ISSN 1977-091X

Official Journal

of the European Union

C 280

English edition

Information and Notices

Volume 64

13 July 2021

|

ISSN 1977-091X |

||

|

Official Journal of the European Union |

C 280 |

|

|

||

|

English edition |

Information and Notices |

Volume 64 |

|

Contents |

page |

|

|

|

IV Notices |

|

|

|

NOTICES FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES |

|

|

|

European Commission |

|

|

2021/C 280/01 |

Commission Notice – Technical guidance on sustainability proofing for the InvestEU Fund |

|

EN |

|

IV Notices

NOTICES FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES

European Commission

|

13.7.2021 |

EN |

Official Journal of the European Union |

C 280/1 |

COMMISSION NOTICE –

Technical guidance on sustainability proofing for the InvestEU Fund

(2021/C 280/01)

|

DISCLAIMER: The purpose of this notice is to give technical guidance on the screening and sustainability proofing of projects receiving InvestEU support, in line with recital (13) and Articles 8(5) and 8(6) of the InvestEU Regulation. This document was prepared by the Commission with the support of JASPERS and in cooperation with potential implementing partners. For the climate dimension, this document is consistent with the ‘Technical guidance on the climate proofing of infrastructure in the period 2021-2027’. This document also reflects, to the extent possible and relevant, the results of two studies. One study, ‘Technical Support Document for Environmental Proofing of Investments under the InvestEU Programme’, was run by DG Environment. The second study, ‘InvestEU Programme: Guidance on social sustainability proofing of investment and financing operations’, was run by DG Employment. The guidance on sustainability proofing should be used by the implementing partners, financial intermediaries and project promoters/final recipients involved in the deployment of the InvestEU Fund. The sustainability proofing guidance could be relevant for other programmes as well. The guidance may be updated in light of the experience with the implementation of the concerned EU legislation. The present guidance may be complemented with international, national or sectoral considerations or guidance. |

TABLE OF CONTENTS

|

1. |

INTRODUCTION | 5 |

|

1.1. |

Scope | 5 |

|

1.2. |

Legal compliance | 6 |

|

1.3. |

Thresholds | 7 |

|

1.4. |

Sustainability proofing guidance and criteria of the EU Taxonomy | 7 |

|

1.5. |

Mid-term evaluation and review of this guidance | 10 |

|

2. |

SUSTAINABILITY PROOFING FOR DIRECT FINANCING OPERATIONS | 10 |

|

2.1. |

General principles and overall proofing approach | 10 |

|

2.2. |

Climate dimension | 12 |

|

2.2.1. |

Introduction | 12 |

|

2.2.2. |

General approach to climate sustainability proofing | 13 |

|

2.2.3. |

Legal compliance | 15 |

|

2.2.4. |

Climate resilience | 16 |

|

2.2.5. |

Climate neutrality and mitigation of climate change | 21 |

|

2.2.6. |

Reporting and monitoring | 25 |

|

2.3. |

Environment dimension | 26 |

|

2.3.1. |

General approach to environmental proofing | 26 |

|

2.3.2. |

Legal compliance | 29 |

|

2.3.3. |

InvestEU screening for the environmental dimension | 33 |

|

2.3.4. |

Proofing: Mitigation, quantification and monetisation | 35 |

|

2.3.5. |

Positive agenda | 37 |

|

2.3.6. |

Reporting and monitoring | 37 |

|

2.4. |

Social dimension | 38 |

|

2.4.1. |

General approach to social sustainability proofing | 38 |

|

2.4.2. |

Legal compliance framework for the social dimension | 40 |

|

2.4.3. |

Social screening of operations | 40 |

|

2.4.4. |

Categorisation of social risk | 44 |

|

2.4.5. |

Social proofing | 47 |

|

2.4.6. |

Positive agenda | 54 |

|

2.4.7. |

Reporting and monitoring | 56 |

|

2.5. |

Horizontal provisions for the three dimensions | 56 |

|

2.5.1. |

Capacity of the project promoter | 56 |

|

2.5.2. |

Contractual arrangements | 57 |

|

2.6. |

Economic appraisal of operations | 57 |

|

2.6.1. |

Forms of economic appraisal | 58 |

|

2.6.2. |

Existing practices for economic appraisal | 59 |

|

2.6.3. |

Recommendations for InvestEU | 59 |

|

2.7. |

Corporate finance for general purposes | 60 |

|

3. |

SUSTAINABILITY PROOFING APPROACH FOR INDIRECT FINANCING OPERATIONS | 61 |

|

3.1. |

General proofing requirements | 61 |

|

3.2. |

Types of financing | 62 |

|

3.2.1. |

Infrastructure funds | 62 |

|

3.2.2. |

Non-infrastructure equity or debt funds | 64 |

|

3.2.3. |

Intermediated credit lines or other debt products targeting SMEs, small mid-caps and other eligible entities | 65 |

|

4. |

ROLES, RESPONSIBILITIES AND THE INVESTEU PROCESS | 66 |

|

4.1. |

Roles and responsibilities | 66 |

|

4.1.1. |

Role and responsibilities of the project promoter/final recipient | 66 |

|

4.1.2. |

Role and responsibilities of the implementing partner | 67 |

|

4.1.3. |

Role of the financial intermediary | 68 |

|

4.1.4. |

Role of the Investment Committee | 68 |

|

4.1.5. |

Role of the Commission | 68 |

|

4.1.6. |

Competent public authorities | 69 |

|

4.2. |

InvestEU process | 69 |

|

4.2.1. |

Policy check | 69 |

|

4.2.2. |

Guarantee request form | 70 |

|

4.2.3. |

Scoreboard | 70 |

|

4.2.4. |

Reporting to the Commission | 70 |

|

Annex 1 – |

List of legal requirements | 72 |

|

Annex 2 – |

Information to be provided to the InvestEU Investment Committee (Chapter 2) | 76 |

|

Annex 3 – |

Proofing checklists to be used by implementing partners for proofing under each dimension | 79 |

|

Annex 4 – |

Other resources and guidance documents that can be considered for InvestEU sustainability proofing | 108 |

|

Annex 5 – |

Glossary | 111 |

|

Annex 6 – |

Additional guidance for intermediated financing (Chapter 3) | 114 |

1. INTRODUCTION

The InvestEU Regulation (1) introduces sustainability of financing and investment operations as an important element in the decision-making process when approving the use of the EU guarantee. For the purpose of this document, sustainability (2) refers to the three dimensions set out in Article 8(5) of the InvestEU Regulation: climate, environmental and social.

To ensure that financing and investment operations receiving support from the InvestEU Fund are in line with or contribute to the EU’s broader sustainability commitments, the InvestEU Regulation requires an ex ante sustainability proofing to identify and address any significant impacts (negative and positive) that these operations might have on the three dimensions.

The purpose of this guidance is to help implementing partners, financial intermediaries, and project promoters/final recipients deal with the InvestEU Regulation’s sustainability proofing requirements. Although this guidance was specifically developed for the InvestEU Fund, it could be used in a wider context by any party (e.g. a project promoter, a financial institution or a public authority) that wishes to take into consideration sustainability aspects in their activity. This guidance was developed in cooperation with potential implementing partners.

The guidance adheres to the principles of proportionality, transparency, and avoidance of undue administrative burden. The proposed approaches for the climate, environment and social dimensions take into consideration the existing practices and specific needs in those areas.

It is structured as follows:

|

— |

Chapter 1 sets the general legal context and clarifies some of the concepts used throughout the guidance. |

|

— |

Chapter 2 presents the approach for the sustainability proofing of directly financed operations. This chapter provides: (i) detailed guidance on how to perform the analysis for each of the three sustainability dimensions; and (ii) recommendations on how to include the results of these analyses in the economic appraisal of the project. |

|

— |

Chapter 3 provides guidance on the aspects of sustainability proofing related to indirectly financed transactions. This guidance is based on different types of financing and applicable requirements take into consideration their specificities. |

|

— |

Chapter 4 describes the roles and responsibilities of different actors involved, as well as information on how the sustainability proofing could be aligned with the overall InvestEU processes. |

|

— |

Annexes – include checklists developed to help implementing partners and project promoters perform the sustainability proofing, as well as a summary of further available resources. |

1.1. Scope

The sustainability aspects should be verified for financing and investment operations under all windows of the InvestEU Fund. Nevertheless, some differentiations between operations and windows will be necessary to ensure proportionality and reduce undue administrative burden. Articles 8(5) and 8(6) of the InvestEU Regulation set out the relevant requirements for sustainability proofing.

