EUROPEAN COMMISSION

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Brussels, 26.2.2020

SWD(2020) 509 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

Country Report France 2020

Accompanying the document

COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE EUROPEAN COUNCIL, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK AND THE EUROGROUP

2020 European Semester: Assessment of progress on structural reforms, prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances, and results of in-depth reviews under Regulation (EU) No 1176/2011

{COM(2020) 150 final}

Contents

Executive summary

1.Economic situation and outlook

2.Progress with country-specific recommendations

3.Summary of the main findings from the MIP in-depth review

4.Reform priorities

4.1.Public finances and taxation*

4.2.Financial sector*

4.3.Labour market, education and social policies*

4.4. Competitiveness reforms and Investment*

4.5.Environmental sustainability

Annex A: Overview Table

Annex B: Debt Sustainability Assessment

Annex C: Standard Tables

Annex D: Investment guidance on Just Transition Fund 2021-2027 for France

Annex E: Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

References

LIST OF Tables

Table 1.1:Key economic and financial indicators

Table 2.1:Assessment of 2019 CSR implementation (*)

Table 3.1:Outward spill-over heat map

Table 3.2:MIP Assessment Matrix (*)

Table 4.2.1:Financial soundness indicators - all banks in France

Table 4.5.1:Total greenhouse gas emissions per capita (*), tons of CO2 equivalent

Table C.1:Financial market indicators

Table C.2:Headline Social Scoreboard indicators

Table C.3:Labour market and education indicators

Table C.4:Social inclusion and health indicators

Table C.5:Product market performance and policy indicators

Table C.6:Green Growth

Table E.1:Indicators measuring France’s progress towards the SDGs

LIST OF Graphs

Graph 1.1:

Contributions to GDP growth (2012-2021)

Graph 1.2:

Potential GDP growth breakdown

Graph 1.3:

Breakdown of unit labour cost rate of change

Graph 1.4:

Share of market services in export value added (2014)

Graph 1.5:

Export shares (% of national exports) by quality level

Graph 1.6:

Breakdown of the current account

Graph 1.7:

Non-financial corporation consolidated debt

Graph 1.8:

Interest burden evolution

Graph 1.9:

Housing market - Overvaluation gaps

Graph 2.1:

Overall multiannual implementation of 2011-2019 CSRs to date

17

Graph 4.1.1:

Fiscal effort and public debt

Graph 4.1.2:

Public debt in France and in the euro area

Graph 4.1.3:

Public debt projections in France

Graph 4.1.4:

French fiscal rules and MTBF indices vs EU average

Graph 4.1.5:

Structural Balance targets versus outturns

Graph 4.1.6:

Environmental taxes as percentage of total revenues from taxes and social contributions in France and the EU

Graph 4.1.7:

Environmental tax revenues as percentage of GDP in France and the EU

Graph 4.2.1:

Annual growth rate of loans

Graph 4.3.1:

Employment by type (thousand), year-on-year changes

Graph 4.3.2:

Long term evolution of labour market indicators

Graph 4.3.3:

Share of temporary employees and transition rates from temporary to permanent contracts (age group 15-64)

Graph 4.3.4:

Evolution of the task content of jobs (skills) in France, 2000-2018

Graph 4.4.1:

Labour productivity growth per sector

Graph 4.4.2:

Average share of 'zombie firms' between 2010 and 2015

Graph 4.4.3:

Investment levels by sector (% of GDP)

Graph 4.4.4:

Contribution of intangible capital growth to productivity growth (2015), by asset

Graph 4.4.5:

Turnover and employment of multinationals abroad, by country of origin (to rest of the world)

Graph 4.4.6:

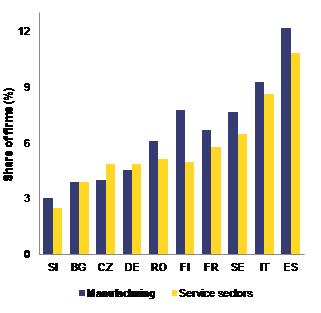

Business churn rates (%) of active companies in selected business services sectors for France and the EU

Graph 4.4.7:

Regional competitiveness index

Graph 4.4.8:

Greenhouse gas emissions per NUTS2 regions

Graph 4.5.1:

Targets and emissions under the effort sharing legislation (% change from 2005)

Graph 4.5.2:

Greenhouse gas emissions by sector with projections

Graph 4.5.3:

Capital investment needs for 2021-2027 in the waste sector (€ mn). Top 6 EU.

LIST OF Boxes

Box 2.1: EU funds and programmes to address structural challenges and to foster growth and competitiveness in France

Box 3.2: Euro-area spillovers

Box 4.1.3: Assessing the redistributive impact of some measures favourable to households’ disposable income

Box 4.3.4: Monitoring performance under the European Pillar of Social Rights

Box 4.4.5: Investment challenges and reforms

Box 4.4.6: The Investment Plan for Europe and InvestEU

Box 4.4.7: Impact of business environment reforms

Box 4.5.8: Energy renovation of buildings

Executive summary

France has sustained its reform efforts yet further measures are needed to continue improving the performance of the French economy (

). Some structural challenges persist, in particular high government debt and high unemployment. France has also experienced a productivity slowdown that calls for continued investment in skills and swift progress implementing the recent vocational education and training reform, as well as measures to improve the business environment. At the same time, expenditure control will be important to bring debt on a sustained downward path. The pension system reform is planned for adoption by the end of the year 2020.

Economic growth moderated in 2019 and is expected to remain close to potential in the near future. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth has decreased since its peak in 2017 and reached 1.2% in 2019 (

). It is expected to remain close to its potential growth rate in 2020 and 2021, at 1.1% and 1.2% respectively. French domestic demand is set to be resilient in 2020 and 2021, following a temporary decrease at the end of 2019. Consumer spending would benefit from purchasing power gains registered since the end of 2018 resulting from lower unemployment and inflation, higher wages and supportive fiscal measures. Investment growth is expected to ease – down from high levels – but remain robust overall following favourable financing conditions. In line with domestic demand, import growth is set to gain momentum. By contrast, the weakening the international environment is expected to weigh on exporters compared to the particularly dynamic years of 2017 and 2018.

Labour market conditions are improving but unemployment remains high, particularly for disadvantaged groups. Despite the slowdown in economic activity since the beginning of 2018, the unemployment rate declined further and reached 8.4% in Q42019. The situation for young people has also improved. However, those with low skills and those with a migrant background face difficulties in integrating in the labour market. Reforms are ongoing to increase their employment prospects. Finally, some sectors appear to face emerging skills shortages and mismatches.

France’s competitiveness continues to show mixed results. After falling for many years, export market shares have recently stabilised, but losses have not recovered. The current account remained broadly stable and the net international investment position marginally improved. In terms of cost competitiveness, the cost of labour (measured as unit labour costs) has grown more moderately than in other euro area and EU countries, with developments in wages remaining contained in a context of sluggish productivity growth. In terms of non-cost competitiveness, French exports of goods are of overall medium to high quality. France maintains the highest quality in aeronautics, cosmetics and beverages.

After a temporary rebound to 3.1% of GDP in 2019, the deficit is set to decline to 2.2% of GDP in 2020. The breach of the 3% of GDP deficit threshold in 2019 is minor and temporary, due to the one-off impact of changes to the employment and competitiveness tax credit (CICE) into a permanent cut in employers’ social contributions. The measures adopted at the end of 2018 in response to the ‘Gilets jaunes’ movement, aimed to improve households’ disposable income, entailed a net deficit-increasing impact of around 0.3% of GDP in 2019. Further measures taking effect in 2020 were adopted in April 2019. These measures include a permanent cut in personal income tax (worth €5bn, i.e. 0.2% of GDP), the reindexation of pensions below €2,000 per month, and an increase in minimum pensions (both amounting to €1.5 bn, or 0.1% of GDP).

