EUR-Lex Access to European Union law

This document is an excerpt from the EUR-Lex website

Document 52006SA0008

Special Report No 8/2006: Growing success? The effectiveness of the European Union support for fruit and vegetable producers' operational programmes together with the Commission's replies

Special Report No 8/2006: Growing success? The effectiveness of the European Union support for fruit and vegetable producers' operational programmes together with the Commission's replies

Special Report No 8/2006: Growing success? The effectiveness of the European Union support for fruit and vegetable producers' operational programmes together with the Commission's replies

OJ C 282, 20.11.2006, p. 32–58

(ES, CS, DA, DE, ET, EL, EN, FR, IT, LV, LT, HU, MT, NL, PL, PT, SK, SL, FI, SV)

|

20.11.2006 |

EN |

Official Journal of the European Union |

C 282/32 |

SPECIAL REPORT No 8/2006

Growing success?

The effectiveness of the European Union support for fruit and vegetable producers' operational programmes

together with the Commission's replies

(Submitted pursuant to Article 248(4), second subparagraph, EC Treaty)

(2006/C 282/01)

CONTENTS

|

I-XI |

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY |

|

1-18 |

INTRODUCTION |

|

1-3 |

Objective of the aid scheme: adapting to the changing market situation |

|

4-8 |

Audit scope and approach |

|

9-12 |

Producer organisations |

|

13-18 |

The aid for operational programmes |

|

19-63 |

PART I: EFFECTIVENESS OF OPERATIONAL PROGRAMMES |

|

20-49 |

Has the aid scheme been implemented in a way to ensure that operational programmes are likely to be effective? |

|

20-23 |

Commission checks to ensure that Member States grant the EU aid according to the principles of sound financial management |

|

24-49 |

Member States' implementation of the aid scheme |

|

50-59 |

Have the measures financed in operational programmes been effective? |

|

51-52 |

Producer organisation evaluations of operational programmes (final reports) |

|

53-59 |

Sample of operational programme actions |

|

60-63 |

Conclusions on the effectiveness of operational programmes |

|

64-86 |

PART II: PROGRESS MADE BY PRODUCER ORGANISATIONS |

|

65-86 |

Have producer organisations made progress towards achieving the objectives set for the aid scheme? |

|

66-68 |

Sample of producer organisations |

|

69-86 |

Commission data on producer organisations |

|

87-93 |

CONCLUSIONS |

|

87-90 |

The effectiveness of operational programmes |

|

91-93 |

Progress made by producer organisations |

|

94-100 |

RECOMMENDATIONS |

|

95-96 |

Make the aid for operational programmes simpler and more effective |

|

97-98 |

Better target the policy to achieve the overall objectives of concentration and adaptation |

|

99-100 |

Question the policy of encouraging producer organisations |

Annex: Audit criteria for the approval of effective operational programmes

The Commission's replies

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

|

I. |

A new policy was introduced in 1996 to support fruit and vegetable growers in adapting to the changing market situation. This offered aid for 50 % of the costs of measures taken by growers in ‘operational programmes’, which aimed, inter alia, to improve product quality, reduce production costs and improve environmental practices. The aid is only available to groups of growers that collectively market their produce in ‘producer organisations’. Member States are responsible for approving operational programmes and paying the aid. In 2004, the aid amounted to 500 million euros. |

|

II. |

The Court audited the effectiveness of this aid scheme based primarily on a random sample of 30 operational programmes in eight Member States and on a review of Commission data. |

|

III. |

Member States based their decisions to approve operational programmes on the nature of the planned expenditure, without also taking account of the likely effectiveness of the proposed measures. The programming elements required by the regulations were followed nominally, at a significant cost but without real benefits. The criteria for the eligibility of expenditure were not clear, resulting in uncertainty. |

|

IV. |

The Commission checks the eligibility of operational programme expenditure, but has not checked whether Member States' procedures for approving operational programmes ensure that the expenditure is likely to be effective. It has not monitored the effectiveness of operational programmes or evaluated the policy. |

|

V. |

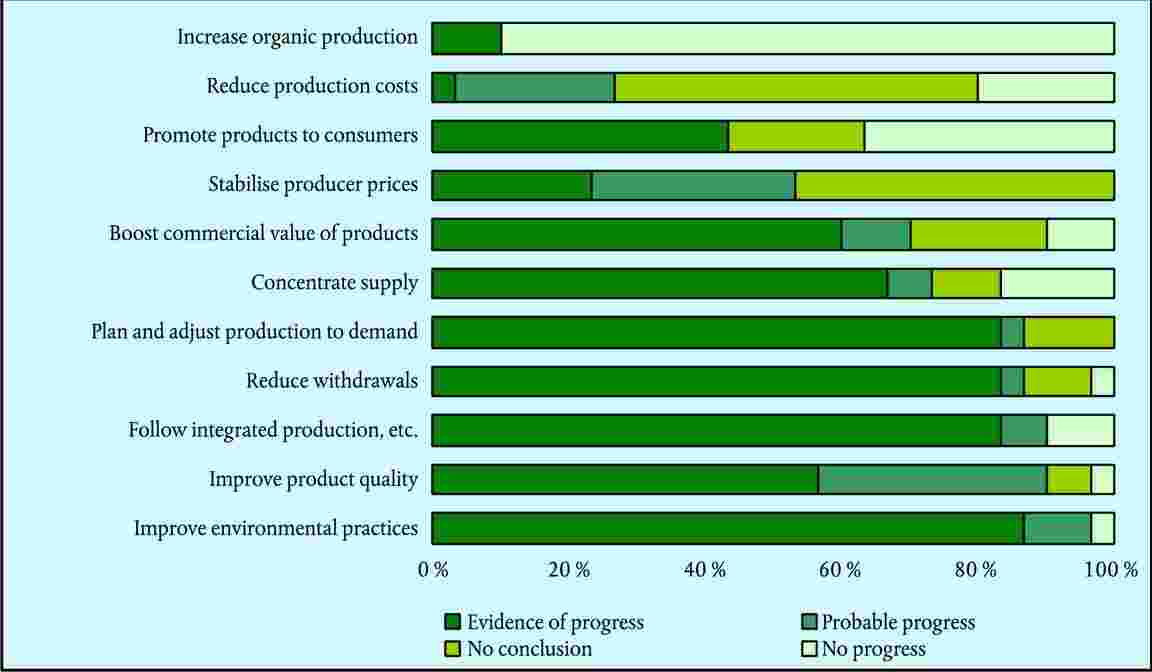

Operational programmes have, on the whole, resulted in progress being made towards the Council regulation's objectives. Almost half of the actions financed represented a significant advance from the producer organisations' initial situation towards at least one of the 11 objectives, and can therefore be considered effective. However, the effectiveness of the majority of the actions was low, in that they did not result in a significant advance from the producer organisations' initial situation. |

|

VI. |

Producer organisations in the sample had made progress towards most of the objectives set for the policy. However, the Commission has no information on the achievement of these objectives at the European level with two exceptions: for withdrawals from the market of surplus produce, which have been reduced, and for the concentration of supply. |

|

VII. |

On current trends, the Commission's target of 60 % of supply concentrated in producer organisations by 2013 will not be reached. Producer organisations account for only about one-third of the EU's fruit and vegetable production and they have grown at a lower rate than the sector as a whole. |

|

VIII. |

The Court recommends that the Commission considers the merits of alternative approaches to simplify and reduce the costs of the scheme and improve the effectiveness of the aid. The Commission should consider if this could best be achieved by aligning the scheme's procedures and rules for the eligibility of expenditure with those of the Rural Development investment measures. |

|

IX. |

Whichever approach is followed, the Commission should improve its monitoring of the effectiveness of the aid and use the planned evaluation study in 2009 to establish the reasons for the relative lack of progress by producer organisations, particularly in those Member States where the fruit and vegetables sector represents the highest proportion of agricultural output. |

|

X. |

If the evaluation confirms that producer organisations are an effective mechanism for strengthening the position of growers in these Member States, the policy should be better targeted to achieve this. |

|

XI. |

If, on the other hand, the Commission cannot demonstrate that the concentration of supply in producer organisations delivers real benefits, it should reconsider this mechanism for supporting the EU's fruit and vegetable growers. |

INTRODUCTION

Objective of the aid scheme: adapting to the changing market situation

|

1. |

Faced in the 1990s with a changing market for fruit and vegetables, requiring different products and increased guarantees of quality and environmental standards, the EU introduced a new aid scheme to support growers in adapting to this demand. This was the aid for ‘operational programmes’, which is described below. At the same time, cuts were made in the long-standing aid for withdrawals (1), providing a further incentive for the EU's growers to produce what the market wanted. |

|

2. |

The market situation was also changing with the increasing dominance of a few large retail and distribution groups. In response, the EU strengthened the policy followed since the 1960s encouraging the formation of groups of growers known as ‘producer organisations’ with a view to obtaining economies of scale and a stronger market presence. |

|

3. |

This grouping of supply (or ‘concentration’) was encouraged by making membership of a producer organisation a condition for receiving the new aid for operational programmes. Fruit and vegetable growers not in producer organisations were not eligible for the EU aid. This created an incentive for growers to form or join producer organisations. At the same time, the EU set stricter conditions to be met by the producer organisations to ensure that they would be effective in concentrating the supply. |

Text box 1‘An intelligent aid’ enthused the director of a fruit and vegetable producer organisation we visited. No longer does the EU hand out aid to growers to destroy their surplus fruit and vegetables that no one wants to buy. Now, the EU subsidises measures taken by the growers to adapt their production to the quantity and quality for which there is demand.

