EUROPEAN COMMISSION

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Brussels,7.3.2018

SWD(2018) 206 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

Country Report Ireland 2018

x0009

Including an In-Depth Review on the prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances

Accompanying the document

COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK AND THE EUROGROUP

2018 European Semester: Assessment of progress on structural reforms, prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances, and results of in-depth reviews under Regulation (EU) No 1176/2011

{COM(2018) 120 final}

Contents

Executive summary

1.Economic situation and outlook

2.Progress with country-specific recommendations

3.Summary of the main findings from the Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure in-depth review

4.Reform priorities

4.1.Public finances and taxation

4.2.Financial sector and indebtedness

4.3.Labour market, education and social policies

4.4.Investment

4.5.Sectoral policies

Annex A Overview table

Annex B Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure Scoreboard

Standard tablesAnnex C

References

LIST OF Tables

Table 1.1:Key economic, financial and social indicators - Ireland

Table 2.1:Summary table on 2017 CSR Assessment

Table 3.1:MIP assessment matrix (*) — Ireland 2017

Table B.1:The MIP scoreboard for Ireland (AMR 2018)

Table C.1:Financial market indicators

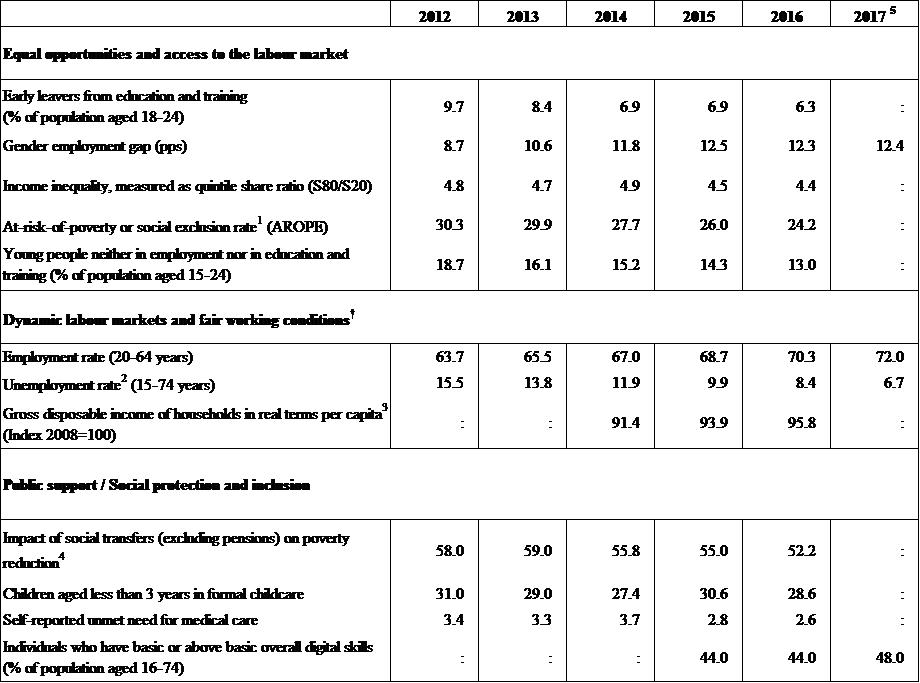

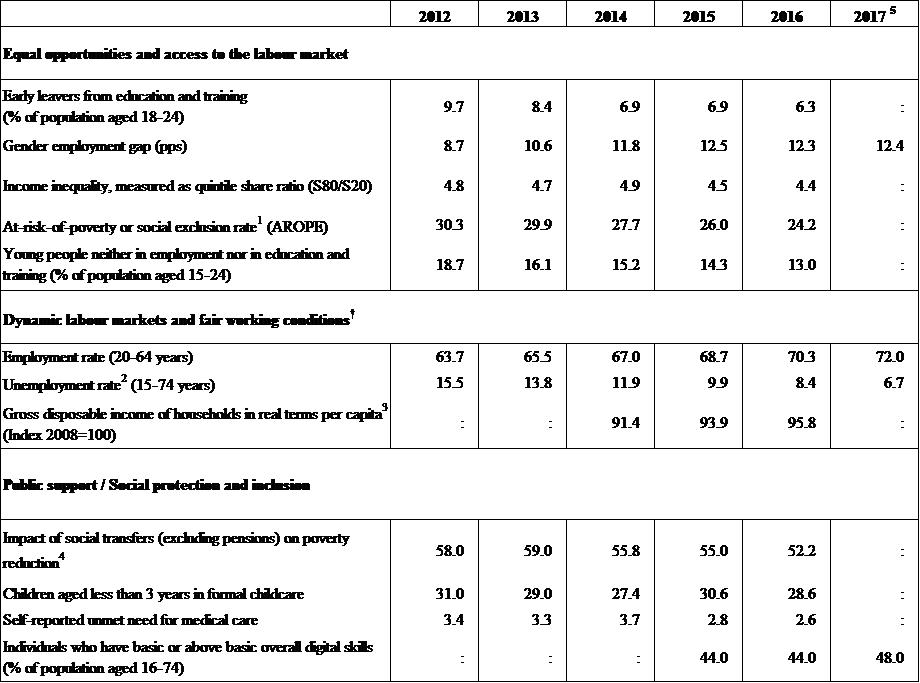

Table C.2:Headline Social Scoreboard indicators

Table C.3:Labour market and education indicators

Table C.4:Social inclusion and health indicators

Table C.5:Product market performance and policy indicators

Table C.6:Green growth

LIST OF Graphs

Graph 1.1:

GNI* vs GDP

Graph 1.2:

Modified Domestic Demand and Employment

Graph 1.3:

Employment developments

Graph 1.4:

Actual and predicted wage growth based on economic fundamentals

Graph 1.5:

Core investment and its components

Graph 2.1:

Level of implementation today of 2011-2017 CSRs

Graph 4.1.1:

Alternative debt indicators (EU countries, 2016)

Graph 4.1.2:

Bonds and EU-IMF programme loans repayment schedule (end-December 2017)

Graph 4.1.3:

Charges paid for the use of intellectual property

Graph 4.2.1:

Profitability of the main domestic banks

Graph 4.2.2:

NPL reduction by portfolio - domestic banks

Graph 4.2.3:

International investment position by institutional sector, non-IFSC

Graph 4.2.4:

Current account balance benchmark

Graph 4.2.5:

CA vs CA*

Graph 4.2.6:

Private debt evolution

Graph 4.2.7:

Composition of corporate debt

Graph 4.2.8:

Credit advanced to Irish companies

Graph 4.2.9:

Households’ financial assets

Graph 4.2.10:

New SME lending: volumes and interest rates

Graph 4.3.1:

Unemployment and inactivity as a percentage of the population aged 25-54

Graph 4.3.2:

Employment rates by level of education

Graph 4.3.3:

Change in employment by sector

Graph 4.3.4:

Main social indicators

Graph 4.3.5:

Progress towards reaching the benchmark of low achievers in reading, 2009-2015

Graph 4.4.1:

Total investment and main drivers

Graph 4.4.2:

Capital expenditure by the general government sector

Graph 4.4.3:

Labour productivity across sectors and firms, 2014

Graph 4.4.4:

Distribution of TFP values and means by quintile, indigenous companies vs multinationals, 2014

Graph 4.4.5:

Average growth rate of labour productivity

Graph 4.5.1:

House price increases

Graph 4.5.2:

Overvaluation gap with respect to price/income, price/rent and fundamental model valuation gaps

Graph 4.5.3:

Public support for business R&D as % of GDP, 2006 and 2014

LIST OF Boxes

Box 1.1: GNI* and other new indicators of Ireland's domestic economic activity

Box 2.1: Tangible results delivered through EU support to structural change in Ireland

Box 4.3.1: Monitoring performance in light of the European Pillar of Social Rights

Box 4.4.1: Investment challenges and reforms in Ireland

Box 4.5.1: Policy highlights: Technology Partnerships and Technology/Research Centres

Executive summary

The sustained strong economic growth in Ireland provides ample momentum to further increase the resilience of the public and private sectors. A continued reduction in government debt and deficit could create tailwinds against the possible materialization of external risks. Moreover, a rebalancing towards less volatile sources of government revenues could ensure the sustainability of public finances in the long run. Improvements in the balance sheets of households, companies and banks reflect continued deleveraging and progress in resolving nonperforming loans. Addressing these challenges would reduce the risk of a slowdown, should the external environment and financial conditions become less supportive. A tightening labour market, with rapidly subsiding unemployment, brings to the fore the importance of increases in labour market participation, while accumulating skills shortages further accentuate the need to continue upskilling efforts. Ensuring that the already broad-based growth reaches all parts of society, including addressing the remaining housing, social and infrastructural shortcomings, remains a government priority (

).

