EUROPEAN COMMISSION

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Strasbourg, 13.6.2017

SWD(2017) 246 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

IMPACT ASSESSMENT

Accompanying the document

Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council

amending Regulation (EU) No 1095/2010 establishing a European Supervisory Authority (European Securities and Markets Authority) and amending Regulation (EU) No 648/2012 as regards the procedures and authorities involved for the authorisation of CCPs and the requirements for the recognition of third-country CCPs

{COM(2017) 331 final}

{SWD(2017) 247 final}

Table of contents

Glossary and list of abbreviations used

1.INTRODUCTION AND RATIONALE

2.BACKGROUND AND POLICY CONTEXT

2.1.The key role of CCPs in the financial system

2.2.CCPs have increased in size following post-crisis regulatory reforms - and continue to grow in importance

2.3.The CCP landscape: concentration, integration and interconnectedness

2.4.The current supervisory arrangements under EMIR

2.5.Relevant international standards and EU initiatives on CCPs

3.PROBLEM DEFINITION

3.1.Analysis of current EMIR supervisory arrangements

3.2.Inconsistency in the arrangements for supervision of EU-based CCPs and role of the CBI

3.3.Insufficient mitigation of third-country CCP risks

3.4.Potential risks from inaction

4.OBJECTIVES

4.1.Subsidiarity

4.2.Objectives

4.3.Consistency of the objectives with other EU policies

4.4.Consistency of the objectives with fundamental rights

5.POLICY OPTIONS AND ANALYSIS OF THEIR IMPACT

5.1.Baseline scenario

5.2.Options for improving the consistency of supervisory arrangements for CCPs established in the EU

5.3.Mitigation of third-country CCP risks

6.OVERALL IMPACT OF THE PACKAGE

6.1.Small and medium-sized enterprises

6.2.Administrative burden

6.3.EU budget

6.4.Social impacts

6.5.Impact on third countries

6.6.Environmental impacts

7.MONITORING AND EVALUATION

ANNEX 1: Overview of changes addressing the recommendations of Regulatory Scrutiny Board (RSB)

ANNEX 2: Overview of the derivatives market and of the CCP landscape

ANNEX 3: Procedural information

ANNEX 4: Stakeholder consultation

ANNEX 5: Who Is Affected By The Initiative And How?

ANNEX 6: Analysis of the current functioning of supervisory colleges

Glossary and list of abbreviations used

Glossary

|

Central Counterparty (CCP)

|

A legal person that interposes itself between the counterparties to the contracts traded on one or more financial markets, becoming the buyer to every seller and the seller to every buyer.

|

|

Clearing

|

The process of establishing positions, including the calculation of net obligations, and ensuring that financial instruments, cash, or both, are available to secure the exposures arising from those positions.

|

|

Clearing member/direct participant

|

An undertaking which participates in a CCP and which is responsible for discharging the financial obligations arising from that participation.

|

|

Collateral

|

An asset or third-party commitment that is used by the collateral provider to secure an obligation to the collateral taker. Collateral arrangements may take different legal forms; collateral may be obtained using the method of title transfer or pledge.

|

|

Counterparty credit risk

|

The risk that a counterparty will not settle an obligation for full value, either when due or at any time thereafter. Credit risk includes pre-settlement risk (replacement cost risk) and settlement risk (principal risk).

|

|

Credit risk

|

The risk of a change in value due to actual credit losses deviating from expected credit losses due to the failure to meet contractual debt obligations.

Credit risk comprises default and settlement risk. Credit risk can arise on issuers of securities (in the company’s investment portfolio), debtors (e.g. mortgagors), or counterparties (e.g. on derivative contracts, or deposits) and intermediaries, to whom the company has an exposure.

|

|

Margin (initial/variation)

|

An asset (or third-party commitment) that is accepted by a counterparty to ensure performance on potential obligations to it or cover market movements on unsettled transactions.

‘Initial margin’ means margins collected by the CCP to cover potential future exposure to clearing members providing the margin and, where relevant, interoperable CCPs in the interval between the last margin collection and the liquidation of positions following a default of a clearing member or of an interoperable CCP default.

‘Variation margin’ means margins collected or paid out to reflect current exposures resulting from actual changes in market price.

|

|

Non-Financial Counterparty (NFC)

|

An undertaking established in the European Union that is not a CCP or a financial counterparty, as defined in Article 2(9) of EMIR. The requirements of EMIR vary depending on the profile of a non-financial counterparty.

In determining whether an NFC should be subject to the clearing obligation, EMIR gives consideration to the purpose for which that NFC uses OTC derivative contracts as well as to the size of the exposures that it has in those instruments. NFCs are subject to the clearing obligation and risk mitigation techniques requirements where their positions in non-hedging OTC derivatives exceed certain thresholds defined by ESMA.

The thresholds are EUR 1 bn in gross notional value for credit and equity derivatives and EUR 3 bn for interest rate, foreign exchange, and commodity or other derivatives. Once an NFC surpasses one of these thresholds in any asset class, it becomes subject to these requirements across all asset classes. These NFCs are commonly referred to as 'NFC+' as opposed to NFCs below the threshold which are known as 'NFC-'.

|

|

OTC

|

The phrase "over-the-counter" (or OTC) can be used to refer to stocks that trade via a dealer network as opposed to on a regulated market. It also refers to debt securities and other financial instruments such as derivatives, which are traded through a dealer network.

|

|

OTC derivative

|

A derivative contract the execution of which does not take place on a regulated market as within the meaning of Article 4(1)(14) of Directive 2004/39/EC or on a third-country market considered as equivalent to a regulated market in accordance with Article 19(6) of Directive 2004/39/EC.

|

List of abbreviations used

|

CBI

|

Central Bank of Issue

|

|

CDS

|

Credit Default Swaps

|

|

CCP

|

Central Counterparty

|

|

CMU

|

Capital Markets Union

|

|

EMIR

|

'European Markets Infrastructure Regulation', short for: Regulation (EU) No 648/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 July 2012 on OTC derivatives, central counterparties and trade repositories

|

|

ESA

|

European Supervisory Authority

|

|

ESCB

|

European System of Central Banks

|

|

ESMA

|

European Securities and Markets Authority

|

|

ESRB

|

European Systemic Risk Board

|

|

ETD

|

Exchange-Traded Derivatives

|

|

IRS

|

Interest-Rate Swaps

|

|

IRD

|

Interest-Rate Derivative

|

|

NFC

|

Non-Financial Counterparty

|

|

OTC

|

Over The Counter

|

|

TR

|

Trade Repository

|

1.INTRODUCTION AND RATIONALE

Use of Central Counterparties (CCPs) required as a response to the financial crisis

Derivatives contracts are used by financial and non-financial economic actors to manage risks related to changes in interest rates, currency fluctuations, the default of a business counterpart etc. However, the opacity of derivatives played a key role in the financial crisis and notably the problems encountered by Lehman Brothers, AIG and others.

In accordance with the 2009 G20 Pittsburgh agreement

to reduce the systemic risk linked to extensive use of derivatives, the EU adopted the European Market Infrastructure Regulation (EMIR) in 2012

. A key pillar of EMIR is the requirement for standardised OTC derivatives contracts to be cleared through a Central Counterparty (CCP), which entered into force in December 2015

. A CCP is a market infrastructure, which reduces systemic risk and enhances financial stability by standing between the two counterparties to a derivatives contract (i.e. acting as buyer to the seller and seller to the buyer of risk) and thereby reducing the risk for both. EMIR also introduced strict prudential, organisational and business conduct requirements for CCPs and established arrangements for their prudential supervision to minimise any risk to users of a CCP and underpin systemic stability. Under EMIR, derivatives transactions which are not centrally cleared by a CCP are subject to additional collateral requirements on the bilateral exposures reflecting a higher implied counterparty risk and potentially higher risk to systemic stability

.

