EUR-Lex Access to European Union law

This document is an excerpt from the EUR-Lex website

Document 52005IE0135

Opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee on Employment policy: the role of the EESC following the enlargement of the EU and from the point of view of the Lisbon Process

Opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee on Employment policy: the role of the EESC following the enlargement of the EU and from the point of view of the Lisbon Process

Opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee on Employment policy: the role of the EESC following the enlargement of the EU and from the point of view of the Lisbon Process

OJ C 221, 8.9.2005, p. 94–107

(ES, CS, DA, DE, ET, EL, EN, FR, IT, LV, LT, HU, NL, PL, PT, SK, SL, FI, SV)

|

8.9.2005 |

EN |

Official Journal of the European Union |

C 221/94 |

Opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee on Employment policy: the role of the EESC following the enlargement of the EU and from the point of view of the Lisbon Process

(2005/C 221/18)

On 1 July 2004 the Economic and Social Committee, acting under Rule 29(2) of its Rules of Procedure, decided to draw up an opinion on Employment policy: the role of the EESC following the enlargement of the EU and from the point of view of the Lisbon Process.

The Section for Employment, Social Affairs and Citizenship, which was responsible for preparing the Committee's work on the subject, adopted its opinion on 20 January 2005. The rapporteur was Mr Greif.

At its 414th plenary session on 9 and 10 February (meeting of 9 February 2005), the European Economic and Social Committee adopted the following opinion by 138 votes to 1, with 4 abstentions:

1. Introduction

|

1.1 |

In March 2000, the Lisbon European Council launched an exacting reform programme with ambitious growth and employment objectives. The aim was to combine enhanced competitiveness in a knowledge-based economy and sustainable job-creating economic growth on the one hand, with better quality of employment and greater social cohesion on the other. The reform package, which enjoyed broad support, fuelled the hope that putting it into practice on the ground would draw Europe's grassroots citizens much closer to the venture of EU enlargement. |

|

1.2 |

Given the current economic position, there is a risk that the 2010 targets — particularly in relation to employment — will not be met, thereby threatening the credibility of the entire process. The European Economic and Social Committee feels that the only way to defuse this credibility issue is to give the public confidence in the efforts of political players to secure the consistent implementation of the Lisbon strategy with its matching, equal-status objectives (enhanced competitiveness, economic growth with more and better jobs, greater social cohesion and sustainable environmental development). |

|

1.3 |

The Committee firmly believes that what the Lisbon strategy needs is not a new agenda, but rather a policy approach that also seeks to achieve the set targets through appropriate action, particularly at the level of the Member States. In issuing this own-initiative opinion and building on its earlier opinion on Improving the implementation of the Lisbon strategy (1), the Committee is seeking to identify key employment challenges and submit recommendations for the further implementation of the process from now until 2010. |

2. The Lisbon strategy mid-term review: Europe is far from achieving the goal of more and better jobs.

|

2.1 |

In the Lisbon strategy, enhanced competitiveness and sustainable economic growth are considered to be key instruments enabling more and better jobs to be created in Europe and to put social security systems on a more solid foundation as a protection against poverty and exclusion. The Committee feels that this holistic approach is one of the Lisbon strategy's notable strengths. |

|

2.2 |

On the jobs front, Lisbon was designed to breath new life into the European employment strategy, to strengthen the role of pro-active employment policy in tackling poverty, to foster entrepreneurship as a key engine of growth and employment and to increase labour force participation across the EU through quantitative targets.

|

|

2.3 |

Lisbon did not, however, merely raise the prospect of ‘more jobs’ but also introduced the notion that performance and competitiveness were to be achieved above all by fostering innovation and improving the quality of employment. Investment in human resources, research, technology and innovation was therefore given the same priority as labour market and structural policies. Accordingly, further quantitative targets were set, including increasing per capita investment in human resources and promoting lifelong learning (securing a further-training take-up rate of 12.5 % among all adults of working age, halving the number of 18- to-24 year olds not in further education and training), raising the R&D rate to 3 % of GDP (with two-thirds of the investments coming from the private sector) and improving childcare provision (providing childcare facilities for 33 % of 0- to 3-year-olds and 90 % of children up to mandatory school age). |

|

2.4 |

Despite some initial successes, Europe at the beginning of 2005 is still far from reaching its ambitious targets. The European economy is now in its third successive year of very low and substantially below-par growth. Overall economic recovery is hesitant and, given high oil prices and massive global imbalances, highly vulnerable. As a sobering mid-term balance, it is virtually certain that the Lisbon employment targets will not be met by 2010. |

