EUROPEAN COMMISSION

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Brussels, 25.5.2016

SWD(2016) 166 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

IMPACT ASSESSMENT

Accompanying the document

Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on cross-border parcel delivery services

{COM(2016) 285 final}

{SWD(2016) 167 final}

Annex 1: Procedural information

Lead DG

The lead DG is the Directorate General for the Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs.

Agenda planning and Work Programme References

The Agenda Planning Reference is 2015/GROW/027.

The cross-border parcel initiative forms part of the Digital Single Market Strategy, adopted in May 2015 and, as one of the ten priorities for the Juncker Commission, part of the Commission's 2015 and 2016 Work Programmes.

Organization and Timing of the Impact Assessment and Inter-service Steering Group

The Directorates General participating in the Inter-service Steering Group chaired by the Secretariat General included:

The Secretariat General

The Legal Service

DG Communications Networks, Content and Technology

DG Competition

DG Economic and Financial Affairs

DG Employment and Social Affairs

THE Joint Research Centre

DG Justice and Consumers

DG Mobility and Transport

DG Taxation and Customs Union

Meetings of the Inter-service Steering Group were held on:

8 April 2015. The background to the project, the roadmap and the consultation were discussed.

22 July 2015. The problem definition, problem tree and approach to the IA were discussed.

25 September 2015. A draft of the impact assessment was discussed.

15 October 2015. The draft impact assessment was discussed.

8 January 2016. An updated impact assessment was discussed.

4 March 2016. The RSB opinion and draft regulation were discussed.

Consultation of the RSB

The Regulatory Scrutiny Board of the European Commission assessed a draft version of this Impact Assessment on 2 December and issued its opinion of negative on 4 December. The changes made in response to their recommendations are set out below.

|

RSB recommendation

|

Changes

|

|

The purpose of the initiative should be clarified

|

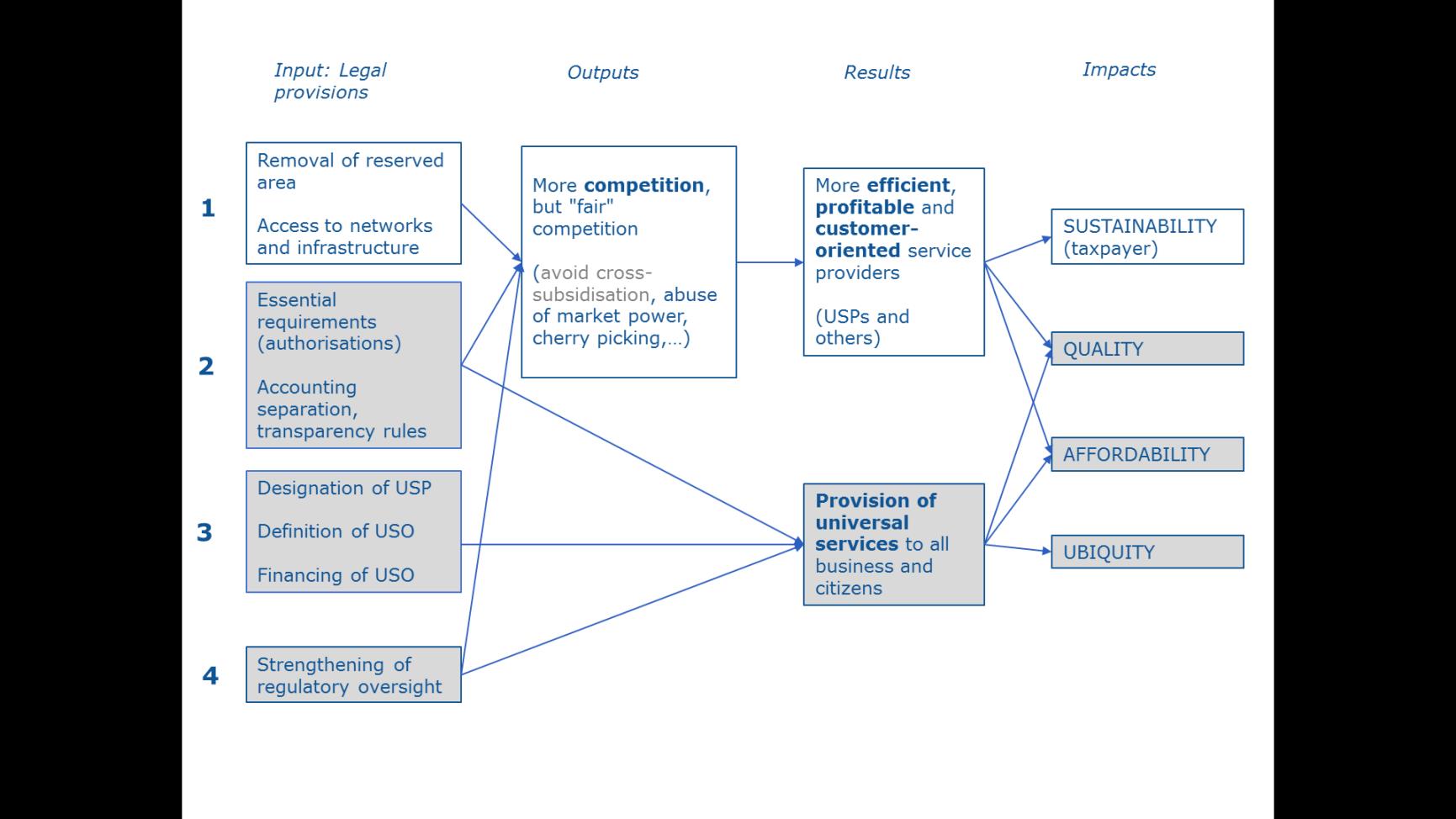

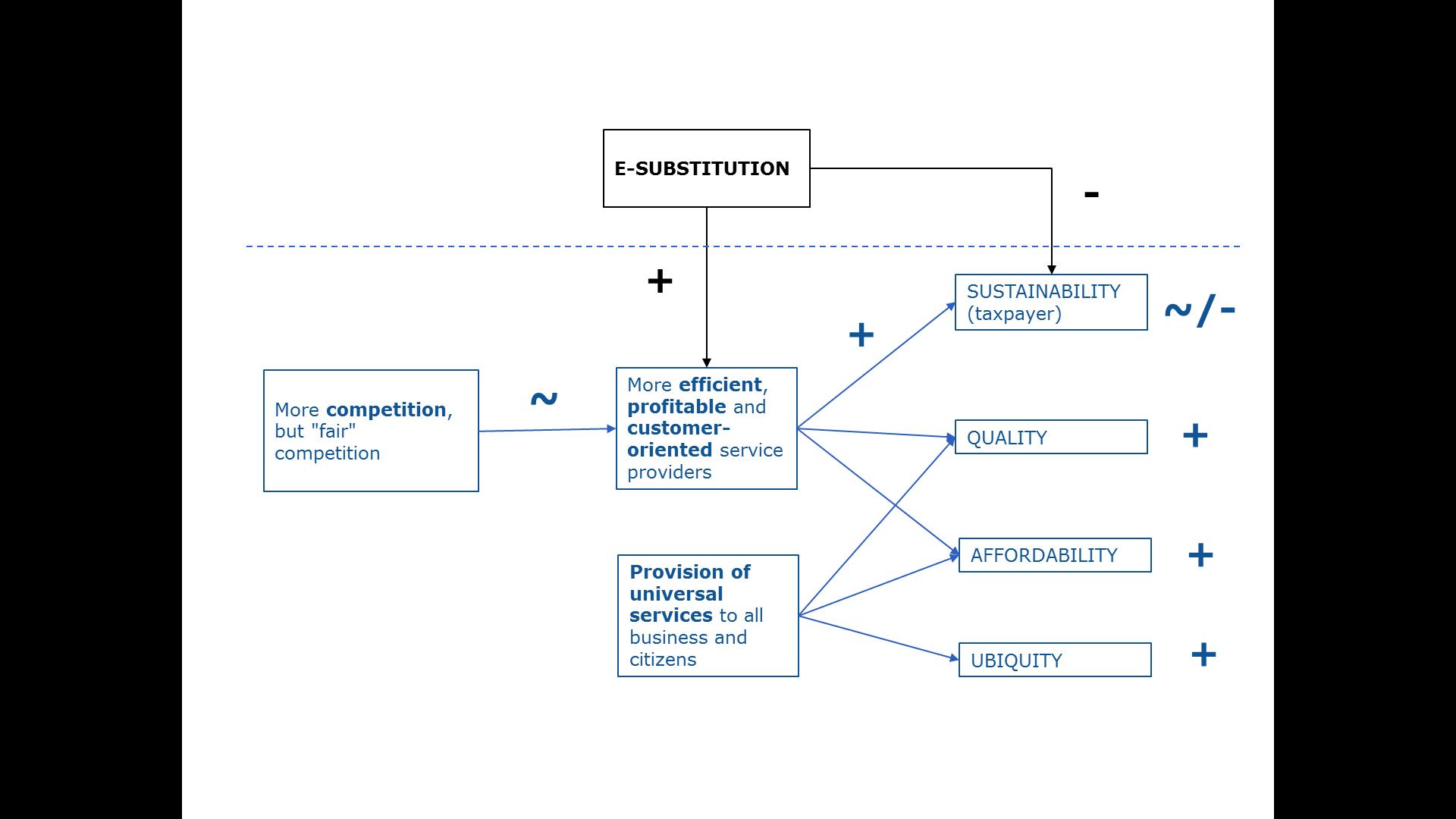

Section 3.2, figure 3 and figure 4 have been updated to clarify the purpose of the initiative and the policy options have been streamlined.

|

|

The baseline scenario should be further developed

|

The baseline scenario is more comprehensively explained in sections 1.3, 4.1 and 6.1.

|

|

More information about the evidence base and added value of the initiative is needed

|

Evidence has been added from studies by the University of St Louis, University of Antwerp, the Joint Research Council; a report from the Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications (BEREC) and the European Regulators Group for Postal Services (ERGP).

|

|

The assessment of the impacts should be clarified using evidence

|

The studies about have been used alongside evidence from the public consultation to clarify the expected impacts. Tables 2 and 3 have been revised with a comprehensive explanation given in Annex 8.

|

|

The report should present the links between different sections and explain price setting mechanisms and the role of regulators.

|

Cross references to different sections have been included and more information about the regulatory framework added in section 1.2.2 and details about how prices are set in sections 1.1.1.

|

The Regulatory Scrutiny Board issued a second opinion of positive on 2 March 2016. The changes made in response to their recommendations are set out below.

|

RSB recommendation

|

Changes

|

|

The proposals can be better justified by explaining better the extent to which the objectives would be attained.

|

The impact of the policy options on the objectives has been explained more clearly (sections 5 and 6). The baseline scenario (i.e. what would happen in the absence of the proposals) is more comprehensive.

|

|

The content of the options should be better explained.

|

The options have been described in more detail in section 4.

|

|

The report should better assess the expected impacts of the proposed options.

|

Section 5 (analysis of impacts) is more comprehensive, as it section (6) comparison of the options, and the ratings have been explained.

|

|

Key assumptions for cost calculations should be better presented. The market structure should be presented.

|

The administrative burden calculation, including uncertainties and limitations has been explained further (section 5.9). More detail on the a market structure is included in 1.2.1

|

Evidence and Studies

Consumer market study on the functioning of e-commerce and internet marketing and selling techniques in the retail of goods (2011)

This study was commissioned by the Executive Agency for Health and Consumers, acting on behalf of the European Commission's Directorate General for Health and Consumers. The study was conducted by Civic Consulting with support of TNS Opinion and Euromonitor International. Research was conducted between December 2012 and February 2011 in the EU27 and included an online customer surveys, a price collection survey, interviews and surveys of business associations, consumer protection authorities, consumer organisations and European Consumer Centres. The study examined why e-commerce had developed more extensively in some Member States than others and whether e-commerce was delivering its full potential in consumer welfare and the obstacles and remedies for this.

