EUROPEAN COMMISSION

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Brussels, 26.2.2020

SWD(2020) 515 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

Country Report Luxembourg 2020

Accompanying the document

COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE EUROPEAN COUNCIL, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK AND THE EUROGROUP

2020 European Semester: Assessment of progress on structural reforms, prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances, and results of in-depth reviews under Regulation (EU) No 1176/2011

{COM(2020) 150 final}

Contents

Executive summary

1.Economic situation and outlook

2.Progress with country-specific recommendations

3.Reform priorities

3.1.Public finances and taxation

3.2.Financial sector25

3.3.Labour market, education and social policies33

3.4. Competiveness and Investment44

3.5.Environmental sustainability54

Annex A: Overview Table59

Annex B: Commission Debt Sustainability Analysis and Fiscal Risks64

Annex C: Standard Tables65

Annex D: Investment guidance on Just Transition Fund 2021-2027 for Luxembourg71

Annex E: Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)72

References77

LIST OF Tables

Table 1.1:Key economic and financial indicators

Table 2.1:Overall assessment of progress with 2019 CSRs - Luxembourg

Table 3.2.1:Key Financial Performance indicators

Table 3.2.2:Key Insurance Figures

Table C.1:Financial market indicators

Table C.2:Headline Social Scoreboard indicators

Table C.3:Labour market and education indicators

Table C.4:Social inclusion and health indicators

Table C.5:Product market performance and policy indicators

Table C.6:Green growth

Table E.1:Indicators measuring Luxembourg’s progress towards the SDGs

LIST OF Graphs

Graph 1.1:

Real GDP growth (y-o-y %) with contributions and output gap

Graph 1.2:

Real GDP level relative to 1995 (1995 = 0) and contributions (pps cumulated)

Graph 1.3:

Real GDP level relative to 1995 (1995 = 0) and contributions (pps cumulated)

Graph 1.4:

Employment growth cumulated and contributions by residence (2000=0)

Graph 1.5:

Labour productivity level relative to 1995 and contributions (percentage points)

Graph 1.6:

Contributions to potential growth - Luxembourg

Graph 1.7:

Foreign direct investment position, gross components - Luxembourg (euro trillion)

Graph 1.8:

Current account, gross components - Luxembourg.

Graph 1.9:

Difference between GDP and GNI (euro billion)

Graph 1.10:

OUTSTANDING LOANS TO THE NON-FINANCIAL PRIVATE SECTOR (YoY %)

Graph 2.1:

Luxembourg - Level of implementation today of 2011-2019 CSRs

Graph 3.1.1:

Outgoing interest payments in the EU and share going to offshore financial centres. Average 2013-2017, (€ billion)

Graph 3.2.1:

Five main open-end funds jurisdictions, Q2 2019 (% of world total net assets)

Graph 3.2.2:

Persons employed in the financial sector

Graph 3.2.3:

Luxembourg banks - Aggregate profits and losses

Graph 3.2.4:

Net assets under management, € trillion

Graph 3.2.5:

Non-Financial Corporations Indebtedness Ratios

Graph 3.2.6:

Key households indebtedness ratios

Graph 3.2.7:

Evolution of mortgage loans and real housing prices

Graph 3.2.8:

Evolution of housing prices compared to valuation benchmarks

Graph 3.3.1:

Activity, unemployment, long-term unemployment, youth unemployment and NEET rates

Graph 3.3.2:

Unemployment rate and potential additional labour force

Graph 3.3.3:

Employment rate by educational attainment

Graph 3.3.4:

Dispersion of employment rates by level of education

Graph 3.4.1:

Labour productivity evolution (2010=100)

Graph 3.4.2:

Share of services in final demand

Graph 3.4.3:

Evolution and composition of the GVA created by the ICT sector

Graph 3.4.4:

Labour productivity growth in information and communication technologies (ICT)

Graph 3.4.5:

Evolution of the GVA created by the logistics sector

LIST OF Boxes

Box 2.1: EU Funds and Programmes to address structural challenges and to foster growth and competitiveness in Luxembourg

Box 3.3.2: < Monitoring performance in light of the European Pillar of Social Rights >

Box 3.3.3: Labour shortages and skills gaps in Luxembourg’s labour market in a multidimensional perspective

Box 3.4.4: Investment challenges and reforms in Luxembourg

Executive summary

Whereas growth prospects remain shaped by a less supportive external environment, to which the economy is highly sensitive, Luxembourg has made some progress in diversifying its economy, potentially easing the way to a more resilient growth path. Some progress was achieved by focusing investment on fostering digitalisation and innovation, stimulating skills development and developing the transport system. The resilience of the economy would be further strengthened by encouraging private investment and fostering technological diffusion and innovation among firms, while also further improving sustainable transport infrastructure and housing supply. The country could also bolster its economy and improve the conditions for sustainable growth that benefits the whole of society by ensuring that the labour supply and skills levels match labour market needs. This, in turn, would help to better address the long-term health of government finances ().

Economic growth has slowed and is set to stabilise. After reaching 3.1 % in 2018, GDP growth is estimated to have slowed to 2.6 % in 2019. It was driven by stronger domestic demand, partly offsetting the weaker contribution from the external sector. Consumer spending growth also strengthened in 2018, building on an improvement in the labour market and higher disposable incomes, resulting from taxation reforms and wage indexation.

Despite a less dynamic growth trend, Luxembourg’s economy is projected to continue outpacing growth in the EU as a whole. Growth in Luxembourg’s annual real GDP (adjusted for inflation) averaged 3.2% in the period 2010-2018, compared with an EU average of 1.4%. The economy is set to continue growing at a steady pace over the coming years. Against a backdrop of global uncertainty, regulatory and technological changes, and weak profit expectations, business investment is expected to remain subdued, despite favourable financing conditions. By contrast, public investment may increase faster.

Luxembourg’s government finances remain sound but concerns remain for the long term. The general government balance is estimated to have posted a surplus of around 2.7% of GDP in 2019 and it is forecast to remain in surplus in 2020. General government debt is expected to continue to fall in 2020, from an already low level of around 20% of GDP in 2019. Concerns remain regarding the long-term sustainability of public finance. From now until 2070, Luxembourg is expected to face one of the sharpest increases among the EU countries in ageing-related spending (pensions, long-term care, and healthcare costs). With no policy change, this would have a major impact on public debt.

Investment remains relatively weak in sustainable housing and transport infrastructure, research and innovation, and digitalisation, especially in the business sector. This might slow down the development of activities that add higher value to the economy. Greater private investment in research, technological innovation and digitalisation may ease the transition to a data-driven economy. Investment in sustainable housing is insufficient for the level of demand, and housing prices have increased further. Growth that benefits all of society might largely depend on education and lifelong learning.

Overall, Luxembourg has made limited () progress in addressing the 2019 country-specific recommendations.

There has been some progress in the following area:

·Focusing economic policy related to investment on fostering digitalisation and innovation, stimulating skills development and improving sustainable transport.

There has been limited progress in the following areas:

·Increasing employment among older people, by enhancing their employment opportunities and employability, and further limiting early retirement.

·Further reducing regulatory restrictions in the business services sector. Despite some recent changes, such restrictions remain above the EU average in most regulated professions.

·Increasing the housing supply, including by increasing incentives and lifting barriers to build.

·Addressing features of the tax system that may facilitate aggressive tax planning, in particular by means of outbound payments.

There has been no progress in the following area:

·Improving the long-term sustainability of the pension system, including by further limiting early retirement.

Luxembourg performs well overall on most indicators of the Social Scoreboard supporting the European Pillar of Social Rights. The labour market is performing rather well, and indicators on inequality, poverty and social exclusion remain close to or better than the EU average, despite some signs of weakening. Significant skills shortages have emerged recently in certain sectors and school pupils’ opportunities are still strongly influenced by their socio‑economic status.

