EUROPEAN COMMISSION

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Brussels, 24.9.2020

SWD(2020) 380 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

IMPACT ASSESSMENT

Accompanying the document

Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council

on Markets in Crypto-assets and amending Directive (EU) 2019/1937

{COM(2020) 593 final} - {SEC(2020) 306 final} - {SWD(2020) 381 final}

Table of contents

1.Introduction: Political and legal context2

1.1.Political context2

1.2.Market and legal context3

1.2.1.Distributed ledger technology (DLT) and the different types of crypto-assets3

1.2.2.The crypto-asset ecosystem7

1.3.Opportunities and challenges8

2.Problem definition10

2.1.What are the problem drivers?10

2.1.1.Lack of certainty as to whether and how existing EU rules apply (for crypto-assets that could be covered by EU rules)10

2.1.2.Absence of rules at EU level and diverging national rules for crypto-assets that would not be covered by EU rules12

2.2.What are the problems?12

2.2.1.Regulatory obstacles to and gaps in the use of security tokens and DLT in the EU financial services legislation12

2.2.2.Consumer or investor protection risks and risks of fraud 14

2.2.3.Market integrity risks (for unregulated crypto-assets)16

2.2.4.Market fragmentation and risks to the level playing field17

2.2.5.Financial stability and monetary policy risks raised by stablecoins and global stablecoins18

2.3.Consequences19

2.3.1.Missed efficiency gains in the trading and post-trading areas19

2.3.2.Missed financing opportunities for small businesses and companies due to a low level of initial coin offerings and security token offerings22

2.3.3.Missed opportunities in terms of financial inclusion and cheap, fast, efficient payments24

2.4.How will the problem evolve?26

3.Why should the EU act?28

3.1.Legal basis28

3.2.Subsidiarity: Necessity of EU action29

3.3.Subsidiarity: Added value of EU action29

4.Objectives: What is to be achieved?30

4.1.General objectives30

4.2.Specific objectives30

5.What are the available policy options?

5.1.What is the baseline from which options are assessed?

5.2.Description of the policy options

5.2.1.Policy options for crypto-asset that are not currently covered by the EU financial framework for financial services

5.2.2.Policy Options for crypto-assets that may qualify as financial instruments under MiFID II

5.2.3.Policy options for stablecoins and global stablecoins35

6.What are the impacts of the policy options?37

6.1.Policy options for crypto-asset that are not currently covered by the EU financial framework for financial services37

6.2.Impact of policy options for crypto-assets that could qualify as financial instruments under MiFID II42

6.3.Impacts of policy options for stablecoins and global stablecoins48

7.Preferred options55

7.1.Overall impact of preferred options55

7.2.Specific impact: small and medium-sized enterprises60

7.3.Specific impact: Environmental impact60

8.How will actual impacts be monitored and evaluated?

Annex 1: Procedural information67

Annex 2: Stakeholder consultation70

Annex 3: Who is affected and how?78

Annex 4: Problem definition85

Annex 5: Discarded options91

Annex 6: Option 1 for stablecoins and global stablecoins96

1.Introduction: Political and legal context

1.1. Political context

As President von der Leyen stated in her Political Guidelines for the new Commission, it is crucial that Europe can reap all the benefits of the digital age and that it strengthens its industry and innovation capacity in a safe and ethical way. Digitalisation and new technologies are transforming the European financial system and the way it provides financial services to Europe’s businesses and citizens. Two years after the Commission adopted the FinTech Action Plan, the actions set out have largely been implemented. The socio-economic impacts of the COVID-19 crisis have also highlighted the importance of digital finance and the need to allow business to be conducted remotely and through innovative digital technologies, wherever possible.

As part of the Commission’s overarching agenda of making Europe ready for the digital age, the Commission is undertaking considerable work in the area of digital finance in an effort to both enable the financing of the digital transformation and ensuring that the financial sector can make the most of the opportunities the digital age presents and become competitive globally. The digital finance strategy will set out the direction of travel for digital finance in the EU, focussing for example on access to data, artificial intelligence and digital identities. Additionally, as part of the digital finance strategy, the Commission will publish underpinning proposals on crypto-assets, as part of the work on ensuring the EU framework allows for innovation while mitigating the risks, and digital operational resilience, as increased digitalisation means increased cyber threats. As regards blockchain and distributed ledger technology (DLT), the Commission has a stated and confirmed policy interest in developing and promoting the uptake of this transformative technology across sectors, including the financial sector.

Crypto-assets are one of the major blockchain applications for finance. Since the publication of the FinTech Action Plan, the Commission has been examining the opportunities and challenges raised by crypto-assets. In that Action Plan, the Commission mandated the European Banking Authority (EBA) and the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) to assess the applicability and suitability of the existing financial services regulatory framework to crypto-assets. The advice issued in January 2019 clearly pointed out that while some crypto-assets could fall within the scope of EU legislation, effectively applying it to these assets is not always straightforward. Moreover, the advice noted that provisions in existing EU legislation that may inhibit the use of DLT. At the same time, EBA and ESMA underlined that – beyond EU legislation aimed at combating money laundering and terrorism financing - most crypto-assets fall outside the scope of EU financial services legislation and therefore are not subject to provisions on consumer and investor protection and market integrity, among others. In addition, a number of Member States have recently legislated on issues related to crypto-assets leading to market fragmentation.

The inherent cross-border nature of internet-based products and applications and in particular those leveraging distributed networks, such as crypto-assets, require strong international cooperation in order to be regulated properly. The Commission has consistently participated actively in all relevant fora working on crypto-assets over the past years to promote cooperation and a common approach. The Commission continues to follow and participate in the relevant work, done in particular by the FSB and FATF on ‘stablecoins’. The current development of high-level principles by FSB, will form a solid basis for jurisdictions to build potential regulation on and will be taken into account in the EU framework.

A relatively new subset of crypto-assets – the so-called “stablecoins” - has emerged and attracted the attention of both the public and regulators around the world. While the crypto-asset market remains modest in size and does not currently pose a threat to financial stability, this may change with the advent of “stablecoins”, as they seek wider adoption by incorporating features aimed at stabilising their value and by exploiting network effects.

Given the developments in the crypto-asset market in 2019, President Ursula von der Leyen has stressed the need for “a common approach with Member States on cryptocurrencies to ensure we understand how to make the most of the opportunities they create and address the new risks they may pose”. Executive Vice-President Valdis Dombrovskis has also indicated his intention to propose new legislation for a common EU approach on crypto-assets, including “stablecoins”. While acknowledging the risks they may present, the Commission and the Council also jointly declared in December 2019 that they “are committed to put in place the framework that will harness the potential opportunities that some crypto-assets may offer”.

The purpose of this document is to assess the case for action, the objectives, and the impact of different policy options for a European framework for markets in crypto assets, as envisaged by the 2020 Commission work programme.

1.2. Market and legal context

1.2.1.Distributed ledger technology (DLT) and the different types of crypto-assets

Crypto-assets are a type of assets that depend primarily on cryptography and DLT. DLT is essentially records, or ledgers, of electronic transactions, very similar to accounting ledgers. Their uniqueness lies in the fact that they are maintained by a shared or ‘distributed’ network of participants (‘nodes’) and not by a centralised entity. It therefore avoids the downside faced by central storage systems of representing a single point of potential failure. The key aspect of DLT systems is that they allow for the decentralised processing, validation or authentication of transactions or other types of data exchange. Typically, records are stored on the ledger only once the participants have reached consensus.

