|

26.7.2016 |

EN |

Official Journal of the European Union |

C 272/1 |

COMMISSION NOTICE

The ‘Blue Guide’ on the implementation of EU products rules 2016

(Text with EEA relevance)

(2016/C 272/01)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PREFACE

IMPORTANT NOTICE

|

1. |

REGULATING THE FREE MOVEMENT OF GOODS | 5 |

|

1.1. |

A historical perspective | 5 |

|

1.1.1. |

The ‘Old Approach’ | 6 |

|

1.1.2. |

Mutual Recognition | 7 |

|

1.1.3. |

The ‘New Approach’ and the ‘Global Approach’ | 7 |

|

1.2. |

The ‘New Legislative Framework’ | 9 |

|

1.2.1. |

The concept | 9 |

|

1.2.2. |

The legal nature of the NLF acts and their relationship to other EU legislation | 10 |

|

1.2.3. |

How the system fits together | 11 |

|

1.3. |

The General Product Safety Directive | 12 |

|

1.4. |

The legislation on product liability | 12 |

|

1.5. |

Scope of the Guide | 13 |

|

2. |

WHEN DOES UNION HARMONISATION LEGISLATION ON PRODUCTS APPLY? | 15 |

|

2.1. |

Product coverage | 15 |

|

2.2. |

Making available on the market | 17 |

|

2.3. |

Placing on the market | 18 |

|

2.4. |

Products imported from countries outside the EU | 20 |

|

2.5. |

Putting into service or use (and installation) | 21 |

|

2.6. |

Simultaneous application of Union harmonisation acts | 22 |

|

2.7. |

Intended use/misuse | 23 |

|

2.8. |

Geographical application (EEA EFTA states, Overseas Countries and Territories (OCTs), Turkey) | 24 |

|

2.8.1. |

Member States and Overseas countries and territories | 24 |

|

2.8.2. |

EEA EFTA states | 25 |

|

2.8.3. |

Monaco, San Marino and Andorra | 25 |

|

2.8.4. |

Turkey | 26 |

|

2.9. |

Transitional periods in the case of new or revised EU rules | 27 |

|

2.10. |

Transitional arrangements for the EU declaration of conformity as a result of the alignment to Decision No 768/2008/EC | 27 |

|

3. |

THE ACTORS IN THE PRODUCT SUPPLY CHAIN AND THEIR OBLIGATIONS | 28 |

|

3.1. |

Manufacturer | 28 |

|

3.2. |

Authorised representative | 32 |

|

3.3. |

Importer | 33 |

|

3.4. |

Distributor | 34 |

|

3.5. |

Other intermediaries: Intermediary service providers under the E-commerce Directive | 37 |

|

3.6. |

End-user | 38 |

|

4. |

PRODUCT REQUIREMENTS | 39 |

|

4.1. |

Essential product requirements | 39 |

|

4.1.1. |

Definition of essential requirements | 39 |

|

4.1.2. |

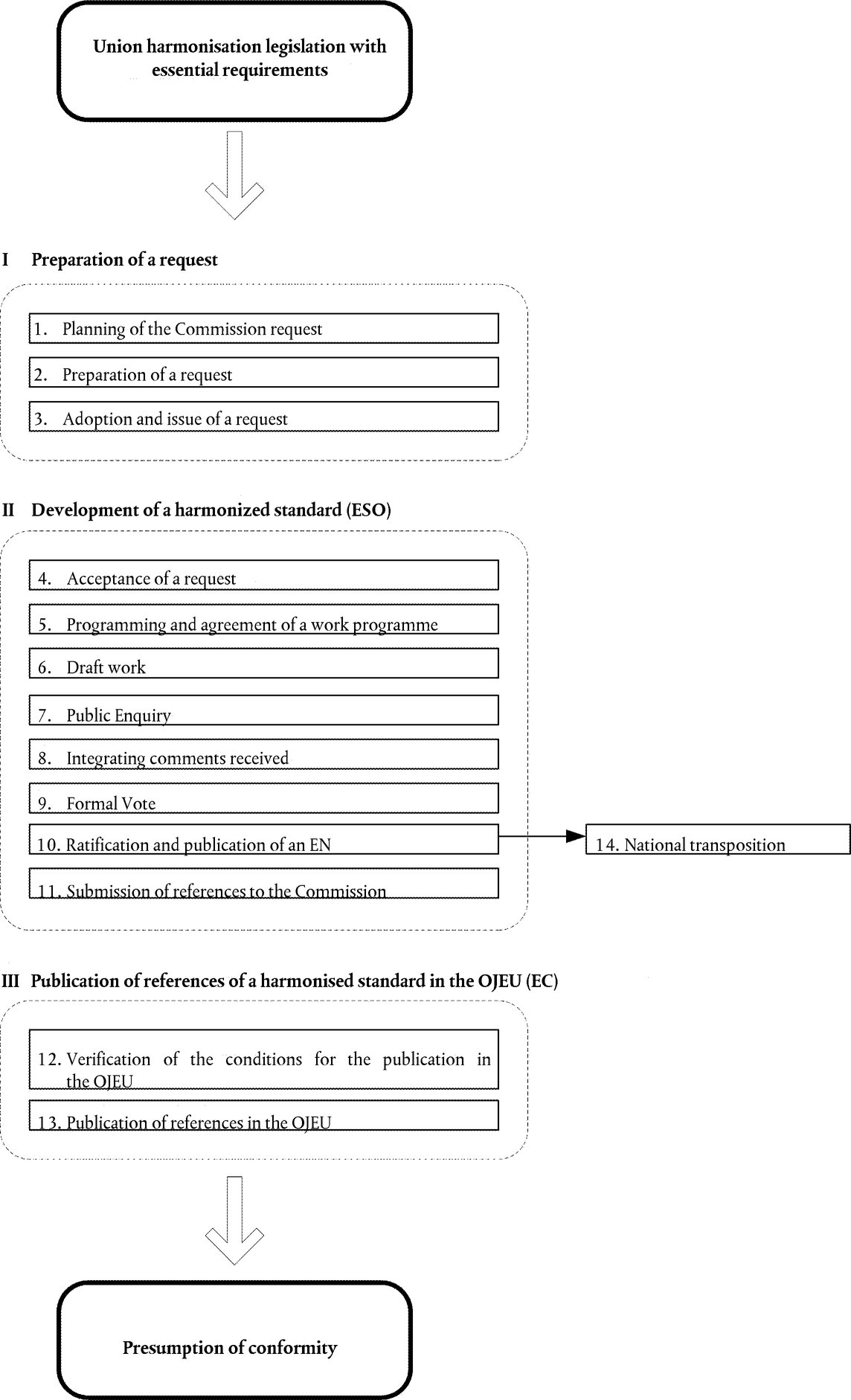

Conformity with the essential requirements: harmonised standards | 40 |

|

4.1.3. |

Conformity with the essential requirements: other possibilities | 51 |

|

4.2. |

Traceability requirements | 51 |

|

4.2.1. |

Why does Traceability matter? | 52 |

|

4.2.2. |

Traceability provisions | 52 |

|

4.3. |

Technical documentation | 56 |

|

4.4. |

EU declaration of conformity | 57 |

|

4.5. |

Marking requirements | 58 |

|

4.5.1. |

CE marking | 58 |

|

4.5.2. |

Other mandatory markings | 64 |

|

5. |

CONFORMITY ASSESSMENT | 65 |

|

5.1. |

Modules for conformity assessment | 65 |

|

5.1.1. |

What is a conformity assessment? | 65 |

|

5.1.2. |

The modular structure of conformity assessment in Union harmonisation legislation | 65 |

|

5.1.3. |

Actors in conformity assessment — Positioning of conformity assessment in the supply chain | 66 |