The Irish economy continues to grow at a solid pace. In the first three quarters of 2017, real GDP increased by 7.4 % year-on-year (y-o-y), well above the euro area average. It is projected to further increase by 4.4 % in 2018 and 3.1 % in 2019 (

). Uncertainties persist, primarily related to the outcome of the negotiations between the UK and the EU and potential changes to the international taxation environment. Ireland is one of the most affected Member States by the UK's decision to leave the EU, given the nature of the all-island economy, Ireland's geographical position and the volume of trade between the two countries.

Domestic economic activity continues to thrive. Modified domestic demand, a new measure of domestic activity that strips out some of the effects of multinationals, increased in 2016 and the first three quarters of 2017, driven by private consumption and construction investment. The strong, broad-based growth in employment also reflects the strength of domestic activity.

The labour market remains strong, with some outstanding challenges. In the third quarter of 2017, total employment increased by 2.9 % on an annual basis, and across almost all economic sectors. Fulltime employment increased by 7.1 % as people who had been working parttime are moving into full-time jobs. The unemployment rate fell to 6.7 % in 2017. In the third quarter of 2017, very longterm unemployment (over two years) stood at 28.9 % of all unemployment, somewhat above the EU average. Some challenges remain in relation to high inactivity rates and skills shortages in certain sectors. Some households also continue to experience poverty and social exclusion and the homelessness rate continues to increase.

The government has repeatedly intervened to tackle the undersupply of housing, but it will take time for the measures to have an effect. Against the backdrop of a limited housing stock, residential property price growth accelerated. Years of low investment following the economic bust are taking their toll on the availability of supporting infrastructure for residential sector construction (such as water and transport), constraining housing supply. Although prices did not seem overvalued in 2016, affordability is a concern.

The government deficit is moving closer to balance. The general government deficit is expected to decline further in the near future, although progress in making public finances more resilient has slowed down in recent years. Relying on highly volatile, highly pro-cyclical sources of revenue remains a risk.

Ireland has made some progress in addressing the 2017 country-specific recommendations (CSRs). With regard to the fiscal recommendations, it made some progress in 2017. The proceeds from the sale of government shares in state-owned banks have been used to reduce public debt and the National Asset Management Agency redeemed all of its government-guaranteed debt. As regards the recommendation to limit the scope and the number of tax expenditures and broaden the tax base, only a few of the measures taken have the potential to broaden the tax base. A new spending review signals progress in enhancing the quality of expenditure. Some progress has also been made in improving social infrastructure and delivering an integrated package of labour market activation policies. However, it remains difficult to access affordable, full-time, quality childcare. With regard to the lasting reduction of non-performing loans (NPLs), Ireland made some progress in 2017 as the stock of NPLs decreased. Insolvency procedures, in- and out-of-court arrears resolution avenues remain under-used. The credit register should become operational in 2018.

Regarding progress in reaching the national Europe 2020 strategy targets, Ireland is performing well on the employment rate and early school leaving targets. It needs to do more on investing in R&D, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, increasing the proportion of renewable energy, improving energy efficiency, reaching the national target for tertiary education and reducing poverty.

Ireland performs relatively well on most indicators of the Social Scoreboard supporting the European Pillar of Social Rights, while challenges remain. Ireland is tackling poverty and social exclusion and preventing early school leaving. Social protection systems do relatively well in reducing poverty and promoting social inclusion. Work-life balance measures are improving as take-up of childcare for children under three years has increased in recent years. Healthcare and homelessness show significant room for improvement. Despite its many information and communication technology (ICT) graduates, the proportion of the overall population having basic digital skills in Ireland remains low.

The main findings of the in-depth review contained in this report and the related policy challenges are as follows:

·Private debt levels continue to fall, improving the resilience of households and businesses. A large part of the stock of private debt in Ireland is attributed to multinational corporations with more modest linkages to the domestic economy. Domestic economic actors overall continue to reduce their debt bringing it broadly in line with fundamentals. Hence, the headline private debt levels somewhat overstate the severity of this imbalance. The growth in house prices increased the net worth of households and reduced the number of those in negative equity.

·Public debt continues to fall, but remains high. As a percentage of GDP it significantly declined to 72.8 % in 2016, on the back of strong nominal GDP growth. However, complementary indicators, including some which strip out the effect of multinationals, suggest that the burden of public debt remains significant by historical and international standards, exposing Ireland to economic shocks

·While Ireland's net international investment position remains very negative, risks to the external position of domestic sectors seem contained. The country’s negative net international investment position has improved somewhat after significantly deteriorating in 2015, but remains large. The nonfinancial corporate sector contributes the most to the negative balance, driven by the activities of a small number of very large multinationals with few implications for the external sustainability of the domestic sector. The risks associated with the external liabilities of these companies are mitigated by factors such as high profitability and offsetting overseas assets. Moreover, these liabilities are not linked to Irish investors. On the other hand, the net external position of the domestic sectors has improved.

·On the way to a sustained recovery of the financial sector, legacy issues still create constraints. Domestic banks have remained profitable and strengthened their capital ratios. They have also further reduced their NPLs, even though their stock remains considerable and provisioning coverage ratios fairly low. Their overall good performance allows for a more ambitious NPL reduction pace in particular through durable restructurings and write-offs. Long-term mortgage arrears (over two years past due) remain the biggest challenge. Insolvency procedures, in- and out-of-court options for arrears resolution remain little used. A fully functioning credit register, expected in 2018, will be crucial for assessing the debt servicing capacities of borrowers.

·Rapid house price increases are observed countrywide. Residential property prices rose by 11.6 % y-o-y to November 2017, continuing the upward trend of the previous years. Private sector rents have continued to increase, exceeding their pre-crisis peak. The macroprudential framework in place is expected to ensure that new credit is extended under prudent conditions, preventing any potential credit bubble. This is especially important given the current high demand for mortgages.

Other key structural issues analysed in this report, which point to particular challenges for Ireland’s economy, are the following:

·Broadening the tax base could help improve revenue stability in the face of economic fluctuations. In particular, taxes on corporate income as a proportion of total taxation continued to rise. In Ireland’s case such taxes are highly concentrated and prone to volatility.

·Debt overhang and uncertainty in some exporting sectors affect corporate credit demand. While some sectors are starting to borrow again, companies that export to the UK may be delaying some of their investment and borrowing decisions. Collateral and guarantee requirements, alongside interest rates above the EU average, could be curbing demand further.

·The strong labour market has had a positive impact on a number of social issues, but some challenges remain. Inactivity is still a concern, with a large proportion of the working age population remaining outside the labour force. The lack of access to affordable childcare services forces many, in particular women, into inactivity. The employment rate of people with disabilities is one of the lowest in the EU. Skills shortages are becoming increasingly apparent, most notably in ICT, financial services and engineering. Ireland has a relatively low level of the population with basic digital skills. Many people have yet to reap the benefits of the economic upturn.

·Some indicators suggest that Ireland’s tax rules are used by multinationals engaged in aggressive tax planning structures. Ireland has taken steps to amend some aspects of its tax system that may facilitate aggressive tax planning and is carrying out a consultation on further changes. However, the absence of some anti-abuse rules or the exemption from withholding taxes on dividend payments made by companies based in Ireland suggest that Ireland's corporate tax rules may still be used in tax avoidance structures.

·Addressing emerging infrastructure bottlenecks is essential for sustainable and balanced growth in the future. Combined with better spatial planning, improved infrastructure services, including for transport, energy and water, are critical enablers for an appropriate housing supply response, the enhancement of private investment and economic development. Finally, infrastructure investment as well as intensified efforts in the field of renewables will be essential for Ireland to succeed in its transition towards a low-carbon and environmentally resilient economy. The new Project Ireland 2040 framework proposes a series of measures to address the above-mentioned bottlenecks and promote a regionally balanced development model.

