EUROPEAN COMMISSION

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Brussels, 11.4.2016

COM(2016) 199 final

COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS

The 2016 EU Justice Scoreboard

1.INTRODUCTION

Effective justice systems play a crucial role for upholding the rule of law and the Union's fundamental values. They are also a prerequisite for an investment and business friendly environment. This is why improving the effectiveness of national justice systems is one of the priorities of the European Semester – the EU's annual cycle of economic policy coordination. The EU Justice Scoreboard helps Member States to achieve this priority.

The fourth edition of the Scoreboard further develops a comprehensive overview of the functioning of national justice systems: more Member States have participated in the collection of data; new quality indicators have been introduced, for example on standards, training, surveys and legal aid; indicators on independence have been enriched, including with new Eurobarometer surveys; and a deeper insight into certain areas such as electronic communication is provided.

What is the EU Justice Scoreboard?

The EU Justice Scoreboard is an information tool aiming at assisting the EU and Member States to achieve more effective justice by providing objective, reliable and comparable data on the quality, independence and efficiency of justice systems in all Member States.

The Scoreboard contributes to identifying potential shortcomings, improvements and good practices. It shows trends in the functioning of national justice systems over time. It does not present an overall single ranking but an overview of how all the justice systems function, based on various indicators that are of common interest for all Member States.

The Scoreboard does not promote any particular type of justice system and treats all Member States on an equal footing. Whatever the model of the national justice system or the legal tradition in which it is anchored, timeliness, independence, affordability and user-friendly access are some of the essential parameters of an effective justice system.

The Scoreboard focuses on litigious civil and commercial cases as well as administrative cases in order to assist Member States in their efforts to pave the way for a more investment, business and citizen-friendly environment. The Scoreboard is a tool which evolves in dialogue with Member States and the European Parliament, with the objective of identifying the essential parameters of an effective justice system. The European Parliament has called on the Commission to progressively broaden the scope of the Scoreboard and a reflection on how to do so is ongoing.

What is the methodology of the EU Justice Scoreboard?

The Scoreboard uses various sources of information. Large parts of the quantitative data are provided by the Council of Europe Commission for the Evaluation of the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ) with which the Commission has concluded a contract to carry out a specific annual study.

These data range from 2010 to 2014, and have been provided by Member States according to CEPEJ's methodology. The study also provides detailed comments and country-specific information sheets that give more context and should be read together with the figures.

The other sources of data are the group of contact persons on national justice systems, the European Network of Councils for the Judiciary (ENCJ), the Network of the Presidents of the Supreme Judicial Courts of the EU, Association of the Councils of State and Supreme Administrative Jurisdictions of the EU (ACA), the European Competition Network, the Council of Bars and Law Societies of Europe (CCBE), the Communications Committee, the European Observatory on infringements of intellectual property rights, the Consumer Protection Cooperation Network, Eurostat, the European Judicial Training Network (EJTN), the World Bank and the World Economic Forum. The methodology for the 2016 Scoreboard has been enhanced by involving more closely the group of contact persons on national justice systems.

How does the EU Justice Scoreboard feed into the European Semester?

The Scoreboard provides information on the functioning of justice systems and helps assess the impact of justice reforms. If the Scoreboard reveals poor performance, this always requires a deeper analysis of the reasons why. This country-specific assessment is carried out in the context of the European Semester process through bilateral dialogue with the authorities and stakeholders concerned. This assessment takes into account the particularities of the legal system and the context of the concerned Member States. It may eventually lead the Commission to propose to the Council to adopt Country-Specific Recommendations on the improvement of national justice systems.

2.CONTEXT: CONTINUED EFFORTS TO IMPROVE JUSTICE SYSTEMS

This edition of the Scoreboard is being published at a time when a number of Member States are taking measures to improve their justice systems. The figure below shows that in 2015 almost all Member States made, or announced, changes to their justice systems.

Figure 1: Legislative and regulatory activity concerning justice systems in 2015 (adopted measures/announced initiatives per Member State) (source: European Commission

)

Figure 1 presents a factual overview of 'who does what', without any qualitative evaluation. It reveals that many Member States are active in the same areas and could therefore learn from each other. It also shows a dynamic of justice reforms across the EU as, in addition to the measures adopted in 2015, further initiatives have been announced in a number of Member States.

The scope, scale and state of play of the different initiatives vary among Member States. A large number of Member States enacted or announced changes to their procedural law. Their activities continued to focus on information and communication technologies (ICT), but Member States also took initiatives concerning the legal professions, alternative dispute resolution (ADR) methods, legal aid, administration of courts, court fees, statute of judges, redesigning judicial maps, court specialization and Councils for the Judiciary.

These efforts are part of the structural reforms encouraged in the context of the European Semester. The 2016 Annual Growth Survey underlined that "enhancing the quality, independence and efficiency of Member States' justice systems is a prerequisite for an investment and business friendly environment. […] It is necessary to ensure swift proceedings, address the court backlogs, increase safeguards for judicial independence and improve the quality of the judiciary, including through better use of ICT in courts and use of quality standards."

For the same reason, improving national justice systems is also amongst the efforts needed at national level to accompany the Investment Plan for Europe.

The findings of the 2015 Scoreboard, together with a country-specific assessment for each of the Member States concerned, fed into the European Semester. The 2015 European Semester shows that certain Member States are still facing particular challenges.

In particular, the Council, on a proposal from the Commission, addressed Country-Specific Recommendations to certain Member States highlighting ways in which they could make their justice systems more effective.

Moreover, the justice reforms in the other Member States facing challenges are closely monitored through the country reports published during the European Semester

and in those Member States under an Economic Adjustment Programme.

Furthermore, in the context of the Third Pillar of the Investment Plan for Europe, the justice systems in nine Member States have been identified as a challenge to investment.

Between 2014 and 2020, the EU will provide up to EUR 4.2 billion through the European structural and investment funds (ESI Funds) to support justice reforms.

14 Member States

identified justice as an area to be supported by the ESI funds in their programming documents. The Commission emphasises the importance of taking a result-oriented approach when implementing the funds: this approach is also required under the ESI Funds Regulation. The Commission is discussing with Member States how best to assess and evaluate the impact of ESI funds on the justice systems concerned.

The economic impact of fully functioning justice systems justifies these efforts. Effective justice systems play a key role in establishing confidence throughout the business cycle. Where judicial systems guarantee the enforcement of rights, creditors are more likely to lend, firms are dissuaded from opportunistic behaviour, transaction costs are reduced and innovative businesses which often rely on intangible assets (e.g. intellectual property rights - IPR) are more likely to invest. The importance of the effectiveness of national justice systems for SMEs has been highlighted in a 2015 survey of almost 9,000 European SMEs on innovation and IPR. The survey revealed in particular that cost and excessive length of judicial proceedings were among the main reasons for refraining from starting an IPR infringement procedure in court. The positive impact of national justice systems on the economy is underlined in literature and research

, including from the International Monetary Fund,

the European Central Bank,

the OECD,

the World Economic Forum,

and the World Bank.

The relevance of Member States' efforts to improve the effectiveness of their justice systems is also confirmed by the consistently high workload for courts over the years, although the situation varies between Member States, as shown by the figures below.

Figure 2: Number of incoming civil, commercial, administrative and other cases* (first instance/per 100 inhabitants) (source: CEPEJ study

)

* Under the CEPEJ methodology, this category includes all civil and commercial litigious and non-litigious cases, non-litigious land and business registry cases, other registry cases, other non-litigious cases, administrative law cases and other non-criminal cases. IT: A different classification of civil cases was introduced in 2013, so comparing different years might lead to erroneous conclusions. DK: An improved business environment reportedly explains that courts on all levels received fewer cases.

* Under the CEPEJ methodology, this category includes all civil and commercial litigious and non-litigious cases, non-litigious land and business registry cases, other registry cases, other non-litigious cases, administrative law cases and other non-criminal cases. IT: A different classification of civil cases was introduced in 2013, so comparing different years might lead to erroneous conclusions. DK: An improved business environment reportedly explains that courts on all levels received fewer cases.

