(50)

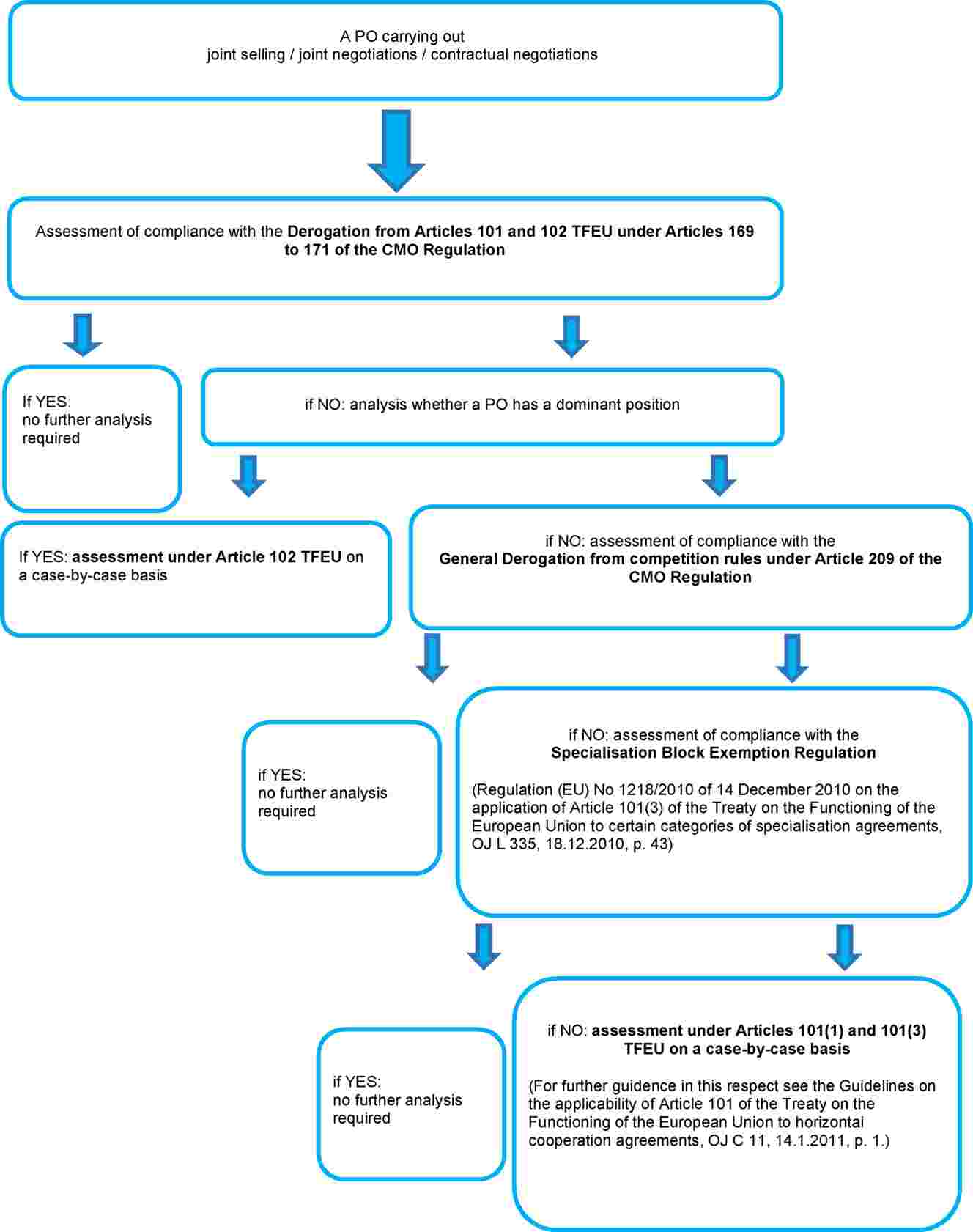

A PO in the olive oil, beef and veal and arable crops sectors should assess its compliance with the competition rules in the following way:

|

22.12.2015 |

EN |

Official Journal of the European Union |

C 431/1 |

COMMISSION NOTICE

Guidelines on the application of the specific rules set out in Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation for the olive oil, beef and veal and arable crops sectors

(2015/C 431/01)

CONTENTS

|

1. |

INTRODUCTION: PURPOSE AND SCOPE OF THESE GUIDELINES | 3 |

|

2. |

GENERAL AND SECTORIAL RULES APPLICABLE TO AGREEMENTS CONCLUDED BY PRODUCERS OF OLIVE OIL, BEEF AND VEAL AND ARABLE CROPS | 4 |

|

2.1. |

Introduction | 4 |

|

2.2. |

General competition framework | 4 |

|

2.2.1. |

Application of Articles 101 and 102 TFEU to production of and trade in agricultural products | 4 |

|

2.2.2. |

Specific derogations outside the agricultural legislation from the application of Article 101 TFEU: Specialisation Block Exemption Regulation | 8 |

|

2.3. |

General derogation in the CMO Regulation: Articles 206 and 209 | 9 |

|

2.4. |

Derogation from the application of Articles 101 and 102 TFEU to the sectors of olive oil, beef and veal, and arable crops, as set out in Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation | 10 |

|

2.5. |

Assessment by a PO of the compatibility of an agreement with the competition rules | 12 |

