ISSN 1977-0677

Official Journal

of the European Union

L 155

English edition

Legislation

Volume 60

17 June 2017

|

ISSN 1977-0677 |

||

|

Official Journal of the European Union |

L 155 |

|

|

||

|

English edition |

Legislation |

Volume 60 |

|

|

|

|

|

(1) Text with EEA relevance. |

|

EN |

Acts whose titles are printed in light type are those relating to day-to-day management of agricultural matters, and are generally valid for a limited period. The titles of all other Acts are printed in bold type and preceded by an asterisk. |

II Non-legislative acts

REGULATIONS

|

17.6.2017 |

EN |

Official Journal of the European Union |

L 155/1 |

COMMISSION DELEGATED REGULATION (EU) 2017/1018

of 29 June 2016

supplementing Directive 2014/65/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council on markets in financial instruments with regard to regulatory technical standards specifying information to be notified by investment firms, market operators and credit institutions

(Text with EEA relevance)

THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION,

Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union,

Having regard to Directive 2014/65/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 May 2014 on markets in financial instruments and amending Directive 2002/92/EC and Directive 2011/61/EU (1), and in particular the third subparagraph of Articles 34(8) and the third subparagraph of Article 35(11) thereof,

Whereas:

|

(1) |

It is important to specify the information that investment firms, market operators and, where required by Directive 2014/65/EU, credit institutions should notify to the competent authorities of their home Member State when they wish to provide investment services or perform investment activities as well as ancillary services in another Member State, in order to establish uniform information requirements and to benefit from the possibility to provide services throughout the Union. |

|

(2) |

The scope and the content of information to be communicated to the home competent authority by investment firms, credit institutions or market operators wishing to provide investment services or activates as well as ancillary activities or arrangements to facilitate access and trading vary according to the purpose and the form of the passport rights. For reasons of clarity it is therefore appropriate to define different types of passport notification for the purposes of this Regulation. |

|

(3) |

For the same reasons, it is also important to clarify the information that investment firms or market operators, operating a multilateral trading facility (‘MTF’), or organised trading facility (‘OTF’), should submit when they wish to facilitate, within the territory of another Member State, access to and trading on those systems by remote users, members or participants established in that other Member State. |

|

(4) |

Competent authorities of home and host Member States should receive updated information in case of any change in the particulars of a passport notification, including any withdrawal or cancellation of the authorisation to provide investment services and activities. That information should ensure those competent authorities are able to make an informed decision that is consistent with their powers and responsibilities. |

|

(5) |

Changes to the name, address and contact details of investment firms in the home Member State are to be considered relevant and should therefore be notified as a change of branch particulars notification or as a change of tied agent particulars notification. |

|

(6) |

It is important for competent authorities of the home and host Member State to cooperate in addressing the threat of money laundering. This Regulation, and in particular the communication of the investment firm's programme of operations, should facilitate the assessment and supervision by the competent authority of the host Member State of the adequacy of the systems and controls to prevent money laundering and terrorist financing of a branch established in its territory, including the skill, knowledge and good character of its money laundering reporting officer. |

|

(7) |

The provisions in this Regulation are closely linked, since they deal with notifications related to the exercise of the freedom to provide investment services and activities and the exercise of the right of establishment that apply to investment firms, market operators and, where foreseen, credit institutions. To ensure coherence between those provisions, which should enter into force at the same time, and to facilitate a comprehensive view and compact access to them by persons subject to those obligations, it is desirable to include all regulatory technical standards for notification of information required by Title II, Chapter III of Directive 2014/65/EU in a single Regulation. |

|

(8) |

For reasons of consistency and in order to ensure the smooth functioning of the financial markets, it is necessary that the provisions laid down in this Regulation and the related national provisions transposing Directive 2014/65/EU apply from the same date. |

|

(9) |

This Regulation is based on the draft regulatory technical standards submitted by ESMA to the Commission. |

|

(10) |

In accordance with Article 10 of Regulation (EU) No 1095/2010 of the European Parliament and of the Council (2), the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) has conducted open public consultations on such draft regulatory technical standards, analysed the potential related costs and benefits and requested the opinion of the Securities and Markets Stakeholder Group established in accordance with Article 37 of that Regulation, |

HAS ADOPTED THIS REGULATION:

Article 1

Scope

1. This Regulation shall apply to investment firms and market operators operating a multilateral trading facility (‘MTF’) or an organised trading facility (‘OTF’).

2. This Regulation shall also apply to credit institutions, authorised under Directive 2013/36/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council (3), which provide one or more investment services or perform investment activities, and wish to use tied agents under the following rights:

|

(a) |

the right of freedom to provide investment services and activities in accordance with Article 34(5) of Directive 2014/65/EU; |

|

(b) |

the right of establishment in accordance with Article 35(7) of Directive 2014/65/EU. |

Article 2

Definitions

For the purposes of this Regulation, the following definitions shall apply:

|

(a) |

‘investment services and activities passport notification’ means a notification made in accordance with Article 34(2) of Directive 2014/65/EU, or in accordance with Article 34(5) of Directive 2014/65/EU; |

|

(b) |

‘branch passport notification’ or ‘tied agent passport notification’ means a notification made in accordance with Article 35(2) of Directive 2014/65/EU, or in accordance with Article 35(7) of Directive 2014/65/EU; |

|

(c) |

‘notification for the provision of arrangements to facilitate access to an MTF or an OTF’ means a notification made in accordance with Article 34(7) of Directive 2014/65/EU. |

|

(d) |

‘passport notification’ means an investment services and activities passport notification, a branch passport notification, tied agent passport notification, or a notification for the provision of arrangements to facilitate access to an MTF or an OTF. |

Article 3

Information to be notified for the purposes of the investment services and activities passport notification

1. Investment firms shall ensure that the investment services and activities passport notification submitted pursuant to Article 34(2) of Directive 2014/65/EU includes the following information:

|

(a) |

the name, address and contact details of the investment firm along with the name of a specified contact person at the investment firm; |

|

(b) |

a programme of operations which includes the following items:

|

2. Credit institutions referred to in Article 1(2)(a) submitting an investment services and activities passport notification in accordance with Article 34(5) of Directive 2014/65/EU shall ensure that such notification contains the information set out in points (a) and (b)(ii) of paragraph 1.

Article 4

Information to be notified concerning the change of investment services and activities particulars

Investment firms and such credit institutions as are referred to in Article 1(2)(a) shall ensure that a notification to communicate a change in particulars, pursuant to Article 34(4) of Directive 2014/65/EU, includes details of any change to any of the information contained in the initial investment services and activities passport notification.

Article 5

Information to be notified concerning arrangements to facilitate access to an MTF or OTF

Investment firms and market operators submitting notifications regarding arrangements to facilitate access to an MTF or OTF pursuant to Article 34(7) of Directive 2014/65/EU shall ensure such notification includes the following information:

|

(a) |

the name, address and contact details of the investment firm or the market operator, along with the name of a specified contact person at the investment firm or the market operator; |

|

(b) |

a short description of the appropriate arrangements to be in place and the date from which these arrangements will be provided in the host Member State; |

|

(c) |

a short description of the business model of the MTF or the OTF, including the type of the financial instruments traded, the type of participants, and the marketing approach of the MTF or OTF to target remote users, members or participants. |

Article 6

Information to be notified in a branch passport notification or a tied agent passport notification

