|

8.3.2012 |

EN |

Official Journal of the European Union |

C 70/9 |

2012 Joint Report of the Council and the Commission on the implementation of the Strategic Framework for European cooperation in education and training (ET 2020)

‘Education and Training in a smart, sustainable and inclusive Europe’

2012/C 70/05

1. EDUCATION AND TRAINING IN THE CONTEXT OF THE EUROPE 2020 STRATEGY

In 2009, the Council drew up the Strategic Framework for European Cooperation in education and training (‘ET 2020’) (1). Since then, the economic and political context has changed, creating new uncertainties and constraints. The European Union had to take further action to stem the worst financial and economic crisis in its history and, in response, has agreed on a strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth: Europe 2020.

Education and training play a crucial role in this strategy, in particular within the Integrated Guidelines, Member State National Reform Programmes and the Country-specific Recommendations (CSR) issued to guide Member State reforms. One of the five Europe 2020 headline targets concerns early school leaving and tertiary or equivalent attainment.

The 2012 Annual Growth Survey (AGS) stresses that: the focus of Europe 2020 needs to be simultaneously on: reform measures having a short-term growth effect; and on setting the right growth model for the medium-term. Education and training systems have to be modernised to reinforce their efficiency and quality and to equip people with the skills and competences they need to succeed on the labour market. This will boost people's confidence to be able to stand up to current and future challenges. It will help to improve Europe's competitiveness and generate growth and jobs. The 2012 AGS also calls for a particular focus on young people, who are among the groups worst affected by the crisis.

A key instrument to modernise education and training, ET 2020 can make a major contribution to achieving Europe 2020’s objectives. But to do this, ET 2020 must be adjusted by updating its working priorities, tools and governance structure.

Based on an assessment of progress made in key policy areas in the last three years, this draft Joint Report proposes new working priorities for the period 2012-2014 geared to mobilise education and training to support Europe 2020.

The draft Joint Report also sets out a number of options to adjust the governance of ET 2020 to ensure that it contributes to Europe 2020.

The draft Joint Report is accompanied by two Commission Staff Working Documents (2). They take stock of the situation in individual countries and key thematic areas and draw on National Reports provided by Member States as well as other information and data.

2. PROGRESS AND CHALLENGES IN PRIORITY AREAS

2.1. Investment and reforms in education and training

Currently, all areas of public budgets are under scrutiny, including education and training. Most Member states have difficulties in maintaining current levels of expenditure, let alone increasing it.

However, research suggests that improving educational achievements can yield immense long-term returns and generate growth and jobs in the European Union. Reaching the European benchmark of less than 15 % low achievers in basic skills by 2020, for example, could generate enormous long-term aggregate economic gains for the European Union. (3)

This contrasts with the fact that — even before the crisis — spending in some Member States was rather low, close to or below 4 % of GDP, while the European Union average stood at almost 5 % of GDP — below the level of 5,3 % in the United States.

Cuts in education budgets risk to undermine the economy’s growth potential and competitiveness. In the 2012 AGS, the Commission confirmed its conviction that, when consolidating their public finance, Member States should prioritise expenditure on growth-enhancing policies, such as education and training.

There is no clear pattern in the way Member States have addressed education budgets in their responses to the crisis. They have adopted a broad range of measures to curb expenditure: many have cut staff costs (BE nl, BG, EL, ES, FR, HU, IE, LV, PT, RO, SI) or provisions for infrastructure, maintenance and equipment (BE nl, BG, IE, RO).Some have reduced educational provision in pre-primary (for 2 year-old children in FR), postponed or slowed down the implementation of reforms (BG), or taken other measures such as reductions in student financial support (BE nl, IE, PT).

These trends warrant policy attention. ET 2020 should be used to discuss how best to invest in education and training, in ways that combine efficiency and effectiveness with growth-friendly impact. Smart investment goes hand in hand with smart policy reforms that improve the quality of education and training. A broad reflection involving all stakeholders could be used to identify efficient ways of sharing the financial burden and finding new sources of finance.

