COMMISSION NOTICE –

Guidance on the interpretation and application of Directive 2005/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council concerning unfair business-to-consumer commercial practices in the internal market

(Text with EEA relevance)

(2021/C 526/01)

CONTENTS

| INTRODUCTION | 5 |

|

1. |

SCOPE OF THE UCPD | 5 |

|

1.1. |

Material scope of application | 5 |

|

1.1.1. |

National legislation concerning commercial practices but protecting interests other than consumers’ economic interests | 6 |

|

1.1.2. |

Commercial practices which relate to a business-to-business transaction or which harm only competitors’ economic interests | 7 |

|

1.2. |

Interplay between the Directive and other EU law | 8 |

|

1.2.1. |

Relationship with other EU legislation | 8 |

|

1.2.2. |

Information established by other EU law as ‘material’ information | 10 |

|

1.2.3. |

Interplay with the Consumer Rights Directive | 12 |

|

1.2.4. |

Interplay with the Unfair Contract Terms Directive | 13 |

|

1.2.5. |

Interplay with the Price Indication Directive | 15 |

|

1.2.6. |

Interplay with the Misleading and Comparative Advertising Directive | 16 |

|

1.2.7. |

Interplay with the Services Directive | 17 |

|

1.2.8. |

Interplay with the e-Commerce Directive | 17 |

|

1.2.9. |

Interplay with the Audiovisual Media Services Directive | 17 |

|

1.2.10. |

Interplay with the General Data Protection Regulation and the e-Privacy Directive | 18 |

