EUR-Lex Access to European Union law

This document is an excerpt from the EUR-Lex website

Document 52016XC1104(04)

State Aid — Germany — State Aid SA.42393 (2016/C) (ex 2015/N) — Reform of support for cogeneration in Germany — Invitation to submit comments pursuant to Article 108(2) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European UnionText with EEA relevance

Staatliche Beihilfe — Deutschland — Staatliche Beihilfe SA.42393 (2016/C) (ex 2015/N) — Förderung der Kraft-Wärme-Kopplung in Deutschland — Aufforderung zur Stellungnahme nach Artikel 108 Absatz 2 des Vertrags über die Arbeitsweise der Europäischen UnionText von Bedeutung für den EWR

Staatliche Beihilfe — Deutschland — Staatliche Beihilfe SA.42393 (2016/C) (ex 2015/N) — Förderung der Kraft-Wärme-Kopplung in Deutschland — Aufforderung zur Stellungnahme nach Artikel 108 Absatz 2 des Vertrags über die Arbeitsweise der Europäischen UnionText von Bedeutung für den EWR

C/2016/6714

OJ C 406, 4.11.2016, p. 21–75

(BG, ES, CS, DA, DE, ET, EL, EN, FR, HR, IT, LV, LT, HU, MT, NL, PL, PT, RO, SK, SL, FI, SV)

|

4.11.2016 |

DE |

Amtsblatt der Europäischen Union |

C 406/21 |

STAATLICHE BEIHILFE — DEUTSCHLAND

Staatliche Beihilfe SA.42393 (2016/C) (ex 2015/N)

Förderung der Kraft-Wärme-Kopplung in Deutschland

Aufforderung zur Stellungnahme nach Artikel 108 Absatz 2 des Vertrags über die Arbeitsweise der Europäischen Union

(Text von Bedeutung für den EWR)

(2016/C 406/03)

Mit Schreiben vom 24. Oktober 2016, das nachstehend in der verbindlichen Sprachfassung abgedruckt ist, hat die Kommission Deutschland von ihrem Beschluss in Kenntnis gesetzt, in Bezug auf einen Teil der genannten Beihilferegelung das Verfahren nach Artikel 108 Absatz 2 des Vertrags über die Arbeitsweise der Europäischen Union einzuleiten.

Wie in dem auf die Zusammenfassung folgenden Schreiben dargelegt, hat die Kommission beschlossen, gegen bestimmte andere Beihilfemaßnahmen keine Einwände zu erheben.

Alle Beteiligten können innerhalb eines Monats nach Veröffentlichung dieser Zusammenfassung und des Schreibens zu der Beihilfemaßnahme, die Gegenstand des von der Kommission eingeleiteten Verfahrens ist, Stellung nehmen. Die Stellungnahmen sind an folgende Anschrift zu richten:

|

Europäische Kommission |

|

Generaldirektion Wettbewerb |

|

Registratur Staatliche Beihilfen |

|

B-1049 Bruxelles/Brussel |

|

Fax + 32 22961242 |

|

Stateaidgreffe@ec.europa.eu |

Alle Stellungnahmen werden Deutschland übermittelt. Beteiligte, die eine Stellungnahme abgeben, können unter Angabe von Gründen schriftlich beantragen, dass ihre Identität nicht bekannt gegeben wird.

VERFAHREN

Am 28. August 2015 meldete Deutschland die im Entwurf vorliegende Novelle des Kraft-Wärme-Kopplungsgesetzes (im Folgenden KWKG 2016) bei der Kommission zur Genehmigung an. Das Gesetz wurde am 21. Dezember 2015 verabschiedet und trat am 1. Januar 2016 in Kraft.

Deutschland meldete die Maßnahme aus Gründen der Rechtsicherheit an. Seiner Auffassung nach wird die Maßnahme nicht aus staatlichen Mitteln finanziert, weil sie nicht direkt aus dem Haushalt des Staates, sondern über eine durch die Netzbetreiber erhobene Umlage auf den Stromverbrauch finanziert wird.

BESCHREIBUNG DER MAßNAHME

Die angemeldete deutsche Förderregelung sieht vor, dass für den Betrieb von Kraft-Wärme-Kopplungsanlagen (im Folgenden „KWK-Anlagen“), für den Neu- und Ausbau von Fernwärme-/Fernkältenetzen sowie für den Bau und die Nachrüstung von Wärme- und Kälte-Speichern Förderungen gezahlt werden.

Die Maßnahme wird über eine Umlage auf den Stromverbrauch finanziert, die durch die Netzbetreiber als Aufschlag auf die Netzentgelte (im Folgenden „KWK-Umlage“) erhoben wird.

Die Höhe der KWK-Umlage wird jedes Jahr von den Übertragungsnetzbetreibern als einheitlicher Satz pro verbrauchter kWh berechnet (2016 betrug er 0,445 Cent/kWh). Gleichwohl sieht das KWKG vor, dass die KWK-Umlage bei Letztverbrauchern mit einem Jahresverbrauch von mehr als 1 GWh (im Folgenden „LV-Kategorie B“) höchstens 0,04 Cent/kWh und bei Letztverbrauchern aus dem produzierenden Gewerbe, deren Verbrauch mehr als 1 GWh betrug und deren Stromkosten 4 % des Umsatzes überstiegen (im Folgenden „LV-Kategorie C“), höchstens 0,03 Cent/kWh betragen darf.

WÜRDIGUNG

Durch die Deckelung der KWK-Umlage auf 0,04 Cent/kWh bzw. 0,03 Cent/kWh verringert das KWKG die Lasten, die unter die LV-Kategorie B oder C fallende Unternehmen normalerweise ohne die Ermäßigungen zahlen müssten. Dies stellt einen Vorteil dar, der zudem selektiv ist. Unter die LV-Kategorie C fallen nur Unternehmen des produzierenden Gewerbes. Die LV-Kategorie B kann theoretisch Unternehmen aus allen Wirtschaftszweigen umfassen, wird aber größere Unternehmen mit einem Jahresverbrauch von mehr als 1 GWh gegenüber kleineren Unternehmen und auf alle Fälle Unternehmen aus Wirtschaftszweigen mit traditionell hohem Stromverbrauch begünstigen.

Dieser Vorteil wird aus staatlichen Mitteln finanziert. Nach Auffassung der Kommission handelt es sich bei der KWK-Umlage um staatlich kontrollierte Mittel. Wie bei dem Sachverhalt, zu dem der Gerichtshof am 19. Dezember 2013 in der Rechtssache Association Vent de Colère (1)! ein Urteil fällte, hat der Staat im Rahmen des KWKG ein System geschaffen, durch das die Kosten der Netzbetreiber im Zusammenhang mit der Förderung der Erzeugung von KWK-Strom und des Baus von Speichern und Fernwärme- bzw. Fernkältenetzen vollständig über die den Stromverbrauchern auferlegte KWK-Umlage ausgeglichen werden. Die Ermäßigungen der KWK-Umlage werden ebenfalls aus staatlichen Mitteln finanziert, da sie eine zusätzliche Belastung des Staates darstellen. Jede Ermäßigung der KWK-Umlage führt zu einer Verringerung der von den betreffenden Verbrauchern (LV-Kategorien B und C) zu entrichtenden Beträge und somit zu Einnahmeverlusten, die dann über eine höhere KWK-Umlage der anderen Verbraucher (LV-Kategorie A) gedeckt werden müssen.

Ermäßigungen der KWK-Umlage können den Wettbewerb zwischen Unternehmen aus demselben Wirtschaftszweig verfälschen, da nicht alle Unternehmen förderfähig sind, und können sich auf den Handel zwischen Mitgliedstaaten und den Wettbewerb mit Unternehmen in anderen Mitgliedstaaten auswirken. Insbesondere Unternehmen aus den für die Umlagenermäßigung in Betracht kommenden Wirtschaftszweigen (z. B. Chemie- oder Papierindustrie, Automobilherstellung und deren Lieferkette) stehen mit den entsprechenden Unternehmen in anderen Mitgliedstaaten im Wettbewerb.

Ermäßigungen der KWK-Umlage fallen nicht unter die Leitlinien für staatliche Umweltschutz- und Energiebeihilfen 2014-2020 (2). Die Leitlinien enthalten Bestimmungen über Beihilfen in Form von Ermäßigungen des Beitrags zur Finanzierung erneuerbarer Energien, aber nicht über Beihilfen in Form von Ermäßigungen des Beitrags zur Finanzierung der Kraft-Wärme-Kopplung oder anderer Energieeffizienzmaßnahmen. Gleichwohl kann die Kommission eine Beihilfemaßnahme unmittelbar auf der Grundlage des Artikels 107 Absatz 3 Buchstabe c AEUV für mit dem Binnenmarkt vereinbar erklären, wenn sie erforderlich und angemessen ist und die positiven Auswirkungen der Maßnahme auf das Ziel von gemeinsamem Interesse die negativen Auswirkungen auf Wettbewerb und Handel überwiegen.

In diesem Fall könnte geltend gemacht werden, dass die verringerte KWK-Umlage zu einem Ziel von gemeinsamem Interesse beiträgt, wenn zum einen die Förderung selbst auf ein solches Ziel ausgerichtet ist und zum anderen die Ermäßigungen erforderlich sind, um die Finanzierung der auf das im gemeinsamen Interesse liegende Ziel ausgerichteten Förderung zu gewährleisten.