|

2.5 |

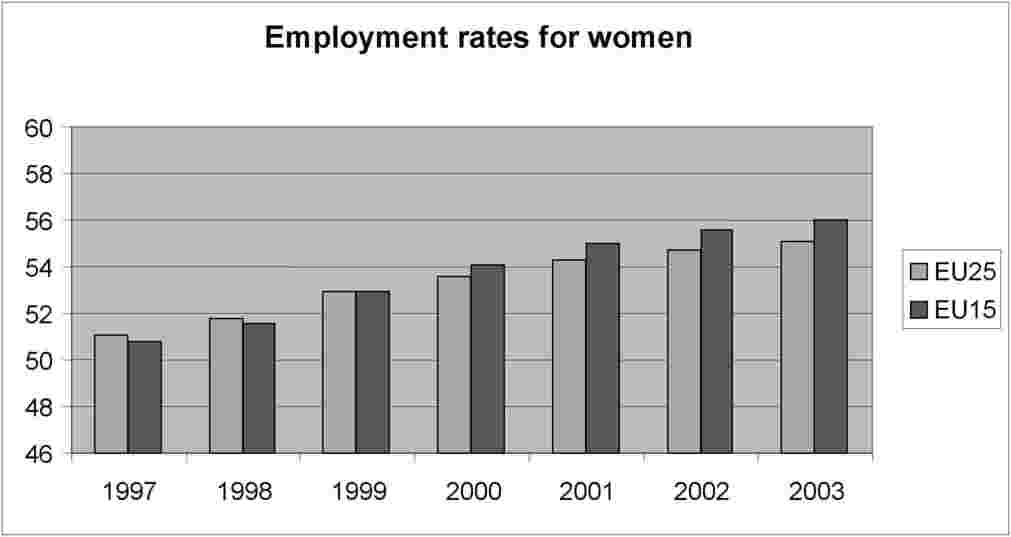

All three graphs 1-3 (see below: in each case the highest figure represents the Lisbon goal) indicate how unlikely it is that the Lisbon targets will be realised by 2010.

Graphs 1 — 3: Developments in the Lisbon employment objectives (4)

|

|

2.6 |

Meeting the 70 % Lisbon target would necessitate the creation, by 2010, of some 15 million new jobs in the EU-15 and 22 million in the EU-25. That works out at more than 3 million new jobs a year, as many as were created in the EU-15 in 2000, the best year for employment for over a decade. |

|

2.7 |

EU enlargement is generating economic momentum across Europe but is also a key factor in employment trends. As the graphs above show, employment rates in the new Member States are lagging considerably behind those in the EU-15. Even in the late 1990s, that was not the case, especially for women. On the other hand, current economic development in the new Member States is considerably more dynamic, with annual growth rates sometimes running at well over 4 %. The EU must pay special attention to the needs of the new Member States when framing its employment strategy so that these countries too can meet the Community-wide employment targets. In doing so, the convergence criteria for any desired accession to the euro-zone must be such that they foster rather than hinder economic development and employment growth. The Committee has already addressed this issue in depth with representatives from organised civil society from the new Member States in the joint consultative committee. |

3. Employment policy must mean more than labour market structural reform

|

3.1. |

The weak employment position outlined above is doubtless due in no small measure to economic developments. The Lisbon objectives were devised on the presumption of 3 % annual average growth in real GDP. Instead of the expected upswing, however, the economic environment has deteriorated rapidly since 2000. Growth rates in subsequent years have been extremely low: 1.7 % in 2001, 1 % in 2002 and just 0.8 % in 2003. |

|

3.2. |

Against that background, it is clear that the employment targets cannot be met unless we succeed in ushering in a sustainable economic upswing. Appropriate framework conditions which are conducive not only to external demand, but also to internal demand must be established, in order to enhance the potential for growth and to achieve full employment. On that score, the Committee has, on a number of occasions recently, pointed out the need for a ‘sound macroeconomic background’ at European level. This includes, above all, a macropolicy which gives Member States scope to take cyclical action in economic and finance policy during times of economic stagnation, and the appropriate room for manoeuvre during times of economic growth.

