EUROPEAN COMMISSION

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Brussels, 4.1.2017

SWD(2016) 451 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

on the implementation of Directive 2010/53/EU

Accompanying the document

REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS

on the implementation of Directive 2010/53/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 July 2010 on standards of quality and safety of human organs intended for transplantation

{COM(2016) 809 final}

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

on the implementation of Directive 2010/53/EU on standards of quality and safety of human organs intended for transplantation

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Verification of the transposition of Directive 2010/53/EU

3. Implementation of Directive 2010/53/EU

3.1. Identification of and tasks of the competent authorities and overall set-up

3.1.1. Organisational set-up

3.1.2. The national level

3.1.3. Combination of levels: regional, national and supra-national

3.1.4. Involvement of regional authorities and nature of their tasks

3.1.5. Involvement of European Organ Exchange Organisations and nature of their tasks

3.1.6. Conclusion on the overall set-up of authorities and tasks under Article 17

3.2. Organ donation and procurement

3.2.1. Authorisation of procurement organisations

3.2.2. Procurement teams coming from abroad to procure organs

3.2.3. Framework for ensuring procurement organisations' compliance with the Directive

3.2.4. Personnel involved in the procurement

3.2.5. Consent system for organ donation

3.2 6. The selection and protection of living donors

3.2 7. The follow-up of transplanted patients

3.2.8. Other key principles governing organ donation

3.3. Transport of organs intended for transplantation

3.4. Authorisation of transplantation centres and qualification of personnel

3.4.1. Authorisation of transplantation centres

3.4.2. Framework for ensuring compliance with the Directive in transplantation centres

3.4.3. Personnel involved in transplantation activities

3.5. Framework for quality and safety

3.6. General points

3.6.1. Legal framework for non-compliance with the Directive (penalties)

3.6.2 Organ trafficking

4. Conclusion

Annex

ANNEX 1:

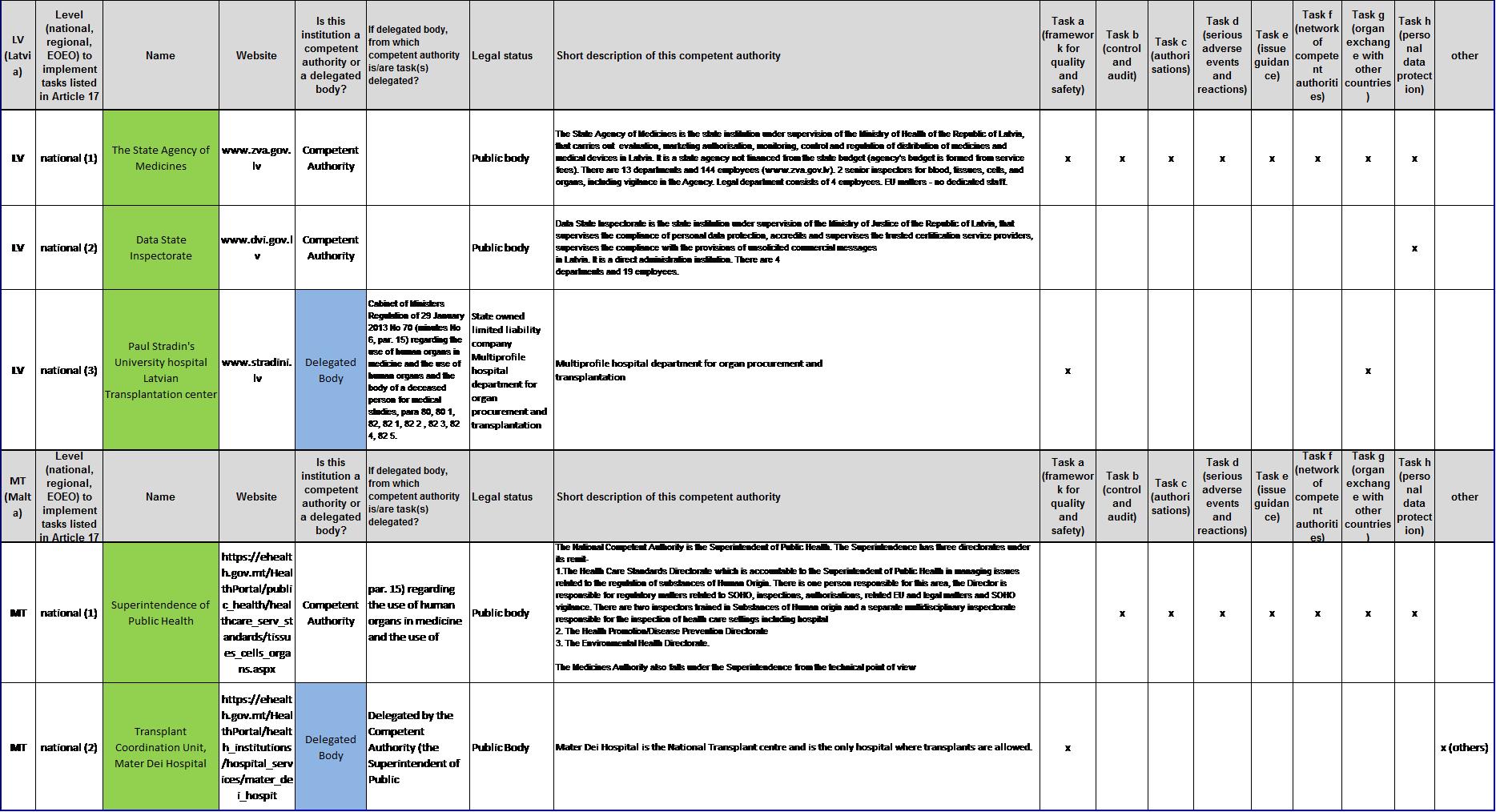

List of competent authorities and corresponding tasks under Article 17

List of figures

FIGURE 1:

Transplants and donors in 2014 in the European Union and Norway

FIGURE 2:

Levels of competent authorities declared to implement tasks under Article 17

FIGURE 3:

National level: number of competent authorities declared

FIGURE 4:

Combination of levels for authorities in charge of tasks under Article 17

FIGURE 5:

Membership in a European Organ Exchange Organisation

FIGURE 6:

Member States granting authorisations for procurement organisations

FIGURE 7:

Duration of authorisations for procurement organisations

FIGURE 8:

Procurement teams coming from abroad to retrieve organs

FIGURE 9:

Measures to ensure compliance with the Directive for procurement

FIGURE 10:

Methods to ensure professional competence of procurement personnel

FIGURE 11:

National consent systems for organ donation

FIGURE 12:

Member States granting authorisations for transplantation centres

FIGURE 13:

Duration of authorisations for transplantation centres

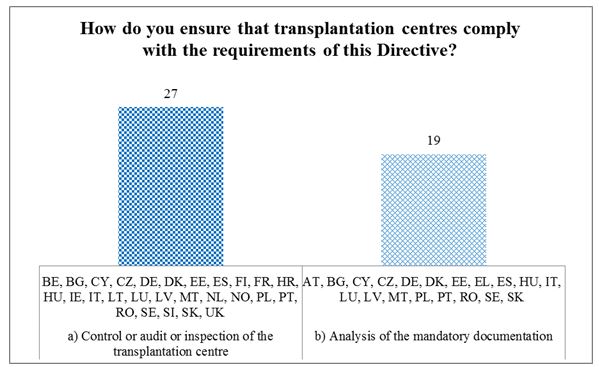

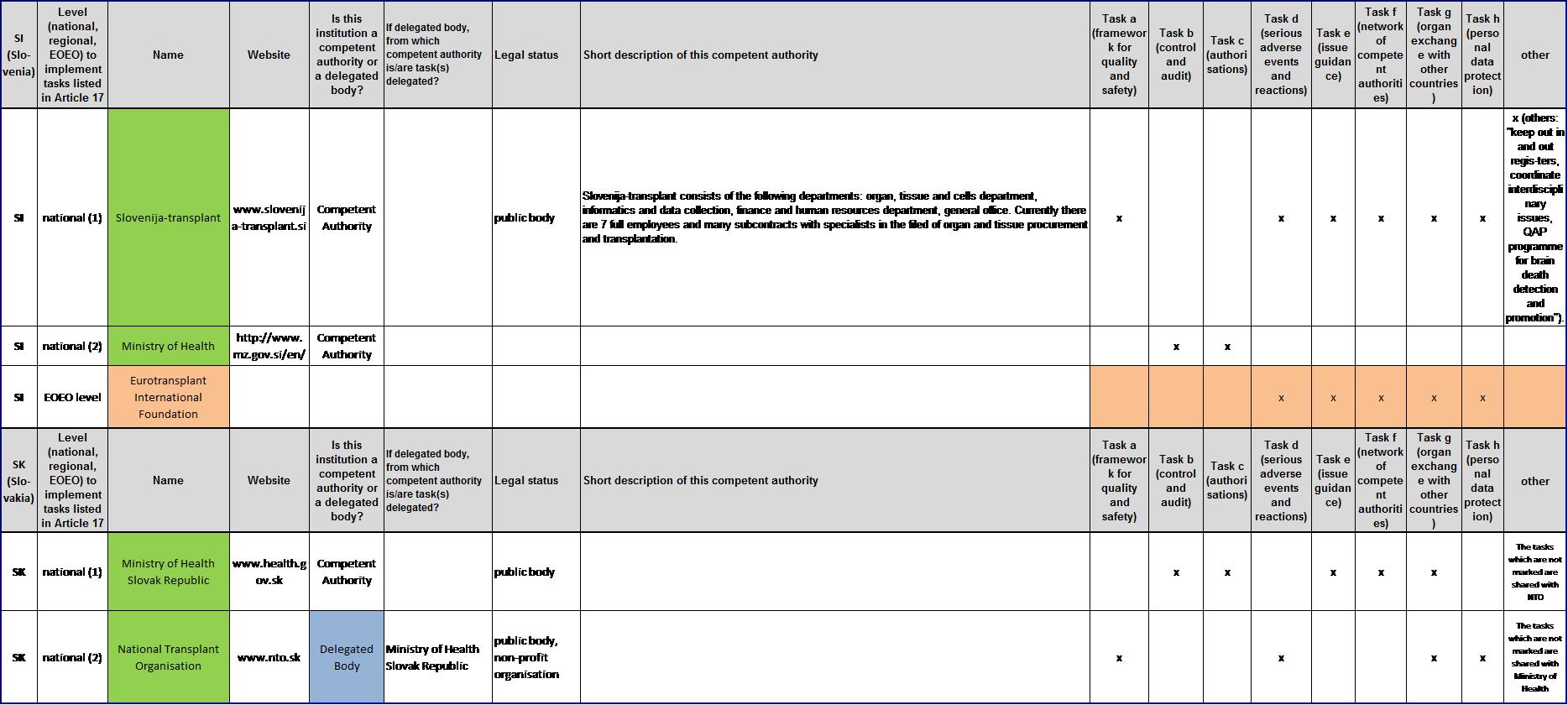

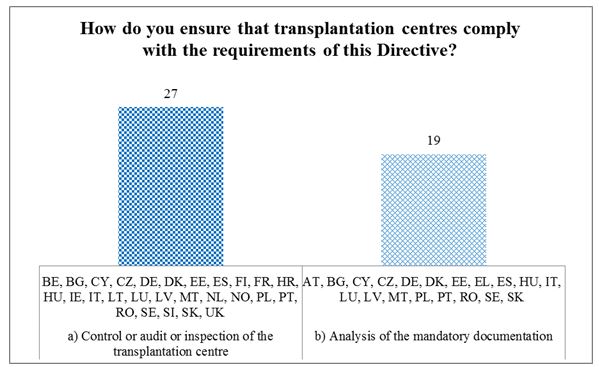

FIGURE 14:

Measures to ensure compliance with the Directive in transplantation centres

FIGURE 15:

Methods for ensuring professional competence of the transplant personnel

FIGURE 16:

Adoption and implementation of operating procedures

FIGURE 17:

Penalties laid down for infringements to national provisions

1. Introduction

Organ transplantation has become a major medical practice at the international level over the past decades. It is the most cost-efficient way to cure renal failure, but also the only treatment available so far for end-stage failure of liver, heart, lung, pancreas or sometimes small bowel. However, the shortage of human organs - donated by living or deceased donors - remains a key challenge. Almost 32000 transplants (see Figure 1) took place in the European Union (EU) in 2014, but also more than 4000 patients died on the transplant waiting lists, while other patients also died while not even on the lists. In total in 2014, 4523 living donors (LD) donated their organs along with more than 10000 deceased donors (DD) (counting both Donation after Brain Death (DBD) and Donation after Circulatory Death (DCD)). The following figure provides an overview of the type and number of organs transplanted in 2014 in the EU.

|

|

Transplants in 2014 in the European Union (28 EU Member States + Norway)

|

Donors (DD: deceased)

|

|

|

Kidney

|

Liver

|

Heart

|

Lung

|

Pancreas

|

Small Bowell

|

Transplants (total)

|

|

|

EU

(% LD)

|

19670

(21,7%)

|

7390

(3,3%)

|

2146

|

1822

|

818

|

44

|

31890

|

10033 DD

(4523 LD)

|

|

pmp

|

38,7

|

14,5

|

4,2

|

3,6

|

1,6

|

0,1

|

62,8

|

19,7

|

|

EU + Norway

|

19944

|

7490

|

2180

|

1855

|

849

|

44

|

32362

|

10147

|

|

pmp

|

38,9

|

14,6

|

4,2

|

3,6

|

1,7

|

0,1

|

63

|

19,8

|

Figure 1. Transplants and donors in 2014 in the European Union and Norway

(Source: Council of Europe Transplant Newsletter 2015) [pmp: per million population]

The European Commission supports Member States to increase organ availability, to improve donation and transplant systems and to ensure quality and safety of these activities. To tackle these challenges, the Commission adopted in 2008 the “Action plan on Organ Donation and Transplantation (2009-2015)”, in order to strengthen cooperation between Member States.

Furthermore, and with a particular focus on quality and safety, the European Union adopted in 2010 Directive 2010/53/EU on standards of quality and safety of human organs intended for transplantation. The Directive is based on Article 168 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union which allows the EU to introduce safety and quality rules for substances of human origin. In 2012, the Commission adopted Implementing Directive 2012/25/EU laying down information procedures for the exchange, between Member States, of human organs intended for transplantation.

The Commission supports Member States in the implementation of the Directives and the Action Plan through co-financing projects under the EU Health Programme, and sometimes the EU Research Programme. The Commission also organises regular meetings of national competent authorities (network established by the Directive) and dedicated working groups to address specific topics under the Action Plan.

Article 22 of Directive 2010/53/EU requires Member States to report to the Commission every three years on their activities undertaken to implement the Directive. Article 22 also obliges the Commission to transmit to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions a report on the implementation of this Directive. The present report was drafted in order to meet the Commission’s reporting requirements and thus presents for the first state of play on the implementation of Directive 2010/53/EU. In order to prepare this report, the Commission launched a survey in 2014 to which all 28 EU Member States and one EEA country (Norway) responded. Additional requests for clarification were sent and answered by Member States. This report reflects the national situations until December 2014.

2. Verification of the transposition of Directive 2010/53/EU

According to Article 31 of the Directive, Member States had to “bring into force the laws, regulations and administrative provisions necessary to comply with this Directive by 27 August 2012.” In order to verify whether all Member States have correctly and sufficiently transposed into their national law the requirements of the Directive, the Commission is currently carrying out a “transposition check”. Where necessary detailed follow-up questions have been sent to individual Member States to seek clarification concerning the transposition of certain provisions. So far, this exercise has pointed to a significant degree of transposition across the EU. Nevertheless, pending the responses received on the requests for clarification, further action may be needed to ensure full transposition of the Directive across all EU Member States.

3. Implementation of Directive 2010/53/EU

While the “transposition check” is a legal exercise based on the analysis of the national legislations, the present report is a reflection of the actual implementation of the Directive and focuses on the concrete activities, measures and policies taken and reported by Member States to implement the Directive.

For the first implementation survey, the Commission decided to focus on those aspects that are important to understand the oversight mechanisms put in place in the Member States. The following Articles in the Directive are particularly noteworthy:

-the identification of the different competent authorities and their tasks (Section 3.1. linked to Articles 17 and 21);

-the schemes to authorise procurement organisations as well as donor and recipient protection (Section 3.2. linked to Articles 5, 7, 12, 14 and 15);- the transport of organs (Section 3.3., Article 8);the schemes to authorise transplantation centres (Section 3.4., Articles 9, 12, 17);

-the framework for quality and safety; in particular the existence of operating procedures (Section 3.5., Articles 4, 11, 17);

-general considerations (Section 3.6., e.g. penalties for infringement of national rules, Article 23).