Text box 2‘Growing success’: The aid is linked to turnover, so the more producer organisations grow, the more aid they get to finance adaptation. This success should encourage more growers to form or join producer organisations, resulting in more bargaining power and a higher turnover, and therefore more aid for further adaptation…

Audit scope and approach

|

4. |

The Court reported the results of its previous audit of the aids for the fruit and vegetable sector in the Annual Report for 2000 (2). At that time, few operational programmes had been completed, so the longer-term effectiveness of the aid was not apparent. However, the report identified weaknesses in the Member States' management of the scheme, which had reduced the effectiveness of the aid. In the light of this, the objective set for this audit was to assess the effectiveness of the aid scheme for operational programmes. |

|

5. |

Effectiveness is defined in the EU's Financial Regulation (3) as ‘attaining the specific objectives set and achieving the intended results’. As the objectives set for the operational programme aid scheme are not definite or quantified, in this audit, effectiveness is considered as making progress towards those objectives. |

|

6. |

The questions set for this audit were:

|

|

7. |

The audit approach consisted of:

|

|

8. |

The audit fieldwork was undertaken in 2005, based on a random sample of 30 operational programmes completed in 2003 and 2004 in eight Member States: Greece, Spain, France, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, and the United Kingdom. Producer organisations in the new Member States were not included as they had not completed operational programmes at the time of the audit. |

Producer organisations

|

9. |

A producer organisation is a group of growers who act together to strengthen their position in the market. Many are cooperatives, but they can be groups of individuals or groups of companies. The conditions to be met, set out in the EU regulations (4), are to have at least five members and a minimum turnover of 100 000 euro. Producer organisations have to provide the means for storing, packaging and marketing their members' produce. They have to be able to plan and adapt their production, and promote environmentally sound cultivation and waste-management practices. |

|

10. |

A start-up aid is available over a five-year period for new producer organisations to set up and acquire the facilities they need to meet the EU's conditions. Once established, Member States check that producer organisations continue to meet these conditions, although no further aid is available for this. In principle, the EU does not support producer organisations' administrative, operating or production costs (5). |

|

11. |

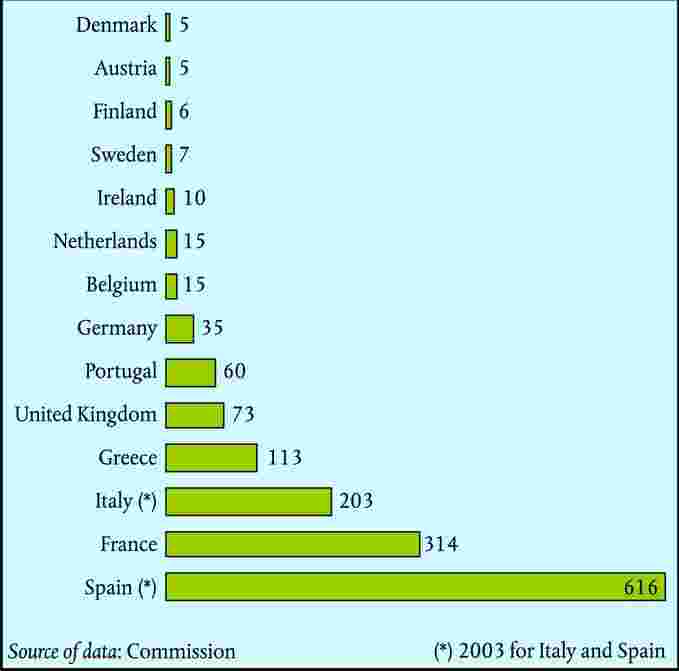

There are some 1 500 producer organisations in the 14 Member States (6)(Diagram 1). There is a great diversity in the sizes and nature of producer organisations (Diagram 2). In the course of this audit, the Court visited fig growers in Greece and mushroom growers in Ireland, a citrus fruit cooperative in Portugal and tomato growers from Spain to the Netherlands. Some had fewer than 10 members, one in Italy specialising in apples had 5 800 members. One producer organisation was made up of 14 companies, each with turnover averaging 2,6 million euro, another was a cooperative of 800 part-time growers averaging just 600 euro of produce each. The average EU producer organisation in 2003 had a turnover of 9 million euro and over 300 members.