1. Investment firms and such credit institutions as are referred to in Article 1(2)(b) shall ensure that a branch passport notification or a tied agent passport notification submitted pursuant to Article 35(2) or Article 35(7) of Directive 2014/65/EU as applicable, includes the following information:

|

(a) |

the name, address and contact details of the investment firm or credit institution in the home Member State, and the name of a specified contact person at the investment firm or credit institution; |

|

(b) |

the name, address and contact details in the host Member State of the branch or of the tied agent from which documents may be obtained; |

|

(c) |

the name of those persons responsible for the management of the branch or of the tied agent; |

|

(d) |

reference to the location, electronic or otherwise, of the public register where the tied agent is registered; and |

|

(e) |

a programme of operations. |

2. The programme of operations referred to in point (e) of paragraph 1 shall comprise the following items:

|

(a) |

a list of investment services, activities, ancillary services and financial instruments to be provided; |

|

(b) |

an overview explaining how the branch or the tied agent will contribute to the investment firm's, credit institution's or group's strategy, and setting out whether the investment firm is a member of a group, and what the main functions of the branch or tied agent will be; |

|

(c) |

a description of the type of client or counterparty with which the branch or tied agent will be dealing and of how the investment firm or credit institution will obtain and deal with those clients and counterparties; |

|

(d) |

the following information on the organisational structure of the branch or tied agent:

|

|

(e) |

details of individuals performing key functions with the branch or the tied agent, including the individuals responsible for day-to-day branch or tied agent operations, compliance and dealing with complaints; |

|

(f) |

details of any outsourcing arrangements critical to the operations of the branch or the tied agent; |

|

(g) |

summary details of the systems and controls that will be put in place, including:

|

|

(h) |

forecast statements for both profit and loss and cash flow, over an initial 36-month period. |

3. When a branch is to be established in a host Member State and intends to use tied agents in that Member State, in accordance with Article 35(2)(c) of Directive 2014/65/EU, the programme of operations referred to in point (e) of paragraph 1 shall also comprise information regarding the identity, address and contact details of each such tied agent.

Article 7

Information to be notified concerning the change of branch or tied agent particulars

1. Investment firms and such credit institutions as are referred to in Article 1(2)(b) shall ensure that a notification to communicate a change in particulars, pursuant to Article 35(10) of Directive 2014/65/EU, includes details of any change to any of the information contained in the initial branch passport notification or tied agent passport notification.

2. Investment firms and such credit institutions as are referred to in Article 1(2)(b) shall ensure that any changes to the branch passport notification or tied agent passport notification that relate to the termination of the operation of the branch, or the cessation of the use of a tied agent, shall include the following information:

|

(a) |

the name of the person or persons who will be responsible for the process of terminating the operation of the branch or the tied agent; |

|

(b) |

the schedule of the planned termination; |

|

(c) |

the details and processes proposed to wind down the business operations, including details of how client interests are to be protected, complaints resolved and any outstanding liabilities discharged. |

Article 8

Entry into force and application

This Regulation shall enter into force on the twentieth day following that of its publication in the Official Journal of the European Union.

It shall apply from the date that appears first in the second subparagraph of Article 93(1) of Directive 2014/65/EU.

This Regulation shall be binding in its entirety and directly applicable in all Member States

Done at Brussels, 29 June 2016.

For the Commission

The President

Jean-Claude JUNCKER

(1) OJ L 173, 12.6.2014, p. 349.

(2) Regulation (EU) No 1095/2010 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 November 2010 establishing a European Supervisory Authority (European Securities and Markets Authority), amending Decision No 716/2009/EC and repealing Commission Decision 2009/77/EC (OJ L 331, 15.12.2010, p. 84).

(3) Directive 2013/36/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2013 on access to the activity of credit institutions and the prudential supervision of credit institutions and investment firms, amending Directive 2002/87/EC and repealing Directives 2006/48/EC and 2006/49/EC (OJ L 176, 27.6.2013, p. 338).

|

17.6.2017 |

EN |

Official Journal of the European Union |

L 155/6 |

COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2017/1019

of 16 June 2017

imposing a definitive anti-dumping duty and collecting definitively the provisional duty imposed on imports of certain concrete reinforcement bars and rods originating in the Republic of Belarus

THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION,

Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union,

Having regard to Regulation (EU) 2016/1036 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2016 on protection against dumped imports from countries not members of the European Union (1) (‘the basic Regulation’), and in particular Article 9(4) thereof,

Whereas:

A. PROCEDURE

1. Provisional Measures

|

(1) |

The European Commission (‘the Commission’) initiated on 31 March 2016 (2) an investigation following a complaint lodged on 15 February 2016 by the European Steel Association (‘EUROFER’ or ‘the complainant’) on behalf of producers representing more than 25 % of the total Union production of rebars. |

|

(2) |

The Commission imposed on 20 December 2016 a provisional anti-dumping duty on imports of certain concrete reinforcement bars and rods originating in the Republic of Belarus (‘Belarus’ or ‘the country concerned’) by Implementing Regulation (EU) 2016/2303 (3) (‘the provisional Regulation’). |

2. Subsequent procedure

|

(3) |

Subsequent to the disclosure of the essential facts and considerations on the basis of which a provisional anti-dumping duty was imposed (‘the provisional disclosure’), the complainant and the sole Belarusian exporting producer made written submissions making known their views on the provisional findings. The parties who so requested were granted an opportunity to be heard. |

|

(4) |

Hearings took place with the Belarusian exporting producer and with Union producers. |

|

(5) |

The Commission considered the oral and written comments submitted by the interested parties and, where appropriate, modified the provisional findings. |

|

(6) |

In order to verify the questionnaires replies mentioned in recitals (124) and (133) of the provisional Regulation, which were not verified at the provisional stage of the procedure, verification visits were carried out at the premises of the following parties:

|

|

(7) |

The Commission informed all parties of the essential facts and considerations on the basis of which it intends to impose a definitive anti-dumping duty on imports of rebars (‘the definitive disclosure’). All parties were granted a period within which they could make comments on the definitive disclosure. After definitive disclosure, in the light of the findings as established in recitals (18) to (24) of the General Disclosure Document the Commission analysed injury indicators excluding data pertaining to the Italian market for which all parties were informed (the additional final disclosure). Subsequently, all parties were granted a period within which they could make comments on the additional disclosure. The comments submitted by the interested parties were considered and taken into account where appropriate. |

3. Sampling

|

(8) |

In the absence of comments concerning the method of sampling, the provisional findings set out in recitals (7) to (10) of the provisional Regulation are confirmed. |

4. Investigation period and period considered

|

(9) |

In the absence of comments concerning the investigation period (‘IP’) and the period considered, the periods established in recital (14) of the provisional Regulation are confirmed. |

B. PRODUCT CONCERNED AND LIKE PRODUCT

|

(10) |

As set out in recitals (15) to (16) of the provisional Regulation, the product subject to investigation was defined as ‘certain concrete reinforcement bars and rods, made of iron or non-alloy steel, not further worked than forged, hot-rolled, hot-drawn or hot-extruded, but including those twisted after rolling and also those containing indentations, ribs, grooves or other deformations produced during the rolling process, originating in Belarus and currently falling within CN codes ex 7214 10 00, ex 7214 20 00, ex 7214 30 00, ex 7214 91 10, ex 7214 91 90, ex 7214 99 10, ex 7214 99 71, ex 7214 99 79 and ex 7214 99 95 (‘rebars’ or ‘the product concerned’). High fatigue performance iron or steel concrete reinforcing bars and rods are excluded’. |

|

(11) |

Already at provisional stage of the investigation, the exporting producer from Belarus pointed to an alleged inconsistency between the complaint (referring to two CN codes) and the notice of initiation (NoI) (referring to nine CN codes). After explanations given in this regard in the provisional regulation, the Belarussian exporter changed the nature of its claim and requested the inclusion of an additional sentence in the descriptive part of the product concerned in order to make it clear that round bars and other types of bars without indents, ribs or other deformations, which are also covered by the additional seven CN codes, are not included in the product concerned. |

|

(12) |

On the other hand, contrary to the claim of the Belarusian company, the complainant claimed that round bars and other bars without deformation should be included in the product scope. |

