EUROPEAN COMMISSION

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Brussels, 30.11.2020

SWD(2020) 294 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

First short-term review of the Geo-blocking Regulation

Accompanying the document

Report

from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of Regions on the first short-term review of the Geo-blocking Regulation

{COM(2020) 766 final}

Table of Contents (Part 2/2)

3.

Analysis of feasibility and impacts of changes to the scope of the Regulation

3.1.Electronically supplied services giving access to copyright-protected content

3.1.1.

Introduction and common methodological elements

3.1.2.

Impact analysis for on-line music (streaming and on-demand)

3.1.3.

Impact analysis for e-books

3.1.4.

Impact analysis for games/software

3.1.5.

Impact analysis for AV

3.2.Transport services

3.3.Financial services

3.4.Telecom Services

3.5.Health services

Annex – References

3.Analysis of feasibility and impacts of changes to the scope of the Regulation

3.1.Electronically supplied services giving access to copyright-protected content

3.1.1.Introduction and common methodological elements

The Regulation applies to electronically supplied services included in its general scope. The concept of electronically supplied services is defined in Article 2(1) of the Regulation and derives from the definition laid down in Implementing Regulation (EU) No 282/2011.

However, some non-audiovisual electronically supplied services are excluded from the main non-discrimination obligation laid down in Article 4 of the Regulation (i.e. the prohibition of different conditions on the basis of nationality, place of residence and place of establishment). The services concerned by this exclusion are those whose main feature is the access to and use of copyright protected works (including access to and/or downloading of e-books, software, including updates as well as streaming and downloading of music and of online video games). Moreover, electronically supplied audiovisual services are not included in the general scope of the Regulation, as they are excluded from the scope of the Services Directive in the first place.

Article 9(2) of the Regulation requires for the first evaluation of the Regulation to contain an assessment the scope of the Regulation. This assessment shall determine if the Regulation should also apply to electronically supplied services the main feature of which is the provision of access to and use of copyright protected works or other protected subject matter, including the selling of copyright protected works or protected subject matter in an intangible form, provided that the trader has the requisite rights for the relevant territories.

Electronically supplied content services that are currently either excluded partially (i.e. non-audiovisual) or fully (audiovisual) require clearing intellectual property rights for their provision. In addition, audiovisual media services are also subject to a specific regulatory framework in EU legislation. Taking all this into account, and in light of the different economic features of the services involved, this Staff Working Document provides a separate assessment for different kinds of electronically supplied content services in the sections that follow.

At the same time, the assessment is based on certain common elements contained in the Commission declaration attached to the Regulation. It therefore looks “at the increasing expectations of consumers, especially of those with no access to copyright-protected services”, at “the feasibility and potential costs and benefits arising from any changes to the scope of the Regulation”, “taking due account of the likely impacts any extension of the scope of the Regulation would have on consumers and business, and on the sectors concerned, across the European Union” as well as considering any extension “provided that the trader has the requisite rights for the relevant territories”. In the following sectoral analysis, these indications are reflected within a common analytical framework.

In particular, in the first place the assessment takes into account the current characteristics of the concerned sectors, and the possible changes prompted by any potential extension of the Regulation, including:

-the demand (“expectations”) of consumers for specific content;

-the current cross-border accessibility but also more generally availability of content within the Union, in order to verify if and to what extent consumers lack access to services offering copyright protected content;

-the possible impact of any extension on consumers, businesses and the sector as a whole, hence including effects on price and variety available to consumers, but also on revenue and administrative costs of providers/distributors, as well as on investment and licensing practices upstream in the value chain of content creation.

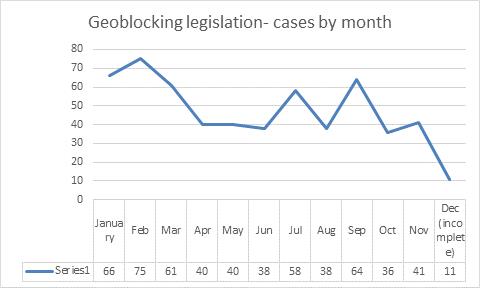

For their assessment, the Commission’s services relied on different sources of evidence. A 2019 Flash Eurobarometer provided a general overview of current demand for cross-border access to different content across all Member States, as well as perceived geo-blocking experience and broader interest to access content cross-border. The Study on the impacts of the extension of the scope of the Regulation to audiovisual and non-audiovisual services giving access to copyright protected content prepared by VVA/WIK/IPSOS/BRUEGEL (“VVA et al. (2020) Study” thereinafter) provided the following elements:

-a more in-depth analysis of demand (including through primary data from a consumer survey carried out in a sample of Member States, also looking at willingness to pay and switching drivers for cross-border content);

-an overview of main access obstacles (through mystery shopping on a sample of providers across the sampled Member States);

-an analysis of availability and prices of services across different Member States; an analysis of input from different stakeholders on possible effects of an extension of the Regulation;

-a basic quantitative model of static effects and some qualitative considerations on changes brought about by modification of the scope.

This study sought to complement earlier macro-assessments of the sectors at stake, with a more refined and articulated analysis of possible effects to the extent possible, on the basis of new primary and real market data sources. Overall, however, due to the complexity of the sectors and the multiplicity of effects and variables along the value chain, the model of the VVA et al (2020) Study is subject to some limitations and assumptions and could not therefore assess all possible implications of a potential extension. In particular, the quantitative analysis in the study could not realistically take into account the whole range of possible providers and/or business models available in all Member States, but rather focused on a limited range of providers (often with a pan-EU or multi-territorial reach) and a sample of countries representing different geographical areas in Europe, with potentially different demands for digital services. It also took into existing literature in the field and related research carried out by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre, as well as inputs and studies carried out by different stakeholders.

In addition, in order to identify the possible effects of the extension, the impact analysis had to rely on certain assumptions stemming from the overall intervention logic of the Regulation, including the review clause.

Firstly, Article 1(5) of the Regulation stipulates that “it shall not affect the rules applicable in the field of copyright and neighbouring rights, notably the rules provided for in Directive 2001/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council”. Article 4 mandates that no different general conditions of access, including net prices, for reasons related to customers’ nationality, place of residence or place of establishment can be applied, all other conditions being equal. This thus excludes the possibility to price-differentiate a given service and/or piece of content solely because of the customers’ nationality, place of residence or place of establishment, all other conditions of access to the service being the same for domestic and foreign (EU) consumers. In addition, the hypothesis identified in Article 4 of the Regulation concerns cases where cross-border delivery of goods or extension of the trader premises/network is not required. As a result, those non-electronically supplied content services whose cross-border provision would require to expand the network of the provider (such as by acquiring new frequencies, by signing transmission agreements for cable or IPTV services and/or distribution of set-top-boxes) are excluded. Finally, and in line with Article 9(2) of the Regulation, the analysis assumes that the provider, in order to be subject to the prohibition to discriminate (hence to refuse the service to) foreign customers, should hold “the requisite rights in the relevant territories”.

In this latter regard, it should be noted that EU law does not define, except in very specific situations, the criteria for determining the “relevant territories” for which the service providers need to obtain the requisite rights in order to make content available to customers. Further, CJEU case law has not yet provided an unequivocal criterion for the localisation of the copyright-relevant acts. Incidentally, in different judgements touching on this aspect, the Court has adopted different criteria, ranging from where the material act of broadcasting reception took place to the place where the public is targeted (regardless of the mere accessibility from other Member States). This leaves a margin of ambiguity as to the identification of the relevant territory where the copyright-relevant acts may take place, in particular as regards cross-border passive sales (i.e. services provided in response to unsolicited requests from customers located in other Member States).