|

|

12. |

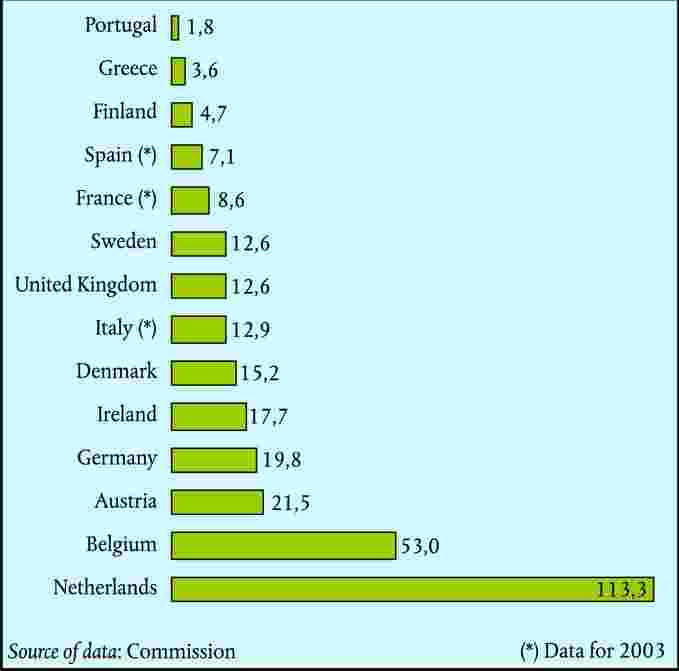

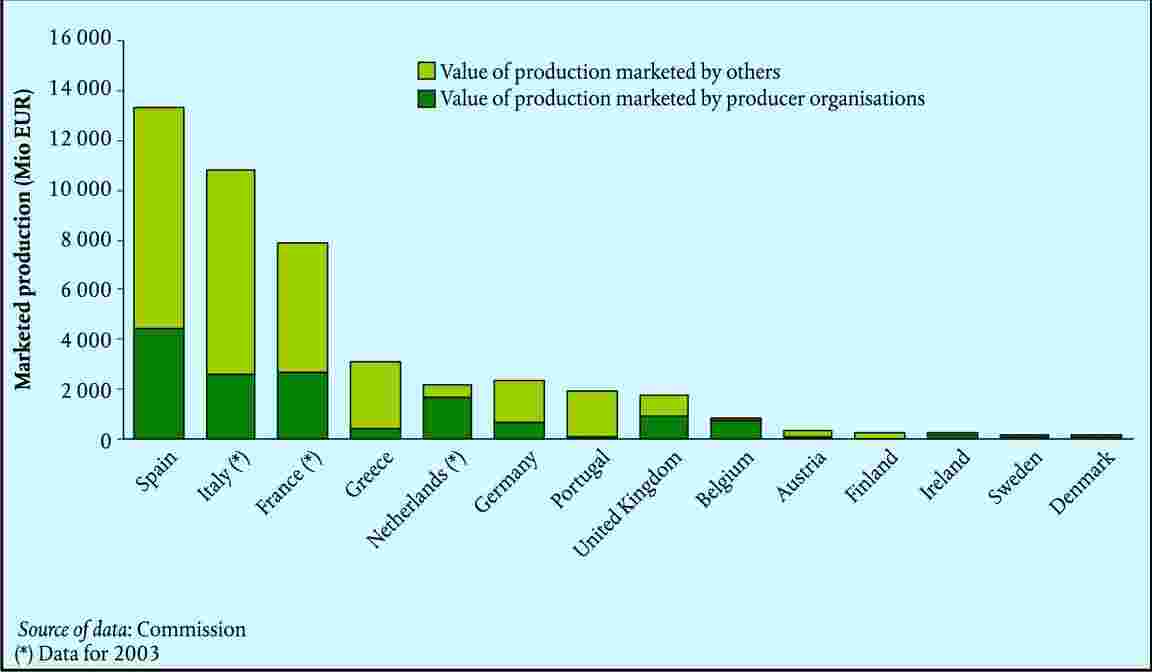

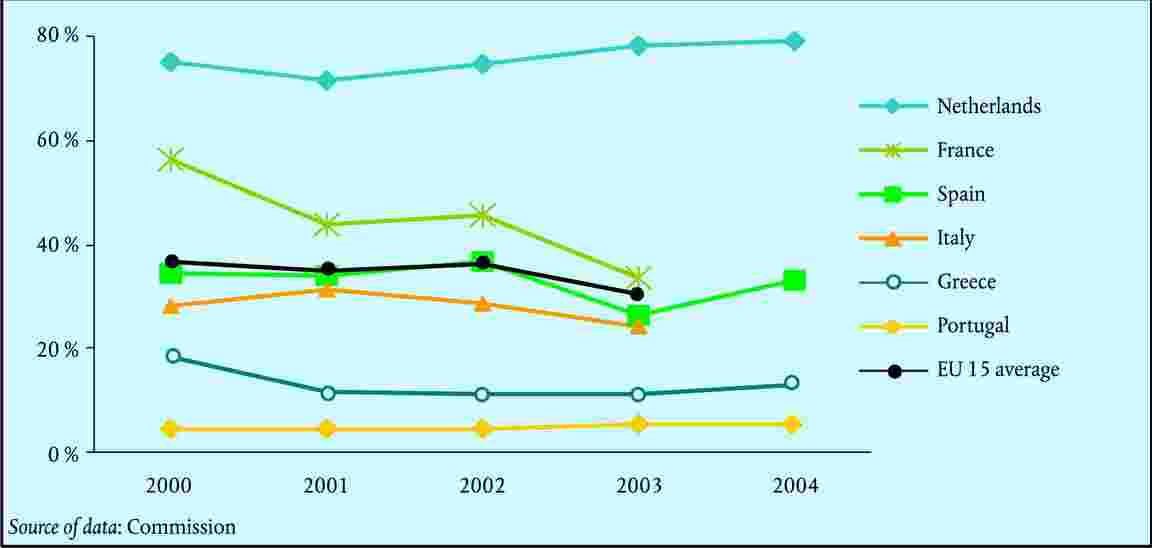

Fruit and vegetables is the largest agricultural sector by value of output in the EU-15. It is particularly important to the agricultural economies of Greece, Spain, Italy and Portugal, where the sector represents over 25 % of the value of agricultural output. Spain, France and Italy together account for 70 % of EU fruit and vegetable production by value. About a third of their production was marketed by producer organisations in 2004. In the Netherlands, Belgium and Ireland, the proportion of fruit and vegetable output marketed by producer organisations was much higher, at around 80 %, whereas in Greece it was 13 % and in Portugal 6 % (Diagram 3).

|

The aid for operational programmes

|

13. |

Producer organisations that meet the conditions in paragraph 9 can apply for aid for an ‘operational programme’. This is a programme of measures that a producer organisation undertakes to adapt its members' production to market demand and strengthen its position in the marketplace (Text box 3). The specific objectives that the measures should aim to achieve are set in the Council regulation (7) (Text box 4). The programme is drawn up by the producer organisation and approved by the Member State, which pays EU aid annually of 50 % of the costs incurred by the producer organisation in implementing the programme. The duration of an operational programme is between three and five years, and at the end of the period a producer organisation may apply for a new programme. There is an annual ceiling on the aid, set at 4,1 % of the producer organisation's turnover. |

|

14. |

Over 70 % of producer organisations have an operational programme and the aid amounted to 500 million euro in 2004. This represented 3 % of producer organisations' turnover and approximately 1 % of the total value of EU fruit and vegetable output. Take-up of the aid has increased greatly since it was introduced in 1997, at the same time as the aid for the withdrawal of surplus production has decreased (Diagram 4). The diagram also shows the aid paid through producer organisations to growers of tomatoes and fruit for processing, which is based on the volume of production.

Text box 3Typical contents of an operational programme — purchase of sorting and packing machinery — employment of quality control staff and marketing staff — investments in irrigation facilities and greenhouses — subsidies to growers for replanting fruit trees — costs of natural pest and disease control approaches

Text box 4The 11 operational programme objectives — ensuring that production is planned and adjusted to demand, particularly in terms of quality and quantity — promoting the concentration of supply and the placing on the market of the products produced by its members — reducing production costs and — stabilising producer prices — promoting the use of environmentally-sound cultivation practices, production techniques and waste-management practices — improvement of product quality — boosting products' commercial value — promotion of the products targeted at consumers — creation of organic product lines — the promotion of integrated production or other methods of production respecting the environment — the reduction of withdrawals

|

|

15. |

Implementation of the aid scheme is on the usual shared management basis whereby Member States follow detailed rules, set by the Commission, within the framework of the Council Regulation. They are required to cooperate with the Commission to ensure that the aid is granted according to the principles of sound financial management: economy, efficiency and effectiveness. |

|

16. |

The Commission implementing regulation (8) requires producer organisations to describe in their operational programme proposal:

|

|

17. |

Producer organisations have the freedom to propose operational programme measures that suit their particular situation, with the proviso that the programmes must target ‘several’ of the objectives set out in the Council regulation (see Text Box 4). To complete the feedback circuit, producer organisations are required to report to the Member State at the end of the programme on the extent to which they have achieved their objectives, and the lessons to be learnt for their next programme. This ‘programming model’ to be followed by producer organisations is illustrated in Diagram 5.

|

|

18. |

The Commission regulation also specified a number of checks that the Member States should make on the operational programme proposals:

The regulation provided that the Member States should then approve the programme, require changes, or reject it. |

PART I: EFFECTIVENESS OF OPERATIONAL PROGRAMMES

|

19. |

As described above, Member States and the Commission share the responsibility to ensure that the aid scheme is effective: that the aid is used to achieve progress towards the 11 objectives the Council set for operational programmes. This part of the report first looks at whether the aid scheme was implemented by the Commission and Member States in a way to encourage effectiveness, and in particular, if the ‘programming model’ operated as intended. It then assesses a sample of operational programmes to determine whether the measures financed resulted in progress towards the scheme's objectives. |

Has the aid scheme been implemented in a way to ensure that operational programmes are likely to be effective?