Pursuant to Article 8(5) of the InvestEU Regulation, financing and investment operations (‘operations’) above a certain threshold (set later in this guidance in Chapter 1.3) and seeking InvestEU support must first be subject to InvestEU screening (3). This screening is intended to help the implementing partners to determine whether operations have environmental, climate or social impacts (negative and positive).

If following the InvestEU screening, the implementing partner concludes that an operation has a significant impact on any of the three dimensions, then the operation must undergo sustainability proofing. The scope of the proofing will depend on the outcome of the InvestEU screening, and it might cover one or more dimensions. The proofing will aim to minimise the operation’s detrimental impacts and maximise its benefits to any of the three dimensions.

For the purpose of this guidance, a project means an investment in physical assets and/or in activities with clearly delineated scope and objectives, such as: (i) infrastructure; (ii) acquisition of equipment, machinery or other capital expenditures; (iii) technology development; (iv) specific research, digital and/or innovation activity; (v) energy efficiency refurbishments. The subject of the screening and proofing must be the project and its impacts thereof.

For general purpose financing (e.g. corporate finance for general purposes) or direct equity investments, the scope of the assessment will be: (i) the general approach of the final recipient to integrating sustainability considerations in their processes; and (ii) the final recipient’s capacity to address the related aspects and impacts deriving from their activities.

1.2. Legal compliance

Financing and investment operations supported by the InvestEU Fund, irrespective of their size and whether proofing is performed or not, must comply with the relevant EU and national legislation. This includes complying with the applicable environmental, social and labour law obligations established by Union law, national law, collective agreements or the international social and environmental conventions listed in Annex X to Directive 2014/24/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council (4).

The implementing partner (or the financial intermediary for indirect finance) should identify the relevant legal requirements (5) applicable to the operation and should verify (6) the compliance with the environmental and social legislation and regulations.

The sustainability proofing performed for the purposes of the InvestEU Regulation will not replace the compliance check with legal requirements under EU legislation and national law. The assessments carried out under EU and national legislation will provide the necessary input data (i.e. estimates of baseline emissions, descriptions of the likely significant effects of the project, positive effects, etc.) that will be used for the proofing, where applicable. The sustainability proofing will identify whether there are any residual impacts. It will also quantify and, where possible, monetise the residual impact that has been assessed to be of a high and/or medium risk. Subsequently, the proofing will address any residual impacts in the project’s economic appraisal, together with expected benefits stemming from the positive impacts of the project. This is the real added value of the sustainability proofing beyond compliance with legal requirements.

The co-legislators have explicitly required that implementing partners undertake sustainability proofing of investments under the InvestEU Fund. This implies ‘raising the bar’ and going beyond a requirement to merely comply with existing legislation. The co-legislators provide guidance on this issue in the InvestEU Regulation. For instance, some recitals refer to the European Pillar of Social Rights (7), the Paris Agreement (8), the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (9) and the 2018 Global Risks Report (10). Article 8(5) states that projects inconsistent with the climate objectives are not eligible for support under the InvestEU Fund. Moreover, Article 8(6) of the InvestEU Regulation refers to the climate vulnerability and risk assessment to address adaptation and climate resilience, cost of greenhouse gas (‘GHG’) emissions, accounting of impacts on the principal components of the natural capital, social impact of the projects, and identification of projects inconsistent with climate objectives.

1.3. Thresholds

In line with the principle of proportionality, and as required by Article 8(5) of the InvestEU Regulation, operations below an established threshold are exempt from the requirement for screening and sustainability proofing. This threshold applies specifically to InvestEU sustainability proofing, and it does not supersede in any way the legal obligations on project developers from the Environmental Impact Assessment Directive 2011/92/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council (11) (hereafter referred to as the ‘EIA Directive’) or other applicable EU or national law.

Based on current practice and experience gained in the area of environmental impact assessment and sustainability proofing of infrastructure projects, the thresholds below which sustainability proofing will not be required are as set out in the two points below:

|

(i) |

For direct operations:

|

|

(ii) |

For intermediated operations:

|

1.4. Sustainability proofing guidance and criteria of the EU Taxonomy (14)

The sustainability proofing requirement in the InvestEU Regulation aims to encourage and reward projects that have positive climate, environmental and social impacts, whilst reducing their negative impacts. Sustainability proofing makes possible to: (i) identify a project’s impacts; (ii) introduce mitigation measures to address these impacts; and (iii) where possible, recognise opportunities to improve the project’s sustainability performance.

The EU Taxonomy makes it possible to classify certain economic activities as environmentally sustainable (i.e. substantially contribute to at least one of the six environmental objectives (15) as defined in the Taxonomy Regulation, do no significant harm to any of the other five environmental objectives, and comply with the Minimum Social Safeguards). Sustainability proofing can take into account this classification, and then provide a more in-depth (granular) identification of positive and negative impacts. For this reason, the technical screening criteria of the EU Taxonomy will be used appropriately, including the principle of do no significant harm, after entering into force, where relevant and to the extent possible, throughout the screening and proofing process.

However, it should be noted that the InvestEU Fund covers a broader eligibility spectrum of investments than those economic activities covered by the EU Taxonomy. The InvestEU Fund also aims to take a balanced approach to different EU policy priorities, some of which might not have a strong sustainability potential, whereas the EU Taxonomy is a classification system set up to determine activities that substantially contribute to environmental objectives in the first instance.

Do No Significant Harm (‘DNSH’) criteria

To ensure that projects do not significantly harm EU environmental objectives, as for the EU Taxonomy, compliance with relevant EU environmental legislation is the starting point. Furthermore, compliance with relevant national environmental legislation and environmental permits needed for the construction and operation of projects is required, including those identified in the DNSH criteria of the EU Taxonomy. Taking into consideration the provisions of the InvestEU Regulation and of this guidance, the legal compliance is a prerequisite for any financing or investment operation qualifying to receive InvestEU support.

The other DNSH criteria that do not refer to environmental legislation should be used, when in force, as a reference for proposing mitigation measures or to identify projects inconsistent with the achievement of climate objectives – to the extent possible and on a best effort basis – for the cases where proofing is required in line with this guidance (for both direct and indirect financing, as further detailed in Chapter 2 and Chapter 3).

In practice, the following steps should be taken:

|

1. |

Based on InvestEU screening, the implementing partner determines whether proofing is needed for a certain criteria/dimension

|

|

2. |

Check if the activity is covered by the EU Taxonomy (16)

|

|

3. |

Check if there are DNSH criteria for the activity

|

|

4. |

Use the DNSH criteria, on a best effort basis, to propose additional mitigation measures, if needed. |

All InvestEU financing and investment operations (17), for both direct and indirect financing, should meet the following four conditions based on the DNSH criteria to climate change mitigation and the Minimum Social Safeguards (‘MSS’), with a clear view of not altering the overall eligibility criteria of InvestEU, as defined in the InvestEU Regulation and the Investment Guidelines. The four conditions are set out in the bullet points below:

|

— |

For projects covering the following activities: anaerobic digestion of bio-waste; landfill gas capture and utilisation – a monitoring plan should be put in place for methane leakage at the facility. |

|

— |

For projects covering transport of CO2 and underground permanent geological storage of CO2 – a detailed monitoring plan in line with the provisions of the CCS Directive 2009/31/EC (18) and EU ETS Directive (EU) 2018/410 (19). |

|

— |

For projects covering the following activities: freight rail transport; inland freight water transport; retrofitting of inland water passenger and freight transport; sea and coastal freight water transport; freight transport services by road – no InvestEU support should be granted for financing of vessels, vehicles or rolling stock specifically dedicated (20) to transport fossil fuels (such as rolling stock for mining of coal or oil tankers). |

|

— |

Comply with the MSS as laid out in Article 18 of the Taxonomy Regulation (21). Those minimum safeguards do not affect the application of more stringent requirements – where applicable – that are related to the occupational, health, safety and social sustainability set out in Union law. In particular, the implementing partners/financial intermediaries should ask for confirmation from the project promoter/final recipient concerning its operations that (22):

|

1.5. Mid-term evaluation and review of this guidance

Under Article 29 of the InvestEU Regulation the Commission must submit by 30 September 2024 to the European Parliament and to the Council an independent interim evaluation report on the InvestEU Programme. The evaluation must also cover the application of sustainability proofing. Based on the results of this evaluation and taking into consideration the developments on the financial market, the entry into force of the EU Taxonomy (25) and of the updated Non-financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) (26), the requirements described in this guidance might be modified in time (for both direct and indirect financing).

