EUR-Lex Access to European Union law

This document is an excerpt from the EUR-Lex website

Document 32016G1129(01)

Council Resolution concerning an updated handbook with recommendations for international police cooperation and measures to prevent and control violence and disturbances in connection with football matches with an international dimension, in which at least one Member State is involved (‘EU Football Handbook’)

Council Resolution concerning an updated handbook with recommendations for international police cooperation and measures to prevent and control violence and disturbances in connection with football matches with an international dimension, in which at least one Member State is involved (‘EU Football Handbook’)

Council Resolution concerning an updated handbook with recommendations for international police cooperation and measures to prevent and control violence and disturbances in connection with football matches with an international dimension, in which at least one Member State is involved (‘EU Football Handbook’)

OJ C 444, 29.11.2016, p. 1–36

(BG, ES, CS, DA, DE, ET, EL, EN, FR, HR, IT, LV, LT, HU, MT, NL, PL, PT, RO, SK, SL, FI, SV)

- Date of document:

- 29/11/2016; Date of publication

- Author:

- Council of the European Union

- Form:

- Resolution

- Treaty:

- Treaty on European Union

- Link

- Link

- Link

- Link

- Link

- Select all documents mentioning this document No data available in the table

- Modifies:

-

Relation Act Comment Subdivision concerned From To Replacement 32010G0624(01)

No data available in the table

- Modified by:

-

Relation Act Comment Subdivision concerned From To Corrected by 32016G1129(01)R(01) - Instruments cited:

- Link

- EUROVOC descriptor:

- Subject matter:

- Directory code:

|

29.11.2016 |

EN |

Official Journal of the European Union |

C 444/1 |

Council Resolution concerning an updated handbook with recommendations for international police cooperation and measures to prevent and control violence and disturbances in connection with football matches with an international dimension, in which at least one Member State is involved (‘EU Football Handbook’)

(2016/C 444/01)

THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION,

Whereas:

|

(1) |

The European Union's objective is, inter alia, to provide citizens with a high level of safety within an area of freedom, security and justice, by developing common action among the Member States in the field of police cooperation as laid down under Title V of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. |

|

(2) |

On 21 June 1999, the Council adopted a resolution concerning a handbook for international police cooperation and measures to prevent and control violence and disturbances in connection with international football matches (1). |

|

(3) |

This resolution was first replaced by the Council Resolution of 6 December 2001 (2) and subsequently by the Council Resolutions of 4 December 2006 (3) and 3 June 2010 (4) concerning a handbook with recommendations for international police cooperation and measures to prevent and control violence and disturbances in connection with football matches with an international dimension, in which at least one Member State is involved (hereafter the EU Football Handbook). |

|

(4) |

The current resolution suggests that amendments to the handbook be made in the light of recent experiences. |

|

(5) |

Taking into account recent experiences in connection with the European Championships in 2012 and the World Cup 2014, the development of established good practice in the framework of those tournaments, extensive police cooperation in relation to international and club matches in Europe generally and the views of over 300 police practitioners (match commanders, National Football Information Point personnel and other football policing specialists) from the 25 European countries (5) that participated in the Pan-European Football Policing Training Project between 2011 and 2014, the EU Football Handbook has been revised and updated. |

|

(6) |

The changes included in the annexed updated handbook are without prejudice to existing national provisions, in particular the division of responsibilities among the different authorities and services in the Member States concerned, and to the exercise by the Commission of its powers under the Treaties, |

HEREBY,

|

(1) |

REQUESTS that Member States continue to further enhance police cooperation in respect of football matches (and, where appropriate, other sporting events) with an international dimension. |

|

(2) |

DEMANDS that to that end, the updated handbook annexed hereto, providing examples of strongly recommended working methods, should be made available to, and adopted by, law enforcement authorities involved in policing football matches with an international dimension. |

|

(3) |

STATES that, where appropriate, the recommended working methods may be applied to other major international sporting events. |

|

(4) |

This Resolution replaces the Council Resolution of 3 June 2010. |

(1) OJ C 196, 13.7.1999, p. 1.

(3) OJ C 322, 29.12.2006, p. 1.

(4) OJ C 165, 24.6.2010, p. 1.

(5) Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Sweden and United Kingdom, as well as Switzerland, Serbia, Turkey and Ukraine.

ANNEX

Handbook with recommendations for international police cooperation and measures to prevent and control violence and disturbances in connection with football matches with an international dimension, in which at least one Member State is involved (‘EU Football Handbook’)

Handbook Contents

ChapterSubject

| Purpose, Scope and Use of the Handbook | 4 |

|

1 |

Information Management and Exchange by the Police | 5 |

|

1.1 |

Introduction | 5 |

|

1.2 |

Tasks with an International Dimension | 5 |

|

1.3 |

Exchange of Police Information | 6 |

|

1.3a |

Definitions | 6 |

|

1.3b |

Kinds of Information | 6 |

|

1.3c |

Chronological Sequence of Information Exchange | 6 |

|

1.3d |

Information Exchange with Non-EU Countries | 7 |

|

1.4 |

Counter-Terrorism and Serious and Organised Criminality | 7 |

|

2 |

General Guidance on the National Role and Tasks of NFIPs | 8 |

|

3 |

Cooperation between Host Police and Visiting Police Delegations | 8 |

|

3.1 |

Key Principles | 8 |

|

3.2 |

Supporting Host Policing Operations | 8 |

|

3.3 |

Cooperation Arrangements | 9 |

|

3.4 |

Model Protocols for One-Off Matches | 9 |

|

3.5 |

Costs and Financial Arrangements | 10 |

|

3.6 |

Pre-Visits | 10 |

|

3.7 |

Accompanying Visiting Police Delegations (Cicerones) | 11 |

|

3.8 |

Composition of Visiting Police Delegations | 11 |

|

3.9 |

Key Tasks of the Visiting Police Delegation | 12 |

|

3.10 |

Language | 13 |

|

3.11 |

Cooperation between Host and Visiting Police during the Event | 13 |

|

3.12 |

Use of Identification Vests | 13 |

|

3.13 |

Accreditation | 13 |

|

3.14 |

Football Tournaments in Countries without an NFIP | 13 |

|

3.14a |

Bilateral Agreements | 13 |

|

3.14b |

NFIP Cooperation | 14 |

|

3.15 |

Role of Interpol and Europol | 14 |

|

4 |

Cooperation between the Police and the Organiser | 14 |

|

5 |

Cooperation between Police and Justice and Prosecuting Agencies | 15 |

|

6 |

Cooperation between Police and Supporters | 16 |

|

7 |

Communication and Media Strategy | 16 |

|

7.1 |

Communication Strategy | 16 |

|

7.2 |

Media Strategy | 17 |

|

8 |

EU Football Safety and Security Experts Meetings | 17 |

|

9 |

List of Relevant Documents on Safety and Security at Football Events | 18 |

|

9.1 |

Key documents previously adopted by the Council of the European Union | 18 |

|

9.2 |

Key documents previously adopted by the Council of Europe | 18 |

|

Appendix 1 |

Protocol for Deployment of Visiting Police Delegations (Prüm) | 19 |

|

Appendix 2 |

Protocol for Deployment of Visiting Police Delegations (Non-Prüm) | 25 |

|

Appendix 3 |

Specifications for Police Identification Vests | 30 |

|

Appendix 4 |

Dynamic Risk Assessment & Crowd Management | 32 |

|

Appendix 5 |

Categorisation of Football Supporters | 35 |

Purpose, Scope and Use of the Handbook

The purpose of this document is to enhance safety and security at football matches with an international dimension, and in particular to maximise the effectiveness of international police cooperation.

The content, which is consistent with the established good practice of adopting an integrated multi-agency approach to football safety, security and service, can, where appropriate, be applied to other sporting events with an international dimension if a Member State so decides.

The content is without prejudice to existing national provisions, in particular the competencies and responsibilities of the different agencies within each Member State.

Although this document is mainly focused on international police cooperation, the multi-agency character of managing football (and other sporting events) is reflected in references to police interaction with other key partners, such as the event organiser, and stakeholders, notably supporters.

International police cooperation and football policing operations must be guided by the principles of legality, proportionality and adequacy. Examples of good practice in relation to dynamic risk assessment and crowd management are detailed in Appendix 4.