Lower online prices and greater online choice can increase EU consumer welfare. The study estimated that the total welfare gains for EU consumers would amount to 204.5bn EUR per year (equivalent to 1.7% of EU GDP) if there was a single EU consumer market in the e-commerce of goods and a 15% share of internet retailing instead of 3.5% (the level at the time of the study). Two thirds of welfare gains were due to more choice, which is greater across borders. In contrast to more recent surveys, this study found that it was not common to use mobile phones for online shopping.

Worries about delivery, returns or replacing a faulty product were the mains concerns for both cross-border and domestic purchase: the top five concerns were related to this for cross-border purchases and the top four for domestic products. Long delivery times were the main concern for cross-border purchases (40% of cross-border online shoppers) and also the main problem that customers actually encountered (28% of those shopping online in their own country and encountering problems and 26% of those shopping online cross-border encountering problems). The quality of delivery services also affected how willing consumers were to shop online. Although price comparison websites were valued, they often lacked adequate information about delivery costs and timings. Security of payment and personal data were the measures most likely to increase consumer confidence when buying online. Recommendations to address this 'missing potential' of e-commerce included reducing costs and time for cross-border deliveries and increasing convenience and quality; encouraging retailers of offer goods to consumers in other Member States, for example through an information platform and sharing best practice; promoting faster and improved complaint handling and customer service; and creating effective redress mechanisms for cross-border e-commerce.

http://ec.europa.eu/consumers/archive/consumer_research/market_studies/docs/study_ecommerce_goods_en.pdf

Study on intra-community cross-border parcel delivery (FTI Consulting – December 2011)

This 2011 study was commissioned by the European Commission, Directorate General for the Internal Market and Services to gain a deeper understanding of the EU cross-border parcel delivery market in terms of structure, regulatory environment and conduct of its participants. The project included significant data collection work, including from national regulatory authorities, delivery operators, e-retailers, the Postal User Group and relevant representative bodies. Desk research and other sources of public data (such as Eurobarometer surveys) were also used).

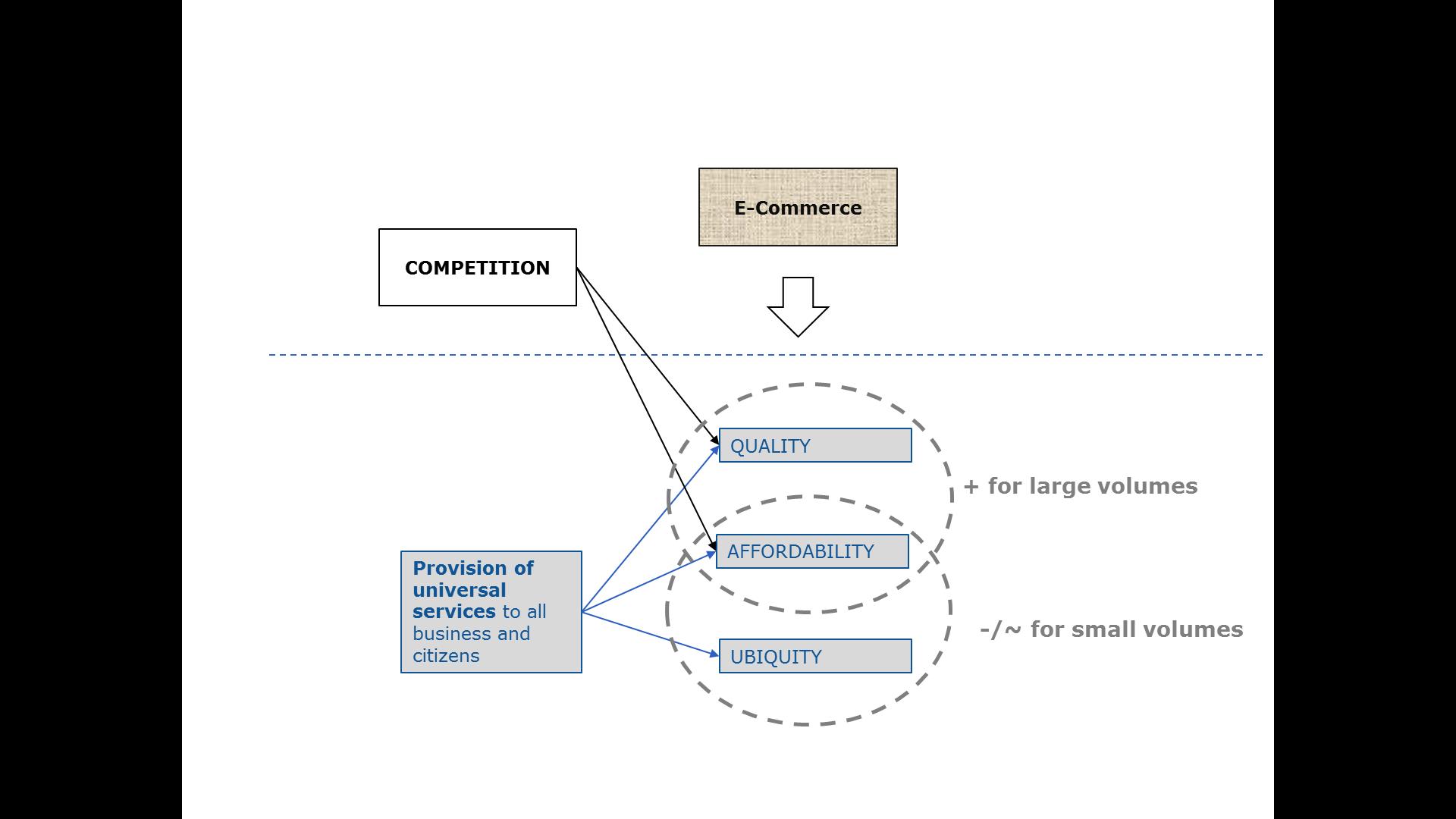

The study found that only 9% of EU consumers and 18% of e-retailers used cross-border e-commerce. E-commerce was estimated to account for 5% of retail turnover, 1% of which was generated cross-border. Participation of small retailers in cross border e-commerce was lower than this, with the potential to grow significantly. The study concluded there were three sets of barriers to e-commerce that are directly related to delivery and which affected smaller retailers in particular: prices, quality of service and information. The study also noted that in some member states competition for small infrequent senders of parcels was increasing, smaller customers tended not to take advantage of such deals and use national postal operators instead, due to lack of knowledge of and confidence in the alternatives. There was a two tier market in which larger firms were generally able to enjoy competitive markets, unlike individual consumers and smaller firms, particularly in low density countries or areas where the universal service provision is essential. The lack of confidence was exacerbated by the lack of information about the quality of service for cross border delivery.

Regulation of cross-border parcels was also found to be lacking, with consequences for pricing, particularly affecting smaller senders. Three factors were thought to contribute to the lack of regulation: differences between the parcels included in the universal service obligation (USO); potential lack of data on volumes, quality, costs and termination rates; and scare cooperation between NRAs regarding the regulation of cross border parcels. The study recommended that terminal rates should be disclosed to NRAs (but not made public).

