EUROPEAN COMMISSION

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Brussels, 15.9.2015

SWD(2015) 169 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

Situation of young people in the EU

Accompanying the document

Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions

Draft 2015 Joint Report of the Council and the Commission on the implementation of the renewed framework for European Cooperation in the youth field (2010-2018)

{COM(2015) 429 final}

{SWD(2015) 168 final}

8. VOLUNTARY ACTIVITIES

|

EU Youth Indicators

|

|

|

Participation of young people in organised voluntary activities

|

Figure 8-A

|

|

Voluntary activities aimed at changing young people's local communities

|

Figure 8-D

|

|

Young people volunteering abroad

|

Figure 8-F

|

|

Young people receiving a certificate or diploma for voluntary activities

|

Figure 8-H

|

8.1. Introduction

Participating in voluntary activities greatly contributes to a young person's human capital and personal development. The personal benefits volunteering brings to young people are numerous. Research has shown how it helps to discourage young people from leaving school prematurely and improves their self-confidence, sense of social responsibility, and level of psychological wellbeing (). In terms of the development of human capital, volunteering provides young individuals with effective opportunities for non-formal learning which enhance their personal and professional skills and can greatly contribute to their employability. The improvement of interpersonal skills, communication skills, knowledge, organisational and managerial skills, fundraising, technical and office skills are examples of practical gains reported by young volunteers ().

Volunteering also represents an important contribution to the promotion of social and economic cohesion. Indeed, by engaging in projects to tackle current social problems, young volunteers become key agents of social reform and develop a sense of belonging in and ownership of their community. More specifically, peer-mentoring (voluntary mentoring by a young person who has lived through similar experiences) has been shown to be effective in helping young people at risk of exclusion ().

This chapter provides an overview of young people's participation in voluntary activities; it examines recent trends in terms of participation rates, areas of activity and the tendency for young people to undertake voluntary work abroad. The second part of the chapter highlights some of the key factors in supporting youth volunteering and encouraging more widespread participation.

8.2. Youth participation in voluntary activities

According to the results of the Flash Eurobarometer 'European Youth' conducted in 2014, around one young European in four has engaged in voluntary activities (Figure 8-A). In some countries (Denmark, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom), this percentage rises to over one in three, while other countries register much lower rates of participation (in particular, Bulgaria, Greece and Sweden). At the European level, figures have remained stable since 2011, although some variations have occurred in certain Member States. For example, the share of young people participating in volunteering has halved in Bulgaria and significantly diminished in Romania, while it has increased in Italy and Cyprus.

Figure 8-A: EU Youth Indicator: Participation of young people (aged 15-30) in organised voluntary activities, by country, 2011 and 2014

|

EU youth indicator

|

%

%

|

Note: the question was: 'In the last 12 months, have you been involved in any organised voluntary activities?'. Base: all respondents. EU-27 (2011) and EU-28 (2014)

Source: Flash Eurobarometer 319, 'Youth on the Move', 2011 and Flash Eurobarometer 408, 'European Youth', 2014

The younger groups of young people tend to be more active in voluntary activities (Figure 8-B). Comparison with rates of participation in the general population does not signal substantial differences between generations, nor does comparison between men and women ().

Figure 8-B: Participation of young people (aged 15-30) in organised voluntary activities, EU-28 average, by age group, 2014

|

%

%

|

Note: the question was: 'In the last 12 months, have you been involved in any organised voluntary activities?'. Base: all respondents.

Source: Flash Eurobarometer 408, 'European Youth', 2014

|

|

|

|

15-19

|

20-24

|

25-29

|

|

|

Volunteering is often inspired by previous experiences of engagement in the community. Participation in services organised by families, schools, religious communities, and sporting organisations have been indicated as a strong factor in fostering youth involvement in voluntary projects (). Indeed, data show that young people seem to be more active in volunteering when they participate in other collective political and cultural activities (Figure 8-C). In particular, engagement in a youth club is very closely related to involvement in voluntary experiences.

Figure 8-C: Participation of young people (aged 15-30) in organised voluntary activities, EU-28 average, by participation in other activities, 2014

|

%

%

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note: the questions were: 'In the last 12 months, have you been involved in any organised voluntary activities?' and 'In the last 12 months, have you participated in any activities of the following organisations? (Multiple answers possible)'. Base: all respondents.

Source: Flash Eurobarometer 408, 'European Youth', 2014

|

|

|

At least one political or cultural activity

|

A

youth club

|

None

|

|

|

The majority of those involved in voluntary activities choose projects and services aimed at bringing benefits to their local community (Figure 8-D). The proportion of young Europeans who have undertaken these types of activity have registered an increase since 2011, especially in Spain, France and Poland.

Figure 8-D: EU Youth Indicator: Share of young people (aged 15-30) who undertook voluntary activities aimed at changing their local communities, by country, 2011 and 2014

|

EU youth indicator

|

%

%

|

Note: the question was: 'Were these voluntary activities aimed at changing something in your local community?'. Base: all respondents. EU-27 (2011) and EU-28 (2014)

Source: Flash Eurobarometer 319, 'Youth on the Move', 2011 and Flash Eurobarometer 408, 'European Youth', 2014

Despite the local focus favoured by many young volunteers, others are involved in charitable activities with a particular focus on humanitarian and development aid – causes which have a definite global dimension (Figure 8-E). Education, training and sports are also popular activities. Conversely, other issues such as the environment, animal welfare, as well as political, cultural and religious causes seem to have less appeal.

Figure 8-E: Main themes of the voluntary activities undertaken by young people (aged 15-30), EU-28 average, 2014

|

|

|

%

|

|

Charity, humanitarian and development aid

|

|

|

|

Education, training or sport

|

|

|

|

Culture or art

|

|

|

|

Human rights

|

|

|

|

Religion

|

|

|

|

Animal welfare

|

|

|

|

Climate change or the environment

|

|

|

|

Politics

|

|

|

|

|

|

%

|

Note: the question was: 'In the last 12 months, which of the following were your voluntary activities related to? (Multiple answers possible)'. Base: all respondents.

Source: Flash Eurobarometer 408, 'European Youth', 2014

Young volunteers are mostly engaged in activities within their own country, a finding in line with their propensity to engage in actions which benefit their local community, as illustrated above. Although young people's international mobility has increased over recent years bringing many young Europeans to live, study and work in other European countries, as discussed in the first chapter of this report, serving in cross-border voluntary organisations does not seem to be a major reason for young people to leave their country of origin: only around 2% of individuals in the European Union report having volunteered abroad (Figure 8-F).

Figure 8-F: EU youth indicator: Share of young people (aged 15-30) going abroad to do voluntary work, by country, 2011 and 2014

|

EU youth indicator

|

%

%

|

Note: the question was: 'Have you ever had the opportunity to stay abroad for the purpose of volunteering?'. Base: all respondents. EU-27 (2011) and EU-28 (2014)

Source: Flash Eurobarometer 319, 'Youth on the Move', 2011 and Flash Eurobarometer 408, 'European Youth', 2014

Even in those countries where the percentage of young volunteers going abroad is highest (Bulgaria, Denmark, Ireland, Lithuania, Hungary, the Netherlands) the figure does not exceed 6% of the total number of respondents. Significant variations have occurred in several countries since 2011. While Belgium, Ireland, Luxembourg and the United Kingdom have experienced a sharp decline in the number of young people going abroad to volunteer, Lithuania, Hungary, and the Netherlands have seen a substantial increase.

Overall, data show that participation in voluntary activities either at home or abroad involves around a quarter of young Europeans. While this figure is encouraging, the potential for non-formal learning and personal growth attached to voluntary work can be further appreciated and exploited by young generations. To this end, it is interesting to shed some light on the barriers which prevent more widespread access to voluntary projects.

