EUROPEAN COMMISSION

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Brussels, 18.7.2017

SWD(2017) 264 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

Accompanying the document

COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS

Strengthening Innovation in Europe's Regions: Towards resilient, inclusive and sustainable growth at territorial level

{COM(2017) 376 final}

Commission staff working document

Table of Contents

1

Introduction

2

Smart Specialisation – regional partnerships for innovation, growth and jobs

2.1

The need for smart specialisation

2.1.1

Boosting investment in research and innovation

2.1.2

The diversity of performance of regional innovation systems across Europe

2.1.3

The position of the European institutions

2.1.4

Public consultation on smart specialisation

2.2

The RIS3 approach

2.2.1

The history of smart specialisation

2.2.2

A place-based policy approach

2.2.3

Addressing weaknesses in the delivery of regional innovation policy

2.3

Putting in place the right conditions for effective investments

2.3.1

RIS3 as an ex-ante conditionality

2.3.2

Incentives for reform through ex-ante conditionalities

2.3.3

RIS3 conditionality has helped address institutional weaknesses in innovation systems.

2.3.4

Changes induced by the RIS3 ex-ante conditionality

2.4

Early implementation and expected results

2.4.1

Expected results

2.4.2

Investment share in Research and Innovation (R&I)

2.4.3

Thematic priorities of regions – Eye@RIS3

2.4.4

Selection of operations and expenditure declared in ESI Funds

2.4.5

Evidence on implementation through analysis of calls for projects

2.4.6

The establishment of the S3Platform

2.4.7

Influence on national and regional systems

2.4.8

Overall assessment of achievements

3

Key challenges and next steps: boosting innovation-led growth

3.1

Further reform of research and innovation systems

3.1.1

The contribution of research and innovation to EU economy and productivity growth

3.1.2

The need for reform

3.1.3

Higher education and VET in smart specialisation

3.2

Increasing cooperation in innovation investment across regions

3.2.1

Rationale for transnational, interregional, cross-border cooperation

3.2.2

Addressing fragmentation and creating innovation investments in value chains

3.2.3

RIS3 in European Territorial Cooperation

3.2.4

Macro-regional strategies

3.2.5

European-level support for smart specialisation investment across borders

3.2.6

Thematic Smart Specialisation Platforms

3.2.7

RIS3 and the link to Digital Innovation Hubs and other innovation infrastructures

3.2.8

Maturity of mechanisms to support investment in innovation across borders:

3.3

Leveraging research and innovation in less developed and industrial transition regions

3.3.1

Tailoring through RIS3 leads to address specific bottlenecks in less developed regions

3.3.2

Mutual learning on design and implementation

3.4

Harnessing synergies and complementarities between EU policies and instruments

3.4.1

Mechanisms for synergies

3.4.2

Progress on synergies

3.4.3

Initiatives to promote synergies

1Introduction

Europe is experiencing a momentous period of change. Globalisation, automation, decarbonisation, emerging and digital technologies: all have an impact on jobs, industrial sectors, business models, the economy and the society as a whole. It is indispensable to help Europeans adapt to these profound changes and to help the EU economy to become more resilient. In its Reflection Paper on Harnessing Globalisation, the Commission highlighted the opportunities and challenges that Europe's citizens and regions are facing. This means anticipating and managing the modernisation of existing economic and societal structures bearing in mind that today, more than ever local issues have gone global and global issues have become local. To this end, Europe needs a long-term strategy, involving action at all levels, which triggers a fundamental shift in technology, economics and finance.

The future challenge for EU regions is to be able to compete at the global level with other most advanced and emerging economic powers as they are more than ever part of a globalised world. Therefore, they need to find ways to become more resilient and competitive by taking concrete actions at EU, national and local levels while ensuring that the benefits of globalisation are shared.

Many European regions are well positioned to take advantage of the opportunities offered by globalisation. However, the Commission's reflection paper on globalisation

stressed that the competitiveness and innovation divide between some advanced EU regions and less strong regions is widening. Vulnerable regions can still be found across Europe in Southern or Central and Eastern Europe. Identify the potential of these regions and focusing on reinforcing their local strengths, narrowing development gaps, and boosting competitiveness can help strengthen resilience to globalisation. Special attention should also be paid to the resilience of rural areas, which are at risk of being left behind by globalisation and demographic change.

Innovation clusters that link up companies, universities, start-ups, investors and local governments must be further developed and linked up across Europe. The EU and their regions should invest more in the emerging industries and workers of the future, focusing on new and advanced manufacturing technologies and related industrial services to drive innovation. EU regions should position themselves in global value chains and help their businesses move up along the value-chain and further exploit their comparative advantages.

In order to do so, regions should further strengthen links between stakeholders and infrastructures across different European countries to exploit synergies. Interregional cooperation can play an essential role in this direction. Sharing costs between companies within value chains and sectors in an open innovation community would allow the development of new processes and provide the means to succeed in a comprehensive way. This would permit many industries, and in particular their SMEs, to develop processes that they would not be able to develop on their own because of a lack of resources.

In order to boost Europe’s competitiveness, it will also be necessary to find additional private investment across all sectors, provide better access to finance (especially for SMEs and start-ups that develop most of the innovations) and increase access to foreign markets towards boosting EU exports. Openness to foreign investment is also key for the EU and a major source of growth – as is to provide investment-friendly regulatory and business framework conditions as well as develop critical infrastructure (including for digitalisation, energy and transport).

Globalisation is a shared task between the EU and its Member States and regions. The table below – from the European Commission’s reflection paper on harnessing globalisation – shows how each level can contribute to make this process successful.

Graph 1: Contribution of each level of governance to harnessing globalisation

In conclusion, it is difficult to predict what globalisation will look like in ten years' time as technologies and their uses are changing rapidly. However, by strengthening cooperation between different levels of government, Europe can help its regions to move up global value chains, stimulate the private sector and target investment on key priorities and challenges, while preventing brain drain and rural flight.

This requires a concerted effort at EU, national and regional level to broaden the base for innovation, better target private and public resources and increase synergies. This entails not only better links within the Single Market and the European Research Area but also new opportunities for businesses to build on regional strengths to develop and grow within global value chains and markets and in this way to seize the opportunities created by globalisation.

