EUROPEAN COMMISSION

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Brussels, 17.5.2018

SWD(2018) 183 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

IMPACT ASSESSMENT

Accompanying the document

Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council

on electronic freight transport information

{COM(2018) 279 final}

{SEC(2018) 231 final}

{SWD(2018) 184 final}

Table of Contents

1Introduction: Political, legal and market context

2Problem definition

2.1What is/are the problems?

2.1.1

Low level of acceptance of electronic freight transport documents by the different market players

2.1.2

Different administrative practices between and within Member States

2.1.3

Why is it a problem?

2.2What are the problem drivers?

2.2.1

A fragmented legal framework concerning the acceptance of electronic freight transport documents/information

2.2.2

Multiple and non-interoperable data exchange systems

2.3How will the problem evolve?

3Why should the EU act?

3.1Legal basis

3.2Subsidiarity: Necessity of EU action

3.3Subsidiarity: Added value of EU action

4Objectives: What is to be achieved?

4.1General and specific objectives

5What are the available policy options?

5.1What is the baseline from which options are assessed?

5.2Policy measures and options

5.3How do the policy options differ

5.3.1

Material scope: transport contracts vs regulatory information evidence

5.3.2

The legal equivalence of the electronic transport contracts and the admissibility as proof of regulatory compliance

5.3.3

The role of international conventions and bilateral agreements with third parties as policy intervention instruments

5.3.4

Technical specifications for implementation

6What are the impacts of the policy options?

6.1 Economic impacts

Use of electronic means for transport information and documentation exchange

Administrative costs for businesses

Compliance costs for businesses

Modal shift and congestion costs

Compliance costs for authorities

Enforcement costs for authorities

Transport costs for transport operators

Internal market impacts

Innovation impacts

6.2 Social impacts – impacts on employment

6.3 Environmental impacts

Emissions

Use of natural resources and energy use efficiency

7How do the options compare?

8Preferred option

9How will actual impacts be monitored and evaluated?

Annex 1: Procedural information

1.Lead DG, Decide Planning/CWP references

2.Organisation and timing

3.Consultation of the RSB

4.Evidence, sources and quality

Annex 2: Stakeholder consultation

1.Introduction

2.Feedback

2.1. Feedback received on the Inception Impact Assessment

2.2. Feedback received during the consultation process

3.Methodology

4.Summary of input

Annex 3: Who is affected and how?

1.An outlook of the preferred option implementation

2.Practical implications of the initiative

3.Summary of costs and benefits

4.Stakeholders table

Annex 4: Analytical methods

1.Description of analytical models used: primes-tremove model

Baseline scenario

Main assumptions of the Baseline scenario

Summary of main results of the Baseline scenario

2.Description of analytical models used: Ecorys model for the regulatory costs for businesses and public administrations

3.Assumptions used for assessing impacts on modal shift

4.Assumptions used for the uptake of electronic documents

Annex 5: Monitoring arrangements

Operational objectives of the preferred policy option

Monitoring and evaluation framework – Relevant indicators and data sources

Annex 6: Political context of the initiative and coherence with key EU policy objectives

The White Paper on Transport

Annex 7: Legal context and coherence with other relevant EU legislation and initiatives

1.Coherence with other on-going proposals/ initiatives including digitalisation provisions

2.Coherence with other EU legislation currently in force

EU transport legislation

EU customs and fiscal legislation

EU legislation on official controls on agri-food chain

EU electronic identification and trust services for electronic transactions legislation

Glossary

|

Term or acronym

|

Meaning or definition

|

|

Business register

|

The database maintained by each Member State to keep record of registration of companies in the given Member State and subsequent changes in the information on companies.

|

|

Electronic data vs digital

|

See https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/electronic-vs-digital-data-bernadette-bosse/

|

|

International transport

|

Pursuant to articles 90 and 91 TFEU, by international transport it is understood in this study the transport of goods from the territory of a Member State or passing across the territory of one or more Member States

|

|

Shipment

|

Determined set of goods that exchanges ownership and needs to be transported from seller shipping point to a final buyer's/consignee reception point

|

|

Member States/public authorities

|

All relevant authorities. For the purposes of the analysis in this study, a distinction has been made between enforcement authorities and judicial authorities.

|

|

Enforcement authorities

|

Relevant public authorities having tasks related to controlling, monitoring and ensuring enforcement of applicable legal provisions concerning the international transport of goods on the territory of the EU, such as police, fiscal police, ministries and their agencies.

|

|

Judicial authorities

|

Administrative, criminal or civil courts.

|

|

Member State(s) (MS)

|

In the context of this Impact assessment, this covers Member States of the EU and of the EEA (i.e. Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway in addition to the EU).

|

|

Data

|

Information that has been encoded digitally, using a revisable structured format which can be used directly for storage and processing by computers.

|

|

Data elements

|

A unit of data which, in a certain context, is considered indivisible and for which the identification, description and value representation has been specified.

|

|

Information

|

In the context of this Impact assessment, it covers the transport related information included in the transport documents and are necessary for the controls by authorities.

|

|

Registered office

|

The office and the address under which the company is registered in the business register.

|

|

SME

|

Small and Medium Enterprises

|

|

DTLF

|

Digital Transport and Logistics Forum

|

|

TFEU

|

Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, OJ 2012/C 326/01

|

|

RFD

|

Reporting Formalities Directive – No 2010/65/EU on reporting formalities for ships arriving in and/or departing from ports of the Member States and repealing Directive 2002/6/EC

|

|

eIDAS Regulation

|

Regulation (EU) No 910/2014 on electronic identification and trust services for electronic transactions in the internal market and repealing Directive 1999/93/EC

|

|

UCC

|

Union Customs Code as laid down in the Regulation (EU) No 952/2013

|

|

RIS Directive

|

Directive 2005/44/EC on harmonised river information services (RIS) on inland waterways in the Community

|

|

IWT

|

Inland waterways transport

|

|

CMR Convention

|

Convention on the Contract for the International Carriage of Goods by Road (CMR), Geneva 19 May 1956

|

|

CMR

|

Consignment note as defined in the CMR Convention

|

|

eCMR Protocol

|

Additional Protocol to the Convention on the Contract for the International Carriage of Goods by Road (CMR) concerning the Electronic Consignment Note, Geneva 27 May 2008

|

|

eCMR

|

Electronic consignment note as defined in the eCMR Protocol

|

|

CIM

|

Uniform Rules Concerning the Contract of International Carriage of Goods by Rail (CIM) - Appendix B to the Convention concerning International Carriage by Rail (COTIF) 9 June 1999

|

|

COTIF

|

Convention concerning International Carriage by Rail (COTIF) 9 June 1999

|

|

CIT

|

International Rail Transport Committee

|

|

CIM consignment note

|

Rail consignment note

|

|

TAF TSI

|

Technical specifications for interoperability relating to Telematics application for freight

|

|

TAF TSI Regulation

|

Regulation (EU) No 1305/2014 on the technical specification for interoperability relating to the telematics applications for freight subsystem of the rail system in the European Union and repealing the Regulation (EC) No 62/2006

|

|

CMNI

|

Budapest Convention on the Contract for the Carriage of Goods by Inland Waterway (CMNI) Budapest 2000

|

|

Hamburg Rules

|

United Nations International Convention on the Carriage of Goods by Sea (Hamburg Rules) Hamburg 31 March 1978

|

|

Montreal Convention

|

Convention for the Unification of Certain Rules for International Carriage by Air, Montreal 28 May 1999

|

|

eAWB

|

e-air waybill

|

|

IATA

|

International Air Transport Association

|

|

Rotterdam Rules

|

United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Carriage of Goods Wholly or Partly by Sea (Rotterdam Rules) 11 December 2008

|

|

B2A

|

Business to Administration communications

|

|

B2B

|

Business to Business communications

|

|

Directive on dangerous goods

|

Directive 2008/68/EC on the inland transport of dangerous goods

|

|

ADR

|

European Agreement concerning the International Carriage of Dangerous Goods by Road, 1 January 2017

|

|

RID

|

Convention concerning International Carriage by Rail (COTIF) – Appendix C - Regulations concerning the International Carriage of Dangerous Goods by Rail, 1 January 2017

|

|

ADN

|

European Agreement concerning the International Carriage of Dangerous Goods by Inland Waterways, 1 January 2017

|

1Introduction: Political, legal and market context

1.1.Freight transport documents – background and scope limitation of this initiative