8.3. Encouraging youth participation in voluntary activities

Two of the most important factors which facilitate the participation of young people in voluntary activities are the possibility of receiving financial compensation for the expenses incurred during their period of volunteering, and the right to obtain formal recognition of the personal and professional experience acquired ().

|

Almost one in three young volunteers does not receive any contribution towards the living and travelling costs incurred.

|

The fact that the costs of volunteering activities must usually be borne by the individual concerned can represent a powerful disincentive for those who do not possess enough personal or family resources to bear the financial burden arising from a sustained period of non-remunerated work. This is even more crucial when considering volunteering abroad, which generally involves higher personal expenses. Furthermore, leaving the country of origin often means the loss of social benefits (such as unemployment benefits) and insurance, which can mean that going abroad is even more difficult (). In this respect, contributions to expenses incurred such as living and travel costs can open volunteering up to a wider audience, particularly to individuals from to disadvantaged social groups who, perhaps, could benefit most in terms of improving their educational and professional skills.

Available data from the Eurobarometer survey of 2014 indicate that half of young volunteers in the European Union have incurred expenses to cover living and travel costs during their volunteering experiences (Figure 8-G).

Figure 8-G: Contributions towards living expenses received by young people (aged 15-30) during voluntary activities, EU-28, 2014

|

|

|

%

|

|

You haven't incurred any expenses

|

|

|

|

You incurred expenses,

but you haven't received any contributions

|

|

|

|

You incurred expenses and you have received contributions from organisation(s) or group(s) of people you have volunteered for

|

|

|

|

You incurred expenses and you have received contributions from a government or other public body

|

|

|

|

You incurred expenses and you have received contributions from family or relatives or friends

|

|

|

|

You incurred expenses and

you have received contributions from a commercial organisation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note: the question was: 'Have you incurred any expenses in relation to your voluntary activities and have you received any contributions for these expenses?'. Base: all respondents who have participated in a voluntary activity.

Source: Flash Eurobarometer 408, 'European Youth', 2014

Almost one third of young volunteers have not received any contributions towards expenses incurred. This finding might be linked with the propensity of young volunteers to engage in activities for the benefit of their local communities instead of taking up opportunities to volunteer abroad. Amongst those who have received support, the majority did so from the organisations for which they volunteered. Contributions from public bodies and families and/or friends account for only a small percentage.

Formal recognition of volunteering experiences also plays a major role in encouraging young people to engage (). As mentioned above, by participating in voluntary activities, volunteers acquire skills or enhance their personal and professional capabilities through non-formal learning. Such skills can later be useful in either continuing education or entering the labour market, especially when they are formally recognised through qualifications that can enrich their curriculum vitae.

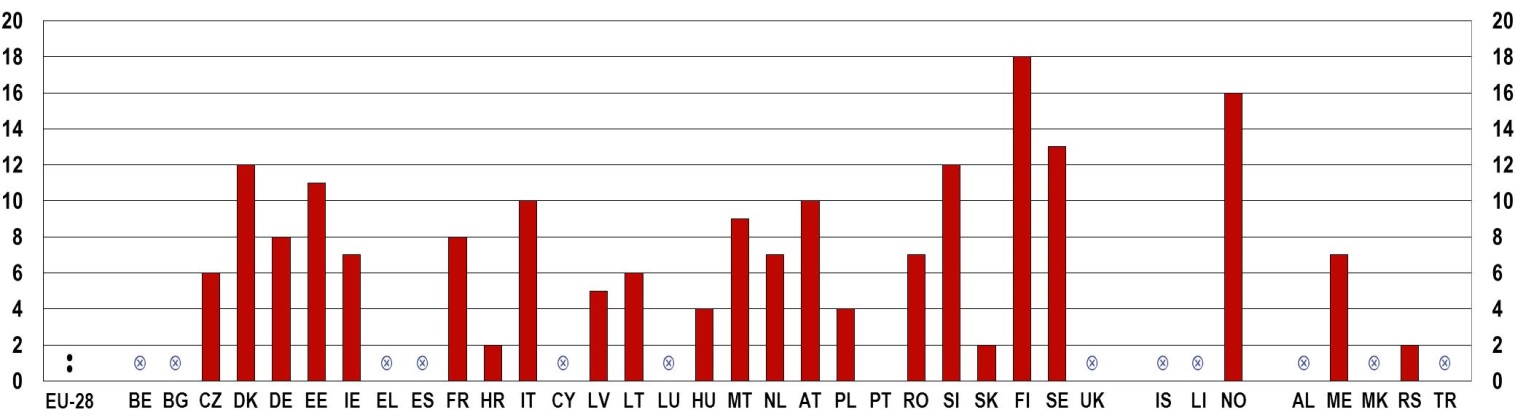

On average, only a quarter of young people who have participated in voluntary activities have received a certificate or diploma formally recognising their experience and the skills they have demonstrated, a percentage that has slightly increased since 2011 (Figure 8-H).

Figure 8-H: EU Youth Indicator: Share of young people (aged 15-30) who received a certificate or diploma for their voluntary activities, by country, 2011 and 2014

|

EU youth indicator

|

%

%

|

Note: the question was: 'Did you receive a certificate, diploma or other formal recognition for your participation in these voluntary activities?'. Base: all respondents. EU-27 (2011) and EU-28 (2014)

Source: Flash Eurobarometer 319, 'Youth on the Move', 2011 and Flash Eurobarometer 408, 'European Youth', 2014

|

Only a quarter of young people who have participated in voluntary activities have received a certificate or diploma formally recognising their experience and the skills they have demonstrated.

|

This percentage has grown significantly in Denmark, France, Latvia and Luxembourg, while it has declined in the Czech Republic. The latter is one of the European countries where, in general, a very small proportion of young people receive formal recognition for their volunteering experience; the others are Belgium, France, the Netherlands, Slovakia and Sweden. The highest percentages are found in Germany, Cyprus, Luxembourg, Poland and Romania.

Recognition of the skills acquired through volunteering can be particularly complicated when the activity has been carried out in a country different from the one where the individual wishes to either continue his/her education or seek employment, due to differences between national validation systems (). The combination of challenges such as these can make volunteering abroad all the more difficult.

9. CULTURE AND CREATIVITY

|

EU Youth Indicators

|

|

|

Share of young people who have undertaken

one or more cultural activities at least once in the preceding 12 months

|

Figure 9-A

|

|

Share of young people who have undertaken

an amateur artistic activity at least once in the preceding 12 months

|

Figure 9-B

|

|

Share of young people who have been active in

a sports club, youth club or cultural organisation at least once in the preceding 12 months

|

Figure 9-C

|

|

Share of young people (aged 15-30) who say that they have been active in a sports club,

youth club or cultural organisation at least once in the preceding 12 months

|

Figure 9-E

|

|

Daily computer and Internet use among young people

|

Figure 9-G

|

9.1. Introduction

Participation in cultural, artistic and recreational activities is a vital part of young people's lives. Besides providing an opportunity for enjoyment and stimulating creativity, involvement in these activities is an important way for young people to develop their personal, social and professional skills. Cultural engagement can provide them with the opportunities to acquire non-formal competencies that can be used in further education and vocational training as well as in professional development. In addition, involvement in cultural and artistic activities facilitates socialisation and integration into the community and therefore encourages active participation and social inclusion ().

The development and increased use of new technologies applied to social communication and cultural enjoyment rapidly transform the way young people experience culture and the arts. This therefore offers an interesting perspective to observe what the general trends are in the way young people get involved in cultural activities and to what extent they have taken advantage of existing opportunities to be active participants in creative experiences.

The chapter firstly presents data on youth participation in a variety of cultural and recreational activities, and explores the most widespread obstacles to access to culture. The second part deals with young people's use of the new information and communications technologies for cultural purposes, as well as more generally in terms of frequency of use and level of skills. The final section addresses young people's views about creativity and looks at the types of creative activities they engage in online.