|

(13) |

After careful examination, the Commission concludes that the descriptive part of definition of the product concerned in the complaint and in the NoI clearly does not encompass round bars and bars without deformation and, therefore, these bars fall outside the product scope. Furthermore, all the data concerning product concerned collected for the dumping calculations and injury analysis did not include data referring to the round bars or bars without deformation. Therefore, the definition of the product scope should make it clear that round bars and bars without deformation are not part of the product concerned. Hence, the Commission accepts the changes in the description of the product concerned suggested by the Belarusian exporting producer. During this assessment, the Commission verified that the CN codes ex 7214 99 71 and ex 7214 99 79 referred exclusively to round bars and bars without deformation and, therefore, excluded the reference made to them in the definition of the product scope. The Commission also noticed that these bars had been incorrectly included in the information set out in recitals (62), (63), (65) and (103) of the provisional Regulation (Union consumption, volume and market share of the imports concerned, prices of imports, and imports from third countries) and therefore this data was revised accordingly. |

|

(14) |

Taking into account the above, the Commission clarifies the definition of the product concerned as followed: ‘The product concerned is certain concrete reinforcement bars and rods, made of iron or non-alloy steel, not further worked than forged, hot-rolled, hot-drawn or hot-extruded, whether or not twisted after rolling, containing indentations, ribs, grooves or other deformations produced during the rolling process, originating in Belarus and currently falling within CN codes ex 7214 10 00, ex 7214 20 00, ex 7214 30 00, ex 7214 91 10, ex 7214 91 90, ex 7214 99 10 and ex 7214 99 95 (‘the product concerned’). High fatigue performance iron or steel concrete reinforcing bars and rods and other long products, such as round bars are excluded’. |

C. DUMPING

|

(15) |

In the absence of comments concerning details of dumping calculation, the provisional findings and conclusions set out in recitals (19) to (55) of the provisional Regulation are confirmed. |

D. UNION INDUSTRY

|

(16) |

In the absence of any comments concerning the Union industry, the provisional findings and conclusions set out in recitals (56) to (59) of the provisional Regulation are confirmed. |

E. INJURY

|

(17) |

As mentioned in the recitals (13) and (14), the round bars and bars without deformation are not part of the product concerned. These products are currently falling within CN codes ex 7214 99 71 and 7214 99 79. The revised information presented in the tables, as set out in recitals (62), (63) and (65) of the provisional Regulation, is as follows: |

1. Union consumption

|

|

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

IP |

|

Consumption (in tonnes) |

9 308 774 |

8 628 127 |

9 239 505 |

9 544 273 |

|

Index (2012 = 100) |

100 |

93 |

99 |

103 |

2. Volume and market share of the imports concerned

|

|

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

IP |

|

Volume (tonnes) |

159 395 |

140 970 |

236 109 |

457 755 |

|

Index (2012 = 100) |

100 |

88 |

148 |

287 |

|

Market share on EU consumption (%) |

1,8 |

1,6 |

2,6 |

4,8 |

|

Index (2012 = 100) |

100 |

95 |

149 |

280 |

|

Prices of imports |

||||

|

Average price (in EUR/tonne) |

495 |

463 |

436 |

372 |

|

Index (2013 = 100) |

100 |

93 |

88 |

75 |

|

(18) |

The correction of the figures above did not have any impact on the injury assessment. Indeed, the trends observed were the same and therefore the Commission's findings in recitals (62) to (66) of the provisional Regulation are confirmed. |

3. Unreliability of certain injury data of the Union industry as a result of price-fixing

|

(19) |

As described in recital (132) of the provisional Regulation, the Belarusian exporting producer and one of the non-sampled Union importers raised the issue of alleged price-fixing among the Union producers, which would have rendered the injury data unreliable. This claim was further developed by the Belarusian company in its submission after provisional disclosure. The Belarusian exporting producer indicated that a cartel investigation was currently being conducted by Italian Competition Authority (Autorità Garante della Concorrenza e del Mercato (‘AGCM’)) with regard to certain companies located in Northern Italy. One of the companies concerned is part of the sample of the Union producers in the current antidumping investigation. |

|

(20) |

Following this claim, the Commission requested relevant information from AGCM to evaluate whether and to what extent those facts influence the reliability of the injury data of the Union industry in the present anti-dumping proceedings. |

|

(21) |

According to the case-law, in a situation where an investigation into anti-competitive behaviour is pending at a national competition authority, the Commission has to consider whether the Union industry, through this behaviour, has contributed to the injury suffered and establish that the injury on which it bases its conclusions did not derive from the anticompetitive behaviour. The Commission may in such a situation not wait until the competent national authority concludes its investigation, but has to request the relevant information from the parties and the national authorities, as appropriate, under the procedural rules for anti-dumping investigations and carry out an assessment of that information (4). |

|

(22) |

Following a request based on Article 6(3) of the basic Regulation, AGCM has informed the Commission that on 21 October 2015 it opened a formal investigation with respect to six Italian producers of concrete reinforcement bars and welded wire for an alleged infringement of Article 101 TFEU (5). One of these companies is the Italian sampled producer in the current anti-dumping investigation. AGCM extended the proceedings in September 2016 to also cover under the investigation two additional Italian producers. Following the in-depth assessment of all available information, AGCM issued a Statement of Objections that was communicated to the relevant companies on 18 January 2017. The anti-competitive conduct being investigated concerns an alleged exchange of information and price collusion between the eight Italian companies that would cover several phases of the value added chain of their activities from the purchase of inputs, through the levels of production capacity and effective production, up to the sale of the output, which would have taken place over the period 2010 to 2016. On account of its supply and demand side characteristics, the relevant geographic market was defined as national in the formal decision to launch the investigation. |

|

(23) |

The information submitted by AGCM shows that the product concerned in this investigation, rebars, overlaps with the products subject to the antitrust investigation, and also that the alleged cartel was in force during the whole investigation period. In these circumstances, the Commission considers that the data of the sampled Italian producer is not reliable for the purpose of the injury analysis. |

|

(24) |

As a result, the Commission has analysed Union consumption, volume and market share of the imports concerned and also the macroeconomic and microeconomic injury indicators excluding data pertaining to the Italian market. For the sake of transparency, the relevant figures excluding the Italian companies are presented below.

|

|

(25) |

Macroeconomic indicators (tables):

|

|

(26) |

Microeconomic indicators (tables — indexed for confidentiality reasons):

|

|

(27) |

On that basis, the Commission notes that the development of the injury indicators without the data pertaining to Italy is practically the same to the one reflecting the whole Union market including Italy. It can therefore be concluded that following the exclusion of data relating to the Italian market from the injury analysis, the situation of the Union industry is still one of material injury within the meaning of Article 3(5) of the basic Regulation |

|

(28) |

As far as undercutting is concerned, the Commission first notes that the undercutting margin found at provisional stage was 4,5 %. The Commission has re-examined the existence of undercutting in the light of the findings above in recitals (19) to (23). Undercutting is established by using data from the sampled companies. Hence, the Commission has excluded from the undercutting calculations the data relating to the Italian producer that is part of the sample. The undercutting margin based on all sampled companies minus the Italian one remains significant at a level of 4,4 %. |

|

(29) |

The Belarussian exporting producer also claimed that the undercutting (and underselling) calculations should not be done by comparison to the prices of all transactions of the sampled Union producers but only in comparison to those happening where the competition with Belarusian import takes place. Undercutting calculations are normally performed on the basis of dumped imports of the product concerned into the Union with all comparable sales of the Union industry. However, given the specific circumstances of this case and the particular characteristics of the product concerned, the Commission has also calculated an undercutting margin by limiting the analysis to those Member States where the Belarusian products were first sold, mainly in the Netherlands, Germany, Poland, and Lithuania. This approach is based on the conservative assumption that the immediate and direct pressure exercised by the dumped imports on Union sales prices first took place in those Member States. Any subsequent trickling through of the effect to other Member States has thus deliberately been ignored. Under this scenario, the duly adjusted weighted average sales prices of the Belarusian dumped imports were compared to the corresponding sales prices of the sampled Union producers, excluding the one located in Italy, charged to unrelated customers in those regions where direct competition with Belarusian products occurred. This resulted in an undercutting margin of 2,8 %, instead of the 4,5 % margin as established in recital (68) of the provisional Regulation. |

|

(30) |

The product concerned by this investigation can be considered a commodity product, which is very price sensitive. It is therefore concluded that even an undercutting margin of 2,8 % is significant and sufficient to cause price depression as explained in recitals (83), (84) and (98) of the provisional Regulation. |

|

(31) |

Following final disclosure, the Belarussian exporting producer also claimed that the findings above in recitals (19) to (23) would most likely have spill-over effects on other Member States, especially in France, where the parent company of one of the Italian producers has a subsidiary holding a strong market position. However, with respect to the alleged anti-competitive conduct in Italy, AGCM has defined the relevant geographic market as national. Moreover, the evidence of the file summarized in recitals (19) to (23) on its own does not support such a claim. This claim is therefore rejected. |

