EUROPEAN COMMISSION

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Brussels, 7.12.2015

SWD(2015) 262 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

IMPACT ASSESSMENT

Accompanying the document

proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL

on common rules in the field of civil aviation and establishing a European Union Aviation Safety Agency, and repealing Regulation (EC) No 216/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council

{COM(2015) 613 final}

{SWD(2015) 263 final}

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1Introduction

1.1Political context

1.2Legal context

1.3Evolution of aviation safety in the EU/EFTA states in the last decade

2Problem definition

2.1Description of the main problems

2.1.1The present regulatory system may not be sufficiently able to identify and mitigate safety risks in the medium to long term

2.1.2The present regulatory system is not proportionate and creates excessive burdens especially for smaller operators

2.1.3The present regulatory system is not sufficiently responsive to market developments

2.1.4There are differences in organisational capabilities between Member States

2.2Underlying problem drivers

2.2.1Level and type of regulation does not sufficiently correspond to the risks associated with different aviation activities

2.2.2System is reactive and predominantly based on prescriptive regulations and compliance checking

2.2.3Inconsistencies and gaps in the regulatory system

2.2.4Shortages of resources impacting safety oversight and certification

2.2.5Inefficient use of resources stemming from fragmentation

2.3Baseline scenario

2.3.1Evolution of the problems

2.3.2Expected future resource needs

2.4Subsidiarity

2.4.1Legal basis

2.4.2Necessity and EU added value

3Objectives

4Policy options

4.1General approach to policy options

4.2Discarded Policy Options

4.2.1‘No EU action’

4.2.2Using international standards only

4.2.3.‘Soft law’ measures

4.3Description of Policy Options

4.3.1Options with respect to the management and quality of resources

4.3.2Options with respect to proportionality and safety performance

4.3.3Options with respect to the safety gaps and inconsistencies

5Analysis of impacts

5.1Quality and management of resources

5.2.Proportionality and safety performance

1.1.

5.3Gaps and inconsistencies - safety aspects of ground handling

5.4Gaps and inconsistencies - aviation security

5.5Gaps and inconsistencies - environmental protection

6Comparing the policy options

6.1.Quality and management of resources

6.2Proportionality and safety performance

6.3.Gaps and inconsistencies - ground-handling

6.4.Gaps and inconsistencies - aviation security

6.5.Gaps and inconsistencies – environmental protection

6.6.Preferred policy package

7.Monitoring and evaluation

8Implementation of the preferred policy package

8.1Operational objectives

8.2Timeframe for implementation

8.3Implementation risks

8.4Interdependencies between measures in different policy domains

ANNEX I

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

ANNEX II

Summary of Commission Public Consultations

ANNEX III

ANNEX IV

Article 62 evaluation (2013)

Summary of recommendations

ANNEX V

EASA Management Board Sub-Group

on the Future of the European Aviation Regulatory System

Summary of recommendations

ANNEX VI

Division of responsibilities in the EU aviation safety system

ANNEX VII

The main functions of the EU aviation safety system

ANNEX VIII

Filing of differences with ICAO SARPs by EU Member States

on the basis of EASA recommendations

ANNEX IX

Key figures for the quantification of economic impacts

ANNEX X

ANNEX XI

Methodology for calculating future resources needs of the National Aviation Authorities under the Baseline Scenario ('future resources gap')

ANNEX XII

Contribution of policy options related to 'quality and management of resources' to the reduction of future resources needs in Member States – detailed calculations

ANNEX XIII

Correlation between effectiveness of state safety oversight and accident rates

ANNEX XIV

Projected aviation safety workforce trends in US

ANNEX XV

Examples of performance based regulations

ANNEX XVI

Risk Hierarchy Concept

ANNEX XVII

Safety Management Systems, Safety Performance Schemes and Performance Based Rules

ANNEX XVIII

Workshop on performance schemes and performance based approach in the context of aviation safety

ANNEX XIX

Executive seminar on European aviation safety

ANNEX XX

GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT THE EU GROUND-HANDLING MARKET AND SAFETY OF GROUND HANDLING SERVICES

ANNEX XXI

Annex XXII

Annex XXIII

Glossary of main technical terms

Annex XXIV

1Introduction

1.1Political context

This initiative is part of the 2015 European Commission’s 'Aviation Package for improving the competitiveness of the EU aviation sector'. The objective of this review is to prepare the EU aviation safety framework for the challenges of the next 10-15 years and thus to continue to ensure safe, secure and environmentally friendly air transport for passengers. This initiative builds on over twelve years of experience in the implementation of Regulation (EC) No 216/2008 and its predecessor.

The 2011 White Paper on transport aims at Europe becoming the safest region for aviation. Air transport in the EU has at present an excellent safety record. With the average annual accident rate in commercial air transport in the last ten years standing at 1.8 per ten million flights, the EU is one of the safest regions in the world for air travellers. However, with the aviation traffic in Europe predicted to reach 14.4 million flights in 2035 (50% more than in 2012), we must make sure, by focusing on clearly identified risks, that the system continues to maintain the current low number of accidents. This means that the accident rate has to continue decreasing in proportion to traffic growth.

While aviation safety is an important objective of this initiative, it is not the only one. This proposal must also be seen in the context of the Europe 2020 Strategy, in particular regarding employment and innovation, and of the Commission priorities of fostering jobs and growth, developing the internal market and strengthening Europe's role as a global actor. Aviation is one of the strategic EU industries with a positive growth projection for the next decades and generates numerous, highly skilled jobs. Including indirect and induced impacts, the air transport sector supports 5.5 million jobs and contributes nearly EUR 395 billion to GDP in the EU28. This initiative thus also aims at contributing to a competitive European aviation industry based on a well-functioning internal market, which creates high value-jobs and drives technological innovation.

Safety is a pre-requisite for a competitive aviation sector. Staying competitive without making concession on safety however, requires the EU to become more efficient. While the present system has been so far effective in ensuring safety of air passengers, it is not the most efficient one, and creates unnecessary costs for Member States, industry and airspace users. There is a strong call from the industry and Member States for a more flexible system which would allow using the limited resources more efficiently, eliminate ineffective regulation, facilitate innovation and boost the competitiveness of the European industry. Especially the small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) urge the EU to introduce a more proportionate regulatory framework and to eliminate regulation which stifles entrepreneurship and introduction of new technologies with too prescriptive requirements.

Finally the present unfavourable economic situation puts an increasing pressure on EU and Member States’ budgets. Many National Aviation Authorities are finding it difficult to maintain, not to mention increase, their resources, while the demand from industry for technically challenging certification and oversight work does not diminish.

1.2Legal context

The responsibilities for the implementation of the EU aviation safety system are shared between the national and EU levels. In addition, in the area of air traffic management, the EU still makes some use of the European Organisation for the Safety of Air Navigation (EUROCONTROL) which is a separate intergovernmental organisation. The International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) influences the functioning of the EU system by setting minimum standards at the global level and overseeing their implementation by Member States and the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). Finally a number of specialised bodies, such as SESAR Joint Undertaking, Network Manager and Performance Review Body, contribute to the functioning of the EU aviation safety system.

The EU legal framework for civil aviation safety is primarily based on Regulation (EC) No 216/2008, which constitutes a recast of Regulation (EC) No 1592/2002. This Regulation establishes the main functions of the system, such as rulemaking, certification and oversight, and creates EASA as a specialised EU aviation safety body. Originally the scope of the Regulation was limited to airworthiness and certification of environmental protection with respect to aeronautical products. This initial scope was subsequently extended to flight operations and aircrew (2008), and safety aspects of air traffic management, air navigation services and aerodromes (2009). Whilst Regulation (EC) No 216/2008 defines the scope of the system and sets out the responsibilities for its implementation, the detailed obligations of the regulated entities, such as airlines or manufacturers, are laid down in Implementing Rules adopted by the European Commission on the basis of technical proposals of EASA.

In addition to Regulation (EC) No 216/2008 and its Implementing Rules, the legal framework of the EU civil aviation safety system is composed of a number of additional regulations, most notably on: accident investigation, occurrence reporting and analysis, and banning of unsafe operators. Finally safety aspects of air traffic management and air navigation services are still to a certain extent regulated in parallel by Regulation (EC) No 216/2008 and the Single European Sky (SES) regulations. With respect to this last point, the European Commission has launched the SES II+ initiative which aims to remediate the overlap, and on which the present proposal builds.

Regulation (EC) No 1008/2008 on common rules for the operation of air services in the Union also contains a number of safety related provisions (concerning leasing and Air Operators Certificates) which are impacted by the present initiative.