9.2. Cultural participation

|

Between 2011 and 2014, a general decline in youth participation in cultural and artistic activities has taken place.

|

Results from two Eurobarometer surveys, conducted in 2011 and 2014 respectively, shed light on the levels of and variations in young people's participation in various cultural activities. The main trend that emerges is a general decline in the extent to which young Europeans have taken part in these experiences over the three years in question. For each of the activities examined (visits to historical monuments, museums and galleries, going to the cinema or concerts, or attending live performances), the proportion of young individuals who have participated at least once in the 12 months prior to the survey has declined in the majority of countries (Figure 9-A).

Figure 9-A: EU Youth Indicator: Share of young people (aged 15-30) who have undertaken one or more of the following cultural activities at least once in 12 months preceding the survey, by country, 2011 and 2014

a) Visited historical monuments (palaces, castles, churches, gardens, etc.), museums or galleries

|

EU youth indicator

|

%

%

|

b) Been to the cinema or a concert

|

EU youth indicator

|

%

%

|

c) Been to a theatre, a dance performance or an opera

|

EU youth indicator

|

%

%

|

Note: the question was 'In the last 12 months, have you undertaken any of the following cultural activities?' (MULTIPLE ANSWERS POSSIBLE). Base: all respondents. EU-27 (2011) and EU-28 (2014)

Source: Flash Eurobarometer 'Youth on the Move' 319, 2011 and Flash Eurobarometer 'European Youth' 408, 2014

On average, the strongest decline is registered in the proportion of young people going to the theatre, dance performance or opera (-14 %), followed by going to the cinema and concerts (-9 %) and visiting historical monuments, museums and galleries (-6 %).

The decline in participation is significant and consistent across the three types of activity amongst young people in Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania and Slovenia. Drops in the share of young people going to the cinema and concerts and to the theatre, dance performances and opera is notable also in Greece, Italy, Cyprus, and Malta. Similar reductions in the proportion of young people going to live performances can be observed in Germany, Ireland and Austria.

The declining trend in participation in cultural activities is similar to that for undertaking an amateur artistic activity. The most significant fall in the level of involvement is registered again in Bulgaria, Greece, Italy, Cyprus, Hungary, Romania and Slovenia (Figure 9-B).

Figure 9-B: EU Youth Indicator: Share of young people (aged 15-30) who have undertaken an amateur artistic activity at least once in the 12 months preceding the survey, by country, 2011 and 2014

|

EU youth indicator

|

%

%

|

Note: the question was 'In the last 12 months, have you participated in an amateur artistic activity (playing a musical instrument, singing, acting, dancing, writing poetry, photography, film making)?'. Base: all respondents. EU-27 (2011) and EU-28 (2014)

Source: Flash Eurobarometer 'Youth on the Move' 319, 2011 and Flash Eurobarometer 'European Youth' 408, 2014

In addition, a smaller proportion of young people have joined cultural and recreational organisations, such as youth organisations, sports clubs and cultural associations over the last three years. Again, the most notable decrease has taken place in the same group of countries as above (Bulgaria, Ireland, Greece, Italy, Hungary, Romania and Slovenia) to which Estonia, Lithuania, Austria, and Slovakia must also be added (Figure 9-C).

Figure 9-C: EU Youth Indicator: Share of young people (aged 15-30) who have been active in a sports club, youth club or cultural organisation at least once in the 12 months preceding the survey, by country, 2011 and 2014

a) Sport club

|

EU youth indicator

|

%

%

|

b) A youth club, leisure-time club or any kind of youth organisation

|

EU youth indicator

|

%

%

|

c) A cultural organisation

|

EU youth indicator

|

%

%

|

Note: the question was 'In the last 12 months, have you participated in any activities of the following organisations?'. Base: all respondents. EU-27 (2011) and EU-28 (2014)

Source: Flash Eurobarometer 'Youth on the Move' 319, 2011 and Flash Eurobarometer 'European Youth' 408, 2014

The consistent drop in figures for all indicators in the EU in general, and in several Member States in particular, hints at the existence of general underlying causes for the decline in the numbers of young Europeans becoming involved in cultural activities. It seems likely that the economic crisis affecting the European continent over recent years, which has exacted a high economic and social price in several countries, has played a part. Plummeting levels of employment and the growing financial insecurity suffered by many Europeans, in particular the younger generation, have meant that many do not have the means to enjoy cultural events (). As discussed in the chapter on Social Inclusion, the last few years have seen a dramatic worsening in the social conditions of significant segments of the youth population, which reflects in all areas of life.

The findings of a recent survey exploring the main reasons for young people not participating in cultural activities is in line with this argument. Over a third of respondents felt the cost of going to the cinema or concerts (the most popular forms of entertainment for young audiences) to be the most important obstacle (Figure 9-D). For other cultural activities such as the theatre, dance performances, and visits to museums and monuments, a lack of interest and time appear as the main reasons for not taking part.

Figure 9-D: Reasons for young people (aged 15-24) not attending various cultural activities in the 12 months preceding the survey, EU-28 average, 2013

|

%

%

|

|

|

|

|

Too

expensive

|

Lack of

time

|

Lack of

interest

|

Lack of

information

|

Limited choice or poor quality of this activity in the place where you live

|

|

|

|

Concerts

|

|

Cinema

|

|

Theatre

|

|

Ballet

|

|

Monument

|

|

Museum

|

Note: the question was 'For each of the following activities, please tell me why you haven't done it or haven't done it more often in the last 12 months'. Base: all respondents.

Source: Special Eurobarometer 399, 'Cultural access and participation', 2013

In terms of gender, being active in a sports club is the activity where differences between young men and women are most apparent (Figure 9-E). According to Eurobarometer data, men tend to participate more than women, a result in line with men's higher propensity to play sports, as illustrated in the chapter on Health and Well-being.

Figure 9-E: EU youth indicator: Share of young people (aged 15-30) who have been active in a sports club, youth club or cultural organisation at least once in the 12 months preceding the survey, by sex, EU-28 average, 2014

|

EU youth indicator

|

%

%

|

Note: the question was 'In the last 12 months, have you participated in any activities of the following organisations?'. Base: all respondents.

Source: Flash Eurobarometer 'European Youth' 408, 2015

The trends discussed so far pertain to certain cultural activities that are not immediately influenced by the growth of new developments in information and communications technology. Yet, the latter play an ever larger role in shaping the ways people can access and enjoy cultural experiences, especially young people who are the most receptive to the developments these new media bring about. The next section will therefore address the extent and nature of use of these media by young Europeans, in general, and as a medium for accessing cultural experiences.

9.3. Young people and their use of ICT

According to the results reported by a Eurobarometer survey from 2013, young people are the group in the general population which uses the internet the most for cultural purposes (Figure 9-F).

Figure 9-F: Share of the population using the Internet for cultural purposes at least once a week, by age, EU-28 average, 2013

|

%

%

|

Note: the question was 'How often do you use the Internet for cultural purposes like, for instance, searching for cultural information, buying cultural products or reading articles related to culture?'. Base: all respondents.

Source: Special Eurobarometer 399 'Cultural access and participation', 2013

|

|

|

15-24

|

25-39

|

40-54

|

55+

|

|

|

|

Daily use of computers by young people aged 16-24 has slightly declined while access to the Internet has grown in almost all Member States.

|

As in the case of political participation (discussed in Chapter 7), young people have been the first to apply communication technologies to their social interactions. This also reflects on the way they access, enjoy and initiate cultural experiences. To this end, access to and proficiency in the use of computers and the Internet are essential. According to data collected by Eurostat, between 2011 and 2014 the level of use of computers and the Internet amongst young Europeans have followed different trends (Figure 9-G). While levels of daily access to computers have generally decreased in the majority of countries, rates of daily use of the Internet have increased. This situation can be explained by the growth in alternative channels to access the Internet such as mobile or smart phones which are heavily used by young people (). They probably have partially replaced the desktop type of personal computer as a main gateway to online connectivity at home.