·A comparatively costly healthcare system, compounded by an ageing population, represent important challenges for the healthcare system. Demographic changes are projected to affect Ireland in the coming years, in particular the fiscal sustainability of its healthcare system. Multi-year budgeting and better expenditure control would support the much needed shift towards universal healthcare. Primary and community care services are not yet capable of alleviating the mounting pressure on capacity within hospital care.

·The productivity of domestic companies is lower, and growing at a slower pace, in comparison with the multinationals operating in Ireland. Positive spillovers from the multinationals appear when domestic companies are integrated with them in value chains. Spillovers from the multinationals could be greater if domestic companies invested more in R&D and innovation. Overall, Ireland is a strong innovator and continues to improve its position in international innovation rankings, but low public expenditure on R&D remains a cause for concern.

1.

Economic situation and outlook

GDP growth

The Irish economy continues to grow robustly. In the first three quarters of 2017, Ireland’s real GDP increased by 7.4 % year-on-year (y-o-y), well above the euro area average. GDP is estimated to further increase by 4.4 % in 2018 and 3.1 % in 2019. However, the headline figures remain volatile and heavily influenced by the activities of multinational enterprises in Ireland, especially in relation to contract manufacturing (

) and aircraft leasing.

|

Graph 1.1:GNI* vs GDP

|

|

|

|

Source: CSO

|

Domestic demand remains strong. Modified domestic demand (Box 1.1), a measure of domestic activity that strips out some of the distorting impact of multinationals, increased in 2016 and the first three quarters of 2017, supported by private consumption and construction investment. These factors are expected to further boost the underlying domestic economy, and are projected to expand at an average rate of 4 % over the next two years. The strong and broad-based growth in employment, in particular full-time employment, also reflects the strength of domestic economic activity (Graph 1.2).

|

Graph 1.2:Modified Domestic Demand and Employment

|

|

|

|

Source: CSO, European Commission

|

Output in the domestic economy is also increasing at a robust pace. In 2016, gross value added (GVA), output net of the inputs used for its production, increased by 5.3 % y-o-y in domestic sectors where the presence of foreignowned multinationals is not prevalent. GVA in the multinationals-dominated sectors increased by 4.9 %. A deceleration from the surge in 2015 was driven by the contraction in contract manufacturing. Industrial production data show that the output in domestic sectors declined by 0.7% y-o-y in the first 11 months of 2017. Over the same period, the output in sectors dominated by multinationals fell by 3.7%, also reflecting the slowdown in contract manufacturing from the previous year (Section 4.2.2).

External risks to the macro-economic outlook are tilted to the downside. They relate mostly to the outcome of the negotiations between the UK and the EU and changes to the international taxation environment.

|

Box 1.1: GNI* and other new indicators of Ireland's domestic economic activity

The Irish Central Statistical Office (CSO) published complementary adjusted measures of national indicators in an attempt to account for the effects of globalisation on measuring the Irish economy. In July 2016, the National Income and Expenditure Annual Results 2015 showed a massive surge in Irish GDP of more than 26%, due to relocations of a number of multinational companies' (entire) balance sheets to Ireland. These were dominated by intangible intellectual property (IP) assets, which added approximately EUR 300 billion to Ireland's capital stock. While there have always been difficulties with GDP in an Irish context, after the level shift in activity in 2015 it became broadly accepted that GDP and GNI do not provide a complete understanding of the Irish economy. The CSO set up the Economic Statistics Review Group (ESRG) to investigate alternative indicators of domestic economic activity. Based on its recommendations, in July 2017, the CSO published an adjusted indicator: the Modified Gross National Income* (GNI* - read as GNI "star"), an adjusted Balance of Payments (BoP) and additional cyclical indicators. Further metrics are to be developed in the near future.

Modified Gross National Income (GNI*) is an indicator designed to reflect aspects that distort the aggregate size of the domestic economic activity. Table 1 presents the compilation of the new GNI* measure. The transition from GDP to GNI has the largest quantitative impact. GNI* excludes the retained earnings of re-domiciled public limited companies (PLCs) because relocation, often motivated by tax considerations, may not be associated with substantive domestic economic activity. In addition, under the ESA2010 national accounting framework, intangible assets, including IP, are treated as non-financial assets subject to depreciation. The significant increase in 2015 investment therefore led to an increase in depreciation charged in Ireland on what is a foreign-owned portion of capital stock. Since the depreciation on the foreign-owned capital stock is borne by foreign investors, it should not affect a measure that is intended to capture the resources accruing to domestic residents. For this reason, GNI* also deducts this element, which accounts for approximately 70% of the gap between GNI and GNI*. The leased aircraft can be viewed as a physical asset for the host country. It involves depreciation charged in Ireland but ultimately borne by the (foreign) end user of the aircraft, with little or no impact on the actual domestic economy. This is why GNI* also subtracts the depreciation of leased aircraft. Furthermore, it is published only on an annual basis and in nominal terms. While GNI* is intended as an additional indicator to provide a more comprehensive picture of the domestic economy, GDP continues to be the standard international measure used.

Table 1: GDP and transition from GNI to GNI*

Source: CSO

Modified total domestic demand is defined as total domestic demand net of trade in aircraft by leasing companies and investment in intellectual property. The indicator also measures the domestic economy. It is designed to be largely unaffected by the activities of multinational companies and to be more closely related to employment growth. In order to derive this measure, the CSO compiles an indicator for modified gross domestic fixed capital formation (GFCF*) which aims to better indicating the physical capital used to produce domestic output. GFCF* then replaces GFCF in the calculation of modified total domestic demand.

Modified current account measure (CA*) adjusts for the activities linked to multinationals. It excludes from the current account balance (CA) the following: imports of R&D-related IP and aircraft for leasing, the depreciation of this foreignowned domestic capital and the factor income of re-domiciled companies. Some multinationals in Ireland purchase IP, or aircraft for leasing, from their parent company. In time, they repay the costs from the profit associated with the IP or aircraft for leasing. These import costs are therefore not a liability for Irish residents and should be excluded from the CA. The CA* also substracts the depreciation of capital assets sometimes held outside Ireland and owned by Irish resident foreign-owned companies (such as IP and aircraft leasing), which is borne by foreign investors. This is especially the case if the relocated capital is not used in combination with domestic labour but in combination with overseas workers through contract manufacturing arrangements. The income flows on portfolio debt/equity are recorded on a cash basis. This means that if a re-domiciled company opts to retain its net income, this is recorded as a direct investment inflow and added to the stock of portfolio equity liabilities. The corresponding outflow is only recorded when dividends are paid to the foreign shareholders, and the CA will then decline accordingly. Therefore, if the earnings are retained the CA (and GNI) will be inflated by the non-payment of the dividend. In order to discount for the timing effect of divided payouts, the CA* subtracts the net incomes of these re-domiciled companies, treating them as income outflows regardless of whether they are distributed as dividends or retained.

The new indicators will not be used as official instruments of economic surveillance, only as complementary where relevant. One of the purposes of economic surveillance is to ensure that the indicators are comparable across EU countries. However, the new indicators represent a specific reaction to some major concerns for Ireland at the moment and they can add value to the analysis of the Irish economy. Therefore, they will be used as complementary indicators where relevant and possible.

|

Labour market

The labour market continues to perform strongly. In the third quarter of 2017, employment increased across almost all economic sectors by an average of 2.9 % yo-y (Eurostat definition, age group 20-64). Fulltime employment increased by 7.1 %, exceeding the increase in total employment as part-time workers start working full-time (Graph 1.3). The unemployment rate fell to 6.7 % in 2017. With the improvements of the labour market, skills shortages have been reported in a number of sectors, in particular within information and communications technology.

|

Graph 1.3:Employment developments

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|

Wage growth resumed in 2014 reflecting the economic recovery, and remained moderate in 2016 and 2017. Nominal compensation per employee increased by 2 % in 2016, and is expected to have increased to 2.6 % in 2017 (based on estimates by Arpaia and Kiss, 2015). This is consistent with productivity growth, inflation and the fall in unemployment (see Graph 1.4). It is also consistent with a roughly constant percentage of wages in total income and slightly increasing unit labour costs. Moderate wage developments coupled with dynamic employment growth could indicate a persistent slack in the labour market.

|

Graph 1.4:Actual and predicted wage growth based on economic fundamentals

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission AMECO database and update of calculations by Arpaia and Kiss (2015).

|

Social developments

Ireland's social situation continues to improve. Absolute poverty levels and joblessness have dropped since 2012, but the proportion of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion remains high. This is mainly because there is a very high number of low-work-intensity households in Ireland. Homelessness has also increased in recent years, with the situation being exacerbated by housing shortages (Section 4.4.3).

