ISSN 1977-091X

doi:10.3000/1977091X.C_2013.198.eng

Official Journal

of the European Union

C 198

English edition

Information and Notices

Volume 56

10 July 2013

|

ISSN 1977-091X doi:10.3000/1977091X.C_2013.198.eng |

||

|

Official Journal of the European Union |

C 198 |

|

|

||

|

English edition |

Information and Notices |

Volume 56 |

|

Notice No |

Contents |

page |

|

|

I Resolutions, recommendations and opinions |

|

|

|

OPINIONS |

|

|

|

European Economic and Social Committee |

|

|

|

489th plenary session held on 17 and 18 April 2013 |

|

|

2013/C 198/04 |

||

|

2013/C 198/01 |

||

|

2013/C 198/02 |

||

|

2013/C 198/03 |

||

|

|

III Preparatory acts |

|

|

|

EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE |

|

|

|

489th plenary session held on 17 and 18 April 2013 |

|

|

2013/C 198/05 |

||

|

2013/C 198/06 |

||

|

2013/C 198/07 |

||

|

2013/C 198/08 |

||

|

2013/C 198/09 |

||

|

2013/C 198/10 |

||

|

2013/C 198/11 |

||

|

2013/C 198/12 |

||

|

2013/C 198/13 |

||

|

EN |

|

I Resolutions, recommendations and opinions

OPINIONS

European Economic and Social Committee

489th plenary session held on 17 and 18 April 2013

|

10.7.2013 |

EN |

Official Journal of the European Union |

C 198/1 |

Opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee on ‘The economic effects from electricity systems created by increased and intermittent supply from renewable sources’ (exploratory opinion)

2013/C 198/01

Rapporteur: Mr WOLF

On 7 December 2012, the future Irish EU Presidency decided to consult the European Economic and Social Committee, under Article 304 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, on

The economic effects from electricity systems created by increased and intermittent supply from renewable sources

(exploratory opinion).

The Section for Transport, Energy, Infrastructure and the Information Society, which was responsible for preparing the Committee's work on the subject, adopted its opinion on 3 April 2013.

At its 489th plenary session, held on 17/18 April 2013 (meeting of 17 April), the European Economic and Social Committee adopted the following opinion by 147 votes to 2 with 5 abstentions.

1. Executive summary

|

1.1 |

The EESC has given strong support to renewable energy sources (RES) in previous opinions and the preparation of the so-called 20/20/20 package. |

|

1.2 |

The promotion of RES at EU level is intended to reduce energy-related carbon emissions (contributing to Europe's part in climate protection) and import dependency (improving the security of supply). |

|

1.3 |

The increasing share of intermittent RES has prompted intense debates on the technical and economic consequences of such an increase. Following the request by the Irish Presidency, the EESC aims to provide more clarity and transparency on that issue. |

|

1.4 |

Beyond a certain share of the energy mix, intermittent RES require additional components of the energy system to be put in place: grid extensions, facilities for storage, reserve capacities and efforts towards flexible use. The Committee therefore recommends that significant impetus be given to developing and installing these missing elements. |

|

1.5 |

Should these components not yet be available, either the energy output cannot be used from time to time, or networks and control systems can be overloaded from time to time. The consequences would be inefficient use of the installed facilities, as well as threats to the security of energy supply and to a viable European energy market. |

|

1.6 |

Feed-in rules for RES are therefore to be carefully (re)defined, in order to provide for security of supply at all times and ensure that renewable electricity production can meet demand. |

|

1.7 |

Expanding production facilities for intermittent renewable energies still further requires substantial investments to develop and operate the missing components of the complete system. In particular, the development and installation of sufficient overall storage capacity represent a challenge, a chance and an absolute necessity. |

|

1.8 |

As a result, increased use of intermittent renewable energy technologies may well lead to a further considerable rise in costs for electricity, which, if passed on to consumers, could result in a severalfold increase in electricity prices. |

|

1.9 |

A sustainable energy system comprising largely renewables, although carrying additional costs compared with current fossil-based systems, is the only long-term solution for our energy future. It should also be noted that cost rises are inevitable, due to the agreement to include external costs and stop subsidies attached to fossil-based energy. |

|

1.10 |

The Committee therefore recommends that the Commission order an appropriate, thorough economic study on the issue covered by this opinion. This study should take a quantitative look at the unanswered questions. |

|

1.11 |

Other economic repercussions following this cost increase could be (i) potential damage to the competitiveness of European industry, and (ii) a greater burden on socially disadvantaged groups in particular. |

|

1.12 |

Consequently, there is a risk of more manufacturing relocating to non-EU countries where energy is cheaper. Not only could this fail to combat climate change (carbon leakage), it would also undermine Europe's economy and prosperity. |

|

1.13 |

Since additional further costs may arise from inappropriate subsidies and incentives varying from one European country to another, the whole cost issue, including alternative energy strategies, needs to be openly and transparently discussed, also addressing the question of the external costs of the various energy systems and their interdependence. |

|

1.14 |

As a consequence, a common European energy policy and internal energy market are needed. This could provide the basis for a reliable legislative framework inspiring confidence and enabling energy investments and Europe-wide systems – the overarching objective of efforts to build a European Energy Community. |

|

1.15 |

An effective and more market-oriented support instrument serving environmental, social and economic objectives, reflecting possible external costs and covering the whole EU is needed to enable renewable energy technologies to compete on free markets. |

|

1.16 |

Appropriate carbon pricing could be used to this end (e.g. a tax). The Committee recommends that the Commission, together with the Member States, develop appropriate policy initiatives for such a support instrument. All other instruments supporting market penetration of various energy sources could then be abolished. |

|

1.17 |

The global character of the climate problem and international economic integration require a stronger focus on the international economic situation and global carbon emissions. Global agreements on climate protection are therefore of vital importance. |

|

1.18 |

An important element of the further procedure would be the establishment of a public dialogue – European Energy Dialogue – about energy across Europe as outlined in the proposal recently adopted by the Committee and welcomed by the European Commission. Eventually, a study on the impact of the Roadmap 2050 on the EU economy and its global competitiveness is needed, before making final decisions with long term impacts. |

2. Introduction

|

2.1 |

The Committee welcomes the request by the Irish presidency, which addresses a serious problem – a problem that still needs to be solved if the objective of the Energy Roadmap 2050 is to be achieved. The EESC has given its strong support to renewable energy sources (RES) in its previous opinions and the preparation of the so-called 20/20/20 package. |

|

2.2 |

Moreover, the Committee has discussed issues related to the subject of this opinion, most recently in its opinion on Integration of renewable energy into the energy market (CESE 1880/2012). The Committee has called for further installation of facilities to convert renewable energy sources into electrical energy, albeit in the framework of a balanced energy mix. It has recommended a stronger focus on economic and social aspects and on curbing rising costs, above all through appropriate carbon pricing, which should be the only support instrument used. The present opinion follows the same basic line. |

|

2.3 |

With regard to the context and starting points of this opinion, it should also be pointed out that:

|

3. The issue of costs

|

3.1 |

The key economic issue facing any energy supply system is the costs of developing and operating the complete system – from energy producers to consumers – and their impact on economic capacity, competitiveness and social sustainability. |

|

3.2 |

Over the last years, costs have grown significantly in all energy supply sectors. This applies to fossil fuel sources such as oil or gas (with increases aggravated by taxes and other charges), to new nuclear power stations due to significant extra costs arising from safety systems, and particularly also to renewable energy sources due to the substantial subsidies and support mechanisms needed for them to achieve market penetration. In addition, in the complete system there are indirect costs arising from grid development, regulating energy, backup capacity, as well as external costs, which vary from one energy technology to another. |

|

3.3 |

Due to the different subsidies and/or taxes on individual energy sources in different Member States, it is very difficult and complicated to get an overall picture – covering the whole EU – of the costs of the various energy sources. This aspect will be looked at again in the comments in section 4. |

|

3.4 |

In this section, we discuss the expected costs of a growing share of intermittent renewable energy sources, before going on in the next section to look at possible further economic repercussions and to make recommendations for action. While also other energy sources may experience rising costs, while forecasts of future fossil fuel developments – both in terms of use and costs – largely reflect debates on the potential of shale gas and oil and on the significant differences in energy price between the EU Member States and e.g. the USA, and while this may be an important factor in weighing the economic benefits and risks of an increased installation of intermittent renewables, this section is focussed on the expected costs of an increased use of intermittent renewables. |