|

5.1.4. |

Modules and their variants | 69 |

|

5.1.5. |

One- and two-module procedures — Procedures based on type (EU-type examination) | 69 |

|

5.1.6. |

Modules based on quality assurance | 70 |

|

5.1.7. |

Overview of modules | 70 |

|

5.1.8. |

Overview of procedures | 73 |

|

5.1.9. |

Rationale for selecting the appropriate modules | 74 |

|

5.2. |

Conformity assessment bodies | 75 |

|

5.2.1. |

Conformity assessment bodies and notified bodies | 75 |

|

5.2.2. |

Roles and responsibilities | 76 |

|

5.2.3. |

Competence of Notified bodies | 78 |

|

5.2.4. |

Coordination between notified bodies | 79 |

|

5.2.5. |

Subcontracting by notified bodies | 79 |

|

5.2.6. |

Accredited in-house bodies | 81 |

|

5.3. |

Notification | 81 |

|

5.3.1. |

Notifying authorities | 81 |

|

5.3.2. |

Notification process | 82 |

|

5.3.3. |

Publication by the commission — the NANDO website | 85 |

|

5.3.4. |

Monitoring of the competence of notified bodies — Suspension — withdrawal — appeal | 86 |

|

6. |

ACCREDITATION | 87 |

|

6.1. |

Why accreditation? | 87 |

|

6.2. |

What is accreditation? | 88 |

|

6.3. |

Scope of Accreditation | 89 |

|

6.4. |

Accreditation according to Regulation (EC) No 765/2008 | 89 |

|

6.4.1. |

National accreditation bodies | 90 |

|

6.4.2. |

Non-competition and non-commerciality of national accreditation bodies | 91 |

|

6.5. |

The European accreditation infrastructure | 92 |

|

6.5.1. |

Sectoral accreditation schemes | 92 |

|

6.5.2. |

Peer evaluation | 92 |

|

6.5.3. |

Presumption of conformity for national accreditation bodies | 93 |

|

6.5.4. |

EA's role in supporting and harmonising accreditation practice across Europe | 93 |

|

6.6. |

Cross-border accreditation | 93 |

|

6.7. |

Accreditation in the international context | 95 |

|

6.7.1. |

Cooperation between accreditation bodies | 95 |

|

6.7.2. |

The impact on trade relations in the field of conformity assessment between the EU and Third Countries | 96 |

|

7. |

MARKET SURVEILLANCE | 97 |

|

7.1. |

Why do we need market surveillance? | 98 |

|

7.2. |

controls by Market Surveillance authorities | 99 |

|

7.3. |

Control of products from third countries by customs | 101 |

|

7.4. |

Member States responsibilities | 103 |

|

7.4.1. |

National infrastructures | 103 |

|

7.4.2. |

National Market Surveillance Programmes (NMSP) and reviews of activities | 104 |

|

7.4.3. |

Public information | 105 |

|

7.4.4. |

Market surveillance procedures | 105 |

|

7.4.5. |

Corrective measures — bans — withdrawals — recalls | 107 |

|

7.4.6. |

Sanctions | 108 |

|

7.5. |

Cooperation between the Member States and the European commission | 108 |

|

7.5.1. |

safeguard mechanisms | 109 |

|

7.5.2. |

The application of safeguard mechanisms step by step | 110 |

|

7.5.3. |

Mutual assistance, administrative cooperation and exchange of information among Member States | 112 |

|

7.5.4. |

Rapid Alert System for non-food products presenting a risk | 114 |

|

7.5.5. |

ICSMS | 115 |

|

7.5.6. |

Medical devices: vigilance system | 117 |

|

8. |

FREE MOVEMENT OF PRODUCTS WITHIN THE EU | 117 |

|

8.1. |

Free movement clause | 117 |

|

8.2. |

Limits and restrictions | 118 |

|

9. |

INTERNATIONAL ASPECTS OF THE EU LEGISLATION ON PRODUCTS | 118 |

|

9.1. |

Agreements on Conformity Assessment and Acceptance (ACAAs) | 118 |

|

9.2. |

Mutual recognition agreements (MRAs) | 119 |

|

9.2.1. |

Main characteristics | 119 |

|

9.2.2. |

EU-Swiss MRA | 120 |

|

9.2.3. |

EEA EFTA States: Mutual recognition agreements and Agreements on Conformity Assessment and Acceptance | 121 |

ANNEXES

|

ANNEX I — |

EU legislation referred to in the Guide (non-exhaustive list) | 122 |

|

ANNEX II — |

Additional guidance documents | 127 |

|

ANNEX III — |

Useful Web addresses | 129 |

|

ANNEX IV — |

Conformity assessment procedures (modules from Decision No 768/2008/EC) | 130 |

|

ANNEX V — |

Relation between ISO 9001 and modules requiring a quality assurance system | 140 |

|

ANNEX VI — |

Using harmonised standards to assess the competence of Conformity Assessment Bodies | 142 |

|

ANNEX VII — |

Frequently Asked Questions on CE marking | 147 |

PREFACE

The Guide to the implementation of directives based on the New Approach and the Global Approach (the ‘Blue Guide’) was published in 2000. Since then, it has become one of the main reference documents explaining how to implement the legislation based on the New Approach, now covered by the New Legislative Framework.

Much of the 2000 edition of the ‘Blue Guide’ is still valid but it requires updating to cover new developments and to ensure the broadest possible common understanding on implementation of the New Legislative Framework (NLF) for the marketing of products. It is also necessary to take account of the changes introduced by the Lisbon Treaty (in force since 1 December 2009) with regard to the legal references and terminology applicable to EU-related documents, procedures, etc.

This new version of the Guide will therefore build on the past edition, but include new chapters, for example on the obligations of economic operators or accreditation, or completely revised chapters such as those on standardisation or market surveillance. The Guide has also been given a new title reflecting the fact that the New Legislative Framework is likely to be used, at least in part, by all types of Union harmonisation legislation and not only by the so-called ‘New Approach’ directives.

IMPORTANT NOTICE

This Guide is intended to contribute to a better understanding of EU product rules and to their more uniform and coherent application across different sectors and throughout the single market. It is addressed to the Member States and others who need to be informed of the provisions designed to ensure the free circulation of products as well as a high level of protection throughout the Union (e.g. trade and consumer associations, standardisation bodies, manufacturers, importers, distributors, conformity assessment bodies and trade unions).

This is intended purely as a guidance document — only the text of the Union harmonisation act itself has legal force. In certain cases, there may be differences between the provisions of a Union harmonisation act and the contents of this Guide, in particular where slightly divergent provisions in the individual Union harmonisation act cannot be fully described in this Guide. The binding interpretation of EU legislation is the exclusive competence of the Court of Justice of the European Union. The views expressed in this Guide cannot prejudge the position that the Commission might take before the Court of Justice. Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use which might be made of the following information.

This Guide applies to the EU Member States but also to Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway as signatories of the Agreement on the European Economic Area (EEA), as well as Turkey in certain cases. References to the Union or the single market are, accordingly, to be understood as referring to the EEA, or to the EEA market.

As this Guide reflects the state of the art at the time of its drafting, the guidance offered may be subject to later modification (1). In particular, more specific reflections are ongoing regarding various aspects of the Union legal framework applicable to online sales and this Guide is without prejudice to any future specific interpretation and guidance which may be developed on those matters.

1. REGULATING THE FREE MOVEMENT OF GOODS

1.1. A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

The objectives of the first harmonisation directives focused on the elimination of barriers and on the free movement of goods in the single market. These objectives are now being complemented by a comprehensive policy geared to ensuring that only safe and otherwise compliant products find their way on to the market, in such a way that honest economic operators can benefit from a level playing field, thus promoting at the same time an effective protection of EU consumers and professional users and a competitive single EU market.