Die Kommission stellte fest, dass die über die KWK-Umlage finanzierten Fördermaßnahmen (d. h. die Förderung von KWK-Anlagen, Fernwärme- und Fernkältenetzen sowie Wärme- und Kältespeichern) mit dem Binnenmarkt vereinbar sind.

Ferner könnte das Argument angeführt werden, dass die Finanzierung dieser Fördermaßnahmen über eine Umlage auf den Verbrauch ein geeignetes Instrument ist, weil eine enge Verbindung zwischen den geförderten Maßnahmen und dem Energieverbrauch besteht, die Umlage einen relativ stabilen Finanzstrom gewährleistet und die Haushaltsdisziplin nicht beeinträchtigt wird. Letzteres ist angesichts der Energieeffizienzziele der Union von besonderer Bedeutung. Die Mitgliedstaaten sind verpflichtet, ihr Potenzial für die Durchführung von Energieeffizienzmaßnahmen (z. B. Einsatz von KWK-Anlagen und Fernwärme) zu bewerten und dem ermittelten Potenzial Rechnung zu tragen. Der Finanzierungsbedarf für die Berücksichtigung des ermittelten Potenzials kann hoch werden, sodass die Mitgliedstaaten möglicherweise zunehmend auf Umlagen auf den Verbrauch zurückgreifen müssen, um die Maßnahmen zu finanzieren.

Folglich könnten die Ermäßigungen als geeignetes Instrument zur angestrebten Förderung der Energieeffizienz erachtet werden, wenn ohne diese nachweislich das Risiko bestünde, dass keine solchen Umlagen erhoben werden, und somit die Finanzierung der Förderregelung und letztlich die Regelung an sich gefährdet wären. Dies wäre jedoch nur der Fall, wenn die umlagenfinanzierte Förderung ohne die Ermäßigungen nachweislich aus dem Grund gefährdet wäre, dass eine erhebliche Zahl von Unternehmen abwandern oder insolvent würden, wenn sie die volle Umlage zahlen müssten. Selbst wenn die Ermäßigungen nachweislich erforderlich wären, müssten sie auch dem Ziel angemessen und auf das für die Finanzierung der Beihilfe erforderliche Minimum beschränkt sein.

Zu diesem Aspekt hat Deutschland wenig Informationen übermittelt, was damit begründet wurde, dass keine konkreten Daten für die betroffenen Beihilfeempfänger und Wirtschaftszweige verfügbar seien. Deutschland nimmt jedoch an, dass die Empfänger in vielen Fällen Unternehmen sind, die auch für verringerte EEG-Umlagen in Betracht kommen, hat dies aber nicht belegt. In der Tat gehen die Förderkriterien für eine Ermäßigung der KWK-Umlage offenbar über die Kriterien des Erneuerbare-Energien-Gesetzes (EEG) hinaus.

Außerdem hat Deutschland keinen Nachweis dafür erbracht, dass die Ermäßigungen auf das erforderliche Minimum begrenzt sind. Anscheinend handelt es sich um stärkere Ermäßigungen als bei der EEG-Umlage.

Die Kommission hat deshalb Bedenken in Bezug auf den Anreizeffekt und die Angemessenheit der Beihilfe. Da beides noch nicht nachgewiesen wurde, zweifelt die Kommission beim derzeitigen Stand daran, dass die aus der Entlastung bestimmter Unternehmen von einem Teil ihrer normalen Betriebskosten resultierende Wettbewerbsverfälschung begrenzt ist und die Auswirkungen der Maßnahme insgesamt gesehen positiv sind.

Nach Artikel 16 der Verordnung (EU) 2015/1589 des Rates können alle rechtswidrigen Beihilfen vom Empfänger zurückgefordert werden.

SCHREIBEN

1. PROCEDURE: NOTIFICATION, CORRESPONDENCE, DEADLINE ETC.

|

(1) |

On 28 August 2015, further to pre-notification contacts, the German authorities notified to the Commission the draft bill on the Reform of the Combined Heat and Power Generation Act (Heat and Power Cogeneration Act, hereinafter: KWKG or KWKG 2016), which was then adopted into law on 21 December 2015. It replaces the Combined Heat and Power Generation Act enacted on 1 April 2002. |

|

(2) |

As at the time of the notification, the draft law was still under discussion in Germany; Germany submitted updated versions of the draft law and additional explanations to the notification on 31 August, 18 September, 21 September and 28 September 2015. On 29 September 2015 it also submitted a draft evaluation plan that was updated on 14 June 2016. |

|

(3) |

The Commission sent requests for information on 9 and 28 October, 13 November, 10 December 2015, 4 February, 19 May, 20 July, 30 August and 21 September 2016. |

|

(4) |

Replies were submitted on 12 November, 24 November and 17 December 2015, on 3 March and 30 May, in August and September 2016. The latest information was submitted on 28 September 2016. |

|

(5) |

On 4 August 2016, Germany waived its right under Article 342 TFEU in conjunction with Article 3 of Council Regulation (EEC) No 1/1958 (3) to have the decision adopted in German and agreed that the decision be adopted and notified in English. |

|

(6) |

Germany has notified the measure for legal certainty. It considers that the measure is not financed from State resources. It has indicated that the arguments put forward in the EEG 2012 (4) and EEG 2014 (5) State aid cases as well as in the EEG 2012 Court case (6) are valid for the CHP file as well, without however enumerating them. It has briefly pointed to the similarities with the EEG support: support based on a guaranteed feed-in tariff that is covered by a levy on electricity consumption and raised by network operators. It considers that such system does not qualify as financed from State resources. |

2. DETAILED DESCRIPTION OF THE MEASURE

2.1. Overall objectives

|

(7) |

The KWKG aims at improving the energy efficiency of energy production in Germany by increasing the net electricity production from combined heat and power generation (‘CHP’) installations to 110 TWh/year by 2020 and to 120 TWh/year by 2025, as compared to the current yearly production of 96 TWh. |

|

(8) |

The KWKG also aims at ensuring cohesion between support for CHP and the goals of the energy transition (Energiewende). The KWKG therefore also supports new heat/cooling storage facilities or retrofitted storage facilities, as they increase the flexibility of cogeneration facilities, and focuses on installations that can reduce CO2 emissions in the electricity sector. CHP installations are expected to contribute to an additional reduction of 4 million tonnes of CO2 emissions (7) by 2020 in the electricity sector as in Germany electricity from cogeneration installations displaces separated production of electricity by coal-fired power plants. In addition, new coal-fired and lignite-fired CHP installations are not supported and support under the KWKG is essentially directed at gas-fired CHP installations as they have lower CO2 emissions. Bio-energy CHP installations are in theory also eligible for support under the KWKG but in practice they ask for support under the Renewable Energy Sources Act (EEG) under which support levels are higher. |

|

(9) |

Under the KWKG, aid can also be granted for the construction or expansion of heating/cooling networks. Support to the latter is viewed as a complement to CHP-support, given that using CHP installations in connection with district heating increases the energy efficiency of the system. |

|

(10) |

The district heating sector is expected to be the largest contributor to the aims of the KWKG; however, Germany has indicated that CHP installations used by the service sector and by the industry are also needed to achieve the objectives of the KWKG (8). |

|

(11) |

The reform of the KWKG is based on a cost-benefit analysis concluded in 2014 (9) in line with Article 14 of the Energy Efficiency Directive (10). The cost-benefit analysis identified potential for new CHP installations in Germany but showed that under current market conditions new CHP installations could not be constructed without aid at least until 2020. |

|

(12) |

The cost-benefit analysis also showed that depreciated gas-fired plants used for district heating could still technically be operated but could not generate sufficient revenue from the market alone under current market conditions. District heating companies typically operate both CHP installations and heat boilers to cover the heat demand. The companies are equipped with software that continuously verifies which combination of those installations will deliver the heat at the lowest cost. When electricity prices are low, production costs of CHP installations are higher than production costs of heat boilers; in those cases the heat boilers are used by preference to CHP installations for the heat production. While the average price for base-load electricity on the exchange was still around 50 €/MWh in 2010, it fell to 25 €/MWh in 2016 (11). Under those deteriorated economic conditions, existing gas-fired CHP installations in the district heating sector are under the threat of being closed and replaced by separate production installations (12). |

|

(13) |

In order to maintain the current production level of 15 TWh/year of existing installations in the district heating sector and possibly bring it back to a previous level of 20 to 22 TWh/year, Germany intends to grant support to existing gas-fired CHP installations in the district heating sector until 2019. |