3.1. Identification of and tasks of the competent authorities and overall set-up

To understand oversight mechanisms in place, it is first necessary to map per country all competent authorities responsible for the tasks defined by Article 17 (Section 3.1.1). It appears that these authorities are national bodies, but sometimes also regional or international entities. Beyond this general view of the organisational set-up, the national level (3.1.2.) will therefore be examined, while the combination of levels (3.1.3.), the regional (3.1.4.) and supra-national (3.1.5.) levels will be scrutinised in subsequent sections. This analysis is supported by the information set out in Annex 1, listing tasks described in Article 17 and the authorities responsible for their implementation.

3.1.1. Organisational set-up

Article 17 is a key provision in the Directive and concerns the designation and tasks of competent authorities. It foresees that Member States “designate one or more competent authorities” and “may delegate, or may allow a competent authority to delegate, part or all the tasks assigned to it […] to another body […] deemed suitable”, i.e. to delegated bodies. These authorities and bodies are responsible for the following tasks listed in Article 17:

(a)establish and keep updated a framework for quality and safety (as defined in Article 4);

(b)ensure that procurement organisations and transplantation centres are controlled or audited on a regular basis;

(c)grant, suspend or withdraw authorisations to procurement organisations and transplantation centres;

(d)put in place a reporting system and management procedure for reporting serious adverse events and reactions (SARE), also called biovigilance;

(e)issue guidance to healthcare establishments, professionals and other parties involved in all stages of the chain from donation to transplantation (e.g. guidance for the collection of relevant post-transplantation information);

(f)participate in the network of competent authorities (as defined in Article 19);

(g)supervise cross-border exchange of organs (as provided for Article 20);

(h)ensure protection of personal data.

The definitions of “competent authority” as well as of “delegated body” leave Member States significant discretion, which leads to a variety of approaches for national implementation. Annex 1 provides a full list of competent authorities and delegated bodies as declared by the 28 Member States and Norway as well as their corresponding tasks.

Only in few countries, all tasks of Article 17 are implemented by a single competent authority. Usually several competent authorities are involved, from different levels: national, infra-national (regional/local) or supra-national.

Figure 2. Levels of competent authorities declared to implement tasks under Article 17 (national, EOEO, regional)

For all 29 countries considered, competent authorities (or delegated bodies) have been appointed at national level. Twelve countries involve European Organ Exchange Organisations, while nine countries also use regional-level authorities (Figure 2).

3.1.2. The national level

The 29 countries considered reported a total of 68 competent authorities operating at national level, including 21 delegated bodies (an average of 2.3 authorities declared per country).

Only five countries (BE, BG, CY, ES, HR) report to have just one body at national level (Figure 3). Fourteen countries declared having two authorities, while six countries report having three authority(ies) and four countries reported having four competent authorities. The involvement of multiple authorities and delegated bodies calls for a good coordination between them. The same applies for Member States that work with European Organ Exchange Organisations and authorities at regional level.

Figure 3. National level: number of competent authorities and delegated bodies declared

National Ministries of Health

Ministries of Health often play a key role in the implementation of Directive 2010/53/EU, but Member States define the national Ministries' powers as regards the tasks under Article 17 in different ways. For 17 countries, the relevant national Ministry has been reported as a competent authority even when it delegates (some of) its tasks to other bodies, whereas for the 12 other Member States (BG, CY, DK, EE, ES, HU, IE, LV, MT, PT, SE, UK) the corresponding Ministry is not defined as a competent authority as it does not perform any operational task on its own and has delegated all tasks.

Delegated bodies

16 Member States also report having appointed delegated bodies, usually just one single delegated body (in 13 countries). These delegated bodies are often public agencies depending on the Ministries of Health. In five countries, delegated bodies include hospitals operating as transplantation centres at a regional (Sweden) or national levels (Denmark, Estonia, Latvia, Norway). Eurotransplant and Scandiatransplant, two European Organ Exchange Organisations, were reported by eight respectively four countries as delegated bodies contributing to tasks under Article 17.

3.1.3. Combination of levels: regional, national and supra-national

In 15 countries, two further levels, besides the national level, are involved in the implementation of the Directive: regional authorities and European Organ Exchange Organisations (EOEOs). Figure 4 shows the different levels involved and the different combinations of levels. The figure highlights the complexity of the oversight settings and the necessity of good coordination mechanisms in each country and between countries.

Figure 4. Combination of levels for authorities in charge of tasks under Article 17

Tasks implemented at national level, levels of competent authorities involved per task

Key tasks under Article 17, which are typically performed at national level, include (a) framework for quality and safety, (d) SARE/biovigilance, (e) issue guidance, (f) attend meetings of the network of competent authorities, and (h) personal data protection. Unless the countries have regions with important responsibilities (see next section), the tasks (b) control and audit, and (c) authorisation are also mainly implemented at national level. Where the country is a member of an EOEO, task (g) supervision of the cross-border organ exchange is implemented with the support of an EOEO.

3.1.4. Involvement of regional authorities and nature of their tasks

Member States have different interpretations of the regional level, often depending on the national legal system and on the organisation of responsibilities in the country. The regional level may refer to administrative entities of Member States which have decentralised powers (AT, BE, DE, ES, FI, FR, IT) or specific responsibilities / task allocation. For instance, Sweden reported four hospitals having a coordination role for a whole region, thus de facto being delegated bodies at regional level. Among the nine Member States which report a role for regional competent authorities, the most common tasks executed at this level are tasks (b) control and audit (in six countries) and (c) authorisation (in seven countries). The total number of tasks assigned to the regional competent authorities varies according to the countries from a single task (Finland) to six tasks (Denmark and Spain).

3.1.5. Involvement of European Organ Exchange Organisations and nature of their tasks

Article 3 provides for a general definition of an EOEO: “a non-profit organisation, whether public or private, dedicated to national and cross-border organ exchange, in which the majority of its member countries are [EU] Member States.” For EOEOs, Article 21 foresees that Member States or competent authorities may conclude agreements with such organisations and delegate to them the performance of activities covered by Article 17, inter alia tasks (a) framework for quality and safety, and (g) supervision of the cross-border organ exchange. Figure 5 shows which Member States use EOEOs and which don’t.

Figure 5. Membership in an EOEO for tasks under Article 17

Three EOEOs exist at the European level, supporting three groups of Member States: Eurotransplant (AT, BE, DE, HR, HU, LU, NL, SI), Scandiatransplant (DK, FI, NO, SE), and the South Alliance for Transplantation (SAT), created in October 2012 by France, Italy and Spain (ES, FR, IT, PT and CH, CZ, EL). The last one is however not reported to be directly involved in the tasks of Article 17. Therefore it does not appear on Figure 5.

Where a country is member of an EOEO, task (g) supervision of cross-border exchange is indeed implemented by or with the support of this EOEO. Often the EOEO is also associated for task (a) framework for quality and safety. The other most commonly performed tasks by EOEOs include (d) reporting and management of Serious Adverse Reactions and Events (SARE), (f) participation in network of competent authorities, and (h) personal data protection. It needs however to be noted that even within the same EOEO, members do not report exactly the same tasks, thus showing that different approaches or agreements might be in place between each country and the EOEO.

Typically the membership in an EOEO or the cooperation with an EOEO (but not as a member) requires some sort of contractual arrangement. Concerning the membership and the existence of a formal agreement between the EOEO and the country, seven Member States (DE, FI, HR, HU, LU, NL, SI) and Norway reported being members of an EOEO with a formal agreement whilst the remaining three Member States (Austria, Belgium, Sweden) do not have yet a formal agreement in place. Several countries are engaged in the conclusion of an agreement with Eurotransplant (e.g. Austria, Belgium). Additionally, Sweden also stressed that the indicated membership in Scandiatransplant occurs rather at the level of transplantation centres and not at the national level.

Among the 17 countries that are not members of an EOEO, nine declare that they collaborate with an EOEO (BG, CZ, EE, EL, FR, IT, LT, SK, UK). Formal agreements have been concluded by five of them (BG, CZ, EL, IT, LT). Countries that collaborate with an EOEO reported that the collaboration consists mainly in cross-border organ exchange. Additionally, the United Kingdom reported “sharing learning, experiences and benchmarking practices.”

