EUROPEAN COMMISSION

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Brussels, 22.2.2017

SWD(2017) 75 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

Country Report France 2017

Including an In-Depth Review on the prevention and correction of macroeconomic

imbalances

Accompanying the document

COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK AND THE EUROGROUP

2017 European Semester: Assessment of progress on structural reforms,

prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances, and results of in-depth reviews

under Regulation (EU) No 1176/2011

{COM(2017) 90 final}

{SWD(2017) 67 final to SWD(2017) 93 final}

Contents

Executive summary1

1.Economic situation and outlook4

2.Progress with country-specific recommendations10

3.Summary of the main findings from the MIP in-depth review13

4.Reform priorities21

4.1.Public finances and taxation21

4.2.Financial sector29

4.3.Labour market, education and social policies32

4.4.Competitiveness39

4.5.Sectoral policies48

A.Overview Table54

B.MIP Scoreboard61

C.Standard Tables62

References67

LIST OF Tables

1.1.Key economic, financial and social indicators – France9

2.1.Summary Table on 2016 CSR assessment11

3.1.MIP Assessment Matrix (*) – France 201719

4.2.1.Financial soundness indicators, all banks in France29

4.4.1.Labour productivity growth (per person employed) in France and in the rest of the euro area42

B.1.The MIP scoreboard for France61

C.1.Financial market indicators62

C.2.Labour market and social indicators63

C.3.Labour market indicators (cont.)64

C.4.Product market performance and policy indicators65

C.5.Green growth66

LIST OF Graphs

1.1.Contributions to GDP growth (2010-2018)4

1.2.Potential GDP growth breakdown in France5

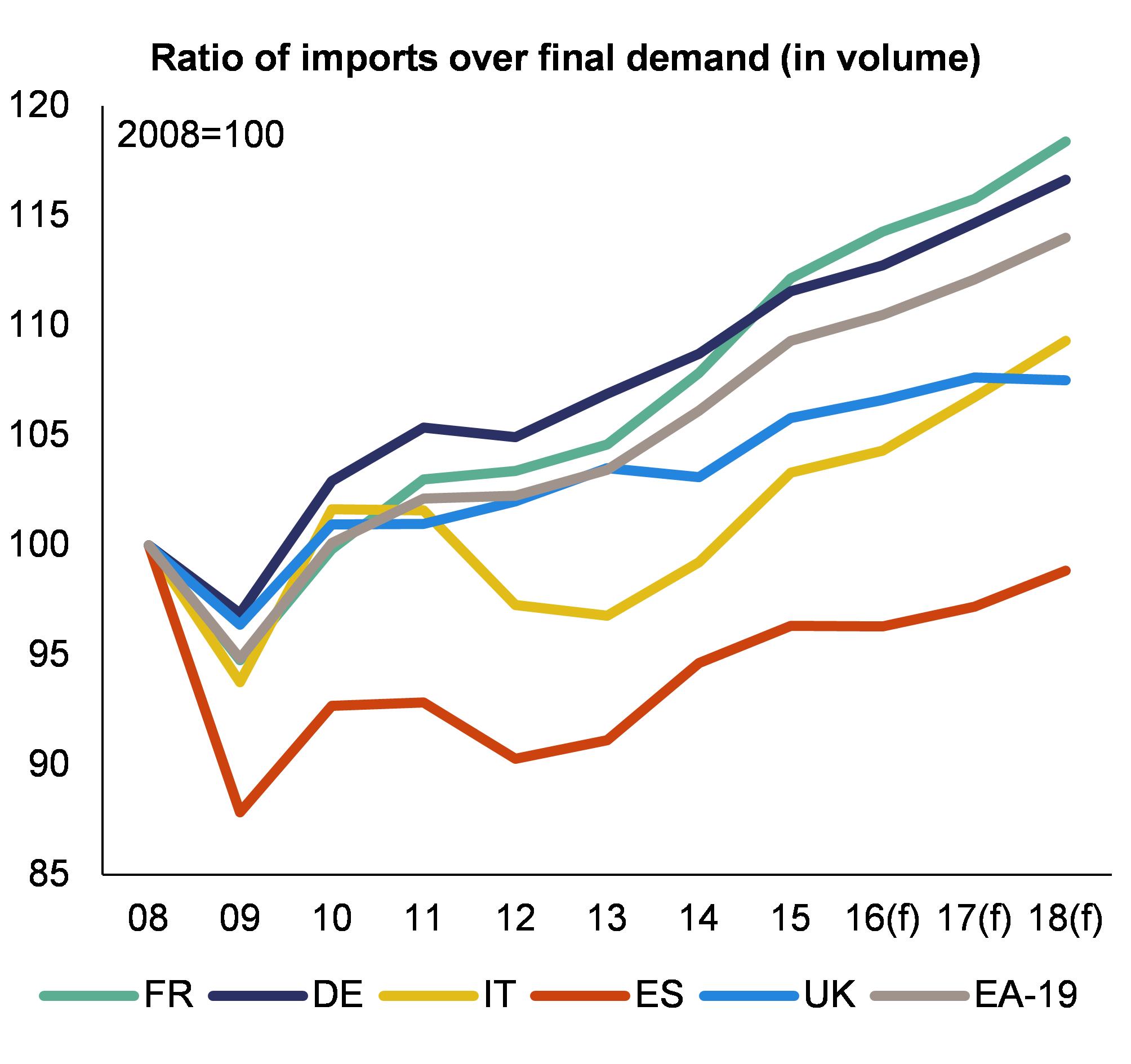

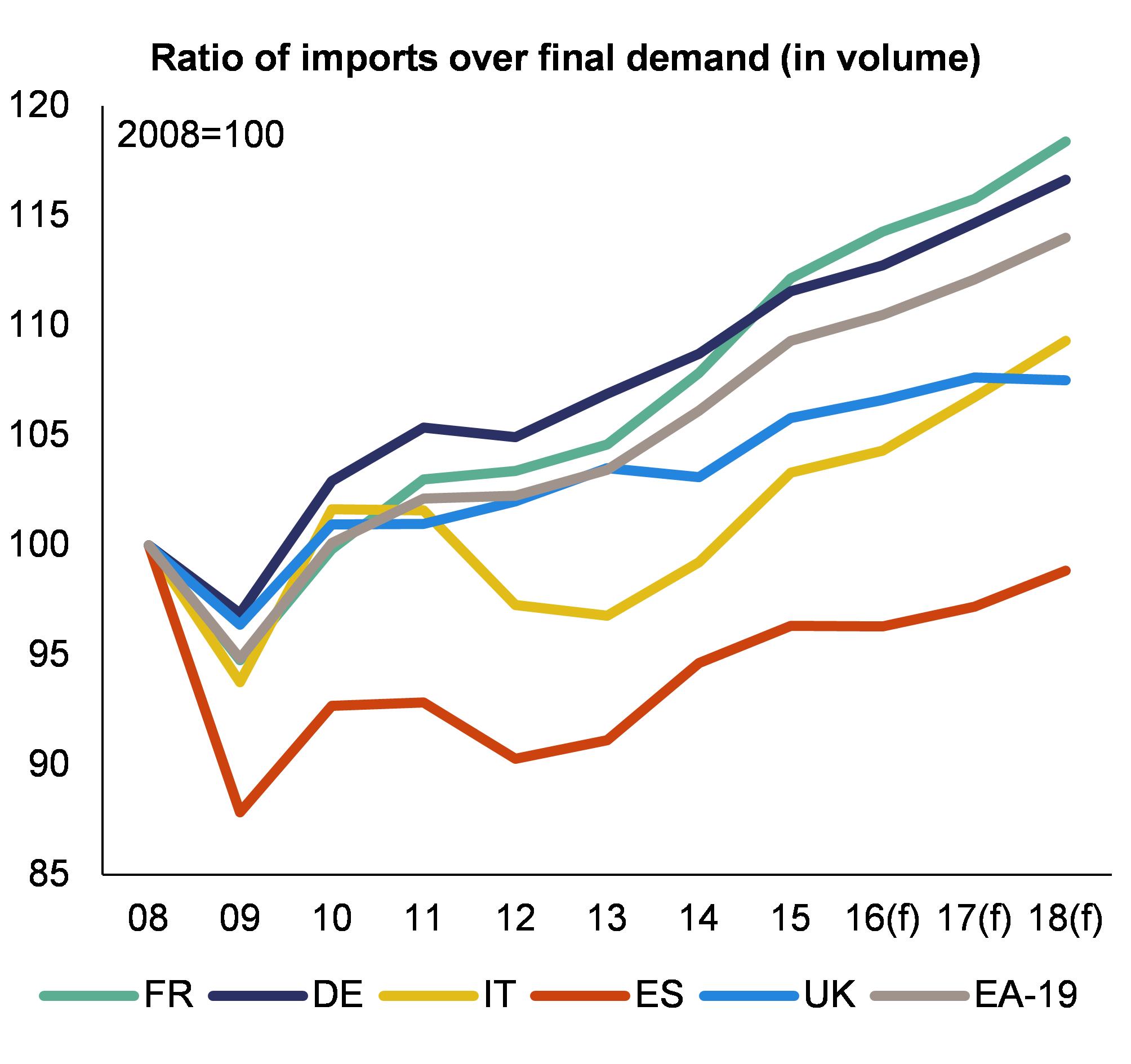

1.3.Import penetration in selected EU countries5

1.4.Trade in services – France6

1.5.Net lending/borrowing by institutional sectors – France6

1.6.Private debt in France and in the euro area7

3.1.Export market shares in value and in volume – France and euro area13

3.2.Real compensation per employee and productivity in France14

4.1.1.Difference in debt dynamics between France and the euro area21

4.1.2.Public debt projections of French public debt under different scenarios22

4.1.3.Changes in the composition of public expenditure24

4.1.4.Healthcare expenditure as a share of GDP in selected countries (2005-2015)24

4.1.5.Composition of total taxes on companies, 201526

4.1.6.Taxes on consumption as percentage of total taxation in 201427

4.2.1.Funding of non-financial corporations30

4.3.1.Unemployment rate in France, 2006-201532

4.4.1.Export market share breakdown for France – Goods39

4.4.2.French export performance – Goods39

4.4.3.Exports of selected sectors (in value) – France40

4.4.4.Share of export values per 5 categories of quality rank – France (% of total exports)40

4.4.5.Exports market shares in value and in volume – France41

4.4.6.Share of services in total exports in selected EU countries41

4.4.7.Real unit labour costs in selected EA countries (deflated by GDP deflator) – whole economy42

4.4.8.Breakdown of real unit labour costs in France – whole economy42

4.4.9.Sectoral breakdown of unit labour costs (average annual growth rate 2008-2015)43

4.4.10.Investment composition (% of value added) – whole economy44

4.5.1.Performance of France's innovation system - distance to EU innovation leaders and to EU average48

4.5.2.Efficiency of public funding of private R&D49

4.5.3.Competition per service sector and country50

4.5.4.Regulatory restrictions, France and EU50

LIST OF Boxes

2.1.Contribution of the EU budget to structural change12

3.1.Euro area spillovers17

4.1.1.Effects of a tax shift from taxes on production factors to indirect taxes28

4.3.1.Selected highlights: recent reforms to promote flexicurity in France38

4.4.1.Investment challenges and reforms in France46

4.5.1.Indebtedness of the State-owned network industries and implications for investment53

Executive summary

This report assesses France’s economy in the light of the European Commission’s Annual Growth Survey published on 16 November 2016. In the survey the Commission calls on EU Member States to redouble their efforts on the three elements of the virtuous triangle of economic policy — boosting investment, pursuing structural reforms and ensuring responsible fiscal policies. In so doing, Member States should focus on improving social fairness in order to deliver more inclusive growth. At the same time, the Commission published the Alert Mechanism Report (AMR) that initiated the sixth round of the macroeconomic imbalance procedure. The in-depth review, which the 2017 AMR concluded should be undertaken for the French economy, is presented in this report.

Economic growth is forecast to accelerate moderately. GDP growth declined slightly to 1.2% in 2016 from 1.3% in 2015, despite the acceleration in domestic demand, as net exports represented a drag on growth of almost 1 pp. of GDP growth. The Commission 2017 winter forecast projects French GDP to grow by 1.4 % in 2017 and 1.7 % in 2018. The recovery in exports is expected to rebalance growth away from private consumption and help sustain the recovery, although net exports are forecast to continue to be a drag on growth. Inflation is expected to moderate gradually, as the effects of past oil price increases fade. In the long term, growth is expected to remain moderate, as, in line with an EU wide trend, France’s potential growth has been eroded since the 2008 financial crisis, to 0.9 % in 2015.

Export performance remains subdued. Export market shares have stabilised since 2012 but exports barely grew in 2016. The trade deficit deteriorated in 2016 and is expected to widen further, as imports remain more vigorous than exports and oil prices rebound. While external sustainability is not a concern for France in the short term, the weak export performance weighs on growth prospects.