Luxembourg’s progress towards its national targets under the Europe 2020 strategy paints a mixed picture. The employment rate target of 73% is still out of reach despite substantial job creation. Luxembourg almost meets the municipal waste recycling target of 50% and is broadly on track to reach the targets for energy efficiency. On the other hand, it is at risk of failing to achieve the targets for reducing the risk of poverty or social exclusion, the school drop-out rate (‘early school leaving’), post-secondary educational attainment, research and development intensity and reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Overall, Luxembourg performs well in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. This is particularly the case for ’Good Health and Wellbeing’ (SDG 3). Some deterioration can be observed, however, in indicators related to the reduction of inequalities (SDG 10) ().

Despite robust job creation, the proportion of people in certain population groups who are working or looking for work remains insufficient. Employment continued to increase in 2018 and in the first three quarters of 2019 and at 5.5% unemployment is low. The youth unemployment rate fell to 13.8% in the first three quarters of 2019, while the rate of young people not in employment, education or training is one of the lowest of the EU. The employment rate of older workers went up in 2018, to reach 40.5% but it remains substantially below the EU average. Older and low-skilled workers, especially those with a migrant background, are less likely to find or stay in work.

The labour market remains robust, but many firms have difficulties filling vacancies. Ensuring that the labour supply and skills match labour market needs is key to achieving growth that benefits the whole of society. The public employment service continues to cooperate with employers to address the most critical skills shortages and the government has announced reforms to ensure the quality and relevance of training.

The overall risk of poverty or social exclusion increased in 2018, reaching the EU average (21.9%). The impact of social benefits in lifting people out of poverty remains strong, but it has been weakening since 2015 and income inequality rose in 2018. The proportion of people in work at risk of poverty is still among the highest in the EU. In this context, the newly implemented Revenu d'inclusion sociale, an activation benefit consisting of an allowance for activities organised by the social inclusion office, such as community work or activities favouring social stabilisation, is expected to help reduce poverty.

Education performance is below the EU average and closely linked to socioeconomic status. Luxembourg’s average performance, worsened between 2012 and 2018. The impact of socio-economic status on performance is one of the strongest in the EU. In response to this challenge, the government has taken measures to close the achievement gap between pupils of different backgrounds and to reduce early school leaving rates.

Key structural issues analysed in this report, which point to particular challenges for Luxembourg’s economy, are the following:

·Recent reforms have not addressed concerns regarding the long-term sustainability of the pension and long-term care systems. Long-term projections for pensions and long-term care spending point to risks to the sustainability of government finances. Several measures have been adopted, but their impact has been limited. More fundamental reforms have not been considered yet or are pending approval, such as the ‘Age Pact’, which is intended to keep workers in employment for longer.

·Evidence suggests that Luxembourg’s tax rules are used for aggressive tax planning. Specifically, the absence of or exemption from withholding taxes on outbound payments is a cause for concern. Reforms in Luxembourg have focused on the implementation of European and internationally agreed initiatives, and Luxembourg reported that it plans to address the issue of outbound payments.

·Despite clearly identified money laundering risks linked to the misuse of legal entities, application of anti-money laundering measures by certain professionals providing services to companies and trusts should be further enhanced. The low reporting of suspicious transactions/activities by such professionals, the sector’s fragmentation and the widespread use of complex legal structures make it difficult to implement preventive measures. Effective supervision and guidance, and properly functioning beneficial ownership registers are key to mitigate risks.

·Luxembourg’s financial sector is well integrated in the international financial industry’s global value chain and continues to drive economic growth. The financial sector is the main economic engine, accounting for 25 % of GDP and 11 % of employment. Luxembourg’s banks display solid capital ratios, although their profitability has weakened due to the low interest rate environment and rising operational and regulatory costs.

·Households have high levels of debt compared to their incomes. Rising household indebtedness stems in particular from increasing property prices, as mortgage loans account for most of household debt. Increasing debt means that some lower income households may struggle to make ends meet if interest rates go up or if there is an economic downturn.

·Housing prices continue to increase, driven by the large gap between demand and supply. Housing demand is influenced by dynamic population growth, benign financing conditions and a large cross-border workforce. Housing supply and investment are insufficient, largely due to a lack of incentives for landowners to build new housing and to an insufficient supply of social housing.

·Relatively weak investment in research and innovation, especially in the private sector, weighs on Luxembourg’s innovation potential. This might slow down the development of activities that add higher value to the economy. Stronger private investment in research, technological innovation and digitisation can be key drivers of productivity growth and ease the transition to a data‑driven economy. The connection between the public science base and businesses is weak, limiting firms’ potential for innovation. The lack of a national research and innovation strategy and insufficient public support for business research and development investment, are just two of the challenges that prevent Luxembourg from exploiting the full potential of its innovation eco-system.

·Regulatory barriers remain in the business services sector, and some bottlenecks weigh on the business environment. Regulatory restrictions in business services remain above the EU average for several economically important professions. Measures have been taken to ease restrictions in the retail sector.

·Despite challenges on climate, energy and mobility, the green transition offers growth opportunities. The country is the EU’s highest greenhouse gas emitter per capita. With existing measures, it would fall short of its 2030 target for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. This highlights the considerable efforts needed to deliver on Luxembourg’s climate and energy objectives, in particular in the transport and housing sectors. The National Energy and Climate Plan (still to be delivered by Luxembourg’s authorities at the time of writing)will outline the scope of the envisaged policy response and will play a key role to assess investment needs. The impact of the transition on some economic sectors and households is likely to require mitigating policies, the costs of which still need to be quantified. Road traffic congestion weighs on the economy and environmental sustainability, and Luxembourg is investing in a more sustainable mobility. Its financial sector has taken innovative steps in the sustainable finance market, while eco-innovation and circular economy policies can support job creation and the diversification of the economy.

·A Just Transition Mechanism under the next multi-annual financial framework for the period 2021-2027 will contribute to ensuring that the transition towards EU climate neutrality is fair by helping the most affected regions in Luxembourg to address the social and economic consequences. Key priorities for support by the Just Transition Fund, set up as part of the Just Transition Mechanism, are identified in Annex D, building on the analysis of the transition challenges outlined in this report.

1.

Economic situation and outlook

GDP growth

Economic growth in Luxembourg is set to weaken, mostly due to external headwinds. Real GDP growth in Luxembourg is set to have reached 2.6% in 2019, a moderate slowdown compared with the 3.1% for 2018. Growth was driven by stronger domestic demand, partly offsetting the weaker contribution from the external sector (Graph 1.1). Private consumption picked up in 2018 and the resulting higher growth momentum was maintained in 2019, accompanied by robust job creation. Employment growth remained above 3½% in 2018 and 2019. Another stimulus for consumption was provided by expected income gains from the automatic wage indexation mechanism. Wage growth was 3.6% on an annual basis in 2019 and an indexed increase was triggered on wages and pensions in December 2019 and applied in January 2020. These factors concurred in a period of relatively lower inflation (1.6% in 2019, with stable prospects for 2020, after 2.0% in 2018) to further support private consumption growth in 2020 ().

Despite a less dynamic growth trend, Luxembourg’s economy is projected to continue outpacing growth in the EU. Luxembourg's annual real GDP growth averaged 3.2% in the period 2010-2018, compared with 1.4% for the EU average. The economy is set to continue growing at a steady pace, around 2½% over the coming years (around 1.5 percentage points faster than growth expected in the EU). On the face of favourable financing conditions, business investment is expected to remain subdued, against a backdrop of global uncertainty, regulatory and technological changes and weak profit expectations. By contrast, public investment may accelerate. On the fiscal side, the government has gathered robust buffers and has recently stepped up financial efforts to support its main policy objectives, as announced in the 2020 budgetary plan, which would keep public investment above 4% of GDP in the coming years (Section 3.1).

