EUROPEAN COMMISSION

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Brussels, 31.5.2017

SWD(2017) 192 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

EX-POST EVALUATION

of

Directive 2004/52/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the interoperability of electronic road toll systems in the Community and of Commission Decision 2009/750/EC of 6 October 2009 on the definition of the European Electric Toll Service and its technical elements

FINAL REPORT

Accompanying the document

Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on the interoperability of electronic road toll systems and facilitating cross-border exchange of information on the failure to pay road fees in the Union (recast)

{COM(2017) 280 final}

{SWD(2017) 190 final}

{SWD(2017) 191 final}

{SWD(2017) 193 final}

Table of Contents

1.Introduction

2.Background to the initiative

2.1.Description of the initiative and its components

2.2.Baseline and the problems which the initiative was intended to solve

2.3.Objectives of the initiative and expected outcome

3.Evaluation questions

3.1.Effectiveness:

3.2.Efficiency:

3.3.Relevance:

3.4.European Added Value:

3.5.Coherence:

4.Method

4.1.Main tools12

4.1.1.Desk research12

4.1.2.Targeted questionnaires13

4.1.3.Workshop with representatives of standardisation bodies13

4.1.4.Open public consultation14

4.2.Limitations – robustness of findings14

5.Implementation state of play (results)15

5.1.State of implementation15

5.2.Current situation19

5.2.1.State of play – interoperability of electronic tolls19

5.2.2.State of play – costs and hassle linked to electronic tolls20

6.Answers to the evaluation questions23

6.1.Effectiveness23

6.1.1.Question 1: Have the provisions of the Directive and of the Decision led to the technical, contractual and procedural interoperability of electronic tolls? What has hindered/contributed to the achievement of this objective?23

6.1.2.Question 2: Have the standards imposed by legislation been sufficient to render e-tolling systems technologically compatible? If not, what is the reason for that?24

6.1.3.Question 3: Has the integration of on-board units with other devices such as e-call or the digital tachograph happened and if so did it allow for reduction of the costs? Is it technically feasible and does it have the potential to reduce costs?25

6.1.4.Question 4: To what extent did toll chargers comply with the requirement to use only three technologies? To what extent did it help achieve interoperability? Did it have any unintended effects?26

6.1.5.Question 5: Has the cost of setup and maintenance of electronic toll systems for toll chargers changed? Has the compliance cost and hassle for tolled road users changed? If so, can this be attributed to the effects of the evaluated legislation?27

6.1.6.Question 6: Have the provisions of the Decision led to the setup of the EETS? What has hindered/contributed to the achievement of this objective?29

6.1.7.Question 7: To what extent has the legal framework led to the improvement of the internal market for electronic fee collections? What factors have contributed to or hindered the achievement of this objective?32

6.1.8.Question 8: Has the legal framework led to any unintended effect (negative or positive)?33

6.2.Efficiency34

6.2.1.Question 9: What are the current costs (including opportunity costs of not using another suitable technology) and benefits of the approach limiting to three the number of technologies allowed to be used for electronic tolling? What will be their possible level in the short-to-medium term future? Are the answers different for different types of vehicles (heavy vs. light vehicles)?34

6.2.2.Question 10: Are the costs of the approach involving third party providers (EETS provider) adopted in the Decision lower than the benefits associated with the EU wide interoperability of the toll? Would the relation between the costs and benefits be better had an alternative approach been chosen (e.g. deployment of EETS through agreement between toll chargers, or as a public service obligation, etc.)?36

6.3.Relevance:38

6.3.1.Question 11: To what extent is interoperability of electronic tolls needed by the users? Is the answer different for different types of road users (in particular heavy goods vehicles vs. other users)? Is it likely to change over time?38

6.3.2.Question 12: To what extent the objective of having interoperability at all three different levels (technical, contractual and procedural) is equally needed by the road users? Would any of the three levels of interoperability be less relevant?40

6.3.3.Question 13: To what extent does the level of the costs (and hassle) caused by the lack of interoperability justify policy intervention to facilitate interoperability? How has the gradual increase in the length of tolled networks and number of electronic toll systems in the EU affected the relevance of the objectives of reducing costs for users and for toll chargers?40

6.3.4.Question 14: To what extent the coverage of the framework in terms of users and geographical scope is adequate to the needs of the sector? For instance, is interoperability needed for some or all road user types? Is it relevant to cover all toll domains in the EU? Could it cover less, e.g. main transit countries? Or should it cover more, e.g. Switzerland, EEA, Western Balkans, Turkey, Community of Independent States, etc.?41

6.3.1.Question 15: Is there still a need to ensure that the technologies and components provided for in national electronic fee collection systems be combined with other vehicle components?42

6.4.European added value43

6.4.1.Question 16: What was the EU added value of the EETS legislation?43

6.5.Coherence43

6.5.1.Question 17: To what extent the legal framework is coherent with the goals and provisions of existing and upcoming EU legislation? In particular, how does this initiative fit in the overall ITS legal framework?43

6.5.2.Question 18: To what extent are the provisions of the Directive and of the Decision coherent and consistent? Are there any incompatibilities or contradictions between individual provisions?45

7.Conclusions45

7.1.Effectiveness45

7.2.Efficiency46

7.3.Relevance47

7.4.European added value47

7.5.Coherence47

8.Annexes49

8.1.Annex 1: Glossary49

8.2.Annex 2: Intervention logic51

8.3.Annex 3: Synopsis report on back-to-back public consultation activities (covering both the ex post evaluation and the impact assessment)53

8.4.Annex 4: Bibliography66

8.5.Annex 5: Overview of tolling systems in the EU67

1.Introduction

The present ex post evaluation assesses the effects of the legislation on the European Electronic Toll Service (EETS) and its implementation over the period of 2004-2014.

The assessment covers Directive 2004/52/EC (EETS Directive) and Decision 2009/750/EC (EETS Decision) which lay down the conditions for the interoperability of electronic road toll systems in the European Union.

The ex post evaluation assesses the level and accuracy of implementation of the legal framework, the relevance of the objectives and the effectiveness and efficiency of the individual provisions in achieving stated objectives. It nominally covers the period since the adoption of the EETS Directive in 2004. However, it focuses on the period after the adoption of Decision 2009/750/EC, which defined the EETS and thus allowed its physical deployment.

An EETS is still not available to road users today. The analysis in this ex post evaluation will notably help understanding if the existing legal framework was ineffective and why the European Electronic Toll Service was not offered to heavy duty vehicles (HDV) by October 2012 and to other types of vehicles by October 2014, as provided under Directive 2004/52/EC.

The possible market and regulatory failures identified in this ex post evaluation could contribute to the problem definition in the impact assessment accompanying a revision of the EETS legislation.

2.Background to the initiative

2.1.Description of the initiative and its components

Directive 2004/52/EC mandated the setup of a European Electronic Toll Service (EETS), by which road users only subscribe to a single contract and use a single on-board unit (OBU) to pay electronic tolls all over the EU. The EETS was to be provided to heavy duty vehicles (HDV) by October 2012 and to cars by October 2014. To ensure that different tolling systems are technologically compatible and therefore ready to connect to this single tolling service, the Directive specified that all new electronic toll systems which require the installation of on-board equipment, brought into service after 1 January 2007, shall use one or more of the following three technologies: satellite positioning (GNSS) – recommended; mobile communications (GSM-GPRS); microwave technology (DSRC).

It was expected that, as a result of this technical convergence, standard equipment and back office solutions could be used in all the systems. This would have brought their unit costs down by a mechanism of economies of scale. Road users would not have to equip their vehicles with many scheme-specific on-board units (OBU) any more. It was also expected that the OBU would, with time, be integrated with other devices installed in the vehicle, such as the digital tachograph, to achieve further savings.

Decision 2009/750/EC defined the EETS and provided for the European Electronic Toll Service to be offered by market players on commercial terms. It split the actors of the EETS between four categories:

-Member States,

-Toll chargers (TC), i.e. managers of the roads for the use of which a toll is levied electronically,

-Clients, i.e. road users, and

-EETS providers, i.e. intermediaries between the clients and the toll chargers.

The Decision stated that 'EETS providers' should negotiate with all toll chargers in the EU the authorisation to provide the EETS on their road networks; then, they should offer the EETS to their clients.