Cost competitiveness is improving without having fully regained past losses, while substantial improvements in non-cost competitiveness are still to materialise. The growth of unit labour costs has slowed down thanks to labour tax cuts and continued wage moderation, but low productivity growth prevents a faster recovery of France’s competitiveness. Low levels of product market competition and slow adoption of technology hamper productivity growth. Incentives for employers to hire on open-ended contracts have been introduced. In addition, derogations through firm-level agreements from branch-wide and general legal provisions are becoming more systematic. However, the minimum wage indexation mechanism has not been revised and the labour market remains segmented holding back the improvement of the labour force's skills. Finally, the tax burden for companies is high compared to other EU countries.

France's public indebtedness is high. The deficit is expected to decline below the threshold value of 3 % of GDP in 2017, but the pace of fiscal adjustment is slow as the adjustment of government spending proves difficult. This raises concerns about the durability of the deficit correction. The still comparatively high deficit coupled with the low inflation environment and low growth indicates that debt, expected at 96.4 % of GDP in 2016, continues to increase. More progress has been made on fiscal structural reforms: the sustainability of the pension system has been improved, territorial reform is allowing local government to make efficiency gains and setting-up the High Council of Public Finances has strengthened fiscal governance.

Unemployment is falling from the peak reached in 2015, while long-term unemployment continues to rise in contrast with the EU trend. After increasing steadily since 2008, unemployment started to fall, from 10.4 % in 2015 to 10.0 % in 2016, and is forecast to fall further in the coming years. Yet, unemployment for young people and low-qualified remains high and, as a percentage of total unemployment, long-term unemployment reached 44.2 % in the third quarter of 2016, contrary to the decreasing trend in the EU.

Overall, France has made some progress in addressing the 2016 country-specific recommendations. Substantial progress has been made in ensuring that labour cost reductions are sustained and in reforming the labour law. The 2016 Labour Act paves the way for a comprehensive review of the Labour Code and introduced measures aimed at improving firms’ capacity to adjust. However, no progress has been made on reforming the unemployment benefit system. Some progress has been made in improving the system of vocational education and training. Also, some progress has been made on removing barriers to activity in the services sector and in simplifying administrative, accounting and fiscal rules for companies. By contrast, limited progress has been made in reducing taxes on production and the corporate income tax, simplifying innovation policy schemes and boosting the savings identified by the spending reviews. No progress has been made in alleviating the effects on firms of size-related legal thresholds. Although the deficit is projected to decline below the 3 % Treaty threshold, the limited progress made in taking the required structural budgetary measures means that there are no fiscal buffers against unforeseen circumstances.

Regarding progress in reaching national targets under the Europe 2020 Strategy, France is performing well in decreasing greenhouse gas emissions, improving energy efficiency and reducing early school leaving. At the same time, more action is needed to increase the employment rate, R&D intensity, use of renewable energy, and to reduce poverty.

The main findings of the in-depth review contained in this report, and the related policy challenges, are as follows:

French exports continue to suffer from weak competitiveness. The increased specialisation of goods exports on a few sectors makes France’s export performance more vulnerable to negative developments in these sectors. Moreover, the quality of goods exports has declined slightly in recent years. Export market shares in services have been more resilient than those in goods since 2008.

Cost competitiveness has improved in recent years. Since 2013, unit labour cost growth has been lower in France than in the rest of the euro area, in particular thanks to measures taken to reduce the labour tax wedge, but accumulated past losses have not been made up for yet. Wage moderation continues, but low productivity growth is preventing cost competitiveness from recovering faster.

France performs well in terms of investment levels. Productive investment in machinery and equipment has started to pick up supported by fiscal measures. The quality of investment is however uneven. Investment in R&D is mainly in sectors whose relative weight is declining, and businesses are relatively slow to take up digital technologies. While barriers to investment are overall moderate, investment is highly concentrated around a limited number of larger firms. These investment patterns weigh on labour productivity and competitiveness and affect the long-term growth potential of the whole French economy.

The design of the tax system weighs on competitiveness. The high tax burden on companies may be an obstacle to investment and firms' growth. It is combined with a relatively low level of consumption taxes. The tax wedge on labour is being reduced but remains above EU average at the average wage. In addition, the complexity of the tax system may also be a barrier to a well-functioning business environment.