In 2010 the Commission called on national and regional governments to develop smart specialisation strategies (RIS3) for research and innovation (R&I) to encourage all European regions to discover their competitive advantage. This new "smart specialisation" approach became the basis for research and innovation investment under the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) for the programming period 2014-2020. The Council of the EU and the European Parliament have highlighted the need to further build on this approach.

The purpose of this staff working document is to provide a first overview of the evidence and draw lessons on R&I strategies for Smart Specialisation (RIS3) and their contribution to more efficient and effective national and R&I systems that support competitiveness and cohesion as well as broader research and industrial policy objectives, in the context of globalisation.

The document presents the smart specialisation approach and how it evolved from a theoretical concept to tool for the implementation of national and regional innovation policy in all European Union regions irrespective of their economic development level, innovation performance, governance structure, research capabilities or business environment. It also examines how the prerequisites (ex-ante conditionalities) necessary for smart specialisation have been applied.

The staff working document assesses the current state of play as regards the design and implementation of smart specialisation strategies in the EU. It also shows how the smart specialisation approach is being applied in other parts of the world such as Australia and Latin America.

Finally, it examines the contribution of smart specialisation to the reform of European R&I systems and how, by adopting a tailored approach it has helped to build capacity in Europe's regions and facilitate investment across regions. It provides a state of play on the complementarities and synergies between EU instruments.

2Smart Specialisation – regional partnerships for innovation, growth and jobs

2.1The need for smart specialisation

Innovation is recognised as one of the main economic drivers for boosting jobs, growth and investment in the White Paper on the Future of Europe and is essential for achieving the political priorities of the Juncker Commission. Innovation is a precondition for "sustainable and job-creating growth". It leads to higher productivity and competitiveness while offering social and environmental benefits.

2.1.1Boosting investment in research and innovation

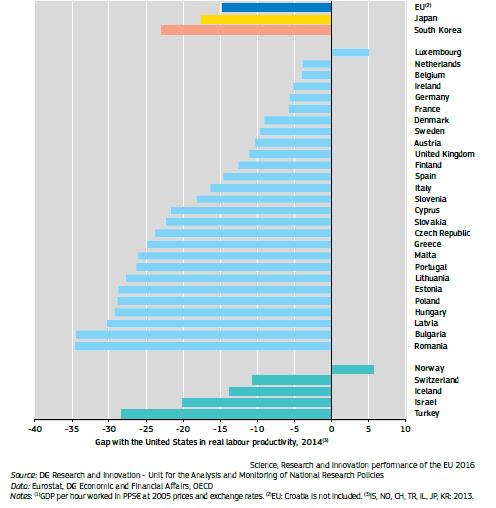

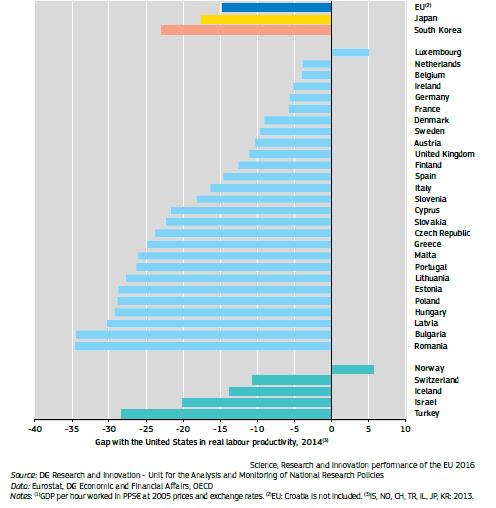

Despite the fact that the target for Member States to invest 3% of their GDP on R&I is one of the priorities of Europe 2020 strategy

, the aggregate share of R&I investments within the EU is still lower than in countries such the USA, Japan and South Korea. Within the EU, gross domestic expenditure on R&D as a percentage of GDP varies considerably from country to country with Sweden, Austria and Denmark spending a high percentage of their GDP on R&D and Eastern and Southern European countries lagging behind with lower expenditure.

Graph 2: Gross domestic expenditure on R&D as % of GDP

Source: Eurostat 2017

South Korea and Japan have an increasing performance lead over the EU. In particular their relative strength is in business R&D expenditures, innovation collaboration and procurement. The top R&D spending enterprises invest twice as much on R&D as top EU enterprises. Australia, Canada and the United States have a decreasing performance lead over the EU. However, Brazil, China, India, Russia and South Africa are catching up. In particular China increased its R&D expenditure and the number of Trademark and Design applications.

Graph 3: Global performance (bars show countries' performance in 2016 relative to that of the EU in 2010)

While the EU hosts a high number of high level PhDs, their research is weakly connected to the market. Their employment is almost equally shared between the public and private sector, whereas in competitor-countries the percentage of researchers employed within the private sector is higher.

Graph 4: Researchers share in the business and public sectors in third countries compared to the EU.

Source: Science, Research and Innovation Performance of the EU 2016

2.1.2The diversity of performance of regional innovation systems across Europe

Well performing innovation systems are found in Member States and regions which are better developed and are more competitive. There is a close correlation between R&D performance ("Regional Innovation Scoreboard") and economic performance ("EU Regional Competitiveness Index"). Without research and regional policies working closely together to encourage knowledge absorption, lagging regions and countries may never be able to converge to the technology frontier.

Graph 5: EU regions performance in terms of innovation and competitiveness

Source: EU Regional Competitiveness Index, 2016 and Regional Innovation Scoreboard Report, 2017

More than half of the total potential for productivity growth in developed countries comes from "catching up" innovation. Given the different level of economic development in which EU innovation actors operate, European policies need to take account of the differing situations in Member States and regions and, in particular, should target the needs of both developed and less developed economies. Cohesion Policy therefore takes account of the specific needs of less developed Member States and the need to support broad based innovation. This is in line with the recommendations of the 2017 Annual Growth Survey, which highlights the need to improve the interaction between research and business and to encourage reforms of weak research and innovation systems in Member States.