The Decision specified in details the rights and obligation of all actors. Member States should have put in place the necessary regulatory framework to make the provision of EETS possible. They should have notably established independent 'conciliation bodies' to supervise the correct application of the rights and obligations of all partners. Toll chargers should have accepted on a non-discriminatory basis all interested EETS providers and their certified equipment; they had the right to request full co-operation of the EETS providers to guarantee the correct functioning of the service and eventually the correct collection of the toll. EETS providers should have provided their services in all electronic toll domains in the EU within 24 months from their official registration by their Member State of establishment and guarantee the quality and continuity of the EETS, in full co-operation with the toll chargers. Finally, EETS users should have ensured the correctness of all the data provided in the framework of the EETS and complied with the obligation to pay the toll; they had the right to sign contracts with the EETS provider of their choice and pay all their tolls through this channel.

2.2.Baseline and the problems which the initiative was intended to solve

At the time of the adoption of the EETS Directive (2004), nearly all motorway tolls (which existed on a larger scale in Portugal, Spain, France, Italy, Slovenia, Greece, Ireland and Poland) required vehicles to stop before a barrier, which would open after payment of the amount due. Special electronic tolling lanes were reserved for holders of on-board units; the latter allowed remote collection of the toll directly from the account of the user; the vehicle would need to slow down, but not stop, as the barrier would open automatically once the payment confirmed.

The first large scale free-flow system was deployed by Austria in 2004, followed by Germany in 2005. Both systems were only designed for lorries. The Austrian scheme used the DSRC technology (the same as used in the special lanes on toll plazas), while Germany opted for satellite positioning coupled with mobile communications.

Relatively early, concessionaires inside different EU countries co-operated to make their individual electronic tolling systems interoperable: in France, the Liber-T system for light vehicles was introduced in 2000 and is still operational today; similar agreements exist in Italy, Spain, Portugal, Ireland and elsewhere.

On the other hand, nearly no interoperability agreements were reached between partners located in different States. It was only made possible to use Swiss OBUs to pay tolls in Austria.

The first interoperability agreements (such as Liber-T) were negotiated bilaterally between toll chargers, but in the second half of the 2000's contracts involving third party toll service providers started to appear. As an example, the French single tolling system for lorries 'TIS-PL', introduced in 2007, is offered by as many as five toll service providers competing for customers and offering access to all tolled road infrastructures in France. Other examples of interoperability involving one or more third party(ies) exist notably in Spain, Portugal and Ireland.

Already in 2004, most electronic tolling systems which required the installation of equipment on-board the vehicle were using technologies compatible with the requirements of the EETS Directive. The only major exception to this rule was the Slovenian HGV toll, which used short range communication in a different frequency band than the DSRC standard. Infrared DSRC and passive RFID were also used in local systems (respectively Westerschelde tunnel in the Netherlands and Warnow tunnel in Rostock, Germany).

Before the adoption of the EETS framework there was no integration between tolling OBUs and other devices installed inside the vehicle, such as the digital tachograph or e-call. There were no examples of OBUs being used for other purposes than tolling. It is important to mention that at that time e-call was not deployed, and the digital tachograph did not contain GNSS and DSRC technologies, which could become the basis for integration with tolling OBUs.

The lack of interoperability agreements between partners in different countries meant that hauliers had to equip their vehicles with as many OBUs as States which their trucks were crossing. Indeed, a truck transporting goods from Berlin to Lisbon needed, just for this trip, 4 OBUs. The price of an OBU depends on the technology of tolling. Back in 2004, the manufacturing costs of a DSRC OBU was 20-30 EUR, and of a GNSS OBU – 180-300 EUR, but the price or deposit paid by the user would on many occasions be much higher. This was notably the case in Germany, where the OBU had to be fixed inside the vehicle by a specialist in a certified workshop.

Hauliers also had to sign separate tolling contracts for each country – often in the local languages of the toll chargers – and pay separate invoices in the currency of each toll charger. The latter however was not considered as an issue before two consecutive enlargements of 2004 and 2009, as at that time most electronic tolling systems were deployed in Eurozone countries). If we assume that a lorry engaged in international haulage had typically to visit or cross each year at least once Germany, Austria, Switzerland, France, Italy and Spain, then each haulier had to equip his/her vehicles with 6 OBUs each, sign as many local tolling contracts and pay dozens of invoices a year. A truck travelling across all Member States of today's EU (incl. Romania, Bulgaria and Croatia) would had had to be equipped with 11 OBUs (for Portugal, Spain, France, Italy, Germany, Austria, Slovenia, Croatia, Ireland, Greece and the Øresund bridge between Copenhagen and Malmö) and pay countless invoices per year. This would have been source of significant compliance costs and burden inside the companies.

Each electronic tolling system was being developed 'from scratch'. Toll chargers had to support very significant system development costs, which raised initial investment costs to extremely high levels. For example, investment in the development of the system amounted to EUR 750 millions in Austria (2004) and EUR 700 million in Germany (2005). Operation costs were consuming a significant share of the revenues: in Germany, initially they amounted to 18% of the revenues.

These issues have led to a situation where electronic fee collection did not operate in a cost efficient way and the proliferation of technologies and specifications was seen as a potential barrier to the smooth operation of the internal market.

2.3.Objectives of the initiative and expected outcome

The European legislator provided for a European Electronic Toll Service (EETS) to answer the abovementioned problems of road users and toll chargers.

The general objective of the EETS legislation was to improve the functioning of the internal market for electronic fee collection and to remove barriers that hinder the free movement of people and goods and compromise transport policy objectives by offering to road users the European Electronic Toll Service.

In more specific terms, the objectives were to:

(1)reduce for road users the hassle and direct costs of compliance with the requirement to pay tolls, i.e. of installing, updating and handling the on-board equipment and of managing tolling contracts in different Member States;

(2)reduce for toll chargers (i.e. road operators) the costs of setup, operation and administration of electronic fee collection systems.

Finally, in operational terms, the initiative aimed at:

(1)ensuring that the technologies and components provided for in national electronic fee collection systems can be combined with other vehicle components e.g. the digital tachograph and the e-call (emergency call device) or tracking and tracing devices of vehicles, to save money on redundant equipment;

and, more importantly,

(2)ensuring the interoperability of electronic tolls at technical, contractual and procedural levels. Interoperability can indeed be defined on three layers:

·first, a certain level of technical harmonisation of the equipment and systems used for electronic tolling must be achieved for the EETS to be feasible at reasonable costs;

·second, it must be possible for users from different countries to sign a contract with one EETS providers, and for the EETS provider to sign contracts with all toll chargers. For this to be achievable, contractual practices across the EU must be approximated;

·third, procedures for calculating and transmitting toll information need to be similar across the schemes, so that the EETS may be operated with similar features in all toll domains.

Figure 2

and

Figure 3

in Annex 2 present the intervention logic of the EETS legislation. In summary, the Directive and the Decision were expected to create the appropriate legal framework for the single European electronic toll service to be provided as a commercial service by third party providers playing the role of intermediaries between road users and the toll chargers in different toll domains.

The EETS was expected to facilitate the payment of road use charges for drivers when they go abroad. Users were also expected to accept more easily paying for the use of roads if the payment means were interoperable at European level.

It was also expected that this legal framework would provide the incentives (notably through standardisation work) for gradual technical and operational convergence of electronic tolling in the EU. This in turn would allow industrial economies of scale which would pull the costs of equipment and systems down.

Finally, the interoperability and harmonisation of equipment was expected to bring as a consequence the integration of OBUs with other standardised equipment in the vehicle such as the digital tachograph or e-call.

It should also be mentioned that an original idea of the legislation was to allow future generations of tolling systems to benefit from the high level of performance and of the flexibility of satellite-based tolling, through EGNOS and GALILEO, the European satellite positioning systems.

Had e-tolling become cheaper and interoperable as expected, this would have created the potential for:

·the increased replacement of manual toll collection at toll booths by fully electronic tolling, allowing to cope with the increase of traffic, which in turn would help reducing the problem of recurrent congestion at toll booths;

·easier and more wide-spread application of tolls on the wider network (not only motorways) and to all vehicles (incl. passenger cars), facilitating the generation of necessary funds for the completion and maintenance of the transport networks. This would allow true application of the 'user pays' and 'polluter pays' principles to road transport, and therefore the creation of a level playing field between transport undertakings in the road sector and between the transport modes.