Commission checks to ensure that Member States grant the EU aid according to the principles of sound financial management

|

20. |

Member States approve the operational programmes proposed by the producer organisations, but under the Treaty, the Commission retains final responsibility for the sound financial management of the EU budget and supervises the Member States. |

|

21. |

In the ‘Clearance of Accounts’ process, the Commission visits Member States to check that the aid payments have been made in compliance with Community rules. The Council regulation also set up a ‘Special Corps of Inspectors’ for the fruit and vegetable sector with the role, inter alia, of ensuring a uniform application of the rules across the EU. In practice, these are the same officials that check expenditure for the Clearance of Accounts. |

|

22. |

In relation to other EU agricultural policies, the operational programme aid scheme requires Member States to exercise a greater degree of judgment in deciding whether to approve, reject or require changes to the measures proposed in an operational programme. However, since the initial checks of the Member States' procedures in 1997 and 1998, Commission inspections have focused on compliance with the criteria for the eligibility of expenditure and have not checked whether the Member State procedures for approving and monitoring operational programmes shown in paragraph 18 operate in a way to ensure that operational programmes are likely to be effective. |

|

23. |

Consequently, while the Commission has checked the eligibility of the aid paid out by Member States for Clearance of Accounts purposes, it has not checked whether this aid has been granted respecting the sound financial management principles, in particular, of effectiveness. |

Member States' implementation of the aid scheme

Details of the audit in the Member States

|

24. |

Given the Member States' key role in approving operational programmes, the Court audited the procedures applied in all 14 Member States concerned (Text box 5). As implementation of the scheme is decentralised in some Member States, the procedures were also checked at a further 19 regional and local administrations in Italy, Spain, France and Greece. |

|

25. |

The implementing regulation requires Member States to make a number of checks, but does not prescribe how. This gives Member States the flexibility to organise these procedures according to their context. Consequently, each administration has implemented the scheme in a different way and the findings below do not apply equally in all Member States (9). |

Text box 5Details of the audit in the Member States:We based the audit of the Member States' procedures on a random sample of 30 operational programmes completed in 2003 and 2004. We visited the Member States' administrations responsible for approving those programmes and the producer organisations concerned. Number of operational programmes selected Spain 11 Portugal 2 France 8 United Kingdom 1 Italy 4 Netherlands 1 Greece 2 Ireland 1

The selected operational programmes were approved by the Member States between 1998 and 2001. To obtain sufficient evidence, and ensure that findings were still relevant, we examined documentation from 1998 to 2005 for a further 94 operational programmes and 103 evaluation reports. We selected these randomly at the Member State authorities we visited.We undertook a more limited audit of the procedures followed by the other six Member States, based on a questionnaire and a check of documentation concerning randomly selected operational programmes.

Criteria for assessing the implementation of the programming model

|

26. |

To comply with the requirements for sound financial management, Member States should apply the principles of economy, efficiency and effectiveness in deciding whether to approve an operational programme, thereby granting the EU aid. |

|

27. |

For the aid to be effective, each action financed in the programme should have an effect: the action should result in progress being made towards one or more of the 11 objectives set by the Council Regulation. Consequently, Member States should base their decision on whether to approve, reject or require changes to an operational programme on whether the producer organisation has satisfactorily demonstrated that the proposed actions are likely to achieve these objectives. |

|

28. |

Member States need detailed information from the producer organisations to be able to justify their decisions to award the aid in these terms. They need to know, for each objective, the producer organisation's initial situation and what impact the action(s) is expected to have. |

|

29. |

Following this logic, and the specific requirements of the Regulation (see paragraphs 16 to 18), the Court developed audit criteria for what would be reasonable to expect in a ‘good’ system (Text box 6). If these criteria are met, Member States' procedures are likely to ensure that the aid will be effective. These criteria can be summarised as follows:

|

Text box 6Methodology: Some of the Court's criteria for assessing the Member States' implementation of the aid scheme go beyond formal compliance with the letter of the regulation (see Annex). As an illustration, to comply with the regulation the producer organisation has to describe its initial situation, and the Member State has to check its accuracy. To meet the audit criteria, the Member State should also ensure that the description is related to the objectives and actions in the proposed programme. If not, the description of the initial situation has little purpose.

The initial situation description is not related to the operational programme objectives

|

30. |

All but two of the operational programmes examined included a section called ‘initial situation’ and more than half (60 %) formally complied with the regulation by mentioning production, marketing and equipment, even if very briefly. Some Member States required producer organisations to list their equipment and facilities and give a table of their production in tonnes and by value, but without requiring this to be related to the programme's objectives or actions in any way. Other Member States issued no particular instructions, and accepted very general descriptions, in some cases of only one or two sentences. Few producer organisations described their initial situation in respect of the environment, product quality and production costs, yet nearly all operational programmes had these objectives (see Text box 7). No producer organisation described the initial situation for each of the objectives in its operational programme. |

Text box 7Regional authorities in Spain approved an operational programme containing ten actions with a total cost of 770 000 euros. Six of these actions had the objective of improving product quality, eight had the objective of reducing production costs, and two had the objective of improving environmental practices.The producer organisation listed in the initial situation the types of fruit grown and the surface area, but gave no information on the initial quality of the fruit, the costs of production, or the environment.

|

31. |

In a few cases, producer organisations described the starting situation in relation to specific actions, which is a requirement in the Netherlands, for example. This went some way to meeting the criteria, but did not sufficiently describe the producer organisation's initial situation in terms of its objectives. |

The contents of operational programmes do not always relate to the stated objectives

|

32. |

Several Member States required producer organisations to explicitly state in their operational programmes which EU objectives related to each action. In these cases, the correspondence between the objective and the programme was automatic on paper, making the Member States' check of the compliance of objectives with those in the regulation a formality. However, many producer organisations listed any objective that seemed relevant in an attempt to justify the programme or particular action, regardless of whether that was their real objective or not (Text boxes 8 and 9). |

|

33. |

In Italy and Greece, the authorities developed detailed lists of possible actions, from which the producer organisation could choose, and gave a predetermined objective to each action. The French authorities also issued a list of possible actions, but classified according to their nature, not their objective. For the environmental and quality categories of actions the relevant objective was usually evident, but for the category ‘measures linked to production facilities’ sometimes it was not. As a result it was not possible to identify the objective of some of the actions on the basis of the operational programme documentation (Text box 10). The Italian, Greek and French authorities did not attempt to check the objectives of individual programmes as they considered that the compliance of the actions with the EU objectives had been established when drafting the national lists of actions. However, changes over time to the classification had the effect of ‘changing’ the operational programmes' objectives for a given action (Text box 11). |

Text box 8An operational programme in the Netherlands included an electronic delivery note system at a cost of 135 000 euro with the objective ‘planning and adjusting production to the demand’. The producer organisation could not demonstrate a relation between the action and this objective. The real objective, the reduction in costs, was not mentioned in the operational programme.

Text box 9In an operational programme approved by the regional authorities in Spain, a producer organisation purchased a fork-lift truck at a cost of 25 000 euro. The producer organisation could not demonstrate a relation between the action and the stated objective of ‘reducing withdrawals’.

Text box 10In an operational programme in France, a producer organisation included an action described as ‘provision of services’ a cost of 50 400 euro. 25 % of this cost was allocated to the objective of ‘improving quality’ and 25 % to ‘improving environmental practices’. We were unable to identify the EU objective related to the remaining 50 % of the costs.

Text box 11An irrigation project in Italy was allocated to the objective of ‘improving quality’ in accordance with the 1997 national guidelines. Following a revision of the guidelines it was given the objective of ‘concentration of supply’ in 1999. In 2002 a further revision classified the same action under the objective ‘reducing costs’.

Operational programme objectives are not given in measurable terms and targets are not set

|

34. |

Only the United Kingdom authorities formally required producer organisations to set measurable objectives for operational programmes, although in practice it did not ensure that this was done. In Spain, Italy and the Netherlands, the authorities required the expected results to be shown for each measure or action, but this was focused on the outputs — how the implementation of the actions could be demonstrated — rather than on the achievement of the objective. In 10 % of the operational programmes examined, producer organisations gave quantified objectives for at least one action where this was straightforward, such as for the expected reduction in costs, or the number of hectares to be converted to organic production. These cases were mostly in Spain and Italy. Otherwise, producer organisations did not set targets or indicators by which achievement of the objectives could be monitored. |

Producer organisations' evaluation reports do not show the achievement of objectives

|

35. |

Except for some cases in France and Ireland, the Member States ensured that producer organisations' final evaluation reports described the implementation of the programme and outputs (what had been done), but none in practice required the reports to also show the extent to which the operational programme objectives had been achieved. As such the reports were of little use for assessing the effectiveness of the aid. |

|

36. |

The evaluations in the final reports were little used by the Member States (10), and were treated as another formality required for compliance with the regulation. In Greece, Spain (11) and Portugal, final reports were simply filed by the paying agency and not examined by the authorities responsible for approving operational programmes. |

|

37. |

The content of the reports varied widely, from less than one page of general unsubstantiated statements such as that ‘quality has been improved’, to over 100 pages of detailed facts and figures on the implementation of the programme, action by action. Member States did not require final reports to contain a common set of information to allow monitoring of the effectiveness of the programmes at regional or national level, and the diversity of the reports made any such analysis impractical. |

Member States do not apply effectiveness criteria when approving operational programmes

|

38. |

In practice, Member States approved the programmes according to the nature of the proposed expenditure, not in terms of what the programme was expected to achieve. Effectiveness criteria, such as additionality, were not applied in deciding whether or not to approve the financing of an action with EU aid. Consideration of factors specifically required by the regulation, such as the initial situation and objectives, the technical quality and economic consistency of the programme, has become redundant and has only been done to the extent necessary to demonstrate compliance with the letter of the regulation. |

|

39. |

Instead, Member States followed a different approach, with the focus placed on compliance with the eligibility criteria and the payment of subsidy as illustrated in Diagram 6.

|

|

40. |

This is largely a result of the amendment of the Commission implementing regulation to introduce ‘eligibility lists’ with which operational programmes since 1999 have had to comply. These list the types of expenditure that can and cannot be included in operational programmes (Text box 12). |

Text box 12Example of eligibility criteria: transport costsEligible: — investments in transport equipped with cold storage. — costs of collection or transport (internal or external), — investments in transport for marketing or distribution.

