|

THE COURT’S OBSERVATIONS

|

THE COMMISSION’S REPLIES

|

|

INTRODUCTION

|

|

|

3.1.

|

Each year, in this chapter, we analyse a number of aspects relating to performance: the results achieved by the EU budget, which is implemented by the Commission in cooperation with the Member States (1). This year we have looked specifically at:

|

(i)

|

the use of performance information for decision-making by the Commission,

|

|

(ii)

|

selected results from our 2017 special reports on performance,

|

|

(iii)

|

the Commission’s implementation of the recommendations we made in our special reports published in 2014.

|

|

|

|

3.1.

|

The Commission notes that most key decisions in relation to the EU budget are taken by the budgetary and legislative authority, i.e. the European Parliament and the Council, on the basis of proposals from the Commission. This applies both to decisions on the annual budgetary procedure and in relation to the design and revision of the Multiannual Financial Framework and sectoral financial programmes.

|

|

|

PART 1 — DOES THE COMMISSION MAKE ADEQUATE USE OF PERFORMANCE INFORMATION IN DECISION-MAKING?

|

|

|

|

|

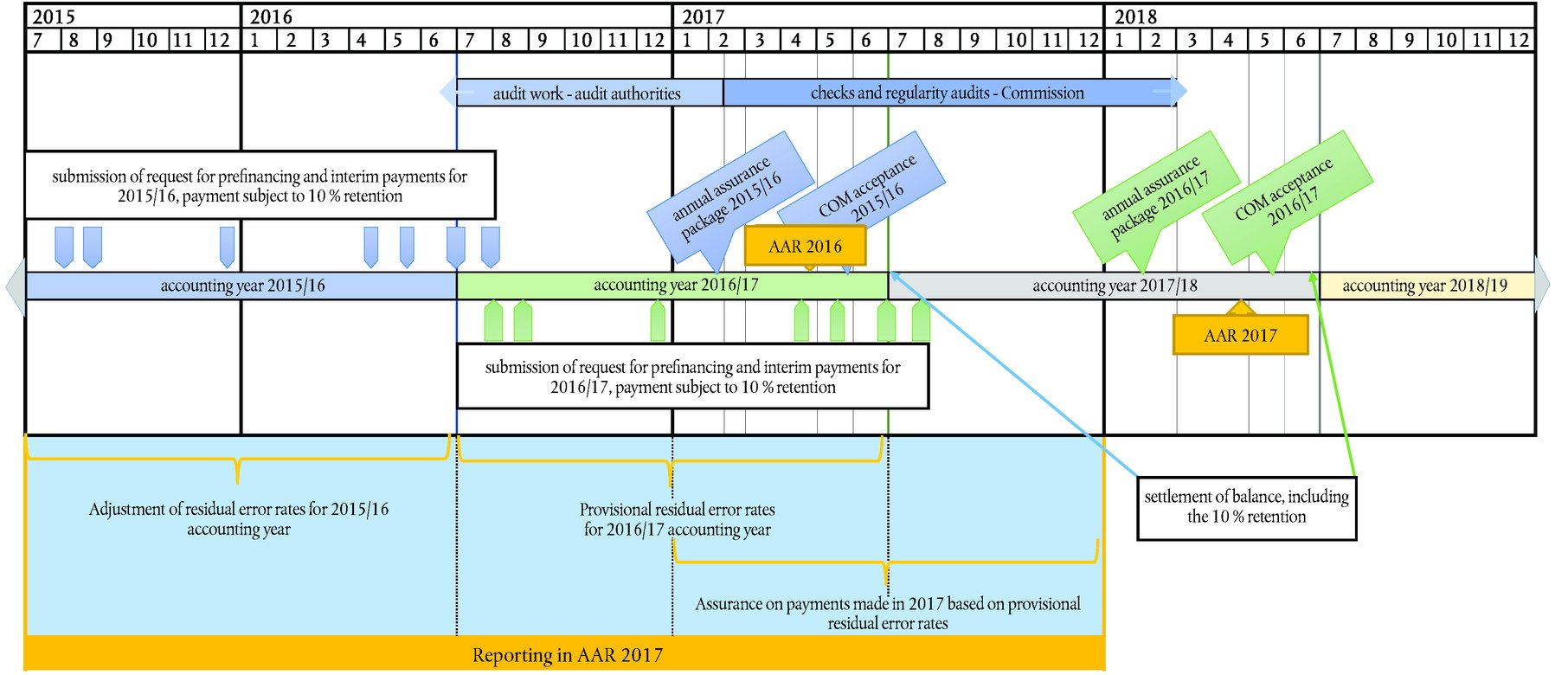

3.2.

|

Last year, we reviewed how the Commission’s approach to performance reporting compared with good practice. As it is important for an organisation to have good procedures for performance reporting and to improve them continuously, it is important to use the information generated from performance reporting to manage activities, optimise results and make adjustments to management systems and to strategic planning processes, etc. The way in which this information is used influences the organisation's long-term success in implementing performance management.

|

|

|

|

3.3.

|

According to the Commission, performance management is an ongoing systematic approach to improving the effectiveness, efficiency and results of operations through better planning, regular monitoring and evidence-based decision-making (2). The Commission’s ‘EU Budget Focused on Results’ initiative, which was launched in 2015, includes different work streams and objectives, one of which is to support decision-making with meaningful performance information (3). The better regulation guidelines (4), which were launched in 2015 and updated in July 2017, stipulate that all available evidence should be used as a basis for designing EU policies and laws that achieve their objectives in an open, transparent and cost-efficient manner.

|

|

|

|

THE COURT’S OBSERVATIONS

|

|

|

3.4.

|

To assess if the Commission adequately uses performance information for decision-making, we took the following steps.

|

(i)

|

We conducted a documentary review on the use of performance information for decision-making, including reports by supreme audit institutions (5), the OECD, governments, and academics from inside and outside the EU.

|

|

(ii)

|

We reviewed the latest performance reports published by six Directorates-General (DGs) (6), including ten of their recently published impact assessments and evaluations. We selected these DGs because they were reasonably representative of the Commission as a whole. This was because of their varied characteristics (in terms of management mode, cooperation with agencies, type of activity, etc.).

|

|

(iii)

|

We interviewed thirty heads of unit and directors in these six DGs to gain additional information on the use of performance information in decision-making in the DG.

|

|

(iv)

|

We carried out a survey on the use of performance information in decision-making in these six DGs. The survey was aimed at managers in these DGs who were involved in managing policies, programmes or projects: heads of unit, directors, deputy directors-general and directors-general. The final response rate was 57 %, from a target population of 240.

|

|

|

|

|

Scope

|

|

|

3.5.

|

Our review covered the use of performance information at the Commission in relation to spending programmes and the development, implementation and evaluation of policies. We excluded the following aspects from the scope of our audit.

|

|

|

|

(i)

|

The use of performance information in relation to the Commission’s administrative management of staff and other resources, in order to focus on the delivery of results for policies and programmes.

|

|

|

|

(ii)

|

The use of performance information by the budgetary authority

(7); the OECD (8) and other researchers (9) had already carried out work in this area.

|

|

|

|

Section A — There are certain limits to how much use the Commission can make of performance information

|

|

|

The EU’s multiannual financial framework lacks flexibility to use performance information

|

|

|

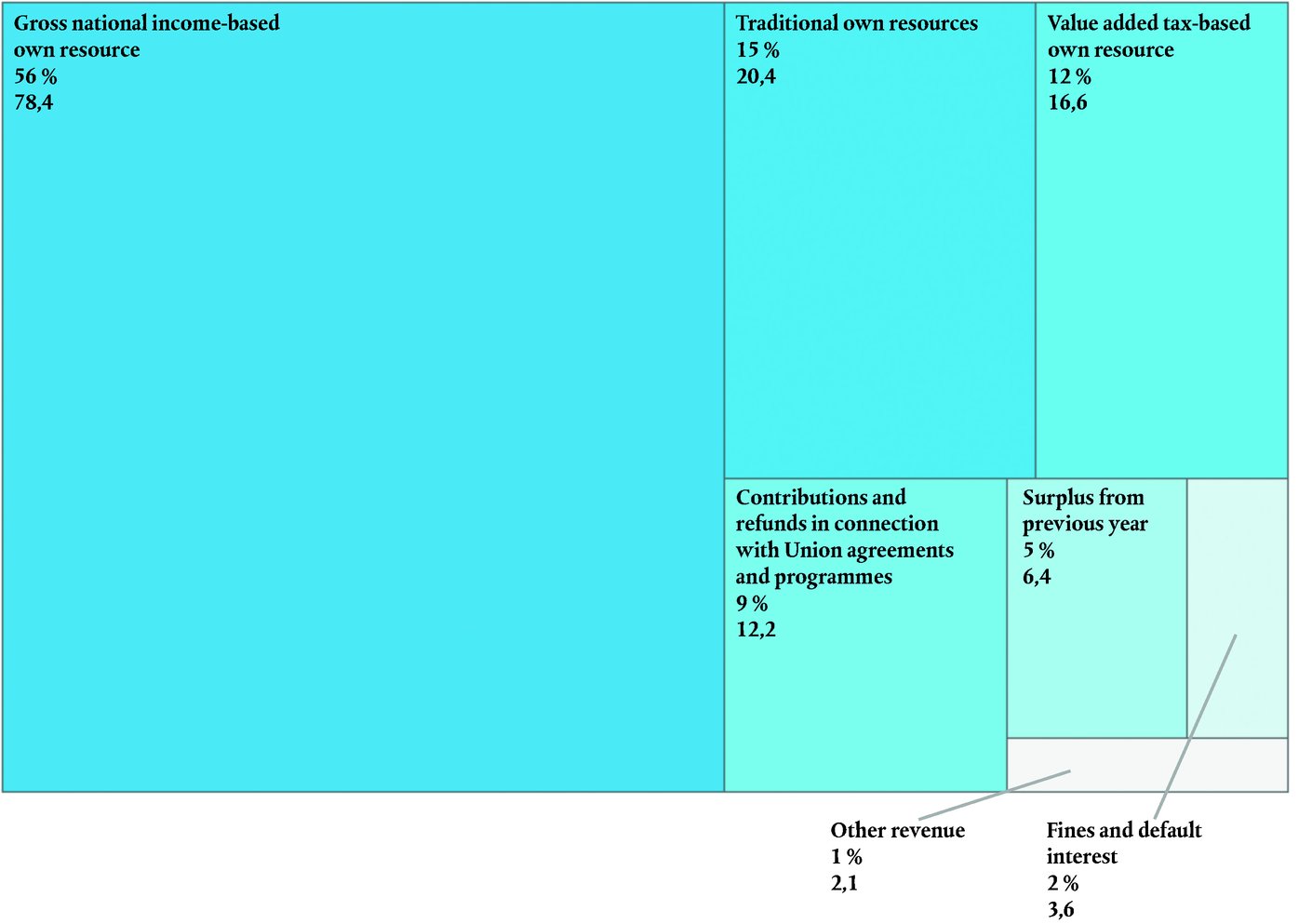

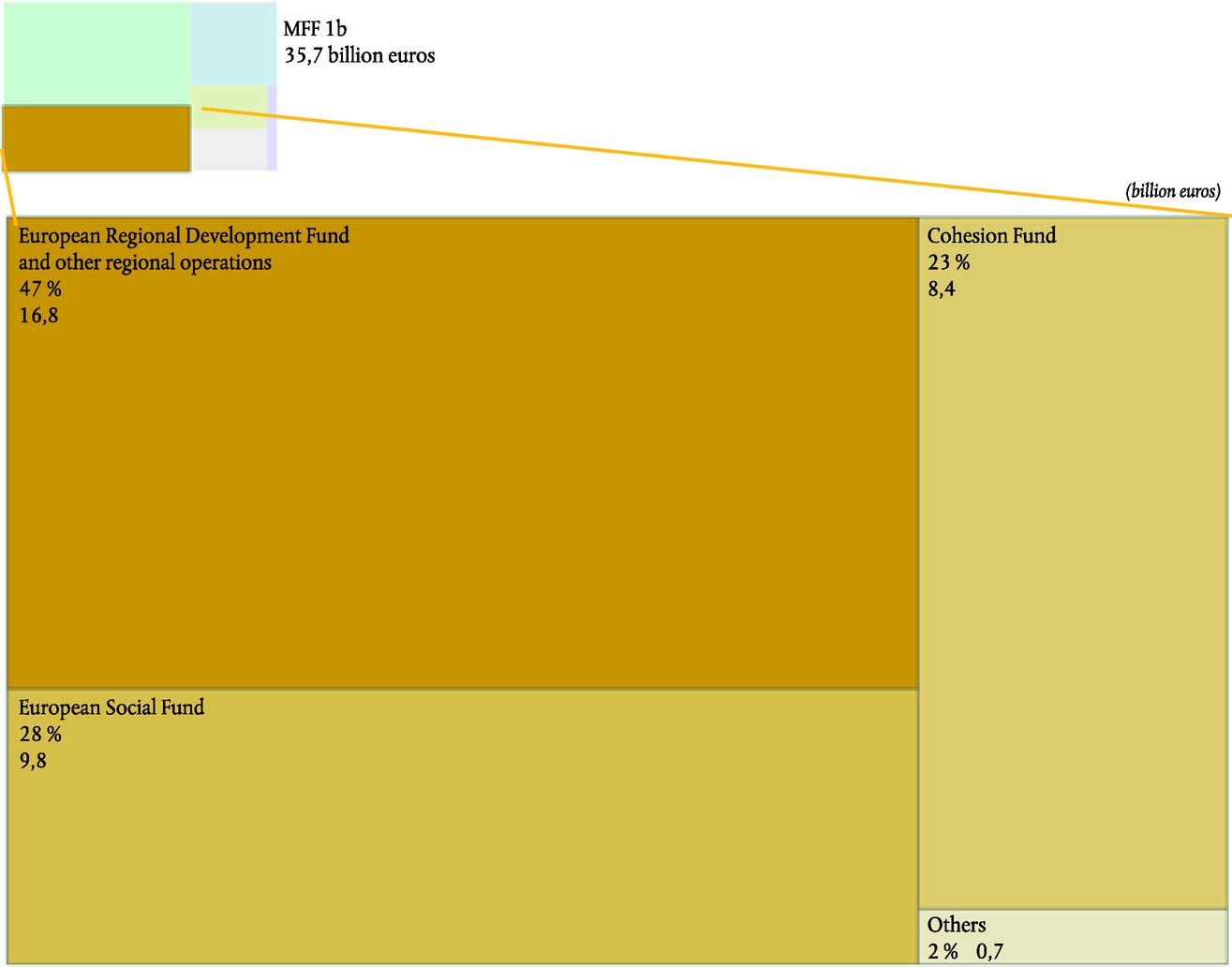

3.6.

|

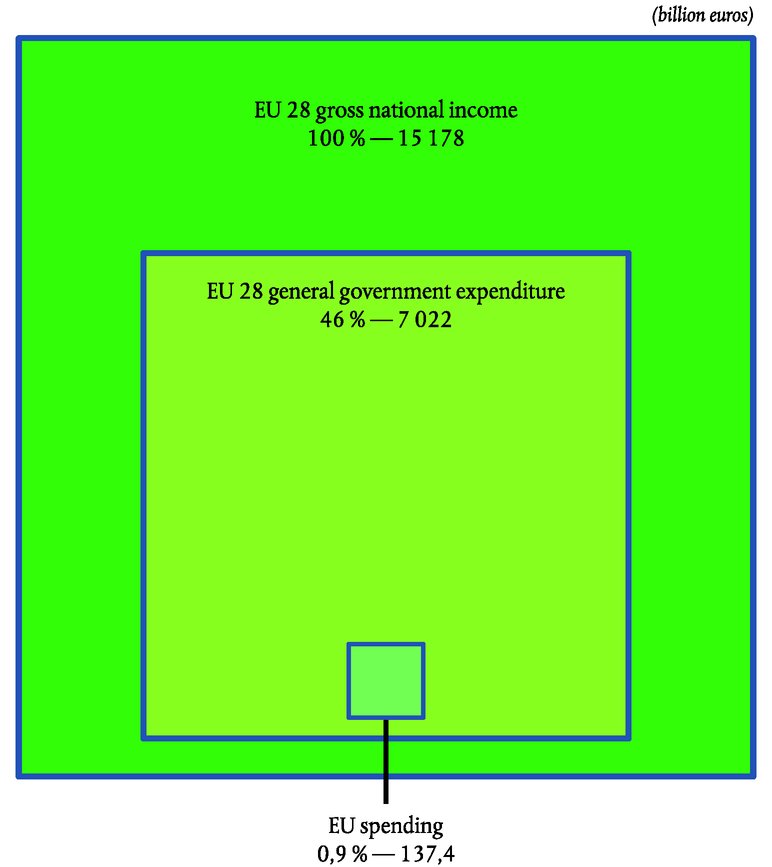

In national budgeting, it is usual to reallocate resources each year, or even more frequently. In the EU context, though, the situation is different. In its mid-term review of the 2014-2020 multiannual financial framework (MFF) (10), the Commission noted that it was essential to strike a balance between medium-term predictability and the flexibility to respond to unforeseen circumstances. In the 2014-2020 multiannual financial framework, about 80 % of the EU budget is pre-allocated; this, according to the Commission, ‘limits the budget’s responsiveness to evolving needs’.

|

|

|

|

THE COURT’S OBSERVATIONS

|

THE COMMISSION’S REPLIES

|

|

3.7.

|

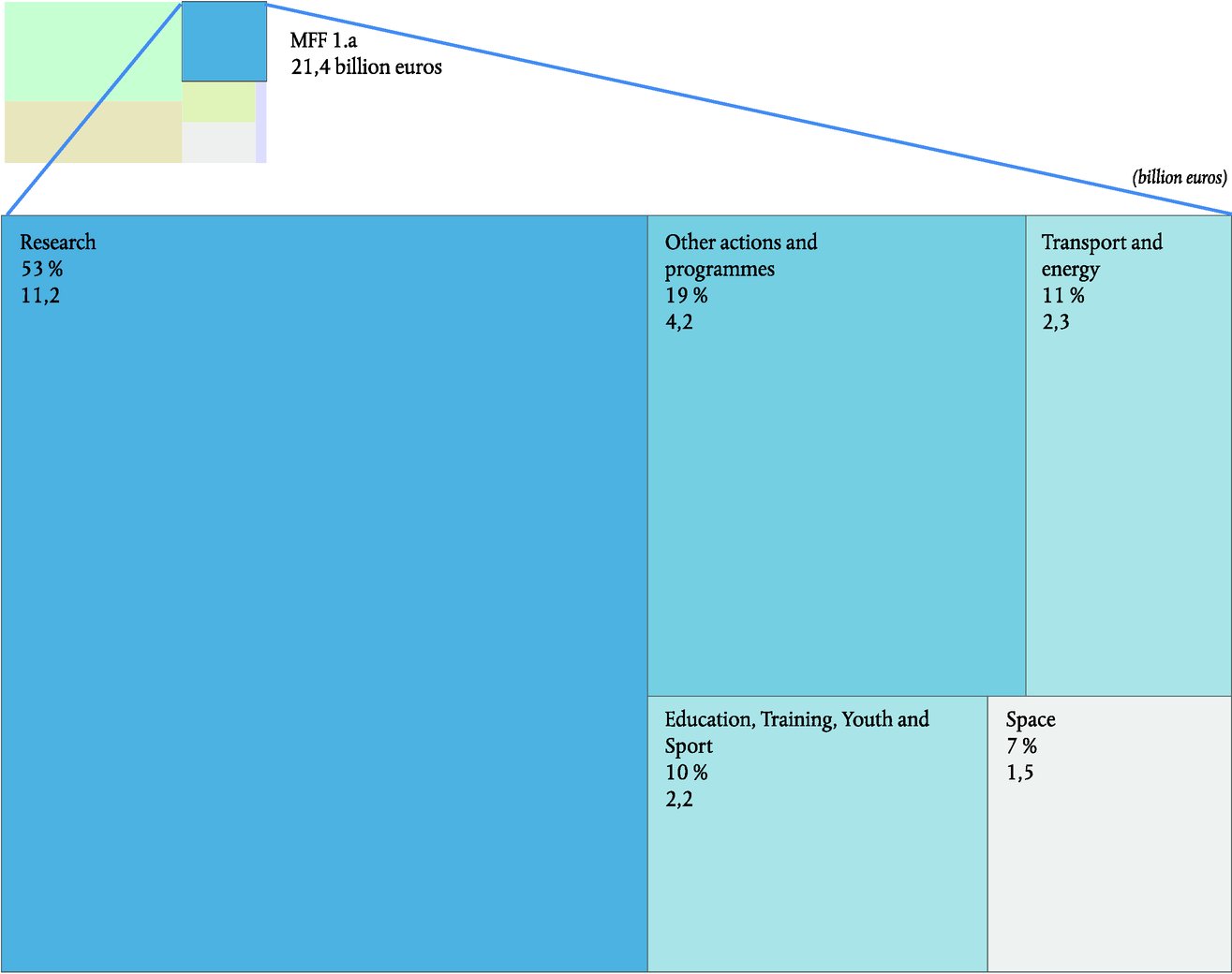

The EU budget is mainly an investment budget. Annual ceilings are set for the various budget headings included in the seven-year multiannual financial framework, and amounts are pre-allocated to Member States. While there already are some performance-linked flexibility mechanisms set out in the relevant sectorial legislation, such as the performance reserve and ex-ante conditionalities, these have limitations (11). Although non-performing activities can be replaced by better ones in the same area and Member State, there is only limited space for adjusting spending priorities between budget headings. The most important ‘window of opportunity’ for allocating funds by taking into account performance information is the drafting and negotiation of a new multiannual financial framework regulation and the accompanying sectoral programmes.

|

|

|

|

3.8.

|

Multiannual financial framework mid-term reviews present another opportunity for taking performance information into account. The last such review (12) resulted in a re-allocation of 12 798 million euros, representing 1,18 % of the total multiannual financial framework commitment appropriations for the 2014-2020 period: a relatively limited proportion. The main driver for these reallocations of funds was to address the refugee crisis and other security threats, as well as investment gaps resulting from the financial and economic crisis, rather than performance.

|

|

|

3.8.

|

A number of factors are taken into account when deciding on budgetary allocations. For example, the reallocation of funds in response to the refugee crisis and security threats was a consequence of major unforeseen geopolitical and societal developments. Performance can only be taken into account insofar as there is reliable and timely information available, which will not always be the case in particular in a crisis situation.