Finally, the governance, functioning and oversight framework for EU agencies has been subject to a comprehensive review in 2012, which resulted in a 'Common Approach on decentralised agencies' between the Commission, European Parliament and the Council, which needs to be taken into account by the present initiative.

Annexes VI and VII contain additional information about the functioning of the EU aviation safety system and responsibilities of the different actors involved in its implementation. Annex XXIII contains a glossary of the main technical terms used in this report.

1.3Evolution of aviation safety in the EU/EFTA states in the last decade

When it comes to scheduled commercial air transport operations, the EU/EFTA enjoys today one of the best safety records in the world (Table 1), with the average fatal accident rate in the last ten years standing at 1.8 per ten million flights, which is significantly below the worldwide average (Figure 1).

Table 1: Scheduled Commercial Air Transport Fatal Accident Rate per 10 million flights, 2004-2013

|

EU/EFTA

|

1,8

|

|

North America

|

1,9

|

|

Asia

|

6,3

|

|

Middle East

|

15,5

|

|

Africa

|

38,3

|

Source: EASA, Annual Safety Review (2013)

The available data also shows that the rate of fatal accidents for EU/EFTA Member State operated aeroplanes in scheduled passenger operations remains stable since 2010. Between 2005 and 2013 the number of flight movements under instrument flight rules in the EUROCONTROL area has increased by only 2.5% due to the economic downturn of 2008.

Figure 1: Rate of fatal accidents in EU/EFTA Member States and third country operated scheduled passenger operations, aeroplanes above 2250 kg MTOM, 2004-2013 per 10 million flights

Source: EASA, Annual Safety Review (2013)

When it comes to non-commercial aviation, or 'General Aviation', it is at present not possible to calculate accident rates in a similar fashion as for commercial air transport, due to unavailability of exposure data (number of flights or flight hours). Nevertheless, an approximate picture of General Aviation safety can be given using as exposure the size of the fleet. Using this method, we can assume that the rate of fatalities has been decreasing, but that the level of safety of General Aviation in the EU is slightly worse than in the US (Figure 2). Anecdotal evidence suggests that the reduction in the level of fatalities partly results from the reduction of General Aviation activity in the EU - it is however not possible to verify such a proposition due to lack of exposure data.

Figure 2: Comparison of General Aviation safety in the EU and US

Source: EASA

2Problem definition

The problems selected for analysis have been chosen on the basis of the following primary sources:

(a)Results of the public consultation conducted by the services of the Commission (Annex II provides a summary);

(b)

Opinion of the European Aviation Safety Agency

;

(c)

EASA Management Board Sub-Group Report on the Future of the European Aviation Regulatory System

(Annex V provides a summary of recommendations);

(d)

Report on the evaluation of the functioning of Regulation (EC) No 216/2008

conducted under Article 62 of that Regulation (Annex IV provides a summary of recommendations);

(e)Two support studies [hyperlink to be added] contracted by the Commission (Annex I provides further details);

(f)Own analysis by the services of the Commission.

The following sections of this Chapter will refer back to the above sources when substantiating the identification of a particular problem which has been selected for analysis in this impact assessment. The problems identified concern the technical framework for civil aviation safety. Where other technical domains of aviation regulation, such as aviation security, are taken into account, this is done to the extent that there are interdependencies between safety and these other technical domains. Environmental protection with respect to aeronautical products' certification is already within the scope of Regulation (EU) 216/2008, and is accordingly also within the scope of the present initiative.

Table IV at the end of this Chapter presents the relationship between the problems identified and their drivers. It also indicates the relative importance of the specific problem driver for each of the problems.

2.1Description of the main problems

2.1.1The present regulatory system may not be sufficiently able to identify and mitigate safety risks in the medium to long term

The European Aviation Safety Plan (EASp) identifies the main systemic, operational and emerging issues which present risk to safety of civil aviation in the Union (Annex XXI provides further details). However, the purpose of this initiative is not to deal with specific operational issues (such as loss of control in flight or runway excursions), as important as they may be. Such operational issues are already within the scope of the Union competence and are being dealt with by EASA and the Member States' aviation authorities. The two exceptions in this respect, identified by the impact assessment and for which Union action is examined, are ground-handling and security aspects of aircraft and aviation systems' design. The relevance of these two issues for the maintenance of aviation safety are analysed under Section 2.2.3.

Other than that, this impact assessment looks at aviation safety from a systemic perspective. In this respect the Commission services have identified two main issues which require attention: shortages and inefficient use of resources by aviation authorities, as well as reactive nature of aviation safety regulation and oversight.

The above mentioned issues, and especially those related to the use of resources and safety management, are considered as system weaknesses which may make it more difficult to maintain the present safety record in conditions of expected traffic growth and increasing complexity of the aviation system. They also contribute to other problems as identified in this Chapter.

The evidence collected by the Commission supports the need for additional, proportionate efforts to maintain the current good safety record of the Union in conditions of traffic growth and other future developments. In particular, the safety performance study contracted by the Commission estimates that, to counterbalance the expected increase in traffic volume in Europe, the required risk reduction should amount to around 25% in the short term (10 years) and 60% in the long term (30 years). These figures are in line with the assumptions for the SESAR project, which estimates the need for a 40% reduction in accident risk per flight hour in Step 1 of the project.

