EUROPEAN COMMISSION

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Brussels, 12.11.2020

SWD(2020) 263 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

Individual reports and info sheets on implementation of EU Free Trade Agreements

Accompanying the document

REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS

on Implementation of EU Trade Agreements

1 January 2019 - 31 December 2019

{COM(2020) 705 final}

DATA USED FOR THE COMPILATION OF INDIVIDUAL REPORTS AND INFORMATION SHEETS

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE 15 POINTS ACTION PLAN ON TRADE AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

1.

Introduction

2.

Working together strand

3.

Enabling civil society to play their role in implementation

4.

Delivering

5.

Transparency

PART I:

ASIA

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON PREPARATIONS FOR THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE FREE TRADE AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE EU AND ITS MEMBER STATES AND SINGAPORE

1.

Introduction

2.

The agreements in summary

3.

Preparatory work for the entry into force

4.

early achievements and up-coming implementation activities

5.

Statistics

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE ECONOMIC PARTNERSHIP AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE EU AND JAPAN

1.

Introduction

2.

Main implementation issues

2.1

Main open issues, progress and follow-up

2.2

Progress in the implementation of trade and sustainable development provisions

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

Specific Areas of Importance

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7.

Statistics

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE EU-SOUTH KOREA FREE TRADE AGREEMENT

1.

Introduction

2.

Main implementation issues

2.1

Main open issues, progress and follow-up

2.2

Progress in the implementation of trade and sustainable development provisions

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

Activities subject to specific monitoring and Specific Areas of Importance

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7.

Statistics

PART II:

THE AMERICAS

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE COMPREHENSIVE ECONOMIC AND TRADE AGREEMENT (CETA) BETWEEN THE EU AND ITS MEMBER STATES AND CANADA

1.

Introduction

2.

Main implementation issues

2.1

Main open issues, progress and follow-up

2.2

Progress in the implementation of trade and sustainable development provisions

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

Specific Areas of Importance

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7.

Statistics

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE EU-COLOMBIA/ECUADOR/PERU TRADE AGREEMENT

1.

Introduction

2.

Main implementation issues

2.1

Main open issues, progress and follow-up

2.2

Progress in the implementation of trade and sustainable development provisions

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

Activities subject to specific monitoring and specific areas of importance

4.1

Banana Stabilisation Mechanism

4.2

Colombian anti-dumping duties on frozen fries

4.3

Ex post evaluation of the implementation of the Trade Agreement

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7.

Statistics

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF PART IV OF THE ASSOCIATION AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE EU AND ITS MEMBER STATES AND CENTRAL AMERICA

1.

Introduction

2.

Main implementation issues

2.1

Main open issues, progress and follow-up

2.2

Progress in the implementation of trade and sustainable development provisions

4.

Activities subject to specific monitoring

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7.

Statistics

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE TRADE PILLAR OF THE EU-CHILE ASSOCIATION AGREEMENT

1.

Introduction

2.

Main open implementation issues, progress and follow-up actions

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

Specific Areas of Importance

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7.

Statistics

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE TRADE PILLAR OF THE EU-MEXICO ASSOCIATION AGREEMENT

1.

Introduction

2.

Main open implementation issues , progress and follow-up actions

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

Specific Areas of Importance

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7.

Statistics

PART III: EU NEIGHBOURING COUNTRIES

PART III.I

SWITZERLAND, NORWAY AND TURKEY

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE EU-SWITZERLAND TRADE AGREEMENT

1.

Introduction

2.

Main open implementation issues, progess and follow-up actions

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

Specific Areas of Importance

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7.

Statistics

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE EU-NORWAY TRADE AGREEMENT

1.

Introduction

2.

Main open implementation issues, progess and follow-up actions

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

Specific Areas of Importance

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7.

Statistics

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE EU-TURKEY CUSTOMS UNION AND TRADE AGREEMENTS

1.

Introduction

2.

Main open implementation issues, progress and follow-up actions

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

Specific Areas of Importance

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7.

Statistics

PART III.2

TRADE AGREEMENTS WITH WESTERN BALKAN PARTNERS

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE TRADE PILLAR OF THE EU-ALBANIA STABILISATION AND ASSOCIATION AGREEMENT

1.

Introduction

2.

Main open implementation issues, progress and follow-up actions

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

Evolution of bilateral trade

4.1

Economic environment

4.2

Trade in goods

4.3

Trade in agricultural products

4.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

5.

Conclusions

6.

Statistics

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE TRADE PILLAR OF THE EU-BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA STABILISATION AND ASSOCIATION AGREEMENT

1.

Introduction

2.

Main open implementation issues, progress and follow-up actions

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

Specific Areas of Importance

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7.

Statistics

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE TRADE PILLAR OF THE STABILISATION AND ASSOCIATION AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE EU AND NORTH MACEDONIA

1.

Introduction

2.

Main implementation issues, progress and follow-up actions

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

Specific Areas of Importance

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7.