3.Evaluation questions

3.1.Effectiveness:

(1)Have the provisions of the Directive and of the Decision led to the technical, contractual and procedural interoperability of electronic tolls? What has hindered/contributed to the achievement of this objective?

(2)Have the standards imposed by legislation been sufficient to render e-tolling systems technologically compatible? If not, what is the reason for that?

(3)Has the integration of on-board units with other devices such as e-call or the digital tachograph happened and if so did it allow for reduction of the costs? Is it technically feasible and does it make sense from an economic point of view?

(4)To what extent did toll chargers comply with the requirement to use only three technologies? To what extent did it help achieve interoperability? Has it lead to any unintended effects?

(5)Has the cost of setup and maintenance of electronic toll systems for toll chargers changed? Has the cost and administrative hassle for tolled road users changed? If so, can this be attributed to the effects of the evaluated legislation?

(6)Have the provisions of the Decision led to the setup of the EETS? What has hindered/contributed to the achievement of this objective?

(7)To what extent has the legal framework led to the improvement of the internal market for electronic fee collections? What factors have contributed to or hindered the achievement of this objective?

(8)Has the legal framework led to any unintended effect (negative or positive)?

3.2.Efficiency:

(1)What are the current costs (including opportunity costs of not using another suitable technology) and benefits of the approach limiting to three the number of technologies allowed to be used for electronic tolling? What will be their possible level in the short-to-medium term future? Are the answers different for different types of vehicles (heavy vs. light vehicles)?

(2)Are the costs of the approach involving third party providers (EETS provider)) adopted in the Decision lower than the benefits associated with the EU wide interoperability of the toll? Would the relation between the costs and benefits be better had an alternative approach been chosen (e.g. deployment of EETS through agreement between toll chargers, or as a public service obligation, etc.)?

3.3.Relevance:

(3)To what extent is interoperability of electronic tolls needed by the users? Is the answer different for different types of road users (in particular heavy goods vehicles vs. other users)? Is it likely to change over time?

(4)To what extent the objective of having interoperability at all three different levels (technical, contractual and procedural) is equally needed by the users? Would any of the three levels of interoperability be less relevant?

(5)To what extent does the level of the costs (and hassle) caused by the lack of interoperability justify policy intervention to facilitate interoperability? How has the gradual increase in the length of tolled networks and number of electronic toll systems in the EU affected the relevance of the objectives of reducing costs for users and for toll chargers?

(6)To what extent the coverage of the framework in terms of users and geographical scope is adequate to the needs of the sector? For instance, is interoperability needed for some or all road user types? Is it relevant to cover all toll domains in the EU? Could it cover less, e.g. main transit countries? Or should it cover more, e.g. Switzerland, EEA, Western Balkans, Turkey, Community of Independent States, etc.?

(7)Is there still a need to ensure that the technologies and components provided for in national electronic fee collection systems be combined with other vehicle components?

3.4.European Added Value:

(1)What was the EU added value of the EETS legislation?

3.5.Coherence:

(2)To what extent the legal framework is coherent with the goals and provisions of existing and upcoming EU legislation? In particular, how does this initiative fit in the overall ITS legal framework?

(3)To what extent are the provisions of the Directive and of the Decision coherent and consistent? Are there any incompatibilities or contradictions between individual provisions?

4.Method

Work on this ex post evaluation started in March 2015. A roadmap for this ex post evaluation was published on the Europa website on 14 September 2015.

The evaluation covers the 10-years periods starting from 20 May 2004, when the EETS Directive entered into force, until 31 December 2014. The assessment of the implementation of the Decision will cover the period from 13 October 2009, when the Decision was published, until 31 December 2014. However, where there was important evolution between the end of 2014 and the day of the publication of this staff working document (for example regarding the registration of EETS providers), this is also reflected in the text.

4.1.Main tools

A range of methodological tools to gather the necessary quantitative and qualitative evidence for the analysis of the key evaluation issues were used. These are outlined below and the methodology followed is further described in the following sections. Furthermore, the data gathered through these tools were checked for consistency and relevance. The quantitative data were formed into tables and analysed. Since the relevant data was obtained through various methods, triangulation was used to verify the findings.

4.1.1.Desk research

The literature review covered a number of relevant reports and statistics. The purpose of the desk research was to provide an overview of the available information relevant to the evaluation in the literature and to identify the gaps in available data. Sources were primarily selected by the Commission, and supplemented by suggestions from stakeholders.

An important data source of information for this evaluation is the REETS project. This regional interoperability project of 7 EU Member States and Switzerland, co-financed by the European Commission, published 12 reports, notably on the following topics:

–contractual framework and risk management

–certification

–key performance indicators

–back office interfaces

–return on experience

The papers report on the obstacles to EETS deployment and provide recommendations on how to solve them. Obstacles are linked to inappropriate provisions in the EU legal framework, the way they have been applied at national level, standardisation issues, etc.

It is important to mention that the REETS project gathered representatives of all the categories of stakeholders involved in EETS deployment, i.e. Member States, toll chargers and toll service providers. Reports are adopted by consensus, and thus reflect a balanced view of tpahe industry on the main obstacles to EETS deployment. REETS reports provided elements for the evaluation of the relevance, effectiveness and efficiency of the legislation in place.

Expert views presented in the study Expert Review of the EETS Legislative (September 2015) critically analysed the provisions of the EETS Directive and EETS Decision, indicating regulatory failures which contributed to the lack of success of EETS. The study was performed for the Commission by a consultancy with long experience with electronic tolling systems.

The study State of the Art of Electronic Tolling (October 2015) which was performed on behalf of the European Commission upon request from the European Parliament, assesses available tolling technologies and suggests solutions to identified problems. It focuses particularly on the costs and benefits offered by each electronic tolling solution. It thus provides data for evaluating the efficiency of the technological choices in the Directive, and helped answering the questions on relevance of the existing provisions.

A full list of the literature used is presented in Annex 4.

4.1.2.Targeted questionnaires

On 26 June 2015, separate targeted questionnaires were sent to the main groups of stakeholders in the field of EETS (i.e. Member States and toll chargers; toll service providers; road users, with a distinction between heavy and light vehicles; technology providers and commercial vehicle manufacturers) to collect missing information and data. A summary of the results of this and all other consultation activities are published under the following link:

http://ec.europa.eu/transport/modes/road/consultations/2016-eets_en

. A shorter review of the results is also presented in the synopsis report of all consultation activities in Annex 3.

Consulted European organisations were invited to disseminate the questionnaire among their members to maximise response rate. During the consultation period, which lasted till September 2015, the Commission received a total of 22 responses.

Targeted questionnaires focussed on information gaps identified during the desk research. Both the answer rate and the average quality of contributions were high, including quantified data.

|

Type of stakeholder

|

Approached

|

Responded

|

% response rate

|

|

Member States and Toll Chargers

|

33 individual + 3 associations

|

15

|

42%

|

|

Toll Service providers

|

1 + 1 association

|

4

|

200%

|

|

Road users (heavy duty transport)

|

2 associations

|

2

|

100%

|

|

Road users (light vehicles)

|

2 associations

|

1

|

50%

|

|

TOTAL (surveys)

|

42

|

22

|

52%

|

4.1.3.Workshop with representatives of standardisation bodies

To complete the knowledge on existing standardisation gaps, a full day seminar involving representatives of 3 notified bodies, the European Committee for Standardisation and two equipment manufacturers was organised in the framework of a meeting of the Notified Bodies Co-ordination Group (NoBos-CG) on 29 September 2015.

Important input on issues related to standards and technical certification was received as an outcome of the discussion.

The group will keep on working on the subject and is intending to present recommendations to the Commission.

4.1.4.Open public consultation

An open public consultation to validate the results of the ex post evaluation was organised back-to-back with the public consultation on the Impact Assessment. It was launched on 8th July 2016 and was open for responses until 2nd October (12 weeks). The objective of the consultation was to give the wide public an opportunity to express their opinion on the big societal choices related to the organisation of electronic toll collection in the EU. A total of 73 responses to the questionnaire were received. There were four main groups of respondents: industry associations (29 out of 73 or 40%), companies (21 out of 73 or 29%), citizens ( 11 out of 73 or 15%) and public authorities (9 out of 73 or 12%). There were many more respondents from EU-15 (over 50) than from EU-13 (10) or outside the EU (12). A summary of the results of this and all other consultation activities are published under the following link:

http://ec.europa.eu/transport/modes/road/consultations/2016-eets_en

. A shorter review of the results is also presented in the synopsis report of all consultation activities in Annex 3.