|

3.5 |

It is recognised that this must be tentative as no independent and authoritative analysis is known which provides a fully comprehensive energy-costs model, including not only all known externalities but which also recognises the significant impact of recent developments in the sourcing and production of unconventional fossil fuels. Eventually, the Commission should launch an economic study assessing the impact of the Roadmap 2050 on the EU economy and its global competitiveness, before making final decisions with long term impacts. The social and economic benefits of renewable energy sources should thereby also be assessed. |

|

3.6 |

External costs play a key role in the debate on different energy sources (especially nuclear energy). Renewable energy technologies may also be associated with risks (e.g. dam bursts, toxic materials) and external costs (e.g. high land occupancy). However, a quantitative analysis of these factors and their interdependence (e.g. because of reserve power-stations using fossil fuels) goes beyond the scope of this opinion, but should be addressed in future debates. |

|

3.7 |

If increased installation of intermittent renewable energy sources continues, indirect systemic costs will outstrip the direct costs of the "electricity production facilities". Although the direct costs of such "production facilities" have significantly gone down, in the meantime, they are not yet competitive without subsidies and still contribute to the rise of the energy bill. However, the additional cost factors of the complete energy supply system referred to below will become substantially more significant only when the relative share of renewable energy sources rises. This is explained in greater detail below. |

|

3.8 |

Intermittent output. Wind and solar energy are only produced when the wind blows and/or the sun shines. This means that facilities used to convert intermittent renewable energy sources into electricity only achieve maximum output for a limited number of hours per year - the period of use of the installed capacity is around 800-1 000 hours for photovoltaic cells (in Germany) and around 1 800-2 200 hours for onshore wind energy, or around twice as much offshore. For example, in Germany the energy yield (derived from Energie Daten 2011, Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft) in 2011 for photovoltaic cells and wind turbines was respectively only just over 10% and just under 20% of the theoretical total annual yield achievable with constant output. By contrast, fossil and nuclear power stations can achieve much higher levels (80-90%) of annual average use (i.e. over 7 000 hours at full capacity), enabling this potential to be used for baseload capacity. |

|

3.9 |

Excess capacity. This means that to replace the annual average output from "conventional" – fossil or nuclear – energy sources using intermittent renewable energy sources, production capacity will have to be increased by factors well in excess of annual peak load; significant production facilities with excess capacity will have to be installed and kept operational together with significant excess transmission/distribution facilities. Even more of these will be needed due to energy lost during storage and reuse. |

|

3.10 |

Two typical cases. The consequences of this necessity can be illustrated by two typical situations; on the one hand we have a situation in which during the period in question most "production facilities" are supplying electricity ( excess supply ), and on the other a situation in which only an insufficient minority are operating ( excess demand ). |

|

3.11 |

Excess supply. Given the need for excess capacities, whenever electricity generated from wind or solar power exceeds grid capacity and current demand from presently accessible consumers, three things can happen: either production partially shuts down (meaning that some potential energy output is unused), or grids become overloaded, or – if the requisite facilities exist – surplus electrical energy can be stored and subsequently supplied to consumers when wind or solar output becomes insufficient. Some mitigation is expected from the possibilities for flexible use (point 3.16). |

|

3.11.1 |

Grid overload and security of energy supply. Energy produced from German wind and/or solar power stations from time to time already now overloads existing transmission grids in neighbouring countries (especially Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary (EurActiv, 21 January 2013), a source of irritation entailing a threat to grid operation and also additional costs due to remedial measures plus the need to invest into protective systems (such as phase-shifting transformers). There is a risk of significantly exceeding tolerance and seriously endangering the security of supply. |

|

3.11.2 |

Storage. In order to (i) relieve the grid system from the overload of the excess supply from the huge overcapacities which are an inherent result of the growing application of intermittent renewables, and (ii) to store this energy for later use, the development and installation of sufficient overall storage capacity represents a challenge, an opportunity and an absolute necessity. |

|

3.11.3 |

Storage loss factor. While water storage power plants lose the least amount of energy and have already been in large-scale use for many decades, due to economic and natural factors and the need for public acceptance, scope for wider and sufficient use of such systems in Europe is very limited at present. Other storage systems for large-scale use are still under development. Forecasts suggest that electricity supplies from innovative storage facilities will cost at least twice as much as unstored electricity (Niels Ehlers, Strommarktdesign angesichts des Ausbaus fluktuierender Stromerzeugung (Designing electricity markets in response to the development of intermittent electricity production), 2011); this means a loss factor of at least two. In this area in particular, there is a very great need for research and development. |

|

3.11.4 |

Development of the complete electricity supply system must be a priority. Consequently, in order to further install facilities for producing energy from intermittent renewable energy sources, priority will have to be given at first to installing and making operational the missing components of the complete system, in particulate adequate transmission infrastructure and storage systems, as well as systems for flexible usage. |

|

3.11.5 |

Preliminary measures. This must happen if there is to be a continued rationale for priority feed-in to grids, so as not to exceed grid tolerance, and enable renewable electricity production to meet demand without threatening security of energy supply. Otherwise priority feed-in rules will have to be revisited. |

|

3.12 |

Excess demand. Given that renewable energy sources produce a fluctuating output, they can only make a very limited contribution to "firm capacity", i.e. to secure coverage of peak annual consumption. The German Energy Agency (Dena) (Integration EE, Dena, 2012) estimates that this contribution is in the range of 5-10% for wind energy, and as little as 1% for solar energy (compared to 92% for lignite-fuelled power stations). These ratios may be more or less propitious depending on the geographical location and climate conditions of the individual countries concerned. |

|

3.13 |

Backup power stations. This means that conventional power stations (backup power stations) will still be needed to compensate for insufficient renewable energy output and provide reliable capacity which can be regulated. Until we have enough innovative electricity storage facilities, such conventional power stations will remain essential. Some conventional technologies are no longer economically profitable, although they are necessary to secure the stability of grid operation. If these backup power stations use fossil fuels (as opposed to hydrogen generated through a process of electrolysis powered by electricity from renewable energy sources, for example), they will also make it more difficult to achieve the Energy Roadmap 2050 target. |

|

3.13.1 |

Keeping capacity in reserve. Compared to "normal" power stations providing baseload capacity, backup power stations are used less intensively over the course of the year and may operate with lower efficiency levels and higher variable costs. They therefore have higher life cycle costs than normal power stations. The economic incentives needed to ensure the requisite backup capacity are now under discussion (Veit Böckers et al., Braucht Deutschland Kapazitätsmechanismen für Kraftwerke? Eine Analyse des deutschen Marktes für Stromerzeugung, Vierteljahrshefte zur Wirtschaftsforschung (Does Germany need capacity mechanisms for power stations? An analysis of the German electricity market, Economic Analysis Quarterly, 2012)). |

|

3.14 |

Evening out regional differences. Alongside backup power stations and storage technology, another option is to even out regional differences in terms of excess supply and demand at certain times, e.g. when the wind is blowing in north-western Europe but not in the south-east. Using this option requires, however, that regions benefiting from high wind levels at a certain moment will also have sufficient excess capacity to cover demand in regions currently lacking in wind, and that both regions will be interlinked with adequate transmission lines. |

|

3.15 |

Expanding electricity transmission grids. given that the vast majority of renewable electricity generation capacity feeds into low and medium-voltage grids, these will have to be developed and strengthened. Transformers and control systems ("smart grids") will also have to be adapted to the new role of distribution grids. Moreover, investment in high-voltage transmission grids is urgently needed, since insufficient interconnections (e.g. between Northern and Southern Germany) cause unplanned flows of energy which endanger the security of transmission systems' operations. This is partly because most wind energy facilities are not located close to high concentrations of consumers or storage facilities, and because additional capacity could enable closer synchronisation in Europe, in order to partially substitute for storage facilities and backup capacities. |

|

3.15.1 |

Ensuring economically viable use of European renewable energy potential at the same time as security of energy supply will thus require major extension of existing electricity grids at local, national and transnational-European level in order to optimise the use of fluctuating energy outputs. |

|

3.16 |

Demand-Side Management (DSM) and electro-mobility. shifting demand from peak to off-peak periods ("functional energy storage"), including electro-mobility, is another option which can contribute to buffer the effects of intermittency. Some uses of electricity would lend themselves to this, for example air conditioning and cooling and heating systems, electrolysers, and electrical melting furnaces. Electro-mobility by means of battery-powered vehicles may be another option here. It should be established what financial incentives, combined with smart-metering, could encourage customers to make the relevant capacity available. |