4. Conclusion on injury

|

(32) |

In the absence of any additional comments with regard to injury to the Union industry, the provisional findings and conclusions set out in recitals (70) to (95) of the provisional Regulation are confirmed. |

F. CAUSATION

1. Effect of dumped imports

|

(33) |

In the absence of any comments with regard to the effect of dumped imports on the economic situation of the Union industry, the findings and conclusions set out in recitals (97) to (100) of the provisional Regulation are confirmed. |

2. Effect of other factors

2.1. Export performance of the Union industry

|

(34) |

In the absence of any comments with regard to export performance of the Union industry, the conclusion set out in recital (101) of the provisional Regulation is confirmed. |

2.2. Sales to related parties

|

(35) |

In the absence any comments with regard to the sales to related parties, the conclusions set out in recitals (102) to (103) of the provisional Regulation are confirmed. |

2.3. Imports from third countries

|

(36) |

As mentioned in the recitals (13) and (14), the round bars and bars without deformation are not part of the product concerned. The revised information presented in the tables, as set out in recital (103) of the provisional Regulation, is as follows:

|

|

(37) |

The correction of the figures above did not have any impact on the findings in recital (104) of the provisional Regulation. Indeed, throughout the period considered the prices of imports from the third countries were on average always higher than the prices of the Union industry. The only exporting country with lower average prices than the Union industry was Belarus in the IP which was the same year when volumes of imports from Belarus increased most rapidly. Therefore the Commission's findings in recital (104) of the provisional Regulation are confirmed. |

|

(38) |

With regard to the imports from third countries, the Belarusian exporting producer did not agree with the Commission's conclusion that individual market shares of third countries, with exception of Ukraine's, had increased only marginally. The Belarusian exporting producer supported its opinion with imports statistics for the year 2016, which is a period subsequent to the IP. Furthermore, it pointed out to an alleged discrepancy between the import figures reported in table 6.3.3 of the provisional Regulation and available Eurostat statistics. |

|

(39) |

In response to this claim, it should first be noted that post IP trends and data are normally not taken into account in the injury and causation analysis. While the Commission agreed in the recital (111) of the provisional Regulation to collect and review certain post IP data, it was undertaken in the context of the claims concerning the impact of so called ‘VAT fraud scheme’, the alleged subsequent gap between demand and supply of the product concerned on the markets of Poland and the Baltic States, and the abnormally high level of IP export volumes from Belarus allegedly resulting from that scheme. |

|

(40) |

Secondly, the Commission cannot base its finding concerning the effects of imports from third countries on post IP import figures presented by the interested party, since it should only analyse trends observed during the period considered (2012-2015), and on which it collected information during the investigation. As explained in recital (39), in this investigation, the Commission assessed limited post IP data to address an exceptional situation, that is, the VAT fraud scheme. Thus, the findings of recital (104) of the provisional Regulation which relate to changes of market shares of third countries during the period under consideration, which ends in 2015, were confirmed. |

|

(41) |

Even if the development of imports from third countries after IP were taken into account, it would not change the Commission's conclusion on the potential impact of these imports on the situation of the Union industry, as those prices remained higher than prices of imports from Belarus. |

|

(42) |

Finally, with regard to the alleged discrepancy between the import figures reported in the provisional Regulation and Eurostat statistics, it should be noted that the latter statistics include also import volumes of so-called high fatigue performance bars which are not part of the product scope of this procedure and were not reported in table 6.3.3 of the provisional Regulation (6). Taking into account the above, the claims of the Belarussian exporting producer concerning the impact of third countries' imports are rejected. |

|

(43) |

In the absence of other comments with regard to the imports from third countries, the conclusions set out in recital (104) of the provisional Regulation are confirmed. |

2.4. Costs evolution

|

(44) |

In the absence of any comments with regard to the costs evolution, the conclusion set out in recital (105) of the provisional Regulation is confirmed. |

2.5. Impact of the so-called ‘VAT fraud scheme’

|

(45) |

The Belarusian exporting producer reiterated in its submission the comments made at the provisional stage of the investigation with regard to the impact of the so-called VAT fraud scheme on the Union market, and claimed the Commission had failed to discharge its duty of investigating the matter. According to the exporting producer, this scheme was the main reason for the financial difficulties of some Union producers. As a result of this fraud scheme two producers located in Latvia (in early 2013) and Slovakia (in late 2014) went bankrupt and stopped production of the like product. Furthermore, one Union producer in Poland stopped the production of the like product for 3 months in 2014 due to upgrading its machinery. All these events together allegedly led to a shortage of supply mainly on the Polish and on the Baltic markets from 2013 onwards. This alleged gap would have been filled by the Belarusian exports. |

|

(46) |

The Belarusian exporting producer further claimed that, because of the VAT scheme, the year 2015 (IP) was an ‘unusual year’ in terms of high volumes of the product concerned exported to the Union and that export volumes started to decrease already at the end of the IP and continued decreasing after the IP. |

|

(47) |

In response to these claims, the Commission first looked into the exports data provided by the Belarusian statistics office and noted the following. The increase in the volume of exports by the exporting producer to the Union correlated with the decrease in the volume exports of the exporting producer to the Russian market. As described in the table below, between 2013 and 2015, the Belarusian exporting producer decreased its sales to Russia significantly by around 370 000 tonnes and increased its sales to the Union market by approximately the same amount, i.e. 380 000 tonnes.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

(48) |

Secondly, the Commission evaluated the situation on the Polish and the Baltic States' markets. Concerning 2013, Polish and Baltic states' markets were faced with the decrease of production of one Polish producer and the stop of production of one Latvian producer. Moreover, from 1 October 2013 the Polish government applied reverse charge VAT mechanisms to some 40 steel products, from fencing and pipes to finished flat-steel products as well as rebars, and thus tackling the VAT fraud scheme. The analysis of the export sales from Belarus to the Union market showed that the Belarusian exporting producer sales to Poland and the Baltic States remained stable, at around 110 000 tonnes compared with 2012. Therefore it is concluded that the Belarusian exporting producer did not take advantage of the alleged shortage of supply by the Union production in 2013 and that the other Union producers present in the market were able to supply the market either from stocks or by re-directing export sales to these markets (7). |

|

(49) |

Concerning 2014, one Polish producer stopped production for one quarter in order to upgrade its machinery and one Slovak producer stopped its production in August 2014 (the company was declared in bankruptcy in February 2015). The quantity not available as a result of those events is estimated at around 133 000 tonnes. |