4.2.Limitations – robustness of findings

The community of electronic tolling professionals in the European Union is relatively small and well organised. It was therefore relatively easy to access the relevant stakeholders to collect from them information for the ex post evaluation. However, data on costs is considered commercially sensitive, and therefore difficult to obtain. This ex post evaluation therefore often had to base the analysis on expert estimations, price ranges or, in the best case scenario, averaged figures.

It was also difficult to obtain reliable data on the demand for- and use of interoperable services by the hauliers and other road users. The road transport market is highly fragmented with a lot of one-truck-one-man companies – according to official statistics, 80% of road freight transport companies in the EU employ less than 10 people. reliable consolidated data is therefore rare and hard to obtain. This makes it nearly impossible to estimate and monetise with sufficient level of precision the potential benefits of interoperability (or, to put it the other way, the current costs of the lack of interoperability). These can only be provided in the form of ranges and made dependent on the assumptions taken. The latter are explained each time figures dependent on assumptions are provided throughout the text. Again, even most conservative assumptions do not change the validity of the conclusions as to the need to further promote tolling interoperability.

5.Implementation state of play (results)

5.1.State of implementation

EETS legislation is not fully implemented in the EU Member States, as half of them failed to meet certain requirements set in the EETS legal framework according to the required timetable (as explained in more details below). As a result, the Commission started infringement procedures against eight Member States for non-respect of one or more of these obligations. Five Member States were able to fulfil their obligations in the course of the infringement procedures. It is expected that additional infringements will be opened as result of unsatisfactory exchange of information between the Commission and other Member States on the level of implementation of EETS in their respective countries.

The EETS Directive provided that Member States had to ensure that all electronic tolling systems requiring the installation of an on-board unit and brought into use after 1 January 2007 use one, or a combination of, three technologies: microwave communications, satellite positioning and mobile telecommunications (Art.2). This provision has been largely respected by the Member States. Systems using alternative technologies are rare and have typically been put in place before 2007 (cf. section 2.2 for the details).

The EETS Directive also requires Member State to ensure that the EETS is offered to the users according to a fixed schedule (by October 2012 for heavy duty vehicles and by October 2014 for light vehicles). Given the fact that to date there is no EETS in place, all Member States have failed to meet these obligations.

The EETS Decision put three detailed concrete obligations on the Member States to pave the way for the implementation of the EETS:

·to foresee a registration procedure for candidate EETS providers;

·to keep and make public a national electronic register of the EETS domains within their territory by July 2010. The register had to include 1) all the necessary information for EETS providers wanting to enter their markets and 2) data on EETS providers which were granted registration in a given Member State;

·to set up national conciliation bodies to facilitate mediation between toll chargers and EETS providers.

Half of the Member States (i.e. Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Luxemburg, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, UK) have not correctly and fully implemented these requirements. This, as explained in the beginning of this section, already led to infringement procedures against eight Member States. The most common infringement is the failure to publish complete registers of EETS domains, which creates insurmountable obstacles to the entry of EETS providers on the local markets. Most concerned Member States have not started preparations to publish the register of EETS domains before being recalled of this obligation by the Commission in the framework of the infringement procedure.

The EETS Directive lists in its Annex the technical, procedural and legal items required for the definition and deployment of the European Electronic Toll Service. The list includes notably the operational procedures for the service, its functional specifications, technical specifications of the equipment, transactional models, procedures for the verification of the technical performance of the equipment, parameters for vehicle classification, rules on protecting fundamental rights of the individuals, harmonising rules related to enforcement and conflict resolution procedures. Although these items have not been further defined in the subsequent Decision, Article 4 of the Directive clearly states that "the European Electronic Toll Service shall be based on [them]". 12 Member State administrations, Norway and Switzerland have been working in the framework of the so-called 'Stockholm Group' on the approximation of these elements; however, the results of this work have hardly been reflected in the implementation of the national systems. In particular:

·The operational procedures for the service are different, and sometimes incompatible between different schemes. One amongst many examples of such difference is the way DSRC OBUs must be attached to the windshield to enable effective reading by the roadside equipment. Depending on whether roadside antennas are installed above or parallel to the road, OBU antennas should – respectively – be in a close to vertical or close to parallel position.

·Functional specifications of the service are defined for each toll domain in abstraction of the key performance indicators imposed in other toll domains.

·Most schemes use established standards to define the technical specifications of the equipment. However, several of the existing standards allow for certain flexibility in the implementation. As an example, the standard for back-office interfaces (EN ISO 12855) allows toll chargers to request additional elements on top of those listed in the standard. Member States have used this flexibility, defining technical specifications of the equipment which are not always compatible between toll domains.

·The EETS legislation does not specify the standard transaction model to be used. Some toll chargers choose the "reseller model", where the toll service provider acts and invoices road users in his/her own name; other toll chargers privilege the "agency model", where the toll service provider is merely the agent of the toll charger – this has a number of negative consequences for the service provider, including the impossibility to issue a single invoice and, in some extreme cases, the obligation to have a banking licence.

·The procedures for the verification of the technical performance of the tolling equipment (OBUs, roadside equipment, interfaces, etc.) are not standardised. The cost of a full test cycle can range from 100,000 (e.g. average cost to test suitability for use in one concession in France) to 200,000 (e.g. cost of testing suitability for use in the single tolling system covering the whole territory of Belgium) EUR per toll domain. Typically, the toll service provider bears the largest part of these costs. The cycle must be repeated as many times as there are toll domains in Europe (more than 140 today). A few tests are done jointly for several toll domains (e.g. French concessionaires run a join test centre, which explains the lower cost per domain), but compatibility to certain domain-specific requirements and end-to-end tests must be checked individually.

·The division of vehicles into toll classes is different in each tolling scheme:

–Most toll domains in Europe classify vehicles according to their number of axles; however, the Belgian HGV tolling scheme introduced in 2016 classifies them according to the maximum permissible laden weight;

–Similarly, most HGV tolling schemes cover all vehicles above 3.5 tonnes of total permissible laden weight. In Germany, however, this limit is fixed at 7.5 tonnes (previously 12 tonnes);

–It is mandatory, under the provisions of Directive 1999/62/EC, to differentiate toll rates by the EURO emissions class of the lorry. However, toll domains cluster different EURO norms together (e.g. same toll for EURO norms 0-III); this clustering is different in each toll domain.

·The legislative framework on the protection of personal data is not the same across the EU; this influences the design of the schemes and the interfaces with potential EETS providers. In Germany, requirements of the legislation on data protection were reportedly one of the reasons for choosing a "thick" OBU, while 'thin' OBUs are a more natural solution for EETS providers. The requirements in terms of data storage and computing powers are less demanding in a thin OBU than in a thick OBU, as the thin OBU is no more than a communication interface, but it can potentially raise issues related to the protection of personal data, as information on the exact location of the vehicle is sent to the back office.

·Finally, most toll chargers have not specified, nor harmonised, the contractual arrangements which they want to apply to EETS providers in fields such as financial guarantee requirements, service remuneration, invoicing policy, etc. The publication of such information in the EETS registers is an obligation for the Member States under the provisions of Article 19 and Annex I of the Decision. In the rare cases when the information is published, there requirements are not consistent between toll domains.

All the above issues have been identified in the reports of the REETS project. The latter also provided recommendations on how relevant stakeholders should address these shortcomings. However, to the Commission's knowledge these recommendations have so far largely not been put in practice.

REETS project

In 2013-2015, the Commission co-financed a regional interoperability project REETS involving Member State administrations, toll chargers and toll service providers from 7 EU Member States (Poland, Germany, France, Austria, Spain, Italy, Denmark) and from Switzerland. The project aimed at facilitating deployment of interoperable toll services first among these countries, in which most of the EU transit traffic takes place. The project consisted of two phases. In an analytical phase, which ran from January till September 2014, the partners analysed the framework conditions for the possible deployment of interoperable services in the REETS region: contractual framework and risk management, rules on the certification processes, key performance indicators used in different toll domains, back office interface solutions, and possible ways to manage interoperability. The analytical phase identified problems – including those related to the existing EU legal framework – which delay the achievement of interoperability and which also risked jeopardising the success of the deployment phase. After the analytical phase, the project entered the deployment phase: from the project side, this phase mainly consisted of monitoring and reporting on the ongoing negotiations between service providers and toll chargers for the provision of interoperable tolling services. The deployment phase of the project nominally ended on 31 December 2015. Nevertheless, REETS partners decided to continue monitoring and co-ordinating interoperability negotiations even after the Commission finished co-financing the project. The new co-operation agreement is called the EETS Facilitation Platform (EFP).