|

Graph 1.1:Real GDP growth (y-o-y %) with contributions and output gap

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|

|

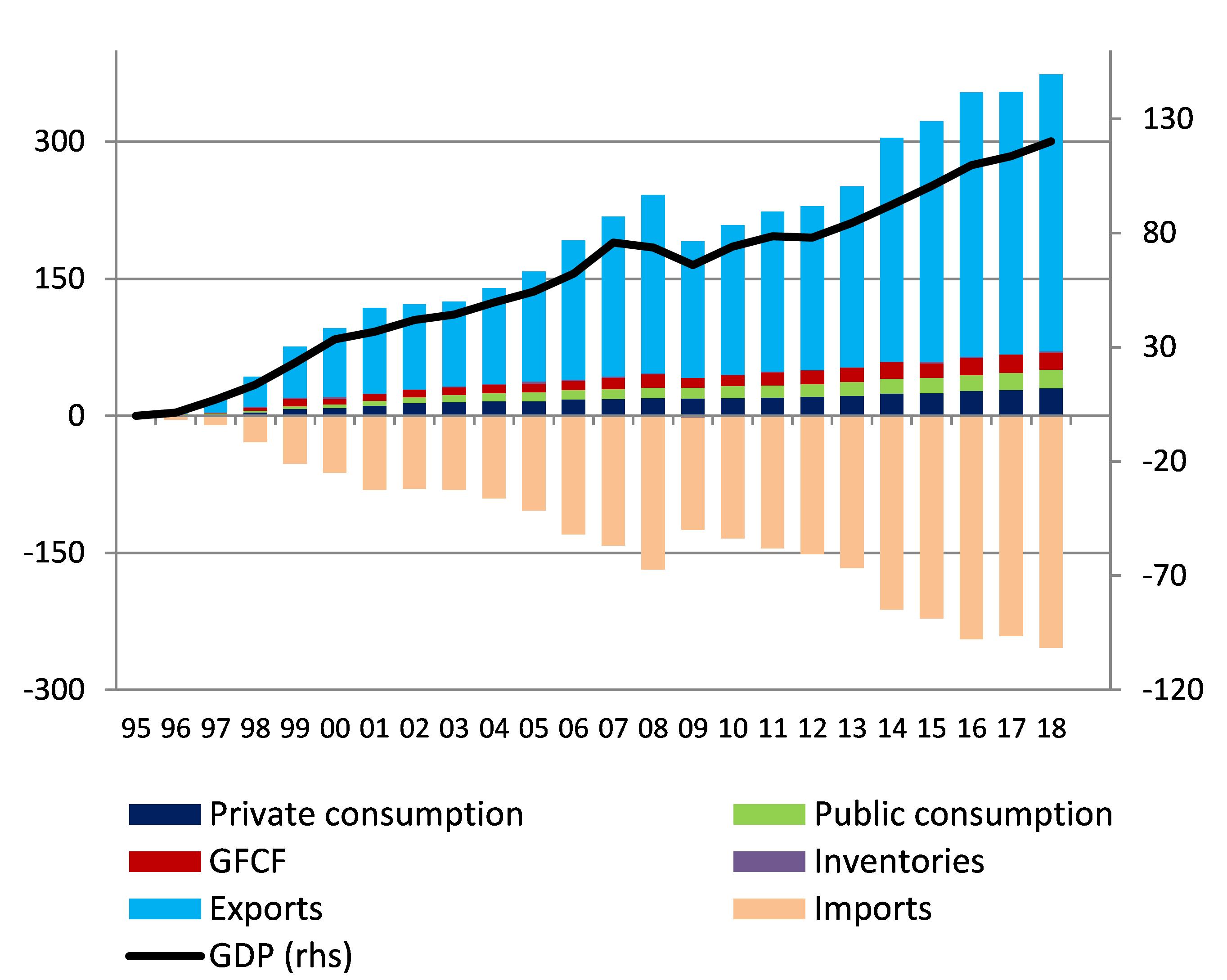

Graph 1.2:Real GDP level relative to 1995 (1995 = 0)

and contributions (pps cumulated)

|

|

|

|

Source: STATEC. (European Commission calculations)

|

Indicators point to a weakening of economic growth, especially in the financial sector, traditionally Luxembourg's economic engine. Luxembourg is a small open economy with a relatively large international financial sector. In 2018, real GDP was 120% higher compared to its level in 1995. Net exports contributed 50 percentage points to growth (Graph 1.2), 80% of which were from financial services. After the crisis, the contribution from financial services has been relatively lower, reflected in real GDP growth. Recently, market deepening has slowed somewhat, although Luxembourg maintains high productivity gains, accumulated in the past from access to external markets. While GDP growth appears rather stable in 2019, Luxembourg trading partners have been more affected by the current slowdown. Increased uncertainty is weighting on international trade and some international integrated production structures may be affected. Overall, the economy is expected to grow at a slower pace in the coming months.

|

Graph 1.3:Real GDP level relative to 1995

(1995 = 0) and contributions (pps cumulated)

|

|

|

|

Source: Eurostat

|

Luxembourg shows high dependence to foreign trade, as it contributes strongly to economic activity. Although at a slower pace, trade integration has expanded further and the large gross trade flows are increasingly higher, compared with the net exports balance (Graph 1.3). Luxembourg displays one the highest levels of market integration among the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, with both exports and imports accounting for more than twice the level of GDP. Intermediate inputs account for the largest share of the country's trade. National Accounts data show that around 70% of operating costs are determined by intermediate inputs, more than half of which are imported. High market integration also implies higher exposure to external shocks to the supply chain, whereas barriers to trade have a cumulative impact on costs thus on competitiveness (Section 3.4.1).

Labour market

The labour market remains robust. Employment growth peaked at the beginning of 2018 at 3.9% over one year. This strong pace of job creation was maintained at around 3.7%, on average, in the period 2018‑2019 before employment started slowing down in September 2019. Even though growth was never close to pre-crisis rates, Luxembourg’s labour market has remained one of the most dynamic among the EU Member States. Employment growth is expected to continue decelerating in 2020 in line with the global economic slowdown.

|

Graph 1.4:Employment growth cumulated

and contributions by residence (2000=0)

|

|

|

|

Source: Eurostat

|

Luxembourg's economy is highly labour intensive. Employment increased by 70% in the period 2000-2018 (Graph 1.4). At the same time, employment growth was 17% in Belgium, 12% in Germany, 9.8% in France and 6.8% in the whole of the European Union. In the aftermath of the economic crisis of 2008, employment declined in the EU for two consecutive years. In Luxembourg, only cross‑border employment fell marginally. Cross-border workers, i.e. people who do not live in Luxembourg but commute there every day for work, account for 41% of paid employment. Cross-border employment appears to be more sensitive to economic developments than resident employment and it has often acted as a buffer for resident workers and the economy. Favourable employment conditions have also attracted a large number of migrant workers. As a result, population has increased by 40% in the period 2000-2018, among the largest increases in the EU. Migrant population count is almost at the same level as resident people born in Luxembourg.

Competitiveness and investment

Cost competitiveness conditions in Luxembourg appeared stable in 2018. Nominal compensation per employee grew by 3.3% in 2018 and it is expected to continue growing in 2019 and 2020, albeit at a slightly lower pace. In 2019 nominal compensation per employee is expected to grow with 3.2%, a faster pace than the internal wage benchmark (0.2%), which is a predicted nominal compensation based on inflation, productivity and unemployment (European Commission, 2019). With inflation also growing, real wages have seen a rather moderate increase of 0.7% in 2018 and 1% in 2019. Market shares appeared also relatively stable in 2018. The role of domestic and foreign services is particularly important for explaining the aggregate competitiveness in Luxembourg (Section 3.4.1).

Measuring and interpreting Luxembourg's productivity is specially challenging. This is due to the uncertainty surrounding national statistics on external trade and the large difference between GDP and Gross National Income. Ratios based on GDP (either as numerator or denominator) do not take account of outflows of foreign income, while ratios based on population do not account for the number of cross-border workers, which would raise the population count by 30%. The OECD () has reported that other categories of the population live temporarily in the country but are not registered as residents. This is the case, for instance, of posted workers () (around 6% of resident population in 2016) or tertiary education students (more than 70% of all tertiary education students in Luxembourg). Altogether, the number of non-resident workers is equivalent to 60% of Luxembourg’s resident population, according to OECD estimates, accounting for 67% of full time equivalent employment. On a similar note, traditional statistics on the trade of gross exports and imports may be inflated by re-imported exports in the presence of global value chains, while some intragroup accounting practices may have a large impact on reported foreign direct investment values. Additional caution is required when interpreting some model-based results computed using these variables as inputs. For instance, total factor productivity for Luxembourg, given the large number of non-resident workers.