2.2. Early School Leaving

The crisis is severely affecting prospects for young people. Youth unemployment has risen from 15,5 % in 2008 to 20,9 % in 2010, while the share of 15 to 24 year olds neither in education, employment or training rose by two percentage points. 53 % of early school leavers were unemployed.

Against this backdrop, the Europe 2020 target to reduce the share of 18-24 year olds having left education and training prematurely to less than 10 % by 2020 becomes particularly critical. If current trends continue, this target will not be reached. In 2010, despite some progress, the rate of ESL still averaged 14,1 % across the European Union, with considerable differences between countries. Evidence shows that boys are more at risk (16 %) of dropping out than girls (12,6 %).

Bringing the ESL rate down below 10 % is a difficult challenge. The 2011 Council Recommendation (4) on policies to reduce ESL calls on Member States to implement coherent, comprehensive and evidence-based strategies, in particular those Member States that received a CSR in this area in 2011 (AT, DK, ES, MT). But countries that are close to the target (DK, IE, HU, NL, FI) should also increase efforts to make further progress and/or overcome stagnation. All Member States should implement targeted measures to reach young people at risk of dropping out.

With some notable exceptions, Member State policies are not based sufficiently on up-to-date data and an analysis of the causes and incidence of ESL. Only a few countries take a systematic approach to collecting, monitoring and analysing data on ESL (EE, FR, HU, IT, LU, NL, UK).

Prevention and early intervention are key to tackling the problem; however, Member States devote too little attention to prevention. Partial, compensatory measures, such as second-chance education, albeit important, are insufficient to address the root-causes of the problem. There should be stronger focus on preventive and early intervention measures in the contexts of teacher education, continuing professional development and quality early childhood education and care.

Increasing the provision of high-quality initial Vocational Education and Training (VET) that is tailored to the needs of young people, including as blended learning which links VET and general secondary education, can help reduce ESL. It provides a different, and for some learners more motivating, education path. In parallel, however, there is a serious need to reduce the level of drop-out from VET provision.

Many countries use a broad range of measures to tackle different aspects of ESL, but they do not necessarily add up to a comprehensive strategy. Stakeholders from different education sectors and policy areas, such as youth policy, social and employment services, should work together more closely. Cooperation with parents and local communities should be intensified. School-business cooperation, non-curricular and out-of-school activities and ‘youth guarantees’ are possible ways to involve different local actors.

As Europe is not on track to achieve the headline target, there is an urgent need to strengthen the policy approach. In the next years, work on ESL, guided by the June 2011 Council Recommendation, needs to be one of the top priorities under ET 2020.

Early School Leaving: 2010 rates (5) and national targets

— Performance in 2010 (%)

— National target for 2020 (%)