High government debt is set to rise slightly. After stabilising in 2018, the government debt ratio is set to rise by 0.5 pps. in 2019, to reach 98.9% of GDP. In 2020, government debt is forecast to remain at 98.9% of GDP, before rising further to 99.2% in 2021, which would widen the gap with the euro area average. While risks to the financing of debt remain limited in the short term thanks to favourable conditions for the State and a large and diversified investors base, the high debt level limits the scope to respond to adverse shocks.

Reforms and targeted investment in skills, digital infrastructure and research and innovation have the potential to unlock productivity gains in the economy. According to the French National Productivity Board, the weak productivity growth of French businesses can be explained in part by factors common to most EU countries. Country-specific factors such as France’s comparatively low skilled workforce, low uptake of information and communication technologies and suboptimal innovation performance also play a role. The implementation of several investment plans as well as the ongoing reform efforts will contribute to addressing these challenges. The full impact of these measures on productivity will take time to materialise. Moreover, the performance in research and innovation is still hampered by the complexity of the research and innovation ecosystem. Continued efforts are crucial to improve the impact and efficiency of public support for research and innovation and reinforcing the links between science and business.

Overall, France has made some progress in addressing the 2019 country-specific recommendations.

There has been substantial progress in implementing measures to facilitate firms’ growth (PACTE Law in 2019).

There has been some progress in:

·addressing skills shortages and mismatches

·focusing investment to ensure the move towards cleaner energy;

·improving the digital infrastructure; and

·continuing efforts to simplify the tax system.

There has been limited progress in:

·reforming the pension system;

·labour market integration and ensuring equal opportunities;

·improving research and innovation performance; and

·reducing regulatory restrictions.

There has been no progress in further detailing and implementing the specific measures outlined in the Public Action 2022 programme.

France performs relatively well on the employment and social indicators highlighted in the Social Scoreboard that underpins the European Pillar of Social Rights. Poverty and inequality are below the EU average and overall the social protection system is effective. Access to healthcare and childcare services is also comparatively good. However, the unemployment rate remains above the EU average, despite several years of decline. Labour market integration remains more difficult for disadvantaged groups. On the quality of jobs, the incidence of in-work poverty is low, but the segmentation of the labour market into different levels of job security and social protection represents a persisting challenge.

Regarding progress in reaching the national targets under the Europe 2020 strategy, France has reached the targets for reducing early school leaving and increasing tertiary educational attainment. By contrast, additional efforts are needed to meet the targets on reducing poverty, investing in R&D, using renewable energy and improving energy efficiency.

France performs very well in terms of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (

). Progress can be observed in all SDG goals over the past five years and in particular in ‘Responsible consumption and production’ (SDG 13). At the same time, significant deviation can be observed in indicators linked to government debt (Partnership for the goals - SDG 17).

The main findings of the in-depth review contained in this report and the related policy challenges are as follows:

·While recent competitiveness developments are positive, several vulnerabilities remain. Cost-competitiveness has improved recently as France benefited from moderate growth in the cost of labour compared to most euro area or EU countries. This came about because of the combined effect of a moderate increase in real wages and low labour productivity growth. Recent reforms aimed to improve the business environment and improve business competitiveness, while further measures to increase the performance of the innovation ecosystem are warranted.

·No fiscal consolidation is planned in the short term. The structural deficit remains high and it will be difficult to reduce high government debt, which stands close to 100% of GDP, in the absence of fiscal consolidation. While the tax burden has been cut by almost one percentage point, cuts in government spending are proving much slower to accomplish. A quantification of overall savings and macroeconomic impacts of the Public Action 2022 is still missing.

·Private debt is high and on the rise.. The level of debt for both households and non-financial corporations is high and has continued increasing, contrary to other EU Member States with high levels of private debt. The French authorities will carry out an assessment of the rules adopted to mitigate risks to the financial system as a whole (macroprudential measures) in 2020.

·Although the situation is improving, the French labour market continues to face structural problems. These include persistent high unemployment, emerging skills mismatches and entrenched labour market segmentation. Recent reforms on vocational education and training aim at addressing these structural problems in the labour market. Their implementation requires close monitoring and assessment.

Other key structural issues analysed in this report, which point to challenges for France’s economy, are as follows:

·France is rolling out an investment plan to address its environmental sustainability challenges. The Great plan for investment supports moves towards a greener economy focusing on energy efficiency of buildings and incentives to switch to less polluting vehicles. However, based on current policies, France would miss its 2030 GHG reduction target for the non-ETS sectors by a significant margin, according to national projections. Simulations show that a budgetary-neutral public investment stimulus in France would increase domestic GPD and result in positive spillovers in the rest of the euro area.

·The Commission’s proposal for a Just Transition Mechanism under the next multi-annual financial framework for 2021-2027 includes a Just Transition Fund, a dedicated scheme under InvestEU, and a new government loan facility with the EIB. It is designed to ensure that the transition towards EU climate neutrality is fair by helping the most affected regions in France to address the social and economic consequences. Key priorities for support by the Just Transition Fund, set up as part of the Just Transition Mechanism, are identified in Annex D, building on the analysis of the transition challenges outlined in this report.

·The carbon tax increase has been suspended since 2019 following social unrest. Carefully designed supporting measures could facilitate the acceptance of future environmental taxes. In the context of social fairness, a citizens' climate convention has been given the mandate to define measures to achieve climate targets by spring 2020.

·Increased efforts are needed to cut greenhouse gas emissions in the residential sector. The residential sector is the second largest emitter of greenhouse gas emissions after transport. Public and private investment need to prioritise actions to make progress in improving energy efficiency of buildings as required by the 2019 climate and energy law, which plans to decrease the number of thermal sieves.

·The business environment is improving but difficulties remain for businesses wanting to scale up, which weighs on their capacity to export. High taxes on production also affect business competitiveness. France has a relatively low number of high-growth businesses. The PACTE law (Plan d’action pour la croissance et la transformation des entreprises) addresses some of the barriers to business creation and growth. France stands out for its level of taxes on production (3.2 % of GDP), one of the highest in the EU. Under the ‘Pacte Productif’, the French authorities announced a review of taxes on production and improvements for business competitiveness and environmental sustainability.

·The level of restrictive rules is higher in France than in other EU countries, particularly in some services, which could restrict competition. Redesigning requirements on the access and exercise of professions to stimulate innovation, competition and professional mobility, would have a positive economic impact. Additional restrictions have been imposed on retail services that could be detrimental to retailers and affect other businesses.

·Some groups experience more difficulties in accessing the labour market. In particular, the low-skilled people with a migrant background and non-EU born women have persistently lower employment rates. The more difficult integration on the labour market is reflected in a significantly higher risk of poverty.

·The French education system is experiencing persisting socioeconomic inequalities. According to the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment scores, the educational performance of 15-year olds in France is above the EU average. However, the link between socio-economic status and performance remained among the strongest in the EU, while having a migrant background also impacts negatively education outcomes. Comprehensive reforms are being implemented, including a number of measures to reduce inequalities starting from early childhood (lowering the age of compulsory education and halving class size in disadvantaged schools).

·Access to social housing remains a challenge. Although facing an increasing demand, the supply of new social housing continues to decline. Unmet demand for social housing is of particular concern for vulnerable groups such as single parent households that are more at risk of poverty. The ‘Housing First’ strategy rolled out by the government represents a positive step, yet remains limited in scope.