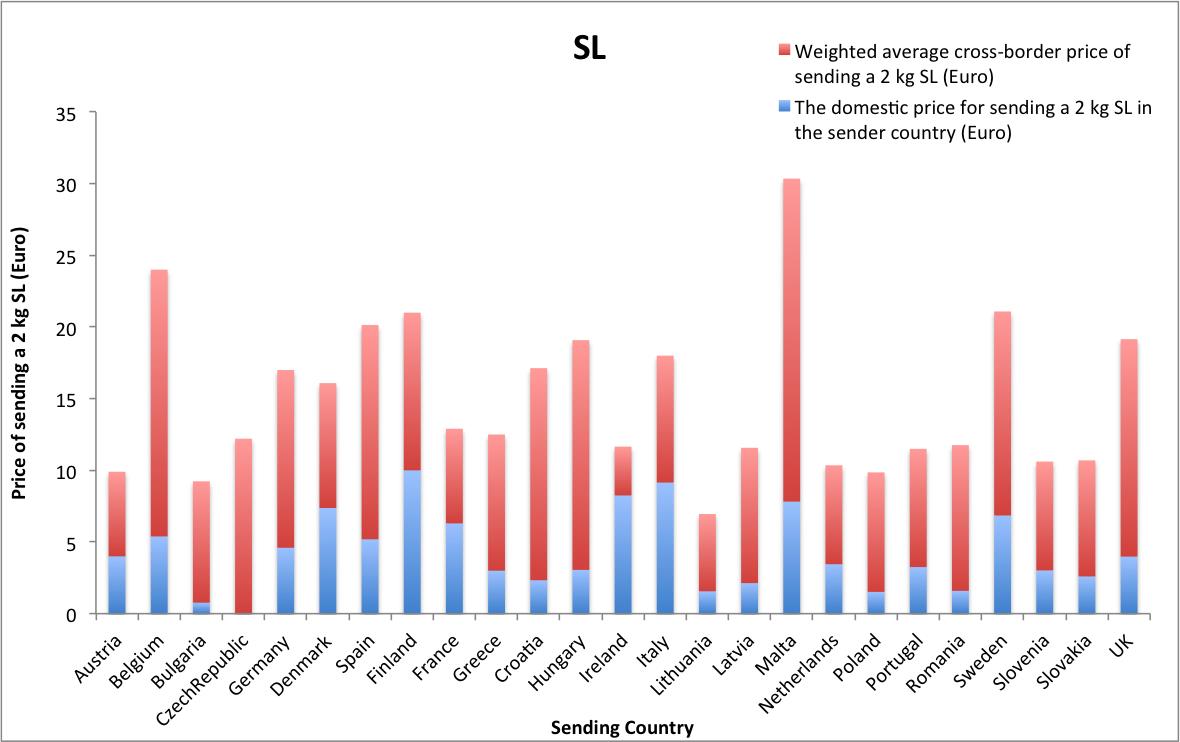

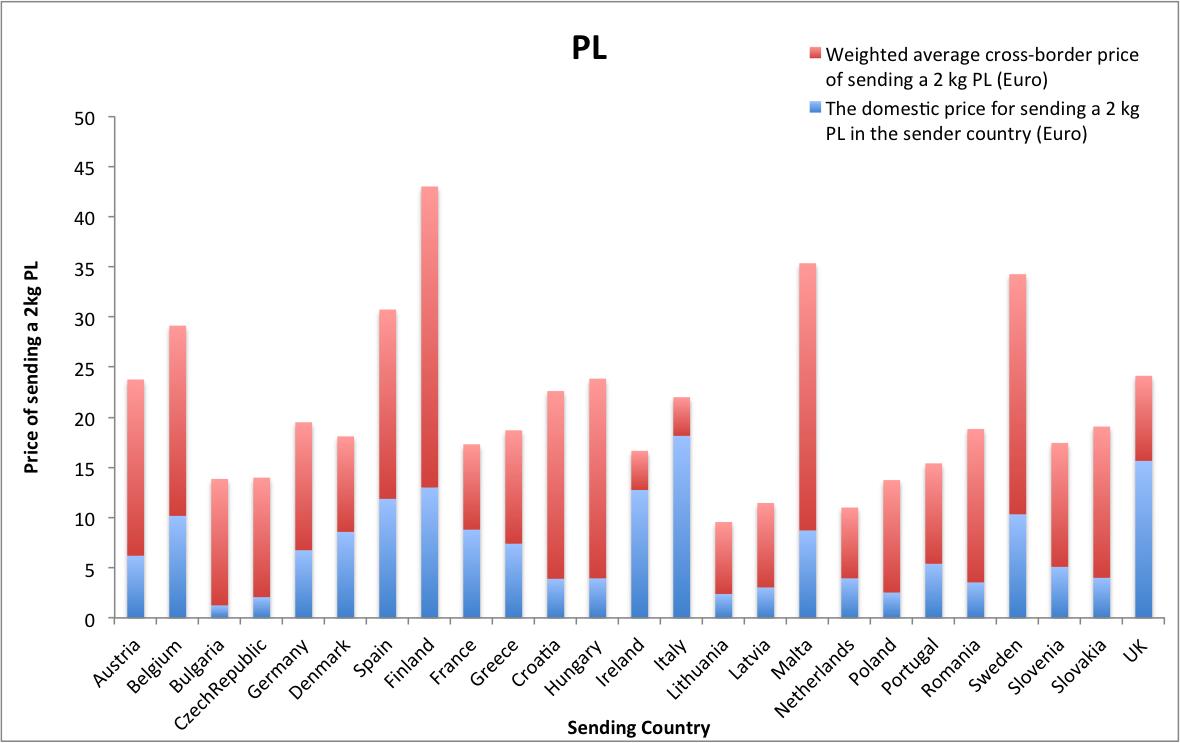

The Study estimated that parcels paid for at 'individual' prices made up around 20% of the market. On average cross-border prices were twice as high as domestic benchmark prices, and three to five times higher for packets.

Recommendations included removing information barriers through rapid implementation (by Member States) of the Consumer Rights Directive and campaigns to promote awareness of consumer rights and cross-border delivery options; removal of quality of services barriers though publication of quality of service standards and introducing cross-border quality measurements for parcels; and removing price barriers though clarifying the scope of the USO, NRAs enforcing Articles 12 and 13 of the Postal Services Directive (including through appropriate cost allocation procedures) and sharing information to gain an understanding of cross border markets.

http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/post/doc/studies/2011-parcel-delivery-study_en.pdf

AT Kearney: Europe's CEP Market, Growth on New Terms

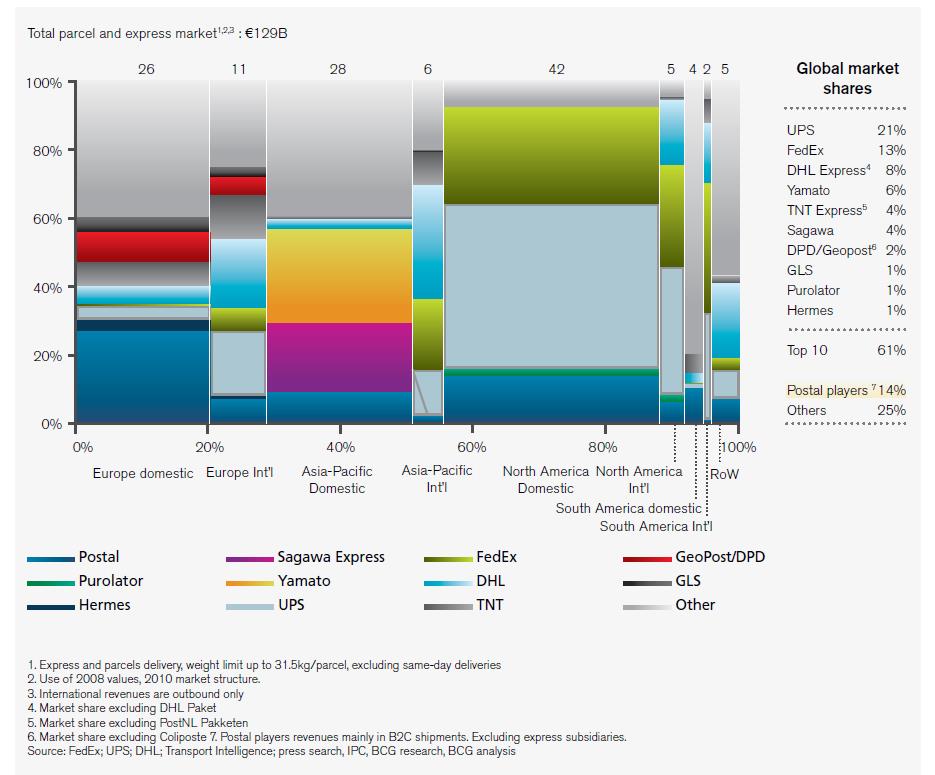

This study was produced by the consultants A. T. Kearney and was based on over 500 interviews with industry executives and research into company performance in 16 European countries, including Russia, Norway, Switzerland and Turkey as well as EU Member States. Express products were defined as products including the fastest possible service with guaranteed delivery times and standard products as offering day certain and deferred delivery times. Packages weighing up to 2,500kg were included.

The study found that volumes grew faster than revenues between 2009 and 2011 for both the international and domestic markets. International traffic did however grow faster than domestic (volume growth of 10% between 2009 and 2010 and 8% between 2010 and 2011). International services accounted for 30% of revenues and 9% of volumes in 2011. From 2008 customers had moved away from more expensive express services towards cheaper standard services as a way of reducing costs during the economic downturn. Most markets therefore had stronger growth in standard parcel markets than express and "express" operators were noted to be moving more into the growing segments of B2C and standard parcels.

Subsequent research (Europe's CEP Market: Steady Growth Begins to Shift) by A. T. Kearney found that growth in volumes continued to outpace revenues up to 2013, growing by 5% between 2012 and 2013 compared to 4%. Growth in international shipments outpaced domestic ones (8% increase compared to 5% increase). Growth in standard (rather than express) parcels was still strong in many countries. Domestic volume growth was expected to slow slightly by 2016 as shippers and service providers seek to minimise the number of returns.

http://www.atkearney.tw/documents/10192/649916/Europe%27s+CEP+Market+-+Growth+on+New+Terms+%283%29.pdf/6613e0d5-1620-4694-b52c-26f8ef1b4ead

http://www.atkearney.tw/documents/10192/5544202/Europes+CEP+Market%E2%80%B9Steady+Growth+Begins+to+Shift.pdf/b63e4b9e-8979-4d54-a7bb-0ee9cf6008df

E-commerce and delivery - Study on the state of play of EU parcel markets with particular emphasis on e-commerce - Copenhagen Economics (July 2013)

Commissioned by the then DG Internal Market, for this study Copenhagen Economics conducted qualitative and quantitative research covering over 3,000 e-shoppers, 70 e-retailers, 61 delivery operators and 26 NRA to complement existing literature and statistics on the EU parcel market.

The study noted significant differences in the levels of e-commerce between Member States, citing Eurostat data that showed 82% of internet users in the UK bought something online in 2012 compared to 11% of internet users in Romania. On average 90% of e-shoppers engaged in domestic e-commerce compared to 30% for cross border and 85% of e-commerce shipments are domestic. A survey among 3,000 e-shoppers conducted for the survey found that delivery problems were a key reason for not buying online and were responsible for 68% of abandoned shopping carts. The main cause of abandonment was delivery charges that shoppers felt to be two high, the second was delivery times that were considered to be too long. 38% of shoppers were dissatisfied with one or more aspects of the delivery of their most recent online purchase, with 26% dissatisfied with returns, 21% unsatisfied with delivery prices and 16% unsatisfied with the speed or quality of delivery service.

This study estimated that the market share of universal service providers (USPs) was around 35% for the delivery of B2C packets and parcels, rising to 54% in the more mature e-commerce markets. For specifically e-commerce deliveries, international integrators handle slightly more than USPs with 42% compared to 40%, and increasing to a 50% market share for the integrators for cross-border shipments.

The four most important elements of delivery were identified as low prices; delivery to the home address; electronic delivery notifications and track and trace; and convenient return options, with surprisingly few differences between countries. E-retailers preferences were also similar although they had more diverse preferences for delivery points.

In terms of information provision, the study observed that a lack of adequate information and high search costs often caused e-retailers to remain with the same delivery provider and one in five e-retailers responding to their survey was only aware of one delivery operators although on average there were three to four alternatives. Solutions proposed included a European trustmark for delivery, an extension of the Consumer Rights Directive to include requirements for delivery information on e-retailers websites, and information campaigns.

The quality of service (returns options, notification, track and trace etc) was found to be better for domestic e-commerce than for cross-border, although some services were only available in parts of a country and in some cases there were delivery options on offer by delivery operators that were not offered by e-retailers. The main reasons for the lack of services were found to be low volumes and interoperability problems.