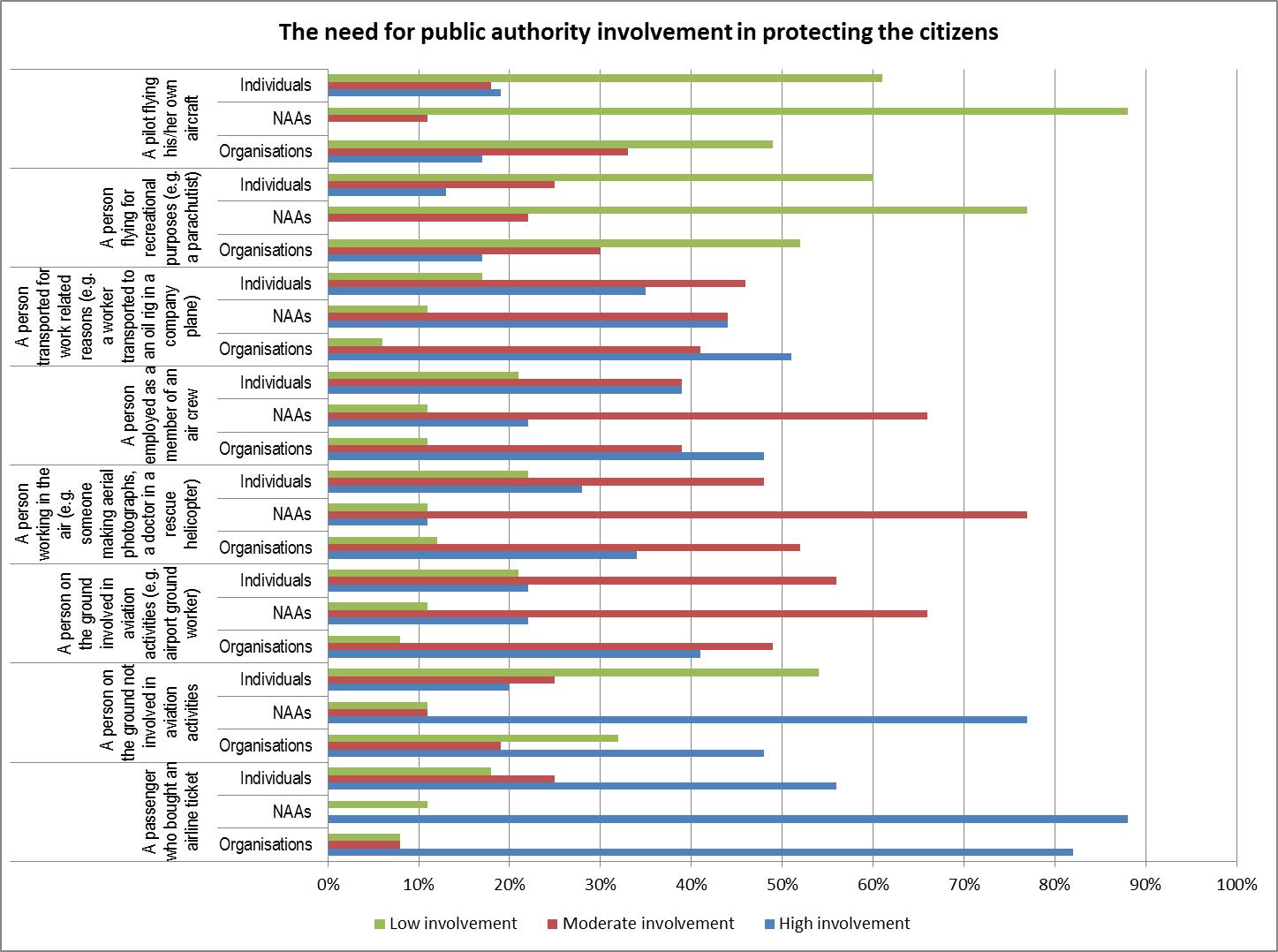

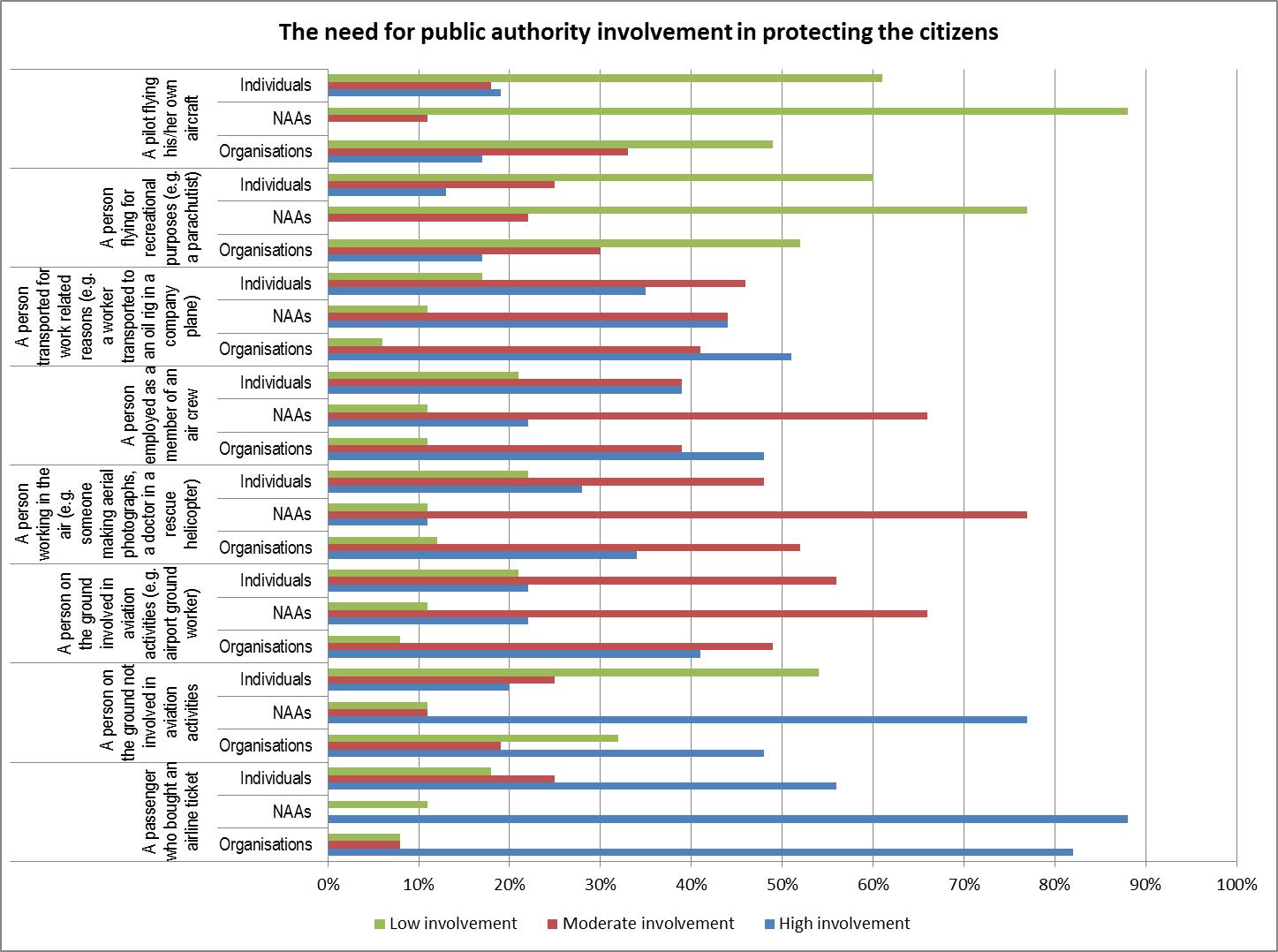

The uncertainty about future safety performance of the system was also highlighted in the results of the Commission public consultation, where 77% of National Aviation Authorities and 75% of all organisations were of the opinion that the EU's ability to identify and mitigate risks has to be improved going forward.

Similarly, the Article 62 evaluation stated that the present ‘largely positive picture of air safety in Europe cannot be taken for granted and both regulators and regulated must continue to maintain and even improve Europe's record on aviation safety.’ It also warned that ‘any deviation from the highest standards of safety could have significant negative impact on Europe's air transport industry.’

This analysis is in line with the approach of other leading civil aviation safety authorities in the world. In particular, the ICAO Resolution on the Global Aviation Safety Plan stresses that the ‘expected increase in international civil aviation traffic will result in an increasing number of aircraft accidents unless the accident rate is reduced.’ Similarly, the US Federal Aviation Administration recognises the need to achieve the next level of safety by 2025 in a proactive manner, by augmenting the traditional methods of analysing the causes of accidents and incidents.

2.1.2The present regulatory system is not proportionate and creates excessive burdens especially for smaller operators

While the EU aviation safety system has been so far effective, it achieves good safety performance at a disproportionate cost. High costs are largely attributed to overregulation which affects especially SMEs and General Aviation. This view was strongly expressed in the Commission public consultation, where 77% of National Aviation Authorities and 82% of all respondent organisations stated that safety regulation is too detailed or difficult to comprehend; 88% of National Aviation Authorities and 83% of all respondent organisations stated that existing safety levels could be maintained with lower costs. The EASA Opinion concludes that the current regulatory system puts an excessive and unnecessary administrative and financial burden on the maintenance and operation of light aircraft. The EASA agency points out in particular that the regulatory framework for light aircraft is not sufficiently differentiated from the regulatory framework for commercial air transport, while the risks involved are different, and that this results - to a certain extent - from the rigidity of the provisions in the Regulation (EU) 216/2008, notably as far as definitions are concerned.

It is notable that nearly half of the respondents to Commission public consultation which expressed dissatisfaction with the current regulatory system are microenterprises employing less than 10 persons. More specifically, with respect to SMEs, the following issues have been identified in the Commission public consultations (see Annex II for further details):

The present system puts excessive requirements on SMEs compared to the achieved safety benefits. It is felt by many contributors that regulations are too complex and beyond the ability of many SMEs to comprehend and be abreast with the constant changes;

The ongoing improvements are focused on non-commercial aviation ('pure' general aviation), and not sufficient attention is being given to more proportionate regulation for commercial activities of SMEs;

Regulations are difficult to implement by companies where a single individual performs roles which in an airline or a big manufacturer are responsibility of multiple departments.

The results of the Commission public consultation and the support study on safety performance point to the fact that disproportionate and overly complex regulation results not only in excessive cost to demonstrate compliance but also that resources of the operators and National Aviation Authorities are diverted from operational and oversight work as well as from innovation (activities important for safety and competitiveness of the EU aviation), towards administrative tasks.

Several attempts were made by the Commission to quantify the costs of overregulation more precisely. While no comprehensive picture could be obtained (manufacturers in particular indicated that companies do not routinely account certification costs separately from overall product development costs), a number of cases of overregulation were identified and are presented as examples (Case I). Overall it seems that overregulation particularly affects businesses and operators involved in light and general aviation. This observation is also supported by the conclusions of the EASA Management Board sub-group report.

|

Case I: Identified examples of quantified overregulation

-Overregulation leading to high maintenance costs for small aircraft and gliders. A case study provided by Europe Air Sports and concerning one of the EFTA States shows that maintenance costs for small aircraft and gliders increased by 50% since 2003. Figure 2 above demonstrates that General Aviation in the US has a better safety record than the EU, even though the requirements for this sector in the EU are more demanding;

-Disproportionate costs for advanced private pilot training. Instrument rating training costs are approximately twice as big in Europe as in the US. These differences in training costs make an overseas training an attractive alternative for European private pilot licence holders who consider obtaining an instrument rating. Compared to the US, the share of private pilot licence holders with instrument rating is much lower in the EU than in the US (5.2% and 26.8%, respectively). These economic effects have also safety implications: the instrument rating qualification is an effective way of avoiding accidents in bad weather conditions. New instrument ratings that were recently introduced by the EU took into account the special needs of private pilot licence holders by making instrument rating training more accessible and less costly. Further efforts are however needed to increase the number of private pilot licence holders with instrument ratings in the EU. This may include considering training outside approved training organisations.