Figure 3: Number of incoming civil and commercial litigious cases* (first instance/per 100 inhabitants) (source: CEPEJ study)

* Litigious civil and commercial cases concern disputes between parties, e.g. disputes regarding contracts, under the CEPEJ methodology. By contrast, non-litigious civil (and commercial) cases concern uncontested proceedings, e.g. uncontested payment orders. Commercial cases are addressed by special commercial courts in some countries and handled by ordinary (civil) courts in others. ES: The introduction of court fees for natural persons until March 2014 and the exclusion of payment orders reportedly explain variations. EL: Methodological changes introduced in 2014. IT: A different classification of civil cases was introduced in 2013, so comparison between different years might lead to erroneous conclusions.

* Litigious civil and commercial cases concern disputes between parties, e.g. disputes regarding contracts, under the CEPEJ methodology. By contrast, non-litigious civil (and commercial) cases concern uncontested proceedings, e.g. uncontested payment orders. Commercial cases are addressed by special commercial courts in some countries and handled by ordinary (civil) courts in others. ES: The introduction of court fees for natural persons until March 2014 and the exclusion of payment orders reportedly explain variations. EL: Methodological changes introduced in 2014. IT: A different classification of civil cases was introduced in 2013, so comparison between different years might lead to erroneous conclusions.

3.KEY FINDINGS of the 2016 EU Justice Scoreboard

Efficiency, quality and independence are the main parameters of an effective justice system, and the Scoreboard presents indicators on all three.

3.1 Efficiency of justice systems

The indicators related to the efficiency of proceedings are: length of proceedings (disposition time); clearance rate; and number of pending cases.

3.1.1 Length of proceedings

The length of proceedings indicates the estimated time (in days) needed to resolve a case in court, meaning the time taken by the court to reach a decision at first instance. The 'disposition time' indicator is the number of unresolved cases divided by the number of resolved cases at the end of a year multiplied by 365 (days). All figures concern proceedings at first instance and compare, where available, data for 2010, 2012, 2013 and 2014.

* Under the CEPEJ methodology, this category includes all civil and commercial litigious and non-litigious cases, non-litigious land and business registry cases, other registry cases, other non-litigious cases, administrative law cases and other non-criminal cases. Comparisons should be drawn with care as some Member States reported changes in the methodology for data collection or categorisation (CZ, EE, HR, IT, CY, LV, HU, RO, SI, FI). CZ and SK report it is not possible to single out the number of pending cases at first instance, as cases are considered pending until no further proceeding is possible. PT: Data were not available due to technical constraints.

* Under the CEPEJ methodology, this category includes all civil and commercial litigious and non-litigious cases, non-litigious land and business registry cases, other registry cases, other non-litigious cases, administrative law cases and other non-criminal cases. Comparisons should be drawn with care as some Member States reported changes in the methodology for data collection or categorisation (CZ, EE, HR, IT, CY, LV, HU, RO, SI, FI). CZ and SK report it is not possible to single out the number of pending cases at first instance, as cases are considered pending until no further proceeding is possible. PT: Data were not available due to technical constraints.

Figure 5: Time needed to resolve litigious civil and commercial cases*

(first instance/in days) (source: CEPEJ study)

* Litigious civil (and commercial) cases concern disputes between parties, e.g. disputes regarding contracts, under the CEPEJ methodology. By contrast, non-litigious civil (and commercial) cases concern uncontested proceedings, e.g. uncontested payment orders. Commercial cases are addressed by special commercial courts in some countries and by ordinary (civil) courts in others. Comparisons should be drawn with care, as some Member States reported changes in the methodology for data collection or categorisation (CZ, EE, EL, ES, HR, IT, CY, LV, LU, HU, RO, SI, FI) or made caveats on completeness of data that may not cover all federal states or all courts (DE, LU). CZ and SK report it is not possible to single out the number of pending cases at first instance, as cases are considered pending until no further proceeding is possible. Before 2014, NL provided a measured disposition time, not calculated by CEPEJ. PT: Data for 2014 were not available due to technical constraints.

* Litigious civil (and commercial) cases concern disputes between parties, e.g. disputes regarding contracts, under the CEPEJ methodology. By contrast, non-litigious civil (and commercial) cases concern uncontested proceedings, e.g. uncontested payment orders. Commercial cases are addressed by special commercial courts in some countries and by ordinary (civil) courts in others. Comparisons should be drawn with care, as some Member States reported changes in the methodology for data collection or categorisation (CZ, EE, EL, ES, HR, IT, CY, LV, LU, HU, RO, SI, FI) or made caveats on completeness of data that may not cover all federal states or all courts (DE, LU). CZ and SK report it is not possible to single out the number of pending cases at first instance, as cases are considered pending until no further proceeding is possible. Before 2014, NL provided a measured disposition time, not calculated by CEPEJ. PT: Data for 2014 were not available due to technical constraints.

Figure 6: Time needed to resolve administrative cases* (first instance/in days) (source: CEPEJ study)

* Administrative law cases concern disputes between citizens and local, regional or national authorities, under the CEPEJ methodology. Administrative law cases are addressed by special administrative courts in some countries and by ordinary (civil) courts in others. Comparisons should be drawn with care as some Member States reported changes in the methodology for data collection or categorisation (HU, FI), a reorganisation of the administrative court system (HR in 2012) or made caveats on completeness of data that may not cover all federal states or all courts (DE, LU). CZ and SK report it is not possible to single out the number of pending cases at first instance, as cases are considered pending until no further proceeding is possible. CY: The increase in cases related to the bail and their joint resolution reportedly explain variations. MT: An increase in the number of judges reportedly explains variations.

* Administrative law cases concern disputes between citizens and local, regional or national authorities, under the CEPEJ methodology. Administrative law cases are addressed by special administrative courts in some countries and by ordinary (civil) courts in others. Comparisons should be drawn with care as some Member States reported changes in the methodology for data collection or categorisation (HU, FI), a reorganisation of the administrative court system (HR in 2012) or made caveats on completeness of data that may not cover all federal states or all courts (DE, LU). CZ and SK report it is not possible to single out the number of pending cases at first instance, as cases are considered pending until no further proceeding is possible. CY: The increase in cases related to the bail and their joint resolution reportedly explain variations. MT: An increase in the number of judges reportedly explains variations.

3.1.2 Clearance rate

The clearance rate is the ratio of the number of resolved cases over the number of incoming cases. It measures whether a court is keeping up with its incoming caseload. When the clearance rate is about 100% or higher, it means the judicial system is able to resolve at least as many cases as come in. When the clearance rate is below 100%, it means that the courts are resolving fewer cases than the number of incoming cases.

Figure 7: Rate of resolving civil, commercial, administrative and other cases*

(first instance/in % - values higher than 100% indicate that more cases are resolved than come in, while values below 100% indicate that fewer cases are resolved than come in) (source: CEPEJ study)

* Comparisons should be drawn with care as some Member States reported changes in the methodology for data collection or categorisation (CZ, EE, IT, CY, LV, HU, SI, FI). Changes in incoming cases reportedly explain variations in LT and SK. LV: External and internal factors such as new insolvency proceedings reportedly had an impact in variations. PT: Data were not available due to technical constraints.

* Comparisons should be drawn with care as some Member States reported changes in the methodology for data collection or categorisation (CZ, EE, IT, CY, LV, HU, SI, FI). Changes in incoming cases reportedly explain variations in LT and SK. LV: External and internal factors such as new insolvency proceedings reportedly had an impact in variations. PT: Data were not available due to technical constraints.

Figure 8: Rate of resolving litigious civil and commercial cases* (first instance/in %) (source: CEPEJ study)

* Comparisons must be drawn with care, as some Member States reported changes in the methodology for data collection or categorisation (CZ, EE, EL, IT, CY, LV, HU, SI, FI) or made caveats on completeness of data that may not cover all federal states or all courts (DE, LU). NL: Before 2014 a measured disposition time was provided, not calculated by CEPEJ. LU: The introduction of new statistical methods reportedly explains the variations. IE: Historical practices in recording pending civil cases reportedly explain the low results. PT: Data for 2014 were not available due to technical constraints.