Wealth inequality is decreasing from high levels as market prices of housing assets recover. The Gini coefficient used to measure inequality for net wealth was 75 in 2013, among the highest in the EU (

). However, this was driven partly by high levels of negative housing equity – meaning the value of the mortgage exceeded the market value of the housing asset. When households in negative equity are excluded, the Gini coefficient falls to 65, which is in line with the euro area average. The recovery in the value of housing assets in recent years has led to a reduction in negative equity (see Section 4.2.3), and consequently to a reduction in wealth inequality.

Inflation

Consumer price inflation (HICP) remains fairly muted. Inflation rose only marginally in 2017 by 0.3 %. The upward pressure came from increasing energy prices and services. However, currency depreciation in the UK, from which Ireland imports approximately 25% of all goods, has contributed to the persistently negative price inflation of goods, offsetting increases in the prices of services. The negative price impetus coming from the goods side is expected to continue in the short term. Prices for services and residential rents are expected to remain the main positive driving force behind inflation in the next two years.

Competitiveness

External competitiveness appears to have deteriorated slightly because of exchange rate fluctuations. The depreciation of sterling in relation to the euro, contributed to the deterioration in Ireland’s competitiveness in 2016. This was partly offset by weak consumer price inflation.

External position

The activities of multinationals have a major impact on Ireland’s trade and external sector statistics. Contract manufacturing weighed on exports figures in 2017 (

), even though it played a major positive role in Q3-2017. Overall, in the first three quarters of 2017, total exports increased by 5.1 % y-o-y, mostly driven by exports of services. Total imports declined by 5.8 % yoy held back by extremely volatile imports of intellectual property services. As a result, a highly positive net external trade contributed significantly to GDP growth in the first three quarters of 2017. Under the technical assumption of no disruption to trading relations between the EU and the UK, exports are projected to increase in line with global trade. Imports are predicted to gather momentum on the back of strong consumer demand, leading to a moderation of the positive impact of net exports on GDP growth.

The risks to the external position of domestic sectors are smaller than the headline figures suggest. The headline net international investment position (NIIP) deteriorated markedly in 2015. However, this is primarily related to the position of non-financial corporations, a sector dominated by multinationals with limited links to domestic activity. By contrast, the international investment position of domestic sectors, such as the Central Bank, domestic commercial banks and general government, improved. Distinguishing between domestic and multinational companies in the non-financial sector is necessary to better interpret these headline figures. The marked deterioration in the external position of multinationals, in particular in 2015, considered as a whole, does not appear to threaten the domestic economy (Section 4.2.2). However, the high negative NIIP warrants continuous monitoring.

Financial sector

The financial sector remains stable, but legacy assets remain a challenge. The capital buffers of the Irish banks have improved and their profitability levels are being maintained (Section 4.2.1). However, legacy assets, overall subdued credit demand and the interest rate environment are preventing them from significantly improving their profitability. Their stock of non-performing loans is declining but remains high, and their provisioning levels are below the EU average. In particular, the resolution of long-term mortgage arrears is progressing at a sub-optimal pace. External uncertainty is an additional concern for parts of the financial sector with links to the UK.

While the deleveraging of the domestic private sector is ongoing, credit demand is recovering for certain categories of loans. This is the case for consumer and mortgage loans, as well as for certain corporate activities. In 2017, new mortgage lending increased by 29 % on an annual basis. House price dynamics have also increased the average value of mortgages drawdown. A stronger recovery of demand for mortgages could, however, be curbed by housing supply limitations. The concentration of the banking sector and legacy assets have resulted in interest rates somewhat above the euro area averages. Corporate loans account for over 40 % of domestic banks’ new lending, but net lending remains negative as SMEs continue to deleverage (Section 4.2.5). State-supported credit measures are being reshaped to better address companies’ needs, in particular those of exporters to the UK.

Investment and housing market

Headline investment figures remain very volatile and should be interpreted with caution. Much of the surge in investment in 2016 (61 % y-o-y), attributable to intangible assets, was related to intellectual property services, with no impact on GDP because these services are imported. Total investment (gross fixed capital formation) in the Irish economy declined by 15.6% y-o-y in the first three quarters of 2017, but the quarterly profiles have been extremely volatile. Investment in aircraft has also contributed to the swings in total investment.

Evidence suggests that core domestic investment continues to gain momentum. In particular, investment in residential property in the first three quarters of 2017 increased by 14.9 %, supported by government policies (Graph 1.5). The recent dip in core machinery and equipment investment may be a sign that investors are reacting to external uncertainties (DBEI, 2017). The European Investment Bank confirms a deteriorating outlook for investment by companies, due largely to global uncertainties (EIB 2017).

|

Graph 1.5:Core investment and its components

|

|

|

|

Source: CSO

|

Public investment is recovering. In its Mid-term Review of the Capital Investment Plan, the government announced an additional EUR 6 billion for public investment over the period 2018-2021, on top of the EUR 42 billion allocated in the initial 2015 Plan. Capital expenditure is now expected to reach 2.5 % of GDP in 2021. In 2018, the government plans to publish a new 10-year National Investment Plan for the period 2018-2027.

Residential property price growth has accelerated recently. In terms of volume, residential building and construction output increased by 37.7 % y-o-y in the third quarter of 2017, albeit from a very low base. Based on current estimates (

), market participants expect annual house completions in the order of 23 000 units in 2018. The number of house completions seems unlikely to reach the level required, estimated in the range of 23 000 (rising to 32 000 by 2024) (Duffy et al, 2016) to 50 000 (Lynons, 2017) new homes per year. The overall stock of residential properties listed for rent has fallen. All these factors are contributing to rising prices and rents (Section 4.5.1). House prices are 71.6 % higher than their through in 2013 and the price increases accelerated in 2017, putting pressure on affordability.

Lasting housing shortages are being addressed, but it will take time for the measures to have an effect. Many companies consider the housing infrastructure in their region inadequate. The slow growth in total housing stock is a direct consequence of the crisis and the breakdown in construction production capacity, as well as bottlenecks in supporting infrastructure. Housing pressures are most chronic in Dublin. Supply-side actions under the government’s five-year Rebuilding Ireland Action Plan include targeted enabling infrastructure provision to open up strategic residential sites, mainly in the cities, activation of state-owned sites as well as fast-track planning procedures to speed up decision-making. The new National Planning Framework could facilitate a more stable housing market by enabling a coherent spatial distribution of housing and infrastructure.

Public finances

The government deficit is moving closer to balance. The general government deficit is expected to have reached 0.4 % of GDP in 2017, an improvement of 0.3 pps compared to the previous year’s deficit. Taking into account the package of measures announced in the 2018 Draft Budgetary Plan, the deficit is still expected to fall further to 0.2 % in 2018 due to the resilient outlook for GDP and domestic demand. However, risks to the budgetary projections are on the downside. They relate mainly to macroeconomic uncertainties and the volatility of some sources of government revenues.

Relying on volatile, highly pro-cyclical sources of revenue remains a risk. The majority of revenue-raising measures introduced in Budget 2018 are biased towards uncertain tax bases. In particular, the increase in the stamp duty rate on commercial property purchases, although an additional yield, increases reliance on transaction-based taxes. In the recent past, these have proved to be an unstable and highly pro-cyclical source of government revenue. The reduction in capital allowances for intangible assets may help smoothen corporate tax revenue over time. However, it will not impact the overall tax receipts.