|

3. |

CONDITIONS FOR THE APPLICATION OF THE DEROGATION | 14 |

|

3.1. |

Recognition of the PO/APO | 14 |

|

3.2. |

PO's objectives and procurement of products from non-members | 15 |

|

3.3. |

The Significant Efficiency Test | 16 |

|

3.3.1. |

The simplified method | 18 |

|

3.3.2. |

The alternative method | 29 |

|

3.4. |

Relations between a PO and its members | 29 |

|

3.5. |

Production cap | 30 |

|

3.6. |

Obligation to notify | 31 |

|

3.7. |

Safeguards | 31 |

|

3.7.1. |

Introduction | 31 |

|

3.7.2. |

Exclusion of competition | 32 |

|

3.7.3. |

Smaller relevant product market with anti-competitive effects | 32 |

|

3.7.4. |

CAP objectives are jeopardised | 33 |

|

4. |

SPECIFIC PROVISIONS ON THE CONCERNED SECTORS | 33 |

|

4.1. |

Olive oil | 33 |

|

4.1.1. |

Examples of application of the derogation to the olive oil sector | 33 |

|

4.1.2. |

Identification of the relevant market | 35 |

|

4.1.2.1. |

Relevant product market | 35 |

|

4.1.2.2. |

Relevant geographical market | 35 |

|

4.2. |

Beef and veal sector | 35 |

|

4.2.1. |

Examples of application of the derogation to the beef and veal sector | 35 |

|

4.3. |

Arable crops | 37 |

|

4.3.1. |

Examples of application of the derogation to the arable crops sector | 37 |

|

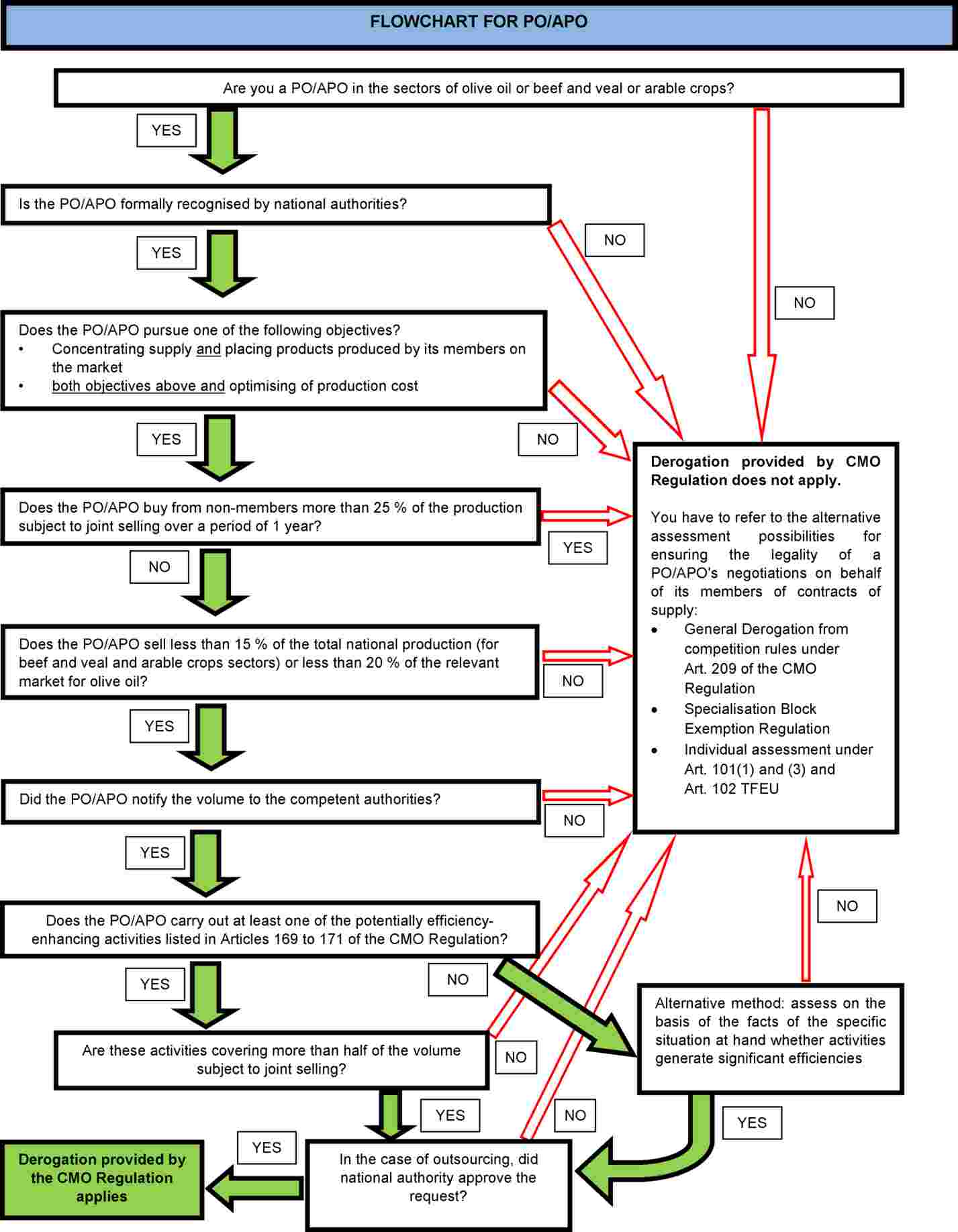

ANNEX I: |

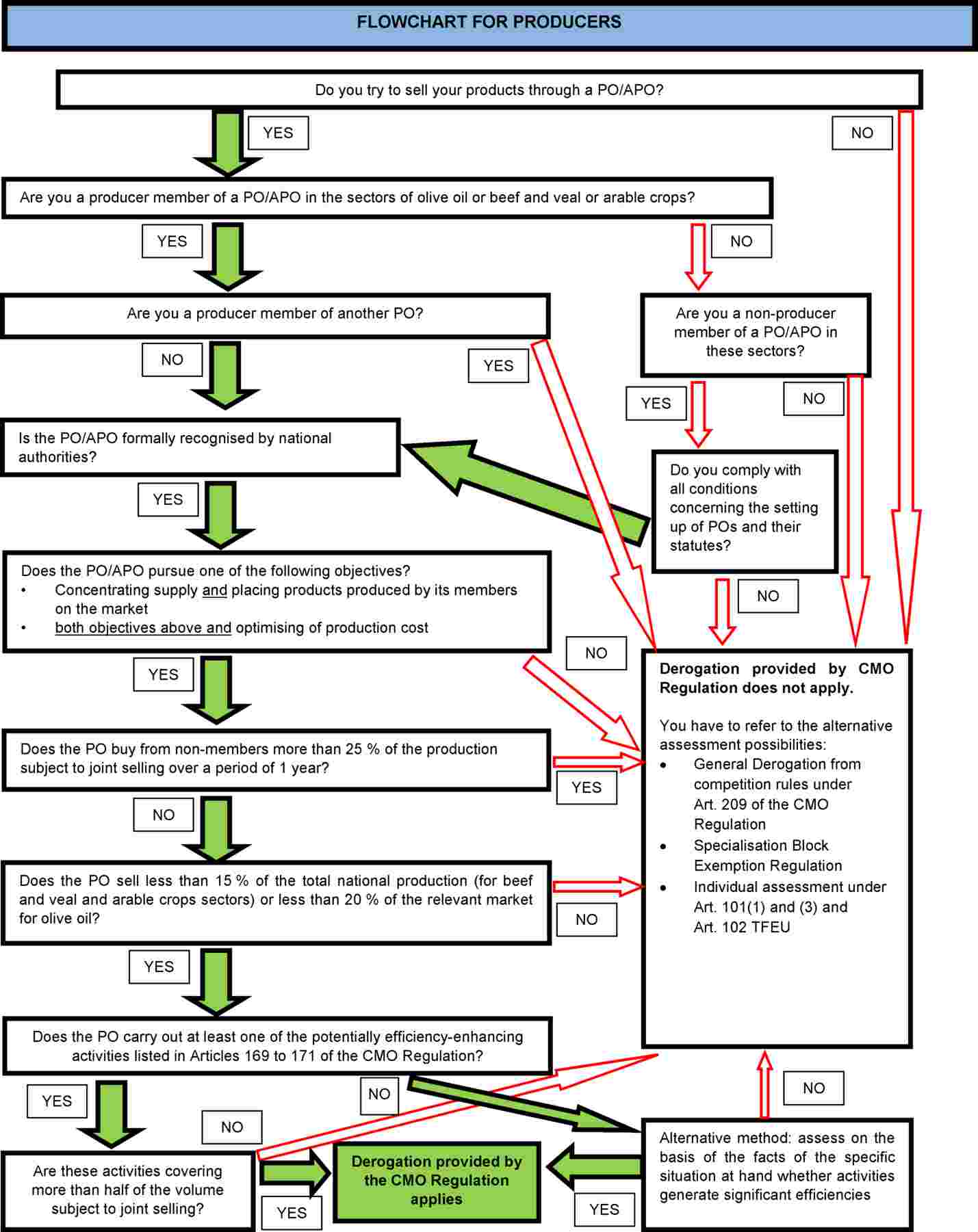

Flowchart for Producers | 40 |

|

ANNEX II: |

Flowchart for POs/APOs | 41 |

1. INTRODUCTION: PURPOSE AND SCOPE OF THESE GUIDELINES

|

(1) |

These Guidelines (1) give guidance to producers of olive oil, beef and veal and arable crops sectors on how to comply with Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation (2) laying down specific rules for contractual negotiations in these sectors. They are issued pursuant to Article 206 paragraph 3 of the CMO Regulation (3). |

|

(2) |

These Guidelines are not legally binding. While they aim to provide specific guidance to producers, it remains the responsibility of the producers to assess their own practices. The Guidelines also intend to give guidance to the courts and competition authorities of the Member States in the application of Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation. |

|

(3) |

The entities concerned by these Guidelines are defined as follows:

Where the Guidelines refer to a PO (POs), that reference should be understood as including an APO (APOs) if not explicitly specified otherwise. A PO can be established under different legal forms, depending on the applicable national rules. Where cooperatives are recognised as POs they can benefit from Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation. Recognised interbranch organisations are not covered by Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation. They may however benefit from the derogation possibility set out in Article 210 of the CMO Regulation. |

|

(4) |

Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation allow POs and APOs to negotiate, on behalf of their members, contracts for the supply of the products concerned under a number of conditions (4). |

|

(5) |

The Guidelines address the following issues:

|

|

(6) |

The European Commission's position is without prejudice to the case law of the Court of Justice of the European Union (5) concerning the interpretation of Articles 39, 42, 101 and 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (hereinafter the ‘TFEU’) and of Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation. |

|

(7) |

The Commission will continue to monitor the operation of the Guidelines based on market information from the stakeholders and NCAs and may revise the Guidelines in the light of future developments and of evolving insight. Unless there is a revision of the Guidelines, they will remain valid as long as Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation are not modified. In the case of modification of all or any of the aforementioned articles, the Guidelines will, where appropriate, be revised and updated according to the adopted changes. |

2. GENERAL AND SECTORIAL RULES APPLICABLE TO AGREEMENTS CONCLUDED BY PRODUCERS OF OLIVE OIL, BEEF AND VEAL AND ARABLE CROPS

