EUR-Lex Access to European Union law

This document is an excerpt from the EUR-Lex website

Document 52012TA1112(01)

Annual Report of the Court of Auditors on the implementation of the budget concerning the financial year 2011, together with the institutions’ replies

Annual Report of the Court of Auditors on the implementation of the budget concerning the financial year 2011, together with the institutions’ replies

Annual Report of the Court of Auditors on the implementation of the budget concerning the financial year 2011, together with the institutions’ replies

OJ C 344, 12.11.2012, p. 1–242

(BG, ES, CS, DA, DE, ET, EL, EN, FR, IT, LV, LT, HU, MT, NL, PL, PT, RO, SK, SL, FI, SV)

|

12.11.2012 |

EN |

Official Journal of the European Union |

C 344/1 |

In accordance with the provisions of Article 287(1) and (4) of the TFEU and Articles 129 and 143 of Council Regulation (EC, Euratom) No 1605/2002 of 25 June 2002 on the Financial Regulation applicable to the general budget of the European Communities, as last amended by Regulation (EU, Euratom) No 1081/2010 of the European Parliament and of the Council, and Articles 139 and 156 of Council Regulation (EC) No 215/2008 of 18 February 2008 on the Financial Regulation applicable to the 10th European Development Fund

the Court of Auditors of the European Union, at its meeting of 6 September 2012, adopted its

ANNUAL REPORTS

concerning the financial year 2011.

The reports, together with the institutions' replies to the Court's observations, were transmitted to the authorities responsible for giving discharge and to the other institutions.

The Members of the Court of Auditors are:

Vítor Manuel da SILVA CALDEIRA (President), David BOSTOCK, Ioannis SARMAS, Igors LUDBORŽS, Jan KINŠT, Kersti KALJULAID, Karel PINXTEN, Ovidiu ISPIR, Nadejda SANDOLOVA, Michel CRETIN, Harald NOACK, Henri GRETHEN, Szabolcs FAZAKAS, Louis GALEA, Ladislav BALKO, Augustyn KUBIK, Milan Martin CVIKL, Rasa BUDBERGYTĖ, Lazaros S. LAZAROU, Gijs DE VRIES, Harald WÖGERBAUER, Hans Gustaf WESSBERG, Henrik OTBO, Pietro RUSSO, Ville ITÄLÄ, Kevin CARDIFF, Baudilio TOMÉ MUGURUZA.

ANNUAL REPORT ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE BUDGET

2012/C 344/01

TABLE OF CONTENTS

General introduction

|

Chapter 1— |

The Statement of Assurance and supporting information |

|

Chapter 2— |

Revenue |

|

Chapter 3— |

Agriculture: market and direct support |

|

Chapter 4— |

Rural development, environment, fisheries and health |

|

Chapter 5— |

Regional policy; energy and transport |

|

Chapter 6— |

Employment and social affairs |

|

Chapter 7— |

External relations, aid and enlargement |

|

Chapter 8— |

Research and other internal policies |

|

Chapter 9— |

Administrative and other expenditure |

|

Chapter 10— |

Getting results from the EU budget |

GENERAL INTRODUCTION

|

0.1. |

The European Court of Auditors is the institution established by the Treaty to carry out the audit of European Union (EU) finances. As the EU’s external auditor it acts as the independent guardian of the financial interests of the citizens of the Union and contributes to improving EU financial management. More information on the Court can be found in its annual activity report which, together with its special reports on EU spending programmes and revenue and its opinions on new or amended legislation, are available on its website: www.eca.europa.eu. |

|

0.2. |

This is the Court’s 35th Annual Report on the implementation of the EU budget and covers the 2011 financial year. A separate Annual Report covers the European Development Funds. |

|

0.3. |

The general budget of the EU is decided annually by the Council and the European Parliament. The Court’s annual report, together with its special reports, provides a basis for the discharge procedure, in which the European Parliament decides whether the Commission has satisfactorily carried out its responsibilities for implementing the budget. The Court forwards its annual report to national parliaments at the same time as to the European Parliament and the Council. |

|

0.4. |

The central part of the annual report is the Court’s statement of assurance (the ‘DAS’) on the reliability of the annual accounts of the EU and on the legality and regularity of transactions (referred to in the report as ‘regularity of transactions’). The statement of assurance itself begins the report; the material which follows reports mainly on the audit work underlying the statement of assurance. |

|

0.5. |

The report is organised as follows:

|

|

0.6. |

The structure of the specific assessments has been altered. In this year’s Annual Report the single Chapter on agriculture and natural resources as presented in recent annual reports is replaced by two specific assessments and chapters:

|

|

0.7. |

In addition, the single Chapter on cohesion, energy and transport is replaced by two specific assessments and chapters:

|

|

0.8. |

The specific assessments are mainly based on: the results of the Court’s testing of the regularity of transactions; on an assessment of the effectiveness of the principal supervisory and control systems governing the revenue or expenditure involved; and on a review of the reliability of Commission management representations. |

|

0.9. |

As in previous years, the Annual Report comments on the European Commission's ‘synthesis report’, in which the Commission accepts political responsibility for management of the EU budget: see paragraphs 1.24 to 1.30. The Commission has chosen to include in its synthesis report for 2011 critical comments about the possible impact on estimates of error of the Court's current audit methods and of their developments being planned for 2012 and subsequent years. |

|

0.10. |

The Court regards these comments as inaccurate and premature. Furthermore, the Court points out that such developments in its audit approach and methodology reflect evolutions in its audit environment, including the way expenditure is managed by the auditees. As it always does, the Court will adequately explain any developments in its methodology and their effects in a transparent manner at the appropriate time. |

|

0.11. |

The Commission’s replies to the Court’s observations — or those of other EU institutions and bodies, where appropriate — are presented within the document. The Court’s description of its findings and conclusions takes into account the relevant replies of the auditee. However it is the Court’s responsibility, as external auditor, to report its audit findings, to draw conclusions from those findings, and thus to provide an independent and impartial assessment of the reliability of the accounts as well as of the regularity of transactions. |

CHAPTER 1

The Statement of Assurance and supporting information

TABLE OF CONTENTS

The Court’s Statement of Assurance provided to the European Parliament and the Council — Independent auditor’s report

Introduction

Audit findings for the 2011 financial year

Reliability of accounts

Regularity of transactions

Summary of the DAS specific assessments

Comparison with previous year(s)’ results

Reliability of Commission management representations

Introduction

Annual activity reports and declarations by directors-general

Synthesis report of the Commission

Budgetary management

Budgetary appropriations for commitments and payments

Utilisation of payment appropriations at year end

Outstanding budgetary commitments (RAL)

|

THE COURT'S STATEMENT OF ASSURANCE PROVIDED TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE COUNCIL — INDEPENDENT AUDITOR’S REPORT |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Reliability of the accounts |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Legality and regularity of the transactions underlying the accounts |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Revenue |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Commitments |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Payments |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