-Regulatory burden is created by a lack of responsiveness of the current rulemaking system. When comparing the average duration of current technical rule development to the development of an industry standard a rough comparison indicates that it takes approximately 3 times longer to develop a rule compared to a standard, i.e. 3 years for a rule versus 1 year and 2 months for the industry standard. Although referring to industry standards is not always an alternative to a traditional rulemaking process, this comparison points to potential time and cost savings which could be achieved by increasing reliance on industry standards.

|

2.1.3The present regulatory system is not sufficiently responsive to market developments

Evidence shows that the regulatory system is not sufficiently adapted to market developments. This regards the ability of the system to: (i) quickly accommodate safety and efficiency enhancing technologies, and (ii) to respond to new operational practices of the industry.

(a)Aspects related to technologies:

The present system is largely based on prescriptive regulations which often describe, in a detailed manner, the required way of conduct or technical solutions to be used. Although this provides clear guidance to users and compliance with the rules is straightforward, this approach has also resulted in some parts of the aviation industry slowing down in adopting technological safety and efficiency improvements, as acceptance of new technologies and certification methods necessitates frequent changes in the requirements. In addition, it limits alternatives for achieving compliance and thus discourages innovation.

88% of the National Aviation Authorities and 72% of all organisations which contributed to the Commission public consultation stated that the system based on prescriptive rules hampers innovation. Similarly 77% of the National Aviation Authorities and 83% of all organisations stated that excessive reliance on prescriptive regulations puts the EU industry at a competitive disadvantage.

The safety performance study concluded that: ‘the current prescriptive basis of regulation is seen as blocking or slowing down innovation by a continued focus on mandating specific methods and solutions rather than outcomes and not leaving much flexibility.’

This problem can be very well illustrated with the example of General Aviation, where the increasing costs of operating certified aircraft and the slow level of incorporation of new technologies, which often represent safety improvements, has contributed to the shift of many pilots towards less regulated, ultralight and other Annex II aircraft, as Figure 3 illustrates and the EU General Aviation roadmap confirms. It is notable that the average age of certified General Aviation aircraft is 40 years. Similarly, for drones the existing rules do not reflect well the needs of this newly emerging technology.

Figure 3: European deliveries of Single Engine Piston (SEP) and non-certified light aircraft

Source: Daher-Socata (EASA General Aviation Conference, Rome 2014)

With respect to promotion of environmentally friendly technical solutions and technologies, the regulatory system based on Regulation (EC) No 216/2008 has not evolved since the adoption of the predecessor of this regulation in 2002, while the attention paid by the EU and citizens to ‘greening’ of air transport has significantly increased over the last twelve years. The scope of Regulation (EC) No 216/2008 is limited to environmental compatibility of aeronautical products only, and the automatic link with ICAO requirements - which does not exist for safety rules - does not permit the EU to consider possible better alternatives to minimum international standards, and weakens the negotiating position of Member States and the EU in ICAO. The emergence of electric engines is also not reflected in Regulation (EC) No 216/2008, which defines ‘complex aircraft’ by referring to turbine powered engines only.

Finally, the manufacturing industry has voiced concern during EASA and Commission consultations that the present certification system, due to lengthy procedures and in particular limited availability of resources at EASA (see point 2.2.4), might not be able to respond to future industry demand for product certification in a timely manner, which could lead to financial penalties and more generally, to a competitive disadvantage for European industry. More specifically, it is estimated that a 6-month delay in delivery of an aircraft to an airline can lead to penalties to the manufacturer of up to 2% the price of each aircraft, or cancellation of orders to the benefit of competitors. The development costs exceed 10 billion € for a new large aircraft. If a design issue is detected at a late stage of the certification process, the development costs can increase by 10%.

(b)

Aspects related to operational practices of the industry:

The creation of the single aviation market has lifted the limits imposed on the airline industry by Air Services Agreements, and airlines can now operate within the EU as if national borders did not exist. Similarly, the recognition of certificates enabled by EU legislation means that individuals can now claim recognition of their privileges anywhere in the EU.

The liberalisation has also resulted in emergence of new employment practices, and business models. This includes multinational airline consortia, which hold multiple Air Operator Certificates (AOCs) in order to be able to satisfy ownership and control requirements of Air Services Agreements of individual Member States with third countries. However this necessity to hold separate AOCs from multiple Member States prevents such consortia from operating as a single airline which would allow for interoperability of assets and associated safety benefits (see Case II). It has also become a common practice for airlines to use remote bases of operations which allows business development away from the principal place of business and outside the territory under the jurisdiction of the certifying authority.

|

Case II: One Air Operator Certificate (AOC) or four?

One of the EU tour operators holds four AOCs from separate Member States. The group would like to merge these certificates in order to eliminate inefficiencies caused by concurrent activities, achieve higher integration of fleet, and enhance safety by using only one process across the whole operation. At the same time the group does not want to jeopardise the traffic rights it enjoys from the Member States where its AOC holders are incorporated. While for the purpose of intra-EU operations one AOC and operating licence suffices, an airline must be licensed and certified by the designating Member State in order to exercise traffic rights outside the EU, if a third country did not accept an EU designation clause.

The current EU regulatory system does not explicitly envisage a 'joint AOC' issued by several states, although the concept of a joint air transport operating organisation is allowed by the Chicago Convention and has been effectively used by three EU/EFTA States based on an international agreement concluded in 1951. In 2014 at least three EU airline consortia expressed interest in merging their AOCs into a joint approval, while continuing to be able to exercise traffic rights to third countries from their Member States of establishment.

|

Evidence does not indicate that any of the new business models is 'unsafe', although the oversight of multinational organisations and certificate holders moving between jurisdictions is more challenging and requires close collaboration between National Aviation Authorities. For example:

The report issued by the Air Accident Investigation Unit of Ireland following the fatal accident of the Fairchild SA 227-BC Metro III EC-ITP which occurred on 10 February 2011 at the Cork airport, showed that inadequate oversight of a geographically remote operation by the State of the Operator can be a contributing factor to an accident;

At least three Member States reported to the Commission or EASA that they had encountered situations where licence holders claimed recognition of certificates which had been earlier revoked or suspended by the (another) issuing Member State (see Case III).

Task Force on Measures Following the Accident of Germanwings Flight 9525 observed that the introduction of pan European medical certification has given pilots freedom to apply to any aero-medical examiner certificated by any EU/EFTA Member State. At the same time, the authorities and aero-medical examiners do not have easy access to information on whether a pilot has been denied a medical certificate in another State, nor the reason for eventual denial.

|

Case III: Challenges in cross-border enforcement (Irregularities in pilot licensing)

In 2014 two cases of irregularities with respect to the conduct of training courses and skill tests / proficiency checks were reported by two Member States. The investigation conducted jointly by the two Member States concerned necessitated review of documentation concerning hundreds of pilots, several training organisations and numerous instructors and examiners located in different countries. As a result of the investigation a number of pilot licences were suspended. The cross-border investigation made the case particularly complicated and the current regulatory framework proved to be of limited help. The authorities concerned and EASA also concluded that in absence of a central repository of pilot licences it would be difficult to detect if the individuals concerned did not apply for new licences in other Member States.

|

The Article 62 evaluation concluded that new business models are going to impact heavily on the work content of the EASA system. These findings are also reflected in the Commission public consultation, where 88% of the National Aviation Authorities and 83% of all respondent organisations stated that the EU system lacks flexibility to accommodate new business models, while 77% of the National Aviation Authorities and 49% of all respondent organisations stated that there is a need to change the legislative framework to better accommodate multinational operations.

The 2013 EASA Annual Standardisation Report highlights transnational business models and operators having multiple principal places of business as new challenges which need to be addressed by the oversight authorities, and for which standardised implementation of regulations is not a sufficient solution on its own.

The 2015 report of the EASA working group on safety implications of new business models concluded that regulators’ own procedures and oversight methodologies are not adapted to the developments in business models and that there is insufficient guidance on cooperative oversight.