2.1. Introduction

|

(8) |

Article 42 TFEU confers on the EU legislator (the European Parliament and the Council) the power to determine the extent to which competition rules apply to the production of and trade in agricultural products. |

|

(9) |

More precisely, according to Article 42 TFEU the EU legislator determines the extent of the application of competition rules to the agricultural sector, taking into account the objectives of the Common Agricultural Policy (hereinafter the ‘CAP objectives’) set out in Article 39 TFEU. According to the Court of Justice that provision recognises the precedence of the objectives of the agricultural policy over the aims of the Treaty in relation to competition (6). |

|

(10) |

According to Article 39 TFEU, the CAP objectives are the following:

|

2.2. General competition framework

2.2.1. Application of Articles 101 and 102 TFEU to production of and trade in agricultural products

|

(11) |

On the basis of Article 42 TFEU, Article 206 of the CMO Regulation declares the competition rules in Articles 101 to 106 TFEU applicable to the production and trade in agricultural products: ‘Save as otherwise provided in this Regulation, and in accordance with Article 42 TFEU, Articles 101 to 106 TFEU and the implementing provisions thereto shall, subject to Articles 207 to 210 of this Regulation, apply to all agreements, decisions and practices referred to in Article 101(1) and Article 102 TFEU which relate to the production of, or trade in, agricultural products.’ |

|

(12) |

Articles 101 (7) and 102 (8) TFEU apply to the behaviour of undertakings and associations of undertakings in the form of agreements, decisions, practices or an abuse of a dominant position, only insofar as they ‘may affect trade between Member States’. Details concerning the interpretation of this applicability criterion are contained in the European Commission's Guidelines on the effect on trade (9). If trade between Member States is not affected, national competition rules apply. |

|

(13) |

Article 101 TFEU applies, in principle, to all economic activities of producers and POs. A PO is an association of individual producers and consequently is considered to be both an association of undertakings and an undertaking in its own right for the purposes of applying EU competition law (10), where it conducts an economic activity. Consequently, both a PO and its members must comply with competition rules. Accordingly, competition rules apply not only to the agreements between individual producers (e.g. the creation of a PO and its founding statutes), but also to the decisions taken and the contracts concluded by the PO. |

|

(14) |

The Court of Justice has handed down a number of judgements which deal with cooperatives in particular. Indeed, cooperatives are a specific form of PO. When assessing the applicability of Article 101(1) TFEU to cooperatives (which is one of the possible forms in which a PO can be set up), the Court of Justice held that organising an undertaking in the specific form of a cooperative association does not in itself constitute anti-competitive conduct. However, this does not mean that cooperative associations as such automatically fall outside the prohibition of Article 101(1) TFEU as they may nevertheless be liable to influence the trading conduct of its members so as to restrict or distort competition in the market in which those undertakings operate (11). |

|

(15) |

Example of the application of Article 101 TFEU to the activities of producers:

|

|

(16) |

Article 102 TFEU also applies to producers as well as to a PO acting as an undertaking. The prohibition of abuse of a dominant position provided for in Article 102 TFEU is fully applicable in the agricultural sector. However, in order for Article 102 TFEU to be infringed, the following conditions have to be fulfilled:

|

|

(17) |

Example of the application of Article 102 TFEU to the activities of a PO.

|

|

(18) |

Article 101 TFEU can also apply to agreements, including internal decisions and statutes of a PO made between members of a PO and between a PO and its members, when they are actual or potential competitors, in the same product market. This can be the case (a) if producers are able, according to the PO statutes, to exit the PO at short notice; (b) if they are able to freely decide on the volumes they provide the PO with, so that only a part of their production is being sold via the PO. The Court of Justice addressed the issue of statutes of cooperatives and their compliance with Article 101(1) TFEU in several cases, where it recognised the pro-competitive effects of such cooperative arrangements under certain conditions (16) and where it noted that statutory rules governing the exit of members from the PO and obligations for supplies can escape the prohibition of Article 101(1) TFEU under certain conditions and provided that this is limited to what is necessary to ensure that the PO functions properly (17). |

|

(19) |

Example of the application of Article 101 TFEU to the agreements between members of a PO.

|

2.2.2. Specific derogations outside the agricultural legislation from the application of Article 101 TFEU: Specialisation Block Exemption Regulation

|

(20) |

In accordance with Commission Regulation (EU) No 1218/2010 (18) (hereinafter ‘the Specialisation Block Exemption’) specialisation agreements may include, inter alia, agreements, decisions or concerted practices between undertakings whereby they agree to jointly produce certain products or to subcontract to each other the production of one or more products (one undertaking becoming the exclusive producer for one of these products) (19). |

|

(21) |

With particular regard to the agricultural sector, a specialisation agreement may refer to joint production of agricultural products and any activity of processing/transforming agricultural products into other products, such as slaughtering and cutting meat, milling cereals, etc. In the context of agricultural POs, a specialisation agreement is more likely to concern processing/transforming of raw agricultural products into other products as there are few joint-ventures on production of raw agricultural products. |

|

(22) |

The Specialisation Block Exemption Regulation lays down that, pursuant to Article 101(3) TFEU, Article 101(1) TFEU does not apply to specialisation agreements provided that certain conditions are met (20). |

|

(23) |

First, the combined market shares of the parties must not exceed 20 % of the relevant market. |

|

(24) |

Second, the specialisation agreements must not include any hard-core restrictions i.e. fixing prices, limiting output and allocating markets or customers. |

|

(25) |

There are however exceptions. The safe harbour of the Specialisation Block Exemption may apply to (21):

|

|

(26) |

Example of possible application of Specialisation Block Exemption in the agricultural sector.

|

2.3. General derogation in the CMO Regulation: Articles 206 and 209

|

(27) |

Article 206 of the CMO Regulation provides that Articles 101 to 106 TFEU apply to agreements on agricultural products save otherwise provided in the CMO Regulation. Therefore, Article 206 of the CMO Regulation confirms the general principle that EU competition law applies to production and trade in agricultural products. This is however subject, as a general rule, to Articles 207 to 210 of the CMO Regulation. |

|

(28) |

Article 209 of the CMO Regulation excludes from the scope of application of Article 101(1) TFEU agreements, decisions and concerted practices which relate to the production of, or trade in, agricultural products if certain conditions are met. Such a derogation, unlike the one contained in Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation, applies to all agricultural sectors covered by the CMO Regulation. Thus, Article 209 of the CMO Regulation is a separate, self-standing instrument and is referred to hereinafter as the ‘General Derogation’. |

|

(29) |

Producers can benefit from this General Derogation in two different situations:

|

|

(30) |

The General Derogation (both forms) is not applicable to agreements, decisions and concerted practices which involve an obligation to charge an identical price or by which competition is excluded. |

|

(31) |

No prior decision of the European Commission or of a National Competition Authority is necessary in order to benefit from the General Derogation set out in Article 209 of the CMO Regulation, i.e. it applies automatically and producers must assess for themselves whether they meet its conditions. The burden of proving the infringement of Article 101(1) TFEU in any national or EU proceedings rests on those alleging the infringement. However, the party claiming the benefit of the General Derogation bears the burden of proving that the conditions of the General Derogation are fulfilled. |

2.4. Derogation from the application of Articles 101 and 102 TFEU to the sectors of olive oil, beef and veal, and arable crops, as set out in Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation

|

(32) |

According to Article 206 of the CMO Regulation, Articles 101 and 102 TFEU apply to agreements, decisions and practices concerning trading in agricultural products ‘save as otherwise provided in this Regulation’. By setting specific rules for agreements, decisions and practices of producers of agricultural products in certain sectors, Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation create derogations from the application of Articles 101 (23) and 102 TFEU. |

|

(33) |

All together or separately, Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation will be referred to in the Guidelines as ‘the Derogation’. |

|

(34) |

Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation do not result in the terms, rules and subsequent behaviour of POs being outside the scope of Article 102 TFEU. It is very unlikely, given the thresholds laid down in Articles 169(2)(c), 170(2)(c) and 171(2)(c) of the CMO Regulation, that a PO respecting these thresholds would be (collectively) dominant within the meaning of Article 102 TFEU. In such exceptional circumstances, producers should assess whether the activities of that dominant PO could lead to an abuse of a dominant position. |

|

(35) |

Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation concern olive oil, beef and veal products (24), and certain products from the arable crop sector (25). Articles 169(1), 170(1) and 171(1) of the CMO Regulation provide that ‘[a] producer organisation in the […] sector which is recognised under Article 152(1) and which pursues one or more of the objectives of concentrating supply, the placing on the market of the products produced by its members and optimising production costs, may negotiate on behalf of its members, in respect of part or all of the aggregate production of their members, contracts for the supply of’ the products of these sectors covered by the definitions laid out in these articles. |

|

(36) |

Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation concern any agreements or decisions or practices taken by the PO when negotiating contracts for supply on behalf of its members. |

|

(37) |

In particular, paragraph 1 of Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation allow joint supply activities, i.e. joint sales and sales-related activities of agricultural products in the sectors of olive oil, beef and veal, and arable crops by producers of these agricultural products through POs. |

|

(38) |

The purpose of the Derogation is to strengthen the bargaining power of producers in the sectors concerned vis-à-vis downstream operators in order to ensure a fair standard of living for the producers and a viable development of production (26). This objective must be reached in compliance with the CAP objectives as set out in Article 39 TFEU. More precisely, this should be achieved by generating significant efficiencies through the integration of activities in POs so that the activities of these POs overall contribute to the fulfilment of CAP objectives (27). |