Statistics

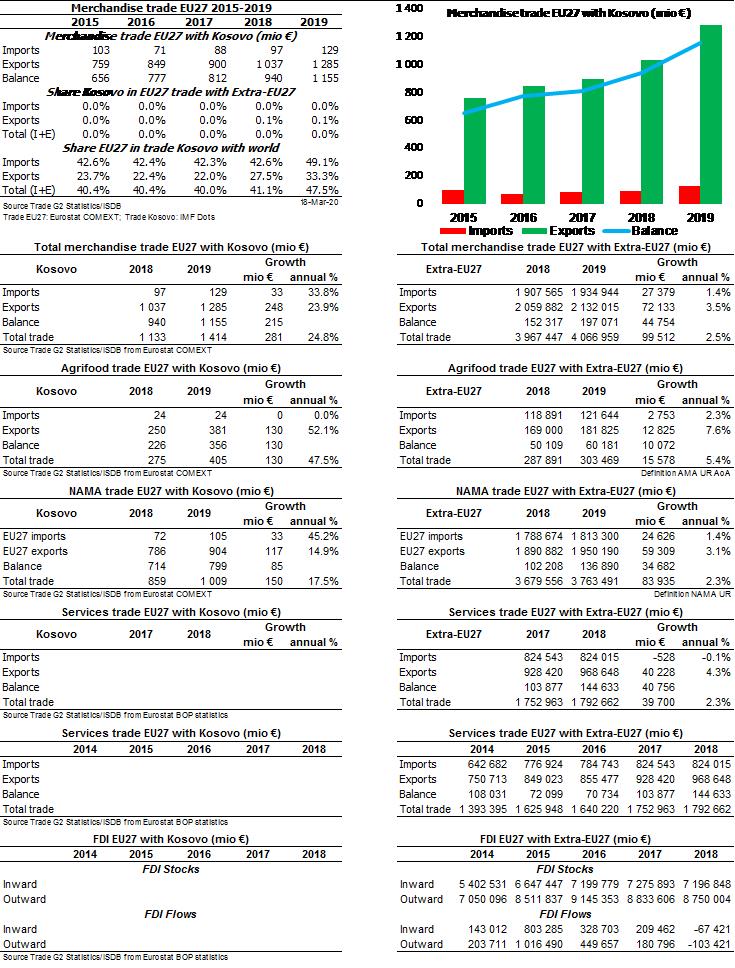

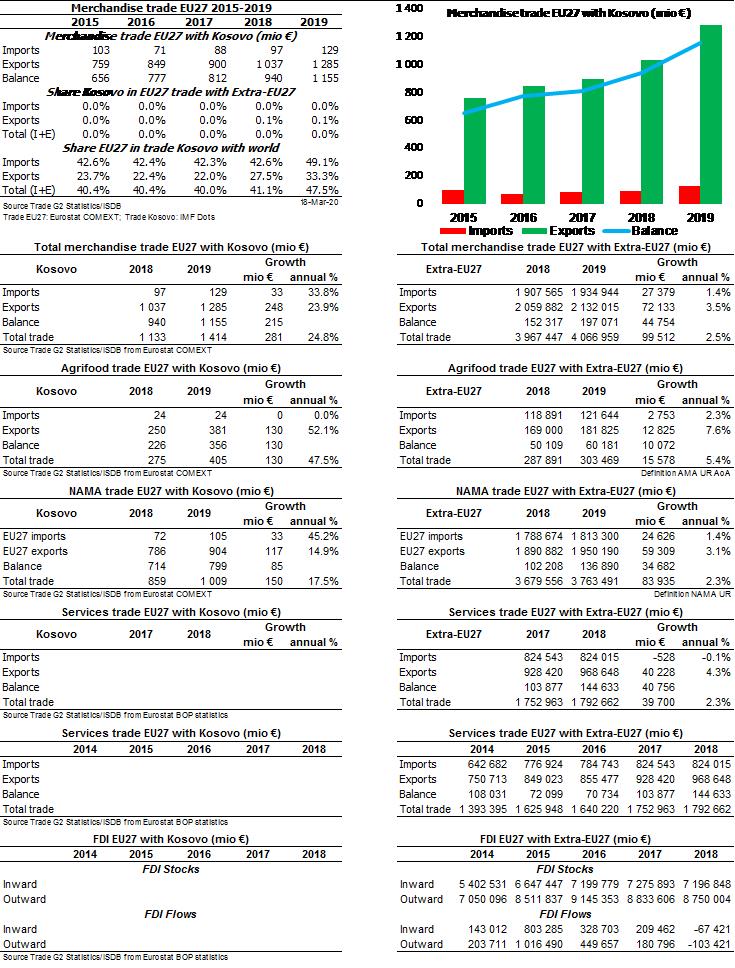

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE TRADE PILLAR OF THE EU-KOSOVO STABILISATION AND ASSOCIATION AGREEMENT

1.

Introduction

2.

Main open implementation issues, progress and follow-up actions

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

Evolution of bilateral trade

4.1

Economic environment

4.2

Trade in goods

4.3

Trade in agricultural products

4.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

5.

Conclusions

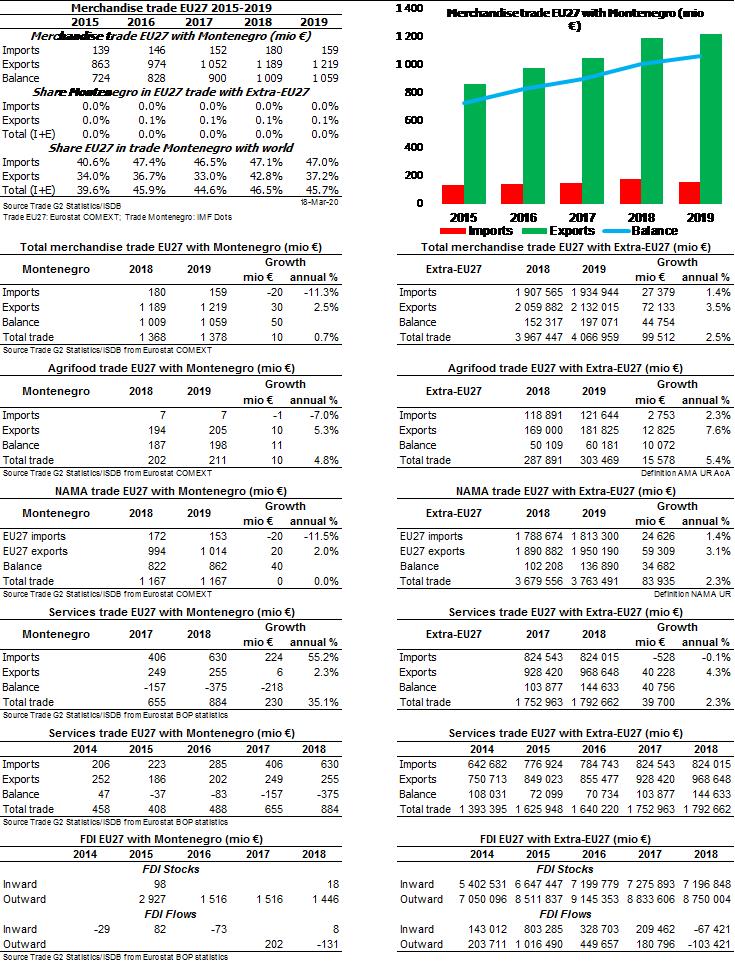

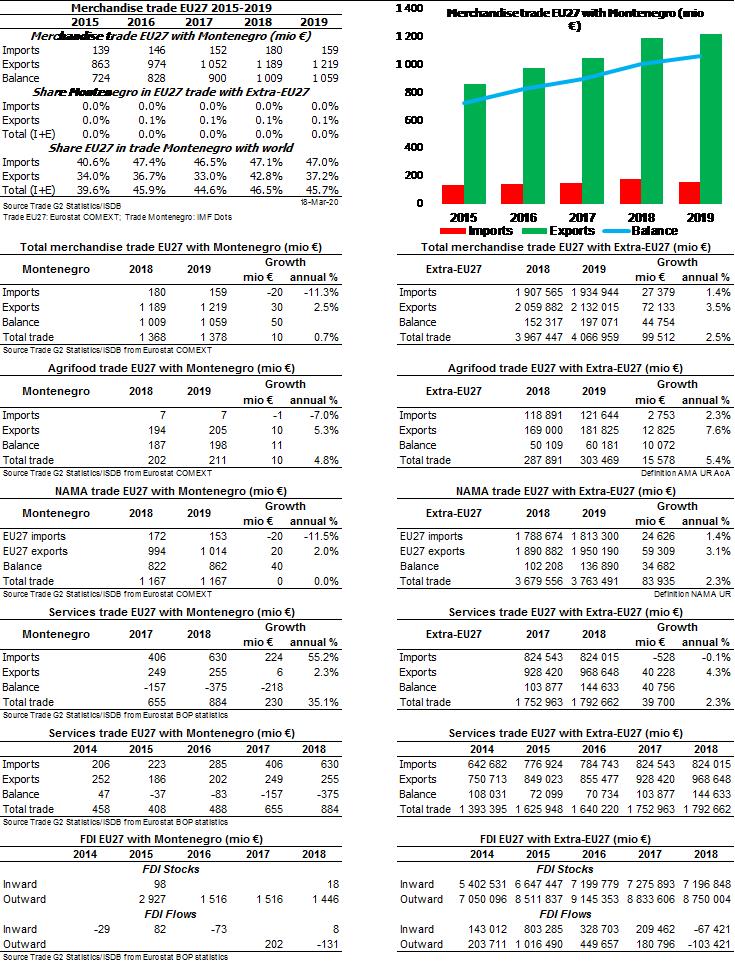

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON IMPLEMENTATION OF the trade pillar of the EU-MONTENEGRO STABILISATION AND ASSOCIATION AGREEMENT

1.

Introduction

2.

Main open implementation issues, progress and follow-up actions

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

Evolution of bilateral trade

4.1

Economic environment

4.2

Trade in goods

4.3

Trade in agricultural products

4.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

5.

Conclusions

6.

Statistics

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON IMPLEMENTATION OF the TRADE PILLAR OF THE EU-SERBIA STABILISATION AND ASSOCIATION AGREEMENT

1.

Introduction

2.

Main open implementation issues, progress and follow-up actions

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

Specific Areas of Importance

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7.

Statistics

PART III.3

DEEP AND COMPREHENSIVE FREE TRADE AREAS WITH

GEORGIA, MOLDOVA AND UKRAINE

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE DEEP AND COMPREHENSIVE FREE TRADE AREA (DCFTA) BETWEEN THE EU AND ITS MEMBER STATES AND GEORGIA

1.

Introduction

2.

Main implementation issues

2.1

Main open issues, progress and follow-up

2.2

Progress in the implementation of trade and sustainable development provisions

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

3.1 Joint decisions of the Association Bodies

3.2 Meetings of the Association Bodies

4.

Specific Areas of Importance

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7.

Statistics

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE DEEP AND COMPREHENSIVE FREE TRADE AREA (DCFTA) BETWEEN THE EU AND ITS MEMBER STATES AND MOLDOVA

1.

Introduction

2.

Main implementation issues

2.1

Main open issues, progress and follow-up

2.2

Progress in the implementation of trade and sustainable development provisions

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

Specific Areas of Importance

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7.

Statistics

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE DEEP AND COMPREHENSIVE FREE TRADE AREA (DCFTA) BETWEEN THE EU AND ITS MEMBER STATES AND UKRAINE

1.

Introduction

2.

Main implementation issues

2.1

Main open issues, progress and follow-up

2.2

Progress in the implementation of trade and sustainable development provisions

2.3

Legal enforcement – dispute settlement case

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

Specific Areas of Importance

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7.