DLT can be divided into two categories: permission-based and permissionless. Permission-based DLTs are closed systems where only identified participants can propose and validate ledger updates. In permissionless DLTs, any entity can access the database and, depending on the specific validation method used, may be able to contribute to updating the ledger. The bitcoin’s innovation was to build a decentralised network that has no central, trusted authority and is open to anyone. In contrast, most of the DLT platforms being developed for use in the financial sector are permission-based.

Another important feature of distributed ledgers and crypto-assets is the extensive use of cryptography, i.e. computer-based encryption techniques such as public/private keys and hash functions, to store assets and validate transactions. In this context, the public key (and the public address, which is a shorter form of the public key) is publicly known and is essential for identification. They are similar to a user account number. The public address is a balance and can be used for depositing and receiving crypto-assets. The private key (akin to a password needed to unlock a user account) is used for authentication and encryption. It grants a user the right to dispose of the crypto-assets at a given address and is needed to authorise a movement of crypto-assets. Losing the private key is equivalent to losing the right to move assets around, hence the need to save it in a secure location.

Files that are written onto the ledger are given a unique cryptographic signature and will usually be timestamped. This allows participants to view the records in question, providing a verifiable and auditable history of the information stored.

DLT networks and crypto-asset activities are supported by ‘smart contracts’. A smart contract is a piece of software that runs directly on DLT and can replicate a given contract’s terms. It effectively implements the terms of an agreement (e.g. payment terms and conditions) into computational material to automate the execution of contractual obligations. For instance, in the case of an offer of crypto-assets, a smart contract can guarantee that the funds will be returned to investors if the offer does not reach the minimum subscription target.

Thousands of crypto-assets have been issued since bitcoin was launched in 2009. In February 2020, there were more than 5,000 crypto-assets worldwide. There is also a wide variety of crypto-assets. There is no official categorisation of crypto-assets in use in the EU or at international level. However, a commonly used classification comprises four main categories of crypto-assets:

·Payment/exchange/currency tokens (often referred as virtual currencies or crypto-currencies). These tokens are used as means of exchange (e.g. to enable the buying or selling of goods/services by someone other than the token issuer). They can also held for investment purposes, even it is not their intended function. Examples of payment tokens include Bitcoin or Litecoin. The “stablecoins” are a relatively new form of payment tokens with particular features aimed at stabilising their value. “Stablecoins” are typically backed by real assets or funds (such as short-term government bonds, fiat currencies…) or by other crypto-assets. They can also take the form of algorithmic “stablecoins” (with algorithm being used as a way to stabilise volatility in the value of the coin).

·Investment tokens may provide rights related to companies (e.g. in the form of ownership rights and/or entitlements similar to dividends).

·Utility tokens have two main functions. Some of them enable access to a specific current or prospective service or good (similar to a voucher). Some are issued to reward operators for maintaining the DLT, for validating and recording transactions. Like payment and investment tokens, some utility tokens can be traded on secondary markets. One example of utility token is Filecoin.

·Hybrid tokens have features at issuance that enable their use for more than one purpose.

Some crypto-assets could already be covered by EU financial services legislation, but the majority of them would not be. When considering whether EU financial regulation applies to crypto-assets, an important question is whether the crypto-asset in question constitutes a ‘financial instrument’ or ‘electronic money’.

Some crypto-assets, especially some “investment tokens” or some “stablecoins”, could qualify as “financial instruments” under the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID II). Under MiFID II, “financial instruments” are inter alia ‘transferable securities’ (such as shares, bonds and any other securities giving the right to acquire or sell any such transferable securities), ‘money market instruments’, ‘units in collective investment undertakings’ and various derivative contracts. In so far as a crypto-asset qualifies as a financial instrument under MIFID II, a full set of EU financial rules (including the Prospectus Regulation, the Transparency Directive (TD), the Market Abuse Regulation (MAR), the Short Selling Regulation (SSR), the Central Securities Depositories Regulation (CSDR) and the Settlement Finality Directive (SFD)) are likely to apply to their issuer and/or firms conducting activities related to them.

Other crypto-assets, especially some other types of stablecoin, could qualify as electronic money under the Electronic Money Directive II (EMD2) if they satisfy all elements of the definition, notably by giving users a direct claim on the reserve backing the ‘stablecoin’.

The current EU legal framework on anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) also applies to some providers of services (wallet providers and crypto-to-fiat exchanges) related to ‘virtual currencies’

. The EU AML/CFT framework provides for the registration and supervision of these two types of service providers without regulating them as such. The EBA’s report and advice on crypto assets published in 2019 recommended to have regard to the latest recommendations, standards and guidance issued by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) as part of a holistic review of the need, if any, for action at the EU level to address issues relating to crypto-assets. The new standards adopted by the FATF in October 2018 introduced a definition of virtual asset (which is broader than ‘virtual currency’) and cover services not currently within the scope of the AMLD (notably crypto-to-crypto exchanges and financial services related to an issuer’s offer and/or sale of a virtual asset).

Figure 1: Interactions between EU financial services legislation and the different types of tokens

1.2.2.The crypto-asset ecosystem

The crypto-asset market encompasses a range of activities and different market actors that provide trading and/or intermediation services. Many of these activities and service providers are currently not subject to any regulatory framework on financial services, either at EU level (except for AML/CFT purposes) or national level.

The crypto-asset issuer or sponsor is the organisation that has typically developed the technical specifications of a crypto-asset and defined its features. In some cases, their identity is known, while in others, they are unidentified. Some are still involved in maintaining and improving the crypto-asset’s code and underlying algorithm, while others are not.

Crypto-asset trading platforms act as a marketplace bringing together different crypto-asset users that are either looking to buy or sell crypto-assets. Trading platforms match buyers and sellers directly or through an intermediary. The business model, the range of services offered and the number and type (e.g. crypto-to-fiat or crypto-to-crypto) of trading pairs vary across platforms. Most of the trading platforms currently operating are ‘centralised platforms’ controlled by a central operator. ‘Decentralised platforms’ are a recent phenomenon. They have no central entity and operate through the use of smart contracts. Centralised platforms hold crypto-assets on behalf of their clients, while decentralised platforms do not. Another important distinction is that trade settlement typically occurs on the books of the platform (‘off-chain’) for centralised platforms, and not at each transaction, while it occurs on DLT for decentralised platforms (‘on-chain’).

Crypto-asset brokers/dealers (or exchanges) are entities that offer exchange services for crypto-assets, usually for a fee (i.e. a commission). By providing broker/dealer services, they allow users to sell their crypto-assets for fiat currency or buy new crypto-assets with fiat currency. Some brokers/dealers are pure crypto-to-crypto broker/dealers, which means that they only accept payments in other crypto-assets (for instance, bitcoin). In contrast with trading platforms, exchanges engage in the buying and selling of crypto-assets themselves on own account and act as the counterparty to users.

Crypto-asset wallets are used to store public and private keys and to interact with DLT to allow users to send and receive crypto-assets and monitor their balances. Crypto-asset wallets come in different forms. Some support multiple crypto-assets/DLTs, while others are crypto-asset/DLT-specific. DLT networks generally provide their own wallet functions (e.g. bitcoin or ether). Some wallet providers, for example custodial wallet providers, not only provide their clients with wallets, but also hold their private keys on their behalf. They can also provide an overview of the customers’ transactions.

Information on the number of crypto-asset users is limited. However, some estimates suggest that the user base has expanded from the original tech-savvy community to a broader audience. An online consumer survey seems to suggest that 9% of European individuals would have owned crypto-assets, with huge variations across countries. However, actual figures are likely to be lower. Anecdotal evidence also show that only a limited number of merchants accept payment tokens.