The movement of goods from sellers to buyers is accompanied by a large amount of information being exchanged among a variety of parties, in both the private and the public domain. Today, this information is mostly printed on paper, in a variety of standard format documents. Most of these documents are issued by private parties and serve to convey important information related to their own contractual relation for the movement of the goods, and for business administration purposes. Some of these are also used by authorities as source of information to verify regulatory compliance.

These documents are physically exchanged and, in the case of some of them also signed, and at times also modified, by hand, in a number of copies. As a result, the information contained in these documents is recopied in and printed out of the electronic systems of the various parties several consecutive times, for each individual cargo shipment. This is because one or more of the commercial parties involved, or one public authority concerned or another, request to see or sign paper documents.

In a context where virtually all companies, to a very large extent, record, exchange and store data related to their business in electronic format, these paper-based information exchange processes over the movement of the goods are the source of important cost-inefficiencies, mainly related to the physical management of the paper documents, but also to business operations management. Some stakeholders have described them as a “black box”, which prevents the “end-to-end” visibility over the movement of the goods in the supply chain that businesses need to fully reap the benefits of digitalisation.

This impact assessment focuses on goods related documents. The other two main groups of documents used in freight transport, namely documents related to the means of transport and, respectively the personnel manning them, have not been include in the scope. This focus limitation is linked to the distinct nature of the goods related documents and, in particular, their dynamic and commercial character.

These documents are unique to each distinct set of goods being shipped from a seller to a buyer or final user and, therefore need to be issued anew for each shipment. In the case of the main transport documents, the contracts of carriage, in particular, they may also undergo changes during the course of the transport operation itself. They are mostly issued by the businesses, and serve both business-to-business and business-to-authorities information communication purposes.

By contrast, the documents concerning the means of transport or the personnel manning them – such as certificates concerning the registration of a vehicle, its conformity with requirements for the transport of specific good or, in the case of personnel, if they have the qualifications to drive/conduct a certain type of vehicle – is issued either by a public authority or a private entity authorised by a public authority to do so. They are also static documents in the sense that, once issued, do not need to be renewed but only at very long and regular intervals. They are also used mainly in relation to the authorities, and do not need to be exchanged between the commercial partners. For this reason, even though the majority of these "other" documents involved in a transport operation are still being issued, kept and presented to the authorities on paper (and to some extent on plastic), the cost inefficiencies related to the issuing and management of these documents is, currently, less significant to the businesses than those related to goods documents.

1.2.Political context

The Commission has acknowledged the need to foster acceptance and use of electronic transport documents in a number of policy initiatives: the White Paper on Transport, 2011

; the Digital Single Market Strategy, 2015

; the ICT Standardisation Priorities for the Digital Single Market, 2016; the EU eGovernment Action Plan 2016-2020, 2016

. The case for intervention has been recognized also by a wide range of stakeholders.

Since 2015, participants in the Digital Transport and Logistics Forum (DTLF) – a Commission expert group formed by more than one hundred private and public stakeholders

– have repeatedly emphasised the need for EU level intervention to support wider uptake of electronic transport documents. In October 2017, in the Tallinn Declaration on eGovernment, the Member States urged the Commission to step up efforts for provision of efficient, user-centric, electronic procedures in the EU, pointing out the significance of the eGovernment Action Plan 2016-2020

and the vision of the European Interoperability Framework

.

In November 2017, during the Tallinn Digital Transport Days, several public and private stakeholders from all transport sectors concluded that it is about time to reap the benefits of digitalisation, including paperless data sharing

. Following up, the Council called on the Commission, in its December 2017 Conclusions on the digitalisation of transport, to continue working with the DTLF to develop “measures to support

more systematic use and acceptance of e-documents and the harmonised exchange of information and data in the logistic chain”

. In May 2017, the Parliament had also called on the Commission “to increase harmonisation in passenger transport and transport of goods”, and “to speed up the mandatory use … of electronic consignment notes (e-CMR)”, in particular

.

1.3.Legal context

The eIDAS Regulation

provides a horizontal EU legal framework for the acceptance of electronic documents by Member States’ authorities, but only as evidence in legal proceedings. It does not impose an obligation on Member States’ (enforcement) authorities to accept electronic documents as evidence for other regulatory purposes, such as compliance with various legislative provisions, including as concerns the conditions for the transport of goods.

The main information sets concerned also differ. This initiative focuses only on regulatory information concerning the goods and the transport operation itself – on the identity of the consignor, carrier and consignee, places of pick-up and delivery, route and several others. Both the UCC and the RFD concern also cargo information description, but alongside a large host of other information sets. In the case of UCC, this also includes certain information elements related to the transport operation itself; in the case of RFD, additional sets of information elements on the ship, its crew and passengers are concerned.

Both the UCC and the RFD already contain provisions allowing fulfilment of reporting formalities by means of electronic information communication, including as regards the cargo and, respectively, the transport operation

. This initiative aims to allow electronic communication for fulfilling regulatory information requirements also beyond the points of entry, or before the point of exit, of the EU, on the entire territory of the Union. Geographically therefore, the scope of this initiative begins where that of the UCC and/or the RFD ends (or, conversely, ends there where that of the UCC and/or the RFD begins).

In terms of the transport operations concerned by the information requirements, however, these scopes overlap: this initiative concerns both purely intra-EU international/ cross-border transport (not falling under UCC's or RFD's scope), as well as international transport having its origin, destination or transiting an EU Member State's territory. As a result, the combined application of this initiative and that of the UCC and the RFD will further facilitate international freight transport having its origin and destination outside the EU, as well as intra-EU maritime traffic, by enabling the use of electronic means for transmission of regulatory information on cargo transport to the authorities not just at the point of entry and exit of the EU, but also on the entire EU territory.

The Commission is currently considering further policy initiative in both policy areas covered by these two instruments, but neither is considering enlarging the information reporting requirements, nor the geographical scope of the application of the related regulatory conditions. Rather, these initiatives aim at insuring interoperability of the electronic data exchange related to their respective information reporting requirements. In this respect, this initiative will also aim to ensure the interoperability of the electronic data for the common information elements.

In terms of technical solutions for enabling the electronic communication of the information/documents, this initiative also requires a different approach, due to the specificities of the information reporting under the UCC and the RFD. In the case of the latter, the information must be submitted at a specific point in time – before or at the time of arrival at EU entry/exit point – to all of a pre-defined set of authorities. By contrast, the information concerned by this initiative only needs to be available in case it is required for inspection, by one or another of the competent authorities, at any point in time during (and in certain cases also after) the completion of the transport operation.