|

|

9,5 |

11 |

5,5 |

10 |

10 |

9,5 |

8 |

9,7 |

15 |

9,5 |

15 16 |

10 |

13,4 |

9 |

10 |

10 |

29 |

8 |

9,5 |

4,5 |

10 |

11,3 |

5 |

6 |

8 |

10 |

: |

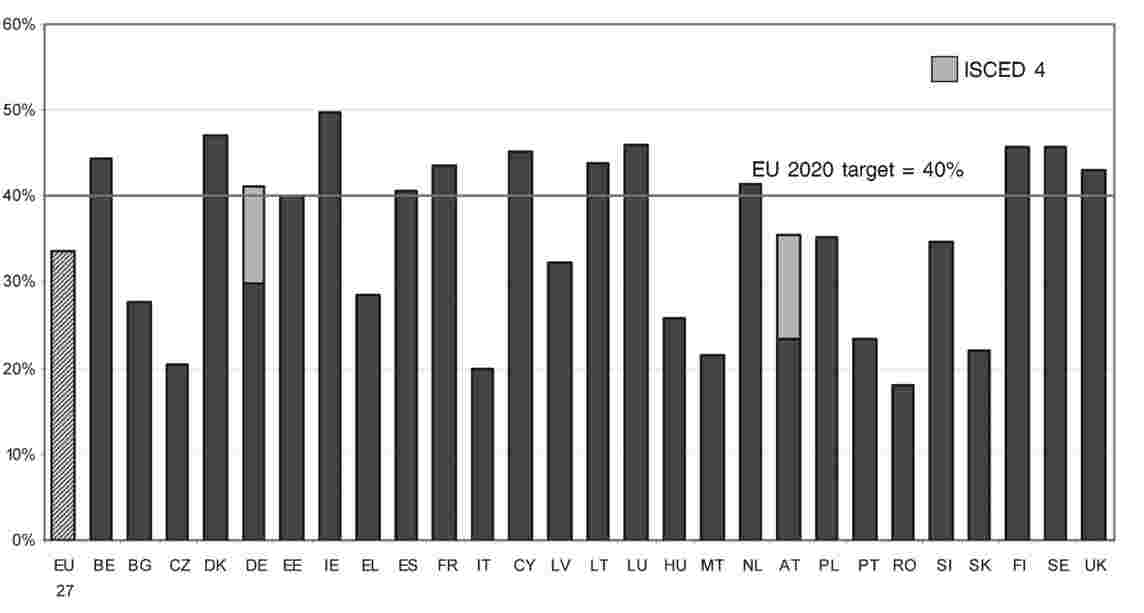

2.3. Tertiary or equivalent education attainment

To emerge stronger from the crisis, Europe needs to generate economic growth based on knowledge and innovation. Tertiary or equivalent education can be a powerful driver in this respect. It provides the highly-qualified workforce that Europe needs to advance research and development and equips people with the skills and qualifications they need in the knowledge-intensive economy.

Europe 2020 set the Headline Target to increase the share of 30-34 year olds with a tertiary or equivalent degree to 40 % by 2020. In 2010, the average level of tertiary or equivalent education attainment of this age group was 33,6 %. Attainment rates, national targets and levels of ambition vary considerably across countries.

To reach the target, Member States should continue their reform efforts, as agreed in the Council conclusions of 28 November 2011 on the modernisation of higher education (6) and in line with the CSRs on this issue issued to five countries (BG, CZ, MT, PL, SK).

Reforms should address the challenge of increasing the number of graduates, while maintaining and enhancing the quality and relevance of education and research.

Alongside efforts to optimise funding and governance, the participation of under-represented groups should be increased in all Member States, including people from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds or geographical locations, ethnic groups and people with disability.

Access to higher education for adult learners should be eased. There is considerable potential to help those already in the labour force enter or re-enter higher education, to promote the transition from vocational education and training to higher education, and to improve the recognition of prior learning acquired in non-formal contexts.

Too many students drop out of higher education. Guidance and counselling on education and career paths, which will help maintain the motivation to complete studies, are critical to prevent and reduce the risk of drop-outs.

Attracting talented foreign students can be another way to increase participation and attainment.

Modernising higher education will contribute significantly to achieving the objectives of Europe 2020. It therefore needs to be another top priority for exchanges in the next period under ET 2020, including implementation of the 2011 Higher Education Communication and the Council Conclusions on the modernisation of Europe’s higher education systems.

Tertiary or equivalent education attainment: 2010 levels and national targets (7)

— Performance in 2010 (%)

— National target for 2020 (%)

|

|

47 |

36 |

32 |

40 |

42 |

40 |

60 |

32 |

44 |

50 |

26 27 |

46 |

34 36 |

40 |

40 |

30,3 |

33 |

45 |

38 |

45 |

40 |

26,7 |

40 |

40 |

42 |

40 45 |

: |

2.4. Lifelong learning strategies

For the majority of Europeans, lifelong learning (LLL) is not a reality. While participation in education and training during the early years of life has increased, recent data on the number of adults aged 25-64 participating in LLL show a slight downwards trend. The current level of 9,1 % (2010) is far below the ET 2020 benchmark of 15 % to be reached by 2020.