Therefore, it is highly recommended to both implementing partners and financial intermediaries to take these likely developments into consideration because they might affect future operations.

2. SUSTAINABILITY PROOFING FOR DIRECT FINANCING OPERATIONS

2.1. General principles and overall proofing approach

This chapter provides implementing partners with the methodologies and tools they need to perform the InvestEU screening and proofing of proposed direct financing and investment operations for the three sustainability dimensions, as required by Article 8(5) of the InvestEU Regulation (27). Article 8(6) gives further details regarding the objective of the guidance, which must allow to:

|

(a) |

as regards adaptation, ensuring resilience to the potential adverse impacts of climate change through a climate vulnerability and risk assessment, including through relevant adaptation measures, and, as regards mitigation, integrating the cost of greenhouse gas emissions and the positive effects of climate mitigation measures in the cost-benefit analysis; |

|

(b) |

accounting for the consolidated impact of projects in terms of the principal components of the natural capital, namely air, water, land and biodiversity; |

|

(c) |

estimating the social impact of projects, including on gender equality, on the social inclusion of certain areas or populations and on the economic development of areas and sectors affected by structural challenges such as the need to decarbonise the economy; |

|

(d) |

identifying projects that are inconsistent with the achievement of climate objectives; |

|

(e) |

providing implementing partners with guidance for the purpose of the screening provided for under paragraph 5. |

Figure 1 visualises the proposed approach for InvestEU sustainability proofing of direct financing and investment operations. It covers the following steps:

|

— |

Assessment of compliance with EU and national legislation. This is a prerequisite for all operations to be financed. It will include the assessment of compliance with legal requirements under the three dimensions of the sustainability (climate, environmental, social) and can be performed throughout the proofing process in parallel with the due diligence process, if needed, and should be completed, as a general rule, before the request of the EU Guarantee. Where this is not possible, appropriate conditions should be put in the legal documentation to ensure that the project will be fully compliant with applicable legislation. |

|

— |

InvestEU screening to identify potential risks and impacts on the three dimensions of the proposed operations. |

|

— |

Further assessment and proofing for the relevant elements at risk under each dimension, based on identified potential risks and impacts, including the identification of mitigating measures and assessing consistency with climate objectives (28). |

|

— |

Conclusion of the sustainability proofing and reporting to the InvestEU Investment Committee, to support decision making on the request for the EU Guarantee. |

Figure 1

Overview of sustainability proofing approach

All operations supported by InvestEU, irrespective of their size must comply with applicable EU and national legislation. For this reason, an assessment and confirmation of legal compliance will be required for all operations.

As described in the previous chapter, thresholds apply based on the size of the total investment operation and, when below these thresholds, no further screening and proofing will be required. The exception to this rule is those projects that require an environmental impact assessment (‘EIA’) under the EIA Directive (Annex I projects or screened-in Annex II projects), where proofing for the environmental, social and climate dimensions will be required regardless of the total project cost, for the impacts identified in the EIA report (29) and building on it. Such an approach is consistent with the requirements of the Invest EU Regulation.

For projects below the threshold, implementing partners and project promoters are nevertheless strongly encouraged to assess on a case-by-case basis whether the specific investment operation: (i) presents significant potential risks under one or more sustainability dimensions; and (ii) would benefit from going through at least the screening phase described in the following sections.

To encourage the take-up of the positive agenda, the implementing partners, in cooperation with the project promoters/final recipients, are strongly recommended to consider the possibility of increasing the positive impacts of the projects they are financing, thus increasing their overall sustainability performance. Checklists have been developed to help identify opportunities to increase positive impacts (see Annex 3), to be used on a voluntary basis.

Finally, this guidance recommends performing the assessment for the three dimensions in an integrated manner paying close attention to linkages and synergies across dimensions (30).

Infrastructure projects require a relatively long period to get through all the legal procedures of permitting and authorisations. For projects where the outcome of the proofing has identified additional measures and where such projects have already received all relevant authorisations and permits, it is understood that only limited additional measures can be recommended and implemented in some cases (for example, measures that could have been implemented in earlier stages of the project development cycle cannot be implemented anymore). Therefore, the implementing partner and the project promoters will be in the situation of being able to propose only those additional measures that can be realistically accomplished for projects in such an advanced stage of development. Such situations should be specifically highlighted and properly explained in the documentation to be presented to the Investment Committee (especially if any additional measures were recommended and implemented).

To avoid confusion over the terminology used in the overall context of the InvestEU Programme (e.g. Investment Guidelines), we propose to use in this chapter the term project as defined in Chapter 1.1 when referring to the underlying operations that will be subject of InvestEU screening, and proofing (if case) (31).

2.2. Climate dimension

2.2.1. Introduction

This section covers the methodology to be followed when performing the sustainability proofing of the climate dimension in the context of InvestEU direct financing.

As required by Article 8(6) of the InvestEU Regulation, this methodology aims at providing implementing partners with the principles and tools to: (a) as regards adaptation, ensure resilience to the potential adverse impacts of climate change through a climate vulnerability and risk assessment and through the implementation of commensurate relevant adaptation measures; and (b) as regards mitigation, to assess consistency with EU climate ambitions and commitments, to integrate the cost of greenhouse gas emissions related to the proposed projects, as well as to reflect the positive effects of climate mitigation measures in the options analysis, economic appraisal and/or cost-benefit analysis.

The methodology presented in this guidance largely mirrors the methodology described in detail by the Commission notice on technical guidance on the climate proofing of infrastructure in the period 2021-2027 (‘Guidance on the climate proofing of infrastructure in the period 2021-2027’) (32). As a result, the methodology presented in this document draws on internationally recognised methodologies both for the vulnerability and climate risk assessments, and for the assessment and mitigation of GHG emissions.

This methodology aims at identifying: (i) the nature and extent to which climate change and its impacts may harm a given project in order to decide on commensurate adaptation measures; and (ii) how a project can contribute to overall targets for GHG reduction, including when the project is part of a coherent planning framework (e.g. part of an integrated urban development plan) and related investment programme. While the methodology was developed for infrastructure projects, recommended approaches and tools could be used beyond what might be considered strictly infrastructure to identify the climate-change risks a project is exposed to, or to assess the GHG emissions related to the project with respect to the EU climate objectives.

As described in the ‘Guidance on the climate proofing of infrastructure in the period 2021-2027’, for climate change adaptation, the use of other recent and internationally recognised approaches and/or methodological frameworks (e.g. IPCC 5th Assessment Report, AR5) (33) to carry out climate risk assessments of projects remains possible in addition to the ones the guidance draws on, as they are expected to allow the user to arrive at equivalent conclusions.

For climate change mitigation, the main reference for assessing GHG emissions is the EIB Carbon Footprint Methodology (34), as recommended in the ‘Guidance on the climate proofing of infrastructure in the period 2021-2027’. Alternatively, internationally agreed and published carbon footprint methodologies may be used. The internal methodologies of implementing partners may also be applied, provided that they are consistent with the International Financial Institution Framework for a Harmonised Approach to Greenhouse Gas Accounting (35).

Whichever methodology is applied should be openly stated. In all cases, absolute (gross) and relative (net) emissions associated with projects should be reported. The scope of reporting for a project (i.e. whether it is for the whole of the project or only a part), and the choice of baseline scenario for calculating relative GHG emissions should be made transparent.

The Paris Agreement (36) sets the internationally agreed goal for limiting the global average increase in temperature and the global goal for climate-resilient development or adaptation. The approach presented throughout this entire chapter aims at supporting the development of investment operations aligned with the goals of the Paris Agreement and the EU Climate Law, once adopted.