6 September 2012 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Vítor Manuel da SILVA CALDEIRA President |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

INTRODUCTION |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

AUDIT FINDINGS FOR THE 2011 FINANCIAL YEAR |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Reliability of accounts |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Regularity of transactions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Summary of the DAS specific assessments |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Table 1.1 — Payments in 2011 by Annual Report chapters

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Table 1.2 — 2011 Summary of findings on regularity of transactions

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Comparison with previous years’ results |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

1.14. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In the policy groups regional policy, energy and transport; and employment and social affairs (as compared with the former policy group cohesion, energy and transport) the Court’s estimate of the most likely error rate decreased. |

The Commission notes that for the third consecutive year, the level of error remains well below those reported by the Court in the period 2006-2008. This positive development derives from the reinforced control provisions of the 2007-2013 programming period and its strict policy of interruptions/suspensions when deficiencies are identified, in line with its 2008 Action Plan. As shown in Table 1.3, the combined most likely error for regional policy, transport, energy and employment and social affairs also decreased considerably compared to 2010, from 7,7 % to 5,1 %. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In the other policy groups (external relations, aid and enlargement; and administrative and other expenditure) the Court’s estimate of the most likely error remained stable (see Table 1.3 ). |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Table 1.3 — Comparison of audit results for 2010 and 2011

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Reliability of Commission management representations |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Introduction |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Annual activity reports and declarations by directors-general (14) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Increased amount of payments under reservation |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Table 1.4 — Reservations issued by Commission's directorates-general for 2011

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Commission estimates of a ‘residual error rate’ |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Synthesis report of the Commission |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

1.28. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

BUDGETARY MANAGEMENT |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Budgetary appropriations for commitments and payments |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Utilisation of payment appropriations at year end |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

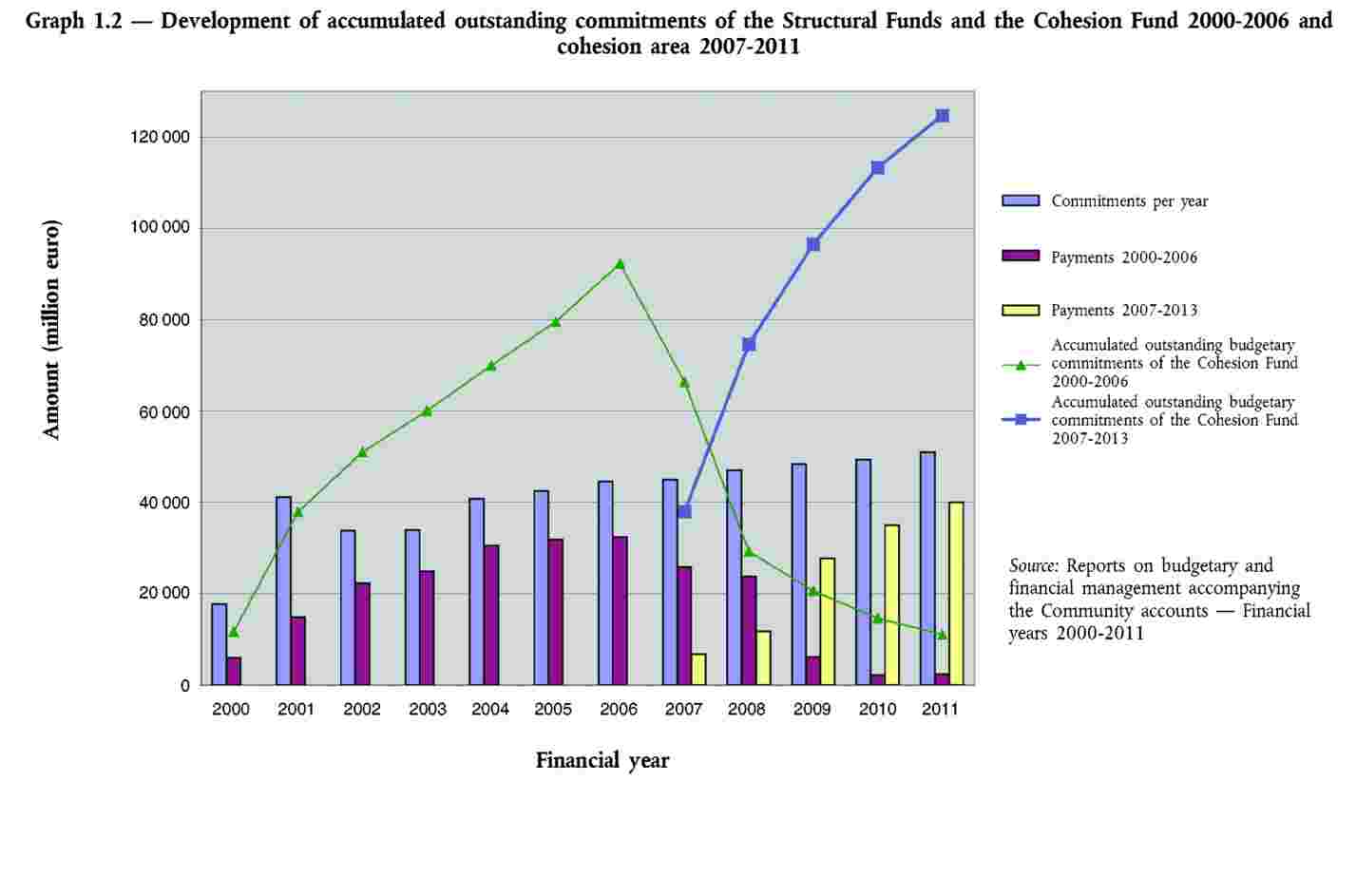

Outstanding budgetary commitments (RAL) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(1) The consolidated financial statements comprise the balance sheet, the economic outturn account, the cash flow table, the statement of changes in net assets and a summary of significant accounting policies and other explanatory notes (including segment reporting).

(2) The consolidated reports on implementation of the budget comprise the consolidated reports on implementation of the budget and a summary of budgetary principles and other explanatory notes.

(3) The accounting rules adopted by the Commission's accounting officer are derived from International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSAS) issued by the International Federation of Accountants or, in their absence, International Accounting Standards (IAS)/International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) issued by the International Accounting Standards Board. In accordance with the Financial Regulation, the consolidated financial statements for the 2011 financial year were prepared (as they have been since the 2005 financial year) on the basis of these accounting rules adopted by the Commission's accounting officer, which adapt accruals based accounting principles to the specific environment of the European Union, while the consolidated reports on implementation of the budget continue to be primarily based on cash movements.

(4) From French: ‘Déclaration d’assurance’.

(5) See article 287 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

(6) Council Regulation (EC, Euratom) No 1605/2002 of 25 June 2002 on the Financial Regulation applicable to the general budget of the European Communities (OJ L 248, 16.9.2002, p. 1), last amended by Regulation (EU, Euratom) No 1081/2010 of the European Parliament and of the Council (OJ L 311, 26.11.2010, p. 9), requires that the final consolidated accounts shall be sent before 31 July of the following financial year (see Article 129).