Whilst the competent authority in the organising Member State is responsible for providing a safe and secure event, authorities in participating, neighbouring and transit states have a responsibility to assist where appropriate.

This document should be widely disseminated and applied in each Member State and other European countries and beyond in order to minimise safety and security risks and ensure effective international police cooperation.

CHAPTER 1

1. Information Management and Exchange by the Police

1.1. Introduction

The timely exchange of accurate information is of the utmost importance in enhancing safety and security and preventing football-related violence and disorder.

In accordance with Council Decision 2002/348/JHA, as amended by Council Decision 2007/412/JHA of 12 June 2007, each Member State has to establish a National Football Information Point (NFIP) to act as the central national contact point for the exchange of relevant information for football matches with an international dimension, and for facilitating international police cooperation concerning football matches.

Where there is direct contact between organising and visiting police, any information exchanged should be shared simultaneously with the relevant NFIPs. Such contact should not jeopardise the key role of the NFIP in ensuring the quality of the information and wider dissemination to other relevant partners and authorities.

The relationship between the NFIP and the competent national authorities should be subject to the applicable national laws.

In accordance with Article 1(4) of Council Decision 2002/348/JHA, each Member State has to ensure that its national football information point is capable of fulfilling efficiently and promptly the tasks assigned it.

|

— |

In order to be effective, NFIP personnel should be trained and equipped to provide a national source of expertise regarding football policing and associated safety and security matters. |

1.2. Tasks with an International Dimension

The NFIP supports the competent national authorities. On the basis of information that has been analysed and assessed, the necessary proposals or recommendations are sent to the competent national authorities to assist in developing a multi-agency policy on football-related issues.

The NFIP works closely with local police with regard to national or international football matches. To be fully effective in the provision of this support, information on the important role of the NFIP should be widely disseminated and understood by all policing agencies in each Member State.

Each Member State should also make arrangements to establish a national network of designated local police personnel tasked to gather and supply the NFIP with all information and intelligence regarding football events in their locality.

For the benefit of other countries' NFIPs, each NFIP is required to maintain an updated risk analysis (1) in relation to its own clubs and its national team. The risk analysis is generally shared with other NFIPs using the forms available on the NFIP website (www.nfip.eu) (2). It is stressed, however, that risk is variable and dependent upon a range of factors. Accordingly, a dynamic risk assessment needs to be undertaken throughout an event.

Each NFIP should have access to the relevant national police databases. The exchange of personal information is subject to the applicable national and international law, especially the Prüm Decision (3) or bi-national or multilateral agreements.

The NFIP is required to ensure that all information is subject to quality control in respect of content.

All information should be exchanged using the appropriate forms provided on the NFIP website.

1.3. Exchange of Police Information

1.3a

The term ‘event’ in this handbook is used to mean a specific football match or tournament in all its aspects. The term ‘host police’ is used to mean the police in the country in which the match or tournament is being held. The term ‘visiting police’ is used to describe the police in, or from, a country in which the participating team or teams is located.

1.3b

A distinction can be made between general information and personal information.

(a) General information

General information includes strategic and tactical information designed to inform event preparations and operations in respect of identifying and preventing or reducing safety and security risks, undertaking pre-event and ongoing dynamic risk analyses, and responding appropriately and proportionately to safety and security risks as they emerge during the event.

(b) Personal information

In this context, personal information refers to information on individuals who are assessed by the police as posing a potential risk to public safety in connection with the event. This may include details of individuals who have evidently caused or contributed to violence or disorder in connection with previous football matches.

1.3c

Three phases may be distinguished: before, during and after the event. These three phases need not always be strictly separated.

Before the event

Information requirements are forwarded by the host NFIP to the NFIP of the visiting country/countries. These requirements include:

|

— |

a risk analysis of supporters of the visiting team; |

|

— |

other relevant information regarding the safety and security of the event, e.g. supporter travel details and other public order threats. |

The NFIP of the visiting country/countries responds to the information requirements of the host country NFIP and, on its own initiative, provides all relevant information to any other NFIPs concerned.

The NFIP of the host country provides information on the applicable legislation and policy of the authorities (e.g. alcohol policy), the organisation of the event and on key safety and security personnel.

All relevant information is put at the disposal of the other NFIPs concerned and entered on the NFIP website via the appropriate forms.

The NFIP of the visiting country/countries is requested to provide timely and accurate information regarding the movements of risk and non-risk supporters, the participating team (where there is a threat) and ticket sales, together with any other relevant information.

The NFIP of the host country provides information to the NFIP of the visiting country/countries, particularly on the integration of the visiting police delegation into the host policing operation, as well as information for visiting supporters, etc.

During the event

The NFIP of the host country can request confirmation of the information previously provided and request an updated risk analysis. The request is forwarded and answered via a system of liaison officers if such a system has been set up.

The host country NFIP should keep the visiting country NFIP informed when relevant incidents occur during the event.

The NFIP of the visiting country/countries monitors and, where appropriate, provides the host NFIP with updated information on the movements and whereabouts of the visiting supporters. Useful information concerning event-related incidents in their home country during the matches or tournaments is also provided to the host country and any other relevant NFIP.

General information regarding the return of supporters, including any that have been expelled and/or refused entry, is also provided to the NFIPs of the country of origin and the relevant transit countries.

After the event

Within five working days of the event, the NFIP of the host country provides the NFIP of the visiting country (via the appropriate forms on the NFIP website) with information:

|

— |

regarding the behaviour of supporters so that the risk analysis can be updated by the NFIPs of the country/club they support and/or their place of residence; |

|

— |

on the operational usefulness of the information they have provided and of the support provided by the visiting police delegation(s); |

|

— |

the description of any incident: information regarding arrests or sanctions is exchanged in accordance with national and international law. Where possible this information should include:

|

Based on the information provided by the host country NFIP and the visiting police delegation, the visiting NFIP then updates its generic risk analysis.

The host and visiting NFIPs will cooperate to assess the effectiveness of the information exchange arrangements and the work of the visiting police delegation.

1.3d

NFIPs are the proper channel for the exchange of information with NFIPs in non-EU countries. If a country does not have an NFIP, the governmental departmental responsible for policing matters should be asked to designate a central police contact point. Contact details should be forwarded to other NFIPs and entered on the NFIP website.

1.4. Counter-Terrorism and Serious and Organised Criminality

For the exchange of information on matters such as counter-terrorism and serious and organised crime, the competent police agency in the host country may communicate through any existing network or specialist liaison officers appointed for that purpose.

CHAPTER 2

2. General Guidance on the National Role and Tasks of NFIPs

At a national level, the NFIP should act as a national source of expertise on football policing matters. In fulfilling this role, the NFIP should undertake a range of key football-related tasks, including:

|

— |

coordinating the exchange of information regarding football matches played in domestic competitions; |

|

— |

gathering and analysing data on football-related incidents (inside and outside stadia) along with associated arrests and detentions and the outcome of any judicial or administrative proceedings that ensue; |

|

— |

gathering and analysing information on the imposition of exclusion measures and, where appropriate, manage compliance with such exclusion measures; |

|

— |

where appropriate, coordinating and organising the training and work of intelligence officers and/or spotters. |

An NFIP can enter into a formal bilateral agreement with a third party regarding the exchange of certain information in accordance with their own national legislation. This information cannot be further shared without the agreement of the originator.

NFIPs can have a key role to play in assisting police match commanders in the delivery of their strategic and operational priorities at all matches with an international dimension. The key priorities for host policing operations should include:

|

— |

providing a safe, secure and welcoming environment for supporters and local communities; |

|

— |

managing all policing-related aspects of the event; |

|

— |

determining policing preparations and operational strategies informed by police risk assessments; |

|

— |

monitoring emerging risk scenarios and responding proportionately, through early targeted intervention, to prevent escalation of the risk; |

|

— |

maximising the use of information and advice on visiting supporter dynamics provided by visiting police delegations; and |

|

— |

facilitating an understanding of how best to accommodate potentially different visiting policing cultures, styles and tactics in the host policing operation. |

CHAPTER 3

3. Cooperation between Host Police and Visiting Police Delegations

3.1. Key Principles

Countries which have the legal possibility to prevent risk supporters from travelling abroad should take all the necessary measures to achieve this objective effectively and should inform the organising country accordingly. Each country should take all possible measures to prevent its own citizens from participating in and/or organising public order disturbances in another country.