2.2.2. General approach to climate sustainability proofing

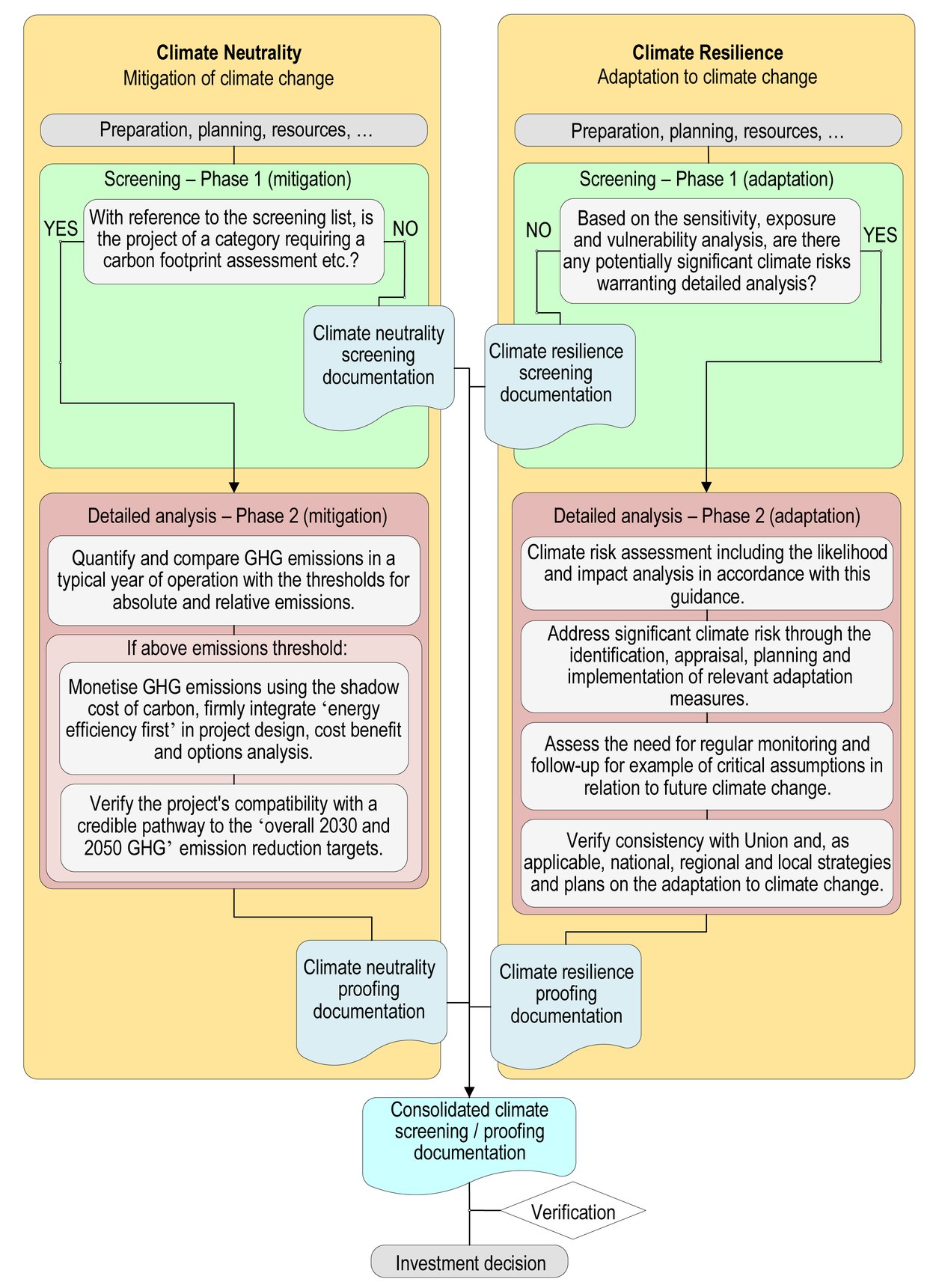

Climate proofing is a convenient shorthand for a process that integrates considerations of climate change adaptation and climate change mitigation into the development of existing assets and/or planned investment operations. Figure 2 illustrates the main steps of climate proofing.

Figure 2

Overview of the climate proofing process

|

Source: |

Guidance on the climate proofing of infrastructure in the period 2021-2027. |

The diagram reflects the two pillars of climate proofing. The pillar to the right focuses on climate resilience and adaptation to climate change. The pillar to the left focuses on climate neutrality and mitigation of climate change.

Each pillar of analysis is divided into two phases. The first phase covers a screening step meant to identify on one side, the significance of potential climate risks for the investment under consideration (for adaptation) and, on the other side, to assess consistency with EU climate commitments and to quantify respective GHG emissions (for mitigation). The outcome of the screening phase will determine whether a second phase of further detailed assessment is needed.

For InvestEU, the focus of climate proofing for direct financing is on individual projects that are in different stages of development and that involve different types of stakeholders (public or private). Having said that, integrating climate considerations in the preparation of an investment is a continuous process that needs to be considered, whenever possible, from the beginning and then in all the phases of the project cycle (37) and the related processes and analyses.

The ‘Guidance on the climate proofing of infrastructure in the period 2021-2027’ provides more information on the process of climate proofing over the various steps of the project cycle (38).

2.2.3. Legal compliance

In line with Recitals 8, 9 and 10 of the InvestEU Regulation, projects financed by the InvestEU Fund should contribute to achieving EU climate ambitions and commitments, including the objective of EU climate neutrality by 2050 and the Union’s new 2030 climate targets. In addition, Article 8(5) states that projects that are inconsistent with the climate objectives shall not be eligible for support under the InvestEU Regulation.

Climate change considerations are also an important component in the environmental impact assessment (‘EIA’) of a project (see following Chapter 2.3 on environmental proofing). This applies to both pillars of climate proofing, i.e. climate change mitigation and adaptation.

For the subset of investment operations requiring an EIA (Annex I or Annex II screened-in), undertaken in line with the requirements of the EIA Directive as amended, the outcome of the climate proofing will also be reflected in the EIA report. The EIA and other environmental assessments should ordinarily be planned and integrated into the project life cycle with due consideration of the climate proofing process.

Following the check against legal compliance requirements, and depending on the total project cost of the investment, the project moves on to the screening step.

For operations below the threshold of EUR 10 million that do not require an EIA (Annex II screened out or not falling under the scope of the EIA Directive) no climate proofing is required. However, to promote a positive approach to addressing climate change considerations, and to raise awareness about the climate risks (and related impacts) of the proposed investment, project promoters and implementing partners are strongly encouraged to:

|

— |

Consider performing the climate resilience screening step described in the following sections to identify potential climate-related risks to the proposed project (and related assets). Where relevant, they should also plan appropriate adaptation measures to be included in the project. |

|

— |

As regards to carbon footprint assessment, implementing partners and project promoters could also perform the assessment for investment projects below the EUR 10 million threshold, particularly when: (a) there are doubts that the proposed investment could lead to emission increases/reductions above the thresholds described in Section 2.2.5.1 below; and (b) when the proposed project is part of a wider investment programme for which an overall assessment in term of GHG emissions has been performed (39). |

For operations above the threshold of EUR 10 million, regardless of whether they require an EIA or not, the assessment must proceed with the InvestEU screening and proofing process, if applicable, in line with the guidelines for climate resilience and climate neutrality, as described in the following sections.

2.2.4. Climate resilience

2.2.4.1.

As recommended by the ‘Guidance on the climate proofing of infrastructure in the period 2021-2027’, the screening step for climate resilience is the first step of the proofing process and it is aimed at identifying and assessing potential climate change related risks – current and future – to the projects proposed for receiving InvestEU support.

The screening assessment is broken down into three steps as follows:

The aim of the vulnerability assessment (40) is to identify the material climate hazards (41) for the given specific project type at the planned location.

The vulnerability of a project is determined by a combination of two aspects: (i) how sensitive the project’s components are to climate hazards in general (sensitivity); and (ii) the probability of these hazards occurring at the project location now and in the future (exposure). These two aspects can be assessed in detail separately (as described below) or together.

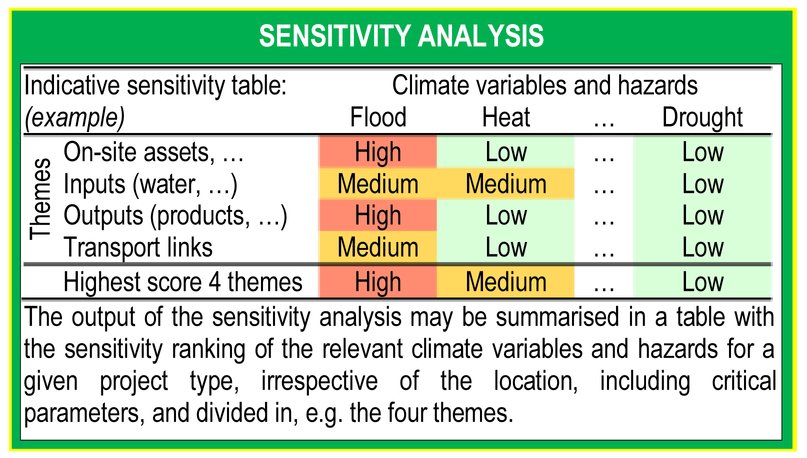

The aim of the sensitivity analysis is to identify which climate hazards are relevant to the specific type of investment, irrespective of its location. The sensitivity analysis should cover the project in a comprehensive manner, looking at the project’s various components and how the projects operate within the wider network or system.

