EUROPEAN COMMISSION

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Strasbourg, 8.3.2022

SWD(2022) 62 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT

Accompanying the document

PROPOSAL FOR A DIRECTIVE OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL

on combating violence against women and domestic violence

{COM(2022) 105 final} - {SEC(2022) 150 final} - {SWD(2022) 60 final} - {SWD(2022) 61 final} - {SWD(2022) 63 final}

Contents

1.

Introduction: Political and legal context

2.

Problem definition

2.1.

What are the problems?

2.1.1

Scope

2.1.2 Problem description

2.1.3.

Who is affected?

2.1.4.

Why is violence against women and domestic violence a problem?

2.2.

What are the drivers?

2.2.1

Structural gender inequality and gender stereotypes

2.2.2.

Failure to recognise the specificities of crimes and offences relating to violence against women and domestic violence

2.3.

How will the problem evolve?

3.

Why should the EU act?

3.1.

Legal basis

3.2.

Subsidiarity: Necessity of EU action

3.3.

Subsidiarity: Added value of EU action

4.

Objectives: What is to be achieved?

4.1.

General objectives

4.2.

Specific objectives

5.

What are the available policy options?

5.1.

What is the baseline from which options are assessed?

5.1.1.

Dynamic baseline: EU level measures

5.1.2

Dynamic baseline: Member States measures

5.2.

Options discarded at an early stage

5.3.

Description of the policy options

6.

What are the impacts of the policy options?

6.1.

Fundamental rights

6.2.

Social impacts

6.3.

Economic impact

6.3.1

Estimated benefits: reduction of costs of violence

6.3.2

Administrative and compliance costs for Member States and employers

6.3.3

Summary of costs and economic benefits

7.

How do the options compare?

7.1.

Effectiveness

7.2.

Efficiency

7.3.

Coherence

7.4.

Preferred option

8.

How will actual impacts be monitored and evaluated?

Glossary

|

Term or acronym

|

Meaning or definition

|

|

Asylum-seeking women and girls

|

A woman or a girl who has left her country of origin to seek international protection.

|

|

Child

|

Any person below 18 years of age.

|

|

Coercive control

|

Oppressive conduct that is typically characterised by tactics to intimidate, degrade, isolate and control the victim. Can be combined with physical abuse and sexual coercion.

|

|

Domestic violence

|

All acts of physical, sexual, psychological or economic violence that occur within the family or domestic unit, or between former or current spouses or partners, regardless of whether the perpetrator shares or has shared the same residence with the victim. Domestic violence can target anyone in the family unit and covers for instance women, men, children, older people and same-sex partners.

|

|

Female genital mutilation (FGM)

|

Procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.

|

|

Forced abortion

|

Intentional termination of a pregnancy without the prior and informed consent of the victim (woman or girl).

|

|

Gender

|

Socially constructed roles, behaviours, activities and attributes that a given society considers appropriate for women, men, girls and boys. This includes the relationship among and between these socially constructed norms, behaviours and roles.

|

|

Gender bias

|

Prejudiced actions or thoughts based on the perception that women are not equal to men in rights and dignity.

|

|

Gender stereotype

|

A generalised view about attributes or characteristics, or the roles that should be performed by women and men in a given society. A gender stereotype is harmful when it limits individuals’ capacities to develop personal abilities, pursue careers or make other life choices.

|

|

Gender-sensitive policies

|

Policies that take into account the particularities pertaining to the lives of women and men, in all their diversity, while aiming to eliminate inequalities and promote gender equality, including an equal distribution of resources, thus taking into account the gender dimension.

|

|

General support services

|

Help offered through for instance social services, health services and employment services. General support services provide short and long-term help and are not exclusively designed for victims of violence against women or domestic violence, but serve the public at large.

|

|

Secondary victimisation

|

When the victim suffers further harm due to the manner in which institutions and individuals approach the victim. Secondary victimisation may be caused, for instance, by repeated exposure of the victim to the perpetrator, repeated interrogation about the same facts or the use of inappropriate or insensitive language by those who come into contact with the victim.

|

|

Sexual harassment

|

Any form of unwanted verbal, non-verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature, with the purpose or effect of violating the dignity of a person, in particular when creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment.

|

|

So-called “honour crimes” against women and girls

|

Acts of violence that are disproportionately, though not exclusively, committed against girls and women, because family members consider that certain suspected, perceived or actual behaviours bring dishonour to the family or community.

|

|

Specialist support services

|

Support services targeted to victims of violence against women and domestic violence. Specialist support services can include social, emotional, psychological and financial support, as well as practical and legal support.

|

|

Trafficking in human beings

|

A crime which consists of the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or reception of persons. Control over the victim is attained through the threat of force or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability, or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person. The purpose is the exploitation of the trafficked person. Exploitation includes, as a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation.

|

|

Victim

|

A natural person who has suffered harm, including physical, mental or emotional harm or economic loss, as a result of violence against women or domestic violence, including child witnesses of such violence.

|

|

Violence against women

|

All acts of violence that are directed against a woman because she is a woman or that affect women disproportionately, which result or are likely to result in physical, sexual, psychological or economic harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life.

|

|

Women

|

Women and girls under the age of 18, in all their diversity.

|

|

Term or acronym

|

Meaning or definition

|

|

CEDAW

|

Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women

|

|

CFR

|

Charter of Fundamental Rights

|

|

CJEU

|

Court of Justice of the European Union

|

|

DSA

|

Digital Services Act

|

|

DV

|

Domestic violence

|

|

ECHR

|

European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms

|

|

ECtHR

|

European Court of Human Rights

|

|

EIGE

|

European Institute for Gender equality

|

|

EPRS

|

European Parliamentary Research Service

|

|

FGM

|

Female genital mutilation

|

|

FRA

|

Fundamental Rights Agency of the European Union

|

|

GREVIO

|

Council of Europe’s Group of Experts on Action against Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence

|

|

Istanbul Convention

|

Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence

|

|

TEU

|

Treaty on European Union

|

|

TFEU

|

Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

|

|

UNCRPD

|

United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

|

|

VaW

|

Violence against women

|

|

VRD

|

Victims’ Rights Directive

|

|

WHO

|

World Health Organization

|

1.1.

Introduction: Political and legal context

Violence against women and domestic violence are widespread across the European Union and worldwide. When taking office, Commission President von der Leyen announced that the EU should do all it can to prevent violence against women and domestic violence, protect victims and punish offenders.

The EU Gender Equality Strategy 2020-2025

announces key actions for preventing and combatting violence against women and domestic violence in Europe and, in particular, a legislative proposal tackling such violence. The need to tackle violence against women and domestic violence also figures prominently in the EU Strategy on the Rights of the Child (2021-2024)

, the EU Strategy on Victims’ Rights (2020-2025)

, the LGBTIQ Equality Strategy 2020-2025, and the Strategy for the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2021-2030. The Gender Action Plan III

makes the fight against gender-based violence one of the priorities of the Union’s external action. Gender equality is also the second principle of the European Pillar of Social Rights, which aims to ensure and foster equality of treatment and opportunities between women and men in all areas.

At international level, measures to counter violence against women and domestic violence have been called for since the 1990s, including in the framework of the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (‘CEDAW’). The Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence (‘Istanbul Convention’) is the first instrument in Europe to set binding standards on the matter. While all Member States have signed the Convention, to date, 21 Member States have become parties to it. This means that the remaining six Member States are not bound by the Convention’s standards.

The Commission proposed in 2016 the EU’s accession to the Convention

, but this proposal has not yet been adopted by the Council and the accession negotiations have been blocked for several years. The EU’s accession is opposed by the six Member States that have not ratified the Convention due to a political backlash against it, which is partly caused by misunderstandings of certain provisions and exacerbated by disinformation campaigns. On 6 October 2021, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) issued its opinion on the EU accession to the Istanbul Convention. The CJEU clarified that the EU can accede to the Convention even if not all Member States have ratified it, but grants the Council discretion to wait with a vote until consensus has been reached. It is therefore not possible to predict when the EU’s accession to the Istanbul Convention might take place, and how many Member States would eventually ratify the Convention. While finalisation of the EU’s accession to the Convention remains a key priority for the Commission, the measures of the present initiative are aimed at achieving the objectives of the Convention within the areas of EU competence until such accession has taken place. Once the EU accedes to the Convention, this initiative will implement its provisions within such areas.