·Socio-economic gaps across French Regions are significant. Indicators point to a major economic gap between some regions (including the Ile-de-France region) and the rest of the country. The outermost regions experience specific vulnerabilities in education, healthcare and access to the labour market of vulnerable groups.

1.

Economic situation and outlook

GDP growth

GDP growth in France continued moderating in 2019. It decreased to 1.2% in 2019, after registering 1.7% in 2018 and 2.3% in 2017 (

). Private consumption picked up mildly, despite significant gains in purchasing power. The latter has been lifted by rising wages, falling unemployment and inflation and supportive fiscal measures. Corporate investment remained buoyant despite the slowdown of economic activity and public investment accelerated significantly, notably local investment. Following a downturn in 2018, household investment growth increased moderately in 2019. After a strong contribution to GDP growth in 2018, net exports slightly weighed on GDP growth in 2019. Import growth rose, while export growth decreased as external demand lost momentum.

|

Graph 1.1:Contributions to GDP growth (2012-2021)

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission, 2020a

|

GDP growth is set to decrease slightly in 2020, before recovering in 2021. Following a decrease at the end of 2019 due to temporary factors such as strikes against the pension reform, economic activity is set to rebound, supported by a resilient domestic demand. Private consumption growth is forecast to increase somewhat in 2020 and remain broadly stable in 2021, boosted by gains in purchasing power already registered in 2019. Higher consumer spending is expected to partially compensate for the slowdown in investment over the next few years. Corporate investment is set to decelerate, but to remain dynamic, supported by favourable financing conditions. Public investment is set to weaken due to local elections in the first quarter of 2020. In addition, net exports are set to weigh slightly on growth. GDP growth is expected to reach 1.1% in 2020 and 1.2% in 2021 (see Graph 1.1 and European Commission, 2020a).

Risks to economic growth are balanced. Negative risks mainly stem from the external side, while domestic risks are tilted to the upside. Persistent uncertainties on the international front (including trade policies and the threat that the U.S. may impose several duties on French exports) could weigh on French exports and investment (European Commission 2019a). Conversely, the expected rebound in the first half of 2020 could prove more robust with higher stockpiling. Private consumption could also be more dynamic than expected as the saving rate and consumer confidence remain high.

Potential growth

GDP growth is set to remain close to its potential, which is estimated at 1.1% in 2019. According to the Commission’s estimates, the output gap turned positive in 2018. It is set to slightly increase in 2019, reaching 0.7% of potential GDP, and remain broadly stable in 2020 and 2021.

Potential growth has been improving slowly since 2015. The growth rate of potential GDP decreased on average from 1.8% from 2000 to 2008 to just 1.0% between 2009 and 2019, reaching an all-time low of 0.8% in 2015. Since then, it has been gradually recovering and is expected to reach 1.3% in 2021. This slowdown has been observed in most major euro area economies. In France, as in other European economies, there has been a gradual decrease in the contribution of total factor productivity over the 2000s, combined with a drop in the contribution of capital accumulation following the 2008 financial crisis (see Graph 1.2). The contribution of total factor productivity has improved since 2010, but remains contained. Common global factors partly explain the slowdown in total factor productivity. For example, the increasing share of services in the economy or the slowdown in technological progress. However, France has room to increase its performance with respect to its specific factors to lift the contribution of total factor productivity in the medium-term. For example, this includes skills, competition or innovation (see Section 4.4.1). On capital accumulation, according to the Commission’s estimates, the investment ratio dropped from around 24% of potential output in 2008 to around 21% in 2015. A recovery has been observed since then, and now the investment ratio benefits from a sharp rise in investment over the past few years. The contribution of capital accumulation to potential growth remains nevertheless below pre-crisis levels.

|

Graph 1.2:Potential GDP growth breakdown

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission, 2019 autumn forecast

|

Inflation

Inflation is set to remain broadly stable in 2020 and 2021. Inflation (based on the HICP indicator) dropped to 1.3% in 2019, from 2.1% in 2018, due to lower oil prices and lower tax increases (

). It is forecast to decrease marginally to 1.2% in 2020, before going back to 1.3% 2021. Core inflation is set to increase slightly, in line with the services component.

Labour market

The labour market continues to improve, but challenges remain (see Section 4.3). The unemployment rate declined slowly from 10.4% in 2015 to 8.4% in Q4-2019 and is now more than 2 percentage points above the EU average (6.3% in Q4-2019). The employment rate stood at 71.4% in Q3-2019 and overall job creation remained dynamic in 2019. Job creation is subsequently forecast to slow down gradually, as the decline in GDP growth is set to spread to the labour market and the impact of some employment enhancing measures is set to fade away gradually (

). Overall, the labour market appears to be tightening. The gap between the unemployment rate and its structural level (NAWRU) has been gradually closing since 2015. Business surveys also report an increase in difficulties hiring workers since the start of the recovery (Dares, 2016). Rising unfilled vacancies (

) and shortages in some professions and sectors, despite a high level of unemployment, can also suggest a skills mismatch. Between 2015 and 2018, nominal (non-price adjusted) wages rose at a moderate pace while real (adjusted for price) wages grew broadly in line with productivity. Consistent with labour market tightening, the mild pick-up in nominal wage growth observed since 2015 is expected to continue in 2019 and is set to stabilise after that.

Regional disparities

Regional disparities have been steadily increasing in metropolitan France during the last decade. Two regions had a GDP per head above the EU average in 2017, namely Île-de-France at 177% of the EU average and Rhône-Alpes at 104% (

). At the other end of the spectrum, Picardie and Lorraine were at 75% of the EU average. In metropolitan France, divergences are growing between the capital and the poorest regions. The growth rate of GDP per head is the highest in the capital region, while it is generally lower for poorer regions. Disparities in GDP per head are linked to regional differences observed in the labour market (see Section 4.4.5).

In the outermost regions, several vulnerabilities persist. GDP per head as a percentage of the EU average is relatively lower in the outermost regions compared to metropolitan France. The unemployment rate is also much higher in those regions (see Section 4.4.5).

Social developments

While the French social protection system is overall effective in reducing poverty and inequality, the share of people at risk of poverty slightly increased in 2018 (see Section 4.3) (

). France is characterised by relatively low inequality in equivalised household disposable income, and a tax and benefit system effective in reducing poverty. In 2018, the share of income received by the top 20% of households was 4.2 times higher than that of the bottom 20%. This ratio has been gradually decreasing from the peak of 4.6 in 2011. The relative share of income of the top 20% of households in France is lower than the EU average of 5.2. Overall, the French social protection system appears to be effective in terms of reducing poverty and inequality in disposable income. Social transfers reduced the risk of poverty by 44.4% in 2018 (

), more than 10 percentage points above the EU average. The share of population at-risk-of-poverty and social exclusion (17.4%) also stood well below the EU average in 2018 (21.9%). However, contrary to the EU average and peer countries, the share of people at-risk-of-poverty slightly increased in 2018, driven by a marked rise in the rate of severe material deprivation rate (up by 0.6 percentage points compared to 2017, reaching 4.7% in 2018).