Five of the national electronic tolling schemes are not fully EETS compliant because they were designed and now are operated by private partners chosen through public tendering processes before or right after the Directive or the Decision defining the EETS were adopted. This is the case of the Austrian (operational in 2004), German (operational in 2005 and developed before 2003) and Czech (operational since 2007) HGV tolling schemes; the Slovak and Polish HGV tolling schemes (deployed, respectively, in 2010 and 2011) were put in place right after the adoption of the Decision, and hence the tender for the operation of the system could not take its provisions fully into account. Article 5.1 of the EETS Decision requires toll chargers to "assess the problems [of non-compliance] and […] take remedial action in view to ensure EETS interoperability of the toll system". This has so far not been entirely done for all the above schemes except the Austrian one. In particular:

·In Germany, the toll charger is reluctant to open the market to EETS providers on non-discriminatory basis. The current contract with the operator of the system gives to the latter monopoly rights and changing the contract in course could imply for Germany the obligation to compensate the operator for the lost revenues. However, Germany has adapted the system to EETS from a technical point of view, by gradually adding CEN DSRC antennas to enforcement gantries, replacing or adding to the previously used infrared DSRC.

·In the Czech Republic, the DSRC antennas are not fully compatible with the CEN DSRC standard. The toll charger is also reluctant to open the market for the same reasons as evoked for Germany.

·In Poland, new entrants cannot access the market because the legislation has not yet been updated in line with the EETS Decision.

The French 'Écotaxe' HGV national tolling scheme, which was supposed to be deployed in 2013, was expected to be fully EETS-compliant. However, the project was suspended and abolished just before its launch by decision of the government following public demonstrations in different regions of France against the idea of introducing a toll for heavy goods vehicles. Also the Hungarian toll is potentially open to all toll service providers, even though so far only Hungarian players managed to access the scheme. The Belgian HGV toll, deployed in April 2016, initially raised some concerns among prospective EETS providers regarding its EETS readiness. The system has opened to EETS providers in extremis, with the EETS provider Axxès signing a contract for the provision of toll collection services on the day preceding the launch of the scheme. Other EETS providers have not managed to enter the Belgian market so far (state of play in January 2017).

In general, it can be said that Member States and toll chargers have so far – with few notable exceptions – given low interest and priority to the objective of cross-border interoperability of electronic tolling schemes. Concession holders in a few Member States (France, Ireland, Spain and Portugal) were the first to re-organise themselves along the EETS model. When the toll chargers are public administrations, the willingness to adapt to the requirements of EETS is generally lower.

To date six companies – AGES (DE), Axxès (FR), Brobizz (DK), Eurotoll (FR), Telepass (IT) and Total (FR) have been officially registered as EETS providers. However – mostly because of the hurdles described above – AGES has since stopped operations in the EETS market, while Brobizz, Eurotoll, Telepass and Total did not make significant progress in terms of market coverage compared to the situation before their registration (although all four are known to be in the process of testing their equipment and negotiating contracts in a few toll domains).