* Comparisons must be drawn with care, as some Member States reported changes in the methodology for data collection or categorisation (CZ, EE, EL, IT, CY, LV, HU, SI, FI) or made caveats on completeness of data that may not cover all federal states or all courts (DE, LU). NL: Before 2014 a measured disposition time was provided, not calculated by CEPEJ. LU: The introduction of new statistical methods reportedly explains the variations. IE: Historical practices in recording pending civil cases reportedly explain the low results. PT: Data for 2014 were not available due to technical constraints.

Figure 9: Rate of resolving administrative cases* (first instance/in %) (source: CEPEJ study)

* Comparisons should be drawn with care as some Member States reported changes in the methodology for data collection or categorisation (HU, FI), a reorganisation of the administrative court system (HR in 2012) or made caveats on completeness of data that may not cover all federal states or all courts (DE, LU). LT: Changes in incoming cases reportedly explain variations. MT: An increase in the number of judges reportedly explains variations.

* Comparisons should be drawn with care as some Member States reported changes in the methodology for data collection or categorisation (HU, FI), a reorganisation of the administrative court system (HR in 2012) or made caveats on completeness of data that may not cover all federal states or all courts (DE, LU). LT: Changes in incoming cases reportedly explain variations. MT: An increase in the number of judges reportedly explains variations.

3.1.3 Pending cases

The number of pending cases expresses the number of cases that remains to be dealt with at the end of a period. It also influences the disposition time.

Figure 10: Number of civil, commercial, administrative and other pending cases* (first instance/per 100 inhabitants) (source: CEPEJ study)

* Comparisons should be drawn with care as some Member States reported changes in the methodology for data collection or categorisation (CZ, EE, IT, CY, LV, HU, RO, SI, FI). CZ and SK report it is not possible to single out the number of pending cases at first instance, as cases are considered pending until no further proceeding is possible. ES: Changes in incoming cases reportedly explain variations. PT: Data were not available due to technical constraints.

* Comparisons should be drawn with care as some Member States reported changes in the methodology for data collection or categorisation (CZ, EE, IT, CY, LV, HU, RO, SI, FI). CZ and SK report it is not possible to single out the number of pending cases at first instance, as cases are considered pending until no further proceeding is possible. ES: Changes in incoming cases reportedly explain variations. PT: Data were not available due to technical constraints.

Figure 11: Number of litigious civil and commercial pending cases* (first instance/per 100 inhabitants) (source: CEPEJ study)

* Comparisons should be drawn with care as some Member States reported changes in the methodology for data collection or categorisation (CZ, EE, EL, IT, CY, LV, HU, RO, SI, FI) or made caveats on completeness of data that may not cover all federal states or all courts (DE, LU). Changes in incoming cases reportedly explain variations in DK, EL, and ES. CZ and SK report it is not possible to single out the number of pending cases at first instance, as cases are considered pending until no further proceeding is possible. PT: Data for 2014 were not available due to technical constraints.

* Comparisons should be drawn with care as some Member States reported changes in the methodology for data collection or categorisation (CZ, EE, EL, IT, CY, LV, HU, RO, SI, FI) or made caveats on completeness of data that may not cover all federal states or all courts (DE, LU). Changes in incoming cases reportedly explain variations in DK, EL, and ES. CZ and SK report it is not possible to single out the number of pending cases at first instance, as cases are considered pending until no further proceeding is possible. PT: Data for 2014 were not available due to technical constraints.

Figure 12: Number of administrative pending cases* (first instance/per 100 inhabitants) (source: CEPEJ study)

* Comparisons should be drawn with care, as some Member States reported changes in the methodology for data collection or categorisation (HU, FI), a reorganisation of the administrative court system (HR in 2012) or made caveats on completeness of data that may not cover all federal states or all courts (DE, LU). Changes in incoming cases reportedly explain variations in ES and CY. CZ and SK report it is not possible to single out the number of pending cases at first instance, as cases are considered pending until no further proceeding is possible.

* Comparisons should be drawn with care, as some Member States reported changes in the methodology for data collection or categorisation (HU, FI), a reorganisation of the administrative court system (HR in 2012) or made caveats on completeness of data that may not cover all federal states or all courts (DE, LU). Changes in incoming cases reportedly explain variations in ES and CY. CZ and SK report it is not possible to single out the number of pending cases at first instance, as cases are considered pending until no further proceeding is possible.

3.1.4 Efficiency in specific areas

This section sets out more detailed information on the time needed for courts to resolve disputes in specific areas of law, and complements the general data on the efficiency of justice systems. The areas are selected on the basis of their relevance for the single market, the economy and the business environment in general. Data on the average length of proceedings in these specific areas provide for a more nuanced understanding on how a national justice system functions. The 2016 Scoreboard builds on previous data collection exercises and looks into the areas of insolvency, competition law, consumer law, intellectual property rights, electronic communications law and public procurement.

A closer look at the functioning of courts when applying EU law in specific areas is particularly relevant. EU law forms a common basis in the legal systems of the Member States and litigation based on EU law is therefore particularly suitable for obtaining comparable data. When applying EU law, national courts act as Union courts and ensure that the rights and obligations provided under EU law are enforced effectively. Zooming in on specific areas of EU law sheds light on how effective EU law is enforced. Long delays in judicial proceedings may have negative consequences on the enforcement of rights stemming from the EU law in question, e.g. when appropriate remedies are no longer available or serious financial damages become irrecoverable.

Figure 13 Insolvency: Time needed to resolve insolvency* (in years) (source: World Bank: Doing Business)

* Time for creditors to recover their credit. The period of time is from the company’s default until the payment of some or all of the money owed to the bank. Potential delaying tactics by the parties, such as the filing of dilatory appeals or requests for extension, are taken into consideration. The data are derived from questionnaire responses by local insolvency practitioners and verified through a study of laws and regulations as well as public information on insolvency systems. Data collected in June of each year.

* Time for creditors to recover their credit. The period of time is from the company’s default until the payment of some or all of the money owed to the bank. Potential delaying tactics by the parties, such as the filing of dilatory appeals or requests for extension, are taken into consideration. The data are derived from questionnaire responses by local insolvency practitioners and verified through a study of laws and regulations as well as public information on insolvency systems. Data collected in June of each year.

Figure 14 Competition: Average length of judicial review cases against decisions of national competition authorities applying Articles 101 and 102 TFEU* (first instance/in days) (source: European Commission with the European Competition Network)

One of the main aspects of an attractive business environment is the correct application of competition law. This is essential to ensure that businesses can compete on a level playing field. Judicial review of national competition authorities' decisions at first instance appears to take longer when compared with the disposition time in administrative cases (Figure 6) or in the overall civil, commercial, administrative and other cases (Figure 4). Most likely, these results indicate the complexity and the economic importance of the cases where EU competition law has been applied.

* No cases were identified within this period in BG, EE, CY, MT. IE: The scenario defined for obtaining the data in this figure does not apply (the national competition authority does not have powers to take decisions applying Articles 101 and 102 TFEU). AT: The scenario does not directly apply; data include all cases decided by the Cartel Court involving an infringement of Articles 101 and 102 TFEU. The time needed to resolve judicial review cases was calculated on the basis of the length of cases where a court decision was taken in the year of reference. Member States are presented on the basis of the weighted average length of the judicial proceedings during these three years. The number of relevant cases per Member State varies, but in many instances this number is low (fewer than three per year). This can make the average length dependent on the length of one exceptionally long or short case and results in large variations from one year to another (e.g. BE, DE, PL, UK). Some of the longest cases involved a reference for preliminary ruling to the Court of Justice of the European Union (e.g. CZ).

* No cases were identified within this period in BG, EE, CY, MT. IE: The scenario defined for obtaining the data in this figure does not apply (the national competition authority does not have powers to take decisions applying Articles 101 and 102 TFEU). AT: The scenario does not directly apply; data include all cases decided by the Cartel Court involving an infringement of Articles 101 and 102 TFEU. The time needed to resolve judicial review cases was calculated on the basis of the length of cases where a court decision was taken in the year of reference. Member States are presented on the basis of the weighted average length of the judicial proceedings during these three years. The number of relevant cases per Member State varies, but in many instances this number is low (fewer than three per year). This can make the average length dependent on the length of one exceptionally long or short case and results in large variations from one year to another (e.g. BE, DE, PL, UK). Some of the longest cases involved a reference for preliminary ruling to the Court of Justice of the European Union (e.g. CZ).

