabilities and fraudulent VAT repayment claims. Similar to how a carousel goes round and round, the goods are passed around between companies and jurisdictions, generating each time losses for the Treasuries involved.

The following scheme illustrates the typical MTIC fraud leading to carrousel fraud.

Box 3 - Typical MTIC fraud leading to carrousel fraud

The basic mechanism usually involves the following transactions (see scheme below; VAT rate is 20%):

§Company A (so-called “conduite" company), registered in Member State 1, makes an exempted intra-EU supply to company B (so-called “missing trader”) registered and located in Member State 2. VAT is accounted for on the acquisition by company B but deducted in the same VAT return so that no actual payment of VAT has to be made to the Treasury of Member State 2.

§Company B subsequently makes a domestic supply to company C (so-called “buffer”). Company B charges VAT on the invoice sent to company C, collects it but does not pay the VAT to the Treasury of Member State 2. Company B then rapidly disappears.

§Company C (which on the basis of the invoice issued will deduct the VAT charged by B) is usually used as a means to distort VAT investigations (in a three-company carrousel there is no buffer company).

§Company C resells on the domestic market the goods to company D (broker) which will deduct the VAT charged on its purchases. D will eventually make an intra-EU supply to company A in Member State 1 in order to ask for refund of the VAT charged on its purchases.

Following the scheme, the missing trader will not declare and/or pay the charged VAT to the Treasury.

At the end of the chain, the broker company will claim a refund because he makes an intra-EU supply to another Member State. At this moment money is paid out by the Treasury which has not been received from the missing trader earlier in the chain.

The loss of VAT receipts can be unlimited as the same goods can be supplied several times over by including again exempt intra-EU supplies. The profit of the fraudulent chain can be easily shared between all the participants.

In practice the scheme as illustrated can be combined with all possible types of MTIC VAT fraud and developed over the borders of several Member States and eventually third countries.

The recent legislative proposal submitted by the Commission to Council, which echoes the request from certain Member States to be allowed to apply a generalised reverse charge mechanism as an urgent measure to combat carrousel fraud, shows how the shortcomings of the current transitional VAT system can severely affect certain Member States. It also reveals the limits of traditional measures to combat such fraud. This is corroborated by recent reforms implemented in several Member States (e.g. new collection methods introduced in respect of certain transactions, compulsory electronic invoicing transiting via the tax administration) with a view to improving VAT collection.

2.3.4.Consequences: who is affected and how?

·Member States: MTIC fraud represents a cost for Member States through losses in tax revenue of approximately EUR 45 billion to EUR 53 billion annually. It is also likely to generate additional administrative costs through the need for additional audits, administrative and/or judicial proceedings.

·Businesses: MTIC fraud may also generate unexpected costs for businesses that inadvertently and unknowingly become involved in a fraudulent supply chain and may need to bear the unpaid VAT and any relevant penalties. Further it creates unfair competition between compliant and non-compliant businesses since fraud enables the latter to sell goods in the market at a lower price than the former. Finally, it generates extra compliance costs, since Member States in an attempt to fight fraud impose new obligations which fall upon honest businesses. This problem was raised on various occasions by businesses including in submission XVIII.1.a provided via the REFIT platform.

·Citizens/Society: By depriving Member States of tax revenues, MTIC fraudsters are effectively robbing EU citizens of the means for governments to fund the provision of infrastructure such as schools and hospitals as well as other public services. Losses in tax revenues might also have to be compensated by other forms of additional taxation. MTIC fraud is associated to organised crime. Fraudsters often use their profits to fund other forms of criminality, such as cigarette smuggling or drug trafficking. MTIC fraud also appears to be used to launder money and return a healthy profit. During the consultation process (see Annex 2), stakeholders concurred that MTIC fraud and other fraudulent schemes have negative effects on the tax collected and the protection of the rights of the honest businesses. Stakeholders insisted that fraud must be tackled by specific long term remedies addressed only to fraudulent businesses and the vast majority of the respondents commented that antifraud measures should be harmonised to be effective. Over 74% agreed that the current system is not sufficiently resistant to VAT fraud.