This initiative builds on the Istanbul Convention and the Commission’s continued commitment to finalising the EU’s accession. To reach the objectives of the Istanbul Convention in the areas of EU competence, this initiative aims to fill in the gaps identified in the EU acquis in the areas covered by the Convention. It aims at setting up minimum standards concerning the rights of this group of crime victims, binding on the Member States and enforceable by the Commission. This initiative also takes into account recent developments such as the digital transformation and lessons learnt from the COVID-19 pandemic.

The European Parliament has repeatedly called on the Commission to propose legislation on violence against women and domestic violence.

In January 2021, it underlined the need for measures to address the disparities in laws and policies between Member States and called for an EU framework directive on the matter.

The Parliament has adopted two own-initiative reports, on adding gender-based violence as a new Euro-crime and on combatting gender–based cyber violence.

2.2.

Problem definition

2.1.

What are the problems?

2.1.1Scope

This initiative covers violence against women, and domestic violence against any person. This corresponds to the scope of the Istanbul Convention. Violence against women and domestic violence are commonly addressed together both in the Member States and at international level. This is due to their common features, as explained in detail under section 2.1.2 below.

The key concepts used in this Impact Assessment follow established international definitions, which have been incorporated in the 21 Member States’ national laws, in order to ensure consistency once the EU accession to the Istanbul Convention takes place. Violence against women hence covers all acts of gender-based violence resulting in, or likely to result in, or threatening physical, sexual, psychological or economic harm or suffering to women, irrespective of whether they occur in public or in private. The term gender-based violence is commonly used to highlight the dynamics and drivers behind this type of violence. The terms gender-based violence and violence against women are often used interchangeably, as most violence against women is inflicted due to their gender. This Impact Assessment follows the approach of the Istanbul Convention and uses the term ‘violence against women’.

Domestic violence occurs within the household either between intimate partners (intimate-partner violence) or between other household members, including inter-generationally between parents and children. Thus, domestic violence covers not only women, but any person living in the household, including men, older people, same-sex partners, non-binary persons, and children.

Most forms of violence against women and domestic violence are criminal acts under national law and such violence, when targeted at women, is a form of sex-based discrimination.

In order to meet the objective of the Istanbul Convention effectively, this initiative takes into account the fast pace of the current digital transformation; it further deals with cyber-violence and sexual harassment, in particular at work. Although such types of violence are not explicitly covered by the Istanbul Convention, cyber violence against women and intimate partner cyber violence have become increasingly common in recent years. Cyber violence against women refers to online content or activity which targets the victim because she is a woman or targets women victims disproportionately. Cyber violence can also be perpetrated between current or former intimate partners. Cyber violence can take a variety of forms, ranging from cyber stalking and non-consensual sharing of private and intimate images or personal data to sexual cyber harassment. Experiences of online and offline violence are often interlinked. Cyber violence against women is a part of the continuum of the violence victims experience offline. Sexual harassment is included as it is currently covered by a number of gender equality directives which have proven not to be effective in preventing and combatting this type of violence against women (see gap analysis, Annex 8).

Violence against women and girls is a specific phenomenon in that its drivers are different from other types of violence (see section 2.2 below). Gender-based violence may affect both women and men, but women are disproportionately affected (see section 2.1.3. ‘Who is affected’ for details). This is the case in particular for sexual violence. Violence against women is rooted in structural inequalities between women and men and is the manifestation of historically unequal power relations, which have led to discrimination against women. Violence against women is often driven by misogyny. As explained in more detail in section 2.2.2, violence against women entails certain specificities, such as taking place in the private sphere, suffering from systemic under-reporting, disrupted criminal proceedings, the commonly sexual nature of crimes and/or a high prevalence of elements of coercive control. These elements are different compared to most violence experienced by men. For instance, violence against men usually occurs in public settings, is not usually of a sexual nature, and is generally perpetrated by other men. Men are also frequently victims of other types of violence, but are much less often victims of violence targeting them because of their gender. Also the consequences of violence against women include specificities, especially in regard to social consequences, which requires targeted action. Violence against women negatively impacts the physical health of the victims. Sexual violence exposes women to sexually-transmitted diseases, unintended pregnancies, abortions and miscarriages, and lowers women’s control over their reproductive health.

Violence against women and domestic violence also increase the probability of mental health problems, linking to higher rates of depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, alcohol and drug abuse, and suicidal ideation. In light of the above, the scope of the initiative focuses on violence against women, as this manifestation of structural gender inequality with its specific consequences requires a targeted approach, but includes, in relation to domestic violence, also men. Male victims of other types of violence than domestic violence are covered under the Victims’ Rights Directive that is applicable to all victims of crime and the Gender Equality Directives as regards harassment.

Violence on the basis of other grounds of discrimination than sex is not part of the primary scope of the current initiative. This does not mean that such violence does not merit addressing. However, as set out above the dynamics and consequences of violence against women and domestic violence require a specific approach. Nevertheless, special measures address the intersection of sex with other grounds of discrimination included in the Treaties, such as racial or ethnic origin, disability, religion or belief, age or sexual orientation. Also, the provisions regarding domestic violence include victims of such violence in all their diversity, including non-binary people. Specific measures to tackle violence and discrimination based on other grounds than sex are included in relevant sectoral EU initiatives and legislation. However, while this initiative would oblige Member States to implement minimum standards concerning violence against women only in relation to this group of victims, Member States would be encouraged to extend all measures to men and non-binary people.

2.1.2 Problem description

a)High prevalence of violence against women and domestic violence in the EU

Violence against women and domestic violence are widespread across the EU. Their prevalence and scale have been examined most comprehensively in the 2014 survey on violence against women of the Fundamental Rights Agency of the European Union (FRA), and confirmed in multiple studies and surveys carried out since then. These include the recent FRA survey on crime victims published in February 2021

and administrative data gathered by the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) from national authorities.

According to the 2014 FRA survey, one woman in three aged 15 or above reported having experienced some form of physical and/or sexual violence in the EU. One in 10 women reported having been victim to some form of sexual violence, and one in 20 had been raped. Just over one in five women have suffered physical and/or sexual violence from either a current or previous partner, whilst 43% of women have experienced some form of psychologically abusive and/or controlling behaviour when in a relationship. While both women and men experience cyber violence and harassment, women are overrepresented among victims of cyber violence perpetrated based on the victim’s sex, in particular sexual forms of cyber violence. In addition, women and girls more often report serious and disturbing forms of such violence, and report feeling more vulnerable after such violence and more harshly judged as victims. Usage of the internet and social media increases the risk of cyber violence. In a global 2017 survey on online abuse in eight countries, on average 23% of women reported having experienced abuse or harassment online. The 2014 FRA survey suggested that 20% of women aged 18–29 years old had experienced cyber violence since the age of 15.

In 2020, the World Wide Web Foundation found that 52% of young women were affected and over 80% were of the opinion the phenomenon was increasing.

In a recent study, more than 50% of all respondents replied they did not dare express political opinions due to fear of online targeting.

Data from 2017 illustrate that 70% of women victims of cyber stalking also experienced at least one form of physical or/and sexual violence from an intimate partner (see section 2.1.1 above).

Experiences of online and offline violence are often interlinked, showing that it is important to tackle them together.

Women also experience violence at work. About a third of women who have faced sexual harassment in the EU experienced it at work. According to the FRA survey, 32% of perpetrators of sexual harassment faced by women since they were 15 were from the employment context such as colleagues, supervisors or clients. When asked whether the perpetrator of sexual harassment was male or female, 71% of victims indicated that the perpetrator of an incident since the age of 15 was a man, 2% indicated a female perpetrator and 21% pointed to both male and female harassers. The results reflect that, although the sex of many perpetrators is unknown because of the nature of harassment – such as through the internet – this form of violence against women is perpetrated mostly by men.