The vital role played by visiting police delegations in supporting the policing operations of host countries is shown by widespread European experience over the past decade.

3.2. Supporting Host Policing Operations

In addition to the comprehensive exchange of information, and in accordance with the principles in chapter 1 of this handbook, the organising NFIP, following close consultation with the competent operational policing agency, should invite a visiting police delegation from the visiting country or countries whenever there is a major tournament.

To provide added value to the policing operations of the organising country, it is crucial that visiting police delegations comprise personnel with knowledge and experience of the dynamics and behaviour of the visiting supporters.

During an event, the visiting police delegation should be viewed as a primary source of information about visiting supporters, their behaviour and any potential risks. This added value for the host police commander can include:

|

— |

appropriate crowd management of regular fans; |

|

— |

obtaining and sharing pre-match and match-day intelligence; |

|

— |

close monitoring of events in order to provide the organising police with timely and accurate information; |

|

— |

monitoring and interpreting visiting supporter behaviour and identifying and monitoring risk fans and potential risk scenarios to inform an ongoing dynamic risk assessment (see Appendix 5); |

|

— |

where agreed with the head of the visiting delegation, and following a police risk assessment, proactively intervening to prevent escalation of any misbehaviour by visiting supporters; |

|

— |

communicating with visiting supporters and acting as a bridge between the supporters and the host police to help address any potential or emerging concerns; |

|

— |

gathering evidence of any criminality and misbehaviour and criminal offences and identifying visiting offenders. |

3.3. Cooperation Arrangements

In accordance with Council Decision 2002/348/JHA, for one-off football matches with an international dimension, the formal invitation for a visiting police delegation should be transmitted via the NFIP in the host country. Taking into account the specific aims of cooperation, the invitation should indicate the composition of the delegation and clarify their roles and responsibilities. It should also specify the intended duration of the visiting police delegation's stay in the host country.

For international tournaments and one-off matches (if requested by either NFIP) the formal invitation for a visiting police delegation should be sent by the competent authority in the host country, on the advice of the host country NFIP, and can be subject to an inter-governmental agreement.

If a visiting police delegation is not invited by the host NFIP, the NFIP of the visiting country can, if deemed appropriate, submit a proactive proposal to the host NFIP to send a delegation. If the host NFIP does not accept the proposal, any police delegation that travels will be acting in an unofficial capacity outside the scope of this handbook.

The detailed invitation to provide support should be agreed between the NFIPs concerned well in advance of a tournament and/or one-off match to allow the visiting police delegation sufficient preparation time. With this in mind, an invitation to provide support should be presented as soon as possible after the announcement of the date of the match.

For one-off matches with an international dimension the visiting police delegation will require at least three weeks' preparation time. If there is less than three weeks' prior notice of a match (for example in the later stages of a European club competition or due to an increased level of risk) the invitation should be sent immediately. For international tournaments, the visiting police delegation will require at least 16 weeks' preparation time.

The detail of the arrangements (e.g. police powers, equipment, uniforms etc.) for the visiting police delegation are negotiated between the NFIPs, following consultation with the local police for the one-off match.

3.4. Model Protocols for One-Off Matches

Section 3.14 provides a model for negotiating bilateral agreements on the international police cooperation arrangements that will apply in respect of major football tournaments.

However, it is strongly recommended that the arrangements for deploying a visiting police delegation for one-off football matches with an international dimension should be agreed in advance by the host and visiting countries and set out in a protocol. Model protocols are provided in Appendix 1, for use when both countries are party to the Prüm Treaty, and Appendix 2, for use in circumstances when one or both countries are not subject to the Prüm Treaty.

If a bi-national governmental agreement is not in place, these arrangements should comply with Article 17 of Council Decision 2008/616/JHA (4) and the applicable national laws.

The visiting delegation should not exceed the number agreed by the host NFIP and should respect the host police command and control arrangements. If they act in a manner that is not within the terms of the agreement then they are acting outside of the scope of this handbook and the applicable EU Council Decisions and Treaties.

3.5. Costs and Financial Arrangements

The costs involved in hosting and deploying a visiting police delegation will vary in accordance with a number of factors, including size of delegation, distance and means of travel etc., but on average the costs are modest and represent a sound investment in reducing safety and security risks (5). It is strongly recommended that each Member State makes budgetary provision to host and send visiting police delegations for all matches with an international dimension.

On each occasion the host country should pay for accommodation, meals (or subsistence) and domestic travel required in the host country, whilst the visiting country should pay for international travel and salaries of the delegation members involved (unless the respective NFIPs exceptionally agree alternative arrangements). These arrangements need to be clarified in the aforementioned visiting police delegation protocol for deployment of visiting police delegations, as available on the NFIP website.

3.6. Pre-Visits

The police in the host country should give key members of the visiting police delegation an opportunity to acquaint themselves with the organisation of police operations in the host country and/or the venue town(s) and with the stadium location, and to get to know the operational commander(s) at the venue town(s) on the match day(s):

|

— |

for international tournaments, this should take place no later than six weeks before the tournament (e.g. by hosting workshops or seminars for key members of visiting police delegations). |

|

— |

for one-off matches with an international dimension this should be on one of the days prior to the match. |

Such pre-visits provide an ideal opportunity for host and visiting police representatives to maximise international cooperation by:

|

— |

sharing logistical information on supporter arrangements in the host city/town; |

|

— |

visiting locations where visiting supporters are expected to gather before and after the match; |

|

— |

discussing and agreeing on the role of the visiting delegation; |

|

— |

increasing awareness about host policing preparations and operations; |

|

— |

planning for the integration of the visiting delegation into the operation; |

|

— |

identifying relevant legislative provisions and police tolerance levels; |

|

— |

building trust and effective liaison channels between the two policing agencies; and |

|

— |

where appropriate, identifying measures to separate supporter groups in the host city/town. |

3.7. Accompanying Visiting Police Delegations

Ensuring the safety of all members of a visiting police delegation is paramount and must be reflected in all host and visiting police risk assessments concerning police deployment.

Visiting members of a police delegation, in particular the liaison officer, operations coordinator and operational police officers (see below) should work alongside local police officers (commonly known as cicerones) who themselves should be serving police officers with experience of policing football in their own city or country, including familiarity with the venue area and potential risk areas.

Cicerones:

|

— |

should be integrated into the national/local policing operation and be able to relay information enabling operational police commanders to make key decisions; |

|

— |

should have knowledge of their police organisation, processes and command structure; |

|

— |

should not be tasked with monitoring their own risk supporters whilst they are deployed accompanying members of a visiting police delegation; |

|

— |

should be thoroughly briefed on the host policing operation, their responsibilities, and on the tasks expected to be performed by the members of the visiting police delegation; |

|

— |

should be responsible for the safety of visiting police delegation and provide a channel of communication with the host police; |

|

— |

should be deployed with the visiting police delegation for the duration of the operation; this will assist in developing an effective working relationship; |

|

— |

should work with the visiting police delegation in a common language agreed beforehand. |

3.8. Composition of Visiting Police Delegations

The visiting police delegation should be composed in such a way that it is able to support the host country policing operation.

Depending on the exact nature of the support to be provided, the composition of the delegation could be as follows:

|

1. |

a head of delegation who is functionally and hierarchically in charge of the visiting police delegation; |

|

2. |

a liaison officer (or more if agreed by the respective NFIPs) who is responsible in particular for the exchange of information between his/her home country and the organising country; |

|

3. |

an operations coordinator who is responsible for coordinating the work of the visiting operational police officers; |

|

4. |

police spotters with spotting, supporter liaison, escorting and other duties; |

|

5. |

a spokesperson/press officer for media liaison. |

During international tournaments the liaison officer is likely to be based in a single or bi-national Police Information Coordination Centre (PICC), whilst the operations coordinator may be based in a local information centre in the locality of the venue city. For one-off matches they may be based in the organising country NFIP or another appropriate environment.

For a one-off match the liaison officer/operations coordinator should work closely with the host police in the venue city.

The host police should provide the liaison officers/operations coordinators with access to the relevant technical equipment so that they can perform their functions effectively.