|

(50) |

The analysis of the export sales from Belarus to the Union market showed that the Belarusian exporting producer sales to Poland and the Baltic States indeed increased by around 75 000 tonnes. However the exporting producer also increased its sales to other Union markets such as Germany from basically minimal quantities to around 120 000 tonnes. Therefore the argument that the Belarusian exporting producer increased its sales to the Union market only because of the exceptional market situation in Poland and the Baltic states is rejected, as it also increased (at even higher pace) its sales to other parts of the Union market where no exceptional circumstances existed. |

|

(51) |

Concerning the investigation period, the Latvian producer re-opened in March 2015. The Polish production was back to normal. Therefore, there was no longer an exceptional market situation in these parts of the Union market. |

|

(52) |

Despite this, the Belarusian exporting producer increased its sales to Poland even further and it maintained its sales to the Baltic States compared to 2014. Moreover the sharpest increase took place on other parts of the Union market (mainly in Bulgaria, the Netherlands, and Germany). |

|

(53) |

Therefore, it is concluded that the increase of the Belarusian exports to the European Union was not due to the gap between demand and supply in the Union market but to the redirection of the volume lost on the Russian market. Thus, the claim of inadequate assessment of the impact of the VAT fraud scheme in the provisional determination is unfounded and is, therefore, rejected. |

|

(54) |

In accordance with recital (111) of the provisional Regulation the Commission assessed the volume imports after the investigation period. The data showed that the imports from Belarus decreased somewhat, but they were still well above the 2013 levels and more or less at 2014 levels. Therefore the argument that the increase of imports from Belarus was temporary in nature and was explained by the particular market situation on certain Union market segments is rejected. |

|

(55) |

In the absence of other comments with regard to the VAT fraud scheme and post IP developments, the findings and conclusions set out in recitals (106) to (111) of the provisional Regulation are confirmed. |

3. Conclusion on causation

|

(56) |

In summary, the Commission considers that none of the arguments put forward by the interested parties after the provisional disclosure were able to alter the provisional findings which established a causal link between the dumped imports and the material injury suffered by the Union industry during the IP. Thus, the conclusions set out in recitals (112) to (115) of the provisional Regulation are confirmed. |

|

(57) |

The Commission has found that the only other factor that may have had an impact on the situation of the Union industry was imports from third countries, as stated in the recital (104) of the provisional Regulation. However, the Commission concluded that those imports could not break the causal link between Belarusian dumped imports and the material injury found to the Union industry and that the dumped imports from Belarus remained the main cause of injury. |

|

(58) |

Based on the above analysis, which distinguished and separated the effects of all known factors on the situation of the Union industry from the injurious effects of the dumped imports, it is concluded that the dumped imports from Belarus caused material injury to the Union industry within the meaning of Article 3(6) of the basic Regulation. |

G. UNION INTEREST

1. Interest of the Union industry

|

(59) |

In the absence of any comments with regard to the interest of the Union industry, the conclusions set out in recitals (117) to (122) of the provisional Regulation are confirmed. |

2. Interest of users and importers

|

(60) |

The Belarusian exporting producer claimed in its submissions that the Commission's assessment of Union interest did not take into account particular problems of importers and users located in the Baltic States. It claimed that, due to logistic reasons (such as, railway connections or certificate requirements), Belarus is the only source of supply of rebars for those companies. |

|

(61) |

In this regard, the Commission confirmed that the only cooperating user located in the Baltic States experienced certain technical problems with deliveries from the Union producers (none of them being located in the Baltic States). On the other hand, this company stated that purchases from Belarus could be, and in the post IP period effectively were, replaced by purchases from Russia and to some extent also from Ukraine. |

|

(62) |

Furthermore, the Commission received very low cooperation from the companies located in the Baltic States, which seems to indicate that they do not perceive that they would be negatively affected by potential antidumping measures concerning Belarusian imports of the product concerned. |

|

(63) |

In the absence of other comments with regard to the interest of the users and importers, the conclusions set out in recitals (123) to (131) and recital (134) of the provisional Regulation are confirmed. |

3. Potential absorption of the duties

|

(64) |

In its submission after the provisional disclosure, the complainant claimed that the level of antidumping duty proposed at provisional stage (12,5 %) would not be sufficient, as the measure could easily be absorbed by the Belarusian exporting producer, which is a state-owned company, located in a non-market economy country with alleged favourable access to the subsidized raw material metal scrap. |

|

(65) |

With regard to this claim, it should be stressed that the potential absorption can only be a matter of a separate anti-absorption investigation on the basis of Article 12 of the basic Regulation and cannot affect in advance the level of antidumping measures imposed in the original investigation. Furthermore, the evidence available in this investigation does not support the allegation of the easy access to a subsidized raw material by the Belarusian producer; in fact, the Commission found that the company purchases most of its raw material from Russia and Ukraine, countries considered as market economies. |

4. Strategic importance of the EU-Belarus cooperation in the steel sector

|

(66) |

In its submission after the provisional disclosure, the Belarussian exporting producer and the Belarussian authorities referred to the strategic importance of the cooperation with the EU in the steel sector, and the fact that measures may negatively affect Belarusian purchases of capital equipment in the Union, the establishment of network of related trading companies in the Union, and any cooperation with European financial institutions. |

|

(67) |

In response to this point, the Commission underlines that the measures have as sole purpose to restore a level playing field on the Union market. It is not of a punitive nature. If the exporting producer increases its prices durably, so that dumping ceases to exist, it can ask for a refund and an interim review. Therefore, the Commission does not consider those considerations to be relevant for the assessment of Union interest. |

5. Conclusion on Union interest

|

(68) |

In summary, none of the arguments put forward by the interested parties demonstrates that there are compelling reasons against the imposition of measures on imports of the product concerned from Belarus. Any negative effects on unrelated users and importers can be mitigated by the availability of alternative sources of supply. Moreover, when considering the overall impact of the anti-dumping measures on the Union market, the positive effects, in particular on the Union industry, appear to outweigh the potential negative impacts on the other interested parties. Thus, the conclusions set out in recitals (135) to (137) of the provisional Regulation are confirmed. |

H. DEFINITIVE ANTI-DUMPING MEASURES

1. Injury elimination level (injury margin)

1.1. Target profit

|

(69) |

Following provisional disclosure, the Union industry contested the target profit used in order to determine the injury elimination level as set out in recital (143) of the provisional Regulation. The same claims were reiterated after final disclosure. |

|

(70) |

The target profit used in the provisional injury margin calculations amounted to 4,8 %. This figure was based on the 2012 profit margin found for a very similar product, HFP rebars, and used in the recent anti-dumping procedure concerning imports of HFP rebars originating in China (8). |

|

(71) |

The complainant in its submission contested the use of the same target profit used in the HFP rebars investigation and claimed that these two products and their respective markets are different. The complainant suggested using a target profit even higher than originally proposed in the complaint, 16 % or 17 %, which was the profit achieved by the Union producers in 2006 or considered ‘desirable in the long term for the sound steel industry’ (9). |

|

(72) |

In this regard, the target profit used in these proceedings, which the Commission found to be the most appropriate, is based on the figure actually achieved in 2012 (which is within the period considered) by the Union producers of a very similar product manufactured to a large extent using the same facilities for production of the product concerned in this investigation. It is also recalled that in the complaint EUROFER requested a target profit of 9,9 %, which was used in an investigation on wire rod, a product definitely more distant from the product concerned than HFP rebars. Finally, the purpose of the establishment of the injury margin is to remove the part of injury caused by dumped imports, but not by other factors such as the economic crisis. While the profit of 1,3 %, which was the only profit achieved by the Union industry in the period considered (10), was found to be inappropriate due to the impact of the VAT fraud scheme, it appears more congruous to use a profit margin that was achieved by the industry in the same period, verified and found appropriate for a very similar product in an antidumping procedure with mostly overlapping periods. The claim of the Union industry is therefore rejected. |