(7) For the scope of the audit of revenue, see paragraphs 2.9 and 2.13.

(8) Interim and final payments based on declarations of expenditure incurred at the level of final recipients (see paragraphs 3.9, 4.9, 5.27 and 6.12).

(9) In contrast to previous years, failure to meet cross-compliance obligations by recipients of payments under the CAP has been included in the calculation of the most likely error. The errors found represent around 0,1 percentage point of the most likely error estimated by the Court for payments as a whole (see paragraph 3.9, second indent, paragraph 3.13, paragraph 4.9, second indent, and paragraphs 4.16 to 4.18).

(10) White Paper ‘Reforming the Commission’, COM(2000) 200 final of 5.4.2000.

(11) European Parliament resolution of 19 January 2000 on action to be taken on the second report of the Committee of Independent Experts on reform of the Commission (OJ C 304, 24.10.2000, p. 135).

(12) The Commission’s internal control standards are largely inspired by the COSO principles. COSO is a voluntary private-sector organisation dedicated to improving the quality of financial management and reporting through business ethics, effective internal controls and corporate governance.

(13) The term ‘director-general’ is used in the broad sense of persons responsible. In fact, the 48 declarations have been signed by 1 secretary-general, 36 directors-general, 7 directors and 4 heads of service.

(14) Performance aspects of the annual activity reports are treated in Chapter 10.

(15) See paragraphs 3.40 to 3.41, 4.48 to 4.50, 5.67 to 5.69, 6.24 to 6.26 and 7.25.

(16) See paragraphs 1.32 to 1.50 of the Court’s 2009 Annual Report.

(17) Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council and the Court of Auditors — Synthesis of the Commission’s management achievements in 2011, COM(2012) 281 final of 6.6.2012.

(18) Information about the overall quality of financial management is absent in the external aid DGs, but no reservation has been provided for this (see paragraph 7.25 and paragraphs 52 to 53 in the 2011 EDF Annual Report).

(19) See Opinion No 6/2010 on a proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Financial Regulation applicable to the general budget of the European Union of the European Court of Auditors (OJ C 334, 10.12.2010, p. 1).

(20) Amounts available for commitments in this and future years.

(21) Includes appropriations for commitment carried over from 2010 amounting to 259 million euro and an overall 284 million euro increase in appropriations for commitment arising from the seven amending budgets approved during 2011. It excludes assigned revenue which in 2011 amounts to 6,2 billion euro for commitments and 6,7 billion euro for payments. Assigned revenues are used to finance specific items of expenditure (see Article 18 of the Financial Regulation — Regulation (EC, Euratom) No 1605/2002). They cover inter alia refunds arising from recovery of amounts paid in error, which are re-allocated to their budget line of origin, contributions from EFTA members increasing budget lines, and revenue from third parties where agreements have been concluded involving a financial contribution to EU activities.

(22) Amounts available for payments in the year.

(23) Includes appropriations for payment carried over from 2010 amounting to 1 582 million euro and an overall 200 million euro increase in appropriations for payment arising from the seven amending budgets approved during 2011.

(24) In 2011 appropriations for commitment were higher than in 2010 by 0,6 billion euro (0,4 %), and appropriations for payment were higher by 3,6 billion euro (2,9 %).

(25) The budgetary surplus (budget outturn) is the result of the implementation of the budget. However, it is not a reserve and it cannot be accumulated and used in future years to finance expenditure.

(26) In the case of the ESF an underutilisation in 2010 (see the Court’s 2010 Annual Report, paragraph 1.41) led to additional payments in 2011. This, together with accelerated payment requests towards the end of the year, increased the actual payments to 114 % of the original budget. The additional payment requests for the ESF were mainly covered by transfers from ERDF and CF. However, unforeseen inflow of payment requests for ERDF and CF towards the end of the year overturned predictions and increased actual payments to such a level that additional payments could have been made from these funds, if appropriations had been available — see also ‘Report on budgetary and financial management accompanying the Community accounts — Financial year 2011’, pp. 42-45.

(27) High percentages of payments in December compared to the actual payments made in the year: Title 06 — Mobility and transport 26 % (295 million), Title 17 — Health and consumer protection 44 % (266 million), Title 19 — External relations 31 % (1 016 million), Title 21 — Development and relations with African, Caribbean and Pacific States 27 % (403 million), Title 22 — Enlargement 28 % (264 million) and Title 32 — Energy 23 % (219 million).

(28) From French: ‘Reste à liquider’.

(29) Outstanding budgetary commitments arise as a direct consequence of differentiated appropriations (see footnote 30), where expenditure programmes take a number of years to be completed and commitments made in earlier years remain outstanding until the corresponding payments are made.

(30) The budget distinguishes between two types of appropriation: non-differentiated appropriations and differentiated appropriations. Non-differentiated appropriations are used to finance operations of an annual nature, e.g. administrative expenditure. Differentiated appropriations were introduced to manage multiannual operations; the related payments can be made during the year of the commitment and during the following years. Differentiated appropriations are used mainly for the Structural Funds and the Cohesion Fund.

(31) For cohesion, the following total commitments were foreseen in the Financial Framework 2000-2006: 261 billion euro (see 2006 accounts) and the Financial Framework 2007-2013: 348 billion euro (see 2011 accounts), i.e. an increase of 33 %.

(32) For cohesion see ‘Report on budgetary and financial management accompanying the Community accounts — Financial year 2011’, pp. 28, 42-45.

(33) The automatic decommitment rule (n + 2 rule/n + 3 rule) helps to clear outstanding commitments. This rule requires automatic decommitment of all funds not spent or not covered by a payment request by the end of the second/third year following the year of allocation. As part of the ‘third simplification’ package, the n + 2/n + 3 rule was last amended for the 2007 commitments in cohesion (see Council Regulation (EC) No 1083/2006 (OJ L 210, 31.7.2006, p. 26), amended by Regulation (EU) No 539/2010 of the European Parliament and of the Council (OJ L 158, 24.6.2010, p. 1).

(34) See the Court’s 2008 Annual Report, paragraphs 6.8 and 6.26 to 6.28. More details are available in the Commission Report on budgetary and financial management accompanying the Community accounts — Financial year 2008, p. 42, and in the Commission Analysis of the budgetary implementation of the Structural and Cohesion Funds in 2008, p. 5 and pp. 13-17.

(35) OJ C 139, 14.6.2006, p. 1. See also Article 3 of Council Decision 2007/436/EC, Euratom of 7 June 2007 on the system of the European Communities Own Resources (OJ L 163, 23.6.2007, p. 17).

(36) The budgetary Titles 14 and 24 to 31 of Section III of the general budget concerning primarily administrative expenditure are reported in the European Commission Section of Chapter 9.

(37) Administrative expenditure is deducted from policy groups and shown separately under its own heading; this leads to differences in comparison with Chapters 3 to 9.