Luxembourg enjoys a very high level of productivity compared with other EU countries. However, productivity growth has been lagging behind. In the period 1995‑2018, productivity in Luxembourg increased by 0.3% on average per year, compared with 1.0% in Belgium, 1.4% in France and Germany and 1.6% for the EU average. Against this background, positive wage differentials with trade partners in the euro area might translate into competitiveness losses that cumulate over time, while the drivers that had boosted the financial sector expansion in past decades appear to be waning (2019 Country Report for Luxembourg, European Commission). Even though most advanced countries have seen productivity slowing down as from the early 2000s, Luxembourg’s weaker dynamics do not appear likely to be fully explained by the increasing share of services observed in most EU Member States (). Moreover, Luxembourg’s trade openness and its financial specialisation had begun at an earlier stage and was already quite advanced in 2000.

Both employment and GDP tend to grow at a similarly strong pace over time, which keeps labour productivity growth barely changed. Graph 1.5 presents a decomposition of the labour productivity level relative to 1995 and its components GDP and employment cumulated changes (the latter with a negative sign), for the whole economy. As shown in figure 1.5, high labour intensity is also concurrent with a high elasticity of employment (close to one in cumulated terms). This means that employment and GDP in levels tended to increase at a similar pace in the period 1995‑2018, which implies that labour productivity growth remained close to zero while the economy was generating robust economic growth and strong job creation on a sustained basis.

|

Graph 1.5:Labour productivity level relative to 1995

and contributions (percentage points)

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|

Productivity gains originating from high annual GDP growth rates might not be sustainable. The adjustment of employment is persistently slower than GDP growth. In a context of strong employment demand, firms may not swiftly adjust employment in response to a slowdown (). Inversely, employment supply may not react immediately when demand picks up. Figure 1.5 shows how employment did not react accordingly, during both recent slowdowns in the period 2008‑2009 and 2012. There seems to be further evidence of some resistance in the adjustment pace of employment. As a result, annual productivity growth appears to be mostly driven by GDP growth, with a persistent positive gap between annual changes in GDP and productivity (). Short‑term productivity gains correspondingly are obtained when GDP grows above the amount of this gap on a sustained basis.

Given the high labour intensity of the economy, there may be potential to raise productivity in the long term via increasing capital deepening. Gross fixed capital formation persistently shows one of the lowest records, in terms of GDP, among the EU Member States. In this vein, the contribution of capital stock to potential GDP growth has declined in recent years (Graph 1.6). Moreover, there seems to be a stronger correlation between the contributions of capital accumulation and total factor productivity to potential GDP growth (). These trends suggest untapped potential to raise productivity and potential growth through capital investment.

|

Graph 1.6:Contributions to potential growth - Luxembourg

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|

Compared with the high potential of the digital and technological environment, technological integration is low in the broad business sector, while private investment remains weak. Public investment is high, in support of knowledge-intensive activities. For years, Luxembourg has focussed on developing a few selected knowledge-intensive clusters to diversify the economy. Among them, the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) sector has thrived and matured, and can play a pivotal role in improving the digital integration in the economy. However, this favourable environment has not leveraged private investment, including in research and innovation (OECD economic surveys: Luxembourg 2019, p.49, Digital Economy and Society Index 2019; EIB Investment Survey Luxembourg 2019), which remains weak in a long-term perspective, in line with the low digital integration in the broad business sector. All this points, in turn, to an inability by firms to reap productivity gains from leveraging investments on the country's digital and technological environment, despite its high potential (Section 3.4).

Capital markets

Luxembourg’s foreign direct investment (FDI) positions contracted further in 2018. Luxembourg's FDI is concentrated in a few financial holding companies (SOciétés de PARticipations FInancières, SOPARFI), which channel FDI from foreign investors to foreign recipients, representing almost 95% of both total FDI assets (outward investment) and FDI liabilities (inward investment) in Luxembourg. Both liabilities and assets contracted by €343 billion and €315 billion, respectively, in 2018 (Graph 1.7). This contraction was explained by divestments, which have been observed since the second half of 2017. These operations concerned a number SOPARFIs, which either restructured, or ceased or relocated their activities (BCL, 2019).

|

Graph 1.7:Foreign direct investment position, gross components -

Luxembourg (euro trillion)

|

|

|

|

Source: Eurostat

|

The recent FDI trends in Luxembourg mirror developments in international financial markets, which are being shaped by several factors. FDI is declining worldwide. Possible explanatory factors include changes in the international framework of the fight against the erosion of the tax base and profit transfers (Base Erosion and Profit Shifting initiative of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD). Another possible factor has been the large-scale repatriations of accumulated foreign earnings by United States multinational firms, after the tax reforms introduced in the country at the end of 2017. United Nations estimates by ultimate investors show that United States is by far the main source of inward FDI in Luxembourg, accounting for almost ¼ of Luxembourg total FDI liabilities (UNCTAD, 2019). Beyond these events, lower returns on FDI, a less favourable environment for investment and the underlying changing patterns in global trade and production, where international investment is increasingly driven by intangibles, which are growing faster than FDI, contribute the declining trend of FDI.

External position

Luxembourg’s net international investment position is volatile, due to its role as an international financial centre. The net international investment position reached 60% of GDP in 2018, against 52% of GDP at the end of 2017. Movements in asset prices and asset relocations, as well as inflows of international liquidity explain the volatility and the relative increase in gross assets and liabilities positions in previous years (see Section 3.2).

|

Graph 1.8:Current account, gross components - Luxembourg.

|

|

|

|

Source: Luxembourg

|

The current account balance reflects Luxembourg's economy features of output concentration, trade and financial integration and cross-border labour intensity. The current account balance has been posting comfortable and stable surpluses, of around 5% of GDP, for several years (Graph 1.8). The surplus in services (about 40% of GDP) is mainly related to private banking, the investment fund industry and corporate cash management entities. Most of these financial institutions are part of large international financial groups and multinational corporations, which mainly operate cross-border. The stable surplus is driven by strong net financial services exports, counterbalanced, to a large extent, by the outflows registered in the primary income balance. This reflects a threefold dependency defining Luxembourg's economy: high value added sector concentration, high external trade integration and high (foreign) labour intensity.

Real effective exchange rates have appreciated somewhat over the past years compared to their long-term trend. Real effective exchange rates based on the harmonised index of consumer prices and the unit labour costs index have appreciated by a moderate trend. The recent appreciation based on unit labour costs remains in line with developments in neighbouring countries, while real effective exchange rates based on the harmonised index of consumer prices have increased more strongly The current account "norm" (), as computed by the European Commission, suggests that Luxembourg’s external position has remained broadly consistent with fundamentals. A small positive current account gap relative to the norm mostly reflects the deviation of the favourable fiscal balance outcome in 2018 from its medium-term objective.

A large contribution to gross value added is made by foreign corporations and non-resident workers. This inflates the primary income deficit, which is the share of generated income flowing out of the country. In 2018, the balance of primary incomes with rest of the world amounted to (-) €22 billion, 36% of GDP. The primary income deficit has widened sharply since 2005, explaining the large gap between GDP and gross national income (Graph 1.9).

|

Graph 1.9:Difference between GDP and GNI (euro billion)

|

|

|

|

Source: Eurostat

|

Private debt

Non-financial corporations’ debt is one of the highest in the EU. At around 242% of GDP in 2018, it is expected to fall to 223% of GDP in 2019, of which more than 80% is foreign owned intragroup lending, although it remains well below pre-crisis levels. Within the current low interest rate environment, domestic banks have maintained their profitability mostly by increasing lending. Most of this expansion is linked to cross-border intercompany debt (Graph 1.10). A significant active deleveraging took place in 2017 and 2018, which was partly linked to holding companies' exceptional operations (SOciétés de PARticipations FInancières, SOPARFI. See capital markets above).