Several other EU legal acts and ongoing Commission policy initiatives address digitalisation aspects and affect to some extent transport related issues. None is however addressing the problem as identified in the context of this impact assessment report

.

1.4.Market context

Total freight transport in the EU has increased by almost 25% over the last 20 years

, and it is projected to further increase by 51% during 2015-2050 under current trends and adopted policies

. Today, this information is mostly printed on paper, in a variety of standard format documents. 99% of cross-border transport operations on the territory of the EU still involve paper-based documents at one stage of the operation or another. The digitalisation of information exchange has the potential to significantly improve the efficiency of transport and, therefore, to contribute to the smooth functioning of the Single Market.

In the past two decades, there have been a considerable number of private, public and mixed initiatives aiming at developing technical solutions for the digitalisation of transport and logistic processes

. While contributing to efficiency gains in specific transport sectors and Member States, these initiatives were often run independently from each other.

The growing concern, raised by all stakeholders, is the limited interoperability of the various systems and technical solutions being developed

. In the absence of overall coordination and reliable indication as to which would be the dominant standard for data definition, representation, exchange and preservation

, individual businesses face the risk of making the wrong choice of investment. In addition, specificities of individual transport modes – including their (historically separate) regulation – mean that most digitalisation efforts remain mode-specific

. Yet, even in the rail and air transport sectors, where a de facto dominant international system for information and documentation exchanges has been established, concerns for the lack of interoperability and interconnectivity across mode-specific solutions and systems are high

.

2Problem definition

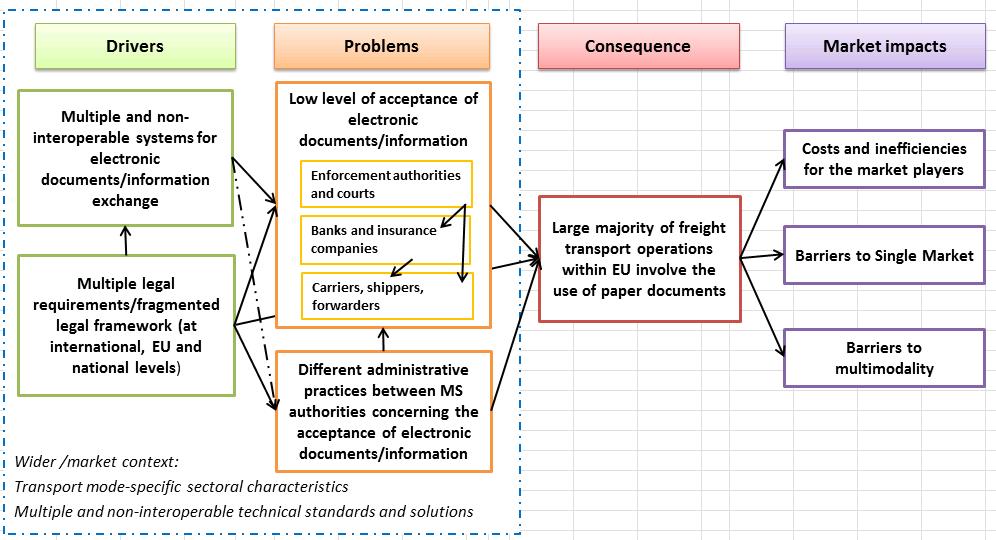

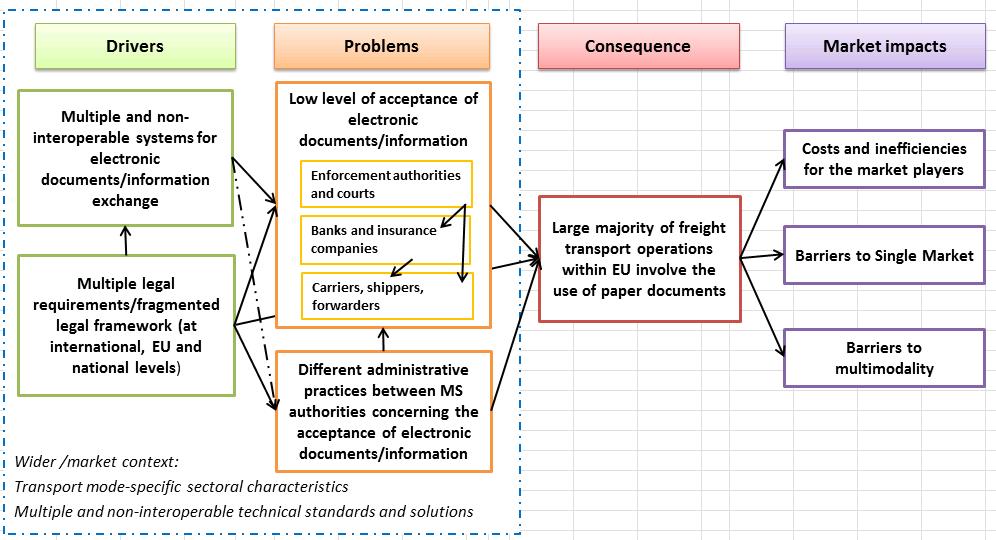

The main identified problem is the low and varying degree of acceptance by authorities of information or documents electronically communicated by the business as evidence of compliance with regulatory conditions for the transport of goods on the different EU Member States' territory.

Two main drivers underpin this problem: a) a fragmented legal framework setting inconsistent obligations for authorities to accept electronic information or documents, and allowing for different administrative practices to implement them; and b) a fragmented IT environment characterised by a multitude of non-interoperable systems/solutions for electronic transport information and documentation exchange, both for business-to-administration and business-to-business communication.

The two drivers are mutually reinforcing. The fragmented legislation and the ensuing lack of acceptance by authorities discourage investment in digital solutions for electronic documents. The fragmented IT environment, specifically the lack of well-established or interoperable solutions, discourages authorities from the use of electronic documents.

Furthermore, both drivers are shaped by the fragmented wider market context, which is however not specifically addressed by this initiative, characterised by, on the one hand, historically-evolved characteristics of the different transport sectors and, on the other hand, competing, non-interoperable and evolving industry standards and technical solutions for electronic data exchange.

As a consequence, the large majority of freight transport operators and other transport business stakeholders in the EU continue to use paper documents. This prevents considerable gains in efficiency for the various market players, in particular in multimodal and cross-border transport, and hinders the better functioning of the EU single market.

These issues are further discussed in the upcoming sections and are summarized under Figure 2.1 below.

Figure 2.1: Problem tree

2.1What is/are the problems?

The main conclusion of the stakeholder consultation activities is that there is general uncertainty among the stakeholders as to which authorities, in which Member States, are accepting electronic documents for which types of controls. In particular, stakeholders refer to the uncertainty related to acceptance by enforcement authorities. Acceptance by courts of the contract of carriage is also an issue, but it appears to be less of a concern for a majority of the respondents.

2.1.1Low level of acceptance of electronic freight transport documents by the different market players

Lack of acceptance by Members States’ authorities of electronic documents has been indicated by all categories of industry stakeholders as the main obstacle preventing their wider use.

Member States authorities

Enforcement authorities

Depending on the Member State and mode of transport concerned, authorities inspect cargo transport documents for some or all the following purposes: verification of legitimate possession; enforcement of rules related to safety, taxation, customs, environmental protection, security, working conditions and health, cabotage, and various transport conditions. Various authorities may be involved in inspections: police, fiscal police, tax authorities, customs; and control officers from the transport, health and veterinary departments. There are important differences in the extent to which those authorities currently accept electronic documents as valid (or admissible) evidence for inspection.