1.2. Post importation costs

|

(73) |

In the provisional calculation of the injury margin, an adjustment of 2 % was used for post-importation costs (11). In its submission after provisional disclosure, the Belarusian exporting producer claimed that in this particular case a higher figure of 4-6 % should be used, since this level of adjustment would better reflect the actual post-importation costs the importers/users have to cover. |

|

(74) |

Following this claim, the Commission looked in more detail into the level and structure of the importation and post-importation costs declared by the cooperating importer and users referred to in recital (6). |

|

(75) |

Based on the findings of the verification visits of these companies, the Commission does not find grounds to change the level of adjustment. The actual post importation costs for the importer and one of the users were (on average for the whole IP) below 2 %. Only for one company (the German user), post importation costs were higher than 2 %, within the claimed range of 4-6 %. However, this company had non-standard post importation operations for the transport of the product concerned from its warehouses to inland production sites. These are not standard post-importation costs, common to importers, but costs very specific to this company's operation. It should be stressed that, for the purpose of the injury margin calculations, export prices are established at an EU border level (adjusted for post-importation costs) and compared with ex works prices of the Union producers. Costs of transportation of the product to the users' production sites are not relevant in this context and thus are not taken into account. Based on the above, the Commission confirms the post-importation cost established at provisional stage at 2 % as reasonable. The claim is therefore rejected. |

1.3. Other issues concerning injury margin calculation

|

(76) |

After provisional disclosure, both the complainant and the Belarussian exporting producer raised several additional minor points with regard to the injury margin calculations. |

|

(77) |

The complainant indicated that the establishment of the CIF price for the undercutting and underselling calculations should not be based on transfer price to related importers but recalculated from the independent re-sales. The Commission hereby confirms that in fact the CIF price used for the calculation of undercutting and underselling at the provisional stage is based on independent re-sales. |

|

(78) |

The complainant proposed an ‘alternative’ method of cost allocation between different types of product for the calculation of undercutting and underselling. However, this proposal was made after provisional measures when all the questionnaire replies were already verified on spot and calculations completed. In any event, cost allocation is irrelevant for the injury margin calculation in this case, as the injury margin was based on per product type ex-work prices and not on per product type costs. The claim is therefore rejected. |

|

(79) |

The complainant also proposed to base the injury margin not on the data of the whole IP but on a chosen quarter of IP where the margin would be ‘more representative’. However, the complainant failed to provide any evidence that there are any special circumstances in this case which would justify departing from the standard practice of the Commission to base the injury margin on the whole IP. The claim is therefore rejected. |

|

(80) |

The Commission has decided to apply caution as far as the calculation of the injury margin is concerned. Indeed, given the unreliability of certain data for the reasons set out above at recitals (19) to (23) and the specificities of this case, the Commission has revised the calculation of the the injury elimination level by excluding data from the sampled Italian producer and limiting the calculation to sales in the Netherlands, Germany, Poland, and Lithuania. This calculation is a mirror of the undercutting calculation mentioned above in recital (29) that resulted in an undercutting margin of 2,8 %. On this basis, the revised injury margin is established at a level 10,6 %. |

|

(81) |

After final disclosure, the complainant contested the methodology followed by the Commission in this case, on the grounds that the Commission had de facto narrowed down the scope of the investigation to reduce it to a regional investigation. It also claimed that the above injury elimination level would not remove injury to the overall Union industry. The complainant further noted that the Belarussian dumped imports took place in 16 different Member States, i.e. many more than those used by the Commission for its establishment of the injury margin. |

|

(82) |

In this respect, it should be noted that the Commission has actually based his injury analysis on the situation of the overall Union industry, and has concluded that removing Italy from the assessment does not change the injury picture. As far as the injury elimination level is concerned, even though imports from Belarus indeed took place in a number of Member States (in fact 13), the Commission based the injury elimination calculations on the data pertaining only to the companies in the sample, which sold the like product in a more limited number of countries, for the reasons explained in recital (29). This is without prejudice to the possibility, for all interested parties, to request an interim review once the findings of the cartel investigation are finalized, and depending on the situation prevailing at that time. |

1.4. Conclusion on injury elimination level

|

(83) |

In the absence of any other comments regarding the injury elimination level, the level of the definitive injury elimination level is established at 10,6 %. |

2. Definitive measures

|

(84) |

In view of the conclusions reached with regard to dumping, injury, causation and Union interest, and in accordance with Article 9(4) of the basic Regulation, definitive anti-dumping measures should be imposed on the imports of the product concerned at the level of the injury margin, in accordance with the lesser duty rule. |

|

(85) |

After final disclosure the Belarussian exporting producer claimed that the circumstances of the case justified the imposition of measures under the form of a partial duty free amount, i.e. that the first 200 000 tons imported would be free of duty, and that the duration of the measures should be limited to two years. |

|

(86) |

It is recalled that dumping results from price discrimination and therefore the remedy should consist of anti-dumping duties or a price undertaking. A duty free quota as requested by the Belarussian exporter does not contain any price element which would remedy injurious dumping and can therefore not be accepted. In this case there is also no justification for reducing the period of application of the measures. Should the circumstances change, the Belarussian has the possibility to request a review of the measures pursuant to Article 11(3) of the basic Regulation. The claims are therefore rejected. It is also recalled that the Commission may revisit the findings should the cartel investigation put in question the definitive findings set out in this regulation. |

|

(87) |

On the basis of the above, the rate at which such duties will be imposed are set as follows:

|

3. Definitive collection of the provisional duties

|

(88) |

In view of the dumping margins found and given the level of the injury caused to the Union industry, the amounts secured by way of the provisional anti-dumping duty, imposed by the provisional Regulation, should be definitively collected. |

|

(89) |

The Committee established by Article 15(1) of Regulation (EU) 2016/1036 did not deliver an opinion, |

HAS ADOPTED THIS REGULATION:

Article 1

1. A definitive anti-dumping duty is imposed on imports of certain concrete reinforcement bars and rods, made of iron or non-alloy steel, not further worked than forged, hot-rolled, hot-drawn or hot-extruded, whether or not twisted after rolling, containing indentations, ribs, grooves or other deformations produced during the rolling process. High fatigue performance iron or steel concrete reinforcing bars and rods are excluded. Other long products, such as round bars are excluded. The product is originating in Belarus and is currently falling within CN codes ex 7214 10 00, ex 7214 20 00, ex 7214 30 00, ex 7214 91 10, ex 7214 91 90, ex 7214 99 10 and ex 7214 99 95 (TARIC codes: 7214100010, 7214200020, 7214300010, 7214911010, 7214919010, 7214991010, 7214999510).

2. The rate of the definitive anti-dumping duty applicable to the net, free-at-Union-frontier price, before duty, of the product described in paragraph 1 shall be 10,6 %.

3. Unless otherwise specified, the provisions in force concerning customs duties shall apply.

Article 2

The amounts secured by way of the provisional anti-dumping duties pursuant to the Implementing Regulation (EU) 2016/2303 shall be definitively collected.

Article 3

This Regulation shall enter into force on the day following that of its publication in the Official Journal of the European Union.

This Regulation shall be binding in its entirety and directly applicable in all Member States.

Done at Brussels, 16 June 2017.

For the Commission

The President

Jean-Claude JUNCKER

(1) OJ L 176, 30.6.2016, p. 21.

(2) OJ C 114, 31.3.2016, p. 3.

(3) Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2016/2303 of 19 December 2016 imposing a provisional anti-dumping duty on imports of certain concrete reinforcement bars and rods originating in the Republic of Belarus (OJ L 345, 20.12.2016, p. 4).

(4) Judgment in Extramet v Council, C-358/89, EU:C:1992:257, paragraphs 17 to 20. See also, by analogy, judgments in Matra v Commission, C-225/91, EU:C:1993:239, paragraphs 40 to 47; in RJB Mining v Commission, T-156/98, EU:T:2001:29, paragraphs 107 to 126; and in Secop v Commission, T-79/14, EU:T:2016:118, 79 to 86.