Prices observed for cross-border delivery were often three to five times higher than for domestic delivery. E-retailers sending bulk shipments were able to save at least 18% per parcel compared to smaller e-retailers who paid the 'single piece' price. Low volumes and a lack of interoperability (which reduces competition) were two of the main reasons for higher cross border prices, as well as higher costs (arising from transport) and weaker competition. Solutions suggested included volume consolidation; greater interoperability (especially for tracking and labeling); and strengthening monitoring and regulation of the market .

http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/post/doc/studies/20130715_ce_e-commerce-and-delivery-final-report_en.pdf

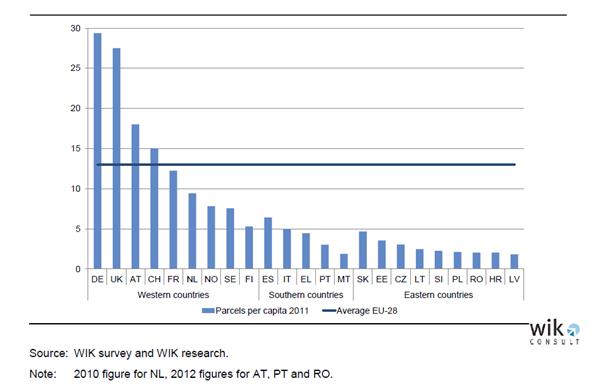

Main developments in the postal sector (2010–2013) – WIK Consult/Jim Campbell (August 2013)

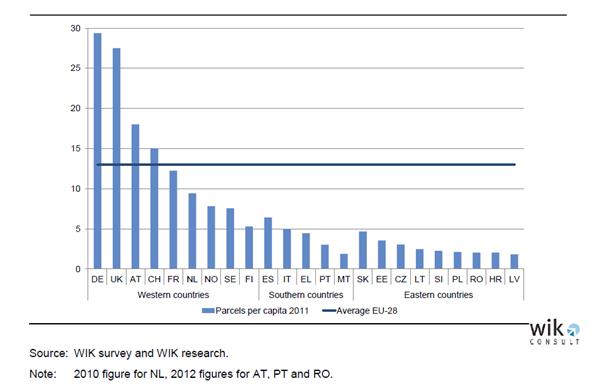

This study examined regulatory and market developments in both the letter and parcel markets across the EU and the EEA between 2010 and 2013 and their impact for future postal policy. Research was based on a survey of NRAs and competition authorities, and USPs; interviews with government officials, NRAs, USPs and other postal operators, and other associations with an interest in the postal sectors; a review of legislation, literature and market statistics; and economic modelling. The study noted that the role of postal services is changing as letters decline as a result of e-substitution yet at the same time e-commerce is driving growth in parcel delivery.

In terms of cross-border services, the study noted the distortions arising from the Universal Postal Union (UPU) system of terminal dues, in particular due to the lack of non-discriminatory access for designated operators, and the REIMS agreements. Most Member States, in response to a WIK survey, did not state that the tariff principles in Article 13 were respected for cross border items.

The 2013 WIK study also noted that there is "no consensus about the size of the European parcel and express market due to different market definitions" and that many regulatory authorities "do not systematically collect data on domestic and cross border parcel and express services". A "consistent methodology and … clear responsibilities for data collection" were recommended. The lack of data on employment in operators other than universal service providers was also noted, especially given the reductions in letter mail operations and growth in parcel volumes.

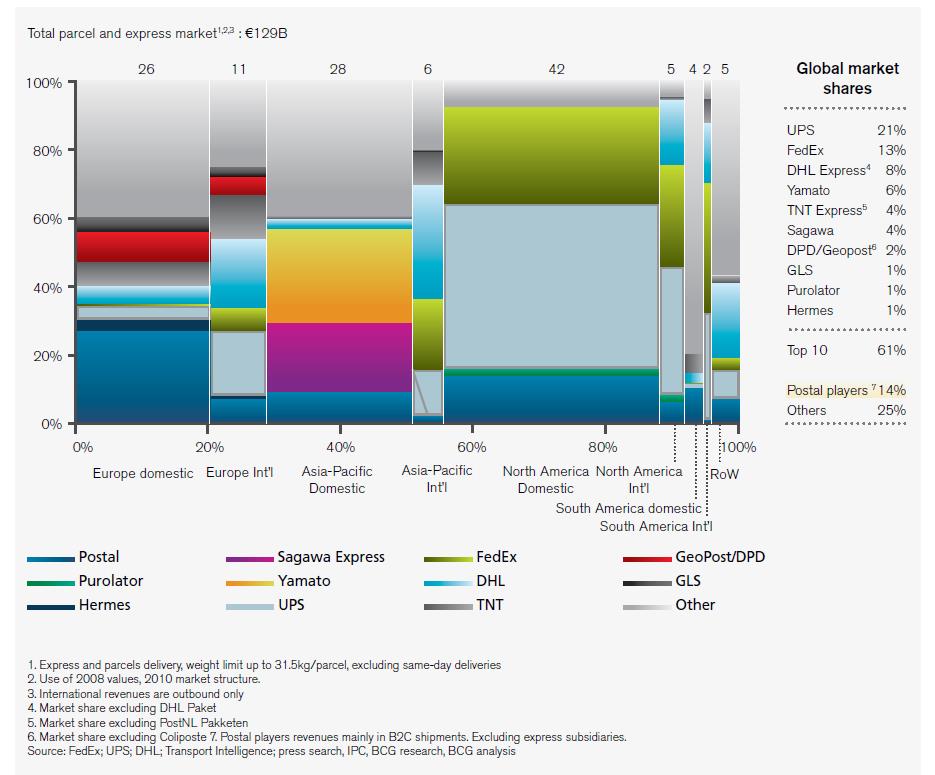

Differences between Member States' parcel and express markets were noted, in particular the difference in market size: the UK, France and Germany accounted for 70% of the EU market in 2012. Growth in the B2C market due to online shopping was also highlighted, as was some convergence between the two markets with operators traditionally focused on the B2B markets taking advantage of e-shoppers' desire for faster and more reliable parcel delivery services, and businesses switching to cheaper services to cut costs. National postal operators were estimated to have a wide range of domestic market shares.

The study recommended that NRAs and Governments should regularly compile market studies and introduce a more systematic observation of the parcel and express markets to ensure that the market can continue to operate without regulatory intervention. In terms of the cross-border market, they should become fully open and competitive, both within the EU and more widely, for example through a new notice on the application of competition rules to the postal sector; strengthening Article 13; a (new) process for reviewing multilateral terminal dues arrangements; and improved, standardised data collection, particularly covering employment in the sector.

http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/post/doc/studies/20130821_wik_md2013-final-report_en.pdf

European Regulators Group for Postal Services Opinion on Cross Border Parcel Delivery 2013

The European Regulators Group for Postal Services (ERGP) was established on 10 August 2010 and brings together the NRAs for the postal sector from the 28 Member States. The Commission, the EFTA Surveillance Authority, EEA countries and EU candidate countries participate as permanent observers. The group serves as a body for reflection, discussion and the provision of advice to the European Commission on postal services. It also aims to facilitate consultation, coordination and cooperation between EU countries and the Commission.

The 2013 ERGP Opinion on cross-border parcel delivery (requested by the European Commission) noted that " cross-border prices for European parcels delivery may be higher than what would be justified by cost differences related to domestic prices "and "collecting information on the market to better understand its functioning and any possible competition problems could be useful." The ERGP did however conclude that there was no indication of a competition problem that could be best dealt with by ex-ante regulation and they believed there was no need for a full formal market analysis.

All ERGP reports can be found here:

http://ec.europa.eu/growth/sectors/postal-services/ergp/index_en.htm

Special Eurobarometer 398 Internal Market Report

Fieldwork for this survey was conducted in April and May 2013 and covered the then 27 Member States plus Croatia. 27, 563 respondents were interviewed in their mother tongue for the survey.

The survey found that although almost half of those surveyed had shopped online in the last 12 months, just 11% had bought form another EU country and (6% ) from outside the EU, compared to 40% within their own country. Cheaper delivery prices were found to be the main improvement that would encourage more online shopping from other Member States. 41% always check for accreditation with a trustmark label or logo.

The proportion of online shoppers was highest in Sweden (79%), Denmark (76%) and the Netherlands (75%). Frequent online shopping was most common in the UK (31% several times a month). The proportion shopping online was lowest in Portugal (18%), Bulgaria (21%) and Croatia (21%). Online shopping was found to be less common in rural areas than towns (40% compared to 48% for small or mid-size towns and 49% for large towns), though the reason was not given.

The most common problems that shoppers experienced were found to be with delivery, whether for domestic or online purchases. For cross-border purchases 12% had experiences a delay in the delivery; 10% had had problems with the product arriving when the recipient was not at home; 8% mentioned delivery costs that were too high and 5% the lack of tracked services. 16% had tried to purchase from a website that did not deliver to the country of residence and 4% had to buy an additional guarantee or pay additional fees. Problems with payment methods 99%) and being redirected to other websites (6%) were also reported.

The main reasons for buying online were a preference to buy in shops and not needing to buy online. Delivery costs being too high was cited by 3% of respondents who had not bought online in their own country and 7% who had not bought form another Member State. Returns and reimbursement were mentioned by 5% domestic non-shoppers compared to 7% who did not shop from other Member States.

The most popular improvements which would encourage shoppers to buy abroad were cheaper delivery prices (19%), track and trace (11%) an easier returns process (11%); knowing the time and date of delivery (10%) and more convenient delivery options (5%). Nevertheless, 42% respondents said they would never purchase online from abroad. Lack of information about delivery and returns were found to contribute to a lack of trust in online retailers (each mentioned by 14% respondents who had changes their mind about a purchase because they did not trust the e-retailer).

http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_398_en.pdf

Committee on the Internal Market and Consumer Protection, Report on an integrated parcel delivery market for the growth of E-commerce in the EU, 14 January 2014 (2013/2043 INI)

This Report by the European Parliament's Committee on the Internal Market and Consumer Protection noted that cross-border delivery was considered to be an obstacle by 57% of retailers and that one in two consumers worried about cross-border transactions. It stressed that any action should take into consideration the sustainability of the delivery process and seek to minimise its environmental footprint. It also "deplored" the lack of transparent on pricing conditions and performance of services , called for the information on offer to be improved and noted a need to increase consumer confidence in and choice of cross-border services.

The report pointed out that delivery to remote areas or outermost reasons was one of the main reasons for consumer dissatisfaction and called for the geographic coverage and accessibility to the universal service to be improved in rural and remote areas. It stressed the importance of a stable and coherent social dimension with the high quality employment with ongoing training contributing to the quality of service. The importance of SMEs being able to grow and expand, but the fact that they often pay higher prices for delivery due to lower volumes was also highlighted.

The commission were asked to draw up guidelines on price comparison websites; delivery service indicators (jointly with industry; measures to improve interoperability and the creation [by the Commission] of platforms for co-operation and information sharing between delivery operators; and the creation of a pan European trustmark for e-commerce.

The report also states that any legislative measures should be carefully assessed and should seek to avoid hindering the dynamic aspect of the market, but that close market monitoring of all ty pes of delivery service provider is needed to identify where action may be needed. In addition it was recommended that Member States and the Commission should ensure that the existing regulatory framework was properly implemented and enforced.

Opinions provided by other European Parliament Committees highlighted the use of outsourcing in the delivery sector and that this should not be used as a way of evading remuneration requirements or employment legislation; the fragmentation between delivery providers; the positive impacts of labels and certificates for delivery services that could be used at a European level.

Flash Eurobarometer 396: Retailers' Attitudes Towards Cross Border Trade and Consumer Protection

Fieldwork for this study was carried out in March and April 2014 in the EU28 plus Norway and Iceland. The study was requested by the European Commission. It found that more than a quarter (28%) of retailers sell cross border to consumers. The main obstacles for retailers who sell online were a higher risk of fraud and non-payments in cross border sales (43%) and differences in national tax regulations (42%), whereas those who do not sell online mentioned as main obstacles the nature of business (50%) and a potentially higher risk of fraud and non-payment (45%).

Just above half of European retailers (54 %) were aware of any Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) entities, be it in their own sector or in any other sector. This comprises slightly less than a third (30 %) who are willing or mandated by law to use ADR in connection with consumer complaints, 16 % who are aware of such procedures but say that they do not exist in their sector and 8% who are aware but not willing to use them.