Statistics

PART III.4

ASSOCIATION AGREEMENTS WITH

MEDITERRANEAN AND MIDDLE EAST PARTNERS

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE EU-ALGERIA ASSOCIATION AGREEMENT

1.

Introduction

2.

Main implementation issues

2.1

Main open issues, progress and follow-up

2.2

Legal enforcement – dispute settlement case

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

Specific areas of importance

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

6.

Conclusions

7.

Statistics

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE EU-EGYPT ASSOCIATION AGREEMENT

1.

Introduction

2.

Main open implementation issues, progress and follow-up actions

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

Specific Areas of Importance

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7.

Statistics

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE EU-ISRAEL ASSOCIATION AGREEMENT

1.

Introduction

2.

Main open implementation issues, progress and follow-up actions

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

Specific Areas of Importance

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7

Statistics

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE EU-JORDAN ASSOCIATION AGREEMENT

1.

Introduction

2.

Main open implementation issues, progress and follow-up actions

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

Specific Areas of Importance

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7

Statistics

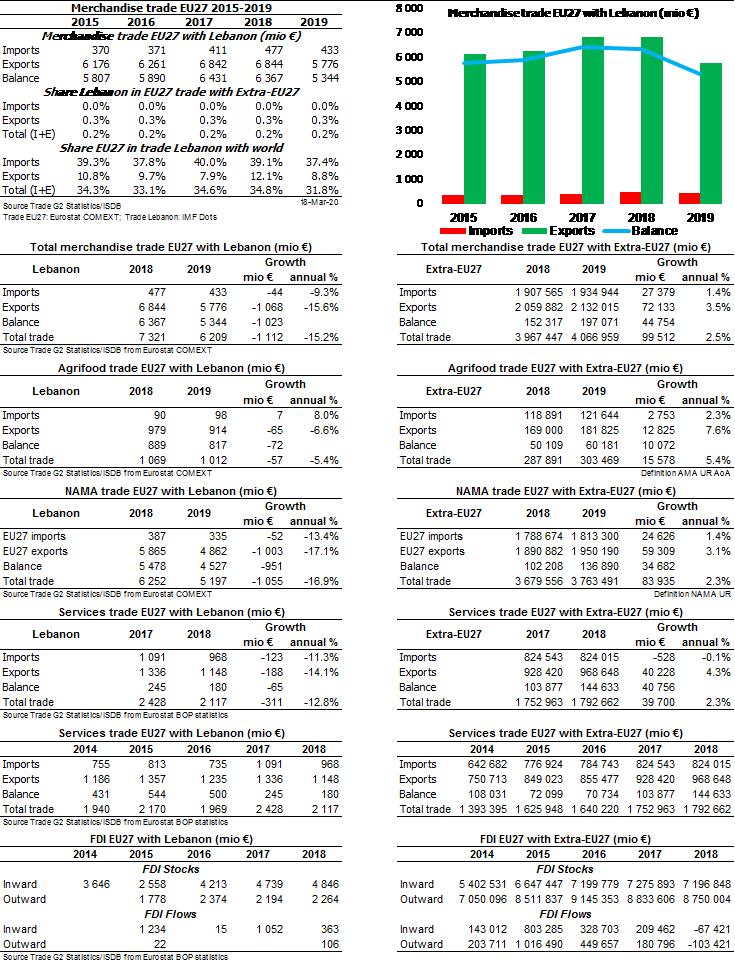

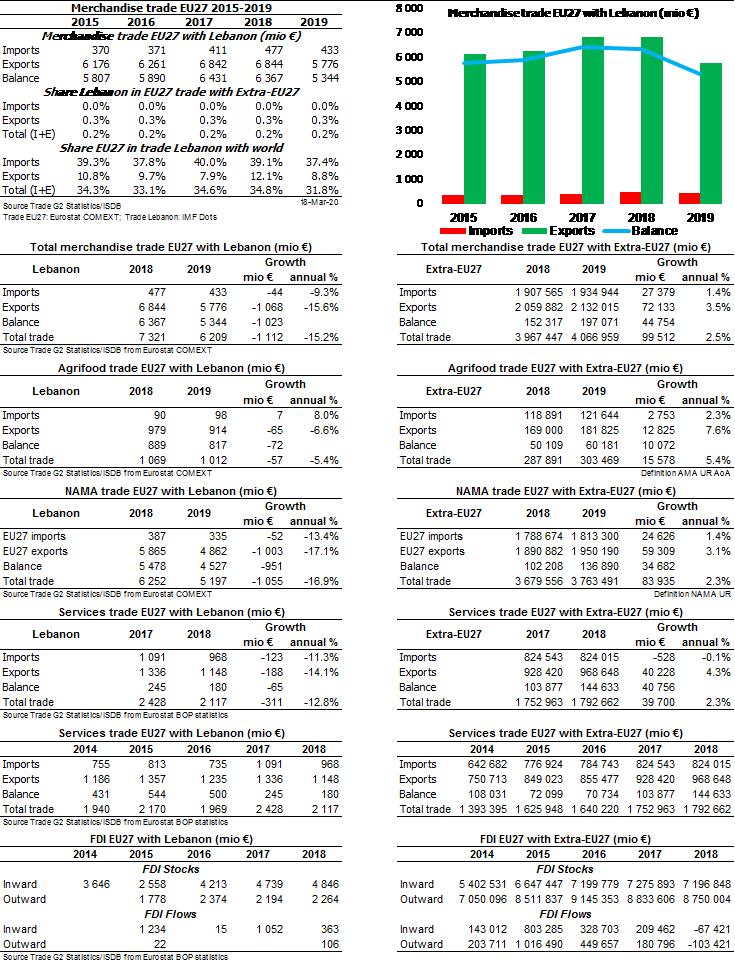

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE EU-LEBANON ASSOCIATION AGREEMENT

1.

Introduction

2.

Main open implementation issues, progress and follow-up actions

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

Specific Areas of Importance

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7.

Statistics

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE EU-MOROCCO ASSOCIATION AGREEMENT

1.

Introduction

2.

Main open implementation issues, progress and follow-up actions

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

Specific Areas of Importance

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7.

Statistics

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE EU-PALESTINE INTERIM ASSOCIATION AGREEMENT

1.

Introduction

2.

Main open implementation issues, progress and follow-up actions

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

Specific Areas of Importance

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7.

Statistics

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE EU-TUNISIA ASSOCIATION AGREEMENT

1.

Introduction

2.

Main open implementation issues, progress and follow-up actions

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

Specific Areas of Importance

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7.

Statistics

PART IV: AFRICAN, CARRIBEAN AND PACIFIC COUNTRIES

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE ECONOMIC PARTNERSHIP AGREEMENT (EPA) BETWEEN THE EU AND THE SOUTHERN AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT COMMUNITY (SADC)

1.

Introduction

2.

Main implementation issues

2.1

Main open issues, progress and follow-up

2.2

Progress in the implementation of trade and sustainable development provisions

2.3

Legal enforcement – dispute settlement case

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

trade and Development Cooperation and Specific Areas of Importance

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7.

Statistics

1.

Introduction

2.

Main implementation issues

2.1

Main open issues, progress and follow-up

2.2

Trade and sustainable development goals

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

trade and Development Cooperation and Specific Areas of Importance

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7.

Statistics

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE ECONOMIC PARTNERSHIP AGREEMENT (EPA) BETWEEN THE EU AND COTE D’IVOIRE

1.

Introduction

2.

Main implementation issues

2.1

Main steps in implementation

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

trade and Development Cooperation and Specific Areas of Importance

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1 Economic environment

5.2 Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7.

Statistics

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE ECONOMIC PARTNERSHIP AGREEMENT (EPA) BETWEEN THE EU AND GHANA

1.

Introduction

2.

Main implementation issues

2.1

Main steps in implementation

2.2

Trade and sustainable development goals

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

trade and Development Cooperation and Specific Areas of Importance

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7.

Statistics

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE ECONOMIC PARTNERSHIP AGREEMENT (EPA) BETWEEN THE EU AND CAMEROON

1.

Introduction

2.

Main implementation issues

2.1

Main steps in implementation

2.2

Trade and sustainable development goals

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

Trade and Development Cooperation

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7.

Statistics

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE ECONOMIC PARTNERSHIP AGREEMENT (EPA) BETWEEN THE EU AND CARIFORUM

1.

Introduction

2.