2.4.Problem 2: The complexity of the current transitional VAT system

2.4.1.The problem and its EU dimension

The establishment in 1993 of the single market was meant to reduce compliance costs associated with intra-EU trade, chiefly through the abolition of customs procedures. However, according to the evaluation of the EU VAT system, the parallel introduction of the current transitional VAT system resulted in a very complex system for intra-EU trade in goods (as compared with the previous one) which led, as a consequence, to higher compliance costs for businesses trading cross-border as compared to businesses trading only domestically.

According to the evaluation, this complexity arises not only from the new specific VAT rules but also from other related provisions. In this regard, the statistical requirements that were put in place to allow identification of VAT-taxable transactions and to help record trade between Member States (the Intrastat system) have resulted in a substantial burden for intra-EU traders (estimated at 5% of the value of trade, with wide variation according to size and country).

A recent study confirmed the findings of the evaluation: on average, the VAT cost of compliance per euro of turnover is 11% higher for intra-EU trade compared with the corresponding VAT compliance per euro of turnover for domestic trade.

2.4.2.Introduction and VAT notions

The next sections describe the two main drivers leading to the complexity of the current transitional VAT system which are (i) the additional VAT obligations associated with the current transitional VAT system and (ii) the divergent application of the VAT rules across the Member States. They make reference to particular VAT notions. To avoid repetition, these VAT notions are explained in box 10 in Annex 5.

2.4.3.Driver 1: The additional VAT obligations associated with the current transitional VAT system

In comparison with domestic trade, doing business across the EU triggers additional obligations. These obligations are meant to ensure an "administrative" follow-up of the goods traded within the EU, in order to remedy the break in the VAT ‘audit trail’ resulting from the abolition of intra-EU border controls. In this regard, some stakeholders consider that the customs controls at the internal borders between Member States that were abolished in 1993 have been replaced by controls and administrative obligations shifted onto the economic operators. Moreover, they are of the view that there is no consistency between domestic and intra-EU cross-border supplies (see Annex 2).

Further feedback collected from expert stakeholders and Member States (see Annex 2) allowed identifying the main elements triggering these additional obligations which make trading in the EU more complex, and therefore more onerous, than engaging in domestic trade (see list of main additional obligations and further details in Section 7, box 11 in Annex 5). These obligations must be fulfilled in the Member State of establishment of the business and in any other Member State where the business performs economic activities. This requires particular investigations and maintenance of appropriate records and details, in addition to normal commercial documentation, if the VAT obligations linked to intra-EU transactions are to be fulfilled.

2.4.4.Driver 2: Divergent application of EU VAT rules across the Member States.

The complexity of the current transitional VAT system is partly the result of the divergent application of the EU VAT rules by the Member States. According to the evaluation of the EU VAT system, differential requirements for dealing with different tax administrations are the determinants of intra-EU additional transaction costs. The evaluation also pointed out that so long as the application of the EU VAT rules across the Member States varies, small businesses will undoubtedly continue to have considerable difficulties with intra-EU trade.

This further impacts on key issues like the place of taxation, leading to potential double taxation (to the detriment of businesses) or non-taxation (to the detriment of Member States). In this regard different application of the EU VAT rules by the Member States is seen by stakeholders as one of the most serious obstacles to benefiting from the single market (see Sections 2, 4, 5 of Annex 2). This is also the main reason why respondents (see Sections 2 and 6 of Annex 2) considered the current transitional VAT system to be extremely complex and creating high administrative burdens.

Such differences stem firstly from the numerous derogations and options in the VAT Directive, secondly from the discretion left to the Member States in their implementation and application and thirdly from divergent interpretations. These differences can affect the scope of the tax, the scope and number of exemptions, the chargeability of the tax, the structure of the VAT rates applied, formal obligations such as invoicing, the rules on deduction or the organisation and efficiency of the tax authority.

However, the focus of the initiative that is here being assessed, and of the in-depth discussions held with the Member States and expert stakeholders, is limited to the complexities resulting from differences that are specifically linked to the functioning of the current transitional VAT system.