Mortgage debt has been increasing in line with rising house prices. A higher debt service burden, for a larger share of households, has built up compared with other EU Member States. However, regular internal stress tests suggest sound macro-prudential oversight and effective risk contention (see Section 3.2).

|

Graph 1.10:OUTSTANDING LOANS TO THE NON-FINANCIAL PRIVATE SECTOR (YoY %)

|

|

|

|

Source: Banque Centrale Luxermbourg

|

Housing

Soaring housing prices amplify inequalities, increase household indebtedness and may undermine Luxembourg's attractiveness. Housing prices have been growing strongly, with affordability deteriorating, in particular for low-income households. This can be explained by insufficient land availability, high population and employment growth, a large number of cross-border workers with challenging transport conditions (Section 3.5). There is a broad consensus that the shortage of affordable housing presents a structural challenge in the economy (Section 3.1).

Social developments

Poverty and inequality are increasing despite the positive impact of social transfers. In 2018, Luxembourg registered one of highest increases in income inequality in the EU, with the S80/S20 income quintile share ratio going up from 5.00 in 2017 to 5.72 in 2018 (). The overall risk of poverty or social exclusion has increased to 21.9 % in 2018, reaching the EU average. In-work poverty is still among highest in the EU. Although social transfers play a pivotal role in lifting people out of poverty, their impact has weakened further, against the rise of market income inequality. The newly implemented Revenu d’inclusion sociale, an activation benefit replacing the minimum guaranteed revenue as of 2019, which consists of an allowance for activities organised by the social inclusion office (such as community work or activities favouring social stabilisation), is expected to foster social inclusion (See section 3.3). The gross minimum wage has been raised in 2019 (in addition to regular indexation).

The impact of students’ origin and socioeconomic background on their performance is one of the strongest in the EU. The latest results of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) led by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (), show that in Luxembourg, the proportion of 15 year-old students with a low socio-economic background who underperform in reading is 37.5 percentage points greater than that of 15 year-old students with a high socio-economic background (see Section 3.3).

Public sector

The budgetary surplus is expected to shrink in the next years. From a surplus of 2.7% of GDP in 2018, to 2.3% of GDP in 2019, it is expected to drop further to 1.4% of GDP in both 2020 and 2021 (). The surplus in 2018 was again, to a large extent, the result of a large increase in revenues from current taxes on income and wealth. In particular, tax revenues from corporations increased for the third year in a row by more than 10% year-on-year. A moderate evolution of public expenditure also contributed to the improvement.

Revenues are projected to be less buoyant in the short-term forecasts. After overperforming for several years, revenues are expected to increase in line with GDP growth in the next few years. The introduction of the electronic tax declaration in 2017 accelerated the collection of revenues for corporations (). An increase in expenditure, in particular social outlays, will contribute to the fall in the surplus.

The level of public debt is low. It stood at 21% of GDP in 2018 and it is projected to fall even lower by 2021. A commitment to maintain the debt below the 30% of GDP threshold has been confirmed by the new government that took office at the end of 2018.

Concerns remain regarding the long-term sustainability of public finance. From now until 2070, Luxembourg is expected to face one of the sharpest increases among the EU countries in ageing-related expenditure (pensions, long-term care, and healthcare costs). With no policy change, there would be a large impact on public debt. Several measures have been adopted to address the sustainability of public pensions, but their impact has been limited (Section 3.1).

Overall, Luxembourg performs well in its progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). According to Eurostat’s SDGs indicators (see Annex E), Luxembourg has been making progress in a majority of the goals over the past 5 years. This is particularly the case, on average, for indicators on good health and wellbeing (SDG 3 – where Luxembourg registers a better performance than the EU average regarding most indicators), affordable and clean energy (SDG 7) and gender equality (SDG 5). There is a more mixed picture on indicators related to quality of education (SDG 4) and responsible consumption and production, in particular on waste generation and management (SDG 12). Some deterioration can be observed in indicators related to the reduction of inequalities within countries (SDG 10), the risk of poverty (SDG 1), or industry, innovation and infrastructure (SDG 9). The indicators related to the mitigation of climate change (SDG 13) are improving but remain below the EU average.

|

|

|

Table 1.1:Key economic and financial indicators

|

|

|

|

Source: Eurostat, ECB and European Commission

|

|

|

2.

Progress with country-specific recommendations

Since the start of the European Semester in 2011, 28% of all country-specific recommendations addressed to Luxembourg have recorded at least ‘some progress” (). Looking at the multi-annual assessment of the implementation of the country-specific recommendations (CSRs) since these were first adopted, 61% of all the country-specific recommendations addressed to Luxembourg have recorded 'limited' or 'no progress' (see Figure 2.1). Substantial progress and full implementation have been achieved in several areas of the fiscal policy, for instance preserving a sound fiscal position and strengthening fiscal governance.

|

Graph 2.1:Luxembourg - Level of implementation today of 2011-2019 CSRs

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|

Over the past years, Luxembourg has significantly strengthened its budgetary framework. In 2014, Luxembourg transposed in national legislation the requirements of the 2011 Council Directive on budgetary frameworks and the fiscal compact. In 2017, the authorities further adjusted the domestic regulation to bring it into full compliance with the 2011 Council Directive on budgetary frameworks. Since then, Luxembourg, which is under the preventive arm, has remained committed and compliant with the provisions of the Stability and Growth Pact. The implementation of the savings measures identified by the 2014 spending review is largely on track. The national authorities have implemented 80% of the measures identified in the review, most of them spending cuts integrated in the domestic budgetary planning. After overachieving savings target in 2015 (the first year of the multi-year budgetary strategy), the targeted savings for the 2016-2018 period were revised downwards by 25-35 %, partly linked to the reconsideration of a number of reform steps in vocational education and social transfers.

Several measures have been adopted to address the long-term sustainability of public pensions, though their impact has been limited. A pension reform was adopted in 2012, but its impact on pension expenditure has been limited. A law aiming at keeping workers with disabilities longer in the labour market entered into effect at the beginning of 2016. In 2017, some new measures have been put in place for older jobseekers (specific ALMPs since 2016, measures to fight long-term unemployment since 2017 and in the ADEM, specific mandatory information sessions about activation and training measures). Additionally, the 2017 tax reform introduced some incentives for increasing working time. A reform of the long-term care public insurance was enacted at the beginning of 2018, which keeps the evolution of long-term care costs in line with that of the share of dependent people in the total population, which is expected to ensure financial viability until 2030. Meanwhile, the expenditure projections reveal a heightened requirement for long-term care spending in the future. Additionally, the ‘pré-retraite de solidarité’, a special scheme allowing people to retire from the age of 57, was abrogated in 2018 but its impact might not be significant, as some restrictions on other kinds of early retirement were loosened. The employment rate of older workers went up by 7.5% in 2018 but it remains substantially below the EU average. More fundamental reforms have not been considered yet or are pending approval, such as the so-called 'Age Pact', which includes a whole package of measures to keep senior workers longer in employment. Finally, no measures have been taken on the recommendation for aligning the statutory retirement age to changes in life expectancy.

Some progress has been made on enhancing participation in the labour market, but challenges remain. The main efforts have focussed on reducing youth unemployment, where progress has been substantial. The recommendation on skills development has been recently addressed: the vocational education and training system had identified several fields for improvement. Students with lower socio-economic status are the most likely to fall behind in all subjects and to be oriented towards the technical tracks of secondary school. In response, the government recently took a number of measures to close the achievement gaps among pupils of different backgrounds and to reduce early school leaving. The law on vocational education and training, amended in 2016 and in application since 2016/2017, aims at improving the qualitative skill sets and study success rates of students. The employment of older workers remains among the lowest in the EU, particularly for the low-skilled, who are also particularly affected by long-term unemployment.

Luxembourg has made some progress in addressing bottlenecks that hamper housing investment. Numerous measures have been adopted or are planned, especially on the supply side, trying to increase the market offer. The "Fonds de Logement", a land management agency, was empowered by law to support the supply of housing. While significant investment appears necessary to alleviate tensions in the housing market, measures to stimulate housing supply are under preparation. These include more initiative planning regulations, development of affordable and social housing, land purchase by the government for social renting, stronger tax incentives and support to municipalities. Nevertheless, supply remains limited and the challenge ahead for Luxembourg’s authorities continues to be sizeable. House prices have continued rising in 2018 and in the first half of 2019.