|

(39) |

The Derogation's purpose is to be achieved through POs effectively concentrating supply and placing products on the market (28) and, as a consequence, negotiating supply contracts on behalf of their members. Ensuring compliance with the objectives of concentrating supply and placing products on the market requires from such POs that they pursue effectively a commercialisation strategy. |

|

(40) |

In carrying out their strategy, such POs would normally negotiate and conclude supply contracts comprising all the relevant terms: prices, volumes and possibly also other contractual terms such as references to quality specifications of the products, duration of the contract, termination clauses, exit clauses (29), details regarding payment periods and procedures, arrangements for collecting and delivering products as well as rules applicable in the event of force majeure. |

|

(41) |

The implementation of the commercialisation strategy of the PO may also entail agreements and practices between the PO and its members which are intrinsically linked to the commercialisation strategy of a PO such as production planning (30), determining the calendar and volumes of production to be commercialised by the PO (31) and exchanges of commercially sensitive information (32). |

|

(42) |

In the Guidelines, the ‘negotiation of supply contracts by a PO on behalf of its members’ will be referred to as ‘contractual negotiations’. |

|

(43) |

The contractual negotiations can have different forms: e.g. auctions (physical or online), telephone sales, trading on a spot market and/or on a futures exchange. The form of the contractual negotiations does not influence the application of the Derogation. |

|

(44) |

Contractual negotiations may take place with or without the transfer of ownership of the products by the producers to the PO (33). Further, these joint supply activities may take place regardless of whether the price of supply negotiated by the PO is for all or part of the production of the members of the PO (34). |

|

(45) |

However, a PO must fulfil a number of conditions (35) when negotiating supply contracts on behalf of its members in order to benefit from the Derogation:

|

|

(46) |

These specific conditions will be discussed in detail in Section 3 below. |

|

(47) |

An agreement, decision or concerted practice which does not respect the conditions set out by Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation (for instance because the contractual negotiations of arable crop products would cover more than 15 % of the total national production of the product) cannot benefit from the Derogation. This does not automatically mean an infringement of competition rules as discussed in this section. |

2.5. Assessment by a PO of the compatibility of an agreement with the competition rules

|

(48) |

All undertakings, including agricultural producers and POs, must self-assess the compatibility of their agreements, decisions or practices under Article 101(1) and (3) and Article 102 TFEU. |

|

(49) |

In order to provide guidance and facilitate the self-assessment by undertakings of their agreements, decisions and practices, the European Commission has adopted guidelines/guidance concerning the application of Articles 101 and 102 TFEU. In this context, the most relevant are:

|

|

(50) |

A PO in the olive oil, beef and veal and arable crops sectors should assess its compliance with the competition rules in the following way:

|

3. CONDITIONS FOR THE APPLICATION OF THE DEROGATION

|

(51) |

The Derogation created by Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation is subject to a number of conditions regarding:

|

|

(52) |

This section will analyse each of these conditions. |

3.1. Recognition of the PO/APO

|

(53) |

A PO or an APO must be formally recognised by the competent national authorities in line with Article 152(1) and Article 156(1) of the CMO Regulation (40) in order to benefit from the Derogation. A PO can be a legal entity or a part thereof. |

|

(54) |

If a Member State does not recognise POs and/or APOs, producers in that Member State will not be able to benefit from the Derogation. They can still, however, assess their activities under the General Derogation of Article 209 of the CMO Regulation, the Specialisation Block Exemption Regulation and under Article 101(3) TFEU. |

|

(55) |

A PO may be a member of another PO (a so-called ‘second-tier PO’), which commercialises the output supplied by its member POs. The Member State concerned decides whether such second-tier POs are recognised as POs or as APOs. Given that the Derogation applies equally to POs and APOs, the second-tier PO may in both situations benefit from the Derogation. |

|

(56) |

Members of a PO can be, apart from producers, also entities which are not producers of the agricultural products concerned. POs with participation of non-producers must comply with all conditions concerning the setting up of POs and their statutes, including decision-making and democratic control as set out in Articles 152, 153 and 154 of the CMO Regulation. Subject to these conditions, the quantities brought by a non-producer member to the PO are regarded the same way as the products brought by a producer-member of the PO for the purpose of the application of the Derogation. Also, when calculating volumes in order to comply with the Significant Efficiency Test, there is no need to distinguish between products brought by producer-members and by non-producer members. |

3.2. PO's objectives and procurement of products from non-members

|

(57) |

A PO must, in order to benefit from the Derogation, pursue at least one of the following objectives of:

|

|

(58) |

However, the Derogation requires in addition that a PO actually concentrates supply and places the products of its members on the market for the volume of the products covered by contractual negotiations (43). Therefore, pursuing the objective of optimising production costs (letter c. above), if not accompanied by the actual realisation of the remaining two objectives of concentration of supply and the placing on the market of the products produced by its members, will not be sufficient in order to benefit from the Derogation. |

|

(59) |

The objective of placing on the market refers to the products produced by its members. This does not exclude that, as an ancillary activity, a PO may equally include in contractual negotiations products separately bought by the PO. This is consistent with the objective of the PO of concentrating supply. The possibility of including products separately bought from non-members (44) would allow POs, in certain situations, to reach bigger customers requiring larger volumes than what members can offer at a certain moment in time. This possibility would also allow the PO to replace the production of members lacking at certain points in time, for instance due to unfavourable weather conditions, thus avoiding the risk that the PO loses a customer. |

|

(60) |

The Derogation covers both the products of members of a PO as well as of non-members, for their total production or part of it, as long as the thresholds and conditions set out in the Derogation are respected. |

|

(61) |

Under the Derogation, however, buying products from non-members (i.e. from the market) cannot become the main activity of a PO: under the Derogation a PO should, first of all, aim to place on the market the products of its members. In order to safeguard the objectives of the Derogation, buying of products from non-members should remain ancillary. Buying products from non-members remains ancillary if, in normal circumstances, a PO does not buy more than 25 % of the production subject to contractual negotiations over a period of a year. There can be however exceptional situations (linked e.g. to the weather conditions, diseases) where exceeding this level, in a given period of 12 months, could be justified without undermining the ancillary character of this activity. |

|

(62) |

Natural disasters or other situations assimilated thereto resulting in the production being curtailed for a long period of time need to be assessed on a case-by-case basis. In such a situation, so long as the PO undertakes without delay the necessary steps to restore the situation prior to the force majeure event and the other requirements of the Derogation are complied with, the PO should not lose the benefit of the Derogation during that time and may cover its needs for commercialisation through the procurement of products from non-members during a reasonable period of recovery. |

|

(63) |

All conditions of the Derogation as set out in Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation shall be complied with, also with respect to quantities bought in from non-members. In particular, those volumes shall be included in the volumes subject to the contractual negotiations for the purposes of ensuring compliance with the thresholds of 15 % of the total national production for beef and veal and arable crops sectors and of 20 % of the relevant market applicable in the olive oil sector. |

|

(64) |

Example of the application of the Derogation to contractual negotiations by a PO on behalf of its members covering products of non-member producers.

|

3.3. The Significant Efficiency Test

|

(65) |

The text of Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation provides for all three sectors of olive oil, beef and veal, and arable crops that ‘[a] producer organisation fulfils the objectives mentioned in this paragraph provided that the pursuit of these objectives leads to the integration of activities and this integration is likely to generate significant efficiencies (45) so that the activities of the producer organisation overall contribute to the fulfilment of the objectives of Article 39 of the Treaty ’. |

|

(66) |

The Derogation thus requires that a PO, which carries out contractual negotiations: 1) integrate activities, and 2) that these activities be likely to generate significant efficiencies to ensure that activities of the PO overall contribute to the fulfilment of the CAP objectives. |

|

(67) |

Indeed, contractual negotiations and other joint activities by producers may have different impacts on the fulfilment of the CAP objectives. |

|

(68) |

Agreements between agricultural producers to carry out jointly certain activities can lead to efficiencies and thus economic benefits, in particular if they combine activities, skills or assets, as a means to share risk, save costs, increase investments, pool know-how, enhance product quality and variety, and launch innovation faster. Such activities can contribute to the fulfilment of the CAP objectives, possibly leading for instance to increases in productivity (e.g. because of access to better producing technologies through joint procurement activities for instance), to increased revenues for the producers (e.g. because of improvements in quality through better production or storage facilities acquired jointly) or to better availability of supplies (e.g. because of better storage or distribution systems procured or organised jointly). |

|

(69) |

Agreements between agricultural producers to carry out contractual negotiations may, however, restrict competition and ultimately impair the fulfilment of the CAP objectives. This might for example be the case if the producers conclude an agreement which fixes prices, reduces output or shares markets. Such agreements, while able to increase producers' earning, might jeopardise the fulfilment of other CAP objectives if they lead, for instance, to unreasonable prices for the consumer (because of increases in prices), to problems of availability of supplies (because of restrictions of supply) or to decreases in productivity (because the reduction in competition between the producers may decrease the incentive to increase productivity). |