2.1.4There are differences in organisational capabilities between Member States

The availability of qualified personnel is an essential pre-requisite for effective oversight and certification by EASA and National Aviation Authorities. At the same time evidence shows that there are significant differences in organisational capabilities of Member States, which:

Create potential safety risks, as some Member States are not sufficiently capable of ensuring effective oversight of EU legislation (see below);

Contribute to mistrust between the Member States. The support study on resources reported for example that four out of sixteen National Aviation Authorities interviewed stated that they do not automatically accept certificates issued by some other authorities due to lack of trust in their compliance. This is also one of the reasons why cooperative oversight is embraced with reluctance by Member States;

Result in varying interpretations of requirements by Member States which negatively affects the level playing field on the market. Many of the organisations and National Aviation Authorities which contributed to the Commission's public consultation expressed concern over this issue;

The support study on resources also concluded, based on 25 interviews, that 'both industry and the National Aviation Authorities must deal with an unequal playing field in the different Member States, which may potentially undermine the common market/system’. The study indicated that these differences stem from varying approaches of national authorities to oversight, availability of resources and qualification of staff, as well as differences in financing oversight (with some Member States recovering the costs through fees and some financed through Member State budgets);

The identification of this problem is further supported by the following evidence:

66% of National Aviation Authorities and 68% of all organisations which contributed to the Commission public consultation were of the opinion that 'the capabilities of national authorities to perform oversight differ increasingly';

The EASA standardisation programme shows that, at the end of 2014, ten (30%) of EU/EFTA Member States had open supplementary reports with non-resolved safety relevant findings, meaning that they did not adequately implement corrective action plans. Shortages of staff and its inadequate qualification were identified by EASA as two main reasons for inadequate oversight by National Aviation Authorities;

The support study on resources concluded that, given the current working methods of authorities, the aviation safety resources in the EU are insufficient compared to workload, and that there are significant differences in supervisory approaches between the Member States;

The safety performance study concluded that approximately only 1/3 of National Aviation Authorities are ‘sufficiently well-resourced and skilled to exercise appropriate oversight’. While this does not mean that safety is in danger, it points to the fact that the levels of safety assurance vary across the EU;

The Article 62 evaluation panel concluded that it is urgently needed to find a solution to the problem of weaknesses in safety oversight abilities of some Member States.

At present, the EU already has a number of tools for addressing deficiencies identified in safety oversight capabilities of a Member State. These include infringement procedures to be launched by the Commission, the possibility to suspend recognition of certificates under Article 11 of Regulation (EC) No 216/2008, and imposing complete or partial operating restrictions on operators certified by an EU Member State using Regulation (EC) No 2111/2005. However, these measures either take long to be implemented (which is the case for infringements), or simply stop the entire operation without resolving the underlying problems of deficient national oversight.

2.2Underlying problem drivers

There is no one-to-one relationship between the problem drivers identified below and the problems set out in the preceding section. This means that one problem driver can feed into more than one problem. For example the problem drivers related to shortages and inefficient use of resources affect Problem No 1 related to the future performance of the EU aviation safety system, as well as Problem No 4 related to organisational capabilities of Member States. This is illustrated in Table 4.

2.2.1Level and type of regulation does not sufficiently correspond to the risks associated with different aviation activities

According to the results of the public consultation, one of the primary reasons why the EU system creates excessive burdens for Member States and stakeholders is the fact that the level of regulation and the measures applied do not sufficiently differentiate between the risks involved in different types of activities. Although the preamble to Regulation (EC) No 216/2008 recognises that rules should take into account the risk associated with the different types of operations and complexity of aircraft, this principle is not very well reflected in the actual provisions of this regulation, which, for example, subjects all aircraft to a type certification procedure irrespective of the risk involved. The different classifications of operations provided in the regulation are also quite rigid and make reference to technical criteria (such as type of engines or maximum mass) which are better suited for lower level implementing measures.

The lack of sufficient differentiation between acceptable levels of risk has resulted, especially in the initial phases of developing the EU aviation safety regulations, in a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach which is particularly disproportionate for smaller organisations. The EU General Aviation Roadmap concludes that ‘much regulation has been blanket regulation, which aimed to cover all possible risks by saying something about everything, although the vast majority of fatalities are caused by a small set of recurring causes’. In some cases (see Case IV) the ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach has affected the development of the single aviation market.

|

Case IV: Light Sport Aircraft: 'one size fits all' (or not) for product certification and production

The light sport aircraft category covers a range of lightweight aircraft which represent an entry level for many private pilots. In the EU the light sport aircraft are subject to a type certification procedure by EASA and organisations which are involved in their design and manufacture must hold design and production organisations approvals, similar as manufacturers of large transport category planes.

In the US, the light sport aircraft can be designed in accordance with consensually developed industry standards, and put on the market based on the statement of conformity issued by the manufacturer. As a result, the design and production approval costs for light sport aircraft are on average 2.5 higher in the EU than in the US. Because of a more favourable regulatory environment overseas, more than 60% of EU produced light sport aircraft are sold in the US.

|

The second reason for excessive burdens, also highlighted in the results of the Commission and EASA public consultations, is the fact that the EU overly relies on legislative instruments as a means of addressing safety risks while not sufficiently exploring other tools providing more flexibility in addressing risks. Such alternative tools mentioned by the respondents include the use of industry standards, training and safety promotion.

2.2.2System is reactive and predominantly based on prescriptive regulations and compliance checking

The EU aviation safety system is largely based on prescriptive rules, usually developed following lessons learned from accidents, which are controlled through periodic audit-type checks focusing on procedures and manuals. This prescriptive and reactive approach, which has been an international standard so far, allowed the EU to achieve the present good safety record. The results of the Commission public consultation also show that prescriptive rules have many other advantages, such as legal certainty and straightforward compliance checking.

On the other hand the EASA Opinion indicates that ‘compliance with detailed technical or prescriptive standards will in the future be less and less effective in ensuring a satisfactory level of safety in all cases’. This is because the EU has reached a situation where accident causes have become operator unique. Controlling such unique threats through generic legislation is very difficult.

To achieve further safety improvements, the EU has now mandated, in the Implementing Rules, a business-like approach to managing safety risks. This approach is based on the new Annex 19 to the Chicago Convention, which contains safety management requirements for industry and States. Although progress has been made in implementing this new approach, the work is far from complete:

Safety Management Systems are a recent requirement and not yet mature if we take the EU as a whole. At the State level, authorities are moving ahead with implementation of State Safety Programmes, but this remains voluntary as the adoption of Sates Safety Programmes is not yet mandated by EU law. Furthermore, evidence collected by EASA shows that there are still large differences between States, and that performance based elements (e.g. agreement on safety performance indicators for industry organisations) are posing greatest difficulties for Member States in the State Safety Programme implementation process;

The EU has not yet established a fully operational European Aviation Safety Plan, which would allow it to identify and address risks collectively as a region. This is partly due to the fact that Safety Management Systems and State Safety Programmes are not yet mature (see above), and partly due to the fragmentation of the safety management process at EU level, where safety information is scattered, in certain respects incomplete or of sub-standard quality. There is also a lack of a process allowing the EU to identify risks in a systemic and evidence-based manner. The implementation of the European Aviation Safety Plan is voluntary and the effectiveness of the actions contained in the plan is not monitored, as highlighted by the EASA Opinion.

2.2.3Inconsistencies and gaps in the regulatory system

A number of gaps and inconsistencies have been identified in the present regulatory system. These result primarily from the high complexity of this system. A clear majority (73%) of all organisations, including National Aviation Authorities, which contributed to the Commission public consultation, believe that there are gaps, overlaps or contradictions between the different domains of EU aviation safety legislation. Many of the contributions point to the general problem of inconsistencies stemming from varying interpretations of EU requirements by Member States which has also been confirmed by the support study on resources.

Many contributors to the Commission consultation highlighted inconsistencies between EU requirements for airborne and ground-based components of the air traffic management system. With regard to the latter issue, the Commission understands that this refers to the problems with regard to deployment of data-link technologies, which are already being addressed. The stakeholders and Member States also identified the lack of a common safety framework for drones as an issue for action at EU level. The Commission furthermore takes note of the concerns expressed by many stakeholders with regard to inconsistencies between occurrence reporting obligations in the Implementing Rules adopted under Regulation (EC) No 216/2008 and the new regulation on occurrence reporting. The Commission believes that alignment of the reporting requirements has ensured that the two systems are consistent and complementary and therefore that this issue is also already being addressed.