The biggest decreases in daily computer use are observed in Spain, Croatia, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Finland and Sweden. Conversely, higher rates have been recorded in the Czech Republic, Greece, Malta, and especially in Romania. These latter countries (Czech Republic, Greece, Malta and Romania) are, together with Hungary and Portugal, also those where the proportion of young people who have daily access to the Internet has increased the most since 2011.

Figure 9-G: EU Youth Indicator: Daily computer and Internet use among young people (aged 16-24), by country, 2011 and 2014

a) Daily computer use

|

EU youth indicator

|

%

%

|

b) Daily Internet use

|

EU youth indicator

|

%

%

|

Source: Eurostat [isoc_ci_cfp_fu]

On average, the proportion of young people with a good level of computer skills (measured by Eurostat as the ability to perform five or six tasks, that means all or almost all tasks from a list of six selected computer-related activities in the survey) has remained stable at around 45 % in Europe (Figure 9-H). Significant improvements have been observed in some countries (Bulgaria, Germany, Estonia, France, Malta, Portugal and Poland), while negative trends appear in particular in Croatia, Hungary, Austria and Sweden.

Figure 9-H: Share of young people (aged 16-29) who have carried out at least five of the specified computer-related activities, by country, 2011 and 2014

%

%

Note: the computer related activities surveyed and used for skills aggregation were: copying or moving a file or folder; using copy and paste tools to duplicate or move information within a document; using basic arithmetic formulas in a spreadsheet; compressing (or zipping) files; connecting and installing new devices, e.g. a modem; writing a computer programme using a specialised programming language.

Source: Eurostat [isoc_sk_cskl_i]

Eurostat data also show that the gap in the use of ICT between young people who have acquired different levels of education has reduced. Indeed, the decline in the daily use of computers recorded since 2011 has been lower among young people with a low level of formal education than for those with higher level formal qualifications (Figure 9-I-a). In parallel, the growth in the share of young people having daily access to the Internet has been more remarkable amongst those who have only a low level of educational attainment (Figure 9-I-b).

Figure 9-I: Daily computer and Internet use among young people (aged 16-24) by level of education, EU-28 average, 2011 and 2014

|

a) Computer daily use

|

b) Internet daily use

|

|

%

%

|

%

%

|

|

|

|

|

A

|

Low-level formal education

|

B

|

Medium-level formal education

|

C

|

High-level formal education

|

Note: According to Eurostat's Statistics Manual, a low level of formal education corresponds to no formal education or the completion of primary or lower secondary education only (corresponding to ISCED 0, 1 or 2); medium-level formal education corresponds to upper secondary education (ISCED 3 and 4); and high-level formal education corresponds to tertiary education (ISCED 5, 6, 7 or 8). For data on educational attainment based on the EU Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) the International Standard Classification of Education 2011 (ISCED 2011) is applied as from 2014. Up to 2013 ISCED 1997 is used

Source: Eurostat [isoc_ci_ifp_fu]

However, evident disparities still exist in terms of the computer skills demonstrated by high- and low-attaining young people. On average, almost twice as many young individuals who have attained a high level of formal education possess good computer skills compared to individuals with a lower level of attainment (Figure 9-J). The biggest differences between the two groups are found in Belgium, Bulgaria, Ireland, Greece, Malta and Romania.

Figure 9-J: Share of young people (aged 16-24) who have carried out at least five computer related activities, by country and level of education, 2014

%

%

|

Level of formal education:

|

|

Low

|

|

Medium

|

|

High

|

Note: According to Eurostat's Statistics Manual, a low level of formal education corresponds to no formal education or the completion of primary or lower secondary education only (corresponding to ISCED 0, 1 or 2); medium-level formal education corresponds to upper secondary education (ISCED 3 and 4); and high-level formal education corresponds to tertiary education (ISCED 5, 6, 7 or 8). Computer related activities surveyed and used for skills aggregation were: copying or moving a file or folder; using copy and paste tools to duplicate or move information within a document; using basic arithmetic formulas in a spreadsheet; compressing (or zipping) files; connecting and installing new devices, e.g. a modem; writing a computer programme using a specialised programming language.

Source: Eurostat [isoc_sk_cskl_i]

9.4. Creativity

Young people's creativity and capacity for innovation are important skills for their active participation in society. Engaging in creative experiences also fosters the development of transversal soft-skills such as finding new ways to tackle problems, being able to handle risk and learn from failure, and adapting knowledge to new applications, which in turn help improve employability and entrepreneurial potential ().

When asked about the perceived importance of being creative, a majority of young respondents to a survey conducted in 2012 indicated that they valued the ability to develop innovative ideas and creative thinking (Figure 9-K).

Figure 9-K: Share of young people (aged 15-29) saying that it is important to think new ideas and be creative, EU-27 average, 2012

|

%

%

|

Note: the question asked respondents to what extent the statement 'It is important to think new ideas and being creative' was similar to their own opinion. Base: all respondents.

Source: European Social Survey, 2012

|

|

|

Very much like me

|

Like

me

|

Somewhat like me

|

A little like me

|

Not like

me

|

Not like me

at all

|

|

|

Unfortunately, evidence about the ways in which young people actually participate in creative activities is still limited. A Eurobarometer survey conducted in 2013 sheds some light on young people's use of the internet for creative activities. According to the results, young respondents tend to be engaged in such activities more than older ones (Figure 9-L). In particular, filming, photography, and sharing their own creative content online appear to be the most common activities amongst young people.

Figure 9-L: Share of the population undertaking creative activities during the 12 months preceding the survey, by age group, EU-28 average, 2013

%

%

|

|

Made a film,

done some photography

|

Put own cultural content online, e.g. on an online social network or on a sharing site

|

Done creative computing such designing websites or blogs

|

Written a poem, an essay, a novel, etc.

|

Created own website or blog with cultural content

|

|

Note: questions were: 'What do you use the Internet for, in terms of cultural purposes?' and 'Please tell me if, in the last 12 months, you have either on your own or as part of an organised group or classes…'. Base: all respondents.

Source: Special Eurobarometer 399 'Cultural access and participation', 2013

10. YOUTH AND THE WORLD

|

EU Youth Indicators

|

|

|

Participation of young people in non-governmental organisations

active in the domain of climate change/environmental issues

|

Figures 10-B, 10-D and 10-E

|

|

Participation of young people in non-governmental organisations

promoting human rights or global development

|

Figure 10-C, 10-D and 10-E

|

|

Participation of young people in activities or projects aimed at fostering cooperation with young people from other continents

|

Figures 10-F and 10-G

|

10.1. Introduction

Today, young people are growing up in a world substantially different from the one in which their parents were raised. Globalisation shapes all aspects of their lives: they live in increasingly diverse societies, consume global goods and culture, and have jobs in globally integrated economies. While this presents new opportunities, it also carries high levels of uncertainties and risks (). Globalisation affects not only young people's work prospects, but also their identity, sense of citizenship and patterns of political engagement () (see also Chapter 7). In this respect, their experiences could make them more prone to engage with global issues such as human rights, climate change or environmental protection ().

Based on Eurobarometer surveys, this section therefore looks at the extent to which young Europeans are actually engaged with global issues, as well as at how much they participate in activities designed to foster cooperation between young people from different continents.

10.2. Young people's engagement with global issues

Young people's engagement with global issues can take various forms. Organised action, for example through non-governmental organisations (NGOs), requires the most active commitment. However, young people can also contribute to global issues through small-scale, individual and everyday activities (). As a recent Eurobarometer survey on young people demonstrates, a large proportion of young people are indeed engaged with global issues like sustainable development and climate change at various different levels (Figure 10-A).