Competitiveness

Export market shares have broadly stabilised since 2013 after declining in the 2000s. Over the five years to 2018, export market shares remained flat in both the goods and services sectors. In the goods sector, the improvement in 2015 and 2016 was followed by a deterioration in 2017 and 2018. The evolution is more volatile in the services sector, with a deterioration in 2015 and 2017 followed by an improvement in 2016 and 2018. Moderate unit labour cost growth in aggregate since 2013 might have helped to stabilise the export market shares. Nevertheless, the relatively high level of taxes on production (see Section 4.1), the structure of the French production processes relying more on high unit labour cost sectors and the decline in average quality of exported goods might have limited the improvement of market shares. Overall, export market shares are forecast not to improve in the next few years.

|

Graph 1.3:Breakdown of unit labour cost rate of change

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission, 2019 autumn forecast

|

Growth in unit labour cost was moderate in the past few years. Nominal unit labour costs have grown by 2.4% over the three years to 2018, which is below the EU average. On a year-on-year basis, the increase in unit labour cost growth observed in 2018 is mostly explained by a decrease in labour productivity growth, which is set to continue decreasing in 2019 (see Graph 1.3). Despite a slowdown in economic activity, job creation remained dynamic in 2018 and 2019. Following a temporary decrease in 2019 due to a statistical artefact (

), growth in unit labour cost is forecast to recover in 2020 and 2021. In 2020, employers’ are forecast to benefit fully from additional reductions in employers’ social contributions for workers close to the minimum wage level. This is expected to help contain the growth in unit labour cost. In 2021, wages are set to accelerate slightly, as labour productivity gradually picks up.

|

Graph 1.4:Share of market services in export value added (2014)

|

|

|

|

Source: Commission's calculation based on World Input-Output Database

|

The important role services play in France continues to weigh on cost-competitiveness. The content of domestic services in total exports in France increased from 37% in 2000 to 40% in 2014. In 2014, it was higher than in major competitor countries (30%, 32% and 33% in Germany, Spain and Italy, respectively) (see Graph 1.4) (

). While the average labour costs converged in recent years with those of main competitors, labour costs in services remained among the highest in the EU. Taking into account both the fragmentation of production processes and the evolution of sectoral unit labour costs, Cézar and Cartellier (Banque de France, 2019a) show that domestic services sectors contribute particularly to the increase in the adjusted unit labour cost (

). In this regard, the evolution of domestic and foreign unit labour costs in the services sector had a higher impact on the labour costs of the aggregate exporting sector in France than in its neighbouring countries.

|

Graph 1.5:Export shares (% of national exports) by quality level

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|

On non-cost competitiveness, the composition of French exports shifted towards medium quality goods compared to the early 2000s. According to Burton and Kizior (forthcoming), in non-price component of exports (proxy for ‘quality’), France ranks 11th among 37 countries (OECD and EU countries), which suggests an overall medium-high quality of the French exports. The share of high quality products on total exports is lower than in Germany and Italy, but higher than in Spain. In contrast to these neighbouring countries, French export shares in high quality products decreased markedly between 2003 and 2016 (see Graph 1.5). Consequently, the share of middle and low quality products in total exports increased, underpinning exposure to relatively price elastic demand, and more intense competition, notably from emerging economies. Survey studies also support the perception of medium quality French products being often overpriced (Rexecode, 2019).

External position

The small current account deficit has been and is set to remain broadly stable. In 2018, net borrowing by corporations and the public sector was higher than households’ net lending. As a result, the current account posted a small deficit of -0.6% of GDP (

), broadly in line with its 2017 level (see Graph 1.6). According to balance of payments data, the trade deficit remained broadly stable in 2018, at around -1% of GDP (

). The trade deficit in goods deteriorated in 2018 due mainly to higher oil prices. This deterioration was compensated by an improvement of the trade surplus in services. According to the Commission 2019 autumn forecast, the overall trade deficit is set to improve slightly in 2019 on the back of lower oil prices. It is expected to deteriorate slightly in 2020 as imports are forecast to accelerate, and to remain stable in 2021. France has a significant primary income surplus, supported by direct investment revenues (see Section 4.4.1), which improved further in 2018. However, this improvement was offset by a deterioration in the secondary income deficit. In particular, the public administration current transfers deficit (including payments to the EU and to international organisations) worsened in 2018. The current account deficit is set to broadly follow the evolution of the trade deficit, and despite a temporary improvement in 2019, there should be little change going forward.

The net international investment position remains negative. It went from -16.6% of GDP in 2017 to -16.4% of GDP in 2018, benefiting from positive valuation effects linked to fluctuations in market prices and exchange rate (

). However, the readings of France’s net international investment position deteriorates, reaching -33% of GDP in 2018, if account is taken of those components that are considered more likely to default (

) (European Commission 2019b). Net direct investments account for most of the net international investment position on the asset side and increased markedly in 2018, driven by a significant growth in French foreign direct investments due to some major mergers and acquisitions. By contrast, portfolio investments deteriorated in 2018. General government still accounts for most of the negative net international investment position (almost -50% of GDP), while the private sector shows a strong position (close to 50% of GDP). Monetary and financial institutions, excluding the central bank, held a negative position in 2012, which has continued deteriorating since then.

|

Graph 1.6:Breakdown of the current account

|

|

|

|

Source: Eurostat (balance of payment)

|

France’s external position indicators stand below the levels suggested by the fundamentals, without raising prudential concerns. The current account and net international investment position remain below the levels predicted by fundamentals, which are surpluses of 0.3% of GDP (

) and 6% of GDP, respectively. However according to the Commission’s estimates, the current account level in 2018 is close to the cyclically-adjusted one and seems broadly in line to stabilise the net international investment position at its current level over the next 10 years. Furthermore, the net international investment position level does not raise prudential concerns (

).

Private debt

Private debt continued to increase in 2018, reaching 148.9% of GDP (

). In the current environment of low interest rates, both households and non-financial corporations have been contributing to the increasing private debt ratio in France. In particular, non-financial corporations have been leveraging further, namely from 86.9% of GDP in 2017 to 88.9% in 2018. Households’ debt also continued rising (at one of the highest rates in the EU), reaching 60% of GDP in 2018 from 58.5% in 2017. By contrast, private debt in the euro area as a whole has been falling in every year since 2009.

|

Graph 1.7:Non-financial corporation consolidated debt

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission, Eurostat

|

Non-financial corporations have been leveraging further despite recording a debt ratio already above the level suggested by the country’s fundamentals. Among the countries with a positive non-financial corporations debt gap relative to a prudent indicative threshold, France is one of the few cases where deleveraging did not take place in 2018. The debt of non-financial corporations reached 88.9% of GDP in 2018, which according to Commission estimates is 22 percentage points above what fundamentals would suggest. It is also above a level that justifies prudential concerns (see Graph 1.7) (

). Positive net credit flows continued increasing in 2019. However, the share of non-financial corporations’ interest payments on their total value added continued to decline in 2018 to 5.1%. This was due to low and falling interest rates, reaching their lowest level in decades despite being 78% higher than in the euro area (see Graph 1.8). The proportion of short-term debt on total debt in non-financial corporations has decreased slowly since the crisis, from around 34% to around 30% in 2018. This acts as a mitigating risk factor. To reduce the risks associated with high private debt of non-financial corporations, the High Council for Financial Stability (Haut Conseil de Stabilité Financière) introduced macroprudential instruments (see Section 4.2).