A score of ‘high’, ‘medium’ or ‘low’ should be given for each theme and climate hazards:

|

— |

High sensitivity: the climate hazard may have a significant impact on assets and processes, inputs, outputs and transport links; |

|

— |

Medium sensitivity: the climate hazard may have a slight impact on assets and processes, inputs, outputs and transport links; |

|

— |

Low sensitivity: the climate hazard has no (or an insignificant) impact. |

Figure 3

Analysis of sensitivity to climate hazards

|

Source: |

Guidance on the climate proofing of infrastructure in the period 2021-2027. |

The aim of the exposure analysis is to identify which hazards are relevant to the planned project location, irrespective of the project type. The exposure analysis can be split in two parts: (i) exposure to the current climate; and (ii) exposure to the expected future climate. Available historic and current data for the relevant location should be used to assess current and past climate exposure. Climate model projections (42) can be used to understand how the level of exposure may change in the future. Particular attention should be given to changes in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events.

A score (i.e. ‘high’, ‘medium’ or ‘low’) should be given for each climate hazard on current and future exposures.

Figure 4

Exposure analysis

|

Source: |

Guidance on the climate proofing of infrastructure in the period 2021-2027. |

The vulnerability analysis combines the outcomes of sensitivity and exposure analyses, respectively, to identify the most relevant hazards for the proposed investment (these can be considered as those vulnerabilities with a ‘Medium’ or ‘High’ ranking).

Figure 5

Vulnerability analysis

|

Source: |

Guidance on the climate proofing of infrastructure in the period 2021-2027. |

If the scores for sensitivity and exposure both rank ‘low’, or when the combined vulnerability assessment concludes – with a reasoned justification – that all vulnerabilities are deemed low or insignificant, no further (climate) risk assessment may be needed. In such cases, the InvestEU proofing process could then end here, and the results of the analysis performed must be reported with the necessary details and justifications.

If the scores for sensitivity and/or exposure (or the overall vulnerability when jointly assessed) rank ‘medium’ and/or ‘high’, then the project needs to undergo a climate risk assessment according to the methodology described in the following section.

In any case, the ultimate decision to proceed to a detailed risk assessment based on identified vulnerabilities needs to be based on a justified implementing partner’s assessment (to be done with the support of the project promoter and/or the team performing the climate assessment) of the specific situation of the proposed investment (43) (44).

For more detailed methodological guidance on the screening phase, implementing partners and project promoters shall refer to the ‘Guidance on the climate proofing of infrastructure in the period 2021-2027’.

2.2.4.2.

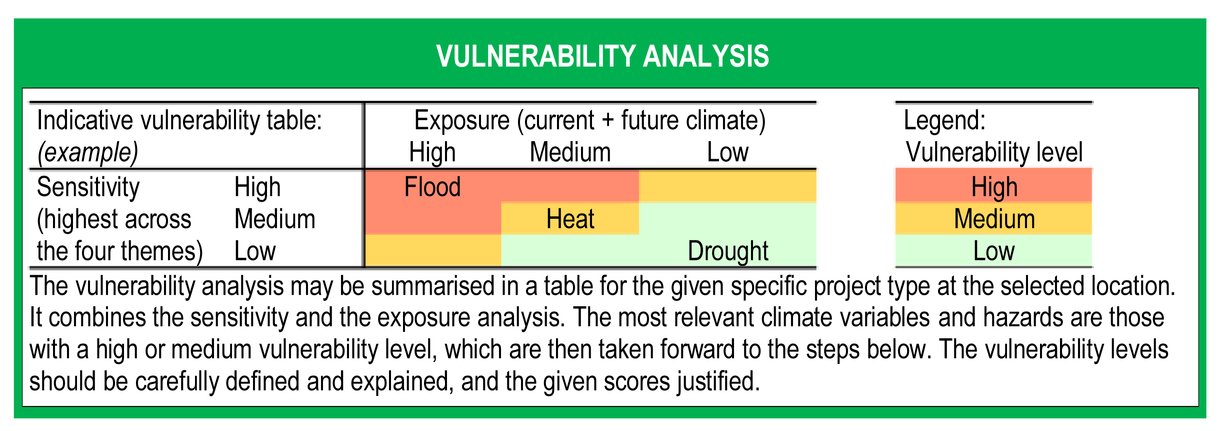

For projects whose vulnerability assessment has identified a ‘medium’ or ‘high’ potential climate risk, a detailed climate risk assessment should be carried out.

The climate risk assessment provides a structured method of analysing relevant climate hazards and their related impacts to provide information for decision-making in relation to the proposed investment. Any potential significant risks to the project due to climate change should be managed and reduced to an acceptable level by relevant and commensurate adaptation measures to be embedded in the project.

This process works by:

|

— |

assessing the likelihood and severity of the impacts associated with the hazards identified in the vulnerability assessment performed at the screening phase; |

|

— |

assessing the significance of the identified potential risks for the specific investment operation; |

|

— |

identifying adaptation measures to address potential significant climate risks. |

The likelihood or probability looks at how likely the identified climate hazards are to occur within a given timescale, e.g. the lifetime of the project. It may be summarised in a qualitative or quantitative estimate for each of the relevant climate hazards. It is noted that the likelihood may significantly change during the lifespan of the project.

The impact (also referred to as the severity or magnitude) looks at what would happen if the identified climate hazard did occur, and what the consequences would be for the investment. This should be assessed on a scale of impact per hazard. Among other things, this assessment will typically consider: (i) the physical assets and operations; (ii) health and safety; (iii) environmental impacts; (iv) social impacts; (v) financial implications; and (vi) reputational risk. The assessment needs to cover the adaptive capacity of the project and the system in which it operates, e.g. how well the project can cope with the impact and how much risk it can tolerate. It also needs to consider how fundamental this investment project is to the wider network or system (i.e. criticality) and whether it may lead to additional wider impacts and cascading effects.

The significance level of each potential risk can be determined by combining the two factors of likelihood and impact. The risks can be plotted on a risk matrix to identify the most significant potential risks and those where future action is needed through adaptation measures.

Figure 6

Overview of the risk assessment

|

Source: |

Guidance on the climate proofing of infrastructure in the period 2021-2027. |

Judging what is an acceptable level of risk, or what is significant and what not, is the responsibility of the project promoter and the expert team that carries out the assessment, and is specific to the circumstances of the project. In any case, this assessment should always be described in a clear and logical manner, and coherently integrated into the overall risk assessment for the project. This information is also very important for the implementing partner because the materialisation of the risks will have a material impact on the proposed investment and could result in the default of the supported operation.

If the risk assessment concludes that there are potential significant risks to the project due to climate change, these risks must be managed and reduced to an acceptable level (45).

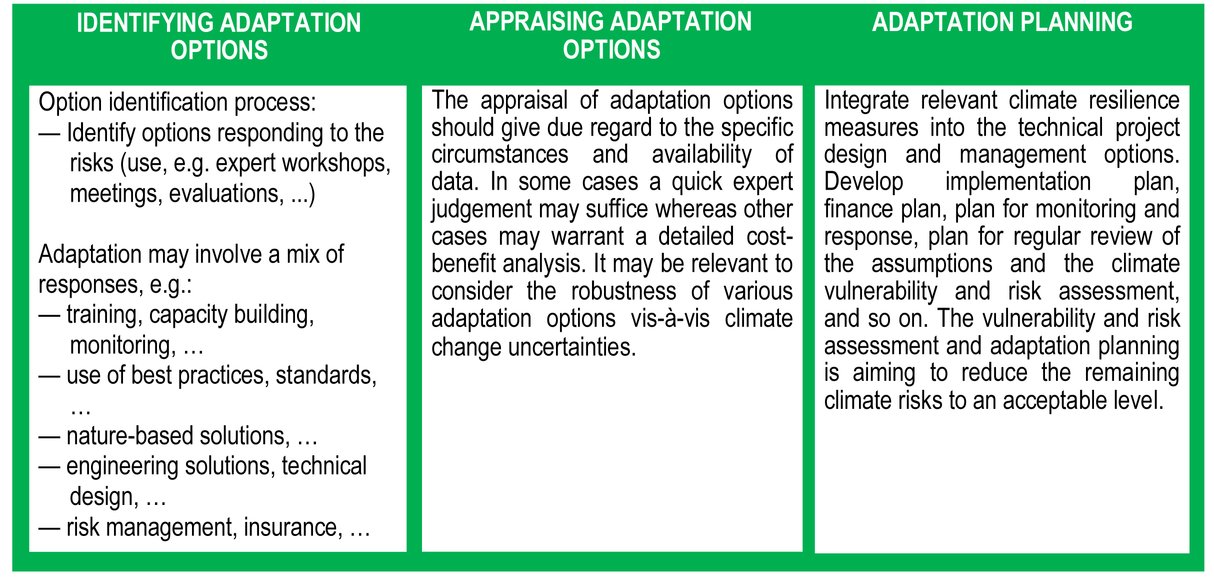

Figure 7

Overview of the identification, appraisal and planning/integration of relevant adaptation options

|

Source: |

Guidance on the climate proofing of infrastructure in the period 2021-2027. |

For each significant risk identified, relevant adaptation measures must be considered and assessed. Adaptation will often involve adopting a combination of structural measures (e.g. changes to the design or specification of physical assets and infrastructure, or the adoption of alternative or improved solutions) and non-structural measures (e.g. land-use planning, enhanced monitoring or emergency response programmes, staff training and knowledge sharing, development of strategic climate risk assessments, financial solutions such as insurance).