Ineligible:

|

41. |

The initial implementing regulation in 1997 did not set detailed criteria for eligibility, except to exclude producer organisations' administrative and operating expenditure. Member States were uncertain of what the Commission would accept as eligible expenditure in the Clearance of Accounts process and, in response to queries from the Member States, the Commission issued a series of ad hoc interpretive notes. |

|

42. |

As these interpretive notes had no official status, the Commission amended the implementing legislation to introduce a list of ineligible operations and expenditure. At the same time, it required Member States to check the eligibility of proposed operational programme expenditure against this list before approving operational programmes. In 2001 the Commission added a list of what could be included in operational programmes and in 2003 the interpretive notes were withdrawn and both lists were revised again. The eligibility lists allowed some exceptions to the exclusion of producer organisations' production and operating costs such as certain staff salaries, recyclable packaging and costs of natural pest and disease controls. |

|

43. |

The existence of these eligibility lists does not prevent Member States from also considering the producer organisations' initial situation and objectives and the likely effectiveness of the proposed actions. However, Member States that refuse to approve proposed expenditure defined in the regulation as eligible would have to be able to justify their decision to the producer organisation and also may face legal challenges. Member States can avoid these difficult decisions by approving the same action for all producer organisations that request it, regardless of the objectives or situation of each particular producer organisation (Text box 13). |

Text box 13Example: pallet-boxesIn 10 of the 30 randomly selected operational programmes, Member States had approved the purchase of pallet-boxes, crates or similar containers for collecting, transporting and storing fruit and vegetables at a combined cost of 1,7 million euro. The Commission considers this expenditure to be eligible. The objectives given in the operational programmes included: — stabilising producer prices, — increasing product quality, — boosting products' commercial value, — reducing production costs, — improving environmental practices, — concentration of supply, — reducing withdrawals.

In some cases, the purchase represented an advance from the initial situation to achieve an objective: one producer organisation replaced wooden crates with more hygenic plastic in order to supply a baby-food manufacturer (objective given: improving quality). In other cases these were simply replacements of old, lost or damaged crates, or additional purchases needed for increased production levels, without any clear relation to the given objectives.

The coexistence of the programming model and subsidy approach has increased complexity and costs

|

44. |

In effect, a ‘subsidy approach’ has been followed by Member States rather than a programming approach, while the programming elements of the regulation are still required. The result is that the aid scheme has become more complex than necessary, with increased costs of administration and control. This results from the lack of clarity of the eligibility lists as well as from the coexistence of the programming model. If done properly, preparing operational programmes, annual implementation reports and end-of-programme evaluations entails significant costs for producer organisations. This is all the more so in Member States such as Italy and the Netherlands, which require detailed annual operational programmes also to be submitted for approval. |

|

45. |

The eligibility lists published in the regulation can never be precise enough to cover all possible actions in such a diverse and fast-changing sector and so are written in quite general terms such as ‘quality improvement measures’. Inevitably, queries arise, and the lists are interpreted differently by different Member States and even by different regions within Member States. Even after eight years of operation of the scheme, examples of ineligible expenditure continued to be found by the Commission in the 2005 Clearance enquiries in Spain, France, Italy and the United Kingdom where the Member States had not always interpreted the eligibility rules in the same way as the Commission. |

|

46. |

In the light of the uncertainty on eligibility and the associated risks, several Member State administrations undertake more checks than required by the regulation (12), some visiting every producer organisation several times a year. This adds costs not only for the Member State but also for the producer organisation. |

|

47. |

This uncertainty on the eligibility, the costs of administration and extensive checks of their activities may also deter producer organisations from risking innovative measures, which may ultimately be disallowed. This may encourage them to include only those measures in their operational programmes where the eligibility has been clearly established. |

There is a risk that ineffective actions have been approved

|

48. |

As the programming model has not been properly implemented, the EU budget has been exposed to an increased risk of ineffectiveness: the risk that actions will be approved that do not result in progress towards the EU's objectives. |

|

49. |

Some Member States have argued that they do not need to concern themselves with the effectiveness of the programmes, as producer organisations will normally make the best business decisions for their circumstances. After all, the members of the producer organisation have to co-finance 50 % of the costs of the programme. However, the examples seen in this audit show that some producer organisations use the subsidy to support the costs of their existing activities, which do not represent a step forward from their initial situation. While this may make business sense for the producer organisation, particularly when under competitive pressure, it does not contribute to achieving the objectives of the EU aid scheme. The example in Spain (Text box 14) illustrates the inclusion of costs which are not ‘actions’ or ‘measures’ designed to achieve operational programme objectives, but are normal costs of any fruit and vegetable producer. Although it is not common for operational programmes to include such a high proportion of recyclable packaging (13), Member States have approved significant amounts of expenditure for this. Ten operational programmes in the Court's sample of 30 included a combined total of 4,9 million euro for recyclable or reusable packaging. |

Text box 14Example: Regional authorities in Spain had approved one operational programme in our sample, which included 2,7 million euro for recyclable cardboard boxes. This represented 83 % of the total programme for 2000-2003. In 2001 they approved a revision to the programme which deleted planned investments in greenhouses and irrigation, and increased the budget for recyclable boxes to 98 % of the total. The only other ‘action’ was the salary of a technician.

Have the measures financed in operational programmes been effective?

|

50. |

The previous section showed that the approach followed by the Member States in approving operational programmes results in a risk that the measures financed may not be effective. This section assesses whether or not the actions implemented by producer organisations have been effective in achieving the operational programme objectives. |

Producer organisation evaluations of operational programmes (final reports)

|

51. |

The primary source of information on the effectiveness of operational programmes should be the final reports drawn up by producer organisations at the end of each programme. The regulation requires these to show the extent to which the operational programme objectives have been achieved. None of the 142 final reports examined in this audit gave a full assessment of the achievement of the operational programme objectives. Compliance with this requirement of the regulation has not been included in the Commission's checks of Member States' procedures. |

|

52. |

This represents a missed opportunity for the Commission, which has a specific responsibility under the EU's Financial Regulation to monitor the achievement of policy objectives. Had the final reports contained the required assessments, it should have been possible to analyse a sample of reports and draw conclusions on whether operational programmes had achieved their objectives. With a few well-chosen performance indicators required from all producer organisations, these final reports could have produced a long time series showing progress made in objectives such as improving quality, reducing costs, organic production, and improving environmental practices. |

Sample of operational programme actions

|

53. |

In order to check if operational programme actions have been effective, the Court selected a total of 104 actions at random from thirty producer organisations' operational programmes completed in 2003 or 2004 (Text box 5). The producer organisations were asked to demonstrate the impact of the selected actions in terms of the related operational programme objectives. Some actions had more than one objective, giving a total of 265 cases examined. |

|

54. |

In only 30 % of the cases could producer organisations provide sufficient evidence to show that the action had resulted in progress towards the related objective (Diagram 7). In a further 41 % of cases, while there was no direct evidence, a positive conclusion could be reached based on a logical reasoning (see Text box 15). However, as shown in paragraph 58, in many cases the progress made was only marginal. |

Text box 15Example of ‘probable progress’: A producer organisation in Portugal purchased a refrigerated lorry to stop the quality of its fruit products deteriorating during distribution. It had no data to prove an improvement of quality, but showed us the equipment and explained the refrigeration processes. On the basis of this, we concluded that quality had probably been improved.