Policies and legislative techniques have evolved over the last 40 years of European integration, especially in the area of the free movement of goods, thereby contributing to the success of the Single Market today.

Historically, EU legislation for goods has progressed through four main phases:

|

— |

the traditional approach or ‘Old Approach’ with detailed texts containing all the necessary technical and administrative requirements, |

|

— |

the ‘New Approach’ developed in 1985, which restricted the content of legislation to ‘essential requirements’ leaving the technical details to European harmonised standards. This in turn led to the development of European standardisation policy to support this legislation, |

|

— |

the development of the conformity assessment instruments made necessary by the implementation of the various Union harmonisation acts, both New Approach and Old Approach, |

|

— |

the ‘New Legislative Framework’ (2) adopted in July 2008, which built on the New Approach and completed the overall legislative framework with all the necessary elements for effective conformity assessment, accreditation and market surveillance including the control of products from outside the Union. |

1.1.1. THE ‘OLD APPROACH’

The Old Approach reflected the traditional manner in which national authorities drew up technical legislation, going into great detail — usually motivated by a lack of confidence in the rigour of economic operators on issues of public health and safety. In certain sectors (e.g. legal metrology) this even led public authorities to deliver certificates of conformity themselves. The unanimity required in this field until 1986 made the adoption of such legislation very unwieldy and the continued recourse to this technique in a number of sectors is often justified for reasons of public policy (e.g. food legislation) or by international traditions and/or agreements which cannot be changed unilaterally (e.g. automobile legislation or food again).

The first attempt to break out of this situation came with the adoption of Directive 83/189/EEC (3) on 28 March 1983 setting up an information procedure between the Member States and the Commission to avoid the creation of new technical barriers to the free movement of goods which would take a long time to correct through the harmonisation process.

Under that Directive, Member States are obliged to notify draft national technical regulations to other Member States and the Commission (and national standardisation bodies (NSB) were obliged to notify draft national standards (4) to the Commission, to the European standardisation organisations (ESO) and to other national standardisation bodies). During a standstill period these technical regulations may not be adopted, leaving the Commission and the other Member States the possibility to react. In the absence of reactions within the initial standstill period of 3 months, the draft technical regulations may then be adopted. Otherwise, where objections are raised, a further 3 month standstill is imposed.

The standstill period is 12 months in the presence of a proposal for a Union harmonisation act in the area in question. However, the standstill period does not apply where a Member State is obliged to introduce technical regulations urgently to protect public health or safety, animals or plants.

1.1.2. MUTUAL RECOGNITION

Alongside legislative initiatives to prevent new barriers and promote the free movement of goods, the systematic application of the principle of mutual recognition enshrined in EU law was also pursued. National technical regulations are subject to the provisions of Articles 34 to 36 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), which prohibit quantitative restrictions or measures having equivalent effect. Case law of the European Court of Justice, especially case 120/78 (the ‘Cassis de Dijon’ case (5)), provides the key elements for mutual recognition. The effect of this case law is as follows.

|

— |

Products lawfully manufactured or marketed in one Member State should in principle move freely throughout the Union where such products meet equivalent levels of protection to those imposed by the Member State of destination. |

|

— |

In the absence of Union harmonisation legislation, Member States are free to legislate on their territory subject to the Treaty rules on free movement of goods (Arts 34-36 TFEU). |

|

— |

Barriers to free movement which result from differences in national legislation may only be accepted if national measures:

|

To help implement these principles, the European Parliament and the Council adopted, in the 2008 goods package, Regulation (EC) No 764/2008 of 9 July 2008 laying down procedures relating to the application of certain national technical rules to products lawfully marketed in another Member State and repealing Decision 3052/95/EC (6).

However, while contributing greatly to the free movement of goods within the single market, the mutual recognition principle cannot solve all the problems and there remains, even today as underlined by the comments of the Monti Report (7), room for further harmonisation.

1.1.3. THE ‘NEW APPROACH’ AND THE ‘GLOBAL APPROACH’

The Cassis de Dijon case is well known for its important role in promoting the mutual recognition principle but it also played an immense role in modifying the EU approach to technical harmonisation on three fundamental counts:

|

— |

in stating that Member States could only justify forbidding or restricting the marketing of products from other Member States on the basis of non-conformity with ‘essential requirements’, the Court opened a reflection on the content of future harmonisation legislation: since non-respect of non-essential requirements could not justify restricting the marketing of a product, such non-essential requirements need no longer figure in EU harmonisation texts. This opened the door to the New Approach and the consequent reflection on what constitutes an essential requirement and how to formulate it in such a manner that conformity can be demonstrated, |

|

— |

in stating this principle, the Court clearly placed the onus on national authorities to demonstrate where products did not conform to essential requirements but it also begged the question of the appropriate means for demonstrating conformity in a proportionate manner, |

|

— |

by noting that Member States were obliged to accept products from other Member States except in circumscribed conditions, the Court identified a legal principle but did not produce the means to create the trust in the products that could help authorities to accept products they could not vouch for. This led to the need to develop a policy on conformity assessment. |

The New Approach legislative technique approved by the Council of Ministers on 7 May 1985 in its Resolution on a new approach to technical harmonisation and standards (8) was the logical legislative follow up to the Cassis de Dijon case. This regulatory technique established the following principles:

|

— |

legislative harmonisation should be limited to the essential requirements (preferably performance or functional requirements) that products placed on the EU market must meet if they are to benefit from free movement within the EU, |

|

— |

the technical specifications for products meeting the essential requirements set out in legislation should be laid down in harmonised standards which can be applied alongside the legislation, |

|

— |

products manufactured in compliance with harmonised standards benefit from a presumption of conformity with the corresponding essential requirements of the applicable legislation, and, in some cases, the manufacturer may benefit from a simplified conformity assessment procedure (in many instances the manufacturer's declaration of conformity, made more easily acceptable to public authorities by the existence of the product liability legislation (9)), |

|

— |

the application of harmonised or other standards remains voluntary, and the manufacturer can always apply other technical specifications to meet the requirements (but will carry the burden of demonstrating that these technical specifications answer the needs of the essential requirements, more often than not, through a process involving a third party conformity assessment body). |

The operation of Union harmonisation legislation under the New Approach requires harmonised standards to offer a guaranteed level of protection with regard to the essential requirements established by the legislation. This constitutes one of the major preoccupations of the Commission in pursuit of its policy for a strong European standardisation process and infrastructure. Regulation (EU) No 1025/2012 on European Standardisation (10) gives the Commission the possibility of inviting, after consultation with the Member States, the European standardisation organisations to draw up harmonised standards and it establishes procedures to assess and to object to harmonised standards.

Since the New Approach calls for common essential requirements to be made mandatory by legislation, this approach is appropriate only where it is possible to distinguish between essential requirements and technical specifications. Further, as the scope of such legislation is risk-related, the wide range of products covered has to be sufficiently homogeneous for common essential requirements to be applicable. The product area or hazards also have to be suitable for standardisation.

The principles of the New Approach laid the foundation for European standardisation in support of Union harmonisation legislation. The role of harmonised standards and the responsibilities of the European standardisation organisations are now defined in Regulation (EU) No 1025/2012 together with relevant Union harmonisation legislation.

The principle of reliance on standards in technical regulations has also been adopted by the World Trade Organisation (WTO). In its Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) it promotes the use of international standards (11).

The negotiation of the first Union harmonisation texts under the New Approach immediately highlighted the fact that the determination of essential requirements and the development of harmonised standards were not sufficient to create the necessary level of trust between Member States and that an appropriate horizontal conformity assessment policy and instruments had to be developed. This was done in parallel to the adoption of the directives (12).

Hence in 1989 and 1990 the Council adopted a Resolution on the Global Approach and Decision 90/683/EEC (updated and replaced by Decision 93/465/EEC) (13) laying down the general guidelines and detailed procedures for conformity assessment. These have now been repealed and updated by Decision No 768/2008/EC of 9 July 2008 on a common framework for the marketing of products (14).