|

3.17 |

Costs of the system as a whole. The economy as a whole, i.e. basically consumers (and/or taxpayers), will inevitably be burdened with the total costs arising from the use of intermittent renewable energy sources. These include the lifecycle costs of at least two energy supply systems: on the one hand, a set of power stations fuelled by renewable energy, inevitably requiring significant excess capacity that will have to be used, and on the other, a second set of power stations together with conventional backup capacity, electricity storage, new transmission capacity, and demand management for end customers Of course, these must be balanced against the costs associated with continued use of fossil fuels (see 3.3) and potential subsidies for non-renewable electricity production. |

|

3.18 |

Unless other reasons can be found, it is remarkable that, in countries where proactive support schemes for intermittent RES are in place, for example Germany and Denmark, domestic electricity prices are already now around 40-60 % higher than the EU average (EUROSTAT 2012). As a result, increased use of intermittent renewable energy technologies in line with the Roadmap 2050 targets will lead to a rise in costs for electricity, which, if passed on to consumers, initial rough estimates suggest could result in a severalfold increase in electricity prices. In the light of this, please refer to the recommendations in point 3.5. |

|

3.19 |

The first answer to the Irish Presidency's question is therefore that producing increasingly more electricity from intermittent renewable energy sources in line with the Roadmap 2050 targets will lead to significantly higher costs for electricity users. So far, the public debate has not usually looked closely enough at the costs of the complete system, focusing instead only on the costs of (intermittently) feeding energy output into the grid, which is estimated to represent half of total costs. |

4. Economic factors

In view of the above, the most important point to consider next is what steps to take so that (i) the resulting cost increase can be kept as low as possible, (ii) its impact can be made acceptable, (iii) European economic strength will benefit and (iv) energy supply is secured.

|

4.1 |

The system of renewable energies as a whole. In order to prevent avoidable wastage of financial resources and even yet higher energy prices, priority must be given to the planning, development and installation of the necessary components of the complete system – storage facilities, networks and backup power stations – on a sufficient scale to pave the way for the further installation of intermittent renewables. The example of Germany and the reaction of neighbouring countries show what happens when we fail from the very beginning to take this principle into account. |

|

4.1.1 |

Conditions for energy providers. This means that such a complete renewable energy system covering the whole EU has to be installed, in order to avoid feed-in rules be reviewed (see 3.10.5). For example, providers of electricity from intermittent renewable sources could be required to follow a day-ahead production schedule. This task could be facilitated by potential synergies with supply systems based on district heating and cooling and with transport systems. |

|

4.2 |

The debate on what further steps to take should distinguish between the different categories, timeframes and areas of action (even though these are correlated), for example:

|

|

4.3 |

Priority list. When considering options for action, more attention must be paid to global trends and facts, a clear list of priorities must be drawn up for the key objectives, and the growing trend to not harmonised regulatory interference by governments of the various member states must be curbed (see 4.7). Rather than this we need to build trust and thus unlock potential private-sector interest in investment. The following paragraphs look at some aspects of this problem. |

|

4.4 |

A global approach. The overarching goal of European energy and climate policy should be to take the right steps and send the right messages in a way which is as conducive as possible – despite the setbacks to date (Copenhagen, Cancun, Durban, Doha) – to minimising the rise in global CO2 concentration levels, to strengthening European economic competitiveness on global markets, and to making energy on European markets as economical as possible. Given that climate is a global issue, a solely Eurocentric approach is misleading. Laying claim to a "pioneering" role could not only lead to investment and job creation but also undermine our international negotiating position and our appreciation of reality. |

|

4.5 |

Transparency, civil society and consumer interests. If we want to get civil society constructively involved in these processes (TEN/503) and to implement energy policies which are more closely geared to consumer interests, there must be more openness, and ordinary Europeans and decision-makers must be made more familiar with the quantitative facts and correlations. Achieving this is often made more difficult due to the one-sided arguments and information put forward by various privileged stakeholder groups concealing the downsides of their positions. The Committee welcomes the relevant Council conclusions (Renewable Energy Council, 3.12.2012), but at the same time would call for more ambitious and open information policies. |

|

4.6 |

European Energy Dialogue. An important element of the further procedure would be the establishment of a public dialogue about energy across Europe as outlined in the proposal recently adopted by the Committee (TEN/503) and welcomed by the European Commission. Public involvement, understanding and acceptance of the different changes which our energy system will have to go through over the coming decades are essential. In this regard, the EESC's membership and constituency, reflecting European society, is well placed to reach out to citizens and stakeholders in the Member States and establish a comprehensive programme embodying participative democracy and practical action. |

|

4.7 |

A European energy community. The Committee confirms its commitment to a European energy community (CESE 154/2012). Only such a community can represent European positions and interests effectively in relations with international partners while making best use of the relevant regional and climate conditions. Moreover, this is the only way of coordinating and improving national rules and support instruments, which often contradict one another, and of managing and implementing grid development within Europe in the best possible way. |

|

4.8 |

Internal energy market. a European energy community implies a free internal energy market (CESE 2527/2012), including renewable energies. This could ensure that, in view of the complete overhaul of the energy supply system envisaged by the Energy Roadmap 2050, electricity production can be geared to consumer needs as economically as possible, and that investments are made at the right time, in the right places (e.g. in regions with the right climates), and in the most economical electricity generation technologies. Renewable energies must therefore be integrated into a European internal energy market which operates in accordance with free market principles. |

|

4.8.1 |

Competitive renewable energies. In order for renewable energies to become competitive on the energy market, CO2 emissions from fossil fuels must be sufficiently factored into prices by an appropriate and coherent pricing or market instrument. Renewable energies should therefore in the medium term be made "competitive". Unregulated electricity prices plus appropriate carbon prices (e.g. taxes) as an investment incentive should be enough to make this happen. Alongside appropriate charges for network use, this should be a necessary and sufficient condition for investment in backup power stations, storage facilities and demand-side management at the right time, in the right place, and in the right quantity. In this situation, subsidies would only be needed for research, development and demonstration activities linked to new technologies. |

|

4.9 |

A cautious approach to sharing costs. Even though the expected rise in electricity costs is just beginning, measures are already discussed or even installed for exceptional cases. On the one hand, as the Committee has asked (1), low-income social groups should be protected from energy poverty. On the other hand, the most energy-intensive industrial sectors need protection from rising energy costs, so as not to undermine their global competitiveness; failing this, their production sites would relocate outside Europe, to countries where energy is cheaper. This would certainly not help the climate cause ("carbon leakage") (TEN/492). |

|

4.9.1 |

However, one of the repercussions of this situation is that SMEs and middle income groups will in addition have to bear the burden of costs which specific sectors are spared. |

|

4.10 |

Avoiding deindustrialisation. Further deindustrialisation of the EU should be avoided. At present, deindustrialisation is creating the illusion that European efforts to reduce CO2 emissions are succeeding. However, what is actually happening is a hidden form of "carbon leakage": if products are manufactured elsewhere instead of in Europe as was previously the case, the associated "carbon footprint" will remain or could even be exacerbated. |

|

4.11 |

More research and development instead of rushed and premature large-scale market launches. The distinction between research, development and demonstration on the one hand, and large-scale market launches and support on the other must not be blurred; among other things, this could even lead to market situations which would impede innovation. Excessive subsidies for photovoltaic energy (e.g. in Germany, Frondel et al., Economic impacts from the promotion of renewable technologies, Energy Policy, 2010) have not helped to develop a competitive system in the EU (Hardo Bruhns und Martin Keilhacker, Energiewende – wohin führt der Weg (The energy transition - where is it taking us?), Politik und Zeitgeschichte, 2011). We now have cheaper solar panels not because of Europe but because of China! We therefore need to focus on developing all potentially viable options for low-carbon energy, especially sources capable of contributing to baseload capacity, such as geothermal energy and nuclear fusion. Neither in Europe nor in the rest of the world will we have solved the energy problem once and for all by 2050! |

|

4.12 |

Offering incentives for investment: In view of the current crisis and the need to develop the complete supply system, investments in new technologies and infrastructure are urgently needed. Such investments boost optimism, helping to create jobs and confidence. This also applies to most investments in low-carbon technologies such as renewable energy sources, subject however to certain limitations and conditions, some of which have already been mentioned earlier in this opinion. In particular, policies should avoid prescriptions demanding specific technologies, as these could lead to further misallocation of limited resources (see above). |

|

4.13 |

General recommendation. The general recommendation is therefore to review the framework of regulations and conditions and to ensure they create a climate which stimulates research, encourages investment, favours innovation, supports the internal market and does not jeopardise the security of energy supply. Subsidies must focus on research, development and demonstration of technologies and systems. At the same time, the only support for renewable energy sources being competitive in the market should come from the criterion of CO2 avoidance costs (carbon pricing) (CESE 271/2008). At the same time all subsidies for fossil fuel consumption should be abolished. |

|

4.14 |

A level playing field for global competition. To ensure that this approach contributes enough to meeting global climate challenges without imposing additional competitive disadvantages at international level on European industry, countries in other parts of the world must urgently make similar efforts or agree on realistic joint targets, to ensure fair and comparable conditions for competition at global level. Despite the disappointments to date, the Committee supports continued efforts by the EU to achieve this. |

|

4.15 |

Europe going it alone. However, if these efforts fail, the question remains how long the EU can afford to continue going it alone and working towards radical targets without seriously undermining its own economic strength, thus depriving itself of the very resources it needs to prepare for climate change – which in that case would probably be inevitable – together with all its economic and political repercussions. |

Brussels, 17 April 2013.