In aviation, inland waterways and rail, documents are more often accepted in electronic form. But only in few Member States, and mainly for aviation, acceptance of full documentation is reported. At the other end, road transport documents and, in some cases rail, are explicitly reported as being accepted in paper format only.

Figure 2.2: Significance of the lack of acceptance by Member States enforcement authorities

Stakeholders also indicated significant differences in the inspection procedures, and the information/documents required as proof of compliance. The same transport document is often inspected in the same Member State by different authorities in different ways. Some authorities might accept the electronic transport document, while others only accept paper, although the paper document is often a print-out of the electronic one. Between Members States, differences in inspection practices are equally present, even when the same type of authority is performing a control for the same regulatory purposes in the same transport mode.

Textbox 2.1: Examples of divergent acceptance

An electronic transport document (the electronic air waybill/e-AWB) is accepted for the entry and exit processes of cargo by air in the Netherlands, but when the cargo is being transported by road to reach the final destination, the paper version of the same air waybill is often used, as Dutch road-side inspectors do not accept an e-AWB. In France, while custom authorities accept an e-AWB, a paper AWB still needs to be submitted to airport enforcement authorities

.

In inland transport, the Dutch police requires barge operators to have a paper transport document available at all times (and regularly inspects whether such a document is available on board), while the German police never performs cargo related inspections and therefore does not require a transport document at all.

In road transport, in the Netherlands or Germany for example, the e-CMR would be accepted, but the operators do not use it because authorities of other Member States, such as neighbouring Belgium, do not. Truck drivers do not wish to take risks and therefore are only willing to perform the transport when receive the transport document in a paper format.

In rail transport, an electronic document containing cargo information, which complies with the TAF TSI requirements, is accepted by the Belgian authorities for controls related to dangerous goods regulatory compliance. In Germany, a paper document is always required for dangerous goods certificates.

Overall, the industry stakeholders report general uncertainty as to which enforcement authorities, in which Member States, are accepting which electronic documents for which types of controls. Consequently, to avoid the risk of electronic documents being declared noncompliant by authorities or not accepted by their partners, the transport operators, as well as the other commercial parties involved, prefer to print, carry and exchange paper cargo documents, in spite of all the inconvenience and cost this implies. In the framework of the OPC, 90% of the private companies and associations indicated the non-acceptance of electronic transport documents/ information by Member States authorities as a significant driver. For the smaller companies, according to the SME panel survey, the main reason for not using electronic transport documents is that their clients and business partners do not use transport documents in electronic format, followed closely by non-acceptance by authorities.

Courts

Several stakeholders pointed out in the consultation process the lack or limited acceptance of the electronic transport documents by courts. Private parties should be able to enforce their rights in civil law procedures on the basis of the electronic transport document that serves as a contract of carriage. Secondly, operators should be able to challenge a fine imposed by an authority which refused to accept an electronic transport document.

Figure 2.3: Significance of legal aspects (N=45)

Source: Ecorys et al., 2018, results of targeted survey

According to the targeted survey undertaken in the context of the IA support study, 38% of the respondents consider the lack of acceptance of electronic transport documents in courts as important (22% as very important, and additional 16% as moderately important). There is certain divergence of views among the stakeholders, as 29% of private companies consider this factor very important, against only 10% of the authorities.

The support study also found limited empirical evidence on the acceptance of electronic transport documents by courts and on the enforceability of the contracts of carriage concluded or evidenced in an electronic form. In France, for example, where acceptance of electronic documents for road transport has been established already by national law in 1999, there is no case law yet on the enforceability of electronic transport documents

. In the framework of the stakeholder consultation, none of the respondents was able to identify case law recognizing the enforceability of electronic transport contracts. The limited use so far of electronic transport documents may explain the lack of such case law, and the lower importance attributed to the ‘courts’ dimension of the ‘limited acceptance’ driver.

Non-acceptance by third countries authorities

In the OPC and SME Panel several stakeholders added the non–acceptance by third country authorities as an additional barrier hampering the use of electronic documents only. In the OPC, several stakeholders indicated that the non-acceptance is also a bottleneck when trading with neighbouring countries that are not part of the EU. An example frequently mentioned was Russia, as paper documentation is required in all road transport between Russia and the EU.

The respondents to the targeted impact survey and targeted interviews undertaken in the framework of the IA support study confirmed this view. Out of the 45 respondents to the survey, 30 indicated that the non-acceptance of electronic transport documentation in third countries is, at least moderately, contributing to the problem. Authorities and private stakeholders interviewed also raised this issue.

Acceptance by businesses

Another important aspect is linked to the low acceptance of e-documents by the commercial parties themselves. Among these, banks and insurance companies, which are often necessary parties to a transport operation – insuring the cargo or providing bank guarantee as to the payment of the goods shipped – are highly relevant stakeholders in this regard.

Figure 2.4: Significance of problem driver to the overall problem – lack of acceptance by banks

Source: OPC and SME Panel

In the industry’s view, the acceptance by banks and insurance companies of electronic transport documents, particularly those that evidence the contract of carriage, is strictly related to the acceptance and enforceability of the electronic contracts of carriage in courts.

More than half of the stakeholders in the OPC indicated that the limited acceptance by both banks and insurance companies contributes, at least moderately, to the overall problem. Private companies (ranging from transport operators and forwarders to different associations) were the main respondents to the OPC. A relatively large share of the respondents (almost 30%) indicated however that they do not have an opinion on the subject.

Figure 2.5: Significance of problem driver to the overall problem – lack of acceptance by insurance companies

Source: OPC and SME Panel

Lack of legal certainty in this regard impacts the decision of banks and insurance companies to accept electronic transport documents

. In case of litigation, banks and insurance companies want to be certain that the responsibilities and liabilities mentioned in a contract of carriage are enforceable by means of court order. It appears however, that insurance companies tend, more than banks, to accept electronic transport documents when requested to insure cargo.

Smaller companies experience higher lack of acceptance by banks and insurance companies than their relatively larger counterparts. As presented in the figure 2.5, more than 60% of the respondents to the SME Panel see the lack of acceptance as a significant contributor, while in the OPC only 20 to 24% of the respondents showed a similar view. The difference might be explained by the fact that for smaller companies it is more difficult to obtain finance or insurance (due to business risks), than it is for larger companies.

2.1.2Different administrative practices between and within Member States

The analysis of the stakeholder consultation has revealed important differences in the way the different Member States authorities are conducting inspections aimed at establishing compliance with applicable regulatory requirements. Thus, when the same transport document is inspected in the same Member State by different authorities, for different purposes, they may do so in different ways. Across Members States, differences in inspection practices are equally present, even when the same type of authority is performing a control for the same regulatory purposes in the same transport mode.

Furthermore, the consultation revealed that the appreciation by the different individual public authorities, including at the level of the enforcement officers, of the extent to which they may trust or not a document presented electronically, also determines whether they may accept in one case such document as evidence, while in other they may require to see the paper documents. Different authorities may impose different requirements for the acceptance of the same information/document inspected also pursuant to their long-established practices.

Several authorities in (at least) some Member States appear to follow different administrative processes, developed in the course of decades. When moving from paper to digitalised inspection processes, these practices tend to be reproduced, resulting in continuing differences in therefore, with consequences for compliance requirements for businesses. This is for example the case in the maritime sector in Italy, where the harmonization of different administrative processes followed by the different maritime authorities has been the main challenge for the implementation of the maritime national single window, in the context of the RFD, at national level

.

