EUROPEAN COMMISSION

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Brussels, 27.2.2019

SWD(2019) 1026 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

Country Report Sweden 2019

Including an In-Depth Review on the prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances

Accompanying the document

COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE EUROPEAN COUNCIL, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK AND THE EUROGROUP

2019 European Semester: Assessment of progress on structural reforms, prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances, and results of in-depth reviews under Regulation (EU) No 1176/2011

{COM(2019) 150 final}

Contents

Executive summary

1.Economic situation and outlook

2.Progress with country-specific recommendations

3.Overall findings regarding imbalances, risks and adjustment issues

4.Reform priorities

4.1.Public finances and taxation

4.2.Financial sector and housing market

4.3.Labour market, education and pillar policies

4.4. Competitiveness reforms and investment

Annex A: Overview Table

Annex B: Commission Debt Sustainability Analysis and fiscal risks

Annex C: Standard Tables

Annex D: Investment Guidance on Cohesion Policy Funding 2021-2027 for Sweden

References

LIST OF Tables

Table 1.1:Key economic and financial indicators – Sweden

Table 2.1:Summary table on CSR assessment

Table 3.1:MIP assessment matrix (*) — Sweden 2019

Table 4.2.1:Financial soundness indicators, all banks in Sweden

Table C.1:Financial market indicators

Table C.2:Headline Social Scoreboard indicators

Table C.3:Labour market and education indicators

Table C.4:Social inclusion and health indicators

Table C.5:Product market performance and policy indicators

Table C.6:Green growth

LIST OF Graphs

Graph 1.1:

Output gap, real GDP growth and its components

Graph 1.2:

Contributions to potential growth

Graph 1.3:

Labour shortages in the economy

Graph 1.4:

Relative change in working-age population due to increased inflows of asylum seekers between 2014 and 2017 in Europe

Graph 1.5:

Breakdown of rate of change of unit labour costs (ULC)

Graph 1.6:

Real Effective Exchange Rate based on unit labour costs

Graph 1.7:

Net international investment position

Graph 2.1:

Overall multiannual implementation of 2011-2018 CSRs to date

Graph 4.1.1:

Swedish fiscal rules and MTBF and EU average

Graph 4.1.2:

Impact of fiscal rules and MTBF on the cyclically-adjusted primary budget balance

Graph 4.1.3:

Swedish fiscal rules index and government gross debt

Graph 4.2.1:

House prices by market segment (nominal)

Graph 4.2.2:

Estimated house price valuation gaps based on different indicators

Graph 4.2.3:

Revenues from property taxes

Graph 4.2.4:

Housing starts, including net conversions, versus projected need

Graph 4.2.5:

Construction sentiment: overall confidence indicator and expectations component

Graph 4.2.6:

Labour and material cost evolution in new residential construction (total % rise between 2015-2018Q2; not annualised)

Graph 4.2.7:

Time on waiting list before obtaining primary tenancy in greater Stockholm (distribution by number of years)

Graph 4.2.8:

Household debt evolution (indexed, 2005=100)

Graph 4.2.9:

Share of new mortgage borrowers by debt-to-disposable-income ratio

Graph 4.2.10:

Amortisation rate for mortgages

Graph 4.2.11:

Year-on-year growth rate in mortgages and unsecured loans to households

Graph 4.2.12:

Household financial assets (*) and stock market index

Graph 4.2.13:

Breakdown of corporate debt by funding source

Graph 4.2.14:

Leverage indicators for non-financial corporations

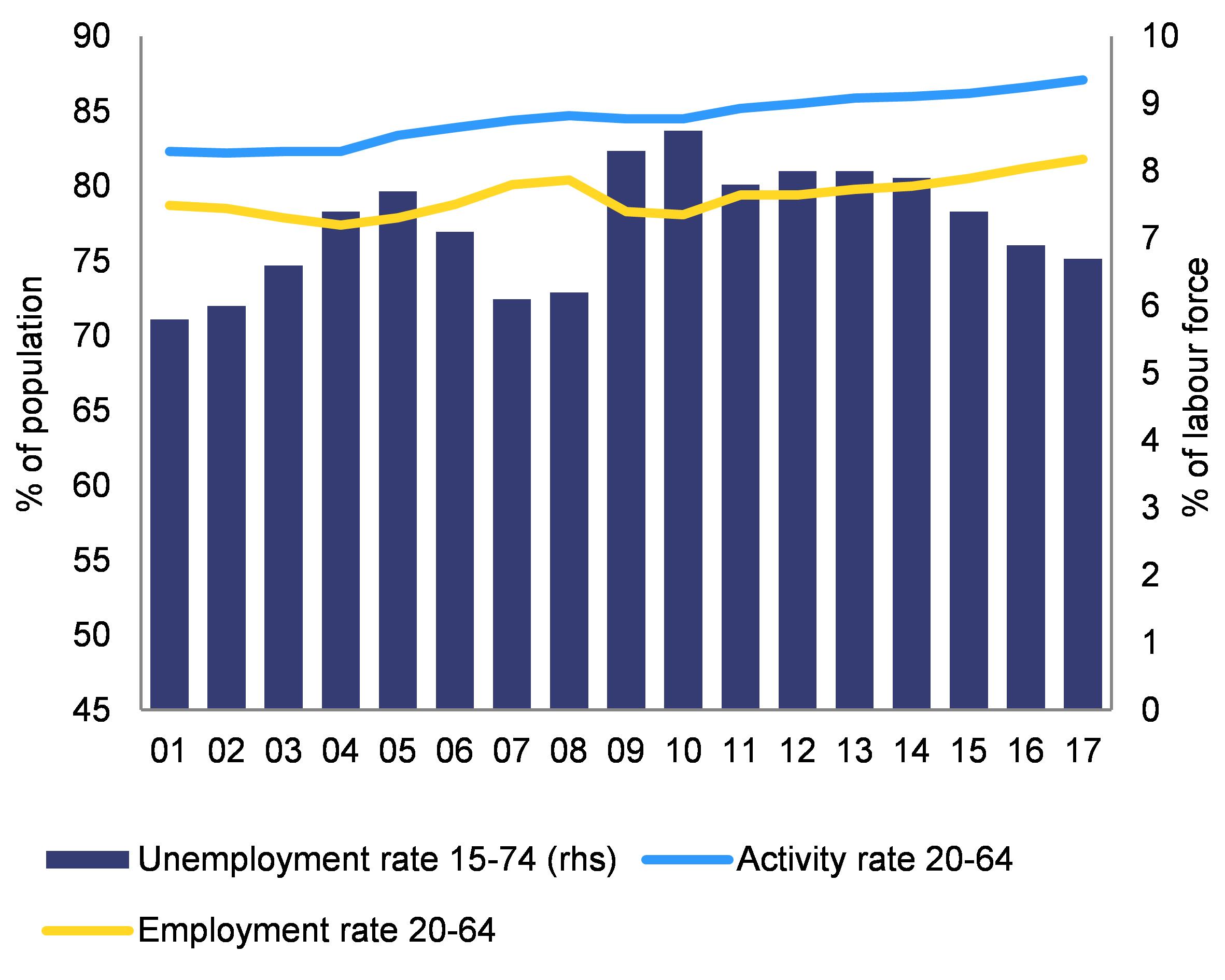

Graph 4.3.1:

Activity, employment and unemployment rates

Graph 4.3.2:

Unemployment rate by educational attainment

Graph 4.3.3:

Employment rate by citizenship

Graph 4.3.4:

At-risk-of-poverty or social exclusion rate and its components

Graph 4.3.5:

Proportion of low achievers in OECD PISA (2015)

Graph 4.3.6:

Proportion of graduates by programme orientation (2016)

Graph 4.4.1:

Cumulative export market share loss since 2007 for Sweden and selected peer countries

Graph 4.4.2:

Gross fixed capital formation (% of GDP)

46

LIST OF Boxes

Box 2.1: EU funds and programmes contribute to addressing structural challenges and to fostering growth and competitiveness in Sweden

Box 4.3.1: Monitoring performance in light of the European Pillar of Social Rights

38

Box 4.4.1: Investment challenges and reforms in Sweden

Executive summary

Sweden’s overall economic performance remains healthy, but mounting risks highlight the importance of addressing structural weaknesses. The housing shortage, long a key challenge, is the result of insufficient new housing construction compounded by demographic developments. Boosting construction in appropriate locations and market segments could help alleviate this. A more market-oriented rental housing sector could also help, and would underpin mobility and flexibility in the labour market. Tax incentives for property ownership and mortgage debt are aggravating the problems of growing household debt and overvalued house prices. Addressing these issues would make the Swedish economy more resilient and reduce risks posed by imbalances ().