The French business environment is middle-ranking in comparison to major competitors. While the government has tried to simplify the regulatory burden for businesses, the latter are still faced with a high regulatory burden and fast-changing legislation. Size-related thresholds in social and tax legislation also continue to weigh on firms’ growth. Competition has improved in some service sectors, but is still weak in several sectors of major economic importance. Given the targeted scope of already adopted reforms, serious barriers remain in place.

High public debt coupled with low growth could be a source of significant risks for public finances in future. Short term sustainability risks remain low. In the long term, risks are also contained, notably due to pension indexation rules and favourable demographic developments compared to the rest of the EU. Nonetheless, there are significant consolidation needs in the coming years to bring down the public debt. The debt burden for the private sector is stabilising albeit at a high level. The combination of high public and private debt is an additional risk factor.

The expenditure-based consolidation strategy has relied mainly on declining interest rates and cuts in public investment. The already very high revenue-to-GDP ratio leaves little margin for further tax hikes, suggesting that further consolidation needs to be expenditure-based. However, it is unlikely that the low interest rate environment will prevail in the medium term and if productive investment is cut the economic potential could be harmed. In contrast, the spending reviews have identified a number of possible efficiency gains, most of which have not been implemented yet.

Its large economy and close integration with the rest of the euro area makes France a potentially significant source of cross-border spillovers. Structural reforms in France can have positive spill-over effects in other Member States. Model simulations suggest that product and labour market reforms or a growth-friendly tax shift in France can yield positive GDP effects for both France and for the rest of the euro area. These effects should remain in the long-term.

Other key economic issues analysed in this report that point to particular challenges facing France’s economy are the following:

Measures to reduce the cost of labour have had an effect on employment. The recent evaluations of the crédit d'impôt pour la compétitivité et l'emploi (CICE) highlighted its positive effect on employment, although an increase in its credit rate was not found to have an increased impact on employment. The Labour Act also aims to reduce labour market rigidities. Nonetheless, the French labour market remains segmented, while women and people from a migrant background continue to be affected by lower employment rates. The unemployment benefit system continues to be in deficit and its rules reinforce the labour market segmentation by favouring successive short periods of work.

Educational inequalities remain high and the vocational education and training system is not sufficiently adjusted to labour market needs. France performs well with respect to the Europe 2020 indicators concerning education. However, educational inequalities linked to socioeconomic background are among the highest in the OECD. The system of initial vocational education and training does not lead to a satisfactory integration of young people in the labour market. Access to the continuous vocational training system is uneven for different categories of workers.

France scores better than the EU average in relation to poverty, social exclusion and inequality. Social situation indicators show no major changes. Yet, some population groups remain more exposed to poverty, notably part-time workers and single-parent families. For very low income earners, access to affordable housing remains challenging.

The French national innovation system does not match the performance of Europe's innovation leaders. A high degree of complexity remains and overall coordination is a challenge. The discrepancy between the amount of public support granted and France's middling innovation performance raises questions about the efficiency of public support schemes.

1.

Economic situation and outlook

GDP growth

Economic growth is forecast to accelerate moderately. GDP growth declined slightly to 1.2% in 2016 from 1.3% in 2015, despite growth reaching 0.4% in the fourth quarter. Private consumption accelerated on the back of dynamic household purchasing power, while investment growth has been boosted by anticipation of the end of the over-amortisation scheme, a fiscal incentive for firms to invest. However, after an exceptional performance in 2015, export growth fell to 1.0% in 2016, due to several temporary factors, while imports remained relatively dynamic. As a result, net exports represented a drag on growth of almost 1 pp. of GDP growth in 2016. According to the Commission 2017 winter forecast, GDP is projected to pick up to 1.4 % in 2017 and 1.7 % in 2018 under the usual no-policy-change assumption (Graph 1.1).

|

Graph 1.1:Contributions to GDP growth (2010-2018)

|

|

|

|

Source: Commission 2017 winter forecast

|

The recovery in exports is expected to rebalance growth away from private consumption and help sustain the recovery, although net exports are forecast to continue to be a drag on growth. Private consumption is expected to decelerate in line with purchasing power, as the tailwinds from lower oil prices fade out. Also, the recovery in investment is gaining momentum, particularly in the construction sector. After the strong growth observed in 2016, equipment investment growth is set to moderate somewhat. However, the prolongation of the over-amortisation scheme until 14 April 2017, rising profit margins and easy financing conditions are expected to sustain robust growth rates. Export growth is expected to gradually normalise in 2017 and 2018, in line with the moderate recovery projected in French export markets. Meanwhile, imports are forecast to moderate somewhat in 2017, in a context of decelerating domestic demand, allowing for a more balanced contribution of net exports to GDP growth.

The unemployment rate has been declining since mid-2015, supported by the labour market measures adopted since 2013. Employment is forecast to continue growing at a sustained pace, supported by the ongoing economic recovery and by policy measures to encourage job creation by reducing the labour tax wedge (the Tax Credit for Competitiveness and Employment, the Responsibility and Solidarity Pact, and the Hiring Subsidy). Moreover, the emergency plan for employment announced in January 2016 is further decreasing the unemployment rate by providing training to unemployed people who subsequently do not appear as unemployed any more. Consequently, the unemployment rate is forecast to decline to 9.9% in 2017 and 9.6% in 2018.

Inflation is set to moderate gradually. Inflation rose sharply to 1.6% in January 2017, from 0.8% in December 2016. Overall, HICP is expected to average 1.5% in 2017, before declining slightly to 1.3%, as the strong positive contribution from recent oil price increases fades out and domestic price pressures increase only gradually.

Risks to the outlook are more balanced. Despite continued global uncertainty, risks to the forecast for France are less tilted to the downside than in the autumn. The improvement of labour market conditions could allow for a more significant drop in the household saving rate and thus stronger private consumption.

Potential growth

In the long term, growth is expected to remain moderate as potential growth has slowed since the 2008 financial crisis. Averaging 1.8 % from 2000 to 2008, France’s potential GDP growth declined to 0.9 % on average from 2009 to 2015 and is expected to pick up only moderately, to 1.3 % by 2018. While this decline has been observed in all major euro area economies, France is characterised by a stronger decline in total factor productivity (TFP) growth, while capital accumulation and labour force remained relatively dynamic (

). France’s decline in total factor productivity (TFP) growth, at −0.5 pp. from 2000-2008 to 2009-2015 (Graph 1.2), is larger than that of Germany (−0.3 pp.), Italy (−0.2 pp.) or Spain (+0.1 pp.). As a result, potential TFP growth in France has decoupled from Germany, although it remained higher than in Spain and Italy.

|

Graph 1.2:Potential GDP growth breakdown in France

|

|

|

|

Source: Commission 2017 winter forecast

|

The decline in total factor productivity growth contributes to the weak competitiveness and exacerbates the challenges linked to the high public debt. Although wage increases have moderated in recent years, the slowdown of labour productivity growth, largely due to a decline in TFP growth despite a continued increase in capital intensity, prevents a faster recovery of cost competitiveness (see Section 4.4). The decline in potential GDP also makes it more difficult for France to bring down its public debt without greater fiscal consolidation efforts (see Section 4.1).

Structural reforms are key to addressing the economic challenges associated with the declining potential growth. Labour and product market rigidities weigh on total factor productivity by hampering resource reallocation. Labour market segmentation limits the improvement of labour force’s skills (see Section 4.3). Moreover size-related social and tax thresholds and slow adoption of technology also weigh on total factor productivity growth (see Section 4.5). Finally, the tax structure is not growth-friendly.