Finally, seven countries (CY, IE, LV, MT, PL, PT, RO) reported that they have no relationship with an EOEO. However, for cross-border organ exchange (and their supervision, task (g)), three of them have concluded bilateral agreements with other countries or partners (healthcare establishments): Cyprus with Austria (for lungs), Malta with Italy, and Portugal with Spain. Three other countries (Cyprus, Ireland, Latvia) report exchanging organs with or sending/receiving patients to/from other countries on a bilateral case-by-case basis outside the scope of any agreement. On the issue of cross-border organ exchange, it should be added that the EU-funded Joint Action FOEDUS, building upon the previous project COORENOR, now offers an operational common IT platform for rapid cross-border organ exchange suitable for all European countries (involved or not in EOEOs and in bilateral agreements).

3.1.6. Conclusion on the overall set-up of authorities and tasks under Article 17

All Member States reported having competent authorities (and delegated bodies) in place to cover all tasks defined under Article 17. The overall set-up of competent authorities in Member States and Norway and the tasks they are implementing largely differ from one country to another.

As visible in Figure 4 above, three types of organisational “models” can be defined in relation with tasks of Article 17:

i) countries operating with authorities only at national level (14 countries),

ii) countries operating with authorities at national and regional levels but not at the EOEO level (3 countries) and

iii) countries operating with EOEOs (12 countries).

In all three types of settings, several competent authorities and delegated bodies can be involved to implement the tasks, also because it needs to fit to the size and capacities of the country concerned and because the organ donation and transplantation is completely embedded in the overall organisation of the health system in the country.

While in all Member States, the competent authorities should have a key role to play in ensuring the quality and safety of organs during the entire chain from donation to transplantation, Member States with a unique authority or a limited number of bodies and levels allow, as suggested in Recital 24 of the Directive, for a clearer identification of authorities in charge of the tasks under Article 17, as well as for other tasks outside the scope of this Directive such as consent systems, managements of waiting lists or allocation of organs, and for accountability in general.

The involvement of multiple (levels of) authorities might require enhanced coordination and communication to ensure safety and quality.

3.2. Organ donation and procurement

Organ donation is the first step in the transplantation process. To ensure quality and safety in the donation, procurement organisations play a key role. This section will cover procurement activities and organisations (Sections 3.2.1. to 3.2.4.), the consent systems for organ donation (3.2.5.), the selection and protection of living donors (3.2.6.), the follow-up of transplanted patients (3.2.7.) as well as other key principles for donation (3.2.8).

3.2.1. Authorisation of procurement organisations

To ensure oversight of organ procurement activities, Articles 5, 6 and 17 of the Directive require that procurement organisations are duly authorised, with adequate personnel, material and equipment.

Definitions and authorisation of procurement organisations

The Directive provides for a broad definition of procurement organisations in Article 3 (k): “a healthcare establishment, a team or a unit of a hospital, a person, or any other body which undertakes or coordinates the procurement of organs and is authorised to do so by the competent authority under the regulatory framework in the Member State concerned.”

The definition of an “authorisation” in the Directive also encapsulates different concepts and therefore allows for various interpretations in the national laws: “authorisation” means “authorisation, accreditation, designation, licensing or registration, depending on the concepts used and the practices in place in each Member State.”

Consequently, a wide range of entities can fall within the scope of an “authorised procurement organisation” under these definitions and this is also reflected in the variety of replies received from Member States. Most Member States use several of the options proposed in the definition. (e.g. procurement organisations are both national bodies and hospitals).

Authorisations for procurement organisations are granted at the level of the healthcare establishment in the majority of Member States and Norway (27 of 29 countries). Additionally, they are granted to the team or unit of the hospital (9/29); to any authorised body which coordinates the procurement of organs (8/29); or to any authorised body which undertakes the procurement of organs (4/29). Such authorisations are also granted to individual healthcare professionals (7/29).

Linked to the definition of procurement organisations, the authorisation scheme used in Member States to authorise them is a key issue to ensure oversight of procurement activities. Member States were firstly asked if they grant authorisations for procurement organisations i.e. if they have an authorisation scheme in place. All countries reported having such an authorising scheme, and 26 reported that all the existing procurement organisations in their country had effectively been granted an authorisation (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Member States granting authorisations for procurement organisations

State of play in Member States reporting that not all procurement organisations have been authorised

All countries, except three, report that all their procurement organisations have been authorised (Figure 6). Malta and Ireland are in the process of granting authorisations or developing relevant quality systems within the centres to grant authorisations (Malta does so with the support of the EU-funded project ACCORD, work package of twinning activities). Swedencommented that not all procurement organisations have yet been fully authorised because, while included in their register (registration process complying with the above definition of authorisation), those carrying out highly specialised interventions require an additional authorisation for these interventions. They explained these processes to be directly linked to the transposition of the Directive, with some delay taken in the adoption of secondary legislation and/or in the implementation of practical arrangements.

Particular cases: same authorisation for procurement and transplantation activities

Additionally, some Member States reported using a unique scheme for authorising procurement organisations and transplantation centres, i.e. in these countries all procurement organisations are transplantation centres having an authorisation for procurement activities (see also section 3.4.). Four Member States explicitly reported granting a single authorisation both for procurement organisations and transplantation centres (Denmark, Estonia, Greece, Italy). Estonia specified that the authorisation for organ procurement is covered by the licence to handle organs. In Greece, although the national law differentiates procurement and transplant activities, all transplantation centres are also procurement organisations meaning that no separate authorisation has been granted so far. Several other countries also seem to grant a single authorisation even if they did not explicitly indicate doing so (Finland, Latvia, Malta). For example Finland specified that there is no separate process to grant authorisations for procurement organisations and that only one transplantation centre exists, which also has the teams for organ procurement. In some countries, every authorised transplantation centre is authorised to perform organ procurement (Belgium, Italy).

Length of the authorisation

Figure 7. Duration of authorisations for procurement organisations

More than half of the countries (18/29) grant to procurement organisations authorisations unrestricted in time (Figure 7). Of these, Cyprus specified though that such authorisations are in the process of being time-restricted to one year.

In 11 EU Member States, authorisations of procurement organisations are valid for a specific duration. In three of them, durations are variable while in the other eight countries, fixed validity periods are in place, ranging from two to five years. Five years is the most common duration, applied in five Member States. When authorisations are time-limited to variable durations, validity terms for authorisation are set by Member States according to different criteria. Durations are set at the regional level in Spain, while in Denmark they are based on elements such as the length of the post-occupancy of the doctor responsible for procurement activities. In Member States with fixed validity periods, elements can alter the fixed-term authorisation: in Lithuania and Romania, procurement authorisations are valid on the basis of a five-year period. However, the validity is scaled down to two years when it is the first registration (Lithuania) and authorisations are re-evaluated every two years in Romania.

Renewal and withdrawal of the authorisation

In several Member States, the scheme for renewal of authorisation requires that the criteria applied to grant the initial authorisation are met again at the time of renewal. A few countries report having withdrawn authorisations, usually temporarily, because the initial conditions for granting the authorisation were no longer fulfilled, for example due to the departure of key health professionals

3.2.2. Procurement teams coming from abroad to procure organs

It is current practice in Europe that procurement teams come from abroad. Teams from partner countries come over, within established cooperations, to procure organs usually to be transplanted in the partner country. This helps avoiding losing organs (from existing donors) that would otherwise not be procured. For example, a heart or lung procurement team might go over to countries with only renal or hepatic transplant programmes. While these organs would anyway not be transplanted in the country of origin, such collaboration is still a way for the country of origin to be associated with such procurement programmes in partner countries and eventually to also gain experience with these organs.

26 Member States reported that procurement teams come from abroad on a regular or an ad hoc basis (Figure 8). In 21 of them such activities are performed within the framework of a fixed collaboration like an EOEO or a bilateral cooperation. Most frequently they follow the Eurotransplant or Scandiatransplant frameworks, as a full member or as a partner country of such EOEO (for example Bulgaria, Estonia and Lithuania with Eurotransplant). Several countries have (also) bilateral collaborations with other, often neighbouring countries, for example Cyprus with Italy or United Kingdom, Finland with Estonia, Luxembourg with France, Malta with Italy, Portugal and Spain, Slovakia and Czech Republic.