Economic activity remains solid but is expected to moderate. According to the Commission’s winter 2019 interim forecast, real GDP grew by 2.1 % in 2017 and is set to have increased by 2.2 % in 2018. With the global economy slowing down and residential investment in Sweden starting to fall, economic activity is set to shift to a lower gear. Real GDP growth is expected to slow over the forecast period and reach 1.7 % in 2020. Over the longer run, potential growth is expected to remain below pre-crisis levels in light of continued modest productivity growth, in line with global developments.

Sweden’s external position continues to be strong. Growth in goods exports remained solid in 2018. Imports rose strongly, however, due to strong domestic demand resulting in a lower current account surplus. Exports of goods and services are likely to expand by around 3 % in 2019-2020 against the backdrop of trade tensions and as growth in Sweden’s main trading partners eases. The current account surplus is forecast to stabilise at around 3 % of GDP.

Investment growth is slowing as residential investment adjusts to lower levels. A fall in housing prices in the second half of 2017 is expected to reduce the construction of new housing, dampening growth in investment. In addition, investment in equipment is set to lose speed as trade-related uncertainty weighs on external demand and adds to already lacklustre business sentiment.

The labour market is performing well but faces challenges. Sweden has one of the highest employment rates in the EU (83.3 % in Q3 2018) and the Commission’s autumn 2018 forecast expects unemployment to level out at 6.2 % in 2019-2020. At the same time, labour shortages and skills mismatches, where the jobs available do not match the skills of the jobless, prevent unemployment from falling much further. A major challenge will be to successfully integrate non-EU migrants into the labour force in a way that will benefit growth in the long term.

The fiscal position is strong. In 2017, the general government overall surplus was 1.6 % of GDP. A smaller surplus of around 1 % of GDP is expected for 2018, and this should decline to 0.8 % of GDP in 2020 as the economy slows. Public debt is set to continue declining due to prudent fiscal management and a strengthened fiscal framework.

Monetary policy is normalising, due to inflation picking up somewhat from previous lows. Monetary policy has remained accommodative for years due to low inflation. After an increase in core inflation in 2018, the Riksbank began increasing its benchmark interest rate in late 2018 and has announced that further rate hikes could follow.

Strengthening investment () in new housing, education and skills could further enhance Sweden’s long-term growth potential. It would also be beneficial to maintain investment in transport infrastructure and innovation. The investment rate in Sweden has stood well above the EU average for the last decade; nevertheless, some parts of the economy could benefit from more investment. A structural undersupply remains in the housing market, despite a significant increase in new construction over the past 5 years. In the education system, demographic developments will lead to an increase in the number of pupils, while the country already faces a teacher shortage. Investment in education and skills will also be crucial to help boost productivity growth and address the skills mismatch in some parts of the labour market. Finally, there is a need to maintain investment in transport infrastructure and Research and Development at high levels to support long-term productivity growth and to fully exploit business potential. Annex D identifies key priorities for support by the European Regional Development Fund and the European Social Fund Plus over 2021-2027, building on the analysis of investment needs and challenges outlined in this report.

Sweden has made limited () progress in addressing the 2018 country-specific recommendation.

There has been some progress in the following area:

·Sweden is moving forward with policy steps to stimulate residential construction. This includes the gradual implementation of the ‘22-point plan’ for the housing sector, as well as measures to boost foreign competition in the construction sector (see Section 4.2.2).

There has been limited progress in the following area:

·In January 2019, the Swedish authorities announced that reforms will be prepared to make the rent-setting system more flexible. There are also plans to make deferred capital gains taxes on sold properties in the owner-occupancy market interest-free.

There has been no progress in the following areas:

·No progress has been made on reforming the favourable tax treatment of mortgage debt and home ownership.

Regarding progress towards its national targets under the Europe 2020 strategy, Sweden continues to perform well in the following indicators: employment rate, greenhouse gas emissions, share of renewable energy, tertiary education attainment and poverty risks. Areas where progress remains relatively weak are early school leaving, energy efficiency and Research and Development targets.

Sweden performs well on the indicators of the Social Scoreboard supporting the European Pillar of Social Rights. The employment rate is high, while the gender employment gap and the share of young people not in employment, education or training are at low levels. Positive outcomes, such as the level of digital skills and impact of social transfers on poverty reduction reflect an advanced welfare model with a strong social dialogue.

The main findings of the in-depth review contained in this report and the related policy challenges are as follows:

·While banks are healthy, some vulnerabilities are linked to their growing exposure to the real estate market. Banks remain profitable. The regulatory capital adequacy ratios are healthy, though they decreased at end 2018 due to changes in the calculation of banks’ risk-weighted assets. The major Swedish banks showed resilience in the 2018 stress test conducted by the European Banking Authority. The banks’ high level of lending to the real estate market remains a key risk and households remain vulnerable to an adjustment in the housing market and an increase in interest rates. Moreover, since Swedish banking groups are of systemic importance for all countries in the Nordic-Baltic financial market, any shock to the banking sector could have a wider impact on neighbouring countries.

·Household indebtedness has continued to rise from already high levels. Household debt grew by 5.5 % in 2018, reaching about 88 % of GDP and 186 % of disposable income, which is among the highest in the EU. This was driven mainly by higher mortgage borrowing linked to high house prices, coupled with structural distortions favouring mortgage-financed property purchases. Sweden has implemented several macro-prudential measures in recent years, including a strengthened repayment rule for high debt-to-income mortgages in force since March 2018, and a decision to raise the countercyclical capital buffer for banks from September 2019. However, the policy steps taken so far appear to have had limited overall impact on the growth of mortgage lending.

·While house prices declined in late 2017 and have since been broadly stable, this follows a long period of strong price rises, and valuations remain well above fundamentals. Key issues include tax incentives favouring home ownership and mortgage debt, and accommodative credit conditions coupled with still relatively low mortgage repayment rates. Despite a sharp rise in new construction, a shortage remains, particularly of affordable homes around major cities. This shortage is linked to structural inefficiencies, such as limited competition in the construction sector. The housing stock is not used efficiently. In the rental market, below-market rents create lock-in and ‘insider/outsider’ effects. In the owner-occupancy market, capital gains taxes reduce homeowner mobility. The housing shortage makes it harder for people to change jobs and can contribute to intergenerational inequality.

·The continued increase in household debt and bank residential mortgages are a growing risk to macroeconomic stability. Despite gradual policy action, mortgage debt continues to grow. With the housing market still appearing overvalued, even after the declines in autumn 2017, rising indebtedness means there is a growing risk of a disorderly correction. This could have an adverse impact on the economy and potentially the banking sector.

Other key structural issues analysed in this country report, which point to particular challenges facing the Swedish economy, are the following:

·Despite favourable economic conditions, some population groups have difficulties finding a job. Sweden is a top performer in the EU for high employment and low long-term unemployment rates. Challenges remain, however, such as the integration of low-skilled people and non-EU migrants into the labour market. This challenge is likely to remain in the coming years in the light of number and composition of the arrival of asylum seekers who arrived in late 2015. Efforts have been made to improve their employability for instance via the ‘Introduction job’ (Introduktionsjobb) programme.

·The educational performance gap between different social groups is large and widening. Despite recent measures, the education system does not appear to promote quality education for all. The integration of foreign-born migrant pupils warrants close monitoring. Another challenge is the growing shortage of teachers.

·The economy benefits from a favourable business environment, although specific barriers to investment and long-term growth remain. The country performs well in terms of efficient public administration, access to finance for small and medium-sized enterprises, and innovation and internationalisation by businesses. However, investment and innovation could benefit from a closer cooperation between academia and business.

1.