Imports

Imports have been relatively more dynamic than final demand since 2008. The increase in import penetration reflects first and foremost general trends in world trade as a result of globalisation. However, import penetration has increased relatively more in France than in other major EU economies (Graph 1.3). This deterioration in the French market shares in the domestic market reflects the weak cost and non-cost competitiveness of the French economy.

|

Graph 1.3:Import penetration in selected EU countries

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|

France has been increasingly importing intermediate goods, which currently represent half of all imports of goods. The import content of its goods exports has also been growing over the years (from 33 % in 1995 to 39 % in 2009). Yet, French companies seem to be less integrated in global value chains, certainly less so than German companies. France's goods imports remain mostly downstream in the production chain (i.e. near final demand). Based on Andras 'upstreamness indicators', 46.3 % of French goods imports are near final demand against 39.7 % of German imports. Additionally, the ratio of domestic added value in French exports to foreign added value in its imports fell between 1995 and 2011 (from 51 % to 43 %), while again increasing in Germany (from 59 % to 67 %) in the same period.

|

Graph 1.4:Trade in services – France

|

|

|

|

Source: Eurostat – Balance of payments

|

In addition, the fast–rising imports of services are eroding the trade surplus in services. While still on the positive side, the trade balance in services declined by EUR 16 billion (0.7 % of GDP) from 2012 to 2015 to reach its lowest value since 1999 (Graph 1.4) (

). This decline occurred because, while exports of services grew fast (see Section 4.4), imports were growing even faster, accounting for the bulk of the change in the trade balance developments in recent years. Imports have been growing particularly fast in technical, trade-related and other business services since 2013, while the balance in tourism has deteriorated since 2014, presumably as a consequence of the recent terrorist attacks. Tourism is the service sector where France has the highest revealed comparative advantage (

). Thus, developments in this sector have a large impact on the overall trade balance in services. The trend in transport services is also negative: this sector has been running a deficit since 2013, mainly driven by a deteriorating balance in freight road transport and passenger air transport.

External position

The trade deficit reached a trough in 2011 at −2.6 % of GDP. The trade balance has been steadily improving since then and reached −1.4 % of GDP in 2015. A significant part of this improvement is due to lower oil prices, as the trade balance excluding energy products has been deteriorating again since 2013. As oil prices rebound, the total trade deficit is forecast to increase. According to the Commission 2017 winter forecast, the trade deficit is set to reach −2.3 % of GDP in 2018.

|

Graph 1.5:Net lending/borrowing by institutional sectors – France

|

|

|

|

Source: Eurostat, Commission 2017 winter forecast

|

Net borrowing of the nation is also set to deteriorate, to −2.4 % of GDP in 2018. In France, all institutional sectors except households were net borrowers in 2015 (Graph 1.5). The net lending of households remains insufficient to fully finance net borrowing by the general government and by corporations. In particular, France is the only major EU economy in which non-financial corporations are net borrowers, while the net borrowing of the public sector is higher than in the euro area as a whole. Over the forecast period, the deterioration in the net borrowing of the total economy stems from a fall in the net lending of households and a rise in net borrowing by corporations.

Private indebtedness

|

Graph 1.6:Private debt in France and in the euro area

|

|

|

|

Source: Eurostat

|

The level of consolidated private debt has steadily increased since 1998 to reach 144.3 % of GDP in 2015. Both household debt and non-financial corporation debt continued to grow at a relatively rapid pace throughout the crisis and beyond. By contrast, in the euro area, private debt has been falling since 2009, as a number of European economies have experienced significant deleveraging. As a result, private debt in France now exceeds the euro area average. While household debt remains below that of the euro area, the debt of French non-financial corporations exceeded the euro area average by 7.5 pps. in 2015. Non-financial corporation debt, combined with still low profitability, is a potential source of concern for France, should this trend persist.

Public finances

The general government deficit is projected to fall below the 3 % of GDP reference value in 2017, although its durable correction is at risk. According to the Commission 2017 winter forecast, the general government deficit is expected to decrease from 3.5 % of GDP in 2015 to 3.3 % in 2016 due to slow expenditure growth contained by low inflation and low interest rates. Based on the measures presented in the draft budgetary plan, the government deficit is expected to further decrease to 2.9 % of GDP in 2017. The structural balance is projected to improve by only 0.2 % of GDP in both 2016 and 2017, well below the recommended efforts in March 2015 (Council of the European Union, 2015). Moreover, at unchanged policy the deficit is projected to increase to 3.1 % of GDP in 2018.

The general government debt is projected to keep rising until 2018. The public debt-to-GDP ratio reached 96.2 % of GDP in 2015, compared with 92.6 % for the euro area on average. Such difference is expected to widen further in the coming years (see Section 4.1). Despite this trend, sovereign yields remain very close to historical lows driven by the expansionary monetary policy of the ECB. These low yields have resulted in interest expenditure decreases while preventing negative spillovers to the financial sector and the real economy.

Social developments

Modest economic growth has led to a stagnation of real household income in France. Between 2012 and 2015, real GDP per capita grew more slowly in France than in the EU and in the euro area (0.43 %, against 1.16 % in the EU and 0.81 % in the euro area). The poverty rate stabilised at 13.5 % in 2015 and the population at risk of poverty or social exclusion reached 17.7 % of the total population, below the level observed in the EU and the euro area. Also, the intensity of poverty, as calculated by national figures, has recorded a slight increase to 20.1 % in 2014 after having decreased from a peak of 21.2 % in 2012 to 19.8 % in 2013.

Income inequality remains relatively low in France compared to the EU average (

). It has slightly decreased since 2011, partly reversing an upward trend since 2007 (

). This decrease has been due to the tax benefit system, whilst market income inequality — that is inequality of incomes before taxes and transfers including pensions — has been rising since 2012 and is now somewhat above the EU average (

). Over the same period, the lower 10 % of income earners have benefitted from slightly better income developments than the median household — contrary to what happened between 2000 and 2012 — and their income gap with median earners is smaller than in many other EU countries (

). The French benefit system has also helped to reduce the risk of relative poverty, which is close to the EU average before social transfers and rather low after transfers (

). By contrast, households' net wealth (

) inequality is relatively higher than income inequality and was among the highest in the EU (ECB, 2016).

The significant rise in youth unemployment and long-term unemployment over the past 10 years, however, may increase the risks for the economic performance of France stemming from higher inequality. The segmentation of the labour market and inequalities in access to education (see also Section 4.3) play an important role in inequality outcomes and perceptions. This raises concerns about possible risks of hysteresis effects and further pain for low income earners.

|

|

|

Table 1.1:Key economic, financial and social indicators – France

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|

|

|

2.

Progress with country-specific recommendations

Progress with implementing the recommendations addressed to France in 2016 (

) has to be seen in a longer-term perspective since the introduction of the European Semester in 2011. As regards public finances, the general government deficit was reduced from 4.8 % of GDP in 2012 to 3.3 % in 2016 and was 1.5 pp. higher than in the rest of the euro area in 2016. In terms of fiscal structural reforms the sustainability of the pension schemes has been improved, the territorial reform has provided a framework to realise efficiency gains at local level and the fiscal governance has been strengthened with the setting-up of the High Council of Public Finances. However, less progress has been made concerning the identification of efficiency gains in public spending, raising concerns about the durability of the deficit correction.

Measures have been adopted to improve the functioning of the labour market. The cost of labour has been reduced, notably thanks to some fiscal measures (Sections 4.3 and 4.4). At the same time, the 2013 accord national interprofessionnel (ANI), the 2014 reform of the unemployment benefit system, and the Labour Act of 8 August 2016 have aimed to tackle some of the major rigidities hampering the good functioning of the labour market, although the social partners' take-up of the flexibility they offer is key in determining their impact on the labour market segmentation. Moreover, no ad-hoc increases of the minimum wage have been adopted since 2012, although its indexation mechanism has not been reviewed. The implementation of the 2014 reform of the vocational training system is ongoing.

The French authorities have taken some action to improve the middle-ranking business environment. A number of service sectors have been reformed and access to regulated professions has been eased in some cases. Efforts to reduce red tape for firms have been stepped up, notably through the multi-year simplification programme which has been in effect since 2013. The social dialogue law of 2015 and the 2016 budget law have attempted to soften the impact on firms’ growth of size-related regulations, but their scope has been limited overall.

The composition of the tax burden has somewhat improved, but distortive features remain and the potential for simplifying the tax system remains largely untapped. The total tax burden on companies increased between 2010 and 2013, with policy measures such as the CICE, the responsibility and solidarity pact and the phase-out of the C3S started to reverse the trend in 2014. These measures have been partly financed by an increase in VAT rates and environmental taxation, but the burden of taxation continues to fall less on consumption than it does in other EU countries. While some tax expenditures were phased out at the beginning of the period, overall the tax system has not been simplified, with tax expenditures rising as a share of GDP.