The President of the European Economic and Social Committee

Henri MALOSSE

(1) OJ C 44, 11.2.2011, pp. 53-56.

|

10.7.2013 |

EN |

Official Journal of the European Union |

C 198/9 |

Opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee on the ‘Single European Sky II+’ (exploratory opinion)

2013/C 198/02

Rapporteur: Mr KRAWCZYK

On 24 January 2013 the European Commission decided to consult the European Economic and Social Committee, under Article 304 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, on the

Single European Sky II+

(exploratory opinion).

The Section for Transport, Energy, Infrastructure and the Information Society, which was responsible for preparing the Committee's work on the subject, adopted its opinion on 3 April 2013.

At its 489th plenary session, held on 17 and 18 April 2013 (meeting of 17 April), the European Economic and Social Committee adopted the following opinion by 188 votes to 2 with 3 abstentions.

1. Conclusions and recommendations

|

1.1 |

The completion of the EU Single European Sky (SES) is an inherent part of the process of improving the competitiveness and growth of the EU economy by further strengthening the European single market. Its objective is to provide better, more effective and reliable conditions of air travel to the European citizens. |

|

1.2 |

The continuing crisis in the EU aviation sector and particularly in the airline industry calls even more for the urgent implementation of the SES. Bringing European Air Traffic Management (ATM) services to a level of efficiency, in terms of performance, economics, quality, security and environmental protection that is comparable with global best practices is of utmost importance. |

|

1.3 |

In line with its previous opinions TEN/451 (20/06/2011) and TEN 354/355 (21/01/2009), the EESC fully supports the need for a timely and comprehensive implementation of the SES and its Air Traffic Management Research (SESAR) initiatives within the scope originally agreed upon in 2004 and 2009. The legal instruments provided to the European Commission by the EU regulations are sufficient to this goal. Due to the continuing crisis in the EU aviation sector and particularly in the airline industry, the objectives for 2025 could be reflected upon. |

|

1.4 |

The EESC regrets that most Member States to whom the performance targets were addressed have failed to comply with these targets without facing any effective legal consequences. The EESC also regrets that most of the Functional Airspace Block (FAB) initiative failed to deliver and that the binding deadline of 4 December 2012 was not met. |

|

1.5 |

In this context the EESC welcomes the Commission's plan to give further impetus to the SES through a new so-called SES II+ initiative. |

|

1.6 |

The EESC considers that the revision of the present SES legislative framework should not only focus on institutional developments and on improving legal clarity, but also on strengthening the following elements:

|

|

1.7 |

The European airline industry is in a very difficult economic situation which has already led to thousands of jobs being lost. The implementation of the SES and its improved efficiency are therefore also important for safeguarding jobs in this part of the aviation value chain. The 5th pillar of the SES is fundamental here in terms of adequately addressing the challenges regarding employment, worker mobility, changes in staff management and professional training. Social dialogue should, as a consequence, be strengthened and look beyond the pure ATM sector and be opened to the participation of other social partners than only Air Navigation Service Provider (ANSP) representatives, and should extend its scope to discussing the social consequences for workers in ATM, airlines, airports, and ways of safeguarding jobs in the wider EU aviation industry. |

|

1.8 |

Member States, including those being slow on SES implementation, should present their strategies towards the future development of their air transport sector. |

|

1.9 |

The EESC believes that the high level of safety achieved by EU aviation should remain of the utmost importance. It is vital to ensure that the necessary action to reach the economic goals further support the development of the safety level. |

2. Introduction

|

2.1 |

The completion of the Single European Sky (SES) project is an inherent part of the process of improving the competitiveness and growth of the EU economy by further strengthening the European single market. The SES aims to improve the overall efficiency of the way in which the European airspace is organised and managed. This includes reducing costs, improving safety and capacity and limiting the impact on the environment. Its objective is to provide better, more effective and reliable conditions of air travel to European citizens. |

|

2.2 |

Following the recent reports of Eurocontrol (ACE Benchmarking Report 2010, draft ACE Benchmarking Report 2011 and draft PRU Report 2011) it should be stated that the period 2007-2011 saw numerous changes. Consequently, any analysis of the overall variation in cost-effectiveness should not be done without taking into consideration the main events during this period. |

|

2.3 |

In 2010, the annual cost caused by the fragmentation of Europe's airspace amounted to EUR 4 billion. This includes 19.4 million minutes of delays due to en-route air traffic flow management (ATFM); in addition, each flight was on average 49 km longer than the direct flight route. At European level, the economic cost per composite flight-hour increased slightly from 2006 to 2009 (i.e. +1% p.a. in real terms); it rose significantly in 2010 (i.e. +4.6% in real terms) before falling in 2011 (-4.3%) prior to the SES II First Reference Period. In 2010, ATM/CNS provision costs fell by -4.8% in real terms, which was consumed by a sharp increase in the unit costs of ATFM delays (+77.5%), which, in contrast, fell by 42% in 2011. |

|

2.4 |

The significant variation in the total costs incurred by airlines for air navigation services, which in 2010 ranged from EUR 849 to EUR 179 i.e. a factor of over five, is of particular importance. In addition, the five largest Air Navigation Service Providers ANSPs, all of which operate under broadly similar economic and operational conditions, showed significant differences in their unit costs, which ranged from EUR 720 to EUR 466. This distribution sends out a clear signal that ATM is not optimised across Europe. |

|

2.5 |

The results of the SES I and SES II schemes (introduced in 2004 and 2009 respectively) demonstrate that the principles and general direction of the SES initiative are valid and that efforts have been made to optimise the ATM rules, which are beginning to bear fruit. However, these schemes have also revealed a number of weaknesses, largely due to the Member States' failure to provide a clear outline of their current aviation priorities. Their priorities range from such issues as creating value added for airspace users to maximising their own income from air operations as well as using aviation as a tool for regional and micro-economic development. As a result, ANS provision in Europe still shows major deficiencies in terms of its efficiency and quality, yet there is a lack of any clear explanation regarding this situation. In addition, the current institutional set-up is less than optimal as it includes numerous overlaps, gaps and a lack of any common direction among the various stakeholders. The SES institutional framework therefore needs to be strengthened. |

|

2.6 |

SESAR is the technological element of the SES. According to a study from the SESAR Joint Undertaking, the macroeconomic impact of SESAR could generate additional GDP of EUR 419 billion for the European economy and create some 320 000 jobs. The completion of the SESAR programme will require major investments from all parts of the aviation value chain participants, which are difficult to justify unless an acceptable return on investments can be established based on the synchronised deployment of air and ground elements including airspace users, ANSPs and airports. The institutional framework needs to evolve to ensure the successful deployment of SESAR; at the same time, robust cost-benefit studies have to be conducted by all co-operating parties for the sequence of investment projects along the complete aviation value chain. |

|

2.7 |

The European Commission therefore plans to issue a legislative package (SES II+) which builds on the existing SES initiatives and which will seek to further improve cost efficiency, capacity, safety and regulatory quality. |

|

2.8 |

Based on the information received from the European Commission, the SES II+ initiative will aim to:

|

3. General comments

|

3.1 |

In line with its previous opinions TEN/451 (20/6/2011) and TEN 354/355 (21/1/2009), the EESC fully supports the need for a timely and comprehensive implementation of the EU Single European Sky and SESAR initiatives: The sense of urgency ought to be much higher, since the economic situation of many European airlines is currently very bad. |