Textbox 2.3: Other examples of different administrative practices

In the Netherlands, an electronic transport document (the e-AWB) is accepted for the entry and exit processes of cargo by air, but when the cargo is being transported by road in order to reach the final destination, the paper version of the same air waybill is often used, as road side inspectors do not accept an e-AWB. Although the e-AWB is recognised by Dutch law (and is a valid document) road side inspectors still require a paper version. They prefer paper over electronic documents as they fear that the latter might be fraudulent.

Reportedly, in France, while custom authorities accept an electronic air waybill, a paper air waybill still needs to be submitted to airport handlers or airlines

.

Another illustrative example for the argument made above is that of the Luxembourg police. Currently, officers may seize all paper documents presented by a driver during a road-side control, if they have reasons to suspect that the information or the documents provided are not genuine. Not surprisingly, during training in preparation of the launch of the Benelux e-CMR pilot, the main questions they raised were: how to trust that what they would be presented on a smart phone/tablet is genuine?; and, in case they had doubts, whether they would be allowed to confiscate the respective tablet/smartphone?

.

2.1.3Why is it a problem?

Businesses are currently facing a complex and uncertain landscape regarding the acceptance of electronic documents, particularly by the public authorities, in the different Member States. Consequently, and to avoid the risk of electronic documents being declared noncompliant, the transport operators as well as the other involved commercial parties prefer to print, carry and exchange paper cargo documents, in spite of all the inconvenience and cost this may imply. Paper is often carried in parallel to electronic information and documents exchange.

Paper-based information and documentation exchange processes, both in business-to-business (B2B) and business-to-administration (B2A) communication, have been identified by numerous companies as an important source of foregone cost savings, untapped potential for administrative burden reduction and, more generally, efficiency losses. The large majority of the stakeholder consulted – i.e. more than 90% of the 265 SME respondents to the SME panel survey, and 88 of the 100 respondents to the open public consultation (OPC) survey indicated significant or at least some expected benefits from adopting electronic information exchange.

Businesses have identified different sources of costs related to the paper-based processes. A primary source is the management of the physical documents as means of transfer of information from one party to the other – primarily related time spent by the employees, but also the use of physical resources such as paper and printer toner. Another source of costs are the errors in the manipulation of these documents by the various individuals involved in a transport operation – such as errors in (re-)copying the data, damage, misplacement or loss of documents.

The degree of digitalisation is different across transport modes, impacting differently the time (and equivalent costs) spent in processing freight transport information by the different transport modes. Due to reasons explained under the problem driver section, the highest level of uptake of e-documents/information exchange is in the aviation sector (c.a. 40 %) followed by the rail sector (c.a. 5%) and road (c.a. 1%). The overall levels of uptake in the maritime and inland waterway transport sectors are close to zero. Table 2.1 shows that in 2018 it is estimated that more than 380 million hours would be spent for processing freight transport information needed for national and international trips, equivalent to almost EUR 7.9 billion:

Table 2.1: Estimated time and equivalent costs spent processing freight transport information by mode of transport in 2018

|

|

Total time spent processing freight transport information (million hours)

|

Administrative costs - intra-Member State shipments (EUR million)

|

Administrative costs - shipments between EU Member State (EUR million)

|

Total administrative costs (EUR million)

|

|

Road

|

297

|

5,663

|

299

|

5,962

|

|

Rail

|

29

|

299

|

208

|

507

|

|

IWT

|

24

|

178

|

404

|

582

|

|

Maritime

|

36

|

147

|

667

|

814

|

|

Aviation

|

1

|

3

|

22

|

25

|

|

Total

|

387

|

6,290

|

1,600

|

7,890

|

Yet other costs are related to inefficiencies in companies’ internal decision-making processes, due to lack of real-time information on their actual physical stock (what goods are sold, but still awaiting shipment, which are in transit, which delivered and awaiting payment or, conversely, which have been contracted, but not yet delivered, for what value etc.). In addition, overall supply chain organisation could also be significantly optimised, if real-time data on the goods being moved were available.

National public administrations believe that there is a potential for more effective use of larger volumes of data, in particular with regards to their capacity to effectively and efficiently enforce applicable regulations, and to devise better targeted and more effective policy measures. Moreover, some public administrations also indicate that there are some efficiency losses in processing non-digitised information. For example, for the Rhine-Danube corridor alone, authorities estimate about 5 million euros losses due to the time needed to process non-digital information for investigations.

In short, paper-based processes of transport information and documentation exchange are an important source of unnecessary costs and inefficiencies for businesses. They also particularly affect the transport of goods changing transport mode or crossing borders, thus potentially hindering multimodality and putting obstacles to the Single Market. In multimodal transport operations involving several modal legs, stakeholders estimate potential savings from the digitalisation of current paper-based processes at about three times higher, per shipment, than in a unimodal operation. The two case studies conducted provide evidence of benefits of around EUR 9-37 and EUR 21-87 per trip due to time savings.

Table 2.2: Samskip case studies on administrative cost reduction from transport e-document

|

|

Member States involved

|

Modes of transport

|

Number of transfers

|

Lost time savings (min)

|

Lost cost savings (EUR)

|

|

Case 1

|

DE – NL – IE

|

Road – Maritime - Road

|

2

|

29.6

|

9-37

|

|

Case 2

|

NO – NL – DE - IT

|

Road – Maritime – IWT – Road – Rail - Road

|

5

|

89.6

|

21-87

|

2.2What are the problem drivers?

2.1.4A fragmented legal framework concerning the acceptance of electronic freight transport documents/information

Today, no single or uniformly applicable legal framework regulates the use of (electronic) cargo and transport documents for international freight transport in the EU. The applicable rules are determined by the combined application of various legal acts, issued at international, European, and national level. The result is a highly fragmented legal regime, which varies depending on the Member State, the transport mode and, often, the type and use of the documents.

In the context of the present assessment, it is important to pay attention to three aspects that affect the use of electronic transport documents, and information more generally: (a) the general acceptance of the electronic form; (b) the requirements for validity of the electronic form (i.e. the necessary and sufficient conditions for acceptance); and (c) the technical specifications for implementation of these requirements.

ØThe obligation of acceptance

The international conventions relevant for this analysis are primarily those governing the regime applicable to the international contracts of carriage in the different transport modes. These conventions establish, separately for each transport mode, the legal equivalence of the electronic contract of carriage to that of the paper-based document

. These conventions enable the use of the electronic contract of carriage but, except for the protocol to the CMR convention, the application of their provisions on electronic documents is conditional on the existence of specific national rules. In practice, they apply only if the national legislation of the State under which the contract was concluded allows the use of the electronic means for the conclusion or evidence of a transport contract. The e-CMR protocol, regulating the electronic road consignment note, does not include such clause and it is directly applicable if the respective State is a party to the protocol. Participation in the e-CMR protocol is however relatively modest, though growing.

These conventions regulate however only the contractual relation between the commercial parties, if they choose to use the contract of carriage in an electronic form. They do not impose, but rather allow, the use of the electronic contract of carriage (transport document) by the commercial parties (business to business). Furthermore, they do not regulate the use of electronic documents between business and authorities.

Indirectly, however, these conventions impact the acceptance by the authorities, and in particular courts, which may be called upon to enforce the rights and obligations deriving from an electronic transport contract. For enforcement authorities, they become relevant only when their national legislation requires a valid transport contract to evidence compliance with specific regulatory requirements.