Household debt continued rising but the level is still in line with the fundamentals. Household debt-to-GDP has been increasing steadily over the last decade and is now above the prudential thresholds estimated by the Commission (

). However, at 60% of GDP, the level of household debt in 2018 is estimated to be close to the fundamentals according to the Commission’s estimates. Household debt has increased more than the fundamentals-based benchmark, and it will surpass it if trends do not change. Consumer spending loans marginally increased in 2018 up to 7.3% of GDP, but the mortgage stock in percentage of GDP increased by 1.6 percentage points in 2018, reaching 44.1% of GDP in 2018. While French households’ interest payments, as a share of their gross disposable income, is at historical lows and in line with other euro area countries, the share of household income devoted to debt repayment has continued increasing. For example, the share of households with a debt-service-to-income ratio above 33% has increased by 5 percentage points since 2015 (Haut Conseil de Stabilité Financière, 2019a). Supporting this aggregate finding, the households credit observatory (Observatoire des Crédits aux Ménages) noted that in 2018, out of all the borrowers, 50% of respondents classified the repayment of their debt as a high burden despite the cut in interest rates (the burden remains nevertheless bearable for the majority of them).

|

Graph 1.8:Interest burden evolution

|

|

|

|

Source: Eurostat

|

Housing

While real house price growth has been very contained in France since 2011, some indicators continue to suggest risks of overvaluation. This is due to the significant growth in the 2000s, which has yet to be undone (see Graph 1.9). The European Systemic Risk Board has identified medium-term vulnerabilities in the housing market in France as a source of systemic risk to financial stability, which could have negative effects on the real economy (European Systemic Risk Board, 2019). However, the High Council for Financial Stability has not found evidence of possible risks associated with a potential fall in property prices (Haut Conseil de Stabilité financière, 2019a). The reason being that 94.6% of outstanding loans at the end of 2018 are set at a fixed interest rate (Autorité de contrôle prudentiel, 2018), which limits the impact of a potential rise in interest rates. Two additional sources that limit potential vulnerabilities from macroeconomic shocks are (i) the high social protection in France, and (ii) the double-selection procedure of borrowers, where these are evaluated by lenders as well as mutual guarantee societies. Despite this, the High Council for Financial Stability pointed out that credit standards have loosened across the board, with increasing maturities, loan-to-value and debt service-to-income ratios (Haut Conseil de Stabilité Financière, 2019a and 2019b). French authorities have taken several macroprudential measures to address the growing vulnerabilities, including in the residential real estate market (see Section 4.2).

|

Graph 1.9:Housing market - Overvaluation gaps

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|

Public finances

The public deficit dropped to 2.5% of GDP in 2018; looking forward, little structural improvement is envisaged. According to the Commission 2019 autumn forecast, the general government deficit is set to rise to 3.1% of GDP in 2019. This is due to the one-off deficit-increasing impact of 0.9% of GDP mainly stemming from the replacement of the tax credit for employment and competitiveness (Crédit d’Impôt pour la Compétitivité et l’Emploi) by a permanent cut in social contributions. As this effect fades away in 2020, the general government deficit is forecast to decline to 2.2% of GDP. However, the structural deficit is not expected to register any material improvement in 2019 and 2020. In 2020, the deficit-increasing measures adopted after the Broad National Debate (Grand débat national) (see Section 4.1) are set to be partially offset mainly by the projected decline in interest payments and by postponing the cut in the corporate income tax rate for large companies. At unchanged policies, the deficit is projected to remain at 2.2% of GDP in 2021.

The public debt-to-GDP ratio will increase further, to about 99% of GDP, by 2021. The public debt-to-GDP ratio has hovered around 98.4% in 2017 and 2018. However, according to the Commission 2019 autumn forecast, it is expected to increase by 0.5 percentage points of GDP in 2019. It is then projected to rise further, to 99.2% in 2021, due to persistently high structural deficits (see Section 4.1).

Sustainable Development Goals

Overall, France performs very well in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. According to Eurostat’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) indicators (see Annex E), France performs better than the EU average in nearly all the indicators related to inequalities for SDG 1 - No poverty, SDG 5 - Gender equality, and SDG 10 - Reduced inequalities. France has been making progress in all the goals over the past five years. In particular, ‘Responsible consumption and production’ (SDG 12) and ‘Peace and justice’ (SDG 16). However, basic education indicators (Underachievement in reading, maths and science, SDG 4 - Quality education) are on a persistent deviation (short and long term). Lower performances can also be observed in SDG 8 - Decent Work and Economic Growth and SDG 17 - Partnerships for the goals.

|

|

|

Table 1.1:Key economic and financial indicators

|

|

|

|

Source: Eurostat and ECB as of 4-2-2020, where available; European Commission for forecast figures (Winter forecast 2020 for real GDP and HICP, Autumn forecast 2019 otherwise)

|

|

|

2.

Progress with country-specific recommendations

Since the start of the European Semester in 2011, 59% of all country-specific recommendations (CSRs) addressed to France have recorded at least “some progress” while 27% of these CSRs recorded “limited progress” or “no progress” (see Graph 2.1). Major reforms have been adopted in the field of vocational education and the training system, the functioning of the labour market and business environment.

|

Graph 2.1:Overall multiannual implementation of 2011-2019 CSRs to date

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|

On public finances, despite the reduction over the years, in a low interest rates environment, public deficit remains high and public debt keeps on the rise. Efforts have been made to control public spending dynamics at all levels of public administration. However, significant tax cuts carried out in parallel have hampered a faster fiscal consolidation, which is now on the back burner until the end of the presidential term and beyond. Although falling, in 2018, the level of general government expenditure, at 56% of GDP, remained the highest in the euro area and the EU as a whole (47% and 45.8%, respectively). So far, the contribution of the spending review in the framework of the broader Public action 2022 programme lacks proper quantification and as such its macroeconomic impact cannot be assessed (see Section 4.1). In turn, the reform of the pension system, originally envisaged for 2019, has been put off and is now planned for adoption by the end of 2020. According to the information available, the main objectives of the reform appear in line with the CSRs addressed to France.

Action has been taken to improve the functioning of the labour market and reform of the vocational education and training system. The functioning of the labour market has been reformed in 2016 and 2017 to incentivise hiring on permanent contracts and revise collective bargaining and social dialogue. An important reform of the vocational education and training system has been implemented since 2018. It addresses major challenges such as the need to increase access to training for low skilled and improve the labour market relevance and quality provided by the vocational education and training system. However, the most vulnerable categories of workers (young, low-qualified workers, and people with a migrant background) are at a disadvantage in terms of labour market access. Specific initiatives to increase their employment opportunities are being implemented while persisting difficulties and inequalities continue to affect people with a migrant background (See Section 4.3).

Efforts to improve the business environment are mixed. France has implemented a range of reforms covering measures to facilitate firms’ growth (PACTE Law in 2019), simplification of the taxation system (ESSOC Law in 2018) and reducing restrictions in the services sector (‘Macron Law’ in 2015). However, the level of regulatory restrictions in services remains high and barriers to entry (see Section 4.4) leading to low competition persist. In addition, limited progress has been made to address the high level of taxes on production (see Section 4.1) weighing on companies.

There is also room to improve investment-related economic policy. France has made some progressed in focusing investment to ensure the energy transition and to improve its digital infrastructure. However, there is a need to simplify the overall research and innovation ecosystem. Recent evaluations of the R&D tax incentive (CIR) point to a limited impact of the instrument on innovation and productivity (see Section 4.4). The assessment of this CSR does not take into account the contribution of the EU 2021-2027 cohesion policy funds ().

In 2019, France has made some progress (

) in addressing the country specific recommendations (see Table 2.1). Substantial progress has been made in implementing the measures to foster the growth of firms. Some progress has been made in addressing skills shortages and mismatches, focusing investment to ensure the energy transition, improving the digital infrastructure and continuing the simplification of the tax system. Limited progress has been made in reforming the pension system, fostering integration on the labour market and ensuring equal opportunities, improving the research and innovation performance and reducing regulatory restrictions. There has been no progress in further specifying and implementing concrete measures of Public action 2022 programme.