From the point of view of competition law, absolute territorial exclusivity, which partitions national markets and eliminates competition between distributors, constitutes a violation of Article 101(1) TFEU.

In the pay-tv case

, the European Commission has taken issue with licensing terms that ruled out passive sales by prohibiting broadcasters from providing content via satellite or online streaming outside the specific Member State for which they obtained the licence. In the follow-up case law ( ‘Canal+ Ruling’), the General Court also confirmed that contractual clauses preventing a broadcaster from responding to unsolicited requests from consumers outside the licensed territory, as well as clauses requiring a film studio to prohibit broadcasters outside the territories for which a broadcaster has exclusive rights from responding to unsolicited requests from consumers residing in those territories, constituted restrictions of competition by object. Importantly, the court specifically outlawed contractual provisions that provide for an absolute territorial exclusivity. That judgment has been appealed by Canal+ before the European Court of Justice.

In view of the above, besides specific cases already regulated by EU copyright law, it is assumed that such legal uncertainty cannot be addressed within the intervention logic of the Regulation, as this may trigger much wider consequences in terms of copyright policy requiring an assessment ad hoc.

The sectoral analysis below therefore took into account two scenarios. Scenario 1 is based on existing industry licensing practices, which generally assume that service providers need to have the rights for the different countries where the content is made available, including those where “passive sales” are solicited (i.e. in the country where the service is actively provided, as well as in countries where unsolicited customers seeking access are located). Under this scenario, only the service providers having the rights in these different territories would be subject to the prohibition to discriminate laid down in the Regulation. Taking into account the current legal uncertainty, an alternative scenario has also been developed under a different assumption, based on the targeted audience of the service/activity (scenario 2). Under this scenario, service providers would not be required to hold the rights in the territories where the customers seeking access through passive sales are located. This alternative reading may, in certain circumstances, result in very different effects as a result of a potential extension of the Regulation. In this scenario, these effects may require an assessment within a wider copyright/media policy.

Depending on the business model of the service provider, the meaning of the trader “holding of requisite rights in the relevant territories”, when considered under scenario 1, can also have different implications. This concerns in particular the case of subscription-based business models (where the consumer acquires access to a catalogue within a given timeframe - increasingly relevant in particular in music and AV sectors) as opposed to transaction-based business models (where the customer acquires access to an individual content item). In both cases, indeed, the provider can hold the requisite rights for a number of items in its catalogue with different territorial scope. However in transaction-based business models, the compliance with copyright requirements only concerns the specific item at stake in the individual transaction, while in a subscription-based model, it involves a potentially very large number of items included in the overall catalogue to which the subscription normally gives unrestrained access.

The analysis should also take into account the extent to which the approach under scenario 1 may actually incentivise further fragmentation of the rights held for different territories across different traders/distributors and/or within groups. This way providers could indeed reduce as much as possible the extent of the obligation to provide cross-border access stemming from the Regulation, given that they would not hold the requisite rights in other countries.

These practical issues also underpin some of the considerations included in the VVA et al. (2020) Study supporting the assessment of the Commission services in the sectoral analysis. Since these issues also depend on the actual allocation of licenses among rightholders and distributors/traders and possible future adaptation strategies in view of the applicable regulatory choices, the full extent of their impact cannot be predicted in the models alone.

3.1.2.Impact analysis for on-line music (streaming and on-demand)

3.1.2.1.General description of sector

The VVA et al. (2020) Study highlights some clear trends of the music industry in Europe resulting from different sources, with an overall moderate growth of revenues in the past years pushed by the constant and steady growth of streaming services, replacing the decline of physical sales and reaching 58.9% of total sales in the European recorded music market.

On the basis of Statista 2019 data, overall digital music revenues reached 2.79 billion € and are predominantly based on music streaming (mostly based on paid or freemium subscriptions) as opposed to music downloads (mostly based on a transaction-based business model).

Figure 1 - Digital music revenues in the EU27_2020: market shares of the different business models

Source: VVA et al (2020) based on Statista data

Distribution of music involves different players and contractual arrangements. Typically speaking, the artists (i.e. authors and performers of music content, who may be represented by their agents) assign their copyrights to music publishers or publishing companies, based on a publishing contract. These publishers are entitled by the artists to license their content and to promote their content with distributors and broadcasters. The publishers then license the rights to distributors, such as (digital) service providers and (online) streaming platforms, based on license agreements, usually on a non-exclusive but territorial basis permitting distribution throughout the EU (often even permitting worldwide distribution). Publishers are often also in charge of assisting the artists in monitoring where their content is being used, collecting royalties and distributing these to the artists.

Frequently publishers pay Collective Management Organisations (CMOs) or other aggregators/collection organisations to perform (parts of) these monitoring, collection and disbursement tasks. The publishers share with the CMOs the metadata of the content created by the artists they represent; CMOs are then tasked with matching these metadata with the data from distributors, in order to calculate the exact royalty fees that distributors have to pay based on the number of times each individual song has been played. The CMOs then collect these royalty fees and distribute the money to authors, publishers and record labels. In certain cases, artists (e.g. the ones who have not transferred their rights to publishers) might deal directly with CMOs, cutting out the music publishers or publishing companies, although this is usually the case for less popular artists who may appear not profitable enough to be signed by music publishers or publishing companies. It is important to note that the role of CMOs typically differs for Anglo-American and continental repertoires.

Regarding the contractual arrangements, and specifically the licensing of rights, the recent Sector Inquiry by DG Competition shows that music is amongst the content categories for which rights are most often licensed to a large share of EU countries (38% of agreements scrutinised). This may be due to the scope of the commercial activities of certain digital content providers in these sectors. However, the feedback from the industry also pointed out that digital content providers (e.g. Spotify and Deezer), holding rights for a wide set of Member States, obtained these through national-specific licenses or licensing hubs rather than through a unique contract of pan-EU scope. This may suggest that the current geographical scope of licenses held by these distributors for music content in different Member States may be actually higher than the share of multi/pan-EU licensing agreements reported in the Sector Inquiry, as in their catalogue digital content providers bring together music licensed through national-specific licenses in different territories, often on the basis of contracts covering the entire repertoire of a given national right-holder (such as a CMO or aggregator).

3.1.2.2.Availability, Accessibility, Price differences

Several sources indicate that availability of music content in different Member States, i.e. the possibility to get access to a given catalogue item in a given Member State through one or several providers active in that Member State, is usually quite high for both transaction-based and subscription-based models.

Gomez-Herrera and Martens (2018) show that cross-border availability of music content on Apple iTunes was in the 73-82 per cent range in 2015. A similar study (Alaveras, Gomez and Martens, 2017) indicated that iTunes had reached close to 90% cross-catalogue overlap. These results pertain to transaction-based business models for music downloads.

With regard to the most fast-growing and popular subscription-based models, the VVA et al. (2020) Study provides an overview of available subscription services in different Member States, showing that most of the major music streaming services are available in all Member States (

Table 1

) and that no Member State is served by less than three streaming service providers. A more in-depth analysis of selected markets also shows that large pan-EU providers are also those with a more important market position in most markets, with the role of purely national providers usually less relevant (see

Table 2

).