As conditions differ from region to region, innovation needs to be embedded in local business knowledge that is often concentrated in clusters of related industries, but linked to high quality research across Europe to enable the swift diffusion and application of the knowledge created. By bringing together a broad range of businesses, researchers and public actors as part of a prioritisation and experimentation process and connecting them with new research ideas, smart specialisation can build on Europe's diversity of regional and local strengths.

The process of designing and implementing smart specialisation strategies ensures that public resources are targeted at areas which are likely to bring the best returns in terms of raising the level of innovation in all parts of Europe. This is achieved by addressing weaknesses in innovation systems and reinforcing the institutional capacity to bring research to market and trigger an uptake of innovation, notably in less-developed Member States.

2.1.3The position of the European institutions

The European Parliament expressed its support for smart specialisation in its resolution of 8 September 2016, and proposed to the European Commission and to Member States to implement further actions in order to make smart specialisation become more effective. It also noted in its Resolution of 6 July 2016 that synergies for innovation between Structural Funds and Horizon 2020 and other policies and instruments must be further enhanced in order to maximise the impact of investments. It further called for continued efforts to boost inter-regional collaboration and recalled the importance of innovation systems, institutions and the linkages to local and regional clusters in its report of 27 April 2016 on Cohesion Policy and smart specialisation strategies.

The Council, in its conclusions of 24 June 2016, called for "a more R&I friendly, smart and simple Cohesion Policy and the European Structural and Investment Funds more generally", and recognised that "smart specialisation strategies could be powerful instruments for contributing to tackling societal challenges, and boosting innovation, investment and competitiveness, based on socio-economic and territorial specificities". It called on the European Commission "to give continued support to Member States and regions when developing and implementing smart specialisation strategies". The Council Conclusions of 4 December 2014 on the industrial competitiveness agenda had also already recommended smart specialisation as an approach to prioritising investments and reiterated the importance of clusters and partnerships and the Presidency report of 16 November 2015 on mainstreaming competitiveness also acknowledged the contribution of clustering and smart specialisation strategies.

In addition, the European Commission has launched many initiatives at EU level which identify smart specialisation as relevant for structural reforms and for various policies such as energy, digital, industrial policies and for the circular economy.

2.1.4Results of the public consultation on smart specialisation

The importance of smart specialisation strategies is also highlighted by the replies of 237 respondents to the public consultation launched by the Commission in December 2016. 73 % of the respondents think it is ‘most and very important to implement European strategic priorities in focus areas in regions’, 70 % think it is ‘most and very important to have a bottom-up agenda for European growth & jobs’, 68 % think it is ‘most and very important that all types of regions can participate (advanced, research intensive regions and lagging regions)’ as well as alignment between complementary efforts in different countries and regions (64%).

The three most important objectives of RIS3 according to the respondents are:

·creating jobs and growth through place-based R&I investments (84%),

·enabling businesses and researchers to develop investment projects together (72%)

·the economic transformation of the region (e.g. towards new sectors) (68%).

The vast majority (94 %) of respondents to the public consultation think that it is important ‘to a great extent’ (74 %) or ‘to some extent’ (20 %) to put in place RIS3 strategies with priorities about which businesses, academia and public stakeholders have been consulted before funding is allocated.

Supporters and implementers of innovation alike observed a significant increase in the participation of clusters or business associations (75% and 66% respectively) and higher education institutions (68% and 76%) in the innovation ecosystem

In terms of the first early impact of smart specialisation strategies on the research and innovation infrastructure or support services, the greatest improvements in the support offered was observed for networking and cooperation (62% for finding partners within the country and 54% for partners abroad), for industrial research activities (55%) and experimental development/prototyping (49%) and for better access to researchers (53%) and R&I infrastructures and R& I service providers (55%). Important improvements have also been observed for technology transfer (47%) and digitization of enterprises and processes (42%) whereas no overall improvements were observed for the regulatory framework.

2.2The RIS3 approach

2.2.1The history of smart specialisation

Smart specialisation (RIS3) is an innovation policy approach that aims to boost national and regional innovation, contributing to growth and prosperity by helping and enabling Member States and regions to focus on their strengths. RIS3 brings together the research community, business, higher education, public authorities and civil society. These partners identify strengths in their region, and prioritise support based on where local potential and market opportunities lie (the "Entrepreneurial Discovery Process" - EDP). To help with this process, RIS3 seeks to improve governance at regional and national level, concentrate resources, build critical mass, and accelerate the uptake of new ideas.

The smart specialisation strategy concept was developed by the European Commission's high-level expert group "Knowledge for Growth" in 2005-2009, closely related to the concept of clusters, and was originally designed to tackle two main issues:

·The fragmentation of public research systems unable to compete independently on a global scale;

·The duplication of research work which leads to a scattering of resources across the European Research Area.

During the reform of cohesion policy for the period 2014-2020, the concept was extended in order to encourage regional economic transformation. It was also incorporated into EU regional policy as a key principle of investment in R&I.

In its 2010 Communication "Regional Policy Contributing to Smart Growth in Europe 2020", the Commission called on national and regional governments to develop smart specialisation strategies (RIS3). Following its inclusion in the regulatory framework for Cohesion Policy 2014-2020 through the introduction of specific ex-ante conditionality, this new approach became the basis for research and innovation investment under the European Regional Development Fund.

Smart Specialisation strategies are defined in point (3) of Article 2 of the Regulation (EU) No 1303/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council:

"Smart Specialisation Strategy (S3)" means the national or regional innovation strategies which set priorities in order to build competitive advantage by developing and matching research and innovation own strengths to business needs in order to address emerging opportunities and market developments in a coherent manner, while avoiding duplication and fragmentation of efforts; a smart specialisation strategy may take the form of, or be included in, a national or regional research and innovation (R&I) strategic policy framework."

2.2.2A place-based policy approach

Innovation still depends very much on location. Smart specialisation has been implemented in high-performing, middle income, and less-developed Member States or regions., Conceived within the reformed EU Cohesion Policy, smart specialisation is a place-based policy promoting investment in innovative activities in selected areas to achieve a smart, inclusive and sustainable growth in line with the EU's Europe 2020 growth strategy. Using local knowledge and learning reflects the overall justification for using a local and regional place-based development policy approach to cohesion policy, rather than employing a space-neutral or purely sectorial approach.