|

3.2 |

The EESC expects, that the implementation of the SES package will be fully completed, i.e. within the scope originally agreed upon in 2004 and 2009. The legal instruments provided to the European Commission by the EU regulations are sufficient in this respect. |

|

3.3 |

In this context the EESC welcomes the Commission's plan to give further impetus to the SES initiative. It will be essential for all EU Member States to honour their earlier political commitments to timely deliver full implementation of the SES. It is also of fundamental importance that the European Commission maintains strong leadership and responsibility throughout the entire implementation process. |

|

3.4 |

Considering relatively poor results of the implementation of the Single European Sky (SES) following the entry into force of SES I in April 2004 and of SES II in December 2009, the EESC considers that the revision of the present SES legal framework should not only focus on institutional developments but also on strengthening the following elements:

|

4. Specific comments

|

4.1 |

The EESC regrets that a significant number of Member States to whom the targets were addressed have failed to comply with the performance targets without any effective legal consequences. The recently submitted national performance plans demonstrate that these Member States have watered down their targets even further. Therefore, in order to ensure that the Member States create bigger synergies within their Functional Airspace Blocks (FABs), and ultimately between those, there is clearly a need for ambitious performance targets combined with an effective sanction mechanism as well as unambiguous and clear Member State strategies which are supported by the necessary pan-European harmonisation of the law in this area. The SES should stimulate the development of the necessary common European legal instruments (i.e. civil law) and a common approach the towards the European air defence sector. |

|

4.2 |

The EESC feels that more powers should be given at EU and FAB level to help overcome the current problem whereby Member States focus on protecting their own national ANSPs or using them as national economy tools rather than on creating value added for airspace users and customers/passengers. EU-wide performance targets should help ensure that the SES high-level goals for 2020 are achieved; (namely, compared to 2005, a three-fold increase in capacity where needed, a 10% reduction in the environmental impact of flights and a reduction of 50% in the cost of ATM services for airspace users) and lead to progress towards the defragmentation of national air spaces. |

|

4.3 |

The EESC stresses the need to safeguard the independence of the EU Performance Review Body (PRB). Its activities should be detached from those of Eurocontrol and be transferred to a full EU body under the Commission's responsibility. The EU should also give the PRB a stronger role in the process of establishing EU wide performance targets and national performance plans. Overrepresentation by ANSPs should not be continued. |

|

4.4 |

The EESC feels that penalties and incentives should be established at EU level to prevent non-compliance with performance targets and to ensure that such targets remain separate from national interests. In particular, it should be envisaged to link the rate of return on investments made by the ANSP and equity of their shareholders to the achievements of the Performance Scheme. |

|

4.5 |

The EESC regrets that most of the Functional Airspace Block (FAB) initiative failed to deliver and that the SES II legal deadline of 4 December 2012 was not met. New impetus should be given to FAB initiatives through more top-down steering at EU level. A more top-down approach should ensure that FABs deliver real benefits rather than the current window dressing exercises. In this context, the SES Network Manager should be given the power to propose and implement specific projects from FABs to optimise FAB governance, airspace, along with technical and human resources, based on clear deadlines. Penalties should be established in cases of non-compliance. The Network Manager and interested airspace users should also be given an observer's seat at the FAB's main bodies. |

|

4.6 |

The contribution of the Member States to the EU Single European Sky Committee has been dominated by national interests rather than EU goals. The latest decision of that Committee on the 2015-2019 performance and charging scheme is another setback in SES implementation. The EESC proposes that both airspace users and ANSPs should be given an observer's seat and the right of initiative in all SES Committee activities. |

|

4.7 |

The EESC once again welcomes the Commission's intention to take a fresh look at the unbundling of ancillary ATM services as a way of improving customer focus and efficiency. The EU regulatory tools should be used to speed up the unbundling process. In this context, the EESC regrets that the Commission failed to meet the legal deadline of 4 December 2012 to prepare and submit a study to the European Parliament and to the Council evaluating the legal, safety, industrial, economic and social impact of the application of market principles for the provision of communication, navigation, surveillance and aeronautical information services and taking into account developments in the functional airspace blocks and in available technology. |

|

4.8 |

The EESC feels that the SES II+ legislation should address the separation between core bundled ANSPs and ancillary services such as Communication Navigation Surveillance (CNS), Meteorological Services (MET) and training, opening up the market for these services, which could result in increased efficiency, higher quality and an overall reduction in costs. The EESC notes that the importance of further liberalising ancillary services was also stressed in the impact assessment of the SES II+ legislation and the High-Level conference on SES in Limassol. Although current legislation allows for unbundling at national level, Member States are still rather hesitant about using this tool to increase performance. Wherever possible, the provision of CNS and MET services should be subject to market conditions and tendering procedures. In addition, market conditions should not be combined with a designation mechanism on the same market, otherwise the latter will dominate. All local and substantial cross subsidies should be prohibited. |

|

4.9 |

Eurocontrol's new concept of centralised services should be given due consideration, provided these services are based on acceptable business cases that have been endorsed by the operational stakeholders (airlines, ANSPs and airports) and they are based on open calls for tender in view of fixed-term contracts being awarded to those companies that have provided the best offer. |

|

4.10 |

The EESC highlights the fact that the defragmentation of ANS facilities could be made possible through the use of consolidating centres. The so-called "Virtual Centre" concept could represent a useful starting point. This approach provides for the use of fully standardised methods of air traffic service units operating from different locations which use fully standardised but scalable methods of operation, procedures and equipment in such a manner that airspace users consider them to be a single system. This effect has also been clearly visible in the current set of SES programmes, such as SERA and SESAR. These arrangements support full technical and operational interoperability among participating ANSPs, which, in turn, allows sectors assigned to a specific unit to be temporarily transferred under the operational responsibility of another. Consequently, this would make it possible to optimise the use of Area Control Centres (ACC) overnight and to ensure optimum performance at any given time. |

|

4.11 |

The EESC therefore feels that the SES II+ legislation should provide an appropriate regulatory framework to lead and steer the implementation of standardisation measures in a consistent and coherent manner. A common steering body should be established within the FABs in order to ensure consistent and coordinated deployment. Standardisation measures represent a realistic and effective means of achieving the EU-wide performance targets. |

|

4.12 |

The EESC welcomes the Commission's plans to increase the tasks and powers of the SES Network Manager. In this context, it will be essential to allow airspace users to participate in strategic decisions affecting network performance and to give ANSPs a role in decision-making on local performance. |

|

4.13 |

The EESC takes note of the fact that the Commission plans to expand the scope of the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) to deal with all technical regulation and oversight including areas not related to safety. The EESC agrees that this may be the right approach but expresses concern that, even with the support of the risk-based priorities concept, overloading the EASA with new tasks could create more problems than benefits and focus the EASA's attention away from its core safety mission. The EESC therefore feels that the expansion of EASA's scope of activity should not be a priority at this point in time. Instead, the EESC feels that potential overlaps between the EASA and SES frameworks could be solved through appropriate coordination mechanisms between the EASA, Eurocontrol and the Commission without necessarily changing the institutional framework. |

|

4.14 |

The role of Eurocontrol in operational SES implementation is very important. To ensure the future efficient performance of centralised services like those provided by the Network Manager, a revision of the current Eurocontrol convention will be required. |

|

4.15 |

With regard to SESAR, the EESC stresses the importance of securing sufficient public funding to support the synchronised deployment of ground and air elements. Moreover, the operational investors (airspace users, ANSPs and airports) should be given a prominent role in the governance of SESAR deployment when deciding on the priorities, based on clear business cases. The EESC stresses the importance of the implementation of SESAR as a European key infrastructure project. The Committee expresses it highest concern about possible cuts in the Connecting Europe Facility budget that may influence the ability to carry this implementation forward. It is also of utmost importance to work out possible future financing models for the military deployment of SESAR. |

|

4.16 |

The EESC does not support the Commission's proposal to introduce price modulation for congested routes. This would not actually lead to any improvement in the use of airspace capacity; moreover, as its introduction could force aircraft operators to fly longer routes it would also run counter to the EU's goals of curbing emissions as a means of combating climate change. Furthermore, such a system would also be unfair since aircraft operators already pay a price for congestion due to the indirect costs of delays. Such an approach would lead to a dual penalty which would be totally unacceptable especially since aircraft operators use route charges to finance infrastructure upgrades, which should ultimately reduce congestion. |

|

4.17 |

Instead, the EESC believes that price modulation should focus on motivating aircraft operators to purchase the equipment needed to improve the overall performance of the Air Traffic Management System. This could be achieved by using public funds to reduce user charges for those aircraft operators which invest early in SESAR technologies. This approach could then be accompanied with further measures such as the Best Equipped, Best Served Concept, which is fully supported by EESC. |