|

1.2.11. |

Interplay with Articles 101-102 TFEU (EU competition rules) | 19 |

|

1.2.12. |

Interplay with the EU Charter of fundamental rights | 20 |

|

1.2.13. |

Interplay with Articles 34-36 TFEU | 20 |

|

1.2.14. |

Interplay with the Platform-to-Business Regulation | 21 |

|

1.3. |

The relationship between the UCPD and self-regulation | 21 |

|

1.4. |

Enforcement and redress | 22 |

|

1.4.1. |

Public and private enforcement | 22 |

|

1.4.2. |

Penalties | 22 |

|

1.4.3. |

Consumer redress | 25 |

|

1.4.4. |

Application of the UCPD to traders established in third countries | 25 |

|

2. |

MAIN CONCEPTS OF THE UCPD | 25 |

|

2.1. |

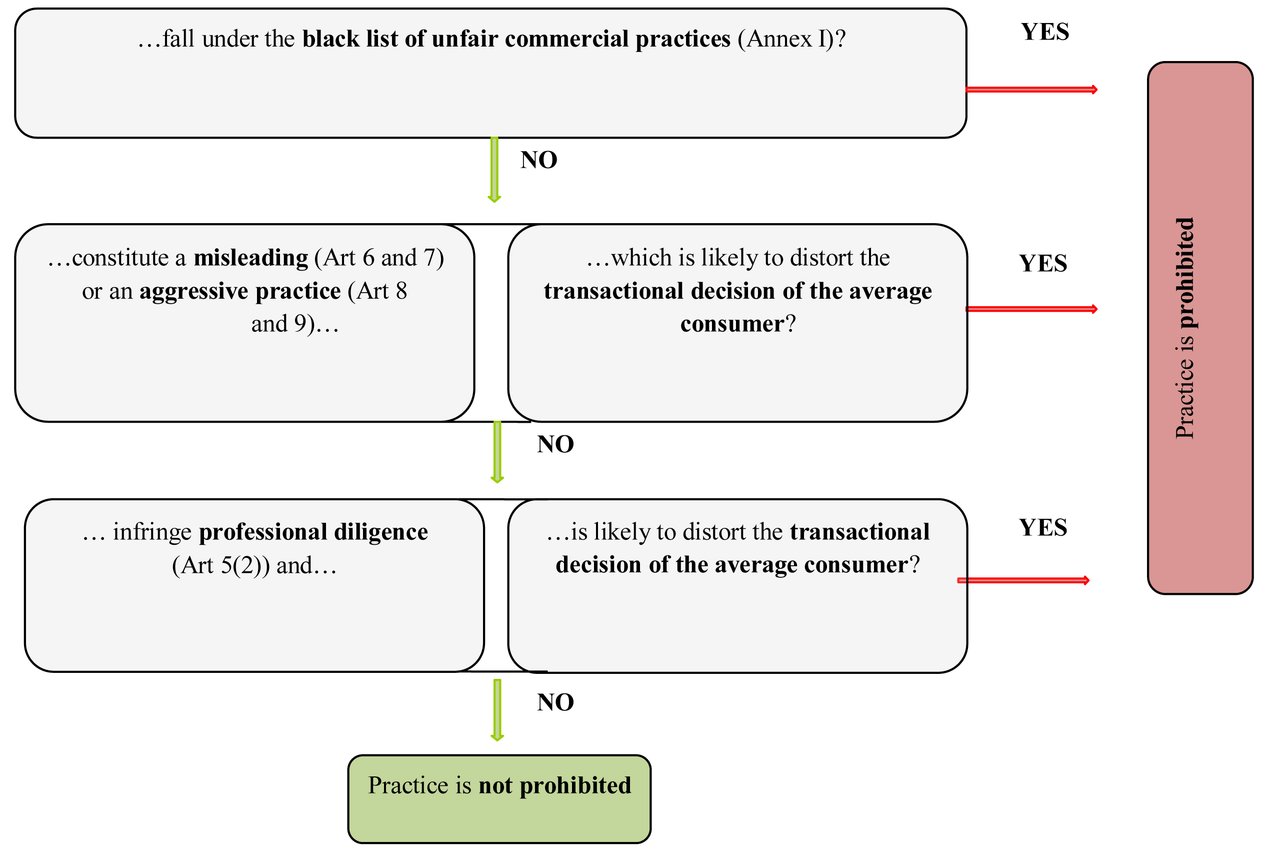

The functioning of the UCPD – Directive flowchart | 25 |

|

2.2. |

The concept of trader | 26 |

|

2.3. |

The concept of commercial practice | 28 |

|

2.3.1. |

After-sales practices, including debt collection activities | 29 |

|

2.3.2. |

Traders buying products from consumers | 30 |

|

2.4. |

Transactional decision test | 30 |

|

2.5. |

Average consumer | 33 |

|

2.6. |

Vulnerable consumers | 35 |

|

2.7. |

Article 5 - professional diligence | 36 |

|

2.8. |

Article 6 - misleading actions | 38 |

|

2.8.1. |

General misleading information | 39 |

|

2.8.2. |

Price advantages | 41 |

|

2.8.3. |

Confusing marketing | 42 |

|

2.8.4. |

Non-compliance with codes of conduct | 43 |

|

2.8.5. |

‘Dual quality’ marketing | 44 |

|

2.9. |

Article 7 - misleading omissions | 49 |

|

2.9.1. |

Material information | 50 |

|

2.9.2. |

Hidden marketing/failure to identify commercial intent | 50 |

|

2.9.3. |

Material information provided in an unclear manner | 51 |

|

2.9.4. |

The factual context and limits of the communication medium used | 52 |

|

2.9.5. |

Material information in invitations to purchase – Article 7(4) | 53 |

|

2.9.6. |

Free trials and subscription traps | 58 |

|

2.10. |

Articles 8 and 9 - aggressive commercial practices | 59 |

|

3. |

BLACK LIST OF COMMERCIAL PRACTICES (ANNEX I) | 60 |

|

3.1. |

Products which cannot legally be sold – No 9 | 61 |

|

3.2. |

Pyramid schemes – No 14 | 62 |

|

3.3. |

Products which cure illnesses, dysfunctions and malformations – No 17 | 63 |

|

3.4. |

Use of the claim ‘free’ – No 20 | 66 |

|

3.5. |

Reselling events tickets acquired by automated means – No 23a | 69 |

|

3.6. |

Persistent marketing by a remote tool – No 26 | 69 |

|

3.7. |

Direct exhortations to children – No 28 | 70 |

|

3.8. |

Prizes – No 31 | 71 |

|

4. |

APPLICATION OF THE UCPD TO SPECIFIC FIELDS | 72 |

|

4.1. |

Sustainability | 72 |

|

4.1.1. |

Environmental claims | 72 |

|

4.1.1.1. |

Interplay with other EU legislation on environmental claims | 73 |

|

4.1.1.2. |

Main principles | 75 |

|

4.1.1.3. |

Application of Article 6 of the UCPD to environmental claims | 76 |

|

4.1.1.4. |

Application of Article 7 of the UCPD to environmental claims | 79 |

|

4.1.1.5. |

Application of Article 12 of the UCPD to environmental claims | 81 |

|

4.1.1.6. |

Application of Annex I to environmental claims | 82 |

|

4.1.1.7. |

Comparative environmental claims | 83 |

|

4.1.2. |

Planned obsolescence | 84 |

|

4.2. |

Digital sector | 86 |

|

4.2.1. |

Online platforms and their commercial practices | 87 |

|

4.2.2. |

Intermediation of consumer contracts with third parties | 89 |

|

4.2.3. |

Transparency of search results | 90 |

|

4.2.4. |

User reviews | 93 |

|

4.2.5. |

Social media | 96 |

|

4.2.6. |

Influencer marketing | 97 |

|

4.2.7. |

Data-driven practices and dark patterns | 99 |

|

4.2.8. |

Pricing practices | 102 |

|

4.2.9. |

Gaming | 103 |

|

4.2.10. |

Use of geo-localisation techniques | 105 |

|

4.2.11. |

Consumer lock-in | 106 |

|

4.3. |

Travel and transport sector | 107 |

|

4.3.1. |

Cross-cutting issues | 107 |

|

4.3.2. |

Package travel | 109 |

|

4.3.3. |

Timeshare contracts | 109 |

|

4.3.4. |

Issues relevant in particular to air transport | 110 |

|

4.3.5. |

Issues relevant in particular to car rental | 114 |

|

4.3.6. |

Issues relevant in particular to travel booking websites | 115 |

|

4.4. |

Financial services and immovable property | 116 |

|

4.4.1. |

Cross-cutting issues | 116 |

|

4.4.2. |

Issues specific to immovable property | 117 |

|

4.4.3. |

Issues specific to financial services | 118 |

| ANNEX | 121 |

INTRODUCTION

Directive 2005/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council (1) on unfair business-to-consumer commercial practices in the internal market (‘the UCPD’) constitutes the overarching piece of EU legislation regulating unfair commercial practices in business-to-consumer transactions. It applies to all commercial practices that occur before, during and after a business-to-consumer transaction has taken place.

The purpose of this Guidance Notice (hereinafter referred to as ‘Notice’) is to facilitate the proper application of the Directive. It builds upon and replaces the 2016 version of the Guidance (2). The Notice also aims at increasing awareness of the Directive amongst all interested parties, such as consumers, businesses, the authorities of the Member States, including national courts and legal practitioners, across the EU. It covers the amendments introduced by Directive (EU) 2019/2161 of the European Parliament and of the Council (3) as regards the better enforcement and modernisation of Union consumer protection rules that enter into application from 28 May 2022. Accordingly, a part of this guidance reflects and discusses the rules that have not yet entered into application as of the date of issuance of this Notice. The relevant sections and points are clearly indicated. Where quotations from the text of the Directive or from Court rulings contain visual highlighting, such emphasis has been added by the Commission.

This Notice is addressed to the EU Member States and to Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway as signatories of the Agreement on the European Economic Area (EEA). References to the EU, the Union or the Single Market should therefore be understood as referring to the EEA, or to the EEA market.

This Notice is intended purely as a guidance document – only the text of the Union legislation itself has legal force. Any authoritative reading of the law has to be derived from the text of the Directive and directly from the decisions of the Court. This Notice takes into account rulings of the Court published until October 2021 and cannot prejudge further developments of the Court’s case law.

The views expressed in this document cannot prejudge the position that the European Commission might take before the Court. The information herein is of a general nature only and does not specifically address any particular individuals or entities. Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the European Commission is responsible for any use that may be made of the following information.

As this Notice reflects the state of the art at the time of drafting, the guidance offered may be modified at a later date.

1. SCOPE OF THE UCPD

|

Article 3(1) This Directive shall apply to unfair business-to-consumer commercial practices as laid down in Article 5, before, during and after a commercial transaction in relation to a product. |

The Directive is horizontal in nature and protects the economic interests of consumers. Its principle-based provisions address a wide range of practices and are sufficiently broad to catch also fast-evolving products and sales methods.

1.1. Material scope of application

The UCPD is based on the principle of full harmonisation. In order to remove internal market barriers and increase legal certainty for both consumers and businesses, it establishes a uniform regulatory framework harmonising national rules. Consequently, the UCPD establishes that Member States may not adopt stricter rules than those provided for in the Directive, even in order to achieve a higher level of consumer protection unless so permitted by the Directive itself (4).

The Court confirmed this principle in several rulings. For example, in the Total Belgium case the Court found that the Directive precludes a national general prohibition on combined offers (5). In the Europamur Alimentación case the Court ruled that the UCPD precludes a national general prohibition on offering for sale or selling goods at a loss (6). In the same case, the Court also clarified that restrictive national measures may include the reversal of the burden of proof (7).

In that regard, Article 3(9) places a limitation on the full harmonisation character of the UCPD by stating that ‘in relation to ‘financial services’ […] and immovable property, Member States may impose requirements which are more restrictive or prescriptive than this Directive in the field which it approximates’. Consequently, in these sectors, Member States can impose rules which go beyond the provisions of the UCPD, as long as they comply with other EU law. Section 4.4 specifically deals with how the UCPD applies to financial services and immovable property.

Furthermore, according to Article 3(5), as amended by Directive (EU) 2019/2161, the Directive does not prevent Member States from adopting additional provisions to protect the legitimate interests of consumers with regard to aggressive or misleading marketing or selling practices in the context of unsolicited visits by a trader to a consumer’s home or excursions organised by a trader with the aim or effect of promoting or selling products to consumers. However, such provisions shall be proportionate, non-discriminatory and justified on grounds of consumer protection. Recital 55 to Directive (EU) 2019/2161 explains that such provisions should not prohibit those sales channels as such and gives some non-exhaustive examples of the possible national measures.

Article 3(6) requires Member States to notify the Commission of the national provisions adopted and any subsequent changes, so that the Commission can make this information easily accessible to consumers and traders on a dedicated website (8).

Recital 14 UCPD clarifies that the full harmonisation does not preclude Member States from specifying in national law the main characteristics of particular products, the omission of which would be material when an invitation to purchase is made. It also clarifies that the UCPD is without prejudice to provisions of EU law which expressly afford Member States the choice between several regulatory options for the protection of consumers in the field of commercial practices.

As regards consumer information, Recital 15 UCPD explains that Member States can, when allowed by the minimum clauses in EU law, maintain or introduce more stringent information requirements in conformity with EU law so as to ensure a higher level of protection of consumers' individual contractual rights. See also section 1.2.3, which explains the interplay with the pre-contractual information requirements in the Consumer Rights Directive.

1.1.1. National legislation concerning commercial practices but protecting interests other than consumers’ economic interests

|

Article 1 The purpose of this Directive is to contribute to the proper functioning of the internal market and achieve a high level of consumer protection by approximating the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States on unfair commercial practices harming consumers’ economic interests. |

The UCPD does not cover national rules intended to protect interests which are not of an economic nature. Therefore, the UCPD does not affect the possibility of Member States to set rules regulating commercial practices for reasons of health, safety or environmental protection.

Also existing national rules on marketing and advertising, based on ‘taste and decency’ are not covered by the UCPD. According to Recital 7, ‘This Directive […] does not address legal requirements related to taste and decency which vary widely among the Member States. […] Member States should accordingly be able to continue to ban commercial practices in their territory, in conformity with Community law, for reasons of taste and decency even where such practices do not limit consumers’ freedom of choice. […].’