1.3. Opportunities and challenges

The market for crypto-assets remains fractional compared to the market for traditional financial assets. From the peak in January 2018 of around €760 billion, the total market capitalisation of crypto-assets had fallen to around €250 billion by February 2020. The market has historically been prone to leverage, operational risks and high volatility. For instance, following the COVID-19 outbreak, the price of bitcoin dropped significantly (by 42% vs. 19% for the S&P500, from 1 to 16 March 2020), before recovering. Fraud, hacking, thefts, money laundering and cyber incidents have plagued crypto-asset markets as many crypto-asset trading platforms, exchanges/brokers/dealers and wallet services operate without proper cyber security arrangements.

Almost all national authorities as well as international standard-setting bodies have issued warnings about the risks related to certain crypto-assets, but have also issued positive statements about the potential of the underlying technology (DLT). The European Commission has itself identified DLT as a transformative and foundational technology, including in the financial sector.

Crypto-assets could deliver many benefits to the economy. When used as a means of exchange, payment tokens can enhance competition in the payment market and increase the efficiency of payments (especially cross-border) in terms of cost, speed, security and user-friendliness by limiting the number of intermediaries (such as banks). The issuance of utility tokens can represent a cheaper and less burdensome source of funding for start-ups and early-stage companies by streamlining the capital-raising process and not diluting the ownership capital of entrepreneurs. They also have the potential to connect the token issuer with a wide initial customer base. If they were properly regulated, crypto-assets could also widen investment opportunities for investors (see sections 2.3.1. and 2.3.2). In theory, any asset can be tokenised, and rights to such assets can be represented on a DLT. Such tokenisation processes have the ability to make liquid tangible assets (such as real estate) that would otherwise be illiquid or to facilitate the protection and monetisation of immaterial rights (such as intellectual property and software). Some utility tokens and DLT also offer individuals and companies the possibility to manage data flows and usage, making data portability in real time possible, along with various compensation models.

Crypto-assets and the underlying DLTs also hold great potential for efficiency gains in the ‘traditional’ financial sector. This potential stems mainly from two features of the technology: (i) the ability to record information in a safe and immutable format; and (ii) the capability to make this information accessible in a transparent way to all market participants in the DLT network. The tokenisation of securities (shares or bonds) is an example of potential for growth in the near future. This can lead to increased financing for companies through securities token offerings (STOs) and efficiency gains throughout the value chain, by reducing the need for intermediaries and the automation, resulting in faster, cheaper and frictionless transactions (see section 2.3.1.). A number of promising pilots and use-cases have been developed and tested by market participants across the EU.

Fully deploying DLT in the financial sector is associated with operational challenges. For example, building scale to use DLT massively is challenging given the significant throughput required to cater to the needs of global capital markets. The interoperability between the different DLT networks should also be developed. However, one of the biggest obstacles to unlocking the promise of crypto-assets and DLT in the financial sector remains legal certainty, especially as Member States are beginning to put in place national regimes for crypto-assets. Without certainty, start-ups and developers working in this field will not be able to attract the required investments. For instance, the potential mis-qualification of some utility tokens as “financial instruments” under MiFID2 can be unattractive for developers seeking to innovate. Similarly, without clarity on applicable rules, incumbent financial institutions and market infrastructures are unlikely, and sometimes unable, to pursue developments in this field.

2.Problem definition

Figure 2: Problem tree

Beyond the issues in the figure above, crypto-assets are likely to raise additional issues in terms of tax compliance and data privacy that are not further discussed in this impact assessment. When established market participants operate on private permission-based DLT, robust governance rules and antitrust scrutiny have to prevent restrictions of competition through, for example, exclusionary conduct or entry barriers.

2.1. What are the problem drivers?

2.1.1.Lack of certainty as to whether and how existing EU rules apply (for crypto-assets that could be covered by EU rules)

MiFID II is the central piece of EU securities legislation, providing essential definitions, such as ‘financial instruments’, ‘transferable securities’ or ‘units of collective investment undertaking’. A broader set of rules mentioned above (namely the Prospectus Regulation, MAR, EMIR, SFD, CSDR…) also applies to financial instruments and firms that provide investment services and activities in relation to them. When considering whether existing EU financial regulation applies to crypto-assets, one fundamental question is therefore to determine whether the crypto-asset at stake is a ‘financial instrument’ under MiFID II.

However, the actual classification of a crypto-asset as a financial instrument under MiFID II requires a complex case-by-case analysis and varies depending on how the notion of ‘transferable security’ has been implemented by Member States. Thus, it is possible that the same crypto-asset could be considered as a ‘transferable security’ or another financial instrument in one jurisdiction and not in another, which gives rise to market fragmentation of the EU single market (see Section 2.2.4.). This situation stems from two main factors.

First, the notion of ‘financial instruments’ and in particular of ‘transferable securities’ under MiFID II is harmonised in a broad manner. EU Member States have not always interpreted and implemented the MiFID II Directive in a similar way. ESMA has found that while a majority of national competent authorities (NCAs) (16) have no specific criteria in their national legislation to identify transferable securities in addition to those set out under MiFID II, other NCAs (12) do have such criteria. This results in different interpretations of what constitutes a “transferable security”.

Second, the range of crypto-assets is diverse and many of them have hybrid features. While some investment tokens could be considered as transferable securities or as other financial instruments, payment tokens and utility tokens are more likely to fall outside the scope of the existing EU financial services legislation. The situation can be more complicated for hybrid tokens that exhibit components of two or all three of the archetypes (i.e. hybrid utility/investment tokens, hybrid currency/investment tokens, hybrid currency/investment/utility tokens).

Even where a crypto-asset would qualify as a MiFID II financial instrument (the so-called ‘security tokens’), there is a lack of clarity on how the existing regulatory framework for financial services applies to such assets and services related to them. As the existing regulatory framework was not designed with crypto-assets in mind, NCAs face challenges in interpreting and applying the various requirements under EU law. Those NCAs may therefore diverge in their approach to interpreting and applying existing EU rules. This diverging approach by NCAs creates fragmentation of the market and opportunities for regulatory arbitrage (see Section 2.2.4.).

2.1.2.Absence of rules at EU level and diverging national rules for crypto-assets that would not be covered by EU rules

For crypto-assets that would not be covered by EU financial services legislation, the absence of rules exposes consumers and investors to substantial risks.

In the absence of rules at EU level, three Member States (France, Germany and Malta) have already put in place national regimes that regulate certain aspects of crypto-assets that neither qualify as financial instruments under MIFID II nor as electronic money under EMD2. These regimes differ: (i) rules are optional in France while they are mandatory in Malta and Germany; (ii) the scope of crypto-assets and activities covered differ; (iii) the requirements imposed on issuers or services providers are not the same; and (iv) the measures to ensure market integrity are not equivalent (for more information – see Annex 4).

Other Member States could also consider legislating on crypto-assets and related activities.

2.2. What are the problems?

2.2.1.Regulatory obstacles to and gaps in the use of security tokens and DLT in the EU financial services legislation

As the existing regulatory framework was not designed with DLT in mind, there are provisions in existing legislation that may preclude or limit the use of “security tokens” (i.e. crypto-assets that can qualify as MiFID II financial instruments). While security token issuances have gained traction, there is a lack of market infrastructures using DLT and providing trading, clearing and settlement services for those security tokens. Without a secondary market able to provide liquidity, the primary market for security tokens will never expand in a sustainable way. In a recent survey, 77% of the respondents indicated that the implementation of EU regulation can seriously hinder the development of security tokens. The regulatory issues related to the deployment of security tokens and DLT in the financial services sector can be grouped into five categories.

Some EU rules cannot be applied to DLT and security tokens as they were tailored to ‘traditional’ financial instruments and are not fully technology neutral. This is the case, for instance, for some pre-and post-trade and reporting requirements under the MiFID II/MiFIR framework or for some provisions of the Short Selling Regulation.