Figure 10-A: Proportion of young people (aged 16-30) taking actions in everyday life to protect the environment and combat climate change, EU-28 average, 2014

|

|

|

%

|

|

Systematically sorting waste

|

|

|

|

Reducing water and energy consumption at home

|

|

|

|

Reducing consumption of disposable items

|

|

|

|

Using more environmentally-friendly means of transport

|

|

|

|

Systematically buying local products

|

|

|

|

Using the car less often and more efficiently

|

|

|

|

Better insulating the home/place of living

|

|

|

|

Avoiding going by plane for short-haul flights

|

|

|

|

None

|

|

|

|

|

|

%

|

Notes: Question: 'Which of the following steps to protect the environment and combat climate change have you taken personally?' – 'Systematically sorting your waste'; 'Reducing your water and energy consumption at home (electricity, heating, household appliances)'; 'Reducing your consumption of disposable items (plastic bags, useless packaging)'; 'Changing your mode of transport to use a more environmentally-friendly means of transport'; 'Systematically buying local products'; 'Using your car less often and more efficiently (e.g. car-sharing)'; Carrying out the necessary work to better insulate your home/place where you live'; 'Avoiding going by plane for short-haul flights' (Multiple answers possible). Base: all respondents. Source: Flash Eurobarometer of the European Parliament (EP EB395) on 'European Youth in 2014', 2014

As Figure 10-A shows, a large majority of European youth has adopted certain lifestyle changes in order to protect the environment and combat climate change. The most common actions include sorting waste systematically (74 %), reducing water and energy consumption at home (65 %), and reducing the consumption of disposable items like plastic bags (58 %).

|

While many young Europeans take actions in everyday life to combat global problems, only a small fraction are actively engaged in organisations that pursue globally relevant issues.

|

Nevertheless, when it comes to young Europeans' active engagement with global issues through more organised activities, their commitment is relatively low. Another recent Eurobarometer survey on 'European Youth' finds that only 3.1 % participate in NGOs active in the domain of climate change or other environmental issues, while 4.7 % do so in the areas of promoting human rights or global development (Figures 10-B and 10-C). In contrast, 11 % of young people participate in NGOs aimed at improving their local community (see Figure 7-I).

Figure 10-B: EU youth indicator: Participation of young people (aged 15-30) in non-governmental organisations active in the domain of climate change/environmental issues, self-reported participation in the 12 months preceding the survey, by country, 2011 and 2014

|

EU youth indicator

|

%

%

|

Notes: Question: 'Have you in the past year participated in any activities of the following organisations?' - 'An organisation active in the domains of global climate change/global warming' (2011), 'An organisation active in the domain of climate change/environmental issues' (2014) (Multiple answers possible.)

Base: all respondents, % of 'yes' answers by country, EU-27 (2011) and EU-28 (2014)

Source: Flash Eurobarometer 319a, 'Youth on the Move', 2011 and Flash Eurobarometer 408, 'European Youth', 2015

Figure 10-C: EU youth indicator: Participation of young people (aged 15-30) in non-governmental organisations promoting human rights or global development, self-reported participation in the 12 months preceding the survey, by country, 2011 and 2014

|

EU youth indicator

|

%

%

|

Notes: Question: 'Have you in the past year participated in any activities of the following organisations?' - 'An organisation promoting human rights or global development' (Multiple answers possible.)

Base: all respondents, % of 'yes' answers by country, EU 27 (2011) and EU 28 (2014)

Source: Flash Eurobarometer 319a, 'Youth on the Move', 2011 and Flash Eurobarometer 408, 'European Youth', 2015

In general, across the EU-28, more young people participate in NGOs working in the field of human rights or global development than in climate change or environmental issues. However, there are large differences between countries. Young people's participation in both fields tends to be higher in western (and especially northern) European countries than in eastern Europe, though not without exceptions. Regarding climate change and environmental issues, young people's participation rates range from zero or nearly zero per cent in Croatia and Romania to over 6 % in Luxembourg (6.2 %) and Sweden (7.2 %). With respect to human rights and global development, young people participate the least in NGOs in Bulgaria (0.8 %), Croatia and Romania (both at 1.4 %), while they tend to be the most active in Denmark (10.4 %), Ireland (11.7 %) and Sweden (16.2 %). The active engagement of young people in Sweden is exceptionally high within the EU-28.

As Figures 10-B and 10-C show, young people's participation in NGOs in these globally relevant areas stayed relatively stable across the EU () between 2011 and 2014, with a small decrease in the field of human rights promotion and global development (from 5.2 % to 4.7 %). Due to small sample sizes, comparisons across time by country should be made cautiously. Nevertheless, relatively significant falls in young people's participation in NGOs across both fields occurred in Bulgaria, France and Romania; in Spain, however, there was a substantial increase. In the area of promoting human rights and global development, significant changes took place in Greece and Italy (a decrease) as well as in Ireland and Sweden (an increase).

But who are these young people who are actively engaged with global issues? The Eurobarometer on 'European Youth' indicates that while young women and men are equally active in NGOs dealing with global problems, women tend to be more interested in human rights promotion and global development, while men are relatively more likely to engage with environmental issues (Figure 10-D-b). Furthermore, young people over the age of 25 are more likely to be active in these fields than their younger peers: 43 % of young respondents participating in relevant NGOs were between 25 and 30 years of age (Figure 10-D-a).

Figure 10-D: EU youth indicator: Young people (aged 15-30) participating in non-governmental organisations active in the domains of climate change/environmental issues, human rights or global development in the 12 months preceding the survey, EU-28 average, 2014

|

EU youth indicator

|

|

|

a) by age

|

b) by issue and by sex

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Climate Change

|

|

|

Aged

|

|

|

|

Female

|

|

|

|

15-19

|

|

|

|

Male

|

|

|

|

20-24

|

|

|

Human rights

|

|

|

|

25-30

|

|

|

|

Female

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Male

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Notes: Question: Have you in the past year participated in any activities of the following organisations?' 'An organisation active in the domain of climate change/environmental issues'; 'An organisation promoting human rights or global development' (Multiple answers possible.)

Base: all respondents, % of 'yes' answers, EU-28

Source: Flash Eurobarometer 408, 'European Youth', 2015

In addition, despite young people in their late twenties being more likely to be engaged with global issues, a large proportion of active young people are still in education: one third of those active in the field of climate change or environmental issues; and half of those engaged with human rights promotion or global development (Figure 10-E). Among the young people who have finished their education, the longer they studied, the more likely it is that they actively participate in NGOs dealing with global challenges. This suggests that active engagement with globally relevant topics increases with the level of education.

Figure 10-E: EU youth indicator: Young people (aged 15-30) participating in non-governmental organisations active in the domain of climate change/environmental issues, human rights or global development, in the 12 months preceding the survey by education status (still in education or age of completion), EU-28 average, 2014

|

EU youth indicator

|

Climate change/environmental issues

|

|

|

Human rights or global development

|

|

|

|

Completed education at age :

|

|

|

|

|

|

15-

|

|

|

|

|

|

16-19

|

|

|

|

|

|

20+

|

|

|

|

|

|

Still in education

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Notes: Questions: 'Have you in the past year participated in any activities of the following organisations?' - 'An organisation active in the domain of climate change/environmental issues'; 'An organisation promoting human rights or global development' (Multiple answers possible.); 'How old were you when you stopped full-time education?'

Base: all respondents, % of 'yes' answers, EU-28

Source: Flash Eurobarometer 408, 'European Youth', 2015

10.3. Cooperation among young people from different continents

At 3 %, the participation of European young people in activities or projects fostering cooperation with young people from other continents is also relatively low in the EU-28, and has even fallen from the 4 % reported in 2011 (Figure 10-F). For comparison, in 2014, 5 % (6 % in 2011) of young people reported having participated in activities and projects together with young people from other European countries ().