Figure 8. Procurement teams coming from abroad to retrieve organs

Figure 8. Procurement teams coming from abroad to retrieve organs

3.2.3. Framework for ensuring procurement organisations' compliance with the Directive

To secure a framework for the quality and safety of transplantation activities, Member States must establish a system which guarantees procurement organisations respect the provisions laid down by the Directive. Ensuring this compliance can be achieved by several means, often combined: mainly by control, audit or inspection of the procurement centre, meaning conducting on-site inspections, or by desk-based analysis of the mandatory documentation.

The most commonly used method to ensure compliance is the establishment of on-site controls, audits or inspections of procurement centres, being reported by 22 countries (Figure 9). Desk-based analysis of the mandatory documentation is also a frequent measure, used in 20 Member States. Alternatively, only three Member States declared to use other means (see below). All countries reported making use of at least one of the aforementioned methods and 16 of them use both control/audit of procurement organisations and desk-based analysis of mandatory documentation (BE, CZ, DE, DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, HU, IT, LU, LV, MT, PT, RO, UK). These figures suggest that the combination of different measures may be the most successful way to ensure that the requirements of the Directive are fully met.

Figure 9. Measures to ensure compliance with the Directive (for procurement)

Control, audit or inspection of procurement organisations

Among the 22 countries that control/audit or inspect procurement organisations, more than half have defined regular schemes at national level (12/22). Such schemes provide for a control or inspection of procurement organisations on a regular basis ranging from every year (Czech Republic, Luxembourg) to every three (Latvia) or five years (Slovenia). A two-year length of time between controls is however the most common period, occurring in seven of the countries which use such a method (BG, EE, FR, IE, LT, MT, RO). In some other Member States, schemes for inspections of procurement organisations are set at regional level and therefore vary from one region to another (Germany, Italy, Spain). Three countries declared that they have established risk-based inspection schemes (Denmark, Estonia, Finland), which is an approach also used in other health sectors, and mentioned in the blood and tissues and cells sector.

Rules for inspection and control have not been fixed so far in two Member States (Belgium, Portugal) and Norway.

Desk-based analysis of mandatory documentation

In most of the countries which have adopted this approach, the mandatory documentation includes:

-records of procurement activities or annual reports on transplantations,

-protocols and operating procedures related to the performance of procurement activities,

-qualifications of the personnel and

-reports on serious adverse reactions and events (SARE).

Two Member States have mentioned an EOEO as regards to the analysis of mandatory documentation: Belgium reported the use of the quality form issued by Eurotransplant and Austria uses the mandatory documentation as set by this EOEO to ensure compliance of procurement organisations. Greece reported using the same type of documentation both for the compliance of procurement organisations and transplantation centres. Germany and Latvia also indicated that a unique legislative act provides for the mandatory documentation for both.

Three Member States only use this method to ensure compliance with the Directive (Austria, Cyprus, Greece). Their mandatory documentation mainly covers annual reports of procurement activities.

While very relevant to verify some formal conditions and/or to map some gaps, the desk-based analysis of the mandatory documentation alone may not be sufficient to fully verify the compliance of a procurement organisation. The in-situ control/audit/inspection often includes (or is preceded by) an analysis of the mandatory documentation.

Other methods implemented by Member States

Three Member States reported using other methods than the two measures mentioned above. Poland indicated that “transplant teams responsible for procurement need to hold a five-year permit from the Polish Ministry of Health”, and within this authorisation process, there is a procedure foreseen for “checking and auditing” the organisations (not further described).

In Sweden, until 2013, supervision has been limited to reports on vigilance and adverse events. Swedish authorities also mention, as part of the mandatory documentation, “traceability and documents regarding responsibilities for transport, notification of SARE” and add that “supervision of the transplantation activities are within our regular supervision of the health care establishments”, within explicitly and formally mentioning inspection, control or audit, not the systematic desk-based analysis of the necessary documentation.

The Dutch authorities explained their “other method” by answering that “procurement organisations have to comply with the law.”

In conclusion, these measures classified by some countries as “other” are not well detailed, despite follow-up questions.

3.2.4. Personnel involved in the procurement

Articles 4 and 12 of the Directive require Member States to ensure that the personnel involved in procurement activities are “suitably qualified or trained and competent to perform their tasks and are provided with the relevant training”.

Different approaches can be adopted to assess the competency of the healthcare personnel:

- at the moment of recruitment verifying the qualifications, (23 countries)

- through the completion of regular training programmes (24 countries) or

- through additional certification (11 countries).

All Member States declared having in place at least one of these three measures to ensure that the procurement personnel are capable of performing their tasks (Figure 10). Most Member States combine different methods, which may be the most comprehensive way to meet this requirement.

It should also be noted that different kinds of healthcare personnel are involved in procurement and donation activities (often, but not only, so-called “transplant donor coordinators” or “key donation personnel”, nurses/doctors, different specialties etc.). The profiles also depend upon the healthcare and educational systems of the Member States considered.

Figure 10. Methods to ensure professional competence of healthcare personnel (procurement)

Training can be provided at the international level through international conferences such as EDTCO or ESOT congresses or sessions organised by EU-funded projects (for example ETPOD, the European Training Course in Transplant Donor Coordination or the pilot project on training and social awareness, see also below), for example mentioned by Malta. Programmes designed for continuous training are also offered at the national level (Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal) or at the regional level (Bulgaria, Latvia) including the local scale (hospitals). Few Member States offer training at all levels. Training is provided by specialised bodies including foundations, healthcare establishments, professional associations and societies. Some Member States have made such specific continuous training programmes mandatory in order to be able to continue carrying out the related professional activity.

Italy specified that the certifications required from the coordinating transplantations units are offered periodically through a national programme whilst in Poland the required certification consists of a specialisation in clinical transplantology, offered by medical universities.

In these cases, the certification constitutes more than a simple training programme, because it is a formal

procedure by which an

accredited

or

authorised person

or

agency

(here: a competent authority, medical university or professional organisation) assesses, verifies and

attests

in

writing

by

issuing

a

certificate

, the

qualification

of

individuals

(healthcare professionals), in accordance with

established

requirements

or standards.

Member States that reported ensuring the suitability of personnel by other means perform checks on their profiles and qualifications during the authorisation process of the centres (Cyprus, France, Romania) or during inspection (Portugal, United Kingdom).

EU-level support

Additional support to improve the qualification level of the personnel involved in organ donation was provided by the European Union. The European Commission co-financed the European Training Programme on Organ Donation (ETPOD) under the framework of the EU Health Programme 2003-2008. Finalised in 2010, the project developed four training modules for the different levels of professionals involved in organ donation and provided guidance on the methodologies to adopt to achieve best possible results in such courses. The outcome of the project and the guidelines issued can be used by Member States as tools to improve and develop relevant training courses. As regards to the training for transplant donor coordination, a dedicated course was funded by the European Commission in 2011 in order to increase the quality and quantity of donation and transplant coordination in the EU. In addition, under the 6th work package of the EU-funded ACCORD Joint Action ending in 2015, the Dutch-Hungarian twinning programme allowed not only the training of Hungarian procurement surgeons, but also to improve and make available in English, via the European Society for Organ Transplantation, a dedicated e-learning platform and IT-tool for organ procurement surgery. Also EU-funded, the ODEQUS project offers tools to improve donation programme at hospital level, while the pilot project on organ donation (training and social awareness) to start in 2016 will help Member States in their training efforts. Last but not least, the Working Group on Deceased Donation under the EU Action Plan on Organ Donation and Transplantation, composed by experts from different EU Member States and chaired by the European Commission, developed in 2011 a Manual, for the competent authorities, providing examples of good practices on how to appoint and train key donation personnel and coordinators.

3.2.5. Consent system for organ donation

Article 14 of the Directive requires that procurement activities are “carried out only after all requirements related to consent, authorisation or absence of any objection in force in the Member State concerned have been met”. Indeed Member States have in place different types of national (sometimes even regional) schemes for consent to donate organs after death. Two main consent systems exist in Europe:

-an “opt-in” system under which donors are required to explicitly give their consent for organ donation,

-an “opt-out” system, which lays down the principle of presumed consent unless a specific request for non-removal of organs is made before death.

However, it should be stressed that, regardless of the consent system applied in the country, it is standard practice to approach and consult family members of the deceased prior to any decision to procure an organ.

Figure 11 provides a picture of national choices made regarding consent systems and reported by Member States (despite the fact that consent systems are outside of the direct scope of Directive 2010/53/EU). More than half of the EU Member States (17/28) and Norway have adopted an opt-out system at national level for organ donation. Seven Member States have an opt-in system in place while four countries have a mixed system.