Table 1 - Availability and prices of music streaming services across the EU

|

Country

|

Currency

|

Service

|

|

|

|

|

Tidal (Standard)

|

Apple Music (Basic)

|

Spotify (Premium)

|

Deezer (Premium)

|

YouTube (Premium)

|

SoundCloud Go+

|

Play Music (Premium)

|

TuneIn

|

Amazon Music (unlimited)

|

Napster

|

Avg. price for one streaming service in each country

|

|

AT

|

EUR

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

s. u.**

|

9.99

|

8.69

|

9.99

|

9.95

|

9.84

|

|

BE

|

EUR

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

8.69

|

9.99

|

s. u.**

|

9.85

|

|

BG

|

EUR

|

8.99

|

8.99

|

4.99

|

0.00

|

8.99

|

s. u.**

|

8.99

|

s. u.**

|

4.99

|

s. u.**

|

7.66

|

|

CY

|

EUR

|

5.17*

|

s. u.**

|

6.99

|

6.99

|

6.99

|

s. u.**

|

6.99

|

8.69

|

6.99

|

s. u.**

|

6.97

|

|

CZ

|

EUR

|

5.81*

|

5.81*

|

5.99

|

6.44*

|

5.81*

|

s. u.**

|

5.81*

|

s. u.**

|

5.99

|

s. u.**

|

5.95

|

|

DE

|

EUR

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

8.69

|

9.99

|

9.95

|

9.86

|

|

DK

|

EUR

|

12.87*

|

12.87*

|

12.87*

|

12.87*

|

12.87*

|

s. u.**

|

12.87*

|

s. u.**

|

s. u.**

|

12.87*

|

12.87

|

|

EE

|

EUR

|

6.99

|

6.99

|

6.99

|

6.99

|

6.99

|

s. u.**

|

6.99

|

8.69

|

6.99

|

s. u.**

|

7.20

|

|

EL

|

EUR

|

6.99

|

6.99

|

s. u.**

|

s. u.**

|

6.99

|

s. u.**

|

6.99

|

8.69

|

6.99

|

s. u.**

|

7.27

|

|

ES

|

EUR

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

8.69

|

9.99

|

9.95

|

9.86

|

|

FI

|

EUR

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.21*

|

s. u.**

|

9.21*

|

8.69

|

9.99

|

9.95

|

9.67

|

|

FR

|

EUR

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

8.69

|

9.99

|

9.95

|

9.86

|

|

HR

|

EUR

|

s. u.**

|

s. u.**

|

s. u.**

|

6.99

|

7.80

|

s. u.**

|

8.99

|

s. u.**

|

s. u.**

|

s. u.**

|

7.93

|

|

HU

|

EUR

|

4.50*

|

4.47*

|

4.99

|

4.50

|

4.47*

|

s. u.**

|

4.47*

|

s. u.**

|

4.99

|

s. u.**

|

4.63

|

|

IE

|

EUR

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

8.69

|

9.99

|

9.95

|

9.86

|

|

IT

|

EUR

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

8.69

|

9.99

|

9.95

|

9.86

|

|

LT

|

EUR

|

s. u.**

|

6.99

|

6.99

|

s. u.**

|

s. u.**

|

s. u.**

|

s. u.**

|

s. u.**

|

6.99

|

s. u.**

|

6.99

|

|

LU

|

EUR

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

s. u.**

|

9.99

|

8.69

|

9.99

|

9.95

|

9.84

|

|

LV

|

EUR

|

6.99

|

6.99

|

6.99

|

6.99

|

6.99

|

s. u.**

|

6.99

|

8.69

|

6.99

|

s. u.**

|

7.20

|

|

MT

|

EUR

|

s. u.**

|

6.99

|

6.99

|

s. u.**

|

s. u.**

|

s. u.**

|

s. u.**

|

s. u.**

|

6.99

|

s. u.**

|

6.99

|

|

NL

|

EUR

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

9.99

|

8.69

|

9.99

|

9.95

|

9.86

|

|

PL

|

EUR

|

s. u.**

|

4.60

|

4.60

|

4.60

|

4.60

|

s. u.**

|

4.60

|

0.00

|

3.99

|

s. u.**

|

4.50

|

|

PT

|

EUR

|

6.99

|

6.99

|

6.99

|

6.99

|

6.99

|

s. u.**

|

6.99

|

8.69

|

6.99

|

6.95

|

7.17

|

|

RO

|

EUR

|

4.20

|

4.20

|

4.99

|

4.99

|

4.62*

|

s. u.**

|

4.62*

|

s. u.**

|

s. u.**

|

s. u.**

|

4.60

|

|

SE

|

EUR

|

9.21*

|

9.21*

|

9.21*

|

9.21*

|

9.21*

|

s. u.**

|

9.21*

|

s. u.**

|

9.99

|

9.21*

|

9.30

|

|

SI

|

EUR

|

5.99

|

5.99

|

5.99

|

6.99

|

5.99

|

s. u.**

|

5.99

|

8.69

|

s. u.**

|

s. u.**

|

6.52

|

|

SK

|

EUR

|

5.99

|

5.99

|

5.99

|

5.99

|

5.99

|

s. u.**

|

5.49

|

8.69

|

5.99

|

s. u.**

|

6.27

|

|

UK

|

EUR

|

11.59*

|

11.59*

|

11.59*

|

11.59*

|

11.59*

|

11.59*

|

11.59*

|

9.09*

|

11.59*

|

11.60*

|

11.34*

|

|

Average price per service

|

8.42

|

8.29

|

8.19

|

8.42

|

8.31

|

10.19

|

8.33

|

8.71

|

8.18

|

10.01

|

|

Source: VVA et al (2020)

Table 2 - Shares of digital music purchases in selected MS

|

Italy

|

Market Positions

|

France

|

Market Positions

|

|

Spotify

|

51%

|

Deezer

|

41%

|

|

Amazon Music

|

36%

|

Spotify

|

34%

|

|

YouTube Music

|

28%

|

YouTube Music

|

25%

|

|

iTunes

|

24%

|

Amazon Music

|

22%

|

|

Google Play Store

|

22%

|

Apple Music

|

19%

|

|

Apple Music

|

17%

|

iTunes

|

18%

|

|

Deezer

|

8%

|

Google Play Store

|

14%

|

|

SoundCloud

|

7%

|

Napster

|

7%

|

|

Tidal

|

6%

|

SoundCloud

|

7%

|

|

Other

|

5%

|

Fnac Jukebox

|

5%

|

|

Napster

|

4%

|

Other

|

5%

|

|

Grooveshark

|

3%

|

Qobuz

|

2%

|

|

Rdio

|

2%

|

Tidal

|

1%

|

|

Germany

|

Market Positions

|

Poland

|

Market Positions

|

|

Amazon Music

|

52%

|

Spotify

|

54%

|

|

Spotify

|

37%

|

Empik

|

25%

|

|

iTunes

|

14%

|

Google Play Store

|

21%

|

|

Apple Music

|

13%

|

Tidal

|

21%

|

|

YouTube Music

|

13%

|

iTunes

|

18%

|

|

Google Play Store

|

11%

|

Apple Music

|

15%

|

|

Deezer

|

9%

|

Deezer

|

13%

|

|

Napster

|

5%

|

Amazon Music

|

10%

|

|

SoundCloud

|

5%

|

Other

|

4%

|

|

Other

|

3%

|

|

|

|

Juke

|

2%

|

|

|

|

Qobuz

|

2%

|

|

|

|

Tidal

|

2%

|

|

|

Source: Statista, based on a sample of n=2832 Digital music purchasers for France, n=3547 Digital music purchasers for Italy, n=4011 Digital music purchasers for Germany and n=1883 Digital music purchasers for Poland

As regards catalogue availability of streaming services, Alaveras, Gomez and Martens (2017) found very high overlap ratio for their sample concerning Spotify (approx. 96% overlap of catalogues across different national versions), confirming similar findings reported by the industry. The VVA et al (2020) Study also reports the range of catalogue size advertised by a large range of large, and smaller streaming service providers, many featuring catalogues well above several millions of songs available in different Member States, although no detailed data is available for the overlap of catalogue in different Member States where the providers are active.