|

55. |

In almost a quarter of the cases, the Court could not draw a conclusion on whether or not progress had been made. In most cases, this was because the related objective was so general that it was not possible to prove that there had been no impact. This was particularly the case for the objectives of reducing withdrawals, concentration of supply, and stabilising producer prices (Diagram 8). For example, a producer organisation's raison d'être is to concentrate supply and market its members' produce. Consequently, all of its activities contribute to this objective in some way, however indirectly. |

|

56. |

In 6 % of cases there was clear evidence that no progress had been made (Diagram 7). In a few of these cases, the action had failed: one producer organisation had started an operational programme action concerning organic production, for example, but abandoned the project. In the rest of the cases, the reason for the lack of progress was that objectives had been incorrectly allocated to the measures, either through misunderstanding (several producer organisations understood the objective ‘promotion of products to consumers’ as being promotion to clients), or to comply with a national classification (see paragraph 33). |

Low effectiveness of actions

|

57. |

The results of the sample presented above show only whether there is evidence of progress being made but not the extent of that progress. Although many actions in the sample had clearly moved the producer organisation forward from its initial situation towards the related objectives, in other cases the progress made was only marginal. Replacement machinery usually resulted in some progress as it represented an improvement over the old model. However, in relation to the total cost of the replacement, the progress was sometimes not significant. Similarly, the continuing employment of staff to check product quality enabled the producer organisations to maintain quality levels, but did not necessarily lead to a discernable improvement in quality in relation to previous years. |

|

58. |

In order to gauge the incidence of these ‘low effectiveness’ measures, the Court reviewed each of the 104 actions that had been audited on the spot to consider if they represented a significant advance for the producer organisation from its initial situation towards one or more of the EU's objectives (Text box 16). Against this criterion, more than half (55 %) of the random sample of actions were classed as ‘low effectiveness’. |

|

59. |

These findings show the extent to which Member Sates have approved actions in operational programmes on the basis of their nature (is the action eligible?) without also taking into account their effectiveness (does the action advance the producer organisation towards the objective?). |

Text box 16Examples of actions where we often found a significant advance from the initial situation:

— improvements in production facilities (irrigation systems, energy-efficient greenhouses); — introduction of certified quality schemes. — replacements of machinery such as pallet-movers, fork-lift trucks, lorries and tractors; — pallet-boxes, crates, containers, etc.; — salaries of existing staff (marketing departments, quality checkers).

Examples of actions where we often found no significant advance:

Conclusions on the effectiveness of operational programmes

|

60. |

Member States formally applied most of the aspects of the programming model that were specifically required in the regulation. However, they did not take account of the likely effectiveness of the actions in their decisions to approve operational programmes. This increased the risk of low-effectiveness actions being supported with EU aid. |

|

61. |

Member States instead followed a ‘subsidy approach’ using the eligibility lists to approve programmes in relation to the nature of the proposed expenditure without having to take account of the producer organisations' situations and objectives. |

|

62. |

However, this has not resulted in the uniform application and simplicity that such an approach could offer. The eligibility lists did not set sufficiently clear criteria to guide the expenditure towards the activities that the EU wants to support, with the result of uncertainty and increased costs of control. The coexistence of the programming model required producer organisations to prepare operational programmes and evaluations to comply with the regulations at a significant cost, and for little benefit. |

|

63. |

Operational programmes have, on the whole, resulted in progress being made towards the Council regulation's objectives. However, less than half of the actions financed represented a significant advance from the producer organisations' initial situation towards at least one of the 11 objectives, and can therefore be considered effective. The aid has also been granted for operational programme actions with low effectiveness that achieve little change. In these cases, the aid could be more effective if better targeted |

PART II: PROGRESS MADE BY PRODUCER ORGANISATIONS

|

64. |

Many factors have an impact on the progress made by producer organisations, in addition to the effectiveness of the operational programmes described in Part I. Foremost among these are the activities undertaken by producer organisations and their members that are not financed by operational programmes. Many producer organisations undertake significant investments under Rural Development programmes, for example. Furthermore, other EU aid schemes also support producer organisations, notably the schemes for the withdrawals of surplus production and for the processing of fruit and tomatoes. Also affecting the producer organisations' achievement of the objectives are the strategy followed by the producer organisation, the competition it faces, changing customer requirements and preferences, other EU policies such as for quality and the environment, and even, in the shorter term, weather conditions. |

Have producer organisations made progress towards achieving the objectives set for the aid scheme?

|

65. |

Part I showed that operational programmes have, on the whole, resulted in progress being made towards the Council regulation's objectives. This part of the report examines whether this progress has been reflected in the overall performance of producer organisations. The report first assesses the sample of producer organisations visited during the audit (Text box 17), then considers the Commission's aggregated data at EU level. |

Text box 17Sample characteristics: Producer organisations in the random sample represented 2 % of the total number and 5 % of the turnover of EU producer organisations in 2004.

Sample of producer organisations

|

66. |

The 30 producer organisations visited were asked to demonstrate the progress they had made towards each of the 11 objectives, regardless of whether they had included actions related to those objectives in their operational programmes. This gave a total of 330 cases examined. In 54 % of these, the producer organisation was able to provide evidence to show that it had made progress. In a further 12 % of cases, the conclusion was reached that the producer organisation had probably made progress. A lack of information, particularly on production costs and the stability of prices, explained most of the 16 % of cases where a conclusion could not be made (Diagram 9).

|

|

67. |

Many producer organisations had not followed the objectives ‘organic production’ and ‘promoting products to consumers’, which accounts for most of the 18 % of cases where ‘no progress’ was observed. Relatively little progress had also been made against the objectives of ‘reducing production costs’ and ‘stabilising prices’. Producer organisations explained that they aimed for increasing prices rather than stable prices, although most considered themselves price-takers and could do little to influence the prices they obtained. More important than simply reducing costs was maximising profit, which often involved increasing costs to obtain better quality and added value. Producer organisations also noted that improving environmental practices usually increased costs, without necessarily leading to increased product prices. |

|

68. |

Although the sample results show that most producer organisations made at least some progress towards most of the 11 objectives, this is not sufficient on its own to confirm that the operational programme aid scheme has been effective, because of the influence of the other factors described in paragraph 64. |

Commission data on producer organisations

|

69. |

As shown in Part I, the Commission has not taken the opportunity of exploiting the evaluations made by producer organisations in their final reports to monitor achievement of the operational programme objectives. Furthermore, the Commission has not so far complied with its obligation under the EU Financial Regulation to evaluate the policy. An evaluation study is scheduled to start in 2008, with the results expected in 2009. |

|

70. |

Nevertheless, the Commission does have some information on producer organisations. It obtains data on the quantities of surplus produce withdrawn from the market for which aid is claimed. Since 2000, it has also required information on operational programmes and extended the information collected on producer organisations in an annual statistical report from the Member States. |

|

71. |

The data on operational programmes is limited to breakdowns of the aid paid by categories of expenditure. This indicates what the operational programme aid is being spent on, but not what is being achieved with that aid. |

|

72. |

The Commission requires a more extensive set of data on producer organisations, in particular on their membership, their production and their sales. The Court's checks on the reliability of this information were made difficult, as the Commission does not have a proper management information system for recording the data. The Commission addressed numerous queries to the Member States in 2004 and 2005 on inconsistencies in the data, but did not follow these up. Important data is lacking, particularly for the three largest fruit and vegetable producing Member States: Italy, Spain and France. Analysis of the data is hampered by its incompleteness and the large number of inconsistencies, making it insufficiently reliable for indicating anything other than broad trends. |

|

73. |

The main indicator that can be derived from this data is the share of producer organisations' output in the EU total. This shows how much production is concentrated in producer organisations, which is the overall aim of the policy for the fruit and vegetable sector. It also indicates the broader success of the policy by showing what proportion of fruit and vegetable growers choose to participate in the EU aid scheme. In the 2005 budget documents the Commission set a target of 60 % for this indicator by 2013, with an annual increase. |

|

74. |

Consequently, while it has data on withdrawals and the concentration of supply, the Commission has no indicators to show the progress made by producer organisations towards achieving the other policy objectives such as reducing costs, stabilising prices, improving quality and the environment. |

Analysis of data on withdrawals of surplus produce

|

75. |

The reform of the fruit and vegetable policy in 1996 limited the quantities of surplus produce that could be disposed of under the withdrawals aid scheme, and cut the compensation paid to growers for those withdrawals. The Commission data shows that this has resulted in a substantial reduction in the quantities of withdrawals within the EU aid scheme (Diagram 10). This is in line with the result of the Court's sample that 90 % of producer organisations had reduced withdrawals, or maintained them at zero.