2.2. The different support measures involved

2.2.1. CHP-support

|

(14) |

Under the KWKG, support is granted to new, modernised and retrofitted highly efficient CHP installations. It is open to various cogeneration technologies (including gas and steam turbines, Organic Rankine Cycle and fuel cells). |

|

(15) |

CHP installations qualify as highly efficient if they comply with the high-efficiency criteria of Directive 2012/27/EU (13) (§ 2(8) KWKG). |

|

(16) |

The CHP installation can be fired by biogas, biomass, natural gas, oil, waste and waste heat. The support level does not vary depending on the type of fuel used. As gas-fired CHP installations are the main focus of the KWKG 2016, the support level has been set by reference to typical costs of gas-fired CHP installations. Germany indicated in this connection that CHP installations using bio-energy were in practice supported under the EEG given that renewable support was higher than CHP-support. As to oil-fired CHP installations, Germany indicated that production costs for those installations are higher than for gas-fired CHP installations given that oil prices are significantly higher than gas prices (57 €/MWh for light oil compared to 23-24 €/MWh for natural gas). Concerning CHP installations burning waste, Germany explained that waste-fired CHP installations cannot use the most efficient CHP technology (GuD) but can only use steam processes, also the amount of electricity used by the CHP installation itself is higher than for gas-fired CHP installations (among others because it needs electricity to filter the waste gases). As a result, investment costs per installed kW are around 10 times higher for waste-fired CHP installations than for gas-fired CHP installations. Germany further indicated that waste incineration businesses were as a rule subject to public procurement. Competition to obtain the waste incineration concession is generally high. As a result the support for the CHP installation would also be integrated into the bid and any overcompensation can be excluded. |

|

(17) |

The support is paid as a premium (the ‘CHP-support’) on top of the market price by the network operator to which the installation is connected. Operators of CHP installations with an electrical capacity of more than 100 kW have to sell their electricity on the market or consume it themselves. Operators of smaller CHP installations have the choice to sell the electricity on the market, consume it themselves or ask the network operator to buy it at an agreed price. If no agreement is reached, the purchase price will be the average price for base-load electricity on the EEX exchange of the previous trimester. In this respect, Germany has communicated that it intends to amend this section of the KWKG so that in the future price agreements will no longer be allowed and the purchase price will in all cases be the above mentioned average price. |

|

(18) |

Operators of CHP installations are subject to balancing responsibilities like any other generator. Those responsibilities are laid down in the Electricity Grid Access Ordinance (Stromnetzzugangsverordnung — StromNZV (14)). |

|

(19) |

The support is paid in principle for CHP electricity injected into the public grid for 30 000 full load hours as of the moment the installation entered into operation. When the installation has an electrical capacity below or equal to 50 kW the support is granted for 60 000 full load hours. |

|

(20) |

Germany has explained that according to normal accounting rules the usual depreciation period of CHP installations is 20 years. CHP installations operate between 3 000 and 8 000 full load hours per year, depending on the size of the installation and the sector concerned. 30 000 or 60 000 full load hours would thus be reached at the latest after 10 or 20 years in the case of an installation running only during 3 000 full load hours/year. |

|

(21) |

The level of the subsidy is determined on the basis of the rates described in Table 1. Table 1 CHP-support for CHP electricity injected into the grid

|

|

(22) |

For two categories of operators support is also paid for the auto-consumed part of the electricity. Those are on the one hand operators of small CHP plants with an electrical capacity of up to 100 kW and on the other hand operators of CHP installations who qualify as electro-intensive users (EIU) eligible for a reduced EEG-surcharge under the EEG. In the latter case, the installation generally has a capacity above 100 kW. The CHP-support for those two categories is determined based on the rates described under Table 2. Table 2 CHP-support for auto-consumption

|

|

(23) |

Support is also paid to operators supplying CHP electricity to third parties but using a private network (industrial parks) if the supplied customer bears the full EEG-surcharge (§ 6(4)(3) KWKG). This also covers the situation of an operator (the ‘Kontraktor’) supplying electricity to third parties from an installation located on the premises of the client. In that case, the installation could be providing energy to a single client and the Kontraktor is in charge of the construction, operation and maintenance of the installation. The CHP-support for that category of operators is calculated using the rates described in Table 3. Table 3 CHP-support for ‘Kontraktoren’

|

|

(24) |

Modernised installations are existing CHP plants where old system parts relevant to determine the efficiency of the installation are replaced with new components. If the cost of such a modernisation exceeds 25 % or 50 % of a complete new construction of the cogeneration plant, this modernised plant is eligible for support under the KWKG (§ 8(3) KWKG 2016) respectively for 15 000 (when modernisation costs exceed 25 % of a complete new construction of the cogeneration plant) or 30 000 full-load hours (when modernisation costs exceed 50 % of a complete new construction of the cogeneration plant). The modernised CHP plants must provide sufficient evidence that they are more efficient than the old plants. Modernisation is eligible for support only if the existing system has reached a certain age (5 or 10 years respectively). The CHP-support is determined on the basis of the rates described in Table 1 above. |

|

(25) |

Germany has explained that modernised CHP installations face higher operating costs than new CHP installations. Due to continuous technological progress, new installations will require less repair and maintenance costs and consume less fuel than modernised installations. Given that capital costs represent only 20 to 25 % of total production costs of a CHP installation, once the modernisation costs reach a certain level (i.e. 50 % of the costs of a new investment), the difference in capital costs compared to a new installation is outbalanced by additional operating costs of the modernised installation. For that reason, modernised installations are entitled to the same level of subsidy as new installations when modernisation costs represent more than 50 % of the investment costs of a new installation. |

|

(26) |

Retrofitted installations are un-combined installations which are converted into CHP installations. They are eligible for support under § 8(4) KWKG 2016 if the costs of the retrofitting correspond to at least 10 % of a new CHP installation with the same capacity. Depending on whether the costs of the retrofitting exceed 10 %, 25 % or 50 % of a new CHP installation with the same capacity, the aid will be granted for 10 000, 15 000 or 30 000 full-load hours. |

|

(27) |

An additional premium of 0.3 € cent/kWh is granted under § 7(5) of the KWKG 2016 for CHP facilities subject to the Greenhouse Gas Emission Trading Law (TEHG) as they face higher costs compared to CHP installations not subject to the ETS system (‘§ 7(5) premium’). The § 7(5) premium has been established based on current and projected costs of CO2 allowances, typical emission factor of CHP installation and has also taken account of the fact that CHP installations partially benefit from free allowances under Article 10a (4) of the ETS Directive (15). In addition, in order to incentivize CHP plant owners to replace their existing coal-fired or lignite-fired plant with a gas-fired installation, a bonus of 0,6 € cents/kWh over the entire funding period (fuel switch bonus) is provided to operators for the part of the cogeneration electricity capacity of the installation that is replacing an existing coal-fired or lignite-fired CHP installation. The operator must demonstrate that the coal-fired or lignite-fired CHP installation has been closed within 12 months after the new installation started operation but at the earliest after 1 January 2016, he must also demonstrate that he owns both installations or that they are feeding the same heating network. |

|

(28) |

In order to minimise the administrative burden for micro-cogeneration units, owners of CHP in the power range of up to 2 kW can receive their support payments as a flat one-time payment. This corresponds to a subsidy of 4 € cent/kWh multiplied by 60 000 full load hours. |

|

(29) |

Operators of existing (depreciated) high-efficiency gas-fired CHP plants with an electrical CHP capacity of more than 2 MW can obtain a support of 1.5 € cents/kWh if i) the CHP electricity is injected into the public grid, ii) the installation was in general used for public supply and iii) the electricity is not supported anymore under the EEG or under other provisions of the KWKG. The support is limited in time (31 December 2019) and full-load hours (up to 16 000). |

|

(30) |

Germany has estimated that the support to existing installations will increase the number of operating hours of the installations concerned. Per installation, the increase in the number of annual operating hours can vary between 300 and 1 000 hours. In some cases, the support will also prevent that the installation is closed altogether. Germany submitted the example of an installation which without support would be able to operate under economically acceptable conditions for 37 hours in 2016 and 3 hours in 2017. With a support of 1.5 € cent/kWh, it would be able to increase its operating hours to 751 in 2016 and 553 in 2017 allowing for the operation of the installation to be maintained. |

|

(31) |

When the value of hour contracts is null or negative on the EPEX Spot SE exchange in Paris (price zone Germany/Austria), no premium will be paid out for the CHP electricity produced during those hours (§ 7(8) KWKG). The electricity generated during this period is not taken into account for the calculation of the number of full load hours during which support can be granted. |

|

(32) |

Aid for CHP installations can be cumulated with investment aid. However, in that case, the cumulation of the investment aid and the operating aid can never exceed the difference between the levelized cost of electricity produced in the CHP installation and the market price for the electricity. When the support is granted to beneficiaries selected in a tender (see section 2.7.2 below) and is cumulated with investment aid, Germany committed to deducting the investment aid from the operating aid in line with point 151, read in conjunction with point 129 of the Guidelines on State aid for environmental protection and energy 2014-2020 (16) (‘EEAG’). |