(38) In the 2010 Annual Report, the policy groups agriculture: market and direct support and rural development, environment, fisheries and health as well as the policy groups regional policy, energy and transport and employment and social affairs were single policy groups. The aggregated results for 2011, based on the previous structure, are presented in Table 1.3 .

(39) Systems are classified as ‘partially effective’ where some control arrangements have been judged to work adequately whilst others have not. Consequently, taken as a whole, they might not succeed in restricting errors in the underlying transactions to an acceptable level. For details see the section ‘Audit scope and approach’ in Chapters 2 to 9.

(40) The frequency of errors represents the proportion of the sample affected by quantifiable and non-quantifiable errors. Percentages are rounded.

(41) Reimbursed expenditure (see paragraph 3.9).

(42) Reimbursed expenditure (see paragraph 4.9).

(43) Reimbursed expenditure (see paragraph 5.27).

(44) Reimbursed expenditure (see paragraph 6.12).

(45) The difference between the payments in 2011 (129 395 million euro — see Table 1.1 ) and the total amount of the overall audited population in the context of the regularity of transactions corresponds to advances paid for the policy groups agriculture: market and direct support (8 million euro), rural development, environment, fisheries and health (565 million euro), regional policy, energy and transport (1 469 million euro), and employment and social affairs (128 million euro) (see paragraphs 3.9, 4.9, 5.27 and 6.12).

(46) In contrast to previous years, failure to meet cross-compliance obligations has been included in the calculation of the most likely error. The errors found represent around 0,2 percentage points of the total most likely error (see paragraph 3.9, second indent and paragraph 3.13).

(47) In contrast to previous years, failure to meet cross-compliance obligations has been included in the calculation of the most likely error. The errors found represent around 0,2 percentage points of the total most likely error (see paragraph 4.9, second indent and paragraphs 4.16 to 4.18).

(48) In contrast to previous years, failure to meet cross-compliance obligations by recipients of payments under the CAP has been included in the calculation of the most likely error. The errors found represent around 0,1 percentage point of the most likely error estimated by the Court for payments as a whole (see also footnotes 9 and 10).

(49) The audit involved examination at the Commission's level of a sample of recovery orders covering all types of revenue (see paragraphs 2.8, 2.9 and 2.13).

(50) In contrast to previous years, failure to meet cross-compliance obligations has been included in the calculation of the most likely error (see paragraphs 3.9, 3.13, 4.9 and 4.16 to 4.18). The errors found represent around 0,2 percentage points of the total most likely error.

(51) In contrast to previous years, failure to meet cross-compliance obligations by recipients of payments under the CAP has been included in the calculation of the most likely error. The errors found represent around 0,1 percentage point of the most likely error estimated by the Court for payments as a whole (see also footnote 1).

(52) For the full list of Commission's DGs/services please see http://publications.europa.eu/code/en/en-390600.htm

(53) Source: 2011 consolidated accounts.

(54) Source: 2011 annual activity reports. REGIO and REA have indicated minimum and maximum amounts. Only the latter have been taken into account.

ANNEX 1.1

AUDIT APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY

PART 1 — Audit approach and methodology for the reliability of accounts (financial audit)

|

1. |

In order to assess whether the consolidated accounts, consisting of the consolidated financial statements and the consolidated reports on the implementation of the budget (1), present fairly, in all material respects, the financial position of the European Union, and the results of operations and cash flows at the year end, the main assessment criteria are: (a) legality and regularity: the accounts are drawn up in accordance with the rules, and budgetary appropriations are available; (b) completeness: all revenue and expenditure transactions and all assets and liabilities (including off-balance sheet items) proper to the period are entered in the accounts; (c) reality of the transactions and existence of the assets and liabilities: each revenue and expenditure transaction is justified by an event which pertains to the entity and is proper to the period; the asset or liability exists at the balance sheet date and is proper to the reporting entity; (d) measurement and valuation: the revenue and expenditure transaction and the asset or liability is entered in the accounts at an appropriate value, bearing in mind the principle of prudence; (e) presentation of information: the revenue and expenditure transaction, asset or liability is disclosed and described in accordance with the applicable accounting rules and conventions and the principle of transparency. |

|

2. |

The audit consists of the following basic elements:

|

PART 2 — Audit approach and methodology for the regularity of transactions (compliance audit)

|

3. |

The approach taken by the Court to audit the regularity of the transactions underlying the accounts comprises:

|

|

4. |

This is supplemented by evidence provided by the work of other auditors (where relevant) and an analysis of Commission management representations. |

How the Court tests transactions

|

5. |

The direct testing of transactions within each specific assessment (Chapters 2 to 9) is based on a representative sample of the recovery orders (in the case of revenue) and payments contained within the policy group concerned (2). This testing provides a statistical estimation of the extent to which the transactions in the population concerned are irregular. |

|

6. |

In order to determine the sample sizes necessary to produce a reliable result, the Court uses an audit assurance model. This involves an assessment of the risk of errors occurring in transactions (inherent risk) and the risk that the systems do not prevent or detect and correct such errors (control risk). |

|

7. |

Transaction testing involves a detailed check of each transaction selected by the samples, including determination of whether or not the claim or payment was correctly calculated and in compliance with the relevant rules and regulations. The Court samples the transactions recorded in the budgetary accounts and traces the payment down to the level of the final recipient (e.g. farmer, organiser of training course, or development aid project promoter) and tests compliance at each level. When the transaction (at any level) is incorrectly calculated or does not meet a regulatory requirement or contractual provision, it is considered to contain an error. |

How the Court evaluates and presents the results of transaction testing

|

8. |

Errors in transactions occur for a variety of reasons and take a number of different forms depending on the nature of the breach and specific rule or contractual requirement not followed. Errors in individual transactions do not always affect the total amount paid. |

|

9. |

The Court classifies errors as follows:

|

|

10. |

Public procurement is one area where the Court often finds significant errors. EU and national public procurement law consists essentially of a series of procedural requirements. To ensure the basic principle of competition foreseen in the Treaty the contracts have to be advertised; bids must be evaluated according to specified criteria; contracts may not be artificially split to get below thresholds, etc. |

|

11. |

For its audit purposes the Court puts a value on failure to observe a procedural requirement. The Court:

The quantification by the Court may differ from that used by the Commission or Member States when deciding how to respond to misapplication of the public procurement rules. |

|

12. |

The Court expresses the frequency by which errors occur by presenting the proportion of the sample affected by quantifiable and non-quantifiable errors. This indicates how widespread errors are likely to be within the policy group as a whole. This information is given in Annexes X.1 of Chapters 2 to 9 when material error is present. |

|

13. |

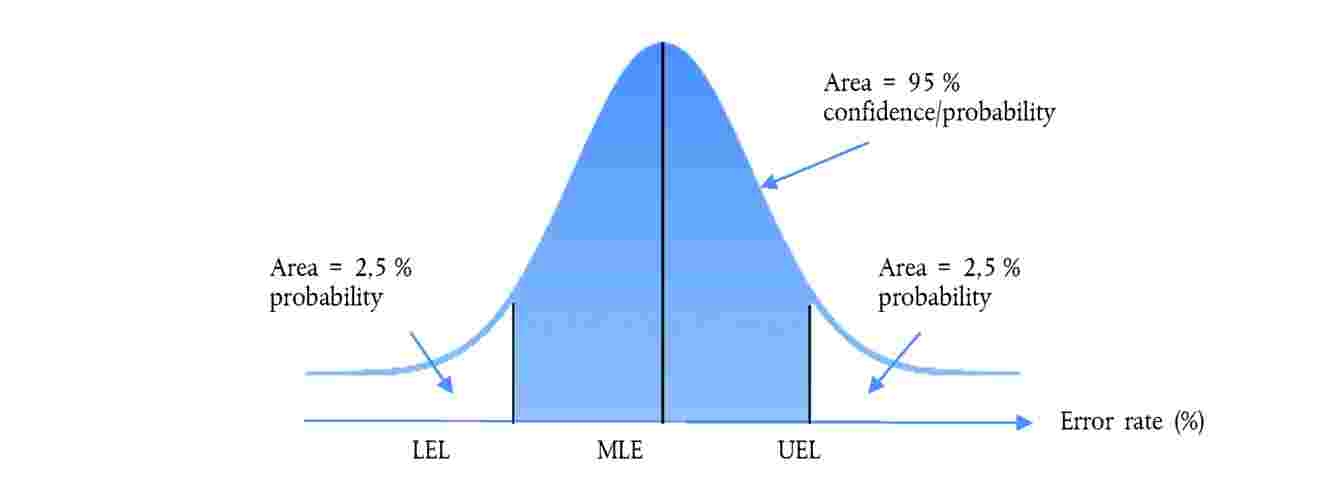

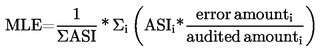

On the basis of the errors which it has quantified, the Court, using standard statistical techniques, estimates the most likely rate of error (MLE) in each specific assessment and for spending from the budget as whole. The MLE is the weighted average of the percentage error rates found in the sample (6). The Court also estimates, again using standard statistical techniques, the range within which it is 95 % confident that the rate of error for the population lies in each specific assessment (and for spending as whole). This is the range between the lower error limit (LEL) and the upper error limit (UEL) (7) (see illustration).

|

|

14. |

The percentage of the shaded area below the curve indicates the probability that the true error rate of the population is between the LEL and the UEL. |

|

15. |

In planning its audit work, the Court seeks to undertake procedures allowing it to compare the estimated rate of error in the population with a planning materiality of 2 %. In assessing audit results, the Court is guided by this level of materiality and takes account of the nature, amount and context of errors when forming its audit opinion. |

How the Court assesses systems and reports the results

|

16. |

Supervisory and control systems are established by the Commission and Member and beneficiary States in the case of shared or decentralised management, to manage the risks to the budget, including the regularity of transactions. Assessing the effectiveness of systems in ensuring regularity is therefore a key audit procedure, and particularly useful for identifying recommendations for improvement. |

|

17. |

Each policy group is subject to a multitude of individual systems, likewise revenue. The Court therefore normally selects a sample of systems to assess each year. The results of the systems assessments are presented in the form of a table called ‘Results of examination of systems’ given in Annexes X.2 of Chapters 2 to 9. Systems are classified as being effective in mitigating the risk of error in transactions, partially effective (when there are some weaknesses affecting operational effectiveness) or not effective (when weaknesses are pervasive and thereby completely undermine operating effectiveness). |

|

18. |

In addition and when supported by evidence, the Court provides an overall assessment of systems for the policy group (also provided in Annexes X.2 of Chapters 2 to 9), which takes into account both the assessment of selected systems, as well as the results of transaction testing. |

How the Court assesses Commission management representations and reports the results

|

19. |

As required by International Standards on Auditing, the Court obtains a letter of representation from the Commission, confirming that the Commission has fulfilled its responsibilities, and disclosed all information that could be relevant to the auditor. This includes confirmation that the Commission has disclosed all information in respect of the assessment of the risk of fraud, all information in respect of fraud or suspected fraud of which the Commission is aware, and all material instances of non-compliance with laws and regulation. |

|

20. |

In addition, Chapters 2 to 9 consider the annual activity reports of relevant directorates-general. These report on the achievement of policy objectives and the supervisory and control systems in place to ensure the regularity of transactions and sound use of resources. Each annual activity report is accompanied by a declaration of the director-general on inter alia the extent to which resources have been used for their intended purpose, and control procedures ensure the regularity of transactions (8). |

|

21. |

The Court assesses the annual activity reports and accompanying declarations in order to determine how far they provide a fair reflection of financial management in relation to regularity of transactions and identify the necessary measures to address any serious control deficiencies. The Court reports on the results of this assessment in the section ‘Effectiveness of systems’ in Chapters 2 to 9 (9). |

How the Court arrives at its opinions in the statement of assurance

|

22. |

The Court arrives at its opinion on the regularity of transactions underlying the European Union's accounts, set out in the statement of assurance, on the basis of all its audit work as reported in Chapters 2 to 9 of this report and including an assessment of the pervasiveness of error. A key element is the consideration of the results of testing of spending transactions. Taken together, the Court’s best estimate of the rate of error for overall spending in 2011 is 3,9 %. The Court has 95 % confidence that the rate of error for the population is between 3,0 % and 4,8 %. The error rate estimated for different policy areas varies as described in Chapters 3 to 9. The Court assessed error as pervasive — extending across the majority of spending areas. The Court gives an overall opinion on the regularity of commitments based on an additional horizontal sample. |

Irregularity or fraud

|

23. |

The overwhelming majority of errors arise from misapplication or misunderstanding of the often complex rules of EU expenditure schemes. If the Court has reason to suspect that fraudulent activity has taken place, it reports this to OLAF, the Union’s anti-fraud office, which is responsible for carrying out any resulting investigations. In fact, the Court reports around four cases per year to OLAF, based on its audit work. |

(1) Including the explanatory notes.

(2) Additionally to this, a horizontal representative sample of commitments is drawn and tested for compliance with the relevant rules and regulations.

(3) There are essentially two award systems: the lowest offer or the most advantageous offer.

(4) Examples of a quantifiable error: no or restricted competition (except where this is explicitly allowed by the legal framework) for the main or a supplementary contract; inappropriate assessment of bids with an impact on the outcome of the tender; substantial change of the contract scope; splitting of the contracts for different construction sites, which fulfil the same economical function.

The Court applies in general a different approach to misapplication of the public procurement rules by the EU institutions, on the grounds that the contracts concerned generally still remain valid. Such errors are not quantified in the DAS.