CCPs have grown in importance since 2012 and will expand further in the coming years

In the five years since the adoption of EMIR, the volume of CCP activity – in the EU and globally - has grown rapidly not only in scale but also in scope. At present, around 62% of the global value of all OTC derivatives contracts and asset classes (interest rates, credit default, foreign exchange, etc.) is centrally cleared by CCPs

, which is equivalent to $337 trillion. About 97% ($328 trillion) of all centrally-cleared derivatives contracts are interest-rate derivatives. At the end of 2009, about 36% of all OTC interest-rate derivatives were centrally cleared, while the corresponding figure by the end of 2015 was 60%

. Central clearing has similarly gained in importance in the credit derivatives (so-called CDS) market, with the proportion of outstanding CDSs cleared through CCPs increasing steadily since these data were first reported, i.e. from 10% at the end of June 2010 to 37% at end the end of June 2016

.

The rapidly expanding role of CCPs in the global financial system reflects not only the introduction of central clearing obligations across different asset classes

, but also increased voluntary use of central clearing amid growing awareness of the benefits of central clearing among market participants (clearing obligations have applied only since June 2016). EMIR requires certain interest-rate derivatives and CDSs to be centrally cleared in line with similar requirements in other G20 countries

. Bank capital rules have been changed to incentivise central clearing and make bilateral clearing a costlier option in relative terms

, while bilateral transactions are subject to additional collateral requirements since March 2017

. However, many entities now choose to clear voluntarily via a CCP, even in the absence of a regulatory requirement, because of the cost and/or risk mitigation benefits

.

The expansion in CCP activity is set to continue in the coming years. Mandatory clearing obligations are likely for additional asset classes

and the incentives to mitigate risks and costs are likely to lead to even more voluntary clearing. The May 2017 proposal to amend EMIR in a targeted manner, so as to improve its effectiveness and proportionality, will reinforce this trend, by creating further incentives for CCPs to offer central clearing of derivatives to counterparties

. Finally, deeper and more integrated capital markets following on from Capital Markets Union will further increase the need for cross-border clearing in the EU, thus further increasing the importance and the interconnectedness of CCPs within the financial system.

Expanding role of CCPs raises concerns about the need to upgrade supervisory arrangements under EMIR

The growing importance of CCPs in the financial system and the associated concentration of credit risk in these infrastructures have drawn the attention of governments, regulators, supervisors, central banks and market participants.

While the scale and scope of centrally-cleared transactions has expanded, the number of CCPs has remained relatively limited. There are 17 CCPs currently established in the EU, all of which are authorised under EMIR to offer their services within the jurisdiction - although not all CCPs are authorised to clear all asset classes (e.g. only 2 CCPs clear credit derivatives, only 2 CCPs clear inflation derivatives

)

. A further 28 third-country CCPs have been recognised under EMIR's equivalence provisions, allowing them also to offer their services in the EU

. Accordingly, clearing markets are integrated across the EU and are highly concentrated in certain asset classes. They are also highly interconnected

.

While increased clearing via properly regulated and supervised CCPs reinforces systemic stability overall, the concentration of risk makes the failure of a CCP a low-probability but potentially extremely high-impact event. Given the centrality of CCPs to the financial system, the increasing systemic importance of CCPs gives rise to concerns. CCPs have themselves become a source of macro-prudential risk, as their failure could cause significant disruption to the financial system and would have systemic effects. For instance, mass, uncontrolled termination and close-out of contracts cleared by CCPs could lead to liquidity and collateral strains across the market, causing instability in the underlying asset market and the wider financial system. Like some other financial intermediaries, CCPs are also potentially susceptible to “runs” due to clearing members losing confidence in the solvency of a CCP. This could create a liquidity shock for the CCP as it attempts to meet its obligations to return the principal collateral (i.e. initial margin). The impact of a CCP failure due to increased concentration of risk would be amplified by a growing interconnectedness between CCPs both directly and indirectly via their members (usually large global banks) and clients (Table 2 on page 22 illustrates how the majority of global systemically important banks – G-SIBs – are clearing members of most CCPs including the most systemic ones).

In response, and in line with the G20 consensus

, the Commission adopted a proposal for a Regulation on CCP Recovery and Resolution

in November 2016. The objective of this proposal is to ensure that authorities are appropriately prepared to address a failing CCP, safeguarding financial stability and limiting taxpayer costs. In the context of preparing the CCP Recovery and Resolution proposal, attention has been refocused on the supervisory arrangements for EU and third-country CCPs included in EMIR and the extent to which these arrangements can be made more effective five years after adoption of the Regulation.

Supervisory arrangements for EU CCPs

Under EMIR, EU CCPs are currently supervised by colleges of national supervisors, the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), relevant members of the European System of Central Banks (ESCB), and other relevant authorities (e.g. supervisors of the largest clearing members, supervisors of certain trading venues and central securities depositories). These colleges can have as many as 20 member authorities and rely on coordination by the home-country authority. These arrangements raise a series of concerns.

-First, the growing concentration of clearing services in a limited number of CCPs, and the increase in cross-border activity which that entails, implies that CCPs in individual Member States are increasingly relevant for the EU financial system as a whole. On this basis, the current supervisory arrangements relying mainly on the home-country authority (e.g. the home-country authority is ultimately responsible for important decisions such as the extension of the authorisation or the approval of outsourcing and interoperability arrangements) must be reconsidered.

-Second, divergent supervisory practices in respect of CCPs (e.g. different conditions for authorisation or model validation processes) across the EU can create risks of regulatory and supervisory arbitrage for CCPs and indirectly for their clearing members or clients. The Commission has drawn attention to these emerging risks and the need for more supervisory convergence in the Commission Communication on CMU of September 2016

and in the public consultation on the operations of the European Supervisory Authorities (ESAs)

, both of which drew attention to the challenges posed by heterogeneous supervisory practices.

-Third, the role of central banks - as issuers of currency - is not adequately reflected in CCP colleges. While the mandates of central banks and supervisors may overlap (in particular in areas such as interoperability, liquidity-risk controls etc.), there is a potential for misalignment when supervisory actions impact on key responsibilities of central banks in areas such as price stability, monetary policy and the payment systems. In crisis situations, such misalignments could amplify the risks to financial stability if the assignment of responsibilities between authorities remains unclear.

Supervisory arrangements for third-country CCPs

Concerns have also arisen in respect of supervisory arrangements for third-country CCPs operating within the EU. Today, a significant amount of financial instruments denominated in the currencies of the Member States are cleared by recognised third-country CCPs. For example, the notional amount outstanding at CME in the US is EUR 1.8 trillion for euro-denominated interest-rate derivatives, and SEK 348 billion for SEK denominated interest-rate derivatives.

-First, the implementation of EMIR’s system of equivalence and recognition has shown some shortcomings from the perspective of EU regulators, supervisors and central banks, in particular as regards ongoing supervision. Once a third-country CCP has been recognised, ESMA typically encounters difficulties in accessing information from the CCP, conducting on-site inspections of the CCP and sharing information with the relevant EU regulators, supervisors and central banks. As a result, there is a risk that CCP practices and/or adjustments to risk management models go undetected, with important financial-stability implications for the EU entities.

-Second, the potential for misalignments between supervisory and central-bank objectives within colleges acquires an additional dimension in the context of third-country CCPs where non-EU authorities are involved.

-Third, as within the EU, there is a risk that changes to the CCP rules and/or regulatory framework in a third-country which could negatively affect the regulatory or supervisory outcomes cannot be taken into account, leading to an un-level playing field between EU and third country CCPs and creating scope for regulatory or supervisory arbitrage. There is currently no mechanism to ensure that the EU is informed automatically of such changes.

Such concerns are likely to become more significant in the coming years, as the global nature of capital markets means that the role played by third-country CCPs is set to expand. With 28 third-country CCPs already recognised by ESMA, a further 12 CCPs from 10 jurisdictions have applied for recognition

and are awaiting a decision of the Commission as regards the equivalence of their regulatory and supervisory regimes.