Upon request from a Member State, the Commission can provide tailor-made expertise via the Structural Reform Support Programme (SRSP) to help design and implement growth-enhancing reforms. Since 2017, such support is being provided to France through the progressive deployment of seven projects. The Commission is providing the authorities with support to foster the development of a strategic department, to improve digital interoperability in pensions’ payments, to design and evaluate innovative interventions for specific diseases (HIV and hepatitis C), to facilitate the implementation of France's housing policy and to raise awareness about the issue of financial mis-selling.

|

|

|

Table 2.1:Assessment of 2019 CSR implementation (*)

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

(*) The assessment of CSR 3 does not take into account the contribution of the EU 2021-2027 cohesion policy funds. The regulatory framework underpinning the programming of the 2021-2027 EU cohesion policy funds has not yet been adopted by the co-legislators, pending inter alia an agreement on the multiannual financial framework (MFF)

|

|

|

|

Box 2.1: EU funds and programmes to address structural challenges and to foster growth and competitiveness in France

France is benefiting from EU support. The financial allocation from the EU Cohesion policy funds (

I

) for France amounts to €28.5 billion in the current Multiannual Financial Framework, equivalent to around 0.2% of the GDP annually. By the end of 2019, some €25.9 billion (around 91% of the total amount planned) were allocated to specific projects, while €11.9 billion were reported as spent by the selected projects (

II

), showing a level of implementation above the EU average.

While bringing about a more harmonious development through reducing economic, social and territorial disparities, EU Cohesion policy funding also supports structural challenges in France. The Cohesion policy programmes have allocated €4 billion for smart growth, €3.5 billion for sustainable growth and sustainable transport and €6.7 billion for inclusive growth. In 2019, following a performance review (

III

) €1.4 billon have been made available for France within performing priorities.

EU Cohesion policy funding is contributing to transformations of the French economy by promoting growth and employment via investments, among others, in research, technological development and innovation, competitiveness of enterprises, sustainable transport, employment, labour mobility, skills and social inclusion. By 2019, investments driven by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) have already led to connect to high speed broadband more than one million households, over 1,600 new researchers have been recruited, and support was already decided for 162,000 enterprises including 48,500 start-ups, generating 36,880 new jobs. The European Social Fund (ESF) supported the labour market integration of job seekers including through access to training and counselling. By 2019, the social inclusion of 900 000 persons was supported. European structural and investment (ESI) funds contributed to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by four million tons of CO2. As an example, the COMPETITIV´eko project is promoting cross-border cooperation and knowledge exchange between SMEs, business clusters, technological centres and economic development agencies in the Basque Country and Navarre in Spain, and Nouvelle Aquitaine in France. Aimed at boosting the competitiveness of companies with few resources, it focuses on areas within the regions’ smart specialisation strategies. This will enable each region to develop its own competitive advantages where common interests exist.

Agricultural and fisheries funds and other EU programmes also contribute to addressing investment needs. The European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development support for €16.6 billon including national co-financing, mainly to support agri-environmental and climate type of measures, which aim to improve biodiversity, water quality and soil protection. The European Maritime and Fisheries Fund contributed to the tune of €774 million. France also benefits from other programmes, such as the Connecting Europe Facility, which allocated EU funding of €1.9 billion to specific projects on strategic transport networks, and Horizon 2020, which allocated €5.1 billion (benefiting to 1,129 SMEs for a total of €719 million).

EU funding contributes to mobilise private investment. By allocating about €650 million as loans, guarantees and equity, European and Structural Investment Funds supported programmes alone mobilised additional capital (

IV

). These are expected to leverage additional private investment of about €890 million.

EU funds already invest in line with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In France European Structural and Investment Funds support 14 out of the 17 SDGs and up to 98% of the spending is contributing to these goals.

|

3.

Summary of the main findings from the MIP in-depth review

The 2020 Alert Mechanism report concluded that a new in-depth review should be carried out for France to assess the persistence or unwinding of the imbalances (European Commission, 2019b). In February 2019, France was identified as having macroeconomic imbalances (European Commission, 2019). In particular, these related to high public debt and weak competitiveness dynamics, in a context of low productivity growth. This chapter summarises the findings of the analyses in the context of the macroeconomic imbalance procedure (MIP) in-depth review that is contained in various sections in this report* (

).

Imbalances and their gravity

Developments on French competitiveness continue to be mixed. In recent years, export market shares remained flat after years of losses. Comparing export performance against other advanced economies (

), France’s total export market shares fell slightly over the last five years. The current account balance has been recording only small deficits for a number of years, yet remaining below values implied by fundamentals, which would suggest a marginally positive reading. The net international investment position (NIIP) remained broadly constant, reaching -16.4% of GDP in 2018, when fundamentals would point to something slightly positive.

General government debt is high. In 2018, the French general government debt-to-GDP ratio remained stable at a high level, namely at 98.4% of GDP. However, according to the Commission 2019 autumn forecast, France’s public debt is set to have risen to almost 99% of GDP in 2019 and to increase further in the next two years. This means that the recent economic expansion has not been accompanied by fiscal consolidation.

Private debt is also high and increasing more or less continuously since the early 2000s. In particular, it reached almost 149% of GDP in 2018. Both households and non-financial corporations contributed to this ratio.

Competitiveness and productivity weight on France's economic growth, which in turns impacts debt burdens and deleveraging. Cost competitiveness has been a concern and non-cost competitiveness has also been dampened. Low productivity growth has also affected France, while the relevance of exports to GDP increased less than in the rest of the euro area.

The large size of the French economy can be a source of cross border spillovers to other EU Member States. France is an important trade and financial partner for many EU Member States and in particular to neighbouring countries (see Table 3.1). Box 3.1 provides a quantitative estimate of how an increase of public investment in France can have positive effects on its own domestic GDP and relevant spillovers to other Member States.

Evolution, prospects and policy responses

Fiscal consolidation is on hold. The 2020 budgetary plan does not outline any fiscal consolidation progress for 2020. The reform to unify the different pension schemes currently co-existing, originally announced for 2019, has been postponed, and the impact of actions aimed at achieving meaningful expenditure savings and efficiency gains across all sub-sectors of government under the Public action 2022 programme, have not yet been specified. Macro prudential instruments to limit banks’ exposure to highly indebted large non-financial corporations and to increase banks’ capital buffers to make them more resilient to periods of stress have been introduced.

Cost competitiveness has remained broadly stable over the past year, although some indicators measuring the evolution over a longer period have to be closely monitored. In 2018 alone, unit labour costs increased by 1%, resulting from the combined effect of a moderate increase in real wages and the low labour productivity growth. Growth in nominal unit labour costs, based on the three-year indicator up to 2018 was more contained than in the rest of the EU average despite having accelerated slightly, reaching 2.4%. The real effective exchange rate (REER) appreciated by 4.5% between 2015 and 2018, reflecting much of the euro appreciation after the marked 2015 depreciation. However, in 2019 some nominal depreciation was again observed (as in other euro area countries). In terms of non-price competitiveness, while French exports of goods are overall of medium-high quality, France continued to maintain the highest quality in the sectors in which it specialises, such as aeronautics, cosmetics and beverages.

Several initiatives have been adopted to improve the business environment. The PACTE law (Loi relative à la croissance et la transformation des entreprises) was adopted in May 2019 to foster the growth of firms. Measures were announced in some specific services sectors to increase competition and moderate prices. The services in which measures have been already adopted include the sale of automotive spare parts, driving schools and health insurance. Efforts to streamline the tax system are ongoing (Loi pour un Etat au service d’une société de confiance, ESSOC’). In terms of innovation performance, diagnostics of the R&D tax credit (Crédit Impot Recherche) were proposed but they need to be extended to include the macroeconomic impact. On digitalisation, the French government unlocked €3.3 bn to boost additional private investment in rolling out ultra-fast broadband across the country.

|

|

|

Table 3.1:Outward spill-over heat map

|

|

|

|

Source: IMF, OECD, TiVa, BIS and Commission services

|

|

|

Adopted and announced labour market reforms are going in the right direction, but their benefits will take time to fully materialise. Reforms aim to increase the labour participation of specific groups and to increase the overall skills of the labour force. In this regard, French workers earning close to the minimum wage have been supported by a significant increase in their in-work benefits (prime d’activité). The unemployment benefit reform, implemented since November 2019, modifies eligibility criteria and introduces specific sectoral incentives and disincentives for employers if they use short-term contracts. To improve the efficiency of social benefits, the government is planning to merge different ones into a universal activity income (Revenu universel d’activité). The link between training, labour market and needs of firms has also been improved, with firms being able to have their own learning centres for apprenticeships (See Section 4.3).