5. Social dialogue

|

5.1 |

The European airline industry is in a very difficult economic situation which has already led to thousands of jobs being lost. The implementation of the SES and its improved efficiency are therefore also important for safeguarding jobs in this part of the aviation value chain. The 5th pillar of the SES is fundamental here to adequately addressing the challenges regarding employment, worker mobility, changes in staff management and professional training. Social dialogue should, as a consequence, be strengthened and look beyond the pure ATM sector and be opened to the participation of other social partners than only Air Navigation Service Provider (ANSP) representatives, and should extend its scope to discussing the social consequences for workers in ATM, airlines, airports, and ways of safeguarding jobs in the wider EU aviation industry. |

|

5.2 |

The EESC strongly believes that effective on-going social dialogue is essential to help the transition process. If staff members are not fully engaged in this transition, the risk of failure will increase significantly. In particular, new technologies and operational concepts developed by SESAR will change the traditional role of air traffic controllers, who will act as air traffic managers. |

|

5.3 |

It is important that the social dialogue within the SES framework reflects the concerns of all the parties involved in the implementation. The current dominance of ANSP representatives is therefore not justified and risks to further discriminate other important industry players. |

Brussels, 17 April 2013.

The President of the European Economic and Social Committee

Henri MALOSSE

|

10.7.2013 |

EN |

Official Journal of the European Union |

C 198/14 |

Opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee on ‘Growth Driver Technical Textiles’ (own initiative opinion)

2013/C 198/03

Rapporteur: Ms BUTAUD-STUBBS

Co-rapporteur: Ms NIESTROY

On 12 July 2012 the European Economic and Social Committee, acting under Rule 29(2) of its Rules of Procedure, decided to draw up an own-initiative opinion on

Growth Driver Technical Textiles

(own-initiative opinion).

The Consultative Commission on Industrial Change (CCMI), which was responsible for preparing the Committee's work on the subject, adopted its opinion on 12 March 2013.

At its 489th plenary session, held on 17 and 18 April 2013 (meeting of 17 April 2013), the European Economic and Social Committee adopted the following opinion by 172 votes in favour with 6 abstentions.

1. Conclusions and recommendations

|

1.1 |

The sector of technical textiles which registered positive economic and employment trends in the EU is an example of "traditional sectors" able to "reinvent itself" on new business model fully suited to the needs of the new industrial revolution (more smart, more inclusive and more sustainable). |

|

1.2 |

Textile Materials and Technologies are key innovations that could respond to a huge variety of societal challenges. Technical textiles are enablers in other industries by proposing and offering:

|

|

1.3 |

The European Economic and Social Committee draws the attention of the European Commission and of the European Parliament to the major factors of success that need to be encouraged in order to foster the growth of this promising sector:

|

2. The sector of technical textiles in the EU

2.1 Definition of the sector and major markets

2.1.1 Technical textiles are defined as textiles fibres, materials and support materials meeting technical rather than aesthetic criteria, even if, for certain markets like work wear or sports equipment, both types of criteria are met.

Technical textiles bring a functional answer to a wide range of specific requirements: lightness, resistance, reinforcement, filtration, fire-retardancy, conductivity, insulation, flexibility, absorption and so on.

Thanks to the nature of the fibres (polyester, polypropylene, viscose, cotton, carbon, glass, aramid, etc.), as well as the choice of the most relevant manufacturing techniques (spinning, weaving, braiding, knitting, non-woven …) including finishing processes (dyeing, printing, coating, laminating …), technical textile producers are able to propose textile solutions offering the mechanical, exchange or protective properties suited to the specific needs of the final users.

Hence, the definition does not depend on the raw material, the fibre or the technology used, but on the end-use of the product itself.

The Messe Frankfurt, which is the world wide leader of technical textiles trade fairs with "Techtextil", has identified 12 major markets (1):

In fact technical textiles are part of a wider field that David Rigby Associates terms the "engineering of flexible materials" (2), including foams, films, powders, resins and plastics. They are also a key component of composites which could be defined as a combination of two or more materials differing in form or composition with, in general, a matrix that could be in fibres, and a reinforcement stronger than the matrix.

2.2 Facts and figures

2.2.1

According to the latest EURATEX estimates, in 2011 the EU T&C industry reached a turnover of EUR 171.2 billion thanks to its nearly 187 000 businesses employing more than 1.8 million workers. The size of the companies is quite low (textile: 13, clothing: 9, total: 10) which explains why they principally trade within the internal market while the Community Extra-EU exports reached EUR 38.7 billion or 22.6% of the global sales.

|

2011 |

Household Consumption (EUR bn) |

Turnover (EUR bn) |

Companies (.000) |

Employment (.000 pers.) |

Extra-EU Imports EUR (bn) |

Extra-EU Exports EUR (bn) |

Trade Balance (EUR bn) |

|

Clothing |

304,0 |

77,5 |

131,4 |

1 117,9 |

67,7 |

18,4 |

–49,32 |

|

Textile |

166,5 |

93,9 |

55,5 |

716,4 |

25,4 |

20,3 |

–5,06 |

|

TOTAL |

470,5 |

171,4 |

186,9 |

1 834,3 |

93,1 |

38,7 |

–54,37 |

|

Source: EURATEX revised data on members data and EUROSTAT - 2011 |

|||||||

2.2.2

In its previous opinions on the textiles sector, the EESC has pointed to technical textiles as one of the most promising field of activity for European textiles companies, especially SMEs. EU industry plays a leading role in developing technical textiles already (3). This industry, thanks to its high innovation capacity, offers a potential for direct and indirect jobs and growth in the EU.

2.2.2.1 A subsector of textiles

The technical textiles industry in the EU represents, according to EURATEX, roughly 30% of the total turnover in textiles (excluding clothing), i.e. EUR 30 billion (it could be a higher market-share in some Member States like Germany: 50%, Austria: 45%, or France: 40%), 15 000 companies and 300 000 employees. Certain analysts consider that other parts of the EU industries should be added: a part of the textile machinery industry as well as the "textile" part of the manufacturing activities of other sectors like tyres or the revetment of roads or buildings with geotextiles. This is why the size of the EU technical textile industry as a whole could be even larger (up to EUR 50 billion).

2.2.2.2 The EU in world-wide fibre consumption

Worldwide, the development of technical textiles production is illustrated by fibre consumption. Technical textiles consumed worldwide about 22 bn tonnes of fibres in 2010, representing 27.5% of a total consumption of 80 bn tonnes for all textile and clothing applications. Europe accounts for about 15% of the global consumption of technical textiles, as evaluated by CIRFS (European Association for man-made fibres).

|

|

Fibre consumption (000 tonnes) |

|

EU |

3 437 |

|

Americas |

4 111 |

|

China |

7 100 |

|

India |

4 020 |

|

Rest Of the World |

3 812 |

|

World Wide |

21 880 |

|

Sources: CIRFS, Edana, JEC |

|

The EU market share in value is more important: it varies from 20% to 33% of the main sub-segments of the USD 230 billion world technical textile market including non woven and composites.

WORLD TECHNICAL TEXTILE MARKET STRUCTURE - 2011

|

2011 |

Mt |

Billion USD |

EU-Share |

Growth rate |

|

Technical textiles |

25,0 |

133 |

20 % |

+3,0% |

|

Non woven |

7,6 |

26 |

25 % |

+6,9% |

|

Composites |

8,0 |

94 |

33 % |

+6,0% |

|

Total |

40,6 |

253 |

|

|

|

Source: INDA, Freedonia Group, IFAI, JEC |

||||

2.2.2.3 The EU-27 technical textiles exports to world in 2011

The top five exporters of technical textiles (DE, IT, FR, UK, BE) do represent 60% of the total exports to the world by the Member States. Moreover, the Member States whose technical textiles represent the highest share of their textiles exports (excluding clothing) are Finland, Denmark, Sweden, Czech Republic and Hungary (See Appendix 1: Share of Technical Textiles in 2011 textiles exports to world by Member State).