The survey showed that there were big variations in retailers’ preference of sales via e-commerce/mobile commerce between Member States. For example, retailers in Spain (57%) and France (54%) were the most likely to sell using e-commerce/mobile commerce whereas retailers in Romania (22%) and Slovenia (24%) were the least likely to use this channel. On average (for the EU28), 37% of retailers selling online found the higher costs of cross border delivery to be an important obstacle to the development of cross border sales, rising to over 50% in four Member States. The cost of resolving complaints and disputes cross border was considered to be a barrier by 38% of retailers selling online on average for the EU28, rising to over 50% for six Member States. Higher costs due to geographic distance were considered important by 40% of retailers on average, and by over 50% in seven Member States. By way of comparison, the costs arising from language differences were considered an obstacle by 27% of retailers on average (EU28) not reaching over 50% in any of the Member States.

http://ec.europa.eu/COMMFrontOffice/PublicOpinion/index.cfm/Survey/getSurveyDetail/instruments/FLASH/surveyKy/2032

European Regulators Group for Postal Services ERGP Report 2014 on the Quality of Services and End-User Satisfaction

This ERGP report uses data collected from 32 ERGP Members. The Quality of Service and End User satisfaction were measures with respect to transit time; collection and delivery; access points; consumer satisfaction and surveys measuring consumers' needs. Both letter and parcel services were covered by the study, though the summary here focusses on the result for parcels where available. The differences between the two also shows the different ways in which the two product groups are regulated.

13 Member states measured transit time for (domestic) parcels, whereas all measures the transit time of priority mail. Six Member States set a D+1 quality of service target for parcels, compared to almost every Member State for D+1 letter post, though a further 11 countries have a slower regulatory target for (parcel) transit time.

Difference methodologies are used to calculate the transit time for parcels. A previous ERGP report found that national regulatory authorities are more likely to be able to take action if letter targets rather than parcel ones are missed.

The study found that most national regulatory authorities are responsible for complaints relating to all postal service issues and not only universal service issues. It is however less common for other postal service providers to be required to publish information about procedures to complain, redress schemes, and means of dispute resolution than it is for NRAs to require that the universal service provider publishes such information. The data NRAs collect about complaints also tends to be about universal service products, rather than those falling outside the scope of the universal services, whether provided by other postal operators or the universal service provider.

Mandatory compensation schemes are more common for universal service providers than for other postal operators, as are existing compensation schemes, in particular for the arrival of an item late or damaged.

http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/ergp/docs/documentation/2014/ergp-14-24-report-on-qos-and-end-user-satisfaction-version-of-27-november-final_en.pdf

Design and development of initiatives to support the growth of e-commerce via better functioning parcel delivery systems in Europe (WIK Consult, August 2014)

This study was commissioned to assess the types of initiatives that could be used to support e-commerce through improved parcel delivery services. Given the diversity of e-commerce and delivery markets, four Member States (Germany, Greece, Ireland and Poland) were chosen as case studies. Desk research on the e-commerce delivery context was used to provide the foundations for interviews with stakeholders (including delivery operators, the e-commerce community and consumers) and workshops in the four case study countries to look at their particular requirements for e-commerce delivery and to gain feedback on the six possible initiatives that were tested.

The research concluded that an information platform on delivery services, with comprehensive and up to date information, would be welcomed by e-retailers as there was no such solution that covered the whole EU and all operators. A platform would support decision making by SME retailers by raising awareness of the different options available and the study suggested that the Commission should consider developing a common agreed terminology for all delivery services. Public authorities could also consider providing funding and/or promotional activities for such a platform.

An e-commerce scoreboard on price and delivery performance that could be compiled and published by the Commission and/or European e-commerce associations was also proposed, potentially combined with other data on the e-commerce market.

This study found that that many Member States had one or more trustmarks. While the inclusion of delivery elements would be welcomed, the report suggested that these could be combined with existing trustmarks or an umbrella certification process be introduced at EU level, instead of creating new, additional trustmarks. Where no trustmarks are present the reasons for this should also be examined.

Problems with the quality of service in rural areas were noted including fewer operators and slower delivery. It was suggested that these could be helped by sharing best practice about rural transport economics and effectiveness and studying the sharing of infrastructure for parcel delivery in low demand areas.

To improve interoperability, the report recommended monitoring the progress made by the postal industry and if improvements did not meet expectations, alternative policies could be considered. Non-discriminatory access to national postal operators' networks should also be enforced. Developments in measuring cross-border transit time for parcels should be monitored, given the need for reliability, yet balanced against the potential costs of investment.

http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/post/doc/studies/20140828-wik-markt-support-e-commerce_final-report_en.pdf

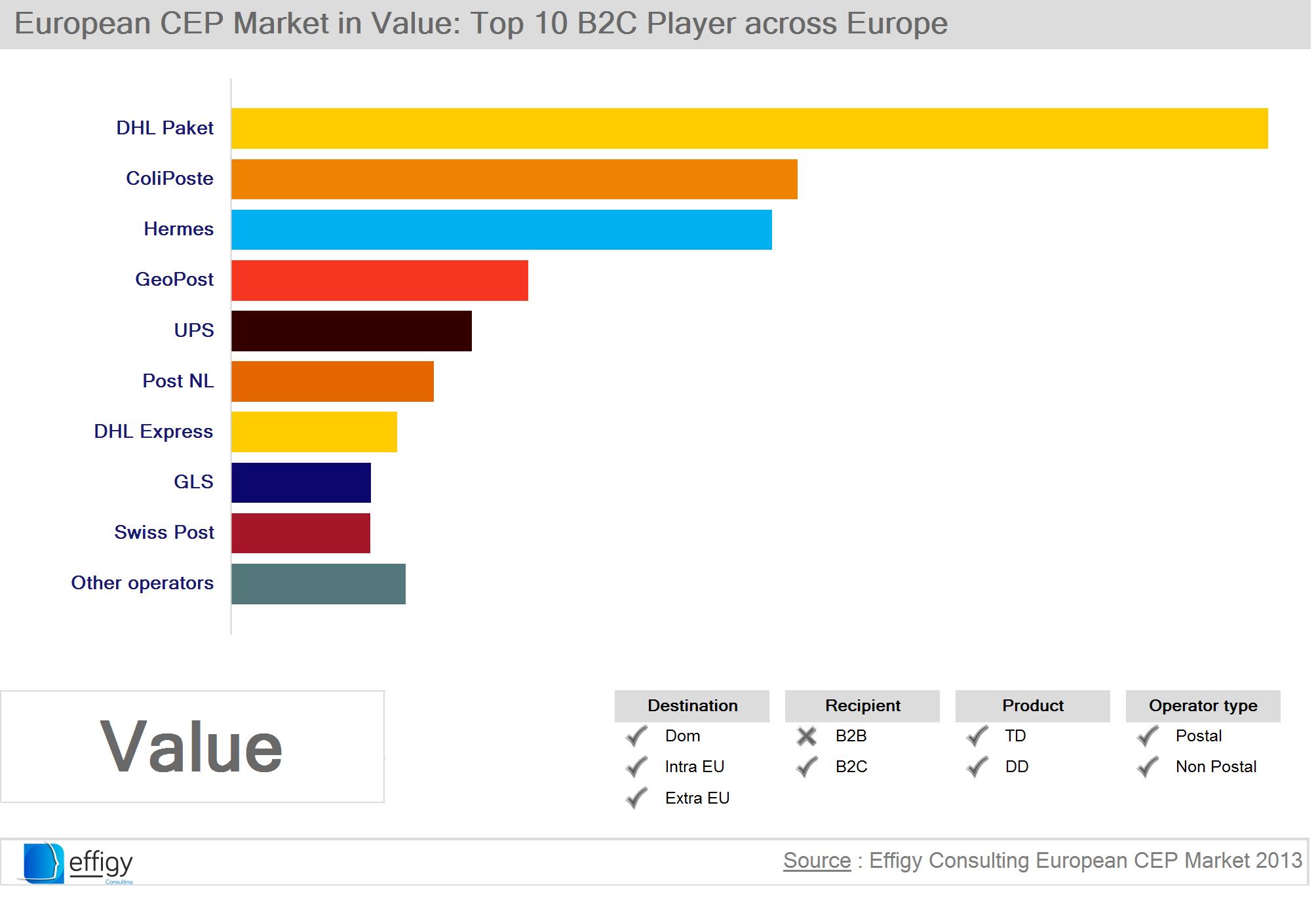

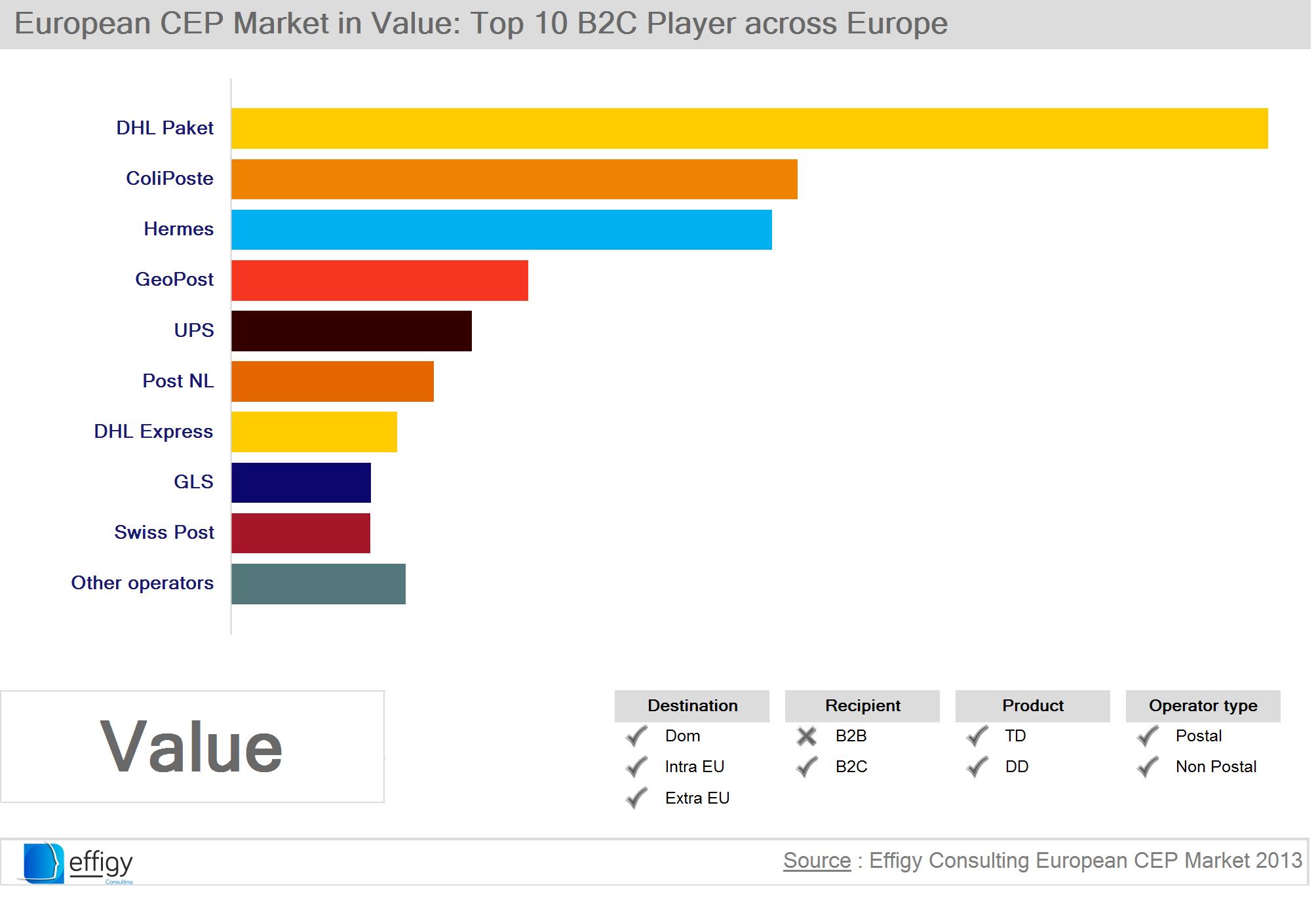

Effigy Consulting European Courier Express and Parcel 2013 Market Overview Summary¸(November 2014)

This study drew on primary and secondary research in 28 European Countries / EU28 (except Greece), Norway, Switzerland, Russia and Ukraine. The study defined parcels as "individual boxes or packages that can be carried by one man (up to 30kg) , and as well as only covering parcels, for the purposes of the study the CEP market was defined as having tracking throughout the delivery chain; using a regular transport network and the same corporate group of carriers for the brand.