Some regulatory gaps exist due to legal, technological and operational specificities related to the use of DLT that are not addressed by existing requirements. There are no reliability and safety requirements imposed on the protocols and smart contracts underpinning security tokens and no specific rules on the resulting liability issues. The underlying technology could also pose some novel forms of cyber risks that are not appropriately addressed by existing rules. While the custody of private keys related to security tokens could be the equivalent of the ‘safekeeping and administration of financial instruments for the account of clients’ service under MiFID II, this activity is not currently regulated at EU level.

Current EU rules prevent the development of financial market infrastructures (such as trading venues, central clearing counterparties (CCPs) and central securities depositaries (CSDs)) based on decentralised exchanges and permissionless DLT networks where activities are not entrusted to a central body. For instance, it is not possible to apply MiFID II or SFD/CSDR rules to them as these rules require the existence of a trading venue operator or a CSD to operate the securities settlement system (and intermediaries, such as brokers/market members and CSD participants/custodians). Given the absence of a central body and intermediaries that would be accountable for applying the rules, decentralised exchanges or permissionless networks cannot be used for security tokens.

Some regulatory uncertainties or obstacles remain for market infrastructures that rely on centralised platforms and permission-based DLT networks. Activities organised by an operator are de facto similar to traditional market infrastructures, such as trading venues or CSDs. However, even when a central body is identifiable, existing legislation does not fit well with the use of DLT by existing market infrastructures. Legal uncertainties is a concern not only for new entrants but also for incumbents authorised market players. For instance, NCAs have reported that the CCP license under EMIR or the CSD license under CSDR would not be adapted to a blockchain environment. It results from an ESMA survey that only an estimated 0.7% of all regulated FinTech firms in the EU perform counterparty clearing or operate a CSD. MiFID rules on trading venues would not be proportionate enough to enable small-scale trading of crypto-assets comparable to shares and bonds. The regulation also prevents the widespread testing of DLT capabilities to determine to what extent the technology is mature enough to replace or complete existing market infrastructures.

Current rules hamper the development of financial market infrastructures that could merge certain activities (trading, clearing, settlement and custody), as it does not take into account the specific benefits of security tokens and DLT. Today, EU financial services legislation follows the lifecycle of a transaction (trading, clearing and settlement). It requires the presence of market intermediaries (i.e. a broker, clearing members, custodians) and market infrastructures (a trading venue, CCP, CSD) and imposes specific requirements on those entities. The use of DLT, with all transactions recorded in a decentralised ledger, can expedite and condense trading, clearing and settlement to nearly real-time and could enable the merger of some activities in the chain. This simplification of the multi-step post-trade process could free up collateral (by reducing the counterparty risks during the settlement period) and improve efficiency (by reducing intermediation, the need for reconciliations and the risks of errors). However, as current rules envisage the performance of these activities by separate legal entities (trading venue, CCP, CSD) on grounds of stability, security and competition, these benefits cannot be sufficiently unlocked. For instance, CSDR (Article 3(2)) requires that the securities admitted to trading on a MiFID II trading venue are recorded with a CSD, while the DLT network could be potentially used as a decentralised version of such depository. By contrast, the use of DLT and security tokens to operate trading, clearing and/or settlement at the same time would raise new risks that are not currently mitigated by EU rules (such as new forms of cyber risks).

2.2.2.Consumer or investor protection risks and risks of fraud (for unregulated crypto-assets)

Where crypto-assets would not qualify as MiFID II financial instruments or as electronic money under EMD2, users who purchase them would not benefit from the guarantees granted by the EU acquis. Yet, those ‘unregulated’ crypto-assets can pose a range of risks to consumers. 72% of the respondents to the public consultation considered the risks to consumer/investor protection as important or very important. Some NCAs and EBA have also been warning consumers about crypto-currency risks since 2013. In 2017, many NCAs and ESMA published warnings about risks inherent to initial coin offerings (ICOs) and crypto-assets. There are three types of risks.

Consumers can purchase unsuitable products without having access to adequate information. Crypto-asset issuances are sometimes accompanied by “white papers” describing the crypto-assets and the ecosystem around it. However, these are not standardised and the quality, transparency and disclosure of risks vary greatlyAs ‘white papers’ often feature exaggerated or misleading information, investors or consumers may not understand the rights associated with crypto-assets and the risks they present. Advertising materials can also overstate the benefits and rarely warn of volatility risks, the fact that consumers can lose their investment, and the lack of regulation. Consumers may therefore suffer large losses as a result of buying crypto-assets that are ill-suited to their needs and risk profile. The high volatility of crypto-assets, which may attract investors, can also lead to substantial losses. Such losses can be amplified when trading platforms offer leveraging trading.

Consumers are also at risk of losses resulting from fraudulent activities and deceptive practices. As the issuance and the provision of services related to crypto-assets are unregulated, this makes the market susceptible to illicit practices. In particular, the promise of high-yield returns makes it easy for fraudsters to attract customers. While fraudulent activity exists across the range of crypto-assets, it is also likely to differ between different types. For instance, the risk of fraud is high in ICOs. Fraud estimates range from 5 to 25% of ICO offeringsand up to 81% depending on the classification. In some cases, the crypto-assets do not exist, the developer disappears just after the ICO or the projects lack appropriate plan or capability to deliver the product or service. Users’ lack of understanding of the intricacies of the underlying technology may also exacerbate the risk of fraud.

Consumers may also be at risk due to the immaturity or failings of service providers. As there are no legal minimum standards on operational risks (including cyber risks), the service providers are not encouraged to put in place appropriate systems and controls, exposing consumers to losses arising from hackers’ attacks, software errors or data loss. Cyber hacks (e.g. to obtain users’ private keys) can put consumers at risk of large losses, as crypto-assets are viewed as high-value targets for theft. Operational issues may also lead to temporary disruptions of systems (due to activity peaks), which can delay or deny consumers’ access to their funds and/or secondary market trading. In periods of disruption, holders of crypto-assets are not able to carry out transactions when they like and may therefore suffer losses due to fluctuations during that period. Some trading platforms or exchanges have stopped trading and users have lost their entire holdings, in some cases. Anecdotal evidence also suggest that service providers can charge high and variable fees that are not properly disclosed to consumers. Solving consumer conflicts can be difficult, especially when the service providers have no internal procedures in place for handling complaints or when they are located outside the EU.

2.2.3.Market integrity risks (for unregulated crypto-assets)

Market integrity, i.e. the fairness or transparency of price formation in financial markets, is an important basis for investor protection and fair competition. The Market Abuse Regulation (MAR) prohibits market abuse (such as insider dealing, the unlawful disclosure of inside information and market manipulation) in relation to financial instruments admitted to trading on an EU trading venue authorised under MiFID II. When crypto-assets do not qualify as MiFID II financial instruments, they fall outside the scope of MAR. However, market integrity may be undermined by the trading of ‘unregulated’ crypto-assets. 71% of respondents to the public consultation considered market integrity risks as important or very important. This may damage confidence and prevent the crypto-asset market from operating effectively.

Some of the behaviours in crypto-asset markets are similar to market-abuse style activities observed in some traditional financial markets. For instance, market manipulation (such as ‘pump and dump’, spoofing, layering) includes false signals about the supply and demand for crypto-assets and distort price formation. Dissemination of false or misleading information by market participants (including by issuers) can lead investors to make misguided investment decisions and cause mispricing and dysfunction in the market.