Overall, France has made some (

) progress in addressing the 2016 country-specific recommendations, which are all relevant to the macroeconomic imbalance procedure (MIP). Since the publication of the CSRs, few consolidation strategy measures have been taken on the expenditure side and tools to rein in spending growth have not been strengthened significantly. Progress in addressing CSR 1 has therefore been limited. The continued implementation of the CICE and the responsibility and solidarity pact (RSP) and the adoption in August 2016 of the Labour Act suggest substantial progress with CSR 2. Progress in implementing CSR 3 has been limited. Employment prospects offered by the initial vocational training system are not satisfactory, while the reform of the unemployment benefit system is still pending. Some progress has been made in improving the business environment (CSR 4). Competition has improved in some service sectors, some very preliminary steps are being taken to rationalise the innovation support system and the simplification of companies administrative, fiscal and accounting rules is ongoing. By contrast, no action has been taken since the end of 2015 to further reform size-related criteria in business regulations. Finally, progress in improving the efficiency of the tax system as called for by CSR 5 has been limited. The statutory corporate income tax rate is starting to be reduced in 2017 for some SMEs, but the turnover tax (C3S) has not been entirely phased out and no further steps have been taken to broaden the tax base on consumption. Apart from government plans to introduce a withholding tax for personal income tax, very little has been done to streamline the tax system or to broaden the tax base on consumption. The scrapping of taxes yielding little or no revenue continues to progress at a very slow pace while tax expenditures keep increasing in number and in value.

|

|

|

Table 2.1:Summary Table on 2016 CSR assessment

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|

|

|

3.

Summary of the main findings from the MIP in-depth review

The 2017 Alert Mechanism Report (European Commission, 2016b) called for further in-depth analysis to monitor progress in the unwinding of the excessive imbalances identified in the 2016 MIP cycle. The selection was motivated by the fact that France was identified with excessive imbalances in spring 2016 after an in-depth analysis, so that a new in-depth review is needed to assess how these imbalances evolve. The identified excessive macroeconomic imbalances related to a weak competitiveness and a high and increasing public debt, in a context of low productivity growth. Other vulnerabilities were identified, including as regards the segmentation of the labour market, the innovation capacity, the limited efficiency of public spending and the complex tax system, which weighs significantly on production factors, as highlighted in the Review of progress on policy measures relevant for the correction of macroeconomic imbalances (European Commission, 2017c). These vulnerabilities have cross-border relevance.

Analyses included in this Country Report provide an In-Depth Review (IDR) into how the identified imbalances have developed. In particular, IDR-relevant analysis is found in the following sections: sources of imbalances related to public debt are covered in section 4.1; the situation of the financial sector in section 4.2; sources of imbalances related to competitiveness in section 4.4; and vulnerabilities associated with market performance of the services sector in section 4.5. Potential spillovers to the rest of the euro area are discussed in box 3.1.

Imbalances and their gravity

French export performance has deteriorated significantly over the past 15 years. Since 1999, its export market shares have fallen by 36.8 % in value (Graph 3.1), compared to 20.4 % for the euro area as a whole. In volume, the decline is also significant (−25.4 %, against −11.0 % in the euro area). This loss in export market share, linked to a deterioration of both cost and non-cost competitiveness, has weighed on growth outcomes. At the same time, external sustainability is not a concern for France in the near term as its net international investment position remains contained at −16 % of GDP (after −17 % in 2014).

|

Graph 3.1:Export market shares in value and in volume – France and euro area

|

|

|

|

Source: Eurostat, IMF

|

Cost competitiveness deteriorated markedly from 1999 to 2013. Unit labour costs increased at a faster pace in France in both nominal and real terms. From 1999 to 2008, the loss of cost competitiveness was largely due to containment of unit labour costs in the rest of the euro area, in particular in Germany. From 2008 to 2013, there was a disconnection between the trend in nominal unit labour costs and the GDP deflator in France, in a context of low productivity growth. This resulted in a further decline in the relative cost competitiveness in that period, this time for domestic reasons.

Weak non-cost competitiveness has also weighed on export performance. Despite reform efforts, the French business environment continues to be characterised by a relatively high regulatory burden. Complex labour regulations, high corporate tax rates and a complex tax system continue to weigh on firms. Rigidities persist in a number of sectors and prevent the downward adjustment of tariffs to the detriment of downstream industries that use these services. Increased size-related social and fiscal obligations give rise to threshold effects and discourage firms from growing with implications for labour productivity and competitiveness. The low profitability of non-financial corporations also weighs on France’s non-cost competitiveness, through its impact on the quality of investment. Although corporate investment is relatively high and supported by favourable macroeconomic and framework conditions, it tends to be concentrated in less productive purposes thereby weighing on productivity growth.

The high public debt-to-GDP ratio is a major source of vulnerability and compounds the risks stemming from the weak competitiveness of the French economy. High public debt weighs on growth prospects by crowding out productive public expenditure and requiring a higher tax burden. However, in the current context of also high (though stable) private sector debt, still weak growth, low inflation and heightened uncertainty, not only is public deleveraging more difficult, but also high public debt makes France more vulnerable as it might give rise to negative feedback loops to the real economy and the financial sector should a new wave of negative shocks materialise. Moreover, sustainability risks in the medium term are high, partly due to the projected increase in age-related expenditure. Given the size of the French economy, such a situation could also entail potentially negative spillovers to the rest of the euro area (see also Box 3.1 on euro area spillovers).

Evolution, prospects and policy responses

Export performance remains subdued. Export market shares have stabilised since 2012 but export growth stalled in 2016 and is expected to fall well short of both world trade and French export market growth. The current account deficit rose to −1.2 % of GDP in 2016 according to annualised monthly data (after −0.2 % in 2015) and is expected to deteriorate further. Taking into account the relative position of the French economy in the business cycle, the cyclically-adjusted current account deficit is worse than the headline indicator.

Cost competitiveness is improving without having fully regained past losses. The labour tax cuts and continued wage moderation have allowed a slowdown of labour costs, but low productivity growth is preventing cost competitiveness from recovering faster. In 2015, unit labour costs rose by 2.5 % over 3 years and 0.9 % once the Tax credit for competitiveness and employment (CICE) is taken into account, compared to 2.1 % in the rest of the euro area. Productivity picked up slightly in 2015 (rising by 0.8 %), but remained below both long-term trends and the euro area average. Part of the decline in productivity growth can be explained by the measures aimed at boosting employment growth, which often focused on low-qualified employment. However, potential growth has also declined since 2008.

|

Graph 3.2:Real compensation per employee and productivity in France

|

|

|

|

Source: Eurostat

|

Despite recent reforms, substantial improvements in non-cost competitiveness are still to materialise. Although France has improved its overall regulatory performance, its business environment continues to be middle-ranking. In the Doing Business survey (World Bank, 2017), France fell from 28th to the 29th position (out of 190 economies assessed), and ongoing reforms do not appear to be significantly improving business perceptions. Regulatory bottlenecks continue to affect firms’ economic performance. As regards investment, equipment investment is slowly gaining ground supported by fiscal incentives for amortisation, but R&D investment continues to be concentrated in sectors of declining economic importance as measured by their share in total value added (motor vehicles, computers, electronics, and pharmaceuticals), which has implications for the long-term growth potential of the whole economy. Non-financial corporate profit margins have somewhat recovered since 2013, in part due to the labour tax wedge cuts and to lower oil prices, but they remain below their pre-crisis level.

Some action has been taken to improve competitiveness. France has taken some measures to address the rigidity of the wage setting process through the labour law adopted in 2016, which provides for company-level majority agreements on working time. The impact of this law on the competitiveness of the French economy, however, will depend on its implementation and the extent to which the social dialogue at firm level will be able to transform the new legal possibilities granted by law into tangible action. Also, while no ad-hoc increase in the minimum wage has been adopted since 2012, no revision of its indexation mechanism has been undertaken and the French labour market remains both segmented and insufficiently linked with the vocational training system. As regards the business environment, competition has been improved in a number of services sectors, including legal professions, retail trade and passenger transport services. Some effort is also being made to simplify firms' administrative, fiscal and accounting rules through the multiannual simplification programme. However, the tax system remains a drag on competitiveness despite recent reforms. Corporate taxes are still high and France has abandoned the phase-out of the last tranche of the turnover tax (C3S), while the tax base on consumption remains narrow.

Public debt is projected to keep rising due to still high deficits. The general government debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to increase to 97 % of GDP in 2018, which implies growing divergence in indebtedness vis-à-vis the euro area due to a slower pace of deficit reduction than in the rest of the EU (see Sections 1 and 4). The budgetary strategy, which is to meet just the nominal headline deficit targets, basically relies on favourable macroeconomic conditions and interest rate windfalls. Such a strategy is risky as, on the one hand, it does not ensure durable correction of the excessive deficit and, on the other hand, there are significant consolidation needs in the coming years to bring down the public debt.