Public debt, as a percentage of GDP, continues to fall, but remains elevated. Gross general government debt is expected to have declined to 69.6 % of GDP in 2017, from 72.8 % of GDP in 2016, and to further decline to 69.1 % in 2018 and 67.2 % of GDP in 2019. This is contingent on continued robust GDP growth and the realisation of primary budget surpluses. However, complementary indicators, including debt-to-GNI* (Box 1.1), show that the burden of public debt remains considerable (Section 4.1.1). Favourable market conditions and the long-term maturity of the debt stock are expected to smooth future refinancing operations.

|

|

|

Table 1.1:Key economic, financial and social indicators - Ireland

|

|

|

|

Source: Eurostat and ECB as of 30 Jan 2018, where available; European Commission for forecast figures (Winter forecast 2018 for real GDP and HICP, Autumn forecast 2017 otherwise)

|

|

|

2.

Progress with country-specific recommendations

Progress with the implementation of the recommendations addressed to Ireland in 2017 (

) has to be seen in a longer term perspective since the introduction of the European Semester in 2011. Looking at the multi-annual assessment of the implementation of the CSRs since these were first adopted, 80 % of all the CSRs addressed to Ireland have recorded at least 'some progress'. 20 % of these CSRs recorded 'limited' or 'no progress' (see Figure 2.1). Labour market policies such as job creation and life-long learning have been among the most successful.

|

Graph 2.1:Level of implementation today of 2011-2017 CSRs

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|

Efforts with regard to the structural part of the fiscal country-specific recommendation (CSR) are mixed. Ireland has achieved considerable success in stabilising its public finances and has been able to ensure a sustainable correction of the excessive deficit. The government deficit has improved from 3.6 % in 2014 to 0.7 % in 2016. The structural balance has also improved, but more slowly in recent years. Limited progress has been made in broadening the tax base. Expenditure ceilings now take into account demographic pressures and carry-over effects, but their repeated changes remain a concern for budgetary execution. Measures have been taken to increase the cost-effectiveness of the healthcare system but many of them are still in their infancy. Public investment started to increase in 2014 and the government has outlined some of its investment priorities until 2021. The insufficient supply of housing, as well as related deficiencies in infrastructure and planning, have become more pressing for both economic and social reasons. The government is adopting measures to support supply, including increasing the provision of social housing units and the vacant site levy.

The labour market recovery has also been supported by CSR implementation since 2014. Ireland has implemented a range of active labour market reforms over recent years. Support programmes for jobseekers have now been fully rolled out. Intreo (Irish Public Employment Service) centres offering activation and social protection measures have been set up. Reforms of further education and training, aimed at promoting re-skilling and up-skilling, have also made continuous progress. Ireland has also achieved some success in addressing child poverty by, for example, improving inclusion programmes. The Housing Assistance Programme and the Back to Work Family Dividend have reduced disincentives to return to work. It remains difficult to access affordable, full-time, quality childcare, although the situation did improve in 2017. The policy measures undertaken are in line with the EAR 3 that emphasizes the promotion of quality job creation, equal opportunities and access to labour market, fair working conditions, as well as social protection and inclusion.

Progress in implementing the financial sector CSR has been made since 2014, but the high stock of non-performing loans (NPLs) remains a burden. The stock of NPLs has decreased considerably but their ratio to total gross loans remains among the highest in the EU and the pace of reduction has slowed down somewhat. Long-term impaired mortgages have proven to be the most difficult to restructure, with most of these cases still at some stage of the lengthy legal process. The supervisor is closely monitoring the banks’ non-performing loan reduction strategies and their restructuring practices. Several policy measures have been introduced to support debtors in distress and increase the number of personal insolvency arrangements, but take-up of these measures remains limited overall. The central credit register is supposed to be ready for use in early 2018.

|

|

|

Table 2.1:Summary table on 2017 CSR Assessment

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|

|

|

Ireland has made some (

) progress in addressing the 2017 CSRs. Since the CSR adoption in July 2017, some windfall gains have been used to accelerate the reduction of public debt, but the country has taken measures with mixed impact on the tax base. This means that some progress was made on CSR 1. With regard to CSR 2, which is reflective of both EAR 2 and EAR 3, a new spending review process has improved the quality of expenditure. Improvements have also been made in social infrastructure and an integrated package of labour market activation policies has been proposed. However, access to quality childcare and the labour market participation of particular groups, many requiring upskilling support, remain problematic. Ireland has also made some progress on CSR 3. The stock of NPLs has continued to fall but remains high, while the long-term sustainability and resilience of restructuring solutions has yet to be proven. As noted in the EAR 4, a tangible acceleration of NPL resolution contributes to overall risk reduction.

|

Box 2.1: Tangible results delivered through EU support to structural change in Ireland

Ireland is a beneficiary of European Structural and Investment Funds (ESI Funds) support and can receive up to EUR 3.4 billion until 2020. This represents around 7% of public investment

I

annually over the period 2014-2018. By 31 December 2017, an estimated EUR 2.6 billion (79 % of the total) was allocated to projects on the ground. This has paved the way for over 31 000 enterprises (50% of the target) to have received support and/or management and marketing training, for over 850 enterprises engaged with co-funding strategic research centres and over 550 new researchers employed in supported entities; over 830 new and 20 000 existing enterprises are supported, including for the creation of over 2 700 additional jobs and 36 000 trained persons for SMEs; over 400 000 people benefit from training and education programmes; and 500 farm partnerships have been created, leading to generational renewal in agriculture.

ESI Funds help address structural policy challenges and implement country-specific recommendations. These include prioritising public investment in innovation in particular in support of SMEs, incentivising employment and increasing the flexibility of the labour market and labour market access. The ESI Funds also support the implementation of CSRs by helping strengthen activation measures, innovation and research. ESI Funds address wider structural obstacles to growth and competitiveness, including upskilling people within and outside the labour force in order to meet future skill needs, enlarging the coverage of superfast broadband; incentivising innovation and private investments; and supporting and training workers of several thousand Irish enterprises. High take-up levels by end users of rolled-out superfast broadband throughout the country will enable e-Commerce and e-Government by SMEs and inhabitants, new competitiveness skills in thousands of SMEs after support and training, and hundreds of more RTDI results to come from research institute-company cooperation to make Irish-owned firms more competitive to produce products and services in demand in global markets. ESI Funds are also mobilised to improve the digital skills of the working age population which is highlighted as a challenge for Ireland in the Social Scoreboard supporting the European Pillar of Social Rights.

Ireland is advancing in the take up of the European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI). As at December 2017, the overall financing volume of operations approved under the EFSI amounted to EUR 982 million, which is expected to trigger total private and public investment of EUR 3.9 billion. More specifically, 14 projects involving Ireland have been approved so far under the Infrastructure and Innovation Window (including 7 multi-country projects), amounting to EUR 733 million in EIB financing under the EFSI. This is expected to trigger EUR 2.6 billion in investments. Under the SME Window, six agreements with financial intermediaries have been approved so far. European Investment Fund financing enabled by the EFSI amounts to EUR 249 million, which is expected to mobilise approximatively EUR 1.3 billion in total investment. Over 13 600 smaller companies or start-ups will benefit from this support. Energy ranks first in terms of operations and volume approved, followed by SMEs, social and environment.

Funding under Horizon 2020, the Connecting Europe Facility and other directly managed EU funds is additional to the ESI Funds. By the end of 2017, Ireland has signed agreements for EUR 96 million for projects under the Connecting Europe Facility.

https://cohesiondata.ec.europa.eu/countries/IE

|

ESI Funds are important in addressing key challenges to inclusive growth and convergence in Ireland, notably by prioritising public investment in innovation in support of SMEs throughout the country, supporting institute-company cooperation to make Irish-owned firms more competitive to produce products and services in demand in global markets and incentivising innovation and private investments. ESI Funds are also instrumental for upskilling the labour force in order to meet future skill needs, increasing the flexibility of the labour market and labour market access.

3.