The administrative data collected by EIGE shows that the prevalence of violence against women and domestic violence may be estimated at 21.2% (2019 figures), i.e. one in five women in the EU experienced violence against women or domestic violence. This figure is based on administrative data and only includes acts reported to the authorities. The severity, i.e. the percentage of women who experienced health consequences of physical and/or sexual violence, was estimated at 46.9%. The rate of disclosure to anyone of this kind of violence was estimated at 14.3%. It follows that almost half of these incidences cause health consequences for the victims but less than one in seven of them is reported.

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, violence against women and children, particularly domestic violence, has increased.

Stakeholders noted an increase in contact to helplines for victims of violence against women and domestic violence during the pandemic; an increase in the demand for specialised support services (emergency accommodation, counselling services); an increase of reports to law enforcement and in numbers of emergency protection orders issued in cases of such violence, while support services were required to reduce or temporarily stop work; an increase in risk factors for violence due to the pandemic (e.g. isolation, stress, working from home), coupled with a decrease in accessibility of victim support. Even if measures were taken to address this rise in violence, many victims were not in a position to look for help. This was often because victims were forbidden from leaving their homes, but also subject to technological control such as webcams, smart locks or a control via social media. Pending the end of the pandemic and the full manifestation of its social and economic consequences, it is still unclear whether this increase in incidence is temporary (e.g. an increase in intensity) or indicative of a trend. Although both the EU and its Member States, have taken measures to prevent and combat violence against women and domestic violence, significant gaps remain, both at the level of legislation and its implementation.

b)Gaps at national level

The studies carried out in support of this impact assessment show the fragmentation of the national regulatory frameworks. The heterogeneity of the existing measures correlates with different legal, historical and political traditions of the Member States. Standards of protection vary significantly between the Member States and the rights of victims of violence against women and domestic violence are not always enforced in practice. This leads to unequal protection depending on where in the EU violence against women and domestic violence is experienced. It is also problematic in situations where the victim moves or otherwise exercises their right to free movement in the EU. The gap analysis in Annex 8 provides a detailed assessment of gaps in the relevant EU and national legislation as well as the shortcomings in its implementation. The main gaps at national level are presented below, structured into the five problem areas which have been identified as relevant by the Istanbul Convention: prevention, protection, access to justice, victim support and policy coordination. Gaps at EU-level are set out in section c) below.

(1)Ineffective prevention of violence

All Member States have introduced prevention measures. In response to the targeted consultation, 23 Member States reported having organised awareness raising campaigns on violence against women and/or domestic violence. This is supported by the public consultation. In-country research, however, highlights a number of shortcomings with the existing campaigns, namely that they do not reach target groups meaningfully, with little emphasis on the right to be protected against violence against women and domestic violence. The Council of Europe’s Group of Experts on Action against Violence against Women and Domestic Violence (‘GREVIO’) has also noted challenges related to awareness-raising programmes. Although there are some good measures in place, they tend to focus on domestic violence, are too short-term and do not sufficiently target the problem of intersectionality. According to the gap analysis (see Annex 8), there is also a lack of awareness-raising initiatives to tackle underlying stereotypical attitudes (BE, IT, NL, PT)

as well as insufficient teaching material on gender equality (FI, IT, MT, SE)

.

Training is important to increase professionals’ skills to recognise victims. While general training is widely available to professionals,

targeted violence against women and domestic violence trainings, particularly concerning the interactions of police and judicial authorities with victims, are lacking. Moreover, trainings are not compulsory in most Member States for several categories of professionals. They are also not institutionalised and not available in the same manner and frequency for all categories. While police, judges, lawyers, and prosecutors are the most likely to receive training, few Member States provide other personnel in public administration who come into contact with victims with training.

Lack of training of social workers and relevant court appointed professionals has been identified as insufficient in some Member States (FR, IT, MT, PT).

Many Member States have insufficient initial and in-service trainings and lack of guidelines based on a gendered understanding of violence against women and domestic violence (AT, BE, DK, FI, FR, IT, MT, NL, PT, ES, SE

). Staff of relevant services should likewise be aware of the effects of domestic violence on children, including of witnessing domestic violence (FR, IT).

Work with perpetrators to prevent re-offending, as well as with men and boys at risk of offending, has a positive impact on combating violence against women and domestic violence. While all but one Member State (HU) have set up support programmes for perpetrators of violence against women and domestic violence, these programmes are often not structured, primarily targeting domestic violence and not always compulsory.

In many Member States, programmes for perpetrators are not sufficiently available or suffer from low attendance (DK, IT, PT, AT, FI, MT, NL).

Regarding sexual harassment at work, the gap analysis identified shortcomings in the effectiveness of the implementation of the Gender Equality Directives, which require Member States to take measures to prevent all forms of sex-based discrimination in the areas of employment and access to and supply of goods and services.

They however do not contain explicit provisions on preventing such harassment. Gaps identified in the Member States include insufficient knowledge of the issue by relevant professionals. EU law does not include explicit obligations on the prevention of cyber violence against women either.

(2)Ineffective protection from violence

Many Member States have made efforts to put measures in place to protect victims of violence against women and domestic violence, including against intimidation or retaliation by the perpetrator, but these are insufficient in some Member States.

While mid- and long-term protection orders are available in all Member States, these orders are not always effective. In addition, emergency protection or barring orders where the police are allowed to prevent an alleged or potential perpetrator of violence from entering the victim’s apartment and its immediate surroundings, are available only in 18 Member States.

Even where protection orders are available, their practical application remains low. Factors which might contribute to this are notably the length of proceedings and the limited enforcement of the measures, in particular insufficient sanctions for breaches of the orders and a lack of awareness on their availability. In some Member States, there is a lack of effective and immediate protection after reporting (AT, EE, DE, NL, PL, PT).

Also, victims who move or travel abroad risk losing protection, since the wide divergence of national measures remain an obstacle to the recognition of measures issued in their home country in other Member States.

As set out in detail in the gap analysis (Annex 8), an individual assessment of the specific protection needs of victims of violence against women and domestic violence is absent in eight Member States (CZ, BE, EE, LU, MT, RO, SI and SK). Measures ensuring specific protection of child victims or witnesses of violence against women and domestic violence also remain insufficient. Relevant professionals lack appropriate training to provide protection and support in a child-friendly manner (FR, IT), sufficient psychological counselling is not provided for child witnesses (AT, FI, FR, ES) and child witnesses are not always considered victims of violence.

Reporting of violence by children should be child-friendly, and there should be a possibility for visits with family members suspected of this kind of violence to take place in a safe, surveyed place and in the best interest of the child (arrangements in place e.g. in ES, FI, DE, MT).

(3)Ineffective access to justice for victims of violence

Several shortcomings limit access to justice for victims of violence against women and domestic violence.

While the majority of violence against women and domestic violence offences are criminalised in all Member States, gaps and divergences in national criminal law remain.

Large gaps exist with respect to cyber violence against women and intimate partner cyber violence, such as ICT-facilitated stalking and non-consensual dissemination of private images. In 17 Member States, non-consensual dissemination of intimate/private/sexual images online has not been criminalised (AT, BG, HR, CY, CZ, DK, EE, FI, DE, EL, HU, LV, LT, LU, RO, SK, SI).

Gaps in criminalisation also exist in the area of domestic violence, because the majority of national definitions require repetition of violent acts in order for them to fall under the criminal offence of domestic violence. Such a requirement of re-victimisation can pose challenges for prosecution, as well as reinforce secondary victimisation. Also, sexual violence within intimate relationships is not always recognised as domestic violence.