Another gap in the present EU regulatory system has been identified with respect to security aspects of aircraft and aviation systems' design, including cyber-security, where the EU currently lacks a clear mandate to act. Essential requirements to Regulation (EC) No 216/2008 do not explicitly address security of aircraft design. Essential requirements for airworthiness only provide that with respect to systems and equipment, design precautions must be taken to minimise the hazards to the aircraft and occupants also from reasonably probable external threats. EASA relies on this broad formulation to assess the resilience of aircraft design with respect to certain security threats, in particular related to cyber-security, but does not have a clear competence to propose relevant implementing measures or to mandate design changes addressing security threats for in-service aircraft. The EASA Opinion signals the need to address security aspects of aircraft airworthiness, where today the Agency has encountered a number of practical problems in addressing safety risks due to lack of a clear mandate to act. Technical aspects of aircraft security related to the design of aircraft and aviation systems have been also identified by a number of contributions to Commission public consultation as requiring further EU action. At the same time however the stakeholders cautioned that cyber-security goes beyond technical aspects of aircraft and related systems and that aviation cyber-security measures should be consistent with the overall EU cyber-security policies. The Article 62 evaluation recognised that the security of communications between the ground and aircraft should be comprehensively addressed by the EU regulatory system, as it has clear safety implications. From a general policy perspective, the Commission proposal for a directive on network and information security (NIS directive) identifies the aviation sector as a critical infrastructure, vital to the EU economy and societal interests which needs appropriate protection against cyber threats.

Furthermore, there are areas of aviation regulation where safety and security matters are so closely linked together that they should be considered jointly in order to avoid gaps or unintended consequences, and carefully balance any safety/security trade-offs that may have to be made when imposing new requirements on operators. Such close relationship between safety and security exists with respect to aircraft operations and in particular in-flight security measures, which at present are regulated in parallel by two separate legal instruments: Regulation (EC) No 216/2008 and Regulation (EC) No 300/2008. While the results of the public consultations do not point to the need for a complete integration of legal frameworks for safety and security, they did however bring to the attention of the Commission the need for better management of interdependencies between these two domains.

In addition, the EASA Opinion highlighted the need for an EU mechanism for conformity assessment of aviation security equipment, the absence of which is currently considered a stumbling block towards the creation of an EU market for manufacturers of airport screening and explosive detection equipment. With respect to this issue, a separate initiative is ongoing under coordination of DG HOME.

Moreover, the EASA Opinion and Article 62 evaluation identified safety gaps with regard to ground handling. This is an area for which presently no safety provisions directly addressing the service providers exist at EU level, and which makes oversight and mandating corrective action by the competent authorities difficult. All interested stakeholders, with the exception of airlines, point to the fact that regulatory action is necessary, in particular with respect to training of ground handling staff. The airlines believe that they are sufficiently able to control the safety of ground handling through contractual arrangements with the providers and that the costs of regulating ground handling at EU level would outweigh the potential benefits.

The EASA Management Board sub-group also highlighted the issue of ground-handling as requiring analysis, but noted that further regulatory intervention should be based on a clear safety case. In this respect, the safety data shows that since 2005, ground handling occurrences in the EU have constituted 6% of fatal accidents, 15% of non-fatal accidents and 2% of serious incidents. There are on average 3 500 risk-bearing ground handling occurrences reported annually, which is between 9%-11% of all risk-bearing occurrences reported. Ground handling accidents constitute the fourth biggest accident category in the period of the last ten years after loss of control in flight, post impact fires, and system or components failures not related to the engine/propeller (See Annex XXI for information about other top categories of accidents in the EU).

The main contributing factors to ground handling risk-bearing incidents are a lack of standardisation of ground handling procedures, not always sufficient training of staff, and deficiencies in safety management, including with respect to occurrence reporting. There is no evidence that Europe-wide voluntary safety initiatives have had a significant impact in improving ramp safety (see Annex XX for further information about ground handling market and safety of ground handling operations). With the expected growth in air traffic, the main European air hubs reaching full capacities, increasing pressure on aircraft turnaround times, and emergence of composite aircraft which are more prone to ground damage, the deficiencies in safety of ground handling operations become an issue that needs addressing. In addition, the ground handling industry also highlighted the inefficiencies stemming from repetitive audits and inspections of the same service providers by multiple airlines and aviation authorities.

With regard to environmental protection, the current Regulation (EC) No 216/2008 makes Annex 16 to the Chicago Convention (as regards setting minimum standards for aircraft noise and engine emissions) directly applicable in EU law, while in the area of safety ICAO standards are met through the adoption of implementing rules. This difference in approach excludes the possibility for the EU to deviate from ICAO environmental standards for products and thus weakens its negotiation position at international level and prevents the EU from considering possible better alternatives to minimum international standards. For example, the fact that ICAO environmental standards for tilt-rotor aircraft are applicable only as of 2018, the current certification projects for such aircraft in the EU do not cover noise aspects. Another example is the ongoing discussions in ICAO on a new standard in respect of aircraft engine CO2 emissions which have been significantly influenced by the US environmental protection agency announcement of an intention to develop a national CO2 standard – at present the EU cannot use a similar negotiating leverage. Stakeholders who contributed to the public consultation do not see a need for changing the scope of the current EU environmental action under Regulation (EC) No 216/2008, which is limited to environmental compatibility of products. The contributions received point however to the need of better considering interdependencies between aviation safety and environmental legislation (in particular chemicals legislation under the REACH system).

The Commission has further identified inconsistencies in the EU legislation concerning leasing of third country registered aircraft - an issue which has been already identified in 2013 in the context of the EU internal aviation market 'fitness check'. With regard to dry lease-in of foreign registered aircraft the EU safety legislation allows, subject to a number of conditions, such arrangements, while the internal market legislation (Regulation (EC) No 1008/2008) is not clear whether they are allowed or not which leads to legal uncertainty. This inconsistency has been highlighted also by a number of Member States, and an airline trade body which highlighted that 'registering and deregistering aircraft registered in a third country for the typical duration of seasonal leases is complicated and costly'. With regard to wet lease arrangements between EU operators, while Regulation (EC) No 1008/2008 requires a prior safety approval from the relevant authority, the EU safety legislation does not impose on such arrangements any lease specific conditions in addition to the need of the lessor (AOC holder) to comply with usual EU requirements for flight operations and aircraft maintenance. The safety value of such prior approval is questionable, especially in view of the fact that airlines are now also obliged to monitor the safety of the services they contract from other providers. At the same time leasing is a crucial tool for airlines in maintaining operating flexibility – it is estimated that nearly 70% of aircraft in operation in the EU are leased aircraft.

Finally, inconsistencies have been identified with respect to the way Member States notify to ICAO differences between international standards and recommended practices and EU requirements. The analysis of the content of the differences notified by 23 Member States (322 items) to ICAO through the EFOD system revealed that EASA’s recommendation concerning the type of a difference to be notified was followed in only 29.19% of cases (see Annex VIII for more detail). The cases when the recommendations were not followed include mostly no information provided, or outdated references to European rules (JARs or EU-OPS) or to national rules. This lack of uniformity undermines the consistency of the EU system vis-à-vis ICAO and third countries and stands in the way of achieving full coordination between ICAO and EU aviation safety audits of Member States, as envisaged under the EU-ICAO Memorandum of Cooperation on enhanced cooperation.

2.2.4Shortages of resources impacting safety oversight and certification

The support study on resources concluded that, taking into account the current working methods and the size of the EU industry, the aviation safety resources are insufficient. While it is difficult to put a concrete figure on what would be the appropriate level of resources in Europe to continue ensuring a high level of aviation safety in the future, a number of observations can be made.

First of all, the growth in size of the industry has, over the last ten years, outpaced the increase in workforce and budget of aviation authorities, which at the same time have not yet significantly changed working methods. Table 2 illustrates that trend, based on key indicators calculated using samples of EU/EFTA Members States.