Spending dynamics prove hard to contain. Despite France's efforts to contain spending increases in recent years, the consolidation measures in the 2017 budget law have been scaled down compared to the plans included in the April 2016 stability programme. Overall, the current primary expenditure ratio, this is expenditure minus the interest burden and public investment, has continued increasing since 2012. While spending reviews identified a considerable amount of potential saving measures, the budgetary measures adopted as a result of the spending reviews have had a limited yield and have not contributed so far to significantly improve public spending efficiency. Furthermore, as demonstrated in last year's country report, in key areas of public policy, e.g. pensions and healthcare, France achieves good results but other Member States reach same or better outcomes at a lower cost. In turn, the tax burden is high, with the tax system remaining too complex and heavily reliant on production factors, which reins in growth.

High sustainability risks show up in the medium term mainly due to the high initial deficit and debt ratio. Despite the high debt ratio, short term sustainability risks are considered as low (see section 4.1). France is able to issue long-term debt at very low rates also bearing in mind the expansionary monetary policy stance of the ECB. However, the high initial deficit and debt and the projected increase in age-related expenditure over the next 15 years lead to a significant sustainability gap in the medium term.

Overall assessment

France faces important sources of imbalances related to a weak competitiveness and high and increasing public debt, in a context of low productivity growth. The substantial improvement in export performance in 2015 has proved short-lived. The current account, close to balance in 2015, is expected to deteriorate significantly in the coming years. Cost competitiveness is improving but has not regained past losses. Wage moderation continues, but the decline in productivity growth prevents a faster recovery of France’s cost competitiveness. The product market reforms of the last years and continued efforts to reduce red tape on firms could contribute to an improvement of non-cost competitiveness but there is still substantial scope to increase market competition, simplify regulation, and reduce the tax burden for companies. Public debt remains high and increasing, which represents a major imbalance, as it weighs on growth prospects and reduces the fiscal space to offset adverse macroeconomic shocks. Public debt reduction is thus important to help improve overall French macroeconomic performance and avert medium-term sustainability risks.

Policy measures have been taken in recent years in particular to reduce the labour tax wedge. However, policy challenges remain, in particular as regards the regulatory impediments to firms’ growth, the initial and continuous system of vocational training and the reform of the unemployment benefit system. In addition, the spending review has not delivered the expected results to address the growing public debt-to-GDP ratio.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(Continued on the next page)

|

|

Box (continued)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 3.1:MIP Assessment Matrix (*) – France 2017

|

|

|

|

|

|

(Continued on the next page)

|

|

Table (continued)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|

|

|

4.

Reform priorities

4.1.

Public finances and taxation

General government debt sustainability (

)*

Debt dynamics between France and the rest of the euro area continue to diverge although the increase in French debt is slowing. The Commission 2017 winter forecast puts the general government debt in France at about 8 pp above the euro area level. The higher general government deficit in France explains most of this difference, although real economic growth, interest expenditure and stock-flow adjustments have partly compensated for the higher primary deficits in recent years (Graph 4.1.1). The lower interest expenditure has contributed significantly to reducing the deficit and debt since 2011 and this is expected to continue over 2016 and 2017. However, the declining interest rate burden is expected to come to a halt once interest rates and inflation normalize. Therefore, without further consolidation and sustained growth, the reduction in the public debt-to-GDP ratio is not guaranteed and debt dynamics between France and the euro area will continue to diverge.

The high public debt ratio does not seem to pose significant sustainability challenges in the short term. The short-term sustainability indicator S0 (

) does not flag any significant risk overall, although the short-term fiscal sub-index flags high risk due to the high level of gross financing needs, of the primary deficit and of public debt. In spite of the weaknesses revealed by the fiscal sub-index of the S0 indicator, the rating outlook for French government debt is AA stable for the three major rating agencies.

|

Graph 4.1.1:Difference in debt dynamics between France and the euro area

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission, 2017 winter forecast

|

Sound debt management strategies reduce the short term risks. All French debt is denominated in euro so there is no currency risk. Moreover, the average maturity of debt instruments has increased to nearly 7.5 years, reflecting longer issuance maturities, which allows securing low interest rates over the coming years. While the share of short-term debt has declined, it remains relatively high (8.3 % of total). The investor base is diverse and broadly equally distributed between residents, the euro area and the rest of the world. While holdings by foreign investors have slightly declined to 60 % of total French debt, the high share held by non-residents could be a source of vulnerability. However, investor appetite is still high. Traditional investors in search of higher yields have turned to riskier investments, but are expected to readjust their holdings once interest rates increase. French debt is a sought-after investment for capital and liquidity requirements reasons and diversification purposes, as it offers the possibility of holding nominal and inflation linked bonds issued in euros.

However, France's public debt faces high sustainability risks in the medium term. The debt sustainability analysis for France shows that in the baseline scenario assuming no policy change public debt would be roughly stable at some 97 % of GDP until 2021. However, it would begin to rise again thereafter, to reach 103.5 % of GDP in 2027, the last projection year. This public debt shows that the fiscal effort is insufficient to offset the increasing costs of an ageing population and the unfavourable snow-ball effect, mainly due to the rising interest rate burden. Based on these projections, the S1 sustainability indicator, which measures sustainability risks at horizon 2031, flags a high medium-term risk. This indicator implies that a cumulative gradual improvement in the French structural primary balance of 4.7 pps. of GDP, relative to the baseline scenario, would be required over 5 years to reduce the debt ratio to 60 % of GDP by 2031.

The high medium-term sustainability risks are primarily due to high initial indebtedness and unfavourable initial budgetary position. Specifically, 2.8 pps. of the required fiscal adjustment would be due to debt ratio's distance from the 60 % reference value, 1.5 pps. to the unfavourable initial budgetary position (defined as the gap to the debt-stabilising primary balance) and the remaining 0.3 pps. to the projected increase in age-related public spending. Public debt projections are especially sensitive to interest rate developments: a 1 pp. increase in the interest rate of newly issued bonds and rolled-over debt, other things being equal, would lead to a 6-point increase in the public debt-to-GDP ratio (around EUR 190 bn.) compared to the baseline projection by 2027 (Graph 4.1.2), thereby aggravating the sustainability gap significantly.

Despite medium-term challenges, sustainability risks appear contained in the long run. The S2 indicator, which measures sustainability risks at an infinite horizon, calculated under a baseline no-fiscal policy change scenario, indeed points to a relatively small required fiscal adjustment (0.8 pp. of GDP), to ensure that the debt ratio remains on a sustainable path over the long run horizon. This is primarily due to the projected fall in age-related spending from the late 2030s (contribution of -1.0 pp. of GDP to S2), offset by the unfavourable initial budgetary position (1.8 pp. of GDP). It is the projected decrease of public pension expenditure, in particular, that drives down ageing costs (- 1.7 pp. of GDP), given the reforms implemented in this area in the past. However, the adjustment implied by the S2 indicator could lead to debt stabilising at relatively high levels. Consequently, the indicator has to be treated with caution for high-debt countries in relation to the SGP requirements. Moreover, long-term risks could arise under more adverse scenarios, such as in the lower total factor productivity growth scenario for pension expenditures, or the Ageing Working Group risk scenario for healthcare and long-term care expenditures.

|

Graph 4.1.2:Public debt projections of French public debt under different scenarios

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission, Debt Sustainability Monitor 2016.

|

Favourable demographic dynamics and past reforms mean that pension expenditure is projected to decline in the long run. Pension spending in France is among the highest in the EU, at 14.9 % of GDP versus 11.3 % in the EU in 2013, and so is the benefit ratio, 51.3 % in France versus 46.9 % in the EU, defined as the average pension as a share of the economy-wide average wage. Pension expenditures are projected to remain broadly constant at a high level in the medium-term and to decline only in the long term. A relatively moderate increase in the old-age dependency ratio (by 14.9 pps.) represents a relatively favourable demographic trend compared to other EU countries that allows containing pressure on pension expenditure. The average effective exit age from the labour market (61 in 2014), which is low in a EU perspective, is also projected to increase progressively to 63 in 2060 as a result of recent reforms described in the 2016 Country Report (European Commission, 2016c). However, the savings envisaged from the foreseen increase in the retirement age might be partly offset by rises in other types of public expenditure, such as invalidity or unemployment-related expenditure in the short term. Despite the favourable long-term financial prospects of the French public pension system, some special regimes that allow early retirement continue to weigh negatively on the balance of the pension system.

Quality of fiscal consolidation*

Given the already high revenue ratio, the government adopted an expenditure based consolidation strategy. Between 2012 and 2017, the deficit is projected to decline from 4.8 % to 2.9 % of GDP according to the Commission 2017 winter forecast (ibid.). Over the same period, the revenue ratio is projected to increase by 1.3 % of GDP to 53.3 % of GDP. This ratio is forecast to be 8.5 % of GDP higher than the EU average in 2017, with the high tax burden weighing on economic activity (see the taxation sub-section, below). The expenditure-to-GDP ratio is set to decline by 0.6 pp over 2012-2017, helped by lower interest rates (Graph 4.1.3). A quarter of the planned deficit reduction would thus be due to changes in expenditure, in particular from the reorientation towards an expenditure-based consolidation strategy since the budget 2015. However, at 56.2 % of GDP in 2017, the expenditure ratio would remain 9.7 % of GDP higher than in the EU.