The smart specialisation approach therefore identifies strategic areas for intervention, based both on the analysis of the strengths and potential of the regional economies and on a process of entrepreneurial discovery with wide stakeholder involvement. It embraces a broad view of innovation that goes beyond research-oriented and technology-based activities, and requires a sound intervention strategy supported by effective monitoring mechanisms.

Lessons learned from targeted RIS3 support in EU Member States and their regions

In Poland, for instance, the Slaskie Region initiated its first innovation strategy for 2003-2013 on which it could rely, whereas Wielkopolskie, which never had strong specialisation, needed to start the entrepreneurial discovery process leading to the regional smart specialisation strategy, through comprehensive research and analysis of the existing conditions.

Latvia where smart specialisation was a new concept started with a comprehensive research on the sectors of the economy, related research capacity, business composition and advantages of the Member State. In close cooperation among the public sector, academia and business priority areas were chosen and further developed though a continuous entrepreneurial discovery process combined with structural reforms of the research institutions and higher education institutions as well as by reviewing the tax regime for innovative companies.

In Denmark and Sweden, with highly developed innovation and business structures, the process approach was to detect systematically the inter-linkages and opportunities of the existing regional and national innovation and development strategies rather than to identify e.g. specific sectors as object for public intervention to promote smart specialisation.

Finland, as a leader in innovation, continues the smart specialisation approach in open, inclusive and participative method building on the existing advantages. An excellent example is Oulu Innovation Alliance that was created when the city faced a serious structural change caused by big ICT companies moving out of the city and thousands of jobs were lost. The aim of the alliance was to develop a Northern innovation ecosystem through cooperation between public sector, research and educational sector and companies that integrates top expertise and resources from selected fields. This approach helped Oulu to create 2000 new jobs, establish 300 new start-ups in the knowledge-intensive growth sectors, and develop new ICT sub-sectors that made the ICT sector in the region more flexible, agile and resilient to possible structural changes.

Each region, no matter the type or level of its socio-economic endowment, can in this way find its own way to sustainable and inclusive growth taking into consideration EU strategic goals. For example, a carbon intensive region could focus on transforming experience and technology in traditional activities into greener economic activities that require similar competences and which are set to grow in the future in the context of EU policy priorities.

2.2.3Addressing weaknesses in the delivery of regional innovation policy

If properly designed through an interactive bottom-up process involving most of the innovation actors on a territory, smart specialisation can help address weaknesses in the delivery of innovation policy in Europe. These include the following:

Weaknesses in the delivery of regional innovation policy:

·Lack of prioritisation and poor resource allocation - The Entrepreneurial Discovery Process (EDP) is perhaps the most distinctive feature of the smart specialisation approach. Such a mechanism makes it possible: (i) to identify precisely (at the level of a single activity or system of activities) the market failures affecting the local economy and (ii) direct policy intervention exclusively towards those targets . This is opposed to the previous situation (pre-RIS3), where it was not possible for public authorities to identify specific market failures and needs of the local economic system – meaning that the only option was to use horizontal measures (acting across activities, but with no differentiation between them.

·Weak microeconomic governance in the EU Member States and regions – evidence based policy and investment decision making which is informed by tacit knowledge of innovation actors is often not available in the public domain.

·Barriers to the uptake of new ideas – inflexible governance mechanisms hamper the process of bringing new products and services into market.

·Mismatch of EU research strengths and business needs – the failure to exploit the wealth of knowledge existing in the EU to increase the competitiveness of EU businesses and accelerate the uptake of solutions to tackle societal challenges.

·Lack of strategic alignment of investment pipelines in industry and research, in both the private and public sector. This leads to scattered, fragmented and duplicated investments.

·Lack of information flows across business sectors, scientific disciplines and EU territories – increasing the degree of information asymmetry.

·Lack of interregional cooperation between innovation actors across EU – failing to exploit the EU single market's potential to improve collaboration between innovation actors in related activities.

·Weaknesses in EU value chains – opportunities for demonstration projects and for scaling up of initiatives are missed due to lack of economies of scale and scope.

·Low leverage effect of EU funding – a failure to attract private investors to realistic and bankable innovation initiatives.

By addressing these issues in the delivery of support for innovation under the European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF), smart specialisation can contribute to boosting overall growth and jobs, and help respond to globalisation. At a more specific regional level, smart specialisation can – by improving the prospects of specific regions and Member States for growth and economic transformation – also reduce disparities between the levels of development in the various regions and help the less-developed or lagging regions to progress.

It will also contribute to building specialisation in the Single Market as a whole, broadening innovation and contributing to industrial competitiveness goals. This applies to both well-established sectors such as agri-food, tourism, textile and those at the global technology frontiers in energy, environment, nano-tech, and health. Public administrations can use their purchasing power to play an important complementary role by encouraging transformative technological change and the uptake of innovation through their purchasing power.

Such activities offer regions the opportunity to diversify and develop new industrial activities by capitalising on emerging and key enabling technologies (KETs), digital transformation, service innovation, resource-efficient solutions and other breakthrough innovations that cover all and new forms such as open and user-led, public sector, frugal and social innovation. In addition, the bio-economy and the transition to a circular economy offer great potential for growth.

2.3Putting in place the right conditions for effective investments

2.3.1RIS3 as an ex-ante conditionality

A key element of the RIS3 approach in during the 2014-2020 programming period was the requirement to define a national or regional RIS3 strategy for R&I before being allocated ERDF funding. This ex-ante conditionality was added to the regulatory framework to ensure that the effectiveness of EU investments within the regions was not undermined by the absence of evidence-based innovation priorities and the lack of appropriate institutional framework for R&I.