|

|

|

There are parallel strategic frameworks

|

|

|

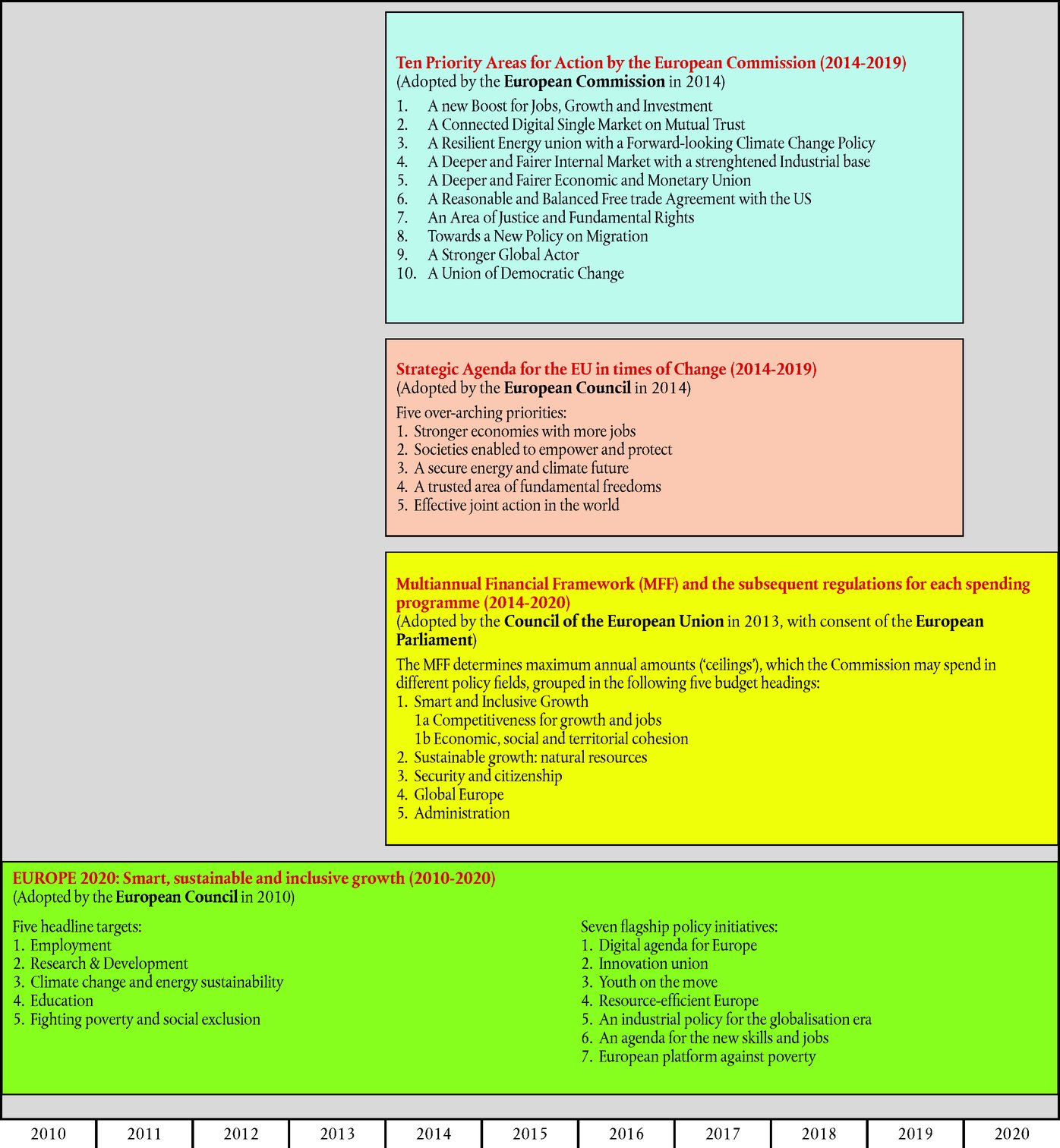

3.9.

|

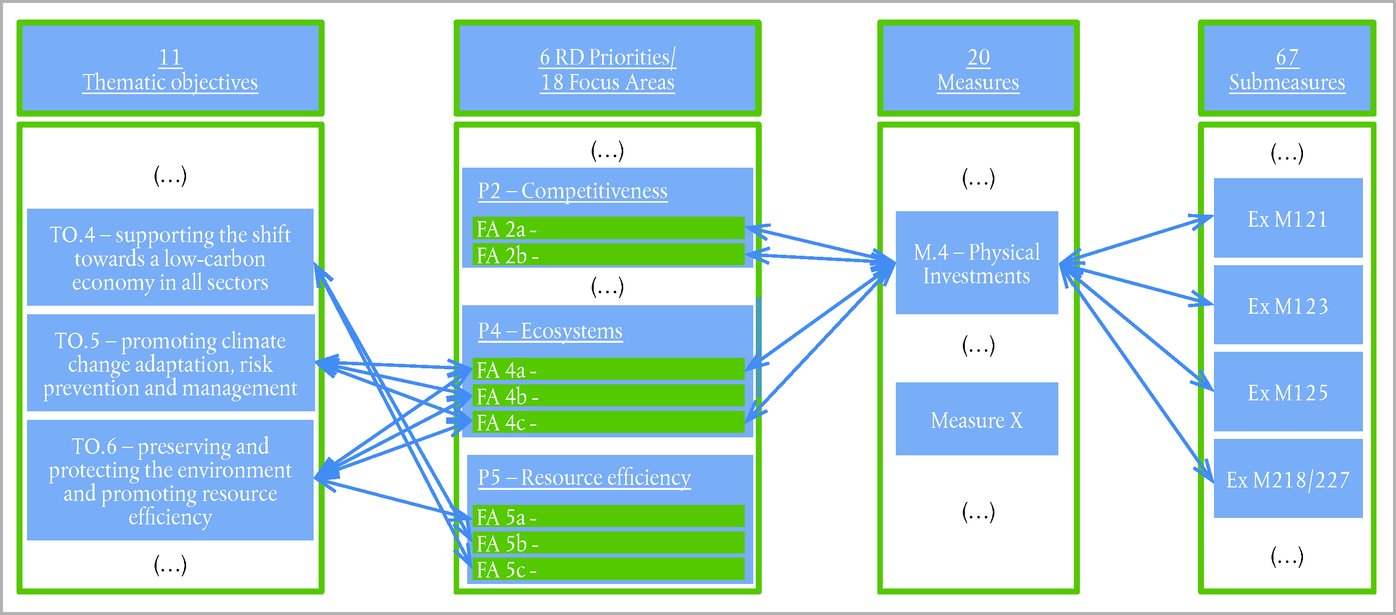

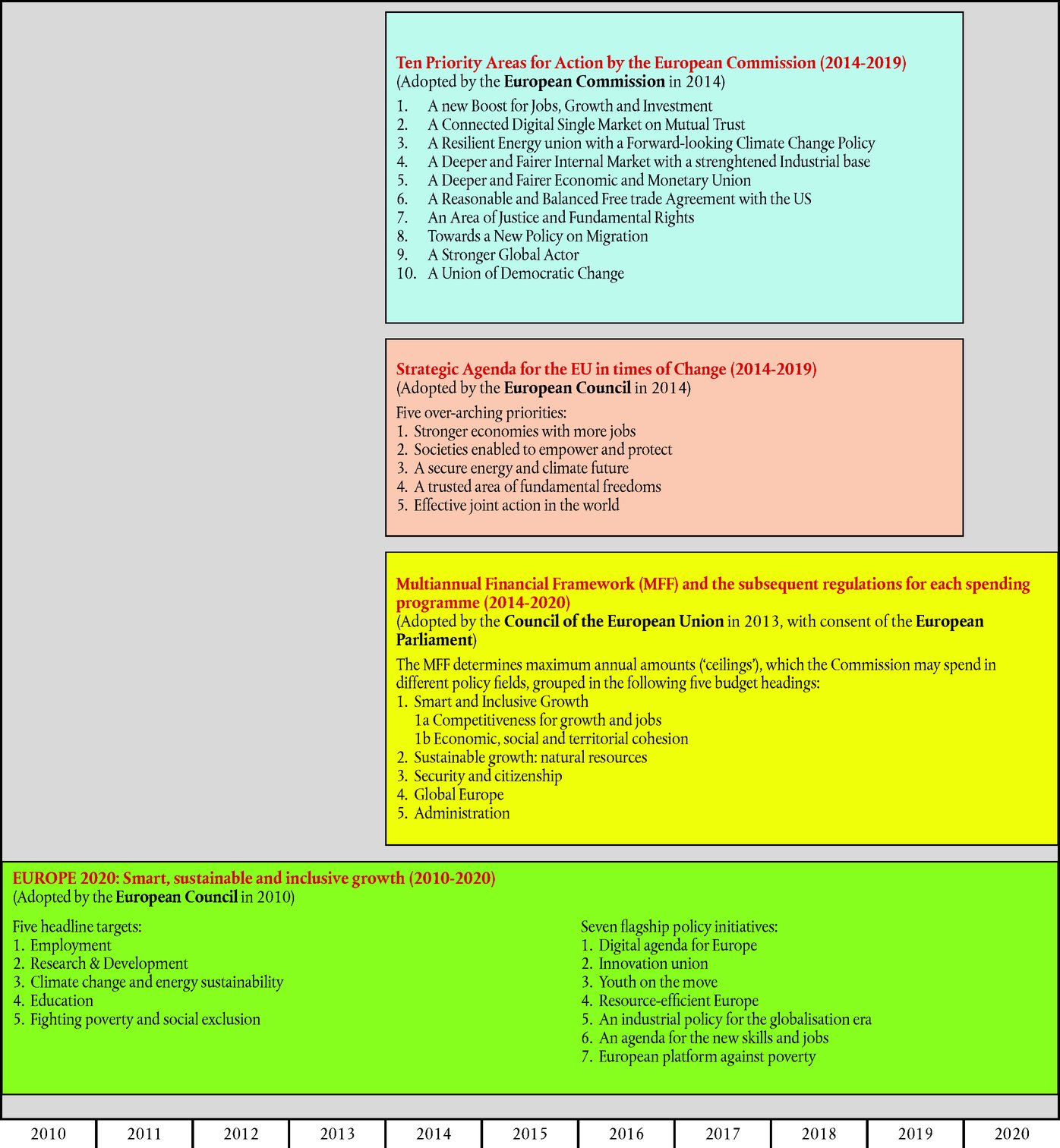

Measuring the EU budget’s and the Commission’s contributions to high-level objectives is complex, because several political strategic frameworks apply in parallel (13) (see

Box 3.1

):

|

|

|

3.9.

|

The Commission considers that the political priorities of the Juncker Commission are fully compatible and consistent both with the Strategic Agenda of the European Council and the Europe 2020 Strategy.

The Multiannual Financial Framework is one of the tools for implementing the Union’s priorities. The current Multiannual Financial Framework was designed to contribute to the Europe 2020 strategy and provides strong support for other emerging priorities (14).

|

|

|

Box 3.1 — Four strategic frameworks for the European Union (applicable in parallel)

Source: ECA.

|

|

THE COURT’S OBSERVATIONS

|

|

|

3.10.

|

In addition, other goals are defined in various sectoral policy documents in accordance with the EU’s competences stemming from the Treaty on the functioning of the EU. The EU is also committed to implementing the Sustainable Development Goals defined by the United Nations. The EU aims to report each year on the progress it has made towards achieving those goals.

|

|

|

|

3.11.

|

We examined how the DGs dealt with the co-existence of various strategies. Two approaches were prevalent.

|

(i)

|

Some DGs had fulfilled their various strategic reporting commitments by developing IT tools that could store, monitor, consolidate and report data in various configurations (see also paragraph 3.16).

|

|

(ii)

|

Some DGs had adjusted their performance frameworks to suit the variety of strategic needs. DG EAC, for example, sets its performance framework at three levels.

|

(a)

|

At EU level, DG EAC monitors the relevant objectives and indicators of the Europe 2020 strategy and the Education & Training 2020 (ET2020) strategic framework based on data from Eurostat, the OECD and other sources, in cooperation with the Member States. It carries out an annual review to ensure progress is being made in the right direction (15).

|

|

(b)

|

At the level of the Commission, DG EAC contributes more directly through its programme and policy work to two of the ten objectives of the Investment Plan for Europe. Progress is monitored, the annual activity report and the programme statements.

|

|

(c)

|

At the level of DG EAC itself, reporting and decision-making is centred around seven policy domains, each of which has its own specific objectives. Legislative work in the different domains is monitored in the Commission’s work programme.

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE COURT’S OBSERVATIONS

|

THE COMMISSION’S REPLIES

|

|

3.12.

|

The multiplicity of strategies leads stakeholders to consider them as separate approaches, as for instance shown by the Commission’s evaluation of the EU Youth Strategy (16).

|

|

|

3.12.

|

The evaluation of the EU Youth Strategy concluded that (section 3.2.1) ‘the EU Youth Strategy added a mainstreaming dimension in view of linking the EU youth policy to the European strategies for education, employment and social inclusion’ and that (section 3.2.2) ‘several of the EU Youth Strategy’s priority areas fit well into the Europe 2020 Strategy’s targets’.

|

|

|

3.13.

|

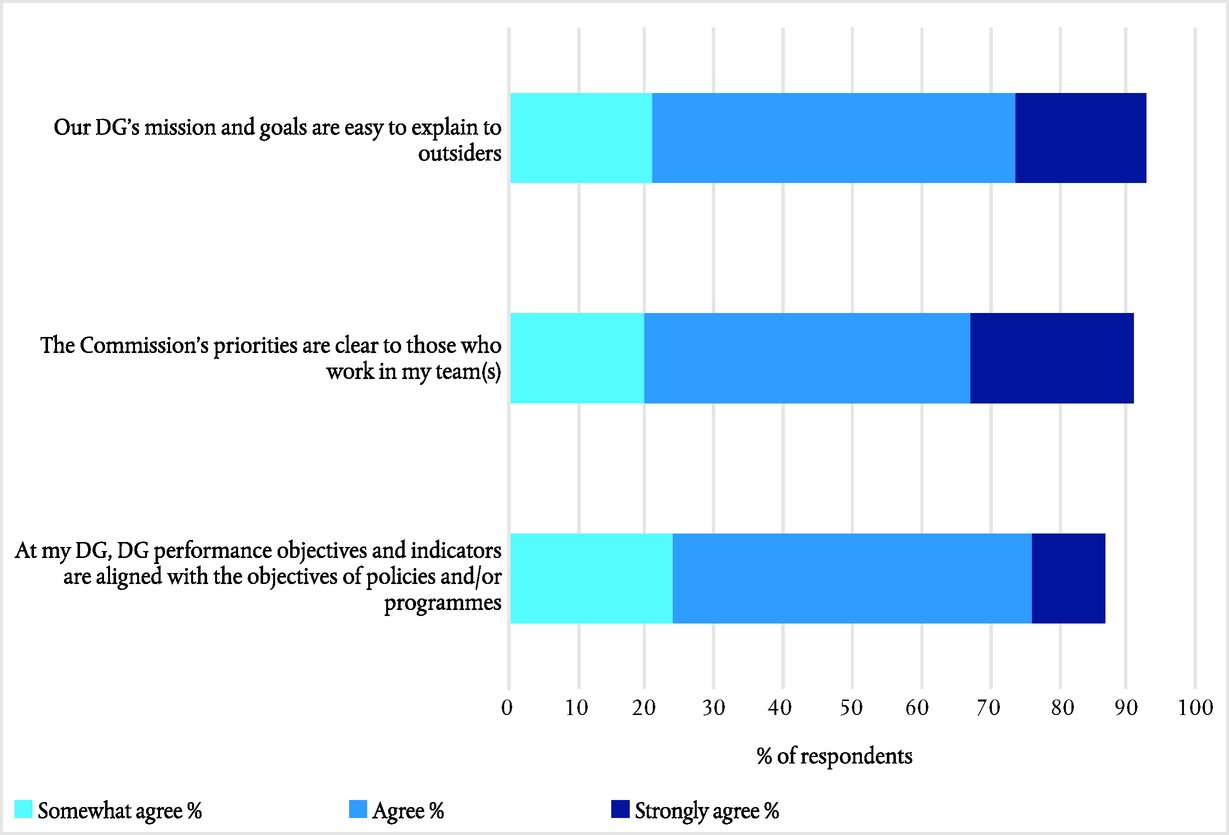

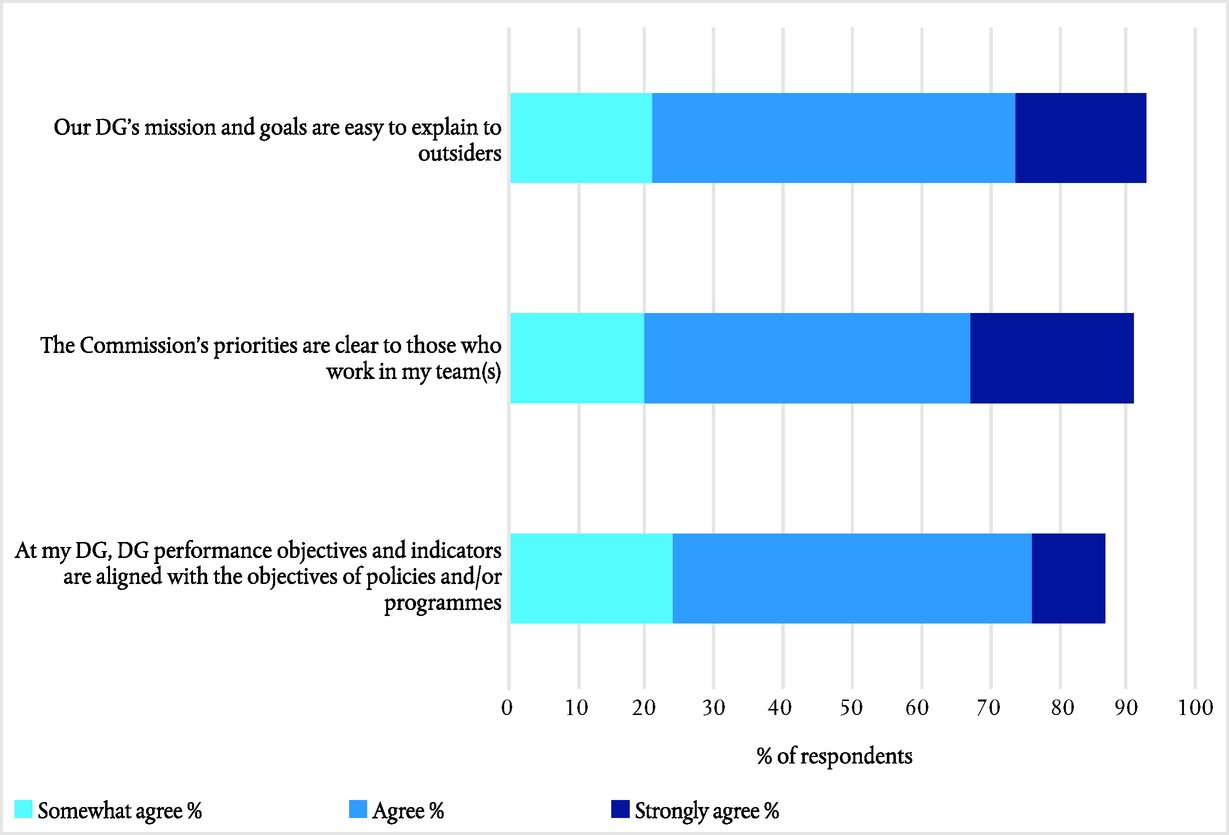

Our survey included questions on ‘goal clarity’. With these questions, we aimed to find out how well Commission managers understood the mission and goals of their DGs and of the Commission in general (see

Box 3.2

). Overall, survey replies were positive and indicated a high level of understanding. However, managers in two of the six DGs we interviewed made reference to the complexity of interactions between the different EU strategic frameworks, and between the goals of these frameworks and those set at the level of the DGs.

|

|

|

|

Box 3.2 — Survey results — Goal clarity

Source: ECA survey.

|

|

THE COURT’S OBSERVATIONS

|

|

|

Section B — The Commission’s performance measurement systems make vast quantities of data available but not always in a timely manner

|

|

|

Vast quantities of performance information are available to managers

|

|

|

3.14.

|

The Commission DGs collect performance information in various formats and from diverse sources, thereby generating a wealth of performance-relevant information. In addition to reporting, the Commission uses performance information to keep track of its ongoing activities, in particular to assess whether the targets of spending programmes have been reached, and as an input for the ‘Better Regulation’ process which supports the preparation of legislative proposals.

|

|

|

|

3.15.

|

The choice of what information to use depends on the type of decision to be made.

Box 3.3

below gives an overview of the main decision-making processes involving the use of performance information.

|

|

|

|

Box 3.3 — The Commission’s main decision-making processes

|

|

Decision type

|

Performance information used in the Commission’s decision-making process

|

|

Spending programmes

|

Proposal for MFF budget for a 7-year period

|

|

—

|

Programme monitoring information (including output, result and impact indicators)

|

|

—

|

Evaluations and impact assessments

|

|

|

Proposal for legal basis for spending programmes during the MFF period

|

|

—

|

Programme monitoring information (including output, result and impact indicators)

|

|

—

|

Evaluations and impact assessments

|

|

|

Proposal for the annual budget

|

|

—

|

Programme monitoring information (including output, result and impact indicators)

|

|

—

|

Evaluations and impact assessments

|

|

|

Implementation of programme budget

|

|

—

|

Project data on individual projects and consolidated into output, result and impact indicators

|

|

—

|

Annual monitoring reports

|

|

—

|

Member State reporting (shared)

|

|

—

|

Reporting from partners (indirect)

|

|

|

Non-spending policy work

|

Proposal for EU legislation

(ordinary legislative procedure)

|

|

—

|

Contextual information (Eurostat and other statistics, expert networks, stakeholder dialogue, country reviews etc.)

|

|

—

|

Studies, evaluations, impact assessments

|

|

|

Policy implementation and monitoring

|

|

—

|

Feedback received from policy experts, academia and other stakeholders

|

|

—

|

Studies, evaluations, Eurobarometer surveys

|

|

|

Source: ECA.

|

|

|

THE COURT’S OBSERVATIONS

|

THE COMMISSION’S REPLIES

|

|

3.16.

|

Several Commission DGs have recently implemented new instruments and processes for using performance data. Often, they have introduced new IT applications which generate tailor-made and up-to-date reports to facilitate decision-making. The development of these new tools is evidence of the Commission’s commitment to progress in better managing performance data (17). The following examples illustrate the range of new developments.

|

|

3.16.

|

|

(i)

|

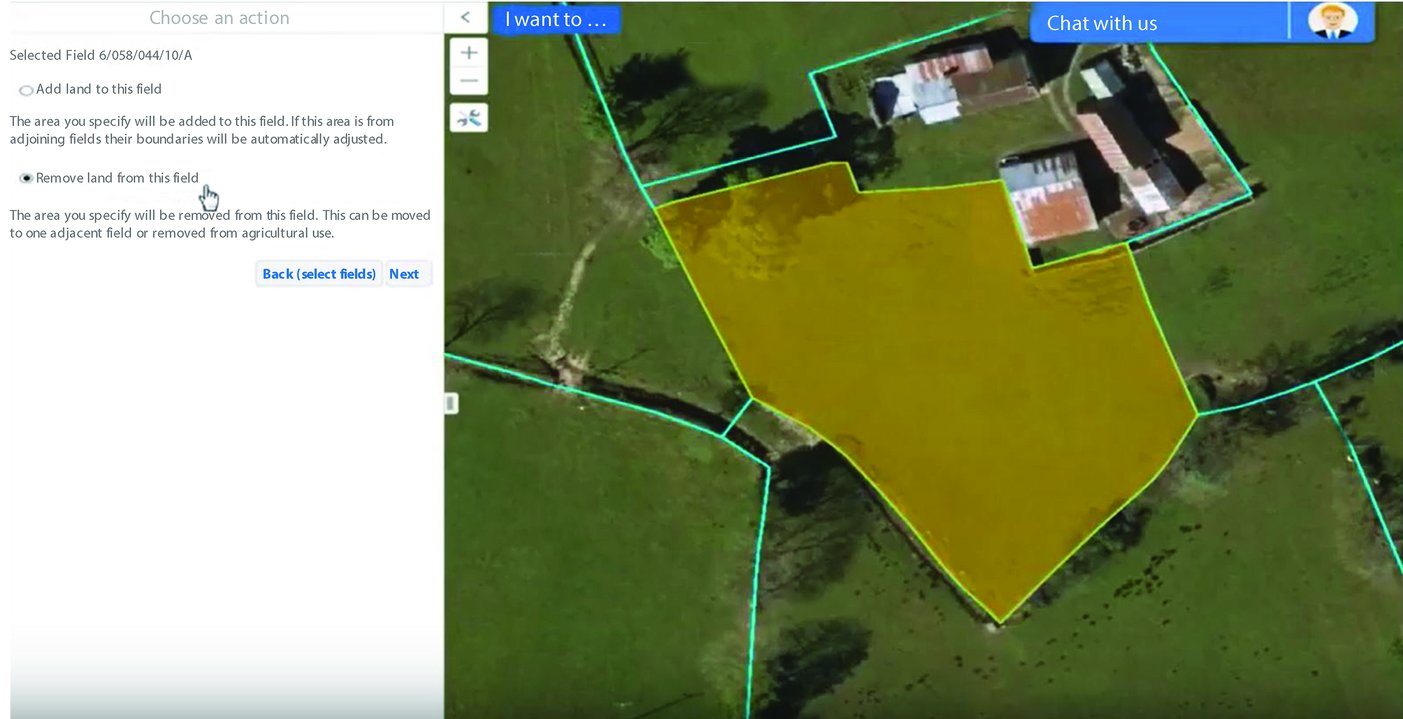

DG AGRI’s new Rural Development Information System 2 is an IT system which assists in managing the workflow of programmes, including programme evaluation. Reports can be generated to compare the implementation of EU programmes in Member States with the EU average.