2.2.2. Storage of heat and cooling

|

(33) |

§ § 22-25 of the KWKG 2016 provide for investment support for the building of new or retrofitting of heat or cooling storage facilities. |

|

(34) |

While aid under the KWKG 2016 can also be granted when the owner of the storage and the CHP installations are different, Germany has indicated that storage facilities generally belong to the owner of the CHP installation to which it is connected. Storage facilities hence do no generate revenues. In addition, the increased flexibility of the CHP installation connected to the storage facility does not yield enough additional revenues for the CHP installation to trigger the investment into the storage facility. |

|

(35) |

Germany, however, would like to generalise the use of heat/cooling storage facilities in connection to CHP installations. Germany views those storage facilities as key elements to increase the energy efficiency and integration of CHP installations into the electricity market. As the heat/cold can be stored more easily than electricity (in the form of warm/cold water), CHP installations connected to storage facilities can adapt their production to produce in particular at times of higher electricity demand instead of cogenerating the electricity when there is heat demand but not necessarily electricity demand. A later heat requirement can then be covered from the storage facility. This flexibility allows CHP installations to run for an increased number of operating hours. Indeed, when electricity prices are too low, the heat demand is by preference produced from heat boilers and the CHP installation is not used or its production is reduced. The flexibility induced by the storage facility has therefore a direct environmental impact: the increased operation of CHP installations displaces separate production in heat boilers. In addition, in Germany, CHP electricity produced at times of high electricity demand displaces coal-fired electricity generation and thus significantly reduces CO2 emissions linked to electricity production. Finally, the induced flexibility also improves the integration of CHP installations into the electricity market as the electricity will be produced more in line with electricity demand. |

|

(36) |

In addition, storage facilities can also be filled with waste heat and renewable heat. As this type of heat is not necessarily produced when it is needed, the storage facility will increase the use of waste heat and renewable heat and reduce the need for heat only boilers. |

|

(37) |

Storage facilities are eligible for aid if the storage facility is mainly filled with heat produced by a CHP installation that is connected to the public electricity grid. Industrial waste heat and renewable heat are assimilated to CHP heat provided that the CHP heat still corresponds to at least 25 % of the stored heat. The storage facility must have a capacity of at least 1 m3 of water equivalent or 0.3 m3 per kW installed electrical capacity. |

|

(38) |

The aid amounts to 250 €/m3 water equivalent of the storage volume when the storage volume does not exceed 50 m3 water equivalent. This results in a maximum aid amount for small storage facilities of EUR 12 500. If it exceeds 50 m3 water equivalent, the aid is limited to 30 % of the eligible investment costs. In total the aid may not exceed EUR 10 million per project. |

|

(39) |

Eligible costs are all costs related to the construction of the storage facility and resulting from services and goods delivered by third parties. Not eligible are: administrative fees, internal costs for the construction and planning, imputed costs (‘kalkulatorische Kosten’), costs related to insurances, financing and land acquisition. |

|

(40) |

Germany has submitted an example of a concrete project for […] (*1) a heat storage installation. Its capacity would amount to […]m3 and project costs are estimated to amount to EUR […] million. The example shows that the aid makes it possible to increase the internal rate of return of the project from […]% to […]%. With only […]% projected internal rate of return the project would not have been implemented. |

|

(41) |

Aid for storage facilities under the KWKG 2016 can be cumulated with aid from local authorities, the Länder or other federal aid schemes. It is in principle deducted from the aid granted under the KWKG 2016 except if cumulation has been explicitly authorised. In that case Germany has committed to verifying that the cumulated aid would not exceed the aid intensity authorised under Annex 1 of the EEAG for cogeneration installations (17). |

2.2.3. District heating/cooling networks

|

(42) |

Under § § 18-21 KWKG 2016 support is granted for the construction and expansion of energy-efficient district heating/cooling networks (i.e. networks for the public supply of heat and/or cooling). |

|

(43) |

Those networks are eligible for support if they are fed with at least 60 % of a combination of cogenerated heat, industrial waste heat and/or renewable heat. In this case, the share of cogenerated heat must in any event correspond to at least 25 % of the transported heat. For networks which are fed with CHP heat which is not combined with industrial waste heat or renewable heat, Germany has committed to granting investment aid only if at least 75 % of the heat injected into the district heating network is produced by CHP installations. The aid is granted according to the aid intensities described in Table 4 below. Table 4 aid intensities for district heating/cooling networks

|

|

(44) |

Eligible costs are all costs related to the construction or expansion of the network and resulting from services and goods delivered by third parties. Not eligible are: administrative fees, internal costs for the construction and planning, imputed costs (‘kalkulatorische Kosten’), costs related to insurances, financing and land acquisition. |

|

(45) |

Germany has explained that for district heating/cooling networks the funding gap corresponds to between 30 % and 40 % of the investment costs, depending on the diameter of the pipes. It has submitted a detailed funding gap calculation for an average district heating system (town of 150 000 inhabitants, diameter >100 mm and aid amount of 30 % of investment costs, all values discounted with rate of 8 %). Table 5 below summarises the results of the funding gap calculation. Table 5 Summary of funding gap calculation for average district heating system

|

|

(46) |

In case of additional aid at local, regional or federal level, Germany has committed to verifying that the cumulated aid would not exceed the funding gap authorised under the EEAG, i.e. the difference between the positive and the negative cash flows over the lifetime of the investment, discounted to their current value (typically using the cost of capital) (see Point 19(32) EEAG). |

2.3. Production costs

|

(47) |

Germany has submitted Levelized Cost Of Electricity (LCOE) calculations for the production of cogenerated electricity in a series of representative installations for the district heating sector (one 10 MW, one 20 MW, one 100 MW, one 200 MW and one 450 MW installation) and 23 representative CHP installations used by households (single family houses or multiple family houses), service providers (retail, schools, hospitals, hotels) and the industry (construction of machines, car manufacturing, car repair, paper and chemistry sector). Germany has also provided LCOE calculations for CHP installations used by so-called contractors who operate a CHP installation to provide heat and power to a limited number of consumers (industry parks, for instance) as well as LCOE calculations for existing CHP installations. Finally they have also provided LCOE calculations for installations benefitting from the § 7(5) premium and the fuel switch bonus. All calculations concern gas-fired CHP installations. |

|

(48) |

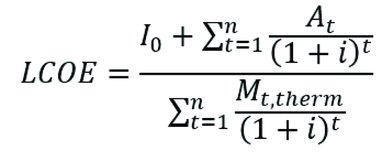

Germany has calculated the LCOE based on the following formula:

Where:

|

|

(49) |

For each calculation, Germany has also provided: the type of CHP installation used, the number of full load hours, the rate at which the installation is used for self-consumption (18), the sector concerned, the typical investment costs, the energy conversion efficiency rate, the heat and electricity outputs, and the fixed and variable operating costs. For the variable operating costs, Germany has further submitted the projected gas prices, electricity prices (both electricity price obtained when the electricity is injected into the grid and electricity price that is saved when the electricity generated is self-consumed), and the compensation for avoided network fees (19). The LCOE calculations also take into account reduced energy taxes and costs of CO2 emission allowances, where the installation is under the obligation to buy CO2 emmission allowances, and heat revenues. As far as heat revenues are concerned, Germany has taken the heat price into account for the district heating sector and the avoided heating costs for the other operators, since they would have had to buy or produce the heat in a boiler, had they not cogenerated it. The heat price obtained in the district heating sector has been computed based on the observation that the district heating sector needs to provide heat at the least cost possible as it has to compete with decentralized heat production. A CHP installation feeding heat into the grid is in competition essentially with gas boilers, other CHP installations and sometimes also incineration facilities or industrial heat. The heat price then corresponds to the marginal costs of the cheapest plant that is able to produce the demanded heat. For the purpose of determining the heat price taken into account for the LCOE calculations, Germany assumed that the heat demand would be covered 50 % by gas boilers and 50 % by CHP installations. |

|

(50) |

The tables below represent the assumptions used in terms of consumption, gas and electricity prices. Table 6 Typical consumption in the sectors examined by Germany

Table 7 Retail prices of gas to customers per category of consumer and consumption levels by 2050, real, gross calorific value, excluding VAT, duties and taxes in € cents 2013/kWh

Table 8 Electricity prices for households, commercial customers and industrial customers in € cents 2013/kWh

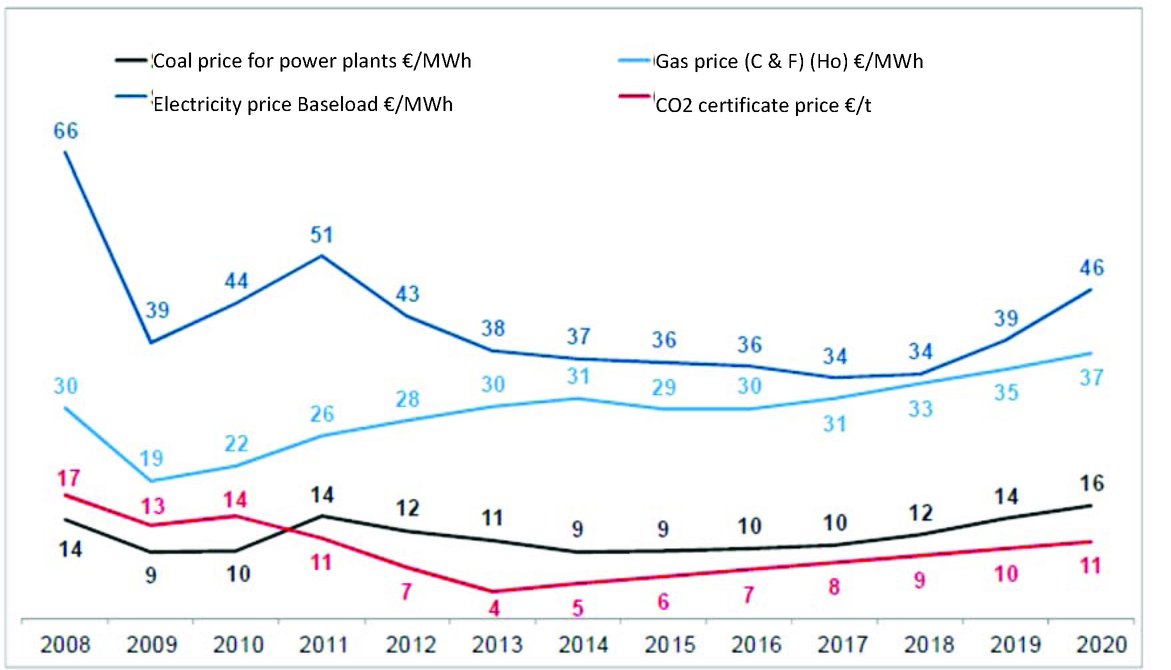

Table 9 Forecasted evolution of fuel and energy prices 2008-2020, nominal (source EEX 2014, Prognos 2014 from the CHP cost-benefit analysis).