Finally, and significantly, a substantial volume of euro-denominated derivatives transactions (and other transactions subject to the EU clearing obligation) is currently cleared via CCPs located in the UK. When the UK exits the EU, there will be a discrete shift in the proportion of such transactions being cleared in CCPs outside the EU's jurisdiction - exacerbating the concerns outlined above. This implies significant challenges for safeguarding financial stability in the EU.

In light of these considerations, the Commission adopted a Communication on 4 May 2017 on responding to challenges for critical financial market infrastructures and further developing the Capital Markets Union

, indicating that "further changes [to EMIR] will be necessary to improve the current framework that ensures financial stability and supports the further development and deepening of the Capital Markets Union (CMU)".

Need to assess options to improve current supervisory arrangements

As the EU clearing landscape continues to evolve, the arrangements for crisis prevention and management of CCPs must be as effective as possible. EMIR and the Commission proposal for a Regulation on CCP Recovery and Resolution are important steps in this regard. However, five years after the adoption of EMIR, there is a need to revisit the supervisory arrangements for EU and third-country CCPs in light of the growing size, complexity and cross-border dimension of clearing in the EU and globally. By addressing identified problems at an early stage and establishing clear and coherent supervisory arrangements both for EU and third-country CCPs, the overall stability of the EU financial system should be reinforced and the already low probability (but extremely high-impact) risk of a CCP failure should be lowered even further. The development of the CMU can also be strengthened.

This impact assessment considers the costs and benefits of possible amendments to EMIR so as to address emerging challenges relating to the supervision of CCPs established within the EU and those from third countries. It considers a number of options, including the establishment of a single supervisor for EU CCPs, enhanced supervisory cooperation for EU CCPs, and a system of enhanced implementation of equivalence, additional supervisory requirements and/or location policy for third-country CCPs.

2.BACKGROUND AND POLICY CONTEXT

3.The key role of CCPs in the financial system

CCPs are vital infrastructures for the financial system

CCPs are the "central nerve system" of financial markets. They play a key role in mitigating counterparty credit risk in transactions involving a range of financial instruments, thereby contributing to the reduction of systemic risk. By interposing itself between counterparties to transactions in one or more financial markets, a CCP becomes the buyer to every seller and the seller to every buyer. In this way, CCPs simplify the network of counterparty exposures and lower the average counterparty credit risk through multilateral netting techniques (see Figure 1 below). These techniques mediate exposures and, as a result, central clearing may also mitigate systemic risk by reducing the risk that the default of one or several clearing members propagates from counterparty to counterparty.

Figure 1: Exposures network: from non-centrally cleared to centrally cleared derivatives

Source: BIS

CCPs are located at the heart of a complex network of direct and indirect exposures within the financial system. These exposures relate to a limited number of clearing members of the CCP and a wide array of clients (via the clearing members) and indirect clients (via the clients of clearing members) including small financial companies, investment funds or vehicles, insurance companies and non-financial companies. Direct CCP membership is concentrated in a limited number of entities, as clearing members need to meet minimum criteria, notably in terms of financial robustness, operational capacity and product expertise. A typical clearing member is a large financial institution engaging with CCPs for purposes of trading on their own account and/or on account of their clients.

CCPs clear a wide range of products

Contracts cleared by CCPs can be outright purchases and sales of securities (bonds or equities), Securities Financing Transactions (including repurchase agreements i.e. repos) or financial derivatives, whether listed or OTC. At the end of 2014, almost 40% of CCPs globally were simultaneously offering clearing services for derivatives, cash and SFT markets (see Table 1 for product types cleared by CCP by region). This percentage was 20% in 2006.

Table 1: Product types cleared by CCPs (percentage of CCPs offering clearing for a specific product type in 2014 by jurisdiction)

Source: BIS

Most CCPs operating in the EU also clear several product classes, from listed and OTC financial and commodity derivatives to cash equities, bonds and repos. Annex 2 provides a definition of derivatives and further detail on the different products cleared by CCPs operating in the EU.

4.CCPs have increased in size following post-crisis regulatory reforms - and continue to grow in importance

The financial crisis brought the OTC derivatives market to the forefront of regulatory attention. The insolvency of Lehman Brothers, then a major actor in the OTC derivatives market, revealed important shortcomings in the market. Contracts involving Lehman required many years to unwind, complicating the process of loss allocation and undermining confidence across the financial system as a whole. The G20 took a leading role in seeking to tackle these market shortcomings and in coordinating a global policy response. In September 2009, the G20 leaders agreed that "All standardised OTC derivatives contracts should be […] cleared through central counterparties by end-2012 at latest. OTC derivatives contracts should be reported to trade repositories. Non-centrally cleared contracts should be subject to higher capital requirements

". In this way, G20-inspired reforms have led to the introduction of a clearing obligation for standardised OTC derivatives and created incentives for central clearing; this, in turn, has increased the number of centrally-cleared contracts, in particular for interest-rate and credit derivatives (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Growth of central clearing (notional amounts outstanding by counterparty in percent)

Source: BIS derivatives statistics, November 2016

Regulators across the globe have now transposed the G20 commitment on derivatives into their legal frameworks. In the EU, the adoption of EMIR- together with other pieces of EU legislation, implemented the G20 commitment to increase the resilience of the OTC derivatives market by mandating that certain OTC derivatives be cleared through CCPs. Similar initiatives were undertaken across G20 jurisdictions, including the US (via the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, which was signed into law in July 2010) and several Asian countries (Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore and South Korea). These regulatory reforms have driven a major structural change in the OTC derivatives market and significantly enhanced the systemic importance of CCPs. CCPs are now managing huge volumes of OTC derivatives, which are much more complex instruments than those typically managed by CCPs before the post-crisis reforms.

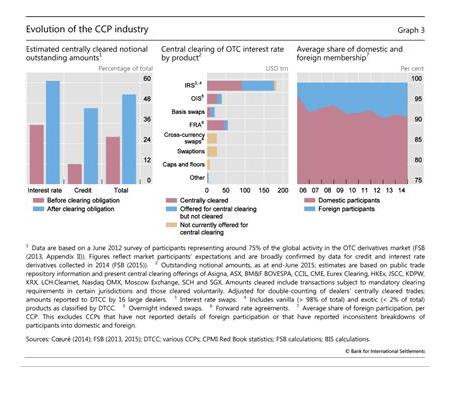

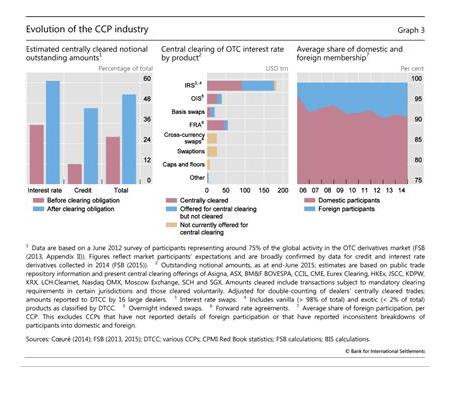

Figure 3: Evolution of the CCP industry

Source: BIS

The gross market value of transactions cleared by CCPs globally is now measured in trillions of dollars. This reflects the introduction of central clearing obligations across asset classes as well as a broad acceptance of the benefits of central clearing by market participants. The notional amounts of centrally cleared OTC derivatives transactions outstanding at the end of December 2016 was estimated at USD 283.5 trillion, of which USD 278.2 trillion was attributable to interest-rate derivatives and USD 4.3 trillion was attributable to credit default swaps. The gross market value of those derivatives represented USD 4.6 trillion and USD 110 billion, respectively. For interest-rate derivatives, 76% of the outstanding notional amount was centrally cleared, with a corresponding share of 44% for credit derivatives. The share of centrally-cleared transactions in other segments of OTC derivatives markets remains negligible (about 1% of the outstanding notional amount for OTC FX derivatives and equity-linked contracts), mainly due to the absence of a central clearing obligation. However, there is a positive trend for central clearing also in these market segments.