Opt-out systems

Most European countries work on a “presumed-consent” basis, and this system is often supported by registers: citizens can choose to document officially their refusal (in France), their explicit willingness to donate, or sometimes both types of registers are available in the country (for example in Belgium and in Slovenia). While families are always consulted, their consultation might be organised differently in practice: In Greece for example, where the principle is “presumed consent”, after death of a citizen who had not expressed any opposition to donation during his/her life, a family's written consent is required. Norway also indicated that consent from relatives of the donor was always required after death of the donor.

Figure 11. National consent systems for organ donation

Opt-in systems

Opt-in systems in theory require the explicit consent of the donor. Seven countries reported having set up opt-in systems. However the functioning of such systems can vary from an opt-in system in the strict sense: for instance, in some countries, the system requires express consent from the donor but allows the donation with the consent of the next of kin when no express consent from the deceased donor has been given during their life time (Denmark, Germany, Ireland).

Mixed systems

Countries with regional differences or countries combining elements of both opt-in and opt-out systems that cannot be classified in one of these categories only are classified as countries with mixed systems. For instance in Italy, donors have the possibility to explicitly declare their consent for organ donation (via donor cards, registration in national system through local health units, id-paper, signed statement…) and if the consent is not known, relatives are asked for non-opposition to retrieval. In the United Kingdom, the mixed system is the result of regional differences: an opt-in system was in place throughout the UK but Wales now has an opt-out system.

3.2 6. The selection and protection of living donors

For some organs such as kidneys and livers (and very experimentally lungs), living donation is possible, which complements deceased donation to face organ shortages. However, taking an organ from a healthy person to treat another person is an invasive measure and can have medical, but also psychological, social and economic consequences for the donor. Therefore living donors must be carefully screened, selected and followed up before, during and after donation.

Article 15 lays down that Member States shall take all necessary measures to ensure the highest possible protection of living donors and shall ensure that they are selected on the basis of their health and medical history, by competent professionals (this selection should happen through assessments that may provide for the exclusion of persons whose donation could present unacceptable health risks). In addition, Member States shall ensure that a register or record of living donors is in place and shall carry out their follow-up Moreover, they shall have a system in place in order to identify, report and manage any event potentially relating to the quality and safety of the donated organ (and hence of the recipient) as well as any serious adverse reaction in the living donor that may result from the donation.

Over the last years, several EU-funded projects such as EULID, ELIPSY, EULOD, ACCORD have created tools and methodologies to support Member States in these efforts.

Overall, most countries have introduced registers or records for living donors. Most of the countries (17/29) reported having initiated a register before the adoption of the Directive in July 2010 (BG, CZ, DE, DK, EE, EL, FI, FR, HU, IE, IT, LV, NL, NO, PL, SK, UK), while others have launched such records in 2014 or 2015. 23 countries report keeping a register or a record to follow up living donors. The remaining six countries (AT, HR, LU, MT, PT, SI) reported that they have no such register in place at present, but some of them plan to establish ones in the near future (Croatia, Portugal, Slovenia). In Luxembourg, the implementation of this register will be subject to an update of the related national scheme. Austria, Hungary and Portugal reported that they do not keep records at national level, though some are kept in each transplantation centre. Malta also indicated that no national record was kept but that data was available.

Type of record/register: establishment, level of record keeping and content

In most Member States maintaining records of living donors, record keeping is set at national level (16/23). Four Member States reported that a record is kept at the international level, their national data on living donors being included in the relevant record hosted by their EOEO (Belgium with Eurotransplant; Denmark, Sweden and Norway with Scandiatransplant). Some Member States specified that a record is locally kept by each transplantation centre (Finland, Romania).

Significant discrepancies are noted between Member States in the content and type of data captured in the register, often depending on the type of transplantation performed. Some countries did not mention any limitation of the record to donors of a specific kind of organs, while in other Member States records are only kept for kidneys (in Finland, Greece and Spain) or liver (Germany). The notions of "record" or "register" are not interpreted in the same way in Member States, leading to differences in the content of such reporting documents (light/comprehensive information). A few countries mentioned the unreliability of their records, which can lack some information or be unclear since data on living donors is included in more general medical records which do not focus on living donors (Estonia).

Being aware of such differences in the way Member States keep track of and follow up their living donors (differences that affect the collection of accurate and valuable data on the availability of organs from donors, thus reducing transplantation possibilities), the European Commission co-financed the Joint Action ACCORD

. One priority area for ACCORD was living donor registries: national registries and international data sharing. The guidelines and standards produced for the set-up and implementation of such registers has been recognised as a benchmark, and the development of this model for a (European) Register of (national/local) Registries, aimed at collecting living donor follow-up data in an international database, was also studied and tested. After results of this project received positive feedback from competent authorities who also asked for continued support on this topic, the European Commission was able to propose its inclusion within the scope of a new, so-called “pilot project” initiated by the European Parliament. This project focusing on kidney diseases

will start in 2016 and will further support Member States willing to improve their living donation systems. The recently adopted Council of Europe Resolution on the same topic, explicitly mentions ACCORD deliverables as reference documents

and thus confirms and expands the recognition of their value also to non-EU Member States.

Type of follow-up of living donors

The majority of countries provide a follow-up to living donors after donation (27 of 29 countries). However, living donors are not currently provided with medical follow-up in two Member States (Bulgaria, Greece). In a few Member States, the need for a medical follow-up and its frequency are assessed on a case-by-case basis for each donor. Estonia also specified that follow-up is only conducted upon a patient's request, in case of a post-operatory problem.

As regards to the frequency, some countries have set fixed periods for conducting medical follow-ups, which occur on a regular basis varying from a week after donation and every two weeks after, to monthly or yearly medical evaluations. Roughly half of the countries (16/29) provide a lifelong medical attention to donors, while seven have defined fixed terms for their follow-up, ranging from a year to five, ten or thirty years. While four countries do not seem to have a scheme at all for donor follow-up (Bulgaria, Greece, Lithuania and Luxembourg), two other (Austria and Estonia) have not defined schemes for the regularity of follow-ups.

In all 27 countries where a medical follow-up is provided to donors, such follow-up includes a review of the general health status of the donor, evaluation of any complication and functioning of the remaining organ. In addition, the medical treatment provided is assessed and blood pressure or blood status are considered in 26 countries. Psychological aspects are not considered in six of them. Results of past EU-funded projects such as EULID, ELIPSY and the ACCORD Joint Action provide tools to set up a solid follow-upsystem. The future EU-funded pilot project on kidney diseases, to start in 2016 for three years, will include a dedicated work package on the follow-up of living donors for kidney and liver living donors, to help Member States further improve their corresponding schemes.

3.2 7. The follow-up of transplanted patients

While the follow-up of living donors is a core requirement of Directive 2010/53/EU (Article 15), the follow-up of transplanted patients is left to Member States’ decisions. Recital 24 of the Directive recognises that “the competent authorities of the Member States should have a key role to play in ensuring the quality and safety of organs during the entire chain from donation to transplantation and in evaluating quality and safety throughout patients’ recovery and during the subsequent follow-up.

Therefore, besides the system for reporting serious adverse events and reactions, the collection of post-transplantation data is needed for a more comprehensive evaluation of the quality and safety of organs intended for transplantation. Sharing such information between Member States would facilitate further improvement of donation and transplantation across the Union.” Task (e) foreseen for competent authorities under Article 17 also includes this aspect: “issue appropriate guidance to healthcare establishments, professionals and other parties involved in all stages of the chain from donation to transplantation or disposal, which may include guidance for the collection of relevant post-transplantation information to evaluate the quality and safety of the organs transplanted.”

The European Commission, to support Member States and international sharing on this topic, co-funded via the EU Health Programme the collaborative project EFRETOS. The general objective of this project was to provide a common definition of terms and methodology to evaluate the results of transplantation, and to promote a model for registry of registries with follow-up data. The project was finalised in 2011 and since then results produced have been available to all Member States. It also provided a blue-print for a European registry enabling the monitoring of patients and the evaluation of transplant results beyond national borders. In addition, registers developed and held by transplant professionals and societies - such as ERA-EDTA for kidneys or ELTR for livers - also play a key role in these topics, several competent authorities collaborate with them and the European Commission encourages such cooperations by inviting them to meetings with all authorities in Brussels. Finally, the future EU-funded pilot project on kidney diseases to start in 2016, already mentioned above, will also include a Work package on the follow-up of transplanted patients, building upon EFRETOS consensus results.