At EU level, acceptance by the Member States’ authorities of electronic documents or, more generally, of evidence communicated by electronic means, is regulated by means of several legal acts

. These acts establish specific conditions for the transport of goods within the EU, either in general or for particular types of goods, for a variety of regulatory purposes – to ensure the safety and security of transport, to facilitate certain types of transport operations, or to ensure the smooth and fair functioning of the transport market. They also specify how, i.e. the required information elements, and by what means the private actors may make proof of compliance with the respective conditions. While the information elements concerned are often overlapping, the means of conveyance of this information, and the degree of specification of what constitutes an admissible electronic evidence, vary significantly between these legal acts.

Only some of the EU legal acts establish the principle of acceptance of the electronic means. Moreover, they do so only for specific regulatory purposes, in specific transport modes – for example for compliance with security requirements in air freight transport, dangerous goods information transmission in inland waterway transport, or fulfil determined customs formalities (such summary transit declaration) for air and maritime. The acceptance of electronic means is generally established as possible alternative to the paper format, with the only exception of maritime formalities at arrival at and departure from ports, where the EU legislation explicitly states that “Member States shall accept the fulfilment of reporting formalities in electronic format”.

In three of the five transport modes, there is at least one legal act that foresees only the use of paper and another one (for a different regulatory purpose) that allows the use of electronic means. As a result, an enforcement authority that controls regulatory compliance of the same transport operation, is expected to accept an electronic document pursuant a certain EU legislation, but to require a paper document pursuant another

.

At national level, Member States’ legislation regulates acceptance by authorities of (electronic) cargo transport information or documentation for a variety of purposes. These include compliance with fiscal rules, environmental rules, or mere legality of transport. Often, compliance with these rules requires presentation of evidence of a valid transport contract

. These provisions vary considerably. They differ both between Member States and within Member States, depending on the transport mode concerned or regulatory purpose

. They range from specific provisions establishing the obligation of the authorities to always accept the electronic means for certain regulatory purposes, when certain conditions are met

, to legislation under which no such means is accepted

. In other Member States, legislation may take the form of horizontal laws requiring or (implicitly) allowing acceptance by authorities of electronic means in business-to-administration communication

. In addition, specific legislation provisions may also require the paper format for certain, clearly identified documents, while remaining silent on others

. Where the legislation specifically requires the acceptance of electronic documents, it is most often limited to the transport contract and it does so for specific regulatory purposes only

or in specific transport modes

.

Acceptance by national courts of the electronic means for business-to-administration regulatory information conveyance, and of transport contracts in particular, depends on specific provisions in national legislation on the type of evidence admissible in legal proceedings in courts. In most Member States the contract of carriage does not need to be in paper to be enforced by national courts

; and while in some States even oral contracts of carriage would be enforceable

, in several of them the national legislation establishes specific conditions for the probative value of contracts concluded electronically. At the same time, acceptance of a document as admissible evidence in courts of law is generally not regulated in detail in most Member States. As a result, most Member States’ national courts have discretion on whether to accept or not electronic transport documents as evidence of a contract of carriage

.

ØRequirements for acceptance/admissibility and guidance on technical implementation

The acceptance of the electronic documents is in practice linked to the criteria and means by which admissibility can be established. When authorities are asked to accept electronically conveyed evidence, they have to apply more general principles of law related to the authenticity and integrity of the information provided. Compared to paper documents

, current guidance on how to establish the validity of electronically conveyed information/documents remains generally limited and uneven. This creates uncertainty and room for interpretation in implementation as to the necessary and sufficient conditions for validity and, therefore acceptance, of the electronic means.

Two levels of specification can be identified with respect to the guidance provided by the current legislative framework: general requirements for acceptance and specifications for technical implementation.

EU legislation limits general requirements for acceptance to the specification of the possibility of use, presentation or transmission of the required information electronically. In addition, the electronic means of information conveyance are referred to, or defined, in different ways. In several acts, a more specific format is implied – “document”, “documentation”

or “message”

– while in others the wider term – “evidence”

– is used. Furthermore, it provides technical specifications in only three of the seven EU legal acts establishing the requirement of acceptance. However, these specifications differ significantly, requiring specific and largely non-interoperable technical solutions.

Similarly, all mode-specific international conventions link the validity (i.e. legal equivalence to the paper format) of the electronically supported contract of carriage to the fulfilment of certain general requirements. Yet these requirements vary significantly between the different conventions. They range from single reference to the manner in which the necessary signatures are performed – “stamped, in symbols or made by any other mechanical or electronic means” (Article 6, CMNI) or just “stamped” (Article 11, Montreal Convention) – to more general reference to the information representation – “electronic data registration which can be transformed in legible written forms” (Article 6, CIM) – to a larger set of more specific requirements such as how the consignment note shall be authenticated, its integrity ensured, and how to deal with additional cargo and transport documents supplementing the note (Articles 3 to 6, e-CMR Protocol). However, none of the conventions provide further guidance on specific options for the technical implementation of these requirements. This is left for the interpretation of the parties concerned resulting in a variety of implementation approaches and specific/non-interoperable technical solutions for electronic transport contracts, mostly along sectoral lines, both by the private sector and the authorities.

National provisions on validity requirements also vary significantly. Most often there are no specific requirements, apart from the possibility, or obligation, to accept electronic means. Some countries have however established explicit conditions, with varying degree of detail – some formulated at general level (such as referred to the identification of the parties, integrity and availability of the document

), other related to the existence of an electronic signature

. These requirements may relate either to certain transport mode documents, (e.g. the transport contract), or to the validity of commercial contracts in general. In most cases, no guidance on technical implementation is provided. Overall, national provisions concerning acceptance leave ample room for interpretation to determine the concrete and specific conditions of their implementation.

34 (i.e. more than 75%) respondents to the IA support study targeted survey confirmed that the diverse and inconsistent legal framework applicable at EU Member State level on the acceptance of electronic transport documents/information is a significant driver to the limited use of electronic transport documents. 26 respondents also stressed the fact that national rules requirements for handwritten signatures also hampers the use of electronic documentation. Another 23 respondents mentioned the requirement to use stamps on a transport documents as hampering factor.

Closely related to the question whether national rules are in place that allow authorities to accept electronic transport documents, is the question whether they do accept them once the legal basis is provided. 13 out of the 35 respondents to the targeted IA support study survey indicated that authorities do accept the electronic transport documents when the applicable legislation allows it, although the majority also stressed that the authorities do not accept the electronic form once they have reason to believe the documents are not accurate or are manipulated. 12 respondents indicated that, although a legal basis exists that allow authorities to accept electronic documentation they do not accept it. The remaining ten stakeholders did not provide an answer.

It can be concluded therefore, that the legal framework for acceptance of electronic information in relation to international transport operations applicable across the EU is patchy and incomplete. Different requirements in different applicable pieces of legislation implies that the same authority is required (or allowed) to accept an electronic transport document specific to one transport mode, but not to another, or to accept the electronic contract of carriage, but not an electronic invoice, packing list, or house manifest. Furthermore, the limited and variable specification of the law creates ample room for interpretation in application by the authorities. As a result, acceptance remains limited in scale and appears to be more a consequence of initiatives of individual authorities than the legal implication of a general requirement compelling all national authorities to accept electronic transport documents.