Economic situation and outlook

GDP growth

Economic activity remains solid. Real GDP grew by 2.1 % in 2017 and is expected to have increased by 2.2 % in 2018, according to the Commission’s winter 2019 interim forecast. Domestic demand was the main growth driver, benefiting from the continued accommodative monetary policy and growing employment, which is supporting consumption. The growth contribution of net exports was modest and imports remained strong (Graph 1.1).

|

Graph 1.1:Output gap, real GDP growth and its components (1)

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|

After years of robust growth, GDP is forecast to moderate. With the global economy entering a lower-growth period and residential investment in Sweden starting to fall, economic activity is set to slow down. Real GDP growth is projected to slow to 1.3 % in 2019 before picking up somewhat to 1.7 % in 2020, close to the economy’s potential of around 2 %.

Residential investment, a key growth driver, is expected to adjust to lower levels. After a peak in mid-2017 house prices declined in the second half of the year and have remained largely unchanged. The decline had a negative impact on sentiment in the construction sector and new housing starts are expected to fall holding back investment growth. In addition, investment in equipment is set to lose speed as trade-related uncertainty weighs on external demand and adds to already lacklustre business sentiment. Overall, investment growth is forecast to slow markedly until 2020.

Public and private consumption growth is set to remain moderate. In 2018 private consumption was supported by high employment gains. Over 2019-2020, however, it is forecast to grow less as employment growth is set to slow given the already high level of labour force participation. Public consumption is projected to have increased by close to 1 % in 2018 due to municipalities having been given more resources to employ additional staff and to improve the delivery of welfare services and education. Assuming no policy change, public consumption is expected to grow at around the same pace in the coming years.

Potential growth

Potential growth has recovered but is expected to be below pre-crisis levels. In the wake of the crisis, recovery in potential output growth was mainly due to the rising contribution of labour thanks to increasing participation among the young, old, and foreign born (Graph 1.2). However, the labour contribution is expected to fall as migration levels taper off from their 2015 peak and also due to negative demographics. The contribution of total factor productivity is projected to remain modest and below pre-crisis levels, in line with global developments, weighing on potential growth while capital accumulation is expected to remain stable.

|

Graph 1.2:Contributions to potential growth (1) (2)

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission (Autumn forecast 2018)

|

Inflation and monetary policy

Headline inflation is not yet firmly anchored but core inflation is set to increase gradually. In 2018, higher import prices resulting from the depreciation of the Swedish krona, surging energy prices and a pick-up in unprocessed food prices (due to unusually dry weather in 2018) pushed inflation above the Riksbank 2 % target in the second half of the year. As these temporary factors fade away, the harmonised consumer price index is expected to grow at 1.7 % in 2019 before edging down to 1.6 % in 2020. Core inflation (excluding food and energy) is set to increase from slightly above 1 % on average in 2018 to around 1.5 % in 2020.

With inflationary pressures rising, the Riksbank increased its repo rate in late 2018. Monetary policy has remained accommodative for years now, as low inflation prompted a postponement of rate hikes. The Riksbank had kept its repo rate unchanged at 0.5 % since February 2016. In December 2018, the Riksbank raised the repo rate by 0.25 percentage points and announced that subject to inflation prospects rate hikes of about 0.25 percentage points once or twice a year could be expected. Such a gradual increase would keep the real repo rate negative for the next two years. While in the past the low nominal interest rate environment was one factor behind the increase in household debt and house prices, a gradual reversal, with rising debt servicing costs, could have a dampening effect on credit growth and consumer spending (see Section 4.2.3).

Private indebtedness

Household debt continued to rise, increasing by 5.5 % year-on-year in December 2018. While this is a continued gradual slowdown from its peak growth rate of close to 8 % around mid-2016, it remains well above nominal income growth (see Section 4.2.3). Overall, household debt stood at 186 % of disposable income or about 88 % of GDP in Q3 2018, among the highest levels in the EU. Importantly, the distribution of debt among households is becoming increasingly uneven, with the fraction of new mortgage borrowers with very high debt-to-disposable income ratios above e.g. 600 % growing to 17.2 % in 2017 (vs. 16.4 % in 2016, and about 12 % in 2013).

Labour market

The Swedish labour market continues to perform well. Sweden has one of the highest employment rates in the EU (83.3 % in Q3 2018), and employment growth is set to remain solid. Unemployment has been below the EU average and is expected to level out at 6.2 % in 2019-2020 according to the Commission’s autumn 2018 forecast. Long-term unemployment remained low at 1.2 % in 2017. Youth unemployment continued to decline and the proportion of young people not in employment, education or training decreased to 6.2 % in 2017.

At the same time, labour shortages and skills mismatches prevent unemployment from falling much further. Labour force participation continued to increase in 2017 and 2018. However, labour shortages are rising despite the increase in labour supply. The Public Employment Service forecasts a continuing shortage of labour in the coming years in roughly 150 out of the 200 professions it covers. These professions include ones requiring higher levels of educations such as engineers, teachers, IT specialists and persons working in the health sector. Moreover, the employment rate of low-skilled people remains low, which indicates potential skills mismatches (Graph 1.3). Unemployment is therefore set to stabilise at around 6.2 % in 2019-2020.

|

Graph 1.3:Labour shortages in the economy (1)

|

|

|

|

Source: Public Employment Office

|

Migration is the main factor driving the growth of the labour force. In 2016 net migration to Sweden reached over 117 000, the highest on record. In 2017, however, it dropped to just below 99 000. This was linked to temporary border controls and the temporary migration act of 2016 which the new government intends to extend by two years (until the end of 2021) to examine the future migration policy in a parliamentary inquiry. The participation rate of migrants in the labour force increased by around 1.3 percentage points in 2017 (OECD, 2018d). The OECD estimates that refugee arrivals will have a positive effect on the labour force, with at least a 0.5 % increase cumulatively between 2017 and 2020. In addition, the net positive effect on the working-age population may reach at least 0.8 % cumulatively between 2017 and 2020 (Graph 1.4) (). Without migration, the labour force and ultimately potential GDP would be negatively affected. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (Hilgenstock, 2018), a no-migration scenario in Sweden would lead to a decline in labour force participation of around six percentage points in 2015-2050.

|

Graph 1.4:Relative change in working-age population due to increased inflows of asylum seekers between 2014 and 2017 in Europe (1, 2)

|

|

|

|

Sources: Eurostat, OECD estimates

|

The successful integration of non-EU migrants into the labour force is key to ensuring benefits to long-term growth and fiscal sustainability. Migration helps maintain the population and labour force growth in the face of an ageing population since it tends to be concentrated among younger and economically active age groups. Half of those who immigrated between 2006 and 2017 have post-secondary education, which is higher than among migrants who immigrated before 2006 and people born in Sweden. Persons who immigrated in the last twelve years have a younger age structure than the population aged 25-64 years as a whole, which can partly explain the high level of education compared to the Swedish population (Statistics Sweden, 2018c). The Swedish authorities have identified finding jobs or training places for migrants as a key priority and have taken steps to reduce asymmetries in the labour market between foreign born and native born (see Section 4.3.1).

Inequality

Inequality and poverty levels are low. The incomes of the richest 20 % of the population were around 4.3 times higher than the incomes of the poorest 20 % in 2017. The distribution of market incomes is relatively equal, due to compressed wage distribution. In addition, taxes and transfers have an equalising effect, which is among the largest in the EU (58.5 % in 2016). The share of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion is lower than the EU average. The share of people in severe material deprivation and the share of people living in low work intensity households have not decreased despite rising employment.