Different adaptation options should be assessed to find the right measure or mix of measures or even consider deferred implementation timings (flexible/adaptive measures), that can be implemented to reduce the risk to an acceptable level. The preferred measures should then be integrated into the project design and/or its operation to enhance its climate resilience (46).

Finally, as a good management practice, it is recommended to the project promoter to undertake ongoing monitoring throughout the operational lifetime of the investment in order to: (i) check the accuracy of the assessment and feed into future assessments and projects; and (ii) identify whether specific trigger points or thresholds are likely to be reached, indicating the need for additional adaptation measures.

2.2.5. Climate neutrality and mitigation (47) of climate change

2.2.5.1.

Mitigation of climate change means making efforts to reduce GHG emissions or increase sequestration of GHGs. These efforts are guided by EU emission reduction targets for 2030 and 2050. Meeting the EU targets, and globally the goals of the Paris Agreement, requires a fundamental shift in our economies from high-carbon activities to the deployment of low-carbon and net-zero solutions such as renewable energy and CO2 sequestration, in combination with significant advances in energy and resource efficiency. The principle of ‘energy efficiency first’ emphasises the need to prioritise alternative cost-efficient energy efficiency measures when making investment decisions, in particular cost-effective end-use energy savings, etc. (48). The quantification and monetisation of GHG emissions can support investment decisions based on that principle.

To verify and assess the compatibility of proposed projects with EU climate neutrality objectives, implementing partners and project promoters may use, to the extent possible, the ‘do no significant harm’ criteria to climate mitigation of the EU Taxonomy Regulation. Alternatively, the implementing partners and project promoters could make reference to the Paris alignment low-carbon criteria of the EIB, as published in the EIB Climate Bank Roadmap, or they could apply another internationally recognised and published methodology for assessment of Paris alignment with the low-carbon goals.

In addition, many projects supported by InvestEU in the period 2021-2027 will involve assets with a lifespan that extends beyond 2050. Therefore, expert analysis is needed to verify whether the project is compatible with, for instance, operation, maintenance and final decommissioning in the overall context of net-zero GHG emissions and climate neutrality. The early and consistent attention to the emission of greenhouse gases in the various development stages of the projects will help with the mitigation of climate change. A range of choices – in particular during the planning and design stages – may affect the project’s total GHG emissions over its lifespan from construction and operation until decommissioning.

In this context, the screening of an InvestEU operation with regard to GHG emissions aims to identify if a proposed project must undergo a carbon footprint assessment. This is relevant for determining the need for a deeper assessment in this respect and for the inclusion of monetary values of such externalities in the economic appraisal of the investment.

While CO2 emissions should be estimated for all projects, Table 1 below provides an indication of those project categories where it is expected that the emissions would most likely be significant, or not, as the basis for performing the InvestEU screening.

In line with the ‘Guidance on the climate proofing of infrastructure in the period 2021-2027’, InvestEU projects will have to perform a carbon footprint assessment if are likely to entail:

|

— |

Absolute emissions greater than 20 000 tonnes CO2e/year (positive or negative) |

|

— |

Relative emissions greater than 20 000 tonnes CO2e/year (positive or negative) |

In this respect, the project categorisation presented in Table 1 is for guidance only.

Implementing partners and project promoters may use a quantitative assessment, expert knowledge based on previous projects or other published sources to determine whether a project is likely to be above or below the thresholds presented above. Where there is uncertainty, then a carbon footprint calculation should be undertaken to assess whether the project is likely to be above or below the thresholds.

Table 1

Screening list for carbon footprint – indicative examples of project categories

|

Screening: |

Categories of projects |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In general, depending on the scale of the project, a carbon footprint assessment WILL NOT be required for these categories, unless it is expected that the project will be leading to significant emissions of CO2 or other greenhouse gases. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In general, carbon footprint assessment WILL be required |

|

|

Source: |

Guidance on the climate proofing of infrastructure in the period 2021-2027. |

Projects with expected emission levels above the thresholds must be further assessed in the following phase of the climate mitigation proofing (52).

2.2.5.2.

As described above, mitigation of climate change is about reducing GHG emissions and limiting global warming. Projects and other types of investments can contribute to this, for instance, through the design and selection of low-carbon alternatives.

In this guidance, carbon footprinting is used not only to estimate the GHG emissions of an investment when it is ready for implementation, but equally importantly to support the consideration and integration of low-carbon solutions during the planning and design stages, including at the stage of ranking and selection of alternative investment options, with a view to promoting low-carbon considerations and solutions (53). It is therefore recommended that climate proofing is integrated from the outset in the preparation of the proposed investments, and that estimates of GHG emissions linked to the investment are duly considered also in the options analysis and in the Economic Appraisal or Cost-Benefit Analysis.

For projects where the InvestEU screening has identified the potential for significant absolute and/or relative emissions, implementing partners will be asked to confirm the compatibility of proposed projects with EU climate neutrality objectives and to perform (in cooperation with the project promoter) or request from the project promoter a quantification of the project’s GHG emissions, using an internationally accepted carbon footprint methodology (54).

These emissions should then be monetised and integrated in the economic appraisal and in the selection of low-carbon options, and reported to the Investment Committee as part of the sustainability proofing exercise.

The ‘Guidance on the climate proofing of infrastructure in the period 2021-2027’ uses the EIB Carbon Footprint Methodology (55) as main reference for carbon footprint calculation. This recommended methodology includes default approaches for calculating emissions for various sectors including:

|

— |

Wastewater and sludge treatment |

|

— |

Waste treatment management facilities |

|

— |

Municipal solid waste landfill |

|

— |

Road transport |

|

— |

Rail transport |

|

— |

Urban transport |

|

— |

Building refurbishment |

|

— |

Ports |

|

— |

Airports |

|

— |

Forestry |

As indicated above, alternative internationally agreed and documented carbon footprint methodologies can also be used, provided that minimum requirements are respected as highlighted in Chapter 2.2.1.

For a more detailed treatment of the carbon footprint methodology, implementing partners are encouraged to consult the ‘Guidance on the climate proofing of infrastructure in the period 2021-2027’.

Carbon footprinting involves many forms of uncertainty, including uncertainty about the identification of secondary effects, about the baseline scenarios and baseline emission estimates. Therefore, greenhouse gas estimates are by definition approximate. Uncertainties inherent in greenhouse gas estimates or calculations should be reduced as far as is practical, and estimation methods should avoid bias.

Where uncertainty exists, the data and assumptions used to quantify greenhouse gas emissions should be conservative. Conservative values and assumptions are those that are more likely to overestimate absolute emissions and ‘positive’ relative emissions (net increases), and underestimate ‘negative’ relative emissions (net reductions).

Once GHG emissions have been quantified, they should be monetised and included in the economic appraisal of the proposed investment operation. This monetisation should be carried out by using an established and internationally agreed ‘shadow cost of carbon’. The application of a shadow cost of carbon to the change in emissions resulting from a project has the effect of monetising its carbon intensity and rewarding projects that lead to emission reductions.

This guidance recommends the use of the shadow cost of carbon recently set out by the EIB as the best available evidence on the shadow cost of meeting the temperature goal of the Paris Agreement (i.e. the 1,5 C target) (56). This recommendation is in line with the ‘Guidance on the climate proofing of infrastructure in the period 2021-2027’, and it helps to ensure comparability of data between different projects presented for approval to the Investment Committee.

For the individual years in the period from 2020 to 2050, the shadow cost of carbon is indicated in Table 2.