|

|

|

|

(ii)

|

DG DEVCO is in the process of developing a new IT tool that will include modules for monitoring and reporting results and for supporting action appraisal and financing decision processes. The system should link projects to strategic planning.

|

|

|

|

(iii)

|

DG EAC’s Erasmus+ dashboard is an IT system used by all Erasmus+ national agencies across Europe. It provides real-time performance information from all 57 agencies, including feedback on the results of Erasmus+ via a survey tool which measures participant satisfaction. These features enable DG EAC to obtain rapid feedback on any programme developments and react to them quickly.

|

|

|

(iii)

|

The dashboard also contains real-time performance data on indirectly managed grant procedures, in line with a grant performance management framework defined in 2017 across all EAC programmes.

|

|

|

There is scope for further developing the performance measurement systems

|

|

|

3.17.

|

In last year's annual report (18), we identified areas of good practice in public performance reporting by governments and international organisations around the world. We suggested that the Commission should consider implementing these good practices itself. We recommended that the Commission should improve its performance reporting by making it more streamlined, balanced, user-friendly and accessible. We also recommended that the Commission should assess the quality of the presented information. The Commission reacted to these recommendations by reflecting them in the instructions for its 2017 AAR.

|

|

|

|

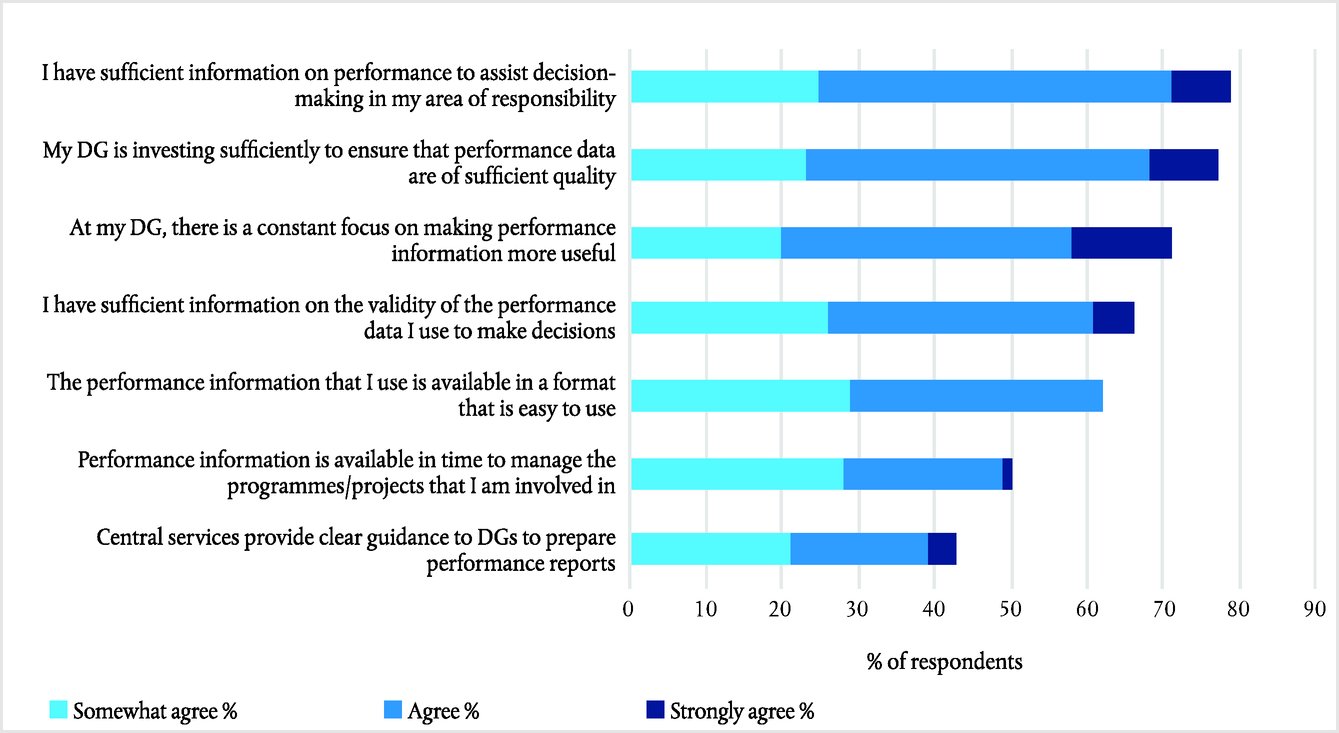

3.18.

|

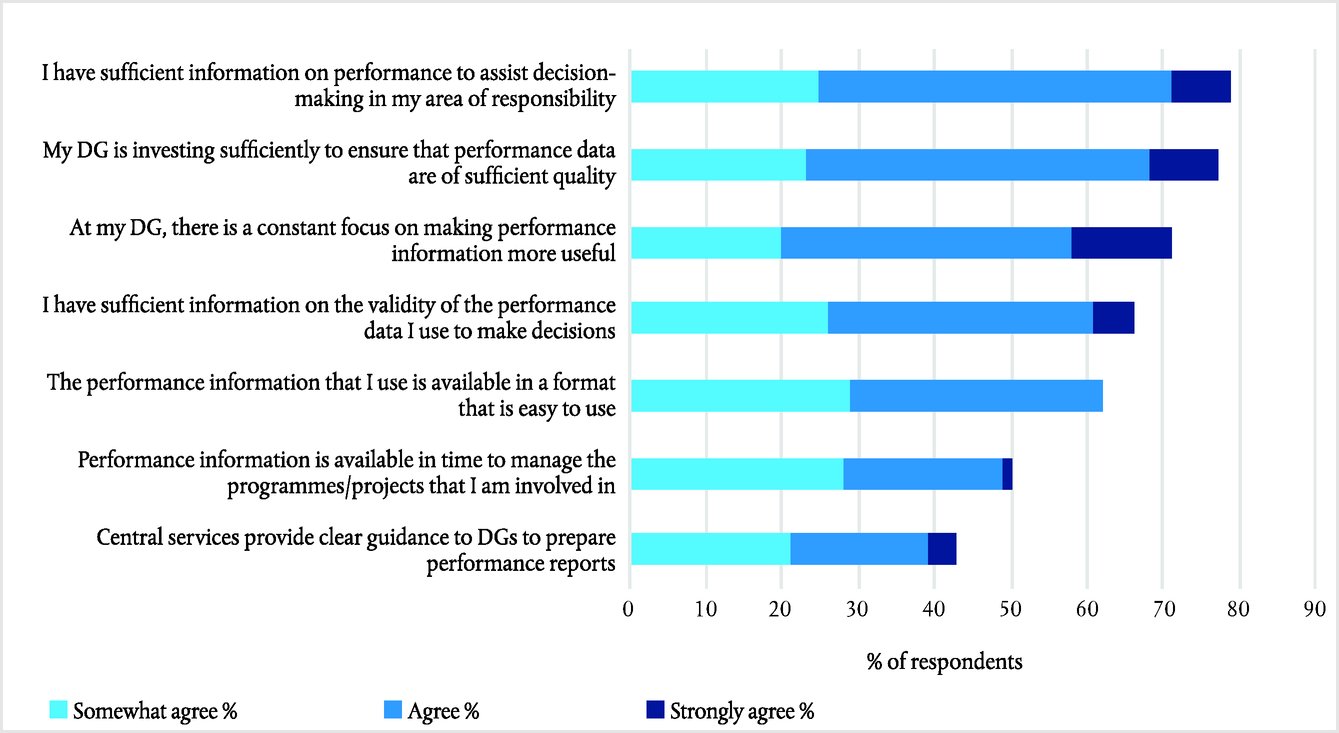

Our survey this year focused on the performance information available to managers (see

Box 3.4

). The survey results indicated that performance measurement systems needed further development. In particular, they confirmed that the timeliness of performance information was an issue (19). The Commission’s central departments have devised extensive instructions, templates, training and exchanges for preparing performance reports (for example, instructions were issued in November 2017 for the 2017 annual activity reports). Nevertheless, the survey results also showed that DGs wished to receive additional guidance on preparing reports. We also noted that the respondents who replied more negatively to these questions typically used performance information less frequently.

|

|

|

3.18.

|

The Commission recognises that reliable and comprehensive information on the results and impacts of financial programmes and other policy activities only becomes available with significant time lags.

To the extent possible, the Commission takes account of this in its planning. For example, all Commission Directorates-General plan their evaluation activities with a (minimum) five-year rolling programme, to provide timely performance information for their reporting. The plan needs to be annually updated.

Regarding the guidance on preparing reports, the central services of the Commission provide extensive guidance on all the preparation of all major performance reports produced by the DGs, taking into account the progress made over the years. This includes the Annual Activity Reports for Commission services and the Programme Statements accompanying the draft budget. Guidance is also provided for evaluations in the Better Regulation Guidelines and toolbox. Other types of reviews are also described. Guidance is also provided centrally to design appropriate performance reporting systems, with the aim of collecting data efficiently for monitoring programme implementation and results, effectively, and in a timely manner. Formal guidance is complemented with training sessions and exchanges of best practices between services.

|

|

|

Box 3.4 — Survey results — Performance information framework

Source: ECA survey.

|

|

THE COURT’S OBSERVATIONS

|

|

|

Section C — The Commission uses performance information to manage programmes and policies although appropriate action is not always taken when targets are not met

|

|

|

The Commission uses performance information at its disposal to manage its activities

|

|

|

3.19.

|

56 % of the respondents to our survey said that they used performance information for decision-making either often or very often. The four most frequent uses of performance information were for developing strategies, improving decisions, assessing whether targets were met, and taking corrective action where necessary (20).

|

|

|

|

THE COURT’S OBSERVATIONS

|

THE COMMISSION’S REPLIES

|

|

3.20.

|

It is difficult for managers to use performance information to assess how programmes and policies contribute to high-level objectives. Also, managers do not have sole responsibility for performance. This is because the co-legislators and other stakeholders, Member States in particular, play a major role in achieving results and making an impact. In previous years, we have observed (21) that many programme and policy objectives are taken directly from policy or legislative documents, and are thus set at too high a level to be useful as management instruments. We also issued recommendations (22) that the Commission should tackle this. The Commission acknowledged that it was difficult to create links between the abundant information available on projects at the operational level and the high-level policies and decision-making at political level.

|

|

|

3.20.

|

The Commission considers it important to draw a clear distinction between the internal performance framework for the Commission services, and the performance frameworks in financial programmes.

Objectives and indicators contained in financial programmes are the product of the legislative process. They relate to the performance of programmes, not of the Commission services. The Commission has made proposals to strengthen the performance frameworks in financial programmes as part of the proposals for the future Multiannual Financial Framework.

Concerning Horizon 2020, see the reply of the Commission to the Recommendation 1 in the 2015 ECA’s annual report.

Concerning the Commission’s ability to monitor and report against Europe 2020, see the reply of the Commission to paragraph 3.97 in the 2014 ECA annual report.

The link between objectives and related indicators in a wider policy perspective is presented in the Programme Statements.

|

|

|

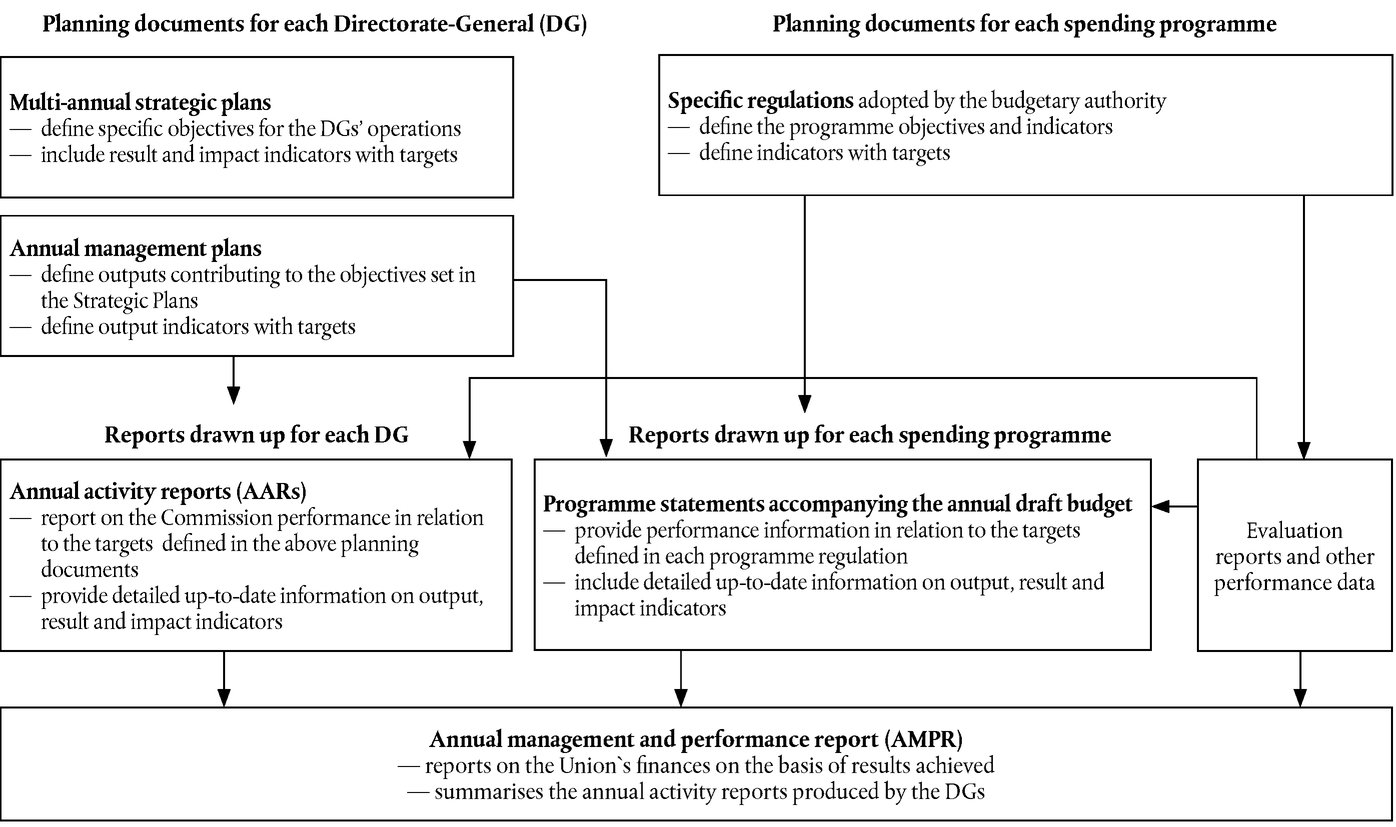

3.21.

|

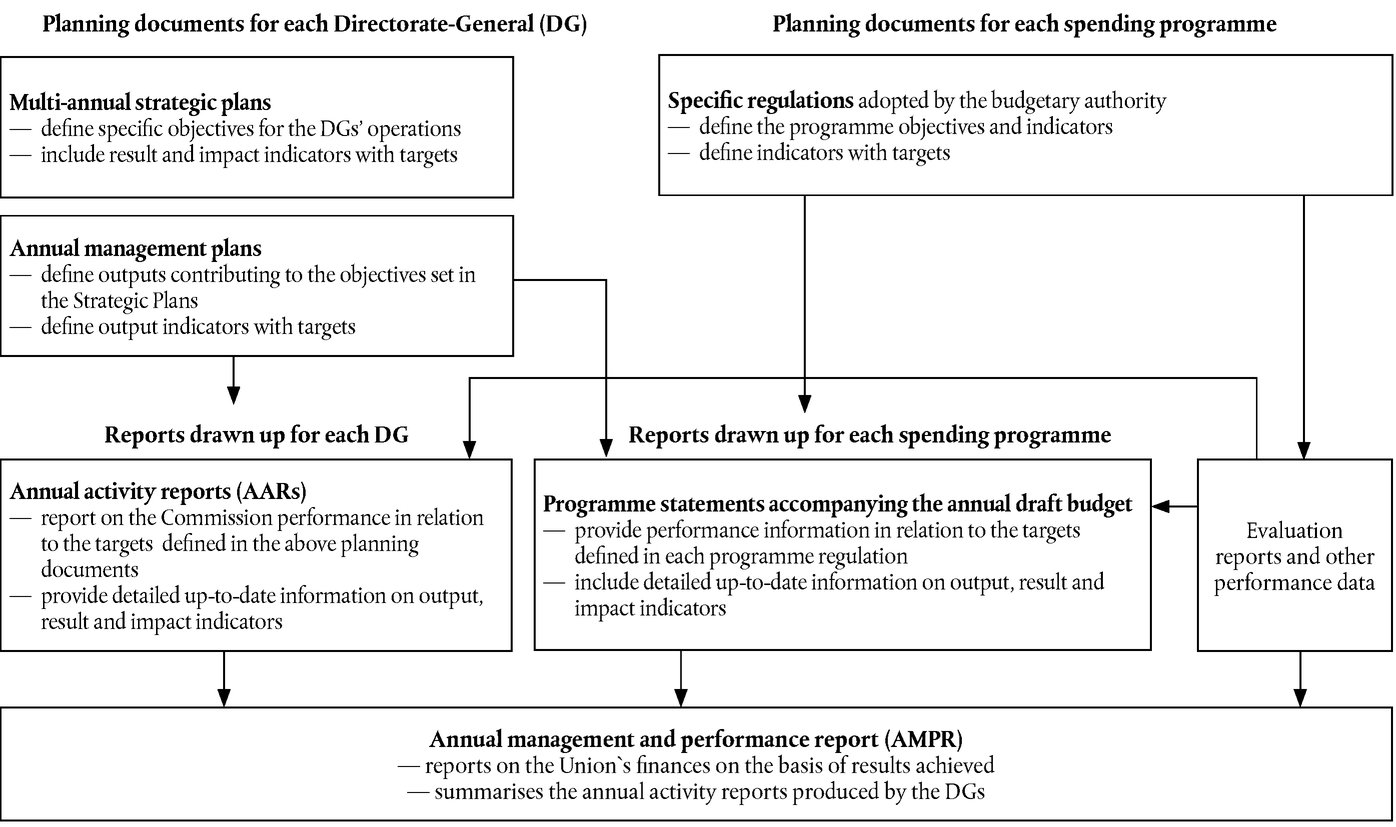

Every year, the Commission uses three core reporting tools — the annual activity reports (AARs), programme statements (PSs), and the annual management and performance report (AMPR) — to give an account of its operational performance and the performance of EU programmes and policies. As illustrated in

Box 3.5

below, a number of planning documents are the basis for the reporting in these three core reports (23).

|

|

|

3.21.

|

The Commission notes that the three reports mentioned here, which are produced in accordance with the relevant legal obligations, are only a subset of the Commission’s extensive reporting on the performance of EU policies and the delivery of the political priorities. The Annual Management and Performance Report and the Programme Statements relate primarily to the performance and management of the EU budget.

|

|

|

Box 3.5 – Core performance reports produced by the Commission and its DGs

(24)

Source: ECA.

|

|

THE COURT’S OBSERVATIONS

|

THE COMMISSION’S REPLIES

|

|

3.22.

|

The three reports cover the EU's entire budget, and all of its policy activities.

Box 3.6

gives a summary of the reports’ intended audience and use.

|

|

|

3.22.

|

See the Commission reply to paragraph 3.23.

|

|

|

Box 3.6 — Intended audience and use of the core performance reports

|

|

Who is the intended audience?

|

How is the report to be used?

|

|

PS

|

The document is submitted to the Budgetary Authority (European Parliament and Council) as a supplement to the draft general budget

|

The role of the programme statements is to substantiate budget allocations requests for spending programmes by giving an account of the programmes' performance, EU added value and implementation rate (present and future).

|

|

AAR

|

College of Commissioners

|

The AAR is a management report of the Directors-General of the DGs to the College of Commissioners. It is ‘the main instrument of management accountability within the Commission’ (see 2017 AAR Instructions).

|

|

AMPR

|

The report is submitted to the European Parliament and to the Council, in accordance with Article 318 of the TFEU and Article 66(9) of the Financial Regulation

|

The AMPR (61) is an accountability tool in the discharge procedure with the Discharge Authority: by adopting it, the College of Commissioners takes overall political responsibility for the management of the EU budget.

|

|

Source: ECA.

|

|

|

THE COURT’S OBSERVATIONS

|

THE COMMISSION’S REPLIES

|

|

3.23.

|

Core performance reports are intended more as reporting tools than as instruments for Commission DGs to manage their own performance, or the performance of the Commission as a whole. This is because the reports are not detailed or comprehensive enough; they are only drawn up once a year; and they are mainly intended for readers external to the DG.

|

|

|

3.23.

|

The Annual Management and Performance Report for the EU budget is part of the Commission’s contribution to the annual budgetary discharge process. It takes into account all relevant information and not only yearly results, for instance mid-term evaluations.

The Annual Activity Report is a management report of the Directors-General and Heads of Services to the College of Commissioners. It is the main instrument of management accountability within the Commission and is detailed and comprehensive. It includes reporting on all indicators chosen by the Commission services in their strategic plans for the 2016-2020 period, as key for measuring the performance of the Commission services and their contribution to the political priorities of the Juncker Commission.