This weak performance is especially serious given the crisis. Unemployed young people and low-skilled adults need to be able to rely on education and training to give them a better chance in the labour market. Not investing in their competences weakens their chances to get back into employment and limits Europe’s potential to create growth and jobs. At the same time, we should also focus on the contribution of education to economic development of Europe through up-skilling of the labour force and integrating adult learning plans for economic development and innovation.

LLL is a continuous process that can last throughout a person’s entire life, from quality early-childhood education to post-working age. Moreover, learning takes place also outside formal learning contexts, in particular at the workplace.

Recently, some progress has been made on the European benchmarks of reducing the share of low-achievers in basic skills (20 % in 2009 vs. a benchmark of less than 15 % by 2020) and in increasing participation in early childhood education (92 % in 2009 vs. a benchmark of 95 % by 2020); however, efforts on both issues need to continue.

Obstacles to LLL persist, such as limited learning opportunities inadequately tailored to the needs of different target groups; a lack of accessible information and support systems; and insufficiently flexible learning pathways (e.g. between VET and higher education). The problems are often exacerbated by the fact that potential learners have low socio-economic and prior educational status.

Overcoming these obstacles requires more than piecemeal reforms in specific education sectors. Although Member States acknowledged this need a decade ago, the problem of segmentation persists. Today only a few countries have a comprehensive strategy, supporting a good educational continuum, in place (AT, CY, DK, SI, UK SC).

On the positive side, using tools such as the European and national qualification frameworks (BE nl, CZ, DK, EE, FI, FR, IE, LT, LV, LU, MT, NL, PT, UK); mechanisms to validate non-formal and informal learning (DE, DK, ES, FI, FR, LU, NL, PT, RO, SE, UK) and lifelong guidance policies (AT, DK, DE, EE, ES, FI, FR, HU, IE, LT, LU, LV, NL) show that barriers for cooperation between education sectors can be overcome.

Education and training systems should provide LLL opportunities for all. Member States should screen their systems to detect obstacles to LLL. In cooperation with the social partners and other key stakeholders, they should put comprehensive strategies in place and take measures promoting access to LLL, in line with European commitments and drawing on transparency tools and frameworks (European Qualifications Framework (8), ECVET/ECTS (9), EQAVET, Key Competences Framework (10)). The emphasis should be on ensuring basic skills for all and on better integrating LLL provision, particularly to stimulate the participation of low-skilled adults.

2.5. Learning mobility

Mobility strengthens Europe’s foundation for future knowledge-based growth and ability to innovate and compete at international level (11). It strengthens peoples’ employability and personal development and is valued by employers. Education institutions, education and training systems and businesses equally benefit from the learning experience, personal contacts and networks that result from mobility. Promoting transnational learning mobility is an excellent example of European added value.

However, current levels of mobility do not reflect its value. Roughly 10 %-15 % of higher education graduates spend a proportion of their studies abroad, where the added value of mobility is most widely acknowledged; but only about 3 % of graduates from initial VET do so. More work is needed to promote mobility in vocational education and training. Limited financial resources and inadequate language knowledge are a brake to learning mobility. Mobility is not always recognised or validated. There is often a lack of information on available opportunities. Furthermore, the specific situation of learners with special needs (e.g. disabilities) is insufficiently addressed.

Most countries promote primarily the mobility of learners. While some countries (BG, IE, MT, SE, BE nl, DE, EE, EL, ES, FI, NL, RO, LT, FR) also include other groups, such as teachers or apprentices, there is scope to do much more here at both national and European level.

European funding programmes have a key role to play. As part of the new Multiannual Financial Framework for 2014-2020, the Commission has proposed to nearly double the number of beneficiaries in the future education and training programme, from 400 000 to almost 700 000 per year.

However, financial programmes need to go hand in hand with policy reforms. The Council adopted a new benchmark on learning mobility in November 2011 (20 % for higher education, 6 % for initial VET by 2020). This political commitment should be taken forward by implementing the Council Recommendation ‘Youth on the move — promoting the learning mobility of young people’ and by making full use of European transparency tools, such as EQF, ECTS/ECVET and Europass (12).