Figure 15 Electronic communications: Average length of judicial review cases against decisions of national regulatory authorities applying EU law on electronic communications* (first instance/in days) (source: European Commission with the Communications Committee)

Electronic communications legislation aims to make the related markets more competitive and to generate investment, innovation and growth. The effective enforcement of this legislation is also essential to achieve the goals of lower prices for citizens, better quality services and increased transparency. In general, the average length for resolving judicial review cases in electronic communications law at first instance appears longer than the average length for resolving civil, commercial, administrative and other cases (Figure 4). A comparison with competition (Figure 14) and consumer protection law (Figure 17) cases reveals greater divergences in the average length within the group of cases concerning electronic communications. Most likely, this is due to the broad spectrum of cases covered by this category, ranking from extensive 'market analysis' reviews to consumer-focussed issues.

* No cases were identified in this period in LU and LV, no cases in FI for 2013, no cases in IE and MT for 2014. The number of relevant cases of judicial review varies by Member State. In some instances, the limited number of relevant cases (BE, EE, IE, CY, LT, UK) means that cases with a very long duration can considerably affect the average. AT: In 2013 there were an unusually high number of complex market analysis cases to be decided by the relevant court. DK: A quasi-judicial body is in charge of first instance appeals. In ES, AT, PL different courts are in charge depending on the subject matter of the case.

* No cases were identified in this period in LU and LV, no cases in FI for 2013, no cases in IE and MT for 2014. The number of relevant cases of judicial review varies by Member State. In some instances, the limited number of relevant cases (BE, EE, IE, CY, LT, UK) means that cases with a very long duration can considerably affect the average. AT: In 2013 there were an unusually high number of complex market analysis cases to be decided by the relevant court. DK: A quasi-judicial body is in charge of first instance appeals. In ES, AT, PL different courts are in charge depending on the subject matter of the case.

Figure 16 Community trademark: Average length of Community trademark infringement cases* (first instance/in days) (source: European Commission with the European Observatory on infringements of intellectual property rights)

Intellectual property rights are essential to stimulate investment into innovation. Without effective means of enforcing intellectual property rights, innovation and creativity are discouraged and investment dries up. Therefore, Figure 16 presents data on the time needed for national courts to take a decision in cases concerning an infringement of the most common EU intellectual property title – a Community trademark. EU legislation on Community trademarks gives a significant role to the national courts, which act as Union courts and take decisions affecting the single market territory. Data show differences in the average length of these cases in different Member States, which may have an impact on the Community trademark holders seeking judicial redress in cases of alleged infringements.

* HR: No cases were identified in this period. No cases were identified in LU and IE in 2012, in LT in 2013 and in EE and FI in 2014. The average length of cases has been calculated on the basis of statistical data, where available, or a sample of cases. Member States are organised on the basis of the weighted average length of the judicial proceedings during these three years. DK: Data provided for 2012 and 2013 include all cases related to trademarks. EL: Data for 2014 are a calculated average based on data from different courts. Estimate by courts were used for data in DE, ES, PT, SE. The number of relevant cases by Member State varies. The number of relevant cases was limited (fewer than five) in LT in 2012, in EE and FI in 2012 and 2013, in IE and LU in 2013 and 2014, in HU in 2012 and 2014. This can make the average length dependent on the length of one exceptionally long or short case and results in large variations from one year to another.

Figure 17 Consumer protection: Average length of judicial review cases against decisions of consumer protection authorities applying EU law* (first instance/in days) (source: European Commission with the Consumer Protection Cooperation Network)

Effective enforcement of EU consumer law ensures that consumers benefit from their rights and that companies infringing consumer rules do not gain unfair advantages. Consumer protection authorities and courts play a key role in enforcing EU consumer law. The scenario below covers Member States where consumer protection authorities are empowered to adopt decisions declaring infringements of consumer law. Cases taken up by consumer authorities often concern important consumer issues. Long-lasting judicial review could prolong the resolution of possible consumer law infringements, which may seriously affect consumers and businesses.

* The scenario does not apply to BE, LU, AT, FI, SE, UK. No relevant cases occurred in IE, CY, MT during the period for which data were available. DE: The administrative authorities have competence to adopt decisions in cross-border cases only and no relevant cross-border cases occurred in this period. FR: Cases of appeal are marginal and data were only available for 2013. ES: The data show the average of four autonomous communities each year, and the average may vary for other autonomous communities. The number of cases in DK, EE, FR, HR, LT, NL, SI for the period covered is low, which means that one case with a very long or short duration can considerably affect the average and may lead to bigger variations for each year. Some Member States provided an estimate (IT, PL, RO for 2013). In general, data do not cover financial services and products. The average length is calculated in calendar days, counting from the day when an action or appeal was lodged before the court and to the day on which the court adopted the final decision.

Other specific areas

In 2015, the Commission explored ways to collect data with ACA-Europe - the Association of the Councils of State and Supreme Administrative Jurisdictions of the EU in the area of public procurement. EU law on public procurement

is economically important, as it provides for rapid and effective remedies for actual and potential tenderers who contest the award of public contracts. The data obtained from 17 Member States, show that in 2013-2014 the EU average length of substantive proceedings in public procurement cases at last instance courts was below one year (268 days). Effective judicial review ensures that tenderers can benefit from the full scope of remedies under EU law on remedies in public procurement and that society at large is not affected by delayed performance of public contracts.

|

3.1.5 Summary on the efficiency of justice systems

Timeliness of judicial decisions is essential to ensure the smooth functioning of the justice system. The main parameters used by the Scoreboard for examining the efficiency of justice systems are the length of proceedings (estimated time in days needed to resolve a case), the clearance rate (the ratio of the number of resolved cases over the number of incoming cases) and the number of pending cases (that remains to be dealt with at the end of the year). The 2016 Scoreboard reveals some positive signs.

In comparison with the previous edition of the Scoreboard, data show that:

The length of litigious civil and commercial cases has in general improved (Figure 5). However, for the broad 'all cases' category (Figure 4) and for administrative cases (Figure 6), the length of proceedings has worsened in more countries than it has improved.

In most Member States for which data are available courts have clearance rates above 100% in the 'all cases' category (Figure 7) and for litigious civil and commercial cases (Figure 8). This means that they are able to deal with incoming cases in these areas. However, as regards administrative cases (Figure 9), most Member States have a clearance rate below 100% which shows that they are facing difficulties in coping with incoming cases.

Regarding pending cases, there is overall stability but improvements can be observed in several Member States that faced particular challenges with a high number of pending cases, both in the 'all cases' category (Figure 10) and for administrative cases (Figure 12).

Data over the years show that:

There is some volatility in the results, which may improve or deteriorate in Member States from one year to another. This variance may be explained with contextual factors such as a sudden increase of incoming cases – as variations of more than 10% of incoming cases are not unusual. Varying results may also stem from systemic deficiencies such as lack of flexibility and responsiveness of the justice system, insufficient capacity to adapt to change or inconsistencies in the process of reform.

Where trends over the last three years can be observed, it appears that for litigious civil and commercial cases and the 'all cases' category the length of proceedings has improved in more countries than it has not. However, for administrative cases the situation has deteriorated. In countries where the clearance rate is below 100%, more negative than positive trends can generally be observed for all cases. As regards pending cases, there has been a slight overall reduction in all categories of cases.

Data for specific areas provide a deeper insight into the length of proceedings in certain situations where EU law is involved (e.g. legislation on competition, electronic communications, consumer rights, and intellectual property). The aim of these figures is to better reflect the functioning of justice systems in concrete types of business-related disputes, even if the narrow scenarios used for obtaining the data mean that conclusions must be drawn with some care. The figures show that:

The length of proceedings in the same Member States may vary considerably depending on the area of law concerned. It also appears that certain Member States do less well in these specific areas than in the broader categories of cases presented above. This can be explained by the complexity of the subject matter, specific procedural steps or by the fact that a few complicated cases can affect the average length.