Table 3 - Overview size of music catalogue for music streaming services

|

Service (alphabetically)

|

Advertised size of the catalogue (no. of songs in million)

|

|

8tracks

|

6.5

|

|

Anghami

|

30

|

|

Apple Music

|

> 45

|

|

Deezer

|

> 53

|

|

Earbits

|

0.1

|

|

Hoopla

|

5

|

|

iHeartRadio

|

30

|

|

Jango

|

30

|

|

Joox

|

Not available

|

|

Line Music

|

1.5

|

|

LiveXLive Powered by Slacker

|

13

|

|

MOOV

|

1.5

|

|

Music Choice

|

55

|

|

Music Unlimited (Amazon)

|

> 50

|

|

MyTuner Radio

|

30

|

|

Napster

|

> 40

|

|

NetEase cloud music

|

36

|

|

Pandora

|

30-40

|

|

Patari.pk

|

0,02

|

|

Play Music (Google)

|

> 40

|

|

Qobuz

|

40

|

|

radical.fm

|

25

|

|

Saavn

|

30

|

|

SiriusXM Essential / SiriusXM Premier

|

33

|

|

SoundCloud Go

|

> 135

|

|

Spotify

|

> 35

|

|

Stingray Music

|

Not available

|

|

Tidal

|

> 60

|

|

TuneIn

|

Not available

|

|

YouTube Music

|

30/Not available

|

Source: VVA et al (2020)

With regard to cross-border accessibility, i.e. the possibility to access services from another Member State, the mystery shopping exercise carried out in the context of the VVA et al (2020) Study reports that the main issue concerning cross-border access for these services appears to be the automatic change of applicable conditions, rather than fully fledged blockage of access. This could also explain the more limited consumers’ perception of geo-blocking practices, with music resulting in the sector with the lowest proportion of geo-blocking experienced by consumers (38% of those trying to access content cross-border, i.e. 9% of overall consumers).

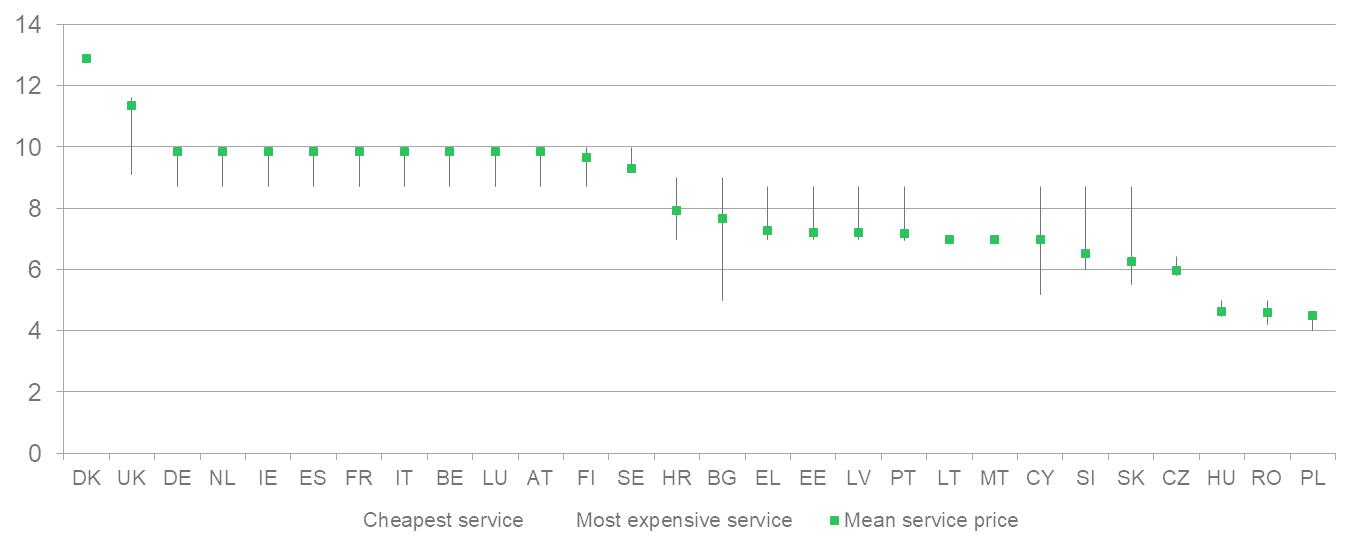

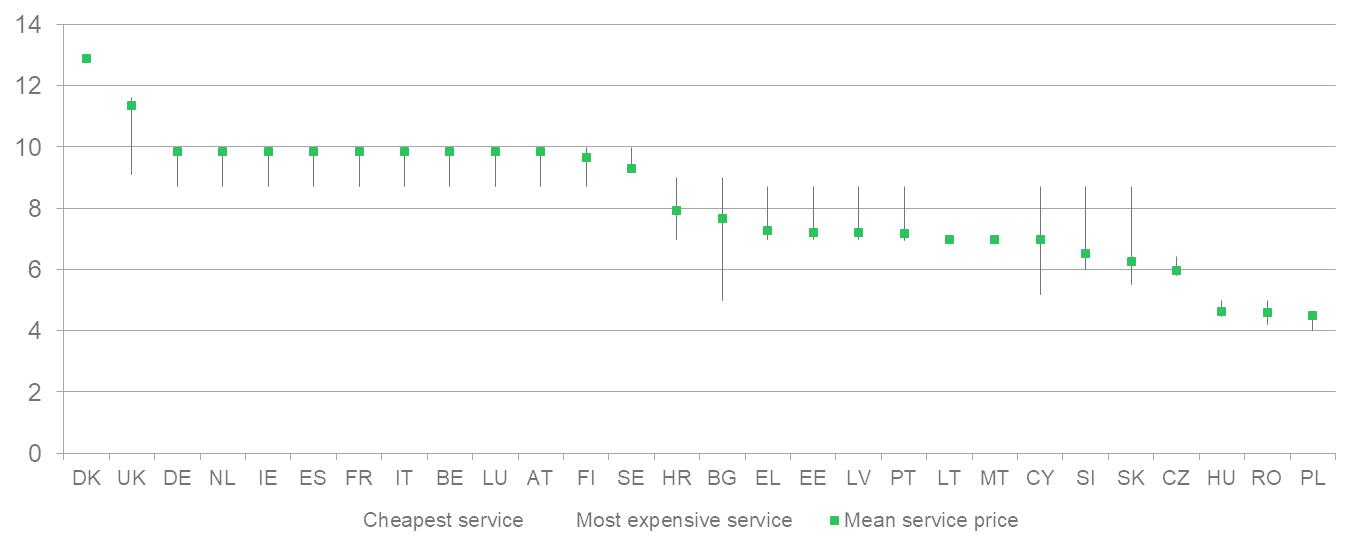

The importance of geo-blocking practices focusing on price differences, rather than on access as such, is indeed in line with findings from different sources as regards the price strategies of music providers (in particular subscription models). The analysis of prices reported in

Table 1

carried out in the VVA et al (2020) Study highlights how music providers follow a mostly territory-driven price differentiation strategy, with quite a common pattern showing consistent price differences between Western and Eastern European countries (see

Figure 2 - Monthly prices of music streaming services across Member States (EUR)

). This is in line with similar analysis carried out by JRC (Alaveras et al, 2017) and the findings of the industry-financed report from NERA (2019).