The study found that volumes in the European CEP market were growing faster than revenues The three largest markets in terms of both value and volume were Germany, France and the UK.

http://www.effigy-consulting.com/

European Regulators Group for Postal Services Opinion on a better understanding of European e-commerce parcel delivery 2014

The 2014 ERGP Opinion on a better understanding of European cross-border e-commerce parcel delivery raised issues relating to quality; the difference between offers for bulk and individual customers; differences in monitoring and data collection regarding parcels; different national legal provisions; and issues affecting e-commerce more widely (e.g payments and transparency of information). The lack of evidence for introducing new ex-ante regulation in the cross-border parcel sector was restated.

http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/ergp/docs/documentation/2014/ergp-14-26-opinion-parcels-delivery-fin_en.pdf

Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on the Application of the Postal Services Directive, 2015

The Report on the Application of the Postal Services Directive is a requirement of the Postal Services Directive. As well as explaining how the Postal Services Directive has been implemented in Member States, the Report also set out data on the evolution of the European letter and parcel market, drawing on the Commission's statistics. Other sources of information used for the Report include reports but the European Regulators Group for Postal Services and the studies listed in this section, in particular WIK-Consult's Main Developments in the Postal Sector 2010-2013.

The Report concluded that the role of postal services was changing in many Member States, but the ability to send letters and parcels to arrive at a specified time at a definite price to all parts of the European Union remained a fundamental contributor to social, economic and territorial cohesion and the development of the single market. While e-substitution caused letter volumes to decline, on average falling by 4.85% between 2012 and 2013 (though by much more in some Member States such as Denmark and the Netherlands), e-commerce also offered new parcel delivery opportunities. Affordable and reliable parcel delivery services were therefore more important than ever to help realise the potential of the Digital Single Market - yet there were concerns about the price and quality of cross-border delivery services.

Furthermore, assessments of the size, value and employment impact of the parcel market are less comprehensive than for letters, making changes in the market harder to monitor and instances of market failure harder to ascertain. Despite the growth in e-commerce, NRAs for postal services still focus primarily on the letter market. The staff working document also noted that concerns had been raised about the working conditions in the parcel delivery sector.

http://ec.europa.eu/growth/sectors/postal-services/legislation/index_en.htm

European Regulators Group for Postal services 2015 Report to the European Commission on Legal Regimes Applicable to European domestic or cross-border parcel delivery

In 2015 the ERGP cross border sub group examined the legal regimes applicable to European domestic or cross-border parcel delivery and any specific provisions that may be in conflict with each other. The Report concluded that the boundaries of the market were not clear and included a wide variety of services. Different countries and NRAs do not always have definitions of the different products/services or sections of the market, where there are definitions these may differ between countries. This has an impact on data collection as the statistics on the CEP market might not always be comparable, and compounded by different approaches by NRAs to the collection and publication of data. Furthermore the boundaries of where different legislation applies (for example postal services and transport services) are also not always clear.

http://ec.europa.eu/DocsRoom/documents/14689/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native

UPS: Pulse of the Online Shopper

UPS research into online shopping, conducted by Comscore, compares the online shopping habits in Europe, North America, Asia and Australia. The surveys were 'blind', i.e. respondents were not aware that the research was being conducted on behalf of UPS. In addition to delivery features, the use of smartphones, the impact of social media and other consumer preferences (for example loyalty programmes) were assessed.

The 2013 Europe study noted that online shoppers were becoming increasingly demanding and retailers were "raising the bar" on customer service. Fieldwork was conducted in the first half of 2013 in Belgian, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and the UK, among individuals who regularly shopped online (at least twice in a typical three month period). Those shopping online more frequently made up a higher percentage of respondents. Delivery features were found to have a strong influence the choice of e-retailer. Free shipping was the main reason for recommending an e-retailer, followed by timely arrival and easy returns: more than half of online shippers had returned an online purchase. On the other hand, the key reasons for abandoning a shopping cart were shipping costs making the product more than expected, wanting to gain an idea of shipping costs and long delivery times. Over half through tracking was an essential service.

For the 2015 Europe study fieldwork was conducted in 2014 with participants from France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain and the UK using the same frequency requirements as the 2013 study. The study found that online shoppers and increasingly switching between devices and channels, with choices driven by convenience, and that information and control are crucial.

The survey found that in terms of delivery options, two in three shoppers prefer to have packages delivered home, fewer than in the previous year's study. 43% said that having a product delivered late decreases their likelihood of shopping with that retailer again. In terms of delivery features, consumers were least satisfied with the possibility of choosing a delivery date or rerouting packages while in transit.

Regarding returns, around half of the shoppers (53%) were satisfied with clear and easy to understand returns polices, and the ease of making online returns. 34% want a returns label in the box when it arrives and 58% say free return shipping is key to a good experience.

Delivery prices are important. 33% of consumers choose a slower transit time to qualify for free shipping, 67% say they will wait another one to three days to qualify for free (domestic) shipping), 47% will wait four days or more for free shipping within Europe, and 46% of loyalty programme participants value free shipping most as a benefit of membership.

Delivery times are also important. 60% of online shoppers choose delivery in two days or less and 58% of shoppers have abandoned a shopping cart due to slow delivery times or no delivery date being given.

The main items purchases were clothing (by 54%); books, music and movies (52%) and shoes (37%).

2013 Study:

https://www.ups.com/media/en/gb/UPS_Pulse_of_the_Online_Shopper.pdf

2015 Study:

https://www.ups.com/media/en/gb/OnlineComScoreWhitepaper.pdf

E-commerce Europe Studies

e-logistics: A need for integrated European solutions (2015) noted that although the work national postal operators were doing to improve the quality of services was welcome, ideally they would be consulting e-retailers and providing clearer communication on timings, and also addressing prices as both consumers and retailers find delivery prices an obstacle to buying and selling online. Other barriers for e-retailers that were noted included lack of transparency and competition in pricing; lack of information on differences in services and standards; slow delivery times; lack of track and trace services; customs and VAT rules; reverse logistics and lack of standardised labelling.

E-commerce Europe is therefore developing an e-logistics platform to improve transparency and help e-retailers by providing them with an independent source of "delivery intelligence", including listing the different delivery suppliers available for cross-border shipments. The intention is that the platform will also include data on quality of service to help overcome perceptions and problems of poor reliability of cross-border services and provide a service what will enable merchants to combine volumes and thereby hopefully obtain higher discounts. The report also encouraged the use of open standards, particularly in labelling to allow merchants to move between different delivery operators more easily; a better marketing dialogue between e-retailers and delivery operators to help the latter to understand the needs of the former and to develop new services to meet those needs; improved customer services (for the delivery element) and trustmarks indicating this; and free access to address databases.

http://www.ecommerce-europe.eu/stream/ecommerce-europe-position-paper-e-logistics-final-150507.pdf

Policy and market solutions to stimulate cross-border e-commerce in Europe set out barriers and possible solutions to cross-border e-commerce. Delivery/logistics issues were one of the main barriers mentioned, alongside legal frameworks and different tax regimes, including VAT. 44% of companies selling abroad that were surveyed said they found logistics and distribution a difficult barrier to tackle and 15% not selling abroad said excessive transport costs were preventing them from doing so. Specific barriers noted were the same as those included in the logistics paper (see above: transparency and competition in pricing; lack of information on differences In services and standards; slow delivery times; lack of track and trace services; customs and VAT riles; reverse logistics and lack of standardised labelling).

http://www.ecommerce-europe.eu/stream/ecommerce-europe-priority-paper-07052015-may-2015-final.pdf

The E-commerce Europe survey "Barriers to Growth" received answers from 352 companies in various member states and selling predominantly online and both online and offline, including to other businesses. Some were very small/ micro businesses (less than 10 employees) and over half of the companies surveyed already sold abroad, especially those with larger numbers of employees (77% with 20 or more FTE, 69% between 10 and 20, 53% between 0 and 1 FTE, 63% between 1 and 5%).

The main reason given for not selling cross border was that it was not a strategic priority for the company, followed by a lack of resources. Transport costs were the third most popular reason given. Companies with more that 50% of their activity linked to e-commerce reported transport costs as being particularly problematic. Logistics and distribution were seen as a difficult barrier by 44% respondents, with only 35% not finding them difficult. Examples of barriers included limited information and lack of choice about delivery services; slow delivery times; lack of track and trace; lack of competition and transparency in pricing; difficulties with returns, especially for smaller companies; and lack of standardised labelling. Different regulations and tax rates, especially concerning VAT and customs and online payments were among the non-delivery related barriers that were also highlighted.

As well as the creation of an online e-logistics web platform, the report also advocated a more connected and integrated delivery system; distance based invoicing; open standards, particularly for labelling and Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) files; and a common dialogue to help solve the gap between the supply of and demand for delivery products.

http://www.ecommerce-europe.eu/stream/survey-barriers-to-growth-ecommerce-europe-2015.pdf

Flash Eurobarometer 413: Companies Engaged in Online Activities (2015)

Fieldwork was conducted in January and February 2015. The survey covered 26 Member States and around 8,700 respondents were interviewed. Companies were selected who already sold online to other EU countries; who sold online domestically but has sold to other EU countries in the past; who were trying to sell to other EU countries; and companies that did not sell online. The responding companies were drawn from a range of sectors including accommodation, information and communication and manufacturing as well as retail. Amongst the companies that did not sell online to other EU countries, 21% are considering selling abroad at the moment. On average 85.4% of a company's online sales come from their domestic market.