3.2.8. Other key principles governing organ donation

In addition to consent requirements (see Section 3.2.5.) and the selection and protection of living donors (see Section 3.2.6.), other key principles govern organ donation. Article 13 of the Directive lays down that donations of organs from deceased and living donors are voluntary and unpaid, but that the principle of non-payment shall not prevent living donors from receiving compensation, provided it is strictly limited to making good the expenses and loss of income related to donation. The Directive asks Member States to define the conditions under which such compensation may be granted, while avoiding there being any financial incentives or benefit for a potential donor.

Six Member States reported that they have not defined the conditions for such compensation. Of these Malta and Romania indicated that no compensation was given, as happens in Latvia in case of living donation. Ireland is in process of defining a national scheme for compensation.

Also related to this topic, cross-border living organ donation is a specific issue that requires coordination between Member States, in particular regarding the donor follow-up. A Recommendation concerning financial aspects of cross-border living organ donations was also issued at EU level in 2012 by the administrative Commission for the coordination of social security systems.

3.3. Transport of organs intended for transplantation

Because organs must be transplanted quickly after the procurement, the transportation of the organs intended for transplantation is a key stage in the chain from the donor to the recipient, in particular when organs are exchanged across borders. The quality and safety aspects of the transport are covered by Article 8 (and Article 9.3.b.).

Organisation of organ transportation

Transportation of organs is managed differently across the EU. Transport coordination is organised either by the procurement team (e.g. Cyprus), by transplantation centres (e.g. Belgium, France, Slovakia), by an authority at regional level (Denmark) or, more frequently, by an authority at national level or by a body which has been delegated the task (e.g. ES, HR, LV, NO, PT). Transport can involve private transportation companies (external contracts), internal transportation services from transplantation centres or competent authorities, or specialised state transport systems.

Ensuring the respect of transportation rules

Countries usually ensure that the organisations/companies involved in the transportation of organs have appropriate procedures in place through the establishment of specific operating procedures or rules on transportation. Bodies responsible for coordinating transport set up protocols to be followed by transportation services and issue guidelines and instructions. As foreseen under Article 9.3.b., at the arrival of organs, transplantation centres check if dedicated procedures have been regarded and if the conditions of preservation and transport of shipped organs have been maintained. Most of the time, a competent authority is responsible for auditing or conducting inspections to ensure the respect of these procedures. In a few countries, the transportation can occur only in the presence of a medical doctor (e.g. Bulgaria).

Labelling of shipping containers, documents on organ and donor characterisation

As required under article 8, in all countries with the exception of Lithuania, labelling information on transport containers includes identification of the transplantation centre of destination; a statement that the package contains an organ and details on the type of organ; recommended transport conditions. In the majority of countries (27/29), organs are always transported accompanied by a report on organ and donor characterisation (except for Greece and Luxembourg).

The information on organ and donor characterisation is not labelled in English

in 15 Member States, but most of the time labelled in the national / local language. Commission Implementing Directive 2012/25/EU on cross-border exchange of organs foresees (Article 4) that Member States shall ensure that, in case of cross-border exchange, such information is written in a language mutually understood by the sender and the addressee, or in absence thereof, in a mutually agreed language, or failing that, in English.

Last but not least, on the preservation of organs, it can be noted that an EU-funded Research project such as COPE (Consortium for Organ Preservation in Europe) contributes, thanks to clinical trials, to investigating new techniques for organ preservation and comparing the different techniques available.

3.4. Authorisation of transplantation centres and qualification of personnel

This section is devoted to the authorisation schemes for transplantation centres (3.4.1.), the framework set by Member States to ensure that transplantation centres comply with the Directive (3.4.2.) and to ensure the qualification of personnel involved in transplant activities (3.4.3.).

3.4.1. Authorisation of transplantation centres

In the same way as for procurement organisations (see Section 3.2.1.), the Directive (Articles 9 and 17) foresees an authorisation scheme for transplantation centres, in order to ensure the oversight of transplant activities.

Definitions and authorisation of transplantation centres

Again, the Directive provides for a broad definition of transplantation centres in Article 3 (r): “a healthcare establishment, a team or a unit of a hospital or any other body which undertakes the transplantation of organs and is authorised to do so by the competent authority under the regulatory framework in the Member State concerned.” Consequently, different levels can fall within the scope of a “transplantation centre”. Like for procurement organisations, the definition of an “authorisation” in the Directive also encapsulates different concepts and therefore allow for various interpretations in the national laws. Most Member States use several of the options proposed in these broad definitions. Authorisations for transplantation centres are granted at the level of the healthcare establishment in the majority of Member States and Norway (26 of 29 countries). Additionally, they are granted to the team or unit of the hospital (11/29) or to any authorised body which undertakes the transplantation of organs (2/29).

The authorisation scheme used in Member States to authorise transplantation centres is a key issue to ensure their oversight. All Member States mentioned to have such authorisation scheme (but it is to be noted that for six Member States (AT, BE, DE, ES, FR, IT) the regional level in charge of authorising, see Annex 1 and in particular the column for task (c)).

State of play in Member States where not all transplantation centres have been authorised

25 countries answered that all transplant centres had effectively been authorised, while four countries (Ireland, Luxembourg, Latvia, Malta) explained that they were still in the process of granting (new or renewed) authorisations to (some of) their centres. They explained that this process is directly linked to the transposition of the Directive, with some delays in the adoption of secondary legislation and/or in the implementation of practical arrangements.

Figure 12. Member States granting authorisations for transplantation centres

In Ireland, initial inspections have been performed in all transplantation centres and a quality system based on these is currently being developed. The authorisation scheme is also in progress in Latvia while Malta reported being in the process of authorising the transplantation unit of the State hospital, which has already been authorised for procurement activities. For Luxembourg, it should be noted that no transplantation activities are performed currently and that no transplantation centres exist, thus none have been authorised.

Specific cases

In Estonia and Sweden, all transplantation centres have been authorised. However, they are not granted any specific authorisation since either holding a valid licence for specialised care or being registered as a healthcare provider with a transplantation orientation is considered as equivalent to an authorisation within the national legislation, also in line with the broad definition of “authorisation” in Directive 2010/53/EU.

Length of the authorisation

15 countries reported to grant authorisations to transplantation centres which are not time-limited (to be compared to the authorisations of procurement organisations, not time-limited in 18 Member States: the same 15 countries plus Cyprus, Luxembourg and Sweden, see Section 3.2.1.). In this line, the length of validity of authorisations granted to transplantation centres is relatively similar to the validity of authorisations granted to procurement organisations.

As for the 14 Member States which grant time-limited authorisations to transplantation centres, situations vary between authorisations for a fixed period (one, two, three, four or five years) and authorisations for variable periods (Figure 13).

Authorisations with variable time-limited validities

In four Member States authorisations are granted for variable durations: Sweden and three countries that also have a similar variable validity for authorisations of procurement organisations: Denmark, Italy and Spain. Different criteria are taken into consideration to decide about this length. In Denmark, in the same way as for procurement organisations, the validity period of the authorisation corresponds to the length of the post-occupancy of the doctor responsible for transplantation activities or to the duration of the hospital's function of transplantation centre. In Italy, different time frames are set according to the type of organ donor: in the case of living donors, the validity of the authorisation is three years, while for all other cases it is two years. In Sweden, the type of organ determines the time limit: for instance, the duration of the authorisation extends to five years for heart and lung transplantations. In some countries, the validity of the authorisation differs from one region to another as it is decided at regional level (Spain).

Figure 13. Duration of authorisations for transplantation centres

Fixed time-limited authorisations

In countries where authorisations are granted for a fixed period, the most common duration is five years (5 of 9 Member States) and the authorisation is renewed after an evaluation has been conducted to ensure that the initial requirements for granting the authorisation are still met. These five countries (France, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovenia) are equally granting authorisations for five years to procurement organisations. These countries assess the results of transplant activity or the capability of the transplantation centre to carry out transplantations (e.g. Greece). In Lithuania, licences must be registered and are valid for two years after the first registration and for five years after the first renewal of authorisation.

Cyprus grants authorisations to transplantation centres for one year (not limited in time for procurement organisations), while Malta, Greece and Croatia grant them for exactly the same validity as for procurement organisations, respectively two, three and four years.