2.2.3

2.2.3.1 The growth of non-wovens and of composites

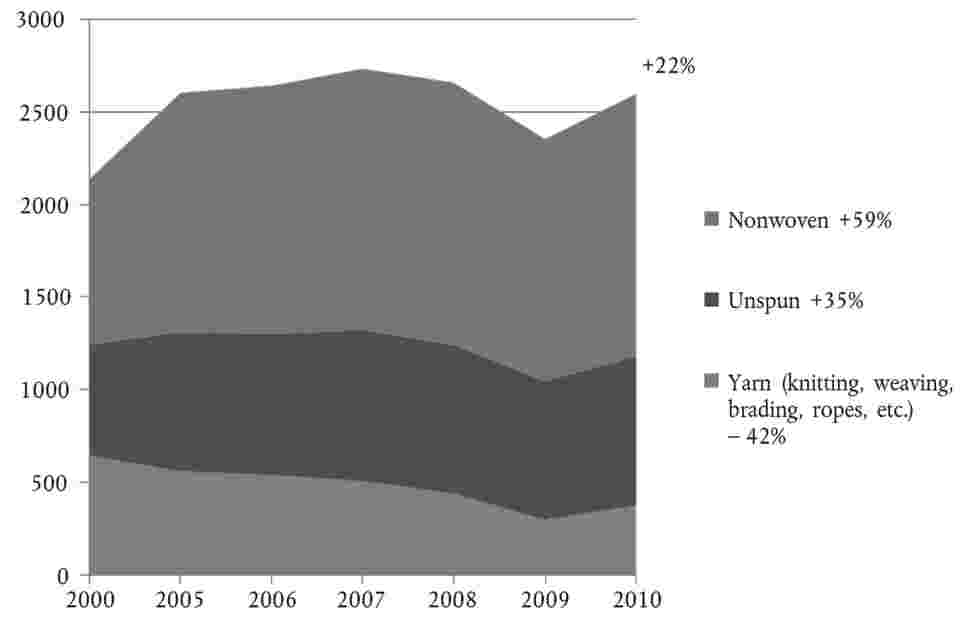

In the past decade, the sector has grown by 22% as shown in the following figure presenting the development of fibre consumption by use (excluding fibreglass).

The technical textile sector is undergoing significant industrial change with the growing importance of new applications (medical, sport and leisure, aeronautics, environment), and a radical move from traditional technologies (knitting, weaving, braiding etc.) to more recent ones (like composites or nonwoven technologies).

Growth in Europe is mainly driven by two technologies:

|

— |

Nonwoven with a growth rate of 60% over the past decade. |

|

— |

Composites with a growth rate of 75% over the past decade. |

2.2.3.2 A key position on three markets

"The top three applications areas in Europe also accounted for over 50% of total consumption, but in this case the areas were Mobiltech, Hometech and Indutech." (David Rigby Associates (4)).

2.2.3.3 Euromed partnership

The EU textile and clothing industry has established a successful industrial partnership with the Euromed countries such as Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt in the fashion pipe line. Thus, lies for the future the opportunity to promote the EU investments on some technical textiles markets that are more mature, have a lower technological content, and are more sensitive to the price pressure from Asia.

In this regard, the situation of Turkey should be considered separately. Turkey is a key-player in the Euromed Fashion pipeline and has a powerful integrated textile industry, from raw material (cotton or synthetic fibres) to garments or home textiles. An increasing number of Turkish companies are active on technical markets (10% to 15%) and domestic consumption is dynamic.

2.2.3.4 High innovation capacity sector

Recent research in Germany did confirm that the technical textiles companies belonging to this cross-sectoral branch and material supplier to several industrial segments have a high innovative capacity realising more than 25% of their turnover from new innovative products, ranking third after automotive and electronics industries. (Source presentation of Mr Huneke during the 1st EURATEX Convention, Istanbul).

2.3 A SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) analysis

2.3.1

2.3.1.1 Strengths:

|

— |

an increasing level of R&D and innovation within the companies, whatever their size; |

|

— |

efficient collective tools to support innovation at national level (textiles clusters, R&D centres …), particularly in Germany, France, Belgium, Italy, Spain, Netherlands, Poland; |

|

— |

efficient collective tools at EU level: the T (Textile) and C (Clothing) technology platform with many collaborative projects that have led to cross-fertilisation between applicative markets, textile companies and researchers; a European network involving the main textile technology institutes (Textranet) university networks (AUTEX) as well as a network involving the main innovative textiles regions; |

|

— |

EU leaders in growing markets (Freudenberg, or Fiberweb for the nonwovens for instance); |

|

— |

leading position of the EU in textile machinery manufacturing with 75% of the global market; |

|

— |

the diversity of end-uses which is an asset in a period of low growth; |

|

— |

a strong encouragement for personal protective equipment (PPE) considered by the EC as one of the six leading markets; |

|

— |

better financial ratios in general than the other textiles and clothing companies (more value-added per employee, higher cash flow, higher level of margin …); |

|

— |

control of the leading worldwide trade fair (Techtextil). |

2.3.1.2 Opportunities:

|

— |

growing needs of textiles solutions from the end-users: comfort and monitoring solutions for active life style, carbon emission reduction in transport (through reduced weight) and building (through thermal insulation), improvement of medical technology (nosocomial disease prevention, implants, health monitoring) …; |

|

— |

close cooperation between producers and customers in order to address very specific needs ("tailor-made solutions") and demand-driven innovation; |

|

— |

growing demand for recyclability improvement, like for instance the replacement of foam by nonwovens, composite materials and in-vehicle cabin air filters; |

|

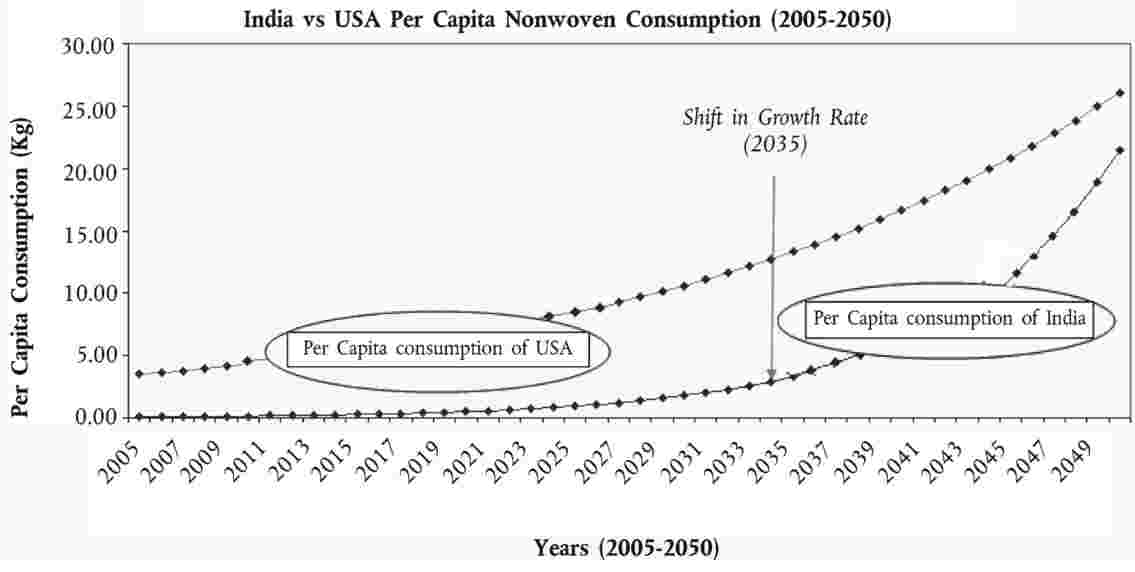

— |

quick growth of technical textile consumption per capita worldwide and especially in China, India and Brazil. |

2.3.2

2.3.2.1 Weaknesses:

|

— |

small and medium-sized companies with limited capacity for investment; |

|

— |

more difficult access to credit; |

|

— |

lack of attractiveness of the textile industry for young graduates; |

|

— |

decline in production of natural and man-made fibres in the EU, leading to difficulties in innovating with the low number of grades of fibres available and an increasing risk of dependencies on imports; |

|

— |

at the moment low recyclability of technical textiles compared to traditional materials; |

|

— |

a high energy-intensive industry; |

|

— |

specialisation on mature applicative markets, such as Mobiltech (with the critical situation of the EU car manufacturing industry) or Hometech particularly for carpets, furnishing fabrics and mattresses. |

2.3.2.2 Threats:

|

— |

scarcity of raw materials and increasing prices (mainly synthetic, regenerated or inorganic fibres, polymers, spun yarns and filament yarns); |

|

— |

increase in energy costs (gas and electricity) in the EU that could lead to a relocation in the United-States or in Asia of the production plants for the more energy-intensive producers (man-made fibres, non woven, dyers and finishers …); |

|

— |

growing competition from emerging countries and increasing market access barriers to those countries. Asia is already the first production region in tonnage in 2010 having multiplied by 2.6 times its production value; |

|

— |

growing pressure on prices, particularly on mature markets; |

|

— |

increasing risk of counterfeiting and copies. |

3. The contribution of this dynamic sector to the challenges of the 2020 strategy

3.1 A smart growth

A smart growth will be based on a more innovative EU industry with a more efficient use of energy, new materials, ICT (Information and Communication Technology) support, and competitiveness on the part of companies, including SMEs.