The largest contributor to the decline in the expenditure ratio is the interest burden (-0.8 pp over 2012-2017), with broadly neutral effects on economic activity. Interest rates are projected to increase somewhat in the short term but remain low by historical standards. However, the low interest rate environment is not expected to prevail in the medium term. For example, in the ageing projections, the interest burden is projected to gradually rise from 1.8 % of GDP in 2017 to 3 % of GDP by 2025.

Expenditure growth was also contained by a reduction in public investment. The second largest contributor to the fall in public expenditure is public investment which declined by 0.6 % of GDP over the same period. Public investment cuts typically have a stronger negative effect on economic activity than cuts in other expenditure items, with a multiplier for public investment of 2.5 points in the long run. However, the economic impact of the decline in public investment has likely been less strong than suggested by the normal multipliers (

). Public investment was mainly cut by local authorities, who are responsible for more than 50 % of total public investment, and has mainly affected the least efficient projects, thereby leaving the existing public capital stock unaffected. Local investment displays a clear cyclical pattern linked to the local electoral cycle, but this time round the cycle seems to have been amplified by the cut in the global State transfers to local authorities of 0.5 % of GDP since 2014. Nonetheless, while in a first phase the cut in global dotations has impacted investment. Since recently, operational expenditure of local authorities started declining from a growth rate of 3.0 % in 2013 to 0.9 % in 2015.

Primary current expenditure increased due to a strong increase in subsidies. The primary current expenditure ratio is projected to increase from 49.0% of GDP in 2012 to 50.1% of GDP in 2017. This increase in the expenditure ratio once the interest burden and capital expenditure is filtered out, puts into question to durability of the expenditure containment strategy. One important driver of spending has been an increase in subsidies, due to the introduction of the crédit d'impôt pour la compétitivité et l'emploi (CICE), which is a tax credit on the salary mass of firms introduced in 2014, focused on the lower end of the wage scale. The effect of the increase in subsidies on economic activity is closer to a targeted cut in social contributions, which is a relatively efficient way of strengthening economic activity as opposed to other types of subsidies.

The spending reviews were scaled back in 2016. In place since 2015, the spending reviews identified a fraction - less than 2 % - of the overall planned expenditure savings of EUR 50 billion over the period 2015-2017. Based on the first wave of reviews, savings with a total yield of EUR 325 million were included in the 2016 budget. The second review exercise took place in 2016, but the proposals in the draft budget 2017 relied on measures identified already in the 2015 spending review exercise. The planned savings would yield EUR 400 million. In general, it appears that only a subset of the savings identified in the spending reviews appear in the budget. This is partly because more than 50 % of the spending reviewed in 2016 concerned local authorities, and they are autonomous in managing their budgets. In general no mechanism exists to ensure that the different administrations act on the recommendations of the spending reviews.

|

Graph 4.1.3:Changes in the composition of public expenditure

|

|

|

|

Source: Ameco database, European Commission

|

Efficiency and effectiveness of the health system (

)*

The French health system performs well in a European perspective. The population enjoys high life expectancy at birth (82.3 years in 2015, one of the highest in the EU). The healthcare system performs well in terms of overall accessibility as it is characterised by fee-for-service payment of doctors, unrestricted freedom of choice for patients and a traditional focus on hospital based care.

However, healthcare spending is relatively high in a European perspective. French health expenditure was at 11 % of GDP in 2015 which is similar to the level of expenditure in Germany (Graph 4.1.4). In the long run, the increase in health care expenditure is expected to be relatively contained in comparison to other EU Member States although health care expenditure would remain one of the highest in the EU. In the light of cost pressures, an ageing population and the increased prevalence of chronic diseases, a more coordinated use of care is being encouraged. In other countries, but to some extent also in France, this is done through greater use of primary care and more effective referrals from family doctors to steer demand to other types of care and organise appropriate and cost-effective channels of treatment.

|

Graph 4.1.4:Healthcare expenditure as a share of GDP in selected countries (2005-2015)

|

|

|

|

Source: OECD Health statistics 2016

|

A range of reforms has been implemented in recent years to keep health care expenditure under control. Key reforms included improvements in access to health insurance for those most vulnerable, improvements in hospital efficiency, better data collection and monitoring and better control of pharmaceutical expenditure, greater use of primary care and improvements in care coordination from primary to secondary care. In tandem with the reforms, the enforcement of the healthcare expenditure norm, the ONDAM (Objectif National de Dépenses d'Assurance Maladie), has allowed for a contained growth of health expenditure in recent years.

Low spending on prevention could weigh on the overall efficiency and effectiveness of the French health system. France spends 1.9% of total health resources on prevention, versus average spending on prevention of 3% in the EU. Low spending on prevention can lead to higher healthcare costs in the longer run, certainly as it is accompanied by low vaccination levels for certain preventable diseases and comparatively high prevalence of risky behaviour such as alcohol and tobacco consumption.

Fiscal frameworks*

The fiscal framework has been strengthened in the last few years, although weaknesses still remain. Since the founding in 2012, the High Council of Public Finances (HCFP) (

), the systematic positive bias in the macroeconomic forecasts underpinning the draft budgets has disappeared. In September 2016, the HCFP issued a more critical opinion than in previous years on the macroeconomic scenario underpinning the 2017 draft budgetary plan (Haut Conseil des Finances Publiques, 2016). There is no formal mechanism in place to reconcile divergent views between the HCPF and the Ministry of Finance, and in the that case, the Ministry of Finance did not adjust the macroeconomic scenario underpinning the 2017 DBP following the HCFP's opinion .

Although the expenditure norms are an effective means to control expenditure, they are becoming more difficult to meet. The norms are becoming more ambitious every year as expenditure growth rates for the respective spending categories decrease. At the same time, new spending announcements are projected to increase spending on a permanent basis, whereas the savings allowing the norms to be met are across-the-board spending cuts. Consequently, in 2017 the ceilings for the norms had to be raised for State and health expenditure. All these developments point to the limits of the existing rules, as they become harder to obey without taking structural measures. Furthermore, the cut in transfers from the State to local authorities has been reduced, leading to an upward revision of the indicative spending norm for local authorities (ODEDEL). At the same time, no correction mechanism or alert committee exists to oversee the ODEDEL and prevent local expenditure overruns. Finally, the ONDAM and the norm of the state cover about half of public expenditure.

Taxation*

The tax wedge on labour has fallen substantially at the lower end of income distribution, but remains high at the average wage. Between 2012 and 2015, the tax wedge was reduced by around 1 ppt. at the average wage and by more than 3 pps. for workers earning 50% of the average wage. This change in trend is mainly due to the introduction of the CICE and the RSP. The tax wedge for very low income earners (50% of the average wage), at 31.6%, was below the EU average of 32.7% in 2015. For income earners at the average wage, the tax wedge, at 48.7%, remained above the EU average of 40.7% and one of the highest in the EU, which may undermine the functioning of the labour market.

Although employers' social security contributions are falling, they are still relatively high. At the average wage, France has the highest employers' social security contributions in the EU as a share of total labour costs paid by the employer, which explains the relatively high tax wedge. This partly stems from the social security system being financed through employer's contributions, which is only partially the case in other countries. High employers' social security contributions are also conducive to a large tax burden on companies.

The high level of taxes weighing on companies represents an obstacle to private investment and hampers companies' growth (European Commission, 2016e). The effective average corporate tax rate was the highest in the EU in 2016 (38.4 %) (ZEW, 2016). French corporate income tax combines a high nominal rate (38 % in 2014 including the surcharge, the highest in the EU), and relatively little revenue as a share of GDP (2.7 % of GDP in 2014, against 2.4% in the EU, for a nominal rate of 22.9% for the same year) because of generous tax credits and relatively low profit margins. Finally, the debt-equity tax bias in corporate financing remains the highest in the EU in 2016. Due to a less favourable tax treatment, investments financed by equity need to earn 5 percentage points more in return than investments financed by debt to yield the same after-tax return (ZEW, 2016).