The major thrust of these policy instruments was to develop common tools for conformity assessment across the board (for both regulated and non-regulated areas).

The policy on product standards was first developed to ensure that the standards set technical specifications to which conformity could be demonstrated. However, at the request of the Commission, CEN and Cenelec adopted the EN 45000 series of standards for the determination of the competence of third parties involved with conformity assessment. This series has since become the EN ISO/IEC 17000 harmonised series of standards. Under the New Approach directives a mechanism was set up whereby national authorities notified the third parties they designated to carry out conformity assessments based on recourse to these standards.

On the basis of ISO/IEC documentation, the Council in its Decisions developed consolidated conformity assessment procedures and the rules for their selection and use in directives (the modules). The modules are set out in a manner to favour their selection from the lightest (‘internal control of production’) for simple products or products not necessarily presenting serious risks, moving to the most comprehensive (full quality assurance with EU-design examination), where the risks are more severe or the products/technologies more complex. In order to face up to modern manufacturing processes, the modules foresee both product conformity assessment processes and quality management assessment, leaving the legislator to decide which are the most appropriate in each sector, as it is not necessarily effective to provide for individual certification for each mass produced product, for example. To reinforce the transparency of the modules and their effectiveness, at the request of the Commission, the ISO 9001 series of standards on quality assurance were harmonised at the European level and integrated into the modules. Thus, economic operators who use these tools in their voluntary quality management policies to reinforce their quality image on the market, can benefit from the use of the same tools in the regulated sectors.

These different initiatives were all geared to directly reinforcing the assessment of conformity of products prior to their marketing. Alongside these, the Commission, in close cooperation with the Member States and the national accreditation bodies, developed European cooperation in the field of accreditation in order to constitute a last level of control and reinforce the credibility of the third parties involved in carrying out product and quality assurance conformity assessment. This remained a political, rather than a legislative initiative, but it was nevertheless effective in creating the first European infrastructure in this area, and in placing European players very much in the lead in this field at international level.

These developments led to some 27 directives being adopted on the basis of New Approach elements. They are far fewer in number than traditional directives in the field of industrial products (some 700), but their wide hazard-based scope means that entire industrial sectors have benefited from free movement through this legislative technique.

1.2. THE ‘NEW LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK’

1.2.1. THE CONCEPT

Towards the end of the 90s the Commission started to reflect on the effective implementation of the New Approach. In 2002, a wide consultation process was launched and on 7 May 2003 the Commission adopted a Communication to the Council and European Parliament suggesting a possible revision of certain New Approach elements. This in turn led to the Council Resolution of 10 November 2003 on the Communication of the European Commission ‘Enhancing the implementation of the New Approach Directives’ (15).

The consensus on the need for the update and review was clear and strong. The major elements needing attention were also clear: overall coherence and consistency, the notification process, accreditation, the conformity assessment procedures (modules), CE marking and market surveillance (including revision of the safeguard clause procedures).

A Regulation and a Decision constituting part of the ‘Ayral goods package’ (16) were adopted by the European Parliament and the Council on 9 July 2008 (17).

Regulation (EC) No 765/2008 and Decision No 768/2008/EC brought together, in the New Legislative Framework (NLF), all the elements required for a comprehensive regulatory framework to operate effectively for the safety and compliance of industrial products with the requirements adopted to protect the various public interests and for the proper functioning of the single market.

Regulation (EC) No 765/2008 established the legal basis for accreditation and market surveillance and consolidated the meaning of the CE marking, thus filling an existing void. Decision No 768/2008/EC updated, harmonised and consolidated the various technical instruments already used in existing Union harmonisation legislation (not only in New Approach directives): definitions, criteria for the designation and notification of conformity assessment bodies, rules for the notification process, the conformity assessment procedures (modules) and the rules for their use, the safeguard mechanisms, the responsibilities of the economic operators and traceability requirements.

The NLF takes account of the existence of all the economic operators in the supply chain — manufacturers, authorised representatives, distributors and importers — and of their respective roles in relation to the product. The importer now has clear obligations in relation to the compliance of products, and where a distributor or an importer modifies a product or markets it under their own name, they become the equivalent of the manufacturer and must take on the latter's responsibilities in relation to the product.

The NLF also recognises the different facets of the responsibilities of the national authorities: the regulatory authorities, the notification authorities, those which oversee the national accreditation body, the market surveillance authorities, the authorities responsible for the control of products from third countries, etc., underlining that responsibilities depend on the activities carried out.

The NLF has changed the emphasis of EU legislation in relation to market access. Formerly the language of Union harmonisation legislation concentrated on the notion of ‘placing on the market’ which is traditional free movement of goods language, i.e. it focuses on the first making available of a product on the EU market. The NLF, recognising the existence of a single internal market, puts the emphasis on making a product available thus giving more importance to what happens after a product is first made available. This also corresponds to the logic of the putting into place of EU market surveillance provisions. The introduction of the concept of making available facilitates the tracing back of a non-compliant product to the manufacturer. It is important to note that compliance is assessed with regard to the legal requirements applicable at the time of the first making available.

The most important change brought about by the NLF to the legislative environment of the EU was the introduction of a comprehensive policy on market surveillance. This has considerably changed the balance of EU legislative provisions from being fundamentally oriented at setting product related requirements to be met when products are placed on the market to an equal emphasis on enforcement aspects during the whole life-cycle of products.

1.2.2. THE LEGAL NATURE OF THE NLF ACTS AND THEIR RELATIONSHIP TO OTHER EU LEGISLATION

1.2.2.1. Regulation (EC) No 765/2008

Regulation (EC) No 765/2008 imposes clear obligations on Member States who do not have to transpose its provisions (although many may have to take national measures to adapt their national legal framework). Its provisions are directly applicable to the Member States, to all the economic operators concerned (manufacturers, distributors, importers) and to conformity assessment bodies and accreditation bodies. Economic operators now have not only obligations but direct rights that they can enforce through the national courts against both national authorities and other economic operators for non-respect of the provisions of the Regulation.

In the presence of other EU legislation, the Regulation applies first and foremost, (a) on the basis of being directly applicable, i.e. national authorities and economic operators must apply the provisions of the Regulation as such (most of the other legislation is contained in directives) and (b) on the basis of the lex specialis rule, i.e. whenever a matter is regulated by two rules, the more specific one should be applied first.

In the absence of more specific legislation on the issues covered by its provisions, Regulation (EC) No 765/2008 will apply at the same time, with, and as a complement to, existing legislation. Where existing legislation contains similar provisions as the Regulation, the corresponding provisions will have to be examined on a one to one basis to determine which is the most specific.

In general terms, relatively few EU legislative texts contain provisions relating to accreditation, so it can be said that Regulation (EC) No 765/2008 is of general application in this area. In the area of market surveillance (including the control of products from third countries) the situation is more complex, as some Union harmonisation legislation does have various provisions relating to the issues covered by the Regulation (e.g. pharmaceuticals and medical devices legislation which provides for a specific information procedure).

1.2.2.2. Decision No 768/2008/EC

Decision No 768/2008/EC is what is referred to as a sui generis decision, meaning that it has no addressees and therefore is neither directly nor indirectly applicable. It constitutes a political commitment on the part of the three EU institutions, European Parliament, Council and Commission.

This means that for its provisions to apply in Union law, they have to be either referred to expressis verbis (expressly) in future legislation or integrated into it.

The three institutions have indeed committed themselves to adhere to and to have recourse as systematically as possible to its provisions when drawing up product related legislation. Thus, relevant future proposals are to be examined in the light of the Decision and departures from its contents, duly justified.