Main implementation issues

2.1

Main open issues, progress and follow-up

2.2

Progress in the implementation of trade and sustainable development provisions

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

Trade and Development Cooperation

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7.

Statistics

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE ECONOMIC PARTNERSHIP AGREEMENT (EPA) BETWEEN THE EU AND PACIFIC STATES

1.

Introduction

2.

Main implementation issues

2.1

Main steps in implementation

2.2

Trade and sustainable development goals

3.

Activities of the implementation bodies

4.

trade and development Cooperation and Specific Areas of Importance

5.

Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1

Economic environment

5.2

Trade in goods

5.3

Trade in agricultural products

5.4

Trade in services and Foreign Direct Investments

6.

Conclusions

7.

Statistics

DATA USED FOR THE COMPILATION OF INDIVIDUAL REPORTS AND INFORMATION SHEETS

The trade statistics used in this staff working document on the evolution of trade and investment flows are based on EUROSTAT data as available on 30 March 2020 for EU17, except where indicated otherwise. The most recent annual data available for trade in goods are for 2019, and for services and investment for 2018, except where indicated otherwise. GDP growth figures for partner countries for 2019 in sections 5.1 Economic Environment of the country sheets reflect World Bank national accounts data and OECD National Accounts data files, except where indicated otherwise.

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE 15 POINTS ACTION PLAN ON TRADE AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

1.Introduction

In 2019, the Commission continued to improve the implementation and enforcement of the Trade and Sustainable Development (TSD) chapters of EU trade agreements, in line with its 15-point action plan of February 2018.

The present section provides an overview of the main activities undertaken by the Commission as per the four strands of the action plan: “working together”, “enabling civil society”, “delivering” and “transparency”. More detailed information on the advances in the context of the implementation of the TSD chapter of the various trade agreements, including summary accounts of the meetings of the respective TSD committees, can be found in the country sheets. notably section 2.2, “Progress in the implementation of trade and sustainable development provisions”.

2.Working together strand

In 2019, the Commission continued to partner with Member States, the European Parliament, as well as international organisations to advance on the implementation of TSD chapters. The main activities are outlined below.

The meetings of the TSD Expert Group continue to be the main channel for engagement between the Commission and Member States on TSD issues. In the three meetings held in 2019 the Commission updated Member States on the advances made in the different implementation processes. These meetings were also opportunities for the Commission and Member States to exchange information on relevant developments in the partner countries, and to coordinate actions to ensure complementarity.

In 2019, the Commission also continued to engage with the European Parliament through monitoring groups, INTA Committee agenda points, and by providing technical debriefs as requested.

With international organisations it is to highlight the close collaboration with the International Labour Organisation (ILO), which has become a key component of TSD implementation. To make this collaboration as operational as possible the Commission and the ILO met twice in 2019 to exchange views on the effective implementation of fundamental ILO Conventions by trade partners. These meetings also allowed the Commission and the ILO to take stock of technical assistance needs, and identify synergies building on the experience gained with other projects with similar objectives.

To be able to swiftly activate technical assistance actions the Commission and the ILO launched the ‘Trade for Decent Work’ project in the end of 2018. This project has since become a crucial instrument to support the advances in the implementation of labour commitments in TSD Chapters as well as for enacting pre-implementation efforts.

In 2019, the project funded technical assistance actions in Vietnam in support of the labour reforms necessary to comply with TSD commitments under the EU-Vietnam trade agreement. The project also funded actions to enhance the capacity of ILO constituents (including the Vietnamese government, employers and workers’ organizations) to advance in the implementation the TSD Chapter with regards to the effective implementation of international labour standards. The Commission and the ILO agreed that in 2020, the project will fund additional activities in Vietnam as well as new actions to strengthen labour inspection in Ecuador and Peru.

The Commission and the ILO also cooperated closely in Central America. The Commission continued to fund the implementation of an ILO project on compliance with international labour standards in El Salvador and Guatemala. In El Salvador, this project provided support to the reactivation of the High Labour Council (tripartite labour consultation body), which had been inactive since 2012.

3.Enabling civil society to play their role in implementation

In 2019, in addition to regularly interacting with EU civil society, notably by participating in the regular meetings of the EU domestic advisory groups (DAGs) created under each trade agreement, the Commission also continued to take actions to facilitate monitoring by civil society and to further promote responsible business conduct. The main activities are outlined below.

Enabling monitoring by civil society

In 2019, the Commission continued to use the Partnership Instrument-funded project (worth 3 EUR million) launched in 2018 to support the DAGs and ensure that they can carry out their monitoring role. More specifically, with this project the Commission covered the travelling costs of a number of members of DAGs from the EU and from trade partners to enable them to participate in Civil Society Fora. The project also financed capacity-building workshops for members of the DAGs of the EU-Georgia DCFTA in March 2019, of the DAGs of the EU-Central America FTA in June 2019, of the DAGs of the EU-Ukraine DCFTA in November 2019, as well as for the members of the consultation mechanisms of the EU-Colombia/Ecuador/Peru Trade Agreement in October 2019. In January 2020, the project financed the organisation of a workshop for civil society organisations in Tokyo to explain the commitments in the TSD Chapter of the EU-Japan EPA. All these events created opportunities for DAG members to receive training and to exchange views among themselves about the nature of TSD commitments and their monitoring role.

As part of its pre-implementation engagement with Vietnam, in December 2019 the Commission also organised workshops in Hanoi for representatives of the government and civil society to prepare the ground for the setting up of a local DAG to monitor the EU-Vietnam FTA.

Promoting the involvement of business

To mobilise the role of the business community in support of the sustainable trade agenda, the Commission continued to promote Corporate Social Responsibility/Responsible Business Conduct (CSR/RBC), notably via the multiple activities set up under two large (9 million euros worth) EU-funded projects: one focused on Asia (launched in 2018) and one for Latin America. These projects offer practical support to governments’ efforts to create enabling conditions for sustainable businesses by promoting CSR/RBC practices and by encouraging and assisting the uptake by businesses of international due diligence guidelines, following international standards.

The project for Latin America was launched in January 2019. It allowed the Commission to join forces with the ILO, OECD and OHCHR, which are the leading institutions in the field. The 4-year project will count on their recognised expertise and long-standing experience in the field to create leverage and ensure the active involvement and buy-in from governments and stakeholders in Latin America.

In the first 6 months of the project, the inception phase led to the identification of the several initiatives to be implemented at the regional and country level, in close consultation with authorities and stakeholders. These initiatives will cover inter alia the development of tools for governments to promote CSR/RBC and the setting up of training activities and awareness raising actions for officials, businesses and stakeholders. As the project covers several countries that are party to existing and future EU trade agreements, these initiatives will be deliverables for the implementation of the TSD Chapters. They will eventually constitute key contributions to ensure that the trade liberalisation is led by inclusive and sustainable businesses.

4.Delivering

In 2019, the Commission continued to put in place initiatives aimed to deliver material advances in the areas that have been identified as TSD priorities for each trade partner. The setting up of these priorities allows the Commission to focus on the issues that matter the most for each partner.

These initiatives ranged from advocacy and technical assistance to efforts to ensure the early ratification of ILO fundamental conventions, to more assertive actions to enforce commitments where shortcomings are identified. The Commission also partnered with Member States to produce materials to build capacity for TSD implementation and raise awareness. One area that is now receiving increasing attention is the design of concrete actions to use TSD implementation to promote climate action. The main actions in 2019 are outlined below.

Encouraging early ratification of fundamental ILO conventions

With partners in “pre-FTA implementation” and “early FTA implementation” phase, the Commission focused on the ratification of outstanding ILO conventions. With Vietnam, the Commission engaged closely with the authorities and civil society via regular contacts, including two missions to Hanoi in May and December 2019. Such efforts led to concrete results as Vietnam embarked in far-reaching labour reforms to be in line with the TSD commitments in the FTA. In June 2019, Vietnam announced the ratification of the ILO Convention #98 on Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining. Furthermore, the authorities presented a calendar for the ratification of ILO Convention #87 on Freedom of Association and ILO Convention #105 on Forced Labour. In November 2019, Vietnam adopted a new Labour Code. The EU is working closely with Vietnam’s authorities to support further necessary reforms of the labour legislation, building on a very close cooperation with the ILO.