|

|

3.3. |

The slowdown in growth of the past few years (after a growth rate that still reached 3 % in the EU-15 in 2000) was due mainly to macroeconomic factors, and less so to structural ones. The Committee has therefore repeatedly urged that this fact be reflected in the recommendations of the European broad economic policy guidelines (6). The main elements of demand — consumption and investments (both private and public) — need to be given a substantial boost so as to offset Europe's weak buying power. Europe — with a positive trade balance and increasing exports — is without doubt competitive. What is stagnating, however, is internal demand. Structural reforms can only succeed in a more favourable macroeconomic climate. Wages must not only be seen as a supply-side cost factor, but also as a major determinant of demand and therefore of the market prospects for small and medium-sized enterprises, which are tied to a specific location. As the example of Germany shows, marked wage moderation may well strengthen the supply side, but at the same time stymies any economic recovery by weakening demand. Although wage negotiations are influenced by several factors, it should be noted that gearing real wage increases to national rises in productivity across the economy as a whole generates adequate growth in demand at the same time as underpinning the European Central Bank's focus on stability. This approach to economic policy can help Europe achieve sustained, stability-oriented economic growth. |

|

3.4. |

Over the past few years, European policy recommendations have been dominated by the view that the problem with the European labour market lies in structural factors (such as social partners' wage policies, rigid labour market regulation, excessively short working time and an immobile, inflexible workforce). Indeed, employment policy in most Member States has, over the past few years, focused on these factors. In contrast, moves to foster employability, eliminate skills deficits and get disadvantaged groups into work have clearly been left by the wayside. |

|

3.5. |

In this connection, the Committee has frequently pointed out that cuts in social benefits and workers' pay — and insufficient investment in human resources — weaken internal demand, thereby aggravating the economic difficulties and impairing the development of labour productivity. Moreover, this single-ended supply-side approach runs counter to the holistic Lisbon targets themselves, not least as regards increasing the productivity and quality of employment. At all events, any labour market policy that pays too little attention to upskilling, and forces skilled, but unemployed people to take low-skilled jobs will have a negative impact on labour productivity. The Committee believes that the only appropriate way forward is to secure a parallel increase in employment and in labour productivity, as recently advocated by the Commission. Of course, some low-skilled jobs will also be created. In this context, social and labour legislation will have to be observed, |

|

3.6. |

The current European employment debate focuses on the need to increase employment rates. The Lisbon strategic target is to promote employment as the best way to prevent poverty and exclusion. This requires a strategy for improving the quality of employment, rather than simply creating jobs at any price. Europe's path to full employment must therefore be tied to commensurate wages, social security and high standards of labour law. The EESC calls for greater importance to be attached to the further pursuit of the Lisbon strategy on quality of work, particularly when it is a matter of implementing structural reform measures. |

|

3.7. |

The Committee is most certainly not saying that labour market reforms or reforms in other areas are irrelevant to job creation. To retain the target of creating more and better jobs, however, the Committee does feel, however, that, at the present juncture, the most important thing is to boost the economy and promote sensible structural reforms. That is the only way to raise the impact and acceptance of reforms. Macropolicy and structural reforms must be mutually supportive, not mutually exclusive. |

4. New approaches to employment policy: innovation in business — investment in work — knowledge as a key resource

|

4.1 |

The innovativeness of European enterprises is essential to economic dynamism. Without new, improved products and services, without an increase in productivity, Europe will fall behind economically and in terms of employment policy. Raising productivity also means a change in the working world, not always and immediately with positive effects. But the absence of social and economic innovation undoubtedly leads to a downwards spiral. The consequences of this change for the labour market must be cushioned by accompanying social measures. |

|

4.2 |

Economic growth and a climate for investment are key prerequisites for creating new jobs and retaining existing ones. In the European single market, this is done to a sizeable degree through new businesses and SMEs. (7) Small and micro-businesses are also to a large extent rooted in the local economy and therefore benefit in particular from stable and growing domestic demand. Thus, on employment issues, the Committee has also repeatedly called particular attention to the development of entrepreneurship, policies to enable companies to stay in business, and the promotion of business start-ups (8), which create jobs through innovation. Often, given the need to maintain their position on the market, SMEs in particular are especially innovative. Attention should also be paid to promotion of micro-businesses, enabling them to fully realise their innovative potential, in particular by giving them better access to financing, simplifying administrative aspects of business management, and stepping up training measures. |