Litigation between private parties is on average shorter than litigation against state authorities. For example, in only a few Member States will a first instance judicial review of national authorities' decisions applying EU law (e.g. competition, consumer or electronic communication authorities) take less than one year on average. This finding highlights the importance for companies and consumers of a smooth functioning of the entire enforcement chain of EU law, from the competent authority to the final instance court. It also confirms the key role that the judiciary plays for the effectiveness of EU law and the economic governance.

|

3.2 Quality of justice systems

Effective justice systems do not only require timely decisions but also quality. A lack thereof may increase business risks for large companies and SMEs and affect consumer choices. Although there is no single agreed way of measuring the quality of justice systems, the Scoreboard focuses on certain factors that are generally accepted as relevant

and which can help to improve the quality of justice. They are grouped in four categories: (1) accessibility of justice for citizens and businesses; (2) adequate material and human resources; (3) putting in place assessment tools; and (4) using quality standards.

3.2.1 Accessibility

Accessibility is required throughout the entire justice chain to facilitate obtaining information – about the justice system, about how to initiate a claim and the related financial aspects, and about the state of play of proceedings up until the end of the process – so that the judgment can be swiftly accessed online.

– Giving information about the justice system –

The foundation for access to justice is the information provided to citizens and businesses about general aspects of the justice system.

Figure 18: Availability of online information about the judicial system for the general public* (source: European Commission)

* In some Member States (SI, RO) information on the composition of costs of proceedings is made available by publishing the legislation that contains the relevant information. BG: Not every website of each court sets out information on the justice system, starting a proceeding, legal aid and composition of costs of proceedings. CZ: Information about starting proceedings is available at the website of the Supreme Court, the Supreme Administrative Court and the Constiutional Court. DE: Each federal state and the federal level decide which information to provide online.

* In some Member States (SI, RO) information on the composition of costs of proceedings is made available by publishing the legislation that contains the relevant information. BG: Not every website of each court sets out information on the justice system, starting a proceeding, legal aid and composition of costs of proceedings. CZ: Information about starting proceedings is available at the website of the Supreme Court, the Supreme Administrative Court and the Constiutional Court. DE: Each federal state and the federal level decide which information to provide online.

– Providing legal aid –

"Legal aid shall be made available to those who lack sufficient resources in so far as such aid is necessary to ensure effective access to justice" (Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU, Article 47(3)). Figure 19 sets out Member States' per capita budget allocation to legal aid. All Member States reported the allocation of a budget.

Figure 19: Annual public budget allocated to legal aid* (EUR per inhabitant) (source: CEPEJ study)

* In certain Member States legal professionals may also cover part of the legal aid; this is not reflected in the figures above.

* In certain Member States legal professionals may also cover part of the legal aid; this is not reflected in the figures above.

Figure 20: Income threshold for legal aid in a specific consumer case* (differences in % between Eurostat poverty threshold and the income threshold) (source: European Commission with the Council of Bars and Law Societies of Europe (CCBE))

Comparing the budgets dedicated to legal aid does not take into account the different macroeconomic conditions that exist throughout the Union. In order to have a better comparison, a specific narrow scenario of a consumer dispute has been explored with CCBE to present the eligibility of individuals for legal aid in the context of each Member State's income and living conditions. The data in Figure 20 relate to this specific scenario. Given the complexity of legal aid regimes in Member States, any comparison should be drawn with care and should not be generalised.

Most Member States grant legal aid on the basis of the applicant's income. Figure 20 below compares in % the income thresholds for granting legal aid with the Eurostat at-risk-of-poverty thresholds (Eurostat threshold). For example, if eligibility for legal aid appears at 20%, it means that an applicant with an income 20% higher than the Eurostat threshold can receive legal aid. On the contrary, if eligibility for legal aid appears at -20%, it means that the income threshold for legal aid is 20% lower than the Eurostat threshold. This provides a comparative overview of the income thresholds used by Member States to grant legal aid in this specific scenario.

Some Member States operate a legal aid system that provides for coverage of 100% of the costs linked to litigation (full legal aid), complemented by a system covering parts of the costs (partial legal aid). Some Member States operate either only a full or only a partial legal aid system.

* Most Member States use disposable income for setting the threshold for legal aid eligibility, except for DK, FR, NL, PT which use gross income. BG: Legal aid covering 100% of the costs is provided to persons who are eligible for receiving social aid monthly allowances; DE: The income threshold amount is based on the Prozesskostenhilfebekanntmachung 2015 and on the average annual housing costs in DE in 2013 (SILC); IE: In addition to the income, the applicant must be able to show that the payment of a financial contribution would cause him/her undue hardship. LV: A range of income between EUR 128.06 and EUR 320 depending on the place of residence of the applicant. The rate is based on the arithmetic mean. FI: The income threshold amount is based on the threshold for available means of an individual without dependants and on the average annual housing costs in FI in 2013 (SILC). UK (SC): The value of the case (EUR 3 000) would be dealt with under small claims proceedings for which there is no full legal aid available.

– Submitting a claim online –

Electronic submission of claims and electronic communication between courts and lawyers is another building block that facilitates access to justice and reduces delays and costs. ICT systems in courts also play an increasingly important role in cross-border cooperation between judicial authorities and thereby facilitate the implementation of EU legislation.

Figure 21: Electronic submission of claims* (0 = available in 0% of courts, 4 = available in 100% of courts) (source: CEPEJ study)

* PL: The possibility to bring a case to the court by electronic means only exists for writ of payment cases. RO: A case may be submitted to courts via email. Subsequently, the submission is printed and added to the case file.

Figure 22: Benchmarking of small claims procedures online (source: 13th eGovernment Benchmarking Report, study being prepared for the European Commission, Directorate-General Communications Networks, Content and Technology)

Easy ways to submit small claims, whether at national or European level, are key to improving citizens’ access to justice and to enabling them to make better use of their consumer rights. The importance of cross-border online small claims procedures is also increasing in response to cross-border e-commerce. One of the European Commission's policy goals is therefore to simplify and speed up small claims procedures by improving the communication between judicial authorities and by making smart use of ICT. The ultimate goal is to reduce administrative burden for all user groups: courts, judicial actors and end-users. For the 13th eGovernment Benchmarking Report commissioned by the European Commission the assessment of the small claims procedure was carried out by a group of researchers (so-called ‘mystery shoppers’). The purpose was to detect whether online public service provisions are organised around users’ needs.

* Member States only received 100 points per category if the service was fully available online through a central portal. They received 50 points if only information on the service as such was available online.

Compared with the figures for the previous year, the chart shows an improvement in the availability in all seven categories. Nineteen Member States showed improvements compared with last year, while none scored less.

– Communication between courts and lawyers –

Figure 23: Electronic communication (0 = available in 0% of courts, 4 = available in 100% of courts) (source: CEPEJ study)

– Communicating with the media –

By receiving and reporting comprehensible and timely information, the media serve as a channel that contributes to the accessibility of justice systems and judicial work.