Other taxes on production (

) are particularly high (Graph 4.1.5). They stood at 3.1 % of GDP in 2015 (

), above Italy (2.0%), Spain (1.1%) or Germany (0.4%), although it is generally accepted that such taxes are particularly distortive since they disregard the economic performance of the firm and directly affect profit margins. These taxes have not been curbed by recent policy measures and have continued to increase in GDP terms since 2011, in spite of the phase-out of part of the turnover tax (C3S). Local-level taxes account for roughly two thirds of such taxes and have been increasing as a share of GDP since the reform of local government taxation. However, this increase in tax revenue has stemmed mainly from a base effect in recent years (Cour des Comptes, 2016b).

|

Graph 4.1.5:Composition of total taxes on companies, 2015

|

|

|

|

Source: National Tax Lists 2016 and AMECO

|

Capital taxation in France is high compared to other Member States and favours "lower-risk" products investments like housing and deposits over "riskier" investments like shares. At 10.5 % in 2014, France's ratio of taxes on capital-to-GDP was the third highest in the EU, above the EU average (8.2 %). The overall tax burden on capital increased by 1.3 pp. between 2010 and 2013, then stabilised in 2014. Furthermore, capital taxation favours investment in housing and life insurance. A reduced rate of 7.5 % applies to life insurance products and implicit rents on the main property are taxed according to rental values which have not been updated since the 1970s, while real estate capital gains are not taxed. By contrast, capital gains on securities are taxed according to the progressive personal income tax regime. Furthermore, specific tax regimes such as the full exemption of savings products (e.g. Livret A), the deductibility of interest from the corporate income tax basis or the capital gain tax create a relative distortion between fixed-income instruments (and especially deposits) and shares. Such distortions negatively affect growth, investment and financial stability. To counterbalance some of these discrepancies, the tax system also includes a high number of tax rebates and specific schemes to encourage investment in innovation, SMEs and start-ups; one more has been introduced by the 2017 finance law.

The relative complexity of the tax system is a barrier to a well-functioning business environment. France has a high tax burden coupled with many tax breaks, reduced rates and various tax schemes to address specific objectives. It results in detailed rules and derogations that may increase compliance costs and may create uncertainties (France Stratégie, 2016b; Michel Taly, 2016). Total tax expenditure is sizeable in France at more than 3 % of GDP (CICE excluded). Indicators commonly used to measure the complexity level of a tax system show a contrasting picture for France. In 2015, the country scored well in terms of the number of hours needed to comply with taxes (World Bank, 2016). However, the administrative cost to tax authorities of collecting taxes, as a percentage of tax collected, was above the EU average in 2013 (latest data available) (OECD, 2015b). Looking at trends, tax complexity has increased in recent years. The General Tax Code (Code général des impôts) expanded by 61 % (in number of pages) between 2002 and 2015 (Cour des Comptes, 2016c).

The burden of taxation continues to fall less on consumption than it does in other EU countries. In 2014, France ranked 27th in the EU in terms of tax revenues from consumption as a percentage of total taxation (24.1 %) below neighbouring countries such as Germany, Italy, or Spain, and the Nordic countries (Graph 4.1.7).

The VAT system is characterised by middle-ranking standard rate and low reduced rates applied to a large base. France applies a standard rate (20 %) which is middle-ranking as compared with neighbouring countries (above Luxemburg (17 %) and Germany (19 %), but below Belgium (21 %), Italy (21 %) and Spain (21 %)), but relatively low reduced rates – the 5.5 % reduced rate is lower than that of neighbouring countries. In addition, reduced rates are applied to a large base, (European Commission, 2016c). In 2014, the revenue foregone from applying reduced rates represented 10 % of the theoretical total VAT liability which would have resulted from a perfectly flat system, above the 5.3 % EU average (CASE, 2016). Furthermore, VAT compliance is worsening (CASE, 2016).

|

Graph 4.1.6:Taxes on consumption as percentage of total taxation in 2014

|

|

|

|

Source: Taxation Trends in the European Union 2016

|

In terms of environmental taxation. recent tax increases have not yet closed the gap with the EU average. Revenues from environmental taxes steadily increased from 2009 onwards to reach 2.1% of GDP in 2014 (ranking 23rd in the EU), the level that it had back in 2004. This remains below the EU-28 average (2.5%), and, as a percentage of total taxation (4.5%), France ranked 28th in the EU in 2014. Environmental taxation is set to continue to rise as the carbon tax will increase significantly until 2030. In addition, excise duties on diesel have increased in 2017 (by 0.01 EUR per litre) while they have decreased on petrol by the same amount. As a result the taxation gap between diesel and petrol is closing but still remains.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Furthermore, VAT compliance is worsening. The compliance gap, which provides an estimate of revenue loss due to fraud, tax evasion, bankruptcies and miscalculations, has increased to 14 % of total VAT tax liabilities in 2014, against 12 % in 2013. Since 2011, the compliance gap in France has increased by 5 pps. of the total VAT tax liabilities (CASE, 2016). This is higher than in Spain (9 %) or Germany (10 %), but lower than in Italy (28 %).

4.2.

Financial sector

The French banking sector seems relatively sound. Domestic banks represent more than 90 % of the French banking sectors total assets. The four largest French banking institutions are considered of global systemic importance by the Financial Stability Board. Overall, French banks appear somewhat more profitable than their counterparts in the euro area, with a return on equity which amounted to 6.8 % in 2015 compared to 4.4 % on average in the euro area. French banks rely more than their peers in the euro area on non-interest rate income given the importance of investment banking activities. They also benefit from relatively low impairments. Moreover, French banks are able to re-price liabilities more easily to lower interest rates than their euro area peers whereas asset repricing is occurring more slowly than in the rest of the euro area (see Box 1.3 in IMF 2016) implying that margins have suffered less than for euro area peers from the low interest rate environment. With a Tier 1 ratio of 13.8 %, the capitalisation of French banks appears broadly in line with that of their euro-area counterparts (14.2 %) and slowly improving over time. Their loan portfolio is less risky, with non-performing loans representing a stable 3.5 % of the total portfolio in Q1-2016 (vs. 5.6 % in the euro area). Substantial progress has been made over the last

year in terms of stable funding, with a loan-to-deposit ratio close to 102.7 % in 2015. Lower dependence on short-term wholesale funding is an asset when interbank markets experience difficulties.

In an environment of low net interest income across the euro area, banks' profitability is under pressure from a structurally high cost-to-income ratio. The interest rates set by the government on regulated savings instruments like the Livret A or the "Plan Epargne Logement" appear relatively high and squeeze banks' interest margins. This is especially true for the latter, where the interest rate is fixed for the whole term of the contract and currently stands at 2.5 % for the existing stock of "Plan Epargne Logement". The overall impact on banks' profitability is however limited as deposits make up a relatively small share of total liabilities (see above). In order to address their high cost-to-income ratio, one of the highest in the EU, banks are expected to continue investing in digitalisation and to close branches, although no massive lay-offs seem to be planned in the short-term.

There has been some correction in house prices since 2011. Housing prices fell by 9 % between their peak in the third quarter of 2011 and the first quarter of 2016, although prices stabilised in recent quarters. The correction observed since 2011 has led to some correction in house prices with respect to fundamentals. However, valuation metrics continue to signal some risk of overvaluation. Compared to the historical trends, price-to-rent and price-to-income ratios suggest an overvaluation of more than 20 %. Based on rental prices per square meter, French house prices do not seem overvalued compared to other euro area markets (see Dujardin et al., 2015). Moreover, another metric based on the relationship between house price, total population, housing investment, real disposable income per capita and the real long-term interest rate suggests an overvaluation of only 3 %. The latter metric is more strongly linked to supply and demand fundamentals and confirms the qualitative analysis also made in the 2015 Country Report (European Commission, 2015c). More specifically, structurally strong demand supported by positive demographic trends and the absence of excess housing supply together with prudent credit supply by banking institutions suggest that downward price pressure is limited and further downward adjustment, if any, will be very gradual.

Mitigation measures exist to contain the impact of house price developments on the financial sector. The decline in house prices since 2011 led to a moderate rise of the loan-to-value ratio to 85 % for new loans and to 68 % for the existing stock. However, credit standards are based on revenue rather than housing value and more than half of housing loans are secured by a guarantee from a bank or an insurer, which reduces the importance of the value of the collateral when assessing credit risk. Therefore, in line with the analysis in the Country Report 2015 (ibid.), a moderate adjustment in house prices does not seem to pose a considerable risk to the financial sector. In contrast to residential real estate prices, commercial real estate prices have significantly increased over the past few years. As a result, the Haut Conseil de Stabilité Financière (HCSF) asked banks, insurance companies and investment funds to perform stress tests. Depending on the results, the authorities could consider macro-prudential measures where appropriate.