|

4.3 |

The Committee has also repeatedly pointed out that people, with their knowledge and skills, constitute the most important resource for innovation and progress in the knowledge society. (9) Europe must find ways to build up its potential in skilled people, science, research and technology — a potential to be converted into marketable new products and services and hence into employment. This calls for a high level of involvement of all population groups in education, a good vocational education, and a smoother transition from higher education to the world of work. The social climate must be developed in such a way that education in self-reliance, and higher education, are not regarded as the privilege of a few. Current OECD studies have once again drawn attention to the weaknesses in the education and training systems of many Member States. (10) The shortage of graduates and of specialists is turning out to be an economic bottleneck and reflects the obstructed access routes to education. Action on training and further training policies is overdue. Where are the necessary investments

|

|

4.4 |

In this context, the EESC has frequently emphasised the importance of taking on general responsibility in the field of training and further training, and thereby also established that investments in schools concern not only the public authorities but also enterprises and individuals themselves, given that lifelong learning benefits employees, businesses and society as a whole (11). Vocational training and lifelong education and further training must not be looked at in isolation, but, on the contrary, must be fundamental elements of workers' career planning. Irrespective of age group or education, there should be adequate motivation and opportunities to take part in further training. The development of skills and of willingness to innovate thus also presupposes corresponding investments at company level in training and further training, and the development of an innovation-promoting enterprise culture. |

|

4.5 |

Nowadays it is not enough for an individual to be creative and willing to learn. The enterprise itself must be willing to learn, i.e. new knowledge must be taken up and converted into marketable products and services. Readiness to innovate is an essential competitive factor. To lay the basis for future innovations, high value must be attributed to science and research. It is a matter of making full use of the potential of the public and private research systems and integrating them effectively. To this end it is extremely important to promote innovation and research, and to raise R&D expenditure to 3 % of GDP in accordance with the Lisbon objective, with two-thirds to come from the private sector (12). Public R&D support should be stepped up at European and national level, not least in growth-promoting key technologies in order to expand the scientific base and increase the lever effect on private-sector R&D investments. At the same time, the Member States and the European Commission should try to use public procurement for new research- and innovation-intensive products and services. |

|

4.6 |

Innovative organisation of work and innovation management, however, are also an issue for small and medium-sized enterprises. Many of these SMEs have developed specific solutions and are global players; others need particular advice on innovation, not only in terms of innovation management but also to establish working environments conducive to learning and to meet the staff's specific skills needs. Networking and knowledge management can help SMEs to tap together into new knowledge potential (13). These cultural obstacles must be overcome to enable SMEs to benefit more from basic research. To be innovative, SMEs also need sound core financing and access to risk capital. In specific terms, that also means that many EU single market directives need to be reviewed for their impact on SMEs, and if necessary improved (e.g. those liberalising the financial markets or on Basle II). |

|

4.7 |

In the EU, a highly productive industrial core is and will continue to be the foundation of economic prosperity. Manufacturers and service providers are mutually dependent. Scope for innovation also means directing research and development specifically to the needs of the knowledge and service society, with the emphasis on exploiting new employment possibilities, not only in traditional areas of manufacturing industry but elsewhere too. As well as promoting state-of-the-art technology, Lisbon also requires an emphasis on the service economy. As a precondition for this, socially related services must be reassessed, pressure on public budgets relieved and the importance for economic development of efficient public administration acknowledged. Key words such as education, mobility, individualisation, standards on population growth, care and health, reconciling family and work commitments, and changing communication and leisure habits indicate an additional new requirement for social and personal but also for commercial services. They are often found at the start of a professional development (14). With this in mind, the EESC has repeatedly drawn attention to the significance of the social economy and the third sector for innovation and employment (15). |

|

4.8 |

Innovation is primarily a matter of people, scope for creativity, skills, knowledge, willingness to learn and work organisation. Critical factors are self-reliance, self-determination and participation rights. In this respect reorganisation of working relations and co-determination structures is of the highest importance. Stable industrial relations promote innovation. Anyone who now seeks to reduce instead of strengthening the representation of interests, the organisation of working relations, and hence the fundamental rights of employees, creates new obstacles to innovation. The Committee therefore notes that the present proposal for a framework directive on the internal market in services should not lead to a reduction in existing social, wage and safety standards. |