The Annual Activity Report is therefore intended both for an external audience and as a source of management information for Commission managers. The Commission also notes that many key indicators are updated and reported more regularly, for example those relating to the Europe 2020 headline targets. Commission services are encouraged to monitor progress towards their objectives regularly, including for example in the context of mid-year reviews of their management plans.

|

|

|

3.24.

|

There are, however, some instances where core performance reports (and particularly annual activity reports) have a use for managing performance.

|

(i)

|

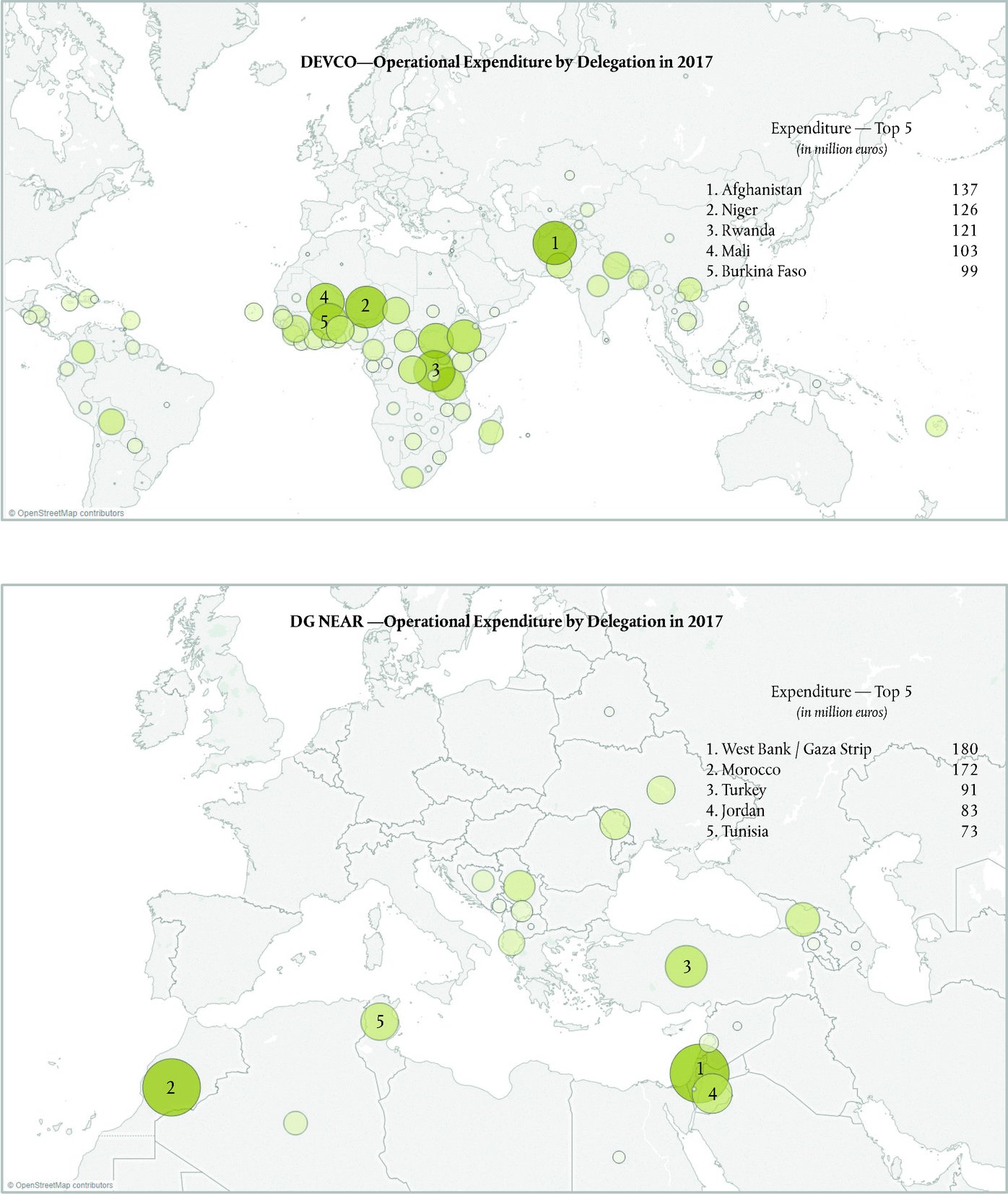

DG DEVCO takes advantage of the public nature of the annual activity report to bring about organisational changes. It reports comparative information on the performance of delegations in partner countries (25) to motivate those delegations to perform better.

|

|

(ii)

|

Although the declared purpose of the annual activity report is to provide accountability, DG CNECT and DG EMPL have also used it as a tool allowing senior management to monitor work programme delivery (26). DG EMPL regards the preparation of the AAR as an opportunity to check whether everything has gone according to plan and if not, to identify reasons and discuss remedies.

|

|

|

|

3.24.

|

See the Commission reply to paragraph 3.23.

|

|

|

3.25.

|

The annual activity reports are publicly accessible documents, but the Commission has not assessed how successfully they target citizens. However, the number of individuals visiting the Europa website (27) suggests that citizen interest is low.

|

|

|

3.25.

|

See the Commission reply to paragraph 3.23.

|

|

|

Corrective action is not always taken when targets are not met

|

|

|

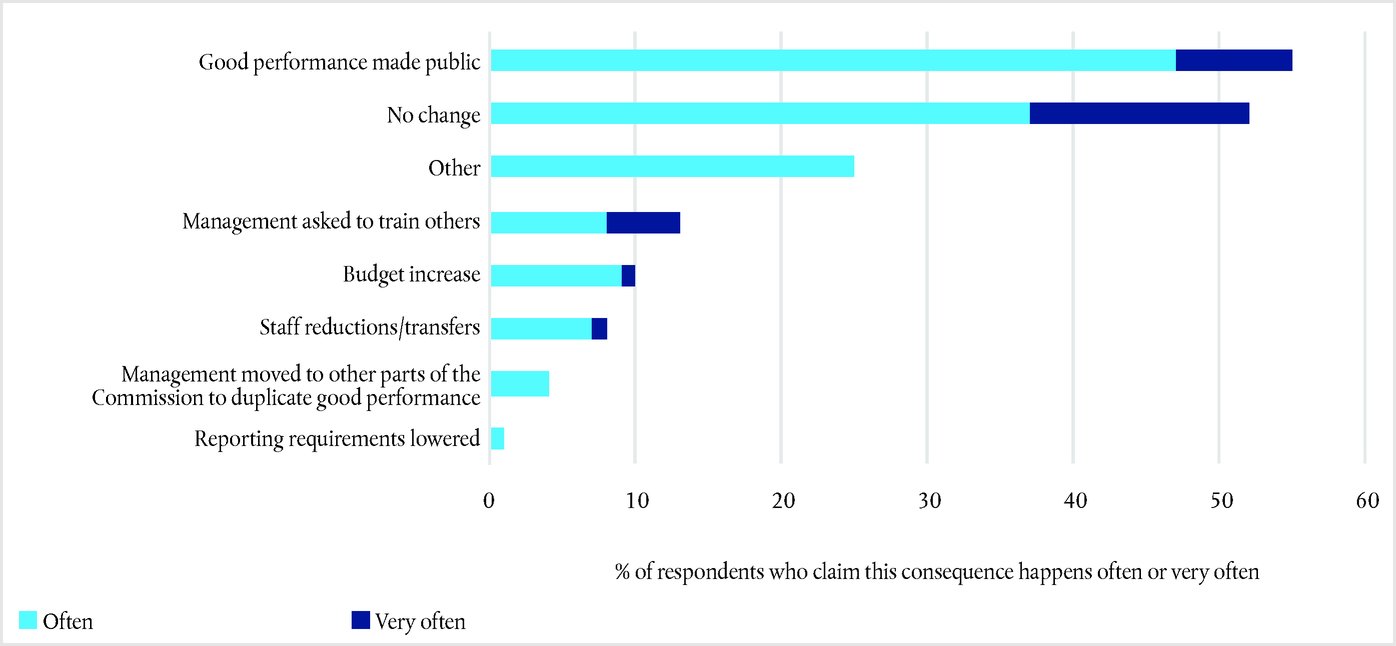

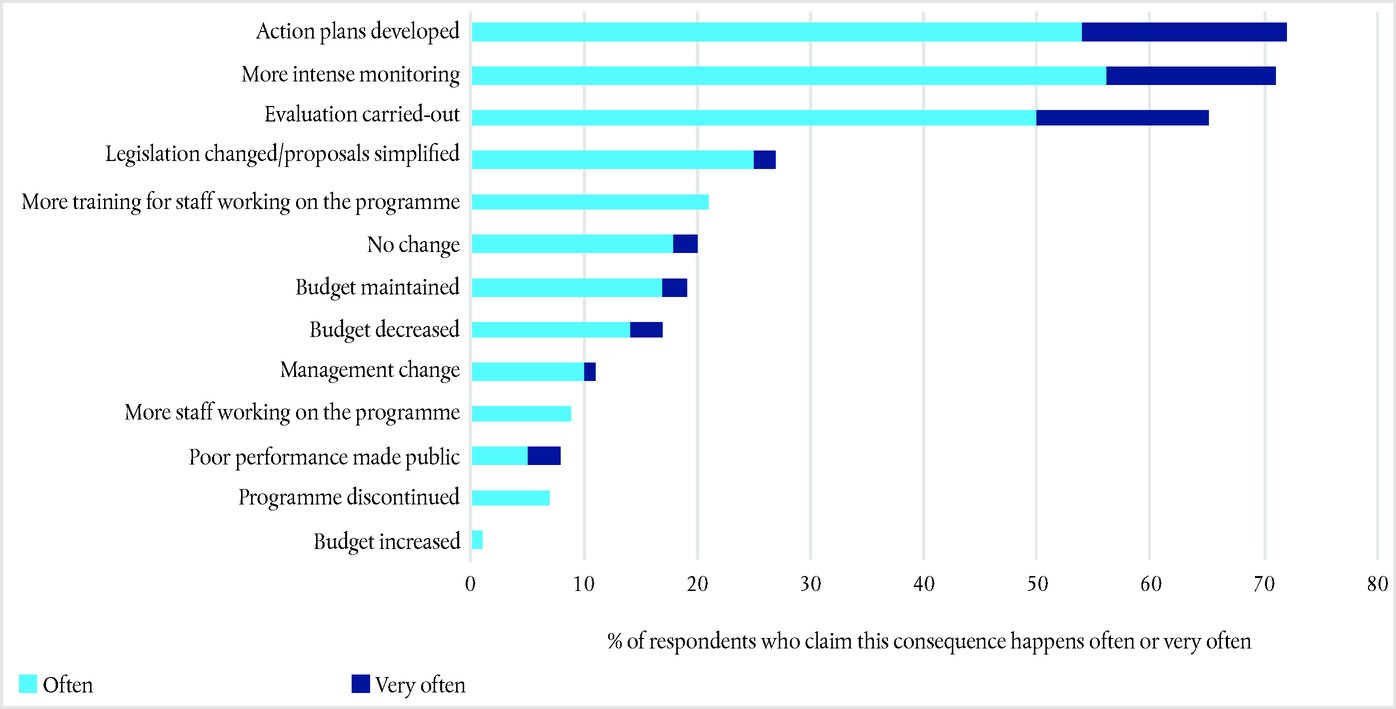

3.26.

|

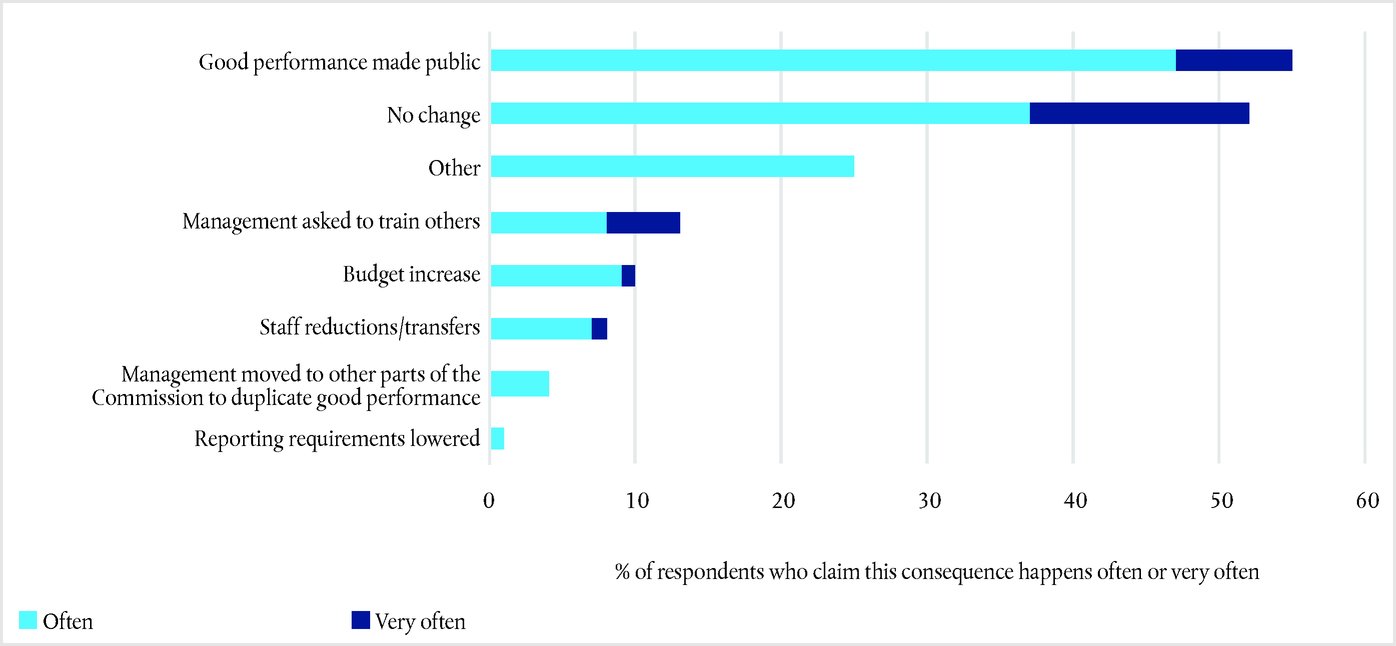

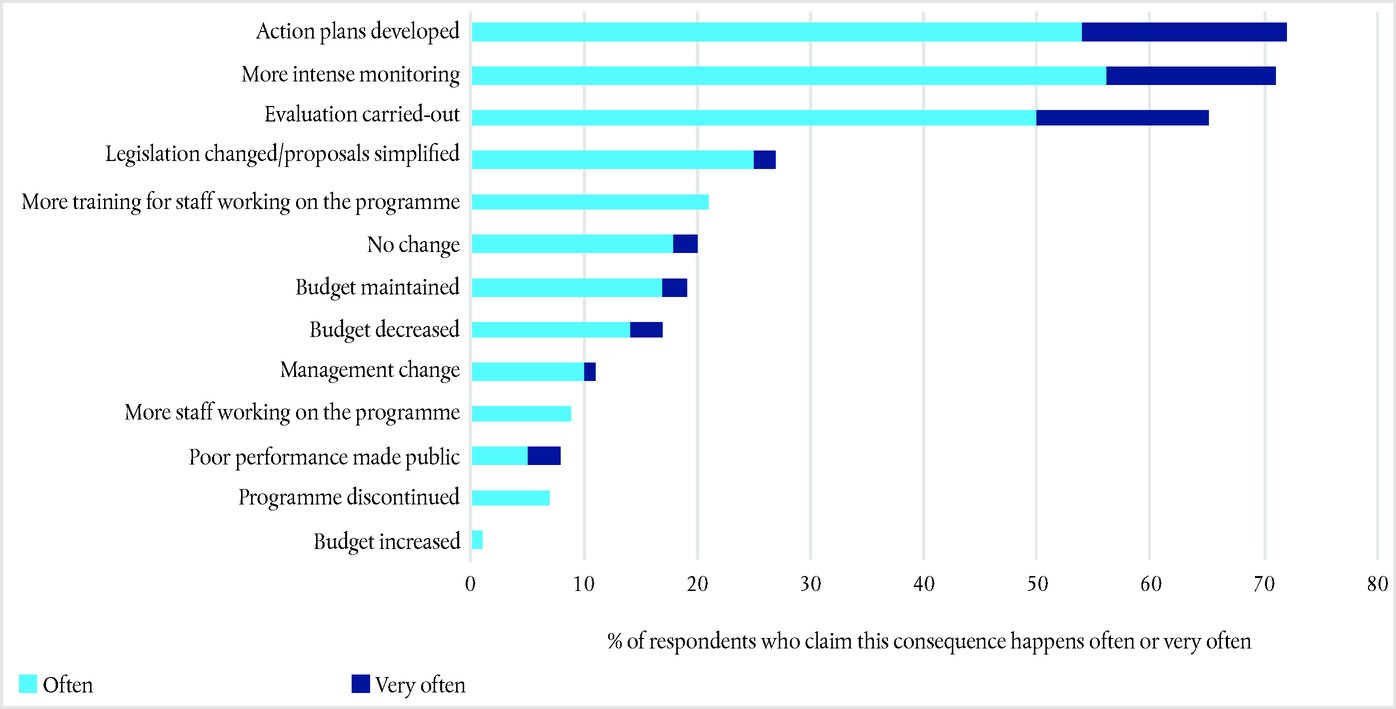

One of the main purposes of using performance information is to measure progress towards meeting targets in order to take corrective action and, ultimately, to achieve results. Knowing that poor performance will have consequences should be a motivation for managers to use performance information. Our survey of managers included a question about what happens, in the respondents' experience, if performance targets, in relation to spending programmes or policies, are met (see

Box 3.7

) or not met (see

Box 3.8

). The survey results indicate that poor performance does not lead to corrective action: in all cases: one fifth of respondents stated that no changes were made when targets were not met. The development of action plans is the most frequent type of decision taken. Next most frequent is further analysis, either in the form of enhanced monitoring or of an additional evaluation. However, such measures do not in themselves correct the identified issues. We observed that not meeting a target was more likely to have consequences in DGs where performance information was used frequently.

|

|

|

3.26.

|

The purpose of using performance information is to monitor performance and to measure the distance between the intended target and the reality and make the necessary adjustments. This would typically be based on a broader assessment of the underlying reasons for why performance has deviated from the target.

As the ECA points out, more than 70 % of respondents indicated that if targets are not met, action plans are developed and more intense monitoring is carried out and more than 60 % of respondents replied that evaluation is carried out if targets are not met.

The Commission also notes that in relation to the management of the EU budget, the Commission faces a number of constraints flowing from the Multiannual Financial Framework and the decisions taken by the budgetary authority on the annual budget.

|

|

|

Box 3.7 — What happens if targets are met or exceeded?

Source: ECA survey.

|

|

Box 3.8 — What happens if targets are not met?

Source: ECA survey.

|

|

THE COURT’S OBSERVATIONS

|

THE COMMISSION’S REPLIES

|

|

Section D — The Commission does not generally explain the use of performance information in its performance reports

|

|

|

3.27.

|

In the interests of transparency and accountability, stakeholders must be able to see in the core performance reports how the Commission uses the performance information available to it (28). In its performance reports, the Commission aims to present a coherent ‘performance story’ (29) on progress made towards achieving results. These stories are more credible if they are based on substantive evidence. They need to explain not only what decisions were made, but also how those decisions reflected available performance information.

|

|

|

3.27.

|

The Commission agrees that reporting on performance must be based on substantive evidence and includes this evidence in its performance reports.

|

|

|

3.28.

|

The Commission’s central departments provide instructions to the DGs for preparing strategic plans, management plans and annual activity reports. While the instructions require the DGs to present performance information when reporting on their activities, DGs are not required to explain how the information was used to improve those activities.

|

|

|

3.28.

|

By contributing to multi-annual objectives with multi-annual targets set in the strategic plans, the information presented in the Annual Activity Reports represent a stage of monitoring, which is then used as a basis for presenting outputs for the year ahead in the management plans, contributing from that stage onwards to the achievement of the specific objectives.

|

|

|

3.29.

|

DGs mention that they use performance information in their reports but without providing further explanations.

|

|

3.29.

|

|

(i)

|

DG AGRI's performance reports (30) describe in general principles how performance information is used to support decision-making (31). Nonetheless, the reports give few specific examples to illustrate how this works in practice.

|

|

|

(i)

|

The 2016 Annual Activity Report of DG AGRI includes several concrete cases that illustrate how performance information is used to support decision making.

In its 2016 AAR DG AGRI specifies that the first key performance indicator of the CAP is agriculture factor income (see page 15). It further spells out the price pressure in the dairy sector and the two assistance packages adopted in response (see pages 21-22).

The same AAR displays on page 25-26 the broadband gap of rural areas and the response taken by setting up Broadband Competence Offices.

With regard to the implementation of greening, DG AGRI carried out a review of how the system had been applied in its first year. This review identified weaknesses that held the system back from achieving its full potential. DG AGRI proposed improvements to the relevant regulation (see pages 32-33 of the 2016 AAR).

|

|

|

(ii)

|

In its 2016 annual activity report, DG CNECT stated that the preparation of the 2016-2020 eGovernment Action Plan ‘has greatly benefited from the evaluation results of the previous Action Plan 2011-15’ (32). No clear explanation is given of how these results affected the new action plan.

|

|

|

(ii)

|

The Annual Activity Report provides a summary of the year’s activities. It would not be appropriate to describe in detail how individual policy decisions have been developed in this report. Services are encouraged to provide links to where more detailed information can be found — in this case in the relevant evaluation.

|

|

|

3.30.

|

The Commission’s annual report on spending programmes (33) includes a section on ‘programme updates’, which has a sub-section on ‘forthcoming implementation’ (34). The plans contained in this section occasionally include general statements about performance as justification. But there is no explanation of how specific feedback on the existing situation was used in drawing up the plans. For example, the planning for the future implementation of Horizon 2020 is called an ‘evidence-based process

(35)’ because it ‘included extensive consultation with stakeholders’. However, no details are given about any changes made as a result of the consultation.

|

|

|

3.30.

|

The section on forthcoming implementation is intended to provide a view on future activities to be implemented and their expected outputs/results.

It is meant to provide a picture on expected relevant developments and is not a planning instrument in itself.

|

|

|

3.31.

|

We however noted some good practices in our review of performance reports. For example, DG EAC has made it an explicit part of its strategy to use performance information for policy-making and for formulating investment strategies (36). In its 2016-2020 strategic plan, DG EAC highlights the link between indicators and evaluation results to back up its policy strategy and the amount of EU funding which it plans to deploy until 2020 (37). When describing the evaluations it plans to perform, DG EAC also outlines how those evaluations will be used for four out of eight planned evaluations in the 2016-2020 Strategic Plan.

|

|

|

|

Section E — Further progress is expected from a continued development in performance culture

|

|

|

3.32.

|

The Commission is pursuing opportunities to become more performance-driven.

|

|

3.32.

|

|

(i)

|

It proposed a revised Financial Regulation setting the ground for further simplification, and allowing payments to depend more directly on results (38).

|

|

|

|

(ii)

|

It carried out a comprehensive spending review for the first time, taking into account EU added value (39).

|

|

|

|

(iii)

|

The Commission has recognised that there are too many performance indicators (40), and that some of them are not meaningful. It has therefore begun reviewing its performance indicators. Result indicators in particular are being reviewed to ensure that they measure results that are within DGs' control.

|

|

|

(iii)

|

Please see the Commission reply to paragraph 3.20. The Commission conducted a comprehensive review of the objectives and indicators used by Commission services as part of the reform of the strategic and management plans.

|

|

|

(iv)

|

Some DGs, such as DEVCO, are attempting to move from result reporting for completed projects into such reporting for on-going projects.

|

|

|

|

(v)

|

The Commission and the budgetary authority will potentially benefit from the ‘Budget Focused On Results’ initiative.

|

|

|

|

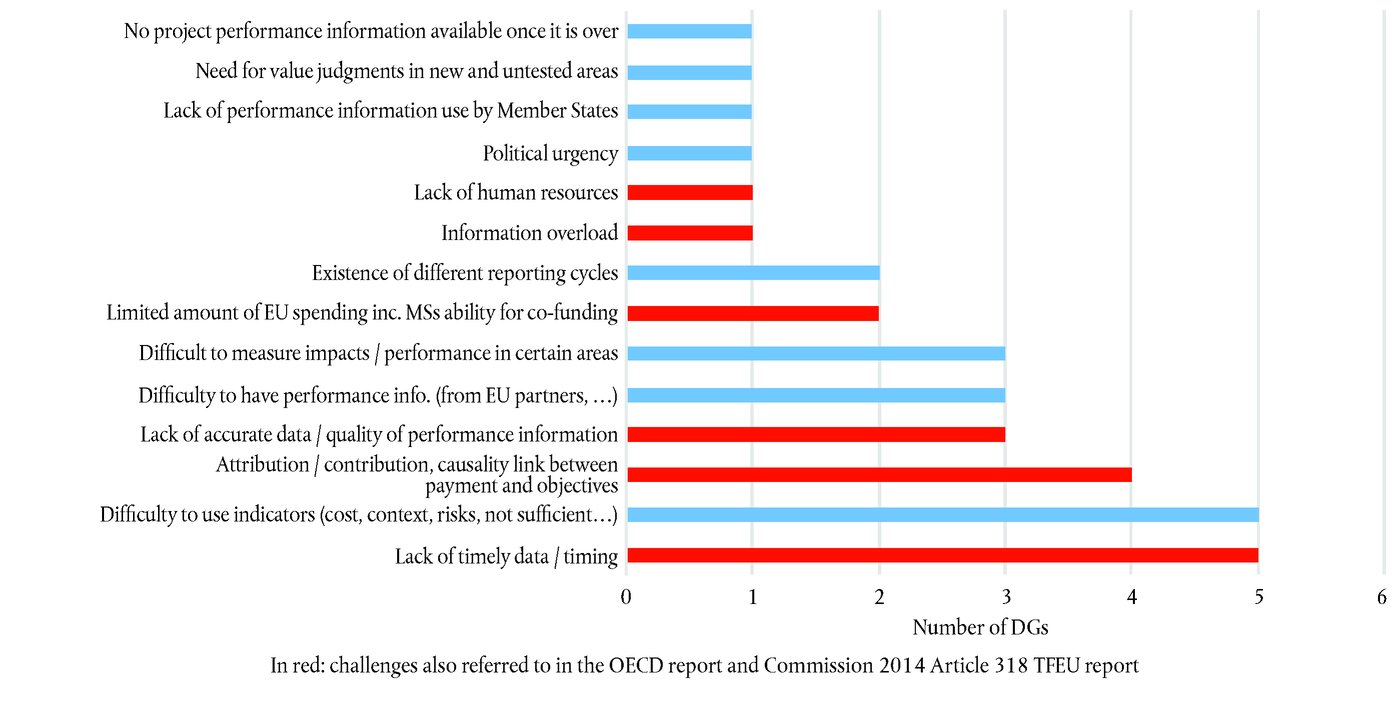

3.33.