(5) Examples of a non-quantifiable error: inappropriate assessment of bids without impact on the outcome of the tender, formal weaknesses of tender procedure or tender specification, formal aspects of the transparency requirements not respected.

(6)  , where ASI is the average sampling interval and i is the numbering of transactions in the sample.

, where ASI is the average sampling interval and i is the numbering of transactions in the sample.

(7)  and

and  , where t is the t-distribution factor, n is the sample size and s is the standard deviation of the percentage errors.

, where t is the t-distribution factor, n is the sample size and s is the standard deviation of the percentage errors.

(8) Further information on these processes, as well as links to the most recent reports can be found at

http://ec.europa.eu/atwork/synthesis/index_en.htm

(9) In previous years, the results of this assessment were represented in a specific section ‘Reliability of Commission management representations’.

ANNEX 1.2

FOLLOW-UP OF OBSERVATIONS OF PRIOR YEARS CONCERNING THE RELIABILITY OF ACCOUNTS

|

Observations raised in prior years |

Court’s analysis of the progress made |

Commission reply |

||||||

|

|

|

||||||

|

For pre-financings, accounts payable and related cut-off, since the financial year 2007 the Court has identified accounting errors with an immaterial financial impact overall but a high frequency. This underlines the need for further improvement in the basic accounting data at the level of certain directorates-general. |

The Commission continued to work on improving the accuracy of its accounting data through ongoing actions such as the accounting quality project and the validation of local systems. The Court’s audit of representative samples of pre-financing and of invoices/cost claims again identified errors with an immaterial financial impact overall but a high frequency. Therefore, the Commission should continue to make further efforts to improve the basic accounting data at the level of certain directorates-general. |

The Commission will continue its efforts to further improve the quality of the accounting data and local systems are updated continuously to meet the accounting requirements. |

||||||

|

As regards accounting for amounts pre-financed, the Court also identified:

|

Despite the efforts of the accounting officer’s services to improve the situation, the Court found that several directorates-general continue to record estimates in the accounts even when they have an adequate basis for clearing the corresponding pre-financings. The issue of the financial engineering instruments was already addressed in the 2010 accounts on receipt of information provided by Member States on a voluntary basis. The Commission also proposed to amend the current legal framework and made appropriate proposals for the post 2013 period in order to make the transmission of the necessary information compulsory. For the advances paid to Member States for other aid schemes and for contributions to the European Globalisation Adjustment Fund, a corresponding asset of 2 512 million euro has been recognised for the first time in the 2011 consolidated accounts. Prior to 2011, Member States did not provide data to the Commission which would have allowed a reliable estimate to be made. Information now available indicates that these amounts would not have been material. Except for the advances for the aid schemes related to the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development, the unused amounts recognised for the aforementioned financial engineering instruments and other aid schemes have been established on the basis of the amounts contributed by the Commission, taking into consideration an estimate of the unused amounts on a straight line basis. The lack of information on the amounts actually used reduces significantly the usefulness of this information for management purposes. |

The Accounting Services have prepared a set of guidelines on the clearing of pre-financing which will be distributed once the review of the Financial Regulation will be completed. The legal basis for the financial engineering instruments as well as for the State aid prepaid amounts, including an annex to the declaration of expenditure has been implemented (amendment to the Council Regulation (EC) No 1083/2006 on 13 December 2011). Following this amendment, the European Commission has a legal basis to request the required information from the Member States. The above information will be used for the accounting purposes at the closure of the 2012 accounts. The unpaid amounts to the final beneficiaries are based on pro-rata temporis estimation. Since DG REGIO is currently at the sixth out of a seven year-programming period, it is not advisable to modify the methodology. Nevertheless, this approach is foreseen to be modified for the next programming period, providing it is accepted by the Member States with the new Financial Regulation. Once the legal basis for the new programming period of Structural Funds enters into force the Commission will be entitled to receive information on the amounts actually used, which will be used for the preparation of the annual accounts. These new requirements should also improve management information. The method used by the Commission for the 2011 accounts is the most cost-effective and has already been used in the 2010 accounts. |

||||||

|

Furthermore, as already mentioned in the Court’s 2009 Annual Report, some directorates-general did not comply with the requirement to register the invoices and cost statements within five working days of receipt. |

Despite improvements noted in the time taken to register new cost claims, some directorates-general still do not fully comply with the requirement to register their invoices and cost claims promptly. |

The Commission's services will continue their efforts in this direction. To this end local systems are updated constantly, for example cost claims received by DG AGRI and DG REGIO are treated within the delay. |

||||||

|

The Court noted in its 2010 Annual Report that the increased use of pre-financing in the EU budget and of new types of financial instruments makes it a matter of urgency for the Commission to revisit the relevant accounting rule in order to provide adequate guidance on the recognition and clearing of pre-financing. |

The relevant accounting rule was updated in 2012 in order to take into consideration the need to recognise the unused amounts of contributions to financial engineering instruments and advances paid for other aid schemes as an asset. |

The services are implementing the rule in the light of the Financial Instruments and State aid related payments (see reply above). |

||||||

|

|

|

||||||

|

In its 2007 Annual Report, the Court already stated that although the Commission had taken steps to increase and improve the information it provided on the corrective mechanisms applied to the EU budget, the information was not yet completely reliable because the Commission did not always receive reliable information from Member States. |

Despite the weaknesses still affecting the reliability and completeness of the data presented by the Member States, in particular in the area of cohesion, certain improvements were noted over the years. At the beginning of 2011, the Commission launched an audit of the Member States' systems for recoveries in the area of cohesion. The Commission's on-the-spot controls showed that the systems for recording and reporting data are not yet completely reliable in all Member States visited. Therefore, data from Member States in the area of cohesion are not disclosed in the notes to the 2011 financial statements. |

For agriculture, the Commission has booked the outstanding debts at Member State level and the corresponding value reduction, as well as the amounts recovered by the Member States in the 2011 accounts. For cohesion, the reliability of data on recoveries received from Member States has improved in comparison to the last period, but the Commission agrees it should be further improved. To this effect the Commission has launched beginning of 2011 a risk-based audit of the Member States' systems for recoveries, based on the reporting made each year as at 31 March with the objective to improve reporting of national financial corrections to the Commission, and ensure completeness, accuracy and timeliness of reporting. The first results have been reported in the 2011 annual activity reports of structural actions' directorates-general. |

||||||

|

Furthermore, the need to refine the financial reporting guidelines pertaining to what information is to be included and how it should be treated should be examined. |

The accounting officer's instructions provide the authorising officers by delegation guidance on the data to be supplied. The Court's audit found improvements in the application of this guidance. However, additional efforts are needed to improve the quality of the data presented. |

The Commission will continue its efforts to further improve the quality of the data presented. |

||||||

|

For the first time in its 2009 Annual Report, the Court criticised that for some areas of expenditure, the Commission does not systematically provide information reconciling the year in which the payment concerned is made, the year in which the related error is detected and the year in which the resulting financial correction is disclosed in the notes to the accounts. |