Recently, Luxembourg has made some further progress towards the diversification of the economy. In response to somewhat weaker developments recently, two wide-scope strategies have been prepared to foster technological innovation and digital transformation in the broad business sector. Public investment remains high and measures to foster innovation have been integrated in the “Data-Driven Innovation Strategy for the Development of a Trusted and Sustainable Economy”, as well as a strategy on artificial intelligence. Their success will depend, to a large extent, on their capacity to activate private investment, especially on innovative technologies and digital integration. Business investment remains low compared with the euro area average, which weighs on Luxembourg’s innovation potential and might slow down the development of high-added value activities.

Luxembourg has made overall limited progress () in addressing the 2019 country-specific recommendations, although some progress was achieved on policies related to investment in a number of areas. In addition to limited progress on employment of older workers as outlined above, progress has been limited in removing regulatory restrictions in the business services sector. Several measures have been taken, although some regulatory restrictions remain above the EU weighted average in several regulated professional business services (according to available indicators). Luxembourg engaged in further reforming the professions of architect and engineer. No progress has been made by Luxembourg to improve the long-term sustainability of the pension system, including by further limiting early retirement. Limited progress was recorded on addressing aggressive tax planning – aside from implementing EU and internationally agreed initiatives, Luxembourg has not yet announced concrete reforms. However, Luxembourg reported that it has plans to address the issue of outbound payments with regard to jurisdictions included in the EU list of non-cooperative jurisdictions for tax purposes. Limited progress was made on economic policies related to investment increasing housing supply, including by increasing incentives and lifting barriers to build. By contrast, some progress was made on economic policies related to investment on improving sustainable transport. Significant investments have been realised and are to be continued to improve the transport system, and in particular public transport. Some progress was also made on economic policies related to investment on fostering digitalisation and innovation and on stimulating skills development.

|

|

|

Table 2.1:Overall assessment of progress with 2019 CSRs - Luxembourg

|

|

|

|

For CSR 3: The regulatory framework underpinning the programming of the 2021-2027 EU cohesion policy funds has not yet been adopted by the co-legislators, pending inter alia an agreement on the multiannual financial framework (MFF).

|

|

|

|

Box 2.1: EU Funds and Programmes to address structural challenges and to foster growth and competitiveness in Luxembourg

Luxembourg benefits from EU support. The financial allocation from the EU Cohesion policy funds (

I

) for Luxembourg amounts to €88.2 million in the current Multiannual Financial Framework. By the end of 2019, some €92.7 million (more than the total amount planned) was allocated to specific projects, while €41.4 million was reported as spent by the selected projects (

II

), showing a level of implementation well above the EU average.

EU Cohesion policy funding is contributing to transform Luxembourg’s economy by promoting growth and employment via investments. Policy areas include, among others, research, technological development and innovation, renewables and energy efficiency, employment and labour mobility. By 2019, investments driven by EU Funds have already led to 22 researchers working in improved Research and Development infrastructure facilities, 12 firms cooperating with research institutions and 2,161 households with improved energy consumption classification. By the end of 2018, the European Social Fund had supported 1,405 disadvantaged participants with a view to improving their social inclusion and 2,999 inactive young people in order to promote their sustainable vocational integration.

For instance, the European Regional Development Fund co-financed the Computational and Data Engineering Hub, which will be a springboard providing Luxembourg with a sustainable competitive advantage and will contribute to the training of the next generation researchers and industrialists in Computational and Data Science. The Interreg Energy Cells Greater Region project encompasses four energy cells in each Member State of the Grande Région forming a virtual power plant balancing renewable electricity production and consumption by using storage capacity within the cell or by exchanging excess power with other interconnected cells via smart grids. The European Social Fund supports many projects in the field of digital education, training and upskilling at various levels. For instance, Digit4All: to promote digital inclusion; Fit4DigitalFuture: for young jobseekers aged 18-30 having completed secondary education; Fit4CodingJobs: aiming at training 60 web developers within two years and; Formation e-Presse: training autistic people in the field of digital newspapers and social media.

Agricultural funds and other EU programmes also contribute to addressing the investment needs. The European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development allocates €368 million (including national co-financing). Luxembourg also benefits from other EU programmes, such as the Connecting Europe Facility, which allocated €29 million to specific projects on strategic transport networks, and Horizon 2020, which allocated EU funding of €125 million (including 39 small and medium-sized enterprises with about €24 million).

EU funds already invest on actions in line with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In Luxembourg European Structural and Investment Funds support 8 out of the 17 SDGs and up to 98% of the spending is contributing to those goals.

|

Upon request from a Member State, the Commission can provide tailor-made expertise via the Structural Reform Support Programme to help design and implement growth-enhancing reforms. Since 2018, such support has been provided to Luxembourg for three projects. In 2019, several projects have been progressing well. The Commission has provided, for example, the authorities with support in the area of digital economy. This involves developing a strategic

roadmap and a digital infrastructure map for 5G rollout and exchange of good practices, through the elaboration of an upskilling and awareness-raising plan. Likewise, a study has been launched to assess the feasibility of a reform of the budgetary accounting system at central government level. This study also aims at introducing international good practices for the transition to accrual accounting.

3.

Reform priorities

3.1.Public finances and taxation

3.1.1.Long Term Sustainability

Luxembourg is exposed to low fiscal sustainability risks on the short to medium term. The debt sustainability analysis, as well as the S0 and the S1 indicators (), in the Fiscal Sustainability Report 2019 (European Commission, 2020) point to low risks, due to the low public debt (19.6 % of GDP at end 2019) and the favourable initial budgetary position.

However, risk indicators point to high long-term fiscal sustainability risks. Ageing-related costs are expected to rise up until 2070, as highlighted by a high S2 () long-term fiscal sustainability gap indicator of 8.6 percentage points of GDP in 2019 (Debt Sustainability Monitor 2019, European Commission 2020), up from 8.1 percentage points in 2018. The projected rise of age-related expenditure is the main driver behind this indicator, in particular pensions (6.1 percentage points of GDP) and health care and long-term care expenditure (3 percentage points of GDP).

3.1.2.Pension, Healthcare and Long-term care

Despite a favourable position in the short to medium term, the pension system is expected to face rising challenges in the long term. Luxembourg's population ageing is slower than in neighbouring countries due to the continuous inflow of foreign workers (both immigrants and cross-border commuters). This supports pension contributions while only modestly raising the average workforce age, leading to pension system accumulated reserves of €19 billion in 2018. Long-term concerns are linked to expectations of rising age-related expenditure due to the evolution of the age pyramid. According to the government-appointed pension working group, the operational deficit of the general private sector pension scheme is projected to reach 7.6 % of GDP by 2070. Accumulated reserves are expected to ensure the viability of the system until 2041 (Rapport du groupe de travail pensions, 2018). The contribution rate is currently 24 % of the wage mass, with employers, employees and the state each contributing one third. However, based on the latest simulations, the contribution rate would need to increase to 37 % to prevent the reserve of the general pension scheme from falling below the legal threshold of 1.5 times the annual pension expenditure by 2070 (Rapport du groupe de travail pensions, 2018). The next evaluation of the general pension scheme is expected to be issued in 2022.

Projected increases in health care expenditure threaten the long-term sustainability of the system. Luxembourg’s per capita spending on health care remains the highest in the EU, as total per capita expenditure accounted for 172 % of the EU average in 2016. However, total expenditure on health accounted for 5.5 % of GDP in 2016, below the EU average (9.9 %). According to the Ageing Report 2018, public health expenditure in Luxembourg is projected to increase by 1.2 percentage points (Ageing Working Group Reference Scenario) by 2070. Although the Caisse Nationale de Santé (the national health insurer in Luxembourg) has accumulated financial reserves amounting to 27 % of its health insurance expenditure in 2017 (IGSS, 2019), the projected increase in spending poses a risk to future fiscal sustainability. The country’s relatively favourable composition in terms of population age is likely to change in the future. Luxembourg’s broad benefits package, with one of the lowest cost-sharing in the EU, as well as other features such as hospital overcapacity, with relatively low bed occupancy rates and high length of stay, and a relatively low share of generics, suggest efficiency-enhancing policies could help mitigate long-term risks.