(5) Case I742.

(6) Namely, export volumes to Ireland and UK were excluded.

(7) Analiza wplywu zmian administracyjnych na wielkosc szarej strefy na rynku pretow zbrojeniowych i sytuacje sektora finansow publicznych' Ernst & Young, Warsaw March 2014.

(8) OJ L 204, 29.7.2016, p. 70.

(9) By McKinsey report delivered to the OECD Steel Committee meeting December 2013.

(10) Profit achieved in a year 2012; for the other years of the period considered, i.e. 2013-2015, the Union producers recorded a loss.

(11) Specific disclosure received by the interested parties Annex 3.

DECISIONS

|

17.6.2017 |

EN |

Official Journal of the European Union |

L 155/21 |

COUNCIL IMPLEMENTING DECISION (EU) 2017/1020

of 8 June 2017

on the launch of automated data exchange with regard to vehicle registration data in Croatia

THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION,

Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union,

Having regard to Council Decision 2008/615/JHA of 23 June 2008 on the stepping up of cross-border cooperation, particularly in combating terrorism and cross-border crime (1), and in particular Article 33 thereof,

Having regard to the opinion of the European Parliament (2),

Whereas:

|

(1) |

In accordance with Article 25(2) of Decision 2008/615/JHA, the supply of personal data provided for under that Decision may not take place until the general provisions on data protection set out in Chapter 6 of that Decision have been implemented in the national law of the territories of the Member States involved in such supply. |

|

(2) |

Article 20 of Council Decision 2008/616/JHA (3) provides that the verification that the condition referred to in recital 1 has been met with respect to automated data exchange in accordance with Chapter 2 of Decision 2008/615/JHA is to be done on the basis of an evaluation report based on a questionnaire, an evaluation visit and a pilot run. |

|

(3) |

In accordance with point 1.1 of Chapter 4 of the Annex to Decision 2008/616/JHA, the questionnaire drawn up by the relevant Council Working Group concerns each of the automated data exchanges and is to be answered by a Member State as soon as it believes it fulfils the prerequisites for sharing data in the relevant data category. |

|

(4) |

Croatia has completed the questionnaire on data protection and the questionnaire on vehicle registration data (VRD) exchange. |

|

(5) |

A successful pilot run has been carried out by Croatia with the Netherlands. |

|

(6) |

An evaluation visit has taken place in Croatia and a report on the evaluation visit has been produced by the Dutch and Romanian evaluation team and forwarded to the relevant Council Working Group. |

|

(7) |

An overall evaluation report, summarising the results of the questionnaire, the evaluation visit and the pilot run concerning VRD exchange, has been presented to the Council. |

|

(8) |

On 19 December 2016, the Council, having noted the agreement of all Member States bound by Decision 2008/615/JHA, concluded that Croatia had fully implemented the general provisions on data protection set out in Chapter 6 of Decision 2008/615/JHA. |

|

(9) |

Therefore, for the purposes of automated searching of VRD, Croatia should be entitled to receive and supply personal data pursuant to Article 12 of Decision 2008/615/JHA. |

|

(10) |

In its judgment of 22 September 2016 in Joined Cases C-14/15 and C-116/15 (4), the Court of Justice of the European Union held that Article 25(2) of Decision 2008/615/JHA unlawfully lays down the requirement of unanimity for the adoption of measures necessary to implement that Decision. |

|

(11) |

However, Article 33 of Decision 2008/615/JHA confers upon the Council implementing powers with a view to adopting measures necessary to implement that Decision, in particular as regards the receiving and supply of personal data provided for under that Decision. |

|

(12) |

As the conditions for triggering the exercise of such implementing powers have been met and the procedure in this regard has been followed, an Implementing Decision on the launch of automated data exchange with regard to VRD in Croatia should be adopted in order to allow that Member State to receive and supply personal data pursuant to Article 12 of Decision 2008/615/JHA. |

|

(13) |

Denmark is bound by Decision 2008/615/JHA and is therefore taking part in the adoption and application of this Decision which implements Decision 2008/615/JHA. |

|

(14) |

The United Kingdom and Ireland are bound by Decision 2008/615/JHA and are therefore taking part in the adoption and application of this Decision which implements Decision 2008/615/JHA, |

HAS ADOPTED THIS DECISION:

Article 1

For the purposes of automated searching of vehicle registration data, Croatia is entitled to receive and supply personal data pursuant to Article 12 of Decision 2008/615/JHA as from 18 June 2017.

Article 2

This Decision shall enter into force on the day following that of its publication in the Official Journal of the European Union.

This Decision shall apply in accordance with the Treaties.

Done at Luxembourg, 8 June 2017.

For the Council

The President

U. REINSALU

(2) Opinion of 13 February 2017 (not yet published in the Official Journal).

(3) Council Decision 2008/616/JHA of 23 June 2008 on the implementation of Decision 2008/615/JHA on the stepping up of cross-border cooperation, particularly in combating terrorism and cross-border crime (OJ L 210, 6.8.2008, p. 12).

(4) Judgment of the Court of Justice of 22 September 2016, Parliament v Council, Joined Cases C-14/15 and C-116/15, ECLI:EU:C:2016:715.

|

17.6.2017 |

EN |

Official Journal of the European Union |

L 155/23 |

COMMISSION DECISION (EU) 2017/1021

of 10 January 2017

on State aid SA.44727 2016/C (ex 2016/N) which France is planning to implement in favour of the Areva group

(notified under document C(2016) 9029)

(Only the French text is authentic)

(Text with EEA relevance)

THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION,

Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, and in particular the first subparagraph of Article 108(2) thereof,

Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Atomic Energy Community,

Having regard to the Agreement on the European Economic Area, and in particular Article 62(1)(a) thereof,

Having called on interested parties to submit their comments pursuant to those articles (1), and having regard to their comments,

Whereas:

1. PROCEDURE

|

(1) |

On 29 April 2016, after pre-notification contacts, the French authorities notified to the Commission restructuring aid in favour of the Areva group (‘the Areva Group’) in the form of two capital injections by the French State. The French authorities sent additional information to the Commission by letters dated 27 May and 6 July 2016. |

|

(2) |

By letter dated 19 July 2016, the Commission informed the French authorities that it had decided to initiate the procedure laid down in Article 108(2) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (‘TFEU’) in respect of the aid. The French authorities sent their comments on that decision to the Commission by letter dated 12 September 2016. |

|

(3) |

The Commission decision to initiate the procedure (‘the opening decision’) was published in the Official Journal of the European Union (2) on 19 August 2016. The Commission called on interested parties to submit their comments. |

|

(4) |

The Commission received comments within the deadline from the following interested parties: Urenco, Teollisuuden Voima Oyj (‘TVO’), Siemens, the Areva Group, and a third party who wished to remain anonymous. It forwarded them to France, giving it the opportunity to comment on them, and received its comments by letter of 18 October 2016. |

|

(5) |

The French authorities sent a number of additional comments on 30 November and again on 7, 12, 21 and 22 December 2016. |

|

(6) |

In parallel to the proceedings in respect of the restructuring aid, on 27 July 2016 the French authorities notified to the Commission rescue aid of EUR 3.3 billion in the form of two loans to the Areva Group, one of EUR 2 billion granted to the parent company Areva SA (‘Areva SA’), and the other of EUR 1.3 billion to its wholly owned subsidiary New Areva (‘New Areva’) (3). These loans are to be converted into capital in these two entities when the capital injections at issue in this Decision are made. The notified rescue aid, registered under number SA.46077, is the subject of a separate decision. |