Summary of the main findings from the MACROECONOMIC IMBALANCE PROCEDURE in-depth review

The in-depth review for the Irish economy is presented in this report. In spring 2017, Ireland was identified as having macroeconomic imbalances, in particular relating to the high levels of private and public debt, the negative net external liabilities, the high stock of nonperforming loans and the rapidly rising property prices. The 2018 Alert Mechanism Report concluded that an in-depth review should be undertaken for Ireland to assess developments relating to identified imbalances. Analyses relevant for the in-depth review can be found in the following sections: public debt in Section 4.1.1, financial sector imbalances in Section 4.2.1, external imbalances in Section 4.2.2, private indebtedness in Section 4.2.3, and the property market in Section 4.5.1 (

).

3.1 Imbalances and their gravity

While private sector debt remains a vulnerability, the underlying flows signal strong continued deleveraging. A large part of the stock of private debt is attributable to multinational corporations with fewer connections to the domestic financial system and the domestic economy as such. There is continued evidence that domestic economic actors are still deleveraging in general, with some credit recovery in specific categories such as larger corporate and mortgage loans. The rise in housing prices increased the net worth of households and reduced the number of those in negative equity, but certain cohorts of borrowers remain particularly vulnerable.

Irish public indebtedness has decreased in recent years, while remaining elevated. As a proportion of GDP it has significantly declined, to 72.8 % in 2016, on the back of strong GDP growth. However, in Ireland’s case, the GDP figure overstates the actual size of the domestic economy. Measured as a proportion of GNI*, public debt amounted to 106 % in 2016. Although policy measures are being taken to make public finances more resilient, high public debt makes Ireland vulnerable to economic shocks.

The stock of NPLs decreased steadily in the year to June 2017, albeit more slowly than before. The aggregate NPL ratio for domestic banks was 14.4 % at the end of June 2017, down from 17.2 % in the previous year. The reduction in the stock of NPLs is the result of a combination of restructuring activities and portfolio sales, with varying degrees of success among individual banks. Long-term arrears continue to be a challenge, accounting for more than half of total mortgage NPLs and more than a third of total NPLs.

The country’s very negative net international investment position (NIIP) is improving. After significantly deteriorating in 2015 to -244 % of GDP, it recovered to 170 % in the third quarter of 2017. While the risks to the external position of domestic sectors seem contained, it is difficult to assess them fully.

Persistent supply shortages, coupled with increasing demand, continue to fuel property price increases. After two years of already strong increase, real house prices grew by 6.6 % in 2016 and continued to increase in 2017. This is a trend observed countrywide. House prices do not yet seem to be overvalued, but affordability may become a concern. Supply shortages remain the prime driver of the increase in house prices and rents. While supply is forecast to fall short of demand for some time, construction activity is gaining momentum. Starting from a low base, housing completions are estimated to have picked up by 42.3 % y-o-y in November 2017.

3.2 Evolution, prospects and policy responses

Domestic private sector deleveraging could be reaching a turning point for some categories of borrowers. While debt reduction is overall expected to continue, some firms are seeking credit again. Household debt also stopped contracting in 2017. However, credit expansion for both of these categories is limited by current housing supply shortages as well as heightened external uncertainty for some businesses.

Some measures have been introduced to accelerate the reduction of public debt. The 2018 Draft Budgetary Plan estimates gross debt to have fallen to 70.1 % of GDP in 2017 and to reach 69.0 % in 2018, contingent on continued strong GDP growth and the realisation of primary budget surpluses. The government has also used some proceeds, notably income from the sale of shares in state-owned banks, to accelerate debt reduction.

Insolvency procedures, incourt and outofcourt arrears resolution avenues remain under-used. The number of personal insolvency applications has increased since the Abhaile aidand-advice scheme was set up. However, there has been an increase in creditors’ rejections of the proposed insolvency arrangements, which transfers the cases to court, reducing the number of arrangements concluded. Collateral repossessions are still quite rare. The credit register should become fully operational in 2018.

The external position of the domestic sectors has improved. As banks restored their access to market funding, the NIIP for the domestic banking sector turned positive in 2016 and further increased in 2017. This in turn improved the Central Bank’s net external position, which stood at 6.5 % of GDP in the second quarter of 2017, a 5.5 pps annual improvement. The general government position remains negative but is improving. Overall, the predominantly negative level of its NIIP appears to be driven by the activities of multinationals in Ireland, with few implications for the sustainability of the domestic economy (Section 4.2.2).

The government has repeatedly intervened in the residential property market to help boost supply, but it will take time for the measures to have an effect. Building on Rebuilding Ireland – Action Plan for Housing and Homelessness (see Country Report 2017), the 2018 Budget envisages a number of additional measures aimed at addressing the housing shortage, including social housing and changes to the vacant site levy. A new National Planning Framework, intended to replace the 2002 National Spatial Strategy, could facilitate a more stable housing market by enabling a coherent spatial distribution of housing and infrastructure. Other measures include speeding up the planning permission process, making land in state/semi-state ownership available for residential development and financing resources for commercial investment in housing. The government published draft guidelines including measures reducing some restrictions on apartment building, to make it more attractive and affordable. The 2017 review of mortgage-related measures left the existing macroprudential framework largely in place.

3.3 Overall assessment

The levels of external, public and private debt and the share of NPLs are a source of vulnerability for the economy. After declining in 2016, household debt remained broadly unchanged in 2017 against the background of a recovery in credit demand, while most domestic companies continued reducing their debt. Public debt is on a firm downward trajectory and the deficit is projected to move closer to balance. The level of NPLs is declining and the banks’ capital positions have improved, which makes them well placed to further intensify NPL restructuring efforts. The country’s very negative NIIP is by and large due to the operations of some multinational companies in 2015 and the negative net position of the International Finance Services Centre (IFSC) (

), with limited exposure to the domestic sector, and therefore to its external sustainability. Property prices continued to increase over the course of 2017 but to date there is no significant evidence of overvaluation. Unlike in the pre-crisis period, bank credit is not driving current price developments. Comprehensive policy measures have been taken to address these vulnerabilities. They include reducing government debt by using windfall gains and measures to reduce the high stock of NPLs. The government has repeatedly intervened to tackle the undersupply of housing, but it will take time for the measures to have an effect. Macroprudential rules have also been put in place to ensure the resilience of households and banks by preventing unsustainable credit growth. High uncertainty surrounds the final outcome of the negotiations between the UK and the EU. Possible changes to international tax and trade policies could also be a source of asymmetric shock.

|

|

|

Table 3.1:MIP assessment matrix (*) — Ireland 2017

|

|

|

|

|

|

(Continued on the next page)

|

|

Table (continued)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|

4.

Reform priorities

4.1.

Public finances and taxation

4.1.1.Fiscal policy*(public deficit and debt developments)

Irish public debt remains elevated. In nominal terms, it peaked at EUR 215 billion (or 120 % of GDP) at the end of 2013, a five-fold increase from what it was shortly before the crisis. Since then, Irish public debt as a proportion of GDP has significantly declined, reaching 72.8 % in 2016 (EUR 201 billion), on the back of strong GDP growth. However, when assessed using a range of other metrics, including debt-to-GNI* (see Box 1.1), Ireland’s stock of public debt remains high by historical standards and by comparison with other EU countries (Graph 4.1.1).

In spite of its high debt levels, the country’s financing situation remains comfortable. Government bond yields have fallen sharply since the end of 2013 and remain low by historical standards. This reflects Ireland’s continuing strong economic and fiscal performance, as well as the ongoing ECB bond purchases under its quantitative easing programme. Almost EUR 15.8 billion were raised in 2017 via benchmark bond sales. This is somewhat in excess of the government’s initial plans, with the additional issuance linked to the early repayment of EUR 5.5 billion in EU-IMF programme loans.