5. Change requires a welfare state which is viable in the long-term, an active and preventive labour market policy, and modernisation and improvement of social protection systems

|

5.1 |

Anyone who plucks up courage for innovation and change needs not just their own initiative but also support on the part of society. The willingness to take risks and social security go hand-in-hand with one another. In this respect, many depend on social services to make it possible to approach something new and put it into practice. Innovation goes hand in hand with organisation and social cohesion as an essential feature of the European social model. Admittedly, the welfare state must always take new demands into account. In this respect the EESC is convinced that the Lisbon employment objectives only become attainable if social policy is strengthened as a field of action, and the policy of minimum social provisions is continued as a minimum requirement for harmonising working and living conditions in Europe. This is particularly urgent in the enlarged Union, since welfare standards in the EU continue to fall. |

|

5.2 |

To counteract the risk of competition in social standards, therefore, existing provisions in EU social legislation, particularly in the fields of working conditions, work and health protection, workers' rights, equal treatment of both sexes and protection of individual rights, should be implemented more effectively and developed further. This also applies to questions of working time. |

|

5.3 |

The EESC has already repeatedly addressed (for example in its opinion on Employment support measures prompted by the Employment Taskforce report) necessary and feasible innovations in the following fields (16):

|

|

5.4 |

The Committee attached particular value to the following points:

|

|

5.5 |

In that context, the EESC above all stressed the need to do more to raise the employment rate of women and to remove the obstacles which continue to prevent women entering the labour market, and to tackle consistently the existing inequalities (primarily in remuneration). In view of the fact that greater participation by women in the labour market depends mainly on both men and women reconciling family and work requirements, this specific Lisbon objective must be consistently pursued. The EESC therefore welcomes the call to the Member States to ensure at all levels, including public employment, that day-care facilities for children and others in need of care (such as sick or elderly dependents) are made available to the public at large in sufficient numbers and quality and at a reasonable cost. The Member States should follow the corresponding recommendations of the current employment policy guidelines, by establishing practical objectives and developing corresponding action plans to achieve them. |

|

5.6. |

In addition, when implementing the Lisbon Strategy in relation to employment and social inclusion of all excluded and disadvantaged groups, appropriate attention should be paid to combating discrimination and promoting equal opportunities. Member States should be strongly encouraged to continue to pursue anti-discrimination measures under their National Action Plans. |

|

5.7 |

The expert report on the future of social policy recently noted that the commonly held perception of social protection undermining competitiveness, economic growth and high employment levels is hardly defensible in empirical terms, and that in countries such as Sweden, Denmark, Austria, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, high economic performance goes hand in hand with a high level of social protection (19). The countries which take the lead in competitiveness all make relatively high investments in social policy and the social security systems, and show high employment rates and low poverty rates after social transfers are taken into account. What is important now is the balanced linking of modernisation and improvement of the social security systems to adapt them to current conditions (e.g. demographic trends) while maintaining their social protection functions. In this context, ensuring financial viability in the long term must also take account of the criteria of social fairness, general accessibility and high quality of the services. |

|

5.8 |

In most European countries, social security is funded mainly by contributions from workers and employers. In places these contributions have reached a level which can have a negative effect on job creation.

|

|

5.9 |

Increasing the participation of older workers in the labour market is also one of the Lisbon tasks. According to the Commission, 7 million jobs should be created in order to achieve the aim of 50 %. The EESC has already pointed out that under favourable economic and political conditions in the context of a strategy of active ageing, it regards raising the effective age of exit from the labour market as a reasonable objective in principle. However, many Member States in their pension reforms have made a central point of the simple raising of the legal retirement age, with access to early retirement being increasingly restricted or indeed abolished altogether. Behind this lies the one-sided assumption that the main reason why older workers do not remain longer in employment is the individual wishes of those concerned and the lack of incentives in pension insurance arrangements. Other important aspects are overlooked. Member States should offer incentives to encourage workers, on a voluntary basis, to delay their exit from the labour market within the legal retirement age and also to support companies in organising posts and working conditions accordingly. |

|

5.10 |

In agreement with the high-level groups on employment; on the future of social policy in the enlarged Union; and on the Lisbon strategy for growth and employment, the EESC would argue for approaches like those adopted in certain Member States (Finland and Sweden) which contribute to the quality of work and of further training. For the 55-64 age group to remain in productive employment in the year 2010, a labour market is above all needed that also allows for the employment of older workers; this calls for active planning by all players concerned, including the improvement of skills. To this end, investment in productive further training and preventive measures in the field of health protection and health promotion are necessary in order to maintain employability. However, any policy that seeks to change conditions for older workers comes too late if it starts only with the 40-50 age group. For that reason, it is essential to have in place a human resource management that takes account of age from the very start of employment. There is also a need for models of workplace planning for older staff (especially appropriate working time models which reduce physical and mental stress) (22). |