2. DETAILED DESCRIPTION OF THE AID

2.1. Beneficiary and background to the granting of the aid

2.1.1. Overview of the Areva Group

|

(7) |

The Areva Group is listed on the stock exchange. The French State directly or indirectly controls 86,52 % of it. The State directly owns 28,83 % of the parent company, Areva SA, and indirectly owns 54,37 % and 3,32 %, via the Atomic Energy Commission (Commissariat à l'Énergie Atomique, ‘CEA’) and Bpifrance Participations respectively. Areva SA controls the various Areva Group subsidiaries in the proportions shown in Figure 2 below. |

|

(8) |

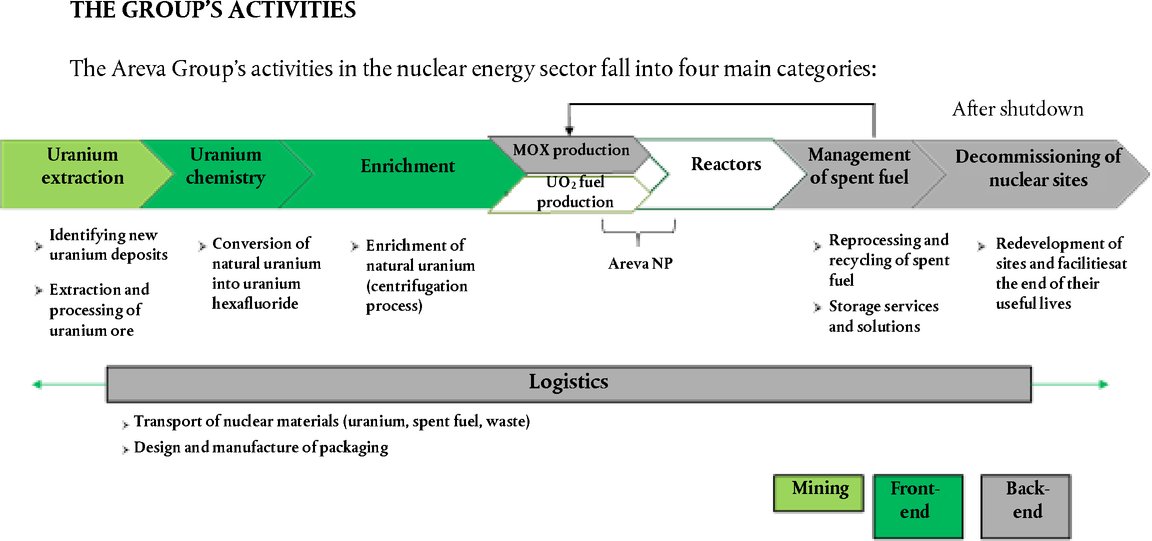

The Areva Group is active in the whole range of nuclear-cycle activities, through four business lines:

|

|

(9) |

The group's operations also include renewable energies, though this activity is on a smaller scale and is currently being rationalised. It accounted for less than 1 % of the Areva Group's turnover in 2015. |

|

(10) |

These four business lines can be grouped into two main historically distinct and complementary activities: (i) nuclear fuel cycle management, comprising mining, and front-end and back-end operations, and (ii) reactors. The first was carried on by Cogema and the second by Framatome, before these two entities merged in 2001 to form the Areva Group. Figure 1 Overview of the Areva Group's activities

|

|

(11) |

The distinction between the two main business categories was carried over into the organisation chart for the merged Areva Group, as shown in Figure 2. The reactors business was housed in the subsidiary Areva Nuclear Power (‘Areva NP’) (and, where naval propulsion was concerned, in Société Technique pour l'Énergie Atomique (‘Areva TA’)), while the fuel cycle business was divided between Areva Nuclear Cycle (‘Areva NC’) for the front end and back end of the cycle, and the subsidiary ‘Areva Mines’ for mining activities. Nuclear fuel assembly, despite being linked to the fuel cycle, was housed in Areva NP because of the close synergies between assembly and reactor design (5). Figure 2 Simplified organisation chart for the Areva Group as at 31 December 2014

|

|

(12) |

As at 31 December 2015 the Areva Group employed 39 537 people. In 2015 its total turnover came to EUR 8,2 billion, compared with EUR 8,3 billion in 2014. However, applying IFRS Standard 5 on Non-current Assets Held for Sale and Discontinued Operations (6) resulted in a published turnover for the Areva Group of EUR 4,2 billion. |

2.1.2. The difficulties encountered by the Areva Group

|

(13) |

The difficulties encountered by the Areva Group arise first from the consequences of the sharp downturn in the nuclear market and from the adverse economic and financial conditions since 2008. Second, the Areva Group made significant losses on a small number of industrial projects. Lastly, its profitability fell as a result of certain acquisitions and the development of certain activities. |

|

(14) |

Regarding the first difficulty, the accident at Fukushima in 2011 contributed to a rapid downturn in nuclear markets. Since that date, a number of reactors have been shut down and countries such as Germany and Switzerland have decided to pull out of nuclear energy. Plans for new power stations in countries such as China have also been put on hold. Both the fuel and the reactor markets have been affected, and the Areva Group's results have suffered as a consequence. |

|

(15) |

With sources of long-term financing drying up as a result of the financial crisis in 2008 and the entry into force of new prudential rules, it has become more difficult to finance capital-intensive projects such as nuclear power stations. |

|

(16) |

Moreover, the contraction of the market and the resulting overcapacity hit at a time when the Areva Group had decided to invest in modernisation and was facing an increase in its operating costs. This had a direct impact on its cash flows and forced it to resort to debt to finance its short-term operations. At the same time, in view of the deteriorating market outlook, the Areva Group had to write down assets. |

|

(17) |

Regarding the second difficulty, the Areva Group accumulated major losses on a number of industrial projects, the most important of which is the construction of a new-generation nuclear plant at Olkiluoto in Finland (‘OL3 project’) for TVO. |

|

(18) |

The project is being led by a consortium (‘the Consortium’) formed in 2003 by the Areva Group, through Areva NP and its subsidiary Areva GmbH (‘Areva GmbH’), and Siemens. The project is some nine years behind schedule and has overrun its costs, resulting in a loss on completion for the Areva Group estimated at EUR 5,5 billion (7). The Areva Group has issued a liability guarantee, via its parent company Areva SA, in favour of its customer TVO, although according to the French authorities questions remain regarding its validity and scope. |

|

(19) |

The OL3 project is the subject of a major arbitration case between the Consortium and TVO, with each party claiming that the other is responsible for the significant delays and cost overruns at the site. The parties are seeking several billion euros in compensation from each other. […] (*1). |

|

(20) |

The Consortium and TVO had started negotiating an overall settlement, contractually setting a new provisional date for delivery (8) […], in order to resolve the arbitration dispute […] (9).[…]. |

|

(21) |

The French authorities also gave details of the losses associated with the JHR projects (Jules Horowitz Reactor — a planned materials testing reactor under construction at CEA's Cadarache site) and […] (upgrade of the […] reactor at the […] plant), which have generated losses of several hundred million euros to date. |

|

(22) |

Lastly, regarding the third difficulty, the financial health of the Areva Group also deteriorated as a result of unprofitable acquisitions and development projects, in particular in mining (the acquisition of Uramin, for example, gave rise to losses of close on EUR […]) and in renewable energy. |

|

(23) |

For all these reasons, the Areva Group has recorded substantial accumulated losses in excess of EUR 9 billion over the financial years 2011 to 2015. The Areva Group financed these losses and the investments needed to modernise its industrial plant (10) with debt, via both banks (‘banking debt’) and the capital markets (‘bond debt’). After it drew down new banking lines in early 2016, its debt on 5 January 2016 stood at EUR 9,4 billion (11), EUR 6 billion of which was bond debt. |

|

(24) |

In view of the outlook for the Areva Group, its capital structure does not allow it to cover its debts, which is why the French authorities have launched a wide-ranging restructuring exercise in cooperation with the Areva Group. |

2.2. Areva Group's restructuring plan

|

(25) |