Competitiveness

Contained wage growth has supported the economy’s competitiveness. In 2017, the industrial sector, exposed to foreign competition, agreed to a 2.2 % annual increase in wages for 2017-2019. Wage growth for the economy remained stable averaging around 2.4 % in 2017-2018 despite a tightening labour market and expectations of rising inflation. Unit labour costs (ULC) have broadly followed trends in labour productivity and are around the EU average (Graph 1.5), thus safeguarding competitiveness. Accordingly, the ULC-based real effective exchange rate depreciated during the same period (Graph 1.6). The new negotiation round for 2020-2023 is expected to result in moderate wage increases, which should preserve cost competitiveness. Conversely, nominal unit labour costs are expected to rise by 1.8 % in 2019 and 1.3 % in 2020.

|

Graph 1.5:Breakdown of rate of change of unit labour costs (ULC)

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|

|

Graph 1.6:Real Effective Exchange Rate based on unit labour costs

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|

External position

Despite continued current account surpluses, the net international investment position is only slightly positive. It is expected that the current account surplus will have declined from 3.6 % in 2017 to an estimated 3.2 % of GDP in 2018. The surplus largely reflects government and household savings as well as merchanting activities of multinational enterprises (). However, the net international investment position is only slightly positive, well below the sum of past current account surpluses. This is primarily due to persistent net portfolio investment in debt securities, especially of non-financial corporations, but may partly reflect valuation effects and measurement errors which suggest that the net international investment position could be underestimated (Graph 1.7) (European Commission, 2016a, pp. 13-14).

|

Graph 1.7:Net international investment position

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|

Public finances

The fiscal position has remained strong. At the end of 2017, revenue collection, surprised on the upside, underpinned by solid economic growth. As a result, the general government headline surplus was 1.6 % of GDP in 2017, well above the budget initially planned for 2017, implying a structural surplus of 1.4 % of GDP. As revenues are forecast to have reverted to more normal performance, a smaller surplus of around 1 % of GDP is expected for 2018. The headline surplus should decline to 0.8 % of GDP in 2020, as the economy slows.

Public debt is expected to continue declining. Strong economic growth, primary budget surpluses and prudent fiscal management have brought about a decline in the general government gross debt in recent years. This trend is set to continue with the debt-to-GDP ratio projected to fall to 33.5 % in 2020, significantly below the reference value of 60 % of GDP agreed in the Treaty (see also Section 4.1).

|

|

|

Table 1.1:Key economic and financial indicators – Sweden (1), (2), (3)

|

|

|

|

Source: Eurostat and ECB as of 31-1-2019, where available; European Commission for forecast figures (Winter forecast 2019 for real GDP and HICP, Autumn forecast 2018 otherwise)

|

|

|

2.

Progress with country-specific recommendations

Since the start of the European Semester in 2011, 84 % of all country-specific recommendations addressed to Sweden have recorded at least ‘some progress’.() 16 % of these CSRs recorded 'limited' or 'no progress' (Graph 2.1). Substantial progress and full implementation have been achieved in several policy areas, in particular fiscal governance and research and innovation. Limited progress has been achieved in implementing housing market and household debt related CSRs.

|

Graph 2.1:Overall multiannual implementation of

2011-2018 CSRs to date (1)

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|

Sweden has been able to preserve a sound fiscal position. This has ensured compliance with the medium-term budgetary objective and is keeping debt on a declining path well below the Treaty threshold.

For the labour market, the government achieved some progress in improving the employment situation of young people. In particular, it has adopted measures to strengthen apprenticeships and other types of work-based vocational education.

Since 2011, the country has received a recommendation each year related to its high and persistently rising household debt and house prices. The authorities have taken a number of policy steps to help rein in mortgage debt and house price growth and the associated risk to the broader economy and the financial system.

The focus has mainly been on macro-prudential measures and steps to tackle housing supply bottlenecks. Macro-prudential measures include a loan-to-value ceiling of 85 % for mortgages in 2010, raising banks’ risk weight floors for mortgages in 2013 and 2014, introducing a formal mortgage amortisation requirement in June 2016, followed by a strengthened amortisation rule for high-debt-to-income borrowers in March 2018 (see Section 4.2.3). Sweden also strengthened the legal mandate of the macro-prudential authority in February 2018. These steps have improved the resilience of the banking sector (see Section 4.2.1), but have not been able to rein in household debt growth (see Section 4.2.3). The authorities have also introduced measures to streamline building and planning regulations and have provided some budgetary support to municipalities to encourage more construction. While this has resulted in a significant pick-up in construction, the current level is still below anticipated demand, particularly in major cities (see Section 4.2.2).

Sweden has made limited () progress in addressing its 2018 country-specific recommendation (CSR). Some policy steps have been taken in response to the recommendation (which is relevant for the macroeconomic imbalance procedure (MIP), see Section 3). However, implementation has been uneven and key areas are left unaddressed. For the housing market, Sweden is moving forward with policy steps to promote more construction, including the gradual implementation of the ‘22-point plan’ for the housing sector, as well as measures to boost foreign competition in the construction sector (see Section 4.2.3). Additionally, in January 2019, the new government announced that reforms will be prepared to make the rent-setting system more flexible. There are also plans to make deferred capital gains taxes on sold properties in the owner-occupancy market interest-free. However, no progress has been made on reforming mortgage interest deductibility or recalibrating recurrent property taxes.

|

|

|

Table 2.1:Summary table on CSR assessment

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|

|

|

|

Box 2.1: EU funds and programmes contribute to addressing structural challenges and to fostering growth and competitiveness in Sweden

Sweden continues to benefit from the European Structural and Investment Funds (ESI Funds) and can receive up to EUR 3.6 billion until 2020. This represents around 2.7 % of public investment

I

over 2014-2018. By 31 December 2018, around 64 % had been allocated to projects. This has helped more than 40 000 companies strengthen their competitive edge. Examples of project areas are internationalisation, business development, incubation and new entrepreneurship.

ESI Funds help address structural policy challenges. Programmes supported by ESI Funds are helping to create strong innovation environments, clusters and accessibility of research resources for industry. Sweden uses the ESI Funds to implement smart specialisation strategies in all eight regions by involving over 5 600 enterprises that will cooperate with research institutes to develop marketable products. EUR 400 million supports the transition to a low-carbon economy. The European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) in Sweden has proven to be a very good example of how to use the funds for integration of third-country nationals. The focus has been on helping migrants start businesses or get jobs in the business sector. Dedicated calls for proposals are used for the implementation. Several projects have been approved and are progressing well. Individuals also receive support from the ESI Funds. EUR 808 million from the European Social Fund (ESF) are used to strengthen their employability through skills development and training. Following the recent influx of refugees and immigrants to Sweden, the ESI Funds have helped local authorities and other actors to provide more individually-adapted training and employability support. More than 110 000 persons have benefited from different ESF-funded projects.

The Commission can provide tailor-made technical support upon a Member State’s request via the Structural Reform Support Programme to help Member States implement growth-sustaining reforms to address challenges identified in the European Semester process or other national reforms. Sweden, for example, has started receiving support for the implementation of the corporate-income-tax gap assessment methodology.

EU funding contributes to mobilisation of private investment. Financial instruments are implemented through one National fund-in-fund (EUR 23.1 million to stimulate more private venture capital funds in early stages, have closer collaboration with the private sector and avoid regional limitations), eight regional venture capital funds (EUR 74 million) and a new National ‘green fund’ for early stage investments in companies promoting the transition to a low-carbon economy (EUR 38.7 million). In addition, Sweden is advancing the take-up of the European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI). The European Investment Bank with EFSI backing, approved operations with an overall volume of EUR 2.7 billion, which is set to trigger a total of EUR 10.5 billion in additional private and public investments. So far, 35 projects

II

have been approved under the infrastructure and innovation window of the EFSI (EUR 2.4 billion in total financing, supporting EUR 9.2 billion in investments). Under the SME component, 11 agreements with intermediary banks have been approved (EUR 330 million, mobilising around EUR 1.2 billion of total investment). 9 398 SMEs and mid-cap companies are expected to benefit from this support. One notable example is ‘Handiscover’, a Swedish start-up dedicated to helping people with physical disabilities find and book suitable travel and accommodation. Handiscover secured a loan from Almi Företagspartner and is backed by the European Investment Fund.

Funding under Horizon 2020, the Connecting Europe Facility and other directly-managed EU funds is additional to the ESI Funds. By the end of 2018, Sweden has signed agreements for 57 projects under the Connecting Europe Facility with Swedish beneficiaries receiving EUR 298.1 million in funding, and investing a total of EUR 709.7 million in these projects. Horizon 2020 contributed another EUR 1.26 billion.

https://cohesiondata.ec.europa.eu/countries/SE

|

3.