Public debt is largely long-term, at a fixed rate. At the end of 2016, it amounted to EUR 201 billion, 89.7 % of which had a maturity of more than one year. Over half of the medium- and long-term debt — around EUR 102 billion — consisted of fixed rate treasury and amortising bonds while EUR 19.5 billion were floating rate notes. After the early loan repayment in late 2017, around 26 % of long-term marketable and official debt represented official loans from the EU-IMF programme partners. The combination of currently very favourable market conditions and sensible debt management operations has contributed to the decline in the effective interest rate. It was estimated at around 3.1 % in 2016, 0.3 pps. lower than in 2015, and it is projected to further decline to 2.8 % in 2018.

|

Graph 4.1.1:Alternative debt indicators (EU countries, 2016)

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission and CSO

|

Despite the average long maturities, an amortisation hump is expected in the forthcoming years. The weighted average maturity of Irish public debt, above 10 years, is one of the longest in the EU. However, there will be a noticeable amortisation hump of bonds and programme loans, amounting to an average annual financing need of around 6 % of GDP, between 2019 and 2020. The redemption profile of European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism (EFSM) loans currently extends until 2042, with the next principal repayment due in 2018. However, the 2018 EFSM maturities are expected to be refinanced, owing to the maturity extensions granted in 2013. In this regard, early loan repayment is also expected to improve debt sustainability by locking in low interest rates and longer maturities.

|

Graph 4.1.2:Bonds and EU-IMF programme loans repayment schedule (end-December 2017)

|

|

|

|

Source: National Treasury Management Agency

|

The decision to repay, early and in full, some outstanding loans is expected to further reduce the interest burden. In December 2017 (

), the Irish authorities repaid the outstanding IMF loans, together with the bilateral loans from Denmark and Sweden, early and in full. The intention was to make use of the currently favourable market conditions and the healthy cash position (

) to improve Ireland’s debt sustainability. According to the National Treasury Management Agency (NTMA) these early repayments are expected to generate interest savings of around EUR 150 million over the remaining life of the loans, while smoothening and extending the debt maturity profile.

Debt sustainability has improved. A debt sustainability analysis by the Commission (

) based on the 2017 Autumn Economic Forecast, projects that, in a baseline no-policy-change scenario, Ireland's public debt will decrease by about 21.7 % of GDP between 2017 and 2028, to around 48.3 % of GDP. The analysis also shows that adverse shocks to real GDP growth — of a magnitude reflecting the country’s historical variability of output (

) — would increase the public debt-to-GDP ratio by 19.2 pps. by 2028 compared to the baseline scenario, to about 67.5%.

Government contingent liabilities are waning. State guarantees, most of which are linked to the support granted to financial institutions, fell sharply to 1.9 % of GDP at the end of 2016, down from 4.8 % in 2015. In October 2017, the National Asset Management Agency (NAMA) redeemed the final EUR 500 million of its government-guaranteed debt, three years ahead of target.

Long-term fiscal sustainability risks related to the cost of ageing remain. According to the most recent long-term assessment approved by the Economic Policy Committee Ageing Working Group, the cost of ageing presents a medium fiscal sustainability risk over the long-term. Despite more favourable population projections than those assumed in the previous assessment undertaken in 2015, total age-related expenditure is forecast to rise by 4.1 pps. of GDP during 20162070, with total pensions alone rising by 1.6 pps. of GDP (European Commission, 2018a). Moreover, while the Irish authorities have legislated a wide range of reforms to contain public pension expenditure, the total pension system deficit will grow significantly from 1.7 % of GDP in 2016 to 2.7 % of GDP in 2070.

4.1.2.Fiscal frameworks and spending reviews

Overall government expenditure in 2017 was within budget allocations. The overall spending remained on target. In some departments, however, slippages of around EUR 480 million emerged, driven by current healthcare expenditure and increased capital spending on housing. This was offset mainly by a lower than expected EU budget contribution and debt interest payments. Current primary expenditure was up 4.0 % yoy and on profile. Capital expenditure was up 9.3 % yoy and above profile (EUR 44 million). The overruns were largely accommodated within the supplementary 2017 expenditure agreed by the parliament in December 2017.

Budget 2018 has benefited from a new spending review process. The government carried out a spending review of current expenditure to help prepare Budget 2018, by analysing the current spending package and new policy proposals. The spending review, in its first three-year cycle, focused on specific critical spending areas, representing around 30 % of current government expenditure. Examples would be drug costs in the healthcare sector, disability and employment support in the area of social protection, and public transport (European Commission, 2018c). The process for setting and revising three-year expenditure ceilings and, more generally, the medium-term budgetary framework, could also be reviewed. Despite the evident improvements in the expenditure management framework, year-on-year departmental budgeting has led to repeated changes to expenditure ceilings, which ultimately weakened multi-annual spending planning.

A Rainy Day Fund could contribute to more sustainable growth. The resilience of public finances to economic fluctuations and adverse shocks could be strengthened. In its 2017 Summer Economic Statement the government proposed that EUR 500 million per year (around 0.2 % of projected 2019 GDP) of the 20192020 fiscal space be deployed in a Rainy Day Fund. However, the details of this fund still need to be set out (European Commission, 2018c). As discussed in the Irish Fiscal Advisory Council's pre-budget 2018 statement (IFAC, 2017), it is unclear how the design of the Rainy Day Fund could ensure that it is truly countercyclical.

4.1.3.Taxation

Tax revenues have increased a lot in recent years, but the volatility of certain sources of revenue remains a concern. On the back of the strong economic recovery, tax revenues increased at an average annual rate of around 7% over the period 2011-2017. However, as a proportion of GNI* (Box 1.1), they were just below 28 % in 2016, 2 pps. lower than the historical average (1995-2015). Corporate income taxes as a percentage of total taxation continued to increase, amounting to 11.6 % of total taxation in 2016, the highest level since 2006 and an increase of 3.3 pps. since 2014. As outlined in the 2017 country report (Section 4.1.3), corporate tax revenue is highly concentrated and prone to volatility. However, the reduction in capital allowances for intangible assets may help smoothen corporate tax revenue over time.

Broadening the tax base can help improve revenue stability in the face of economic fluctuations. According to a EUROMOD simulation (

), however, the personal income tax base has been narrowed in the last few budgets (

). The measures in Budget 2018 show a mixed picture in terms of their impact on tax bases (European Commission, 2018c).

Some measures in Budget 2018 seem to shift towards more volatile sources. Proposals such as increasing the stamp duty rate on commercial property purchases — although intended to rebalance development towards residential property — increase reliance on transaction-based taxes, a highly pro-cyclical source of government revenue. The high proportion of corporate taxation, and the dependence on a small number of major taxpayers, remains a source of uncertainty, prone to economic fluctuations potentially stemming from swift decisions made by multinationals.

Some indicators suggest that Ireland's corporate tax rules are used in aggressive tax planning structures. As shown in a study, Ireland's high inward and outward FDI stock (

) can only partly be explained by real economic activities taking place in Ireland (IHS, 2018). The high level of dividend payments and, in particular, charges for using intellectual property, suggest that the country’s tax rules are used by companies that engage in aggressive tax planning (Graph 4.1.3) (

). Exemptions from withholding taxes on dividend payments made by companies based in Ireland () may lead to those payments escaping tax altogether, if they are also not subject to tax in the recipient jurisdiction. This may facilitate aggressive tax planning. Furthermore, the existence of some provisions in bilateral tax treaties between Ireland and some other countries may be used by companies to overrule the new tax residence rule put in place in Ireland in 2015 (

).

Ireland has taken measures to amend some aspects of its system that were facilitating tax planning. Changes to tax residency rules implemented in 2015 have reduced opportunities for aggressive tax planning, although existing companies are able to use the previous rules until the end of 2020. The Irish Knowledge Development Box, introduced in 2015, has been approved by the Code of Conduct on Business Taxation Group and the OECD Forum on Harmful Tax Practices. While the economic evidence for the effectiveness of patent boxes in encouraging R&D remains limited (CPB, 2014), they may be used as a tax competition tool (Alstadsæter et al., 2017). The government has published an Independent Review of the Corporation Tax Code (Coffey, 2017) and is carrying out a consultation on some of its recommendations (Department of Finance, 2017b). The provisions of the Anti-Tax Avoidance Directives (ATADs) will have to be transposed into national law by the end of 2018 and 2019. This will introduce new anti-abuse rules (

). Once it is clear whether additional changes will be brought forward following the consultation, it will be important to assess to what extent these, in conjunction with the effect of the transposition of the ATADs and steps such as the change of the tax residency rule, limit the scope for aggressive tax planning in Ireland.

|

Graph 4.1.3:Charges paid for the use of intellectual property

|

|

|

|

Source: Eurostat

|

Ireland has further potential to improve the way that its tax system can support environmental objectives. Revenues from environmental taxes are above the EU average as a percentage of total taxation (7.9 % for Ireland compared to an EU-28 average of 6.3 %). However, the different tax treatment of diesel and gasoline for road use is still to be addressed. In Ireland diesel is taxed at a lower rate both in terms of carbon and energy content, although it also emits more air pollutants. The tax advantage in favour of diesel currently stands at 11 cents per litre (Department of Finance, 2017).