Figure 4: Constituents of the OTC derivatives market as of end-June 2016

Source: BIS

Since December 2015, the EU has had requirements in force for certain interest-rate and credit derivatives to be centrally cleared (consistent with similar requirements in other G20 countries); mandatory central clearing for other types of derivatives will follow. In line with global trends, the volume of OTC derivatives transactions, which are centrally cleared, has risen sharply. The evolution in the volume of centrally-cleared interest-rate swap (IRS) transactions is illustrative of this trend. The analysis of EMIR data indicates that the share of cleared OTC trades for IRS has increased steadily since the introduction of the clearing obligation (see Figure 5, which illustrates relative trends in cleared versus non-cleared OTC IRS transactions since January 2015 for two trade repositories DDRL and Regis-TR). The share of centrally-cleared IRS was stable at about 25% in 2015, while it increased to around 35% in the first three quarters of 2016, i.e. after the entry into force of the clearing obligation.

Figure 5: Cleared versus non-cleared outstanding ITC IRS trades for DDRL and Regis-TR (millions of trades, percentage, end-of-month data)

Source: EMIR data, DDRL and Regis-TR

In addition to the clearing obligation, the Commission adopted new regulatory technical standards on margin requirements in October 2016. The objective of these RTS is to further mitigate risk in bilateral clearing by imposing higher collateral requirements (as agreed by G20) and to strengthen the incentive to move to central clearing. The entry into application of these requirements for bilateral transactions follows a phase-in schedule, which started on 4 February 2017 for CCP clearing members and continued on 1 March 2017 for other larger counterparties. Counterparties are required to exchange two types of collateral in the form of margins, contributing to reduce the price differential between bilateral and centrally-cleared transactions and to establish centrally-cleared derivatives prices as the default price. The higher collateral requirement on bilateral transactions has attracted many entities towards central clearing, even though they do not fall within the scope of the EMIR clearing obligation. For instance, in early April 2017, Germany's KfW, a development bank exempt from EMIR, indicated that it would begin centrally clearing its euro-denominated interest-rate derivatives through Deutsche Boerse's Eurex Clearing platform. KfW highlighted that the use of central clearing was justified both by the need to expand the number of its derivatives partners and by the benefits of central clearing from a risk management perspective. This followed a similar move by Germany's sovereign debt agency, Finanzagentur, which began centrally clearing OTC interest-rate derivatives through Eurex in late 2016. This shift towards voluntary central clearing is likely to lead to further increases in the volume of transactions being managed by CCPs.

5.The CCP landscape: concentration, integration and interconnectedness

A concentrated and integrated EU CCP landscape

Most EU CCPs (and other market infrastructures) were originally established to serve national needs. Today, many of these CCPs provide their services across national borders regardless of the currency denomination. For instance, according to recent data, about 75% of centrally-cleared euro-denominated interest-rate derivatives are cleared in the United Kingdom, mostly through SwapClear, a service of LCH.Clearnet. On a daily basis SwapClear clears about USD 3 trillion in interest-rate derivatives, with USD 2 trillion in US dollar-denominated contracts, and EUR 475 billion in euro-denominated contracts as the second largest component. These figures are broadly confirmed by BIS triennial data for 2016. The majority of interest-rate derivatives denominated in EU-currencies other than the euro are also centrally cleared outside of national borders (see section 3.2).

While the volume of transactions cleared in the EU has increased substantially in recent years and is measured in trillions of USD, the number of CCPs remains limited. Currently, there are 17 CCPs established in the EU and authorised under EMIR to offer clearing services in the EU (see Table 3). Some of these EU CCPs are also authorised, recognised or registered by third-country authorities to provide clearing services to non-EU clearing members or trading venues.

Not all EU CCPs are authorised to clear all asset classes (See Figure 6 for the number of EU CCPs authorised to clear products per asset classes between February 2014 and October 2015). In the case of some asset classes, there is only a small number of EU CCP offering clearing services (e.g. only one EU CCP clears credit derivatives, only two EU CCPs clear inflation-rate derivatives).

Figure 6: Number of CCPs authorised to clear products on asset classes

Source: ESMA, Report EU-wide CCP Stress test 2015, 29 April 2016, 2016/658

In addition to EU CCPs, a further 28 third-country CCPs have been recognised under EMIR's equivalence provisions, enabling them to offer their services in the EU. This number is expected to expand as the Commission granted equivalence to six additional third-country CCP regimes in December 2016.

The number of recognised third-country CCPs reflects both the attractiveness of the EU's capital markets and the EU's commitment to integrated financial markets and international standards. Once recognition has been granted, EU and non-EU counterparties may use a non EU-based CCP to clear OTC derivatives as required by EMIR, in the same way as an EU CCP. Moreover, a recognised third-country CCP becomes a Qualifying CCP (QCCP) for the purposes of the Capital Requirements Regulation, thereby attracting preferential risk weightings for associated exposures.

Despite having 45 operating CCPs, the sheer volume of transactions now being centrally cleared means that central clearing markets are generally concentrated in the EU and are highly concentrated in respect of some asset classes.

Regionally integrated markets

In spite of the global nature of the derivatives market, , most CCPs operate mainly as regional or national hubs based on the currencies of the instruments they clear. The exceptions are a few CCPs offering services for a broad range of products to a wide spectrum of clearing members and clients. These 'global' CCPs can, however, also be characterised as regional (or even national) hubs for certain instruments which they clear. As a result, the derivatives market tends to be highly concentrated within regional jurisdictions with instruments being traded and cleared by and between local participants in local CCPs.

As illustrated in a study conducted by ISDA over the period 2013-2015, regulatory initiatives can also reinforce an existing "regional bias" in clearing for a given derivatives market. The study considers the impact on cross-border transactions of the introduction of a requirement for electronic trading platforms, which provide access to US persons, to register with the US Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) and comply with Swap Execution Facilities (SEF) rules from 2 October 2013. The first derivatives products were mandated to trade on these platforms from 15 February 2014 under a process known as made-available-to-trade (MAT). As a result, all US persons are now legally required to trade MAT instruments on SEFs or designated contract markets. The analysis indicates that the cleared euro interest rate swaps market is largely fragmented in US and non-US liquidity pools and that this fragmentation has increased following the entry into force of the SEF rules. This highlights that regulation can strengthen existing trends in the structure of derivatives markets.

Figure 7: The Global Market for Euro IRS: Percentage of Market Share

Figure 8: The Global Market for USD IRS: Percentage of Market Share

Source: ISDA

The analysis also indicates that while the notional volume of euro IRS transactions between European counterparties has increased, the notional volume of trades between European and US counterparties has fallen, both on an absolute basis and in percentage terms. This suggests that the regulatory changes have led to a regional shift in the trading patterns of both EU and US market participants.

A high degree of interconnectedness between CCPs and their clearing members

Partly reflecting market concentration and market integration, CCPs operating within the EU are highly interconnected through a range of channels.

First, CCPs are interconnected via their clearing members. Many of the largest global banks are members of multiple CCPs, illustrating the potential for contagion. For example, 24 globally systemically important banks (G-SIBs) are members of Eurex, BNP Paribas is a member of at least five EU CCPs (see Table 2).

Table 2: Interconnectedness between major CCPs and G-SIBs as of February 2016

Another way to highlight the degree of interconnectedness between market participants active in the OTC derivatives market is to focus on "who trades with whom". The European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) published a paper in September 2016 illustrating the network structure of the OTC derivatives market through a visualisation of the outstanding interest-rate swap (IRS) positions (see Figure 9) in the IRS market. The chart shows that CCPs, big clearing members (referred to as G16 dealers) and banks, which appear in the core of the chart, are connected to a large number of counterparties, with many connections between them, suggesting a high potential for system-wide contagion. This indicates both the central role of CCPs and the importance of client and indirect clearing through the clearing members, as the latter serve as "gateways to clearing" for buy-side counterparties and create interconnections between CCPs and the wider system.