The visiting police delegation can be deployed in plain clothes or in uniform.

3.9. Key Tasks of the Visiting Police Delegation

To provide added value to the policing operations of the organising country, it is crucial that visiting police delegations comprise personnel with knowledge and experience of the dynamics and behaviour of the visiting supporters.

The visiting police delegation should have the following competencies:

|

— |

a good working knowledge of this handbook; |

|

— |

an understanding of the processes required to facilitate the international exchange of information; |

|

— |

the ability to represent their country and their role effectively when liaising with the organising police services (i.e. be diplomatic, self-confident, independent and able to communicate in a common language agreed beforehand); |

|

— |

a background knowledge of the situation concerning football-related violence/disorder in their country. |

The main tasks of the delegation can be summarised as:

|

— |

gathering and transferring information/intelligence within their delegation and to the host police; |

|

— |

ensuring effective deployment of their operational police officers (in uniform and/or plain clothes) in order to play an integral role in the host police operation for the event; |

|

— |

providing timely and accurate advice to the host police commander. |

The primary role of the head of delegation is to act as a strategic and tactical advisor to the host authorities.

The primary role of a liaison officer and/or an operations coordinator (which may or may not be the same person depending upon the bilateral police deployment agreement) is to facilitate effective exchange of information between the visiting and host country authorities in connection with a one-off football match or a tournament. If neither a liaison officer nor an operations coordinator is appointed, their functions should be undertaken by the head of delegation.

Operational police officers deployed within a delegation are known as police spotters.

Police spotters, whether in uniform or plain clothes, can:

|

— |

be used by the host police as a means of interacting with visiting supporters in order to assist crowd management; |

|

— |

assist in reducing the anonymity of risk supporters in a crowd, and their ability to instigate and/or participate in acts of violence or disorder without further consequences. |

The spotters should have experience in the policing of football matches in their own country.

They should:

|

— |

have the skills and experience to communicate effectively (where appropriate) in order to influence the behaviour of supporters; and/or |

|

— |

be specialists in the behaviour of, and the potential risks posed by their supporters; and |

|

— |

be able to communicate effectively during the event with host police regarding the type of risk that visiting supporters may or may not pose at any given time and place. |

Spotters should be able to communicate positive, as well as negative, information concerning their visiting supporters. This will allow the host country police commanders to make balanced decisions around the need to intervene or facilitate legitimate supporter behaviour.

Subject to the agreement of the host country, visiting spotters can also be deployed to gather intelligence/evidence, using agreed equipment, for use by the organising police or for prosecution purposes in their own country.

3.10. Language

Language arrangements should be made in advance by the countries concerned.

Where possible, visiting police delegations should include personnel skilled in the language of the host country to facilitate communication between the host and visiting police personnel.

3.11. Cooperation between Host and Visiting Police during the Event

The visiting police delegation should be kept informed about the host police operational plan (including their crowd management philosophy and behavioural tolerance levels). They should be fully integrated into the host police operation (and given the possibility to attend and participate in pre-match briefing and post-match debriefing meetings).

The host police and the visiting police delegation should keep their respective NFIPs informed of developments throughout the operation and submit a post-match report to their NFIP within five working days.

The visiting police delegation should always ensure that their actions do not unnecessarily jeopardise the safety of other persons (6).

3.12. Use of Identification Vests

When it is jointly agreed for tactical reasons, visiting police officer(s) who are not deployed in uniform can use the standard luminous and distinctive visiting police identification vests described in Appendix 4. Each visiting police officer should bring this vest when he/she travels abroad.

3.13. Accreditation

The police force of the organising country, in consultation with the football organisers, should ensure that the visiting police delegation has, when appropriate, stadium access and accreditation (seating is not required) to enable the delegation to carry out their tasks effectively. Stewards and other safety and security personnel should be made aware of this at their briefing(s) prior to the game.

3.14. Football Events in Countries without an NFIP

As stressed throughout this handbook and particularly in Chapter 1 above, where a football match or a tournament is played in a State with no NFIP, all information should be exchanged between the designated police contact point in the host country and the NFIP of the visiting country.

During the event, the designated police contact point of the host country should communicate with the NFIP of the visiting country/countries via the designated visiting police delegation liaison officer, if one has been appointed.

3.14a

It is strongly recommended that, at an early stage of the preparations, countries participating in the event should adopt a bilateral agreement with the host authorities setting out the arrangements for information exchange, deployment of visiting police delegations and other police cooperation matters in connection with the event. Such bilateral agreements can also include areas of governmental and judicial cooperation. A template for a bilateral agreement is set out in 12261/16. It includes the list of issues which should be considered and agreed between the two parties. The template is not a model agreement but rather an aid to bilateral negotiations.

3.14b

When preparing to assist with major tournaments, it is recommended that NFIPs should:

|

— |

share information about bilateral discussions/negotiations with the host authorities; |

|

— |

commence at an early stage and maintain dialogue with the host authorities, using international agencies, notably Interpol, to stress the key role of the European NFIP network; and |

|

— |

undertake coordinated visits to the relevant venue cities and stadia in the host country in order to clarify local arrangements and foster effective dialogue at national and local level. |

3.15. Role of Interpol and Europol

The NFIP network provides an appropriate and timely channel for the exchange of information regarding crowd management, public safety and public order, and associated risks. It is mandatory under European law for such information to be exchanged between host and visiting policing agencies through the respective NFIPs or the designated host police contact point and the visiting police liaison officers deployed in the host country during an event.

However, NFIPs can liaise with Interpol or Europol regarding any links between the activities of any supporter risk groups and links with serious and organised criminality or other non-football related criminality.

Moreover, Europol, Interpol and/or other agencies in the Justice and Home Affairs area, such as Frontex may, in accordance with their legal mandates, play an important role in supporting the competent authorities of countries hosting major international football tournaments. This may include providing various support services, relevant information and analysis, and threat assessments in respect of serious and organised crime and/or terrorism.

For example, during major tournaments:

|

— |

an Interpol major events support team may be deployed to support host law enforcement activity during a major tournament; |

|

— |

Europol may deploy its staff at the host police coordination centre to facilitate information exchange, to provide intelligence and analytical support in respect of organised crime, terrorism and other forms of serious crime; |

|

— |

host and Frontex personnel may have bilateral arrangements in place for cross-border operations. |

In such circumstances, the NFIPs of visiting countries, or heads of the visiting police delegations, should seek to ascertain at an early stage the exact functions of these agencies and liaise as appropriate on matters of mutual interest.

CHAPTER 4

4. Cooperation between the Police and the Organiser

Close cooperation between the police and stadium authorities/the match organiser (and other parties involved, including any private security companies and stewards operating in stadia) is crucial for the delivery of effective in-stadia safety and security arrangements.

The key partnership at a local level is between the police match commander and the individual appointed by the match organiser as being responsible for safety and crowd management within the stadium (commonly referred to as the stadium safety officer, though the term security officer is used in some countries).

The police commander and stadium safety officer should work together on a complementary basis, without prejudice to their respective responsibilities, competencies, and tasks. These may be set out in national legislation or stadium regulations or specified in a written agreement between the organiser and the police (often described as a statement of intent) specifying the role of the police (if any) in crucial crowd management functions. Such functions include: supporting safety personnel (stewards) in preventing and dealing with any public disorder or other criminality; activating the organiser's emergency procedures; and determining the circumstances in which the police should take control of all or part of the stadium in emergency and major incident scenarios, along with the procedure for doing so and for the eventual return of control to the organiser.

Close cooperation should also ensure that police views on a number of key in-stadia safety considerations are taken into account by the organiser. A number of important issues can be covered in this way, including: the use of CCTV for crowd management and evidence gathering purposes; shared or designated in-stadia communication arrangements; possible use of visiting stewards in a liaison capacity both in stadia and en route to and from a stadium; arrangements for a multi-agency control room, incorporating a police command post where appropriate.

Detailed guidance on this matter is set out in Council of Europe Standing Committee Consolidated Recommendation 1/2015/EC on an integrated approach to safety, security and service.

CHAPTER 5

5. Cooperation between Police and Justice and Prosecuting Agencies

The contents of this chapter should be seen in the context of wide variations in the structure and competencies of justice and prosecuting agencies in Member States.