2.6. New skills and jobs

The crisis has spurred changes in the demand for skills. Demand for jobs requiring low qualifications is decreasing, and tomorrow’s knowledge-based industries require increasing levels of qualification. A recent forecast (13) expects the share of highly qualified jobs to increase by almost 16 million, from 29 % (2010) to 35 % of all jobs in 2020. Conversely, the share of jobs demanding a low level of skills is expected to fall by around 12 million, from 20 % to less than 15 %. Some countries already face bottlenecks for highly qualified jobs. This will be aggravated by the impact of demographic ageing when the workforce starts to shrink after 2012. CSRs on improving skills for the labour market and on specific support to low-skilled workers have been addressed to a number of Member States (BG, CY, CZ, EE, PL, SI, SK, UK).

Member States have made progress on implementing methods, tools, and approaches to anticipate and assess the demand for skills, mismatches and graduate employability. Many focus on key sectors such as ICT or health.

However, only a few countries (AT, DE, FR, IE, PL, UK) have a coordinated approach for disseminating results among key actors. Institutional mechanisms are often developed at regional or at sectoral levels, but tend to reflect and to reproduce the segmentation of education and training systems.

Countries address the responsiveness of education and training provisions to labour market developments through partnerships with key stakeholders (EE, FI, SE); quality assurance mechanisms; and initiatives targeting competences required on the labour market, notably literacy, maths, science and technology (AT, BE nl, DE, FR, PL, LT, IE), languages, digital competences and sense of initiative and entrepreneurship (ES, EE, BG, LT, FR).

Encouraging boys and girls to choose careers in sectors where they are under-represented will reduce gender segregation in education, training and may help to reduce skills shortages in the labour market.

ET 2020 should support the implementation of the Flagship Initiative ‘Agenda for new skills and jobs’. The Commission has adopted a communication on a ‘Youth Opportunities Initiative’ (14), which underlines the importance of education and training in preventing youth unemployment, and will present later in 2012 a Communication on rethinking skills, proposing action to improve key competences and to promote closer links between education and the labour market. Work under ET 2020 will continue to promote key competences for all citizens, to improve monitoring by developing a new European benchmark on employability, to promote the regular updating of skills and retraining, and to anticipate tomorrow’s labour market demand for skills, in particular through the European Skills Panorama.

3. ET 2020’S CONTRIBUTION TO EUROPE 2020

The above assessment of the the 2009-2011 cycle, including the slow progress towards the education headline target and the ET 2020 benchmarks, underscores the importance of investing effectively in reformed education and training so that it supports sustainable growth and jobs, as well as promotes social inclusion.

The 2012 AGS underscores the need for a demonstrable follow-through by Member States of EU level policy guidance. ET 2020 could be used to support Member States to respond to the challenges identified in the different CSRs: on ESL (AT, DK, ES, MT) and tertiary attainment (BG, CZ, MT, PL, SK); concerning lifelong learning, VET and skills for the labour market (AT, CY, DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, LU, MT, PL, SI, SK, UK); and on pre-school and school education or equity issues (BG, DE, EE).

On the basis of the Commission’s assessment and the consultation of Member States and European stakeholder organisations, the Council and the Commission confirm that the four ET 2020 strategic objectives set in 2009 remain valid. The list of mid-term priority areas agreed in 2009 is replaced by a new one that is geared to mobilise education and training to support growth and jobs (presented in the annex).

In addition, the Commission suggests to review the working arrangements under ET 2020 that were devised before Europe 2020 and the European Semester were agreed. ET 2020 should be better aligned with Europe 2020; it should be the mechanism to mobilise ET 2020 stakeholders, increase their ownership and harness their expertise in support of Europe 2020, drawing also on evidence and data from relevant European agencies and networks (15).