2.1.5Multiple and non-interoperable data exchange systems

The second problem driver identified relates to the technical means that authorities need in order to be able to accept electronically communicated transport documents or information. Due to limited requirements by the applicable legislation, the number of transport specific IT systems used by Member States’ authorities is currently small. Apart from the electronic systems set up by the Member States pursuant to the EU legal framework on customs and, respectively, maritime reporting formalities, there have been few attempts to develop transport specific electronic cargo information and documentation exchange systems and, so far, they remained at the level of pilot projects. Each of these pilot projects tended to create its own technical system for sharing the electronic transport documents or information. This means that in each pilot for each authority, mode and Member State, a new technical solution would be introduced for the sharing of information.

As a result, multiple technical systems are used by authorities. In addition, these systems differ from the systems used by business in B2B communication. They contain different information, are based on different technical protocols and might use different devices/solutions. Even within the same Member State, for the same transport mode, systems may differ.

Textbox 2.2: Example of multiple technical systems used within the same Member State

In Germany, multiple systems are used, each based on a different legal act. Based on EU Regulation 2015/2447 custom specific information needs to be included in the ATLAS-system (Automatisiertes Tarif- und Lokales Zollabwicklungssystem). Based on EU Regulation 2010/65, the transport document needs to be included in the National Single Window (NSW) for general inspection. Based on national law, transport related information needs to be included in a nationally developed system.

These different data transmissions contain partly the same data, but transfer formats and data channels are different. Each authority regards the requested data for their own system as the most vital information. Furthermore, almost the same data is sometimes sent to comparable authorities in different EU countries in order to comply with laws in single countries. This existing administrative burden today causes reluctance among all interviewed companies to create another system to send the same data once more.

In the Netherlands, Dutch inland transport sector, two systems are currently used for business-to-administration communication. Furthermore, under the current circumstances, the Dutch barge operators cannot share their transport related information with, for example, the German or Belgian authorities, as they have different systems.

This diversity of public administration systems impacts also on the market responses, resulting in a variety of business-to-administration technical solutions. Most solutions are only suitable for one mode (e.g. road, air, or rail) or are created for a specific authority (e.g. customs), while others are primarily used for business-to-business information exchange.

Rail and air are sectors characterised by rather high concentration of players, and virtually single electronic information exchange solutions with global reach have been established under the umbrella of the respective global industry organisations. This are essentially B2B systems, but are also used for B2A electronic communication. In road, inland waterway and maritime transport, where the market is more fragmented, the number of available solutions is higher, and their use more heterogeneous across the Member States.

However, none of the observed solutions apply at least for B2A electronic information exchange with all authorities in one Member States, let alone apply to all relevant authorities in multiple Member States. As a result, companies need multiple technical solutions to provide the relevant information to authorities and business partners, even if the basic information is the same for all.

The problem therefore, as it emerged from the feed-back received from the stakeholders, is that the low interoperability between the current B2A systems, which also impacts on B2B solutions.

Figure 2.6: Contribution of the problem drivers to the overall problem (n=100)

Source: OPC

The SME panel results for options regarding the question on how interoperability of IT solutions/systems can be ensured reveal that 73% of the respondents consider that standardized technical specifications for sharing data between logistics operators and public administrations should be established.

2.3How will the problem evolve?

Without any specific EU level intervention, acceptance of electronic documents is likely to remain limited.

International fora generally take a long time to secure agreement between the various parties concerned, and often only recommend, but do not require using certain procedures. At EU level, progress may be equally slow and variable, as it will depend on the various revision processes of the current applicable legislation. At national level, Member States will likely continue to adapt their legislation in order to accommodate the increasing need for development of eGovernment services. However, they are likely to do so at variable pace and with different results, depending on national political priorities.

Businesses will likely try to adapt to this evolving enabling environment, in order to capture most of the expected benefits of digitalisation. Therefore, the current trend of slow and mode-specific uptake of a variety of primarily mode-specific and non-interoperable solutions will continue. Theoretically, a company could acquire as many mode specific and/or national specific solutions as necessary, or use the services of companies that provide connecting software that ensures the interoperability of the data exchanged with the various commercial partners. However, that is neither economically sound nor effectively sustainable in practice, due to the high investment and maintenance costs for this solutions and integrators/translators. Rather, the large majority of businesses will continue to prefer the certainty (including as regards costs) of paper, and not invest in digital solutions, since the currently fragmented IT market, as well as the limited acceptance by authorities, makes digitalisation too costly.

In the baseline scenario, freight transport activity for inland modes is projected to increase by 28% between 2015 and 2030 (51% for 2015-2050). Yet the digitalisation levels of the electronic transport document will remain limited for most of the transport modes. The levels provided in the table below represent the continuation of the current situation with only limited coordinated action in the direction of tackling the existing problem drivers. They account however for a certain increase in the use of electronic transport documents in the more digitally-ready Member States, such as for example the Netherlands, Denmark, or Estonia.

Table 2.3: Baseline scenario – assumed level of uptake for electronic documents

|

|

2018

|

2025

|

2030

|

|

Road

|

1%

|

3%

|

5%

|

|

Rail

|

5%

|

10%

|

15%

|

|

IWT

|

0%

|

2%

|

5%

|

|

Maritime

|

0%

|

2%

|

5%

|

|

Aviation

|

40%

|

45%

|

50%

|

Source: Ecorys et al. (2018) impact assessment support study

Driven by growing traffic and low acceptance/use of electronic documentation and information exchange, the administrative costs under the baseline scenario are projected to increase despite some further uptake of electronic documents. Table 2.4 shows the evolution of administrative costs by mode of transport between 2018 and 2030 in million euros. The assumed uptake rates in the baseline scenario and the calculation of administrative costs are explained in Annex 4.

Table 2.4 Estimated administrative costs in the baseline scenario

|

Sector

|

2018

|

2025

|

2030

|

|

|

Digital

|

Paper

|

Total

|

Digital

|

Paper

|

Total

|

Digital

|

Paper

|

Total

|

|

Road

|

42

|

5,920

|

5,962

|

140

|

6,474

|

6,614

|

250

|

6,776

|

7,026

|

|

Rail

|

17

|

490

|

507

|

40

|

536

|

576

|

66

|

559

|

625

|

|

IWT

|

0

|

582

|

582

|

7

|

628

|

635

|

18

|

656

|

674

|

|

Maritime

|

0

|

814

|

814

|

9

|

873

|

882

|

25

|

901

|

926

|

|

Aviation

|

8

|

17

|

25

|

11

|

20

|

31

|

15

|

21

|

36

|

|

Total

|

7,890

|

|

8,738

|

|

9,287

|

|

Source: Ecorys et al. (2018) impact assessment support study

The slow and mode-dependent progress in the acceptance/use of electronic documents and information exchange is expected to hamper developments in the multimodal transport. In the baseline scenario road transport would maintain its dominant role within the EU, road freight activity going up by 27% by 2030 (47% for 2015-2050). These developments would not support the achievement of the 2011 Transport White Paper goal of shifting 30% of road freight over 300 km to other modes such as rail or waterborne transport by 2030. A description of the baseline scenario and its assumptions is provided in Annex 4.

3Why should the EU act?

3.1Legal basis

The legal basis is provided by Article 91 and 100(2) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), which must be understood in light of Article 90. Article 90 requires Member States to pursue a common transport policy. Articles 91 and, respectively 100(2) set out the requirement that common rules applicable to international transport to or from the territory of a Member State or passing across the territory of one or more Member States and, respectively, appropriate provisions for sea and air transport, be laid down by the European Parliament and the Council.