Overall assessment

France is characterised by high indebtedness and still weak, although stable competitiveness, in a context of low productivity growth. Despite stable export market shares and a continuing small current account deficit, low productivity growth still weighs on French competitiveness. France’s general government debt remains high and is set to rise somewhat further in the following two years. Risks stemming from high public debt are compounded by high and increasing private debt.

France has introduced ambitious reforms while public expenditure remains high. France has taken further ambitious measures, notably in the areas of business environment, labour market and apprenticeship and vocational education. These reforms will take time to fully materialise and will require close monitoring. As for public finances, fiscal consolidation efforts have been put on hold and the current budgetary strategy does not guarantee a reduction of the high public debt.

|

|

|

Table 3.2:MIP Assessment Matrix (*)

|

|

|

|

|

|

(Continued on the next page)

|

|

Table (continued)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|

|

|

|

Box 3.2: Euro-area spillovers

Simulations with the European Commission’s QUEST model (

V

) illustrate the size of the potential domestic impact and potential spillovers to other euro-area countries. Following the 2019 Country-specific recommendations on investment-related policy measures, the Commission QUEST model is used for a standardised simulation exercise to assess the potential theoretical domestic and cross-border impact resulting from a public investment package. The standardised scenario displayed in this box is based on an increase in the public investment level in France by 1% of current GDP over 10 years(

VI

) under the working hypothesis that this increase in public investment is financed by an increase in the consumption tax by 1% of current GDP, assuming ex-ante budget neutrality. Given that public investment has positive output effects, the ex-ante budget neutrality imposed in the simulation turns into an ex-post improvement in the government primary balance, mainly linked to positive tax base effects. Monetary policy is assumed to remain constrained at the zero bound for 6 quarters, after which the constraint is phased out gradually.

A sustained increase in public investment would have a positive domestic impact on GDP and cross-border spillovers. The simulation suggests a positive impact on the level of French real GDP of around 0.6% in the first year, increasing gradually to reach a cumulative impact of 1.6% after 10 years (see table below). This positive impact originates from the positive effect of public investment on productivity. In addition, the expected impact on the real GDP of the rest of the euro area would approximately amount to 0.3%, representing an initial spillover of half the domestic impact. This spillover effect is driven by an increased external demand and by higher domestic demand originating from the temporary decline in the real interest rate.(

VII

) The GDP spillover to the rest of the euro area weakens once the real interest effect has vanished, but it remains positive also in the longer term. While this standardised exercise assumes a domestic impact of a national public investment program, the overall impact on the euro area could be potentially higher in the case of a coordinated investment program at the euro area level.

Note: Results in % or pps (Trade balance and government debt) deviation from baseline.

Source: European Commission

|

4.

Reform priorities

4.1.Public finances and taxation*

Deficit developments

After a temporary rebound in 2019, the French general government deficit is set to stabilise at 2.2% of GDP until 2021. In 2018, the general government deficit decreased to 2.5% of GDP. However, the structural deficit remained high (at 2.7% of GDP), confirming no structural improvement since 2015 and considerably far from France’s medium-term objective of -0.4% of GDP (see Graph 4.1.1). The headline deficit is set to pick up to 3.1% of GDP in 2019. The increase above the 3% threshold is however small and temporary, due to the one-off impact of the transformation of the tax credit for employment and competitiveness (CICE) into a permanent reduction in employers’ social contributions, with no impact on the structural deficit. According to the Commission 2019 autumn forecast, public deficit is projected to decline to 2.2% of GDP in 2020, mainly due to the fading of this one-off impact, and to remain at that level in 2021.

|

Graph 4.1.1:Fiscal effort and public debt

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission. Ameco database

|

Fiscal consolidation has been put on hold and public debt remains on the rise. The consolidation strategy over the current presidential term was outlined in the multiannual public finances programming law for 2018-2022. However, since its initial adoption in 2018, consolidation targets have been progressively back-loaded. While the objective to reduce the tax burden by one percentage point by the end of the presidential term is almost already achieved, reducing government expenditure is proving much slower. As a result, the original objectives of cutting the deficit by more than 2 percentage points and reducing debt by more than 5 percentage points by 2022 have been considerably scaled down. The 2020 draft budgetary plan does not outline any progress in terms of fiscal consolidation in 2020. Moreover, the underlying reduction of the expenditure-to-GDP ratio is, largely, due to the planned decline in public debt servicing costs. This is broadly confirmed by the Commission 2019 autumn forecast, which projects only a slight improvement in the structural balance, of 0.1 pps., in 2020 (

), and no structural effort in 2021. This is insufficient to put public debt on a steady downward trend.

New measures, mainly tax cuts, aimed at further enhancing household’s purchasing power are envisaged for 2020 (see Box 4.1.1). The measures adopted at the end of 2018 in response to the ‘Gilets jaunes’ movement, aimed to improve households’ purchasing power, entailed a net deficit-increasing impact of around 0.3% of GDP in 2019. Additional measures taking effect in 2020 were adopted in response to this movement and following the conclusion of the broad national debate (Grand Débat National) in April 2019. These include a permanent €5 bn reduction in personal income tax (0.2% of GDP), reviewing the indexation of pensions below €2,000 per month, and the increase in minimum pensions (together reaching €1.5 bn, or 0.1% of GDP).

The fiscal strategy on the spending side relies on control of public expenditure dynamics and growth-friendly spending programmes. After the unprecedented decline in real terms by 0.3 pps.in 2018, according to the 2020 draft budgetary plan, public expenditure in nominal terms, net of tax credits, is set to rise by 2.1% and 1.8% in 2019 and 2020, respectively. These imply increases in real terms of 1.1% and 0.6% in the same years. The government has given high priority to programmes aimed to promote long-term growth. Under the current five-year great investment plan (Grand Plan d'Investissement), the priorities are to (i) accelerate ecological transition, (ii) create a skill-based society, (iii) foster competitiveness and innovation, and (iv) achieve the digital transformation of the public sector (See Section 4.4).

Social protection and healthcare represent more than half of total public expenditure. At 56% in 2018, the ratio of public expenditure over GDP in France remains the highest in the EU. Social protection remains the biggest ticket item, accounting for almost 43% of total government expenditure in 2018. Expenditure on healthcare and education, key to increase human capital, represented 14.5% and 9.1% of total public spending, respectively. In turn, expenditure on general public services and on economic affairs amounted to 11.0% and 10.2% of the total, respectively. The latter includes, among others, expenditure on transport, energy, on general economic, commercial and labour affairs and on research and development.