|

(70) |

In situations where sales-related activities of a PO who carries out contractual negotiations on behalf of its members impair the fulfilment of certain CAP objectives, the generation of significant efficiencies can compensate these effects and ensure that the activities of the PO overall contribute to the fulfilment of the CAP objectives. Therefore, Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation require that:

|

|

(71) |

Only if the PO fulfils this test (hereinafter referred to as the ‘Significant Efficiency Test’) may the PO benefit from the Derogation. |

|

(72) |

The Significant Efficiency Test requires:

|

|

(73) |

As described above in paragraph 55, a PO can be a member of another PO (a so-called ‘second-tier PO’) which sells the output of the first PO. The contractual negotiations of the second-tier PO may benefit from the Derogation provided it complies with the conditions for the application of the Derogation as listed in paragraph 51. When assessing whether the PO complies in particular with the Significant Efficiency Test, the efficiency-enhancing activities of the first-tier PO (e.g. collection and transport of products) can be taken into account for the accounting of efficiencies in the second-tier PO/APO under the Derogation. |

|

(74) |

A PO can assess whether it complies with the Significant Efficiency Test through a simplified method provided by the EU legislator. If the PO does not comply with the conditions of the simplified method, the PO may, in certain circumstances, carry out an alternative method in order to assess whether it complies with the Significant Efficiency Test. |

3.3.1. The simplified method

|

(75) |

The third subparagraph of paragraph 1 of each of the Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation sets out a method to assess compliance with the Significant Efficiency Test (‘simplified method’). The Derogation states (48) that the Significant Efficiency Test can be met if:

|

|

(76) |

This simplified method is not applicable in a number of situations. First, it is not excluded that activities other than the ones listed in Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation create efficiencies and, in the individual case these activities create such significant efficiencies, that the activities of the producer organisation overall contribute to the fulfilment of the CAP objectives. Such a situation is not covered by the simplified method and would require a case-by-case analysis explained in paragraphs 82 to 86 below under the alternative method. |

|

(77) |

Secondly, the simplified method does not concern situations where the PO has committed itself to invest in efficiency-enhancing activities but the investment requires some time to fully materialise. Such a situation is not covered by the simplified method (which relies on activities already carried out by the PO) and would require a case-by-case analysis explained in paragraphs 82 to 86 below under the alternative method. |

|

(78) |

The simplified method requires the identification of activities among those listed in Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation and the assessment of significance of volumes and costs covered by these activities. The following four boxes present for each of the three sectors situations where such activities represent significant volumes of product concerned and significant costs of the production and placing of the product on the market so that the PO can benefit from the Derogation. This can be achieved through one activity or through the combination of several activities where none of the activities listed in the Derogation, on its own, is likely to generate significant efficiencies. Each situation requires a case-by-case analysis to make sure that the costs generated and volumes covered by these activities are sufficient to generate significant efficiencies. The following examples do not aim to exhaustively list all situations where the simplified method applies.

|

|

(79) |

In the situations of application of the simplified method of the Significant Efficiency Test identified above, it follows that a single efficiency-enhancing activity covers more than half of the volumes commercialised by the PO. The required volumes could be exceptionally lower considering small variations in the production volumes in consecutive years due to natural/weather conditions. In such a situation, the Significant Efficiency Test would be considered as fulfilled if the activity covers more than 40 % of the volumes commercialised by the PO in a given year and only for that year and when the efficiency-enhancing activity covers more than half of the volumes commercialised by the PO in other years. |

|

(80) |

In a case of force majeure (e.g. storage facilities are destroyed by a fire), even if an activity is temporally suspended, the PO can still benefit from the Derogation provided it undertakes without delay all the necessary steps to restore the situation before the force majeure event and that the other requirements of the Derogation are complied with. |

|

(81) |

Finally, if a PO does not meet the conditions set out in the simplified method, it can demonstrate through an alternative method that it still fulfils the Significant Efficiency Test. |

3.3.2. The alternative method

|

(82) |

If a PO does not comply with the conditions of the simplified method explained above, it may carry out an alternative method in order to assess whether it complies with the Significant Efficiency Test. This may be because the simplified method could not be complied with but the PO considers that nevertheless its activities fulfils the Significant Efficiency Test. It may also be because the PO is in a situation not covered by the simplified method: the PO may carry out activities not listed in the simplified method or the PO may also not yet be carrying out efficiency-enhancing activities, notably in cases where new POs are being created, where POs intend to develop new activities of integration, etc. |

|

(83) |

The alternative method requires assessing all the activities of the PO and assessing whether some activities are likely to generate significant efficiencies so that the PO overall contributes to the fulfilment of the CAP objectives. These Guidelines provide some guidance on the alternative method without covering all possible aspects of an assessment under the alternative method given its case-by-case nature. |

|

(84) |

Some activities other than the ones listed in paragraph 1(a) of Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation may create efficiencies. In such cases, it is necessary to assess on the basis of the facts of the specific situation at hand whether such activities of a PO are likely to generate significant efficiencies so that these activities overall contribute to the fulfilment of the CAP objectives (53). |

|

(85) |

The alternative method may also address a situation where a PO has committed itself to invest in efficiency-enhancing activities but the investment requires some time to fully materialise while the PO already sells to establish its presence on the market and ensure the viability of the investments it makes. Each investment needs a different period to be implemented. However, as a general rule it should not take longer than a year to be implemented, except for very significant investments (i.e. in processing or logistics facilities). |

|

(86) |

In such circumstances, the PO must demonstrate that it is financially committed to carry out the activity and that it is only a matter of time before it effectively carries out the activity due to inevitable delays in implementation (e.g. building a facility). If the PO is able to demonstrate such commitment, it is necessary to assess on the basis of the facts of the specific situation at hand whether such new activities of a PO generate significant efficiencies so that these activities overall contribute to the fulfilment of the CAP objectives (54). If the case at hand concerns activities listed in paragraph 1(a) of Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation, the assessment can be done like the assessment under the simplified method based on the type and significance (in terms of volume and costs) of the planned activities. If the case at hand concerns activities not listed in paragraph 1(a) of Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation, the assessment is case-specific. If in practice the activity ultimately cannot be carried out because of an event beyond the control of the PO, the PO may still benefit from the Derogation until a necessary delay has passed after the materialisation of this event for stopping the contractual negotiations impairing the CAP objectives (see arable crops example in Section 4.3.). |

3.4. Relations between a PO and its members

|

(87) |

The Derogation does not depend on whether there is or there is not a transfer of ownership of the product(s) concerned by the producers to the PO as it applies to POs in both situations (55). Transfer of ownership is not required in order to benefit from the Derogation. |

|

(88) |

However, the Derogation imposes two requirements as regards the relations between the PO and its members (56):

|

3.5. Production cap

|

(89) |

The Derogation is subject to quantitative limits (57). |

|

(90) |

In the sectors of beef and veal and of arable crops, the Derogation is applicable provided that the volume of the product which is covered by the contractual negotiations by a particular PO, and which is produced in any particular Member State, does not exceed 15 % of the total national production of each product referred to respectively in Article 170(1)(a) and (b) and Article 171(1)(a)-(l) of the CMO Regulation. |

|

(91) |

In the sector of olive oil, the Derogation is applicable only in case the volume of olive oil production which is covered by the contractual negotiations by a particular PO, and which is produced in any particular Member State, does not exceed 20 % of the relevant market, making a distinction between olive oil for human consumption and olive oil for other uses. These Guidelines provide details concerning the determination of the relevant market in the specific section concerning the olive oil sector. |

|

(92) |

Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation refer for purposes of setting the caps on market power to production ‘in any particular Member State’. Accordingly, if the negotiation by a PO on behalf of its members concerns supply in more Member States, the production volumes in each Member State should not exceed 15 % of the national production for beef and veal and arable crops and of 20 % of the relevant market for olive oil. |

|

(93) |

If the share is initially not more than 15 % of the national production for beef and veal or arable crops (58) or 20 % of the relevant market for the olive oil sector, but subsequently rises above that level without exceeding 20 % of the national production for beef and veal or arable crops or 25 % of the relevant market for olive oil, the Derogation provided for in Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation shall continue to apply for a period of one calendar year following the year in which the 15 % national production share for beef and veal or arable crops or 20 % of the relevant market for olive oil was exceeded. |

|

(94) |

In 2014, the European Commission published the relevant national production figures in the Official Journal of the European Union (59). Up-to-date information is available on the website of the European Commission (60). The relevant total national production data is calculated on the basis of an Olympic average (61) of the five preceding years so as to provide a stable reference value that is not subject to yearly variations. |

|

(95) |

These thresholds do not limit the capacity of the POs to negotiate on behalf of its members higher volumes. In this event, the Derogation would not apply, as this is limited to contractual negotiations that comply with the conditions explained in these Guidelines. In the case where the PO negotiates higher volumes, the PO will have to assess its activities under the other competition rules and derogations available and explained in Section 2 above. |