Figure 24: Relations between courts and the press/media* (source: European Commission)

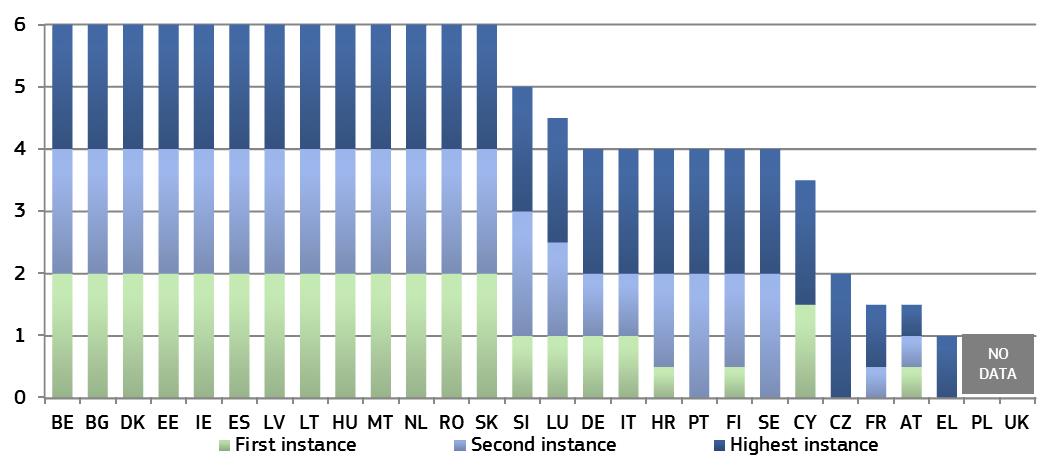

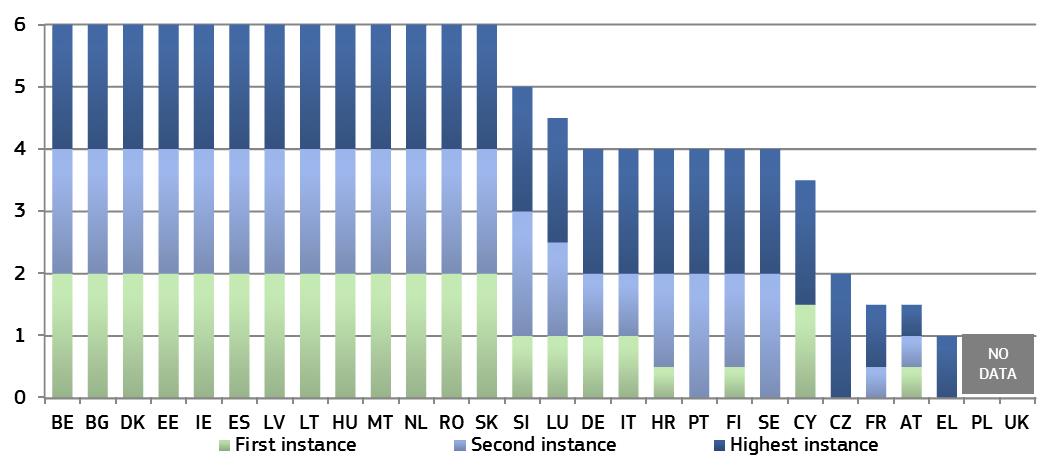

* For each instance (first, second and third), two points can be given if civil/commercial cases and administrative cases are covered. If only one category of cases is covered (e.g. either civil/commercial or administrative), only one point is given. DE: Each federal state has its own guidelines for judges on communicating with the press and media. SE: Judges are actively encouraged to communicate their own judgments to the media. Furthermore, a media group consisting of judges from all three instances has been created.

* For each instance (first, second and third), two points can be given if civil/commercial cases and administrative cases are covered. If only one category of cases is covered (e.g. either civil/commercial or administrative), only one point is given. DE: Each federal state has its own guidelines for judges on communicating with the press and media. SE: Judges are actively encouraged to communicate their own judgments to the media. Furthermore, a media group consisting of judges from all three instances has been created.

– Accessing judgments –

The provision of judgments online contributes to advancing transparency and understanding of the justice system and helps citizens and business to take informed decisions when accessing justice. It could also contribute to increasing consistency of case law.

Figure 25: Access to published judgments online* (civil and commercial and administrative cases, all instances) (source: European Commission)

* For civil/commercial and administrative cases respectively one point was given for each instance where judgments for all courts are available online to the general public (0.5 points when judgments are available only for some courts). Where a Member State has only two instances, points have been given for three instances by mirroring the respective higher instance of the non-existing instance. For example, if a Member State has only the first and the highest instance – with the highest instance receiving two points, the (non-existing) second instance was also given two points. For those Member States that do not distinguish between administrative and civil/commercial cases, the same points have been given for both areas of law. For some Member States not all judgments are made available online. CZ: Some first instance administrative law judgments are made available on the Supreme Administrative Court's website. DE: Each federal state and the federal level decide on the online availability of judgments of their respective courts. IT: Judgments of first and second instance in civil/commercial cases are available online only to the parties concerned. SE: The public is entitled to read all judgments or decisions to the extent that they are not classified. RO: Online availability of judgments to the general public was put in place in December 2015.

* For civil/commercial and administrative cases respectively one point was given for each instance where judgments for all courts are available online to the general public (0.5 points when judgments are available only for some courts). Where a Member State has only two instances, points have been given for three instances by mirroring the respective higher instance of the non-existing instance. For example, if a Member State has only the first and the highest instance – with the highest instance receiving two points, the (non-existing) second instance was also given two points. For those Member States that do not distinguish between administrative and civil/commercial cases, the same points have been given for both areas of law. For some Member States not all judgments are made available online. CZ: Some first instance administrative law judgments are made available on the Supreme Administrative Court's website. DE: Each federal state and the federal level decide on the online availability of judgments of their respective courts. IT: Judgments of first and second instance in civil/commercial cases are available online only to the parties concerned. SE: The public is entitled to read all judgments or decisions to the extent that they are not classified. RO: Online availability of judgments to the general public was put in place in December 2015.

Figure 26: Arrangements for online publication of judgments in all instances* – civil/commercial and administrative cases (source: European Commission)

* For each instance (first, second and third), two points can be given if civil/commercial cases and administrative cases are covered. If only one category of cases is covered (e.g. either civil/commercial or administrative), only one point per instance is given. In some Member States (IE, MT, EE), judges decide on the anonymisation of judgments. IE: Family law, child care and certain other proceedings where statute requires judgments are anonymised. MT: All family cases are anonymised. DE: Online publication of a selection of judgments in most federal states, tagging of judgments with keywords in some federal states, ECLI system in the Federal Constitutional Court, the Federal Administrative Court and the Federal Labour Court. IT: Judgments of first and second instance in civil/commercial cases are accessible online only to the parties concerned. RO: Online availability of judgments to the general public was put in place in December 2015 and decisions are being gradually uploaded dating back to 2007.

* For each instance (first, second and third), two points can be given if civil/commercial cases and administrative cases are covered. If only one category of cases is covered (e.g. either civil/commercial or administrative), only one point per instance is given. In some Member States (IE, MT, EE), judges decide on the anonymisation of judgments. IE: Family law, child care and certain other proceedings where statute requires judgments are anonymised. MT: All family cases are anonymised. DE: Online publication of a selection of judgments in most federal states, tagging of judgments with keywords in some federal states, ECLI system in the Federal Constitutional Court, the Federal Administrative Court and the Federal Labour Court. IT: Judgments of first and second instance in civil/commercial cases are accessible online only to the parties concerned. RO: Online availability of judgments to the general public was put in place in December 2015 and decisions are being gradually uploaded dating back to 2007.

– Accessing alternative dispute resolution methods –

Access to justice is not limited to courts but applies to other avenues outside courts as well. All Member States that provided data have put in place alternative dispute resolution methods. Promoting and incentivising their voluntary use in order to inform and raise awareness contributes to improving access to justice. Figure 27 covers any method for resolving disputes other than litigation in courts. Mediation, conciliation and arbitration are the most common forms of alternative dispute resolution methods.

Figure 27: Promotion of and incentives for using alternative dispute resolution methods* (source: European Commission)

* Aggregated indicators based on the following indicators: 1) website providing information on ADR; 2) Publicity campaigns in media; 3) Brochures to the general public; 4) Court provides specific information sessions on ADR upon request; 5) ADR/mediation co-ordinator at courts; 6) Publication of evaluations on the use of ADR; 7) Publication of statistics on the use of ADR; 8) Legal aid covers costs (in part or in full) incurred with ADR; 9) Full or partial refund of court fees; including stamp duties; if ADR is successful; 10) No lawyer for ADR procedure required; 11) Judge can act as mediator; 12) Others. For each of these 12 indicators, one point was given. For each area of law, a maximum of 12 points could be given. In some Member States (ES, FR, LT), conciliation procedures prior to judicial proceedings are compulsory in labour disputes. In addition in ES, judicial mediation is compulsory once judicial proceedings have started. IE: Promotion and incentives relate only to family proceedings. IT: Judges can act as a conciliator in a proceeding and, if so, the conciliation can be enforced. LV: No court fees are charged in labour disputes.