The use of force or threats as an essential element of rape is required in 16 Member States instead of focusing on lack of consent, as recommended by human rights bodies. This results in unequal protection and an important gap in access to justice for victims of sexual violence across the EU. Gaps also exist with respect to other forms of violence against women and domestic violence, which may negatively affect access to justice: female genital mutilation (FGM) is not a specific criminal offence in 9 Member States, forced marriages are not explicitly criminalised in 7 Member States and while all Member States have criminalised forced abortion, forced sterilization has been introduced as a specific criminal offense only in France, Malta, Portugal and Spain.

The lack of targeted training on violence against women and domestic violence for law enforcement and judicial authorities can lead to insufficiencies in the investigation and the judicial process. The majority of Member States have established ex officio prosecution for some violence against women and domestic violence crimes, yet a small minority have dedicated guidelines for the prosecution to ensure that this is done effectively in a manner taking into consideration the specificities of this kind of crime.

Difficulties in evidencing violence during judicial proceedings can also form a barrier to accessing justice. In particular in cases of sexual violence, there are typically no witnesses and there may be no physical signs left by the time the victim has a medical examination. It is also often not clear who (the police, medical professionals, support organisations) should be responsible for providing information and support. The prospect of investigation and prosecution can hinder a victim from reporting a crime and initiating judicial proceedings, as victims may want to avoid secondary victimisation by not repeating the original trauma during the proceedings. Lack of measures protecting victims against retaliation and repeat victimization has been identified as a gap in some Member States (AT, FR, DE, NL, PL, PT).

Lack of reporting was highlighted by six Member State authorities in the targeted consultation as one of the main challenges in the prosecution of cases of GBV (BE, BG, CY, DE, IE, RO).

Furthermore, access to compensation has not been effective with regard to victims of gender-based violence, including violence against women and domestic violence. The amount of compensation is very low, which may have particularly damaging consequences for victims of VAW/DV as they often need to re-build an independent and violence-free life of dignity, especially as domestic violence can often occur in situations of economic dependence.

In addition, victims may have to go through both criminal and civil proceedings to claim compensation, which exposes them to a high risk of revictimisation.

Some Member States have restricted time limits to apply for state compensation (AT, CY, HR, HU

, EL

). Finally, victims are not aware of their rights (see gap analysis, Annex 8).

Regarding sex-based, including sexual, harassment, reporting and dispute resolution mechanisms are often not readily accessible or gender-sensitive, and involve lengthy proceedings. The Gender Equality Directives require Member States to prohibit sex-based and sexual harassment and provide effective remedies in the areas of employment and access to and supply of goods and services. Lacking criminalisation of sexual harassment (see also Section 3.1.1), retaliation measures towards complainants, lack of case-law, and insufficient knowledge of the issue by relevant professionals are identified as gaps in the Member States.

Stakeholders indicate that victims of cyber violence against women and intimate partner cyber violence often struggle in accessing remedies. Law enforcement is often not adequately aware or equipped to address the specificities of the digital dimension of violence against women and domestic violence. In particular, there are often no facilities to report incidents online and cyber violence may be harder to prosecute for non-specialised authorities.

Insufficient information on what constitutes cyber violence and on the reporting options also leads to underreporting.

The role of national equality bodies to deal with cases of violence against women beyond sexual harassment is limited in the majority of the Member States, which equally limits access to justice (BG, HR, CY, CZ, DK, FI, FR, EL, HU, IE, IT, LT, LV, LU, MT, NL, PL, RO, SK, ES.

(4)Ineffective support to victims of violence

Support services, such as counselling and shelters for victims, are fundamental in ensuring the well-being of victims, need to be based on an understanding of the victim’s specific needs and be available for all victims in a manner that ensures confidentiality and privacy.

While all Member States have general support services in place, i.e. service provision to the public at large, including social services, health services and employment services, stakeholders

identified an insufficient number of specialist support services for victims of violence against women and domestic violence, which can cover targeted social, emotional, psychological and financial support, as well as practical and legal support specifically designed for victims of violence against women and of domestic violence. For example, there is a gap in specialised support services dealing with forms of violence against women other than domestic violence, such as sexual violence (AT, BE, FR, MT, PT, ES).

There is, in particular, an insufficient number of shelters available to victims of violence against women and domestic violence. GREVIO refers to discrepancies in the information provided by Member State authorities and civil society organisations on the numbers of shelters and observes that, with the exception of Austria and Malta, Member States are not close to reaching the target put forward by the Council of Europe to set up one family place per 10,000 heads of population.

There are furthermore limitations to accessing the existing support due to conditions related to citizenship, residency, economic means, or dependents (children). In some Member States, women with children have more difficulties to be accepted to support services or supported. In the majority of Member States, access to shelters is particularly difficult for women with disabilities and mothers of children with disabilities. In several Member States, specialised support services are available only to citizens of the country or even to residents of the respective area/region/municipality. The gap analysis shows that there are significant barriers for migrant and asylum seeking women to access general and/or specialised support services (BE, DK, IT, NL,ES, SE). There are also problems of access to support services depending on geographical location. Access to support may also depend on the victim’s willingness to bring charges against the perpetrator.

While several Member States have developed a wider and stronger network of specialist support services that assists victims of domestic violence, a gap has been identified concerning specialised support to children, including child witnesses of violence against women and domestic violence, especially of psycho-social counselling and other child-sensitive support. Such support needs to be provided with regard to the best interests of the child and their needs, which may exclude shelters as the primary temporary housing solution. The gap analysis also identified a lack or insufficiency of national state-wide, 24/7 and free of charge helplines to women victims of violence (BE, BG, HR, CY, CZ, FI, FR, EL, HU, IE, LV, LT, LU, MT, NL, PL, PT, SI). There is also lack of multilingual support on national women’s helplines (BE, HR, CZ, HU, LV, LT, MT, NL, PL, PT, SI).

There are also gaps in support for victims of cyber violence against women. The gap analysis identified a lack of measures tackling this kind of violence and the related support services in the majority of the Member States (AT, BE, BG, HR, CY, CZ, DK, EE, FI, DE, FR, HU, IE, IT, LV, LT, MT, NL, PL, PT, RO, SK, SI, ES, SE).

Service provision is commonly ensured by victims’ rights and women’s organisations, which are staffed with experienced specialists. These organisations report a lack of sufficient resources for staff, professional training and financial assistance to run the services as well as a lack of recognition of their work by national governments.

(5)Insufficient policy coordination

Due to the involvement of various public and possibly private sector actors in cases of violence against women and domestic violence, coordination is required to ensure concerted action. Coordination at national level can be substantiated by national plans of action that assign each actor a particular role. In addition, due to the high prevalence of violence against women and domestic violence across Europe and globally, Member States participate in international coordination efforts. According to national and desk research, however, the implementation of the legislative and policy framework shows gaps in most Member States. The realities are diverse and complex in each Member State, but commonly identified problems are lack of coordination between different institutions with mandates in the area; differences in resources and in quality of the service delivery between urban and rural/remote or more and less developed areas.

There are also shortcomings in the collection of data on violence against women and domestic violence, as noted by GREVIO in a recent report on the implementation of the Istanbul Convention. High quality data is a crucial basis for effective policy-making and these shortcomings make it challenging to form an accurate overview of the prevalence of violence against women and domestic violence in the EU. Data on the prevalence of violence against women and domestic violence is gathered through administrative data collection and survey data. Data collected from administrative sources is not adequately disaggregated. For example, data on perpetrators are typically not disaggregated by sex, which is an obstacle to the visibility of violence against women and domestic violence in their different forms. Data also does not systematically cover the sex and age of the victim or the relationship with the perpetrator. The lack of sex disaggregated data on victims/perpetrators of violence collected by the criminal justice system has been identified as problem also in the gap analysis in Annex 8 (BE, DK, MT, NL).

Moreover, data collection between public bodies is not harmonised. The gap analysis identified this as a problem in several Member States (AT, BE, DK, FI, FR, IT, MT, SE).

The lack of co-ordination and comparability of the data (including a lack of common definitions and units of measurement) makes it impossible to track cases at all stages of the law-enforcement and judicial proceedings, and during support. It impedes an assessment of conviction, attrition, and recidivism rates, as well as the identification of gaps in the responses of institutions. An estimated 2/3 of victims do not report violence, and therefore, official criminal justice data only record a limited number of cases. This is why it is important to be able to rely on population survey additionally to police statistics.