3.6. Obligation to notify

|

(96) |

The Derogation requires (62) the notification by the PO to the competent authorities of the Member State in which it operates of the volume of production of products concerned covered by its negotiations on behalf of its members. The respective competent authorities are determined by each Member State. |

|

(97) |

The obligation to notify the volume of production covered by the contractual negotiations to the competent authority of the Member State concerned does not imply that the concerned national authority authorises the contractual negotiations. |

3.7. Safeguards

3.7.1. Introduction

|

(98) |

Paragraph 5 of Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation sets out a safeguard mechanism, which provides competition authorities of Member States and the European Commission with powers to decide in an individual case that a particular negotiation by the PO should be either reopened or should not take place. |

|

(99) |

In case the negotiations by POs cover only one Member State, the safeguards will be applied by the competition authority of that Member State. In case the negotiations by POs cover more than one Member State, the safeguards will be applied by the European Commission. The competition authorities of the Member States and the European Commission are referred hereafter as ‘the competent competition authorities’. |

|

(100) |

As expressed in paragraph 5 of Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation the safeguard clause constitutes an exception from the Derogation and so it needs to be interpreted narrowly. |

|

(101) |

The competent competition authority can use the safeguard clause even if the quantitative thresholds (15 % of the total national production of products in beef and veal and in arable crops sectors or 20 % of the relevant market in the olive oil sector) for negotiations by POs are fully respected. |

|

(102) |

The safeguard mechanism can be applied by the competent competition authority in the following three limited situations:

|

|

(103) |

In all three situations, the action of the competent competition authority under Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation does not have the character of a sanction for infringement of competition rules, but it is rather considered as a preventive measure. |

|

(104) |

Until a decision is adopted by the competent competition authority that negotiations should be reopened or that they should not take place, negotiations carried out by POs in compliance with Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation are legal. Accordingly, before the date of such decision, negotiations by POs which meet the conditions in Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation cannot be sanctioned under general EU competition law. |

|

(105) |

Accordingly, if the PO respects the decision of the competent competition authority regarding the renegotiation or cancelling of the contractual negotiations, the PO will only be accountable for contractual negotiations which are carried on after that date. |

|

(106) |

However, following the decision by the competent competition authority that the negotiations in question should be reopened or that they should not take place, the Derogation is no longer available. As a consequence, if the PO after the date of the decision of the competent competition authority does not respect the decision and continues the negotiations or maintains the implementation of concluded contracts, proceedings under general competition law may be launched with respect to the PO's behaviour. |

3.7.2. Exclusion of competition

|

(107) |

As regards the first situation, where the competent competition authority intervenes to prevent competition from being excluded, the sales/contracts of a PO negotiated on behalf of its members may fully comply with the conditions set out in Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation, but contain clauses that restrict competition beyond what is necessary to achieve the concentration of supply, i.e. contractual negotiations (i.e. clauses not included as conditions in Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation, for instance an exclusivity clause which could have anti-competitive effects in a market with a limited number of operators all having exclusivity conditions). |

|

(108) |

Where the competent competition authority intervenes to prevent competition from being excluded, it aims at protecting rivalry between producers and competitive processes. Both actual and potential competition (64) shall be considered in such analysis. The competition could be excluded if one of its most important parameters is fully eliminated in a given relevant market; this is in particular valid for price competition (65) or competition in respect of innovation. Further elements having impact on the analysis of the elimination of competition are inter alia: market shares in the broader context of the analysis of the actual competitors' capacity to compete and their incentives to do so (66); reduction of competition brought about by the contractual negotiations concerned; capacity to implement and maintain price increases; barriers to new entry. For further details concerning the assessment of the exclusion of competition see (by analogy) Section 2 of the Guidelines on the application of Article 81(3) of the Treaty [currently Article 101(3) TFEU] (67). |

|

(109) |

If, however, the supply contracts of a PO concluded on behalf of its members do meet the conditions in Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation and these contracts do not contain clauses that would restrict competition beyond what is necessary to allow the concentration of supply foreseen by those articles, they do not infringe Article 101 TFEU. |

3.7.3. Smaller relevant product market with anti-competitive effects

|

(110) |

As for the second situation, the competent competition authority may decide that negotiations should be reopened or should not take place if it finds:

This does not apply to the sector of olive oil, where the relevant market is not defined in Article 169 of the CMO Regulation. |

3.7.4. CAP objectives are jeopardised

|

(111) |

The third situation, where the competent competition authority can intervene, is linked to its findings that the CAP objectives are jeopardised by further integration activities of POs. This situation could materialise in cases where a PO has made a self-assessment based on the simplified method. Under that method, there is an assumption that if the relevant criteria are met, the PO's activities overall contribute to the fulfilment of CAP objectives. A competition authority may find that in practice this is not the case even if the criteria are met. |

4. SPECIFIC PROVISIONS ON THE CONCERNED SECTORS

4.1. Olive oil

4.1.1. Examples of application of the derogation to the olive oil sector

|

(112) |

This section of the Guidelines addresses the practical application of the specific rules of the CMO Regulation in the olive oil sector, by way of the examples below. |

|

(113) |

Example of the assessment under Article 169 of the CMO Regulation of a PO active in the olive oil sector where the Derogation is applicable.

|

|

(114) |

Example of the assessment under Article 169 of the CMO Regulation of a PO active in the olive oil sector where the Derogation is applicable.

|

|

(115) |

Example of the assessment under Article 169 of the CMO Regulation of a PO active in the olive oil sector where the Derogation is not applicable.

|

4.1.2. Identification of the relevant market

|

(116) |

The Derogation requires identifying the relevant product and geographic markets for the wholesale sale of olive oil so that POs can identify whether they comply with the market share ceiling set by the Derogation (68). |

|

(117) |

Relevant markets need to be assessed on a case-by-case basis and the European Commission has provided guidance on how to identify relevant markets in its Notice on the definition of the relevant market (69). It is not possible for the European Commission to provide precise definitions of relevant markets for the olive oil sector but, in order to help producers implement the Derogation, these Guidelines provide some guidance specific to the sector based on the information available to the European Commission at the time of adoption of these Guidelines (70). Relevant markets may evolve in time due to, inter alia, market developments. |

|

(118) |

The issue is to identify the relevant product and geographic markets for the wholesale sale of olive oil. In that market, sellers include essentially producers and traders while buyers include essentially traders, manufacturers, retailers, industrial customers and customers in the hotel and restaurant sector. |

4.1.2.1.

|

(119) |

First of all, the relevant product market for olive oil would appear to be distinct from the product markets for other edible oils considering, inter alia, the differences in characteristics, prices and purposes of these products. Furthermore, it may not be necessary to identify separate markets for the different types of olive oil (extra virgin, virgin and other olive-based oils (71)) having regard to the large degree of substitution between these categories. Also, taking into account the organisation of sales channels it may be appropriate to identify three separate markets:

Finally, it cannot be excluded that in the market of olive oil supplied to retailers, the supply of private labels and branded products form different product markets. |

|

(120) |

The above-described common elements of market segmentation do not exclude the identification of narrower product markets. |

4.1.2.2.

|

(121) |

From a geographical point of view the relevant market for supply of olive oil would seem not to be narrower than national and would be possibly EEA wide with respect to all three sales channels, namely supply of olive oil to retail customers, industry and the hotel and restaurant sector. |

4.2. Beef and veal sector

4.2.1. Examples of application of the derogation to the beef and veal sector

|

(122) |

This section of the Guidelines addresses the practical application of the specific rules of the CMO Regulation in the beef and veal sector by way of the examples below. |

|

(123) |

Example of the assessment under Article 170 of the CMO Regulation of a PO active in the beef and veal sector where the Derogation is applicable.

|

|

(124) |

Example of the assessment under Article 170 of the CMO Regulation of a PO active in the beef and veal sector where the Derogation is applicable:

|

|

(125) |

Example of the assessment under Article 170 of the CMO Regulation of a PO active in the beef and veal sector where the Derogation is not applicable.

|

4.3. Arable crops

4.3.1. Examples of application of the derogation to the arable crops sector

|

(126) |

This section of the guidelines addresses the practical application of the specific rules of the CMO Regulation in the arable crops sector by way of the examples below. |

|

(127) |

Example of the assessment under Article 171 of the CMO Regulation of a PO active in the arable crops sector where the Derogation is applicable:

|

|

(128) |

Example of the assessment under Article 171 of the CMO Regulation of a PO active in the arable crops sector where the Derogation is applicable.

|

|

(129) |

Example of the assessment under Article 171 of the CMO Regulation of a PO active in the arable crops sector where the Derogation is not applicable.

|

(1) The Guidelines on the application of the specific rules laid down in Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation for the olive oil, beef and veal and arable crops sectors (thereinafter ‘the Guidelines’).