Crypto-asset markets’ vulnerability to market manipulation is heightened by several factors, such as the novelty and complexity of the technologies used as well as the low liquidity, price volatility and concentration issues (which can lead actors with large holdings to use their dominant position to influence the price). Furthermore, as trading platforms are not subject to transparency requirements or conflicts of interest rules, equal access to information and a fair price are not guaranteed, which raise the risk of market manipulation. Anecdotal evidence also suggest that some large crypto-trading platforms allow investors to conduct wash trades.

Crypto-assets can also pose significant risks to financial integrity, as they may create new opportunities for money laundering, terrorist financing and other illicit financing activities.

2.2.4.Market fragmentation and risks to the level playing field

Where crypto-asset would qualify as financial instruments, market fragmentation, results from divergent national interpretations of how financial services legislation applies to security tokens (i.e. crypto-assets that could qualify as financial instruments) giving rise to regulatory arbitrage. Some market players (e.g. market infrastructures) could be tempted to locate their activities in Member States with a more flexible approach towards the use of DLT, in order to benefit from the EU passporting system. In contrast, market fragmentation can also incentivise issuers or service providers related to crypto-assets to operate in Member States where the definition of ‘financial instruments’ is more restrictive in order to avoid the application of the full financial services framework. As a result, capital could flow to crypto-assets that are equivalent to financial instruments but not treated as such by the Member State where the activity is conducted. This would expose investors to risks due to the lack of adequate regulatory protection.

Beyond the national variations in the implementation of MiFID II and other sectoral legislation, the proliferation of bespoke rules at national level for all or a subset of crypto-assets that do not qualify as ‘financial instruments’ may also lead to a substantial regulatory fragmentation. This market fragmentation also gives rise to regulatory arbitrage and distorts competition in the single market. Service providers or issuers of crypto-assets could operate in, or decide to (re)locate their activities to jurisdictions where crypto-assets are not regulated (beyond the obligations imposed by the AML/CFT framework).

Divergent national rules could create considerable complexity and legal uncertainty for crypto-asset service providers keen to extend operations on a cross-border basis. They could be obliged to adjust their business models according to the rules of separate jurisdictions. An obligation to seek a license from a supervisory authority in different Member States could create additional cost barriers, due to licensing and advisory fees. The proliferation of national approaches is also a concern for crypto-asset issuers, as they are obliged to check the requirements from each national legislation where the crypto-asset is to be marketed, distributed, traded and otherwise used. This makes issuances across the single market costly and difficult.

Market fragmentation may also undermine investor/consumer protection and market integrity in the EU. In most Member States, users of crypto-assets and related services are not protected. In other Member States, bespoke regulation may protect users (through disclosure obligations on the crypto-asset issuances, limits on the maximum amount that can be invested, requirements imposed on service providers). Nevertheless, even when Member States have legislated, the level of investor protection and the measures against market abuse still differ.

2.2.5.Financial stability and monetary policy risks raised by stablecoins and global stablecoins

Currently, 54 ‘stablecoins’ are in existence, of which 24 are operational. Their market capitalisation almost tripled from €1.5 billion in January 2018 to more than €4.3 billion in July 2019. Between January and July 2019, the average volume of ‘stablecoin’ transactions was €13.5 billion per month.

The crypto-asset market (including existing stablecoins) remains small and does not pose a risk to financial stability. However, some stablecoins (backed by a reserve of real assets or fiat currencies) can raise additional challenges in terms of financial stability, monetary policy transmission and monetary sovereignty for three main reasons (Annex 4 provides a detailed analysis of these vulnerabilities).

Different activities within a ‘stablecoin’ arrangement, in particular those related to managing the reserve assets aimed at stabilising their value, increase its interconnectedness with the existing financial system. A ‘stablecoin’ is generally supported by an ecosystem of entities that collectively facilitate its issuance, redemption, the stabilisation mechanism, transfer and retail interface (storage through wallet providers; exchanges and trading platforms). While some of these functions are relevant for all crypto-assets, the existence of the stabilisation mechanism creates two functions specific to asset-backed ‘stablecoins’: (i) managing the reserve of assets and (ii) providing custody for these reserve assets. Runs on a ‘stablecoin’ arrangement could occur if users lose confidence in the issuer or its network, in particular if they realise that the reserve assets are losing value, thereby casting doubts on the value of the stablecoins.

Some ‘stablecoins’ could in the near future become widely used by consumers and reach a global scale. A number of stablecoin initiatives, sponsored by large technology and/or financial firms, have recently emerged (such as Facebook’s crypto-asset, Libra). Thanks to these companies’ large customer base, which may also be cross-border, these new ‘stablecoins’ have the potential to gain a substantial geographical footprint. These are referred to as ‘global stablecoins’. If a global stablecoin is successful in reducing price volatility, it can become widely used as a means of payment and as a store of value. The ECB has estimated the potential size of the reserve of assets backing a multi-currency Libra coin. The Libra Association’s assets under management could range from €152.7 billion in the ‘means of payment’ scenario to about €3 trillion in the most extreme ‘store of value’ scenario (see Annex 4 for more details). If a ‘stablecoin’ arrangement becomes systematically important, it is more likely to raise challenges to financial stability and monetary policy transmission.

Depending on their design, stablecoin arrangements may be particularly difficult to fit into the existing EU framework, leaving the above financial stability risks unaddressed. While some ‘stablecoins’ arrangements confer a claim or redemption rights against the issuer or the underlying assets and could therefore fall into existing regulatory categories, a large number of ‘stablecoins’ do not grant such rights and fall outside existing EU financial services legislation.

2.3. Consequences

2.3.1.Missed efficiency gains in the trading and post-trading areas

In the EU and in Europe, several projects for the creation of security token platforms or in the post-trade area have been identified, but few are already in operation or are limited in scale (testing phase or limited to small and medium-sized companies), for both operational and legal reasons. Given the regulatory constraints, it is difficult for traditional market infrastructures to use DLT rather than continuing running their business as they are used to. Legal obstacles may also prevent new entrants from offering financial services/activities through DLT solutions and competing with traditional players. The need for legal certainty has also continuously been highlighted throughout engagement with stakeholders from the financial industry

Nevertheless, security tokens and DLT hold the potential to transform the way that financial instruments are issued and exchanged. 77% of the respondents to the public consultation considered that DLT could bring substantial benefits in the trading, post-trading and asset management areas, notably in terms of efficiency. Figure 3 summarises these benefits:

Figure 3: Potential benefits of the adoption of DLT in the trade and post-trade area (Euroclear, Oliver Wyman, 2017)

Trading, clearing and settlement of security token transactions could become almost instantaneous, as trade confirmation, affirmation, allocation and settlement could be combined into a single step and reconciliations would become practically superfluous. This would in turn have a number of benefits, including reduced counterparty risk (see Section 2.2.1.), and potentially reduced settlement failures and penalties. DLT could also enable security tokens to be traded beyond current markets hours.

DLT could improve collateral management. Shorter settlement cycles would reduce credit risk for spot trades and the need to mitigate them through central collateral posting. For term transactions (e.g. derivatives) that require the posting of collateral to cover counterparty risk, the use of security tokens and DLT could facilitate reconciliations and accelerate collateral movements. This could ultimately lead to more collateral being available in the market.

DLT may also facilitate the recording and safekeeping of securities. It may improve the traceability of transactions and make ultimate ownership transparent throughout the security life cycle by providing a single ‘golden record’ that would be shared across market participants.

The use of DLT and security tokens could enhance reporting and supervision functions at firms and regulators, by facilitating the collection, consolidation and sharing of data for reporting and risk management purposes. With a DLT, multiple market participants could access a single, accurate and verifiable ledger source in real time. As far as regulators are concerned, they could be granted special access rights to consult or retrieve data stored on DLT ledgers, e.g. details on transactions made by some market participants or their risk exposure levels.