There can be significant benefits from close cooperation between police and justice and prosecuting agencies in respect of both one-off matches and tournaments.

Whilst the host country has sovereignty and jurisdiction to deal with all alleged event-related offences committed in that country, the police and other authorities in Member States and EU competent bodies (e.g. Eurojust) should support the judicial and law enforcement authorities of the host country where possible and permissible.

All Member States should ensure that it is possible to deal quickly and appropriately with event-related offences.

The host police and other authorities should inform visiting police and supporters of relevant domestic legislation and/or criminal, civil or administrative procedures together with the maximum penalties for the most common football-related offences.

Existing multi-lateral agreements on mutual legal assistance (MLA) should be fully utilised, where appropriate, for all football matches with an international dimension. Additionally, a host country may agree bilateral arrangements with any other country for enhanced MLA before, during and after the event.

The NFIP of the supporting country/countries should inform the organising NFIP:

|

— |

of any legal possibilities (e.g. football banning orders/exit bans) they have to prevent risk supporters attending the event; |

|

— |

what measures can be taken by the visiting police delegation and/or any other competent agency (e.g. visiting liaison prosecutors) to gather evidence of any football-related offences committed by visiting supporters; |

|

— |

what offences committed in the host country could be prosecuted in the supporting country (upon the return of the offender). |

The host country may invite any other countries to send a liaison prosecutor/judge to be present during the event.

It is recommended that the host authority, in accordance with the national legislation on data protection, provides the visiting police delegation and/or competent agency (e.g. visiting liaison prosecutors) with information from judicial or court records and police or investigative reports, including arrest records, of their nationals.

Alternatively, a supporting country may agree to have a liaison prosecutor/judge available on call to travel to the host country at its request, or appoint a designated liaison prosecutor/judge for liaison with the designated host authority.

Within the scope of national legislation, the supporting NFIP(s) will attempt to answer promptly any requests for further information on arrested individuals, such as details of previous convictions, including football-related offences.

All costs related to liaison prosecutors/judges being sent to the host country should be subject to bi-lateral agreement.

The organising country should provide the necessary means of communication and other facilities for the visiting liaison prosecutors/judges.

CHAPTER 6

6. Cooperation between Police and Supporters

Police liaison with supporter groups at national and local level can have a major impact in minimising safety and security risks at football matches with an international dimension. This cooperation can however be undermined if there is any perception that supporter representatives are working on behalf of the police and, for example, sharing personal data.

Visiting police delegations and supporter representatives can help ensure that host police are aware of the character and culture of the visiting supporters. The host police should take this into account in their dynamic risk assessment.

Home supporters, local communities and visiting supporters should be provided with potentially important information and reassurance in respect of an event. Some of the main means of achieving this are: an effective media handling strategy; use of social media/internet sites; leaflets; and working closely with designated Supporter Liaison Officers (SLOs), supporter representatives and supporter focused initiatives (such as fan embassies).

Ongoing cooperation and communication between police and supporter groups can help provide a basis for a safe, secure and welcoming atmosphere for all supporters, and can provide a channel for relaying important information such as travel advice, access routes to the stadium, applicable legislation and behavioural tolerance levels.

The host and visiting police should, therefore, have a strategy in place for communicating with supporters (termed ‘dialogue’). Dialogue can either be a task for specialist (and trained) communication officers and/or front line (crowd control/public order) operational units trained in communication and conflict resolution techniques.

This approach has been shown to help promote self-policing amongst supporters and facilitate early and appropriate intervention when security problems or risks emerge.

Detailed guidance on this matter is contained in Council Resolution concerning a handbook with recommendations for preventing and managing violence and disturbances in connection with football matches with an international dimension, in which at least one Member State is involved, through the adoption of good practice in respect of police liaison with supporters (7).

CHAPTER 7

7. Communication and Media Strategy

7.1. Communication Strategy

An effective and transparent communication strategy is integral to a successful safety and security concept for football matches, tournaments and other sporting events with an international dimension.

Host country policing agencies should, therefore, work closely with governmental and local agencies, football authorities/organisers, the media and supporter groups in the preparation and delivery of a comprehensive multi-agency communication strategy.

An effective multi-agency media strategy is a crucial aspect of any communication strategy in terms of providing all parties, notably visiting supporters, with important information such as travel advice, access routes to the stadium, applicable legislation and behavioural tolerance levels.

The central aim should be to project a positive image of the event among home and visiting supporters, local communities, the general public and individuals participating in the safety and security operations. This can help generate a welcoming environment for all involved and make a major contribution towards minimising safety and security risks.

7.2. Media Strategy

The police (and wider multi-agency) media strategy should at least aim to:

|

— |

provide information in a proactive, open and transparent manner; |

|

— |

provide information on safety and security preparations in a reassuring and positive manner; |

|

— |

communicate the police's intention to facilitate the legitimate activities of supporters; |

|

— |

make clear what kinds of behaviour will not be tolerated by the police; |

|

— |

provide authoritative information on any incidents as quickly as possible. |

The police should work closely with governmental and local agencies, football authorities/organisers and, where appropriate, supporter groups in establishing and delivering a multi-agency media strategy which:

|

— |

proactively promotes a positive image of the event; |

|

— |

ensures responsibilities are clearly assigned among police and partner agencies in terms of who has the lead in communicating with the media on the various aspects of safety and security (and beyond); |

|

— |

provides common background and briefing information for all police and partner agency spokespersons (briefing material should be regularly updated to take account of recurring themes or questions and emerging risks or events); |

|

— |

ensures that factual information is released to the media and/or on the internet on a regular basis in the build up, during and after the event; |

|

— |

provides regular opportunities for press/media briefings; |

|

— |

takes account of the needs/interests of different categories of journalists/media. |

CHAPTER 8

8. Meetings of the EU Football Safety and Security Experts

It is highly recommended that during each EU Council Presidency, the Presidency holds a meeting of the experts group for major sports events and that the Presidency reports to the Law Enforcement Working Party on the result of that meeting and the ongoing work by the expert group.

It is further recommended that each Presidency hosts a meeting of the European Think Tank of football safety and security experts to:

|

— |

prepare relevant documentation for consideration by the experts group for major sports events; |

|

— |

prepare, and monitor the implementation of, the work programmes of the experts group for major sports; |

|

— |

monitor new trends/developments in supporter behaviour and associated risks; |

|

— |

monitor and facilitate the work of the European network of NFIPs; |

|

— |

share good practice in respect of international police cooperation and policing strategies and tactics for football events; |

|

— |

work in partnership with partner institutions in promoting the development of an integrated, multi-agency approach to football safety, security and service; and |

|

— |

any other issues of interest and relevance. |

CHAPTER 9

9. List of Relevant Documents on Safety and Security at Football Events

9.1. Documents previously adopted by the Council of the European Union

|

1. |

Council Recommendation of 30 November 1993 concerning the responsibility of organisers of sporting events (10550/93). |

|

2. |

Council Recommendation of 22 April 1996 on guidelines for preventing and restraining disorder connected with football matches, with an annexed standard format for the exchange of police intelligence on football hooligans (OJ C 131, 3.5.1996, p. 1). |

|

3. |

Joint action of 26 May 1997 with regard to cooperation on law and order and security (OJ L 147, 5.6.1997, p. 1). |

|

4. |

Council Resolution of 9 June 1997 on preventing and restraining football hooliganism through the exchange of experience, exclusion from stadiums and media policy (OJ C 193, 24.6.1997, p. 1). |

|

5. |

Council Resolution of 21 June 1999 concerning a handbook for international police cooperation and measures to prevent and control violence and disturbances in connection with international football matches (OJ C 196, 13.7.1999, p. 1). |

|

6. |

Council Resolution of 6 December 2001 concerning a handbook with recommendations for international police cooperation and measures to prevent and control violence and disturbances in connection with football matches with an international dimension, in which at least one Member State is involved (OJ C 22, 24.1.2002, p. 1). |

|

7. |

Council Decision of 25 April 2002 concerning security in connection with football matches with an international dimension (OJ L 121, 8.5.2002, p. 1). |

|

8. |

Council Resolution of 17 November 2003 on the use by Member States of bans on access to venues of football matches with an international dimension (OJ C 281, 22.11.2003, p. 1). |

|

9. |

Council Resolution of 4 December 2006 concerning a handbook with recommendations for international police cooperation and measures to prevent and control violence and disturbances in connection with football matches with an international dimension, in which at least one Member State is involved (OJ C 322, 29.12.2006, p. 1). |

|

10. |

Council Decision 2007/412/JHA of 12 June 2007 amending Decision 2002/348/JHA concerning security in connection with football matches with an international dimension (OJ L 155, 15.6.2007, p. 76). |

|

11. |

Council Resolution of 3 June 2010 amending a handbook with recommendations for international police cooperation and measures to prevent and control violence and disturbances in connection with football matches with an international dimension, in which at least one Member State is involved (OJ C 165, 24.6.2010, p. 1). |