Nevertheless, differences between countries are again substantial, with young people from eastern and southern European countries participating less in such activities than their peers from western and northern Europe. Participation rates of respondents are the lowest in Greece (0.3 %), Cyprus (1.3 %) and Romania (1.4 %), and the highest in Finland (7 %), Belgium (7.4 %) and Luxembourg (9.2 %). Luxembourg is the only country with a significant increase since 2011 in young people's participation in activities together with young people from other continents. The countries with the largest falls in participation rates are Germany, Greece and Austria (see Figure 10-F).

Figure 10-F: EU Youth Indicator: Participation of young people (aged 15-30) in activities or projects aimed at fostering cooperation with young people from other continents, self-reported participation in the 12 months preceding the survey, by country, 2011 and 2014

|

EU youth indicator

|

%

%

|

Notes: Question: 'Have you participated in any activities or projects during the past year aimed at fostering cooperation with youth from other countries?' – 'Yes, in activities or projects with young people from other continents' (Multiple answers possible.)

Base: all respondents, % of 'yes' answers by country, EU-27 (2011) and EU-28 (2014)

Source: Flash Eurobarometer 319a, 'Youth on the Move', 2011 and Flash Eurobarometer 408, 'European Youth', 2015

Figure 10-G: EU youth indicator: Young people (aged 15-30) participating in activities or projects aimed at fostering cooperation with young people from other continents in the 12 months preceding the survey, EU-28 average, 2014

|

EU youth indicator

|

|

|

a) by age

|

b) by education status

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Completed education at age:

|

|

|

Aged

|

|

|

|

15-

|

|

|

|

15-19

|

|

|

|

16-19

|

|

|

|

20-24

|

|

|

|

20+

|

|

|

|

25-30

|

|

|

|

Still in education

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Notes: Question: 'Have you participated in any activities or projects during the past year aimed at fostering cooperation with youth from other countries?' – 'Yes, in activities or projects with young people from other continents' (Multiple answers possible.); 'How old were you when you stopped full-time education?'

Base: all respondents, % of 'yes' answers, EU-28

Source: Flash Eurobarometer 408, 'European Youth', 2015

The majority of young people participating in projects together with young people from other continents are still in education.

|

In contrast to NGO participation in globally relevant domains, the likelihood of participating in activities or projects together with young people from other continents does not increase with age: the young people most likely to be involved in such activities are in their early twenties (Figure 10-G-a). In addition, a large majority of respondents (58 %) are still studying, and only 16 % of participating young people completed their education before they turned 20 (Figure 10-G-b). This suggests that many of the cooperation activities are linked to higher education studies and exchanges.

REFERENCES

Aassve, A., Davia, M.A., Iacovou, M. and Mazzuco, S., 2007. Does leaving home make you poor? Evidence from 13 European countries. European Journal of Population 23(3), p. 315-338.

Barber, T., 2010. Participation, Citizenship and Well-Being: Engaging with Young People, Making a Difference. In: Young, 17, p. 25-40.

Bellani, L. and Bia, M., 2013. Measuring intergenerational transmission of poverty. Paper presented at the fifth meeting of the Society for the Study of Economic Inequality (ECINEQ), Bari (Italy), July 22-24, 2013. Available at:

www.ecineq.org/ecineq_bari13/FILESxBari13/CR2/p72.pdf

[Accessed 1 April 2015].

Bloom, D.E., Canning, D., Fink, G. and Finlay, J.E., 2008. The high cost of low fertility in Europe. In: Working Paper Series. Harvard University Programme on the Global Demography of Ageing. Working Paper 32.

Bourn, D., 2008. Young people, identity and living in a global society. In: Policy & Practice – A Development Education Review, 7, p. 48-61.

Branas, C.C., Kastanaki, A.E., Michalodimitrakis, M., Tzougas, J., Kranioti, E.F., Theodorakis, P.N., Carr, B.G. and Wiebe, D.J., 2015. The impact of economic austerity and prosperity events on suicide in Greece: a 30-year interrupted time-series analysis. In: BMJ Open, 5(1), e005619.

Broh, B.A., 2002. Linking Extracurricular Programming to Academic Achievement: Who Benefits and Why? In: Sociology of Education, Jan 2002, 75, p.69-95.

Buchmann, M.C. and Kriesi, I., 2011. Transition to Adulthood in Europe. In: Annual Review of Sociology, 37, p. 481-503.

CEDEFOP (European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training), 2010. The skill matching challenge. Analysing skill mismatch and policy implications. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available at

http://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/publications-and-resources/publications/3056

[Accessed 4 June 2015].

Coombs, P.H., Prosser, C. and Ahmed, M., 1973. New Paths to Learning for Rural Children and Youth. New York: International Council for Educational Development.

Council of Europe, 2005. Trading up Potential and performance in non-formal learning. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Council of the European Union, 2011. Council conclusions on a benchmark for learning mobility, 3128th EDUCATION, YOUTH, CULTURE and SPORT Council meeting, Brussels, 28 and 29 November 2011. Available at:

http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/educ/126380.pdf

[Accessed 9 March 2015].

EACEA (Education, Audio-visual and Culture Executive Agency), 2011. Volunteering in the European Union. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available at:

http://ec.europa.eu/citizenship/pdf/doc1018_en.pdf

[Accessed 27 May 2015].

EACEA, 2013. Youth Participation in Democratic Life. [Online]. Available at:

http://eacea.ec.europa.eu/youth/tools/documents/lse_study_on_youth_participation_2013.pdf

[Accessed 4 June 2015].

EENEE (European Expert Network on Economics of Education), 2014. The economic case for education. EENEE Analytical Report No. 20. Prepared for the European Commission.

EMCDDA (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction), 2012. EU Drug Markets Report: A Strategic Analysis. Case study 3: New psychoactive substances: 73 detected in 2012. Available at:

http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/attachements.cfm/att_194349_EN_Case%20study%203_New%20psychoactive%20subst_Final.pdf

[Accessed 26 January 2015].

EMCDDA, 2014. European Drug Report: Trends and Developments. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

EPHA (European Public Health Alliance), 2014. Growing up in the unhappy shadow of the economic crisis: Mental health and well-being of the European child and adolescent population. Brussels: EPHA.

ETUI (European Trade Union Institute) 2015, Benchmarking Working Europe 2014, Brussels: ETUI aisbl.

Eurofound (European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions), 2011a. Foundation findings: Youth and Work. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Eurofound, 2011b. Young people and NEETs in Europe: First Findings. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Eurofound, 2012. NEETs: Young people not in employment, education or training: Characteristics, costs and policy responses in Europe. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Eurofound, 2013a. Working conditions of young entrants to the labour market, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Eurofound, 2013b. Young People and temporary employment in Europe. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Eurofound, 2014a. Mapping youth transitions in Europe. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Eurofound, 2014b. Social situation of young people in Europe. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

European Commission, 2010a. COM(2010) 758 final, Communication From The Commission To The European Parliament, The Council, The European Economic And Social Committee And The Committee Of The Regions - The European Platform against Poverty and Social Exclusion: A European framework for social and territorial cohesion. Brussels.

European Commission, 2010b. Special Eurobarometer 331. EU citizens' attitudes towards alcohol. [pdf] Available at:

http://ec.europa.eu/health/alcohol/docs/ebs_331_en.pdf

[Accessed 4 June 2015].

European Commission, 2010c. Special Eurobarometer 334. Sport and physical activity. [pdf] Available at:

http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_334_en.pdf

[Accessed 4 June 2015].

European Commission, 2012a. EU Youth Report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

European Commission, 2012b. First European Survey on Language Competencies: Final Report. Luxembourg: Publication Office of the European Union. Available at:

http://ec.europa.eu/languages/policy/strategic-framework/documents/language-survey-final-report_en.pdf

[Accessed 25 March 2015].

European Commission, 2012c. Flash Eurobarometer 354. Entrepreneurship in the EU and beyond. [pdf] Available at

http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/flash/fl_354_en.pdf

[Accessed 2 February 2015].