The Commission also engaged with Singapore on the need to ratify the outstanding ILO conventions (#87 on Freedom of Association, #105 on Abolition of Forced Labour, and #111 on Discrimination in Employment and Occupation) and to observe the Fundamental Rights at Work principles. Similarly, the EU passed strong messages to Japan about the need to ratify the two missing ILO conventions (#105 on Abolition of Forced Labour and #111 on Discrimination in Employment and Occupation). The Commission raised these issues at the bilateral discussions held during the missions to Singapore and Tokyo in May 2019 to prepare the start of the implementation work of the two FTAs.

Capacity building - Handbook

The Commission continued to support partners in their efforts to put in place institutional frameworks that match the specificities of TSD implementation, which require high levels of internal coordination across several ministries and close monitoring of civil society. Culminating a process that lasted more than one year, in August 2019, Sweden’s National Board of Trade published the handbook for TSD implementation for Ecuador, which was developed in partnership with the Commission. This tool can also assist TSD implementation processes by other partners in the future.

Assertive enforcement

The Commission sharpened its monitoring and analysis of partners’ compliance with TSD commitments. The two most prominent examples of the increased assertiveness by the Commission in this regard continue to be Peru and South Korea. With both partners, there were important developments.

With Peru, the Commission continued the close engagement aimed to improve TSD implementation. The bilateral understanding reached in Quito in December 2018 to address the EU’s substantive concerns allowed for a renewed momentum for TSD implementation in 2019. At the meeting of the TSD Sub-committee of the EU-Colombia/Ecuador/Peru Trade Agreement in Bogota in October 2019, the EU and Peru took stock of the progress made. Peru was keen on showing advances by listing a number of concrete policy developments in the areas of labour and environment. The Commission will continue to monitor closely the situation in Peru, notably on the need to further improve the effectiveness of consultation of civil society on TSD-relevant issues.

With South Korea, the EU resorted for the first time to a bilateral dispute settlement mechanism for TSD issues. In January 2019, the EU and South Korea held consultations in Seoul over the lack of implementation by Korea on the commitments to ratify pending fundamental ILO conventions and to respect in law and practice the core principles of the ILO, notably on freedom of association and right to collective bargaining. As consultations did not resolve matters, a panel of experts was officially established on 30 December 2019. This is a major step by the EU, which already triggered concrete political reactions in Korea. In October 2019, the Korean Government submitted to the National Assembly bills to pursue ratification of three fundamental ILO Conventions (#87 and #98 on Freedom of Association and #29 on the Forced Labour) and related reforms on freedom of association. However, the National Assembly has not managed to advance so far.

Climate action

As climate change becomes an ever more important component of international engagement, the Commission is using the implementation of TSD Chapters to promote concrete joint actions with partners in this field. The work under CETA is leading the way, following the adoption of the Recommendation on Trade and Climate. On 24 January 2019, the Commission hosted a trade and climate workshop that brought together civil society and businesses to discuss the nexus between trade and climate. As a follow up initiative, on 6 and 7 November 2019, Canada and the EU organised in Montreal a workshop for clean tech firms. The EU and Japan are currently planning on actions along these lines for early 2021 in the context of the EU-Japan Agreement.

5.Transparency

The Commission continued its efforts to improve transparency on issues related to the implementation and enforcement of TSD provisions in EU trade agreements, notably by making information more easily accessible on the TSD webpage in the Commission website.

In addition, the Commission is putting in place efforts to agree with all partners the publication of relevant TSD implementation documents. As a result, in 2019 the Commission made the joint reports/statements and/or minutes of the TSD committees of most trade agreements available in its website.

On 29 April 2019 the Commission organised a Civil Society Dialogue session fully dedicated to TSD to give an account of the progress made so far with the implementation of the 15-point action plan. All the information related to that meeting, including the minutes are publically available.

The Commission also remains committed to act in full transparency with regard to inputs filed by civil society.

PART I:

ASIA

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON PREPARATIONS FOR THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE FREE TRADE AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE EU AND ITS MEMBER STATES AND SINGAPORE

1.Introduction

The economic partnership between the EU and Singapore is made up of two distinct agreements, namely a free trade agreement (henceforth the ‘trade agreement’) and an investment protection agreement. Negotiations began in 2009, with negotiations for the trade agreement and the investment protection agreement being completed in 2012 and 2017, respectively. The EU-Singapore Investment Protection Agreement sets out rules that give EU investors and their investments in Singapore a high level of protection, while safeguarding EU governments' right to pass new laws and update existing ones. It will replace and upgrade bilateral investment treaties that several Member States currently have in place with Singapore. Once ratified, the Investment Protection Agreement will replace investor-to-state dispute mechanism under existing bilateral investment treaties with an Investment Court System. The trade agreement entered into force on 21 November 2019, and the investment agreement will enter into force once ratified domestically by the EU Member States. This information sheet reports about preparations for the entry into force of the trade agreement.

Singapore is a major developed economy. In 2018 it had a GDP of €326 billion and a GDP per capita of €57,900. Over 10,000 EU companies are established in Singapore which is the EU’s largest trade partner in Southeast Asia, accounting for one-third of EU trade with the region and over two-thirds of EU foreign direct investment stock in the region. The trade and investment agreements are expected to contribute to solidify this situation by removing remaining obstacles and protecting EU investments. EU trade in goods and services with Singapore in 2018 was worth €118 billion, with the free trade agreement expected to facilitate further growth.

Singapore is an important regional economic actor, and is part of a number of major regional trade agreements, including the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership

CPTPP

, the China-Singapore Free Trade Agreement

CSFTA

and the ASEAN Free Trade Area

AFTA

. As member of ASEAN, Singapore is also actively engaged in the negotiations for the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) comprising ASEAN and its 6 major FTA partners. Singapore’s membership of ASEAN also gives it notable political as well as economic influence in the South East Asia region.

The EU-Singapore trade and investment agreements, therefore, represents an important success to solidify and uphold the EU’s presence in the region. These are the first agreements on trade and investment the EU ever concluded with an ASEAN member state. The agreements also offer new opportunities for EU companies to expand into other Southeast Asian markets, as it will provide them with even more opportunities and stronger protection to do business with or establish itself in Singapore, which is the central hub in South East Asia. The Agreements could be seen as an inspiration for trade and investment agreements between the EU and other ASEAN Member States and as a step towards a region to region agreement.

2.The agreements in summary

Together, the agreements cover trade in goods (including electronics, pharmaceuticals, petrochemicals and processed agricultural products), services and establishment (including telecommunications, finance, transport and manufacturing), public procurement, intellectual property and investment protection.

In terms of tariff liberalisation, the trade agreement eliminates 84% of customs duties on Singaporean exports to the EU within the first year, and by the third year 90% of tariffs on Singaporean exports to the EU will be removed. Customs duties on remaining qualifying exports will be removed over a period of 5 years. Singapore eliminated all its remaining customs duties for beer, samsu and stout upon entry into force of the agreement and committed to fully bind its current level of duty-free access for all products originating in the EU.

The trade agreement provides enhanced market access for service providers, professionals and investors, and creates a level-playing field for businesses in each other’s markets, including through certain sector specific rules on non-discrimination and transparency, covering a wide range of services such as financial services, professional services, computer and related services, research and development, business services and telecommunication services.

With regard to public procurement the trade agreement will improve market access for EU suppliers and for EU goods and services on the basis of a set of rules and principles of transparency, non-discrimination and fairness in public procurement procedures. As party to the WTO Agreement on Government Procurement (GPA), Singapore has already opened up a large part of its procurement market to EU bidders. The Free Trade Agreement increased market access opportunities for EU businesses as Singapore included additional entities as well as subjected more services contracts to rules; the applicable thresholds are also lowered. Additional coverage by Singapore include, for instance, financial services, computer related services, telecommunication services, sewage and refuse disposal, architectural and engineering services.

To continue encouraging innovation, the trade agreement includes a comprehensive intellectual property rights chapter covering provisions on copyright, designs, enforcement and geographical indications (GIs). Upon entry into force, Singapore enhanced its border enforcement measures against goods infringing IPR, covering copyrights and trade marks.