Debt sustainability analysis and fiscal risks (

)

Despite general government debt stabilising in 2018, it is projected to rise further until 2021. The public debt ratio, at 98.4% of GDP, remained broadly stable in 2018 compared with 2017. However, according to the Commission 2019 autumn forecast, the public debt ratio is set to rise by 0.5 pps. in 2019. In 2020, public debt is forecast to remain at 98.9% of GDP, before rising again to 99.2% in 2021. Upward revisions to the deficit, also due to the measures put forward by the government in response to the ‘Gilets jaunes’ movement at the end of 2018 and in April 2019 after the broad national debate (Grand Débat National) entailed deficit-increasing effects for 2019 and 2020 that have prevented public debt from entering a declining trend. Therefore, public debt is set to remain at high levels, widening the gap with the euro area, where overall public debt is projected to decline by almost 6 pps to 84.1% of GDP between 2018 and 2021 (see Graph 4.1.2). Such a divergent trend is explained by the persistent French primary deficits projected over the forecast horizon, as opposed to primary surpluses for the euro area average.

|

Graph 4.1.2:Public debt in France and in the euro area

|

|

|

|

Source: Ameco database, European Commission 2019 autumn forecast.

|

In spite of the high public debt ratio, no material short-term sustainability challenges are observed. Short-term sustainability risks are assessed by the indicator S0 (

). For France, the overall S0 indicator flags no significant risk. However, the short-term fiscal sub-index indicates high risk, with some increasing vulnerabilities with respect to previous years, linked to the persistent, relatively high cyclically-adjusted deficits and the increase of already high public debt. In any case, the overall absence of any material short-term risk remains confirmed by the ‘AA stable’ rating given by the three major rating agencies to French government debt. Short-term risks are mitigated by the diversification of the investors’ base and the long average maturity of total outstanding debt, that has increased to around 8.2 years in 2019. In turn, the share of non-resident holders of government debt securities, which is evenly distributed between euro area and non-euro area residents, has slightly increased to around 55% in 2019.

Medium-term sustainability risks remain high. According to the debt sustainability analysis baseline scenario, at unchanged policies, the public debt ratio is projected to fall by some 2 pps. until 2030, the last projection year, when public debt would stand at 96.8% of GDP. This decline is due to an increasingly larger debt-reducing snowball effect (e.g. the difference between the implicit interest rate on government debt and the nominal growth rate of the economy) that more than offsets the projected high primary deficits, aggravated by the increase in age-related expenditure over the projection period (see Annex B). The S1 sustainability indicator (

), which measures sustainability risks over the medium term, indicates a high medium-term risk, mainly due to insufficient fiscal effort to reduce public debt to 60% of GDP.

An improvement in the structural primary balance is required to progressively reduce public debt. The S1 sustainability indicator shows a sustainability gap of 3.9 pps. of GDP. Most of the required adjustment (3.4 pps.) relative to the baseline scenario is attributable to the debt ratio’s distance from the 60% reference value and 0.4 pps. to the projected increase in age-related public spending. The sustainability gap has reduced by more than 1 point with respect to 2019 spring’s projections due to more favourable interest rate assumptions, which more than offset the effect from lower projected nominal growth and higher primary deficits. Under these conditions, a marginal improvement in the structural primary balance is enough to stabilise the public debt ratio. However, public debt projections are particularly sensitive to interest rate and growth assumptions. Adverse assumptions on these two variables would lead to significantly higher debt ratios after 10 years (see Graph 4.1.3).

|

Graph 4.1.3:Public debt projections in France

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission. 2019 DSM

|

France is deemed to be at medium fiscal sustainability risk when assessed over the next 50 years. The long-term fiscal sustainability indicator S2 (

) shows that an improvement of the structural primary balance of only 0.2% of GDP would be required to stabilise the debt-to-GDP ratio over the long-term. This low value is due to the favourable demographics that help mitigate sustainability risks. Age-related expenditure is projected to decrease by 1.9 pps. of GDP over the next 50 years. This is due to the projected decline in public pension expenditure by 2.2 pps. of GDP, whereas healthcare and long-term care spending are projected to rise only moderately, by 0.3 pps. and 0.5 pps. of GDP, respectively. The projected healthcare expenditure stands below the EU average increase of 0.9 pps. of GDP. Despite the low S2 indicator, the implied fiscal adjustment might lead to debt stabilising at high levels, for which this indicator should be taken with some caution for high-debt countries. Moreover, the vulnerabilities linked to the high debt burden as captured by the debt sustainability risk assessment suggest that French public debt might be facing a medium sustainability risk over the long term. More adverse scenarios involving more dynamic healthcare and long-term care spending would imply a significant increase in sustainability gaps.

The healthcare reform is not projected to entail any material impact on overall fiscal sustainability. The 2022 my health plan (Ma Santé 2022) to improve access to healthcare will require €3 bn of investment on restructuring of care, digital health, training and hospital investment, accompanied by an increase in current expenditure growth standard ONDAM (Objectif National de Dépenses d'Assurance Maladie) from the originally planned 2.3% to 2.5% in 2019. The impact on the fiscal sustainability of the French health system is likely to be small, around one point of GDP total higher expenditure by 2070. However, given the scale of investment, the impact on current healthcare expenditure might be larger than planned.

Pensions

The pension reform, originally announced for 2019, has been put off and is expected to be adopted in 2020. This reform intends to introduce a universal points-based system, replacing the current 42 co-existing pension regimes. According to announcements, the new system aims to calculate the pension rights over the whole career for all categories of workers. It also aims to introduce a single definition for the labour revenues to be used to calculate pension contributions. This would include bonuses for the public sector and the special regimes, which should be gradually phased out. A minimum pension would be guaranteed at 85% of the minimum wage (Salaire minimum interprofessionnel de croissance, SMIC) for those with full careers, currently at around €1,000. Solidarity points are planned to compensate for certain situations such as sickness, unemployment or maternity, among others. While the minimum legal retirement age is set to remain at 62, the new system could include incentives to work longer. New entrants into the labour market in 2022 would contribute directly to the new system and the first generation concerned by the reform should be those born in 1975. For those already in the current system, only the years contributed after 2025 would be calculated under the new system. The draft law was sent to parliament on the 24 of January. Its adoption is planned for 2020 for implementation as of 1 January 2022.

Social partners would be responsible for guaranteeing the financial equilibrium of the pension system. Following some social unrest in response to the reform, the government engaged in new broad consultations with social partners and stakeholders to gather the broadest consensus possible. According to announcements, the return to balance of the pension system should be reached in 2027. To this end, social partners have been entrusted to propose a path back to balance in spring 2020. Under the new pension system, social partners, subject to parliamentary control, would be in charge of evaluating the value of the points to calculate pension benefits and, more generally, of guaranteeing the financial balance of the system. The new indexation framework, possibly linked to wage developments, could be more favourable to pensioners than the current one linked to inflation.

Healthcare

There is room for efficiency gains in the healthcare sector. Traditional inefficiencies in the French health system, such as concentration on hospital care and a low share of generics in pharmaceutical sales, have been improving in recent years, but still lags behind most Member States. Total spending was estimated at 11.3% of GDP in 2017, the highest in the EU along with Germany. Still, in terms of per capita spending, adjusted for differences in purchasing power, France stands 6th highest in the EU. Even if the annual objective for spending growth in healthcare (Objectif National de Dépenses d’Assurance Maladie, ONDAM) has been met since 2010, the ONDAM target was increased three times since 2017 and made less demanding for 2018-2020. In particular, the target was set at 2.1%, 2.3% and 2.5% in 2017, 2018 and 2019, respectively. The ONDAM is set at 2.45% for 2020, compared to an initial target of 2.3% (

). The share of healthcare prevention expenditure has traditionally been among the lowest in the EU (1.86% in France in 2017 compared with 3.1% in the EU).

France is experimenting new payment methods for more efficient and effective primary and hospital healthcare. The new methods entail greater financial incentives for quality and care coordination between the providers, giving less weight to activity-based payments and discouraging an overprovision of care. An extension of the new methods is foreseen from 2020 onwards.

Fiscal framework