|

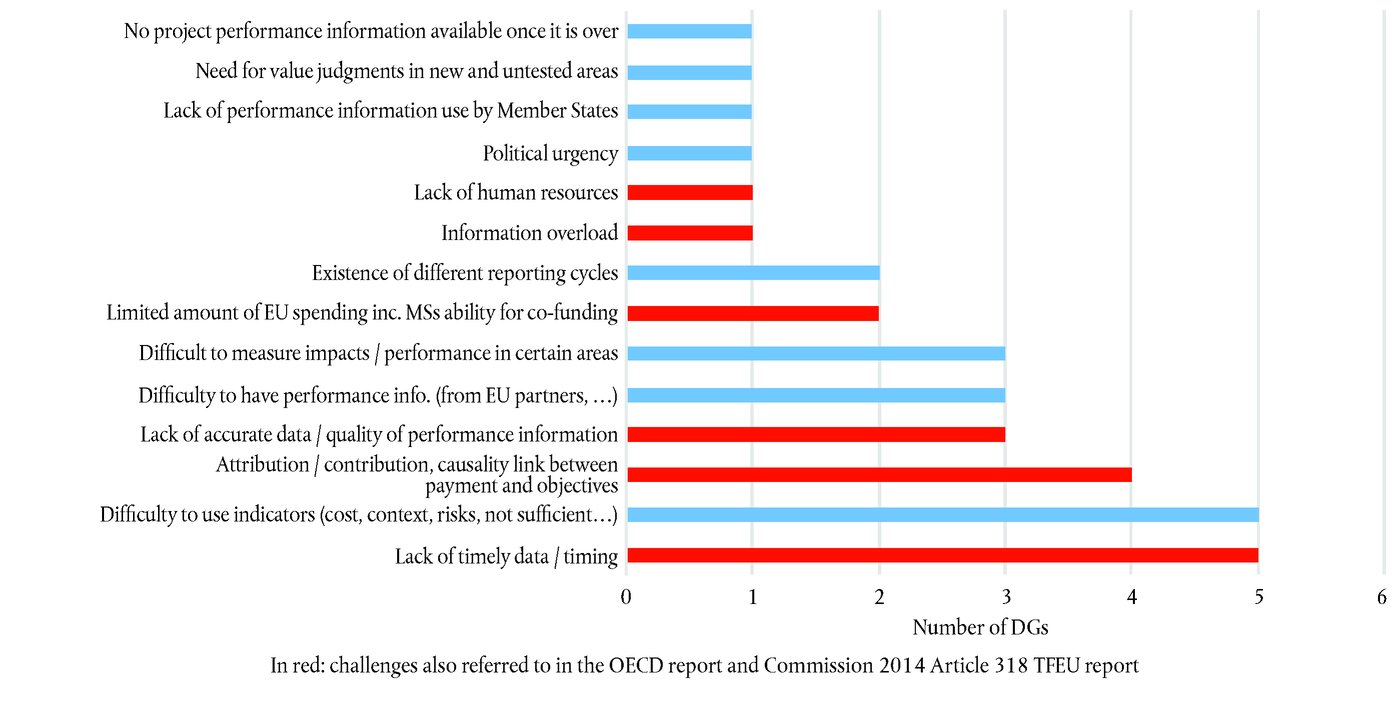

In our meetings with DGs, our interviewees highlighted various challenges (

Box 3.9

). A number of these challenges were were also mentioned in OECD and Commission reports (41)

(42).

|

|

|

|

Box 3.9 — Challenges for using performance information referred to by the six DGs interviewed

Source: ECA.

|

|

THE COURT’S OBSERVATIONS

|

|

|

3.34.

|

Our survey included questions on attitudes to performance (see

Box 3.10

). Although the overall results were positive, respondents' opinions varied widely. The respondents giving negative replies generally used performance information less frequently. We also noted that senior managers used performance information no more frequently than heads of unit did.

|

|

|

|

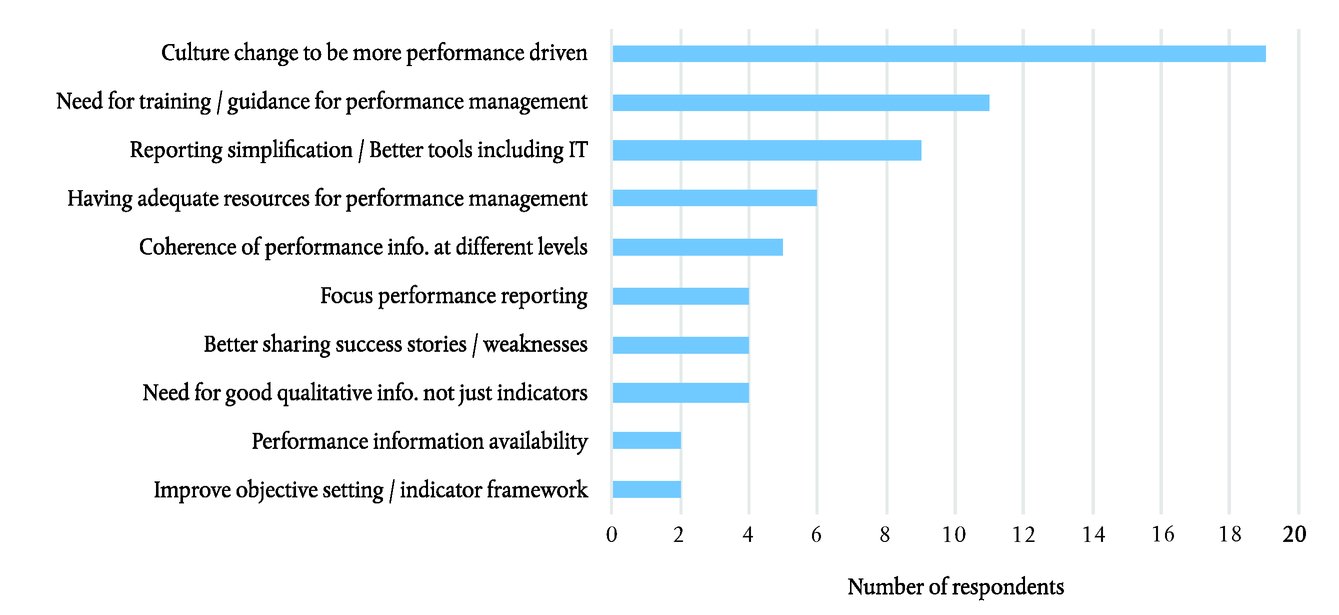

3.35.

|

Furthermore, the results of our survey suggested a strong need for more training on the use of performance information, and better sharing of knowledge about good practices. The DGs we interviewed told us about a number of good practices. In our opinion, these good practices could be shared with other DGs. We also noted some differences in perception. We asked our interviewees whether they agreed that managers, and staff, had a significant role to play in developing performance measures. Of the senior managers we interviewed, 80 % agreed that managers played such a role, and 84 % agreed that staff did. When we asked heads of unit the same question, only 52 % agreed that managers played an important role, and 53 % agreed that staff did. This suggests that the Commission’s senior managers have a more positive view of attitudes to performance at the Commission than middle managers do.

|

|

|

|

Box 3.10 — Survey results — Performance culture

Source: ECA survey.

|

|

THE COURT’S OBSERVATIONS

|

THE COMMISSION’S REPLIES

|

|

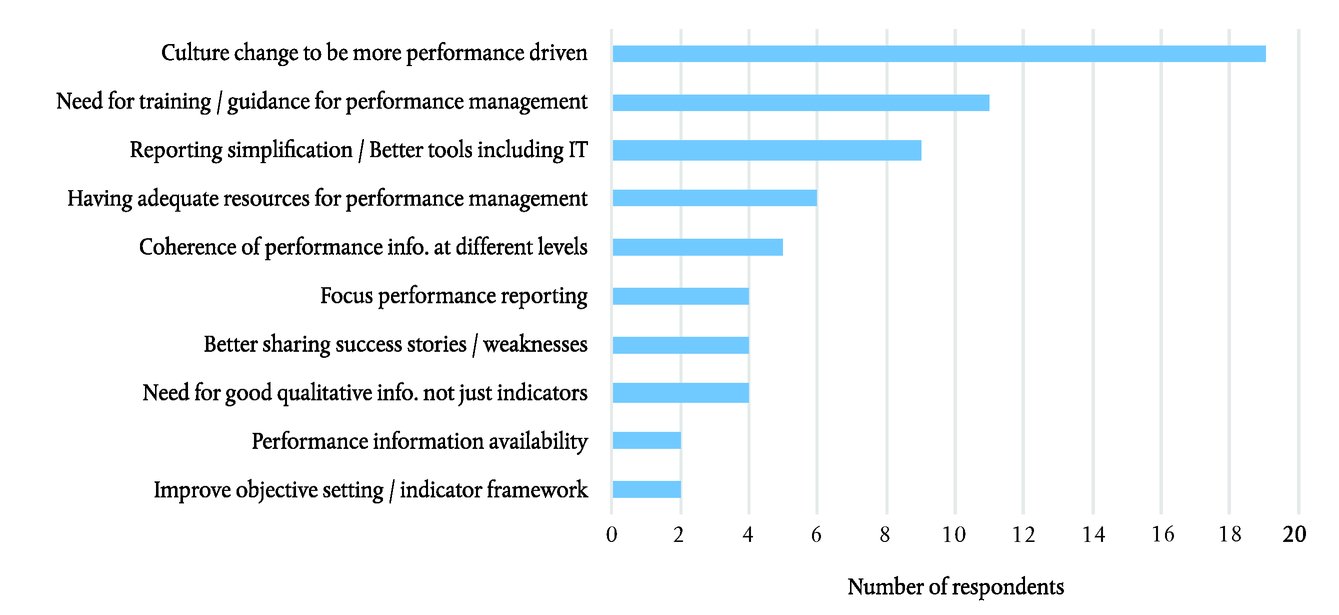

3.36.

|

The replies to our survey mentioned a number of opportunities for progress in terms of using performance information (see

Box 3.11

). Respondents most frequently emphasised the Commission’s need to change its culture to become more performance-driven. They stated that the Commission should focus less on monitoring the absorption of funds and assessing the regularity of expenditure (since the overall error rate affecting the EU budget is declining each year). Instead, it should use performance management techniques more widely, with a focus on achieving planned results and impacts (43).

|

|

|

3.36.

|

Concerning the issue of cultural change, the Commission considers that it already has a very well embedded performance culture in its services: in 2017, the OECD found that ‘The EU system of budgeting for performance and results is advanced and highly specified, scoring more highly than any OECD country in the standard index of performance budgeting frameworks. […] EU budgetary practices include many effective and innovative aspects, which may hold lessons for national governments in reflecting on their own agendas of performance-focused budgetary reform.’ It also found that ‘More generally, the Commission has undertaken extensive streamlining of its reporting in recent years, yielding clearer insights on performance and results including via the new Annual Management and Performance Report (AMPR) ….’ (44).

The Commission would also point to the examples highlighted in paragraph 3.32 above of the steps the Commission has taken to reinforce the performance culture.

|

|

|

Box 3.11 — Last survey question: ‘What would you change so that performance information is better used in your DG?’

Source: ECA survey.

|

|

THE COURT’S OBSERVATIONS

|

|

|

PART 2 — RESULTS OF THE COURT’S PERFORMANCE AUDITS: CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS WITH THE GREATEST IMPACT