To increase the contribution of ET 2020 to Europe 2020, the governance of ET 2020 and its working tools could be adjusted as follows:

|

1. |

The Council (EYCS) could address the education and training dimension of Europe 2020 during both the European and national semester. The Council could consider the AGS and report to the March European Council, could examine the common issues emerging from the guidance given by the European Council and its implementation through the National Reform Programmes, as well as consider the follow-up to the outcomes of the European Semester. |

|

2. |

Given the integrated nature of Europe 2020, there is scope to step up cooperation between the Education Committee and the Economic Policy Committee, Employment Committee and Social Protection Committee. Cooperation would ensure that ET 2020 feeds-in into the Europe 2020 process, including in terms of the use of monitoring indicators. |

|

3. |

The peer-learning instrument could be used better and linked more closely to Europe 2020. Firstly, to prepare and inform the debate at Council level, an annual peer-review could be held each September/October and organised in close cooperation with the Council Presidency. This multi-lateral approach could focus on key policy issues emerging during the previous European Semester that give rise to a large number of CSRs. Secondly, Member States that wish to do so could invite peers to an in-depth discussion of specific issues in their country. The Commission would use relevant financial instruments to support this activity, including by supporting the participation of internationally renowned experts. |

|

4. |

To strengthen the link between Europe 2020 and ET 2020, the Commission could organise every year an exchange of views between stakeholders in the field of education and training. This new Education and Training Forum could in early October discuss progress in modernising education and training systems drawing on the discussion of education issues in the European Semester. |

|

5. |

The Council will review the list of indicators in the field of education and training (16), to ensure that those used under ET 2020 are consistent with its objectives. Replacing the existing Progress Report (17), the Commission will present every autumn a new Education and Training Monitor, setting out, in a succinct document, progress on the ET 2020 benchmarks and core indicators, including the Europe 2020 Headline Target on education and training. This document would help inform the debate at Council level. |

Finally, all instruments need to be mobilised to achieve the objectives set under Europe 2020 and ET 2020, including the current and future programmes in the field of education and training, the structural funds and Horizon 2020.

(1) OJ C 119, 28.5.2009, p. 2.

(2) Doc. 18577/11 ADD 1 (SEC(2011) 1607 final) and doc. 18577/11 ADD 2 (SEC(2011) 1608 final).

(3) European Expert Network on Economics of Education (EENEE), EENEE Policy Brief 1/2011: The Cost of Low Educational Achievement in the European Union.

(5) Source for 2010 data: Eurostat (LFS).

(6) OJ C 372, 20.12.2011, p. 36.

(7) Source for 2010 data: Eurostat (LFS). (ISCED levels) 5-6. For DE, the target also includes ISCED 4, of AT ISCED 4A.

(9) European Credit System for VET, European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System, cf. http://ec.europa.eu/education/lifelong-learning-policy/doc48_en.htm

(10) OJ L 394, 30.12.2006, p. 10.

(11) COM(2009) 329 final.

(12) OJ L 390, 31.12.2004, p. 6.

(13) http://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/Files/3052_en.pdf

(14) Doc. 5166/12 (COM(2011) 933 final).

(15) In particular, Cedefop, the European Training Foundation and the Eurydice network.

(16) OJ C 311, 21.12.2007, p. 13.

(17) Latest edition: SEC(2011) 526.

ANNEX (1)

Priority areas for European cooperation in education and training in 2012-14

With a view to achieving the four strategic objectives under the ‘ET 2020’ framework, the identification of priority areas for a specific work cycle should improve the efficiency of European cooperation in education and training, as well as reflect the individual needs of Member States, especially as new circumstances and challenges arise.

Member States will select, in accordance with national priorities, those areas of work and cooperation in which they wish to participate in joint follow-up work. If Member States deem necessary, the work on specific priority areas can continue in subsequent work cycles.

1. Making lifelong learning and mobility a reality

Lifelong learning strategies

Work together to complete the development of comprehensive national lifelong learning strategies covering all levels from early childhood education through to adult learning, and focusing on partnerships with stakeholders, competence development of low-skilled adults, measures to extend access to lifelong learning and integrate lifelong learning services (guidance, validation etc.). In particular, implement the Council Resolution of 28 November 2011 on a renewed agenda for adult learning (2).