5.2.Current situation

5.2.1.State of play – interoperability of electronic tolls

(1)Light vehicles

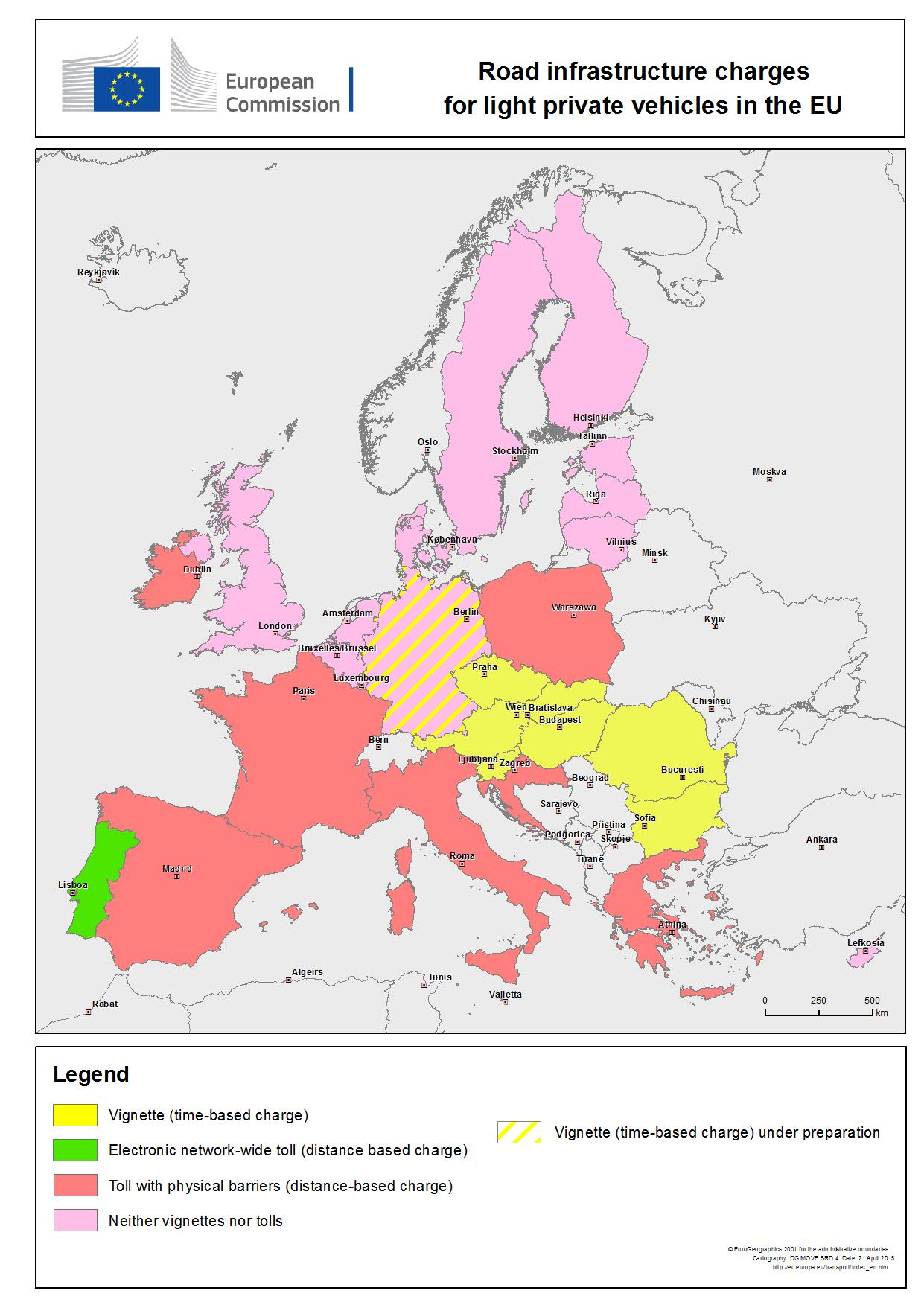

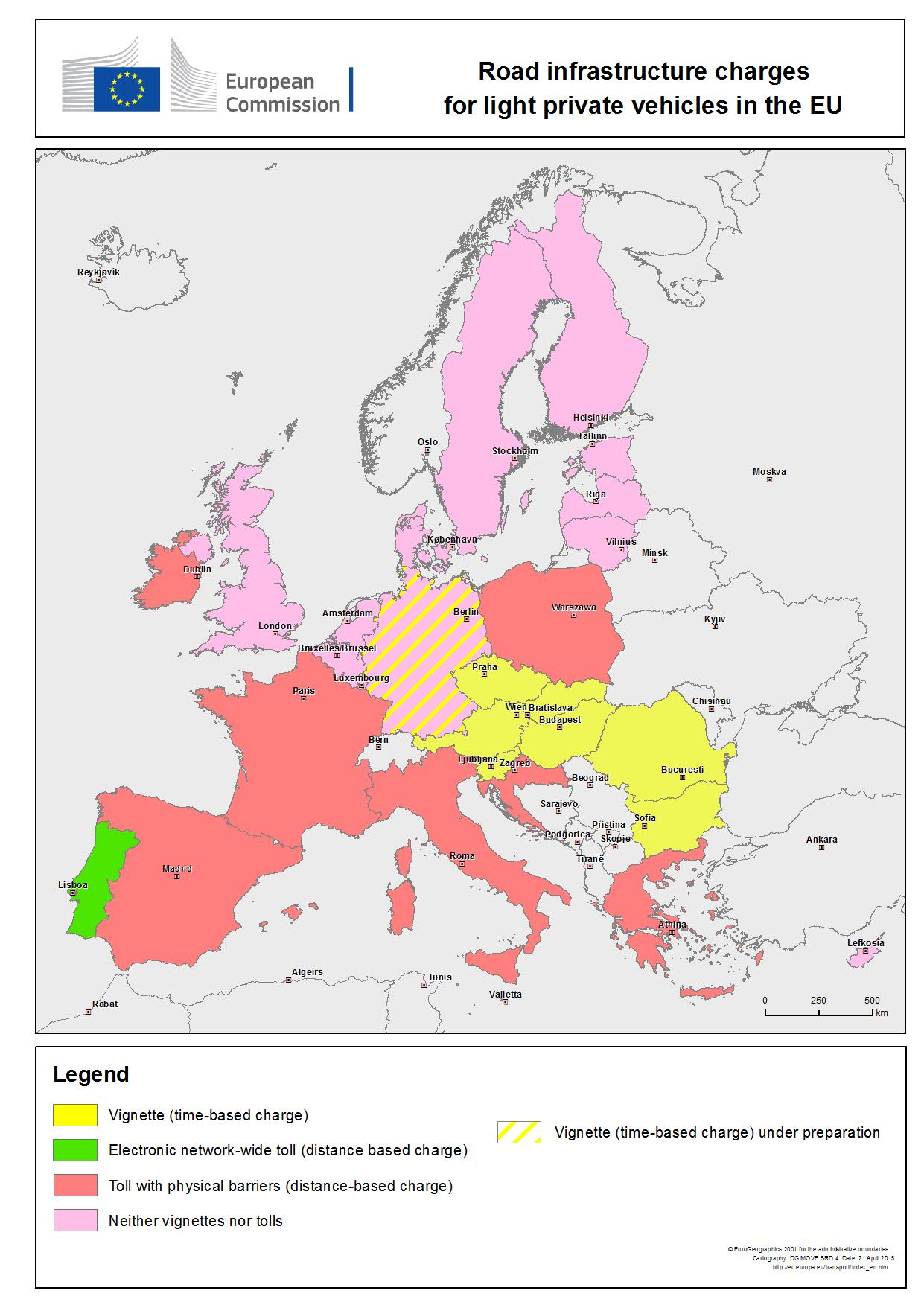

As illustrated in

Figure 4

in Annex 5, light vehicle (car, van and minibus) users are subject to electronic tolling on significant parts of the road networks in Croatia, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Poland, Portugal and Spain. In most of these tolling schemes, users can choose between electronic tolling requiring the presence on board of the vehicle of an OBU and manual payment of the toll (at the toll booths). Systems are largely interoperable inside each State (e.g. the Liber-T agreement allows users to pay tolls on all conceded motorways in France with one OBU and one invoice); cross-border agreements are typically signed between local toll chargers on two sides of the border – e.g. the French OBU can also be used in northern Spain.

(2)Heavy duty vehicles

Regarding heavy duty vehicles, electronic tolling with OBUs is (nearly) the only available payment method in eight Member States (Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia). In other countries with electronic tolling system (i.e. Croatia, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Slovenia and Spain) both manual and electronic tolling are available.

As in the case of light vehicles, systems are largely interoperable inside each State. The following cross-border interoperability agreements have also been reached:

·One-way technical interoperability agreements between Austria and Germany, and between Austria and Switzerland: Since its launch in 2004, the Austrian HGV tolling system accepted Swiss OBUs as valid toll declaration tool. In 2011, the same became possible with the German OBU. In both cases, interoperability works one way only, and is limited to technical aspects, i.e. the equipment used; separate contracts must still be signed by clients with each toll charger.

·Agreements between toll domains using the DSRC technology: Since 2013, it is possible to pay tolls with one OBU in Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Austria (EasyGo+ agreement). Initially developed on the basis of a pure agreement between toll chargers, the system is now evolving to allow independent toll service providers to offer their services in the area. Thanks to this evolution, providers already active in France, Spain, Portugal and Italy could start negotiating access to the service. If these negotiations are successfully concluded, it will soon be possible to travel on the toll roads of all seven countries – all using the DSRC technology – with one OBU issued by third party toll service providers and a single monthly invoice (if all toll chargers adopt the re-seller transaction model – cf. section 5.1 for details).

·Hungary: the electronic tolling system in Hungry is technically ready to connect to third party toll service providers. However, despite the system being operational since 2013, so far no toll service providers from abroad entered the market.

5.2.2.State of play – costs and hassle linked to electronic tolls

(1)Cost of setting up an electronic tolling system

Member States face significant costs for setting up an electronic tolling system. Moreover, from available data (see

Table 1

below), it appears that the initial investment needed for the toll charger to set up an electronic tolling system has not significantly changed over the evaluation period, averaging at over 650 million EUR. It seems also that there is no strong correlation between the technology chosen and the network coverage. The notable exception of a low price of the Hungarian system can be explained however by the choice of a completely different architecture compared to other systems (lower accuracy requirements, use of pre-existing equipment, minimum enforcement infrastructure, etc.). This special case will be further analysed and explained in the answers to specific evaluation questions.

|

System

|

Technology

|

Network coverage

|

Year

|

Cost (EUR)

|

|

Austria

|

DSRC

|

Motorways only

|

2004

|

750 million

|

|

Germany

|

GNSS

|

Motorways and certain federal roads

|

2005

|

700 million

|

|

Slovakia

|

GNSS

|

Motorways, first and second class roads

|

2010

|

800 million

|

|

France

|

GNSS

|

Certain motorways, national roads and certain regional roads

|

2013 (but later aborted)

|

650 million

|

|

Hungary

|

GNSS

|

Motorways and first class roads

|

2013

|

<100 million

|

Table 1: Initial investment to set up electronic tolling schemes in the EU

(2)Cost of operation

Due to data heterogeneity, it is difficult to establish clear patterns in the cost of operation of different systems, which seem to depend on many factors such as number of vehicles, intensity of traffic, technology, network coverage, etc. The only clear pattern emerging is the decrease of the costs of operation throughout the lifetime of the individual systems.

|

System

|

Technology

|

Network coverage

|

Initial operating costs (year)

|

Current operating costs (year)

|

|

France

|

GNSS

|

Certain motorways, national roads and certain regional roads

|

224 million EUR/year, 18% of tolls collected (2013)

|

N/A

|

|

Austria

|

DSRC

|

Motorways only

|

10-11% of tolls collected (2004)

|

4.5% (2015)

|

|

Germany

|

GNSS

|

Motorways and certain federal roads

|

18% of tolls collected (2006)

|

12% (2014)

|

|

Hungary

|

GNSS

|

Motorways and first class roads

|

Ca. 40 million EUR/year, 6.5% tolls collected (2013)

|

Same as initial operating costs

|

Table 2: Cost of operating different electronic tolling schemes in the EU

(3)Cost of equipment

The cost of on-board units, both in the DSRC and in the GNSS technology, fell by half over the evaluation period to respective averages of 8-15 EUR and 90-150 EUR. The cost of ANPR cameras, which are used for enforcement in all the systems, and as primary method of toll collection in few of them, and the cost of gantries over the roads (which would mainly depend on the cost of steel and on the cost of public works to ensure power supply and connection to data networks) have not evolved.

(4)Cost and hassle for users

For light vehicles, the cost and hassle remained at a low level, as confirmed by the contributions of motorists' associations to the targeted public consultation. Car drivers are usually satisfied with the manual tolling alternative, which exists for them on nearly all motorways where they are subject to tolls. Moreover, cars do not often go abroad, and therefore do not need cross-border interoperability as much as the lorries.