1.2.3. HOW THE SYSTEM FITS TOGETHER

The evolution of EU legislative techniques in this area has been progressive, tackling issues one after another, although sometimes in parallel, culminating in the adoption of the New Legislative Framework: essential or other legal requirements, product standards, standards and rules for the competence of conformity assessment bodies as well as for accreditation, standards for quality management, conformity assessment procedures, CE marking, accreditation policy, and lately market surveillance policy including the control of products from third countries.

The New Legislative Framework now constitutes a complete system bringing together all the different elements that need to be dealt with in product safety legislation in a coherent, comprehensive legislative instrument that can be used across the board in all industrial sectors, and even beyond (environmental and health policies also have recourse to a number of these elements), whenever EU legislation is required.

In this system, the legislation has to set the levels of public protection objectives of the products concerned as well as the basic safety characteristics, it should set the obligations and requirements for economic operators, it has to set-where necessary-the level of competence of the third party conformity assessment bodies who assess products or quality management systems, as well as the control mechanisms for these bodies (notification and accreditation), it must determine which are the appropriate conformity assessment processes (modules which also include the manufacturer's declaration of conformity) to be applied, and finally it must impose the appropriate market surveillance mechanisms (internal and external) to ensure that the whole legislative instrument operates in an effective and seamless manner.

All these different elements are interlinked, operate together and are complementary, forming an EU quality (18) chain. The quality of the product depends on the quality of the manufacturing, which in many instances is influenced by the quality of testing, internal or carried out by external bodies, which depends on the quality of the conformity assessment processes, which depends on the quality of the bodies which in turn depends on the quality of their controls, which depends on the quality of notification or accreditation; the entire system depending on the quality of market surveillance and controls of products from third countries.

They should all be treated in one way or another in any piece of EU product safety legislation. If one element goes missing or is weak, the strength and effectiveness of the entire ‘quality chain’ is at stake.

1.3. THE GENERAL PRODUCT SAFETY DIRECTIVE

Directive 2001/95/EC (19) on general product safety (GPSD) is intended to ensure a high level of product safety throughout the EU for consumer products that are not covered by sector-specific EU harmonisation legislation. The GPSD also complements the provisions of sector legislation in some aspects. The key provision of the GPSD is that producers are obliged to place on the market only products which are safe (20). The GPSD also provides for market surveillance provisions aimed at guaranteeing a high level of consumer health and safety protection.

The GPSD has set up the Rapid Alert System which is used for dangerous non-food products (RAPEX, Rapid Alert System) between Member States and the Commission. The Rapid Alert System ensures that the relevant authorities are rapidly informed of dangerous products. Subject to certain conditions, Rapid Alert System notifications can also be exchanged with non-EU countries. In the case of serious product risks to the health and safety of consumers in various Member States, the GPSD provides for the possibility for the Commission to take temporary Decisions on Union-wide measures, so-called ‘emergency measures’. Under certain conditions, the Commission may adopt a formal Decision (valid for 1 year, but renewable for the same period) requiring the Member States to restrict or prevent the marketing of a product posing a serious risk to the health and safety of consumers. The Rapid Alert System has been subsequently extended by Regulation (EC) No 765/2008 to apply to all harmonised industrial products irrespective of the final user (i.e. professional products) and to products posing risks to other protected interests than health and safety, for example risks to the environment.

1.4. THE LEGISLATION ON PRODUCT LIABILITY

The concept of manufacturer according to Union harmonisation legislation as shaped by the New Legislative Framework is different from that under the Directive on consumer product liability 85/374/EEC (21). In the latter case, the concept of ‘producer’ (22) covers more and different persons than the concept of ‘manufacturer’ under the New Legislative Framework.

Legal or administrative action may take place against any person in the supply or distribution chain who can be considered responsible for a non-compliant product. This may, in particular, be the case when the producer is established outside the Union. The Directive on product liability covers all movables (23) and electricity, as well as raw materials and components of final products. Services as such are currently excluded from the scope. Secondly, the Directive applies only to defective products, i.e. products not providing the safety that a person is entitled to expect. The fact that a product is not fit for the use expected is not enough. The Directive only applies if a product lacks safety. The fact that a better product is made afterwards does not render older models defective.

Liability, the responsibility to pay for damages, is placed on the producer. A producer is either a manufacturer of a finished product or a component part of a finished product, producer of any raw material, or any person who presents himself as a manufacturer (for example by affixing a trademark). Importers placing products on the Union market from third countries are all considered to be producers under the Directive on product liability. If the producer cannot be identified, each supplier of the product becomes liable, unless he informs the injured person within a reasonable time of the identity of the producer, or of the person who supplied him with the product. When several persons are liable for the same damage, they are all jointly and severally liable.

The producer must compensate damages caused by the defective product to individuals (death, personal injury) and private property (goods for private use). However, the Directive does not cover any damage to property under EUR 500 (24) for a single incident. National law may govern non-material damages (such as pain and suffering). The Directive does not cover the destruction of the defective product itself and, therefore, there is no obligation to compensate for it under the Directive on product liability. This is without prejudice to national law.

The Directive on product liability allows Member States to fix a financial ceiling for serial accidents at a minimum of EUR 70 million (25). However, most Member States have not used this possibility.

The producer is not automatically liable for damage caused by the product. The injured person, whether or not he is the buyer or user of the defective product, must claim his rights to obtain compensation. The victims will be paid only if they prove that they have suffered damage, the product was defective, and this product caused the damage. If the injured person contributes to the damage, the producer's liability may be reduced or even eliminated. However, the victims do not need to prove that the producer was negligent because the Directive on product liability is based on the principle of no-fault liability. Thus, the producer will not be exonerated even if he proves he was not negligent, if an act or omission of a third person contributes to the damage caused, if he has applied standards, or if his product has been tested. The producer will not have to pay, if he proves:

|

— |

he did not place the product on the market (for example the product was stolen), |

|

— |

the product was not defective when he placed it on the market (thus he proves that the defect was caused subsequently), |

|

— |

the product was not manufactured to be sold or distributed for economic purpose, |

|

— |

the defect was caused due to compliance with mandatory regulations issued by the public authorities (which excludes national, European and international standards) (26), |

|

— |

the state of scientific and technical knowledge at the time when the product was put on the market could not as such enable the existence of the defect to be discovered (the development risks defence) (27), or |

|

— |

where he is a subcontractor, that the defect was due either to the design of the finished product or to defective instructions given to him by the producer of the finished product. |

10 years after the product is placed on the market, the producer ceases to be liable, unless legal action is pending. Further, the victim must file an action within 3 years of the damage, the defect and the identity of the producer being known. No waivers of liability in relation to the injured person may be agreed.

The Directive on product liability does not require Member States to repeal any other legislation on liability. In this respect, the Directive's regime adds to the existing national rules on liability. It is up to the victim to choose the grounds on which to file the action.

1.5. SCOPE OF THE GUIDE

This Guide discusses non-food and non-agricultural products referred to as industrial products or products whether for use by consumers or professionals. The product-related legislation that deals with these products will be referred throughout the text indistinctly as Union harmonisation legislation, sectoral Union harmonisation legislation or Union harmonisation acts.

The New Legislative Framework consists of a set of legal documents. In particular Decision No 768/2008/EC provides for elements, which are partially or totally implemented in product-related Union harmonisation legislation addressing various public interests. The guide gives guidance for the implementation of the provisions and concepts laid down in the New Legislative Framework (28). Where there are product-specific deviations or provisions the guide refers to sectoral guides, which exist for almost all sectoral Union harmonisation legislation.

The present Guide has the ambition of explaining the different elements of the New Legislative Framework in detail and of contributing to a better overall understanding of the system so that legislation is implemented properly and is therefore effective for the protection of public interests such as health and safety, consumers, the environment and public security, as well as the proper functioning of the internal market for economic operators. Furthermore, the Guide promotes the goals of the Commission's better regulation policy by contributing to the development of more comprehensive, coherent and proportionate legislation.