Therefore, in the context of commercial practices, the UCPD does not cover national rules on protecting human dignity, preventing sexual, racial and religious discrimination or on the depiction of nudity, violence and antisocial behaviour.

For example, the Court clarified that the UCPD did not apply to a national provision preventing a trader from opening its shop 7 days a week by requiring traders to choose a weekly closing day, as this specific provision did not pursue objectives related to consumer protection (9).

The Court has further clarified that the UCPD does not preclude a national provision, which protects public health and the dignity of the profession of dentist, first, by imposing a general and absolute prohibition of any advertising relating to the provision of oral and dental care services and, secondly, by establishing certain requirements of discretion with regard to signs of dental practices (10).

Conversely, national rules that aim to protect the economic interest of consumers, even if it is in conjunction with other interests, do fall within its scope.

Concerning national rules banning sales with bonuses, the Court has clarified that the UCPD precludes a general national ban on sales with bonuses that is designed to achieve consumer protection and other objectives (such as the pluralism of the press) (11).

Concerning national rules allowing clearance sales to be announced only if authorised by the competent district administrative authority, the Court noted that the referring court had implicitly accepted that such a provision, which was at stake in the case, was aimed at the protection of consumers and not solely at the protection of competitors and other operators in the market. Therefore, the UCPD was applicable (12).

1.1.2. Commercial practices which relate to a business-to-business transaction or which harm only competitors’ economic interests

|

Recital 6 This Directive […] neither covers nor affects the national laws on unfair commercial practices which harm only competitors’ economic interests or which relate to a transaction between traders; taking full account of the principle of full subsidiarity, Member States will continue to be able to regulate such practices in conformity with Community law, if they choose to do so […]. |

Business-to-business (B2B) commercial practices do not fall within the scope of the UCPD. They are partly regulated under the Misleading and Comparative Advertising Directive 2006/114/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council (13). Also, Directive (EU) 2019/633 of the European Parliament and of the Council (14) on unfair trading practices regulates B2B relationships in the agricultural and food supply chain. Member States may however extend, under their national laws, the protection granted under the UCPD to B2B commercial practices.

A national provision does not fall within the scope of the UCPD ‘if it aims solely, as argued by the referring court, at regulating relations between competitors and does not aim at protecting consumers (15)’.

Only those national measures which protect exclusively competitors’ interests fall outside the scope of the UCPD. Where national measures regulate a practice with the dual aim of protecting consumers and competitors, they are covered by the UCPD.

Regarding the distinction between consumers’ and competitors’ interests, the Court considered that:

|

‘39 |

[…] As is evident from recital 6 in the preamble to [the UCPD], only national legislation relating to unfair commercial practices which harm ‘only’ competitors’ economic interests or which relate to a transaction between traders is thus excluded from that scope. |

|

40 |

[…] that is quite clearly not the case with the national provisions [that] refer expressly to the protection of consumers and not only to that of competitors and other market participants.’ (16) |

It is for national authorities and courts to decide whether a national provision is intended to protect consumers’ economic interests.

The Court noted that:

|

‘29 |

It is therefore for the national court and not for this Court to establish whether the national provisions […] concerning price reduction announcements to consumers, actually pursue objectives relating to consumer protection, in order to determine whether such provisions are liable to fall within the scope of the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive […].’ (17) |

The Court has also found that the UCPD precludes a national provision prohibiting sales at loss only in so far as its aim is to protect consumers (18).

Regarding national rules prohibiting price reductions during pre-sales periods, the Court has clarified that such a prohibition is not compatible with the UCPD if it seeks to protect the economic interests of consumers (19).

1.2. Interplay between the Directive and other EU law

|

Article 3 (4) In the case of conflict between the provisions of this Directive and other Community rules regulating specific aspects of unfair commercial practices, the latter shall prevail and apply to those specific aspects. |

|

Recital 10 It is necessary to ensure that the relationship between this Directive and existing Community law is coherent, particularly where detailed provisions on unfair commercial practices apply to specific sectors. […] This Directive accordingly applies only in so far as there are no specific Community law provisions regulating specific aspects of unfair commercial practices, such as information requirements and rules on the way the information is presented to the consumer. It provides protection for consumers where there is no specific sectorial legislation at Community level and prohibits traders from creating a false impression of the nature of products. This is particularly important for complex products with high levels of risk to consumers, such as certain financial services products. This Directive consequently complements the Community acquis, which is applicable to commercial practices harming consumers’ economic interests. |

Due to its general scope, the Directive applies to many commercial practices which are also regulated by other general or sector-specific EU legislation.

1.2.1. Relationship with other EU legislation

Article 3(4) and Recital 10 are key features of the UCPD. They clarify that the UCPD complements other EU legislation (‘Community rules’) that regulate specific aspects of unfair commercial practices. Consequently, the UCPD works as a ‘safety net’ ensuring that a high common level of consumer protection against unfair commercial practices can be maintained in all sectors, including by complementing and filling gaps in other EU law.

Where EU law, sector-specific or other, is in place and its provisions overlap with the provisions of the UCPD, the corresponding provisions of the lex specialis will prevail. Article 3(4) of the Directive clarifies indeed that ‘in case of conflict between the provisions of this Directive and other Community rules regulating specific aspects of unfair commercial practices, the latter shall prevail and apply to those specific aspects’.

Article 3(4) read in conjunction with Recital 10 implies that a provision of EU law will prevail over the UCPD if all of the following three conditions are fulfilled:

|

— |

it has the status of EU law, |

|

— |

it regulates a specific aspect of commercial practices, and |

|

— |

there is a conflict between the two provisions or the content of the other EU law provision overlaps with the content of the relevant UCPD provision, for instance by regulating the conduct at stake in a more detailed manner and/or by being applicable to a specific sector (20). |

|

For example: Article 12 of the Mortgage Credit Directive (21) prohibits, in principle, tying practices whereby a credit agreement for a mortgage is sold with another financial product and is not made available separately. This per se prohibition conflicts with the UCPD because tying practices would be unfair and thus prohibited under the UCPD only following a case-by-case assessment. Its Article 12 prevails over the general rules of the UCPD. Thus, tying practices within the meaning of Article 12 of the Mortgage Credit Directive are prohibited as such. |

Where all three conditions set out above are fulfilled, the UCPD will not apply to the specific aspect of the commercial practice regulated, for example, by a sector-specific rule. The UCPD continues nonetheless to remain relevant to assess other possible aspects of the commercial practice not covered by the sector-specific provisions, such as, for example, aggressive behaviour by a trader.

|

For example: In order to switch to a different telecom provider, a consumer is required by his or her current provider to fill in a form. However, the form is not accessible online and the provider is not replying to the consumer's emails/phone-calls. Article 106 of the European Electronic Communications Code (EECC) (22) provides that, when switching, subscribers may retain their phone number, that the porting of numbers shall be carried out within the shortest possible time and that no direct charges are applied to end-users. The EECC also provides in Article 106(6) that providers must cooperate in good faith and must not delay or abuse the process. National regulatory authorities are responsible for ensuring the efficiency and simplicity of the switching process for the end-user. Furthermore, traders’ practices regarding the switching can be assessed under Articles 8 and 9(d) UCPD, which prohibit disproportionate non-contractual barriers to switching as an aggressive commercial practice. |

It follows from the above that, in general, the application of the UCPD is not per se excluded just because other EU legislation is in place which regulates specific aspects of unfair commercial practices.

In the Abcur case (23), the Court noted:

‘(…) the referring court asks, in essence, whether, if medicinal products for human use […] fall within the scope of Directive 2001/83, advertising practices relating to those medicinal products […] can also fall within the scope of Directive 2005/29.(…)

As the Court has already held, Directive 2005/29 is characterised by a particularly wide scope ratione materiae which extends to any commercial practice directly connected with the promotion, sale or supply of a product to consumers. (…)

the answer (…) is that even where medicinal products for human use, such as those at issue in the main proceedings, fall within the scope of Directive 2001/83, advertising practices relating to those medicinal products […] can also fall within the scope of Directive 2005/29 provided that the conditions for application of that directive are satisfied.’