For lorries the situation looks different, as illustrated in

Table 3

. The number of nation-wide schemes has increased by 5 over the evaluation period. Thanks to cross-border interoperability agreements which were signed in the meantime, notably between Portugal, France and Spain, on the one hand, and between Austria and the Nordic countries (EasyGo+) on the other, the number of OBUs needed to travel unhindered across the EU increased only by two. However, the number of most expensive GNSS OBU went from 1 to 4, which explains the rise in the cost of OBUs needed. Also, the introduction of electronic tolling systems in non-Eurozone countries (Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Hungary) increased the hassle due to the treatment of invoices (and payments) in different currencies.

|

Year

|

Number of nationwide schemes + Oresund

|

Number of DSRC OBUs

|

Number of GNSS OBUs

|

Number of invoicing entities

|

Total cost of OBUs (EUR)

|

|

2004

|

11

|

9

|

1

|

11

|

162-285

|

|

2009

|

12

|

10

|

1

|

12

|

170-300

|

|

2016

|

16

|

9

|

4

|

13

|

432-735

|

Table 3: Number of schemes and on-board units needed to travel unhindered on all EU roads on international importance

More information on the evolution of costs for users and toll chargers is presented in the answer to evaluation question 5 (part 7.1.5).

6.Answers to the evaluation questions

6.1.Effectiveness

6.1.1.Question 1: Have the provisions of the Directive and of the Decision led to the technical, contractual and procedural interoperability of electronic tolls? What has hindered/contributed to the achievement of this objective?

Apart from national, and a handful of very limited regional interoperability agreements, the implementation of the provisions leading to technical, procedural or contractual interoperability has not been achieved in the EU.

6.1.1.1.Contractual interoperability

Most fuel cards can be used to pay tolls in different Member States. More than just easing the payment, fuel card providers (such as DKV, Shell, Total, OMV, Ressa, UTA, Trafineo) actually act as intermediaries between toll chargers and road users, taking care for the latter of administrative formalities such as registration in the toll charger's database, shipment of the on-board unit and financial brokering including financial guarantees. De facto, the customer's main counterpart is thus the fuel card provider and not the toll charger. These services come at a cost which can vary 1 and 4% of the tolls paid, depending on the array of services offered and the geographical coverage. Indeed, none of the fuel card providers offers his/her brokering services in all toll domains in the EU.

Similar services are offered by more profiled companies which specialise in toll payments, such as Eurotoll, LogPay or WAG.

The services of the fuel card/payment services providers therefore partly contribute to the objective of contractual interoperability (as they reduce the administrative burden for users linked to the need to deal with many toll chargers). However, users have a contractual relationship with each toll charger, and the services they receive from their fuel card providers are not available all across the EU. A higher level of contractual interoperability is offered by toll service providers such as Axxès, DKV, Eurotoll, Total, Telepass. Beyond obtaining payment services, like from fuel car providers, the clients of these toll service providers do not need to enter into contractual relations with the toll chargers, the toll service providers being their sole counterparts. The services of these companies are therefore the same as those of EETS providers (and Axxès, Eurotoll, Total and Telepass all recently became registered as EETS providers), but unlike the latter they are active in a handful of Member States only, namely France, Spain, Portugal, Belgium (only Axxès) and Italy (only Telepass).

6.1.1.2. Technical interoperability

The necessary basis for technical interoperability (i.e. the compatibility of equipment used by different parties in different toll domains) has been laid down by, on the one hand side, the provision of Art. 2.1 of the EETS Directive, which listed the technologies allowed to be used for electronic tolling in the EU and, on the other hand side, the standardisation work which delivered main standards for electronic tolling such as the EN 15509 on the DSRC communication between the OBU and the roadside equipment, the TS 16331 on the communication between the OBU and the back office of the toll service provider, or finally the EN 12855 on the interfaces between the back offices of the toll charger and of the toll service provider.

In practice, this technical interoperability is however limited. One on-board unit is compatible with the electronic tolling systems in Portugal, France, Spain and Italy. Another one can be used to pay tolls in Austria, Denmark, Sweden and Norway. Finally, a third type of OBU can be used both in Germany and in Austria. Elsewhere a different OBU is needed to pay tolls in each Member State.

6.1.1.3. Procedural interoperability

The EETS Directive identified in its Annex the procedural items essential for the definition and deployment of the European Electronic Toll Service. However, these items have not eventually been harmonised in the EETS Decision. As a result, the procedures adopted by different toll chargers in the different Member States were not always consistent with each other, as explained in details in section 5.1.

The Stockholm Group has been working to develop commonly acceptable solutions, but the results of this work have not always been enforced by the participating Member States. Also standards, developed by European standardisation bodies under mandated from the European Commission, proved so far not to be specific enough to ensure the harmonisation of procedures.

A certain level of procedural interoperability has been achieved inside regional interoperability agreements. Toll chargers participating in EasyGo+ (Austria, Norway, Denmark and Sweden) have developed, for instance, a common interface to exchange information with toll service providers. In France, a big part of the procedure of testing new on-board units is done only once for all the toll domains in the country. Discussions are also taking place inside the REETS/EFP region on the possible approximation of certain procedures in all participating countries. The possible results of these discussions in terms of greater procedural interoperability could materialise in the upcoming years. As an example, AETIS is discussing with the toll chargers partners in REETS the advantages for EETS of choosing the re-seller transaction model over the agency model.

6.1.2.Question 2: Have the standards imposed by legislation been sufficient to render e-tolling systems technologically compatible? If not, what is the reason for that?

To achieve technological compatibility in the world of electronic tolling, it is essential to harmonise two interfaces:

·The interface between the on-board unit (OBU) of the toll service provider and the roadside equipment (RSE) of the toll charger; and

·The interface between the back offices of the toll charger and of the toll service provider.

For the first interface, two profiled standard have been developed and their use is rendered mandatory by the EETS Directive. These are the standards on DSRC charging transactions: EN 15509, applicable across the EU, and ETSI ES 200674-1, which can be used on Italian territory.

Still in the framework of the first interface, a standard has been developed for real-time compliance check. This standard (ISO 12813) is essential in the framework of GNSS-based schemes, in which communication with roadside equipment is the main enforcement method. However, the standard for real-time compliance check has not been referred to in the EETS legislation.

The interface between the back offices of the toll charger and of the toll service provider has so far not been sufficiently harmonised. The existing standard ISO 12855 is a toolbox (i.e. a standard with many variants). It has been developed mainly with DSRC-based systems in mind, and does not meet the complex data exchange requirements in the framework of GNSS-based systems. So-called Interoperable Application Profiles (IAP) for the ISO 12855 standard (i.e. more precise standards, fitting more specific needs) have recently been adopted under the number CEN/TS 16986 and are reportedly referenced for future inclusion in the relations with EETS providers in the German tolling scheme, but not yet in any other existing system.

Specific test standards are also required for testing the compatibility of equipment and systems with the requirements of the abovementioned standards. Such test standards have been developed for the DSRC-related standards. These are respectively the test standard ISO 15876 for EN 15509, and test standard ISO 13143 for ISO 12813.

The same cannot be said about the interface between back offices. Test standards for the IAP for ISO 12855 are still in the process of being developed.

The clear and good definition of the DSRC standards undeniably contributed to the progress observed in Europe in terms of interoperability of DSRC-based electronic tolling systems (cf. section 5.2.1). On the other hand, the lack of as precise standards for GNSS-based schemes contributes to the delay in achieving interoperability with- and between GNSS-based systems.

6.1.3.Question 3: Has the integration of on-board units with other devices such as e-call or the digital tachograph happened and if so did it allow for reduction of the costs? Is it technically feasible and does it have the potential to reduce costs?

The objective to integrate on-board units with other legally required devices, such as e-call or the digital tachograph, has not been achieved. The implementation of this objective is impeded by the fact that on-board units for each tolling scheme are developed according to the proprietary requirements of each toll charger. Moreover, on-board units evolve all the time in line with changes to particular toll domains, while the specifications of the highly standardised tachograph or e-call remain stable as e.g. the tachograph must be protected against changes to prevent tampering. Therefore, the integration of OBUs with the digital tachograph or e-call could only be envisaged once OBUs are standardised across the EU, and even in this case would be difficult given the typical frequency of changes to the OBU software.

The question arises as to the actual existence of potential savings resulting from the integration of OBUs with the digital tachograph or e-call. The tachograph and e-call must be protected from malicious interventions to preserve their functions. OBUs, on the other hand, must receive constant software updates to reflect changes in the tolling environment. It would therefore seem that, for security reasons, full integration of the tachograph and e-call with the OBU would not be possible. It could be imagined, however, that the devices share some of the hardware, like the DSRC antenna in the upcoming smart tachograph. The cost of such parts is however extremely low, and the benefits from sharing their use would probably be lower than the costs of ensuring the integrity of the primary functions of the tachograph and e-call.