Figure 2 – Monthly prices of music streaming services across Member States (EUR)

Source: VVA et al (2020)

3.1.2.3.Demand of consumers

While domestic consumption remains predominant, music is among the most demanded cross-border among the content services analysed. In the Eurobarometer survey carried out in 2019, music is the second digital content service for which cross-border access has been sought (8% of internet users), with the largest increase compared to 2015 (+5pp). Similarly, the consumer survey carried out in the context of the VVA et al. (2020) Study shows that access to services not meant for users in their country is sought by 23% of consumers accessing content on-line in the countries surveyed - the highest proportion amongst all on-line content surveyed. Finally, potential interest to access music cross-border is also amongst the highest (29% of internet users that did not directly try access).

An analysis of switching behaviour and willingness to pay shows that language, while still important for 84% of users, is the least important factor for cross-border access, compared to price (92%) and content availability (95%). This is overall the lowest importance amongst the content services analysed. This finding is also consistent with results on price sensitivity vis-à-vis foreign services for these services resulting from the consumers’ survey. After live sport events and video games, music is the digital service with the highest proportion of consumers willing to switch to a service not meant for their country, even for a small price reduction and where the service provides no or limited national content/catalogue (more than 40%) (

Figure 3 - Consumers’ willingness to switch providers or service if it is not meant for users in their country of residence and offers no or limited local (national) content/catalogue

).

Figure 3 - Consumers’ willingness to switch providers or service if it is not meant for users in their country of residence and offers no or limited local (national) content/catalogue

Source: VVA et al (2020)

3.1.2.4.Possible effects

The VVA et al (2020) study suggests some possible quantitative impacts stemming from an extension of the Regulation to a sample of music services, with a focus on the dominant subscription-based business model and subject to the general limitations of the model highlighted therein.

In view of the general broad coverage of countries by different providers and overlap of catalogues, in particular for the most popular titles, the VVA et al (2020) Study finds that most cross-border switching following an extension of the Regulation would be driven by price rather than variety differences. Indeed, the consumer survey confirms that price differences, possibly resulting from a potential extension of the Geo-blocking Regulation, could significantly influence consumer behaviour in this sector. Although language accessibility has an impact, it is not as strong as in other sectors (e.g. audiovisual content excl. sport). In turn, local content availability appears to have a rather limited impact on consumers’ switching behaviour. In case the Regulation were to be extended to this sector, consumers’ reactions would be highly dependent on the potential changes in available price offers, as well as, to a lesser extent, changes in the language interface.

On the basis of the static model and the data gathered by the contractor, it is considered that migration towards existing cheaper versions of the same service could have a substantial impact on revenues for an average subscription across different services, amounting to a 27% average reduction (

Figure 4 - Price impact on revenues - selected services across MS

.

Figure 4 - Price impact on revenues - selected services across MS

Source: VVA et al (2020)

While such a reduction of average revenues per transaction could extend the customer base by approx. 3% (

Figure 5 - Price-impact on user base - selected services across MS

), the overall effect on revenues for providers in case of mass migration towards a cheaper version of the platform would in any case be significantly negative, with a potential 25% reduction of revenues for the selected sample of providers in the concerned Member States (

Figure 6 - Overall impact on revenues - selected services across MS

). While this revenue reduction could indeed benefit (some) consumers accessing cheaper services, the magnitude of the potential impact needs to take into account the likelihood of mitigation strategies adopted by providers. Indeed, the abovementioned results do not take into account this possible (and likely) price response, which could change significantly the overall effects.

Figure 5 - Price-impact on user base - selected services across MS

Source: VVA et al (2020)

Figure 6 - Overall impact on revenues - selected services across MS

Source: VVA et al (2020)

Given the potential significant static impact on revenues and imbalance of different markets’ weight, from a dynamic point of view, the VVA et al. (2020) Study considers it very likely and rational that the adoption of mitigation strategies by providers would consist in a price increase in the low-price Member States of up to 70% of the cheapest price (hence a margin for price differentiation could still remain in view of some inherent switching costs for part of consumers for which, for instance, language preferences are still important).

These latest findings are consistent with the indications from other studies, pointing out possible positive overall welfare effects of the current price differentiation in the music industry.

NERA (2019) suggests that on the basis of the imbalance of revenues and demand in “old” and “new” markets (mostly Western and Eastern markets), a uniform price would emerge in case of extension and it would likely be much closer to the (already largely uniform) price for the old markets.

Aguiar and Waldfogel (2014) are the first to report on consumer as well as producer welfare effects. They estimate welfare gains due to increase in variety of accessible individual titles for both groups from lifting geo-blocking restrictions in a transaction-based business model for music downloads at approx. 1,8% for consumers and 1,1% for producers. These welfare gains however relate only to an increase in the variety of music that becomes available after lifting geo-blocking (using iTunes music catalogue data). This study does not estimate the welfare effects due to price effects stemming from price arbitrage and possible industry reaction to that phenomenon (including versioning and differentiation of services available in different countries, which however could reduce the actual availability of content across different versions of the services).

Price effects of switching between music streaming services in different countries are analysed in a more recent paper (Waldfogel, 2018). This paper uses an empirical model of consumer demand for music streaming as a function of income and subscription prices – using available data on Spotify monthly prices and streaming volumes by country to create measures of the numbers of users. The author finds that country-specific pricing within Europe raises Spotify revenue in Europe by 1.1 percent and increases total consumer surplus in Europe by 0.3 percent, compared to uniform pricing. This consumer welfare gain comes from consumers in lower-income European countries who enjoy lower prices while consumers in higher-income countries pay more and consequently buy fewer subscriptions. If lifting geo-blocking restrictions were to lead to harmonisation of subscription prices across countries, lower-income consumers would face welfare losses.

These negative welfare effects reflect also structural gaps underlying the development of music markets across Europe, as the study A European Music Export Strategy (2019) suggests. The study defines the background, the scope, and proposes a set of measures for a European music export strategy. Following the analysis of the main characteristics of the music sector in the European Union, this report takes stock of the main obstacles, challenges and opportunities faced by European music when crossing borders. It highlights the importance of various structural factors (talent, knowledge, networks and investment capacity of particular artists and professionals and music companies, support structures, availability of training and capacity building and the existence of an export strategy to coordinate the activity between the sector organisations and the government) for the sector players within the EU to foster the circulation of music across national borders, especially in those Member States where the local sector ecosystem is smaller or less developed. This may also account for the finding that an increased availability of different music repertoires across national borders through digital services doesn’t necessarily increase the consumption of such music, and may warrant further tools and actions to support the development of promotion strategies. In this regard, as an implementing step to develop and promote European music export based on the conclusions of the report, the Commission has published an open call for tenders to generate knowledge and spread understanding about as well as explore new approaches for the export of European music by piloting some actions of the strategy. The results will inform possible future actions to implement the sectorial support for music and international dimension of the future Creative Europe Programme 2021-2027. Moreover, to implement the 2020 Preparatory action “Music Moves Europe: Boosting European music diversity and talent” (with a budget of €2.5 million), the Commission has published a call for proposals addressing the need to support the green, digital, just and resilient recovery and post-Covid-19-crisis development of the European music ecosystem to help it become more sustainable.

In view of the current large catalogue overlaps across countries and the large coverage by pan-EU/multi-territorial services, as well as the characteristics of licensing practices in the music sector, the VVA et al. (2020) Study does not forecast substantial differences in the static model between scenario 1 and scenario 2 (where an alternative reading of the criteria for the localisation of the copyright relevant act was envisaged).

Indeed demand changes remain mostly driven by price rather than the variety effect of switching catalogues, because they are already largely overlapping. On the other hand, in such a scenario, licensing practices in particular for smaller/start-ups/national providers could be affected, as the price for licenses of national repertoires (in particular the fixed component) could change in order to reflect the expanded potential audience.