3.2.2 Resources

Adequate resources are necessary for the good functioning of the justice system and to have the right conditions at courts and well-qualified staff in place. Without a sufficient number of staff with the required qualifications and skills and access to continuous training, the quality of proceedings and decisions are at stake.

– Financial resources –

The figures below show the budget actually spent on courts, first by inhabitant (Figure 28) and second as a share of gross domestic product (Figure 29).

Figure 28: General government total expenditure on law courts*

(in EUR per inhabitant) (source: Eurostat)

* Data for ES, LT, LU, NL and SK are provisional..

* Data for ES, LT, LU, NL and SK are provisional..

Figure 29: General government expenditure on law courts* (as a percentage of gross domestic product) (source: Eurostat)

* Data for ES, LT, LU, NL and SK are provisional..

* Data for ES, LT, LU, NL and SK are provisional..

– Human resources –

Human resources are an important asset for the justice system. Gender balance of judges adds complementary knowledge, skills and experience and reflects the reality of society.

Figure 30: Number of judges* (per 100 000 inhabitants) (source: CEPEJ study)

* This category consists of judges working full-time, under the CEPEJ methodology. It does not include the Rechtspfleger/court clerks that exist in some Member States. EL: The total number of professional judges includes different categories over the years shown above, which partly explains their variation.

* This category consists of judges working full-time, under the CEPEJ methodology. It does not include the Rechtspfleger/court clerks that exist in some Member States. EL: The total number of professional judges includes different categories over the years shown above, which partly explains their variation.

Figure 31: Proportion of female professional judges at first and second instance and Supreme Courts (source: European Commission (Supreme Courts) and CEPEJ study (first and second instance))

Seven Member States report a gender balanced

rate of judges for both instances and 14 report a rate of female judges above the gender balance for at least one of the two instances. At Supreme Court level, however, 19 Member States report rates of female professional judges below – in some cases far below – 40%.

Figure 32: Variation in proportion of female professional judges at both first and second instance from 2010 to 2014 as well as at Supreme Courts from 2010 to 2015* (difference in percentage points) (source: European Commission (Supreme Courts) and CEPEJ study (first and second instance))

* LU: the proportion of female professional judges in the Supreme Court declined from 100% in 2010 to 50% in 2015.

* LU: the proportion of female professional judges in the Supreme Court declined from 100% in 2010 to 50% in 2015.

Figure 33: Number of lawyers* (per 100 000 inhabitants) (source: CEPEJ study)

* A lawyer is a person qualified and authorised according to national law to plead and act on behalf of his or her clients, to engage in the practice of law, to appear before the courts or advise and represent his or her clients in legal matters (Recommendation Rec (2000)21 of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on the freedom of exercise of the profession of lawyer).

– Training –

The promotion of training, as part of human resources policies, is a necessary tool to sustain and improve the quality of justice systems. Judicial training, including in judicial skills, is also important in contributing to the quality of judicial decisions and the justice service delivered to citizens. The data set out below cover judicial training in a broad range of areas, including on communication with parties and the press.

Figure 34: Compulsory training for judges* (source: CEPEJ study)

* The following Member States do not offer training in certain categories: MT (initial training); DK (specialised functions); EL, IE, MT, ES (management functions); BG, EE, MT (use of computer facilities). In all other cases, training may be provided but it is optional.

Figure 35: Judges participating in continuous training activities in EU law or in the law of another Member State* (as a percentage of total number of judges) (source: European Commission, European judicial training 2015)

* In a few cases reported by Member States the ratio of participants to existing members of a legal profession exceeds 100%, meaning that participants took part in more than one training activity on EU law.

* In a few cases reported by Member States the ratio of participants to existing members of a legal profession exceeds 100%, meaning that participants took part in more than one training activity on EU law.

Figure 36: Percentage of continuous judicial training activities on various types of judicial skills* (source: European Commission)

* The table shows the distribution of continuous judicial training activities (i.e. those taking place after the initial training period to become a judge) in each of the four identified areas as a percentage of the total. Legal training activities are not taken into account. Judicial training authorities in DK, LU, UK(NI) did not provide specific training activities on the selected skills.

* The table shows the distribution of continuous judicial training activities (i.e. those taking place after the initial training period to become a judge) in each of the four identified areas as a percentage of the total. Legal training activities are not taken into account. Judicial training authorities in DK, LU, UK(NI) did not provide specific training activities on the selected skills.

Figure 37: Availability of training for judges on communication with parties and the press (source: European Commission)

3.2.3 Assessment tools

Improving the quality of justice systems requires tools to assess their functioning. Monitoring and evaluation of court activities help to improve court performance by detecting deficiencies and needs, and by making the justice system more responsive to current and future challenges. Adequate ICT tools can provide real-time case management, standardised court statistics, management of backlogs and automated early-warning systems. Surveys are also indispensable to assess how justice systems operate from the perspective of legal professionals and court users. Beyond the mere fact of surveys being conducted, the 2016 Justice Scoreboard has looked deeper into the topics and follow-up of surveys conducted among court users or legal professionals.

Figure 38: Availability of monitoring and evaluation of court activities* (source: CEPEJ study)

* The monitoring system aims to assess the day-to-day activity of courts thanks, in particular to data collections and statistical analysis. The evaluation system refers to the performance of court systems, using indicators and targets. In 2014, all Member States reported having a system that allows them to monitor the number of incoming cases and the number of decisions handed down, making these categories irrelevant. Similarly, in-depth work drawn in 2015 superseded the mere reference to quality standards as an evaluation category. This has made it possible to merge the remaining categories in a single figure for monitoring and evaluation. Data on 'other elements' include e.g. appealed cases (EE, ES, LV), hearings (SE), or the number of cases solved within certain timeframes (DK).

Figure 39: ICT used for case management and for court activity statistics*

(weighted indicator: min=0, max=4) (source: CEPEJ study)

* IE: Electronic case filing is mandatory for personal insolvency cases other than bankruptcy and optional for any small claim.

* IE: Electronic case filing is mandatory for personal insolvency cases other than bankruptcy and optional for any small claim.

Figure 40: Topics of surveys conducted among court users or legal professionals* (source: European Commission)

* Some Member States that did not carry out surveys in 2014 did so in 2015 (IT) or plan it in 2016 (IE).

* Some Member States that did not carry out surveys in 2014 did so in 2015 (IT) or plan it in 2016 (IE).

Figure 41: Follow-up of surveys conducted among court users or legal professionals (source: European Commission)