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

(51) |

Germany has indicated that since Prognos made those forecasts for the purposes of the CHP cost-benefit analysis on the basis of which the reform was designed, the market situation has slightly changed, with electricity base-load prices (forward market, 2016-2019) having dropped to 28-29 €/MWh, the natural gas prices having also dropped to 23-24 €/MWh (Ho) at the end of 2015 but CO2 certificate prices having increased to 8.5 €/t. Germany noted that the drop in natural gas prices was more than compensated by the drop in electricity prices and the increase in CO2 emission certificate prices. |

|

(52) |

The following tables recap the resulting LCOE calculations. They include the rate of return of the investment taking into account the support under the KWKG when the installation is eligible for such support. They also contain a comparison with the average market price (average obtained from the market price of the energy injected into the grid and the market price of the electricity that would have had to be paid if the autoconsumed electricity had been purchased from a supplier) and with the support level. Table 10 Housing, up to 100 kWel, calculation over 10 year period (2016-2025) with a discount rate of 10 % per year — in € cents/kWh

Table 11 Trade and services, outside the BesAR, up to 100 kWel, 10 year period (2016 to 2025) with a discount rate of 20 % per year — in € cents/kWh

Table 12 Non electro-intensive industry (not eligible under BesAR, more than 100 kWel, 15 year period (2016-2030) up to 10 MWel and 20 year depreciation period (2016-2035) if more than 10 MWel; 30 % per year discount rate — in € cents/kWh

Table 13 Electro-intensive industry (eligible to BesAR) — 15 year period (2016-2030) up to 10 MWel and 20 year period (2016-2035) if more than 10 MWel; 30 % per year discount rate — in € cents/kWh

Table 14 LCOE calculations for projects implemented by contractors, outside the BesAR, larger than 100 kWel, over 15 years (2016-2030) up to 10 MW and over 20 years (2016 to 2035) above 10 MW, discount rate 30 % per year — in € cents/kWh (2013 values)

Table 15 LCOE district heating — new installations (with § 7(5) premium of 0.3 € cent/kWh) 20 year period (2016-2035) 8 % discount rate — in €/MWh

Table 16 LCOE district heating — new installations (with fuel switch bonus and including § 7(5) premium of 0.3€ cent/kWh)

Table 17 LCOE district heating — existing installation

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

(53) |

The calculations use the following discount rates: 8 % for the district heating sector, 10 % for households, 20 % for the service sector and 30 % for the industry. |

|

(54) |

For the district heating sector, Germany indicated that 8 % corresponds to the average rate of return observed in the sector. It submitted a survey based on actual projects and conducted by the Fraunhofer Institute for Manufacturing Technology and Advanced Materials (IFAM) showing that the average rate of return for the surveyed projects was 8.1 %. |

|

(55) |

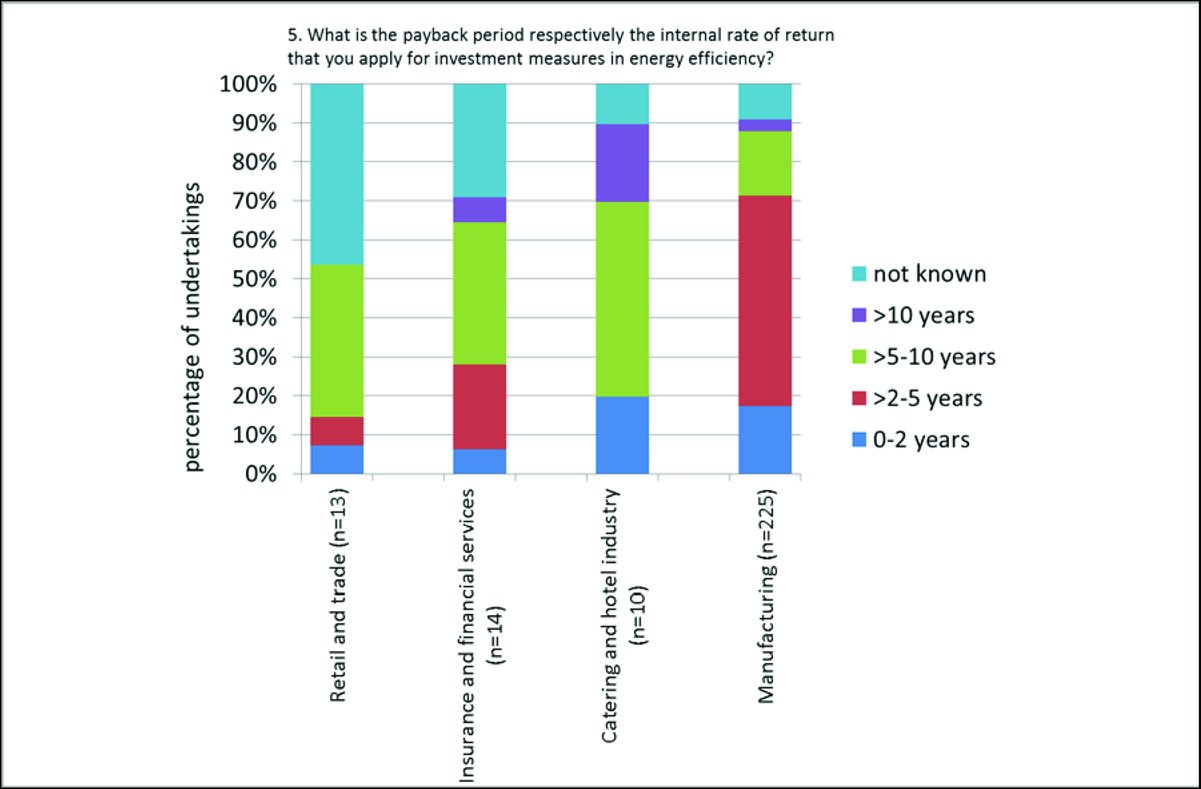

For households, the service sector and the industry, Germany has explained that the rates of return needed to trigger investments in those segments can vary greatly from one investor to another. For instance, while in the industry some project owners will engage into the project if it has a payback period of 5 years, others will require a payback period of 2 years. A 5-year payback period roughly equates to an annual project return of 20 % (20), a period of two years equates to an annual project return of 50 % and a payback period of three years equates to a project return of 33 %. |

|

(56) |

Based on this observation, when it designed the level of support Germany had to conciliate two objectives: on the one hand ensure that enough CHP projects outside the district heating sector would be incentivised so as to meet its target and at the same time maintain the budget of the scheme within a certain limit. The discount rates in the service sector and in the industry (respectively 20 % and 30 %) used by Germany correspond roughly to what a significant portion of project owners would require as project return to implement the CHP project in Germany. |

|

(57) |

Germany has submitted that the higher rates of return required by market participants in sectors other than the district heating can be explained by the fact that district heating companies are energy utilities and energy production belongs to their core business. The other sectors, however, are not specialised in energy production. While a more energy-efficient production could result in cost savings for them, it might also increase the complexity of operations. For those companies, the investment into the CHP installation does not constitute an investment into a side activity with its own costs and revenues but an investment having an impact on the production costs of the main activity of the company. Since operating a cogeneration installation is technically more complex than operating a heat boiler, investing in CHP projects will increase the risk of disrupting production. In addition, in most cases, the companies concerned, in particular in the industry, will have to invest into the CHP installation on top of a heat boiler that is needed to ensure security of energy supply in case the CHP installation is out of order or at times of maintenance. Companies would normally require higher rates of return to compensate for the additional risk. |

|

(58) |

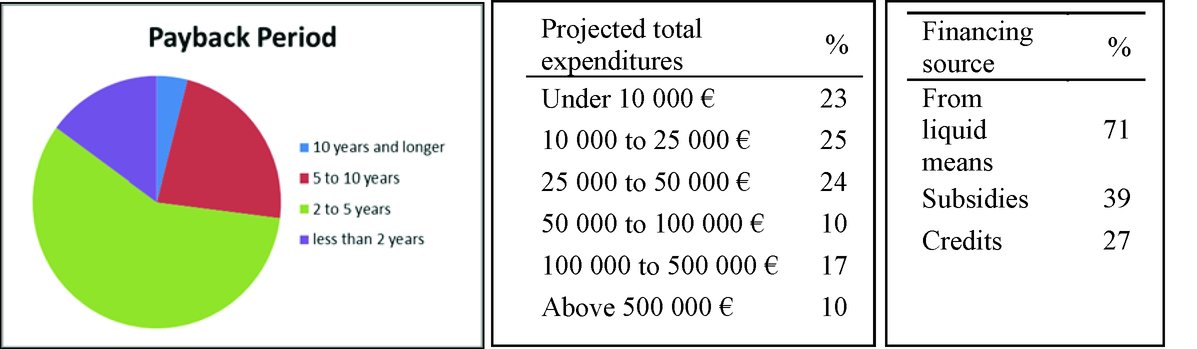

Germany has submitted several surveys of businesses and industrial plants confirming that in Germany many undertakings only accept relatively short payback periods, between 2 and 5 years. Graph 1 Payback period, projected total expenditures and financing sources — Source GfK 2014/GfK EEDL Monitor/Ergebnisbericht November 2014 Total/Subgroup: Planners of efficiency measures, weighted average, excluding no replies, in %.