Therefore the UCPD can usually be applied together with sector-specific EU rules in a complementary manner because the more specific requirements laid down under other EU rules usually add to the general requirements set out in the UCPD. Typically, the UCPD can be used to prevent traders from providing the information required by the sector specific legislation in a misleading or aggressive manner, unless this aspect is specifically regulated by the sector-specific rules.

The interplay with the information obligations in sector-specific EU instruments was highlighted in the Dyson v BSH case (24). The case concerned the labelling of vacuum cleaners and whether the lack of specific information about testing conditions, which is not required under the sector-specific rules at hand (25), could constitute a misleading omission. The Court confirmed that, in case of conflict between the UCPD and sector-specific legislation, the latter will prevail, which in this case meant that information that is not required by the EU energy label cannot be considered as ‘material information’ and that other information cannot be displayed.

The interplay with sector-specific rules was also addressed in the Mezina case (26). The case concerned health claims that were made in relation to natural food supplements. Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council (27) on nutrition and health claims made on foods applies to nutrition and health claims made in commercial communications, whether in the labelling, presentation or advertising of foods to be delivered as such to the final consumer. In case of conflict between the provisions of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 and the UCPD, the former will take precedence in relation to health claims.

1.2.2. Information established by other EU law as ‘material’ information

The UCPD provides that information requirements in relation to commercial communication established by other EU law are ‘material’.

|

Article 7(5)

|

Such information requirements are found in a number of pieces of sector-specific EU legislation. For example:

|

— |

environment (e.g. Energy Labelling Framework Regulation (28) and related delegated Regulations, Ecodesign Directive (29) and related delegated Regulations, Tyre Labelling Regulation (30), Fuel Economy Directive (31)); |

|

— |

financial services (e.g. Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (32), Payment Services Directive (33), Consumer Credit Directive (34), Mortgage Credit Directive (35), Payment Accounts Directive (36), Regulation on key information documents for PRIIPs (37)); |

|

— |

health (e.g. Directive 2001/83/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council (38)); |

|

— |

electronic communications services (European Electronic Communications Code (39)); |

|

— |

transport (e.g. Air Services Regulation (40), passenger rights Regulations (41)) |

|

— |

food area (e.g. General Food Law Regulation (42), Food Information to Consumers Regulation (43)). |

Such information requirements will often be more specific than the information requirements of the UCPD.

Article 7(5) of the UCPD clarifies that such information requirements ‘ shall be regarded as material ’.

|

For example: Article 23 of the Air Services Regulation requires air carriers, their agents and other ticket sellers, when offering flight tickets, to break down the final price by components (e.g. air fare, taxes, airport charges, and other charges and fees, such as those related to security and fuel). This constitutes material information within the meaning of Article 7(5) of the UCPD. |

Accordingly, failing to provide such information can qualify as a misleading commercial practice under the UCPD subject to the general transactional decision test, i.e. if the omission causes or is likely to cause the average consumer to take a transactional decision they would not have taken otherwise. The concept of ‘material information’ within the meaning of the UCPD is discussed in section 2.9.1.

Recital 15 provides that Member States can retain or add information requirements relating to contract law where this is permitted by minimum harmonisation clauses found in existing EU legal instruments.

|

For example: Member States can introduce additional pre-contractual requirements for on-premises sales, which are subject to the minimum harmonisation clause in Article 5(4) of the Consumer Rights Directive. |

1.2.3. Interplay with the Consumer Rights Directive

The Consumer Rights Directive (44) (CRD) applies to all business-to-consumer contracts except in the areas that are excluded from its scope, such as financial and healthcare services. It fully harmonises pre-contractual information requirements for distance (including online) and off-premises contracts (i.e. contracts that are not concluded in regular brick-and-mortar shops, see Article 2(8) CRD for the full definition). At the same time, as stipulated in Article 6(8) of the CRD, the Directive does not prevent Member States from imposing additional information requirements in accordance with the Services Directive 2006/123/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council (45) and the e-Commerce Directive 2000/31/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council (46) (for further information, see Guidance on the CRD, section 4.1.1 (47)). As regards other contracts, in particular those concluded in regular brick-and-mortar shops (‘on-premises’ contracts), the Directive allows Member States to adopt or maintain additional pre-contractual information requirements (Article 5(4)). CRD also regulates certain contractual rights, in particular the right of withdrawal.

The pre-contractual information requirements in the CRD are more detailed than the information requirements in Article 7(4) of the UCPD for the invitations to purchase. An invitation to purchase under the UCPD refers to both the information provided at the marketing stage (advertising) and before the contract is signed. In the latter case, there may be an overlap between the information requirements under Article 7(4) of the UCPD and the pre-contractual information requirements under the CRD. The difference between pre-contractual information and an invitation to purchase is further explained in section 2.9.5.

Given the more exhaustive character of the information requirements in the CRD, complying with the requirements laid down by the CRD for the pre-contractual stage should normally also ensure compliance with Article 7(4) UCPD, as far as the content of the information is concerned. However, the UCPD will still be applicable for assessing any misleading or aggressive commercial practices by a trader, including as regards the form and presentation of this information to the consumer.

Another example of complementarity between the two instruments concerns the consequences of ‘inertia selling’ practices, which are prohibited under points 21 and 29 of the Annex I to the UCPD. Article 27 CRD clarifies that, in the case of inertia selling, the ‘consumer shall be exempted from the obligation to provide any consideration’ and in such cases ‘the absence of response from the consumer (…) shall not constitute consent’.

The concept of inertia selling has been further interpreted by the Court. It clarified that since neither the CRD nor UCPD regulate the formation of contracts, it is for national courts to assess, in accordance with national legislation, whether a contract may be regarded as concluded, for example, between a water supply company and a consumer in the absence of the latter’s express consent (48).

In this context, the Court also clarified that point 29 of Annex I does not cover a commercial practice of a drinking water supply company maintaining the connection to the public water supply network when a consumer moves into a previously occupied dwelling, in a situation where the consumer does not have the choice of the supplier of that service, the supplier charges cost-covering, transparent and non-discriminatory rates that are proportionate to the water consumption, and the consumer knows that that dwelling is connected to the public water supply network and that water is supplied against payment (49).

The Court has furthermore clarified that Article 27 CRD, read in conjunction with Article 5(1) and (5) UCPD, does not preclude a national law that requires the owners of an apartment in a building in co-ownership connected to a district heating network to contribute to the costs of the consumption of thermal energy by the common parts and the internal installation of the building, even though they did not individually request the supply of that thermal energy and they do not use it in their apartment since the contract was concluded at the request of the majority of the owners (50).

1.2.4. Interplay with the Unfair Contract Terms Directive

The Unfair Contract Terms Directive (51) (UCTD) applies to all business-to-consumer contracts and concerns contractual terms which have not been individually negotiated in advance (e.g. pre-formulated standard clauses). Contractual terms may be regarded as unfair based on a general prohibition (52), an indicative list of potentially unfair terms (53) or an obligation to draft terms transparently, i.e. in plain, intelligible language (54). In contrast to the UCPD, which is without prejudice to contract law and does not provide for the invalidity of contracts that result from unfair commercial practices, breaches of the UCTD have contractual consequences: under Article 6(1) of that directive, unfair terms used in a contract with a consumer must ‘not be binding on the consumer’ (55).

The UCTD applies to business-to-consumer contracts in all sectors of economic activity, meaning that it may apply in parallel to other provisions of EU law, including other consumer protection rules such as the UCPD.

The Court has clarified certain elements of the relationship between these two Directives in the Pereničová and Perenič case, which concerned a credit agreement where the annual percentage rate of charge indicated was lower than the actual rate (56).

The Court concluded that such erroneous information about the total price of the credit provided in the contract terms is ‘misleading’ within the meaning of the UCPD if it causes, or is likely to cause, the average consumer to take a transactional decision that they would not have taken otherwise.