Figure 9: Network of gross notional links between counterparties in a subset of the interest rate swap (IRS) market

Source: Jorge Abad, Iñaki Aldasoro, Christoph Aymanns, Marco D’Errico, Linda Fache Rousová, Peter Hoffmann, Sam Langfield, Martin Neychev, Tarik Roukny, Shedding light on dark markets: First insights from the new EU-wide OTC derivatives dataset, ESRB, Occasional Paper Series No 11, September 2016.

Second, CCPs are interconnected because they clear common trading venues. Some CCPs provide clearing on a cross-border basis to exchanges or other trading venues in Member States other than the Member State in which they are established. For example, Eurex Clearing AG (established in Germany) clears the Irish Stock Exchange, Börse Berlin is cleared by the LCH Ltd (established in the UK), LCH S.A (established in France), EuroCCP (established in the Netherlands) and SIX x-clear (established in Switzerland). Participants on the London Stock Exchange are offered a choice of clearing services from LCH Ltd., EuroCCP and SIX x-clear for all traded instruments (except Polish and Spanish instruments, which are cleared by EuroCCP and LCH Ltd., and US instruments, which are cleared by EuroCCP). European Commodity Clearing established in Germany clears commodity markets across the EU and elsewhere.

Third, CCPs can be interconnected via so-called interoperability arrangements (see Figure 10) which allow clearing members of one CCP to clear transactions with clearing members of another CCP. This is the case for EuroCCP, LCH Ltd. and SIX x-clear in various equities markets, for LCH S.A. and CC&G (established in Italy) in various bond markets and for LCH Ltd. and SIX x-clear in some markets for exchange traded derivatives. In addition, KELER CCP (established in Hungary) is a clearing member of the European Commodity Clearing and offers access to clearing at ECC to its own clearing members.

Figure 10: Central Clearing with and without interoperability

Source: Nicholas Garvin, Central Counterparty Interoperability, Reserve Bank of Australia, Bulletin | JUNE Quarter 2012, page 64

Risks to financial stability

CCPs were originally designed to facilitate trading in securities and not as “macro-prudential institutions” with a responsibility to improve the safety and soundness of the broader financial system. However, as the OTC derivatives market has grown and mandatory clearing of these instruments has become a feature of regulation, some CCPs have become sufficiently large and interconnected to be systemically important. The economies of scale (due to netting and diversification benefits) attached to central clearing favour the use of a small number of large CCPs, resulting in a significant risk concentration in these infrastructures. The financial resources of such large CCPs are, however, not unlimited. One sufficiently severe shock (or a collection of multiple defaults of clearing members) could potentially threaten their viability. Their financial soundness is therefore essential to ensuring the stability of the entire financial system.

A CCP default would typically follow unforeseen losses as a result of simultaneous default of several of its members. The trigger could be either from a member's insolvency, or its insufficient liquidity to meet a margin (or delivery) settlement obligation. The subsequent knock-on effects could be quite far-reaching. The link between CCPs and systemic risk is addressed in a commentary prepared for the ESRB and published in 2013. The commentary suggests that the risk concentration within clearing members themselves would build up due to the need for indirect access to CCPs. In addition, the large banking groups tend to exhibit significant overlaps across many CCP memberships. Thus, a significant cross-section of CCPs and their members could be affected by a globally systemic event. To address the potential contagion risks between CCPs as a result of interoperability arrangements, EMIR specifically requires CCPs to identify and manage the risks arising from such arrangements. It also provides for these arrangements to be assessed and approved by the competent authorities.

If the defaulter's margin with the CCP is insufficient to cover its obligation, the CCP would have to call upon other financial resources, including its equity and default fund and its ability to call on additional capital contributions by members. If all of these resources are exhausted as a result of the default of one or more members, the CCP would default on its obligations to other members and their clients. The failure of a large CCP could possibly result in spreading financial contagion, as all major financial institutions will be interconnected via direct and indirect linkages to CCPs.

As noted above, a CCP could also default due to a lack of liquidity. Just like other financial intermediaries, CCPs are potentially susceptible to ‘runs’ due to a loss of confidence in their solvency. This could create a liquidity shock for the CCP as it attempts to return collateral. For instance, in the event of a member default, the CCP will have to make a timely payment to those owed variation margin payments. This will require the CCP to liquidate the collateral of defaulters, and perhaps some of its own assets. The CCP may also attempt to borrow to meet its obligations. If such collateral sales and borrowings occur during stressed market conditions (which is when a large member default is most likely), the CCP may be unable to raise sufficient funds to meet its obligations.

The cessation of operations of a CCP would deprive market participants of certain basic functions, such as trade processing, thereby entailing the shutdown of entire markets with knock-on effects.

So, CCPs are key players in a very large, heavily integrated and interconnected market for central clearing of OTC derivatives, which can lead to systemic risk

Since the crisis, the market for centrally-cleared derivatives has expanded sharply with a limited number of CCPs resulting in heavy concentration (particularly for some asset classes) and high levels of interconnectedness. These trends are set to continue. Further mandatory clearing obligations are likely to follow and incentives to mitigate risks and costs are likely to lead to more voluntary central clearing. The May 2017 proposal to amend EMIR in a targeted manner to improve its effectiveness and proportionality will also contribute to these trends, by creating further incentives for CCPs to offer central clearing of derivatives to counterparties in order to make the financial system even safer. Finally, deeper and more integrated capital markets following on from Capital Markets Union are likely to lead to a further increase in cross-border activity in the EU, thus further increasing the interconnectedness of the financial system and CCPs.

While the migration of OTC derivatives transactions to CCPs has reduced the risk of another episode like the Lehman failure, new risks have emerged that are linked to the concentration of so many transactions within a limited number of separate but interconnected infrastructures. Concentration of OTC derivatives clearing is driven by the nature of the business, which is characterised by low marginal cost, economies of scale and a high premium on liquidity - all of which promote the emergence of large market providers. Concentration risk in CCPs is not a problem per se, but it necessitates that CCPs are superior risk managers, (i.e. acting as risk poolers rather than gross risk takers) and that they are adequately regulated and supervised.

6.The current supervisory arrangements under EMIR

EMIR establishes different supervisory models for CCPs operating in the EU, depending on whether the CCP is established in the EU or outside of the EU.

Supervisory arrangements for CCPs established in the EU

EMIR introduced new supervisory arrangements to ensure that CCPs established in the EU are subject to adequate supervision. Under EMIR, CCP supervision is mainly conducted at national level (see figure 11 below). This was a conscious choice of the co-legislators at the time of EMIR's adoption in 2012, in recognition of the fact that any fiscal responsibility for managing a failing CCP remains at national level, even though the impact of a CCP failure immediately could have a cross-border reach (at EU level and even beyond). This is illustrated in the following table that compares stressed exposure amounts for LCH Clearnet Ltd and clearing volumes for the SwapClear service with the GDP and public debt figures of UK and FR respectively.