6. The EESC's policy recommendations

6.1 Dovetailing of content in economic and employment policy coordination

|

— |

Since Lisbon, positive efforts have been made to synchronise employment policy coordination with that of economic policy. There is still a problem with the deficit in the dovetailing of the content, where it must be ensured that employment policy guidelines and the guidelines on economic policy are coherent and — on an equal footing — mutually consistent. |

|

— |

There will be effective coordination between the players (governments, ECB, social partners) only when financial and budgetary policy takes responsibility for growth and employment and becomes one of the essential features of economic policy. |

|

— |

In this context more account should also be taken of the Commission's reform proposals — which also tie in with calls from the high-level expert group on the Lisbon strategy — on steering the Stability and Growth Pact more towards growth including the removal of strategic investments from the deficit calculation. It should be the Council, acting on the Commission's proposals, that defines what should be declared as strategic investment of European interest. |

6.2 Better integration of the social partners and enhancing the value of the macro-economic dialogue

|

— |

This must take place at national and European levels. In that way a pragmatically enhanced macro-economic dialogue can contribute significantly to better governance involving the social partners and taking their views into account, and hence to the overall success of the process. It is the only way in which all those with some responsibility for economic and employment policies can discuss in open debate how a ‘policy mix’ to promote growth and employment can best be achieved in the EU. |

|

— |

At Member State level, appropriate participation of the social partners must be ensured — while taking account of their full autonomy — especially on questions of structural reforms, skills and innovation, but also in debates and at all stages of implementation of the European Employment Strategy (formulation, implementation, evaluation of national action plans) (23). |

6.3 Effective cooperation between the specialised Councils of Ministers

|

— |

For it to be possible to pursue an overall employment strategy successfully in the EU, it is necessary to step up cooperation between the various ‘Lisbon-relevant’ Council of Minister configurations. Particularly necessary is a close intermeshing between the work of the Council of economic and finance ministers and that of the Councils for competitiveness and for employment, social policy, health and consumer protection. |

|

— |

Better coordination of this kind is also especially needed in the preparations for the spring summit: Lisbon is a horizontal process, and should not be left to the ECOFIN Council alone. |

6.4 Macro-policy and structural reforms must complement each other

|

— |

It should be noted that the slowdown in growth of the past few years, after a growth rate that still reached 3 % in the EU-15 in 2000, was due mainly to macroeconomic factors, and less so to structural ones. The recommendations of the European broad economic policy guidelines should take this into account. |

|

— |

There must be a noticeable revival of the demand components — consumption and private and public investment — in order to overcome the weakness of purchasing power in Europe. By building on this, intelligent planning of structural reforms so as to avoid further weakening of internal demand can be combined with an important boost to job creation. |

|

— |

To this end, it is especially important to promote employability, overcome skills deficits and integrate disadvantaged groups in the labour market. |

|

— |

At present, the EU as a whole is able to hold its own in global competition, with a favourable balance of trade, even though growth rates are insufficient. In global competition, Europe needs to play to its strength. After all, it cannot compete with African and Asian countries in terms of low wage costs. Rather, it should continue to set store by a broad-based innovation policy and on the manufacture of quality goods and services with a high added value. |

|

— |

In order for free trade to have a beneficial impact, currency policy should not lead to any distortion in the prices of traded goods, and the division of tasks between all trading countries should be such as to permit wages to rise in step with productivity. Neither of these conditions has yet been met, and political players in the EU should make them a priority. |

|

— |

The EESC calls for greater importance to be attached to the further pursuit of the Lisbon strategy on quality of work, particularly when it is a matter of implementing structural reform measures. |

6.5 Supporting the job-creating role of SMEs

|

— |

Small and medium-sized enterprises in particular secure economic growth and new jobs in the European single market. Entrepreneurship must therefore be promoted and entrepreneurial potential fully harnessed, not least by giving such companies better access to financing, simplifying administrative aspects of business management, and stepping up training measures. (24) |

|

— |

All businesses which contribute to growth and employment through innovation should be able to benefit from support; this is far more important than the mere proliferation of companies. |