The use of ‘smart contracts’ could improve the enforcement of contract terms and the automation of back office processes, e.g. the processing of some corporate actions (such as dividend or coupon payments). This could in turn reduce errors and legal disputes.

Security tokens and their underlying technology may have certain advantages relative to current systems when it comes to security and resilience to a cyber-attack or a system breakdown. The distributed and shared nature of the system could make it easier to recover both data and processes in the event of an attack (assuming that not all the validating nodes are corrupted at the same time). This could also reduce the need for costly recovery plans. Sophisticated encryption techniques could also provide an additional layer of protection to pools of information stored on DLT compared to existing systems.

The above benefits of DLT could lead to a cost reductions for post-trade processes, including clearing, settlement, custody, registrar and notary services in the medium to long term, once investments have been amortised. Reporting, compliance and risk monitoring costs may decrease as well. The widespread use of DLT gains would imply a significant reduction in costs of around €540 million per year for the EU cash equity market alone. It has been estimated that DLT could reduce bank’s infrastructure costs attributable to cross-border payments, securities trading and regulatory compliance by between $15 to $20 billion per year. Another study considers that a widespread adoption of DLT could remove 50% of the total capital market back and middle office costs of $100 billion per year or more.

2.3.2.Missed financing opportunities for small businesses and companies due to a low level of initial coin offerings and security token offerings

An Initial Coin Offering (ICO) is an operation in which companies and entrepreneurs raise capital for their projects in exchange for crypto-assets that they create. Offers of utility tokens, in particular, represent an innovative method of funding innovative projects that complements other sources, such as crowdfunding, venture capital or a listing of shares on a public market (through an initial public offering – IPO). As well as providing capital to companies that sometimes have no alternative, token sales also put pressure on existing sources of financing to compete and provide better terms for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

There are also specific benefits to ICOs, compared to traditional market-based sources of financing. ICO of utility tokens provide start-ups with a means to pre-sell access (potentially at a discount) to software that is under development. Unlike other means of financing, such tokens are not equity securities and they do not grant any rights to participate in the governance of the company. They therefore allow for SME funding without diluting entrepreneurs’ equity ownership. ICOs can also be carried out without intermediaries, such as banks, which means that the cost of the transaction can be lower. For instance, it has been estimated that ICO costs are around 3% of the funds raised for offerings about $1 million, compared to 10-12% for an IPO. ICOs are also faster to implement compared to IPOs, at least in the current state of play of the crypto-asset market. They are also a more inclusive method of financing compared to other traditional financing mechanisms. An ICO effectively enrols future users, which allows the company to gain appreciation of the demand for the product or service before it becomes operational. The benefit of an ICO is also linked to the liquidity of the token. Unlike venture capital and crowdfunding where the instruments are illiquid, a large number of utility tokens can be traded on a secondary market (even if the liquidity is not guaranteed).

Figure 4: Amount raised by successful ICOs in the EU-28 (source: coinschedule.com and own calculations)

Despite these advantages, the amounts raised in the EU through ICOs are still relatively small and have significantly decreased since the second half of 2018. The financing through ICOs in 2018 (record year) only represented 15% of the funding by venture capital investments (€20.5 billion in 2018).

Security Tokens Offerings (STOs, i.e. offers of crypto-assets that could qualify as financial instruments under MiFID II) have developed in a second step and seem to respond to the need of institutional investors who prefer operating in a regulated environment. However, while there are still very few of STO projects in the EU, there are specific advantages rooted in this type of issuances. These include in particular for the issuers: (i) the automation, via smart contracts, of compliance with regulatory requirements and events affecting the life of securities (corporate actions, like dividend or coupon payments) and lower operational costs; (ii) potential enhanced transparency for issuers on the investors who actually hold the securities; (iii) optimisation of the settlement and delivery processes; (iv) an ability to reach new categories of potential investors and a diversification of the investors.

Figure 5: Amount raised by successful STOs in the EU-28 (source: coinschedule.com and own calculations)

2.3.3.Missed opportunities in terms of financial inclusion and cheap, fast, efficient payments

Domestic payments, in most instances, are increasingly convenient, instantaneous and available 24/7. International cross-border payments, however, remain slower, more expensive and not as transparent, especially for retail payments and remittances. Payment tokens have the potential to enable cheap, fast, efficient and inclusive payments and increase competition by providing alternatives to traditional payment instruments, especially on a cross-border basis. These benefits are potentially higher for ‘stablecoin’ arrangements, if they achieve their goal of price stability and become a reliable store of value and means of payment.

Payment tokens can allow for lower transaction costs, compared to other means of payments (such as payment cards and bank transfers), especially for cross-border transactions. Anecdotal evidence suggest that the costs tend to be less than 1% of the transaction amount, compared to 2-4% for traditional payment instruments used on a cross-border basis. These lower costs are explained by the absence or fewer intermediaries involved in the transaction. The payee in cross-border payment token transactions also benefits from no direct foreign exchange costs. However, a payee that keeps an amount of payment token for future usage, is exposed to exchange rate risk, which can be significant given the huge volatility of some payment tokens. ‘Stablecoins’ could resolve this issue, by reducing the need for converting the payment tokens into fiat currency.

While the cost differential between traditional payments and payment tokens is less pronounced in the Single Euro Payments Areas (SEPA), a clear case for the use of payment tokens is remittances. Flows of money sent by EU residents to non-EU countries amounted to €32.7 billion in 2017, while inflows of money totalled €10.7 billion. Despite political agreement (G7, G20) to lower the cost of remittances, the global average cost is currently 6.79% of the amounts sent. Payment tokens and ‘stablecoins’ offer opportunities to lower such transaction costs. However, this will depend on the fulfilment of several conditions, such as the widespread use of smartphones in emerging economies (as cryptographic wallets require a smartphone) or the acceptance of payment tokens by local merchants. The higher fees charged for traditional means of payments are partly due to the regulatory requirements. Should payment tokens and ‘stablecoin’ arrangement be regaled, compliance costs could diminish their competitive advantage. Payment tokens also hold potential for financial inclusion, as access to wider financial services is often limited to people with access to traditional transaction accounts. Despite the Payment Accounts Directive (PAD) adopted in April 2014 that aims to provide cheap basic bank accounts to EU citizens, the number of unbanked people is around 30 million in the EU. Even if payment tokens require a certain level of financial literacy (especially for older people and those without digital skills), payment tokens could be an alternative way for some individuals to carry out payment transactions.

Transactions using payment tokens can potentially be verified and settled faster than those in fiat currency. The length of the settlement may differ among the various payment tokens, but it is usually less than one hour for decentralised payment tokens and instantaneous for centralised ones. Another advantage of payment tokens is that payments can be validated 24/7, whereas traditional payment systems only have several clearing sessions per day and do not operate during holidays and weekends. These advantages are less significant for EU Member States that have already established instantaneous and 24/7 payment services and for SEPA, where the payee needs to be credited at the latest by the next business day. However, as the speed of verification and settlement does not depend on the location of the sender and receiver, payment tokens still offer advantages compared to credit transfers or card payments, particularly for payments between different currency areas.

Payment tokens can also provide some opportunities in terms of efficiency. One notable advantage is that the validation of payment transactions is distributed over multiple subjects (i.e. validating nodes) and that the use of DLT could improve system resilience, given the lack of a central system which could be subject to outages or failures. Under certain conditions, payment tokens could also improve the traceability and transparency of transactions. Payment tokens may also hold the key to ‘programmable money’ (‘delivery vs. payment’ or ‘invoice vs. payment’), by enabling the functioning of smart contracts. A simple example of programmable money could be blocking the funds for a transaction, which are then automatically released to the recipient only when specific conditions are met (for example the confirmed delivery of goods).