(2) The ‘CMO Regulation’ is the Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 December 2013 establishing a Common Organisation of the Markets in agricultural products and repealing Council Regulations (EEC) No 922/72, (EEC) No 234/79, (EC) No 1037/2001 and (EC) No 1234/2007 (OJ L 347, 20.12.2013, p. 671).

(3) Article 206 paragraph 3 of the CMO Regulation: ‘the Commission shall, where appropriate, publish guidelines to assist the national competition authorities, as well as undertakings’.

(4) In particular, Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation apply exclusively to a specific category of POs and APOs, which are recognised by Member States under Articles 152(1) and 156(1) of the CMO Regulation, i.e. these rules do not concern any other category of PO or APO. For further details see paragraph 53 below.

(5) The Court of Justice of the European Union here refers to the Court of Justice and the General Court.

(6) Judgment in Maizena, 139/79, EU:C:1980:250, paragraph 23; Judgment in Germany v Council, C-280/93, EU:C:1994:367, paragraph 61.

(7) Article 101 TFEU:

‘1. The following shall be prohibited as incompatible with the internal market: all agreements between undertakings, decisions by associations of undertakings and concerted practices which may affect trade between Member States and which have as their object or effect the prevention, restriction or distortion of competition within the internal market, and in particular those which:

|

(a) |

directly or indirectly fix purchase or selling prices or any other trading conditions; |

|

(b) |

limit or control production, markets, technical development or investment; |

|

(c) |

share markets or sources of supply; |

|

(d) |

apply dissimilar conditions to equivalent transactions with other trading parties, thereby placing them at a competitive disadvantage; |

|

(e) |

make the conclusion of contracts subject to acceptance by the other parties of supplementary obligations which, by their nature or according to commercial usage, have no connection with the subject of such contracts. |

2. Any agreements or decisions prohibited pursuant to this Article shall be automatically void.

3. The provisions of paragraph 1 may, however, be declared inapplicable in the case of:

|

— |

any agreement or category of agreements between undertakings, |

|

— |

any decision or category of decisions by associations of undertakings, |

|

— |

any concerted practice or category of concerted practices, |

which contributes to improving the production or distribution of goods or to promoting technical or economic progress, while allowing consumers a fair share of the resulting benefit, and which does not:

|

(a) |

impose on the undertakings concerned restrictions which are not indispensable to the attainment of these objectives; |

|

(b) |

afford such undertakings the possibility of eliminating competition in respect of a substantial part of the products in question.’ |

(8) Article 102 TFEU:

‘Any abuse by one or more undertakings of a dominant position within the internal market or in a substantial part of it shall be prohibited as incompatible with the internal market insofar as it may affect trade between Member States.

Such abuse may, in particular, consist in:

|

(a) |

directly or indirectly imposing unfair purchase or selling prices or other unfair trading conditions; |

|

(b) |

limiting production, markets or technical development to the prejudice of consumers; |

|

(c) |

applying dissimilar conditions to equivalent transactions with other trading parties, thereby placing them at a competitive disadvantage; |

|

(d) |

making the conclusion of contracts subject to acceptance by the other parties of supplementary obligations which, by their nature or according to commercial usage, have no connection with the subject of such contracts.’ |

(9) Commission Notice — Guidelines on the effect on trade concept contained in Articles 81 and 82 of the Treaty (OJ C 101, 27.4.2004, p. 81).

(10) An economic activity is defined as an activity consisting in offering goods and services on a given market. For details see: e.g. judgment in Commission v Italy, 118/85, EU:C:1987:283, paragraph 7. An undertaking is an entity engaged in an economic activity.

(11) For further details and background see judgement in Oude Luttikhuis, C-399/93, EU:C:1995:434, paragraphs 10-16. See also the Opinion of Advocate General Tesauro in this case, EU:C:1995:277, paragraphs 29-30.

(12) For details see: Commission notice on the definition of the relevant market for the purposes of Community competition law (OJ C 372, 9.12.1997, p. 5).

(13) Judgment in United Brands, 27/76, EU:C:1995:277, paragraph 65.

(14) Exclusionary abuses are those practices not based on normal business performance which seek to harm the competitive position of the dominant company's competitors, or to exclude them from the market altogether, ultimately causing harm to the customers (such as refusals to supply, to grant a licence, predatory prices). Exploitative abuses, on the other hand, involve the attempt by a dominant company to exploit the opportunities provided by its market strength in order to harm customers directly, for instance by imposing excessive prices.

(15) For details see: Commission Notice — Guidelines on the effect on trade concept contained in Articles 81 and 82 of the Treaty (OJ C 101, 27.4.2004, p. 81).

(16) See, inter alia, judgment in Oude Luttikhuis EU:C:1995:434, paragraph 12; judgment in Dansk Landbrugs Grovvareselskab (DLG), C-250/92, EU:C:1994:413, e.g. paragraph 32.

(17) E.g. judgment in Dansk Landbrugs Grovvareselskab (DLG), EU:C:1994:413, paragraph 35; judgment in Oude Luttikhuis, EU:C:1995:434, paragraph 14.

(18) Commission Regulation (EU) No 1218/2010 of 14 December 2010 on the application of Article 101(3) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union to certain categories of specialisation agreements (OJ L 335, 18.12.2010, p. 43).

(19) For details concerning the definitions see Article 1 of the Specialisation Block Exemption.

(20) Articles 2, 3 and 4 of the Specialisation Block Exemption.

(21) Article 4 of the Specialisation Block Exemption.

(22) Judgement in Frubo, 71/74, EU:C:1975:61; judgment of 14 May 1997, Florimex, T-70/92 and T-71/92, EU:T:1997:69; judgment in Oude Luttikhuis EU:C:1995:434; judgment of 13 December 2006, FNCBV v Commission, T-217/03 and T-245/03, EU:T:2006:391.

(23) The Guidelines apply to the supply contracts negotiated by POs on behalf of their members irrespective of the level of integration they entail with the exception of operations constituting a concentration within the meaning of Article 3 of Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 of 20 January 2004 on the control of concentrations between undertakings (the Merger Regulation, OJ L 24, 29.1.2004, p. 1) as would be the case, for example, with joint ventures performing on a lasting basis all the functions of an autonomous economic entity.

(24) The following live cattle intended for slaughtering are covered by Article 170 of the CMO Regulation:

|

(a) |

cattle of the subgenus Bibos or of the subgenus Poephagus of a weight exceeding 80 kg but not exceeding 160 kg for slaughter within CN code ex 0102 29 21; |

|

(b) |

cattle of the subgenus Bibos or of the subgenus Poephagus of a weight exceeding 160 kg but not exceeding 300 kg for slaughtering within CN code ex 0102 29 41; |

|

(c) |

cattle of the subgenus Bibos or of the subgenus Poephagus of a weight exceeding 300 kg for slaughtering within CN code ex 0102 29 51; |

|

(d) |

cows for slaughter within CN code ex 0102 29 61; and |

|

(e) |

other cattle for slaughtering within CN code ex 0102 29 91. |

Cattle for fattening and further slaughtering are not covered by the CN codes listed in Article 170 of the CMO Regulation.

(25) The following products not intended for sowing and in the case of barley not intended for malting are covered by Article 171 of the CMO Regulation:

|

(a) |

common wheat falling within CN code ex 1001 99 00; |

|

(b) |

barley falling within CN code ex 1003 90 00; |

|

(c) |

maize falling within CN code 1005 90 00; |

|

(d) |

rye falling within CN code 1002 90 00; |

|

(e) |

durum wheat falling within CN code 1001 19 00; |

|

(f) |

oats falling within CN code 1004 90 00; |

|

(g) |

triticale falling within CN code ex 1008 60 00; |

|

(h) |

rapeseed falling within CN code ex 1205; |

|

(i) |

sunflower seed falling within CN code ex 1206 00; |

|

(j) |

soya beans falling within CN code 1201 90 00; |

|

(k) |

field beans falling within CN codes ex 0708 and ex 0713; |

|

(l) |

field peas falling within CN codes ex 0708 and ex 0713. |

(26) See Section 2.4 of these Guidelines for the relationship between Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO with Articles 101 and 102 TFEU.

(27) See recital 139 of the CMO Regulation.

(28) Paragraph 2(d) of Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation.