The only available, comparable data at the EU level is the FRA survey from 2014. Currently, Eurostat is coordinating an EU survey on gender-based violence and other forms of interpersonal violence. 18 Member States will carry out the survey (which is supported by EU funds) while others declined to participate mostly because of human resources constraints. FRA and EIGE are stepping in to complete the results for these Member States. Results for all countries are expected in 2023. To monitor developments, it would be necessary to carry out the survey on a regular basis by all Member States in the future.

c)Gaps at EU level

There is currently no specific EU legal instrument addressing violence against women and domestic violence. The topic falls, however, in the scope of application of several directives and regulations, in particular in the areas of criminal justice, gender equality and asylum. The existing EU legal framework for addressing violence against women and domestic violence was assessed for the purposes of this initiative; this assessment concludes that the current legal framework has significant gaps and shortcomings with regard to this group of victims, which has come to the forefront particularly due to the increased risk of domestic violence following the confinement measures of the COVID-19 pandemic (see Annex 8 for details).

The gap analysis in Annex 8 also shows that the relevant EU legislation has been ineffective in preventing and combatting violence against women and domestic violence. While there is no EU legislation dedicated to such violence, the gap analysis identified 14 EU law instruments which are relevant for victims of violence against women and domestic violence as they either establish general rules applicable also to this category of victims, or establish specific rules on certain forms of such violence. For example, the provisions on protection and access to justice in the Victims’ Rights Directive and the European Protection Orders (‘EPO’) apply to all victims of crime, whereas the Directives on child sexual abuse or trafficking in human beings establish sectoral rules on these forms of violence. In addition, the Gender Equality Directives include provisions on sexual harassment. The assessment supplements and builds on the on-going general evaluations of some of these instruments, in particular those concerning the Victims’ Rights, the Child Sexual Abuse and the Anti-Trafficking Directives.

With regard to prevention, the EU framework includes some obligations on awareness-raising, but these either concern victims’ rights in general, or are limited to specific forms of violence, such as trafficking in human beings, child sexual abuse or sexual harassment at work. As to training for professionals, EU legislation provides some obligations for the Member States, but such provisions are not specific to violence against women and domestic violence.

When it comes to protection of victims, the instruments on the mutual recognition of protection orders provide for cross-border recognition of criminal and civil protection orders. However, the take-up of the EPO instruments is very low which limits their effectiveness. Moreover, the instruments do not ensure that effective emergency barring orders and protection orders are available and effective in all Member States. As set out above, emergency protection orders do not exist in all Member States and the modalities for their issuance vary. Lack of efficiency of the protection orders at the national level results in a poor take-up of protection orders in cross-border cases and as a consequence in a very low application of the EU EPO instruments.

The insufficient and unequal criminalization of different forms of violence against women and of domestic violence makes it more difficult for victims to access justice. EU-level criminalisations of specific forms of violence against women with harmonised definitions and sanctions are currently included in the Anti-Trafficking and the Child Sexual Abuse Directives. While most conduct of violence against women and domestic violence is criminalised at national level, the situation at EU level leaves important gaps, in particular with regard to sexual harassment and cyber violence against women and intimate partners (see above, Section 2.1.2). This directly impacts the victims’ access to justice. In cases of cyber violence, if national law enforcement mechanisms are unavailable, victims can complain to the online platform. Effective means of redress are however not always provided by the platform, which is particularly problematic for serious forms of cyber violence. Similarly, with regard to sexual harassment, EU law obliges Member States to prohibit sexual harassment as a form of discrimination and impose sanctions. They however do not require, for most serious cases, criminal sanctions. Lack of adequate compensation remains a challenge and obstacle for this group of victims in accessing justice, despite the minimum standards of the Compensation Directive and, for sexual harassment, the Gender Equality Directives. The amount of compensation attributed in violence against women and domestic violence cases is often very low and compensation is not granted in adequate time.

Concerning access to support for this group of victims, the Victims’ Rights Directive has not reached its full potential: implementation remains dissatisfactory. The complexity and broad formulations in the Victims’ Rights Directive often cause obstacles in its practical application. The broad formulation of the provisions concerning support to victims of violence against women and domestic violence further effects the quality of the non-legislative measures taken pursuant to the Directive. Implementation issues were identified in several Member States on access to shelters, including their availability and numbers. Such shortcomings tend to particularly affect victims of violence against women and domestic violence. Moreover, only 13 Member States reported that their specialist support services systematically take into account the special needs of child victims and witnesses in cases of domestic violence and ten additional Member States applied a child sensitive approach in a non-systematic manner. Courts also regularly categorise child witnesses as indirect victims, despite it being standard practice in child protection to consider child witnesses as direct victims due to the psychological harm inflicted. This can hinder children’s access to services, such as counselling.

Regarding cyber violence against women and between intimate partners, the existing EU legal framework does not include specific obligations in this regard. The Victims’ Rights Directive applies to all criminalised conduct, but forms of cyber violence against women are only criminalised in 11 Member States. Hence, victims of such violence are often not eligible for protection and support measures under the Directive.

The Gender Equality Directives

establish that sex-based and sexual harassment at work and in the access to goods and services are contrary to the principle of equal treatment between men and women, and oblige Member States to prohibit such conduct, ensure remedies and enforcement, including compensation, and provide for effective, proportionate and dissuasive penalties. However, these provisions have not been effective in reducing the prevalence of sexual harassment (see Section 2.1.2 (b) at 1 and 3).

More generally, the gap analysis shows that the relevant EU legislation has been ineffective in ensuring the rights of victims of violence against women and domestic violence. The EU-level measures do not explicitly address victims of violence against women and domestic violence. The relevant obligations are not specific enough with regard to victims of violence against women and domestic violence or leave wide discretion to the Member States. The relevant EU legislation is not up to date; it is on average over ten years old and the international obligations have evolved considerably in the area of violence against women and domestic violence in the meantime (see below).

Finally, EU law is no longer coherent with the international legal and policy framework. Concerning violence against women and domestic violence generally, EU law remains below the standards of the Istanbul Convention and the CEDAW Convention with regard to this group of victims. The relevant provisions of EU law are mainly formulated in a gender-neutral manner and do not require Member States to take into account the specific needs of women victims of violence and victims of domestic violence. In addition, EU law includes few provisions on targeted preventive measures, and fails to address the protection needs of these victims with the specificity required in Chapter VI of the Istanbul Convention. With the exceptions of child sexual abuse and trafficking in human beings for the purposes of sexual exploitation, EU law does not establish harmonised definitions and sanctions of most of the forms of violence against women and domestic violence enumerated in the Istanbul Convention. The framework does not address the rights of witnesses, particularly child witnesses, of such violence. All Member States have ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, which in its Article 19 includes provisions on prevention, protection, support and access to justice to children affected by violence. General and specific support services to this group of victims are regulated in the Victims’ Rights Directive, but the lack of detail in the provisions has led to ineffective implementation by the Member States. There is currently no obligation on the Member States to collect data specifically on violence against women and domestic violence, and no specific EU-level coordination structures exist on this kind of violence. The gap analysis further finds that action at national level is likely to have resulted from the implementation of the Istanbul Convention in those Member States that are parties.

Since the adoption of the directives, the international #MeToo movement has raised the visibility of sexual harassment against women, potentially encouraging more victims, but also governments, social partners and employers, to take action. In 2019, the International Labour Organization adopted the Violence and Harassment Convention No. 190, which requires parties to prohibit gender-based violence and harassment at work and provides a comprehensive protection, prevention, and support framework for victims. EU law does not ensure the criminalisation of serious forms of sexual harassment; the applicability of the protection and support measures of the Victims’ Rights Directive therefore depends on whether harassment is criminalised under national law. The prevention, protection and support measures concerning sexual harassment are also not as developed as in Convention no. 190.