However, there are examples of integrating the OBU with devices present in the vehicle other than the tachograph or e-call: in Ireland, France or Italy, some of the on-board units can also be used to pay parking fees in non-public parking lots; The Hungarian tolling scheme allows for the use of commercial tracking and tracing equipment instead of dedicated on-board units to declare tolling data; the OBU of Axxès can also be used for fleet management.

Integration of OBUs with other devices is therefore possible as shown by the above examples. However, where commercial devices designed for other use (e.g. tracking and tracing devices in Hungary) are used instead of dedicated OBUs, additional efforts must be deployed for enforcement. Indeed, such devices can be turned off at any moment to evade the obligation to pay the toll.

6.1.4.Question 4: To what extent did toll chargers comply with the requirement to use only three technologies? To what extent did it help achieve interoperability? Did it have any unintended effects?

According to information available to the Commission and confirmed by Member States during the consultation for this evaluation, toll chargers have nearly totally (with exception to four cases, to the Commission's knowledge) complied with the requirement to choose among the three technologies provided for in the EETS Directive. For further details see a Section 2.2 and 5.1.

As confirmed notably by the (prospective) EETS providers gathered in the association AETIS and by an equipment manufacturer (Kapsch) during the targeted consultation, this high level of compliance helped achieve the existing interoperability among different DSRC-based tolling schemes – mostly at the national level, but also between some specific countries.

The unintended effects of the requirement to use only three technologies are discussed in the answer to question 8 (part 7.1.8).

6.1.5.Question 5: Has the cost of setup and maintenance of electronic toll systems for toll chargers changed? Has the compliance cost and hassle for tolled road users changed? If so, can this be attributed to the effects of the evaluated legislation?

(1)Cost for toll chargers

As mentioned in sections 5.2.2 (1) and (2), available evidence (c.f.

Table 1

) indicates that the investment needed to setup and launch a network-wide electronic tolling scheme has remained at a similar level over the evaluation period. Similarly, while for a single system operating costs tend to diminish with time, the level of these costs in the first year of operations seems to be the same for systems launched ten years ago and today.

The operating costs diminishing over time in different schemes indicate a high potential of cost reduction through a learning process. It can be safely assumed that this potential could also materialise, from the very beginning, in each new tolling schemes deployed, if there was sufficient exchange of best practices between toll chargers. The fact that setup and operating costs are as high in most recent schemes as they were in schemes introduced ten years ago shows that the EETS legislation failed to put in place effective incentives for toll chargers to exchange best practices and to build upon past experience.

One network-wide electronic tolling scheme stands out from the crowd. It is the Hungarian HGV tolling schemes, the deployment of which cost between 1/8 and 1/6 of the cost of comparable systems in other Member States, and the operation of which costs much less (the scarcity of data does not allow to estimate exactly by how much). The system is said to achieve lower performance levels (notably in terms of enforcement effectiveness) compared to other systems in the EU, nevertheless it meets the objectives of the Hungarian authorities in terms of toll collection and offers similar flexibility as elsewhere in the EU. The fact that Hungary remains the only Member State to date to have opted for such a 'cheap' solution shows that the EETS legislation did not put in place effective incentives for toll chargers to opt for the most economically efficient technical solutions for electronic tolling.

(2)Cost and hassle for tolled road users

According to sections 5.2.2 (3) and (4), the production cost of OBUs fell by half over the evaluation period, but this positive evolution was not entirely reflected in the prices paid by road users. In many schemes OBUs are rented to users against a deposit which typically exceeds the value of the equipment; in Poland, for example, the deposit for a DSRC OBU (manufacturing cost 8-15 EUR) is 30 EUR, and the user's account must be topped up with 30 EUR. These deposits and mandatory top ups of pre-paid accounts, when applied across different toll domains in the EU, amount to important sums which hauliers are obliged to block, and this negatively affects their cash flow.

The reduction in the manufacturing cost of OBUs can be attributed to different factors, depending on the specific category of equipment:

·GNSS on-board units were not in use in the EU before 2005 when the German HGV toll was deployed. At the time, it was a rising technology, and this fact explained the high costs of equipment. Today, the technology has reached a certain level of maturity – which explains the reduction of prices. It should also be acknowledged that GNSS is one of the technologies allowed by the EETS legislation and this fact could have also contributed to the decrease in prices.

·DSRC, on the other hand, was a relatively mature technology already back in 2004. The division of the price of OBUs by two can therefore be, at least partly, attributed to the impact of standardisation (EN 15509) mandated by the legislation. Moreover, the deployment of many new schemes, some of which cover not only heavy goods vehicles, but also private cars, greatly increased the number of OBUs in use, and therefore allowed further economies of scale in the production.

What can certainly be said is that the evaluated legislation failed to make sure that the falling cost of equipment is reflected in a proportionate reduction of the costs for final users.

Moreover, the number of electronic tolling schemes for lorries and their coverage in Europe has greatly increased over the evaluated period. Before 2004, electronic tolling was only an add-on to manual toll collection at toll plazas on concession motorways in Southern Europe, Ireland and Poland. Therefore, a lorry could drive across the EU without on-board units – the latter could only make paying tolls at barriers quicker and smoother. Nowadays, lorries must be equipped with a good dozen of OBUs to be able to drive unhindered on all tolled roads in the EU. Figure 1 illustrates an extreme scenario of a truck, which would travel to all EU Member States and therefore need most of the OBUs.

Figure 1: A lorry equipped with the different OBUs needed to drive unhindered on EU roads. Source: 4icom, Steer Davies Gleave, op. cit. footnote 17

For light vehicles, the situation today is similar to the one observed in 2004: electronic tolling is mainly an alternative to manual payment at toll plazas. In some electronic tolling schemes (Portugal, Dartford crossing in the UK, London, Stockholm and others), free-flow tolling has been put in place, but it is based on automatic number plate recognition, and therefore does not require equipping the car with an OBU.

Therefore, the costs and hassle for users (in particular lorries) linked to the obligation of paying electronic tolls increased over the evaluation period as new free flow schemes have been introduced. However, as explained in section 5.2.2(4) several regional interoperability agreements were signed in the meantime and contributed to some reduction of administrative burden. The explicit reference in the EETS Directive to the DSRC standard (EN 15509) facilitated the achievement of interoperability between microwave-based systems and thus the signature of the abovementioned regional agreements.

Initial interoperability agreements were signed by the toll chargers between themselves. This model renders difficult the achievement of interoperability between more than a few partners (e.g. the EasyGo interoperability agreement between Norway, Sweden and Denmark). Larger interoperability schemes require the participation of (a) third party(ies) to negotiate interoperability with each toll charger on a bilateral basis, avoiding the need for complicated multilateral negotiations. This model of interoperability was provided for by the EETS Decision, which defined the rights and obligations of EETS providers. It can therefore be said that larger interoperability projects (such as the one currently negotiated on the margins of the REETS project) were facilitated by the EETS legislation. The latter is expected to contribute to the reduction of the costs and hassle for road users.

6.1.6.Question 6: Have the provisions of the Decision led to the setup of the EETS? What has hindered/contributed to the achievement of this objective?

The legislation clearly failed to lead to the setup of a European Electronic Toll Service by the deadlines foreseen in the 'EETS Directive'. The first EETS provider (AGES GmbH) was registered in Germany in 2015, but since then abandoned its plans to expand in the EETS market. The second EETS provider (Axxès) is operating in 5 countries, but only in 4 (Belgium, France, Portugal and Spain) does it operate in all toll domains. The four remaining EETS providers cover even smaller networks.

A short analysis below considers the individual provisions of the Decision which can be held responsible for this failure:

·Article 3 lists the requirements to be fulfilled by companies seeking registration as EETS providers. The experience of AGES in the registration process in Germany gave valuable feedback on the appropriateness of these conditions. It appeared that the lack of precise definition of what constitutes "appropriate financial standing" (letter (d) of the Article) and "global risk management plan" resulted in the authorities asking guarantees, which are disproportionate at the stage of registration. In particular, AGES was asked to show a detailed business plan for EETS operation in a situation where the vast majority of toll chargers, including Germany, have not made public the contractual conditions for relations with EETS providers – making it impossible to foresee future revenues.