Information reconciling payments, errors, recoveries and financial corrections is not yet presented. The Court maintains its position that, wherever it is possible, such a reconciliation should be provided. Furthermore, a clear link should be established between amounts included in annual activity reports, in particular for establishing the residual error rate, and information on recoveries/financial corrections presented in the accounts. |

The Commission takes note of the requests of the Court and points out that this is seldom possible. In shared management financial corrections are not meant to recover irregular spending (which remains under the responsibility of the Member States) but rather to protect the EU budget from such irregularities. It is therefore not correct to link error rates of a given year to financial corrections and recoveries disclosed in the annual accounts of that same year. In addition, the differences in the timing of financial corrections and actual recoveries on one side, and error rates on the other also prevent this reconciliation. This later comment is not only relevant for shared management, but also for direct management, where recovery orders are either issued after the end of the (multiannual) grant period, or not issued, as a corrected cost statement is submitted by the beneficiary. The Commission repeats its comment that expenditure is controlled several years after the actual year of a given payment, primarily at programme closure. Furthermore, the financial correction may be the result of the detection of weaknesses in the control systems of Member States, in which case no direct link exists with payments. As a consequence it is neither possible nor relevant to reconcile the year of the payment concerned with the year that the financial correction is disclosed in the notes to the accounts. Additionally, Member States are primarily responsible for the prevention, detection and correction of errors and irregularities in the area of shared management. For agriculture, all amounts in the different tables in note 6 can be reconciled either with data available at Commission level or with the Member State declarations. As regards regional policy, the link between amounts used for the residual error rate in the annual activity report and information in the provisional accounts is possible for previous year's reporting and for information provided by Member States in advance of the regulatory deadline of 31 March, which is also the deadline for establishing the provisional accounts. The Commission encouraged Member States to report corrections as early as possible before 31 March to avoid this timing issue. |

||||||

|

At year end 2010, for cohesion, a total amount of 2,5 billion euro still remained to be implemented (i.e. ‘cashed’ through the receipt of a repayment by the Commission or payment by the Commission on the basis of a claim from which the Member State has deducted ineligible expenditure). The low implementation rate of 71 % was explained by the ongoing closure process for the programming period 2000-2006. Payment claims received end-2010 were not yet authorised, which meant that the related financial corrections could not be taken into account in the 2010 implementation figures. |

At the end of 2011, an amount of 2,5 billion euro remained to be implemented (implementation rate of 72 %). The amount as well as the implementation rate stayed at a similar level to last year because payment claims received end-2010 could still not be authorised. |

The closure of programmes is a complex procedure where numerous documents submitted by the Member State are checked, and where further information can be requested by the Commission so as to get evidence that the Member State did indeed deduct the financial corrections decided, especially for complex operational programmes, thus putting off further the calculation of the final balance to pay. In addition, the Commission only recognises the implementation of a financial correction when the final payment is duly authorised by the authorising officer, a step which is completed at the very end of the verification chain. For cohesion, the amount of corrections accepted by Member States but still to be implemented relates to 2000-2006 programmes and is reflected in final payment claims received by the Commission but not yet authorised due to the closure process where the Commission has to assess all information provided as coherent and complete. The Court recommended the Commission to take this prudent approach not to report such corrections as implemented, until final payments are authorised. |

||||||

|

The explanatory notes to the consolidated accounts contain information that some payments are likely to be corrected at a later date by the Commission's services or the Member States. However, despite repeated requests by the Court since 2005, the amounts and areas of expenditure which may be subject to further verification and clearance of accounts procedures are still not identified in the notes. |

Amounts subject to further verification and clearing are not yet disclosed in the notes to the consolidated accounts (contrary to quantifiable amounts of potential recoveries). |

The Financial Regulation allows the Commission to make ex-post checks on all expenditure for several years after the actual year of expenditure. The accounts should not imply that, because of verifications in future years, all the expenditure concerned remains to be accepted. Otherwise, all budgetary expenditure would be considered provisional until an ex-post check is made or the said limitation period has lapsed. Where the amounts of potential recoveries are quantifiable, they are disclosed in note 6 to the consolidated accounts. In agriculture, a financial clearance decision is taken around six months after the end of the financial year in question, through which the Commission establishes the amount of expenditure recognised as chargeable to the EU budget for that year. This role of the financial clearance decision is not called into question by the fact that subsequently financial corrections may be imposed on Member States through conformity decisions. The amount of expenditure which is likely to be excluded from EU financing by such future conformity decisions is disclosed in a note to the financial statements. |

||||||

|

|

|

||||||

|

The agreements for the transfer to the Union of the ownership of all assets created, developed or acquired for the Galileo programme have not yet been fully implemented. As all expenditure incurred since 2003 was treated as research expenses there was no impact on the balance sheet at 31 December 2010. However, the Commission should ensure that all information is available at the time when the transfer takes place in order to safeguard assets effectively. |

The Commission is working with the European Space Agency to ensure that at the time of the transfer all the necessary accounting and technical information will be available to guarantee a smooth handover. This transfer is planned for the end of the in orbit validation phase (end of 2012 at the earliest). In the meantime, the Commission recognised in 2011 an amount of 219 million euro as assets under construction relating to the Galileo project. This amount reflects the costs incurred by the Commission since 22 October 2011, the date on which the first two satellites of the system were successfully launched. Prior to this date the Commission considered the project still to be in a research phase and all costs incurred were expenses. However, the Court’s review revealed immaterial weaknesses in the cut-off procedure establishing the amount of assets under construction. |

The Commission considers the amounts recognised on the balance sheet as reasonably accurate and reliable. The accounting methodology and procedures for the valuation of the Galileo assets are in full compliance with the EU accounting rules and the IPSAS standards. The valuation of the assets was determined with the support of independent external accounting experts based on data provided by ESA. The Commission has performed necessary checks to reasonably ensure the reliability of the outcome. |

||||||

|

In its 2010 Annual Report, the Court drew attention to the reservation made by the responsible director-general in his 2010 annual activity report concerning the reliability of the European Space Agency’s financial reporting. |

The responsible director-general maintained the reservation in his 2011 annual activity report and widened its scope. |

The Commission will continue auditing the financial reports provided by ESA and will encourage and support ESA in implementing its actions towards further improving the quality of financial reporting to the Commission. An external review of the control systems of the European Space Agency was finalised in 2012, disclosing satisfactory results. Given the actions currently under way, the Commission expects the issues to be corrected soon which will enable reducing and finally lifting this reservation. |

ANNEX 1.3

EXTRACTS FROM THE 2011 CONSOLIDATED ACCOUNTS (1)