Finally, the current EU legislation has not led to effective monitoring and enforcement of the relevant EU rules with regard to violence against women and domestic violence. This is due to the absence of a focus on such violence and the ambiguous drafting of the legal obligations, which has not enabled targeted enforcement measures in the key problem areas relating to violence against women and domestic violence.

2.1.3.Who is affected?

Gender-based violence is disproportionately perpetrated against women. In the majority of cases of physical violence, the perpetrator is a man or a group of men.

Although women and girls account for a far smaller share of total victims of homicides than men, they are overrepresented among victims of intimate partner/family-related homicide, and intimate partner homicide. Victim/perpetrator disaggregations reveal a large disparity in the shares attributable to male and female victims of homicides committed by intimate partners or family members: 36 per cent male versus 64 per cent female victims. These findings show that even though men are the principal victims of homicide globally, women continue to bear the heaviest burden of lethal victimization as a result of gender stereotypes and inequality. In particular sexual violence is strongly gendered with more than 9 in 10 rape victims and more than 8 in 10 sexual assault victims being women and girls, while nearly all those imprisoned for such crimes are male (99%).

Research also suggests that more women than men become victims of sexual harassment or sex discrimination. Incidents of physical violence against women (excluding specifically sexual violence) most often take place at home (37%). Such violence also often involves a family member or a relative as the perpetrator. Thus, although men and non-binary people can also be victims of gender-based violence, the majority of victims are women in all their diversity.

Cyber violence against women has been found to target in particular young women and women visible in public life. Women in public positions, such as journalists and politicians, experience cyber violence targeting them because they are women and seeking to question their entitlement to participate in societal discussions. This can have a silencing effect on the victims and negatively affect democratic decision-making processes.

Similarly, while both women and men experience harassment, women face more harassment of a sexual nature. In a 2012 survey, up to 55% of women in the EU-28 (ages 18–74) reported having experienced sexual harassment since the age of 15. One in five (21%) had experienced at least one form of sexual harassment in the 12 months before the survey. Such harassment consists of forms such as unwanted touching, hugging or kissing, or sexually suggestive, unwanted comments or cyber harassment. In 2021, 18% of women described the most recent incident of harassment as of a sexual nature, compared with 6% of men.

Women and girls in vulnerable situations, such as women with disabilities, women victims of trafficking in human beings, women prisoners, women migrants and asylum seekers, non-heterosexual women and women sex workers, are at a higher risk of violence. For example, exposure to physical or sexual partner violence differs between women with and without disabilities (34% vs 19%) and non-heterosexual and heterosexual women (48% vs 21%).

Human traffickers exploit the particular vulnerabilities of persons with disabilities for the purpose of sexual exploitation.

Children are often seriously affected by violence against women and domestic violence. They can be themselves victims or witnesses of such violence; both experiences are considered to be equally traumatizing. Exposure to violence at an early age can cause impairments to the brain and nervous system development, as well as result in life-long negative coping and health risk behaviours. Children who witness or are victims of emotional, physical, or sexual abuse are also at higher risk for health problems as adults. These can include mental health conditions, such as depression and anxiety.

While the exact prevalence of violence against women and domestic violence varies among Member States, it is widespread in every Member State regardless of socio-economic boundaries.

2.1.4.Why is violence against women and domestic violence a problem?

Violence against women and domestic violence can violate a number of fundamental rights, including the right to life and to equality between women and men (see Section 6.1). They cause pain and suffering to the victims and result in large costs on the economy and society as a whole. They negatively impact the physical health of the victims. Sexual violence exposes women to sexually-transmitted diseases, unintended pregnancies, abortions and miscarriages, and lowers women's control over their reproductive health.

Violence against women and domestic violence also increase the probability of mental health problems, linking to higher rates of depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, alcohol and drug abuse, and suicidal ideation.

Some of the social and health impacts of violence against women and domestic violence can be quantified in terms of costs and/or economic consequences. For the EU, EIGE has carried out two studies on the costs of violence in 2014 and 2021. The 2021 study considers three main sources of costs: direct cost of services (to victims or to public providers); lost economic output; and physical and emotional impacts measured as a reduction in the quality of life.

Direct cost of services consists of the use of services provided by various sectors to mitigate the harm caused by violence. This includes the use of health services to treat the physical and mental harms; social services; the criminal justice system involved in the investigation, prosecution and adjudication of cases of violence against women and domestic violence; the civil justice system to e.g. disentangle from a violent partner; and specialist services for the prevention and/or mitigation of the impacts, such as protection and support services. Victims of intimate partner violence may incur costs not covered by the state, notably judicial costs and the costs of a new home.

Violence against women and domestic violence also result in lost economic output, as a result of the victim’s decreased ability to look for a job or productivity on the job and the time taken off work to handle the consequences of the crime. According to a European Parliament Research Service (‘EPRS’) study, research conducted in Belgium found that 73% of those subjected to domestic violence reported an effect on the ability to work. Another recent EPRS study estimates the lost economic output due to mental health impairments caused by cyber-violence on women, both in terms of lost work days and lower productivity. A study on the costs of violence against women in Italy calculates the costs of work days lost, reduced productivity, and the cost of replacing absent workers. It furthermore calculates the lost tax income and the multiplier effect of households' lost incomes.

The third cost category in the EIGE study is the physical and emotional impact on victims, measuring the loss of healthy life years. This allows a monetary value to be attached to health conditions to translate losses usually not measured in money into economic losses. The greatest source of economic loss due to violence against women and domestic violence is the loss in quality of life that monetises the physical and emotional impacts of violence.

On this basis, the 2021 EIGE study estimates that total yearly costs of gender-based violence against women in the EU-27 stand at €290 billion and almost €152 billion for domestic violence. These costs, consist in large part of physical/emotional impacts (55.57%), criminal justice system (20.43%) and lost economic output (13.93%) (see Annexes 3 and 5).

2.2.

What are the drivers?

2.2.1Structural gender inequality and gender stereotypes

Whilst there is no single cause for violence against women and domestic violence, some of the most consistent drivers are harmful social norms and stereotypes that contribute to gender inequality. Such social norms concern the roles of women and men; harmful gender stereotypes include ideals linking masculinity to the provider role, macho behaviour, as well as ideals linking femininity to chastity, submission and victimhood. The WHO has identified community norms that ascribe higher status to men, low levels of women’s access to paid employment, and low level of gender equality as factors increasing the risk of violence against women and domestic violence.

Societal norms affect perpetrators’ and bystanders’ behaviours. Perpetrators may not consider their act of violence as morally reproachable.

Gender roles and stress over masculine gender roles have been found to strengthen tolerance toward violence against women

, which may, in turn, be caused by factors such as negative stereotypes towards women. Tolerant attitudes towards violence against women may be further encouraged by the social environment, leading to a circle of violence.

Another key cause of attitudes and behaviour is the lack of a common understanding of violence against women.

The 2016 special Eurobarometer on gender-based violence depicts these problematic assumptions, as 27% of the respondents said that sexual intercourse without consent may be justified in at least some situations. Although most people would agree that rape is morally wrong (i.e. negative attitude), not all would agree on what constitutes rape.

Tolerant attitudes towards violence against women have also been observed with respect to some forms of sex-based harassment. In some Member States, tackling sex harassment at work was not considered a real issue.

Some forms of violence against women and domestic violence are sometimes considered a private matter. Thus, in the 2016 Eurobarometer, one in six respondents believed that domestic violence should be handled within the family. About one in five expressed victim-blaming views, agreeing that women make up or exaggerate claims. Just under one in five (17%) held that violence against women is often provoked by the victim, with respondents in the Eastern European Member States the most likely to agree.

2.2.2.Failure to recognise the specificities of crimes and offences relating to violence against women and domestic violence

Criminal acts of violence against women and domestic violence have specific characteristics, such as systemic under-reporting, disrupted criminal proceedings, the commonly sexual nature of crimes and a high prevalence of elements of coercive control. Rates of reporting violence against women and domestic violence to the police are low.