European reference tools

Work together to link national qualifications frameworks to the EQF, establish comprehensive national arrangements to validate learning outcomes; create links between qualification frameworks, validation arrangements, quality assurance and systems for credit accumulation and transfer (EQAVET, ECVET, ECTS); cooperate in projecting demand for skills and better matching of such demand and the provision of learning opportunities (Skills Panorama, European Classification of Skills/Competences, Qualifications and Occupations-ESCO); improve the visibility, dissemination and use of European reference tools in order to accelerate their implementation.

Learning Mobility

Promote learning mobility for all learners, within Europe and worldwide, at all levels of education and training, focusing on information and guidance, the quality of learning mobility, removing barriers to mobility and promoting teacher mobility. In particular, implement the Council Recommendation ‘Youth on the move — promoting the learning mobility of young people’ (3).

2. Improving the quality and efficiency of education and training

Basic skills (literacy, mathematics, science and technology), languages

Capitalise on evidence on reading literacy, including the report of the High Level Expert Group on Literacy, to raise literacy levels among school students and adults and to reduce the proportion of low-performing 15 year olds in reading. Address the literacy challenges of using a variety of media, including digital, for all. Exploit and develop the results of cooperation to tackle low performance in mathematics and science at school; pursue work to improve language competences, in particular to support learning mobility and employability.

Professional development of teachers, trainers and school leaders

Improve the quality of teaching staff as this is a key determinant of quality outcomes, focus on the quality of teachers, attracting and selecting the best candidates into teaching, quality in continuing professional development, developing teacher competences and reinforcing school leadership.

Modernising higher education and increasing tertiary attainment levels

Work together to increase the number of graduates, including extending alternative pathways and developing tertiary VET; improving the quality and relevance of higher education; raising the quality of higher education through mobility and cross-border cooperation; strengthening the links between higher education, research and innovation to promote excellence and regional development; improving governance and funding.

Attractiveness and relevance of VET

Work together, in line with the Bruges Communiqué on enhanced European Cooperation in Vocational Education and Training for the period 2011-2020, in particular on making initial VET more attractive, promoting excellence and the labour market relevance of VET, implementing quality assurance mechanisms and improving the quality of teachers, trainers and other VET professionals.

Efficient funding and evaluation

Examine funding mechanisms and evaluation systems, with a view to improving quality, including targeted support to disadvantaged citizens and the development of efficient and equitable tools aimed at mobilising private investment in post-secondary education and training.

3. Promoting equity, social cohesion and active citizenship

Early School Leaving

Help Member States implement the 2011 Council Recommendation on policies to reduce early school leaving (4), and their national strategies on early school leaving in general education and VET.

Early childhood education and care (ECEC)

Work together, in line with the 2011 Council conclusions on early childhood education and care (5), to provide widespread equitable access to ECEC while raising the quality of provision; promoting integrated approaches, the professional development of ECEC staff and parental support; developing adequate curricula, and programmes and funding models.

Equity and diversity

Reinforce mutual learning on effective ways to raise educational achievement in an increasingly diverse society, in particular by implementing inclusive educational approaches which allow learners from a wide range of backgrounds and educational needs, including migrants, Roma and students with special needs, to achieve their full potential; enhance learning opportunities for older adults and intergenerational learning.

4. Enhancing creativity and innovation, including entrepreneurship, at all levels of education and training

Partnerships with business, research, civil society

Develop effective and innovative forms of networking, cooperation and partnership between education and training providers and a broad range of stakeholders including, social partners, business organisations, research institutions and civil society organisations. Support networks for schools, universities and other education and training providers to promote new methods of organising learning (including Open Educational Resources), building capacity and developing them as learning organisations.

Transversal key competences, entrepreneurship education, e-literacy, media literacy, innovative learning environments

Work together to promote the acquisition of the key competences identified in the 2006 Recommendation on key competences for lifelong learning, including digital competences and how ICT and entrepreneurship can enhance innovation in education and training, promoting creative learning environments and heightening cultural awareness, expression and media literacy.

(1) NL: reservation on what it regards as the excessively high number of priority areas for a 3-year period. The delegation considers that more time should be devoted to discussing the content of the Annex.