Two thematic ex-ante conditionalities (ExAC) were introduced in the area of research and innovation:

R&I: requiring a national or regional smart specialisation strategy that (ExAC 1.1)

·is based on a SWOT or similar analysis to concentrate resources on a limited set of research and innovation priorities (ExAC 1.1.1);

·outlines measures to stimulate private research, technology and development (RTD) investment (ExAC 1.1.2);

·contains a monitoring and review system (ExAC 1.1.3);

·ensures that a Member State has adopted a framework outlining available budgetary resources for research and innovation (ExAC 1.1.4);

R&I infrastructure: requiring a multi-annual plan for budgeting and prioritisation of investments (ExAC 1.2)

The RIS3 ex-ante conditionality applied to most national or regional operational programmes (169 out of 205) and in all 28 Partnership Agreements. It was the most frequently applied ex-ante conditionality at regional level. At the time the programmes were adopted, only 20% of the programmes were considered as fulfilling ex-ante conditionality. 20 member states were required to develop action plans to fulfil this conditionality.

The following causes have been identified by the European Commission as responsible for a difficult fulfilment of ex-ante conditionality in the area of RIS3:

·A lack of political commitment to long-term strategies, and difficulties devising a bottom-up process of smart specialisation as a way to prioritise investments;

·The split of responsibilities between different vertical (national, regional, municipal) and horizontal (between ministers and departments) levels, resulting in the fragmentation of powers and failed coordination;

·A lack of effective, competent and adequately skilled staff in administration exacerbated by frequent legislative and institutional changes;

·Weak collaboration between the public and private sector and thus little commercialisation of public research;

·An absence of continuity in the entrepreneurial discovery process and a lack of key milestones, roadmaps, monitoring mechanism;

·Tenuous links between financed projects and RIS3 priority areas.

It is likely that all programmes will have fulfilled their ex-ante conditionalities by the reporting deadline of June 2017. The introduction of the RIS3 ex-ante conditionality has therefore demonstrated the significant potential for the improvement of the governance of national and regional innovation systems in many Member States.

2.3.2Incentives for reform through ex-ante conditionalities

Ex-ante conditionalities (ExAC) have been important in terms of triggering reforms. They accounted for about 85% of the reform-triggering ExAC in in Member States that have joined the EU since 2004.

Graph 6- Overview of reform triggering Thematic Ex-ante conditionalities

|

|

1.1

|

1.2

|

2.1

|

2.2

|

3.1

|

4.1

|

4.2

|

4.3

|

5.1

|

6.1

|

6.2

|

7.1

|

7.2

|

7.3

|

7.4

|

8.1

|

8.2

|

8.3

|

8.4

|

8.5

|

8.6

|

9.1

|

9.2

|

9.3

|

10.1

|

10.2

|

10.3

|

10.4

|

11.1

|

|

Total

|

|

AT

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

0

|

|

BE

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

0

|

|

BG

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

|

9

|

|

CY

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

|

12

|

|

CZ

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

19

|

|

DE

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

0

|

|

DK

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

0

|

|

EE

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

4

|

|

EL

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

|

20

|

|

ES

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

2

|

|

FI

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

0

|

|

FR

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

0

|

|

HR

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

19

|

|

HU

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

|

16

|

|

IE

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

0

|

|

IT

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

4

|

|

LT

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

|

11

|

|

LU

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

0

|

|

LV

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

|

11

|

|

MT

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

|

4

|

|

NL

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

1

|

|

PL

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

12

|

|

PT

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

|

1

|

|

RO

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

23

|

|

SE

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

0

|

|

SK

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

x

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

11

|

|

SI

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

X

|

X

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

X

|

|

11

|

|

UK

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

0

|

|

Total

|

13

|

7

|

10

|

8

|

4

|

6

|

0

|

1

|

7

|

9

|

8

|

9

|

7

|

6

|

3

|

6

|

3

|

5

|

3

|

3

|

2

|

11

|

8

|

11

|

6

|

8

|

8

|

8

|

10

|

|

190

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Key to table:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0

|

No reform triggering effect found

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X

|

Reform triggering effect found

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Study "Support of ESI Funds to the implementation of the Country Specific Recommendations and to structural reforms in Member States"

ExAC 1.1 (research and innovation) was characterised by a strong reform impact and high coherence with the European Semester (CSR/structural challenges). Evidence shows that the RIS3 ex-ante conditionality triggered reforms in all 13 Member States which joined the EU in 2004 or later and two belonging to the EU15 – IT and GR.

All these Member States had Member State specific recommendations in the European Semester process in the Member State Reports in the field of research and innovation in 2012-2015. In the majority of the Member States, the recommendations on research and innovation persisted for the whole period.

The occurrence of reform-triggering ExACs was substantially higher in the major (per capita) beneficiary Member States of the ESI Funds, which are also countries whose level of economic development is below 75% of the EU average.

In many cases, this conditionality helped to break down silos in multi-agent and multi-level governance and led to new dynamics in setting priorities and targets and creating the relevant policy instruments to achieve them. This mechanism, where public administrations listen directly to actors as part of a structured dialogue gives direct and unbiased feedback on existing or potential bottlenecks in national/regional R&I systems and skills and education needs.

2.3.3RIS3 conditionality has helped address institutional weaknesses in innovation systems.

The effectiveness of the EU investments under cohesion policy depends on the institutional capacities in the Member States through which these investments are channelled to the final beneficiaries.The organisation of the public sector and the institutional relationship and cultural norms governing the relationship between innovation actors is essential for economic performance. Characteristics such as trust, information sharing, common goal setting and mechanisms such as partnerships, clusters, stakeholder involvement and transparency and anti-corruption initiatives provide the basis for sustained economic cooperation.

In this respect, the RIS3 ex-ante conditionality has helped in many regions to set an agenda for modern research and innovation institutions that can prioritise investments in research and innovation, in particular through its impact of the ex-ante conditionality is on the governance and on the behaviour of the stakeholders in the innovation systems while setting-up the RIS3.

The 6th Cohesion Report (European Commission 2014a) summarises several channels through which poor governance limits the impact of cohesion policy on economic growth. In the first place, it can reduce expenditure if programmes fail to invest all the funding available. Secondly, it can lead to a less coherent or appropriate strategy for a country or region. Thirdly, it may lead to lower quality projects being selected for funding or to the best projects not applying for support at all. Fourthly, it may result in a lower leverage effect because the private sector is less willing to co-finance investment.