9.2. Documents adopted by the Council of Europe

|

1. |

Council of Europe Convention on an integrated approach to safety, security and service at football matches and other sports events 2016 |

|

2. |

Recommendation (2015) 1 of the Standing Committee on Safety, Security and Service at Football Matches and other Sports Events (Consolidated Recommendation). |

(1) Risk analysis means developing a profile on national and club supporters, including risk-groups and how they relate to other supporters at home and abroad including local population groups and the circumstances which can increase potential risk (including interaction with police and stewards).

(2) The NFIP website is a highly secure website available for the exclusive use of NFIPs which contains information relating to football matches with an international dimension (e.g. club overview, pre and post match reports).

(3) Council Decision 2008/615/JHA of 23 June 2008 on the stepping up of cross-border cooperation, particularly in combating terrorism and cross-border crime (OJ L 210, 6.8.2008, p. 1).

(4) Council Decision 2008/616/JHA of 23 June 2008 on the implementation of Decision 2008/615/JHA on the stepping up of cross-border cooperation, particularly in combating terrorism and cross-border crime (OJ L 210, 6.8.2008, p. 12).

(5) A study undertaken in 2014 confirmed that average costs were low and represented a good investment of police budgetary resources:

|

— |

the average cost incurred in hosting a visiting delegation was reported to be EUR 282 per delegation, covering accommodation and internal travel costs; |

|

— |

the average cost incurred in deploying a police delegation was reported to be EUR 850 per delegation, covering international travel costs and officer expenses. |

(See also Council Resolution concerning the costs of hosting and deploying visiting police delegations in connection with football matches (and other sports events) with an international dimension, in which at least one Member State is involved, set out in 11908/16).

(6) See Articles 21 and 22 of the Prüm Decision on civil and criminal liability.

(7) 11907/16.

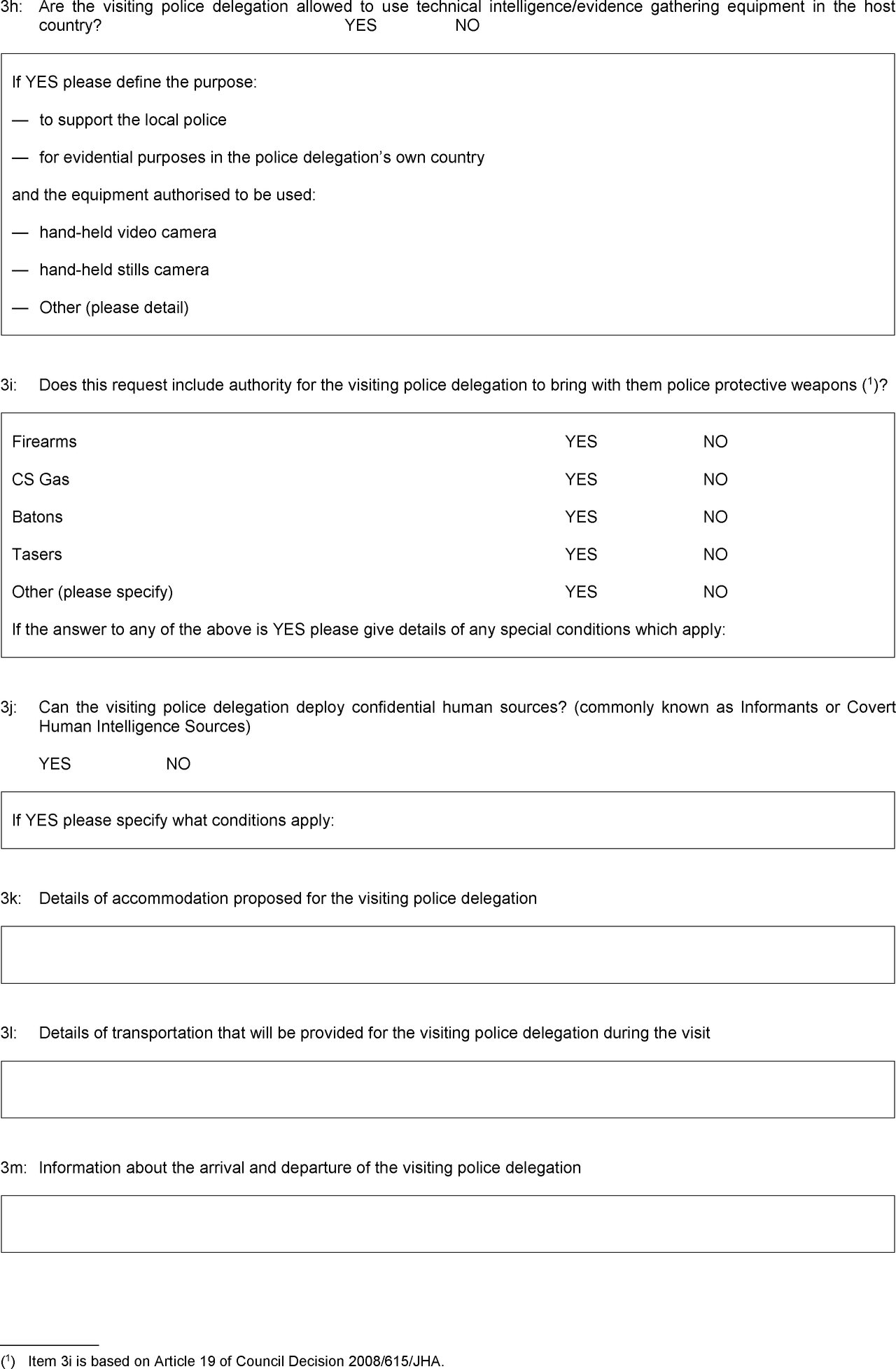

Appendix 1

PROTOCOL FOR THE DEPLOYMENT OF VISITING POLICE DELEGATIONS FOR FOOTBALL MATCHES WITH AN INTERNATIONAL DIMENSION

(For use when both the host and visiting States are party to the Prüm Treaty)