4.2.

Financial sector and indebtedness

4.2.1.Banking sector*

The financial sector keeps its stable performance course amid heightened external uncertainties. Domestic banks remain susceptible to external spillovers, most notably from the UK’s decision to leave the EU. As a result, the stock prices of Irish banks remained relatively flat in 2017, trading below the euro area financial indices. Despite these conditions, state-owned Allied Irish Banks (AIB) successfully completed its initial public offering in June 2017 with the sale of a 25 % stake, raising EUR 3.4 billion.

The capital buffers of Irish banks improved. The aggregate Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital position of Irish banks was 17.3 % in June 2017, up from 16.8 % at the end of 2016. This improvement was largely possible due to increasing net interest margins, NPL reduction, and a reversal of provisions. In addition to the external uncertainties, relatively weak lending volumes and the impacts of new regulatory measures may lower capital buffers in the medium term. An eventual tightening of monetary policy could have a positive impact on interest income but could also increase debt servicing costs for borrowers. The restructured mortgage accounts could be especially vulnerable to changes in the interest rate environment.

The banks are preparing to fulfil new regulatory requirements. The impact of the upcoming IFRS9 reforms (

) is expected to be manageable, and progress is also made towards achieving the minimum requirement for own funds and eligible liabilities (MREL) (

).

The profitability levels achieved in 2014 are being maintained (Graph 4.2.1). Irish banks have relatively high net interest margins compared to their peers. They have managed to further reduce their deposit funding costs and keep their administrative costs stable. Pressures could arise on the staffing expenses side, in view of a potential tightening of the labour market and the possible relocation of financial companies from London to Dublin.

|

Graph 4.2.1:Profitability of the main domestic banks

|

|

|

|

Source: Central Bank of Ireland

|

NPLs are reducing as a result of debt restructuring activities and portfolio sales, but remain high. The acceleration of NPL resolution is paramount for the systemic risk reduction as noted in EAR 4. The three main domestic banks have put a lot of work into reducing their non-performing loan book (Graph 4.2.2), although with varying success. Their distressed loan-books reduced by about EUR 4.5 billion between September 2016 and September 2017, with the most progress being made in commercial real estate and corporate portfolios. The aggregate NPL ratio for the domestic banks was 14.4 % at the end of June 2017. It stood at 11.6% when accounting for foreign branches and subsidiaries. The banks are required to submit their portfolio-specific NPL reduction plans and projections to the supervisor. In September 2017 12.7 % of the total mortgage stock was in arrears (CBI 2017).

The level of bank provisions against NPLs is among the lowest in the EU, and declining. The average coverage ratio (

) of Irish banks was 32.6 % in June 2017, compared with the 45.8 % euro area average. While some provision releases are linked to debt resolution activities and domestic real estate price increases, it is important for them to remain at prudent levels.

|

Graph 4.2.2:NPL reduction by portfolio - domestic banks

|

|

|

|

Source: Central Bank of Ireland

|

Long-term mortgage arrears resolution is progressing more slowly because there are difficulties in restructuring certain difficult cases. The stock of mortgage arrears declined by about EUR 1.8 billion in the year to September 2017. Recent research also shows that since 2013 the share of permanent (durable) mortgage arrears restructurings has increased significantly (McCann 2017b). Still, over 70 % of the remaining arrears balance relates to mortgages with payments overdue for longer than 2 years. By the end of 2016, only 61 % of these debtors had engaged with their creditors. Of those who engaged, 13 % never concluded a modification arrangement, 64 % received a temporary modification (some of these have already elapsed) and only 16 % received a permanent modification, (McCann, 2017). The number of personal insolvency applications has increased since the introduction of the Abhaile aid-and-advice scheme, but it is still quite low. The number of actual arrangements has declined, largely due to the increase in cases currently subject to court reviews. These are sought by the debtor when the personal insolvency proposal has been rejected by creditors. Following a Review of the Mortgage to Rent Scheme, a range of amendments to its eligibility criteria and administration came into effect to enable more properties to qualify and to make the scheme more flexible and accessible to borrowers.

The mismanagement of a significant number of tracker mortgages by banks is being addressed through an industry-wide examination led by the CBI (CBI 2017a) (

). As of mid-December 2017, approximately 33,700 mortgage accounts have been identified as having been put on an incorrect interest rate, resulting in overcharging or even property loss. The examination continues with around EUR 297 million paid out by the banks to affected customers so far.

Macroprudential policy is gaining importance amid the current housing sector dynamics. Current housing market pressures, resulting from a scarcity of residential properties, highlight the importance of having prudent loan-to-value and loan-to-income limits in place. The second review of the framework currently in place, completed in November 2017, recognised this by retaining the binding loan-to-value and loan-to-income ratios. The change that will be in force from January 1, 2018 pertains to the size of the banks' discretionary buffer (lending above the loan-to-income cap) for non-first-time buyers, from 20% to 10% of the value of new lending. The implementation of the credit register is in its final phase, after several delays. The register should become operational in early 2018 and cover all types of lending by the end of 2018. It will be a crucial tool for accurately assessing the debt servicing capacity of borrowers.

4.2.2.External sustainability*

External sustainability risks to the domestic economy seem limited. The analysis presented in the 2017 country report (European Commission, 2017a) showed that a substantial proportion of Ireland’s external liabilities are attributable to multinational companies with little connection with the domestic activity. The risks associated with the external liabilities of these companies are mitigated by a number of factors such as their high profitability and offsetting overseas assets. Moreover, their liabilities are not linked to Irish investors. IMF analyses reach similar conclusions, showing that external debt not related to the International Financial Services Centre (IFSC) (

) is only moderately sensitive to standardised shocks, i.e. interest rate (IMF, 2017).

The headline net international investment position is improving but remains negative. Ireland’s net international investment position (NIIP) had been falling rapidly before 2015, when it fell at -244 % of GDP (Q12015) (

). By the third quarter of 2017, it had improved to -170 % of GDP but it remains significantly negative. It is expected to improve further in 2018, on the back of GDP growth and current account surpluses.

The international investment position of domestic sectors is improving slightly. In sectoral terms, and excluding the IFSC, the largest proportion of the NIIP is attributable to the nonfinancial sector. It consists of multinationals — including re-domiciled PLCs, aircraft leasing and contract manufacturing companies. In the second quarter of 2017 the NIIP of these multinationals was -154.1 % of GDP. The trends in the net position of domestic sectors — the Central Bank, non-IFSC banks, general government — gradually improved in 2016 (Graph 4.2.3).

The composition of the NIIP is biased towards riskier instruments, but these mostly belong to multinationals. In 2016, debt instruments (for all sectors in the economy) accounted for approximately -234 % of GDP in net terms, but the foreign direct investment (FDI) and equity shares instruments had a positive net position (57 % of GDP). The concentration of debt liabilities, such as bonds and fund shares, increases the sustainability risk as these instruments require payments of principal and interests at defined moments in time and irrespective of the liabilities’ performance, which means they carry a higher probability of default (

). However, the majority of these liabilities relate to nonresident funding of intellectual property (IP) assets (CSO, 2017b). In 2015, the negative financial worth of Ireland dropped by 70 % y-o-y, at EUR -531 billion. The sharp decline was due to an increase in equity and fund shares used to fund IP assets and machinery and equipment, including aircraft for leasing, as nonfinancial assets registered in Ireland (

).

|

Graph 4.2.3:International investment position by institutional sector, non-IFSC

|

|

|

|

Source: CSO

|

The current account (CA) balance remains very volatile and difficult to assess. The headline CA experienced a substantial level shift in 2015, surging to a surplus of around 11 % of GDP, linked to the activities of multinationals. These activities also disrupted the services trade and the primary income balance on account of large imports of IP services.

|

Graph 4.2.4:Current account balance benchmark

|

|

|

|

Source: European Commission

|