|

|

|

Introduction

|

|

|

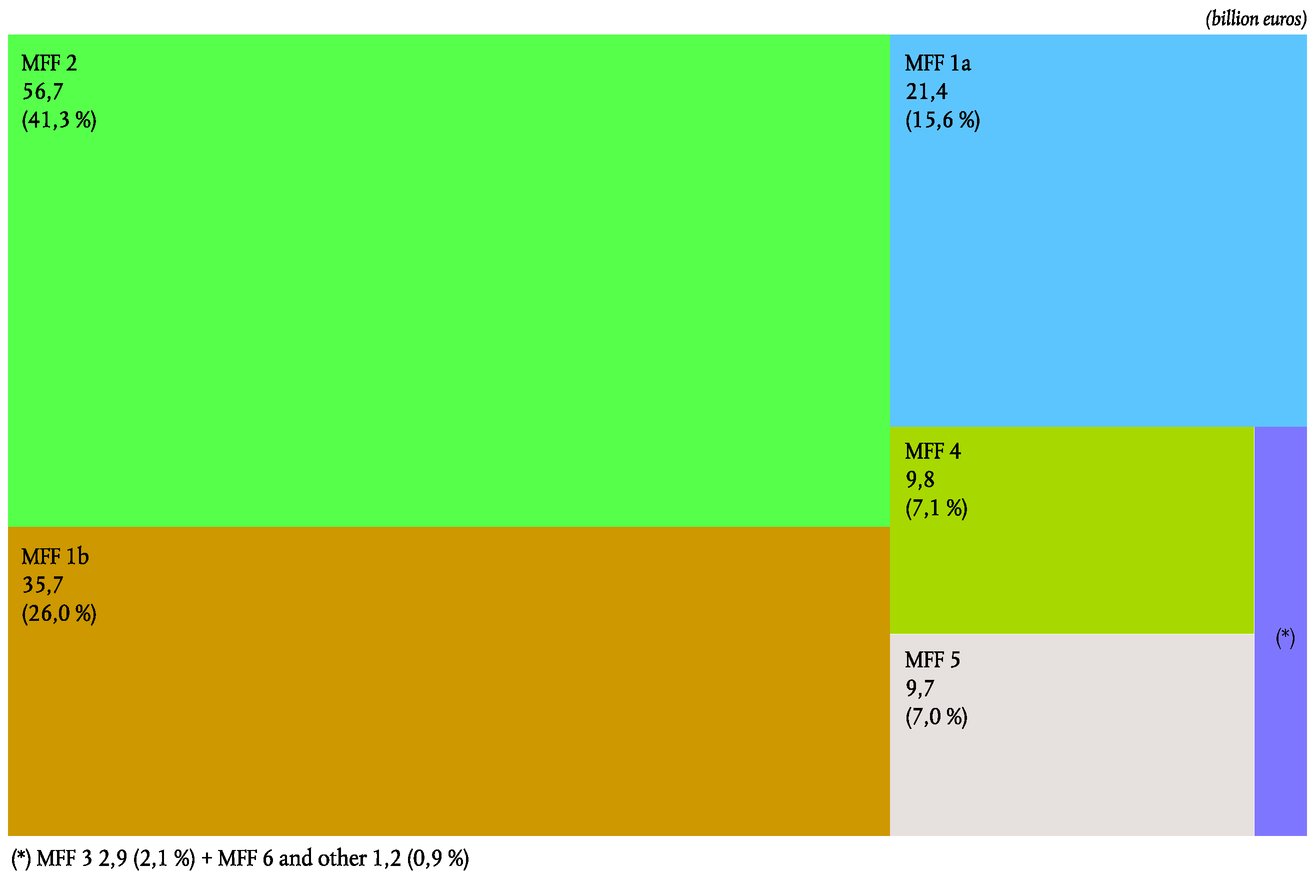

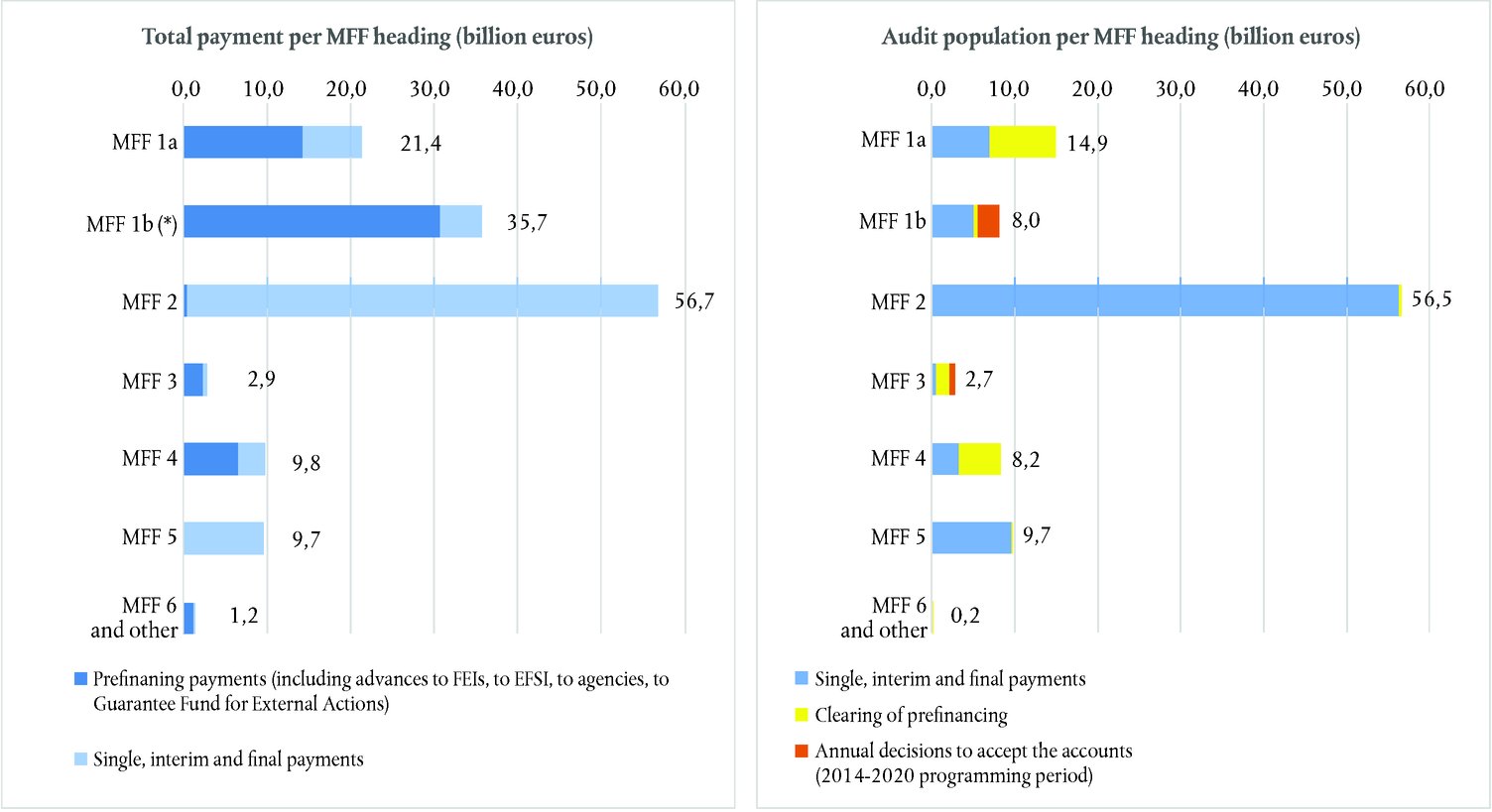

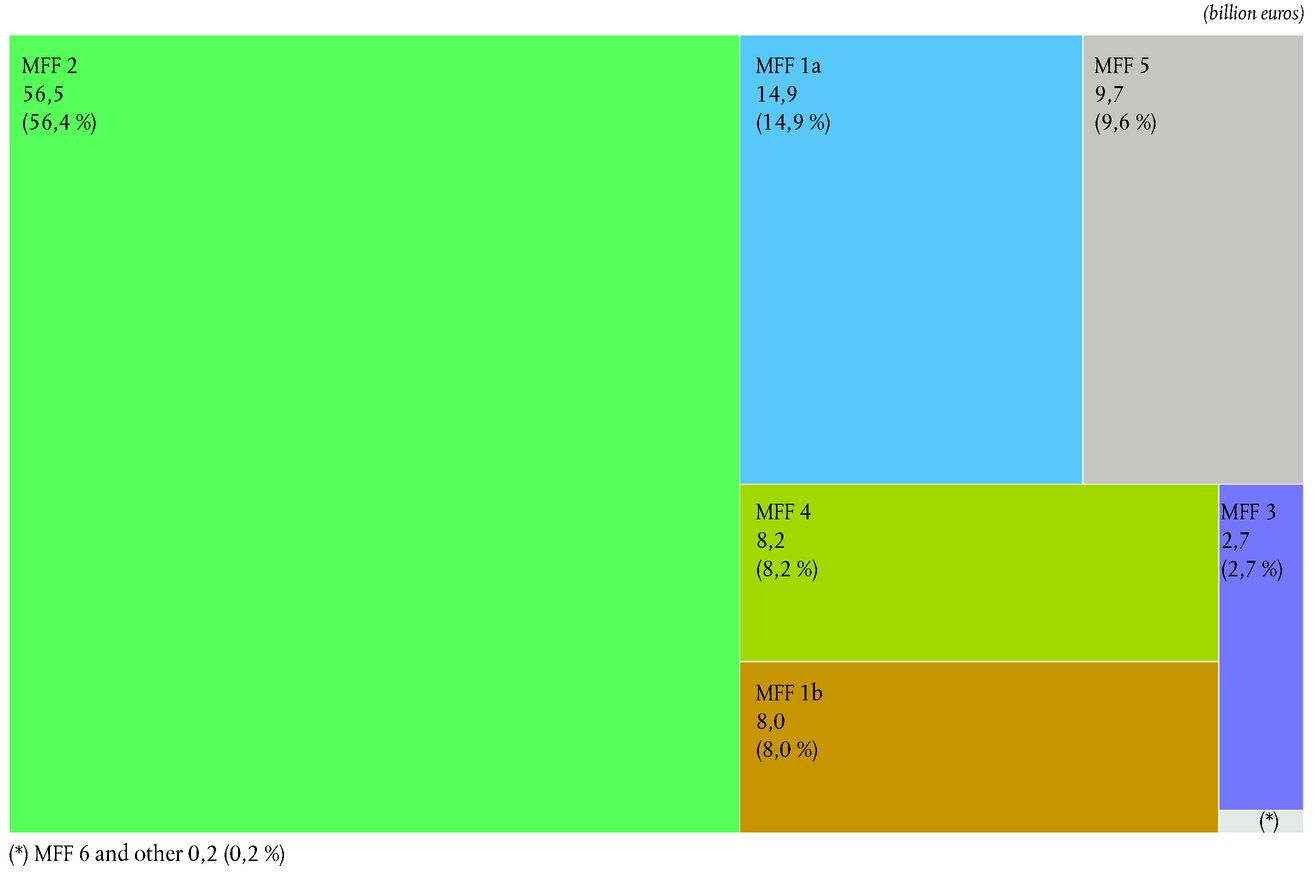

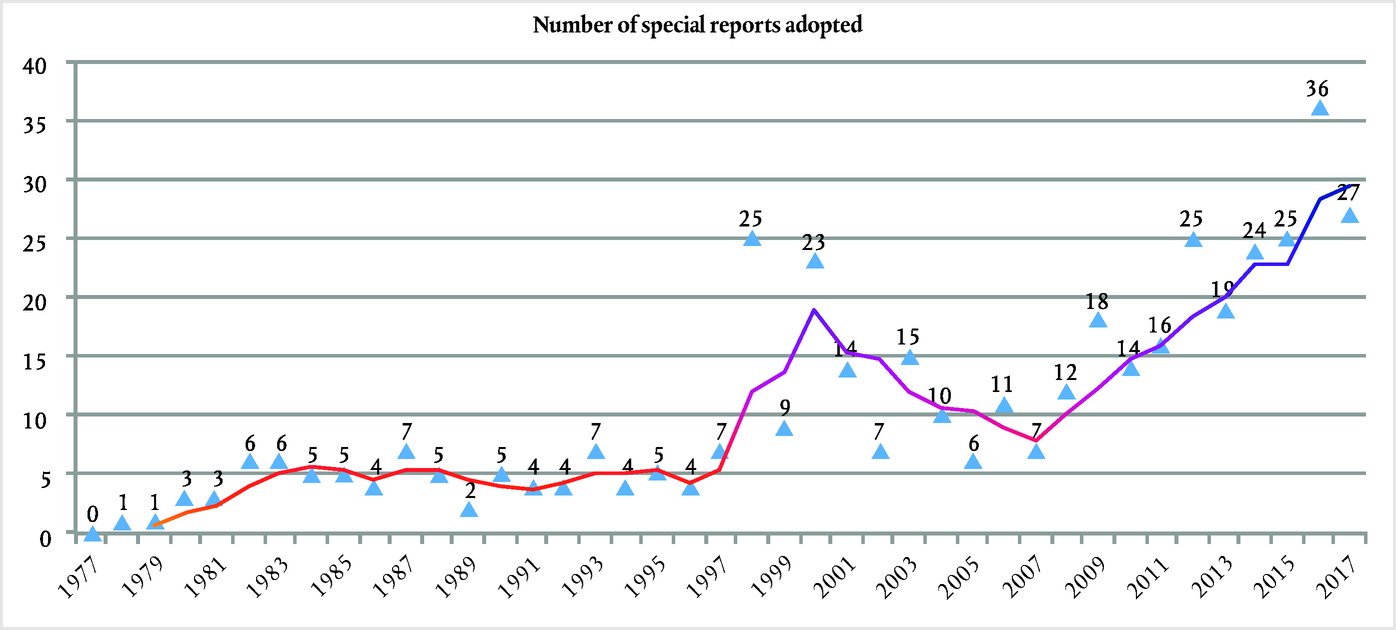

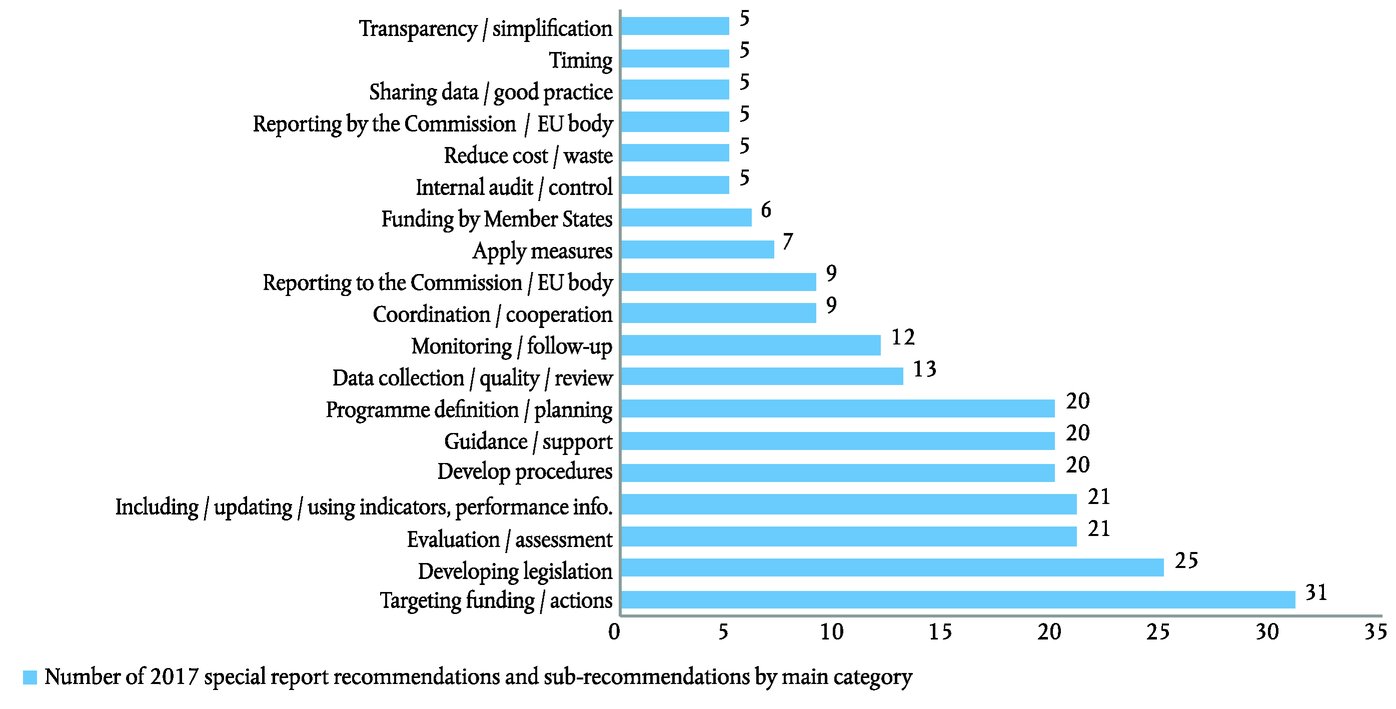

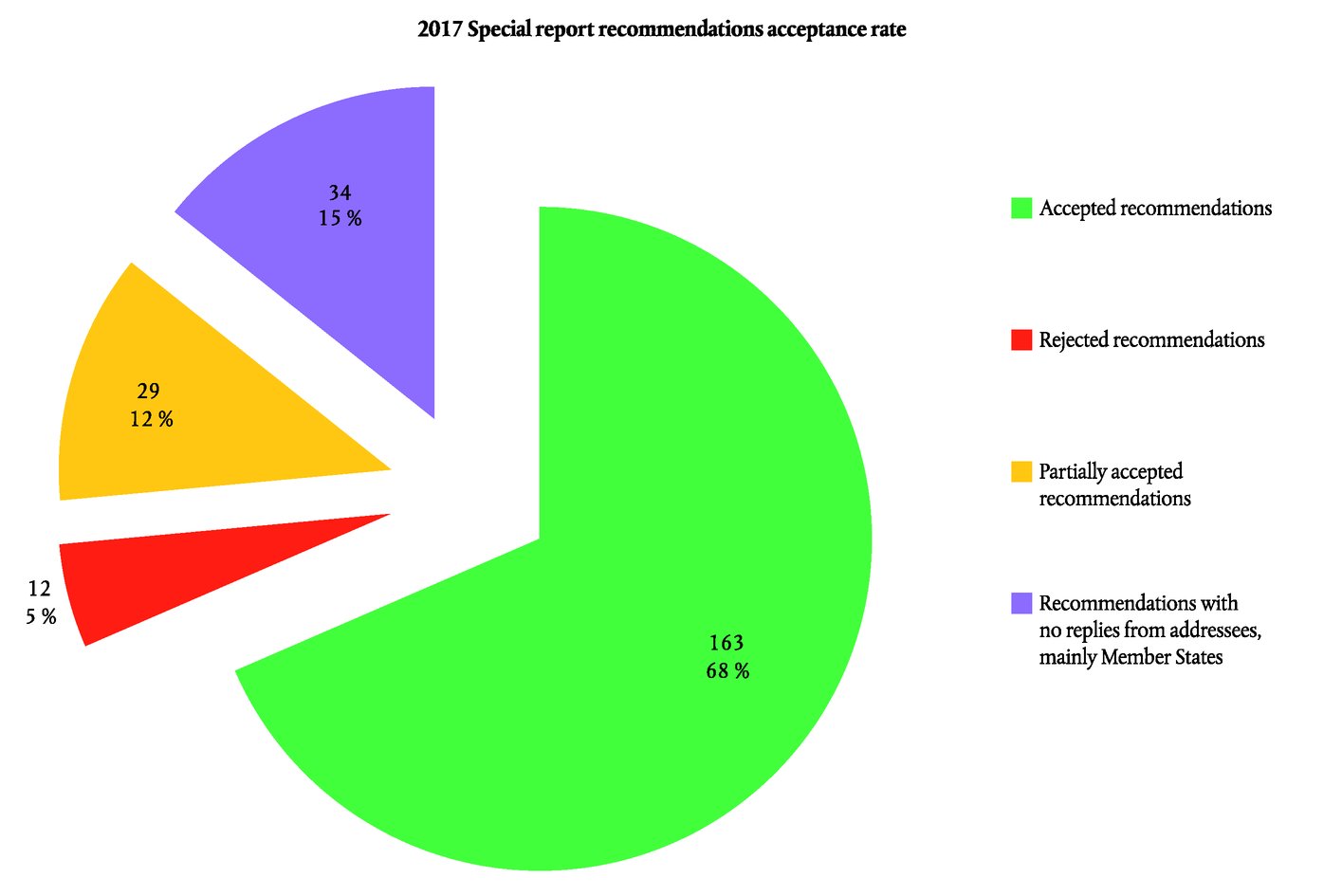

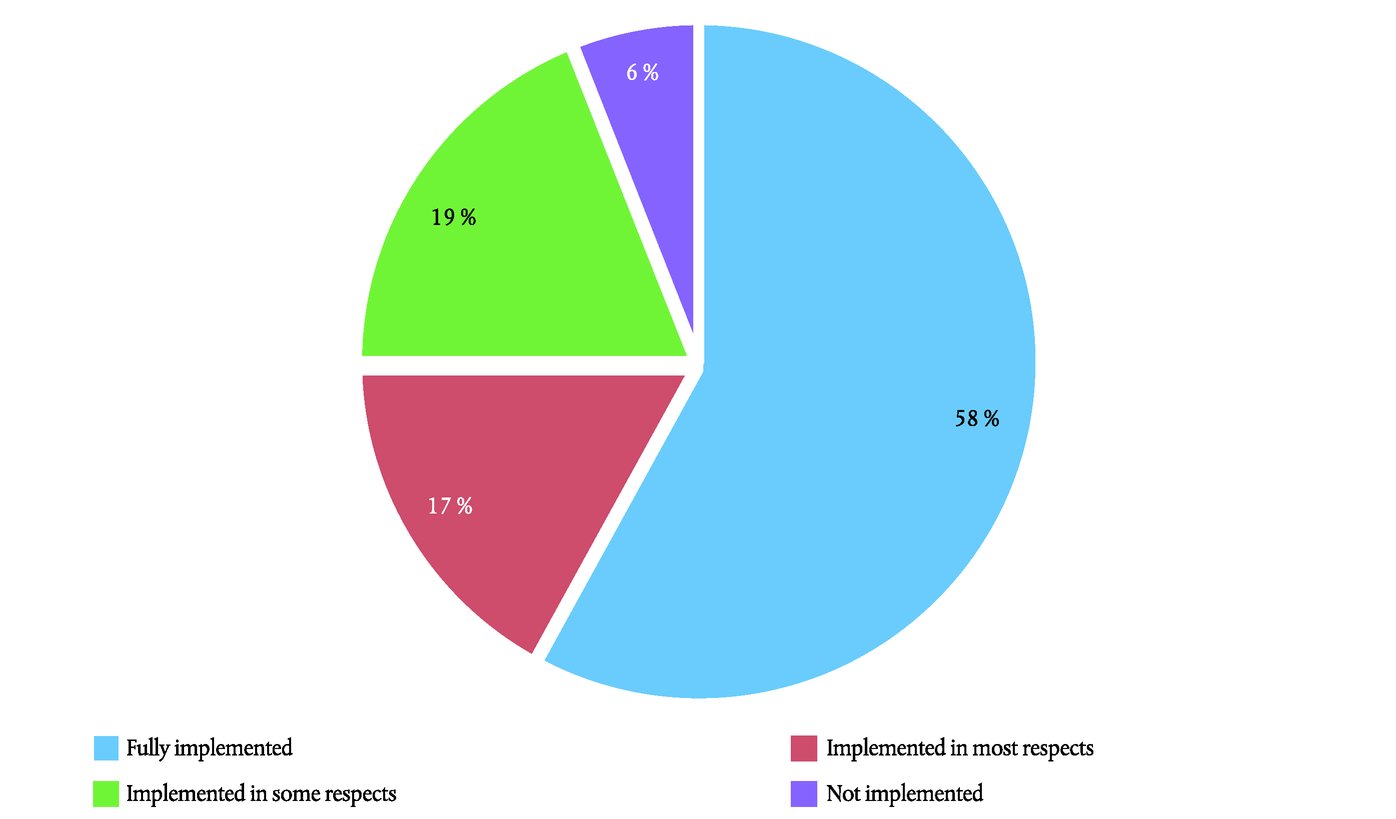

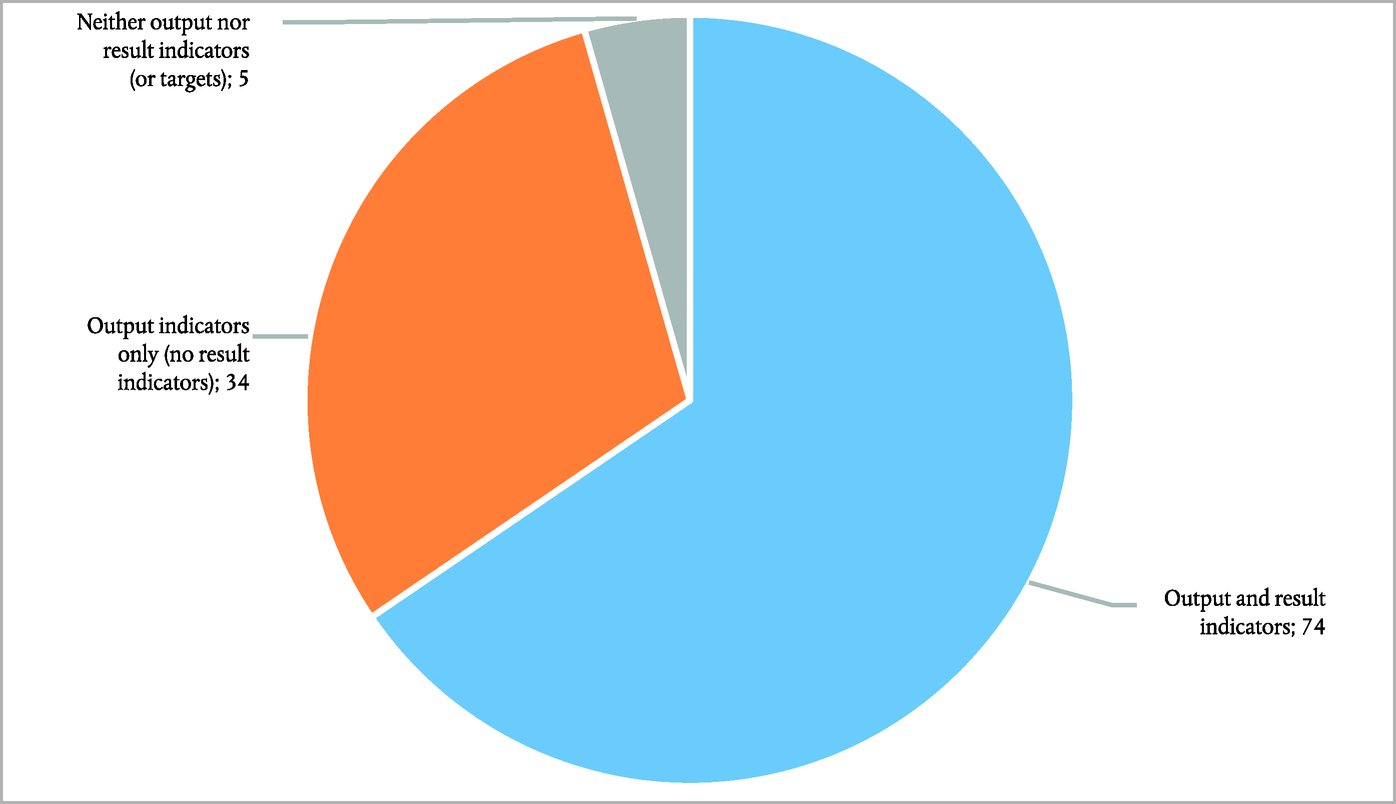

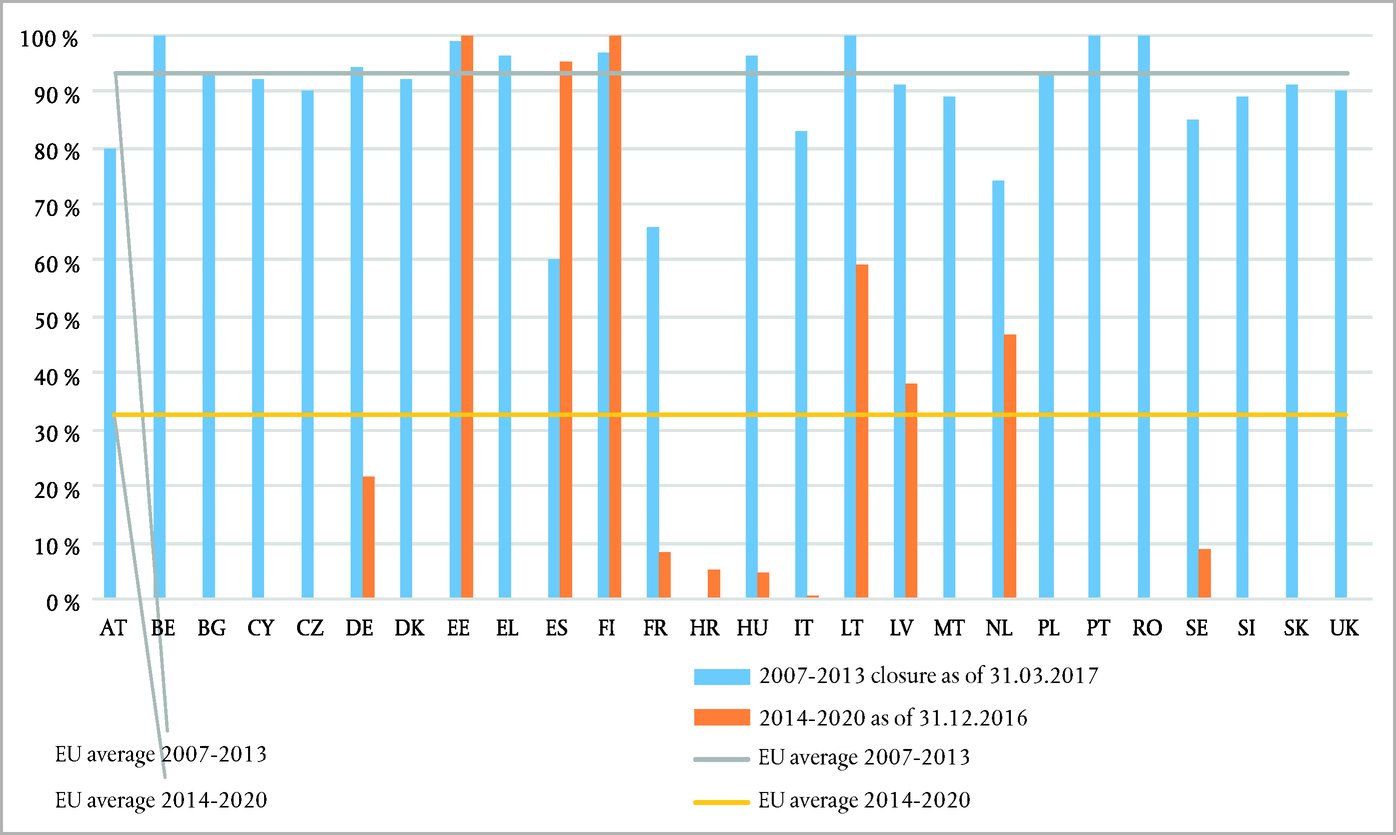

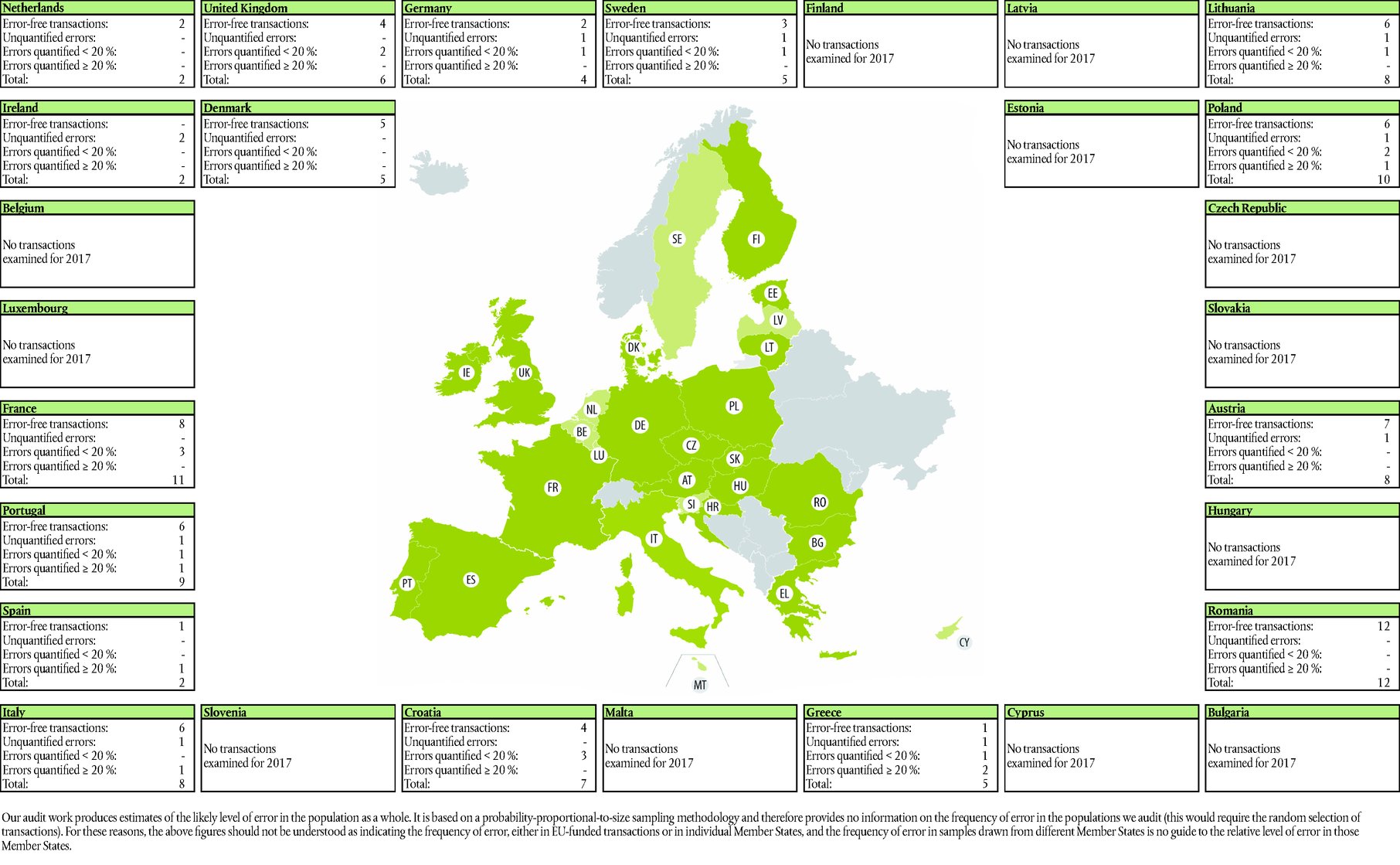

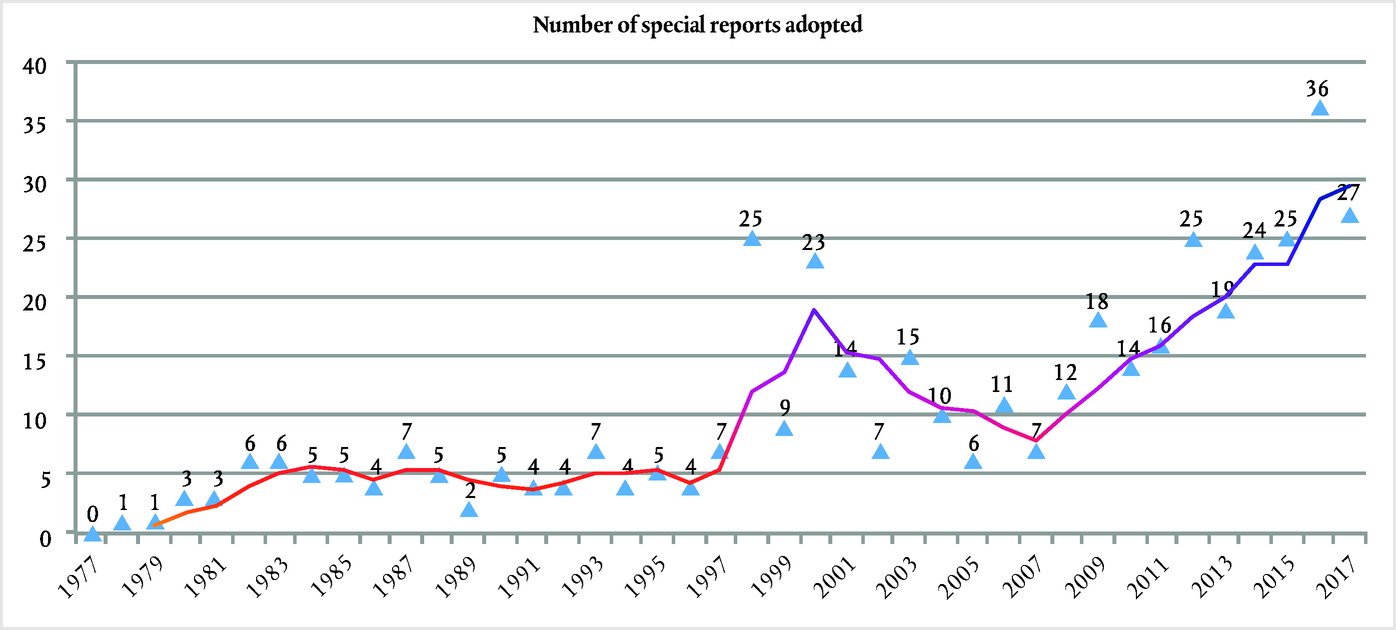

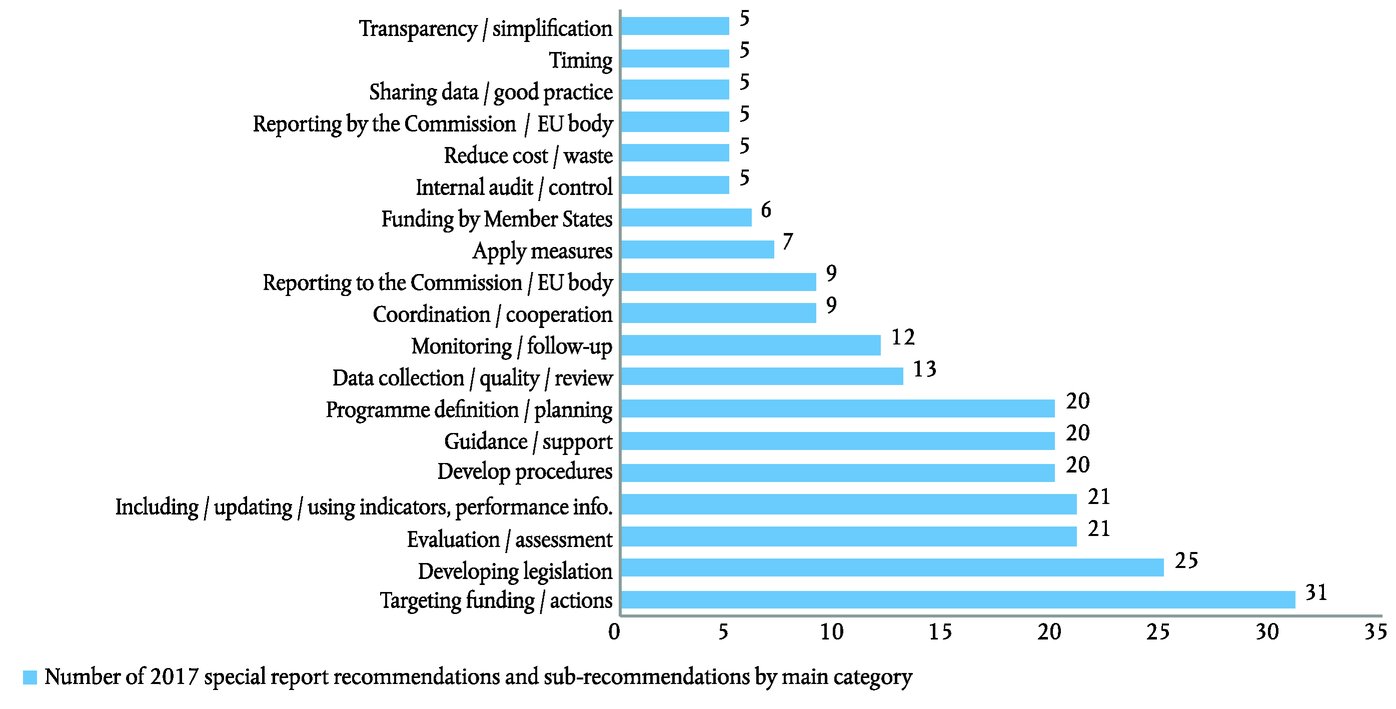

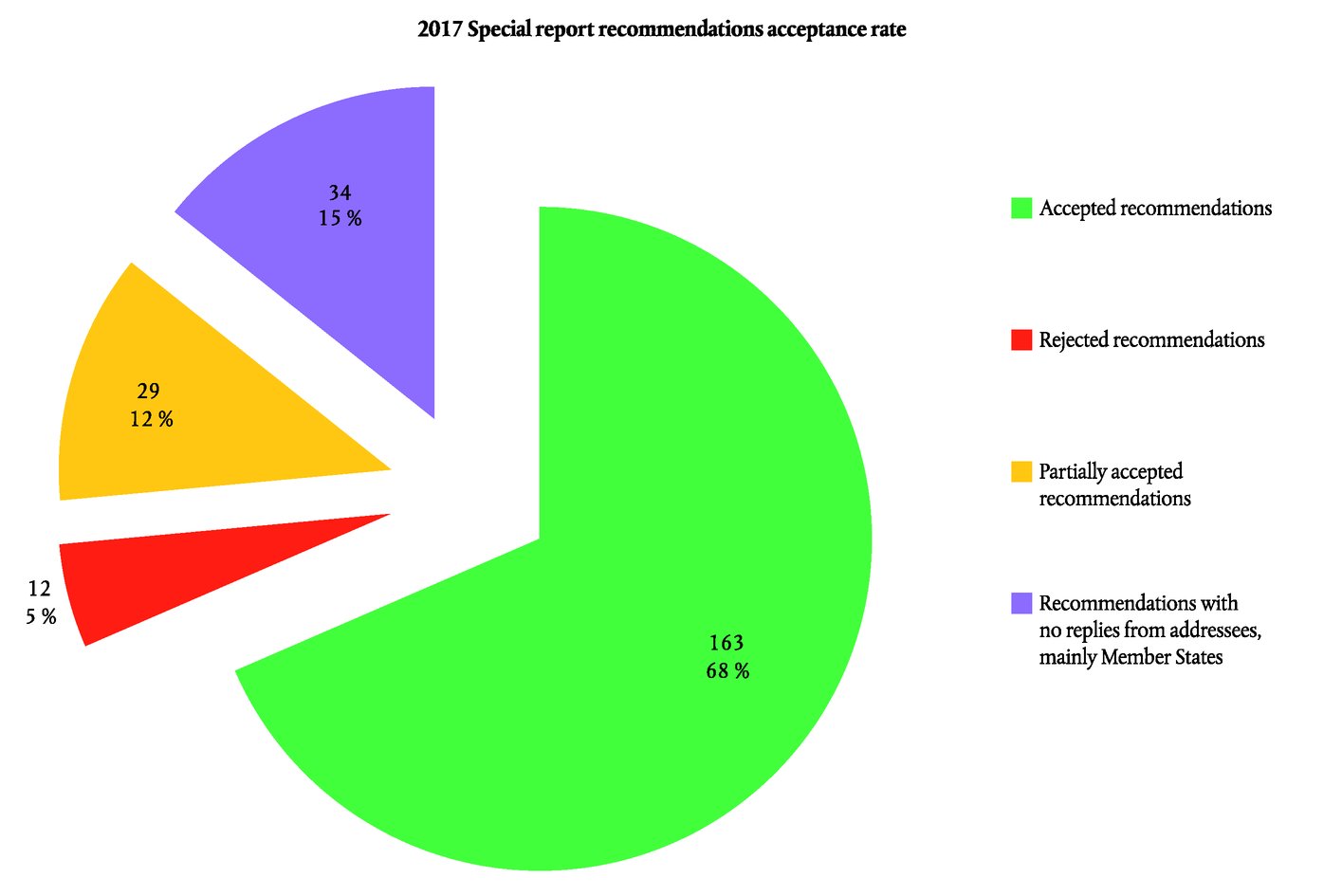

3.37.

|

Each year, we publish a number of special reports in which we examine how well the principles of sound financial management have been applied in implementing the EU budget. In 2017, we adopted 27 special reports (45) (see

Box 3.12

). They covered all multiannual financial framework headings (46) and contained a total of 238 recommendations covering a wide range of topics (

Box 3.13

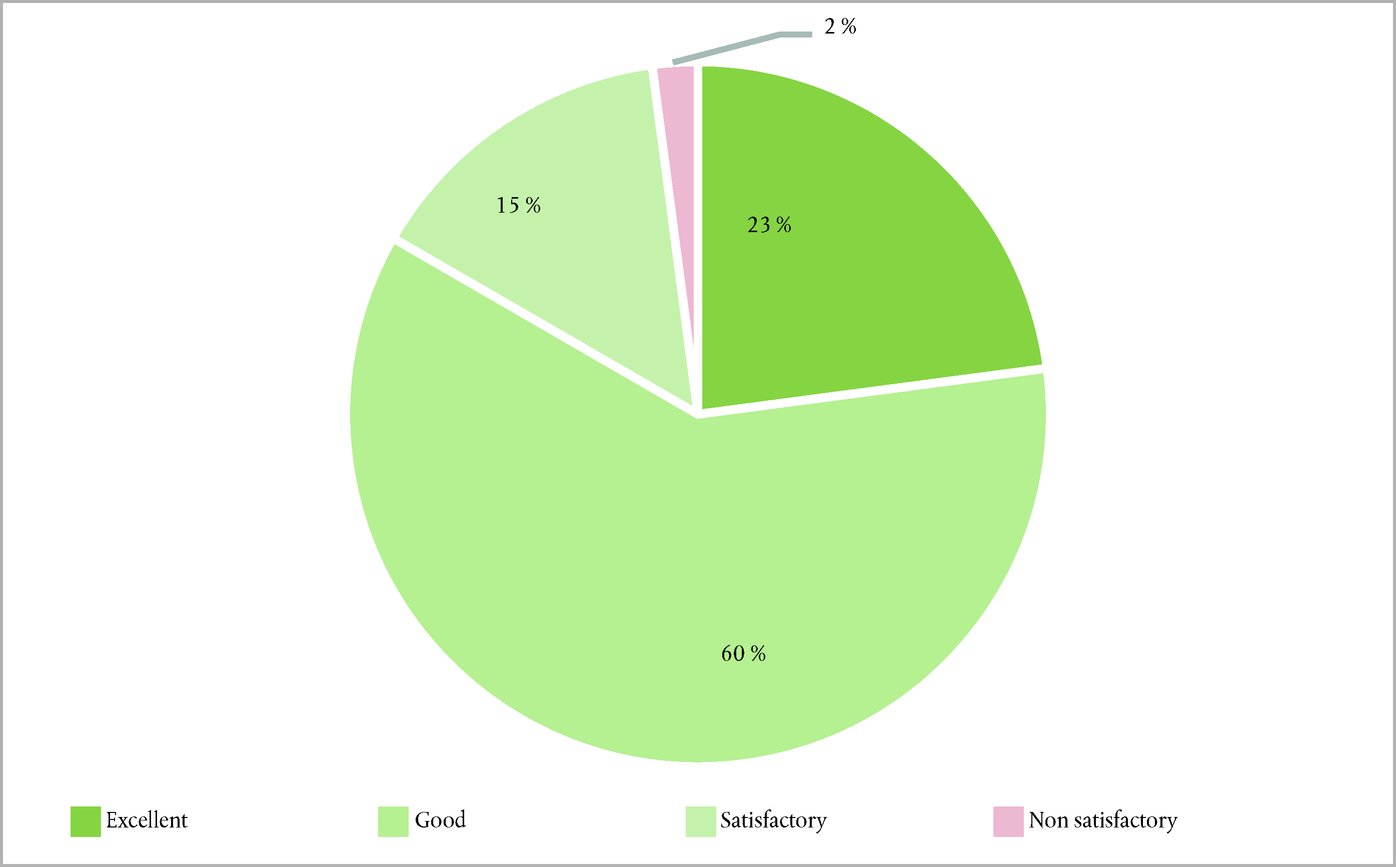

). We also published four special reports in the area of ‘Functioning Single Market and Sustainable Monetary Union’. The published replies to our reports show that more than two thirds of our recommendations were fully accepted by the auditee, which was the Commission in most cases (

Box 3.14

).

Annex 3.3

is a summary of the recommendations addressed to Member States in our 2017 special reports.

|

|

|

|

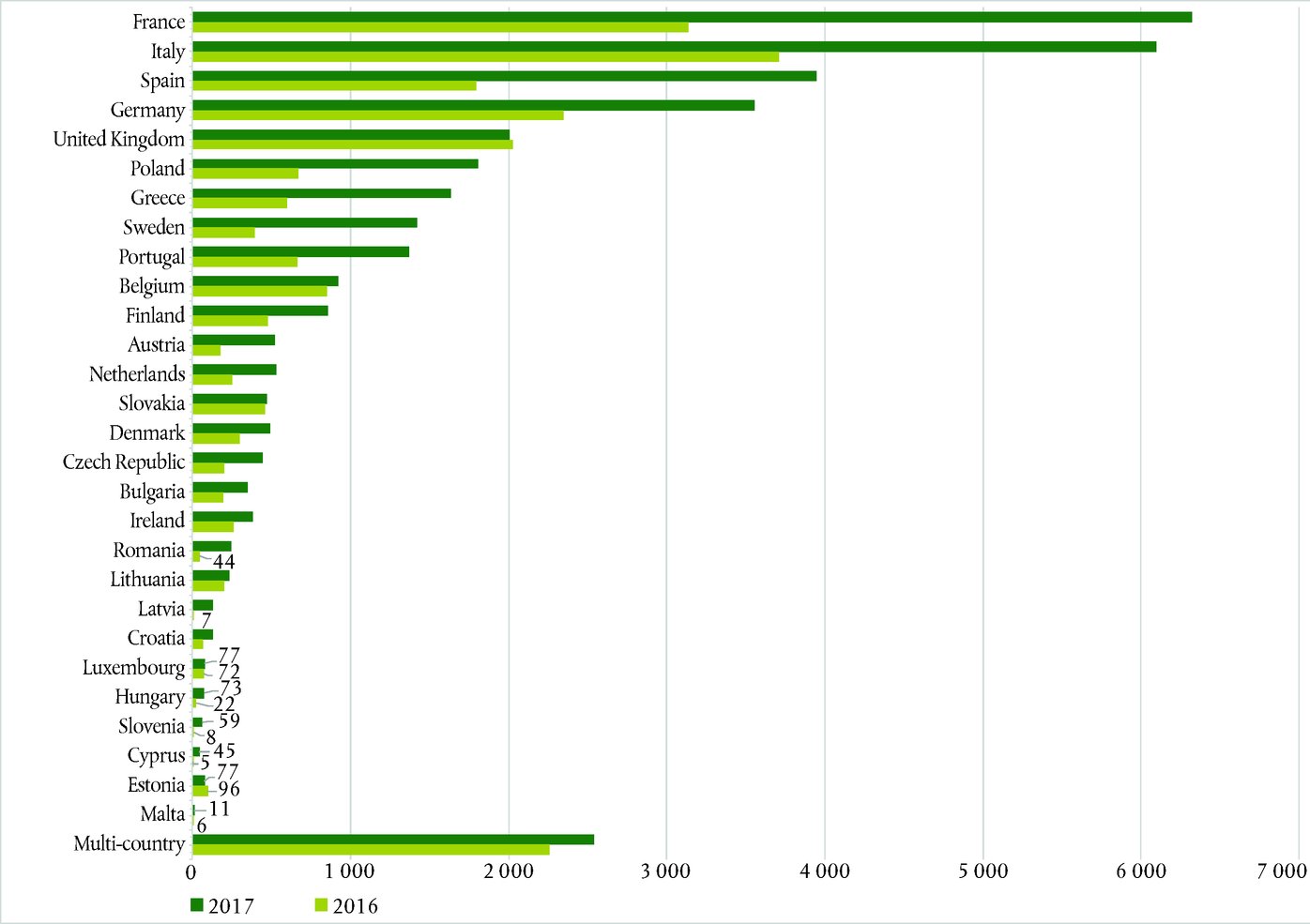

Box 3.12 — A significant number of special reports assessing the implementation of the principles of sound financial management

Source: ECA.

|

|

Box 3.13 — Recommendations cover a wide range of topics

Source: ECA.

|

|

Box 3.14 — Our auditees accept the vast majority of our recommendations

Source: ECA.

|

|

THE COURT’S OBSERVATIONS

|

THE COMMISSION’S REPLIES

|

|

Headings 1a ‘Competitiveness for growth and jobs’ and 1b ‘Economic, social and territorial cohesion’

|

|

|

3.38.

|

In 2017, we adopted seven special reports for these multiannual financial framework headings (47). We wish to draw attention to some key conclusions and recommendations for three of these reports.

|

|

|

| (i) Special report No 2/2017 — The Commission’s negotiation of 2014-2020 Partnership Agreements and programmes in Cohesion

|

|

|

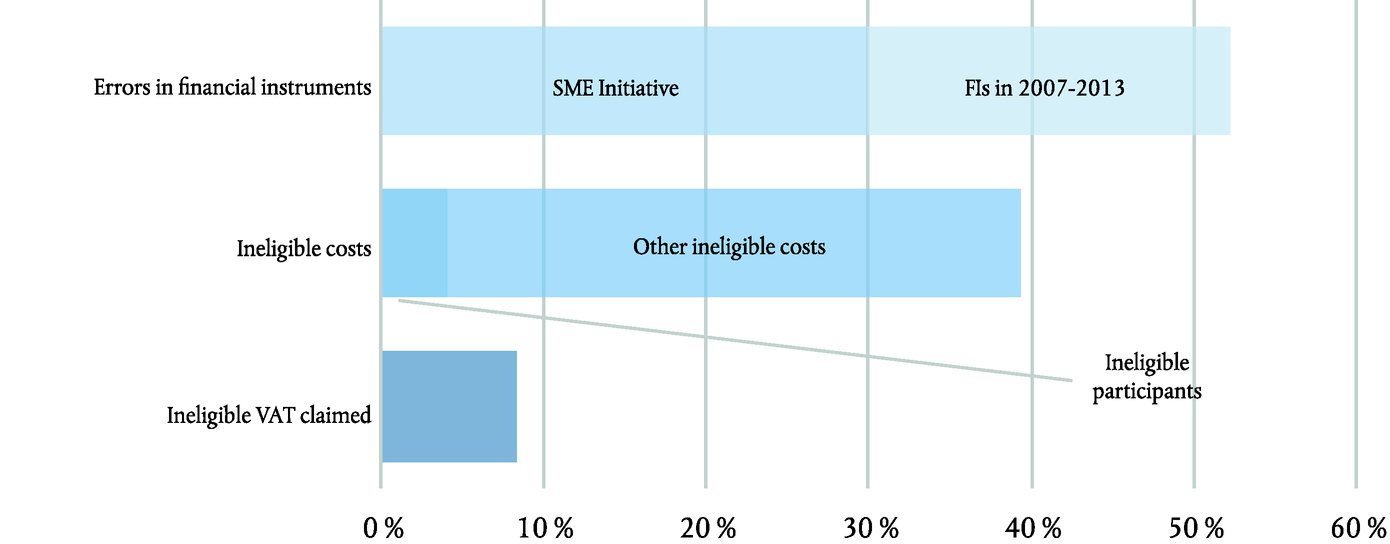

3.39.

|

We found that partnership agreements had been effective in focusing funding on the EU 2020 strategy, and that the operational programmes had a robust ‘intervention logic’. However, programme-specific and common indicators had been set for both output and results. This had created an excessive number of indicators, which risked an additional administrative burden and problems with aggregation at national and EU level.

|

|

|

3.39.

|

The Commission notes that programme specific performance indicators for results are not intended to be aggregated at EU level. Those specific indicators are suited for target setting and reporting on performance in relation to the targets, while common indicators allow reporting on achievements based on pre-defined categories that reflect frequently used investments across the EU. Programme-specific output indicators refer to the physical products that allow grasping the changes achieved by the EU-funded interventions in programmes. These interventions are tailor-made to resolve place-based development bottlenecks. By definition, these need to be specific to the region and action foreseen.

|

|

|

3.40.

|

We recommended that:

|

|

3.40.

|

|

—

|

Member States should discontinue the use of unnecessary programme specific indicators; and that