Overall findings regarding imbalances, risks and adjustment issues

The 2019 Alert Mechanism Report concluded that a new in-depth review should be undertaken for Sweden to assess the persistence or unwinding of the imbalances (European Commission, 2018b). In winter 2018, Sweden was identified as having macroeconomic imbalances (European Commission, 2018i). The imbalances identified related in particular to elevated house prices coupled with a continued rise in household debt. This chapter summarises the findings of the analyses in the context of the MIP in-depth review that is contained in various sections in this report. ()

3.1.Imbalances and their gravity

Private-sector debt stands at 194 % of GDP, among the highest in Europe. Both households (88 % of GDP as of Q3 2018) and non-financial corporations (111 % of GDP as of Q3 2018) have high debt levels compared to other EU countries and are also above debt benchmarks developed by the European Commission. Household debt is a particular source of concern. Driven primarily by mortgage lending, it has risen rapidly and persistently, outpacing GDP growth for over two decades now. Although households own significant assets, these are generally illiquid and their value is exposed to market risks. Moreover, the distribution of debt across households is uneven, and there is a significant fraction of borrowers with large debt-to-income ratios, particularly among younger households and those buying properties in major cities (see ‘Household debt developments’ in Section 4.2.3).

Corporate debt, while elevated, is matched by high equity cushions and corporate savings levels. Despite the significant stock of debt, financial risks remain limited overall thanks to healthy financial positions, in particular a low degree of balance sheet leverage and strong profitability. Moreover, external funding exposure, while growing, remains limited: domestic loans, which have proved resilient during the crisis, still constitute the main funding source for non-financial corporations (see ‘Corporate debt developments’ in Section 4.2.3).

Growing household debt coupled with elevated house prices makes the Swedish economy vulnerable to shocks. Swedish house prices have risen steadily for almost two decades, although in autumn 2017 the market experienced a gradual decline followed by stabilisation over the course of 2018. Strong fundamentals, in particular robust disposable income and population growth, can explain part of Sweden’s historical house price growth, but several indicators such as price-to-income (affordability) and price-to-rent (dividend) ratios suggest that house prices are above their historical trend. Distortive taxation and structural supply-side inefficiencies in the housing market contribute to this overvaluation (see Section 4.2.2).

The banking sector is solid, but it could be vulnerable in the event of a potential abrupt fall in real estate prices. Banks’ assets have performed well so far and the sector has high profitability compared to its peers in other EU countries. However, banks rely to a large extent on international wholesale funding, giving rise to some degree of maturity mismatch. Risk weights generated by their internal models are low and might not fully reflect the underlying risks in banks’ exposure to household mortgages. Banks also have significant exposure to the commercial real estate sector. Consequently, in a severe housing market or commercial property slump, these vulnerabilities could have repercussions for the wider economy and the financial system. Due to the importance of Swedish banks in the region, other Nordic economies might also be affected (see Section 4.2.1).

3.2.Evolution, prospects, and policy responses

While overall private debt has roughly stabilised relative to GDP, household debt remains on an upward trajectory. It grew at 5.5 % year-on-year in nominal terms as of December 2018. This represents a continued gradual deceleration from its peak growth rate of about 8 % around mid-2017, but remains well above economic and income growth. The increase in mortgage lending is driven by the lagged effect of house price rises in prior years, coupled with structural factors favouring (mortgage-financed) property investment, notably mortgage interest tax deductibility, variable rates and long maturities for mortgages. In light of the structural nature of some of these drivers, it appears likely that household debt will continue to outpace income growth over the medium term.

The authorities have gradually taken some policy action to curb household debt growth. After first introducing a formal mortgage amortisation requirement in 2016, in March 2018 Sweden implemented a stricter amortisation rule specifically targeting borrowing at high-debt-to-income levels. In addition, the Swedish Parliament (Riksdag) strengthened the legal mandate of the macro-prudential authority, the Financial Supervisory Authority (Finansinspektionen). The new mandate came into force in February 2018 and allows the authority to respond in a more timely manner, using a wider range of potential measures, to the risks associated with growing household debt. The Financial Supervisory Authority has also further raised the counter-cyclical capital buffer requirement for banks to 2.5 %; this will come in force in September 2019.

So far, however, these measures have had a limited impact on household debt growth, and key policy gaps remain. Sweden has one of the highest tax incentives for home ownership in the EU, due to relatively low property taxes and high mortgage interest rate deductibility, while the design of capital gains tax limits a more efficient use of the housing stock. These tax incentives contribute to the problem of persistent household debt growth.

Following a period of post-crisis deleveraging, corporate debt growth has again picked up. Non-financial corporate debt relative to GDP fell by about 25 percentage points between 2009 and 2016. This has mostly been the result of ‘passive’ deleveraging, with positive net credit flows to firms being outweighed by growth and inflation. However, since early 2017, net corporate debt has again started outpacing economic growth, due to highly favourable credit conditions and overall still robust confidence levels among companies. Domestic bank loans remain the main funding source of firms, followed by international bond markets (see ‘Corporate debt developments’ in Section 4.2.3). While this allows for funding alternatives, a higher share of bond market financing could in some cases expose firms more to volatility and stress in the financial markets.

Swedish banking groups have a substantial and growing exposure to household mortgages, while being supported by sufficient capital buffers. The near-term risks of household debt service problems seem limited, given low debt service costs and sizeable household budget margins. However, stretched housing market valuations combined with high debt levels make the household sector vulnerable to shocks. If, for instance, mortgage interest rates were to rise significantly, or if incomes were hit due to an external shock to the economy, households could be forced to rapidly reduce consumption levels. Moreover, as Swedish banks are reliant on wholesale funding, a downturn in the housing market could result in a sudden rise in bank funding costs, thus amplifying the impact of any domestic housing market adjustment. Supervisors are mindful of such risks.

Following a long period of virtually uninterrupted strong growth, house prices fell in autumn 2017 and stabilised well below their peak. Real house prices have more than tripled over the past two decades, significantly outpacing income growth. Unlike most European countries, Sweden had no major adjustment in house prices around the 2008-2009 financial crisis. While the 2017 price declines were significant in absolute terms, real house prices have only moved back to roughly their end-2016 level. Valuation indicators continue to suggest that house prices remain high relative to fundamentals. Thus, the recent episode of market weakness should not detract from the broader concerns that Sweden’s elevated house prices contribute to macroeconomic stability risks.

Policy action focused on curbing housing demand via macro-prudential measures, combined with steps to stimulate new construction. Since 2010, Sweden has gradually introduced a number of macroprudential measures (see above), aimed at containing mortgage growth and thus housing demand. The authorities have also proceeded with the gradual implementation of the ‘22-point plan’ for the housing market and similar measures to stimulate more construction.

Some key structural distortions in the housing market have not yet been addressed. In particular, no policy action has been taken to reform the tax incentives for home ownership and mortgage debt (see above). Similarly, so far there have been no concrete policy steps to liberalise tight rental market regulations and revise the capital tax on owner-occupied homes, although in January 2019 the new government announced plans to introduce reforms in these areas, subject to preparatory inquiry work (see ‘Policy developments’ in Section 4.2.2). In addition, there remains scope to further tackle the lack of land available for development, complex planning and building regulations, limited incentives for municipalities to support new construction and limited competition in the construction sector (see ‘Supply-side issues’ in Section 4.2.2).

3.3.Overall assessment

Sweden faces sources of imbalances in the form of high private debt and overvalued house prices. The elevated private indebtedness, in particular of households, makes the economy vulnerable to macroeconomic shocks (see ‘Risks and policy response’ in Section 4.2.3). Such a shock could trigger deleveraging, potentially leading to harmful adjustment, with lower consumption and investment. Although house prices have stabilised well below their 2017 peak, they continue to appear overvalued. In the event of a large, disorderly downturn in the housing market, there is a risk of negative spillover effects acting on other Nordic countries through the financial system.

Policy measures to address these imbalances have so far been insufficient. The authorities have gradually taken some policy action to curb household debt growth in recent years, but this appears to have had limited impact on indebtedness growth. In addition, some key structural issues in the housing market have not been addressed. Overall, policy gaps remain for housing-related taxation, the functioning of housing supply and of the rental market.

|

|

|

Table 3.1:MIP assessment matrix (*) — Sweden 2019

|

|

|

|

|

|

(Continued on the next page)

|

|

Table (continued)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|

|

|

4.