The survey found that the cost of delivery and returns are two of the top three problems businesses face when selling cross-border. High delivery prices were the main problem for businesses selling online in another EU country (or have tried to) and those considering selling online. High delivery costs are a problem for 51% of businesses already selling online in another EU country, 62% of businesses trying to or considering selling abroad and 57% of companies who do not sell online.

The expense of resolving complaints and disputes cross-border is a problem for 41% businesses already selling cross-border and, 58% of businesses considering it. The cost of guarantees and returns is a problem for 42% of business already selling cross-border and 58% of businesses considering it.

Other problems included uncertainty about the rules that need to be followed (37% already selling/63% trying or considering selling), the cost or complexity of foreign taxation (38%/54%), and a lack of language skills (39%/ 48%).

Apex-Insight, European Parcels Market Insight Report, 2015

This report drew on desk research, published information and interviews with senior contacts in the market. It is focussed on Germany, the UK, France, Spain, Italy, the Netherlands a, Belgium and Poland, representing 79% of total parcels revenues (according to the Apex model). Other European countries (but not Russia or Turkey) were also included within the scope of the study, which defined the parcel market as comprising domestic; intra- European and international parcels; all service levels; and a weight of usually up to 31.5kg (depending on the definitions used by individual operators).

The study estimated the size of the European parcel market to be over 50 billion EUR in 2014, with growth in recent years being driven by home shopping. Growth was fastest in Poland and the UK. Trends in delivery features were also highlighted, such as the growth in collection points and parcel lockers. A gradual trend toward consolidation as independent companies are bought out by larger ones was noted, as was acquisition as a way of enhancing the consumer offering.

http://www.apex-insight.com/product/european-parcels-market-insight-report-2015-2/

European Commission, Identifying the main cross-border obstacles to the Digital Single Market and where they matter most, September 2015

This study was commissioned by the European Commission and included fieldwork carried out in February and March 2015. 23,599 respondents in the EU28 plus Norway and Iceland were surveyed.

The survey found that, on average and across all 12 markets surveyed, approximately just 19% of online respondents report having bought tangible goods or offline services from other EU countries compared to 68% of respondents who report having bought such products online from domestic sellers. For consumers, the three main concerns about purchasing products online cross-border inside the EU are related to delivery and returns: high delivery costs (27%), high return shipping costs (24%), and long delivery times (23%). For domestic purchases consumers are more concerned about personal and payment data and receiving the wrong or a damaged product. In addition, the survey showed that amongst those who experienced problems, the most common problem with tangible goods and offline services purchased online outside one's own country was long delivery time (14% inside the EU and 24% outside the EU).

Reasons that were repeatedly noted for not completing online purchases included high delivery costs (22% of surveyed consumers who could not complete online purchases -in BE and PL only, during a 2-3 week period in which respondents engaged in online purchasing), long proposed delivery times (17%), inconvenient delivery arrangements (16%), return shipping costs and concerns about fair treatment (10%), as well as other problems.

Clothes, shoes and accessories (21% of online buyers) were found to be the most commonly purchased products(latest online purchase), followed by electronics and computer hardware (13%), books (11%), cosmetics and healthcare products (8%), electrical household appliances (7%) and music and films (tangible media) (5%).

http://ec.europa.eu/consumers/consumer_evidence/market_studies/obstacles_dsm/index_en.htm

Annual Reports of Postal Operators

The Annual Reports of Delivery operators have been used, primarily to inform the Annex providing an overview of the parcel market, and are referenced where used. In addition to providing information about the individual operators, Annual Reports may also include information about the wider market in which companies operate, for example estimates of overall market share, size, growth projections and competition. They will in general also include information about the number of employees a company has – though this is not always stated on a comparable basis.

Postal Statistics Database

Postal Statistics for the European Union are now collected by the Directorate General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs, following the decision by Eurostat to stop the dedicated collection of statistics for the postal sector.

The statistics for 2014 show a wide variation in the number of standard parcels per capita across the EU. The statistics do however only cover standard parcels sent using universal service providers as many NRAs do not collect statistics on the wider parcel sector.

Prices obtained did however indicate that the prices charged by universal service providers for cross border deliveries are often three to five times the domestic price.

The statistics showed that in 2013 around 1.2 million people were employed by universal service providers, and the number of employees is falling, on average at a rate of 4.2% across the EU28 between 2012 and 2013. NRAs do not collect data on employment by other providers of postal services so we cannot quantify with certainty the impact that the growth in e-commerce is having on employment in the wider parcel delivery sector. Earlier estimates have however indicated that around 272,000 people were directly employed by the European express industry in 2010 and this number was projected to grow to 300,000 by 2020.

http://ec.europa.eu/growth/sectors/postal-services/statistics/index_en.htm

Econometric Study on Parcel Prices 2015

This study was commissioned by the European Commission in summer 2015 from the University of Saint-Louis, Brussels. It covered a number of research questions including the zoning strategies that are applied, the differences between operators for comparable products/services, a comparison of domestic and cross-border prices and an analysis of the prices differences between products and the discounts offered.

The study concluded that:

Cross border letter prices are on average about 3.5 times higher that their domestic equivalent and cross border parcel prices are on average about 5 times higher that their domestic equivalent

Zoning strategies do not affect cross-border price differentials

Parcels lead to higher cross-border price differentials than letters

Premium products to lower differentials than standard products

Weight increases the price differentials

Cross-border price differentials increase in flows between periphery countries and decrease in flows between the six largest Western European countries, as far as parcels are concerned.

There is indirect evidence suggesting that vertical integration seems to decrease price differentials.

Letter differentials and parcel differentials are explained by different factors, highlighting the differences in the market structure and maturity of competition between the two distinct product segments (scale, density of population, liberalization etc.).

Labor costs in the destination country, although being a large component of the cost structure of the cross border parcel delivery service does not seem to statistically influence cross border differentials, contrary to the domestic leg of the cost structure.

For further details see Annex 5, Market Overview.

http://ec.europa.eu/DocsRoom/documents/14647

Cross Border Parcel Logistics (2015)

This study was commissioned by the European Commission in summer 2015 from the University of Antwerp. It covered a number of research questions including elaborating on the cost drivers that influence the cross border delivery. The study simulated costs in given delivery scenarios and highlighted the importance of trade imbalances in cross border parcel delivery.

For further details see Annex 5, Market Overview.

http://ec.europa.eu/DocsRoom/documents/14647]

BEREC/ERGP, Price transparency and regulatory oversight of cross-border parcels delivery, taking into account possible regulatory insights from the electronic communications sector, Joint BEREC-ERGP opinion 2015

Following a meeting with Vice-President Andrus Ansip on 15 June 2015, the Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications (BEREC) and the European Regulators Group for Postal Services (ERGP) agreed to examine whether there were regulatory insights in the electronic communications sector that could be transferred to the postal sector. The report noted differences between the postal and electronic communications sectors, for example their different cost structures. It also found that the remit of many (postal) NRAs does not extend to all substitutable products and services in the postal sector and examined measures that could improve the transparency of retail prices.

http://ec.europa.eu/growth/sectors/postal-services/ergp/index_en.htm

Duch-Brown, N. and Cardona, M. (2016), Delivery costs and cross-border e-commerce in the EU Digital Single Market, JRC/IPTS Digital Economy Working Paper.

This study examined the potential benefits of reducing concerns related to delivery prices. It found that removing delivery concerns relating to price is highly likely to increase cross border e-commerce by 4.3 percentage points. This alone should impact positively increase household consumption by 2 307 million Euros (0.03%) and the Real National Income by 2 372 million Euros (0.02%). Those effects are mainly driven by the estimated decline in the overall consumer prices by a factor of 0.03% and from the subsequent increase in the overall exports that is able to balance the negative effect in the output of the retail sector. For firms removing delivery cost concerns would increase the number of firms selling online across borders by 6.2 percentage points and the volume of online trade by 5 percentage points. Medium sized firms would be especially benefited by the removal of delivery cost concerns, as this would influence their decision to engage in selling cross border at a rate of 20pp.

https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/sites/default/files/JRC101030.pdf

Annex 2 - Stakeholder Consultation

Overview

This Annex sets out chronologically the ways in which stakeholders have been consulted during the development of the cross-border parcel delivery proposal. As well as an overview of the responses to the 2012 Green Paper and workshops that have been used to seek the views of stakeholders, it includes a summary of the 2015 open public consultation on parcel delivery.

2012 Green Paper: "An integrated parcel delivery market for the growth of e-commerce in the EU"

The 2012 Commission Communication on E-commerce

identified the delivery of goods purchased online as one of the top five priorities for boosting e-commerce by 2015. The 2012 Green Paper on Parcel Delivery therefore sought views on the information needs of consumers and e-retailers; the need for an improved quality of service and the way in which this could be obtained; means of reducing costs and increasing efficiency; delivery prices; competition; regulatory oversight; interoperability and governance.

The two main conclusions of the Green Paper were that e-commerce driven delivery was a key factor in the overall development of e-commerce and that the increasing expectations of consumers and e-retailers regarding parcel delivery services were not being met, especially for cross-border delivery.

89 contributions to the consultation were received, including from e-retailers, delivery operators, public authorities (including postal ministries and regulators), trade unions, consumer representatives and individuals. In their responses, most stakeholders and Member States' authorities expressed a preference for industry driven action and non-legislative measures, rather than new regulation. Most replies also characterised the existing regulatory framework as broadly sufficient and fit for purpose (including the Postal Services Directive, Consumer Rights Directive and Online and Alternative Dispute Resolution Procedures), although numerous replies highlighted challenges such as high prices, low quality of service and lack of information. When asked to identify regulatory gaps, responses included lack of information and traceability, high prices and consumer protection when delivery went wrong. Other issues raised included interoperability and lack of common standards, network access, geographic coverage and more generally the lack of easy cross border sales and returns. Information that respondents suggested could be provided often concerned delivery features (e.g. delivery times and tracking) and around half though trust labels could be useful. A new universal service obligation was not thought necessary by around two thirds of respondents and most responses suggested that a price cap would not be the appropriate tool to address the needs of e-retailers and consumers.

The Green Paper, contributions to the consultation and the summary of responses are available here:

http://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/newsroom/cf/itemdetail.cfm?item_id=6356

Online and Postal Services Workshops 2012/13

Three workshops were held during the course of 2012/13 to present the external studies that had been commissioned to inform postal services policy. On 17 September the studies "Main Developments in the Postal Sector (2010-2013) and EU Parcel Markets with a particular emphasis on e-commerce were discussed.

Postal User Form 2014

The Postal User Forum

held on 21 March 2014 focused exclusively on parcel delivery and discussed the actions set out in the 2013 Roadmap. The 75 attendees included MEPs, e-retailers, delivery operators, regulators, trade unions and third party service providers. Delivery operators highlighted the cost of investment to develop new services. Participants reported that consumer expectations of delivery services were increasing and consumer trust was built mainly on quality of service, fair pricing and clear liability. E-retailers reported that delivery services across the EU were fragmented and they experienced problems with liability and responsibility during delivery. The social dimension and differences in employment conditions between parcel operators were also noted.