|

|

|

|

—

|

the Commission should define a common terminology for ‘outputs’ and ‘results’ and propose it for inclusion in the Financial Regulation, determine the most relevant output and result indicators for performance measurement, and apply performance budgeting.

|

|

|

—

|

A coherent performance terminology is included in the revised Financial Regulation. The definition of output and result indicators is now reflected in the Commission’s proposal for a Common Provisions Regulation for the post-2020 programming period (COM(2018) 375 final). The Commission’s proposal for a Regulation on the European Regional Development Fund and on the Cohesion Fund for the post-2020 programming period (COM(2018) 372 final) includes a list of common output and result indicators. This list of common indicators is more extensive than the one for the 2014-2020 period, which is expected to help reducing the number of the programme specific indicators.

Regarding the concept of performance budget, the Commission notes that the EU Budget is already a performance budget which enables the budgetary authority to take performance information into account during the budgetary process by providing information on the objectives of the programmes and the progress in achieving them in the Programme Statements attached to the Draft Budget.

|

|

| (ii) Special report No 5/2017 — Youth unemployment

|

|

|

3.41.

|

We found that, while some progress had been made in implementing the Youth Guarantee, and while some results had been achieved, the situation fell short of the initial expectations raised at the launch of the Youth Guarantee, the aim of which was to provide all young people not in employment, education or training with a good-quality offer of employment, continued education, apprenticeship or traineeship within four months of leaving school or becoming unemployed. We found that the contribution of the Youth Employment Initiative to the achievement of the Youth Guarantee objectives was very limited at the time of the audit.

|

|

|

3.41.

|

Since 2014, when implementation started on the ground, each year there were more than 5 million registrations in the Youth Guarantee and each year since 2014 there were more than 3,5 million exits to employment, education, traineeship or apprenticeship (source: DG EMPL Youth Guarantee database). There are now 2,2 million fewer unemployed young people and 1,4 million fewer young people not in employment, education or training (source: Eurostat). YEI-funded actions will continue to run at least until 2023 and support more young people NEET.

To ensure that young people living in Member States struggling with youth unemployment may continue to receive support, the proposal of the Commission for the European Social Fund Plus (ESF+) for 2021-2027 requires that Member States facing high rates of young people not in employment, education and training (NEET) allocate at least 10 % of their ESF+ resources to youth employment actions. The proposal draws lessons from 2014-2020 and also simplifies some of the requirements with a view to facilitating the roll-out of measures which are key for the implementation of the Youth Guarantee.

|

|

|

3.42.

|

We recommended, in particular, that the Member States should:

|

|

3.42.

|

|

—

|

produce a complete overview of the cost of implementing the Youth Guarantee for the entire young people not in employment, education or training population, and prioritise measures to be implemented according to available financing;

|

|

|

—

|

The Commission notes that the recommendation is primarily addressed to Member States.