Long-term care expenditure is projected to increase, posing fiscal sustainability risks. The "Ageing Working Group reference scenario" forecasts public expenditure on long-term care to grow from 1.3 % of GDP in 2016 to 4.1 % of GDP in 2070. This considerable increase is well above the EU average. The "Ageing Working Group risk scenario", which captures additional cost drivers to demographic and health-related factors, projects an even larger increase of 405 % by 2070. The 2017 long-term care reform mainly focused on improving quality of care, expanding the benefits package, investing in preventive services and setting clear standards, rather than addressing the long-term fiscal sustainability concerns ().

3.1.3.Fiscal Framework

The National Council of Public Finances issued a number of recommendations to improve fiscal forecasts. Luxembourg’s independent fiscal body, the new composition of which was approved in March 2019, suggested some improvements to the authorities’ fiscal forecasting processes. These notably included necessary improvements to the methodology used by the national statistical office (STATEC) to measure GDP and produce macroeconomic forecasts. The authorities answered to the evaluation formulated by the National Council of Public Finances, and among others highlighted that the macroeconomic scenario underlying the budgetary projections is under the responsibility of the STATEC, which is an independent body.

3.1.4.Taxation

Luxembourg’s tax burden was close to the EU average in 2018, but had a higher share of corporate income tax revenues and a lower share of consumption, property and environmental tax revenues. Total tax revenues amounted to 39.3 % of GDP in 2018, in line with the EU average (39.2 % of GDP). Corporate income tax revenues amounted to 5.8 % of GDP in 2018, which is among the highest in the EU. Corporate income tax revenues have increased in 2019, which is in part due to the introduction of the compulsory electronic tax return. Revenues from value added tax, property taxation and environmental taxation were all below the EU average. Around 43 % of tax revenues came from labour taxation, which is lower than the EU average (around 49%). However, disincentives to work for second earners are among the highest in the EU, which owes in part to taxation. Luxembourg is among the few countries where household-based taxation still applies, although there are plans to generalise individual taxation, which is currently optional. The exact conditions of the reform still need to be defined (Section 3.3.1).

While the statutory corporate income tax rate remains above the EU average, the tax burden effectively borne by a company is not only impacted by the rate, but also by tax incentives. The statutory corporate income tax (CIT) rate decreased in recent years, to 24.9 % in 2020 (17 % excluding surcharges), above the EU average of 21.7 %. The rate at which corporate income was, on average, effectively taxed amounted to 8.5 % in 2017 (European Commission (2019), Taxation Trends Report, implicit tax rate on corporate income). Corporations with taxable income below € 175.000 benefit from a 22.8 % statutory corporate income tax rate (15% excluding surcharges).

Recurrent taxes are low and based on outdated property values. Revenues from recurrent property taxes on immovable property were among the lowest in the EU in 2017. This owes mainly to the definition of the tax base, which is based on a scale that dates back to 1941 and is no longer aligned with current market values. This may impact on the price of housing and on housing supply, in particular regarding unoccupied property. Luxembourg is reflecting on ways to address the housing challenge, including through taxation (Section 3.2.3).

Transport fuel taxes rates are among the lowest in the EU, while these taxes remain the main source of environmental tax revenues in Luxembourg. While revenues from transport fuel taxes are well above the EU average (1.5 % in 2018 vs 1.3 % of GDP in the EU on average), tax rates on transport fuels for private use are relatively low. They are also lower than in neighbouring countries (), inducing cross-border fuel purchasing which enables the country to raise sizeable tax revenues despite low rates. Moreover, the level of tax on diesel remains low compared to the unleaded petrol duty, despite diesel having higher carbon content. Luxembourg increased in 2019 excise duty on petrol (+1 cent/litre) and diesel (+2 cents/litre).

The overall revenues from environmental taxes were the lowest in the EU in 2018. This is the case when considering environmental tax revenues as share of total tax revenues (4.4 % in Luxembourg and 6.1 % in the EU) and as a percentage of GDP (1.7 % in Luxembourg and 2.4 % in the EU). Luxembourg’s Government is reflecting on further changes of its environmental taxation to encourage a less polluting behaviour. According to the outline of the National Energy and Climate Plan () presented in December 2019 (Ministry of the Environment, Climate and Sustainable Development and Energy Department of the Ministry for Energy and Spatial Planning, 2019), Luxembourg would introduce a carbon tax of € 20 per tonne of CO2 from 2021, with incremental increases over the following two years. The tax could bring in an additional €150 million of revenue, half of which would be earmarked to support households in need, while the rest would be invested in measures aimed at advancing the “ecological transition” (Delano, 2019 / Gouvernement, 2019 ()).

Economic evidence suggests that Luxembourg's tax rules are used by companies that engage in aggressive tax planning. The rules identified as being of particular concern include the absence of withholding taxes on interest and royalty payments (Graph 3.1.1), and the possible exemption from withholding tax on dividends with treaty partners (). Due to the absence or possible exemption of withholding taxes, outbound payments of dividends, interest, and royalties from Luxembourg-based companies to non-EU jurisdictions could lead to little or no taxation if these payments are not taxed or taxed at a low level in the recipient jurisdiction. Inward and outward foreign direct investments are among the highest in the EU, with a majority linked to special purpose entities (). According to an International Monetary Fund working paper (J. Damgaard, T. Elkjaer and N. Johannesen (2019), What is Real and What is Not in the Global FDI Network?), Luxembourg is the biggest recipient of foreign direct investment held by special purpose entities, worldwide. The level of capital flows (dividends, interest, but also royalties) is also among the highest in the EU, and at a high level compared to the size of the economy (see European Commission (forthcoming), Tax policy survey in the European Union 2019). Luxembourg is a small open economy, with a large financial sector, which partly explains those financial flows. However, they also reflect the large presence of foreign-controlled companies in the country, which undertake intra-group financing or treasury operations (IMF (2018), Article IV Consultation).

|

Graph 3.1.1:Outgoing interest payments in the EU and share going to offshore financial centres.

Average 2013-2017, (€ billion)

|

|

|

|

Source: Eurostat

|

Luxembourg is implementing European and internationally agreed initiatives to curb aggressive tax planning. Further to the transposition of the Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive ("ATAD1") Luxembourg adopted the transposition of the Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive as regards hybrid mismatches ("ATAD 2") on 19 December 2019. On 1 August 2019, the Multilateral Convention to Implement Tax Treaty Related Measures to Prevent Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (‘Multilateral Instrument’) entered into force in respect of Luxembourg. Luxembourg has chosen to apply this instrument to all its Treaty partners. Currently, 21 Treaties have been affected by the Multilateral Instrument, given that both Luxembourg and its Treaty partners need to have joined the convention, ratified the Multilateral Instrument and included each other in the list of covered tax agreements. Luxembourg has put a reservation on numerous articles of the Multilateral Instrument not forming part of the minimum standards. The country plans to rely on bilateral negotiations to amend its double tax treaties and bring them in line with the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting principles (). Luxembourg codified the advance tax ruling procedure in 2014, including that rulings cannot have a period of validity longer than five tax years. Therefore, all advance tax rulings granted before 2015 are automatically invalidated as of the end of fiscal year 2019 (pursuant to Article 5 of the 2020 Budget). Beyond implementing EU and internationally agreed initiatives, Luxembourg has not yet announced concrete reforms to address aggressive tax planning, in particular by means of outbound payments (since the publication of the 2019 country report). However, Luxembourg reported that it has plans to address the issue of outbound payments with regard to jurisdictions included in the EU list of non-cooperative jurisdictions for tax purposes. No specific information has been provided allowing to assess the effect of these measures in limiting the scope for aggressive tax planning, in particular by means of outbound payments, and their impact on the corporate income tax revenue in the medium term. These effects remain to be assessed.

3.2.