The fact that a trader resorted to such an unfair commercial practice is one of the elements to be considered in the assessment of unfairness of contractual terms under the UCTD (57). In particular, this element may be used to establish whether a contract term which is based on it creates a ‘significant imbalance’ in the rights and obligations arising under the contract, to the detriment of the consumer, under Article 3(1) and Article 4(1) of the UCTD. Similarly, this element could be relevant in assessing whether a contract term is transparent under Articles 4(2) and 5 of the UCTD (58). At the same time, a finding that a trader resorted to an unfair commercial practice has no direct effect on whether the contract is valid under Article 6(1) of that Directive, without prejudice to any national rules pursuant to which the contract entered into on the basis of unfair commercial practices is void as a whole (59).

The Court has not ruled directly on whether, in reverse, the use of unfair contract terms under the UCTD is to be regarded as an unfair commercial practice under the UCPD. It can be argued nevertheless that the use of such unfair contract terms, that are non-binding on the consumer as a matter of law, may in some cases be relevant for the identification of an unfair commercial practice. In particular, it can be the mark of a misleading action pursuant to Article 6 of the UCPD, insofar as it results in false information or in misleading the average consumer about the rights and obligations of the parties under the contract. In addition, the recourse to non-transparent contract terms, which are not drafted in plain and intelligible language as set out in Articles 4(2) and 5 of the UCTD, should be taken into account when assessing the transparency of material information and the existence of a misleading omission pursuant to Article 7 of the UCPD (60). Furthermore, the use of unfair contract terms could indicate that a trader has failed to meet the requirements of professional diligence under Article 5 of the UCPD.

Only a few Member States’ consumer protection authorities have specific powers in the area of contract terms to prohibit the use of non-negotiated standard contract terms which they consider to be unfair without having to take the trader to court (61).

The Court has consistently held that national courts are under an obligation to assess unfair contract terms of their own motion (ex officio) (62), i.e. even if the unfairness of contract terms is not raised by the consumer. The obligation stems from Article 6(1) of the UCTD, which provides that unfair terms are not to be binding on the consumer, as well as from the principle of effectiveness which requires that national implementing measures do not make it in practice impossible or excessively difficult to exercise the rights conferred on consumers by EU law (63). The requirement of an ex officio control has been justified by the consideration that the system of protection established by the UCTD is based on the idea that the consumer is in a weak position vis-à-vis the trader as regards both the bargaining power and level of knowledge, which leads to the consumer agreeing to terms drawn up in advance by the trader without being able to influence the content of those terms (64). Therefore, there is a real risk that consumers, particularly because of a lack of awareness, will not rely on the legal rule that is intended to protect them.

The Court recalled in the Bankia case (65) that a national court which assesses the fairness of contract terms in the light of the UCTD, including of its own motion, has the possibility to assess, in the context of that review, the unfairness of a commercial practice on which that contract was based (66).

By contrast, the Court ruled that, in the other cases, national courts are not obliged to assess ex officio whether a particular contract or any of its terms has been concluded under the impact of unfair commercial practices (67). In particular, the Court found that, during mortgage enforcement proceedings, it is not necessary for national courts to be able to review whether the enforceable instrument breaches the UCPD because this directive does not place such an obligation on the national courts.

This interpretation has been justified by the fact that the UCPD does not provide for contractual consequences, unlike Article 6(1) of the UCTD. Moreover, the Court explained that the UCPD, in particular its Article 11, does not contain requirements similar to Article 7(1) of the UCTD, which precludes national legislation that does not provide for the possibility of interim measures in enforcement procedures. The absence of interim relief would limit the remedies available to consumers under the UCTD to a mere subsequent protection of a purely compensatory nature if the enforcement is carried before the judgment of the court declaring unfair the contract term on which the mortgage is based and annulling the enforcement proceedings (68).

However, Directive (EU) 2019/2161 on better enforcement and modernisation of Union consumer protection rules introduces individual remedies for victims of breaches of the provisions of the UCPD in a new Article 11a of the UCPD, applicable as from 28 May 2022. Under this new provision consumers harmed by unfair commercial practices should have access to proportionate and effective remedies, including compensation for damage suffered by the consumer and, where relevant, a price reduction or the termination of the contract (see section 1.4 for additional information). The addition of that clear and unequivocal new provision may entail an extension of the requirement of an ex officio control to the unfair commercial practices under the UCPD (to be confirmed by the Court).

1.2.5. Interplay with the Price Indication Directive

The Price Indication Directive 98/6/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council (69) (PID) requires traders to indicate the selling price and the unit price (price per unit of measurement) of goods in order to facilitate price comparison by consumers. Furthermore, Directive (EU) 2019/2161 added to the PID specific rules concerning ‘price reductions’.

Concerning the interplay between the UCPD and the requirements of the PID regarding the indication of the selling price, the Court clarified in Citroën (paragraphs 44 to 46) that the PID regulates specific aspects of unfair commercial practices in dealings between businesses and consumers for the purpose of Article 3(4) UCPD, namely, those that relate to the indication, in offers for sale and in advertising, of the goods’ selling price (70). Therefore, the PID applies, rather than the UCPD (Article 7(4)(c)) ‘ in so far as the aspect relating to the selling price referred to in an advertisement such as that at issue in the main proceedings is governed by Directive 98/6’.

In this case the relevant aspect was the trader’s failure to indicate as selling price the final price, i.e. price including additional compulsory costs that were mentioned separately in the advertisement for the car. Accordingly, Article 2 of the PID, which defines selling price as the final price for the good including VAT and all other taxes, does not prevent the application of other requirements of Article 7(4)(c) of the UCPD that are not governed by it. In particular, traders must comply with the UCPD requirement for an invitation to purchase to include also information about possible additional charges where those cannot reasonably be calculated in advance.

The amendments introduced to the PID by Directive (EU) 2019/2161 require Member States to adopt specific rules on price reductions (71). According to Article 6a, the trader announcing a ‘price reduction’ must indicate the ‘prior price’ which is defined as the lowest price charged by that trader during the past period of at least 30 days.

By analogy with the Court’s findings in Citroën, the specific rules of the PID on price reductions should prevail over the UCPD regarding those aspects of price reduction that are governed by these specific rules, namely, the definition and indication of the ‘prior’ price when announcing price reduction. However, the UCPD remains applicable to other aspects of price reductions, in particular Article 6(1)(d) on the misleading claims about the existence of price advantage. It could apply, for instance, to different misleading aspects of price reduction practices, such as:

|

— |

excessively long periods during which announcements of price reductions apply compared to the period during which the goods are sold at ‘full’ price; |

|

— |

advertising a promotion of, for example, ‘up to 70 % off’ when only a few of the items are reduced at 70 % and the rest are reduced at a lower percentage. |

Such practices could be found to be in breach of the UCPD (Article 6(1)(d)), subject to a case-by-case assessment, notwithstanding the fact that the trader has complied with the requirements of the PID as regards the definition and indication of the ‘prior’ price. Conversely, a trader found in breach of the PID rules on price reductions, i.e. definition and display of the ‘prior price’, could also be found in breach of the UCPD.

Moreover, the PID applies only to tangible goods and not to services and digital content, hence the general UCPD rules continue to be fully applicable to the price reduction practices regarding such other products.

Finally, as the PID applies only to ‘price reductions’ as specifically defined therein, the UCPD remains fully applicable and governs other types of practices promoting price advantages, such as comparisons with other prices, combined or tied conditional offers and loyalty programmes (see section 2.8.2). The UCPD also applies to personalised prices (see section 4.2.8.).

1.2.6. Interplay with the Misleading and Comparative Advertising Directive

The Misleading and Comparative Advertising Directive (72) (MCAD) covers business-to-business (B2B) relations. However, its rules on comparative advertising continue to provide a general test, based on fully harmonised criteria, for assessing whether comparative advertising is lawful also in business-to-consumer (B2C) transactions (73).