The main differences can be grouped in the following two categories: (i) divergences in obligations and procedures imposed on businesses by the different Member States and (ii) divergences in the qualification of certain transactions and their VAT treatment between Member States (see list of main discrepancies and further details in Section 8, boxes 12 and 13 in Annex 5).

2.4.5.Consequences: who is affected and how?

·Member States: Ensuring business compliance with complex rules makes monitoring and audit tasks more difficult which results in higher administrative costs. Although national administrative practices established unilaterally by Member States can be held partly responsible for the complexity, a greater part is due to the rules laid down in the VAT Directive aimed to ensure the follow-up of the goods circulating VAT-free across the EU.

·Businesses: Businesses trading cross-border bear an extra compliance cost of 11% in comparison to businesses trading only domestically. Further there are additional risks associated with legal uncertainty for businesses engaged in cross-border trade. Those costs and risks can deter businesses, in particular SMEs, from trading across the EU. The functioning of the single market is therefore affected by the VAT rules as they influence where goods and services are produced, traded, bought and sold. This goes against the basic principle of neutrality governing VAT, according to which VAT must be neutral regarding economic activities.

The evidence collected through the whole consultation process (see Annex 2) demonstrates that the current transitional VAT system is extremely complicated and entails costs for businesses and difficulties for Member States when it comes to ensuring compliance. Complexity was pointed out as leading businesses to seek specialised advice when embarking in cross-border activities. The added cost was referred to as high and one which SMEs might not always have the resources to deal with. Moreover, errors were mentioned as resulting in substantial and sometimes disproportionate penalties. Complexity was also found to make it difficult for businesses to have legal certainty with regards to the VAT treatment of their transactions.

2.5.Conclusion

It results from the analysis of the problems that the functioning of the current transitional VAT system is causing disturbance to both Member States and businesses. The problems are interrelated since complexity creates opportunities for fraudsters and increased fraud leads to more complexity. These are problems that are exacerbated by the increase in cross-border activity that is the result of globalisation of the economy and the extension of the EU VAT area (from 12 to 28 Member States) since these rules entered into force in 1993.

2.6.Summary of main causes/consequences to the complexity of the current transitional VAT system

Table 2: Causes/consequences - Complexity of current transitional VAT system

|

|

VAT identification number

|

Liability rules for non-established business

|

Consignment/call-off stocks

|

Chain transactions

|

Proof of transport

|

VAT returns/

recapitulative statements/

audits

|

Supplies of goods and services

|

Input deduction

|

|

Main causes to the complexity

|

|

Divergent application of VAT rules

|

Divergent (des-) attribution process

|

Inconsistent application of reverse charge

|

Some Member States apply simplifications and others do not

|

No uniform rules on assignment of the transport to a specific supply in the chain

|

No clear and uniform rules

Different storage period

|

Different format, content and filing deadlines of VAT returns

Different requirements, format and deadlines for recapitulative statements

Different audit procedures

|

Inconsistent qualification

|

Different rules on exclusions and restrictions of the right to deduct and on calculation of deductible proportion

|

|

Additional VAT obligations

|

Need to validate status of customer

Need to be registered in another Member State/to have a fiscal representative

|

Need to be registered in another Member State in case no reverse charge is applicable in that Member State

|

Need to be registered in another Member State

|

Need to be registered in another Member State in case no simplification applies

|

Maintenance of appropriate records and details

Additional investigations

|

Need to submit VAT returns in other Member States

Need to add special mention in the VAT return

Need to present recapitulative statements

Subject to other Member States’ audits and need to have a fiscal representative

|

Need to investigate the treatment given in each Member State

|

Need for recourse to the refund procedure

|

|

Main consequences to the complexity (costs/risks)

|

|

|

Risk of being denied the exemption thus having to pay VAT without being able to pass it on to customer

Costs linked to multiple VAT registrations

|

Risk for customers to be held jointly and severally responsible

|

Risk of penalties if business applies simplification in a Member State which does not allow it

|

Risk of penalties if business applies simplification in a Member State which does not allow it

|

Risk of being denied the exemption thus having to pay VAT without being able to pass it on to customer