Table 3 – SwapClear clearing volumes and LCH Clearnet Ltd stressed exposures compared to UK and FR GDP and public debt

|

Benchmark

|

LCH Clearnet Ltd

|

SwapClear service

|

|

|

GDP (2015)

|

Public debt (2015)

|

CPMI-IOSCO report (Q1 2016)

|

Notional amounts outstanding (as of 12 May 2017)

|

|

|

UK

|

EUR 2.58 trillion

|

EUR 2.27 trillion

|

Total default resources for OTC IR derivatives

|

EUR 4.04 billion

|

All products

|

EUR 269.5 trillion

|

|

|

FR

|

EUR 2.18 trillion

|

EUR 2.10 trillion

|

Peak stressed LGD (12 past months)

|

EUR 2.46 billion

|

Interest Rate Swaps

|

EUR 128.5 trillion

|

|

Sources: LCH Clearnet Ltd – SwapClear website; TradingEconomics.com

On this basis, EMIR tasks home supervisors with the full supervision of CCPs established in their Member State, including (1) the authorisation of the relevant CCP(s); and (2) the organisation of a cooperation and information-sharing framework among other Member State authorities (supervisors and central banks) within supervisory colleges. Meanwhile, ESMA is allocated responsibility for promoting supervisory convergence and cross-sector consistency, mediating conflicts between authorities within the supervisory college, addressing any breaches of EU law, and creating a harmonised set of prudential, organisational and conduct of business requirements for CCPs ensuring the adequate coverage of their exposures to risks. Considering the inherent interconnectedness of the clearing business, EMIR recognises the need for other Member-State authorities and ESMA to have a role in the authorisation of a CCP, alongside the home authority (either in a voting capacity for Member-States authorities or in a non-voting advisory capacity for ESMA). A blocking mechanism is provided for, granting binding mediation powers to ESMA if the home authority fails to obtain a favourable opinion of the supervisory college before the authorisation of a CCP. The other Member State authorities also act in different capacities within the supervisory colleges, being responsible for the supervision of clearing members, CSDs or trading venues, being responsible for the supervision of CCPs with which interoperability arrangements have been signed.

EMIR refers specifically to the role of central banks when participating in colleges, both as overseer of the CCP and as central bank of issue. The role of central banks is closely linked to the tasks attributed to the ESCB under the Treaty to promote the smooth operation of payments systems. The participation of CBIs in a supervisory college is determined by the currency of denomination of the financial instruments cleared. For financial instruments denominated in the currency of one of the Member States of the EU, the CBI is always a member of the European System of Central Banks (ESCB), i.e. the ECB for the Member States whose currency is the euro or the relevant national central bank for Member States whose currency is not the euro. In order to ensure safe and sound transmission channels for monetary policy, the CBI has a genuine interest in promoting the smooth operation of payment, clearing and settlement systems, also considering that monetary policy operations typically take the form of central bank credit collateralised by securities. In particular, the CBI should be in a position to safeguard price stability, which is closely related to financial stability. In this context the CBI has also normally extensive expertise in these areas.

Figure 11: Current supervisory arrangements for EU CCPs

Source: European Commission services

While the current EMIR supervisory arrangements for CCPs established in the EU recognise the need for several authorities to be involved in supervision, the relative complexity of these arrangements and the tension between national and cross-border supervision raise concerns about whether the assignment of responsibilities between authorities and their ability to react swiftly to developments is sufficient to mitigate the risks related to the increasing concentration, integration and interconnectedness of the CCP ecosystem.

Supervisory arrangements for third-country CCPs

In line with G20 commitments and international standards, EMIR enables a mechanism for CCPs based outside of the EU to provide clearing services to EU counterparties. This aims to promote safe cross-border OTC derivative transactions, avoid market fragmentation and regulatory arbitrage.

This mechanism is based on a three-step approach. First, the third-country CCP needs to apply to ESMA for recognition. Second, the European Commission must examine the legal and supervisory framework of the third country in which the CCP is established in order to assess whether it is equivalent with the requirements laid down in EMIR. There are three main criteria to consider: (i) whether the legal and supervisory arrangements of a third country ensure that CCPs authorised in that third country comply with legally binding requirements that are equivalent to the requirements laid down in Title IV of EMIR; (ii) whether those CCPs are subject to effective supervision and enforcement in the third country on an ongoing basis; and (iii) whether the legal framework of the third country provides for an effective equivalent system for the recognition of CCPs authorised under third-country legal regimes. Based on the outcome of this assessment, the European Commission may adopt an equivalence decision. Third, ESMA must then be able to assess whether the applying third-country CCP may be recognised. When a third-country CCP has been recognised, the third-country supervisory authorities remain primarily responsible for supervision, while ESMA engages in cooperation with them, on the basis of bespoke cooperation arrangements (see Figure 12). In contrast to the supervisory arrangements for CCPs established in the EU, no specific competences are envisaged for national authorities (supervisors or CBIs) with regard to the recognition or supervision of third-country CCPs.

Figure 12: Current supervisory arrangements for recognised third-country CCPs

Source: European Commission services

Other jurisdictions can have different approaches with a more extensive application of their requirements to CCPs established in a third country. For example in the US, the Commodity and Exchange Act and CFTC regulations require that third-country CCPs wishing to provide clearing services to trading venues established in the US must be registered with the CFTC and comply with CFTC regulations. In addition, third-country CCPs that clear derivatives with a sufficient nexus to US commerce must also register with the CFTC.

EMIR's supervisory arrangements for third-country CCPs are therefore markedly different both from the supervisory system for CCPs established in the EU, since they do not provide a role for national supervisors or CBIs, and from the approach of other major countries towards relations with third-countries, as they do not establish requirements allowing direct supervision over third-country CCPs. In addition, while the starting point of the EMIR supervisory architecture for CCPs established in the EU is that all EU CCPs are of a systemic nature regardless of their size or of their activities, the third-country regime under EMIR does not take into account whether third-country CCPs are systemic, as long as the related third-country regime complies with the equivalence criteria laid down under EMIR. The combination of these elements raises concerns about whether the current equivalence and recognition process for third-country CCPs is sufficiently robust to mitigate the potential systemic risks associated with the increasing size, concentration, integration and interconnectedness of CCPs.

7.Relevant international standards and EU initiatives on CCPs

Relevant international standards for CCPs are insufficient to mitigate systemic risk

Following the G20 Pittsburgh summit in 2009, as part of an overall move to enhance the strength of the global financial system, the Financial Stability Board (FSB) was established to coordinate at international level the work of national competent authorities and international standard setting bodies and to develop and promote the implementation of effective regulatory, supervisory and other financial sector policies in the interest of financial stability.

While the reforms of derivatives markets seek to enhance financial stability by increased use of central clearing, fully realising the benefits of central clearing requires CCPs to be subject to strong regulatory, oversight and supervisory requirements. International standard setters, led by the FSB, are therefore working on several initiatives with regard to CCPs. In particular, in 2015, global standard-setting bodies launched a comprehensive work plan on CCP resilience, recovery, resolution and clearing interdependencies to further enhance the existing framework.

With regard to CCP resilience, in April 2012, the then Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (CPMI) and Settlement Systems (CPSS) and the Technical Committee of the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) published the Principles for Financial Markets Infrastructures

(PFMIs). According to the PFMIs, all systemically important financial market infrastructures (FMIs) should have comprehensive and effective recovery plans. The PFMI raises minimum requirements, provides more detailed guidance and broadens the scope of the standards to cover new risk management areas for FMIs, including additional detailed guidance for CCPs. CPMI-IOSCO is currently working on providing additional guidance on CCP resilience, work that is yet to be completed and not meant to add any further requirements to the 2012 PFMIs.

In October 2014, CPMI and IOSCO published a report on Recovery of Financial Market Infrastructures, which is based on the PFMI and provides guidance to FMIs, including CCPs, on how to develop plans to enable them to recover from threats to their viability and financial strength that might prevent them from continuing to provide critical services to their participants and the markets they serve. It also provides guidance to relevant authorities in carrying out their responsibilities associated with the development and implementation of recovery plans.

Following the financial crisis and G20 commitments to end ‘too big to fail’, the FSB published its Key Attributes of effective resolution regimes for financial institutions (Key Attributes) in October 2011. Additional guidance on the application of the Key Attributes to FMIs was published in October 2014, in the form of an Annex. The FSB has led work to develop further guidance on CCP resolution, due to be finalised by the time of the G20 Summit in July 2017. In addition, crisis management groups (CMGs) are being established for CCPs that are systemically important in more than one jurisdiction.