In 2013 Rodriguez Pose and Garcilazo (2013) used econometric tools to examine the impact of both the quality of government (measured by the European Quality of Government index) and EU Cohesion Policy expenditures on regional growth in the European Union in the period between 1996 and 2007. They found that above a certain level of Cohesion Policy transfers, the quality of local government becomes a vital factor in determining the extent to which EU funds affect economic growth: the higher the quality of government, the greater the impact. In the regions with poor quality of government, greater level of cohesion expenditure can only lead to a marginal improvement of economic growth, unless the quality of government is significantly improved.

There is evidence that the capacity of a regional government in promoting public policies and minimising corruption is relevant for the effectiveness of strategies aimed at improving innovation. Regions with poor institutions can achieve significant gains in terms of innovative performance as a result of relatively small improvements in the quality of their governance systems. Good institutions, therefore, seem to be a significant pre-condition for the development of the innovative potential of regions and for making innovation strategies such as RIS3 work, especially in the periphery of Europe.

2.3.4 Changes induced by the RIS3 ex-ante conditionality

The ex-ante conditionality aims at improving performance of the innovation systems concerned through a partnership process requires behavioural changes of all partners and stakeholders involved. According to early evidence based on survey data,

the ex-ante conditionality on smart specialisation triggered the introduction of significant adaptations in the stakeholder involvement process (more than 60% of respondents).

Changes in the behaviour of administrations were achieved without imposing a unique model to be followed by all regions and Member States with substantial scope left for adaptation to local specificities. This resulted in clear differences in the way smart specialisation elements are articulated and implemented on the ground, revealing differences in the starting point of regions and Member States facing a new approach to innovation.

The majority of regions acknowledge that RIS3 has had a positive impact on their innovation policy governance, with better planning and impact orientation and more inter-departmental cooperation (e.g. among the research, education and industry ministries).

As a result of the action plans a number of Member States needed to make changes to fulfil the preconditions (for example, the need to involve national and regional bodies). There was a clear difference between Member States with an already established structured strategy and Member States with a weaker strategic framework. Many Member States or regions with a strong tradition in innovation adapted existing strategies. In contrast, EU13 Member States developed their regional (e.g. Poland) and national strategies according to the guidelines of the European Commission. This suggests that the introduction of the RIS3 ex-ante conditionality has significant potential for the improvement of the governance of national and regional innovation systems in many Member States.

2.4Early implementation and expected results

2.4.1Expected results

During the negotiations on their programmes, EU Member States and regions have developed over 120 RIS3 strategies establishing priorities for research and innovation investments in the programming period 2014-20. Throughout this period an amount of more than EUR 40 billion (and more than EUR 65 billion including national co-financing) will be allocated to regions through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF). Overall, support to research, innovation and entrepreneurship is expected to help 15 000 enterprises to introduce new products to market, to support 140 000 start-ups and to create 350 000 new jobs by the end of the programme period

. In addition, around EUR 2.5 billion is focussed on clusters and business networks and EUR 1.8 billion have been programmed under the European Social Fund (ESF) for strengthening human capital in research, technological development and innovation.

Foreseen outputs for ERDF investment in Research and Innovation

Number of new researchers in supported entities:

29,372 full time equivalents

Number of researchers working in improved research infrastructure facilities:

71,960 full time equivalents

Number of enterprises cooperating with research institutions:

71,252 enterprises

Private investment matching public support in innovation or R&D projects:

9,985,491,257 EUR.

Number of enterprises supported to introduce new to the market products:

15,385 enterprises

Number of enterprises supported to introduce new to the firm products:

26,938 enterprises

Number of enterprises participating in cross-border, transnational or interregional research projects:

5,177 enterprises

Number of research institutions participating in cross-border,

transnational or interregional research projects:

1,117 research institutions

The long-term impact of implementation of smart specialisation strategies in terms of increased innovation, job creation and improved productivity will require a number of years and will be examined as part of the ongoing and ex-post evaluation of Cohesion Policy programmes.

2.4.2Investment share in Research and Innovation (R&I)

The largest investments in research and innovation (R&I) in absolute terms are planned in Eastern and Southern Europe (ERDF, ESF), notably under the thematic objective (TO1) research and innovation. On average, 10.6% of ESIF are committed to R&I. As a share of total investments, planned investments in R&I are higher in Northern Europe.

Under TO1 the five largest planned investment categories are research and innovation processes in SMEs (including voucher schemes, process, design, service and social innovation) EUR 6.7 billion; Research and innovation infrastructure (public) EUR 6 billion; Technology transfer and university-enterprise cooperation primarily benefiting SMEs EUR 4.4 billion; Research and innovation activities in public research centres and centres of competence including networking EUR 4.2 billion and Research and innovation processes in large enterprises EUR 2.5 billion.

The Member States with the largest planned investments in absolute terms are Poland EUR 7.5 billion, followed by Spain 4.7 billion, Germany 3.8 billion, Italy 3.5 billion, Czech Republic 2.4 billion and Portugal 2.3 billion. The Member States with highest share of investment planned for TO1 are the Netherlands, with 32.1%, followed by Denmark (23.2%), Luxembourg (20.8%), Germany (20.6%) and Austria (19.8%).

Graph 7: Planned investments under TO1

Source: ESIF-viewer, visualising data for ERDF, ESF, CF and YEI,

http://RIS3platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu/esif-viewer

2.4.3Thematic priorities of regions – Eye@RIS3

In RIS3 strategy documents, most regions and Member States have identified different combinations of broadly defined priorities. The RIS3 definition process identified a range of thematic priority areas for investments – e.g. health, climate, energy and industrial modernisation driven by key enabling technologies, transport, mobility, creative economy, bio-economyand much more. The identified areas have been found at the intersection of economic sectors, expected to develop faster, thanks to their novelty, diversity and innovation, as well as new marketing and organizational solutions. This could nonetheless also involve revamping traditional sectors by mixing them with new economic areas or focusing on their particular elements from a new viewpoint based on a specific advantage.