The industry also indicates the risk that more tailored versions or purely national services of cheaper countries may have lower incentives to promote distribution of national repertoires, as access to music content from other countries would increase demand for “mainstream” content and could reduce interest in promotion of local content. A possible mitigation strategy based on increasing product differentiation (including for instance more targeted playlists and recommendations) could actually have opposite effects. While the VVA et al. (2020) study did not indicate specific elements that could substantiate these claims, it cannot be excluded that the prohibition to discriminate or refuse consumers from other Member States coupled with scenario 2 could have wider repercussions along the value chain, e.g.on the licensing practices, as well as on the transaction and administrative costs related to the cross-border enforcement of national licenses in case of passive sales. This effect was also highlighted in the CRA (2014) study with regard to the targeting approach defined therein, which may need to be investigated in more detail.

3.1.2.5.Findings

The main findings on the possible effects of an extension of the Regulation to the music sector are the following:

·There is increasing interest for cross-border access to music content by consumers (8% of internet users according to the EB477b, 23% of consumers seeking access to digital content across-borders in sampled Member States), although domestic consumption remains dominant.

·Subscription-based (including freemium and paid) business models, largely dominant in the digital music sector, are already widely available in the Union, with evidence showing a large share (above 90%) of overlapping catalogues across different versions of the same provider, as well as large catalogues (in the order of millions) available in different Member States through different providers.

·Geo-blocking practices in the sector are mainly meant to implement price differentiation strategies across different Member States, which follow a consistent pattern mirroring large price differences between higher income/demand and lower income/demand countries.

·The relatively low importance of language as a switching factor when it comes to music, together with relatively high price sensitivity vis-à-vis foreign services, (even if these feature less local content), supports the finding that price would be the main driver of consumer switching in case of extension of the scope of the Regulation.

·In view of the potential significant impact on revenues due to price-arbitrage across different countries (up to a 25% loss across the streaming services according to the VVA et al. (2020) Study), mitigation strategies based on increased price harmonisation across different countries appear likely, with possible increases of prices in low-demand countries (estimated by the VVA et al (2020) Study to reach 70% of the cheapest price). Other mitigation strategies leading to increasing differentiation of services (such as limitation of language interfaces, adaptation of playlists, more limited catalogues) across different countries could also limit switching behaviour towards cheaper versions. It is thus not excluded that some degree of price differentiation, and more limited price increases, could be maintained.

·The overall welfare effects of increasing price harmonisation are ambiguous and may well be negative, given that the possible decrease of prices in high-demand countries (and slight increase in consumption therein) may be more than compensated by likely increases of prices in low-demand countries. The extent of this effect will also depend on the effectiveness of other mitigation strategies based on increasing product differentiation.

3.1.3.Impact analysis for e-books

3.1.3.1.General description of sector

After a more pronounced dynamic in the early years of the last decade driven by widespread uptake of digital technologies, the evolution of the e-book market reported in the VVA et al (2020) Study suggests that the growth has been relatively modest afterwards. Turnover in 2016 was of EUR 827.9 million, not significantly higher compared to 2012, when turnover was EUR 788.2 million.

In addition to e-books, other e-publishing revenues also should be taken into account as similar copyright-protected content provided on-line. More recent data from different dataset in this regard would indicate a larger market size, reaching in 2019 the size of EUR 3.98 billion, of which approx. 53% is represented by e-books.

Subscription and transaction-based models are both present in the market and often offered by the same company, although the subscription based model appears less extensively present in all Member States, and seemingly less common than transaction based model, on which the VVA et al (2020) Study focused its analysis.

Table 4 - EU country availability of two selected e-book subscription services

|

Amazon Kindle Unlimited

|

Kobo Plus

|

|

France

|

Belgium

|

|

Germany

|

The Netherlands

|

|

Italy

|

|

|

Spain

|

|

|

United Kingdom

|

|

Source: Amazon, Kobo

Unlike music, where a number of large providers are present in different Member States with similar geographical extension and a balanced position in the market, a more in-depth analysis for a sample of countries carried out by VVA et al (2020) Study shows that in the e-books market the position of purely national providers stands alongside major pan-European/global providers, with Amazon usually representing by far the main market leader.

Table 5 - Shares of e-books purchases in selected MS

|

Italy

|

Market Positions

|

France

|

Market Positions

|

|

Amazon

|

78%

|

Amazon

|

61%

|

|

laFeltrinelli

|

21%

|

fnac

|

28%

|

|

Google Play Store

|

20%

|

Google Play Store

|

19%

|

|

Mondadori Store

|

18%

|

Cultura

|

19%

|

|

ibs.it

|

17%

|

Apple iBooks

|

17%

|

|

Apple iBooks

|

7%

|

Espace Culturel E. Leclerc

|

11%

|

|

Other

|

7%

|

Chapitre

|

11%

|

|

Libreria Rizzoli

|

6%

|

RakutenKobo

|

9%

|

|

RakutenKobo

|

6%

|

other

|

8%

|

|

BookRepublic

|

5%

|

Decitre

|

7%

|

|

Il giardino dei libri

|

5%

|

Feedbooks

|

6%

|

|

Ebooksitalia

|

4%

|

Bookeen

|

6%

|

|

Hoepli.it

|

3%

|

Nolim

|

5%

|

|

macro librarsi

|

3%

|

7switch

|

5%

|

|

Street Lib

|

2%

|

|

|

|

Germany

|

Market Positions

|

Poland

|

Market Positions

|

|

Amazon

|

68%

|

Empik

|

67%

|

|

Thalia

|

25%

|

Świat Książki

|

34%

|

|

Apple iBooks

|

15%

|

Tania Książka

|

23%

|

|

ebook.de

|

14%

|

Legimi

|

17%

|

|

Google Play Store

|

14%

|

Gandalf

|

14%

|

|

Bücher.de

|

13%

|

Publio

|

14%

|

|

Hugendubel

|

12%

|

Ebookpoint

|

12%

|

|

Weltbild

|

9%

|

Nexto

|

11%

|

|

Other

|

8%

|

Helion

|

10%

|

|

Beam

|

7%

|

Raudiovisualelo

|

10%

|

|

RakutenKobo

|

6%

|

Muza

|

9%

|

|

|

|

Woblink

|

9%

|

|

|

|

other

|

9%

|

|

|

|

Virtualo

|

8%

|

|

|

|

Bezdroża

|

7%

|

|

|

|

Muve

|

5%

|

Source: Statista, based on a sample of n=2038 E-publishing purchasers for France, n=3547 E-publishing purchasers for Italy, n=2521 E-publishing purchasers for Germany and n=1883 E-publishing purchasers for Poland.

Generally speaking, in the e-books sector publishing houses acquire world-wide rights for each specific language version from an author and then make commercial agreements with distributors/retailers granting non-exclusive licences on a territory-by-territory basis.

The contractual relationships between the publishing houses and online platforms to sell e-books is based on distribution agreements that allow the sale of e-books, usually provided on a non-exclusive but territorial basis. The global trend is that when these platforms first started to emerge in the 2000s, the price for the e-books was usually decided by the platform, under a wholesale pricing model where the retailer negotiates a wholesale price paid to the publisher per copy sold, but autonomously decides the final retail price. When Apple began to sell e-books, they developed a new contractual relationship with the publishing houses in order to compete with Amazon. Under this relationship, it was the publishing house that decided on the price, while the platform received a set percentage of the gross revenues (usually around 30%); this model is referred to as “agency pricing” as opposed to the “wholesale pricing” model. There are also instances where the authors are dealing directly with the e-book platforms (i.e. self-publishing authors) cutting out the publishing houses. However, authors may not be in a good position to do all their marketing and advertising themselves, which is why this option is usually taken up by less popular, non-mainstream authors. In many cases, these authors may end up in a more traditional relationship with publishers after the self-publication of their works has been used as a sort of market testing tool. From a quantitative point of view however, the Sector Enquiry carried out by DG Competition did not include the analysis of licensing arrangement for the e-books sector, and the VVA et al (2020) Study did not manage to fill this data gap, hence more detailed information on the extent of licensing agreement with publishing houses is not available at present.