3.2Subsidiarity: Necessity of EU action

Unilateral initiatives by Member States to facilitate the uptake of electronic transport documents and information exchange would have limited effect, if similar action was not taken in other Member States whose territory is also concerned by the transport operations in question.

At the same time, even if most EU Member States were to enact legislation facilitating the use of electronic documents, there is a high risk that, legislating unilaterally, each Member State would adopt different requirements for the acceptance of electronic documents, and regulatory information communication more generally, as valid and authentic. In practice, electronic documents and regulatory information communication which fulfilled the requirements for acceptance in one Member State would not be accepted in the other(s), thus creating barriers in the EU internal market.

3.3Subsidiarity: Added value of EU action

The most appropriate level to address the problem and its drivers is therefore the EU level, where a uniform approach to acceptance of and common standards for acceptance of electronic documents can be set. In that respect, this initiative takes further and complements measures already established at EU level to ensure uniform conditions for acceptance of electronic freight transport information and documents, including by ensuring trust with regards to the electronic means for their communication.

4Objectives: What is to be achieved?

4.1General and specific objectives

The general objective of the initiative is to contribute to removing barriers to the smooth functioning of the Internal Market, to the modernisation of the economy and to the greater efficiency of the transport sector, through enabling wider use of digital technologies.

This general objective would be achieved by means of specific measures implementing the following specific objectives:

a) Addressing the problem driver "fragmented legal framework"

1.Ensure the establishment, in all EU Member States, of the obligation of acceptance of electronic cargo transport documents/information by all relevant public authorities;

2.Ensure the uniform implementation by authorities of the obligation of acceptance;

b) Addressing the problem driver "multiple and non-interoperable systems"

3.Ensure the interoperability of IT systems and solutions for electronic exchange of cargo transport information, in particular for B2A regulatory information communication.

There are clear synergies between the specific objectives of the intervention. For example, acceptance of the electronic transport information/documents by the authorities will significantly impact the level of acceptance by the businesses, and is expected to have a significant impact on reducing related B2A administrative costs and on improving the accuracy and reliability of the information exchanged B2B. However, if the authorities will continue to have large room for interpretation in how to apply their regulatory obligation to accept the information/documents communicated electronically, this will significantly impact the interoperability of the systems developed or adopted by the authorities to that end. If these systems remain not interoperable, this will impact on the interoperability of the solutions developed for the businesses, both for B2A and B2B communication, and therefore their related costs. As a result, the printed versions of the documents will continue to be issued and physically exchanged alongside the goods throughout the entire logistics chain. Therefore, it is important to pursue these objectives in parallel for a more coherent system of digital solutions.

All of the stated specific objectives were supported by the large majority of the stakeholders consulted. 90 of the 100 OPC respondents fully agreed with the first objective, namely to ensure the acceptance by Member States' authorities. The same number of respondents also agreed with the third objective, aimed at ensuring the interoperability for B2A and B2B communications. There was also no subgroup of respondents that disagreed with any of these two objectives.

Likewise, most enterprises responding to the SME panel indicated that ‘acceptance by MS authorities’ would be the most important policy objective to increase the use of electronic transport documents by SME’s (with 198 out 265 indicating it as a very important objective, and additional 35 as moderately important). A great majority also indicated the ability to use a single IT application/system to exchange electronic transport documents with all the other companies as a second most important objective (240 in total, with 172 indicating it as very important and 58 as moderately important).

The second objective has been suggested by stakeholders during the consultation workshops and interviews. It aims to complement the implementation of the first objective, by ensuring also the uniform implementation, across the Member States, of the new uniform legal regime concerning the acceptance of the electronic documents by the authorities. This would tackle, in particular, the different administrative practices aspect of the identified problem.

The objectives of the present intervention are consistent with the objectives of other ongoing initiatives currently being pursued, such as on the revision of the cabotage and combined transport rules in the EU, which provide for the acceptance by authorities of electronic evidence as proof of compliance with these rules, but do not provide detailed guidance on what could be considered authentic evidence, and how such authenticity could be proved. As highlighted earlier, the initiative is also consistent with the on-going initiative dealing with the RFD revision. By ensuring the uniform acceptance of electronically communicated cargo transport information on the hinterland journey of the goods – either before reaching a port for continuation over a maritime leg, or once the goods left the port after their maritime voyage – this initiative would facilitate the possibility of end-to-end electronic communication and exchange of transport information along the entire logistics chain. Furthermore, in pursuing the objective of ensuring the interoperability of the systems used by authorities to accept the electronic cargo information, synergies will be exploited, notably in terms of data models and interoperability.

5What are the available policy options?

5.1What is the baseline from which options are assessed?

The Baseline scenario reflects developments under current trends and adopted policies as described in section 2.4, without further EU level intervention. In this scenario the acceptance of documents will continue to remain limited, particularly on the side of the public authorities, though improving slowly and at variable speeds depending on the transport mode and on the Member State concerned.

The adoption by authorities of technical implementation orientations and digital tools for inspecting electronic transport information would also remain limited, and largely divergent. Slow progress will be hampering the development of multimodal transport. National based approaches will likely continue to remain the norm, impacting on the digitalisation of cross-border transport information and documentation exchange. As suggested by current pilot initiative, more efforts for coordination among the different Member States and between and with the business can be expected. Yet, as this experience also suggests, these pilots will continue largely independently, with cross-border coordination concentrated rather at regional level.

5.2Policy measures and options

A long list of policy measures addressing the two main problem drivers was considered after extensive consultations with stakeholders, expert meetings, independent research and the Commission’s own analysis. This list was subsequently screened based on the following criteria: legal, political and technical feasibility, effectiveness, efficiency and proportionality. Based on this initial screening (see Annex 9 for detailed explanation), a number of policy measures were discarded:

·Separate revision of individual pieces of current EU legislation;

·Obligation for businesses to use electronic documents for regulatory inspection by authorities;

·Establishment of a single EU legal regime concerning the validity of electronic transport contracts as commercial contracts;

·Establishment of a centralised EU transport information exchange system.

The retained policy measures have been grouped in four distinct policy options. Table 5.1 below provides an overview of the retained policy measures, and links the individual policy measures with the problem drivers in the problem definition, the objectives and the policy options.

Table 5.1: Description of policy measures (Key: D1=“multiple legal requirements” driver; D2=“non-interoperable systems” driver; SO = specific objective; S = support measure; R= regulatory measure; ✓ : included)

|

|

Policy measure

|

Driver / Specific objective

|

PO1

|

PO2

|

PO3

|

PO4

|

|

|

Acceptance

|

D1 / SO1

|

|

|

|

|

|

1

|

Member States adherence to international contracts of carrige conventions

|

D1 / SO1

|

✓ R

|

✓S

|

✓S

|

✓S

|

|

2

|

Amendment of international conventions to remove the limitation of applicability of the conventions' provisions on the legal equivalence of the electronic transport contracts

|

D1 / SO1

|

✓S

|

✓S

|

✓S

|

✓S

|

|

3

|

Establishment of general obligation for MS authorities to accept electronic means for B2A information/documentation communication

|

D1 / SO1

|

-

|

✓R

|

✓R

|

✓R

|

|

4

|

Inclusion in relevant EU-third countries bilateral agreements of provisions on mutual acceptance of electronic information/documentation

|

D1 / SO1 (int'l dimension)

|

-

|

✓R

|

✓R

|

✓R

|

|