Examples of RIS3 priority-setting processes

In Poland, the RIS3 finding process resulted in 20 national and 81 regional smart specializations, encompassing both traditional sectors (such as tourism, furniture or agriculture) and more innovative technologies and industrial processes (such as multifunctional materials, including nanoprocesses and nanoproducts).

In Denmark, some sectors appeared in several regions' identified areas of strength and opportunities (health e.g.), whereas other sectors appeared more region specific (e.g. blue economy). This identification process has enabled the Danish regions to adopt a more systematic approach to the entrepreneurial discovery process.

In the UK the smart specialization strategies depend on the unique circumstances of the different “Member States” (England, Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales). Innovation policies are developed at national level in partnership with businesses and research institutions across the Member State, whereas other elements of smart specialisation can only best be delivered at the local level, such as strengthening of local innovation ‘ecosystem(s)’ and building local capabilities, supporting local supply chains to invest and collaborate, catalysing and leveraging the differing opportunities of social innovation; and branding and positioning places as credible centres of smart specialisation.

Ireland's smart specialisation strategy provides indicative multi-annual plans for budgeting and prioritisation of investments linked to R&D, identifying 14 strategic areas where public investment in research should be concentrated. These strategic areas encompass the priorities both at national level and at regional level. A “mapping” exercise of the existing strengths evidenced regional specializations such as Medical Technology concentration in the West of Ireland, or Marine Renewable Energy in the West and North West.

Estonia has chosen surface coating technologies and nanotechnologies in new materials as one of the domains of the smart specialisation. For instance, a company, Skeleton Technologies, used an ERDF grant to develop a high-performing and competitive ultra-capacitor technology

. Combined with support under Horizon2020 and later financing by the European Investment Bank, the company became Europe's leading producer of ultra-capacitors.

Graph 8: Ten most common categories of priorities

Source: Eye@RIS3 database,

http://RIS3platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu/map

The Eye@RIS3 tool of the Smart Specialisation Platform provides detailed maps of regions according to thematic priorities, as illustrated below for energy.

Graph 9: Example Eye@RIS3 map of regions with energy related priority areas

Source: Eye@RIS3 database,

http://RIS3platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu/map

2.4.4Selection of operations and expenditure declared in ESI Funds

The European Regional Development Fund is the most important source of support for smart specialisation strategies in most regions.

By January 2017, the progress of implementation on the ground was picking up speed. The end-January indicator of project selection has reached 26% on average for all the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) projects. When examining the thematic objectives (TO) that correspond to the eligible costs of projects selected, supports for smart specialisation (TO1 – EUR 16 billion) and for SMEs (TO3 – almost EUR 20 billion) are the most advanced fields approaching 40% of ERDF allocation.

Under TO1 – strengthening research and innovation: about one fifth of the EUR 16 billion eligible costs fall under the category of research and innovation processes in SMEs (cat.064). Together with technology transfer (cat. 062), activities in public research centres (cat.060), public infrastructure (cat.058), and processes in large enterprises (cat.002) about 75% of the overall eligible costs are covered. The eligible costs in selected projects are relatively evenly distributed across these four categories (in a range of EUR 1.9 billion to EUR 2.6 billion).

Under TO3 – enhancing support for SMEs: generic productive investment in SMEs (cat. 001) makes up almost half of the EUR 20 billion eligible cost in selected projects. Adding SME business development support (cat.064) and advanced support services to SMEs (cat.066) results in coverage of 80% of the expenditure of selected projects.

2.4.5Evidence on implementation through analysis of calls for projects

An ongoing study by European Commission (JRC) analysing the calls for projects launched under the ERDF Thematic Objective 1 “Strengthening research, technological development and innovation” in 2014-2016 in five Member States (Poland, Italy, Portugal, Hungary, Lithuania and Slovenia) reveals that the smart specialisation (RIS3) approach is being translated into practice and is playing a pivotal role in the implementation of ERDF innovation-linked measures within national and regional Operational Programmes.

In most of the examined calls, RIS3 alignment is a binding eligibility condition for R&I funding.

ERDF Operational Programs – Thematic Objective 1 (Research and Innovation): Number of RIS3-related calls (31 December 2016)

|

Member State

|

Published calls (end-2016)

|

RIS3-related calls (eligibility condition)

|

|

|

Number

|

Number

|

% of total calls

|

|

Italy

|

66

|

61

|

92

|

|

Poland

|

109

|

105

|

96

|

|

Portugal

|

54

|

54

|

100

|

|

Hungary

|

11

|

7

|

64

|

|

Lithuania

|

10

|

10

|

100

|

|

Slovenia

|

7

|

7

|

100

|

|

TOTAL

|

257

|

244

|

95

|

Source: Adaptation from Gianelle, C., F. Guzzo, and K. Mieszkowski (2017), Smart Specialisation at work: Analysis of the calls launched under ERDF Operational Programmes, JRC Technical Report, forthcoming.

Nearly all ERDF resources made available through the calls support project proposals falling exclusively within RIS3 priority areas.

ERDF - Thematic Objective 1 (Research and Innovation): Funding allocated through RIS3-related calls (31 December 2016)

|

Member State

|

ERDF resources

|

Overall ERDF funding for TO1 in each MS (2014-2020)

|

RIS3 related calls: % of TO1 resources

|

|

|

Total published calls (EUR)

|

RIS3-related calls (EUR)

|

% of RIS3 related calls

|

|

|

|

Italy

|

767,830,874

|

741,203,316

|

96.5

|

3,512,735,843

|

21.1

|

|

Poland

|

3,860,052,103

|

3,846,348,571

|

99.6

|

8,351,428,665

|

46.1

|

|

Portugal

|

1,253,320,000

|

1,253,320,000

|

100

|

2,328,812,052

|

53.8

|

|

Hungary

|

1,194,255,484

|

1,073,610,323

|

89.9

|

2,148,860,450

|

50.0

|

|

Lithuania

|

244,536,487

|

244,536,487

|

100

|

678,878,835

|

36.0

|

|

Slovenia

|

75,232,627

|

75,232,627

|

100

|

461,739,158

|

16.3

|

|

TOTAL

|

7,395,227,575

|

7,234,251,324

|

97.8

|

17,482,455,003

|

41.4

|

Source: Gianelle, C., F. Guzzo, and K. Mieszkowski (2017), Smart Specialisation at work: Analysis of the calls launched under ERDF Operational Programmes, JRC Technical Report, forthcoming.