Table 2

Shadow cost of carbon for GHG emissions and reductions in EUR/tCO2e, 2016-prices

|

Year |

EUR/tCO2e |

Year |

EUR/tCO2e |

Year |

EUR/tCO2e |

Year |

EUR/tCO2e |

|

2020 |

80 |

2030 |

250 |

2040 |

525 |

2050 |

800 |

|

2021 |

97 |

2031 |

278 |

2041 |

552 |

|

|

|

2022 |

114 |

2032 |

306 |

2042 |

579 |

|

|

|

2023 |

131 |

2033 |

334 |

2043 |

606 |

|

|

|

2024 |

148 |

2034 |

362 |

2044 |

633 |

|

|

|

2025 |

165 |

2035 |

390 |

2045 |

660 |

|

|

|

2026 |

182 |

2036 |

417 |

2046 |

688 |

|

|

|

2027 |

199 |

2037 |

444 |

2047 |

716 |

|

|

|

2028 |

216 |

2038 |

471 |

2048 |

744 |

|

|

|

2029 |

233 |

2039 |

498 |

2049 |

772 |

|

|

|

Source: |

Guidance on the climate proofing of infrastructure in the period 2021-2027. |

The abovementioned abatement cost of carbon represents the minimum recommended value to be used to monetise GHG emissions. The use of higher values for the cost of carbon will be allowed (57), for instance when such values are used in a specific Member State or by the implementing partner concerned. Furthermore, the shadow cost of carbon may be adjusted when more information becomes available.

The monetary evaluation of the climate change impacts delivered by the project fits into the more comprehensive economic appraisal that is usually carried out by IPs. More information on how to include monetised GHG emissions in the Economic Appraisal expected for InvestEU investments is provided in Chapter 2.6.

2.2.6. Reporting and monitoring

The results of the climate resilience proofing should be reported by the implementing partner as part of the documentation to be presented to the Investment Committee on the outcome of the overall sustainability proofing as further developed in Chapter 4.2.2.

For climate adaptation, this should cover a summary of the outcome of the process performed, with clear conclusions on identified potential climate change risks to the investment, and should describe:

|

— |

The methodology used for the climate resilience proofing, concisely specifying the sources of data and information used in the assessment; |

|

— |

The steps followed and possible uncertainties in the underlying data and analysis; |

|

— |

The project development stage at which the vulnerability and risk assessment was undertaken; and |

|

— |

Related adaptation measures identified and included in the investment scope to reduce risks to acceptable levels, if applicable. |

The vulnerability and risk levels must be supported by detailed explanations to qualify and substantiate the assessment conclusions. The level of detail of the risk assessment will depend on the scale of the project (its type, size and relative importance) and the project development stage. For each significant risk identified, the documentation shall also present how the preferred adaptation measure(s) have been or will be integrated into the project design and/or its operations to enhance its resilience at the relevant development stages.

The documentation must also present the outcome of the proofing on climate mitigation aspects, if applicable, clarifying how it was performed. For those projects that underwent a full climate mitigation assessment, the IP shall also report on:

|

— |

Compatibility of proposed projects with EU reduction targets; |

|

— |

Methodology used to estimate and monetise GHG emissions, the scope of reporting (i.e. what project components are included/excluded from the calculation) and details of the baseline scenario used; |

|

— |

The quantification of the investment’s absolute (gross) and relative (net) GHG emissions |

|

— |

The carbon prices used to monetise the quantified GHG emissions, and how the monetisation of GHG emissions was included in the overall economic appraisal of the investment. |

During the operation phase of the investment, it is recommended to the project promoter to revisit the climate proofing and underlying assumptions and crosscheck with relevant observations, latest climate science, projections and data, and adjusted climate policy objectives, and report findings to the implementing partner.

2.3. Environment dimension

2.3.1. General approach to environmental proofing

Environmental proofing for InvestEU refers to a method for accounting for the consolidated impact of a project in terms of the principal components of natural capital, namely air, water, land (58) and biodiversity, as required by Article 8(6) of the InvestEU Regulation. This includes positive and negative impacts, whether they be direct or indirect.

Natural capital yields a flow of ecosystem services or benefits (59). These services can provide economic, social, environmental, cultural, or other welfare benefits. The value of these benefits can be understood in qualitative or quantitative (including in monetary) terms, depending on their context.

An explanation of key environmental terms considered for the purposes of proofing is provided below:

|

— |

Natural capital: It is another term for the stock of renewable and non-renewable resources (e.g. plants, animals, air, water, soils, and minerals). Projects can affect both the extent of these resources (e.g. by changing land use) and their quality (e.g. the condition of habitats). |

|

— |

Ecosystem services: Natural capital provides ecosystem services, such as food, timber, clean air, clean water, climate regulation and recreation. |

|

— |

Impacts: They are changes in the natural capital or in the ecosystem services it provides. Natural Capital accounting involves measuring these impacts to improve how they are taken into account in decision-making:

|

Table 3 provides examples of the links between natural capital and impacts.

Table 3

Linking impacts to relevant changes in the physical environment and damages or benefits

|

Natural capital |

Changes in natural capital or ecosystem services |

Examples of Impacts (positive and negative) |

||||||||||

|

Air |

||||||||||||

|

Air pollution |

Volume of pollutants emitted |

|

||||||||||

|

Water |

||||||||||||

|

Water pollution |

Volume of pollutants discharged |

|

||||||||||

|

Water consumption |

Volume of water abstracted |

|

||||||||||

|

Land |

||||||||||||

|

Waste generation |

Quantity of waste generated |

|

||||||||||

|

Change in land use |

Hectares of land use developed or intensified |

|

||||||||||

|

Biodiversity |

||||||||||||

|

Effects on species |

Proportion of species affected, level of threat and/or protection of species affected |

|

||||||||||

|

Effects on habitats and ecosystems |

Area of habitat or ecosystem lost or in reduced condition |

|

||||||||||

|

Source: |

Technical Support Document for Environmental Proofing of Investments under the InvestEU Programme. |

In line with Chapter 2.1, the approach to sustainability proofing for the environmental dimension is based on several steps. These steps include a decision point (based on the level of risk identified on one or more elements during the screening of a project) where it can be decided that no further proofing is required for impacts of potentially low risk (i.e. impacts unlikely to be significant) (61).

For projects requiring an EIA (Annex I or screened-in Annex II project), the implementing partner will:

|

— |

Review the identified impacts and risks and the proposed measures to avoid, prevent or reduce (mitigation measures) and, as a last resort, offset (compensation measures) likely significant negative impacts on the environment. The above should be available in the EIA report and other documentation such as permits, additional studies or reports from other assessments. |

|

— |

Review that an assessment has been carried out of the risks of any significant negative impacts remaining after mitigation (i.e. the residual impacts should have been assessed as part of the EIA report):

|

For projects screened out with mitigation measures, the implementing partner will:

|

— |

Review the identified impacts and risks and the mitigation measures proposed in the screening decision and supporting documentation, to avoid or prevent what might otherwise have been significant negative impacts on the environment:

|

For projects screened out without mitigation measures and for projects outside the scope of the EIA Directive, the implementing partner will:

|

— |

In cooperation with the project promoter, recognise whether there is a need for additional studies or reports and review the impacts and risks identified in those additional studies and reports, and consider possible mitigation measures to avoid or prevent what might otherwise have been significant negative impacts on the environment. |

|

— |

Where proportionate (possible and reasonable), quantify and monetise the identified impacts. |

For all projects:

|

— |

The implementing partner is strongly recommended to use the positive checklist to identify possibilities to improve the performance of the project. |

|

— |

The implementing partner must report to the InvestEU Investment Committee and monitor the project. |

It is necessary to ensure consistency in what is required across the different natural capital components, while also taking into account the need for proofing to be proportionate (possible and reasonable). When reviewing projects for financing with support from the InvestEU Fund, the implementing partner will carry out these assessment steps on the basis of documentation provided by the project promoter (i.e. environmental reports, decisions, permits). This documentation may be complemented by questionnaires completed by the project promoter (e.g. based on the implementing partner’s own due diligence procedures) or other studies and reports, as considered necessary.

Finally, legal compliance is a requirement for all projects.

Figure 8

Outline of Environmental Screening – Proofing

The following sections provide guidance on how implementing partners, with the support of the project promoter, could address each individual step of the assessment.

2.3.2. Legal compliance

All InvestEU supported operations, whether subject to sustainability proofing or not, must comply with applicable EU and national legislation. Legal compliance is a prerequisite for any support. Implementing partners must put in place or review their existing procedures to verify (62) such compliance.