European Commission, 2013a. Commission Staff Working Document. Assessment of the 2013 national reform programme and convergence programme for Latvia, SWD(2013) 364 final Brussels, 29.05.2013.

European Commission, 2013b. Commission Staff Working Document. Assessment of the 2013 national reform programme and convergence programme for Lithuania, SWD(2013) 365 final, Brussels, 29.05.2013.

European Commission, 2013c. Commission Staff Working Document. Confronting Homelessness in the European Union, SWD(2013) 42 final, Brussels, 20.2.2013.

European Commission, 2013d. Developing the creative and innovative potential of young people through non-formal learning in ways that are relevant to employability. Expert Group Report, May 2013.

European Commission 2014a. Education and Training Monitor. Luxembourg: Publication Office of the European Union.

European Commission, 2014b. Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2013. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

European Commission, 2014c. Erasmus Impact Study: Effects of mobility on the skills and employability of students and the internationalisation of higher education institutions. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

European Commission, 2014d. Erasmus: Facts, Figures & Trends. The European Union support for student and staff exchanges and university cooperation in 2012-2013. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

European Commission, 2014e. EU Employment and Social Situation. Quarterly Review. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

European Commission, 2014f. Special Eurobarometer 417. European Area of Skills and Qualifications. [pdf] Available at:

http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_417_en.pdf

[Accessed 5 June 2015].

European Commission, 2014g. Flash Eurobarometer 378. The Experience of Traineeships in the EU. [pdf] Available at

http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/flash/fl_378_en.pdf

[Accessed 2 February 2015].

European Commission, 2014h. Working with young people: The value of youth work in the EU. Luxembourg: Publication Office of the European Union.

European Commission, 2014i. Flash Eurobarometer 401. Young people and drugs. [pdf] Available at:

http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/flash/fl_401_en.pdf

[Accessed 4 June 2015].

European Commission, 2014j. Special Eurobarometer 412. Sport and physical activity. [pdf] Available at:

http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_412_en.pdf

[Accessed 4 June 2015].

European Commission, 2015a. ECHI – European Core Health Indicators. [Online] Available at:

http://ec.europa.eu/health/indicators/echi/list/index_en.htm

[Accessed 1 June 2015].

European Commission, 2015b. Flash Eurobarometer 408. European Youth. [pdf] Available at

http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/flash/fl_408_en.pdf

[Accessed 3 June 2015].

European Commission, 2015c. Special Eurobarometer 429. Attitudes of Europeans towards tobacco and electronic cigarettes. [pdf] Available at:

http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_429_en.pdf

[Accessed 16 June 2015].

European Commission/EACEA, 2013. Youth Social Exclusion and Lessons from Youth Work. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/youth/library/reports/eurydice-study-social-exclusion-2013_en.pdf [Accessed 17 March 2015].

European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2013a. Political Participation and EU Citizenship: Perceptions and Behaviours of Young People. Evidence from Eurobarometer surveys. Available at:

http://eacea.ec.europa.eu/youth/tools/documents/perception-behaviours.pdf

[Accessed 16 January 2015].

European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2013b. Towards a Mobility Scoreboard: Conditions for Learning Abroad in Europe. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice/Cedefop, 2014. Tackling Early Leaving from Education and Training in Europe: Strategies, Policies and Measures. Eurydice and Cedefop Report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice/Eurostat, 2014. Key Data on Early Childhood Education and Care in Europe. 2014 Edition. Eurydice and Eurostat Report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2015. The European Higher Education Area in 2015: Bologna Process Implementation Report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

European Parliament, 2014. European Youth in 2014. Flash Eurobarometer of the European Parliament (EP EB395). [pdf] Available at:

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/pdf/eurobarometre/2014/youth/eb_395_synthesis_youth_en.pdf

[Accessed 5 February 2015].

Eurostat, 2015a. Being young in Europe today. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available at:

http://ec.europa.eu/malta/pdf/being_young_in_europe_today.pdf

[Accessed 27 July 2015].

Eurostat, 2015b. Glossary: At-risk-of-poverty rate. [Online] Available at:

http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Glossary:At-risk-of-poverty_threshold

[Accessed 30 March 2015].

Eurostat, 2015c. Glossary: Equivalised disposable income. [Online] Available at:

http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Glossary:Equivalised_disposable_income

[Accessed 30 March 2015].

Eurostat, 2015d. Glossary: Housing cost overburden rate. [Online] Available at:

http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Glossary:Housing_cost_overburden_rate

[Accessed 23 March 2015].

Eurostat, 2015e. Glossary: Material deprivation. [Online] Available at:

http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Glossary:Material_deprivation

[Accessed 30 March 2015].

Eurostat, 2015f. Glossary: Overcrowding rate. [Online] Available at:

http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Glossary:Overcrowding_rate

[Accessed 23 March 2015].

Eurostat, 2015g. Glossary: Persons living in households with low work intensity. [Online] Available at:

http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Glossary:Work_intensity

[Accessed 30 March 2015].

Eurostat, 2015h. Glossary: Severe Housing deprivation rate. [Online] Available at:

http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Glossary:Severe_housing_deprivation_rate

[Accessed 23 March 2015].

Eurostat, 2015i. Housing conditions. [Online] Available at:

http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Housing_conditions

[Accessed 27 March 2015].

Eurostat, 2015j. Europe 2020 indicators - poverty and social exclusion. [Online] Available at:

http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Europe_2020_indicators_-_poverty_and_social_exclusion

[Accessed 4 June 2015].

Feixa, C, Pereira, I. and Juris, J.S., 2009. Global citizenship and the 'New, New' social movements: Iberian connections. In: Young, 17, p. 421-442.

Flisi, S., Goglio, V., Meroni, E.C., Rodrigues, M. and Vera-Toscano, E., 2014. Occupational mismatch in Europe: Understanding overeducation and overskilling for policy making. JRC Science and Policy Reports. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Flisi, S., Goglio, V., Meroni, E.C., Vera-Toscano, E. and Dragomirescu-Gaina, C., 2015. Skills beyond education: An analysis of cognitive skill evolution and its implications for employment chances. JRC Science and Policy Reports. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Furlong, A., 2002. Youth transitions and health: a literature review. Edinburgh: NHS Health Scotland.

Furlong, A., Cartmel, F., Biggart, A., Sweeting, H. and West, P., 2003. Youth Transitions: Patterns of Vulnerability and Processes of Social Inclusion. Edinburgh: NHS Health Scotland.

Gaiser, W., De Rijke, J., and Spannring, N., 2010. Youth and Political Participation. Empirical Results from Germany in an European Context. In: Young, 18, p. 9-32.

Hall, G., 2008. Civic connections: practicing democracy through debate clubs in the out-of-school time hours. In: S.L. Hill, ed., After School Matters: Creative Programs that Connect Youth Development and Student Achievement. Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press.

Harris, A., Wyn, J. and Younes, S., 2010. Beyond apathetic or activist youth. In: Young, 18(1), p. 9-32.

Haski-Leventhal, D., 2008. Youth volunteering for youth: Who are they serving? How are they being served? In: Children and Youth Services Review 30, p. 834-846.

Hauschildt, K., Gwosć, C., Netz, N. and Mishra, S., 2015. Social and Economic Conditions of Student Life in Europe. Synopsis of Indicators, EUROSTUDENT V 2012-2015. Bielefeld: W. Bertelsmann Verlag.

Hoikkala, T., 2009. The diversity of youth citizenships in the European Union. In: Young, 17(1), p. 5-24.

Iacovou, M., 2011. Leaving home: independence, togetherness and income in Europe. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, Expert Paper no. 2011/10. [pdf] Available at:

http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/expert/2011-10_Iacovou_Expert-paper.pdf

[Accessed 26 March 2015].

Inkei, P., 2010. The Effects of the Economic Crisis on Culture. Culture Watch Europe Conference, Brussels, 6-7 September 2010.