Graph 2 Payback periods and rates of return of energy-saving investments — Source Prognos, IFEU, HWR Marktanalyse und Marktbewertung im Bereich Energieeffizienz (21)

|

|

(59) |

In 2015, the Association of Industrial Producers of Electricity (Verband der Industriellen Energie- und Kraftwirtschaft e.V. — VIK) has conducted a survey of its member companies on the issue of the profitability requirements for CHP projects. The following table presents the replies to the question: ‘What is your company's maximum acceptable payback period for projects in the field of energy supply, in particular the building or modernisation of plants for combined heat and power generation (CHP plants)?’ Table 18 Maximum acceptable payback periods

|

|

(60) |

Germany has also referred to a study commissioned by the Commission on Energy Efficiency and Energy Saving Potential in Industry from possible Policy Mechanisms (22). This study projected 2 output scenarios: a high and a low hurdle rate scenario. For the high hurdle rate scenario, the study uses a 2-year simple payback criterion as it has observed that this payback period represents a closer perspective of what industry might consider economically feasible. The study used a 5-year payback period in the lower hurdle rate scenario as projects with that longer payback period were often shortlisted but not implemented. |

|

(61) |

Finally, Germany has made a survey among CHP project owners. This survey shows that projects with a short payback period of 2 to 3 years (corresponding to a 50 % to 33 % rate of return) are realised while projects with payback periods above 4 years (25 % rate of return) tend to be abandoned — as shown below in Table 19. Table 19 Analysis of CHP projects in the industry

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

(62) |

Germany has also observed that CHP projects of more than 100 kWel implemented in the non-electro-intensive industry and used 100 % for self-consumption generally yield rates of return of more than 30 % without support. Those categories are excluded from support under the KWKG. |

|

(63) |

Finally, Germany has explained that, in the case of contracting, the LCOE calculations have made use of the same discount rate as if the project had been implemented by the consumer directly. The reason for this is that contractors themselves require lower rates of return because energy production and supply to third parties is their main business. However, a consumer will engage into energy contracting only if this yields certain savings for him. If the savings are too low, he will abandon the project altogether or implement it himself directly (without resorting to the Kontraktor). This means that the project itself must yield both savings for the consumer and a reasonable rate of return for the contractor. In other terms the rate of return of the project is spread between the contractor and the consumer. |

2.4. Monitoring of production costs

|

(64) |

Production costs will be examined on a yearly basis. Thereby, the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy will verify that the support level is adequate and does not exceed the difference between production costs of CHP electricity and the market price for the electricity. Should there be indications that the support level would exceed that difference, the Federal Ministry for Economic will inform the Parliament by 31 August of the relevant year and introduce an amendment to the law if need be (§ 34(1) KWKG 2016). |

2.5. Granting procedure, entry into force of the KWKG 2016 and duration

|

(65) |

Under the KWKG, support is paid out by network operators to operators of CHP installations, district heating/cooling networks and heat/cooling storage systems. In the case of CHP installations the payment responsibility rests on the distribution or transmission network operator to which the CHP installation is connected. In the case of district heating/cooling networks and storage facilities the responsibility rests on the transmission system operator to which the main CHP installation that feeds heat/cooling into the district heating/cooling network or the storage facility concerned is connected. The aid is paid out once the eligible installation or network enters into operation. |

|

(66) |

The beneficiaries are automatically entitled to support under the KWKG once all eligibility requirements of the KWKG are fulfilled. If they are fulfilled, the network operator concerned is obliged to pay out the support. Eligibility is verified by the Federal Office of Economics and Export Control (BAFA) upon request of the beneficiary. If all eligibility conditions are satisfied, the BAFA has to deliver a document confirming the eligibility (called a ‘Zulassung’). |

|

(67) |

The request submitted to the BAFA must contain the name and address of the operator, the description of the installation (installed capacity or size of the network/storage facility, fuel used, energy efficiency, costs), whether the electricity is injected into a public grid, date at which the installation entered into operation and more generally all information demonstrating that all eligibility conditions are met (including proof of compliance with high energy efficiency requirement). |

|

(68) |

In addition, in the case of district heating/cooling networks and storage facilities, Germany committed to verifying the incentive effect of the aid by requesting that the project owner also presents the counterfactual situation in the absence of aid. |

|

(69) |

The request is in principle introduced only after the start of operation as eligibility conditions are easier to verify when the installation is already in operation. Germany explained, however, that in case of complex projects, project owners would contact the BAFA in the planning phase and ask the BAFA to already provide a view on whether eligibility criteria are met before engaging into the project. Also operators can request a preliminary confirmation ‘Vorbescheid’ for CHP installations of more than 10 MW before they start building the installation. This will already confirm towards the operator the amount of the subsidy and its duration (§ 12 KWKG). A Vorbescheid can also be requested for district heating/cooling networks and heat/cooling storage facilities when project costs exceed EUR 5 million (§ 20(6) and § 24(6) KWKG 2016). |

|

(70) |

CHP projects are characterised by significant lead times between conception and starting of operations (23). Germany has explained that after a preparation and planning phase, projects will start once investors have verified that with the help of the support the project makes economic sense. They will then start the procedures to obtain building and environmental permits and will order the installation. For these reasons, while the KWKG 2016 entered into force on 1 January 2016 new projects entering into operation as of 1 January 2016 remain subject to the previous KWKG when it is demonstrated that certain parts of the project (for instance the ordering of the installation) were undertaken before 1 January 2016 given that those projects were undertaken based on the provisions of the previous KWKG (§ 35 KWKG 2016). |

|

(71) |

The KWKG 2016 will remain applicable to projects entering into operation at the latest by 31 December 2022. Germany indicated that the tender segment may require a longer applicability. |

|

(72) |

Certain provisions of the KWKG 2016 are subject to a standstill clause: no ‘Zulassung’ will be delivered for the projects listed below as long as the Commission has not approved the support scheme. Once it is approved, Germany indicated that payments would also relate to the CHP electricity produced since 1 January 2016 by the installation obtaining the ‘Zulassung’. The projects concerned by the standstill clause are:

|

|

(73) |

In addition, when the project owner of district heating/cooling network project is allocated more than EUR 15 million, the authorisation is issued only after Commission approval of the project (individual notification). The same applies when the CHP installation for which support is requested has an electric CHP capacity of more than 300 MW. |

2.6. The financing mechanism and the budget

2.6.1. The CHP-surcharge (KWK-Umlage)

|

(74) |

The measure is financed by a levy imposed on electricity consumption collected as a supplement to network charges (the so-called ‘KWKG-Umlage’). Network operators have to keep separate accounts in respect of the collected CHP-surcharge (§ 26 (1) KWKG). |

|

(75) |

The amount of the CHP-surcharge is calculated each year by the transmission system operators as a uniform rate per kWh consumed. Some categories of users benefit however from a reduced rate established in accordance with the CHP law. For consumers with a yearly consumption of more than 1 GWh (also called Category B consumers), the KWKG establishes a maximum CHP-surcharge of 0.04 € cent/kWh. The other category of consumers benefitting from a reduced CHP rate are consumers active in the manufacturing sector consuming more than 1 GWh and for which the electricity cost represents more than 4 % of turnover (also called Category C consumers). For the latter category of consumers, the KWKG establishes a maximum CHP-surcharge of 0.03 € cent/kWh (§ 26(2) KWKG). Consumers paying the full CHP-surcharge are called Category A consumers. |

|

(76) |

The current CHP-surcharge rates (in € cent/kWh) (24) are set out in Table 20 below Table 20 Current CHP-surcharge rates

|

|

(77) |

Based on the forecasts made by transmission network operators to determine the CHP-surcharge in 2016 (25), Germany has provided the following figures showing the relative size of each category and the importance of the reductions: Table 21 Relative share in consumption and in the CHP funding by each consumer category

|

|

(78) |

In order to make sure that each network operator is compensated for the extra costs resulting from his compensation obligation, the CHP law organizes a system by which the burden resulting from the purchase and compensation obligations is spread evenly between network operators in proportion to the consumption of consumers connected to their network and then compensated in the same way through the CHP-surcharge (which is proportionate to the consumption in their respective network, as well) (§ 28 KWKG). This system can be summarized as follows:

|

|

(79) |

§ 27 KWKG 2016 establishes the methodology to be used by transmission network operators to calculate the CHP-surcharge. The level of the CHP-surcharge is on the one hand a function of the projected aid amount (this projection is based on the estimates made by each network operator regarding the volume of CHP electricity eligible for support that would be produced in their network area and on the estimates made by the BNetzA on the subsidies to be paid out for storage and district heating/cooling networks) and the projected consumption by each category of consumers. On the other hand it will take into account corrections for preceding years. As the CHP-surcharge is calculated based on estimates, there could be a deviation between the forecasted aid amount and the aid amount actually paid out as well as a deviation between the forecasted consumption and the actual consumption. In year X, transmission network operators verify whether the estimated aid amount and consumption for year X-1 corresponded to the aid actually paid out and electricity consumed in year X-1 (see § 28(6) KWKG). If there are mismatches, it is corrected by a higher or lower CHP-surcharge in year X+1 (see § 27(3) KWKG, second part of the sentence). |