The trade agreement will also promote sustainable development and the involvement of civil society in trade and investment matters. It does so by setting out strong, legally-binding commitments on environmental protection and respect for labour rights. As such, parties commit to respecting, promoting and effectively implementing the principles concerning the fundamental rights at work and to make continued and sustained efforts towards ratifying and effectively implementing the fundamental ILO conventions. The agreement includes commitments by the EU and Singapore on the effective implementation of Multilateral Environmental Agreements to which the EU and/or Singapore have signed up to. Specific provisions on climate change further underline the EU’s and Singapore’s efforts to tackle climate change. The agreement also promotes cross-cutting schemes such as Corporate Social Responsibility, Responsible Business Conduct, fair trade and green procurement, and creates a mechanism to foster civil society involvement, related to the implementation of TSD and consultative mechanisms.

Non-tariff barriers to trade will be dealt with in electronics, motor vehicles/parts, pharmaceuticals and medical devices and renewable energy.

Under the EU-Singapore trade agreement, the EU and Singapore have committed to strengthen cooperation in customs procedures to facilitate EU exports to enter the country. In addition, the trade agreement includes a Chapter on Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures, which will further streamline the approval for meat exports, with time limits for the application process and prelisting for establishments to apply.

Furthermore, Singapore has already set up a geographical indications (GI) registry, allowing EU rights-holders to apply for registration. The 2014 GI Act and implementing rules entered into application on 1 April 2019, which opened the procedure for application and subsequent registration of European GI names.

At the beginning 2020, 139 European GI names have been registered and are protected in Singapore under the domestic legislation. They will eventually also be protected under the EU Singapore trade agreement.

3.Preparatory work for the entry into force

General preparations for the entry into force

During the course of 2019, the EU Delegation in Singapore organised several outreach events to promote and raise awareness on the benefits of the FTA. A joint brochure on the agreement was published between DG Trade and the Singapore Ministry for Trade and Industry:

https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2019/february/tradoc_157684.pdf

.

Before entry info force of the FTA the Commission published the adjusted list of TRQs for the remainder of the year.

With regard to government procurement, a project is in place under the Policy Support Facility of the Partnership Instrument that will help monitoring the implementation of the government procurement chapter. In addition Commission services and EU delegation in Singapore have carried out preparatory work to identify the actions that Singapore needs to take with a view to comply with the obligations of the GP Chapter of the Free Trade Agreement.

Preparing for the protection of EU geographical indications

An important part of preparatory work concerned the preparations for the protection of EU geographical indications in Singapore. Instead of being protected within the agreement itself, it was agreed that Singapore would allow for the registration of EU geographical indications after the European Parliament’s consent, but before conclusion of the agreement. Successfully registered geographical indications would then be given protection under the trade agreement subject to a decision by the EU-Singapore Trade Committee set up under the agreement. During the preparatory phase it became apparent that this protection could be challenged via a so-called “Qualification of Rights” provision in the Singaporean legislation. Before the Council decision to adopt the Free Trade Agreement, Singapore gave additional guarantees to safeguard the protection of registered GIs and clarified the limited scope of this Qualification of Rights procedure.

In July 2019 the Commission organised a seminar for senior EU GI rights-holders and EU Member States on Geographical Indications for Agri-food products, during which the provisions related to geographical indications under the EU Singapore trade agreements were explained.

4.early achievements and up-coming implementation activities

Geographical indications

Following the consent given by the European Parliament on the conclusions of the Agreement in February 2019, and in accordance with Article 10.17(2)(a) of the EU-Singapore Free Trade Agreement (EUSFTA), Singapore set up a geographical indications (GI) registry allowing EU GI holders to apply for registration. The implementing rules entered into application on 1st March 2019, which opened the procedure of GI registration and led to the subsequent official applications of European GI names. At the end of August 2019, the domestic registration process of the EU GIs was finalised and 138 GIs were registered. They are protected under the EU Singapore trade agreement.

Upcoming activities by the Trade Committee

In 2020, the Trade Committee will adopt a decision on the list of protected GIs within the scope of the Free Trade Agreement, so as to provide successfully registered GIs direct protection under the agreement. The Trade Committee will also establish the list of arbitrators tasked to deal with eventual future disputes. The Trade and Sustainable Development Board, the institutional body of the Free Trade Agreement overviewing the implementation of the Trade and Sustainable Development Chapter, is also to be set up within the first year of entry into force of the agreement.

5.Statistics

SINGAPORE

ANNUAL INFORMATION SHEET ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE ECONOMIC PARTNERSHIP AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE EU AND JAPAN

1.Introduction

This is the first time that the Commission reports on the implementation of the Agreement for an Economic Partnership between the EU and Japan (hereafter “the agreement”). The reporting covers the implementation of EU-Japan trade over 11 months: from February to December 2019. Implementation reports in coming years will cover full-year periods.

The agreement entered into force on 1 February 2019. It is one of the most ambitious trade agreements concluded by the EU so far, providing for broad-based trade liberalisation coupled with rules and disciplines on aspects such as labour rights, environmental protection, antitrust, corporate governance and the commercial activities of state-owned enterprises, among other topics. The agreement thus pursues and develops the EU strive towards comprehensive trade agreements, and it provides a sound basis for the development of economic relations between the Parties.

The agreement is particularly important for the EU agri-food sector, offering huge potential for increasing EU exports of a large number of products, such as wine, pork, beef, cheeses and processed agricultural products. One noticeable achievement is the step by step approval and recognition of oenological practices of the other Party.

A brief overview of activities of the Working Groups and Committees set up by the agreement is also included in the report. The EU implements a policy of transparency as regards the work of these bodies. Their agendas, minutes and decisions are publicly accessible on the Europa website.

2.Main implementation issues

2.1 Main open issues, progress and follow-up

The EPA Joint Committee – the highest body under the agreement – which meets at ministerial level – gathered for the first time in Tokyo on 10 April 2019 and it laid the ground for the various specialised committees and working groups to start their work. All specialised committees and working groups, as well as the joint Dialogue with Civil Society and the EU-Japan joint Financial Regulatory Forum, met within the first year of implementation.

In 2019, there were also several events and initiatives aimed at raising awareness among stakeholders, with a view to supporting their use of the opportunities opened up by the agreement. Many prominent public and private organisations at national or regional level in Europe, such as chambers of commerce, organised seminars and conferences to present the agreement to the business community. The European Commission supported such efforts by providing speakers and information materials. The EU Delegation in Tokyo consistently engaged with representatives of European companies in Japan, as well as with Japanese importers, in order to gather their practical experiences and to convey the latest information on implementation steps. Furthermore, the EU-Japan Centre for Industrial Cooperation, which is jointly supported by the EU and Japan, set up a specific “Helpdesk” to address questions from SME, drafted targeted factsheets for the EU operators and organised “webinars” to provide information on key areas of the agreement (agri-food sector, customs procedures, procurement etc.).

In view of the importance of the agreement for the agri-food sector, several specific awareness raising and promotion activities were organised with a specific focus on that area:

·A high level mission was organised in May 2019 with 70 businessmen from the EU agri food sector: training and targeted information on the Japanese market was provided, back-to-back with political discussions at ministerial level;

·In March 2019 EU representatives participated in the major B-to-B agri food fair in Asia (Foodex) with an EU booth dedicated to the authenticity, safety and quality of EU products; a seminar on the opportunities stemming from the EPA for the European and Japanese agri-food operators was organised on that occasion;

·Several promotion activities in various places of Japan were organised to follow up to the participation to the Foodex fair;

·The EU-Japan Centre for Industrial Cooperation, through its EPA Helpdesk, addressed questions from SMEs in the agri food sectors; it also issued targeted factsheets and organised specialised “webminars” to provide information on key areas of the agreement for the agri-food sector.

2.2Progress in the implementation of trade and sustainable development provisions

Preparations for the implementation of the TSD chapter

The agreement has the most comprehensive chapter on trade and sustainable development ever concluded by the EU. Therefore, the initial focus over the first months after entry into force of the Agreement was on the joint clarification of actions and mechanisms needed for implementation, on the basis of the provisions of the chapter.

Prior to the entry into force of the agreement, Japan commenced its preparation for implementing the trade and sustainable development (TSD) provisions by setting up an inter-ministerial coordination group, led by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Later, Japan designated two existing bodies to operate as “domestic advisory groups” for the purposes of the agreement: the “Central Environmental Council” and the “Labour Policy Council”.

In May 2019, EU and Japanese officials had already started consultations to prepare the kick-off meetings of the TSD Committee and the Joint Civil Society Dialogue. Discussions on the agendas of both meetings, as well as practical organisational and operational details were held over the course of the second half of the year, leading to the formal meetings in January 2020.