Additional initiatives of relevance also include the work of CPMI-IOSCO on the requirements for qualitative and quantitative disclosure by CCPs, and the joint work of the Basel Committee on Bank Supervision (BCBS), CPMI and IOSCO on prudential requirements for the exposure of banks to CCPs.

EMIR complies with these international standards and implements them into EU law. The Commission's proposal on CCP Recovery and Resolution also aims to integrate standards on recovery and resolution into the EU framework. However, while international standards help coordinate the policy response of various jurisdictions to global and cross-border risks, there is no guarantee that these standards will be sufficient to address the increasing concentration, integration and interconnectedness of the CCP ecosystem, as long as these are not implemented and enforced consistently by jurisdictions. This is particularly true in the context of the withdrawal of the UK from the EU.

Related EU initiatives on CCPs do not address EMIR's supervisory arrangements

EMIR is the only piece of EU legislation establishing direct requirements over CCPs. As such, it is the primary tool governing the EU's supervisory arrangements for CCPs established within or outside of the EU.

The Commission has recently presented two proposals amending EMIR, which aim to address the systemic importance of CCPs on the one hand, and to promote further the use of central clearing while keeping costs at a minimum for market participants on the other hand. While these proposals are consistent with the ultimate objective of EMIR to reduce systemic risk in the OTC derivatives market, neither of them specifically addresses the current supervisory arrangements under EMIR.

First, the Commission's proposal

for a Regulation on CCP Recovery and Resolution adopted in November 2016 aims to ensure that, in the unlikely scenario where CCPs face severe distress or failure, the critical functions of CCPs are preserved while maintaining financial stability and helping to avoid that costs associated with the restructuring and the resolution of failing CCPs fall on taxpayers. While the proposal seeks to ensure that EU and national authorities are appropriately prepared to address a failing CCP, it mainly focuses on amendments to help lower and mitigate the systemic risk related to the failure of CCPs, through the introduction of recovery and resolution measures. The proposal does not include, however, amendments to enhance the ongoing supervision of CCPs operating in the EU in a non-crisis scenario. Such amendments could nevertheless contribute to strengthening the ability of EU and national authorities to prevent the failure of CCPs, in line with the objective of the CCP Recovery and Resolution proposal to diminish further the probability of such an event.

Second, the Commission's proposal for targeted amendments to EMIR

, adopted in May 2017, seeks to simplify certain EMIR requirements and make them more proportionate in order to reduce excessive costs for market participants, without compromising financial stability. This proposal is part of the Commission's 2016 Regulatory Fitness and Performance programme (REFIT) to ensure that EU legislation delivers results for citizens and businesses effectively and at minimum cost. As such, the proposal focuses on issues where targeted amendments can help alleviate existing burdens without compromising EMIR's objective of increasing financial stability. However, by tackling some of the costs and obstacles associated with access to clearing, this proposal should provide further incentives for market participants to use central clearing – again reinforcing the importance of CCPs within the financial system.

Third, other relevant EU initiatives relate to the broader European Union framework, and may therefore not be sufficiently specific to address the systemic nature of CCPs. They consist of various initiatives related to the overall EU financial services supervisory architecture, including the Commission's ongoing efforts to further develop the Capital Markets Union (CMU), which call for further supervisory convergence at EU level to support the development of deeper and better integrated capital markets, and the review of the operations of the European Supervisory Authorities (ESAs), which explores how to strengthen and improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the ESAs. Another initiative of relevance is the Staff Working Document (SWD) on equivalence

, which sets out DG FISMA's experience with the implementation and enforcement of third-country provisions in EU financial legislation. While providing examples of best practices on how to promote an effective and ongoing supervision of third-country entities within the EU's framework on relations with third countries, the SWD mainly takes stock of the current state of play across EU financial legislation and does not offer concrete recommendations on the possible way forward for enhancing the supervision of third-country CCPs.

There is an urgent need for the EU act to enhance supervision in order to mitigate the systemic risks related to CCPs operating in the EU

As the EU clearing landscape continues to evolve and the role of CCPs expands further in the future, the arrangements for crisis prevention and management of CCPs must be as effective as possible. International standard-setting bodies are working towards guidelines to address the inherent cross-border nature of CCPs. The Commission's proposal for a Regulation on CCP Recovery and Resolution is also an important step in this regard, together with other horizontal EU initiatives to improve supervisory convergence at EU level.

However, five years after the adoption of EMIR, there is an urgent need to revisit the supervisory arrangements for EU and third-country CCPs in light of the growing size, interconnectedness and cross-border dimension of clearing in the EU and globally. First, the growth of CCPs in scale and significance is expected to accelerate as recent initiatives, including the application of clearing obligations, the margin requirements for uncleared derivatives and the REFIT proposal to make EMIR more efficient and more proportionate, will further promote the shift towards central clearing. Likewise, the EU's exposure to third-country CCP risks is expected to grow as the interconnected nature of CCPs increases further, and as additional third-country CCPs apply for recognition. The EU's exposure to third-country CCP risks will also be exacerbated by the foreseen withdrawal of the UK from the EU in 2019, as this will lead to a shift of risk from within to outside the EU.

It is therefore necessary for the EU to move swiftly to address the concerns relating to any shortcomings in the supervisory arrangements for CCPs. By acting at an early stage, the overall stability of the EU financial system will be reinforced and the already low probability (but extremely high-impact) risk of a CCP failure will be lowered even further. The development of the CMU will also be strengthened.

8.PROBLEM DEFINITION

This section outlines how the assessment of the effectiveness and efficiency of EMIR's current supervisory arrangements for CCPs established in the EU and recognised third-country CCPs has been carried out.

Based on the analysis in the previous section and on the outcome of the evaluation of the functioning of the colleges presented in Annex 6, this section identifies the problems with current supervisory arrangements and considers the key issues to be addressed in the proposal to amend EMIR. The problems include: (1) incoherence in arrangements for the supervision of CCPs established in the EU and notably the need for an adequate reflection of the responsibilities of the CBI; and (2) the insufficient mitigation of risks relating to the operation of recognised third-country CCPs.

9.Analysis of current EMIR supervisory arrangements

The impact assessment report analyses the performance of the current supervisory arrangements of EMIR, based on the previous formal EMIR Review evaluation and additional available material, without a formal evaluation under the Better Regulation principles.

A formal evaluation of EMIR accompanied the EMIR REFIT proposal adopted by the Commission in May 2017. That evaluation focused mainly on the objectives of EMIR to increase transparency, reduce counterparty credit risk and mitigate the operational risks associated with OTC derivatives.

According to the impact assessment accompanying the 2012 Commission's proposal on EMIR, the general objective of the supervisory requirements for CCPs under EMIR is to increase the safety and efficiency of CCPs established in the EU. The related operational objective is to remove obstacles to the cross-border provision of CCP services in the EU, while the specific objective is to ensure a level-playing field for the provision of CCP services, by promoting supervisory convergence. However, that impact assessment did not consider the third-country dimension of EMIR's supervisory arrangements, meaning that an evaluation of EMIR's third-country supervisory regime for equivalence and recognition cannot be carried out against its initial objectives.

The observation period of how the EMIR supervisory architecture, and more specifically the supervisory colleges, works in practice, has been relatively short. Within the EU, while the first colleges of supervisors were established in 2013, the authorisation of the 17 CCPs established in the EU spanned from the first half of 2014 (Nasdaq OMX Clearing AB) until September 2016 (ICE Clear Europe Limited), with the authorisation of an 18th CCP in Croatia still pending. Likewise, the recognition of the first third-country CCPs started as recently as the first half of 2015, following the adoption of corresponding equivalence decisions in October 2014 (for the CCP regimes of Japan, Australia, Hong Kong and Singapore).