3.1.3.2.Availability, Accessibility, Price differences

Unlike the music sector, where subscription-based models are clearly predominant, in the e-books sector the analysis of availability, accessibility and price differences carried out by VVA et al (2020) Study and earlier by JRC (2015) studies, focused on transaction-based distribution models. In order to establish the state of play of availability, accessibility and price differences across the Union, the analysis of the abovementioned studies focused on two pan-EU/global platforms that cover a large part of the markets across the Union. Moreover, the Apple store (unlike Amazon) gives access also to non-proprietary publishing format (such as EPUB and PDF), which can be displayed on different e-book readers. This focus makes it possible to analyse the catalogues’ availability and accessibility of selected distributors with large catalogues and geographical scope, and to assess to what extent European consumers can already have access to a large variety of content from at least one of these providers, and at which conditions. However, this overview does not give a full picture of current availability over all possible publishers (i.e. those not distributing through these platforms).

The JRC’s analysis from 2015 covered a sample of Top-100s best-selling titles in different EU Amazon e-books stores and found a very high overlap of catalogues available in different versions of the store (98,6% of the samples used) as well as full accessibility through the US store. The VVA et al (2020) Study, on the other hand, focused on the Apple Store for e-books, aiming at covering comprehensively three selected national catalogues (ranging from 1,6 to 2,2 million titles for the three relevant languages, although not all titles potentially available) as well as a large random (hence not necessarily biased towards most common titles) 1000 sample in all countries to measure accessibility. The analysis of “whole” catalogues overlap in the three selected countries (UK, PL, IT) would show that most e-books are available in both Italy and UK (>95%), while roughly 40% of each catalogue is missing in Poland. This could suggest a more limited “availability/overlap” of titles among the different catalogues compared to Amazon. When analysing a smaller random sample (n=1000) across different countries, however, it appears that availability reaches approx. 90% in most Member States, with another group of 4 countries (including PL) ranging between 75 and 59% availability and a clear outlier (HR) with very limited catalogue available (5%).

Table 6 - Number of available e-books out of a random sample of 1000 titles in 16 EU Member States

|

|

|

|

|

|

Austria

|

935

|

Italy

|

940

|

|

Belgium

|

931

|

Latvia

|

915

|

|

Bulgaria

|

597

|

Lithuania

|

911

|

|

Croatia

|

5

|

Luxemburg

|

933

|

|

Cyprus

|

926

|

Malta

|

931

|

|

Czech Republic

|

606

|

Netherlands

|

935

|

|

Denmark

|

785

|

Poland

|

606

|

|

Estonia

|

931

|

Portugal

|

926

|

Source: VVA et al (2020)

While this data cannot be conclusive about the effective availability within the Union, it can nevertheless be concluded that, taken together, the market leader Amazon and a similar large pan-EU distributor, such as Apple, make a large number of their titles (above 90%) available to the majority of EU citizens, although in the case of Apple the variety available in a number of countries (and HR in particular as an outlier) may be substantially lower. This data however does not allow the identification of the reason for the more limited availability in certain countries (whether for instance this is due to the extent of rights held).

With regard to accessibility, JRC (2015) found the lack of cross-border accessibility for purchase across different versions of the Amazon national shop, but full accessibility of titles through the US shop.

For other, smaller or national booksellers the table included in JRC (2017) – on the basis of EIBF data – can provide an overview for selected countries of cross-border activities of booksellers, even though an analysis of individual items in the catalogue accessible cross-border is not available. It shows that a majority of booksellers in DE, FR, ES, NL, do sell cross-border (hence are accessible), although the precise scope of countries covered, as well as the extent of catalogue, is usually not identified. Furthermore, the mystery shopping exercise carried out in the context of the VVA et al (2020) Study indicates a low level of geo-blocking restrictions, although this exercise also could not look into the accessibility of individual titles. However, the experience of consumers when accessing content cross-border indicates the existence of obstacles.

When it comes to price differences, the analysis of Amazon’s catalogue by JRC (2017) points out a non-negligible amount of titles are subject to price variation (approximately 2/3 of the sampled titles), although this could also be linked to VAT/exchange differences and/or compliance with fixed-price e-book national rules in countries where they are applicable. The price-variation analysis carried out by VVA et al (2020) Study for iTunes also finds a small but constant margin of variation in prices applied in different catalogues analysed comprehensively, with titles in the IT catalogue on average slightly more expensive than PL and UK. Overall, however, the average prices of titles do not tend to differ on average too much across different Member States, as the smaller sample checked across all MS shows. Besides, unlike music, no clear pricing patterns seem to emerge across countries.

Figure 7 - Price difference for a sample of 1,000 e-books across European Member States in 2019 (EU28)

Source: VVA et al (2020)

3.1.3.3.Demand of consumers

According to the 2019 Flash Eurobarometer, demand for cross-border access to e-books is amongst the lowest of all the digital content services analysed. Only 3% of internet users tried to get access to this content cross-border (similar to video games), and 12% of those that did not try would still be interested (slightly more than video games).

This should be read in conjunction with the relatively high importance of (local) content availability and language accessibility as compared to price as main drivers of switching behaviour. This is confirmed by the large share of consumers not willing to switch their service at any price discount with a foreign one without local content and language preferences (

Figure 8 - Consumers' willingness to switch providers or service if it is not meant to users in their country of residence and offers no or limited local (national) content/catalogue

). E-books indeed feature as the digital service with the highest proportion of consumers not willing to switch at any price (approx. 50%), after AV content.

Figure 8 - Consumers' willingness to switch providers or service if it is not meant to users in their country of residence and offers no or limited local (national) content/catalogue

Source: VVA et al (2020)

3.1.3.4.Possible effects

The VVA et al (2020) Study modelled the possible effects of an increased access to the iTunes store due to extension of the Regulation. In spite of the limited information available concerning the scope of licences held by publishers, it is often reported that publishers usually hold global, pan-EU, or at least regional licenses for their content. Within this context, therefore, the differences between scenario 1 (more conservative reading of the localisation criteria of copyright relevant act) and scenario 2 (alternative reading based on targeted territories) may be limited. The effects can, in any case, proportionally be reduced in scenario 1 depending on the percentage of titles for which publishers/distributors do not actually hold licenses for the entire EU. Scenario 2 therefore can also be considered as an upper bound of possible effects, also in case of Scenario 1, assuming that pan-EU licenses would be the standard in the sector.

Given that consumers can choose freely from e-book stores across all Member States, it is likely that price-sensitive consumers would tend to choose, for each item, the store where it is offered at the cheapest price. This price-driven optimisation would result in a reduction of the average transaction revenue for an e-book sold in iTunes of 4%. This is somewhat compensated by new users purchasing e-books for the first time as they find e-books matching their willingness-to-pay. The VVA et al (2020) Study estimates that 4% more users would enter the market as compared to the current situation. The combined price-driven effect is a reduction of 2% of the overall revenues across the eight Member States included in the study.