According to the FRA 2014 survey, victims reported the most serious incident of partner violence to the police only in 14% of cases and the most serious incident of non-partner violence in 13% of cases. In 2021, FRA confirmed that reporting of violence and harassment in general was less common than that of other crime, and that reporting crime to the police was less common when the perpetrator was a family member or a relative (only 22% of incidents were reported).

The reasons for not reporting violence against women and domestic violence are multiple. They include the trouble involved in reporting an incident if the victim perceives that the police will not take her seriously or will be unwilling to do anything about the crime. Furthermore, for around one quarter of victims of sexual violence by a partner or non-partner, feeling ashamed or embarrassed about what happened was the reason for not reporting the incident to the police or a support organisation. Victims may also fear retaliation from the perpetrator or consider the violence a private matter.

In addition, they may be hesitant to report an incident perpetrated by a family member or, in cases of sex-based or sexual harassment at work, a hierarchical superior or a colleague.

The above specificities hamper efforts to effectively address violence against women and domestic violence. Incidents may be difficult for authorities to address, since victims may not disclose their experience or withdraw statements and discontinue participation in investigations or court proceedings. These dynamics interfere with efforts to ensure an appropriate follow-up within the judicial system or through support mechanisms. They also underline the need to ensure the accessibility of support regardless of whether the victim has officially reported the violence.

Due to the specificities of crimes and offences relating to violence against women and domestic violence, gender-sensitive measures are needed. In their Evaluation Report on Finland, GREVIO noted that gender-neutral approach in policy making and service provision is not sufficient and does not provide women victims of violence and domestic violence effective protection, support and access to justice. GREVIO notes that this may not always do justice to the particular experiences of women as victims of domestic violence, who are more frequently and more severely impacted. Moreover, the European Court of Human Rights also requires Member States to adopt a gender-sensitive approach in their measures to prevent and combat such violence (see Section 6.1 for details).