No common IT process possible

|

Risk of penalties if obligations not correctly fulfilled

|

Risk of double taxation or non-taxation

Administrative/

judicial claims

Need for recourse to tax experts

|

Refunds postponed (cash flow disadvantage)

|

2.7.Evolution of the problem without action at EU level (dynamic baseline)

2.7.1.Intra-EU cross-border VAT fraud perspective

For the time being, Member States and the Commission have joined efforts to combat MTIC fraud through the so-called "conventional measures", i.e. by improving administrative cooperation between the Member States. Amongst these measures are the set-up of the EUROFISC platform and the recourse to multilateral controls (i.e. controls involving tax administrations of more than one Member State).

In order to improve their fight against intra-EU cross-border VAT fraud, it is expected that Member States will continue reinforcing their cooperation in order to speed the exchange of quality information between them. The following upcoming proposals will soon be tabled by the Commission:

·A set of 20 measures by which urgent action will be taken on the following fronts:

-Improving cooperation within the EU and with non-EU countries.

-Moving towards more efficient tax administrations.

-Improving voluntary compliance and tax collection.

·Directive on the fight against fraud to the Union's financial interests by means of criminal law.

·Regulation on the establishment of a European Public Prosecutor's Office.

These measures are expected to help improve the fight against fraud in general. Improvements to the quality of information exchanged between the Member States and the speed of such an exchange through the use of electronic means will be particularly helpful in fighting against cross-border fraud. However, these measures alone would not be sufficient to radically reduce the level of cross-border fraud as they are not targeted at putting an end to the endemic weakness of the current transitional VAT system leading to the specificity of MTIC fraud.

2.7.2.Complexity perspective

Regarding the main issues linked to the complexity problem (need for certain transactions to be VAT registered/liable, need to comply with specific rules in Member States other than the Member State of establishment, proof of transport), any improvement would require a change in the EU rules.

Concerning the complexity linked to the VAT treatment/qualification of certain transactions, Member States might continue trying to agree common guidelines in the VAT Committee. However, this would be based on a case-by-case basis and further guidelines issued by the VAT Committee are merely views of an advisory committee. They do not bind either the European Commission or the Member States who are free not to follow them.

Regarding the input tax deduction, improvements to the cross-border intra-EU refund procedure have been introduced in 2010 (an electronic procedure for submission of the refund applications via a web portal only in the Member State where the business is established and not in all Member States where VAT has been incurred as under the old rules). While certain improvements could still be made by the Member States at national level (e.g. speeding-up the processing of applications, facilitating access to information and guidance as regards national implementing rules) there is no solution to overcome the cash flow disadvantage intrinsic to such a refund procedure.

2.7.3.Limits to the effectiveness of the current transitional VAT system

The current transitional VAT system was designed to provide a one-off solution to the abolition of the fiscal frontiers in 1993 and was a short-term practical system meant originally for four years. This system quickly showed its shortcomings which the Member States tried to address each in their own way. This has led to a fragmented VAT system, making intra-EU cross-border transactions difficult and risky for businesses, in particular SMEs. The consequence is that the VAT rules have the potential to see businesses refrain from trading across borders.

The development in recent years of e-governance has provided Member States' tax administrations new tools to improve their tax collection systems through better efficiency in collecting, processing, controlling and exchanging information. However, the pace of development but also the type of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) used differ from one Member State to another. This entails challenges for the cooperation between Member States' tax administrations not only in terms of technological factors but also from an administrative, legal and institutional perspective. If no fundamental solution is found at EU level, this might in turn entail that Member States focus on the development of own specific measures which deviate from the normal functioning of the VAT system.

The recent history of the VAT Directive shows the spill-over effect linked to the use of the reverse charge mechanism in an effort to combat MTIC fraud. Requests for derogating measures in order to introduce new methods for the collection of the VAT are also likely to continue. The solutions sought by the Member States are not only likely to increase fragmentation of the VAT system, but they can also lead to disproportionate or even legally doubtful measures. All this means a high risk that businesses will be faced with individual rules specific to each one of the Member States although the problem to solve is common to all of them. For these reasons, in the REFIT Platform, businesses called for a common solution.