2.4. How will the problem evolve?

Given the lack of (long-term) experience coupled with often abrupt changes in the market (e.g. erratic price swings) and the strong impact of unforeseeable external factors (e.g. regulatory changes in third countries), it is very difficult to predict how these markets and the problems identified will develop. Nevertheless, there are certain assumptions that appear plausible in terms of future developments.

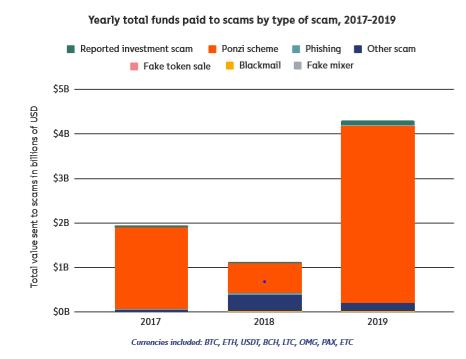

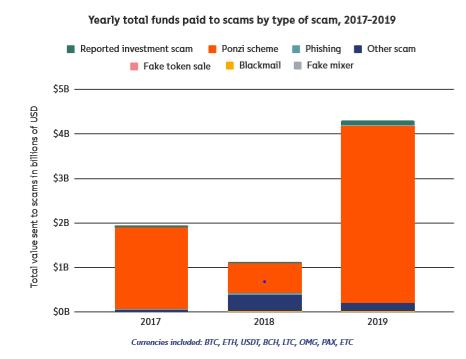

In the absence of regulation, it is likely that crypto-assets falling outside the scope of EU legislation will still give rise to consumer protection and market integrity issues. Most of the crypto-assets have developed outside the regulated space. Supervisory actions at EU and national level (such as warning about the risks of cryptocurrencies or initial coin offerings) have had mixed results in terms of protecting investors or reducing criminal activities. Anecdotal evidence show that fraud remains significant and does not decrease. Cyber-attacks are still a major threat and hacking of wallet providers, exchanges and trading platforms are not uncommon.

Figure 6: Total number of fraud cases in main crypto-asset markets, 2017-2019 (source: chainanalysis)

The benefits offered by crypto-assets (alternative cheap and fast means of payments, funding sources for SMEs, benefits linked to a decentralised data economy) are unlikely to be reaped in the absence of a regulatory framework. The lack of trust in the integrity of crypto-asset markets remains a major hurdle to the widespread use of tokens as a means of exchange or as new investment opportunities for a wider set of investors. Buyers of tokens are therefore usually some retail and other investors (such as family offices) with a high-risk tolerance. High levels of price volatility in the crypto-markets reinforce the general public’s lack of confidence in crypto-asset markets. The lack of trust also allows the most reliable service providers that support crypto-asset markets to charge high prices, which further inhibits liquidity.

To address this, self-regulatory initiatives could emanate from the industry

. However, non-binding principles and the lack of an enforcement mechanism would only achieve limited effects on a market that has so far developed outside the regulatory perimeter. Furthermore, consumer groups are typically not invited to help develop best practice

. Therefore, crypto-asset markets are unlikely to further develop without a comprehensive regulatory framework for issuers and service providers.

Furthermore, in the absence of regulatory action at EU level, more Member States will pursue reforms at national level to address the problems highlighted above, giving rise to further regulatory fragmentation. National regimes would not provide an optimal base for a genuine single market for crypto-assets as service providers would face regulatory hurdles when operating across borders. Because of the cross-border nature of crypto-assets, national legislation aimed at consumer protection would not significantly reduce risks for consumers. The largest trading platforms, exchanges or wallet providers used by consumers in one Member State can be located in another Member State or even outside the EU, where no rule may apply.

‘Stablecoins’ are likely to follow a different path to other crypto-assets. By seeking to stabilise the price of the token, stablecoins could resolve the main shortcoming of others crypto-assets – high volatility. In a short time span, ‘global stablecoins’ can become largely accepted as a means of exchange and used as a store of value. This would introduce a host of challenges, including risks to financial stability, monetary policy transmission and monetary sovereignty. The risks to financial stability would also be amplified if a pioneer project triggers similar initiatives from other BigTech. While becoming systemically important right after their launch, some global “stablecoin” initiatives could also try to be launched outside the EU financial services framework. Promoters of stablecoins could be tempted to follow an ‘act first, seek forgiveness later’ approach towards regulation, by framing their business model in a way that does not fit into any existing regulatory classification.

Crypto-assets that fall within existing EU legislation (those which would qualify as MiFID II financial instruments) face a different set of problems. The market may never meaningfully develop unless the applicable regulatory framework is clarified. As indicated above, DLT systems could have numerous benefits when applied to the issuance, trading and post-trading areas. However, despite significant interest from market participants, there are only very sporadic cases of ‘security token’ issuances to date, and none of the security tokens have been admitted to trading on a trading venue or been recorded with a central securities depositary.

While the industry is attempting to solve the operational issues that DLT systems still face (such as the harmonisation of technical standards and scalability issues), the lack of legal certainty and some provisions of existing EU regulations could act as a barrier to the introduction of this technology and the benefits of DLT may never materialise. EU regulation could require the artificial replication of the traditional steps of the lifecycle of a transaction (such as trading and post-trade activities) and doing so would erode most of the efficiency gains offered by the technology. In fact, it can be assumed that costs will be higher compared to traditional financial instruments given that it would constitute a novel approach (lack of economies of scale, specialist knowhow etc.). As such, the uptake of security tokens is largely dependent on adapting the regulatory requirements in a way that would allow service providers and market infrastructures using DLT to realise the efficiency gains.

If the regulatory challenges related to DLT are resolved in other third country jurisdictions, this may put both the EU financial sectors and EU investors, at a competitive disadvantage. As the financial industry has advocated for more regulatory guidance on the compatibility of DLT with EU financial services legislation for some time, the lack of an EU response could give rise to divergent views and interpretations from NCAs, leading to further market fragmentation and regulatory arbitrage. A recent study has quantified annual DLT spending in financial services at over $1 billion in 2017, with an estimated annual figure of $1.7 billion going forward. However, the investments in the EU could stop if, due to regulatory hurdles, market participants are prevented from shifting from trials and testing to real-world implementation. Ultimately, while not having any direct detrimental impact, it implies that (total) costs of financial transactions will remain higher than necessary in the EU.

3.Why should the EU act?

3.1. Legal basis

The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) confers upon the EU institutions the competence to lay down appropriate provisions that have as their object the establishment and functioning of the internal market (Article 114 TFEU). Depending on the policy option chosen and the specific design of the rules, the appropriate legal base could also be Article 53(1) TFEU on the taking-up and pursuing of activities by self-employed persons, which is used to regulate the access of financial intermediaries to their activities.

3.2. Subsidiarity: Necessity of EU action

For crypto-assets that are covered by EU legislation (mostly those which qualify as financial instruments under MIFID II), a legislative proposal bringing targeted legislative amendments to the existing EU financial services regulatory framework in order to allow for a wider use of DLT could only be carried out through legislative action at EU level. Furthermore, different interpretations on how the current financial services legislation applies to DLT can lead to disparities in terms of investor protection, market integrity and competition across the single market and they can lead to regulatory arbitrage, thus justifying a common EU approach.

For crypto-assets that fall outside the scope of existing EU financial services legislation, some Member States have put in place (or are considering) bespoke national regimes to regulate crypto-assets. As outlined above, these national regimes follow different approaches and can make the cross-border provision of services in relation to crypto-assets difficult. The proliferation of national approaches also poses risks to the level playing field in the single market in terms of investor/consumer protection, market integrity and competition. Furthermore, while some risks are mitigated in the Member States that introduced a bespoke regime on crypto-assets, consumers, investors and market participants in other Member States would remain unprotected against some of the most significant risks posed by crypto-assets (e.g. fraud, cyber-attacks, market manipulation…).