6.6 Optimising implementation in the Member States themselves

|

— |

The Committee agrees with the November 2004 report of the high-level expert group on the Lisbon strategy chaired by Mr Wim Kok that, in order to attain the Lisbon objectives, the Member States need to be reminded of their commitments more forcefully than hitherto. The failure to achieve specific objectives has at present hardly any effect on national policy planning. Public pillorying has only a limited effect. |

|

— |

The general employment objectives must be broken down into correspondingly ambitious national objectives, while ensuring greater transparency and wider national debates around a national Lisbon implementation report (or action plan). |

|

— |

Benchmarking should be structured in such a way that the relative position of individual Member States can be presented and meaningful political conclusions can be drawn. |

|

— |

On the basis of their initial figures of 2000, certain Member States must make greater efforts than others to reach the general employment objective set in Lisbon. Those with participation rates of 70 % or above are called upon to do so just as much as those below that rate. To that end more attention should be given to the development of employment, rather than simply comparing rates. |

|

— |

For the process to succeed, truly national reform partnerships adequately involving the social partners — as suggested by the European Council in March 2004 — must be promoted, and the national parliaments must be given a greater share of the responsibility. |

6.7 Taking more account of the enlargement aspect

|

— |

The EU should pay special attention to the needs of the new Member States in planning its employment strategy, so that these countries can also attain the Community-wide employment objectives. |

|

— |

Here too, special attention should be paid to sufficient and effective involvement of the social partners at all stages of the employment strategy. |

|

— |

With a view to these countries' possible entry into the euro zone, the convergence criteria must be so designed that they promote growth and employment rather than hindering them. |

6.8 ‘Lisbonisation’ of the EU budget

|

— |

Achieving the EU employment objectives also requires European growth initiatives, which are not limited to an anticipation of already decided EIB projects. The Sapir Report of 2003 has already provided some important suggestions on short-term budgets. |

|

— |

The Commission document on the financial perspective for 2006-2013 also contains interesting proposals, such as the establishment of a growth adjustment fund. These ideas must be further pursued and every effort made to ensure that the future EU budget can give rise to effective European growth and employment initiatives. |

|

— |

In doing this, it is important to ensure that available resources are used effectively to enable consistent implementation of the Lisbon growth and employment objectives, especially in the enlargement countries. |

6.9 Strengthened dialogue with civil society and role of the EESC

|

— |

The Lisbon process also depends on what people in Europe think of it. The EESC is prepared, in the context of European employment policy, to offer its specialised knowledge and its contribution to full understanding of the Lisbon strategy and its necessary communication to the public. |

|

— |

In this connection, the Committee sees the Lisbon process as one of its key priorities and considers that appropriate internal structures are essential so as to remain in close cooperation with the Commission and other EU bodies and in permanent operational contact with civil society at European level and in the Member States. |

|

— |

Given its expertise and its representative character, the EESC believes it could play a role in drawing up impact assessments, which the Commission intends to place on a systematic footing. As the discussions now taking place have shown, it is essential that draft legislation reflect a plurality of viewpoints and be underpinned in the most rigorous and objective manner. Sending impact assessments to the EESC as a matter of priority and giving it the opportunity to add its comments before the assessments are sent to the European institutions could lead to greater acceptance of European legislative initiatives, in line with the spirit of the Partnership for European Renewal. |

Brussels, 9 February 2005

The President

of the European Economic and Social Committee

Anne-Marie SIGMUND

(1) EESC opinion on Improving the implementation of the Lisbon strategy (rapporteur: Mr Vever, co-rapporteurs: Mr Ehnmark and Mr Simpson) (OJ C 120 of 20.5.2005).

(2) On this point, see the EESC opinion of 16.12.2004 on the Communication from the Commission to the Council, the European Parliament, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on increasing the employment of older workers and delaying the exit from the labour market (rapporteur: Mr Dantin – OJ C 157 of 28.6.2005).

(3) See the Communication from the Commission on Increasing the employment of older workers and delaying the exit from the labour market (COM(2004) 146 final).

(4) Eurostat data are currently only available to 2003. Given very sluggish employment growth, however, the 2004 figures will at best be only marginally higher than those for 2003.

(5) On this point, see, among other things, the EESC own-initiative opinion of 26 February 2004 on budgetary policy and type of investment (rapporteur: Ms Florio) (OJ 322, 25.2.2004, ECO/105).