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Brussels, 11.4.2016

COM(2016) 199 final

COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS

The 2016 EU Justice Scoreboard

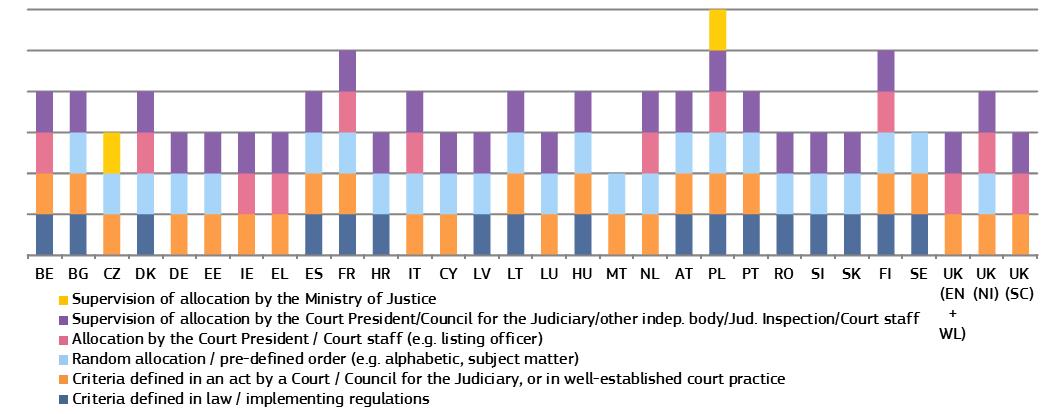

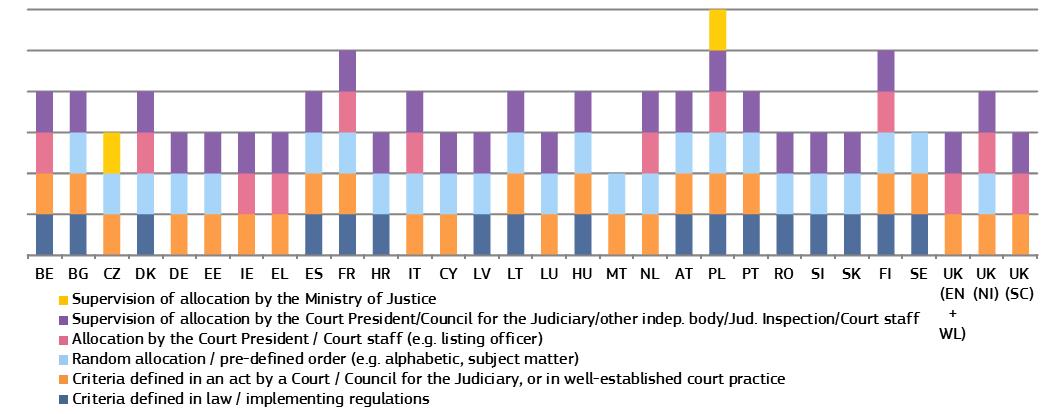

3.2.4 Quality standards

Standards can drive up the quality of justice systems. In 2015, the Commission started to work with the group of contact persons specifically on the standards relating to the functioning of justice systems. Quality standards involve a broad range of topics on how justice systems are set up and work. Several actors can play a role in establishing such standards. Figure 42 presents a general mapping of existing standards. It shows that standards covering many aspects of their justice systems are defined in a large number of Member States. The information collected also reveals that standards are predominantly defined by law. However, issues directly related to the operational functioning of courts are mainly set at court level, including through well-established court practices. This concerns in particular the management of backlogs, monitoring of cases, caseload of courts, services provided to court users, court facilities and information to parties.

Figure 42: Defined standards on aspects related to the justice system* (source: European Commission)

* Note that blank replies in standards related to administrative cases may be due to the absence of a specific 'administrative case' category (e.g. IE). PL and UK did not provide information on standards. In the highlighted areas, standards are predominantly set by courts, including through well-established court practices. For all other areas, standards are predominantly defined by the law.

Figure 43 below examines six specific aspects: processing time (time limits and timeframes), management of backlogs, active monitoring of cases, information to parties, judgments and allocation of human resources. It shows that, although in most Member States the areas covered by standards appear to be the same, their content may differ significantly.

For example, in a limited number of Member States standards on backlog management provide for a maximum age of pending cases or for measures to correct the backlog. Standards on information to parties range from informing parties about their case at court premises to parties having online access to the information or being provided with it automatically. Case monitoring and early-warning systems are seldom automated, although in most Member States it is technically possible to have real-time information by means of case management systems. Standardised electronic templates available to judges in a number of Member States can range from simple formal models to more developed material aimed at facilitating the drafting of decisions.

Finally, it appears that some standards have been defined and implemented nationwide, while others apply only in certain courts or territories or to certain types of case or justice area.

Figure 43: Specific standards in selected aspects related to the justice system* (source: European Commission)

* CY, IE did not report any standards in the selected areas. PL, UK did not provide information on standards. DE: De-centralized structures mean that standards may differ from federal state to federal state and from court to court. The lighter column corresponds to the total number of Member States that defined other standards in the selected areas. Standards on case processing time include civil, commercial and administrative cases.

|

3.2.5 Summary on the quality of justice systems

Easy access, adequate resources, effective assessment tools and appropriate standards are key factors that contribute to the quality of justice systems. The 2016 Scoreboard confirms that the situation varies significantly across the EU, but also that many Member States are making particular efforts in these areas.

Accessibility

The Scoreboard examines the accessibility of justice systems throughout the entire justice chain and shows the following:

Online information about the justice system is available in all Member States. However, information on how to start a judicial proceeding and on the composition of costs of proceedings is still not available in some Member States (Figure 18). Certain Member States have developed advanced user-friendly solutions in that respect, e.g. by providing an interactive online tool that allows legal aid applicants to calculate the likelihood of being eligible for legal aid.

Legal aid is essential for guaranteeing equal access to justice. Compared with 2010 it appears that more Member States increased the budget for legal aid than decreased it (Figure 19). When comparing the financial eligibility for legal aid in the specific scenario of a consumer dispute, in most Member States the income threshold for obtaining legal aid covering at least part of the costs is above the respective Eurostat poverty threshold (Figure 20). Some Member States have a system in place that requires an annual review and possibly adaptation of the legal aid threshold.

Electronic submission of claims is not in place in all Member States (Figure 21). However, the quality of small claim proceedings online, e.g. obtaining information on case handling or the possibility to appeal court decisions, has progressed since 2013 (Figure 22). This is a sign that Member States have made efforts to meet the needs of citizens and businesses using the justice system.

Electronic communication between courts and parties is still not possible in some Member States (Figure 23). The lack of ICT tools make judicial proceedings more difficult and costly, both for the courts and the parties; e.g. in one Member State, a reform enabling courts to deliver documents electronically to parties and lawyers saved more than EUR 4.2 million in 2015 (more than 2% of the courts' budget).

Online availability of courts' judgments for civil, commercial and administrative cases could be improved (Figure 25). Following the publication of figures on this issue in the 2015 Scoreboard, certain Member States have started implementing measures to increase online availability of judgments including at first instance.

The voluntary use of alternative dispute resolution methods (e.g. mediation, conciliation) is promoted and incentivised in all Member States. This is more often for civil and commercial disputes than for labour and consumer disputes (Figure 27). This positive development shows that there are means to encourage the voluntary use of alternative dispute resolution methods without affecting the fundamental right to have a remedy before a tribunal. The use of ADR for solving disputes between consumers and traders is expected to increase in the future with the implementation in 2016 of the Consumer ADR Directive and the Online Dispute Resolution (ODR) Regulation.

Resources

High-quality justice requires an adequate level of financial and human resources, appropriate training and gender balance among judges. The Scoreboard shows the following:

In terms of financial resources, data show that the expenditure on judicial system in most Member States remains rather stable (Figure 28). When determining financial resources for the judiciary only a few Member States take into account current data on the number of incoming or resolved cases to evaluate the costs incurred (Figure 51).

The level of gender balance among judges in first and/or second instance courts is in general good. In most Member States, each gender accounts for between 40-60%. In Supreme Courts, even if most Member States are moving towards gender balance, progress remains slow in some (Figure 32).

As regards the training of judges, while Member States recognise the importance of continuous and compulsory initial training (Figure 34), efforts are needed to improve the scope of the training offered, in particular on judicial skills. Continuous training on judicial skills (judgecraft), IT skills, court management and judicial ethics does not exist in all Member States and, where it exists, training activities often fail to cover all such skills (Figure 36). Furthermore, certain Member States do not provide training on communication with parties and with the press (Figure 37), a crucial aspect for end-users and for fostering confidence in the justice system.

Assessment tools

Monitoring and evaluation tools for assessing the functioning of justice systems are available in most Member States (Figure 38). However, monitoring processes related to backlogs or early-warning systems are seldom automated (Figure 43). Moreover, not all data collection systems provide sufficient information on the functioning of the system, in particular for second and higher instances and for specific categories of cases, such as insolvency. In certain Member States, new generations of ICT tools are sufficiently flexible to meet new needs or to collect data on the impact of particular reforms; e.g. when reforming its ADR legislation, one Member State established a specific regular quarterly collection of data to evaluate its impact.

ICT case management systems still need to be improved in many Member States to ensure that they can serve various purposes and that they are implemented consistently across the whole justice system (Figure 39). In certain Member States, it is still not possible to ensure nationwide data collection across all justice areas. In some Member States, ICT tools do not provide for the real-time monitoring of case progress, or for the management of backlogs, including the identification of particularly old cases. By contrast, certain Member States have early-warning systems to detect malfunctions or comply with case processing standards, which facilitates the finding of timely solutions.