The Committee on Trade and Sustainable Development met in Tokyo on 29-30 January. The Committee reached an understanding on the organisational modalities of the Joint Dialogue with Civil Society. It addressed topics pertaining to labour rights, environmental protection and horizontal sustainability issues. In particular, it discussed the streamlining of bilateral activities on Corporate Social Responsibility and Responsible Business Conduct; the Parties exchanged information about developments concerning multilateral environmental agreements and other international environmental initiatives, including in the areas of climate change, sustainable forest management, oceans and marine litter, and circular economy; and they exchanged views on how to strengthen the implementation of the Agreement through joint or coordinated activities in these and other areas. Both sides presented an update on ratification and implementation of International Labour Organization (ILO) conventions. The EU informed Japan about recent social policy developments in Europe, notably on the social fairness package. Japan reiterated its commitment to the activities of the ILO and also informed about ongoing discussions regarding the ratification of the ILO C105 and C111, referring to the Resolution of Japan’s legislative chambers of 26 June “on Japan's further commitment toward ILO, on the occasion of 100 year anniversary of ILO”.

EU and Japan held the first Joint Dialogue with Civil Society on 31 January 2020. Representatives from governments and civil society organisations discussed crosscutting issues such as corporate social responsibility, Society 5.0 for Sustainable Development Goals, issues related to trade and environment such as trade-related aspects of circular economy, climate change and low carbon society as well as trade and labour, including updates on ratifications and implementations of ILO conventions update, and female participation in labour market.

Steps taken to promote sustainability goals

Domestically and internationally both sides undertook actions to support their ongoing efforts with regard to sustainability goals. Japan positively used its G20 chairmanship to give further prominence to issues related to the circular economy and the prevention of marine litter – issues on which the EU has an active agenda. On labour issues, on 26 June the Japanese House of Councillors and the House of Representatives adopted a “Resolution on Japan's further commitment toward ILO, on the occasion of 100 year anniversary of ILO”, emphasising the importance of the fundamental rights at work and of making efforts towards ratification or implementation of all ILO core conventions.

3.Activities of the implementation bodies

The agreement establishes ten specialised committees and two working groups. The annual meeting of the Joint Committee at ministerial level plays a supervisory role and ensures that the agreement operates properly. In addition, the agreement establishes a Joint Dialogue with Civil Society and a Joint Financial Regulatory Forum.

The agendas, minutes and decisions of specialised committees and working groups are publicly accessible on the Commission’s website. This report presents only some of the main important issues that were addressed.

The Joint Committee adopted two decisions. Decision no.1 laid down the Rules of Procedure of the Joint Committee, which apply mutatis mutandis to all the bilateral bodies that report to it. Decision no.1 also endorsed several legal texts to render the dispute settlement mechanism of the agreement fully operational: rules of procedure of arbitration; code of conduct of arbitrators; and mediation rules. Subsequently, through its Decision no.2, the Joint Committee established a list of individuals that are willing and able to serve as arbitrators.

The Parties worked intensively throughout 2019 and were able to tackle some initial difficulties experienced in the area of Customs and Rules of Origin procedures (see further below in section 4).

The committees responsible for Trade in Goods; Trade in Services, Investment Liberalisation and E-commerce; and Technical Barriers to Trade met back-to-back in Brussels in November 2019. The committees allowed an overview of the implementation of the relevant chapters of the Agreement.

In the Trade in Goods Committee the Parties focused, among others, on the quota management procedures for the import into Japan of certain agricultural commodities and processed agricultural products, which were adjusted by Japan in summer 2019 to allow for a better utilisation of the quotas by importers in Japan. In particular, work has been done in the first year to improve the administration of tariff rate quotas (TRQs) by Japan in order to allocate TRQs to importing companies with a proper record of marketing the goods at stake. Indeed, following the first phase of allocation, too many non-genuine agri-food business operators had applied to obtain quotas, particularly in the cheese sector which raised concerns. It is expected that the quota utilisation rates, i.e. the fill rate, will steadily increase in the coming months, thanks to the improvement in management procedures and regular monitoring by the EU Commission.

The TBT committee mainly exchanged information about respective regulatory plans concerning the potential restriction of certain chemical substances, revisions to respective medical devices legislation and the EU raised the issue about the alteration of lot numbers on products in Japan.

In the first meeting of the Committee on Trade in Services, Investment Liberalisation and Electronic Commerce, the EU reported market access issues in Japan for postal and courier services while Japan reported difficulties regarding mode 4 (delays in issuing visas) in some EU Member States.

The Committee on SPS Measures met in Tokyo on 28-30 October 2019. EU and Japan discussed their respective priorities: for the EU prioritised market access applications on beef and certain fruits (cherry, pear and kiwi), regionalisation on African Swine Fever and Avian Influenza; for Japan prioritised market access applications on poultry meat and black pine bonsai plants and change of classification on poultry and pork products.

The Parties also discussed ways to simplify, expedite and complete approval procedures without undue delay, e.g. using experience gained from assessment results of already approved EU Member States in view of the EU harmonised legislation; the possibility to evaluate EU Member States in groups when conducting the risk assessment and to simplify the procedures of risk assessment on plant quarantine. Food contact materials and additives were among other topics discussed where Parties looked to enhance coorperation during 2020.

The Parties discussed next steps regarding the project for the mutual recognition on regionalisation in the area of animal health, and confirmed their willingness to proceed with the examination through video conferences and other means of communication in order to move forward the discussion and achieve tangible deliverables within the deadlines mutually agreed in advance. Parties agreed that the results will be reported to the next EPA Joint Committee meeting. It was also agreed to establish a technical group dealing with animal health issues whose progress and results will be referred to the SPS Committee.

EU and Japan committed to closely follow up on the progress on the prioritised market acess applications, through video and audio conferences at regular intervals.

The first exchange of possible cooperation on animal welfare issues took place in 2019, although these aspects will be explored during 2020.The parties are now considering the scope of such cooperation and how it could be organised in the future.

The committees responsible for Government Procurement and for Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) met back-to-back in Tokyo in November 2019. Both committees went through a long list of issues related to the implementation of the two chapters and the latest legislative and policy developments.

The IPR Committee had an exchange on the process toward extension of the list of geographical indications (GIs) as foreseen in the Agreement, on IPR enforcement (including actions to guarantee the enforcement of specific GIs) as well as on several issues that remained open during the negotiations (the public performance right and the resale right for the EU; grace period for patents for Japan).

The Public Procurement committee met back-to-back with the Railways Industrial Dialogue and focussed in particular on four major issues related to the implementation of the agreement: the implementation of an obligation to publish all procurement notices on a Single Point of Access (Art. 10.4 of the EPA); the communication of legal measures adopted to give effect to the market access commitments under the Procurement Chapter under the FTA; the access of European bidders to Government Procurement in Japan relating to the operational safety of railways and measures to disseminate information relating to the correct application of the EPA Procurement chapter among procuring entities, in particular at sub-central level.

The Committee on Cooperation in the Field of Agriculture met in July 2019 in Tokyo (link to report). It was an opportunity to exchange information on agricultural issues of common interest. Exchanges on agricultural policy reforms aimed at addressing the environment and climate change dimension of agricultural activities, as well as organic farming policy reform in the EU and implications for the equivalence arrangements between the EU and Japan took place.

Two bodies held meetings remotely, by videoconference. These were the Working Group on Wine in February 2019 and the Committee on Regulatory Cooperation on 20 January 2020. The videoconference of the Committee on Regulatory Cooperation was devoted to organisational issues, with the aim of establishing a common understanding on the role and functioning of the committee and its relationship with other specialised committees and bilateral fora. The Working Group on Wine adopted two decisions, as envisaged in the EU-Japan Agreement, on the forms to be used for certificates for the import of wine products originating in Japan into the European Union and the modalities concerning self-certification, and on the modalities for cooperation between Contact Points. It has also endorsed the notifications of both sides confirming the approval of several oenological practices as described in Annex 2-E of the Agreement, thus facilitating trade through the recognition of each other’s regulations.

Finally, the Working Group on Motor Vehicles and Parts addressed ongoing regulatory issues of international relevance, including cooperation in the context of the UNECE WP29, as well as other car-related issues and technical regulations. The Working Group concluded on the desirability to amend the appendices of the Agreement concerning UNECE Regulations implemented by both Parties, in order to reflect the most recent developments and commit bilaterally to the application of the relevant regulations, which facilitate trade.