Financial sector

3.2.1.Financial sector

Luxembourg is one of the world’s largest financial centres. After the United States, Luxembourg is the second biggest fund administration centre worldwide with € 4.5 trillion of assets under management (Graph 3.2.1). Banks channel funds through Luxembourg, which is reflected in high external assets (€ 450 billion or 7.3 times GDP in 2018), mirrored by high external liabilities (€ 422 billion or 6.9 times GDP in 2018). However, comparing these aggregates to national GDP is of limited explanatory power, given the country’s size and financial interconnectedness.

|

Graph 3.2.1:Five main open-end funds jurisdictions, Q2 2019 (% of world total net assets)

|

|

|

|

Source: International Association of Investment Funds

|

Luxembourg’s financial centre mostly caters to the need of international clients. While the country hosts the largest financial sector in Europe relative to the size of the local economy, in absolute terms it is smaller than London or Switzerland’s financial centres. The financial sector in Luxembourg accounts for a quarter of GDP and 11.5 % of employment directly. The country counts 130 banks in July 2019, of which 7 banks are domestically-oriented commercial banks. Foreign financial institutions mostly come from Europe. Banks established in Luxembourg can be clustered into retail banks, custodian banks, and private wealth banks, corporate finance banks, clearing and settlement and payment institutions. Whereas custodian and private wealth banks’ main income source are fees and commissions, retail and corporate finance banks focus on interest income.

Employment in the financial sector remains dynamic. The number of bank employees remains broadly stable around 26,500, although banks increasingly tend to outsource back-office functions to less costly jurisdictions. Employment in the overall financial sector has been growing from 45,500 in June 2016 to some 50,500 in June 2019 (Graph 3.2.2). Job creation has mostly taken place in management companies administering funds, and in auxiliary professions of the financial sector, such as audit companies. Staff counts in the four largest audit companies nearly trebled since 2007.

|

Graph 3.2.2:Persons employed in the financial sector

|

|

|

|

Source: Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier

|

Banking sector

Luxembourg’s banks continue to display strong capital ratios. The consolidated common equity tier 1 ratio () of 19.2 % in the second quarter of 2019 was 420 and 440 basis points above the EU and euro area averages, respectively. This is largely due to the low average risk profile of Luxembourg’s banks, such as custodian banks, which do not grant retail loans, and for which market risk and operational risk outweigh credit risk. This leads to lower risk-weighted assets compared to other European jurisdictions where retail credit risk predominates. Luxembourg’s non-performing loans ratio is among the lowest in the EU at 0.7 % of gross loans as of Q2 2019, compared to 2.5 % and 3.0 % in the EU and euro area, respectively. However, the large amount of intra-group loans inflates the denominator in Luxembourg. Very low default rates over the last decade have influenced banks’ internal risk models. Like in other Member States, once Basel III reforms are fully implemented, they will lead to significantly higher capital requirements (European Banking Authority (2019) ()).

|

Graph 3.2.3:Luxembourg banks - Aggregate profits and losses

|

|

|

|

Source: Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier

|

|

|

|

Table 3.2.1:Key Financial Performance indicators

|

|

|

|

Source: European Central Bank

|

|

|

The low interest rate environment and rising operational costs weigh on banks’ profitability. The return on equity declined slightly over the past five years in Luxembourg, whereas it rose on average in the euro area. Banking income fell by 2.0 % between June 2018 and June 2019, mainly due to the drop in interest margin income, while commission fees continued to increase. Intermediation income accounts for less than 45 % of banking income. For comparison, the latter amounts to 73 % in neighbouring Germany. This divergence reflects the relatively lower share of traditional retail banking in Luxembourg and high share of custodians and private wealth banks, with their main income source being fees and commissions. They rely mainly on fees charged for specialised or custodial services provided to clients. Overall, the intermediation margin remained broadly constant as deposit and loan rates hardly moved during the past three years. The cost-to-income ratio rose to 62.3 % in June 2019 compared to 58.3 % in June 2018, as operating costs soared by 8.1 % over this period. This was driven broadly equally by staff and non‑staff operating costs, among others due to wage increases, the need for regulatory adaptations and investments in digitalisation.

Luxembourg has introduced some macro-prudential buffers to prevent excessive risk-taking. For banks using the internal ratings based approach the risk weight for residential mortgage loans is floored at 15 %. In addition, the counter-cyclical capital buffer was also activated and set at 0.25 % of risk-weighted assets as of January 2020 and will increase to 0.5 % of risk-weighted assets as of January 2021 () (). Like in other jurisdictions, Luxembourg’s supervisor annually reviews the buffers for other systemically important institutions. From January 2020, a capital buffer of 0.5 % for other systematically important financial institution will be applied to seven banks, while an eighth bank’s other systematically important financial institution buffer will be set at 1 % of risk-weighted assets.

Investment funds

Luxembourg accounts for a quarter of European investment funds net assets. Net assets in Luxembourg’s funds have increased by 12.4 % in the first nine months of 2019, to about € 4.57 trillion (Graph 3.2.4). Most of the increase (86 %) was due to positive valuation effects. Luxembourg’s funds account for 26.8 % of money under management in Europe. The number of funds has remained quite stable around 4,000 since 2014. Two thirds of them are multiple compartment funds and the number of fund units is also relatively stable around 14,000 since 2014.

|

Graph 3.2.4:Net assets under management, € trillion

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|

Liquidity stress in the fund sector seems contained due to the low-risk profile of most funds. 94 % of funds are invested in highly-liquid, standard financial assets, while less liquid categories make up the remaining 6 %, which generated concerns regarding some funds’ potential liquidity stress under very severe market conditions (CSSF January 2020 newsletter, p. 7 ()). However, the financial crisis of 2008/2009 showed that fund managers can adopt conservative strategies in stress episodes, selling securities and increasing their cash holdings. In addition, the supervisory authorities have increased their monitoring of liquidity risk and dedicate more attention to funds invested in less liquid asset classes.

Luxembourg’s institutions keep up with financial innovation, including green finance. The country’s position as the world’s second largest fund administration centre is supported by the high degree of specialisation of its financial sector. Luxembourg counts on a variety of banks concentrating only on custodian activities, a large supply of professionals covering the full array of fund administration functions, and one of Europe’s two central securities depositories. Luxembourg’s track record of fast transposition of EU directives has given it a first-mover advantage and a legal environment that keeps up with financial innovation. For instance, Luxembourg hosts the lion share of Europe’s environmental sustainability funds, as its stock exchange was the first to launch a green bond in 2007 and in 2016 it established a dedicated section which lists half of the world’s green bonds (see also sections 3.2.5 and 3.5).

Insurance

The Luxembourg insurance sector continues to grow, and is expected to be supported by the relocation of some UK-based insurance companies. The balance sheet of the insurance sector amounted to € 241 billion () in 2018 (roughly 4 times GDP), making it one of the largest in Europe in relative terms. 76 % of total assets stem from life insurance, 18 % stem from re-insurance, and 6 % is non-life insurance business. Gross premiums were € 24 billion for life insurance, up by a 2.5 % vis-à-vis 2017, re-insurance premiums fell 2.5 % to € 10 billion, and non-life increased 22.3 % to € 5 billion. Profitability has declined in 2018 compared to 2017 (see table 3.2.2), notably due to the low interest rates environment. So far 11 non-life insurance and one life insurance companies have decided to relocate their EU-focussed business units from the UK to Luxembourg. Establishing their base in the country allows them to branch out into the remaining EU member states, but they also benefit from facilities such as the possibility to communicate officially in English with the insurance supervisor. Luxembourg is one of the few member states with a separate body exercising insurance supervision.

Luxembourg remains a competitive destination for intra-group reinsurance captives (). The Grand Duchy counts 197 reinsurers, which profits amounted to € 273 million in 2018, a lower level compared to previous years, notably due to the volatile results in some large re-insurance companies and the closure of some small undertakings. The re-insurance industry in Luxembourg has a relatively large size and maintains a healthy profitability. This underlines the attractiveness of domiciling intra-group re-insurance captives in Luxembourg, inter alia for tax purposes. Only 19 % of reinsurers’ staff is actually based in Luxembourg. Aggregate employment in the insurance sector grew from 6,607 in 2014 to 8,582 in 2018 but only half of them work in Luxembourg, as many companies use the country as a platform to branch out into the euro area.

|

|

|

Table 3.2.2:Key Insurance Figures

|

|

|

|

Source: Commissariat aux Assurances

|

|

|

3.2.2.Private sector indebtedness