Table 2: Trends in evolution of resources and workload in EU/EFTA Member States since 2003

|

|

2003

|

2008

|

2013

|

2003-2013

|

|

Resources

|

|

|

OPS/AIR/FCL National Aviation Authority staff (MS=17)

|

1 574

|

1 727 (+10%)

|

1 659 (-4%)

|

+5%

|

|

National Aviation Authority budget (MS=16)

|

EUR 439 million

|

EUR 558 million (+27%)

|

EUR 530 million (-5%)

|

+21% / -3% if adjusted for inflation

|

|

Workload

|

|

|

CAT fleet size (MS=22)

|

3 494

|

4 127 (+18%)

|

4 307 (+4%)

|

+23%

|

|

AOC holders (MS=31)

|

1,221

|

1,304 (+7%)

|

1,201 (-8%)

|

-2%

|

|

Pilots (MS= 23)

|

139 258

|

176 575 (+27%)

|

175 383 (-1%)

|

+26%

|

|

FTOs (MS=25)

|

1 544

|

2 010 (+30%)

|

2 047 (+2%)

|

+33%

|

Source: Support study on resources

In addition, the transition to the EU regulatory framework has created transition costs for the authorities, and in some cases increased workload due to the more demanding and complex regulatory framework (see Case VI as an example) and standardisation requirements. Furthermore, budget constraints and divergences in the funding of authorities come into play, as demonstrated by the support study on resources. Especially the small authorities funded through government contributions find it difficult to attract competent personnel from the market (see Case V).

|

Case V: Budget constraints (Source: support study on resources)

Among the primary problems cited by nearly all Competent Authorities is the imbalance created by an increase in workload alongside decreasing budgets in the aftermath of the 2008 economic crisis. There are considerable variations in the size of Competent Authorities’ budgets, with larger Member States having relatively larger budgets than their smaller counterparts on account of the relative size of their respective workloads. In addition to this however a number of Competent Authorities recorded extremely low budgets which may be indicative of an even greater imbalance between Member States. For example, budgets in large Member States range from EUR 40 – 61 million, while in certain smaller Member States, budgets range from EUR 5 million to as low as EUR 1.1 million. While the latter group has a smaller workload than the former, the workload-budget disparity is considerably greater for small Competent Authorities.

|

The Article 62 evaluation concluded that in the current economic climate, there is a huge strain on the resources of Member States and EASA, and that it is incumbent on all partners in the system to strive for greater efficiency in the use of limited resources. It concluded further that some of the National Aviation Authorities are finding it difficult to fulfil their statutory obligations related to safety oversight due to staffing/financial problems.

|

Case VI: New regulatory requirements for ballooning

Before the establishment of the EU aviation legislation, some of the Member States were delegating oversight and certification in certain sectors of general aviation, for example ballooning, to user organisations, such as national aero-clubs. The EU legislation harmonised requirements for the production and maintenance of balloons as well as for their operations and pilots' competence. Member States which were not directly involved in that activity before now have to develop the necessary expertise and recruit additional personnel.

|

Also results of the EASA standardisation programme identified shortages in resources in respect of the size, scope and complexity of the regulated industry, as one of the two main contributors to inadequate oversight in some of the EU Member States in the fields of Air Operations, air traffic management/air navigation services and Aircrew. Finally, 55% of National Aviation Authorities and 63% of all organisations which contributed to the Commission public consultation stated that 'some National Aviation Authorities do not have sufficient financial or human resources to carry out their oversight tasks'. At the same time, there was no clear position amongst the respondents, whether there are increased safety risks because oversight obligations are not always fully complied with.

With respect to EASA, the total workload of the Agency with respect to product safety oversight workload has increased by 22% between 2011 and 2014, and is expected to further grow by 5% by 2016. The Agency is going to deploy new performance based working methods but anticipates a steady increase in the initial certification and in continuing oversight activities due to the upturn of the aircraft fleets in operation and the increase in the number of type certificates issued. This expectation is confirmed by a review of manufacturers' forecasts which predict the size of the EU fleet to nearly double by 2033. The Article 62 evaluation predicts that in the next twenty years, Europe will need around 250 000 new engineers (25% of the global demand) to accommodate the increase in the size of the fleet, and new aircraft types. Even though the EASA resources for certification are financed by the industry, they are prevented from being adapted to market demand, by an overall EU staffing cap, which may hinder the capability of the Agency to adequately respond to this anticipated growth. The cuts of the Agency's staff financed by fees and charges are applied irrespective of the industry demand for the certification and oversight services. Already today, EASA has to adjust efforts spent on continuing airworthiness to meet industry demands for initial certification as a consequence of the staff ceiling.

The shortages of resources concern not only the availability of staff but also the level of qualifications which have been found sub-optimal in a number of Member States:

The 2013 EASA standardisation report identified insufficient training and qualification of inspecting staff as one of the two main elements contributing to inadequate oversight in EU Member States in the field of Air Operations, Air Traffic Management/Air Navigation Services and Aircrew;

Competence of personnel in the National Aviation Authorities has been also identified as one of the systemic issues to be addressed in the European Aviation Safety Plan 2014-2017. The concerns about the level of training in some National Aviation Authorities have been also identified by the support study on resources.

2.2.5Inefficient use of resources stemming from fragmentation

The inefficiencies of the EU aviation system stem to a large extent from institutional fragmentation and a high number of actors involved. Already the 2007 report of the High Level Group for the Future European Aviation Regulatory Framework stated that 'fragmentation is a major bottleneck in improving the performance of the European aviation system'. Similarly the Article 62 evaluation report stated that the architecture of the aviation safety system is not sustainable in the long term and that the current institutional set-up does not contribute to the maintenance of the high and uniform levels of safety.

The support study on resources concluded that the resources available in National Aviation Authorities and EASA do not operate as a single system and that there is lack of an effective framework for sharing of resources between National Aviation Authorities and between National Aviation Authorities and EASA. The present system obliges National Aviation Authorities to be competent in each domain of aviation safety, even when the aviation activities in such a domain are limited. This does not help specialisation of National Aviation Authorities and prevents achieving economies of scale.

At the same time, the evolution of the EU aviation market and the organisation of safety oversight result in an increasing need for authorities to cooperate with each other. Although a legal basis for cooperative oversight has been already introduced into the EU legislation, the support study on resources showed that sharing of resources is hampered by lack of common working procedures, limited transparency of information about certificates issued/revoked/suspended by Member States, differences in funding of authorities, lack of standardisation in training and qualification of staff, and absence of a common framework for delegation of responsibilities and tasks between authorities as well as practical issues related to recovery of costs, language barriers, and questions associated with liability of aviation authorities. For example, the EASA pool of flight operations and airworthiness experts is hardly used due to the inability of the Member States to finance the use of experts from the pool.

A comparison between the EU and US aviation safety systems shows, despite some structural differences between the two systems, that the US manages an aviation market which is twice as big as in the EU with human resources which are only 29% bigger and a similar budget, as illustrated by Table 3.

Table 3: Comparison between Europe and USA on key indicators

|

Indicator

|

Europe (2013)

|

US (2012)

|

|

Budget

|

EUR 1.13 billion

|

EUR 1.0 billion

|

|

Total aviation safety staffing level (technical and support staff)

|

5 600

|

7 238

|

|

# AOC holders

|

1 201

|

2 686

|

|

# Aircraft on register

|

107 500

|

199 952

|

|

# Active pilots

|

255 204

|

496 053

|

Source: support study on resources

Further inefficiencies result from the fact that Member States must run two or even three systems in parallel: (1) The EU system, which covers the majority of aviation activities in the EU; (2) A national system for Annex II aircraft which are excluded from the scope of Regulation (EC) No 216/2008; (3) A national system for State aircraft, such as police, or fire-fighting, which are also excluded from the scope of Regulation (EC) No 216/2008.

|

Case VII: Complex regulatory framework for aerial fire-fighting

Some EU Member States consider aerial-firefighting as a civil aviation activity. One of such Member States reported in an interview with the Commission that following the entry into force of the EU requirements for special operations, it will have to run in parallel two regulatory systems for aerial works. The national system will cover fire-fighting services which are excluded from Regulation (EC) No 216/2008. At the same time fire-fighting aircraft are also used in that Member State for agricultural operations which fall within EU special operations requirements. The Member State concerned would like to be able to opt-into the EU system for firefighting services to simplify the regulatory framework, and eliminate redundant paperwork resulting from the need to run two systems in parallel.

|

There are also overlaps in resources and cost between EUROCONTROL and EASA, an issue which has been highlighted by the EASA Management Board sub-group report, and quantified by the support study on resources at around EUR 2 million per year.

It may be that the system collectively disposes of enough resources, but that as a result of fragmentation there is a perceived shortage, which was pointed out by the support study on resources. This conclusion has also been suggested by the Article 62 evaluation panel and EASA Management Board sub-group. It is for this reason that this impact assessment puts a stronger emphasis on the need for increasing the efficiency in the utilisation of existing resources, rather than increasing the numbers of available staff, which in the current economic climate would be unrealistic to expect.