Article 6(2)(a) of the UCPD qualifies as misleading a practice which, including through comparative advertising, creates confusion with any products, trademarks, trade names or other distinguishing marks of a competitor. At the same time, under Article 4(a) of the MCAD, comparative advertising is not permitted if it is misleading under Articles 6 and 7 of the UCPD.

Hence, these two Directives cross-reference each other. Being relevant for both B2C and B2B transactions, the conditions for assessing the lawfulness of comparative advertising laid down by Article 4 of the MCAD are rather broad and include also some aspects of unfair competition (e.g. denigration of trade marks). Therefore, the MCAD will either provide conditions for such assessment under the UCPD for B2C transactions or impose additional requirements which are relevant for traders, mainly competitors, in B2B transactions.

For those Member States which have extended all or part of the provisions contained in the UCPD to B2B transactions, the UCPD provisions as transposed into national laws will in practice replace the relevant MCAD provisions in B2B relations. It should be noted that some countries have also adopted specific rules for B2B.

The Court examined the interplay between the MCAD and the UCPD in the Carrefour case (74), which concerned comparative advertising that may be misleading under Article 7 of the UCPD. The practice involved advertising comparing the prices of products sold in shops having different sizes or formats, where those shops are part of retail chains each of which includes a range of shops having different sizes or formats (e.g. hypermarkets and supermarkets) and where the advertiser compares the prices charged in shops having larger sizes or formats in its retail chain with those displayed in shops having smaller sizes or formats in the retail chains of competitors. The Court considered that this type of advertising practice could be unlawful within the meaning of Article 4(a) and (c) of the MCAD, read in conjunction with Article 7(1) to (3) of the UCPD, unless consumers are informed clearly and in the advertisement itself that the comparison was made between the prices charged in shops in the advertiser’s retail chain having larger sizes or formats and those indicated in the shops of competing retail chains having smaller sizes or format (75).

1.2.7. Interplay with the Services Directive

Contrary to sector-specific legislation, the Services Directive (76) has a broad scope of application. It applies to services in general as defined in the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, with certain exceptions. It can therefore not be considered as lex specialis to the UCPD within the meaning of Article 3(4).

Accordingly, the information requirements in Article 22 of the Services Directive apply in addition to the information required for invitations to purchase under Article 7(4) of the UCPD.

1.2.8. Interplay with the e-Commerce Directive

The e-Commerce Directive (77) applies to information society services, which will normally include the services provided by operators of websites and online platforms which allow consumers to buy a good or service.

Article 5 of the e-Commerce Directive lays down general information requirements for service providers, while Article 6 lays down information to be provided in commercial communications. The information requirements set out in these two articles are of minimum nature.

Article 6 in particular requires Member States to ensure that traders clearly identify promotional offers, such as discounts, premiums and gifts, where permitted in the Member States where the service provider is established, and the conditions to qualify for such promotional offers.

The Commission published on 15 December 2020 proposals for a Digital Services Act (78) (DSA) and for a Digital Markets Act (79) (DMA). The DSA aims to update and extend the rules on ecommerce and platforms in the EU, and the DMA aims to impose additional obligations on certain services operated by so-called gatekeepers (80).

1.2.9. Interplay with the Audiovisual Media Services Directive

The Audiovisual Media Services Directive (81) (AVMSD) applies to linear and nonlinear audiovisual media services (i.e. TV broadcasting and on-demand media services), which can include audiovisual commercial communications which directly or indirectly promote goods or services (e.g. television advertising, sponsorship, teleshopping or product placement).

Article 5 of the AVMSD lays down general information requirements for service providers, while Article 9 lays down requirements with which all audiovisual commercial communications must comply. Articles 10 and 11 respectively lay down the conditions which sponsorship and product placement in audiovisual media services must respect. The AVMSD also provides for other stricter criteria which apply only to television advertising and teleshopping (Chapter VII on television advertising and teleshopping).

The 2018 revision of the Directive (82) has extended some of these rules to video-sharing platforms (Article 28b). They must now comply with the requirements laid down in Article 9(1) with respect to audiovisual commercial communications that are marketed, sold or arranged by themselves and take appropriate measures to ensure compliance with respect to audiovisual commercial communications that are not marketed, sold or arranged by themselves. The revised Directive also includes disclosure requirements for audiovisual commercial communications in video-sharing platforms. The Commission has adopted Guidelines (83) on the practical application of the definition of a video-sharing platform service.

The UCPD applies to unfair commercial practices occurring in audiovisual media services, such as misleading and aggressive practices, to the extent that they are not covered by the provisions mentioned above.

1.2.10. Interplay with the General Data Protection Regulation and the e-Privacy Directive

The respect for private and family life and the protection of personal data are fundamental rights under Articles 7 and 8 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. Under Article 7, everyone has the right to respect for his or her private and family life, home and communications. As regards the protection of personal data, Article 8(2) of the Charter contains key data protection principles (fair processing, consent or legitimate aim prescribed by law, right to access and rectification). Article 8(3) of the Charter requires that compliance with data protection rules be subject to control by an independent authority (84).

The General Data Protection Regulation (85) (GDPR) regulates the protection of personal data and the free movement of such data. Data protection rules are enforced by national supervisory authorities and national courts. The GDPR applies to the processing of ‘personal data’. Personal data means any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (‘data subject’). An identifiable person is someone who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identification number or to one or more factors specific to his or her physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity.

The processing of personal data, which includes collecting and storing personal data, must be fair and lawful. One aspect of fair processing is that the data subject is given relevant information, including on the purposes of that processing, having regard to the specific circumstances in which the data are collected. Fair and lawful processing of personal data requires that data protection principles are complied with and that at least one of the six grounds for legitimate processing applies to any processing activity (see Article 6(1) GDPR). Consent by the individual is one of these grounds. Another is where a controller is under a legal obligation imposed by Union or Member State law to process the data (e.g. know-your-customer obligation).

The e-Privacy Directive (86) particularises and complements the GDPR regarding the processing of personal data in the electronic communication sector, as it facilitates the free movement of such data and of electronic communication equipment and services. In particular, Article 5(3) of the e-Privacy Directive requires the user’s consent when ‘cookies’ or other forms of accessing and storing information on an individual’s device (e.g. tablet or smartphone) are used, except where such storage or access is necessary for carrying out the transmission of a communication or for the provision of an information society service explicitly requested by a user.

Data-driven business structures are becoming predominant in the online world. In particular, online platforms analyse, process and sell data related to consumer preferences and other user-generated content. This, together with advertising, often constitutes their main source of revenues. The collection and processing of personal data in these types of situations must comply with the legal requirements under the ePrivacy Directive and GDPR mentioned above.

A trader’s violation of the GDPR or of the ePrivacy Directive will not, in itself, always mean that the practice is also in breach of the UCPD. However, such privacy and data protection violations should be considered when assessing the overall unfairness of commercial practices under the UCPD, particularly in the situation where the trader processes consumer data in violation of privacy and data protection requirements, i.e. for direct marketing purposes or any other commercial purposes like profiling, personal pricing or big data applications.

From a UCPD perspective, the first issue to be considered concerns the transparency of the commercial practice. Under Articles 6 and 7 of the UCPD, traders should not mislead consumers on aspects that are likely to have an impact on their transactional decisions. More specifically, Article 7(2) and No 22 of Annex I prevent traders from hiding the commercial intent behind the commercial practice. See also section 3.4 on the use of the claim ‘free’ to describe digital products, which could be in breach of No 20 of Annex I.

Furthermore, the information requirements from the GDPR and e-Privacy Directive may be considered as material information under the UCPD Article 7(5). Personal data, consumer preferences and other user-generated content have economic value and are often being made available to third parties. Consequently, under Article 7(2) and No 22 of Annex I UCPD, if the trader does not inform a consumer that the data provided will be used for commercial purposes, this could be considered a misleading omission of material information, as well as a breach of transparency and other requirements under Articles 12 to 14 of the GDPR.