As long as an EU-wide systemic solution is not put in place to counter the problems created by the current transitional VAT system, fraudsters and Member States will continue the endless loop of efforts in which the former will develop more aggressive fraud schemes while the latter will need to implement new control measures that will increase costs for both businesses and Member States.

Without action at EU level, the endemic weakness of the current transitional VAT system will continue to be exploited by fraudsters. Fraud levels might be stabilise but this will be to the detriment of compliant businesses that will pay the price through high compliance costs (already 11% higher than for domestic trade) or even increasing compliance costs.

The complexity of the current transitional VAT system will continue to negatively impact the functioning of the internal market by failing to capture new business models, new markets and technologies, which translates into losses of competitiveness of honest EU businesses and losses in efficiency of tax administrations.

3.Why should the EU act?

According to the principle of subsidiarity, as set out in Article 5(3) of the Treaty on European Union (TEU), action at EU level may only be taken if the envisaged aims cannot be achieved sufficiently by the Member States alone and can therefore, by reason of the scale or effects of the proposed actions, be better achieved by the EU.

VAT rules for cross-border EU trade can, by their nature, not be decided by individual Member States since, inevitably, more than one Member State is involved. Moreover, VAT is a tax harmonised at EU level. The problems identified in Section 2 of this impact assessment are embedded in the rules of the VAT Directive. Therefore any initiative to change the current transitional VAT system into a definitive system as regards intra-EU trade requires amending the current VAT Directive. This entails a proposal from the Commission and its adoption by the Council, acting unanimously in accordance with a special legislative procedure, and after consulting the European Parliament and the Economic and Social Committee.

The legal basis for the present initiative is Article 113 of the TFEU according to which: "The Council shall, acting unanimously in accordance with a special legislative procedure and after consulting the European Parliament and the Economic and Social Committee, adopt provisions for the harmonisation of legislation concerning turnover taxes, excise duties and other forms of indirect taxation to the extent that such harmonisation is necessary to ensure the establishment and the functioning of the internal market and to avoid distortion of competition".

Given the need to modify the VAT Directive, the objectives sought by the present initiative cannot be achieved by the Member States themselves. Therefore, it is necessary for the Commission, which has responsibility for ensuring the smooth functioning of the internal market and for promoting the general interest of the European Union, to propose action to alter and improve the situation.

As regards the provisions to harmonise and simplify rules within the current transitional VAT system (the "quick fixes"), they have unanimously been requested by the Member States which demonstrates that action at Union level is likely to be more effective as action at national level has proven not to be sufficiently successful.

Furthermore, the 2011 retrospective evaluation (see annex 6) already referred to the "piecemeal" approach by Member States as an unsatisfactory way to solve the problems of the transitional arrangements.

4.What should be achieved?

4.1.General objectives

The general objectives of the initiative are:

·To contribute to fiscal consolidation within the EU – by ensuring that taxes due are collected to feed national and EU budgets.

·The smooth functioning of the internal market – by reducing obstacles to intra-EU cross-border trade.

·To ensure fair taxation – so that all businesses are treated equally in order to avoid distortions of competition.

4.2.Specific objectives

The specific objectives of the initiative are:

·To make the EU VAT system more robust – by addressing the endemic weakness of the current transitional VAT system linked to the break in the fractional collection of VAT.

·To make the EU VAT system simpler – by addressing the complexities of the current transitional VAT system and by providing a level playing field for businesses whether engaged in domestic or cross-border transactions.