(6) See inter alia the EESC's opinion of 11.12.2003 on the Broad economic policy guidelines 2003-2005 (rapporteur: Mr Delapina - OJ C 80, 30.3.2004).

(7) See the EESC opinion of 30.6.2004 on the Proposal for a Decision of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Decision 2000/819/EC on a multiannual programme for enterprise and entrepreneurship, and in particular for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (2001-2005) (rapporteur: Mr Dimitriadis – OJ C 302, 7.12.2004); the EESC opinion of 31.3.2004 on the Communication from the Commission to the Council, the European Parliament, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Updating and simplifying the Community acquis (rapporteur: Mr Retureau – OJ C 112, 30.4.2003); and the EESC own-initiative opinion of 18.6.2003 on the role of micro and small enterprises in Europe's economic life and productive fabric (rapporteur: Mr Pezzini – OJ C 220, 16.9.2003).

(8) See also in particular the EESC opinion on the Green Paper on Entrepreneurship in Europe (rapporteur: Mr Butters – OJ C 10, 14.1.2004).

(9) On this point, see, for instance, the current EESC exploratory opinion of 28.10.2004 on Training and productivity (rapporteur: Mr Koryfidis) (CESE 1435/2004).

(10) The PISA 2003: OECD Programme for International Assessment (PISA) is of current relevance.

(11) EESC own-initiative opinion of 26.2.2004 on Employment support measures (rapporteur: Mrs Hornung-Draus, co-rapporteur: Mr Greif) (OJ C 110, 30.4.2004).

(12) On that point, see the EESC opinion of 15.12.2004 on the Communication from the Commission: Science and technology, the key to Europe's future - Guidelines for future European Union policy to support research (rapporteur: Mr Wolf) (OJ C 157 of 28.6.2005).

(13) A joint study by Cambridge University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (USA) revealed that about two-thirds of British small and medium-sized enterprises used higher education institutions as sources of knowledge, compared with one-third of the US respondents. However, only 13 % of British SMEs rated close cooperation with academia as important, compared to 30 % of SMEs in the USA (Financial Times, London, Tuesday 30 November 2004).

(14) See also EESC opinion of 10.12.2003 on the Communication from the Commission to the Council, the European Parliament, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions – Mid-term review of the social policy agenda (SOC 148) – Rapporteur: Mr Jahier (OJ C 80, 30.3.2004), EESC own-initiative opinion of 12.9.2001 on Private not-for-profit social services in the context of services of general interest in Europe (SOC 67) – rapporteur: Mr Bloch-Lainé (OJ C 311, 7.11.2001) and EESC opinion of 2.3.2000 on The Social Economy and the Single Market (INT 29) – Rapporteur: Mr Olsson (OJ C 155, 29.5.2001).

(15) See the report of the high-level group on the future of social policy in the enlarged European Union (May 2004).

(16) EESC own-initiative opinion of 26.2.2004 on Employment support measures (rapporteur: Mrs Hornung-Draus, co-rapporteur: Mr Greif) (OJ C 110, 30.4.2004).

(17) See also: ‘The European Pact for Youth’ introduced at the European Council on 5 November 2004 by France, Germany, Spain and Sweden beside others addressing youth unemployment and social exclusion.

(18) EESC opinion of 10.12.2003 on the Communication from the Commission to the Council, the European Parliament, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on immigration, integration and employment (rapporteur: Mr Pariza Castaños) (OJ C 80, 30.3.2003).

(19) See: European Policy Centre (2004): Lisbon revisited – Finding a new path to European growth (quoted in the May 2004 report of the high-level group on the future of social policy in an enlarged European Union, p. 53).

(20) See the report of the high-level group on the future of social policy in the enlarged European Union (May 2004).

(21) EESC opinion of 1 July 2004 on the Communication from the Commission to the Council, the European Parliament, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Modernising social protection for more and better jobs - a comprehensive approach contributing to making work pay (rapporteur: Ms St. Hill) (OJ C 302, 7.12.2004).

(22) On this point, see the EESC opinion of 16.12.2004 on the Communication from the Commission to the Council, the European Parliament, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on increasing the employment of older workers and delaying the exit from the labour market (rapporteur: Mr Dantin – OJ C 157 of 28.6.2005).

(23) On this point, see the 2004 report on social partner actions in Member States to implement employment guidelines, ETUC, UNICE/UEAPME, 2004.

(24) See the EESC opinions mentioned in footnotes 7 and 8.