Reform priorities

4.1.Public finances and taxation

Public finances remain strong. Sweden is set to have achieved a general government surplus of 1.6 % of GDP and a structural surplus of 1.4 % of GDP in 2017. The debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to decline below the new 35 % debt anchor by 2020. With prudent fiscal policy in place, Sweden faces low fiscal sustainability risks in the medium to long term.

4.1.1.

Fiscal framework

In 2019, revised rules came into force in Sweden to further strengthen its fiscal framework. The main improvements include the introduction of a new debt anchor and the strengthened mandate of the independent Fiscal Policy Council (Finanspolitiska rådet) to monitor fiscal rules and evaluate the official macro-forecasts (European Commission, 2018a).

Sweden adopted a fiscal framework already in 1997. In response to the economic crisis in the early 1990s, Sweden introduced a comprehensive fiscal framework, with broad political support, which substantially contributed to its effectiveness. The core elements included the introduction of numerical rules: (i) three-year expenditure ceilings binding for the next two years, (ii) a general government surplus target and (iii) a balanced-budget rule at the local level. In 2007 an independent Fiscal Policy Council was set-up to assess whether the government had achieved its fiscal and economic policy objectives, in particular long-term fiscal sustainability and consistency with the surplus target, the expenditure ceiling and the economy’s cyclical position.

The Swedish fiscal framework has performed well. Using the Fiscal Rules and the Medium-term Budgetary Framework (MTBF) indices (European Commission, 2018d), which focus exclusively on design elements, Sweden was well-above the EU-average for most of the last 15 years (Graph 4.1.1)(). More recently, however, national fiscal frameworks in the EU – and euro area in particular – have greatly improved due to EU legislative initiatives. While this pushed up the EU average, the number and quality of fiscal rules in Sweden were broadly unchanged and therefore the country appears to have lost ground relative to its peers. This will likely change as of 2019 when the recent reforms partly addressing some of the new EU requirements will take effect. By contrast, the Swedish medium-term framework remains strong as the expenditure ceilings are binding for the first two years of the policy horizon and not revised yearly as it is the case in most Member States.

|

Graph 4.1.1:Swedish fiscal rules and MTBF and EU average

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission's Fiscal Governance Database.

|

Overall, the fiscal framework has been successful in maintaining budgetary discipline and long-term fiscal sustainability in Sweden. Based on the European Commission estimates for the budgetary impact of fiscal rules and MTBFs (European Commission, 2018e), the Swedish fiscal framework is deemed to have contributed by about five percentage points of potential GDP in the short-term and 10 percentage points in the long-term (Graph 4.1.2) to fiscal consolidation of the primary budget surplus in cyclically-adjusted terms(). Government debt started to decline following the introduction of the fiscal framework (Graph 4.1.3). From its peak in 1996, government debt had declined by about 25 percentage points of potential GDP by 2016, and the above estimates suggest that up to half of this decline can be attributed to the fiscal framework.

|

Graph 4.1.2:Impact of fiscal rules and MTBF on the cyclically-adjusted primary budget balance

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission calculations based on European Commission (2018e).

|

|

Graph 4.1.3:Swedish fiscal rules index and government gross debt

|

|

|

|

Sources: European Commission's Fiscal Governance Database and Ameco

|

4.1.2.

Taxation developments

The general level of taxation remains above the EU average. The total tax burden is 44.4 % of GDP compared with the EU average 39.0 % of GDP. The overall labour tax burden is also high with the implicit tax rate at 40.4 % in 2017 above the EU average of 36.3 %. Low income earners at 50 % of the average wage face a particular high tax wedge, i.e. gap between labour costs and take-home pay.

The Riksdag rejected the 2019 caretaker government budget bill in favour of a slightly more expansionary proposal submitted by the opposition. The Swedish authorities estimate that the adopted 2019 budget implies a weakening of public finances by about SEK 29 billion in relation to 2018. Higher expenditure is included for defence, the police and the judiciary, while labour market policies and environmental policy are subject to some reductions. Income taxes will be cut in 2019: the basic income tax deduction for persons older than 65 is raised, and the earned income tax deduction is expanded in combination with an increase in the tax threshold for state income tax. As from 2020, the new government intends to abolish the five percent top income tax (värnskatt). Looking further ahead, it aims for a broad tax reform increasing Sweden's competitiveness and labour market participation rate through lowered income and corporate taxes.

Addressing tax incentives could help mitigate the build-up of household indebtedness. At present there are no concrete plans to revise rules regarding the mortgage interest deductibility or the recurrent property tax. Reforms in this area could contribute to a more favourable development of household debt (see Section 4.2) and would also have a favourable impact on income equality, particularly if the proceeds are used to reduce taxes on labour ().

4.1.3.

Debt sustainability analysis and fiscal risks

Sweden’s government debt is expected to continue declining over the medium term. Sound fiscal management and strong economic performance under the Commission’s baseline no-policy change scenario is projected to bring government debt close to 16 % of GDP in 2029 from 37.8 % of GDP in 2018, well below the 60 % of GDP Treaty reference value. The outlook for fiscal sustainability appears sound in the short, medium and long term (European Commission (2019a and Annex B).

Debt dynamics appear to be resilient to shocks. In all sensitivity test scenarios government debt remains on a downward trend. Debt-to-GDP at the end of the projections period (2029) in these scenarios is moderately higher than the baseline. In the worst case scenario, based on a shock to the exchange rate, gross public debt would reach 19 % of GDP in 2029.

Public expenditure on long-term care is projected to increase. Demographic changes imply that under current policies, spending on long-term care can be expected to increase significantly, from 3.2 % of GDP in 2016 (among the highest in the EU) to 4.9 % of GDP in 2070 (European Commission, 2018b). This corresponds to a 53 % increase, similar to the EU average. The share of the population that receives long-term care benefits is relatively high by EU standards, whereas the underlying level of need () is broadly in line with the EU average.

4.2.

Financial sector and housing market

4.2.1.Banking sector (*) ()

Overview

The Swedish banking sector is large and maintains strong profitability. The system’s total assets, including foreign banks activities, represent around 300 % of GDP. Bank profitability still ranks among the highest in Europe with returns on equity averaging 9 %, helped by low funding costs and high cost efficiency. Favourable economic conditions translate into sustained lending to non-financial corporations and supported income from transaction fees.

Banks remain healthy with high-quality assets. In 2018 the average non-performing loan ratio remained one of the lowest in the EU. Customers’ high repayment capacity and a strong reimbursement culture are among the main reasons for limited defaults and provide a potential shock-absorbing buffer to Swedish banks in the case of an economic slowdown.

Banks have a high exposure to the real estate sector. Almost 90 % of household lending consists of mortgages while commercial property, including tenant-owner associations, represents 55 % of lending to corporations. Developments on the real estate market therefore have a major impact on the financial position of banks (Finansinspektionen, 2018c).

Swedish banks rely to a large extent on wholesale funding. About 50 % of their loan book is funded by domestic deposits. The main additional funding source is the wholesale funding market, often accessed with covered bond issuances backed by residential mortgages.

New players have recently entered the Swedish mortgage markets. These are either loan brokers that connect borrowers with lenders, or non-bank lenders that grant mortgages to create and manage investment products on behalf of institutional investors. Although the volumes they are managing are small, they are competing with banks for mortgage customers and their importance could increase. This could be positive for financial stability if they use more stable funding sources than banks. However, the new business models remain untested in terms of sudden changes in economic conditions and could complicate macro-prudential policy (Sveriges Riksbank, 2018a).

The structure of the Swedish banking sector changed as Nordea relocated to Finland. In October 2018 the Nordea group moved its headquarter to Helsinki. Although the move has left Nordea’s business operations in Sweden largely unaffected, it had important implications for supervisory responsibilities (see ‘Key risks and policy responses’ below).