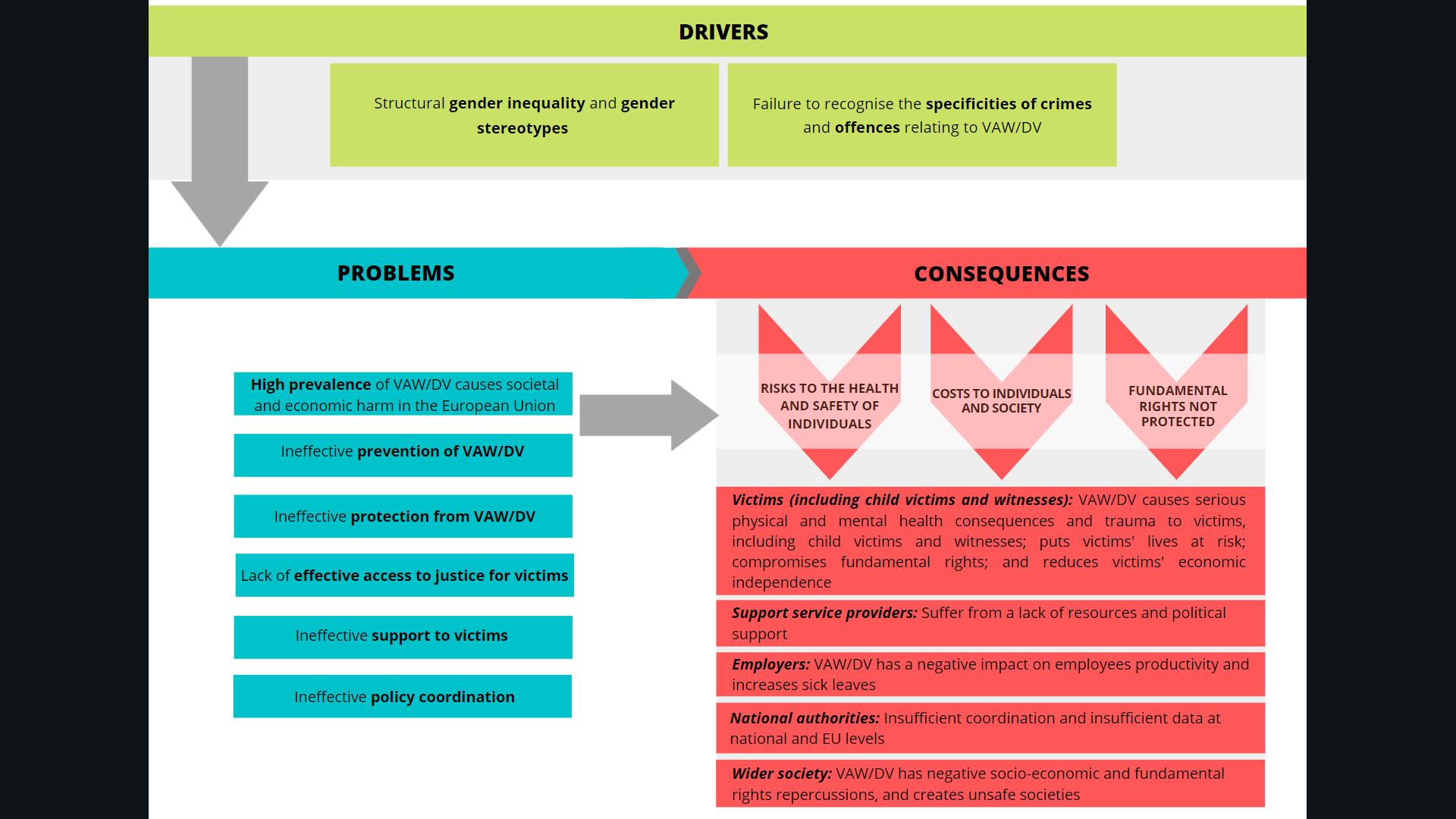

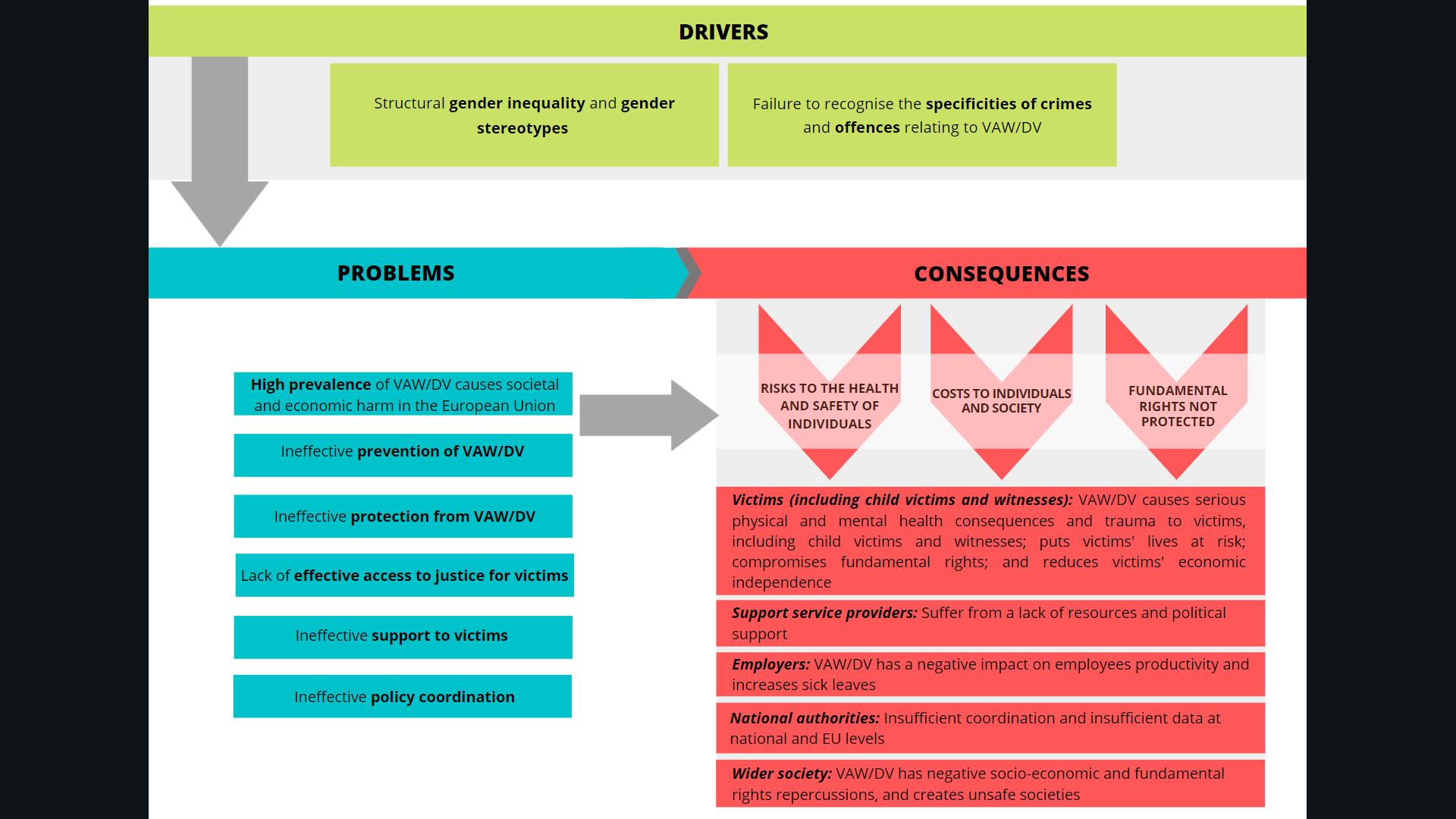

Figure 1 - Problem tree

2.3.

How will the problem evolve?

Based on the evolution of the situation in the past decades, it is unlikely that the prevalence of all forms of violence against women and domestic violence, as measured through administrative and survey data, will decrease significantly without additional policy intervention. All Member States have adopted policy and legislative measures on this kind of violence, and 21 Member States have taken measures pursuant to their obligations under the Istanbul Convention. The gaps concerning prevention, protection, access to justice, support and coordination can however be expected to persist (see Section 3.1.3). Stakeholders, such as non-governmental and international organisations, note that without further action at EU level, national legislation and practice are unlikely to develop sufficiently and in a coordinated manner in line with international standards to ensure that the needs of victims of violence against women and domestic violence are sufficiently addressed throughout the EU (see Annex 2).

3.3.

Why should the EU act?

3.1.

Legal basis

The initiative pursues the general objective of preventing and combatting violence against women and domestic violence. As confirmed in Declaration No. 19 on Article 8 of the TFEU, combatting ‘all kinds of domestic violence’ is part of the Union’s general efforts to eliminate inequalities between women and men and Member States should take all necessary measures to prevent and punish these criminal acts and to support and protect the victims.

The initiative would build on the Victims’ Rights Directive and establish minimum standards on the rights of victims of all forms of violence against women and domestic violence, constituting a lex specialis to this Directive, in the same way as victims of terrorism and trafficking have been addressed through specific legislation. It would include measures aimed at preventing this kind of violence, and ensuring adequate protection, access to justice, support and coordination before, during or after criminal proceedings by responding to the specific needs of victims of violence against women and domestic violence. The relevant legal basis, in line with the Victims’ Rights Directive, would be Article 82(2) TFEU. This provision provides for the establishment of minimum rules concerning the rights of victims of crime, to the extent necessary to facilitate mutual recognition of judgments and judicial decisions and police and judicial cooperation in criminal matters having a cross-border dimension.

In addition, the initiative would introduce minimum standards on the definition of criminal offences in the areas of crime set out in Art. 83(1) relating to sexual exploitation of women and children and computer crime. Article 83(1) TFEU allows for the establishment of minimum rules concerning the definition of criminal offences and sanctions in the areas of particularly serious crime with a cross-border dimension resulting from the nature or impact of such offences or from a special need to combat them on a common basis.

It would further introduce, on the basis of Art. 83(2), minimum rules concerning the definition of serious forms of sexual harassment to ensure effective application of the Gender Equality Directives, which regulate this matter by providing definitions and requiring prohibitions and sanctions for sex-based and sexual harassment. Article 83(2) provides for the establishment of minimum rules with regard to the definition of criminal offences and sanctions in an area which has been subject to harmonisation measures, if the approximation proves essential to ensure the effective implementation of the Union’s policy in this area. The background studies conducted for the initiative show that the implementation of the relevant provisions has not been effective, and sexual harassment continues to remain common in the Member States. In order to ensure effective implementation of the policy, harmonisation measures with regard to the definition and sanctions of serious forms of sexual harassment are essential to ensure the effective implementation of the Union’s policy.

When proposing EU accession to the Istanbul Convention, the Commission took the view that the appropriate legal bases for action in regard to the matters covered by the Convention are the Treaty provisions in the fields of judicial cooperation in criminal matters and crime prevention. In its Opinion on the EU accession of 6 October 2021, the CJEU confirmed that view. The Court takes a broad view on the types of measures that can be adopted on these legal bases, in particular in the areas of prevention, protection, victim support, and access to justice, as envisaged in this initiative. The Court also clarified that aspects of substantive criminal law remain the primary responsibility of Member States and that criminalisation of specific types of conduct remains to a great extent subject to national law. The initiative takes this into account by proposing criminalisation only to a very limited extent. It would thus be based on the combined legal basis of Art. 82(2) and 83(1) and 83(2) TFEU. These provisions provide for the adoption of directives in accordance with the ordinary legislative procedure as the appropriate instrument.

3.2.

Subsidiarity: Necessity of EU action

The continuous EU-wide prevalence of violence against women and domestic violence and the serious harm caused to individual victims and societies create a special need to combat such violence on a common basis in the EU. In light of prevalence data and cost estimations, the impact on European societies is considerable. Millions of EU citizens and persons residing in the EU are concerned. Violence against women and domestic violence violate the fundamental rights of citizens and affects gender equality, one of the fundamental values of the EU.

In addition, cyber violence against women and in intimate partnerships has emerged as a new form of violence against women and domestic violence, spreading and amplifying beyond individual Member States. The internet is inherently a cross-border environment, where content hosted in one Member State can be accessed from another Member State. As noted in the DSA proposal, interventions by one Member State will be insufficient to solve the issue.

In some cases, violence against women and domestic violence includes a physical cross-border element. On average 8% of women in the EU-27 report having experienced physical violence in the past five years.

This corresponds to more than 19 million women in the EU-27. On average 3% of women victims of all physical violence reported the violence to have taken place abroad.

Although it is not possible to establish the precise share, women victims of violence against women and domestic violence in cross-border situations are likely to be in the order of several hundreds of thousands in Europe annually, also taking into account possible underreporting.

In other cases, the cross-border nature may arise at a certain point during proceedings, for instance, if a suspect flees or a victim moves to another country. Even after criminal proceedings have concluded with a final judgment imposing a sentence on the defendant in the Member State of nationality, the case can necessitate judicial cooperation between Member States. Cross-border elements may equally arise when criminal cases are transferred to another Member State.

The current initiative not only covers physical cross-border dimensions of violence against women and domestic violence, but the rights of victims of these crimes in general. In its opinion of 6 October 2021, the Court broadly lists the measures in the Convention related to victims’ rights (prevention, protection, support, access to justice) for which the EU has competence, not presupposing the existence of a physical cross-border element in all respects of the problem considered.

Within the limits of EU competence as indicated by the CJEU, the issue should be addressed at EU level in order to ensure a minimum level of protection of victims’ rights and fundamental rights. The objective is not to achieve harmonised, equal protection everywhere in the EU, but to establish minimum standards for rights from which all victims of such violence in the EU should benefit. The existence of minimum standards would also facilitate the mutual recognition of protection orders and judicial decisions concerning violence across the EU, thereby supporting a better application of the existing acquis in this area (see section 2.1.2).

3.3.

Subsidiarity: Added value of EU action