2.6.2. The maximum budget

|

(80) |

The KWKG sets a yearly limit to the budget of the scheme and hence the total CHP-surcharge (§ 29 KWKG ‘Begrenzung der Höhe der KWKG-Umlage und der Zuschlagzahlungen’). The yearly amount of support paid to CHP installations, storage facilities and district heating/cooling networks under the KWKG may not exceed EUR 1.5 billion. Of this amount, the yearly support for storage and district heating/cooling networks may not exceed EUR 150 million, except if estimates indicate that the total budget of 1.5 billion will not be exhausted. Once the maximum budget has been reached, further storage or district heating/cooling projects will obtain authorisation in the following year. |

|

(81) |

If on the basis of the estimates used to determine the level of the CHP-surcharge, it is established that the EUR 1.5 billion budget will be exceeded in year X+1, the support for all CHP installations of more than 2 MW of installed capacity will be reduced in the same proportion. This reduction will be compensated in the following years. Transmission system operators will have to warn the BAFA when they observe a risk of the budget being exceeded. The BAFA will then determine the reduced support rates and publish them (§ 29 (4) KWKG). |

2.6.3. Arguments presented by the Member State on reduced CHP-levies

|

(82) |

Germany has indicated that reductions from the CHP-surcharge were needed to ensure the international competitiveness of the companies concerned. It has also explained that previously reductions were granted already as of 100 000 kWh of consumption. This was however putting too heavy a burden on households and small undertakings and the threshold was therefore increased. Finally, it has explained that the reductions are needed in order to maintain the support as the support is only possible if the levies do not jeopardize the competitiveness of the companies concerned. Germany fears that the full surcharge could in the medium term lead to a deindustrialisation of Germany and possibly also Europe and adds that without the reductions the support as such as well as the objective of reduced CO2 emissions would not be accepted anymore. |

|

(83) |

Germany has further indicated that it had no data available on the beneficiaries and the impact on their production costs and gross value added. |

|

(84) |

However, as to Category C beneficiaries, Germany has indicated that most of them are likely to qualify as electro-intensive within the meaning of the ‘Besondere Ausgleichregelung’ under the EEG (BesAR). In that connection, Germany has indicated that companies benefitting from reduced EEG levies under the EEG were mainly active in the sectors set out in Table 22 below. Table 22 Overview of the sectors of the BesAR (Source: BAFA, May 2016)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

(85) |

Also, based on the data available for companies eligible to reduced EEG levies, Germany could simulate that the full CHP-surcharge (amounting to 0.255 € cent/KWh if no reductions were to apply) would represent between 1 and 9 % of GVA for a sample of around 100 companies eligible to reduced EEG levies and having a consumption above 1 GWh. |

|

(86) |

Germany submitted that it had no exact information on the sectors in which beneficiaries of Category B would be active but has indicated that companies of the manufacturing sectors generally had consumption above 1 GWh with the exception of the following sectors in which average consumption is below 1 GWh/a: Table 23 Overview of manufacturing sectors with average consumption below 1 GWh/a

|

|

(87) |

It also submitted the following simulation to illustrate the possible impact of a full surcharge on companies: Table 24 Simulation of the impact of a full surcharge

|

|

(88) |

Germany finally stressed that the burden of the CHP-surcharge adds to the burden already resulting from the EEG surcharge. |

2.7. Commitments

2.7.1. Imported CHP

|

(89) |

Germany has committed to opening the CHP-support to imported CHP electricity by allowing the participation of foreign operators in the CHP-support tenders (1-50 MW) described in section 2.7.2 as of Winter 2017/2018 on the basis of the following principles:

|

|

(90) |

Germany has further indicated that the necessary legal basis to empower the Government to open CHP-support would be adopted in 2016. The adoption of the necessary ordinance to implement the scheme, and thus the commencement of the opening up of funding, depend on the negotiations with the neighbouring countries. Germany committed to working towards a swift entry into force of such cooperation agreements. |

2.7.2. Tenders

|

(91) |

Germany has committed that as of Winter 2017/2018 support to installations with an installed capacity between 1 and 50 MWel will be granted to operators selected in tenders. Operators of installations with installed capacity between 1 and 50 MWel will continue to obtain the premium upon request directly on the basis of the KWKG, provided they have obtained authorisation under the Federal Act of Germany for Emission Control (Bundes-Immissionsschutzgesetz ‘BimSchG’) or have made a binding order of the CHP installation by 31 December 2016 at the latest. Germany also indicated that in case of modernisation, the binding order should refer to essential parts for efficiency of the installation. In addition, the installations concerned must be in operation by end of 2018. If all these requirements are fulfilled, this category of operators would have a choice to claim premium directly under KWKG or take part in tenders (opt-out solution). |

|

(92) |

The following CHP plants will not be subject to the tender requirement and will obtain the premium upon request directly on the basis of the KWKG:

|

|

(93) |

As to the scope of the beneficiaries, Germany submitted that participation in the tender will be subject to the condition that the entire electricity produced in the CHP installation is injected into the public grid. Thus, if the electricity produced by the CHP installation is directly consumed by the owner of the CHP installation or is injected into a private grid without being first injected into the public grid, the installation concerned will not be eligible to participate in the tender. Germany explained that self-consumed CHP electricity is eligible for a reduced EEG-surcharge and that the exclusion aims at ensuring a level playing field between the different groups of CHP producers. |

|

(94) |

Concerning installations with an installed capacity of more than 50 MWel, Germany has explained that while support was needed to further incentivise the construction of that kind of installations which are indispensable to reach its CHP and energy efficiency targets, allowing their participation in the tenders risks undermining the competitiveness of the tenders; it also risks increasing the level of support as a result of possible strategic behaviour in the tender by operators of very large installations. |

|

(95) |

The study of Prognos et al (2014) (26) has estimated the German CHP potential to include around 356 projects above 1 MW for a total of 3 450 MWel and 14 100 GWh/a between 2017 and 2022, based on historical data (projects <50 MWel) and information from project owners (projects >50 MWel). This would include only eight projects bigger than 50 MW totalling 2 100 MWel and 8 250 GWh/a, i.e. around 60 % of capacity and production. Of those eight projects, four are still in planning phase and expected to concern installations between 100 and 300 MWel, the others are more advanced and would in any event not be subject to the tender requirements (see recital (91) above). Table 25 Number, capacity and consumption of additional CHP plants (2017-2022)

|

|

(96) |

The eight projects above 50 MW of installed capacity in the district heating sector, mentioned in the table above, are the following: Table 26 Projects above 50 MW in the district heating sector planned for the period 2017-2022

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

(97) |

Germany has further submitted information showing that installations of more than 50 MW benefit from economies of scales leading to lower LCOE. For instance, for the same type of installation (GuD), the LCOE of a 20 MW installation is more than double the LCOE of 450 MW installations. Germany is concerned that if only a limited number of larger installations participate in a tender, such installations may bid strategically slightly below the LCOE costs of smaller installations (instead of submitting a bid reflective of their costs). This would result in the larger projects winning the tender and making windfall profits. |