4.Specific Areas of Importance

To ease the utilisation of tariff preferences under the agreement, the authorities responsible for Customs matters in the EU and Japan engaged intensively throughout the first year of implementation in order to ensure a common approach to the application of trade preferences. In June 2019, the Committee on Rules of Origin and Customs-Related Matters developed a roadmap of actions to tackle initial difficulties experienced by economic operators. The actions were gradually rolled out by both sides. A simplified procedure for claiming and obtaining tariff preferences was put in place by Japan in two phases – in August and November, having a positive effect on the ease with which operators can effectively utilise the agreed tariff preferences.

5.Evolution of bilateral trade

5.1Economic environment

Japan is the world’s third largest national economy but it faces significant challenges to generate and sustain growth. Over the past decade, Japan’s economy moderately expanded but in recent years and up to 2019 real GDP growth was on a declining trend. In 2019 Japan’s GDP grew by 0.7%. Like for other countries, the COVID-19 crisis will have a marked effect on economic activity.

Public and private investments have been an important growth driver of growth, supported by rising corporate earnings. However, Japan's gross-debt-to-GDP ratio has reached 239%. Central government debt stood at a record JPY 1,110 trillion as of December 2019, having more than doubled in size since 1997. The consumption tax was increased from 8% to 10% in October 2019, with the intention to use the proceeds to finance free education. Headline inflation continues to fluctuate around 0.5% y-o-y, reflecting downward pressures from the recent yen appreciation and upward pressures from the rise in food prices. Real effective exchange rate of the yen is much below long-term averages and further yen appreciation can be expected, which could undermine corporate profitability, investments and exports.

Japan faces the need to address labour shortages and invest in AI and digital upgrading of its businesses, for it to tackle the pressures resulting from negative demographic growth global competition.

As regards Japan’s trade with the world, in 2019 the total value was about €1,300 bl (€ 1,298 bl). The top three trading partners of Japan were China (21% of total trade), USA (15.3% of total trade) and EU27 (10.3% of total trade).

Japan's main import products include: petroleum, LNG, clothing and accessories, medical products and communication equipment. Japan is a major exporter of transport equipment, machinery and chemicals (including medical products).

In 2019, Japan had a trade deficit of JPY1.6 trillion. Japan's exports fell 5.6% from 2018 to JPY76.9 trillion (the US-China and Japan-Korea trade tensions both had a significant negative impact on Japanese trade). Japan's overall imports dropped 5.0% to JPY78.6 trillion primarily due to lower energy prices. On a bilateral basis, Japan enjoyed a trade surplus of JPY6.6 trillion with the US. Meanwhile, Japan posted a deficit of JPY756.4 billion with the EU28.

18 Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) have entered into force or been signed with 21 countries/regions to date

[1]. On 30 December 2018, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP or TPP11 Agreement) with 10 other trading partners entered into force

[2]. At the end of 2019, USA and Japan concluded a trade agreement which comprises an Agreement on Trade in Goods, focused on tariff liberalisation on a relatively small amount of bilateral trade

[3]; and an Agreement on Digital Trade.

Japan is also engaged in other initiatives, including the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement; bilateral negotiations with Colombia and Turkey; as well as negotiations for the trilateral Japan-China-Korea FTA.

5.2Trade in goods

Since 1 February 2019, bilateral trade with Japan takes place in a new context. On that date, the EPA entered into force and eliminated tariffs for a large number of goods, in particular those that were previously subject to relatively low import duties. In addition, for those categories with higher import duties, the EPA initiated a tariff phase-out period that will eventually lead to full liberalisation. In 2019, Japan implemented two successive tariff reductions pursuant to the EPA, on 1 February and 1 April.

The EPA thus improved trading conditions for most goods traded between the EU and Japan. However, important areas had already been fully or very significantly liberalised beforehand because of Japan’s and the EU’s WTO commitments. Some of the most important EU export products, such as pharmaceuticals, cars or machinery have benefitted from zero duties when imported into Japan for a long time. Therefore, the EPA was not expected to lead to a sudden and radical surge in EU exports. Rather, its intended effect was to spur trade growth for those goods that were previously subject to moderate or high tariffs and to support overall trade more gradually through non-tariff mechanisms, such as cooperation on customs issues and regulatory matters. In the longer term, the EPA should thus contribute to increasing economic links between the EU and Japan, preserving or increasing their respective shares in trade with each other.

In 2019, trade with Japan pursued an upward trend that started after the financial crisis. It is hoped that the new economic partnership will facilitate a rapid resumption of that upward trend once the Covid-19 crisis is fully under control.

Merchandise trade with Japan increased by 5.8% in 2019 compared to the previous year, in a balanced manner for both EU exports and imports.

Traditional EU exports to Japan, such as pharmaceuticals, transport equipment and machinery benefitted from steady growth. Product categories for which the EPA led to tariff cuts generally experienced higher growth: this is clearly the case for EU agri-food exports such as wine, meat, dairy and tobacco leaves (see following point), but also for industrial goods such as textiles, clothing and footwear (approximately +10% on average).

As regards imports from Japan, in 2019 there were noticeable increases for chemicals and transport equipment, in particular passenger cars (+16%). As regards the latter, however, strong yearly fluctuations linked to market and industry circumstances are rather common: the increase in 2019 can only be partly attributed to the EPA, as other factors had an arguably bigger impact (e.g. shifts in production of some models between international manufacturing sites of a same company).

Japan has communicated an average Preference Utilisation Rate (PUR) for imports of EU goods of 52.9 % for the period February to December 2019, calculated as the ratio of EU exports to Japan benefitting from a trade preference under the EPA divided by total exports eligible for a preference under the EPA. This means that more than half of all EU goods eligible for tariff preferences actually benefitted from those preferences, which is a promising result for the first year of implementation. At sectoral level, most EU agricultural exports by and large enjoyed the tariff preferences (86.3% on average) with particularly high rates for meats (99%) and wine (93%), dairy products (77%) and cheeses (77%). The rates for industrial goods, owing to usually more complex supply chains and often smaller preference margins, were significantly lower both in Japan and in the EU.

It should be noted that PURs typically grow over the years, as economic operators often need some time to adjust to the new trading conditions (review of supply chains, internal accounting mechanisms, etc.). A better awareness about relevant customs practices in the EU and Japan, which were the object of intensive work in 2019, should also have positive effects. It is therefore expected that, particularly for industrial goods, preference utilisation will grow over time.

The trade balance between the EU and Japan remained broadly stable and in line with the situation in previous years. Exports and imports display gradual growth at a similar pace and are broadly commensurate in value.

Similarly, the EU and Japan’s share of the other Party’s trade with the world remained stable and broadly in line with long-term trends. In 2019, Japan accounted for 3% of the EU’s external trade; while the EU accounted for 10.3% of Japan’s trade with the world. There is a very gradual upward trend as regards the importance of Japan as an export market for the EU – something, which the EPA will surely support, in particular in areas such as agri-food.

5.3Trade in agricultural products

The EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) is a major agreement for the EU agri-food sector offering big potential for increasing EU exports on a large number of products. The Commission is particularly committed to ensuring a correct implementation of the EPA so that benefits for the agri- food sector materialise. In particular, work has been done in 2019 to seek improvements in the administration of the tariff rate quotas (TRQs) by Japan in order to grant import licenses to established agri-food operators, to support and advance requests for access to the Japanese market upon completion of sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) procedures, and to agree on the implementation and recognition of regionalisation measures.

In 2019, total trade in agricultural goods between the EU and Japan reached €7.62 billion, with the EU having a large trade surplus of almost €7 billion. Both imports and exports grew by around 15% compared to 2018. In 2019 Japan was the 5th country of destination of EU exports of agricultural goods.

EU exports of agricultural goods accounted in 2019 for €7.28 billion (11.9% of EU total exports to Japan in 2019). The main categories of agricultural goods exported to Japan in 2019 were pork meat (19.1%, for a value of €1.39 billion), cigars and cigarettes (18%) and wine, vermouth and vinegar (13.2%).

EU imports reached in 2019 €347 million (an increase of 14.9% compared to 2018) and consisted mainly of spirits and liqueurs (17%), soups and sauces (15%) and fatty acids and wax (14%).

For sensitive agricultural products, the EU-South Korea FTA foresees specific tariff rates quotas (TRQs) the parties grant each other.

TRQs granted by Japan to the EU