3.4.2. Framework for ensuring compliance with the Directive in transplantation centres

As reflected in Figure 14, in most EU Member States and Norway (27/29), compliance with the requirements of the Directive is verified through conducting on-site controls, audits or inspections of the transplantation centres (measure a). Only Austria and Greece do not use inspections. More than half of the Member States (19/28) perform desk-based analysis of the mandatory documentation (measure b). Slightly more than half of the countries use both methods (17/29).

Figure 14. Measures to ensure compliance with the Directive in transplantation centres

Member States' procedures to ensure compliance of transplantation centres are similar than those to ensure compliance of procurement organisations. Measure a) control/audit/inspection is respectively used in 22 Member States for procurement organisations and in 27 Member States for transplantation centres, while measure b) desk-based analysis is conducted in 20 countries for procurement organisations and in 19 for transplantation centres.

Mechanisms for controls/audits/inspections of transplantation centres

Countries that perform controls, audits or inspections have different systems in place. Some of them have adopted a risk-based approach for implementing controls (Denmark, Estonia), while others have set fixed periods of time: every year (Cyprus), every two years (BG, IE, LT, MT, RO), every three years (Czech Republic, Latvia), or every five years (France, Slovenia).

The operational procedure for conducting controls is defined at different levels: either at national level (Slovakia) or regional level (Spain) and in some countries both levels are involved (Germany).

Desk-based analyses of the mandatory documentation

In some Member States, the required documentation is specified by the national legislation (BG, DE, EE, FR, HU, IT, LV, RO). Italy reported the involvement of the regional level in the analysis of the mandatory documentation. One country reported following the relevant provisions established by an EOEO (Austria and Eurotransplant).

In most of the countries which specified the nature and content of mandatory documentation, such documentation includes:

-qualifications of personnel involved in transplantation activities,

-protocols and operating procedures related to organ transplantation,

-annual reports on transplantation activity.

Portugal reported additional documents such as written proof of the donor's informed consent. Sweden mentioned investigating mandatory SARE reports.

Combining inspections and analysis of the documentation is the approach adopted in 15 countries for procurement organisations and in 17 for transplantation centres, and seems an appropriate approach as both methods enable to check complementary aspects.

3.4.3. Personnel involved in transplantation activities

Articles 4 and 12 require that the transplantation personnel are suitably qualified and trained to perform their tasks. As for the procurement personnel, that purpose can be achieved by using several methods, as reflected in Figure 15.

Twenthy-tree countries ensure that the healthcare personnel involved in the transplant activities are suitably qualified or trained and competent at the time of recruitment, considering the corresponding qualifications of the applicants (measure a, used in 23/29 countries). Some Member States request registration to the relevant regulatory body (Malta, the Netherlands); require previous experience (Germany, Italy) or relevant training in addition to qualifications (BE, DE, IE, LT, PT, RO).

Regular training programmes are foreseen in 24/29 countries. These can be organised at different levels: at national level in Germany, Ireland and Lithuania, at both national and international levels are involved in Malta, Poland and Sweden, at hospital level in DE, IE, LV, NL, PL and UK. Five countries (DE, IE, LV, MT and SE) also declare to rely on trainings organised by professional societies or organisations - for Europe in particular, the Section of Surgery and the European Board of Surgery of the European Union of Medical Specialists (UEMS) operating in close collaboration with the European Society of Organ Transplantation (ESOT). A twinning training programme was also mentioned (by Malta) as well as annual training courses organised by professional societies at the international level between Scandinavian countries.

Sixteen countries require additional certification, which can be obtained by following specific courses offered by professional organisations (Germany) and might require a registration of the specialisation needed (Latvia). The Netherlands reported a mandatory programme offered at national level by the Health Ministry; Slovenia and Romania also mentioned national training modules. International training programmes (such as UEMS scheme mentioned above) linked to a certification can also constitute an international certification complementary to (or replacing) national certifications (when recognised by national competent authorities authorising transplantation centres and teams).

Eleven countries combine use of all three measures (a, b, c). Five Member States reported other measures, including assessment of personnel during the authorisation process of the transplantation centre (Cyprus, France); requirement of a mandatory length of previous experience for physicians and assistants to carry out transplantation activities (Austria); mandatory attendance to congresses and symposiums respectively for physicians and nurses (Germany).

Figure 15. Methods for ensuring professional competence of the transplant personnel

3.5. Framework for quality and safety

While the authorisation of procurement organisations and tranplantation centres is an important element in the oversight of donation and transplantation activities, other measures also contribute to their quality and safety.

The Directive requires Member States to establish a framework for quality and safety covering all stages of the chain from donation to transplantation or disposal, also requiring the issuance of operating procedures for different actions. This section provides a state of play, as reported by Member States, on adoption and the level of implementation of these operating procedures.

All 29 countries reported having set and implemented operating procedures for the verification of the completion of the organ and donor characterisation (c) in accordance with Article 7 of the Directive. However, three Member States do not have any operating procedures in place at present for any of the other areas (Portugal, Romania, Slovenia). Likewise, Austria does not have any procedure for ensuring traceability, guaranteeing compliance with provisions on the protection of personal data and confidentiality (f), reporting (g) and management (h) of SARE. In addition to the aforementioned actions, there is no operating procedure in Romania for the verification of the donor identity (a), neither for the verification of the details of the donor's or donor's family consent (b).

Variations in the levels of adoption and implementation of operating procedures

Countries are at different stages in the adoption and implementation of operating procedures. Some of them have completed the process and a framework for quality and safety is fully in place complying with the Directive, while others have partially adopted a framework and the adoption process and/or implementation for the remaining operating procedures is ongoing. Some Member States are updating their national framework relevant to the provisions of the Directive (e.g. Romania).

Differences in the content of operating procedures

Some Member States declared that they have operating procedures in place but also mentioned that they might be different from one hospital or region to another, while only a few Member States seem to have national operating procedures in place, at least for the whole chain from donation to transplantation. Some Member States have sent examples of their operating procedures in attachment to their answers to the implementation survey. A rapid analysis of their content revealed significant differences between operating procedures related to the same action.

Projects co-funded by the European Commission have supported the development of operating procedures complying with the Directive's requirements, for example, within the ACCORD Joint Action, the twinning activities between France and Bulgaria.

The European Commission encourages Member States to share best practices, including relevant documents and made sure to put at the disposal of all competent authorities the operating procedures shared by some Member States, so that other Member States can take benefit to develop their own versions and/or compare with their national documents, thus contributing to an harmonisation of (good) practices and to a further improvement of their quality and safety frameworks.

3.6. General points

3.6.1. Legal framework for non-compliance with the Directive (penalties)

As provided by Article 23 of the Directive, “Member States shall lay down the rules on penalties applicable to infringements of the national provisions adopted pursuant to this Directive and shall take all necessary measures to ensure that the penalties are implemented.”

Member States were asked which types of penalties they have put in place to comply with the Directive: financial penalties, imprisonment, withdrawal of authorisation (for procurement organisations and transplantation centres), other or no penalties in place (Figure 17).

Figure 17. Penalties laid down for infringements to national provisions

Only one Member State (Hungary) reported that no penalties have been laid down for infringements of national provisions adopted pursuant to the Directive, but that should, however, change in the near future when all operating procedures are available.

Most countries (27/29) have set up financial penalties. Withdrawals of authorisation or prison sentences are penalties also commonly used for breaches of national provisions, in place respectively in 20 and 19 Member States.

One country established penalties which do not fall within any of the aforementioned categories (Latvia): the mandatory performance of community service and the suspension from medical practice.

Combined use of options

In 24 countries (all Member States without Austria, Croatia, Hungary, Portugal and Norway), more than one type of penalty is being used. Both financial penalties and imprisonment are reported in 19 countries while financial penalties and withdrawals of authorisations are common sentences in 19 other countries. 14 Member States declare combining all three types of penalties (CZ, ES, FR, IE, IT, LU, LV, MT, PL, RO, SE, SI, SK, UK).

Types of financial penalties and imprisonment sentences

In 14 of the countries that provided information on the amounts applicable in case of a financial penalty, such penalties exceed €1,000.

As regards to the duration of imprisonment, the term does not exceed one year in Belgium and the Netherlands whereas in the remaining countries sentences can be longer. The maximum length of imprisonment reported is ten years (Poland).

Schemes for ensuring the enforcement of penalties