Jackson, C.A., Henderson, M., Frank, J.W. and Haw, S.J., 2012. An overview of prevention of multiple risk behaviour in adolescence and young adulthood. In: Journal of Public Health, 34(s1), p. i31-i40.

Jaime-Castillo, A. M., 2008. Young People's Trajectories of Political Participation in Europe: Cohort Effects or Life-Cycle Effects? In: Young People's Studies Magazine, 81. Available at:

http://www.academia.edu/152115/Young_Peoples_Trajectories_of_Political_Participation_in_Europe_Cohort_Effects_or_Life-Cycle_Effects

[Accessed 27 May 2015].

Lanzieri, G., 2013. Long-term contribution of migration in ageing populations: Japan compared with Europe. Eurostat Statistical working papers. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available at:

http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3217494/5784765/KS-TC-13-001-EN.PDF/0b6d2393-11b1-4fb8-9d6a-b186636b7e8c?version=1.0

[Accessed 27 July 2015].

Madden, C., 2009. Global financial crisis and recession: Impact on the arts. In: D'Art Topics in Arts Policy, 37.

Moldoveanu, M. and Ioan-Franc, V., 2011. The impact of the economic crisis on culture. In: Review of General Management, Volume 14 (2).

OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development), 2014a. International Migration Outlook 2014. Paris: OECD Publishing. Available at:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/migr_outlook-2014-en

[Accessed 4 June 2015].

OECD, 2014b. Health at a Glance: Europe 2014. Paris: OECD Publishing. Available at:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/health_glance_eur-2014-en

[Accessed 16 June 2015].

Partnership between the European Commission and the Council of Europe in the field of Youth, 2011. Final Report of the Research Seminar “Mobility of young people – Opportunities and obstacles for cross-border volunteering for young people, particularly with fewer opportunities”. Strasbourg, 11-13 December 2011.

Piliavin, J.A., 2003. Doing well by doing good: Benefits for the benefactor. In: C. Keyes and J. Haidt, eds., Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, p. 227-247.

Sacco, P.L., 2011. Culture 3.0: A new perspective for the EU 2014-2020 structural funds programming on behalf of the European Expert Network on Culture (EENC), Produced for the OMC Working Group on Cultural and Creative Industries, April 2011.

Salto, 2005. Bridges for Recognition: Promoting Recognition of Youth Work across Europe. Brussels: SALTO-YOUTH Inclusion Resource Centre. Available at: http://pjp-eu.coe.int/documents/1017981/3084932/Bridges_for_recognition_n.pdf/1e7ebb5c-4edb-4bce-8fe0-db42605938c2 [Accessed 10 March 2015].

Santo, C.A., Ferguson, N. and Trippel, A., 2010. Engaging Urban Youth through Technology: the Youth Neighbourhood Mapping Initiative. In: Journal of Planning Education and Research, 30, p. 52-65.

Sawyer, S.M., Afifi, R.A., Bearinger, L.H., Blakemore, S-J., Dick, B., Ezeh, A.C. and Patton, G.C., 2012. Adolescence: a foundation for future health. In: Lancet, 379(9826), p. 1630-1640.

Shernoff, D.J. and Lowe Vandell, D., 2007. Engagement in after-school program activities: quality of experience from the perspective of participants. In: Journal of Youth Adolescence, 36, p. 891-903.

Smith, M. K., 2002. Informal, non-formal and formal education: a brief overview of different approaches. In: The encyclopedia of informal education. [Online] Available at

http://www.infed.org/foundations/informal_nonformal.htm

[Accessed 11 March 2015].

Thomson, S., Figueras, J., Evetovits, T., Jowett, M., Mladovsky, Ph., Maresso, A., Cylus, J., Karanikolos, M. and Kluge, H., 2014. Policy Summary 12: Economic crisis, health systems and health in Europe: impact and implications for policy. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe and European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies.

UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization), 2009. Measuring cultural participation

Vanhuysse, P., 2014. Intergenerational Justice and Public Policy in Europe. In: European Social Observatory, OSE Opinion Paper No.16.

Viner, R.M., Ozer, E.M., Denny, S., Marmot, M., Resnick, M., Fatusi, A. and Currie, C., 2012. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. In: Lancet, 379(9826), p. 1641-1652.

WHO (World Health Organization), 2010. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. Switzerland: WHO.

WHO, 2014. Literature Review on the Health Effects of Smoke-free Policies in Light of the WHO FCTC. [pdf] Available at:

http://ec.europa.eu/health/archive/ph_information/documents/tobacco_control_en.pdf

[Accessed 17 February 2015].

WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2009. A Snapshot of the Health of Young People in Europe. A report prepared for the European Commission Conference on Youth Health, Brussels, Belgium, 9-10 July 2009. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2011. Impact of Economic Crises on Mental Health. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2012. Social Determinants of Health and Well-being among Young People. Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) Study: International Report from the 2009/2010 Survey. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

Williamson, H., Hoskins, B., and Boetzelen, P., eds., 2005. Charting the landscape of European youth voluntary activities. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

ABBREVIATIONS

Statistical codes

:

Data not available

Country not participating in data collection

Country codes

|

EU Member States ()

|

|

BE

|

Belgium

|

|

BG

|

Bulgaria

|

|

CZ

|

Czech Republic

|

|

DK

|

Denmark

|

|

DE

|

Germany

|

|

EE

|

Estonia

|

|

IE

|

Ireland

|

|

EL

|

Greece

|

|

ES

|

Spain

|

|

FR

|

France

|

|

HR

|

Croatia

|

|

IT

|

Italy

|

|

CY

|

Cyprus

|

|

LV

|

Latvia

|

|

LT

|

Lithuania

|

|

LU

|

Luxembourg

|

|

HU

|

Hungary

|

|

MT

|

Malta

|

|

NL

|

Netherlands

|

|

AT

|

Austria

|

|

PL

|

Poland

|

|

PT

|

Portugal

|

|

RO

|

Romania

|

|

SI

|

Slovenia

|

|

SK

|

Slovakia

|

|

FI

|

Finland

|

|

SE

|

Sweden

|

|

UK

|

United Kingdom

|

|

Non-EU Member States

|

|

IS

|

Iceland

|

|

LI

|

Liechtenstein

|

|

NO

|

Norway

|

|

ME

|

Montenegro

|

|

MK

|

The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia

|

|

RS

|

Serbia

|

|

TR

|

Turkey

|

|

|

|

Other Abbreviations

|

|

EACEA

|

Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency

|

|

EEA

|

European Economic Area

|

|

EFTA

|

European Free Trade Association

|

|

EHEA

|

European Higher Education Area

|

|

EMCDDA

|

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction

|

|

EQLS

|

European Quality of Life Survey

|

|

ESPAD

|

European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs

|

|

ESS

|

European Social Survey

|

|

EU

|

European Union

|

|

EU-15

|

15 Member States of the EU before 1 May 2004

|

|

EU-27

|

27 Member States of the EU before 1 July 2013

|

|

EU-28

|

28 Member States of the EU

|

|

HBSC

|

Health Behaviour In School-aged Children, WHO Collaborative Cross-National Survey

|

|

ICT

|

Information and communication technology

|

|

ILO

|

International Labour Organisation

|

|

ISCED

|

International Standard Classification of Education

|

|

ISCO

|

International Classifications of Occupations

|

|

LFS

|

Labour Force Survey

|

|

NEET

|

Not in Employment, Education or Training

|

|

OECD

|

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

|

|

SALTO

|

Support, Advanced Learning and Training Opportunities within the European YOUTH programme – a network of eight resource centres

|

|

SILC

|

Statistics on Income and Living Conditions

|

|

TFEU

|

Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

|

|

UN

|

United Nations

|

|

UNICEF

|

United Nations Children's Fund

|

|

UOE

|

United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation Institute for Statistics (UNESCO-UIS), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and the Statistical Office of the European Union (Eurostat)