4.3.Linking the objectives to the problem

Table 3: Links objectives-problems-solutions

|

Specific objectives

|

Link to the problems and criteria for reaching a solution

|

|

To make the EU VAT system more robust – by addressing the endemic weakness of the current transitional VAT system

|

Addresses the problem of intra-EU cross-border VAT fraud

Meets the following general objectives:

·To contribute to fiscal consolidation within the EU

·To ensure fair taxation

The assessment of possible solutions is based on the following qualitative criteria*:

·Budgetary impact

·Prevention of fraud and abuse

|

|

To make the EU VAT system simpler – by addressing the complexities of the current transitional VAT system and by providing a level playing field for businesses whether engaged in domestic or cross-border transactions

|

Addresses the problem of complexity of the current transitional VAT system

Meets the following general objectives:

·The smooth functioning of the internal market

·To ensure fair taxation

The assessment of possible solutions is based on the following qualitative criteria:

·Equality and simplicity;

·Ease of administration and cost of collection;

|

*Qualitative assessment criteria:

·Equality and simplicity – Domestic and intra-EU transactions should be treated the same so that doing business across the EU becomes as simple (reducing compliance costs) and as safe (providing legal certainty) as engaging in purely domestic activities. Rules should not be an obstacle to the proper functioning of the single market.

·Budgetary impact – VAT revenues should be allocated to the Member State of the final consumption of the goods in accordance with its conditions in particular its VAT rates. The impact on the cash-flow of business should be similar to that for domestic transactions to ensure a genuine level playing field.

·Ease of administration and cost of collection – An increase in costs for the tax administrations and business should be avoided in order to allow that the cost of collecting tax revenues is similar to that for domestic transactions.

·Prevention of fraud and abuse – Breaks in the VAT chain within the single market should be avoided to the extent possible to ensure that the VAT system remains robust and fraud-proof.

4.4.Consistency with other EU policies and with the Charter for fundamental rights

The creation of a simple, modern and fraud-proof VAT system is one of the fiscal priorities set out by the Commission for 2017 (Annual Growth Survey 2017) which should contribute to deepening the single market and making national markets bigger.

The main objectives of the initiative of reducing cross-border VAT fraud and lowering compliances costs for businesses trading across the EU by using new technologies are in line with this priority. The initiative would prompt Member States to put in place modern tax systems that can support growth and fairness between businesses and bring a new level of cooperation between Member States and between Member States and businesses to improve tax collection.

MTIC fraud is also one of the nine

, the European Union’s priority crime areas, under the 2014-2017 EU Policy Cycle of Europol.

Reducing administrative burdens, particularly for SMEs, is also an important objective highlighted in the EU’s growth strategy for the coming decade (Europe 2020 – A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth).

The proposed initiative and its objectives would be consistent with the EU SME policy as set out by the Small Business Act (SBA), in particular principle VII on helping SMEs to benefit more from the opportunities offered by the Single Market. It would be consistent with the Single Market Strategy (SMS) which referred to the single European VAT area mentioned in the Action Plan. It would also be consistent with the EU objectives under REFIT.

The objectives envisaged do not affect fundamental rights.

5.What are the various options to achieve the objectives?

5.1.Selection of options

When looking at possible options to tax B2B transactions at destination, two fundamental issues have to be considered, namely:

·the place of taxation (whether it will be based on the physical flow of the goods or not); and

·the person liable for payment of VAT (whether the supplier charges the VAT of the Member State of destination and pays the VAT via the One Stop Shop or if instead the customer accounts for the VAT through the reverse charge).

The following qualitative assessment criteria were suggested and agreed by both the GFV and the VEG: (i) equality and simplicity; (ii) budgetary impact; (iii) ease of administration and cost of collection; and (iv) prevention of fraud and abuse (see Section 4.3 above).

On the basis of the outcome of a series of technical discussions in the GFV and the VEG on the possible options , in addition to the Baseline, the five options discussed in the next section were selected (out of thirteen different options initially identified in close collaboration with stakeholders in the VEG and representatives of Member States in the GFV) to be assessed in-depth in an external study.

5.2.Baseline

The baseline option assumes that no legislative action will be taken at EU level as regards the VAT treatment of cross-border transactions and that the current transitional VAT system will continue to apply. The functioning of the current transitional VAT system as such is described in Section 1.4 Functioning of the common system of value added tax and Box 2: Transitional VAT system since 1993.

The baseline takes into account the current applicable rules and not those which are contained in proposals currently discussed in Council or which might be adopted by the Commission in the future. However, it seems appropriate to dwell on the impact that those proposals might likely have in case they would be adopted.