|

|

76. |

One of the objectives set for the operational programme aid scheme was to support measures taken by producer organisations to reduce withdrawals. However, this reduction in withdrawals does not necessarily prove that the operational programme aid has resulted in producer organisations planning and adjusting their production to the demand: producer organisations explained that the reduced aid rates for withdrawals phased in since 1996, together with increased controls, make it no longer worthwhile to claim the aid on their surplus production. |

Analysis of data on the concentration of supply

|

77. |

The policy introduced in 1996 should result in a situation where the aid helps producer organisations to adapt and succeed and other growers are encouraged to join. Both of these factors should increase the turnover of producer organisations, ‘concentrating supply’ in their hands. |

|

78. |

However, the Commission's data shows that the concentration of supply indicator has decreased: producer organisations' share of the total output fell from 40 % in 1999 to 31 % in 2003 (Diagram 11). (The figure shown for 2004 is provisional, as two of the largest Member States, France and Italy, have not reported complete data). While the value of marketed production of the total fruit and vegetable sector increased by 45 % from 1999 to 2003, that of producer organisations increased by only 12 %.

|

|

79. |

As described in paragraph 72, it is not possible to place too much reliance on this data, other than to indicate the broad trend. The 2003 percentage was incorrectly reported by the Commission, for example, because of an error concerning missing data for Greece. While the Court was able to easily find and correct this, the Commission could not demonstrate to the Court that the other data is sufficiently reliable. |

|

80. |

The data also shows the continuing geographical disparity in participation in the aid scheme (Diagram 12). Portugal and Greece, the Member States in which fruit and vegetables represents the largest share of agricultural output, have the lowest participation rates, and have not shown any significant increase. Because of this low participation in producer organisations, only 6 % of Portugal's fruit and vegetable sector receives aid for operational programmes, and 13 % in Greece compared to 80 % in the Netherlands. The design of the aid scheme, which rewards success by paying aid as a percentage of producer organisations' turnover, should create an incentive for smaller producers with lower value production, and with the most need for adapting to the market's increasing quality and environmental standards and concentrated demand, to join producer organisations. The data shows that in some Member States, this has not happened. Instead the scheme has had the result of directing the aid to large producer organisations with high value production.

|

|

81. |

The Commission lacks information on the differences in performance of producer organisations and other growers and so cannot explain why the sector outside producer organisations appears to be growing at a faster rate than producer organisations. |

|

82. |

To explain the lack of progress in the concentration of supply, it is also necessary to find out why growers do not join producer organisations. The Commission has not questioned producers in any systematic way to find the real reasons for this. |

|

83. |

In its reply to the Court's Annual Report 2000, the Commission stated ‘if the majority of producers … prefer not to join an effective producer organisation, they must also take the consequences of their decision. A comparison of the income of those belonging to producer organisations and that of non-members will show which choice was better’. However, the Commission has not monitored the revenues of producer organisation members to be able to make this comparison. |

Rural development

|

84. |

One particular risk, identified by the Commission at an early stage, is that the availability of rural development funding may have undermined the incentive to join or form producer organisations by offering aid similar to operational programmes without requiring the growers to be members of producer organisations (see Text box 18). Although the rural development regulation addressed this issue (by providing that fruit and vegetable producers are not eligible for rural development aid to the extent that similar aid is available under operational programmes), exceptions were allowed. |

Text box 18

Key features of the two aid schemes

Rural development

Operational programmes

Aid only available to producer organisations? No Yes Multiannual programme? Yes Yes Objectives include planning and adapting production to demand, reducing costs, improving quality and environment? Yes Yes Measures proposed, implemented and co-funded by beneficiary? Yes Yes Measures approved and checked by Member State? Yes Yes Evaluation at end of programme? Yes Yes

|

85. |

As a result of these exceptions, Rural Development funding is available for a similar range of activities, from irrigation projects to packaging machinery, for producer organisations and other growers alike. A significant proportion of Rural Development projects under the measures ‘investments in agricultural holdings’ and ‘improving the processing and marketing of agricultural products’ concern fruit and vegetables. |

|

86. |

Despite the potential importance of the risk of the Rural Development programmes undermining producer organisations, which are the cornerstone of the EU's policy for fruit and vegetable producers, the Commission has not checked the operation of Member States' procedures for ensuring consistency, or collected information or undertaken any assessment of the extent to which this may have occurred. |

CONCLUSIONS

The effectiveness of operational programmes

Has the aid scheme been implemented in a way to ensure that operational programmes are likely to be effective?

|

87. |

Member States have focused on the eligibility of operational programme actions by the nature of the expenditure, without also considering whether they represent a step forward for the producer organisation towards achieving the operational programme objectives. As a result, Member States' procedures do not ensure that all operational programme actions are likely to be effective. Member States have not applied the sound financial management principle of effectiveness in approving operational programmes. Commission checks have focused on compliance with the criteria for the eligibility of expenditure and not on whether the Member State procedures for approving and monitoring operational programmes operate in a way to ensure that the programmes are likely to be effective. |

|

88. |

The aid scheme has been costly to implement for the Member State administrations and for producer organisations. The programming elements required by the regulations have been followed nominally, at a significant cost but without real benefits. The criteria for the eligibility of expenditure were not clear, resulting in uncertainty and an increased need for controls to ensure compliance. |

Have the measures financed in operational programmes been effective?

|

89. |

Almost half of the actions financed in operational programmes resulted in a significant advance from the producer organisations' initial situation towards at least one of the 11 objectives, and can therefore be considered effective. |

|

90. |

Member States have also granted the aid for operational programme actions with low effectiveness that achieve little change. In these cases, the aid could be more effective if better targeted. |

Progress made by producer organisations

Have producer organisations made progress towards achieving the objectives set for the aid scheme?

|

91. |

Producer organisations have adapted to the changing demand and made progress towards the objectives set in the Council regulation. Operational programmes have contributed to this, but are not the only factor. Rural development funding is also available to producer organisations, and to other fruit and vegetable growers, to support similar activities, with similar objectives to operational programmes. Market forces put pressure on all producers to meet higher environmental standards, improve product quality and control costs. Consequently, some of these effects may have been observed even without the operational programme aid. |

|

92. |

Despite the availability of EU aids to members of producer organisations, the majority of growers in the main fruit and vegetable producing Member States choose not to participate. The policy has so far not succeeded in concentrating supply in most Member States. When the Court reported on the fruit and vegetable sector in 2000, around 40 % of the EU's fruit and vegetable production was marketed by producer organisations. The Commission's latest data shows that this has fallen to about one-third. On current trends, the Commission's target for producer organisations to reach a 60 % share of the total value of marketed production by 2013 will not be achieved. |

|

93. |

The Commission has not assessed the reasons for this lack of participation in producer organisations, including whether Member States' procedures have been sufficient to ensure that Rural Development funding has not undermined the incentive for growers to join. |

RECOMMENDATIONS

|

94. |

The conclusions presented above show that the overall policy objective of concentrating supply in producer organisations has not been achieved in most Member States, and the Commission lacks the information on the reasons for this that would be necessary for reviewing the policy. Pending a review of this, which should take account of the results of the evaluation of producer organisations due in 2009, the Commission should bring forward proposals to make the aid scheme for operational programmes simpler and more effective. |

Make the aid for operational programmes simpler and more effective

|

95. |

The Commission should consider the merits of the following alternative approaches to improve the operational programme aid scheme:

|

|

96. |

The Commission should improve its data collection on operational programmes and producer organisations, focusing on a few key indicators that will allow it to monitor the effectiveness of the aid scheme and provide useful information for periodic evaluation. |

Better target the policy to achieve the overall objectives of concentration and adaptation

|

97. |

The Commission should use the evaluation planned for 2009 to obtain a better understanding of the reasons for the lack of progress in the concentration of supply in producer organisations. It should assess whether producer organisations have improved the situation of their members in relation to other growers, and how the policy coexists with rural development. |

|

98. |

If these studies confirm that producer organisations are an effective mechanism for strengthening the position of growers, the policy should be better targeted to achieve this. The Commission should propose changes to encourage membership of producer organisations, particularly in the main fruit and vegetable producing Member States. The Commission should also consider if the policy aim of adapting production to the changing market demands could be better achieved if the aid was targeted at those who have the most need of adaptation by introducing new criteria, in addition to turnover, for allocating funding to producer organisations. |

Question the policy of encouraging producer organisations

|

99. |

The Commission should also use the planned evaluation to establish whether the benefits of concentration of supply achieved by the policy are sufficient to compensate for the inequality caused by limiting the aid to one particular structure of fruit and vegetable growers: producer organisations. |

|

100. |

A policy choice was made in 1996 to exclude growers who are not in producer organisations from the benefits of the EU aid. If the Commission cannot demonstrate that the support for producer organisations produces real gains in terms of strengthening their position in the market place, the rationale for excluding other producers from the EU aid should be questioned and the Commission should reconsider this mechanism for supporting the EU's fruit and vegetable growers. |

This Report was adopted by the Court of Auditors in Luxembourg at its meeting of 28 June 2006.