(29) Exit of a contract may be required for instance in the case of a crop failure caused e.g. by weather conditions or diseases.

(30) The commercialisation strategy of the PO may require planning the production of the members to ensure the delivery of products by members to the PO in line with the commercialisation strategy. Production planning takes place before the production cycle starts, when it can still influence the amount of output the PO needs. The situation where production planning forms part of the commercialisation strategy of a PO is covered by the Derogation. This situation however differs from the situation where production planning is carried out outside such strategy, for example where a PO would coordinate joint planning with another PO, or when a PO would coordinate joint planning with its members for the production that those members sell outside of the PO. In the latter case, production planning may be covered by other derogations from competition rules under the CMO Regulation or by general competition rules.

(31) The commercialisation strategy of the PO may require determining the calendar and volumes of production to be commercialised by the PO. This may entail the storage of some production by the PO or decisions by the PO to postpone the sale of certain volumes due to market conditions. Such decisions as they form part of the commercialisation strategy of the PO are covered by the Derogation. The Derogation does not cover, however, any agreement by the PO and/or its members about products that are not commercialised by the PO.

(32) The commercialisation strategy of the PO may require the exchange of commercially sensitive information between members in order for instance to identify the capacity for members to increase deliveries to the PO. Accordingly, the situation where the exchange of commercially sensitive information forms part of the commercialisation strategy of PO would be covered by the Derogation. This situation however differs from the situation where the exchange of commercially sensitive information is carried out outside such strategy. This would be the case for instance if the information relates for example to the volumes the producers sell outside of the PO. In the latter case, the exchange of commercially sensitive information may be covered by other derogations from competition rules under the CMO Regulation or by general competition rules.

(33) See paragraph 2(a) of Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation.

(34) See paragraph 2(b) of Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation.

(35) This is only an overview of the most important conditions; specific elements will be dealt with in detail in the following sections and a complete list can be found in the respective legislation, namely Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation.

(36) OJ C 11, 14.1.2011, p. 1.

(37) See paragraphs 150 to 293 of the Guidelines on the applicability of Article 101 TFEU to horizontal cooperation agreements.

(38) Details concerning joint commercialisation agreements in paragraphs 225 to 257 of the Guidelines on the applicability of Article 101 TFEU to horizontal cooperation agreements.

(39) OJ C 101, 27.4.2004, p. 97.

(40) Article 152(1) of the CMO Regulation:

‘Producer organisations

1. Member States may, on request, recognise producer organisations, which:

|

(a) |

are constituted, and controlled in accordance with point (c) of Article 153(2), by producers in a specific sector listed in Article 1(2); |

|

(b) |

are formed on the initiative of the producers; |

|

(c) |

pursue a specific aim which may include at least one of the following objectives:

|

(41) A PO makes efforts to effectively sell products; i.e. it does not only carry out a joint marketing strategy but also makes sales offers and concludes sales with customers/buyers with respect to the products of its members.

(42) Paragraph 1, first subparagraph of Articles 169, 170 and171 of the CMO Regulation.

(43) Paragraph 2(d) of Articles 169, 170 and171 of the CMO Regulation.

(44) A non-member can be either a producer who is not a member of the PO or a trader. The non-members do not directly participate in the contractual negotiations carried out by a PO on behalf of its members, i.e. a PO negotiates independently from non-members. The non-member products are bought by a PO from non-members separately; these negotiations with non-members do not form part of the contractual negotiations and thus do not benefit from the Derogation.

(45) Emphasis added.

(46) Outsourcing of activities by a recognised PO however needs to comply with Article 155 of the CMO Regulation. It must be permitted in advance by Member States. Outsourcing of production is not allowed. A PO must remain responsible for ensuring the carrying out of the outsourced activity and for overall management, control and supervision of the commercial arrangement for the carrying out of the activity. Further details concerning outsourcing will be set out in a Commission Delegated Regulation to be adopted.

(47) As this efficiency test relies on the fulfilment of the CAP objectives in the light of the specific legal basis provided by Articles 39 and 42 TFEU for competition rules in the production and trade of agricultural products, it is different from any efficiency test that would be applied in competition enforcement in other sectors.

(48) Paragraph 1, subparagraph 3 point (a) and (b) of Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation.

(49) These activities are:

|

(i) |

joint distribution, including joint selling platform or joint transportation; |

|

(ii) |

joint packaging, labelling or promotion; the first two activities are only considered for the olive oil sector; |

|

(iii) |

joint organising of quality control; |

|

(iv) |

joint use of equipment or storage facilities; |

|

(v) |

joint processing; this activity is only considered for the olive oil sector; |

|

(vi) |

joint management of waste directly related to the production of the product; this activity is only considered for the olive oil and beef and veal sectors; |

|

(vii) |

joint procurement of inputs. |

(50) In Greece, Italy and Spain the costs of fertilisers represented on average 18 % of the operating costs (farms specialised in olive oil production) in 2010, pesticides 14 % and fuel and energy costs 27 %, based on the data of the report ‘EU olive oil farms report based on FADN data’, http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/rica/pdf/Olive_oil%20_report2000_2010.pdf, pp. 57-76.

(51) In the EU-27 the costs of feed represented 41 % of the operating costs in 2011 for breeders and fatteners, the cost of the purchased animals 22 % and fuel and energy costs 7 %, based on the report ‘EU beef farms report 2012 based on FADN data’, http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/rica/pdf/beef_report_2012.pdf, p. 69.

(52) In the EU-27 the costs of fertilisers represented, for example for wheat, durum wheat, barley and maize, on average 24 % of the operating costs in 2011, pesticides 11 % and fuel and energy costs 17 %, based on the data of the report ‘EU cereal farms report 2013 based on FADN data’, http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/rica/pdf/cereal_report_2013_final.pdf, pp. 26-79.

(53) If the elements of the simplified method in terms of volume and costs as described above are complied with, it is likely that the Significant Efficiency Test is fulfilled in such a situation as well. If not, the Significant Efficiency Test would need to be assessed on the basis of the facts of the specific situation at hand in order to ensure that activities of a PO generate significant efficiencies so that these activities overall contribute to the fulfilment of the CAP objectives.

(54) See footnote 53.

(55) Paragraph 2(a) of Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation.

(56) Paragraph 2(e) and (f) of Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation.

(57) Paragraph 2(c) of Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation.

(58) Article 170(1)(a) and (b) and Article 171(1)(a)-(l) of the CMO Regulation.

(59) Olive oil: OJ C 256, 7.8.2014, p. 4.

Arable crops: OJ C 256, 7.8.2014, p. 1.

Beef and veal: OJ C 256, 7.8.2014, p. 3.

(60) Olive oil: http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/olive-oil/legislation/index_en.htm

Beef and veal: http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/beef-veal/policy-instruments/index_en.htm

Arable crops: http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/cereals/legislation/index_en.htm

(61) The Olympic average is calculated based on the last 5 years production data, removing the high and low years, and averaging the remaining 3 years.

(62) Paragraph 2(g) of Articles 169, 170 and 171 of the CMO Regulation.

(63) This possibility applies only to the beef and veal and arable crops sectors, i.e. not to the olive oil sector, where only conditions under a. or c. are relevant.

(64) E.g. Judgment of 28 February 2002, T-395/94, Atlantic Container Line v Commission, EU:T:2002:49, paragraph 330.

(65) E.g. Judgment in Metro v Commission, 26/76, EU:C:1977:167, paragraph 21: ‘… However, although price competition is so important that it can never be eliminated it does not constitute the only effective form of competition or that to which absolute priority must in all circumstances be accorded. The powers conferred upon the Commission under Article 85(3) show that the requirements for the maintenance of workable competition may be reconciled with the safeguarding of objectives of a different nature and that to this end certain restrictions on competition are permissible, provided that they are essential to the attainment of those objectives and that they do not result in the elimination of competition for a substantial part of the Common Market. …’.

(66) It should be recalled in this context that the entities benefiting from the Derogation are subject to market power thresholds of 15 % of the national production for beef and veal and arable crops as well as of 20 % of the relevant market for olive oil.

(67) Communication from the Commission — Notice — Guidelines on the application of Article 81(3) of the Treaty [currently Article 101(3) TFEU], OJ C 101, 27.4.2004, p. 97.

(68) See Section 3.5 on the Production cap.

(69) Commission notice on the definition of the relevant market for the purposes of Community competition law (OJ C 372, 9.12.1997, p. 5).

(70) This includes previous investigations by competition authorities (DG Competition of the European Commission and Spanish NCA cases) as well as information collected by the European Commission from operators.

(71) Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 29/2012 of 13 January 2012 on marketing standards for olive oil (OJ L 12, 14.1.2012, p. 14) (as amended).

ANNEX I

ANNEX II