A reference is needed, in the first place, to the VAT proposals on e-commerce, on a Generalised Reverse Charge Mechanism (GRCM - see footnote 83) and on reduced VAT rates on e-publications that are currently under discussion in the Council. While once adopted the e-commerce proposal should have positive effects on the baseline as it is expected to raise Member States' VAT revenues and decrease compliance costs to businesses, the effect of the adoption of the other proposals is uncertain, especially concerning the GRCM which might pending its final design result in further fragmentation of the VAT system and have negative impact on compliance costs of business.

Finally, it is appropriate to make a reference to the impact that in the baseline might entail the adoption of the three other VAT legislative proposals (rates, SMEs and administrative cooperation) which, according to the VAT Action Plan, should be adopted by the Commission in the near future.

The VAT rates proposal could be adopted even in the absence of an adoption of the initiative on the definitive VAT system. The current transitional VAT system is indeed de facto based on the destination principle which limits the distortions of competition due to the differentiation of VAT rates between the Member States. As the current transitional VAT system would continue to apply, the business customer will also continue to self-assess the VAT due on his cross-border purchases in his own Member State.

The proposals on the SME VAT Package and on administrative cooperation could also be adopted even in the absence of an adoption of the initiative on the definitive VAT system. Only the specific parts of these proposals linked to the initiative on the definitive VAT system would need to be adapted. Both proposals should on their own have positive impacts on administrative and compliance costs once adopted. Further the proposal on administrative cooperation should also have a positive impact regarding the problem of cross-border VAT fraud.

The baseline option will serve as the benchmark against which the other options will be assessed.

5.3.Option 1: Limited improvement of current rules

Option 1 consists in improving the current rules for intra-EU B2B supplies of goods without modifying them fundamentally. This means that the underlying principles and functioning of the transitional VAT system for intra-EU supplies of goods would remain unchanged (see also Diagram 1 in Section 10 of Annex 5 for its functioning).

The improvements that would be made to the current system under this option cover very specific set of rules that have been identified by national tax administrations and stakeholders, in particular during the consultation process, the discussions in the GFV, the VEG and by way of feedback from the REFIT platform, as the main areas of the existing legislation where legal clarity and certainty need to be enhanced. As requested by the Council in its conclusions on "Improvements to the current EU VAT rules for cross-border transactions" adopted on 8 November 2016, the following four issues will be addressed:

1)The legal value of the VAT identification number of the customer as regards the exemption for the intra-EU supplies of goods in the Member State of departure of the goods

Providing a valid VAT identification number of the purchaser would become a substantive condition (and not merely a formal condition, as stated by the CJEU with regards to the current VAT rules) for applying the exemption of intra-EU supplies of goods. This modification would be proposed in reply to the demand made by Member States to amend the current VAT Directive in order to allow for better monitoring of the flow of goods using the recapitulative statements and the VIES system.

2)The VAT treatment applied to call-off stock arrangements

Call-off stock refers to the situation where a supplier moves stock to a Member State where he is not established, in order to sell it at a later stage to an already known buyer. Currently this gives rise to (i) a (deemed) intra-EU supply made by the transferor, (ii) a deemed intra-EU acquisition in the Member State of arrival of the goods made by the transferor (who has to register there), (iii) a domestic supply. The proposed amendment under Option 1 would consist in treating the cross-border transfer of goods and subsequent domestic sale as a single exempt intra-EU supply, with an intra-EU acquisition of goods made by the buyer (thus avoiding any obligations for the transferor in the Member State of arrival of the goods).

3)The VAT treatment applied to chain transactions

Chain transactions refer to cases where multiple parties are involved in one commercial transaction: company A sells to B, who sells to C, who sells to D and the goods are transported directly from company A to D, so B and C are simply intermediaries. Under the current VAT rules it is difficult to determine which supply involves the intra-EU movement of goods (which will be the only exempt supply in the chain). The proposed amendment under Option 1 would consist in establishing a legal presumption in this regard, which would bring legal certainty to tax administrations and businesses.