To ensure that all implementing partners apply acceptable standards, this section:

|

— |

outlines general principles for the legal compliance checks; and |

|

— |

proposes specific checks for compliance with key EU environmental directives. |

The general principles are listed in the bullet points below:

|

— |

The required legal compliance will follow the progress of the due diligence process as normally applied by the implementing partner (63). |

|

— |

It is recommended that projects belonging to categories listed in Annex I of the EIA Directive and Annex II projects that require an EIA (i.e. projects with significant and/or likely significant impacts), both be considered for InvestEU financing when they are at a reasonably mature stage. This will enable the implementing partner to perform most of the compliance checks before funds are committed. In exceptional cases, flexibility on this recommendation could be possible and projects could be considered for financing at an earlier stage. In such exceptional cases, the finalisation of the procedures and fulfilment of the compliance requirements would then be a condition for the relevant disbursement (64). However, projects listed in Annex I of the EIA Directive can be presented to the Investment Committee only when they are at a reasonably mature stage, meaning the EIA report is finalised and the public consultation is completed. |

|

— |

In the exceptional cases of non-mature projects (e.g. projects without completed environmental assessments and/or permitting procedures) a project would have to be assessed on the basis of the available information. As a first step, this assessment could be limited to identifying the applicable key environmental directives, and securing a clear indication on when the legal compliance could be confirmed. For projects listed in Annex II of the EIA Directive, as a general rule, the screening decision by the competent authorities should be available at the moment the project is submitted for approval to the Investment Committee. However, in duly justified cases, the project may be more immature (e.g. low risks expected, as for example in the case of charging station projects). In such cases, the proofing can be performed by the implementing partner using only the checklists proposed in this guidance. For potentially problematic projects (e.g. because of their likely significant effects on Natura 2000 sites or public opposition), project specific environmental conditions should be proposed by the implementing partner and included in the financing contract. Irrespectively of the project specific conditions (if required), as already mentioned, the financing contract should always include, for such immature projects, a standard general condition regarding the submission of missing assessments and/or permits. These conditions must be met at the latest before the relevant disbursement and the legal compliance check should be completed at that stage and reported to the Investment Committee (65). If the assessment concludes that the project is too immature and carries too many risks, then the project should not receive support and the implementing partner should apply at a later stage for the EU Guarantee. |

|

— |

EU environmental directives as transposed into national legislation should be the main reference point for carrying out legal compliance checks. |

|

— |

The completed check for a project’s compliance with the applicable EU environmental legislation should result in a clear-cut answer on whether it is ‘compliant’ or ‘non-compliant’. This check should be supported with proof in the form of permits, approvals, licences or permissions provided by competent authorities with reference to either relevant directives or transposed national legislation. |

|

— |

If there are serious doubts on whether a project complies with EU and/or national legislation, implementing partners should consult Member States and/or the Commission (66). |

The following sub-sections discuss the key environmental directives for the legal compliance checks.

(a) The EIA Directive

The EIA Directive applies to a wide range of public and private projects, which are set out in Annexes I and II to this Directive:

|

— |

Mandatory EIA: All projects listed in Annex I are considered as having significant effects on the environment and therefore require an EIA. |

|

— |

EIA following determination by Member States (screening): For projects listed in Annex II, the national authorities must determine whether the project shall be made subject to an EIA. This decision is made through the ‘screening procedure’, which determines the effects of projects on the basis of thresholds/criteria or a case-by-case examination. The national authorities have to take into account the criteria laid down in Annex III of the EIA Directive. |

The EIA compliance check should confirm the project’s fulfilment of the key requirements of the EIA Directive. In this respect, it is important to note that a few projects might still have been authorised under the previous ‘non-revised’ EIA regime (Directive 2011/92/EU) and not under the ‘revised’ current EIA regime (Directive 2011/92/EU modified by Directive 2014/52/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council (67)). The EIA compliance check should be made against the applicable Directive in force at the time the EIA process was triggered (see in detail Article 3 of Directive 2014/52/EU).

Checklist 0 (see Annex 3) proposes a list of questions to guide implementing partners in the verification of compliance with the EIA Directive.

(b) The Birds and Habitats Directives

The Natura 2 000 network was set up pursuant to the Habitats Directive (68). Under this Directive, Member States must designate Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) to ensure the favourable conservation status of: (i) habitat types listed in Annex I to the Directive throughout their range in the EU; and (ii) species listed in Annex II to the Directive throughout their range in the EU. Under the Birds Directive (69), the network must include Special Protection Areas (SPAs) designated for 194 particularly threatened species and all migratory bird species.

Any plan or project likely to have a significant effect on a Natura 2000 site, either individually or in combination with other plans or projects, must undergo an appropriate assessment by the Member State (pursuant to Article 6). This assessment must determine the project or plan’s implications for the site, in view of the site’s conservation objectives (70). The competent authorities can only agree to the plan or project after having ascertained that it will not adversely affect the integrity of the site concerned (Article 6(3) of the Habitats Directive (71)).

In exceptional circumstances, a project may still be allowed to go ahead, in spite of a negative assessment, if: (i) there are no alternative solutions; and (ii) the plan or project is considered to be justified by imperative reasons of overriding public interest, including those of a social or economic nature. In such cases, the Member State must take appropriate compensatory measures to ensure that the overall coherence of the Natura 2000 network is protected (Article 6(4) of the Habitats Directive). The Commission must be informed about these measures via a standard notification form ‘Information to the European Commission according to Article 6(4) of the Habitats Directive’ (72). In certain cases, when a priority habitat or species is significantly affected and the project is justified for socioeconomic reasons, an opinion of the Commission is required. Methodological guidance on the provisions of Articles 6(3) and 6(4) of the Habitats Directive 92/43/EEC (73) includes further information to supplement this section.

For implementing partners, when checking compliance with the Habitats and Birds Directives, three scenarios are possible:

|

— |

a project has been screened out by Member State authorities from requiring an appropriate assessment (i.e. the project is not likely to have significant negative effects on Natura 2000 site/s); or |

|

— |

a project has been subject to an appropriate assessment by the Member State authorities, which resulted in a positive conclusion being given by the authorities, that the project will not have significant effects on Natura 2000 site/s (under Article 6(3) of the Habitats Directive); or |

|

— |

a project has been subject to an appropriate assessment, which resulted in a negative conclusion from the Member State authorities (i.e. the project has significant negative effects on Natura 2000 sites under Article 6(4) of the Habitats Directive). |

Checklist 0 (see Annex 3) proposes a list of questions to guide the verification of compliance with the Habitats and the Birds Directives, depending on the scenario (as described above) applicable to an individual operation.

(c) The Water Framework Directive

The Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EC) ensures the full integration of the economic and ecological perspectives in the management of water quality and quantity. The Directive applies to fresh, coastal and transitional waters and ensures an integrated approach to water management that respects the integrity of whole ecosystems.

The Directive’s key objective is to achieve (by 2015 (74)), good status for the over 111 000 surface waters (e.g. rivers, lakes, coastal waters) and the over 13 000 groundwaters in EU territory. Achieving ‘good status’ means securing good ecological and chemical status for surface waters and good quantitative and chemical status for groundwaters (groundwaters are the main sources for abstraction of drinking water).

The Water Framework Directive also introduces a requirement that river management be based on river basins (i.e. the natural geographical and hydrological unit) and not on administrative or political boundaries. The River Basin Management Plan details how the objectives set for the river basin (ecological status, quantitative status, chemical status and protected area objectives) are to be reached within the timescale required.

For implementing partners, there are two scenarios possible when checking compliance with the Water Framework Directive:

|

— |

In the first scenario, the project involves a new modification to the physical characteristics of a surface water body or alterations to the level of groundwater bodies that will NOT cause deterioration in the status of a water body or cause failure to achieve good water status/potential. In this case, the implementing partner must review the justification provided by the project promoter to support this conclusion. |

|

— |

In the second scenario, the project involves a new modification to the physical characteristics of a surface water body or alterations to the level of groundwater bodies which deteriorate the status of a water body or cause failure to achieve good water status/potential. In such cases, the implementing partners should review whether each of the conditions under Article 4(7) have been fulfilled, i.e.:

|

Checklist 0 (see Annex 3) proposes questions to guide the verification of compliance with the Water Framework Directive.

(d) Other relevant Directives

Depending on the nature of operations falling under a specific line of support, implementing partners are expected to verify compliance with specific directives, on the basis of authorisations, permits, licences, etc. provided by the project promoters. These could include:

Directive 2001/42/EC (75) – the Strategic Environmental Assessment