Workshop with Regulators on Regulatory Oversight of Parcel Delivery

This workshop, held on 23 April 2015, brought together several regulators from several Member States. The differences in the regulatory oversight of the parcel markets was discussed, along with the need for additional oversight, what it could cover and the different regulatory tools that could be suitable.

Most NRAs had limited oversight of the parcel market outside the scope of the universal service, whether because of the legal mandate of the NRA or prioritisation of resources. Some regulators did however also note that work was underway to understand their parcel markets better, including other operators, though there was no consensus that such work needed to be formalised. Furthermore, the European Regulators' Group for Postal Service (ERGP) was doing further work on different regulatory regimes which would also need to be taken into consideration.

2015 Public Consultation on Cross-Border Parcel Delivery

About the Consultation

The open public consultation on cross-border parcel delivery ran from 6 May 2015 to 5 August 2015. 361 responses were received. Most responses were received through the online tool (including answers to the questionnaire and uploaded documents), although some responses were also received by email.

The consumer and e-retailer questionnaire was published in six languages (EN, DE, FR, IT, ES, and PL). The questionnaire for delivery operators was subdivided into versions for delivery intermediaries and other logistics providers; predominantly domestic carrier; operator with international coverage; international integrators; and national postal operators. Respondents were able to reply in any official language of the EU. The consultation was publicised on the European Commission's 'your voice in Europe' website, through the online Linked in Parcel Delivery Group and social media channels of DGs GROW, CNECT and JUST, the SME network and at stakeholder meetings.

Reponses where confidentiality was not requested (i.e. where respondents were happy for their response to be published, whether with their name or anonymously) have been published with the exception of delivery operators as most requested confidentiality.

The number of responses below reflects the Commission's classification of responses, not necessarily the consultation form that was used. Blank responses, or where no information beyond a name was provided, have not been included in the totals below.

|

Consumer

|

211

|

|

Retailer

|

64

|

|

Delivery Operator

|

35

|

|

Of which:

|

|

|

NPO

|

21

|

|

Other delivery operators

|

14

|

|

Representative bodies/organisations, Member States and Regulators

|

51

|

|

TOTAL

|

361

|

The consultation sought the views of interested parties; the responses are not statistically representative. Where fractions or percentages have been reported below, these are derived from the number of responses to a particular question, rather than to that section of the consultation or the consultation as a whole.

About the Respondents

Retailers

The location of the headquarters of retailers who responded were mainly in Germany, the UK and Spain, with over one fifth of the retailer responses from each of these locations. Most were SMEs (51 responses, of which 43 were micro businesses). Around half sold their goods online only and half sold both online and in a physical store. Micro businesses replying were more likely to sell online only. Aside from the 'other' category, the most common products sold were shoes and accessories followed by clothing. Most (45 responding retailers) sold to both domestic and international customers. Of those who did not sell online cross-border, delivery was more common than other reasons for not selling online to other countries.

Nearly half the retailers responding stated that the share of packets and parcels returned to them was less than 1%. Several retailers indicated that there was no significant difference between the rate of returns between domestic and international customers although others stated they received more returns from domestic sales than from international ones. There were few responses to the question about weight categories, and where answers were given they were affected by the type of product sold for example retailers selling electronics had heavier shipments on average than those selling cosmetics.

Consumers

211 responses from consumers in 18 EU and EEA/EFTA countries were received through the online tool. Most of the consumers' replies came from Spain, the United Kingdom, and Belgium. Seven consumer associations also responded. Over half of the consumers who replied were content to have their contributions published, albeit anonymously. Over three quarters of the responses came from consumers aged between 18 and 44, and around two thirds were male. Nearly half shopped online every month, and nearly one third shopped online once a week or more. Travel, accommodation and event tickets was the most common category of online purchase, followed by consumer electronics and clothing. Roughly equal numbers bought from the country in which they lived and from other EU/EEA/EFTA countries.

Delivery Operators

21 national postal operators (NPOs) replied to the consultation. Other operators who responded included express operators/integrators, and operators with predominantly domestic and international coverage. Representative bodies for delivery operators also replied. Most operators requested that their responses remained confidential or anonymous given the commercial nature of some of the questions.

The most common type of cross-border delivery service for national postal operators involved the networks of the national postal operators of the countries involved to arrange cross-border delivery operations and there was agreement with the description representing the "standard delivery model". Other operators stated they use a mix of their own networks (where applicable), other private (non NPO) delivery operators and NPOs.

For the NPOs and other operators the proportion of express parcels (in contrast to standard parcels) varied greatly. Standard parcels were more common than express for NPOs and deliveries handled by NPOs weighed less than those delivered by other operators, as a proportion of packet and parcel shipments. The domestic market was responsible for the majority of NPOs' volumes. NPOs and other operators used a mix of road and air transport.

For NPOs, remuneration costs/ termination rates were reported to be the main determinant of prices. For other operators, competition and transport costs were listed as most important factors when setting prices by larger companies.

Representative Organisations, Member States and Regulators

Representative bodies for consumers, businesses and retailers, delivery operators and trade unions replied to the consultation. In some cases these were domestic representative organisations, in others pan European. National Regulatory Authorities for postal services and government ministries also replied. Most agreed that their responses could be published. In this analysis the views of representative bodies are, where possible, are grouped with individual responses from those they represent, i.e. consumers, retailers and delivery operators.

About Delivery Services

Retailers' experiences

Retailers use a range of delivery services to ship cross-border. Over half always or often use the NPO, but express carriers and other private operators are also used. Track and trace capability and price appeared to be the most important considerations for e-retailers (and their customers): nearly one third always offer a track and trace services and one third often use the cheapest service.

Retailers were most satisfied with the information from delivery operators about delivery options and prices, speed of delivery and (low) number of items lost. These features all had over 40% responses satisfied or very satisfied. Retailers were least satisfied with the possibility of changing the delivery location after dispatch, delivery prices and complaints handling. These features all had over one third of responses very unsatisfied or not satisfied. Smaller companies were particularly likely to be unsatisfied with the price of delivery services.

Q13 (retailers) - How satisfied are you with the following delivery features when selling to other European countries? Please rank each answer that applies to you on a scale from 1 to 5.

When asked about the cost of delivery, over half the responses from e-retailers stated that for domestic online sales, the cost of delivery represented 15% or less of their e-commerce turnover. For cross-border sales, nearly half the responses stated that the cost was 6-25% of turnover, rising to over half for 6-25% or more. Micro-companies in particular estimated that cross-border sales represented a greater share of their e-commerce turnover than domestic sales did.

Responses about free delivery were mixed, with just over half the responding retailers offering some form of free delivery (whether for domestic and international or only domestic purchases) and just under half offering no free delivery option. For those offering free delivery, this was most common for purchases above a certain value or as a temporary promotion. Retailers noted that the cost of 'free delivery' was often passed onto consumers through higher product prices. About a third stated that they could not offer free delivery because of the high cost of cross-border delivery or the weight of the products they sold.

Excluding free delivery options, retailers were asked whether they charged their customers more, less, or the same as the price they paid delivery operators. Of those who responded to this question, nearly half stated that they charged consumers more than they pay delivery operators, with the remainder evenly split between charging the same amount as they pay and charging less.

More than half of those responding to the question stated that they did not receive any price discounts from delivery operators for the packets or parcels they sent to other European countries. Reponses differed according to company size with micro businesses less likely to receive discounts (over two thirds responding stated they did not receive discounts) whereas almost all larger companies did receive discounts (though the number of larger companies that replied to the consultation was small). Very few respondents provided information about the discounts they received from delivery operators. Where they did responses indicated the use of annual contracts with the national postal operator and that discounts depended on the weight and volume of shipments.

Consumers' Experiences

The two obstacles most commonly mentioned by the consumers who replied to the question as "always" being a delivery problem when buying online were "Unable to redirect a delivery which is in progress to another delivery location" (more than one third of respondents) and "No possibility of delivery at predefined date and time slot" (more than one quarter of respondents). Problems that were "often" encountered included "no free delivery option" (over half of respondents), 'high delivery prices' (just under half); cost of delivery (over one third); and "high costs of return" (just under one third'; as well as other delivery features such as lack of choice of date and time of delivery (over one third respondents) and no delivery location options (one third respondents). "Unable to track the location of a good…" and "unable to find clear information about delivery options and prices" were identified as sometimes being obstacles by around half of the respondents. "Items being lost in transit" was most commonly stated to "never" be a problem. Expensive customs declarations in the Canary Islands were also cited as a problem, as were geographic restrictions on sales and surcharges to remote and peripheral areas, amongst other features.

Q6 (consumers) – When buying online how often do you face the following delivery problems?

In terms of delivery locations, delivery to a home address (for over half of the consumer responses) and delivery to a work address (over one third of consumer responses) were deemed to be 'very important'. Delivery locations ranked as 'important' by over one quarter of respondents included relay points/shops with collection facilities, post offices and neighbours.

Over three quarters of consumers who responded stated they had in the last 12 months considered an online purchase, but then abandoned it only because of concerns about delivery. The most commonly highlighted reason, reported by over two thirds of consumers responding to this question was high delivery prices, followed by too slow delivery, reported by one third of responding consumers and no free return option, reported by nearly a quarter of responding consumers.

Delivery Operators' Experiences

The main obstacle faced when delivering abroad that NPOs and other operators reported was customs rules and procedures. Security procedures were also a significant problem for NPOs. Difficulties with finding an operator in the destination country, negotiating favourable conditions, interoperability of networks and transport requirements were also reported. Other operators also noted that obstacles differ between destination countries, as well as the effects of the VAT exemption for public postal services and inter-operator pricing arrangements can limit competition and create distortions.

Outside the EU, most answers from other operators about obstacles to delivery focussed on tax and duty/customs and security procedures. A lack of ability to clear and release goods for the entire EU in one specific country was also raised, and fragmentation of road transport policies across Europe were also noted. NPOs and other delivery operators also raised insufficient remuneration given delivery costs, transport options and costs and the lack of interoperability as problems. Several NPOs responses noted that the remuneration received from operators outside the EU/EEA did not cover costs, especially if additional services such as a registered service were used. E-commerce flows from Asia in particular posed a financial challenge for European operators, and e-retailers also noted the difficulty in competing with these cheaper delivery costs.

Representative Organisations, Member States and Regulators' Experiences

Several Member States stated that the cross-border parcel delivery market is not functioning properly and indicated a range of reasons (including disproportionate costs; taxation issues; discrimination; regulatory differences; lack of interoperability, transparency, consumer protection, quality measurement, confidentiality and security… ). Other Member States indicated there was no issue with affordability and regulatory oversight, because the market for (cross-border) parcel delivery is liberalized, competitive and dynamic.

Trade associations were divided about the need for additional measures to improve the cross-border parcel delivery market. Some agreed that price structures are not transparent, while others were concerned that regulation leads to (unnecessary) bureaucracy and can stifle innovation.

Trade unions unanimously signalled shortages in terms of social protection in the (labour-intensive) parcel delivery market and criticised sub-contracting and "false self-employment.

Areas for Improvement

For Retailers