Table 4: Problems (limitations of the regulatory system in meeting future challenges), problem drivers and objectives of the initiative

|

|

The present regulatory system may not be sufficiently able to identify and mitigate safety risks in the mid to long term

|

The present regulatory system is not proportionate and creates excessive burdens, especially for smaller operators

|

The present regulatory system is not sufficiently responsive to market developments

|

There are differences in organisational capabilities between Member States

|

|

Level and type of regulation does not sufficiently correspond to the risks associated with different aviation activities

|

☑

|

☑☑☑

|

☑☑

|

|

|

System is reactive and predominantly based on prescriptive regulations and compliance checking

|

☑☑☑

|

☑☑

|

☑☑

|

|

|

Inconsistencies and gaps in the regulatory system

|

☑

|

|

☑

|

|

|

Shortages of resources impacting

safety oversight and certification

|

☑

|

|

☑☑

|

☑

|

|

Inefficient use of resources stemming from fragmentation

|

☑☑

|

|

☑

|

☑☑☑

|

☑ - ☑☑☑ : Relative importance of a specific 'problem driver' for a given 'problem'

|

Specific Objectives (SO):

|

|

1)Eliminate unnecessary requirements and ensure that regulation is proportionate to the risks associated with different types of aviation activities

|

|

2)Ensure that new technologies and market developments are efficiently integrated and effectively overseen

|

|

3)Establish a cooperative safety management process between Union and its Member States to jointly identify and mitigate risks to civil aviation

|

|

4)Close the gaps in the regulatory system and ensure its consistency

|

|

5)Create an effectively working system of pooling and sharing of resources between the Member States and the Agency

|

2.3Baseline scenario

2.3.1Evolution of the problems

The structure of the baseline scenario mirrors the structure of the problem definition.

(a)The present regulatory system may not be sufficiently able to identify and mitigate safety risks in the medium to long term

The EU system will continue the transition to a risk and performance based environment. Safety management systems will continue to mature supported by further guidance, and will be used EU-wide across the industry. The European Aviation Safety Plan will remain a voluntary exercise however and it is likely that not all the Member States will be implementing the actions contained in the European Aviation Safety Plan and reporting back to EASA on its implementation. Safety information available at EU level will be gradually integrated by EASA into a single analysis process, although these efforts may be hampered by the reliability and completeness of this information.

Safety gaps will continue with respect to ground-handling, where experience showed that voluntary action is not sufficient. The risks stemming from cyber-security threats will also remain partly unaddressed, and are expected to intensify with the introduction of more data driven technologies and e-enabled aircraft. Weaknesses in oversight capabilities of some Member States are likely to persist due to continuing pressure on public administrations' budgets, as showed by the support study on resources. These weaknesses, combined with traffic growth, will create additional risks for safety of the aviation system.

Modelling future performance of the EU aviation safety system is very difficult due to already low number of accidents and very low probabilities of system failures. For the purpose of this report, analysis has been performed based on past accident rates and future traffic projections for large aircraft operated in commercial air transport by EU/EFTA air operator certificate holders.

Based on the overall performance of the EU aviation safety system so far, it is reasonable to expect that the system is robust enough to at least maintain the current accident rate. This would however mean that the absolute number of fatal accidents and fatalities would increase by around 30% in the next ten years, due to the expected increase in traffic. The additional economic costs related to accidents under this scenario, taking into account the typical costs inherent in a fatal accident, are assessed to be around EUR 289 million by 2023 (see Table 5).

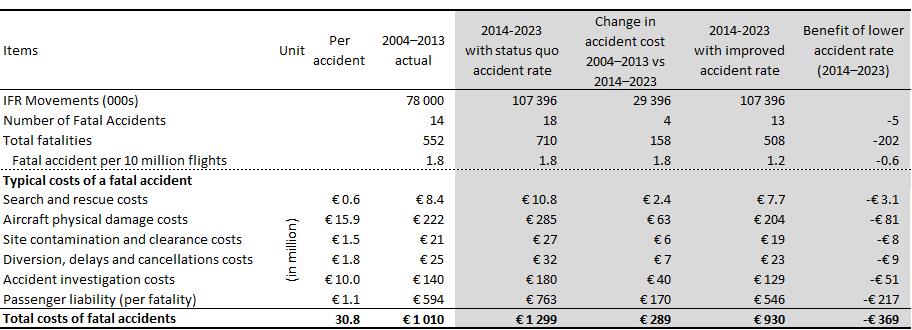

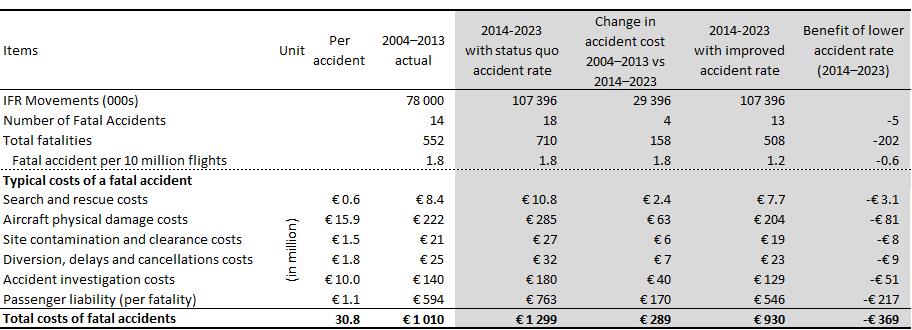

Table 5: Simulation of flight growth scenarios and associated accident costs

Source: EASA

The question therefore is under which conditions the accident rate could improve further in order to compensate for the expected traffic growth. Two aspects have to be considered in this respect. The first observation to be made is that while the system has been able to deliver increasing levels of safety, the rate of improvement has slowed down (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Three year moving average fatal accident rates and an exponential trend line

Source: EASA

The second observation is that past safety improvements did not happen on its own but were depending on the conscious efforts made by industry and the regulators. This observation is supported by the safety performance study, which links future reduction of accident rate with further improvement efforts and in particular successful implementation of safety management systems. This impact assessment study is therefore based on the premise that further safety improvements will be conditional on addressing the weaknesses in the system identified in the problem definition section of the report.

As a first estimate on how large such an improvement could potentially be, the evolution of annual accident rates of EU/EFTA operators may be modelled using a function of exponential decay. This means extrapolating the trend line in Figure 4 into the future.

Based on this assumption, it is estimated that the accident rate may be further decreased from 1.8 to 1.2 fatal accidents per 10 million flights in the next decade (2014–2023), which would mean five fatal accidents and 202 fatalities prevented, as well as EUR 369 million saving in accident costs. This potential improvement would however require further improvement of the regulatory system and corresponding efforts in terms of safety promotion and oversight.

In the 2004–2013 decade there were also 17 non-fatal accidents for every fatal accident with an average €2.6 million aircraft physical damage costs, amounting to almost EUR 620 million. If the non-fatal accident rate would improve with the same rate as fatal accident rate, that would mean almost 85 non-fatal accidents with an estimated EUR 221 million aircraft damage prevented in the 2014–2023 decade.

(b)The present regulatory system is not proportionate and creates excessive burdens especially for smaller operators

Further efforts will be made to improve proportionality of the regulatory system and eliminate unnecessary regulation. In particular the General Aviation roadmap will continue to be implemented and EASA will gradually increase reliance on industry standards. A more rigorous impact assessment process is also being introduced by EASA to clearly link rulemaking tasks to safety risks and to consistently take into account non-rulemaking risk control measures, such as safety promotion actions, as possible alternatives.

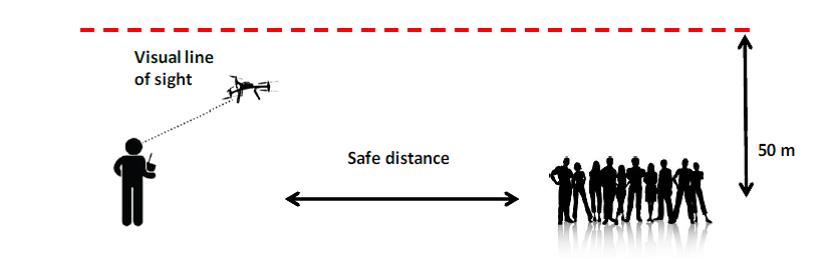

The Regulation (EC) No 216/2008 will not allow however to introduce alternative to a type certification methods of assessing airworthiness of products, nor to grant more extensive competences to Qualified Entities to help Member States in the conduct of certification and oversight activities. Future Implementing Rules may be performance based if needed, but a number of prescriptive requirements in Regulation (EC) No 216/2008, such as detailed definitions or rigid conditions for granting exemptions, will hamper introduction of a truly proportionate regulatory regime, especially for lower risk operations such as light aircraft or drones.

(c)The present regulatory system is not sufficiently responsive to market developments