1.2.11. Interplay with Articles 101-102 TFEU (EU competition rules)

Council Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 (87) provides the legal framework for implementing the competition rules laid down in Articles 101 and 102 TFEU. Both Articles are without prejudice to the UCPD.

Article 101(1) TFEU prohibits in certain circumstances agreements between undertakings, decisions by associations of undertakings and concerted practices, such as fixing purchase or selling prices or other trading conditions, which have as their object or effect the prevention, restriction or distortion of competition in the EU.

Article 102 TFEU prohibits, in certain circumstances, the abuse of a dominant position by one or more undertakings. Such an abuse may, for example, consist in applying dissimilar conditions to equivalent transactions with other trading parties, thereby placing them at a competitive disadvantage, or directly or indirectly imposing unfair purchase or selling prices.

The fact that a given conduct is in breach of Articles 101 or 102 TFEU does not automatically mean that it is also unfair under the UCPD (or vice versa). The breach of competition rules should, however, be taken into account when assessing the unfairness of commercial practices under the UCPD insofar as they may be considered contrary to the general clause of Article 5(2) UCPD concerning ‘professional diligence’.

1.2.12. Interplay with the EU Charter of fundamental rights

According to its Article 51(1), the EU Charter of fundamental rights applies to the Member States when they implement Union law, thus also when they implement the provisions of the UCPD. The Charter contains provisions, among others, on the protection of personal data (Article 8), the rights of the child (Article 24), consumer protection (Article 38) and the right to an effective remedy and a fair trial (Article 47).

The Court has stressed the significance of Article 47 of the Charter on access to justice in relation to remedies available to consumers in connection with consumer rights granted under EU directives. The principle of effectiveness, as referred to by the Court, means that national rules of procedure may not make it excessively difficult or impossible in practice for consumers to exercise rights conferred by EU law (88).

1.2.13. Interplay with Articles 34-36 TFEU

A national measure in an area which has been the subject of exhaustive harmonisation at EU level must be assessed in the light of the provisions of that harmonising measure and not those of the Treaty of the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) (89). Thus, when a national measure falls within the scope of the UCPD (discussed in sections 1.1 and 1.2 above), it should be assessed against the UCPD and not against the TFEU.

National measures that neither fall within the scope of the UCPD nor under any other harmonising instrument of secondary EU law are to be assessed under Articles 34-36 TFEU. The prohibition of measures having an effect equivalent to quantitative restrictions as laid down in Article 34 TFEU covers all trading rules enacted by Member States which are capable of hindering, directly or indirectly, actually or potentially, intra-Union trade (90). See also the Commission Notice Guide on Articles 34-36 TFEU for further guidance on the application of these provisions (91).

The issue of when a national rule is capable of hindering intra-Union-trade has been dealt with extensively by the Court. Notably, in Keck (92) the Court held that national provisions restricting or prohibiting certain selling arrangements are not such as to hinder directly or indirectly, actually or potentially trade between Member States, so long as, first, those provisions apply to all relevant traders operating within the national territory and, secondly, they affect in the same manner, in law and in fact, the marketing of domestic products and those from other Member States (93). The Court includes in the list of selling arrangements, measures relating to the conditions and methods of marketing (94), measures which relate to the time of the sale of goods (95), measures which relate to the place of the sale of goods or restrictions regarding by whom goods may be sold (96) and measures which relate to price controls (97).

Some of the examples of selling arrangements mentioned in the jurisprudence of the Court, notably national provisions that regulate the conditions and methods of marketing, would fall within the scope of the UCPD if they concern business-to-consumer commercial practices and are intended to protect the economic interest of consumers.

Many commercial practices that do not fall within the scope of the UCPD or other secondary EU law would appear to qualify as selling arrangements under Keck. Such selling arrangements fall within the scope of Article 34 TFEU if they, in law or in fact, introduce discrimination on the basis of the origin of products. Discrimination in law occurs when the measures are manifestly discriminatory, whilst discrimination in fact is more complex. Such measures would need to be assessed on a case-by-case basis.

If a measure or national practice violates Article 34 TFEU, it may in principle be justified under Article 36 TFEU or on the basis of one of the overriding requirements in the public interest recognised by the Court of Justice. It is for national authorities to demonstrate that the restriction on the free movement of goods is justified on one of these grounds (98). Furthermore, the Member State must demonstrate that its legislation is necessary to effectively protect the public interests invoked (99).

In order to be permissible, such provisions must be proportionate to the objective pursued and the objective must not be capable of being achieved by measures which are less restrictive of intra-EU trade (100). More recently the Court held that ‘in determining whether the restriction at issue is proportionate, it is also important to ascertain whether the measures implemented in that context go beyond what is necessary to attain the legitimate objective being pursued. In other words, it is necessary to determine whether there exist alternative measures that are also capable of attaining that objective while at the same time having a less restrictive effect on intra-Community trade’ (101). Moreover, the Court held that ‘it should be borne in mind in that context that a restrictive measure may be regarded as complying with the requirements of European Union law only if it genuinely reflects a concern to secure the attainment of the objective pursued in a consistent and systematic manner’ (102).

1.2.14. Interplay with the Platform-to-Business Regulation

The Platform-to-Business (P2B) Regulation (103) lays down rules to ensure that business users of online intermediation services and corporate website users in relation to online search engines are granted appropriate transparency, fairness and effective redress possibilities. The transparency requirements of the P2B Regulation cover ranking of search results (Article 5).

The Commission has published guidelines on ranking transparency that aim to facilitate the compliance of providers of online intermediation services and providers of online search engines with the requirements (104).

A similar requirement concerning ranking transparency in the B2C area was introduced by Directive (EU) 2019/2161, which added to the UCPD a new point 4a in Article 7. It requires traders to provide consumers with information on the main parameters determining the ranking of products presented to the consumer as a result of the search query and the relative importance of those parameters. The interplay between the UCPD and the P2B Regulation in the area of ranking transparency is addressed in section 4.2.3.

1.3. The relationship between the UCPD and self-regulation

|

Article 2(f) ‘code of conduct’means an agreement or set of rules not imposed by law, regulation or administrative provision of a Member State which defines the behaviour of traders who undertake to be bound by the code in relation to one or more particular commercial practices or business sectors; |

|

Article 10 Codes of conduct This Directive does not exclude the control, which Member States may encourage, of unfair commercial practices by code owners and recourse to such bodies by the persons or organisations referred to in Article 11 if proceedings before such bodies are in addition to the court or administrative proceedings referred to in that Article. Recourse to such control bodies shall never be deemed the equivalent of foregoing a means of judicial or administrative recourse as provided for in Article 11. |

The UCPD recognises the importance of self-regulation mechanisms and clarifies the role that code owners and self-regulatory bodies can play in enforcement. Member States may encourage code owners to check for unfair commercial practices, in addition to enforcing the UCPD.

When the rules in self-regulatory codes are strict and rigorously applied by code owners and/or vigourously enforced by independent self-regulatory bodies, they may indeed reduce the need for administrative or judicial enforcement action. Moreover, when the standards are high and industry operators largely comply with them, such rules may be a useful reference point for national authorities and courts in assessing whether a commercial practice is unfair.

The UCPD contains several provisions which prevent traders from unduly exploiting the trust which consumers may have in self-regulatory codes. This is discussed in section 2.8.4 on non-compliance with codes of conduct.

1.4. Enforcement and redress

1.4.1. Public and private enforcement

According to Article 11 of the UCPD, Member States are required to ensure that adequate and effective means exist to combat unfair commercial practices in order to enforce compliance with the provisions of the Directive in the interest of consumers.

Such means include legal provisions under which persons or organisations regarded under national law as having a legitimate interest in combating unfair commercial practices, including competitors, may take legal action in national courts and/or before an administrative authority competent either to decide on complaints or to initiate appropriate legal proceedings.

Member States should ensure coordination in good faith between the different competent public enforcement authorities. In those Member States where different authorities are responsible for enforcing the UCPD and sector-specific legislation, the authorities should closely cooperate to ensure that the findings of their respective investigations into the same trader and/or commercial practice are consistent.