For the Court of Auditors

Hubert WEBER

President

(1) Growers who ‘withdraw’ surplus fruit and vegetables from the market to support prices (usually by destroying the produce) are paid compensation from the EU budget.

(2) Court of Auditors — Annual Report concerning the financial year 2000 (OJ C 359, 15.12.2001).

(3) Council Regulation (EC, Euratom) No 1605/2002 of 25 June 2002 (OJ L 248, 16.9.2002, p. 1).

(4) Council Regulation (EC) No 2200/96 of 28 October 1996 on the common organisation of the market in fruit and vegetables (OJ L 297, 21.11.1996, p. 1). and Commission Regulation (EC) No 1432/2003 of 11 August 2003 laying down detailed rules for the application of Council Regulation (EC) No 2200/96 regarding the conditions for recognition of producer organisations and preliminary recognition of producer groups (OJ L 203, 12.8.2003, p. 18).

(5) Some exceptions are allowed in producer organisations' operational programmes. See paragraph 42.

(6) Luxembourg has no producer organisations.

(7) Regulation (EC) No 2200/96.

(8) Commission Regulation (EC) No 411/1997 of 3 March 1997(OJ L 62, 4.3.1997, p. 9), replaced by Commission Regulation (EC) No 1433/2003 of 11 August 2003 laying down detailed rules for the application of Council Regulation (EC) No 2200/96 as regards operational funds, operational programmes and financial assistance (OJ L 203, 12.8.2003, p. 25).

(9) The Court has informed Member States of the specific findings that concern them.

(10) Member States commented that, according to the deadlines set in the implementing regulation, final reports are received after they have already approved the next operational programme for the producer organisation concerned. Although the regulation has been revised several times since 1997, this inconsistency has not been amended. Evaluation reports could be required earlier in the final year of the programme, simultaneous with the request for the following programme, for example.

(11) This concerns the national paying agency in particular.

(12) Annual checks of at least 20 % of producer organisations representing 30 % of expenditure.

(13) The Commission disallowed this expenditure in the Clearance of Accounts process on the basis that the programme did not have several objectives as required by the regulation. In 2002, the Spanish authorities limited spending on recyclable packaging to a maximum 35 % of each operational programme to ensure equal treatment for all Spanish producer organisations.

ANNEX

AUDIT CRITERIA FOR THE APPROVAL OF EFFECTIVE OPERATIONAL PROGRAMMES

|

Compliance with the Regulation |

Additional performance audit criteria |

||||||||||||

|

Producer organisation's initial situation |

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Operational programme objectives |

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Operational programme actions |

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Final reports (end-of-programme evaluations by the producer organisation) |

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Approval of operational programmes |

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

THE COMMISSION'S REPLIES

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

|

I. |

The scheme provides financial support for the operational programmes of fruit and vegetable growers who market their products via producer organisations. It was introduced to help a fragmented sector improve its position in a market dominated by a relatively small number of large purchasers. |

|

III. |

The Commission recognises the Court's concerns. However, some progress towards the related objectives could either be clearly seen or assumed in over 70 % of cases the Court audited (see paragraph 54). The Commission introduced eligibility lists, which (as far as was reasonably possible) clearly set out what could be funded. It is for the national authorities to ensure that the programmes they approve harmonise not only with these guidelines, but also with the overall objectives set by the regulations. Member States decide on their own detailed administrative arrangements and the Commission verifies that these are in compliance with the regulations. |

|

IV. |

During its various Clearance of Accounts missions and desk audits, the Commission paid particular attention to ensuring that Member States' systems of management and control offer reasonable assurance that expenditure declared conforms to the regulatory requirements. This led, where appropriate, to assessments of compliance of the procedures for approving and monitoring operational programmes. Weaknesses are followed up via the Clearance of Accounts process and give rise, where necessary, to financial corrections against the Member State concerned. Under the shared management system, Member States are primarily responsible for evaluating and controlling the effectiveness of any given action. The Commission regularly discusses the functioning of the aid scheme, including issues related to effectiveness, with Member States in the Management Committee meetings and bilaterally. The issue of effectiveness will be addressed further in the impact assessment and the forthcoming evaluation, where the Court's observations will be taken into account. Moreover, more attention will be paid in the forthcoming reform to making the requirements on reporting and monitoring by Member States more effective tools for them in their assessment of the effectiveness of the policy. |

|

V. |

The Commission is pleased to note that the Court's findings give a positive global picture of progress made by producer organisations thanks to Community support. It notes also that nearly three-quarters of the actions the Court tested showed some progress towards the programme objectives. The Commission considers that even if an action may not appear effective in achieving a significant advance towards one of the objectives specified in Article 15(4) of the Council Regulation, the aid should be considered effective in terms of improving producers' incomes through improving their competitiveness, which is one of the overall policy aims. However, it does agree that the aid can be more effective if better targeted, and it will address this issue in the on-going impact assessment. |

|

VI. |

In addition to the sources of information cited by the Court, indirect indicators exist as far as the objective of improving quality (the increasing number of geographic indicators and quality labels related to fruit and vegetable products) is concerned, although these do not show specifically the progress made by producer organisations. |

|

VII. |

The Commission shares the Court's concerns regarding achievement of the 60 % target. However, it considers that the picture is more complex. The instrument has been used in very different ways in different Member States, and results are not uniformly negative. Other more encouraging data should be highlighted, in particular the formation of Associations of Producer Organisations (APOs) and the emergence of big producer organisations in some Member States since the reform of the policy in 1996 (in particular BE, NL and IT), some of which are already able to counterbalance the bargaining power of big retailers. This policy approach, having in mind the increased market access implied by the Doha Development Agenda and the increasing concentration of the demand side, is still the best instrument to try to achieve a better balanced chain (between producers and consumers). One of the aims of the forthcoming reform is to address the weaknesses and to reinforce the available instruments, in particular by favouring mergers between producer organisations, Associations of producer organisations, cooperation between producer organisations, and producer organisations with a transnational dimension. |

|

VIII. |

The Commission is carrying out an impact assessment in preparation for the CMO reform proposal to be presented later in 2006. It agrees with the aims expressed in the Court's recommendations and will, as part of the impact assessment, explore how best they can be achieved. |

|

IX to XI. |

The Commission will improve its capacity to collect data and develop relevant indicators. To address the data reliability issue, DG AGRI is starting an IT project in 2006 to have a proper database in place, starting in 2007. The scope of the evaluation and the evaluation questions will be formulated during the preparation of the tender specifications. The observations of the Court will be taken into account. |

INTRODUCTION

|

1. |

Council Regulation (EC) No 2200/96 foresees several destinations for products withdrawn from the market: free distribution to charitable organisations; schools; non-food purposes; animal feed; processing industries; and (but not exclusively) compost or biodegradation under environmentally strict conditions. |

|

5. |

The Common Market Organisation (CMO) was last reformed in 1996, prior to the entry into force of the more detailed requirements of the Financial Regulation in 2002. However, given the evolution of the Financial Regulation, the objectives will be reconsidered in the next CMO reform, announced for the end of 2006. |

PART I: EFFECTIVENESS OF OPERATIONAL PROGRAMMES

|

20. |

The Commission recognises its final responsibility for the sound financial management of the EU budget under Articles 274 of the EC Treaty and 179 of the Euratom Treaty. The results of the application of clearance-of-accounts procedures and other financial corrections mechanisms, established under the provisions of Article 53(5) of the Financial Regulation are part of this framework. Furthermore, Council Regulation (EC) No 1290/2005 on the financing of the Common Agricultural Policy requires directors of Paying Agencies to sign a declaration of assurance (DAS), mirroring in shared management the declaration of assurance issued by the Directors-General of the Commission. |

|

21. |