The calculation of banks’ risk-weighted assets, and with it Swedish banks’ capital ratios, has changed. The Financial Supervisory Authority (Finansinspektionen) revised the modalities for imposing a risk-weight-floor on residential mortgages for banks using internal risk models to be applied as of end 2018(). With this revision, the Authority intends to maintain a level playing field among banks in the domestic market for residential mortgages. Due largely to this change, the average Tier 1 ratio under the new rules will be substantially lower than the latest available official figure (22.6 % in Q2 2018, see Table 4.2.1). The revision brings the calculation of banks’ capital ratios closer to prevailing practices in most EU Member States. However, even following these changes, the capital ratios of Swedish banks would remain relatively high compared to the EU average of 16.2 % ().

|

|

|

Table 4.2.1:Financial soundness indicators, all banks in Sweden

|

|

|

Source: European Central Bank

|

|

|

The major Swedish banks showed resilience in the 2018 stress test conducted by the European Banking Authority (EBA). Banks would have the ability to withstand a severe recession combined with falling real estate prices used in the exercise. Such a scenario had a limited impact on bank capital as the Common Equity Tier 1 would be reduced between 2.7 and 3.3 percentage points (European Banking Authority, 2018).

Key risks and policy responses

Banks’ high exposure to the housing market is a key risk. Households remain vulnerable to an adjustment in the housing market and an increase in interest rates. Since about 70 % of household mortgages have been taken at variable interest rates, an increase would result in higher payments, lower consumption and potentially substantial repercussions for the overall economy and the financial system (see Section 4.2.3). This was also highlighted by the Riksbank (Sveriges Riksbank, 2018a) and the Financial Supervisory Authority (Finansinspektionen, 2018c).

A rise in interest rates could also result in higher funding costs and liquidity risks. Swedish banks rely on wholesale funding often held by international financial institutions. This reliance makes the system vulnerable because international wholesale funding is much more responsive to changes in interest rates compared to domestic deposits. Moreover, it can also quickly dry up should conditions of financial stress occur, creating a liquidity risk for Swedish banks (Finansinspektionen, 2018c).

Risks related to a strong commercial real estate market have become more prominent. Banks’ lending to the commercial real estate sector has increased sharply the past years, and a large proportion of their lending has commercial property as collateral. So far commercial real estate companies have benefited from rising real estate prices and rental income. A change in this trend – due to a cooling economy for example – could affect incomes, credit quality and (in an extreme scenario) even financial stability in the event of a sudden market correction (given the size of the commercial property market in Sweden and its historic sensitivity to macro-financial shocks) (Finansinspektionen, 2018c).

Nordea’s move has reduced the Swedish authorities’ control and oversight of the bank. While Nordea’s business operations in Sweden remain basically unchanged, the responsibility for the supervision and resolution has moved to the European Central Bank and Finnish supervisors (). Against this backdrop, in 2017 the Swedish government launched a comprehensive analysis of the implications of joining the Banking Union, whose results are expected in November 2019.

The current differences in banking rules/regulations across the Nordic-Baltic region have resulted in increased cooperation. Recent developments, such as those related to the risk weight floor for residential mortgages and the fact that large financial institutions often operate in other countries via branches, have made it apparent that there is a need of coordination between macro-prudential authorities. Supervisors from the various countries are aware of potential spillover risks in the event of acute financial systemic stress and that the existing differences in legal frameworks must be taken into account (). They are therefore already cooperating closely to enable an effective response when needed.

The Financial Supervisory Authority adopted additional macro-prudential measures to mitigate risks posed by increasing household indebtedness. A stricter amortisation requirement for new mortgage borrowers with high debt-to-income (DTI) levels came into force in March 2018. Under this requirement, households obtaining a mortgage with an overall debt level over 450 % of gross income (roughly equivalent to 630 % of after-tax disposable income) must amortise the mortgage principal by one percentage point per year. This applies on top of the already existing amortisation rule introduced in 2016. This brings the overall amortisation rate to a maximum of 3 % per year for households with very high DTI levels and loan-to-value rates higher than 70 %. From 2019 macro-prudential measures specifically applying to mortgages will apply also to new non-bank mortgage brokers. As of 19 September 2019, the countercyclical capital buffer for banks will also be raised from 2 to 2.5 % against the background of continued high credit growth and elevated systemic risk (Finansinspektionen, 2018d).

4.2.2.Housing market (*)

Housing market developments

Following a sharp adjustment in late 2017, house prices have broadly stabilised. After two decades of largely uninterrupted price growth, the housing market slowed notably in 2017, culminating in a nominal price fall in the autumn of close to 10 % on average. This decline was probably triggered by a sharp rise in new-built supply in specific market segments, notably high-end apartments in Stockholm (Sveriges Riksbank, 2018a; European Commission, 2018a). Since 2018, prices have broadly held steady (Graph 4.2.1). As of December 2018, they stood at about 7 % below their 2017 highs. Transaction volumes have overall remained weak compared to 2016 and early 2017, and have fallen somewhat over the course of 2018. The recent stabilisation and structural factors supporting house prices (see below) point to broadly steady prices in the near-term. However, the continued supply overhang in higher-priced Stockholm apartments represents a significant downside risk.

|

Graph 4.2.1:House prices by market segment (nominal)

|

|

|

|

Source: Valueguard HOX house price index

|

While house prices remain below their peak, valuation indicators still suggest that they are overvalued. Fundamental drivers, in particular strong population and income growth and increasing urbanisation, supported house price growth in previous years (European Commission, 2016a), but cannot fully explain the current high levels. Fundamental-model-based estimates suggest that the housing market is overvalued by around 12 % () as of end-2017 (Graph 4.2.2). Other valuation indicators like price-to-income and price-to-rent ratios (measures of affordability and return-on-investment of owner-occupied houses) point to a sizeable valuation gap of about 45 % and 65 % respectively above their long-term averages. These estimated valuation gaps are among the highest in the EU. While such indicators are inevitably subject to some modelling uncertainty, they do underscore that the Swedish housing market is vulnerable.

|

Graph 4.2.2:Estimated house price valuation gaps based on different indicators (1)

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission calculations

|

The recent housing market weakness has only made a modest dent in a long-standing upwards house price trend. After bottoming out following the banking crisis in the early 1990s, house prices have grown steeply and persistently. In real terms, they have more than tripled, significantly outpacing income growth as well as house price rises in other EU countries (European Commission, 2018a). While the 2017 price declines were significant in absolute terms, real house prices have only moved back to roughly their end-2016 level. Thus, the recent market weakness should not detract from the broader concerns that Sweden’s elevated high house prices contribute to macroeconomic stability risks (see Sections 3, 4.2.1 and 4.2.3) and also have implications for social equality (see ‘Inequality’ in Section 1).

Demand-side issues

Not only low mortgage rates, but several structural features of the Swedish mortgage market have boosted housing demand. Monetary policy in Sweden has been highly accommodative. Although the Riksbank has raised the benchmark interest rate in December 2018, it remains negative, as it has been for over 3 years now (see Section 1). While low interest rates naturally act as a tailwind for the property market, in Sweden this effect has been magnified by a high share of variable-rate mortgages, long contract maturities and still generally low amortisation rates (see Section 4.2.3 for details). As a result, debt service costs relative to incomes have remained low, even as house prices and debt levels have continued to climb.

The Swedish tax system favours owner-occupied housing over other investments, particularly when financed by mortgage debt. Under the dual income tax system, returns from financial investments are normally taxed at a flat capital income rate of 30 %. However, imputed rents (the effective return to homeowners on their housing investment) are not taxed. Instead, property owners pay a local property fee (kommunal fastighetsavgift). This fee is capped at a low ceiling(), resulting in a highly favourable tax treatment of owner-occupied housing compared to other investments, and low overall tax revenues from property by international standards (Graph 4.2.3). Additionally, interest paid on mortgages is generally deductible at the 30 % capital income rate (), providing an effective subsidy for mortgage debt. This further favours (debt-financed) home ownership, both over other investment opportunities and over rental housing, for which the overall tax burden is considerably higher (Statens Offentliga Utredningar (SOU), 2014).

|

Graph 4.2.3:Revenues from property taxes

|

|

|

|

Source: OECD

|

Reforming the tax incentives for home ownership and mortgage debt could contribute to reducing inequality and benefit job creation. The impact of such tax reforms would be broadly progressive, as households benefiting the most from low recurrent property taxes and generous mortgage interest deductibility tend to be the higher-income ones (Finanspolitiska rådet, 2016). Moreover, the fiscal room created by such reforms could be used to ease the labour tax burden in an appropriately targeted way, thus facilitating job creation and further supporting social equality (European Commission, 2018a).