Table 1 — Balance sheet (2)

|

(million euro) |

||

|

|

31.12.2011 |

31.12.2010 |

|

Non-current assets: |

||

|

Intangible assets |

149 |

108 |

|

Property, plant and equipment |

5 071 |

4 813 |

|

Long-term investments: |

||

|

Investments accounted for using the equity method |

374 |

492 |

|

Financial assets: Available for sale assets |

2 272 |

2 063 |

|

Financial assets: Long-term loans |

41 400 |

11 640 |

|

Long-term receivables and recoverables |

289 |

40 |

|

Long-term pre-financing |

44 723 |

44 118 |

|

|

94 278 |

63 274 |

|

Current assets: |

||

|

Inventories |

94 |

91 |

|

Short-term investments: |

||

|

Financial assets: Available for sale assets |

3 619 |

2 331 |

|

Short-term receivables and recoverables: |

||

|

Financial assets: Short-term loans |

102 |

2 170 |

|

Other receivables and recoverables |

9 477 |

11 331 |

|

Short-term pre-financing |

11 007 |

10 078 |

|

Cash and cash equivalents |

18 935 |

22 063 |

|

|

43 234 |

48 064 |

|

Total assets |

137 512 |

111 338 |

|

Non-current liabilities: |

||

|

Pension and other employee benefits |

(34 835) |

(37 172) |

|

Long-term provisions |

(1 495) |

(1 317) |

|

Long-term financial liabilities |

(41 179) |

(11 445) |

|

Other long-term liabilities |

(2 059) |

(2 104) |

|

|

(79 568) |

(52 038) |

|

Current liabilities: |

||

|

Short-term provisions |

(270) |

(214) |

|

Short-term financial liabilities |

(51) |

(2 004) |

|

Payables |

(91 473) |

(84 529) |

|

|

(91 794) |

(86 747) |

|

Total liabilities |

(171 362) |

(138 785) |

|

Net assets |

(33 850) |

(27 447) |

|

Reserves |

3 608 |

3 484 |

|

Amounts to be called from Member States |

(37 458) |

(30 931) |

|

Net assets |

(33 850) |

(27 447) |

Table 2 — Economic outturn account (3)

|

(million euro) |

||

|

|

2011 |

2010 |

|

Operating revenue |

||

|

Own resource and contributions revenue |

124 677 |

122 328 |

|

Other operating revenue |

5 376 |

8 188 |

|

|

130 053 |

130 516 |

|

Operating expenses |

||

|

Administrative expenses |

(8 976) |

(8 614) |

|

Operating expenses |

(123 778) |

(103 764) |

|

|

(132 754) |

(112 378) |

|

(Deficit)/Surplus from operating activities |

(2 701) |

18 138 |

|

Financial revenue |

1 491 |

1 178 |

|

Financial expenses |

(1 355) |

(661) |

|

Movement in pension and other employee benefits liability |

1 212 |

(1 003) |

|

Share of net deficit of joint ventures and associates |

(436) |

(420) |

|

Economic outturn for the year |

(1 789) |

17 232 |

Table 3 — Cashflow table (4)

|

(million euro) |

||

|

|

2011 |

2010 |

|

Economic outturn for the year |

(1 789) |

17 232 |

|

Operating activities |

||

|

Amortisation |

33 |

28 |

|

Depreciation |

361 |

358 |

|

(Increase)/decrease in long-term loans |

(29 760) |

(876) |

|

(Increase)/decrease in long-term pre-financing |

(605) |

(2 574) |

|

(Increase)/decrease in long-term receivables and recoverables |

(249) |

15 |

|

(Increase)/decrease in inventories |

(3) |

(14) |

|

(Increase)/decrease in short-term pre-financing |

(929) |

(642) |

|

(Increase)/decrease in short-term receivables and recoverables |

3 922 |

(4 543) |

|

Increase/(decrease) in long-term provisions |

178 |

(152) |

|

Increase/(decrease) in long-term financial liabilities |

29 734 |

886 |

|

Increase/(decrease) in other long-term liabilities |

(45) |

(74) |

|

Increase/(decrease) in short-term provisions |

56 |

1 |

|

Increase/(decrease) in short-term financial liabilities |

(1 953) |

1 964 |

|

Increase/(decrease) in payables |

6 944 |

(9 355) |

|

Prior year budgetary surplus taken as non-cash revenue |

(4 539) |

(2 254) |

|

Other non-cash movements |

(75) |

(149) |

|

Increase/(decrease) in pension and employee benefits liability |

(2 337) |

(70) |

|

Investing activities |

||

|

(Increase)/decrease in intangible assets and property, plant and equipment |

(693) |

(374) |

|

(Increase)/decrease in long-term investments |

(91) |

(176) |

|

(Increase)/decrease in short-term investments |

(1 288) |

(540) |

|

Net cashflow |

(3 128) |

(1 309) |

|

Net increase/(decrease) in cash and cash equivalents |

(3 128) |

(1 309) |

|

Cash and cash equivalents at the beginning of the year |

22 063 |

23 372 |

|

Cash and cash equivalents at year end |

18 935 |

22 063 |

Table 4 — Statement of changes in net assets (5)

|

(million euro) |

|||||

|

|

Reserves (A) |

Amounts to be called from Member States (B) |

Net assets = (A) + (B) |

||

|

Fair value reserve |

Other reserves |

Accumulated surplus/(deficit) |

Economic outturn for the year |

||

|

Balance as at 31 December 2009 |

69 |

3 254 |

(52 488) |

6 887 |

(42 278) |

|

Movement in Guarantee Fund reserve |

|

273 |

(273) |

|

0 |

|

Fair value movements |

(130) |

|

|

|

(130) |

|

Other |

|

4 |

(21) |

|

(17) |

|

Allocation of the economic outturn 2009 |

|

14 |

6 873 |

(6 887) |

0 |

|

Budget result 2009 credited to Member States |

|

|

(2 254) |

|

(2 254) |

|

Economic outturn for the year |

|

|

|

17 232 |

17 232 |

|

Balance as at 31 December 2010 |

(61) |

3 545 |

(48 163) |

17 232 |

(27 447) |

|

Movement in Guarantee Fund reserve |

|

165 |

(165) |

|

0 |

|

Fair value movements |

(47) |

|

|

|

(47) |

|

Other |

|

2 |

(30) |

|

(28) |

|

Allocation of the economic outturn 2010 |

|

4 |

17 228 |

(17 232) |

0 |

|

Budget result 2010 credited to Member States |

|

|

(4 539) |

|

(4 539) |

|

Economic outturn for the year |

|

|

|

(1 789) |

(1 789) |

|

Balance as at 31 December 2011 |

(108) |

3 716 |

(35 669) |

(1 789) |

(33 850) |

Table 5 — EU budget outturn (6)

|

(million euro) |

||

|

European Union |

2011 |

2010 |

|

Revenue for the financial year |

130 000 |

127 795 |

|

Payments against current year appropriations |

(128 043) |

(121 213) |

|

Payment appropriations carried over to year N+1 |

(1 019) |

(2 797) |

|

Cancellation of unused payment appropriations carried over from year N-1 |

457 |

741 |

|

Exchange differences for the year |

97 |

23 |

|

Budget outturn (7) |

1 492 |

4 549 |