As regards the enforcement of the UCPD through legal action in the national courts, in the Movic case the Court of Justice confirmed that ‘an action where the opposing parties are the authorities of a Member State and businesses established in another Member State, in which those authorities seek, primarily, findings of infringements constituting allegedly unlawful unfair commercial practices and an order for the cessation of such infringements and, as ancillary measures, an order for publicity measures and the imposition of a penalty payment, falls within the scope of the concept of “civil and commercial matters” ’ in Article 1(1) Brussels I Recast Regulation (105).

In the area of private enforcement, Directive (EU) 2020/1828 of the European Parliament and of the Council (106) on representative actions for the protection of the collective interests of consumers introduced in all Member States the possibility of enforcing the UCPD through representative actions. Such actions could be brought forth by qualified entities, seeking injunctive and redress measures on behalf of the affected consumers.

Finally, persons who report breaches of the UCPD (and of the CRD) are covered by the protective regime of Directive (EU) 2019/1937 of the European Parliament and of the Council (107) (the Whistleblower Directive) pursuant to Article 2(1)a)(ix). By feeling safe to speak up, the number of whistleblowers’ reports will likely increase, thereby enhancing the enforcement of the UCPD.

1.4.2. Penalties

Article 13 of the UCPD deals with penalties for the infringement of the national rules transposing the Directive. Paragraph 1 requires Member States to lay down the rules on penalties applicable to infringements of national provisions adopted pursuant to the Directive. It leaves to Member States to decide on the type of the available penalties and to determine the procedures for the imposition of penalties, as long as they are effective, proportionate and dissuasive.

Directive (EU) 2019/2161 amended Article 13 and added additional requirements. Firstly, it provides a non-exhaustive indicative list of criteria for applying the penalties (paragraph 2). Secondly, it lays down more specific rules (paragraphs 3 and 4) on fines for widespread infringements and widespread infringements with a Union dimension that are subject to coordinated enforcement actions under Regulation (EU) 2017/2394 of the European Parliament and of the Council (108) on consumer protection cooperation (‘CPC Regulation’).

Recital 15 of Directive (EU) 2019/2161 encourages Member States to ‘consider enhancing the protection of the general interest of consumers as well as other protected public interests’ in the allocation of revenues from fines.

Article 13(5) requires Member States to notify the Commission of national rules on penalties and any subsequent amendments, i.e. by means of a specific notification explaining the exact national provisions concerned and not merely as part of the general notification of transposition measures.

Article 13(2) sets out a list of six non-exhaustive and indicative criteria that Member States’ competent authorities and courts should take into account when imposing the penalties. They apply on a ‘where appropriate’ basis to infringements, both domestically and in cross-border situations:

|

Article 13

|

Recital 7 of Directive (EU) 2019/2161 explains some of the criteria. Recital 8 clarifies that they ‘might not be relevant in deciding on penalties regarding every infringement, in particular regarding non-serious infringements.’ Moreover, ‘Member States should also take account of other general principles of law applicable to the imposition of penalties, such as the principle of non bis in idem.’

Intentional nature of the infringement is relevant for the application of the criteria set out in points (a) and (f). However, intention is not a necessary condition for the imposition of penalties in case of infringement.

The criterion set out in point (c) covers the relevant trader’s same or different past infringements on the UCPD.

The criterion set out in point (e) concerns cases where the same infringement has occurred in several Member States. It only applies where information about penalties imposed by other Member States in respect of the same infringement is available through the co-operation mechanism established under the CPC Regulation.

Depending on the circumstances of the case, the penalties imposed on the same trader in other Member State(s) for the same infringement could indicate both greater scale and gravity under point (a) and/or qualify as a ‘previous infringement’ under point (c). Therefore, penalties imposed for the same infringement in other Member States could be an aggravating factor. The imposition of penalties in other Member States for the same infringement could also be considered in conjunction with other ‘aggravating’ circumstances covered by the other criteria referred to point (f) that generally refers to ‘any other’ aggravating or mitigating circumstances. However, a penalty imposed by another Member State on the same trader for the same infringement can also be relevant for the application of the non bis in idem principle in accordance with national law and Article 10(2) of the CPC Regulation (109).

Articles 13(3) and (4) provide additional, more prescriptive rules (compared to the general rule in paragraph 1) regarding penalties that must be available under national law for infringements that are subject to coordinated actions under the CPC Regulation.

Article 21 of the CPC Regulation requires Member States’ competent authorities concerned by the coordinated action to take enforcement measures, including the imposition of penalties, in an effective, efficient and coordinated manner against the trader responsible for the widespread infringement or the widespread infringement with a Union dimension. ‘Widespread infringements’ and ‘widespread infringement with a Union dimension’ are cross-border infringements defined in Article 3(3) and (4) of the CPC Regulation (110).

For this category of infringements, Article 13(3) UCPD requires Member States to provide for the possibility of imposing fines and the maximum amount of fine must be at least 4 % of the trader’s annual turnover. Accordingly, Member States can set the threshold of the maximum fine also higher than 4 % of the trader’s annual turnover. They can also choose to apply the fine based on a larger reference turnover, such as trader’s worldwide turnover. Likewise, they can extend the penalties available in the event of CPC coordinated actions to other types of infringements, such as domestic ones.

When information on the trader’s annual turnover is not available, for example, in case of recently established companies, Article 13(4) requires Member States to provide for the possibility of imposing a maximum fine of at least EUR 2 million. Again, Member States can set the threshold of the maximum fine also higher than EUR 2 million.

This harmonisation of national rules on fines aims to ensure that enforcement measures are possible and coherent in all Member States participating in a CPC coordinated enforcement action.

The imposition of fines in accordance with Articles 13(3) and (4) of the UCPD is subject to the common criteria laid down in Article 13(2), including in particular ‘the nature, gravity and duration or temporal effects of the infringement’. The actual fine imposed by the competent authority or court in a specific case can be lower than the maximum amounts described above, depending on the nature, gravity and other relevant characterstics of the infringement.

Subject to the coordination obligations under the CPC Regulation, the competent authority or court can decide to impose periodic fines (such as daily fines) until the trader stops the infringement. It could also decide to impose the fine conditionally if the trader fails to stop the infringement within the prescribed term despite the injunction to that effect.

The relevant turnover to be taken into account for the calculation of the fine is the turnover achieved in the Member State imposing the fine. However, Article 13(3) also makes it possible to establish the fine based on the trader’s turnover achieved in all Member States concerned by the coordinated action if the CPC coordination results in a single Member State imposing the fine on behalf of the participating Member States.

Recital 10 of Directive (EU) 2019/2161 clarifies that ‘in certain cases, a trader can also be a group of companies’. Accordingly, where the trader responsible for the infringement is a group of companies, its combined group turnover in the relevant Member States will be taken into account for the calculation of the fine.

The Directive does not define the reference year for the definition of the annual turnover. Therefore, for establishing the fine, the national authorities may use, for example, the latest available annual turnover data at the time of the decision on the penalty (i.e. preceding business year).

Under Article 13(3), Member States may, for national constitutional reasons, restrict the imposition of fines to: (a) infringements of Articles 6, 7, 8, 9 and of Annex I to this Directive; and (b) a trader’s continued use of a commercial practice that has been found to be unfair by the competent national authority or court, when that commercial practice is not an infringement referred to in point (a). Accordingly, this restriction is meant to address circumstances of exceptional nature and allows Member State not to apply the provisions on fines to those one-off infringements subject to CPC coordinated enforcement for which the sole legal basis is Article 5 of the UCPD on professional diligence.

1.4.3. Consumer redress

Directive (EU) 2019/2161 added to the UCPD a new Article 11a requiring Member States to ensure that consumers harmed by the infringements of the UCPD have access to proportionate and effective remedies, in particular compensation for damage and, where relevant, price reduction and contract termination, subject to the conditions established at national level. Accordingly, consumer redress in the UCPD includes both contractual and non-contractual remedies.