The technical textiles sector can contribute proportionally to this smart growth in various ways:

|

— |

promoting best practices of transfer of technologies from one sector to another (cross-fertilisation); |

|

— |

undertaking efforts to increase the energy-efficiency of the production; |

|

— |

the ability to combine technological innovation and non-technological innovation: a lumbar belt should be efficient but also nicely designed for the patient; |

|

— |

the capacity to foster creativity in the conception, the use and the end of life of the products/materials; |

|

— |

the experience of upgrading the qualification of employees in order to conquer new markets …; |

|

— |

a dissemination of ICT in the every day life thanks to the smart textiles which are textiles communicating with their environment: "smart clothing" for elderly people monitoring and conveying critical physiological data to hospitals will help them to stay at home for example. |

3.2 An inclusive growth

The EU technical textiles sector showed in a recent past a positive pace for job creation in many Member States with already some cases of labour and skills shortage that should be tackled.

An inclusive growth in the EU will maintain and develop our social model based on a high level of standards, a tradition of social welfare and a strong tradition of social dialogue. Vulnerable industries, territories and people should pay a particular attention in the EU policies and at national level in order to ensure that they benefit from economic growth, technological progress and innovation in their every day life.

The technical textiles sector can contribute at its scale in various manners to this inclusive growth:

|

— |

the ability to put on the market suitable and innovative goods and services for disabled, sick or elderly people: tailor-made garments, anti-fall garments, specific equipment for sports and leisure; |

|

— |

the ability thanks to customisation to bring answers to demographic and social changes that generate increased demand for more sophisticated and personalised products and services (see some projects in the Prosumer.net - European Consumer Goods Research Initiative). |

3.3 Sustainable growth

Sustainable growth in the EU means an energy- and resource-efficient economy with a capacity to meet its commitments in the fight against climate change and upcoming resource scarcity. The former is usually coined as "low-carbon economy", which refers to reducing CO2 emissions. However, the technical textiles sector demonstrates a first example for a potential move towards an economy with carbon as resource.

The technical textiles sector can contribute proportionally to a sustainable growth in three major ways:

|

— |

by reducing emissions of CO2 thanks to lighter materials in transports (composites for aeronautics and carbon fibres for cars); |

|

— |

by offering concrete textiles solutions, for example in the fields of filtration, reinforcement and insulation for improving the energy efficiency in the housing and building sectors; |

|

— |

by recycling PET from plastic bottles to produce polyester. |

For the potential sustainable branding of technical textiles, EU companies should be encouraged to:

|

— |

consider eco-design when designing products and ways of production; |

|

— |

perform life-cycle assessments (LCAs) of their products, which will play an increasingly important role in the future because until now traditional materials like metals are often cheaper to recycle. |

Three main issues related to carbon fibres are pending:

|

— |

the first one is to develop, in anticipation of the end of petroleum age, a EU recyclable carbon fibre based on natural fibres (5); |

|

— |

the second is to develop methods for recycling that would allow the complete recycling of textiles consisting of blended fabrics (80-90%); |

|

— |

the third one, of a more ambitious nature, will be to support industry and the scientific community in developing suitable processes for using carbon from CO2 as resource, e.g. by transformation through accelerated photosynthesis or other approaches. Research is already undertaken in the context of other applications, but should be intensified (towards a "CO2-economy" (6)). |

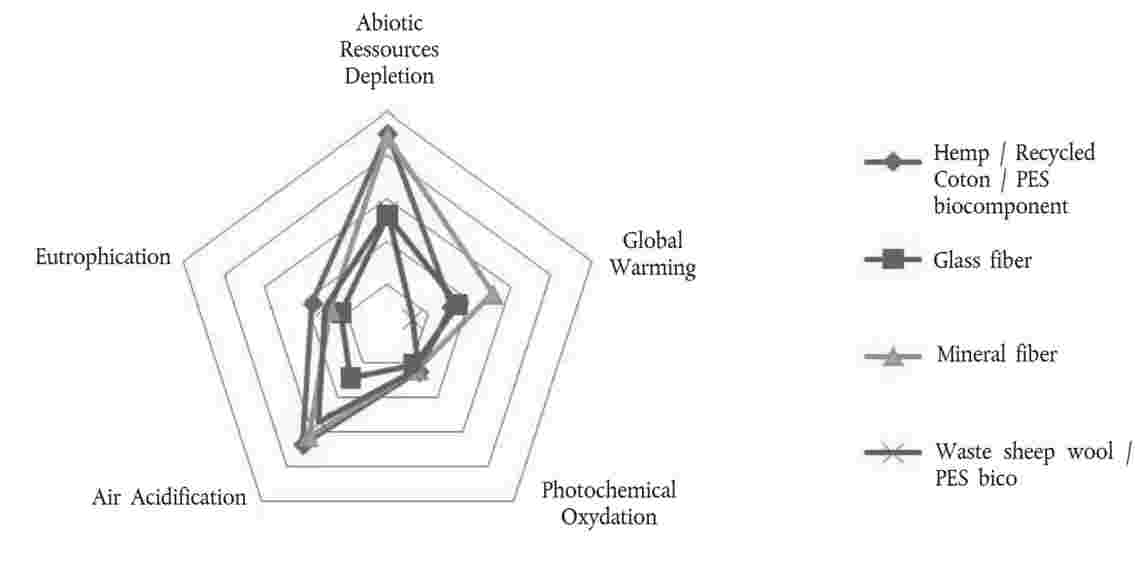

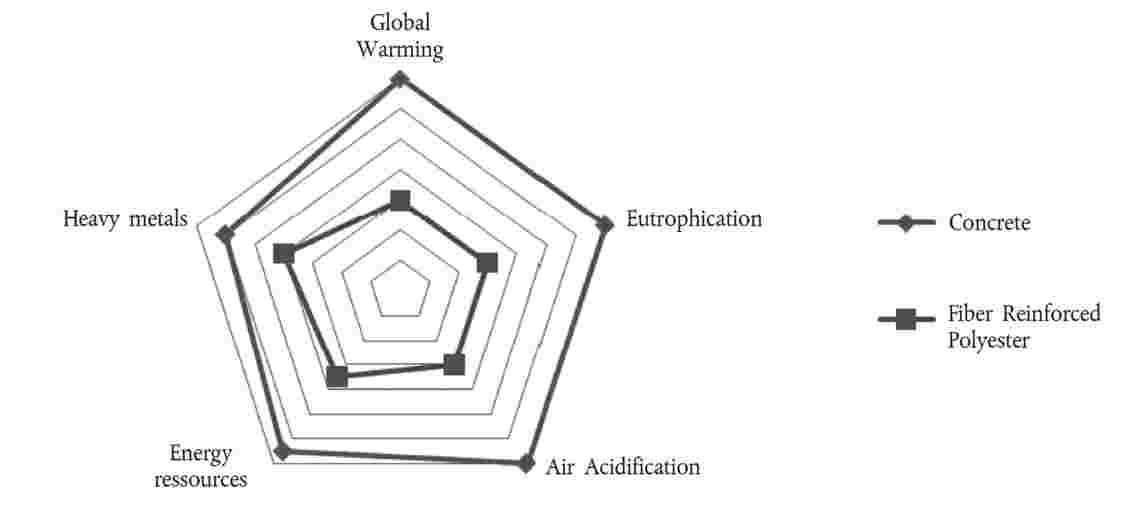

[See in Appendix 2 a qualitative comparison of the environmental impacts of traditional materials versus technical textiles in 3 examples.]

4. The key factors of success that need to be encouraged at EU level

4.1 Upgrading and transmitting skills and know-how