The study also shows the existence of "spill-overs" of smart specialisation into other policy areas, in particular SMEs competitiveness, access and use of ICT, shift towards a low-carbon economy, and education and training. There exist calls embracing different policy instruments which support integrated project proposals falling within RIS3 priorities areas. The study shows that the most common category of beneficiaries is consortia of enterprises and research organisations. Together with three other categories - single (large, small and medium sized) enterprises - consortia of enterprises, and consortia of SMEs, they are generally the beneficiaries of calls aiming to support R&I projects.

2.4.6The establishment of the S3Platform

One of the main achievements of the smart specialisation approach has been the establishment of a community of practice for design and implementation of smart specialisation strategies. To assist Member States and regions in the process of developing, implementing and reviewing their smart specialisation strategies, the Commission set up the Smart Specialisation Platform (S3 Platform) in 2011. Its objective has been to provide information, methodologies, expertise and advice to national and regional authorities as well as to promote mutual learning and trans-national cooperation. It has around 200 members in total including 18 EU Member States and two non-EU countries, as well 170 EU and nine non-EU regions.

The S3 platform has developed a number of tools to encourage and support stakeholder interaction in RIS3, such as online matchmaking tools, peer review exchanges and learning workshops, giving interested parties a solid basis on which to interact with each other. It is clear, however, that an insufficient level of development of innovation environment is hampering the participation of some Member States and regions, especially from the EU-13, and limiting cooperation with more developed regions from the “old” Member States.

Smart specialisation cooperation actively involves a wide variety of stakeholders — national and regional authorities, universities, research institutions, business and civil society — and therefore brings significant opportunities to exploit synergies, facilitate the transfer of knowledge and capabilities and develop new ideas. A transnational perspective enables Member States and regions to evaluate their competitive position with regard to others, obtain the necessary research capacity or overcome a lack of critical mass.

Graph 10: Registered Member States and regions in the RIS3 Platform

Source: RIS3 Platform, available at

http://RIS3platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu/RIS3-platform-registered-regions

2.4.7Influence on national and regional systems

There is a range of evidence which shows how smart specialisation strategies have influenced national and regional innovation systems.

2.4.7.1Governance and institutional changes

New practices in public administrations have emerged at national, regional and local level with regard to innovation policy-making. The RIS3 approach has brought about significant structural and institutional changes in regional governance, triggering or strengthening inter alia, interdepartmental cooperation, participative and inclusive governance, more transparent and efficient monitoring mechanism.

|

Examples of how RIS3 has triggered structural change in some EU Member States:

In the Czech Republic, the national authorities have given regions the opportunity to determine their own priorities by exploring their R&I strengths and weaknesses, growth potential and engaging with regional stakeholders. This should lead to the better allocation of financial resources. Although regions still do not hold formal legal responsibilities in R&I, they have designed their RIS3 strategies and manage them under the ESIF-funded Smart Accelerator project, depending on the readiness of regions.

In Slovenia Strategic Research and Innovation Partnerships (SRIPs), established during the RIS3 design phase, play a key role in transforming the governance structure. SRIPs are clusters that bring together companies, knowledge institutions, civil society organisations and notably, different government services. RIS3 initiated an unprecedented pooling of public and especially private research, technology, development and innovation capabilities in key priority areas. This is accompanied by comprehensive and well-coordinated government support addressing all relevant competitiveness dimensions and simultaneously emphasising forward-looking and disruptive types of innovation through the integration of science, engineering, design and art.

In Sicily (Italy), innovators have pointed out that most ideas have often failed to get off the ground because they did not pass funding eligibility thresholds. The regional authorities recognised the need for a different governance model. A new cross-departmental structure now coordinates the analysis, planning, guidance, and monitoring of RIS3. This is complemented by permanent thematic groupings that include international partners.

In Lapland, systemic RIS3 thinking has emerged (rather than a new governance structure): RIS3 implementation is followed up horizontally throughout all the layers of the planning and decision-making process in regional development.

In East Macedonia and Thrace (Greece), the entrepreneurial discovery process (EDP) required not only the introduction of participatory dialogue into research, technology, development and innovation policymaking, but also renewed efforts to build trust in the public sector. This transfer of ‘entrepreneurial· knowledge’ into policy intervention required that stakeholders who took part in the EDP were kept informed about policy outcome through:

•EDP focus groups: a set of four sector-based events, aimed at generating innovative ideas through interaction between business, the public sector and research organisations within the RIS 3 priorities;

•Project Development Labs (PDL): a set of two events aimed at processing EDP ideas and moving them towards implementation, identifying funding opportunities and action plans for policy. During the second PDL in particular, policymakers presented to ‘Triple Helix’ actors the draft calls for proposals, which had been developed during the EDP focus groups. Stakeholders were able to comment on those and develop their own ideas further with the support of experts in R&D funds.

With the RIS3 experience, policymakers in this region were given responsibilities for R&I policies. These new powers pushed the managing authority of the ERDF operational programme to develop, together with the Joint Research Centre (JRC), skills in participatory leadership to pursue EDP in different sectors.

Through the EDP focus groups, the region set out in detail its priority areas and, building on this, analysed the administrative and legal aspects necessary to write effective calls for proposals. This involved interactions with the national government, the European Commission and experts in the field. Furthermore, throughout this process, stakeholders themselves noted that a better awareness of relevant actors (through updated databases and appropriate avenues for interaction) was necessary for conducting a proper EDP.

|

In the public consultation 92% of respondents replied that they think they should be more involved in the design and/or implementation of S3 challenging existing innovation governance structures. The respondents have been asked also which other organisation should be in their opinion more/better involved in the design or implementation of R&I support in their country / region. Most respondents see a need to involve enterprises (55% for medium-sized enterprises, 46%, for large and 43% for small and micro-enterprises) more in the implementation or research and innovation support. More involvement of SME intermediaries such as cluster organisations and Higher Education Institutions (43% each) is also seen as important.