Supply-side issues

One of the key drivers of Sweden’s elevated house price level is a structural undersupply of dwellings. Following the early-1990s banking crisis, residential construction activity in Sweden was muted for a prolonged period, in spite of strong population growth and rapid house price rises (European Commission, 2018a). More recently, new housing construction has accelerated notably and annual housing starts more than tripled from their 2012 low to a recent peak of about 64 000 in 2017 (Graph 4.2.4). However, even after this strong upswing, new housing supply failed to reach projected near-term needs, estimated at about 90 000 new homes per year for 2018-2020. Additionally, some of the new construction appears to attract limited demand (Katinic, G., 2018), and may thus have little immediate effect on the broader housing shortage.

|

Graph 4.2.4:Housing starts, including net conversions, versus projected need

|

|

|

|

Source: Statistics Sweden (historical data until 2017); Boverket (estimates for 2018 and 2019, and projected need)

|

New housing construction slowed significantly in 2018, and appears set for further near-term falls. The late-2017 house price declines combined with an ongoing overhang of unsold new-built Stockholm apartments have had a notable impact on sentiment in the construction sector and expectations for future building activity (Graph 4.2.5). New housing starts fell significantly in 2018 — by an estimated 20 % across Sweden as a whole, and about 35 % in Stockholm — with further declines projected in 2019 (Graph 4.2.4). As a result, the recent housing market weakness may exacerbate the long-standing supply shortage even further. This underscores the importance of tackling remaining barriers to new housing construction.

|

Graph 4.2.5:Construction sentiment: overall confidence indicator and expectations component (1)

|

|

|

|

Source: National Institute of Economic Research (Konjunkturinstitutet); European Commission

|

Structural bottlenecks are constraining housing supply and raising construction costs. There is a lack of developable land, partly driven by the fact that a large share of buildable land is owned by municipalities, which can have financial incentives for making it available in a piecemeal fashion over time rather than when it is needed most (European Commission, 2015)(). Despite some recent reforms, zoning and building regulations overall remain relatively cumbersome and complex. In particular, the interpretation of building rules continues to vary between some municipalities (), creating a fragmented market that reduces efficiency and increases uncertainty for construction companies (European Commission, 2016). Additionally, the total time required to complete land acquisition and planning processes can be considerably longer than in other countries (Emanuelsson, 2015). This raises financial risks for construction projects and causes delays in new supply. Rigidities in the construction sector have weighed on productivity growth and restricted competition (), raising construction costs in Sweden to among the highest in the EU (European Commission, 2018a).

Increasing residential construction costs appear to be partially driven by building materials. Costs for new residential buildings in Sweden grew strongly in recent years, from an already high level (European Commission, 2018a). This further rise was mainly driven by building materials costs, for which Sweden has the highest increase in the EU since 2015 (Graph 4.2.6). Other factors contributing to high building costs are wide profit margins among developers (Konkurrensverket, 2018) and weak productivity growth in the construction sector (European Commission, 2018a).

|

Graph 4.2.6:Labour and material cost evolution in new residential construction (total % rise between 2015-2018Q2; not annualised)

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|

Barriers to efficient usage of the housing stock

Sweden’s tightly regulated rental market can create lock-in and ‘insider-outsider’ effects. Sweden’s rental market has some of the strongest tenant protection rules in the EU (European Commission, 2017a). Rents are mostly set in collective-bargaining-style negotiations (), which tend to result in below-market rent levels in urban areas (European Commission, 2018a). This creates large demand/supply imbalances and long waiting lists to obtain rental accommodation (Graph 4.2.7). As a result, sitting tenants can have a strong financial incentive not to move, even if their accommodation is no longer fully suited to their needs () (Katinic, 2018). Conversely, new entrants, such as students, young households and recent immigrants, face difficulties in getting a foothold on the rental market, thus creating an insider/outsider effect. Indirectly, the latter also contributes to high house prices in the owner-occupier market, as no access to rental housing can push households to purchase their own home (Geng, 2018).

|

Graph 4.2.7:Time on waiting list before obtaining primary tenancy in greater Stockholm

(distribution by number of years)

|

|

|

|

Source: Stockholm Housing Agency (Bostadsförmedlingen)

|

The gap between negotiated rents and market rents has impaired rental housing supply, particularly in major cities. Below-market rent levels combined with high land prices create financial incentives to favour construction of owner-occupancy housing over rental apartments (). This situation also encourages conversion of rental units into owner-occupied homes, thus further aggravating the rental housing shortage. Historically, this has been particularly pronounced in major urban areas: for example, in Stockholm, for every new rental apartment built, three were converted into owner-occupied units over the 1990s and 2000s (Emanuelsson, 2015).

In addition, there are negative knock-on effects on labour mobility and social equality. The lock-in and insider/outsider effects in the rental market can prevent workers from moving to locations with the best job opportunities, thus hampering labour market dynamism. Furthermore, tight rental regulations combined with a shortage of affordable rental housing can exacerbate inequality and social problems. This particularly affects lower-income households, and can contribute to a relatively high degree of overcrowding among socially vulnerable groups (OECD, 2017b). While reform of Sweden’s rental market may also have significant redistributive and social consequences, this could be managed by a combination of tax measures and targeted subsidies (Donner et al., 2017).

The role of ‘social contracts’ in public housing policy is gradually growing. The need for affordable rental housing is linked to broader questions concerning optimal use of the available housing stock. Sweden does not have a designated social housing sector. Public housing companies () own around 20 % of the housing stock. Additionally, municipalities can offer ‘social contracts’ () to assist the most vulnerable groups in society. Although numbers are still low (roughly 30 500), such social contracts are gaining in importance, especially in urban areas.

Capital gains taxes on housing transactions can create lock-in effects in the owner-occupier market. Sweden applies a 22 % capital gains tax on property sales, even when a homeowner is selling to buy another property of similar value elsewhere (meaning no actual economic gain is realised). As house prices have increased significantly in Sweden, this means that households which have owned their home for a long time can face prohibitively high moving costs (). In practice, this tends to particularly affect elderly households living in large single-family houses and looking to relocate to a conveniently-located apartment. Reforming capital gains taxation to eliminate this lock-in effect could help free up underused family dwellings from the existing housing stock and improve overall supply-demand matching in the owner-occupier market.

Policy developments

Demand-side policy action in the housing market has been focused on using macro-prudential measures to curb mortgage lending. Since 2010, Sweden has gradually introduced a number of measures, including loan-to-value limits, adjusting banks’ risk-weight floors, and introducing a binding mortgage amortisation requirement in June 2016 (see Section 4.2.3 for details) to contain mortgage debt growth (and thus housing demand). A more stringent amortisation rule for borrowers with high debt-to-income ratios came in force in March 2018 (also discussed in Section 4.2.3).

The implementation of the ‘22-point plan’ for the housing market continues. The plan, originally proposed in June 2016, contains a range of measures — mostly rather incremental in nature — which aim to increase the land available for development, reduce construction costs, shorten planning process lead times and address some specific inefficiencies in the rental market. Some parts of the plan, particularly those which concern reducing costs and lead times for new construction, have been broadly completed. For other elements, including a review of building and planning regulations and measures to make more developable land available, public inquiries and other preparatory steps are still ongoing. More time is required before these proposals can be finalised, therefore, and it remains uncertain whether they will result in actionable conclusions and ultimately successful implementation.

Sweden is taking steps to boost participation of foreign companies in the construction industry. In June 2018, the National Board of Housing, Building and Planning (Boverket) finalised the first phase of an effort to facilitate entry of foreign construction firms in the Swedish market in order to promote competition and lower residential construction costs. It set up an online portal () with detailed English-language guidance for foreign developers, including translations of building regulations and practical information on the Swedish construction sector. The web portal will gradually be expanded further, and Boverket will also investigate additional obstacles encountered by foreign operators and which could be addressed by targeted policy measures.