The Commission would indeed welcome a better overview of the estimated cost of all planned measures to implement the Youth Guarantee and will wherever possible and upon request of the Member States, support Member States in this process.

|

|

|

—

|

ensure that offers are only considered to be of good quality if they match the participant’s profile and labour market demand and lead to sustainable integration in the labour market.

|

|

|

—

|

The Commission notes that the recommendation is addressed to Member States.

The Commission will explore the possibility of discussing standards for quality criteria in the context of the work on Youth Guarantee monitoring in EMCO.

|

|

| (iii) Special report No 15/2017 — Ex ante conditionalities and performance reserve in Cohesion

|

|

|

3.43.

|

In this special report, we found that that ex-ante conditionalities provided a consistent framework for assessing the Member States’ readiness to implement EU funds at the start of the 2014-2020 programme period. However, the extent to which this had led to changes on the ground was unclear. We concluded that the performance framework and reserve was unlikely to trigger a significant reallocation of Cohesion spending during the 2014-2020 period to better-performing programmes.

|

|

|

3.43.

|

The Commission considers that in relation to the changes on the ground caused by ex ante conditionalities, the mere fact of imposing minimum conditions which had not existed in any of the former cohesion policy frameworks, should improve effectiveness and efficiency of spending.

The Commission will be able to assess the final impact of ex ante conditionalities after the projects programmes are implemented.

Moreover, the performance framework is just one of several elements of the result orientation. The performance framework and performance reserve were established to support the focus on performance and the attainment of the objectives of the Union's strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. They were not designed to result in significant reallocation of Cohesion spending. Nonetheless, if programmes fail to achieve the milestones set in the performance framework, the performance reserve may be reallocated to other, better performing programmes.

|

|

|

3.44.

|

We recommended that the Commission should:

|

|

3.44.

|

|

—

|

further develop ex-ante conditionalities as an instrument to assess Member States’ readiness to implement EU funds; and

|

|

|

—

|

The Commission accepted the recommendation under the condition that ex ante conditionalities are maintained for post-2020.

|

|

|

—

|

turn the performance reserve for the post-2020 period into a more results-oriented instrument that allocates funds to those programmes that achieved good results.

|

|

|

—

|

The Commission accepted the recommendation under the condition that the performance framework and reserve are maintained for post-2020.

The Commission’s proposal for a Common Provisions Regulation for the post-2020 programming period (COM(2018) 375 final) lays down the provisions for the performance framework which consists of both output and result indicators for which milestones and targets need to set. The performance review is replaced by the mid-term review which shall be based, among others, on the progress in achieving — by end 2024 — the milestones of the performance framework.

|

|

|

Heading 2 ‘Sustainable growth and natural resources’

|

|

|

3.45.

|

In 2017, we adopted six special reports linked to multiannual financial framework heading 2 (48). Three of these reports examined aspects of the performance of the Common Agricultural Policy. Their conclusions are particularly relevant in the context of the ongoing Common Agricultural Policy reform and the new performance-based delivery model announced in the Commission’s ‘Communication on the Future of Food and Farming’.

|

|

|

| (i) Special report No 16/2017 — Rural development programming

|

|

|

3.46.

|

In this special report, we noted that, in the current period, rural development spending was to be focused more on results, but that this ambition had not been achieved due to a lack of relevant performance information. We recommended that a common set of result-oriented indicators be developed, and that these should be suitable for assessing the results and the impact of rural development interventions.

|

|

|

3.46.

|

In its reply to recommendation 4 of SR 16/2017, the Commission committed to analyse possible ways to improve the performance measurement of the CAP as a whole.

On 1 June 2018, the Commission adopted a Proposal for a Regulation COM(2018) 392 final (CAP strategic plans): In the framework of the new delivery model common result-orientated indicators have been developed: Title VII of the Regulation introduces the performance monitoring and evaluation framework laying down rules on what and when Member States have to report progress on their CAP Strategic Plans and rules on how this progress will be monitored and evaluated.

|

|

| (ii) Special report No 10/2017 — Generational renewal

|

|

|

3.47.

|

We concluded that the objectives and expected results of EU support to young farmers were not well defined. We recommended that the intervention logic should be improved. To this end, we recommended that the Commission should improve the needs-assessment procedure, select those forms of support which best match identified needs, and define specific and quantified results targets.

|

|

|

3.47.

|

In its reply to recommendation 1 of the SR 10/2017, the Commission committed to analyse and consider possible relevant policy instruments for the support to young farmers and their logic of intervention in the context of the preparation of future legislative proposals.

On 1 June 2018, the Commission adopted a Proposal for a Regulation COM(2018) 392 final (CAP strategic plans): In the new delivery model of the proposal, Member States will design CAP Strategic Plans, including an ex-ante assessment of needs. On this basis, tailor-made interventions that address the identified needs and aim to implement the policy objectives will be described in the plans. Among others, the following specific objective is laid down in Article 6 (g) of the Regulation: Attract young farmers and facilitate business development in rural areas. In relation to this objective, a specific result indicator will be used to quantify both the ex-ante target value and the actually realised value.

In terms of procedure, the Commission will assess and approve these CAP Strategic Plans.

|

|

| (iii) Special report No 21/2017 — Greening measures

|

|

|

3.48.

|

We concluded that the Commission had not specified what greening measures were expected to achieve. We also concluded that there was a significant amount of deadweight, and that requirements were low. For these reasons, we concluded that greening was unlikely to lead to significant improvements to the environment and the climate. We recommended that the Commission develop a complete intervention logic for the EU’s agriculture measures aimed at environmental and climate protection. We recommended that the intervention logic should be based on up-to-date scientific understanding, and should include specific targets. We further recommended that all existing environmental requirements should be combined to form a new environmental baseline applicable to all Common Agricultural Policy beneficiaries, and that programmed measures should go beyond this environmental baseline and focus on the attainment of performance targets.

|

|

|

3.48.

|

The Commission accepted the recommendations of SR 21/2017 in substance.

On 1 June 2018, the Commission adopted a Proposal for a Regulation COM(2018) 392 final (CAP strategic plans), which develops the intervention logic of a new set of environmental and climate-related instruments of the CAP. This new green architecture includes an enhanced conditionality that links full receipt of CAP support to the compliance by beneficiaries of basic standards concerning the environment, climate change, public health, animal health, plant health and animal welfare, including issues previously dealt with under greening. Conditionality applies to all CAP beneficiaries and forms the core of the environmental and climate baseline, beyond which voluntary schemes such as a new Pillar I eco-scheme and agri-environment-climate (AEC) commitments under Pillar II as part of a broader type of intervention offering support for various kinds of management commitment will be defined by Member States. All these measures will be part of a programmed approach focusing on the attainment of performance targets.

|

|

|

Headings 3 ‘Security and citizenship’ and 4 ‘Global Europe’

|

|

|

3.49.

|

We adopted five special reports (49) concerning these multiannual financial framework headings. We wish to draw attention to some key conclusions and recommendations for four of these reports.

|

|

|

| (i) Special report No 3/2017 — Tunisia

|

|

|

3.50.

|

We found that EU aid to Tunisia had generally been well spent. It had contributed significantly to the country’s democratic transition and economic stability after the revolution of 2010-2011. However, we found that the Commission had been too ambitious. It had tried to address too many priorities in a relatively short period. This had led to a number of shortcomings in the Commission’s management of aid.

|

|

|

3.50.

|

The report recognises that the EU aid to Tunisia has been generally well spent. In fact, EU assistance contributed significantly to the country's economic and political stability after the revolution, notably by accompanying major socio-economic and political reforms.

On the ambition level of the Commission, the Commission notes that several areas had to be tackled because of the socioeconomic challenges Tunisia was confronted with following the revolution. Results obtained so far are good since EU assistance contributed significantly to improve socioeconomic and political stability in the country after the revolution. The Commission stresses that it has followed its own policy of concentrating its assistance. Indeed, in spite of the fact that a variety of activities have been undertaken over the period under review, these were in line with the three main sectors identified in the SSF 2014-16.

Effectiveness and sustainability of the Commission’s assistance have been always some of the key elements considered, together with relevance, efficiency and impact. The Commission also has supported the setting up of internal and external monitoring mechanisms and the reinforcement of accountability of public bodies.

|

|

|

3.51.

|

We recommended that the Commission, and where applicable the European External Action Service, should:

|

|

3.51.

|

|

—

|

improve the programming and focus of EU support,

|

|

|

—

|

The Commission accepted the recommendation and is already implementing it (adoption in August 2017 of the new SSF 2017-2020 which focuses on 3 sectors of intervention; continuous policy and political dialogue, coordination with regional programmes; joint programming process ongoing).

|

|

|

—

|

improve the implementation of EU budget-support programmes,

|

|

|

—

|

The Commission accepted the recommendation.

With today's more stable political context in Tunisia and in view of close coordination with other donors, the Commission agrees that the performance indicators can now be more focused for future operations. However, a dynamic approach will continue to apply to eligibility criteria, in line with budget support guidelines provisions.

|

|

|

—

|

make proposals to speed up the macro-financial assistance approval process,

|

|

|

—

|

The Commission accepted the recommendation.

The Commission notes that, even though significant progress has been achieved regarding the speed of the adoption by the Parliament and the Council of MFA decisions, there is still room for improvement. More speedy adoptions could be achieved for instance if the number of meetings of the Committee on International Trade of the European Parliament (INTA) before an INTA vote could be reduced, if the Parliament approval would systematically take place at the plenary (including mini-plenaries) immediately following the INTA vote, if mini-plenaries could be used for the signatures by the Presidents of the Parliament and the Council and if the Council would also make use of the written procedure for adoptions if necessary.

The Commission also notes that, following previous recommendations by the European Court of Auditors and a Resolution on MFA of the Parliament in 2003, it had proposed in 2011 a Framework Regulation for MFA aimed, inter alia, at expediting decision-making by replacing the legislative decisions by implementing acts. However, as the co-legislators decided to retain legislative acts and the ordinary legislative procedure, the Commission withdrew this proposal in 2013.

|

|

|

—

|

improve the planning of projects.

|

|

|

—

|

The Commission accepted the recommendation.

|

|

| (ii) Special report No 6/2017 — The ‘hotspot’ approach

|

|

|

3.52.

|

We concluded that, overall, the hotspot approach had helped improve migration management in the two frontline Member States, Greece and Italy, by increasing their reception capacities, improving registration procedures, and by improving the coordination of support.

|

|

|

|

3.53.

|

We recommended that the Commission and the relevant agencies should:

|

|

3.53.

|

|

—

|

assist the Member States in improving the hotspot approach, especially with regard to hotspot capacity, the treatment of unaccompanied minors, the deployment of experts, and roles and responsibilities in the hotspot approach;

|

|

|

|

—

|

evaluate and further develop the hotspot approach, with a view to optimising EU assistance for migration management.

|

|

|

| (iii) Special report No 11/2017 — The Bêkou Trust Fund

|

|

|

3.54.

|

In this special report we concluded that, despite some shortcomings, both the decision to set up the Bêkou trust fund and the design of the fund were appropriate, considering the circumstances. We found that the management of the fund had not yet reached its full potential in three respects: coordination amongst stakeholders; the transparency, speed and cost-effectiveness of procedures; and monitoring and evaluation mechanisms.

|

|

|

3.54.

|

The Bêkou trust fund has opened a new way to coordinate actions conducted by the EU and its Member States which has not been fully taken advantage of at this stage.

In the Commission’s view, when taking into account the full length of the project cycle, the overall speed of Bêkou is higher than that of other EU instruments under crisis situation. However, the Commission agrees that it will explore ways to increase further the speed of the selection procedures beyond what the internal rules currently allow whilst striking the right balance between speed and transparency.

The monitoring and evaluation mechanisms are developed at project level and will be gradually upgraded at fund level.

|

|

|

3.55.

|

Overall, the Bêkou trust fund had made a positive contribution by the time of the audit. It had attracted aid, but few additional donors, and most of its projects had delivered their expected outputs. The fund had provided enhanced visibility to the EU.

|

|

|

|

3.56.

|

We recommended that the Commission should:

|

|

3.56.

|

|

—

|

develop further guidance on choosing instruments through which to provide aid, and on carrying out needs analyses with a view to deciding the scope of a trust fund’s interventions; and

|

|

|

—

|

The Commission accepted the recommendation which will be implemented as follows:

The Commission has developed the trust fund guidelines which include a section on the conditions to establish a trust fund.

The Commission is ready to revisit the scope of these guidelines to include a more detailed description of the criteria laid out in the Financial Regulation to evaluate the conditions to establish EU trust funds.

In this regard the Commission considers that by assessing the conditions for the establishment of a EUTF, the question of the comparative advantages of other aid vehicles will be addressed.

The Commission considers that the guidelines cannot be too prescriptive particularly in what concerns emergency trust funds.

|

|

|

—

|

improve donor coordination, selection procedures and performance measurement, and optimise administrative costs.

|

|

|

—

|

The Commission accepted this recommendation but highlighted that other actors have a role to play in its follow-up.

The Bêkou trust fund already coordinates its activities with other relevant donors and actors. The Commission nevertheless agrees that coordination could be better formalized and that coordination opportunities should be taken advantage of by all participants in the BTF.

The Commission applies its standard rules and procedures as well as the internal rules that allow the EUTF Managers to derogate from these standard rules in certain conditions (the internal guidelines on crisis and the EUTF guidelines). For example the guidelines on crisis situations recognize constraints and limitations to contract and implement projects in a crisis situation, allowing the use of ‘flexible procedures’ when a crisis situation has been declared in the country.

|

|

| (iv) Special report No 22/2017 — Election Observation Missions

|

|

|

3.57.

|

In this special report, we found that the European External Action Service and the Commission had made reasonable efforts to support the implementation of the EU Election Observation Missions recommendations and had used the tools at their disposal to this end. We concluded that the presentation of EU Election Observation Missions recommendations had improved in recent years, but more consultation was needed on the ground. The European External Action Service and the Commission had engaged in political dialogue and provided electoral assistance to support the implementation of the recommendations, but electoral follow-up missions had not been conducted as often as they might have been. Lastly, there was no central overview of the recommendations, nor had a systematic assessment been made of their implementation status.

|

|

|

|

3.58.

|

We recommended that the European External Action Service should:

|

|

3.58.

|

|

—

|

systematically consult stakeholders on EU Election Observation Missions recommendations before they are adopted;

|

|

|

—

|

Stakeholders will be systematically consulted on the general content of the recommendations (not on the specific drafting of recommendations so as not to impinge on the independence of the report).

|

|

|

—

|

conduct follow-up missions more often;

|

|

|

—

|

The EEAS and the Commission are committed to strengthen the follow-up to the EU EOMs’ recommendations through a combination of tools ranging from EFMs, to electoral assistance, political dialogue, among others.

|

|

|

—

|

gain a central overview of the EU Election Observation Missions recommendations and systematically assess their implementation status.

|

|

|

—

|

The Commission will seek to provide the financial means to set up a centralised depository for storing EU EOM recommendations.

|

|

|

Heading 5 ‘Administration’ and reports on the ‘Functioning Single Market and sustainable Monetary Union’

|

|

|

3.59.

|

In the priority area ‘Functioning Single Market and Sustainable Monetary Union’, we produced four special reports in 2017 (50).

|

|

|

|

3.60.

|

We wish to draw attention to a number of key conclusions and recommendations for two of these reports.

|

|

|

| (i) Special report No 17/2017 — ‘The Commission’s intervention in the Greek financial crisis’

|

|

|

3.61.

|

In this special report, we concluded that the economic adjustment programmes agreed for Greece in the wake of the financial crisis had provided short-term financial stability, and made some progress on reform possible. But the programmes had only helped Greece to recover to a limited extent. As of mid-2017, they had not succeeded in restoring the country’s ability to finance its needs on the markets.

|

|

|

|

3.62.

|

We were unable to report on the European Central Bank’s role, as it questioned our mandate and failed to provide us with sufficient audit evidence.

|

|

|

|

3.63.

|

We recommended that the Commission should:

|

|

3.63.

|

|

—

|

better prioritise the conditions and specify measures urgently needed to address imbalances;

|

|

|

—

|

The Commission accepted the recommendation.

Policy actions were duly prioritised, notably through the joint programme with the IMF. The Commission, inter alia, used the IMF's well known system of ‘prior actions’ and ‘structural benchmarks’, which are critical reforms needed to close a review and release a disbursement. These were gradually refined with some additional prior actions in the area of structural reforms, and through the use of milestones. The ESM stability support programme currently underway also introduced the concept of ‘key deliverables’.

|

|

|

—

|

ensure that programmes are embedded in an overall growth strategy for the country;

|

|

|

—

|

The Commission accepted the recommendation.

The Commission notes that the current ESM Treaty provides for more focused programmes, e.g. targeted at imbalances in specific sectors, in which case a comprehensive growth strategy may not be warranted.

|

|

|

—

|

seek to reach an agreement with programme partners;

|

|

|

—

|

The Commission accepted the recommendation and recalled that it cannot commit other institutions to accept working modalities that, by definition, need to be jointly agreed both in principle and in substance.

|

|

|

—

|

be more systematic in assessing the administrative capacity of the Member State to implement the reforms;

|

|

|

—

|

The Commission accepted the recommendation.

Under the ESM stability support programme, particular attention is being paid to the implementation of reforms to increase the quality and efficiency of the public sector in the delivery of essential public goods and services (4th pillar). Technical support has been closely aligned with the provisions of the ESM stability programme, whereby support to a number of reforms under the programme has been explicitly included in the Memorandum of Understanding of August 2015 and the subsequent Supplemental MoUs. Within three months after the ESM programme was established, the Commission agreed with the Greek authorities a ‘Plan for technical cooperation in support of structural reforms’ that was also published on the Commission's website. The Structural Reform Support Service provides and coordinates support to the Greek authorities in almost all reform areas under the ESM programme.

|

|

|

—

|

carry out interim evaluations for successive programmes and use the results to assess their design and monitoring arrangements.

|

|

|

—

|

The Commission accepted the recommendation. It has already carried out ex-post evaluations for other Euro area countries which had stability support programmes.

|

|

| (ii) Special report No 23/2017 — Single Resolution Board

|

|

|

3.64.

|

Our overall conclusion in this special report was that, at the relatively early stage when we conducted the audit, there were shortcomings in the Single Resolution Board’s preparation for its tasks. We recognised that these shortcomings needed to be seen in context: the Single Resolution Board had been set up from scratch in a very short period of time.

|

|

|

|

THE COURT’S OBSERVATIONS

|

|

|

3.65.

|

The shortcomings included:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

—

|

incomplete resolution planning for the banks within the Single Resolution Board’s remit, and an incomplete system of rules governing it;

|

|

|

|

—

|

missing assessments of the feasibility and credibility of the selected resolution strategies in the resolution plans;

|

|

|

|

—

|

an unclear distribution of operational tasks between National Resolution Authorities and the Single Resolution Board;

|

|

|

|

—

|

an imbalance between the mandates of the Single Resolution Board and the European Central Bank.

|

|

|

|

3.66.

|

We concluded that a number of steps were needed to improve the system. We recommended that the Single Resolution Board should:

|

|

|

|

—

|

complete its resolution planning for the banks and finalise its system of rules governing those plans;

|

|

|

|

—

|

accelerate its recruitment efforts, and staff its human resources department appropriately;

|

|

|

|

—

|

clarify the operational distribution of tasks and responsibilities with National Resolution Authorities; and

|

|

|

|

—

|

engage with the European Central Bank to ensure it received all necessary information, and invite the legislator to take the necessary action to put the current framework into practice.

|

|

|

|

3.67.

|

We also published special report No 14/2017, a ‘Performance review of case management at the Court of Justice of the EU’. This special report included considerations for further improvement by the Court of Justice of case management.

|

|

|

|

THE COURT’S OBSERVATIONS

|

THE COMMISSION’S REPLIES

|

|

PART 3 — FOLLOW-UP OF RECOMMENDATIONS

|

|

|

3.68.

|

This part contains the results of our yearly review of the extent to which the Commission has taken corrective action related to our recommendations. The follow-up of recommendations we make in our special reports is an important step in the performance audit cycle. As well as providing us and our stakeholders with feedback on the impact of our work, the follow-up of recommendations helps to encourage the Commission and Member States to implement our recommendations.

|

|

|

|

A. Scope and approach — a new method

|

|

|

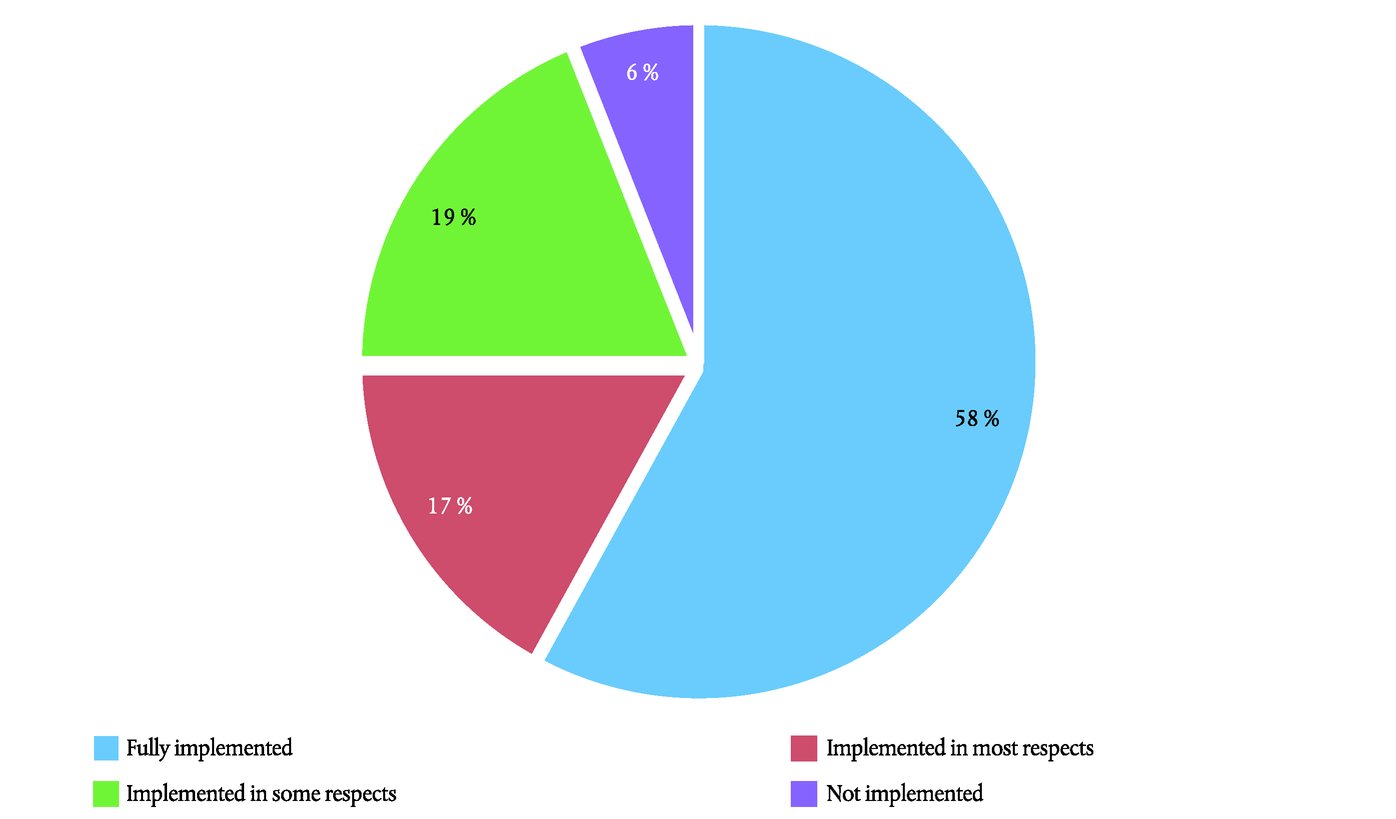

3.69.

|