Figure 9 - Price impact on revenues for iTunes

Source: VVA et al (2020)

Figure 10: accessibility-impact on user base for iTunes

Source: VVA et al (2020)

Figure 11: overall impact on revenues for iTunes

Source: VVA et al (2020)

These possible effects mainly reflect price-effects, as the VVA et al (2020) Study assumes that the increase in accessible items, no matter its size, would likely have a limited effect on the average number of e-books read by a specific consumer (taking also into account the relative importance of more localised content in this sector). It is therefore concluded that these changes would probably not have a dramatic impact in the market as such, both in positive (for consumers facing lower prices) and negative (for industry) terms, and could possibly lead to some overall welfare gains estimated at around 3,8%. This estimate is based on the distributor analysed (a large pan-EU platform such as iTunes, for which the reallocation of consumers across different versions of the store does not entail additional effects beyond internal price arbitrage). These quantitative findings, however, do not provide indications as regards the impact on other players in the market.

Additional qualitative fieldwork in the VVA et al (2020) Study, however, reports potentially higher costs for smaller/national booksellers, in particular in comparison with the smaller turnover and margins stemming from e-books for these players. In these cases, e-books sales are marginal (compared to physical sales) and even more marginal are cross-border sales and demand in general. Increase of sales in the order of a few percentage points (as envisaged in the abovementioned quantitative model, also based on general demand data and drivers), may have very marginal effects on revenues, while triggering, in any case, additional compliance costs possibly exceeding the increase of sales.

Moreover, the extension of the Regulation could raise the issue of consistency with fixed-price regimes for e-books applicable in 6 Member States. Depending on possible policy options in case of extension, either the impact on these regimes would need to be verified in case of cross-border sales (if national fixed-price rules were considered not applicable to passive sales from other Member States) or another layer of administrative costs, in case of need to identify and comply with the applicable fixed-price regime, would be added (with corresponding more limited consumers’ gains in terms of cheaper access to titles abroad). In both cases, the effects would affect smaller players, as well as publishers, more than bigger platforms, as the former are the primary beneficiaries of these national regimes and/or the ones most affected by increase in administrative compliance costs. Ultimately, this may also have welfare implications for consumers in terms of local availability of and accessibility to a diversified cultural offer.

3.1.3.5.Findings

The main findings on the possible effects of an extension of the Regulation to the e-books sector are the following:

·Demand for cross-border access to e-books appears low, in particular compared to other content services.

·Transaction-based business models, largely dominant in the sector, show a mix of few pan-EU platforms, amongst which Amazon stands out as a prominent player with large market position in several national markets, besides many smaller national/regional booksellers/distributors.

·Following a hypothetical extension of Regulation, a potential increase of accessible items of individual catalogues across borders might be not negligible in particular for services featuring some catalogue’s limitations in selected countries (such as for the iTunes store analysed in the VVA et al (2020) Study). However, it is not clear whether this would actually increase the effective variety of individual titles available to consumers, in view of the already extensive availability of titles through different providers/versions of bookstores (including the global coverage of the catalogue accessible through the US Amazon store) and reported use of non-exclusive copyright licenses.

·Price variations reported for pan-EU platforms (Apple and Amazon) are, on average, limited.

·The relatively high importance of language, together with relatively lower price sensitivity vis-à-vis foreign services, more limited price differentials and non-exclusivity of catalogues (available through different providers already at national level), supports the finding that price and quantity effects could be limited in case of extension of the Regulation (for the pan-EU platform analysed in the VVA et al (2020) Study this would amount to a 4% decrease of prices and 2% increase of quantities sold, and overall negative revenues effect up to 2%). Depending on policy options as regards fixed-price legislation at national level, these effects could be even more limited.

·Possible increases in quantity sold may be even lower for smaller national booksellers with much smaller market shares and margin from sales of e-books, but higher relative operating costs for cross-border sales.

·Given the coexistence of very different market players (pan-EU players alongside national booksellers), the compliance costs triggered by cross-border sales could actually have very different effects on these market players.

·The general welfare effects of extension appear ambiguous and in any case limited. The possible impact of compliance costs in case of cross-border sales however may be more skewed against smaller/national booksellers.

3.1.4.Impact analysis for games/software

3.1.4.1.General description of sector

Under the broad definition of software and games, two main business models are adopted by developers, publishers and digital distributors to make content available across the EU. Either they directly sell via an online store on the website of the publisher / or on portals or digital distribution platforms which aggregate software and/or games (e.g. Softpedia or Softonic for desktop applications, Steam for PC games, Microsoft Store or PlayStation Store for console games, and Google Play or Apple AppStore for applications dedicated to smartphones and tablets).

In the software industry, there are different types of business models, with corresponding different revenues sources that characterise the relationships between the provider and the consumer:

·For free, as in the case of freeware or open source software;

·Upon an individual purchase which, in general, gives permission to authorise a certain number of devices on which the customer can install and use the software;

·Upon a monthly or annual fee (e.g. this is the case of software like antivirus tools and VPNs); and

·Upon a “freemium” solution (or in-app purchase): similar to the freemium business model mentioned above regarding music. Software developers often offer such software (either for desktop or for mobile) in a free version that has limited features and can be upgraded via future purchases.

In the gaming industry, which presents similar business models to the ones described above for software, digitalisation is the most important driver of growth. After smartphones became more widely available on the market, the gaming industry experienced another revolution, which completely changed the way people played games. Mobile technology has rapidly developed since and led to an explosion of mobile gaming, which, since 2017, has overtaken gaming revenues from PC and consoles, as demonstrated in the Statista 2019 data on revenues shares in the video games industry (

Figure 12

).

Figure 12 - Digital video games revenues in the EU27_2020: market shares of the different categories of contents

Source: VVA et al (2020) based on Statista data

If a game is available as an app for smartphones and tablets, the content is usually made available through app stores such as the Google Play Store or the App Store. Digital titles for PC are made available via online stores and digital distribution platforms such as Steam, Uplay, GOG.COM or Epic Games Store, set up originally by game companies (predominantly the biggest industry players) to distribute their own games, but also often allowing third-parties to sell their games for a percentage in revenues. Video games for consoles are available online through the stores run by the console manufacturers (e.g. PlayStation Store). Moreover, both free games and freemium versions can be played on social media. Traditional game companies (e.g. Electronic Arts with its “EA Access” or Microsoft with its XBOX Live and XBOX Game Pass) are also experimenting with subscription services, including offering access to older titles in their back catalogues. Several start-ups and more established firms active in the games sector also offer game subscription services, including services based on streaming technology, where pre-installation is no longer required to play games. In general, however, the transaction-based business models appear dominant.

With regard to the licensing practices, the key contractual relationship in these sectors exists between the developers and distributors. This agreement can be characterised in the same way as the agreement between artists and music publishers described above. In other words, the development of games/software is done in-house by the publisher (i.e. via internal staff of developers) or by external independent developers who then assign their copyrights to software/game publishers. There is no set formula on what rights the developer will grant which will vary depending on a number of factors, including which party provides the financing and game concept. In the majority of cases, licensing agreements are based on lump sum payments where the publishers buy all the rights from the developer. Publishers may also combine software and games from many developers in their portfolios. The publishers then make deals with online distributors on a non-exclusive and usually global basis.

Online software and digital games were not covered by DG Competition’s Sector Inquiry, so no quantitative information is available on the territorial scope of licensing agreements in this sector.

3.1.4.2.Availability, Accessibility, Price differences

The VVA et al. (2020) Study analysed the cross-border overlap of catalogues (indicating the availability of piece of content) through different platforms representative of the abovementioned different distribution models and segmentation of markets (in particular for video games, articulated according to different devices used). In this context the video games platforms Steam (for PC games) and PSN (for console games) have been analysed, as well as PlayStore app store for mobile apps (not limited to games) in general. Moreover, given the still dominant transaction-based business model and in view of the analysis of the impacts on demand and supply, the analysis of overlap of catalogues was primarily based on the relative importance of the items based on their ratings and/or the number of downloads. This adds to the earlier focus of JRC (2017) on the PSN platform specifically.