3.3. Subsidiarity: Added value of EU action

Action at EU level would present more advantages compared to actions at national level.

For crypto-assets that are covered by EU regulation (i.e. those that could qualify as ‘financial instruments’ under MiFID II or as ‘e-money’ under EMD2), an action at EU level (either by soft-law measures or regulatory action) would provide clarity on whether and how the EU framework on financial services applies. Enhanced legal certainty by legislation and/or guidance at EU level could facilitate the take-up of primary and secondary markets for ‘security tokens’ across the single market, while ensuring financial stability and a high level of investor protection. By contrast, the proliferation of guidance and interpretations at national level could lead to a fragmentation of the internal market and a distortion of competition.

For crypto-assets that are not currently covered by EU legislation, an action at EU level, such as the creation of an EU regulatory framework, completing also the anti-money laundering existing rules, would set the ground on which a larger cross-border market for crypto-assets and crypto-asset service providers could develop, thereby reaping the full benefits of the single market. An EU regime would significantly reduce the complexity as well as the financial and administrative burdens for all stakeholders, such as the service providers, issuers and investors/users. Harmonising operational requirements on service providers as well as the disclosure requirements imposed on issuers could also bring clear benefits in terms of investor protection and financial stability.

4.Objectives: What is to be achieved?

4.1. General objectives

The objective of this initiative are as follows:

-This initiative aims at providing legal clarity as regards whether and how EU financial services legislation applies to crypto-assets (and related services);

-The initiative should support innovation and fair competition by creating a conducive framework for the issuance of, and the provision of services related to crypto-assets;

-It should ensure a high level of consumer and investor protection and market integrity in the crypto-asset markets;

-It should address financial stability and monetary policy risks that could arise from a wide use of crypto-assets and DLT.

4.2. Specific objectives

The specific objectives of this initiative are as follows:

-Removing regulatory hurdles to the issuance, trading and post-trading of security tokens (i.e. crypto-assets that qualify as financial instruments under MiFID II), while respecting the principle of technological neutrality;

-Increasing the sources of funding for companies through increased Initial Coin Offerings and Securities Tokens Offerings;

-Limiting the risks of fraud, money laundering and illicit practices in the crypto-asset markets;

-Allowing EU consumers and investors to access new investment opportunities or new types of payment instruments, competing with existing ones, to deliver fast, cheap, and efficient payments, in particular for cross-border situations.

5.What are the available policy options?

The policy options analysed in this impact assessment have been grouped into three areas of action: (i) policy options for crypto-assets that are not currently covered by the EU regulation (mainly for certain payment and utility tokens); (ii) policy options for crypto-assets that could qualify as financial instruments under MiFID II; (iii) policy options for ‘stablecoins’ and global ‘stablecoins’. This last category has been assessed separately, as ‘global stablecoins’ can pose new risks to financial stability, compared to other crypto-assets.

Table 7: Summary of the options assessed in the impact assessment

|

Type of crypto-assets

|

Policy options

|

|

Crypto-assets that are currently unregulated at EU level

|

Option 1: Opt-in regime

|

|

|

Option 2: Full harmonisation regime

|

|

Crypto-assets that qualify as financial instruments under MiFID II

|

Option 1: Non-legislative measures

|

|

|

Option 2: Targeted amendments to sectoral legislation

|

|

|

Option 3: Pilot/experimental regime on DLT market infrastructure

|

|

‘Stablecoins’ and global ‘stablecoins’

|

Option 1: Bespoke legislative measures on stablecoins/global stablecoins

|

|

|

Option 2: Bringing stablecoins and global stablecoins under the Electronic Money Directive 2

|

|

|

Option 3: Measures limiting the use of stablecoins and global stablecoins

|

5.1. What is the baseline from which options are assessed?

The baseline is similar to section 2.3. (How will the problem evolve?).

5.2. Description of the policy options

5.2.1.Policy options for crypto-asset that are not currently covered by the EU financial framework for financial services

Option 1: Opt-in regime for unregulated crypto-assets

For crypto-assets that fall outside the EU financial services framework, Option 1 would consist in an optional regime for the issuance of, and services related to, crypto-assets (such as trading platforms, exchanges, wallet providers…). In such a case, crypto-asset issuers and service providers would have the possibility to opt-in to an EU-wide regime if they want to operate throughout the single market. Issuers or service providers that would decline to opt-in would remain unregulated or be subject to national bespoke regimes. The regime would not apply to crypto-assets that may qualify as ‘financial instruments’ under MiFID II or as ‘electronic money’ under EMD2. The opt-in regime would be built on four building blocks.

The first building block would relate to the issuance of crypto-assets. If they opt-in for this regime, issuers would benefit from a passport regime across the single market, allowing them to market and offer their crypto-assets in all Member States. In return, they would be subject to some requirements imposed at EU level. The fundamental requirement imposed on the crypto-asset issuer should be the disclosure of clear, accurate and non-misleading information through an information document/white paper (such as a technical and economic description of the project, the nature of the crypto-assets, the rights or the absence of rights associated with them, the risks they present and finally whether and where they are tradeable). These provisions would apply only to crypto-assets that are issued (i.e. created and then sold by the issuer or his agent, as opposed to those simply awarded to the miners or those that are distributed to the public for free).

Under this option, the issuer would be obliged to create a legal entity or to have a legal representative in the EU that would be accountable to the national competent authority. The issuer could also be subject to further requirements, such as advertising rules ensuring that marketing and promotional materials are not misleading. The issuer managers would also be subject to fitness and probity standards.

The second building block would concern the services related to crypto-assets. Three main categories of services would be in scope: 1) the trading platforms of crypto-assets: 2) the brokerages/exchanges (fiat-to-crypto and crypto-to-crypto) and 3) the custodial wallet providers. Those entities would be subject to the following key requirements, summarised in the table below.

Table 8: Summary of the requirements on crypto-asset service providers

|

Key requirements for all crypto-asset service providers

|

Legal presence in the EU - Governance arrangements (e.g. in terms of operational resilience and ICT security) - Rules on conflicts of interest - Prudential requirements (including capital requirements) – Business continuity requirements - Adequate complaints handling and redress procedures - Reporting requirements (including and beyond AML/CFT requirements) - Liability towards the customers for the crypto-assets given in custody – Segregation of users’ assets from those held on own account - Obligation to keep appropriate records of users’ transactions - Rules, surveillance and enforcement mechanisms to deter potential market abuse - Advertising rules to avoid misleading marketing/promotions – Obligation to provide information in the context of criminal investigations upon requests of national authorities, according to national laws

|

|

Additional requirement for exchanges and trading platforms

|

Obligation to provide a certain degree of pre- and post-trade transparency (bid-offer spreads and transaction volumes, price) - Access to services in an undiscriminating way – Obligation to screen crypto-assets against the risk of fraud

|

|

Additional requirement for trading platforms

|

Adequate rules to ensure fair and orderly trading

|

|

Additional requirement for wallet providers

|

Minimum conditions for their contractual relationship with the consumers/investors

|

The third building block would be consumer protection and market integrity measures. Crypto-asset service providers would have to apply additional measures to ensure investor/consumer protection (such as suitability checks and/or issuing warnings on the risks). A legislative proposal could also integrate measures aimed at preventing market abuse (market manipulation, insider dealings and disclosure of false information) related to crypto-assets when they are traded on a secondary market.