RESPONSE REGARDING VISITING POLICE DELEGATION

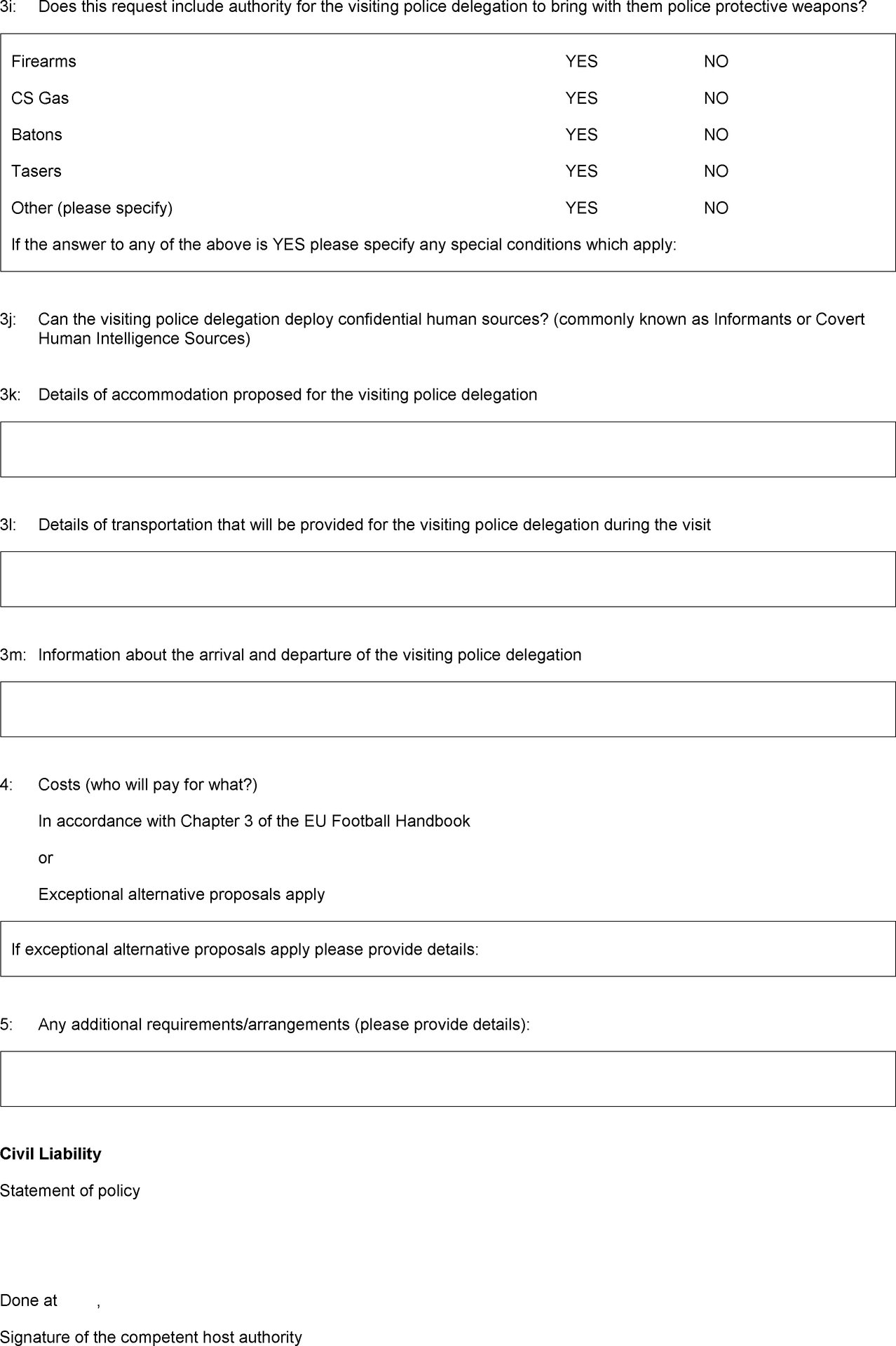

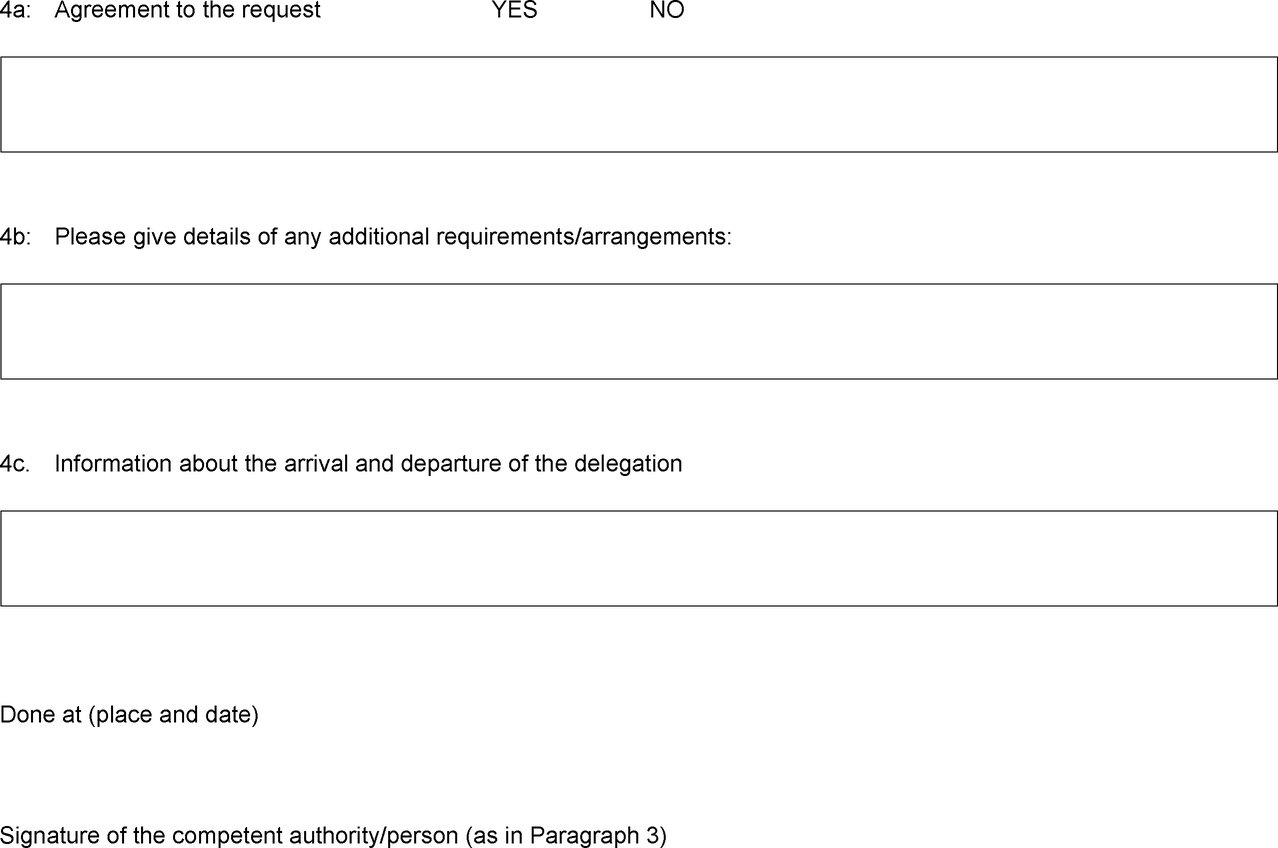

Appendix 2

PROTOCOL FOR THE DEPLOYMENT OF VISITING POLICE DELEGATIONS FOR FOOTBALL MATCHES WITH AN INTERNATIONAL DIMENSION

(Version to be used when either the organising or visiting State is not party to the Prüm Treaty)

RESPONSE REGARDING VISITING POLICE DELEGATION

Appendix 3

SPECIFICATIONS FOR AND SAMPLE OF POLICE IDENTIFICATION VESTS

This is a slip-on (over the head) sleeveless vest.

Colour: NATO BLUE.

Colour code: Pantone 279C.

Identification Markers:

Single word: POLICE (in English only) with a box border — to be positioned in the centre of the vest both front & back.

POLICE letters and border: Nato Blue background.

Both letters and the surrounding box to be luminous silver.

Box measurements = 25 cm × 9 cm.

|

POLICE letters: |

Width = 1,3 cm per letter. |

|

|

Height = 7,5 cm. |

Vest Front:

|

|

Left Breast (above POLICE box): National Flag 10 cm × 7 cm — embroidered/sewn on or in a plastic sleeve. |

|

|

Right Breast (above POLICE box): EU Symbol 8 cm × 8 cm. |

|

|

Below the POLICE box should be a luminous silver band across the front of the vest × 5 cm wide. |

Vest Rear:

|

|

National Flag above POLICE box: 10 cm × 7 cm. |

|

|

Vests should be able to be secured by means of either Velcro or popper type fasteners on both sides. |

Note: where possible, the specification should describe the material used for the vest, including whether or not it is water resistant, fire resistant, protective capability and other features.

Appendix 4

DYNAMIC RISK ASSESSMENT AND CROWD MANAGEMENT

Taking into account:

|

— |

a model for dynamic risk assessment in the context of international football matches (8241/05); |

|

— |

proposals concerning police tactical performance for public order management in connection with international football matches (8243/05); |

|

— |

the experience and lessons learned from Euro 2004 and subsequent tournaments; |

|

— |

evaluation of the policing philosophy, commonly known as the 3D approach (dialogue, de-escalation and determination), which was applied during Euro 2008 and subsequent tournaments; |

the following considerations should be applied in the assessment of risk to safety and security before, during and after the event.