|

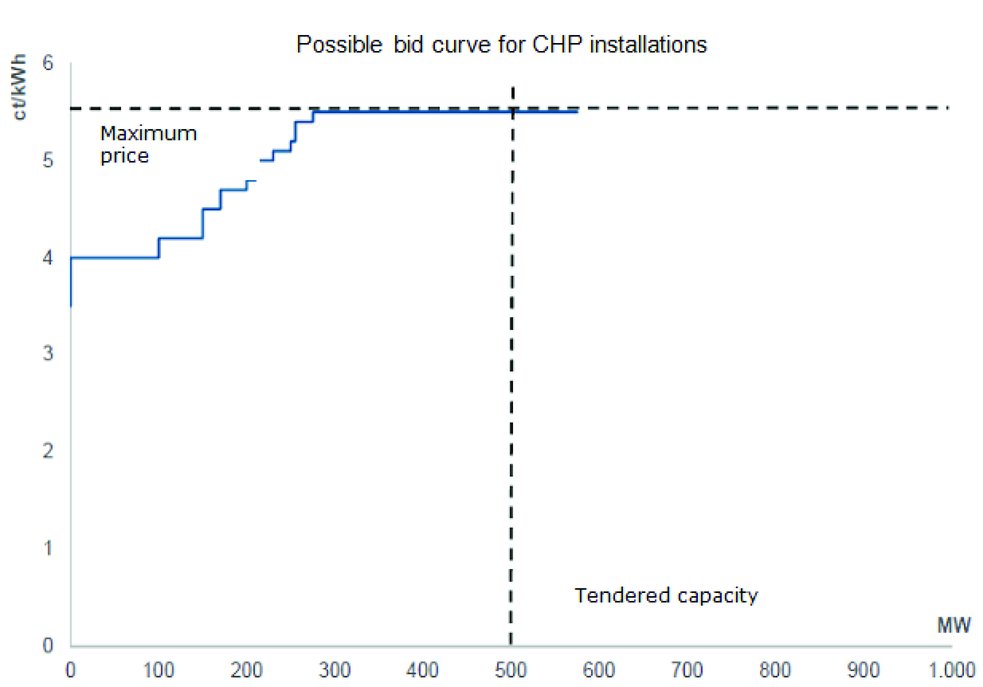

(98) |

The following graph illustrates a hypothetical scenario in which all CHP plants above 1 MW are taken into consideration and the tendered capacity amounts to 500 MW, out of an estimated annual potential of around 575 MW (including larger projects). In that scenario, several smaller projects take part in the tender and bid at the level of their LCOE. However, it is likely that those small projects alone would not be sufficient to deliver the whole tendered capacity. Therefore, the only larger project taking part in the bid will be needed to reach the tendered capacity. Graph 3 Hypothetical scenario for tenders for all CHP plants larger than 1 MW with only one larger project bidding in the tender.

|

|

(99) |

If the large project is aware of the situation, it will be able to bid at a level that corresponds to costs of smaller projects, which is higher than its own costs, and nevertheless be selected. |

|

(100) |

Germany has explained that larger project owners are in general better informed about other larger projects coming online soon (i.e., they have an asymmetric information advantage). First, part of the larger projects are developed by the same utilities, second given their limited number and their knowledge of the sector, they are able to perceive more easily in which tender another larger project might participate or not. As a result, they would likely be aware that they will be the only larger project to participate in the tender. They might also know that their large project will be needed to fill the capacity tendered out. |

|

(101) |

Germany has further submitted that even if in a given year several larger projects participate, they would have an incentive to bid just slightly below the costs of the smaller projects. Short of eliminating all the smaller projects, this will result in windfall profits for the larger projects. Graph 4 Hypothetical Scenario for tenders for all CHP plants larger than 1 MW with two larger project bidding in the tender.

|

|

(102) |

Germany has explained that tendering out a more limited capacity does not solve the issue in the sense that it would have to be very limited to create sufficient competitive pressure on the larger installations to make them bid at their LCOE. But in that case, a likely outcome would be that the larger project decides not to take part in the tender in a given year (preferring to wait for a larger tender), resulting in an undersubscribed and thus uncompetitive tender. In addition, if Germany organises too small tenders, it will not reach its environmental objective of 110 TWh/a by 2020 and 120 TWh/a by 2025. |

|

(103) |

Also, organising separate tenders depending on the capacity of the installations would imply the risk that the tender for larger installations is not competitive enough due to the very small number of projects and the information advantage that project owners of larger project have (capacity to estimate in which tender they are likely to be the only bidder). |

|

(104) |

Over the years, this could also discourage smaller projects to take part in tenders, as they will have experienced that they are likely to be eliminated if larger projects take part in the tender. This would further reduce the competitive tension in tenders, including in those years in which larger installations would not bid (which other participants would not know in advance). |

|

(105) |

As to retrofitted CHP installations, Germany has explained that those installations are not comparable to new and modernised CHP installations. Retrofitted installations get support for upgrading an existing uncoupled installation into a CHP one. This covers installations that previously were not CHP installations but have so far produced electricity or heat without combining the two processes. |

|

(106) |

In practice, the CHP-upgrade is an exceptional case. So far, there has only been one case in this category (27). There is thus not enough competition for organising specific tenders for retrofitted CHP installations. If retrofitted installations were to be bound to participate in tenders along with new installations, it is likely that these installations would gain significant windfall profits as the CHP-upgrade is in general far less costly than a new installation. |

|

(107) |

Germany has further committed to organize test tenders for innovative CHP systems. This tender would concern particularly innovative CHP systems that are going beyond CHP usual standards and which are developing because of higher production costs (combination of CHP installations with geothermal/PV thermal/heat pumps. The legislation would be adopted in 2016 (empowering act) and in 2017 (implementing act). The tenders would start in Winter 2017/2018. |

2.7.3. Other commitments

|

(108) |

Germany has committed to implementing all transparency requirements laid down in section 3.2.7 of the EEAG (publication on a comprehensive website of the text of the approved scheme, the identity of the granting authority and — except if the individual aid remains below EUR 500 000 — the identity of the beneficiaries, the form and amount of the aid, the date of granting, the type of undertaking, the region in which the beneficiaries are located and the principal economic sector in which beneficiaries have their activities). |

|

(109) |

Germany has further committed not to circumvent the waste hierarchy through the support to CHP installations. The waste hierarchy prioritizes the ways in which waste should be treated and consists of a) prevention, b) preparation for re-use, c) recycling, d) other recovery, for instance energy recovery and e) disposal. |

2.8. Evaluation of the scheme

|

(110) |

Germany has submitted an evaluation plan for the measure. The main elements of the evaluation plan are described below. |

|

(111) |

The evaluation plan notified by Germany envisages 23 evaluation questions in order to assess the scheme's outputs, its direct effects, its indirect effects (both positive and negative), as well as the proportionality of the aid and the appropriateness of the chosen aid instrument. |

|

(112) |

The evaluation will provide general information, in particular, on whether the scheme achieves its objectives, on the number and type of beneficiaries, on the tenders to be organised, and on the participation of operators located in other EU Member States under the opening of the tenders (see section 2.7.1 above). |

|

(113) |

The direct effects of the scheme will be evaluated, in particular, by assessing developments in the production of energy from cogeneration installations, in the construction or modernisation of eligible CHP installations and in investments in heat/cooling storage installations. |

|

(114) |

The main indirect effects of the scheme that will be evaluated are its contribution to the reduction of CO2 emissions, as well as its potential negative effects on the electricity market and on other electricity producers. |

|

(115) |

The appropriateness of the aid instrument will be evaluated by comparing the scheme with alternative approaches used in other EU Member States. The proportionality of the aid will be evaluated in particular by assessing the economic viability of the assisted projects. |

|

(116) |

Evaluation questions related to the general outputs of the scheme will be mostly answered by providing quantitative statistical evidence, whereas questions related to the scheme's indirect effects and appropriateness of the aid instrument will be addressed through qualitative assessments supported where appropriate by quantitative analysis. To evaluate the direct effects of the scheme, Germany has committed to further extending the methodology used so far in the evaluation reports by employing, to the extent possible given data availability, counterfactual impact evaluation methods in line with the Commission Staff Working Document on Common methodology for State aid evaluation (28). In particular, where appropriate, the identification of suitable ‘control groups’ of similar non-assisted projects will be pursued in order to rigorously estimate the causal impact of the aid on its beneficiaries. |

|

(117) |

In order to perform the evaluation, Germany has committed to making available the detailed data collected throughout the scheme's implementation by the BAFA. General energy statistics will also be used, as well as some targeted qualitative information and ad hoc studies. The usual data protection rules apply. |

|

(118) |

Germany has committed to submitting the evaluation report to the Commission in 2021. |

|

(119) |

The evaluation will be conducted by an external independent evaluator to be selected through an open tender procedure. Germany has committed to duly considering the relevant experience of the tender applicants notably in the field of quantitative evaluation methods. |

|

(120) |

The evaluation report will be published on the website of the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (29). According to Germany, the evaluation results will be an important basis for optimising or refocusing the scheme in the future. |

3. ASSESSMENT

3.1. Existence of aid

|

(121) |

Article 107 (1) TFEU provides that ‘any aid granted by a Member State or through State resources in any form whatsoever which distorts or threatens to distort competition by favouring certain undertakings or the production of certain goods, shall, in so far as it affects trade between Member States, be incompatible with the common market’. |

|

(122) |

The Commission has identified the following measures and has found that each of them constituted an aid measure within the meaning of Article 107(1) TFEU for the reasons set out in sections 3.1.1 to 3.1.3 below:

|

3.1.1. Selective advantage

|

(123) |

For CHP installations, the aid takes the form of a premium that producers of CHP electricity obtain either in addition to the market price of the electricity they sell on the market or for the electricity they have used for their own consumption. It constitutes an advantage that operators would not have obtained under normal market conditions. It is also selective given that it is granted only to a certain sub-sector (CHP electricity production) or for the autogeneration of CHP electricity in certain sectors only (autogeneration in CHP installations of not more than 100 kW and autogeneration in certain electro-intensive manufacturing sectors, see recital (22) above). |

|

(124) |

In the case of heat/cooling storage installations and district heating/cooling networks, the aid takes the form of a direct grant covering part of the investment costs, which constitutes an advantage that the operators would not have obtained on the market. It is also selective as it favours only certain sectors (i.e., the district heating and/or district cooling sector and, for the aid to storage facilities, which are meant to be connected to CHP installations, the same companies/sectors as the aid for CHP electricity itself; in addition, the latter could also favour the development of a new sector, viz. providers of storage services). |

|

(125) |