While for these reasons no formal evaluation beyond the EMIR Review evaluation has been carried out, this impact assessment report provides an analysis of the extent to which the existing EMIR supervisory arrangements for CCPs established inside and outside the EU have met their objective of ensuring a level-playing field for the provision of CCP services in an effective and efficient way, while at the same time being coherent, relevant and providing EU added-value. This analysis is largely based on the outcome of two peer reviews on the functioning of the supervisory colleges under EMIR conducted by ESMA in 2015 and 2016. In addition, this builds on input by ESMA assessing the current EMIR third-country equivalence and recognition regime as part of a report prepared for the Commission in the context of the review of EMIR. The main findings of the peer reviews carried out by ESMA are presented in Annex 6, while ESMA's assessment of the current recognition process under EMIR is presented in Annex 4. On the basis of these analyses, of additional feedback from stakeholders available in Annex 4, and of Commission research, the following preliminary findings can be presented.

Regarding the effectiveness of the EMIR supervisory arrangements applicable to CCPs established in the EU, practical experience suggests that the cooperation between members of the colleges in their current structure have allowed the views of supervisors of different actors involved in central clearing to be represented, thereby contributing to the objectives of supervisory convergence and a level playing field amongst CCPs established in the EU. However, there are concerns about the consistency of CCP supervision across Member States, suggesting room for a more effective approach to cross-border CCP supervision. In particular the degree of cooperation between members of the colleges varies significantly depending on the role of the college in the decision-making process. While during the authorisation process, "ESMA observed that in general the CCP colleges facilitated two-way cooperation: on the one hand, the chairing NCAs received good and constructive input from the college members which fed into their risk assessments; while on the other hand, college members received the information they required in order to vote on the adoption of the joint opinion.", a reduced level of cooperation occurs where there is no need for such an opinion. Thus, ESMA sees a "risk that following authorisation CCP colleges may become simply a mechanism for the exchange of information, rather than an effective supervisory tool." In addition, preliminary observations suggest that: (i) different college members participate to different degrees in college discussions; and (ii) the supervisory approaches of NCAs vary to a significant extent even in cases involving comparable CCPs. Common templates provided by ESMA to support supervisory convergence between NCAs have failed to solve that problem, because NCAs exercise their discretion differently. There is therefore room for improvement to help strengthen the consistency of CCP supervision at EU level, improve level playing field in the EU and achieve more effective supervisory convergence.

On the effectiveness of supervision of third-country CCPs, the current arrangements have allowed ESMA to recognise 28 third-country CCPs to provide clearing services to EU counterparties. This is in line with the G20's objectives to promote cross-border arrangements. At the same time, most respondents to the EMIR consultation (mainly companies from the financial sector and industry associations) considered that the EMIR equivalence regime for third-country CCPs has de facto created a situation where the requirements for CCPs established in the EU are heavier than third-country CCPs, leading to an un-level playing field which is detrimental to the former. ESMA also highlighted that the EMIR approach regarding third-country CCPs is extremely open, with full reliance on third country rules and supervisory arrangements, while the majority of third-country jurisdictions consider third-country CCPs as systemically relevant infrastructures and apply to them closer scrutiny. ESMA argued that, although the current EMIR approach should be a model in terms of mutual reliance, if the EU remains the only jurisdiction relying extensively on third country rules and authorities, this might put it at risk and does not benefit CCPs established in the EU.

Regarding efficiency, a majority of respondents to the EMIR consultation supported the objective of ensuring a level playing field between CCPs established in the EU by promoting a homogeneous application of EMIR. At the same time, they pointed to the length of the approval processes, underlining that, in certain cases, the timeline for approval could be postponed indefinitely by the NCA, giving rise to legal uncertainty. Certain respondents also pointed to the need for greater transparency in the functioning of colleges, not only regarding CCPs for the authorisation and extension of services processes but also regarding users of CCPs in order to allow them to get more visibility of the authorisation process and its consequences. Moreover, several authorities and industry participants, and market infrastructure operators asked for more clarity in the process and timeframe for the authorisation and extension of services provided by CCPs. Respondents suggested that EMIR should clarify the modalities for the college process, in particular the roles and responsibilities of different college members. There is therefore room for improvement, in particular in relation to a more streamlined supervision of CCPs established in the EU. This could contribute to a more efficient collaboration between national and EU supervisors, thereby avoiding the duplication of supervisory tasks and reducing the corresponding allocation of time and resources.

Regarding the current supervisory regime for third-country CCPs, industry associations that responded to EMIR consultation indicated that the Commission takes too long to complete its equivalence assessments. ESMA also raised a series of concerns about the efficiency of the process of recognition of third-country CCPs. First, it argued that the process is rigid and burdensome, as demonstrated by the limited number of recognition decisions taken in 2015. Second, it pointed out that the recognition of third country CCPs imposes a significant administrative burden on ESMA.

Regarding relevance, the supervisory arrangements of EMIR remain integral to international efforts to increase the stability of the global OTC derivatives market, while facilitating cross-border deference arrangements between jurisdictions. EMIR's supervisory arrangements also ensure that financial markets continue to play their role in contributing to sustainable, long-term growth to further deepen the internal market in the interests of consumers and businesses, as part of the Commission's efforts to support investments, growth and jobs.

As described in Section 2, the supervisory arrangements of EMIR are coherent with other pieces of EU legislation that aim to: (i) address the systemic importance of CCPs; (ii) promote further the use of central clearing, and (iii) enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of EU-level supervision, both within and outside the EU.

Finally, in terms of the EU added value, the supervisory arrangements of EMIR covered a gap by introducing a new mechanism facilitating supervisory convergence at EU level in order to address the systemic risks of CCPs offering clearing services to EU counterparties.

10.Inconsistency in the arrangements for supervision of EU-based CCPs and role of the CBI

Concerns have arisen in respect of supervisory arrangements for CCPs established in the EU. Annexes 4 and 6 provide detailed feedback from stakeholders and public authorities on the current EMIR supervisory arrangements for CCPs established in the EU.

The central supervisory role of home NCAs does not adequately reflect the increasingly pan-European nature of EU CCPs

Under EMIR, authorisation of a CCP relates to the EU as whole. Authorised CCPs are currently supervised by colleges comprising the home-supervisor, ESMA, relevant members of the ESCB, and other relevant authorities (e.g. supervisors of the largest clearing members, supervisors of certain trading venues and central securities depositories). The central role in these colleges is played by the home-supervisor, which coordinates the other participant authorities. However, the increasing scale and scope of EU CCPs, their cross-border integration, concentration and interconnectedness in the financial system as described earlier point to shortcomings in this arrangement.

In contrast to the concentration and interconnection in the market for central clearing, CCP-related supervisory powers across the EU are fragmented. Table 4 below highlights the variations in CCP supervisory responsibilities across Member States. Numbers in brackets in the second column refer to the number of CCPs established in that Member State. It illustrates that a majority of Member States rely on their financial-market authority to supervise EU CCPs, while others rely on central banks, and a few combine both types of authorities.

Table 4: Competent authority for the supervision of EU CCPs under EMIR as reported to ESMA

|

Designated Competent Authority

|

Member State (number of EU CCPs in that country)

|

Number of Member States with the particular supervisory model

|

|

Central Bank

|

CZ (0), IE (0), LT (0), HU (1),

NL (2), SK (0), UK (4)

|

7

|

|

Financial Market Authority

|

BU (0), DK (0), DE (2)*, EE (0), EL (1), ES (1), HR (1), CY (0), LU (0), MT (0), AT (1), PL (1), PT (1), RO (0), SL (0), SE (1)

|

16

|

|

Combination of the two above

|

BE (0), IT (1), FR (1)**

|

3

|

|

Other model

|

FI (0)***

|

1

|

* Plus central bank (supervisory function) that performs some supervisory tasks on behalf of the financial market authority

** Plus the prudential authority (ACPR).

*** Combination of central bank and ministry of finance.

Source: ESMA