Each of these chapters should be read in conjunction with the explanations set out above, in other words against the general background, and in conjunction with the other chapters, as they are all interlinked and should not be seen in isolation.

|

This guide primarily relates to the Union legislation on:

|

However, elements of this Guide might be relevant for other Union harmonisation legislation going even beyond the realm of industrial products. This is particularly true for the various definitions in the Guide as well as the chapters bearing on standardisation, conformity assessment, accreditation and market surveillance. Although, it is neither correct nor desirable to dress an exhaustive list of relevant legislation, a larger list of legislation concerned is provided in Annex I.

The Guide does not attempt to cover:

|

— |

the Directive on General Product Safety (29). The Commission services have provided specific guidance on the practical application of the GPSD (30). |

|

— |

the Union legislation on motor vehicles, construction products, REACH, and chemicals. |

2. WHEN DOES UNION HARMONISATION LEGISLATION ON PRODUCTS APPLY?

2.1. PRODUCT COVERAGE

|

Union harmonisation legislation applies to products which are intended to be placed (or put into service (31)) on the market (32). Furthermore, Union harmonisation legislation applies when the product is placed on the market (or put into service) and to any subsequent making available until the product reaches the end-user (33) (34) (35). A product still in the distribution chain falls under the obligations of the Union harmonisation legislation as long as it is a new product. (36) Once it reaches the end-user it is no longer considered a new product and the Union harmonisation legislation no longer applies (37). The end-user is not one of the economic operators who bear responsibilities under Union harmonisation legislation, i.e. any operation or transaction by the end-user involving the product is not subject to Union harmonisation legislation. However, such an operation or transaction might fall under another regulatory regime, in particular at national level.

The product must comply with the legal requirements that were in place at the time of its placing on the market (or putting into service).

Union harmonisation legislation applies to all form of supply, including distance selling and selling through electronic means. Hence, regardless of the selling technique products intended to be made available on the Union market must be in conformity with the applicable legislation.

A product intended to be placed on the Union market, offered in a catalogue or by means of electronic commerce, has to comply with Union harmonisation legislation when the catalogue or website directs its offer to the Union market and includes an ordering and shipping system (38). Where a product is not intended for the Union market or is not compliant with the applicable Union legislation, this has to be clearly indicated (e.g. by providing a visual warning).

The Union harmonisation legislation applies to newly manufactured products but also to used and second-hand products, including products resulting from the preparation for re-use of electrical or electronic waste, imported from a third country when they enter the Union market for the first time (39) (40). This applies even to used and second-hand products imported from a third country that were manufactured before the legislation became applicable (41).

Union harmonisation legislation applies to finished products. Yet, the concept of product varies between different pieces of Union harmonisation legislation. The objects covered by legislation are referred to, for instance, as products, equipment, apparatus, devices, appliances, instruments, materials, assemblies, components or safety components, units, fittings, accessories, systems or partly completed machinery. Thus, within the terms of a specific Union harmonisation act, components, spare parts or sub-assemblies may be regarded as finished products and their end-use may be the assembly or incorporation into a finished product. It is the responsibility of the manufacturer to verify whether or not the product is within the scope of a given piece of Union harmonisation legislation (42) (43).

A combination of products and parts, which each comply with applicable legislation, does not always constitute a finished product that has to comply itself as a whole with a given Union harmonisation legislation. However, in some cases, a combination of different products and parts designed or put together by the same person is considered as one finished product which has to comply with the legislation as such. In particular, the manufacturer of the combination is responsible for selecting suitable products to make up the combination, for putting the combination together in such a way that it complies with the provisions of the laws concerned, and for fulfilling all the requirements of the legislation in relation to the assembly, the EU declaration of conformity and CE marking. The fact that components or parts are CE marked does not automatically guarantee that the finished product also complies. Manufacturers must choose components and parts in such a way that the finished product itself complies. The manufacturer must verify on a case-by-case basis whether a combination of products and parts has to be considered as one finished product in relation with the scope of the relevant legislation.

A product, which has been subject to important changes or overhaul aiming to modify its original performance, purpose or type after it has been put into service, having a significant impact on its compliance with Union harmonisation legislation, must be considered as a new product. This has to be assessed on a case-by-case basis and, in particular, in view of the objective of the legislation and the type of products covered by the legislation in question. Where a rebuilt (44) or modified product is considered as a new product, it must comply with the provisions of the applicable legislation when it is made available or put into service. This has to be verified by applying the appropriate conformity assessment procedure laid down by the legislation in question. In particular, if the risk assessment leads to the conclusion that the nature of the hazard has changed or the level of risk has increased, then the modified product has to be considered as a new product, i.e. compliance of the modified product with the applicable essential requirements has to be reassessed and the person carrying out the modification has to fulfil the same requirements as an original manufacturer, for example preparation of the technical documentation, drawing up a EU declaration of conformity and affixing the CE marking on the product.

In any case, a modified product sold under the name or trademark of a natural or legal person different from the original manufacturer, should be considered as new and subject to Union harmonisation legislation. The person who carries out important changes to the product carries the responsibility for verifying whether or not it should be considered as a new product in relation to the relevant Union harmonisation legislation. If the product is to be considered as new, this person becomes the manufacturer with the corresponding obligations. Furthermore, in the case the conclusion is that it is a new product, the product has to undergo a full conformity assessment before it is made available on the market. However, the technical documentation has to be updated in as much as the modification has an impact on the requirements of the applicable legislation. It is not necessary to repeat tests and produce new documentation in relation to aspects not impacted by the modification, as long as the manufacturer has copies (or access to copies) of the original test reports for the unchanged aspects. It is up to the natural or legal person who carries out changes or has changes carried out to the product to demonstrate that not all elements of the technical documentation need to be updated.

Products which have been repaired or exchanged (for example following a defect), without changing the original performance, purpose or type, are not to be considered as new products according to Union harmonisation legislation. Thus, such products do not need to undergo conformity assessment again, whether or not the original product was placed on the market before or after the legislation entered into force. This applies even if the product has been temporarily exported to a third county for the repair operations. Such repair operations are often carried out by replacing a defective or worn item by a spare part, which is either identical, or at least similar, to the original part (for example modifications may have taken place due to technical progress, or discontinued production of the old part), by exchanging cards, components, sub-assemblies or even entire identical units. If the original performance of a product is modified (within the intended use, range of performance and maintenance originally conceived at the design stage) because the spare-parts used for its repair perform better due to technical progress, this product is not to be considered as new according to Union harmonisation legislation. Thus, maintenance operations are basically excluded from the scope of the Union harmonisation legislation. However, at the design stage of the product the intended use and maintenance must be taken into account (45).

Software updates or repairs could be assimilated to maintenance operations provided that they do not modify a product already placed on the market in such a way that compliance with the applicable requirements may be affected.

2.2. MAKING AVAILABLE ON THE MARKET

|

A product is made available on the market when supplied for distribution, consumption or use on the Union market in the course of a commercial activity, whether in return for payment or free of charge. (46) Such supply includes any offer for distribution, consumption or use on the Union market which could result in actual supply (e.g. an invitation to purchase, advertising campaigns).

Supplying a product is only considered as making available on the Union market, when the product is intended for end use on the Union market. The supply of products whether for further distribution, for incorporation into a final product, or for further processing or refinement with the aim to export the final product outside the Union market is not considered as making available. Commercial activity is understood as providing goods in a business related context. Non-profit organisations may be considered as carrying out commercial activities if they operate in such a context. This can only be appreciated on a case by case basis taking into account the regularity of the supplies, the characteristics of the product, the intentions of the supplier etc. In principle, occasional supplies by charities or hobbyists should not be considered as taking place in a business related context.