Key Principles (in accordance with national law)

Current understanding of effective crowd management highlights the importance of:

|

— |

maintaining perceptions of appropriate policing among crowd participants; |

|

— |

avoiding the use of force against crowds as a whole when only a minority are posing a risk to public order; |

|

— |

a ‘low profile’ or ‘graded’ tactical approach where applicable to policing that enhances police capability for communication, dialogue and dynamic risk assessment. |

Facilitation

|

— |

The strategic approach should be preventative through low-impact intervention rather than repressive; |

|

— |

it is important that at every stage of an operation police strategy and tactics should take account of and facilitate the legitimate intentions of supporters, as far as these are peaceful (e.g. to celebrate their identity and culture, travel to and from the fixture in safety); |

|

— |

if it is necessary to impose limits on supporter behaviour, it is important to communicate with those supporters why police action has been taken and what alternative means the police are putting in place through which legitimate aims can be achieved. |

Balance

|

— |

During any crowd event the levels of risk to public order can change rapidly; |

|

— |

it is important that there is a proportionate balance between the style of police deployment and the level, sources and nature of risk at the point of police crowd interaction; |

|

— |

it is important that the policing is graded and capable of changing directly in response to the nature and levels of emerging and decreasing risk; |

|

— |

where balance is achieved, the majority of the crowd are more likely to perceive the actions of the police as appropriate and less likely to support and associate with those seeking confrontation; |

|

— |

therefore, to help decrease the likelihood and scale of incidents, it is critical that risk assessments are accurate and inform police tactics at all times. |

Differentiation

|

— |

The indiscriminate use of force can contribute to a widespread escalation in the levels of public disorder through its interaction with crowd dynamics; |

|

— |

differentiation between individual supporters who actually pose a danger and those who do not should therefore be built into every strategic and tactical decision relating to the management of crowds (i.e. training, planning, briefing and operational practice); |

|

— |

it is inappropriate to act against a whole crowd who happen to be present at a given location, unless there is evidence that they are uniformly seeking to provoke disorder. |

Dialogue

|

— |

It is important to communicate proactively with supporters. This is best achieved by police officers with good communication skills; |

|

— |

the focus is on creating a welcoming atmosphere and avoiding potential sources of conflict; |

|

— |

this approach can assist in the gathering of high quality information regarding supporter intentions, perspectives, concerns and sensitivities and any other information regarding potential risk; |

|

— |

it also allows the police to communicate concerns regarding supporter behaviour, risks they may face and solutions to any emerging difficulties. |

Models of good practice

Before the event

Risk assessment should take into account:

|

— |

the underlying culture of the supporter group to be policed (e.g. characteristic behaviour, motivations and intentions); |

|

— |

any factors likely to have an impact on risk, e.g. the activities of other groups (such as opposition supporters and/or local communities), sensitivities, history, and anything else of particular significance (dates, places, forms of action, symbols); |

|

— |

any circumstances likely to have an impact on the behaviour of, or risk posed by, those supporters or groups perceived to pose a risk to public order. |

Behavioural tolerance levels should be defined and priority given to communicating these to supporter organisations. Consideration should be given to encouraging supporters to gather in a safe/controlled environment (e.g. a fan zone).

Based upon this information and intelligence relating to the specific fixture it should be possible to predict and make a distinction between fixtures with normal risk and those posing an increased risk to public order.

It is important to clearly distinguish between risks for specific types of incidents, such as public order, public safety, criminality in relation to mass events, and terrorism.

Initial contact

Since the level of risk to public order is not fixed but highly dynamic it can increase and decrease rapidly in response to circumstances. The levels of risk should therefore be monitored and accurately assessed on an ongoing basis.

To achieve this:

|

— |

police should engage in high levels of positive interpersonal interaction with supporters (non-aggressive posture, smiling, deployed in pairs or in small groups in standard uniform, dispersed widely across and within crowds, accommodating requests for photographs, etc.); |

|

— |

where language is not a barrier, officers should try to communicate with supporters to gather information about their demeanour, intentions, concerns, sensibilities and any other issues relevant to their behaviour; |

|

— |

intervention units (i.e. ‘riot squads’ with protective equipment, vehicles, etc.) should be kept in discreet locations unless the situation determines that a more forceful intervention is required. |

This will help the host police gather information and inform command decisions regarding tactical deployment on the basis of continuous and ongoing risk assessment.

Increasing risk

Where circumstances posing a risk are identified it is important to:

|

— |

communicate to those posing the risk that their actions are likely to provoke police intervention; |

|

— |

where an incident involves visiting supporters, host police assessments should be validated by the visiting police delegation. |

Should the above measures not resolve the situation, then further use of force by the police may be required. The objective of police deployment at this stage is to minimise further risk. It is therefore essential that any action does not escalate tensions (e.g. indiscriminate use of force). Where any potential for an increase in risk is identified:

|

— |

it is vital that information about the persons creating the risk and its nature is communicated clearly to the intervention squads being deployed so that any use of force can be appropriately targeted; |

|

— |

those not posing any risk should be allowed to leave the vicinity and/or given some time to impose ‘self-policing’. |

De-escalation

|

— |

Once the incident(s) has been resolved policing levels should return to an appropriate level. |

After the event

|

— |

A through debrief should be conducted and any relevant information (e.g. the quality of information received before and during the event, the behaviour and management of supporters, police tactics and the enforcement of tolerance levels) should be recorded with the NFIP. |

Appendix 5

CATEGORISATION OF FOOTBALL SUPPORTERS

Note: In the planning of many policing security operations, the risk posed by individuals or groups is usually defined as ‘lower risk’ or ‘higher risk’ on the basis that no person can be guaranteed as posing ‘no risk’. (see ISO 31000 for a more detailed explanation).

However, since 2010, the terminology used in respect of the risk posed by supporters in connection with football matches with an international dimension is ‘risk’ and ‘non-risk’. This terminology is used and understood across the continent. This terminology is consistent with the rationale set out in the ISO guidance, in that it is recognised that it is not possible to accurately pre-determine the degree of possible risk which an individual may or may not pose in connection with a specific football event. This is evidenced by extensive European experience which demonstrates that a wide and variable range of factors are likely to influence the behaviour of an individual or group of individuals during an event.

Individuals categorised by the police as low or non risk fans can on occasions be prompted by negative circumstances to act in a violent, disorderly or anti-social manner. Conversely, the behaviour of individuals identified as risk fans can also be influenced by positive circumstances.

That is why an ongoing dynamic risk analysis process during an event is a pre-requisite of effective and proportionate football policing operations.

However, for planning purposes, it is necessary for the police to undertake a series of risk assessments. To assist police preparations and pre-event risk analyses, the categories of ‘risk’ and ‘non-risk’ should be applied. These categories should be accompanied by an explanation of the circumstances which may prompt ‘risk fans’ to react negatively during an event (see explanation and checklist below). Such explanations are a crucial aid to effective policing preparations.

Definition of a ‘Risk’ Supporter

A person, known or not, who, in certain circumstances, might pose a risk of public disorder or antisocial behaviour, whether planned or spontaneous, at, or in connection with, a football event (see Appendix 4 on dynamic risk assessment). The checklist below should be used to provide an indication of the circumstances which might negatively influence behaviour and generate a risk.

Definition of a ‘Non-Risk’ Supporter

A person, known or not, who can be regarded as usually posing a low risk, or no risk, of causing or contributing to violence or disorder, whether planned or spontaneous, at or in connection with a football event.

RISK SUPPORTER CHECKLIST

|

Risk Elements |

Supporting Comments |

|

Historical rivalry between clubs or fan groups |

|

|

Intelligence of potential violence |

|

|

Possible spontaneous disorder Possible racist or discriminatory behaviour |

|

|

Possible pitch invasion |

|

|

Alcohol-related problems |

|

|

Use of weapons |

|

|

Perception that policing tactics are inappropriate or disproportionate |

|

|

Possible terrorist threat |

|

|

Political extremism/use of prohibited banners |

|

|

Anticipated use of pyrotechnics |

|

|

Travelling supporters without tickets |

|

|

Threats to segregation (e.g. black market or counterfeit tickets) |

|

|

Sale/use of illegal drugs |

|

|

Other |

|