‘Use’ refers to the intended purpose of the product as defined by the manufacturer under conditions which can be reasonably foreseen. Usually, this is the end use of the product.

The central role that the concept of making available plays in Union harmonisation legislation is related to the fact that all economic operators in the supply-chain have traceability obligations and need to have an active role in ensuring that only compliant products circulate on the Union market.

The concept of making available refers to each individual product, not to a type of product, and whether it was manufactured as an individual unit or in series.

The making available of a product supposes an offer or an agreement (written or verbal) between two or more legal or natural persons for the transfer of ownership, possession or any other right (47) concerning the product in question after the stage of manufacture has taken place. The transfer does not necessarily require the physical handover of the product.

This transfer can be for payment or free of charge, and it can be based on any type of legal instrument. Thus, a transfer of a product is considered to have taken place, for instance, in the circumstances of sale, loan, hire (48), leasing and gift. Transfer of ownership implies that the product is intended to be placed at the disposal of another legal or natural person.

2.3. PLACING ON THE MARKET

|

For the purposes of Union harmonisation legislation, a product is placed on the market when it is made available for the first time on the Union market. The operation is reserved either for a manufacturer or an importer, i.e. the manufacturer and the importer are the only economic operators who place products on the market (49). When a manufacturer or an importer supplies a product to a distributor (50) or an end-user for the first time, the operation is always labelled in legal terms as ‘placing on the market’. Any subsequent operation, for instance, from a distributor to distributor or from a distributor to an end-user is defined as making available.

As for ‘making available’, the concept of placing on the market refers to each individual product, not to a type of product, and whether it was manufactured as an individual unit or in series. Consequently, even though a product model or type has been supplied before new Union harmonisation legislation laying down new mandatory requirements entered into force, individual units of the same model or type, which are placed on the market after the new requirements have become applicable, must comply with these new requirements.

Placing a product on the market requires an offer or an agreement (written or verbal) between two or more legal or natural persons for the transfer of ownership, possession or any other property right concerning the product in question after the stage of manufacture has taken place (51). This transfer could be for payment or free of charge. It does not require the physical handover of the product.

Placing on the market is considered not to take place where a product is:

|

— |

manufactured for one's own use. Some Union harmonisation legislation however covers products manufactured for own use in its scope (52) (53), |

|

— |

bought by a consumer in a third country while physically present in that country (54) and brought by the consumer into the EU for the personal use of that person, |

|

— |

transferred from the manufacturer in a third country to an authorised representative in the Union whom the manufacturer has engaged to ensure that the product complies with the Union harmonisation legislation (55), |

|

— |

introduced from a third country in the EU customs territory in transit, placed in free zones, warehouses, temporary storage or other special customs procedures (temporary admission or inward processing) (56), |

|

— |

manufactured in a Member State with a view to exporting it to a third country (this includes components supplied to a manufacturer for incorporation into a final product to be exported into a third country), |

|

— |

transferred for testing or validating pre-production units considered still in the stage of manufacture, |

|

— |

displayed or operated under controlled conditions (57) at trade fairs, exhibitions or demonstrations (58), or |

|

— |

in the stocks of the manufacturer (or the authorised representative established in the Union) or the importer, where the product is not yet made available, that is, when it is not being supplied for distribution, consumption or use, unless otherwise provided for in the applicable Union harmonisation legislation. |

Products offered for sale by online operators (59) (60) based in the EU are considered to have been placed on the Union market, regardless of who placed them on the market (the online operator, the importer, etc.). Products offered for sale online by sellers based outside the EU are considered to be placed on the Union market if sales are specifically targeted at EU consumers or other end-users. The assessment of whether or not a website located inside or outside the EU targets EU consumers has to be done on a case-by-case basis, taking into account any relevant factors such as the geographical areas to which dispatch is possible, the languages available used for the offer or for ordering, payment possibilities, etc. (61) When an online operator delivers in the EU, accepts payment by EU consumers/end-users and uses EU languages, then it can be considered that the operator has expressly chosen to supply products to EU consumers or other end-users. Online operators may offer online for sale a product type or an individual product which has been already manufactured. When the offer refers to a product type, the placing on the market will only take place after the stage of manufacture has been completed.

As the products offered for sale by an online operator are likely to be (or have already been) ordered by consumers or businesses in the EU, they are being supplied in the context of a commercial activity by way of online sales. Generally products are offered for sale online in return for payment. Nevertheless, the supply of products free of charge can also be a commercial activity (62). As for consumer to consumer (C2C) sales, these are generally not considered as commercial activities. Nevertheless the assessment of whether a C2C product is being supplied in the framework of a commercial activity has to be done on a case-by-case basis, taking into account all relevant criteria such as the regularity of the supplies, the intention of the supplier, etc. (63)

The legal consequence is that products offered for sale by online operators need to comply with all applicable EU rules when placed on the market (64). Such compliance can be physically verified by responsible authorities when the products are in their jurisdiction, at the soonest, at the customs.

In addition, products offered by online operators are generally stored in fulfilment houses located in the EU to guarantee their swift delivery to EU consumers. Accordingly, products stored in such fulfilment houses are considered to have been supplied for distribution, consumption or use in the EU market and thus placed on the EU market. When an online operator uses a fulfilment house, by shipping the products to the fulfilment house in the EU the products are in the distribution phase of the supply chain (65).

The placing on the market is the most decisive point in time concerning the application of the Union harmonised legislation (66). When made available on the market, products must be in compliance with the Union harmonisation legislation applicable at the time of placing on the market. Accordingly, new products manufactured in the Union and all products imported from third countries — whether new or used — must meet the provisions of the applicable Union harmonisation legislation when placed on the market, i.e. when made available for the first time on the Union market. Compliant products once they have been placed on the market may subsequently be made available along the delivery chain without additional considerations, even in case of revisions to the applicable legislation or the relevant harmonised standards, unless otherwise specified in the legislation.

Member States have an obligation in the framework of market surveillance to ensure that only safe and compliant products are on the market (67). Used products, which are on the Union market, are subject to free movement according to the principles laid down by Articles 34 and 36 TFEU. It must be noted that used products made available to consumers in the course of a commercial activity are subject to the GPSD.

2.4. PRODUCTS IMPORTED FROM COUNTRIES OUTSIDE THE EU

|

Union harmonisation legislation applies when the product is made available (or put into service (68)) on the Union market for the first time. It also applies to used and second-hand products imported from a third country, including products resulting from the preparation for re-use of electrical or electronic waste, when they enter the Union market for the first time, but not to such products already on the market. It applies even to used and second-hand products imported from a third country that were manufactured before the Union harmonisation legislation became applicable.

The basic principle of EU product rules is that irrespective of the origins of the products, they need to be compliant with the applicable Union harmonisation legislation if they are made available on the Union market. Products manufactured in the EU and products from non-EU countries are treated alike.

Before they can reach the end-user in the EU, products coming from countries outside the EU will be presented to customs under the release for free circulation procedure. The purpose of release for free circulation is to fulfil all import formalities so that the goods can be made available on the EU market like any product made in the EU. Therefore when products are presented to customs under the release for free circulation procedure, it can generally be considered that the goods are being placed on the EU market and so they will need to be compliant with the applicable Union harmonisation legislation. However, it may also be the case that the release for free circulation and the placing on the market do not take place at the same time. The placing on the market is the moment in which the product is supplied for distribution, consumption or use for the purposes of compliance with Union harmonisation legislation. Placing on the market can take place before the release for free circulation, for example, in the case of online sales by economic operators located outside the EU, even if the physical check of the compliance of the products can take place at the earliest when they arrive at the customs in the EU. Placing on the market can also take place after release for free circulation.

Customs authorities and market surveillance authorities have the obligation and the power, based on risk analyses, to check products arriving from third countries and intervene as appropriate before their release for free circulation, irrespective of when they are considered to be placed on the Union market. This is to prevent the release for free circulation and thus the making available in the EU territory of products which are not in compliance with the relevant Union harmonisation legislation (69).

For products imported from countries outside the EU, Union harmonisation legislation envisages a special role for the importer. The latter assumes certain obligations which to some extent mirror the obligations of manufacturers based within the EU (70).

In the case of products imported from countries outside the EU, an authorised representative may carry out a number of tasks on behalf of the manufacturer (71). If however, the authorised representative of a third country manufacturer supplies a product to a distributor or a consumer within the EU, he then no longer acts as a mere authorised representative but becomes the importer and is subject to the obligations of importers.

2.5. PUTTING INTO SERVICE OR USE (AND INSTALLATION)

|

Putting into service takes place at the moment of first use within the Union by the end user for the purposes for which it was intended (72) (73). The concept is used, for example, in the field of Lifts, Machinery, Radio equipment, Measuring instruments, Medical devices, in vitro diagnostic medical devices or products covered by the EMC or ATEX-directives, in addition to placing on the market, and results in the scope of Union harmonisation legislation being extended beyond the moment of making available of a product (74).

Where the product is put into service by an employer for use by his employees, the employer is considered as the end-user.

Member States may not prohibit, restrict or impede the putting into service of products that meet the provisions of the applicable Union harmonisation legislation (75). However, Member States are allowed to maintain and adopt, in compliance with the Treaty (in particular Articles 34 and 36 TFEU) and subject to Union harmonisation legislation, additional national provisions regarding the putting into service, installation or use, of products which are intended for the protection of workers or other users, or other products. Such national provisions may not require modifications of a product manufactured in accordance with the provisions of the applicable Union harmonisation legislation.

The need to demonstrate compliance of products at the moment of putting into service, and — if applicable — that they are correctly installed, maintained and used for the intended purpose, should be limited to products:

|

— |

which have not been placed on the market prior to their putting into service or which can be used only after an assembly, an installation or other manipulation has been carried out, or |

|

— |

whose compliance can be influenced by the distribution conditions (for example storage or transport). |

2.6. SIMULTANEOUS APPLICATION OF UNION HARMONISATION ACTS

|

Union harmonisation legislation covers a wide range of products, hazards and impacts (76), which both overlap and complement each other. As a result, the general rule is that several pieces of legislation may have to be taken into consideration for one product, since the making available or putting into service can only take place when the product complies with all applicable provisions and when the conformity assessment has been carried out in accordance with all applicable Union harmonisation legislation.

Hazards covered by the requirements of various Union harmonisation acts would typically concern different aspects that in many cases complement each other (for example the Directives relating to Electromagnetic Compatibility and Pressure Equipment cover phenomena not covered by the Directives relating to Low-voltage Equipment or Machinery). This calls for a simultaneous application of the various legislative acts. Accordingly, the product has to be designed and manufactured in accordance with all applicable Union harmonisation legislation, as well as to undergo the conformity assessment procedures according to all applicable legislation, unless otherwise provided for.

Certain Union harmonisation acts exclude from their scope products covered by other acts (77) or incorporate the essential requirements of other acts (78) which avoids simultaneous application of redundant requirements. In other instances, this is not the case and the general principle of simultaneous application still applies where the requirements of the Union harmonisation acts are complementary to each other.

Two or more Union harmonisation acts can cover the same product, hazard or impact. In such a case, the issue of overlap might be resolved by giving preference to the more specific Union harmonisation act (79). This usually requires a risk analysis of the product, or sometimes an analysis of the intended purpose of the product, which then determines the applicable legislation. In specifying the hazards relating to a product, the manufacturer may use the relevant harmonised standards applicable for the product in question.

2.7. INTENDED USE/MISUSE

|

Manufacturers have to match a level of protection corresponding to the use they prescribe to the product under the conditions of use which can be reasonably foreseen. |

Union harmonisation legislation applies in the case products made available or put into service (80) on the market are used for their intended use. Intended use means either the use for which a product is intended in accordance with the information provided by the person placing it on the market, or the ordinary use as determined by the design and construction of the product.

Usually such products are ready for use, or require only adjustments that can be performed in view of their intended use. Products are ‘ready for use’ if they can be used as intended without the insertion of additional parts. Products are also deemed ready for use if all parts from which they are to be assembled are placed on the market by one person only, or they only need to be mounted or plugged in, or they are placed on the market without the parts that are usually procured separately and inserted for the intended use (e.g. a cable for electric supply).

Manufacturers are required to match a level of protection for the users of the products which corresponds to the use that the manufacturer prescribes for the product in the product information. This is particularly relevant in the cases where a misuse of a product is at stake (81).

As far as market surveillance activities are concerned, market surveillance authorities are required to check the conformity of a product:

|

— |

in accordance with its intended purpose (as defined by the manufacturer) and |

|

— |

under the conditions of use which can be reasonably foreseen, that is when such use could result from lawful and readily predictable human behaviour. |

The consequence for manufacturers is that they have to consider the conditions of use which can be reasonably foreseen prior to placing a product on the market.

Manufacturers have to look beyond what they consider the intended use of a product and place themselves in the position of the average user of a particular product and envisage in what way they would reasonably consider to use the product (82).

It is also important that market surveillance authorities take into account that not all risks can be prevented by product design. The supervision and assistance of the intended users should be considered as part of the conditions which can be reasonably foreseen. For instance, some professional machine tools are intended for use by averagely skilled and trained workers under the supervision of their employer; the responsibility of the manufacturer cannot be engaged if such machine tools are rented by a distributor or third party service-provider for use by unskilled and untrained consumers.

In any case, the manufacturer is not obliged to expect that users will not take into consideration the lawful conditions of use of his product.

2.8. GEOGRAPHICAL APPLICATION (EEA EFTA STATES, OVERSEAS COUNTRIES AND TERRITORIES (OCTS), TURKEY)

|

2.8.1. MEMBER STATES AND OVERSEAS COUNTRIES AND TERRITORIES

The purpose of Union harmonisation legislation relating to goods adopted pursuant to Articles 114 and 115 TFEU is the establishment and functioning of the internal market for goods. Consequently, Union harmonisation legislation cannot be separated from Treaty provisions on free movement of goods and the territorial scope of application of Union harmonisation legislation should coincide with the territorial scope of application of Articles 30 and 34 to 36 TFEU.

Pursuant to Article 355 TFEU and in connection with the Article 52 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU), the Treaty and consequently the Union harmonisation legislation applies to all Member States of the European Union. Pursuant to Article 355(1) TFEU it also applies to Guadeloupe, French Guyana, Martinique, Réunion, Saint-Martin, the Azores, Madeira and the Canary Islands. Moreover, the Treaty and harmonisation legislation relating to products adopted on the basis of Articles 114 and 115 TFEU applies to certain European territories to the extent necessary to give effect to the arrangements set out in the relevant Accession Treaty (83).

However, it applies neither to Faeroe Islands, Greenland, Akrotiri and Dhekelia, nor to those overseas countries and territories having special relations with the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland such as Gibraltar. The Union harmonisation legislation does not apply to overseas countries and territories, in particular: New Caledonia and Dependencies, French Polynesia, French Southern and Antarctic Territories, Wallis and Futuna Islands, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, Saint-Barthélemy, Aruba, Curaçao, Sint Maarten, Caribbean Netherlands (Bonaire, Saba and Sint Eustatius), Anguilla, Cayman Islands, Falkland Islands, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, Montserrat, Pitcairn, Saint Helena and Dependencies, British Antarctic Territory, British Indian Ocean Territory, Turks and Caicos Islands, British Virgin Islands, Bermuda.

2.8.2. EEA EFTA STATES

2.8.2.1. Basic elements of the Agreement on the European Economic Area