EUROPEAN COMMISSION

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Brussels, 19.12.2017

SWD(2017) 469 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

REFIT EVALUATION

Accompanying the document

Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council

laying down rules and procedures for compliance with and enforcement of Union harmonisation legislation on products and amending Regulations (EU) No 305/2011, (EU) No 528/2012, (EU) 2016/424, (EU) 2016/425, (EU) 2016/426 and (EU) 2017/1369 of the European Parliament and of the Council, and Directives 2004/42/EC, 2009/48/EC, 2010/35/EU, 2013/29/EU, 2013/53/EU, 2014/28/EU, 2014/29/EU, 2014/30/EU, 2014/31/EU, 2014/32/EU, 2014/33/EU, 2014/34/EU, 2014/35/EU, 2014/53/EU, 2014/68/EU and 2014/90/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council

{COM(2017) 795 final}

{SWD(2017) 466 final}

{SWD(2017) 467 final}

{SWD(2017) 468 final}

{SWD(2017) 470 final}

Contents

1.Introduction

2.Background to the initiative

2.1.Description of the initiative and its objectives

2.1.1.Objectives and roles of the market surveillance provisions

2.1.2.Scope of the evaluation

2.1.3.Complementary nature of the market surveillance provisions

2.2.Consumer Safety and Market Surveillance Package (2013)

2.3.Baseline

2.3.1.Regulatory aspects

2.3.2.Level of non-compliance in 2008

3.Evaluation Questions

4.Method

4.1.Sources

4.2.Limitations – robustness of findings

5.Implementation state of play (Results)

5.1.Market surveillance structures and measures

5.2.Additional information

5.2.1.Exchange of information (ICSMS, notifications of restrictive measures, national market surveillance programmes and reports on activities)

5.2.2.Cooperation

5.2.3.Infringement proceedings

6.Answers to the evaluation questions

6.1.Effectiveness

6.1.1.Enhanced cooperation among Member States

6.1.2.Uniform and sufficiently rigorous level of market surveillance

6.1.3.Border controls of imported products

6.1.4.Conclusion as regards EQ1

6.2.Efficiency

6.3.Relevance

6.4.Coherence

6.5.EU added value

7.Conclusions

7.1.Effectiveness

7.2.Efficiency

7.3.Relevance

7.4.Coherence

7.5.EU added value

7.6.REFIT potential

Glossary

|

Product

|

A substance, product or good produced through a manufacturing process other than food, living plants and animals, products of human origin and products of plants and animals relating directly to their future reproduction (Article 15(4) of Regulation (EC) No 765/2008 or 'the Regulation').

|

|

Market surveillance provisions

|

Articles 15 to 29, Article 38 and Article 41 of Regulation (EC) No 765/2008 and the corresponding definitions and financing provisions,

|

|

Market surveillance

|

The activities carried out and measures taken by public authorities to ensure that products comply with the requirements set out in the relevant Union harmonisation legislation and do not endanger health, safety or any other aspect of public interest protection (Article 2(17) of the Regulation).

|

|

Market surveillance authority or MSA

|

An authority of a Member State responsible for carrying out market surveillance on its territory.

|

|

Union harmonisation legislation

|

Any Union legislation harmonising the conditions for the marketing of products (Article 2(21) of the Regulation).

|

|

Sector legislation

|

Legislation that is part of the Union harmonisation legislation.

|

|

GPSD

|

General Product Safety Directive - Directive 2001/95/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 3 December 2001 on general product safety

|

|

Manufacturer

|

Any natural or legal person who manufactures a product or has a product designed or manufactured, and markets that product under his name or trademark (Article 2(3) of the Regulation).

|

|

Authorised representative

|

Any natural or legal person established within the Community who has received a written mandate from a manufacturer to act on his behalf in relation to specified tasks with regard to the latter's obligations under the relevant Union legislation (Article 2(4) of the Regulation).

|

|

Importer

|

Any natural or legal person established within the Union who places a product from a third country on the Union market (Article 2(5) of the Regulation).

|

|

Distributor

|

Any natural or legal person in the supply chain, other than the manufacturer or the importer, who makes a product available on the market (Article 2(6) of the Regulation)

|

|

Economic operators

|

The manufacturer, the authorised representative, the importer and the distributor (Article 2(7) of the Regulation).

|

|

AdCo

|

The Administrative Coordination group of the authorities responsible for market surveillance with respect to one or more instruments of Union harmonisation legislation.

|

|

Recall

|

Any measure aimed at achieving the return of a product that has already been made available to the end user (Article 2(14) of the Regulation).

|

|

Withdrawal

|

Any measure aimed at preventing a product in the supply chain from being made available on the market (Article 2(15 of the Regulation)).

|

|

Making available on the market

|

Any supply of a product for distribution, consumption or use on the Union market in the course of a commercial activity, whether in return for payment or free of charge (Article 2(1) of the Regulation)

|

|

Placing on the market

|

The initial making available of a product on the Union market (Article 2(2) of the Regulation).

|

|

RAPEX

|

Rapid alert system for the transmission among all competent market surveillance authorities in the EU of information on measures taken against products presenting a serious risk – ec.europa.eu/consumers/consumers_safety/safety_products/rapex/index_en.htm (system referred to in Article 22 of the Regulation).

|

|

ICSMS

|

Internet-supported information and communication system for market surveillance authorities in the EU -

https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/icsms/

(system referred to in Article 23 of the Regulation).

|

A large range of non-food consumer products (like toys, mobile phones, electrical appliances, laptops etc.) and more sophisticated products (e.g. machines, pressure equipment, measuring instruments, equipment to be used in explosive atmospheres etc.) sold on the Single Market are subject to common EU rules concerning public safety, security, environmental protection, etc. This set of rules is referred to as Union technical legislation.

Regulation (EC) No 765/2008 setting out the requirements for accreditation and market surveillance relating to the marketing of products and repealing Regulation (EEC) No 339/93 (hereinafter also referred to as “the Regulation”) was adopted to address the lack of coherence in the implementation and enforcement of Union technical legislation ensuring the free movement of non-food products (hereinafter also referred to as “products”) within the EU. The purpose of the Regulation is therefore to ensure that these products are subject to adequate controls by public authorities so that if found to be, for instance, dangerous for consumers, workers or the environment, they could be taken off the EU market promptly.

The Regulation has four main elements:

(1)It lays down rules on the organisation and operation of accreditation of conformity assessment bodies performing conformity assessment activities;

(2)It lays down the general principles of the CE marking;

(3)It provides a framework for the market surveillance of products to ensure that those products fulfil the requirements providing a high level of protection for public interests, such as health and safety in general, health and safety at the workplace, the protection of consumers and the protection of the environment and security.

(4)It provides a framework for controls on products from third countries.

This evaluation only relates to the third and fourth element above, i.e. the framework for the market surveillance of products and for controls on products from third countries. Therefore, it focuses on Articles 15 to 29, Article 38 and Article 41 of the Regulation and the corresponding definitions and financial provisions of the Regulation (hereinafter 'market surveillance provisions').

The purpose of this evaluation is to assess the effectiveness, efficiency, coherence, relevance and EU added value of the market surveillance provisions on the basis of the evaluation questions set out in section 3. Its results feed into the impact assessment that will accompany the legislative proposal strengthening the enforcement of Union harmonisation legislation on products. This proposal is one of the deliverables of the Single Market Strategy, according to which the Commission will 'launch a comprehensive set of actions to further enhance efforts to keep non-compliant products from the EU market by strengthening market surveillance and providing the right incentives to economic operators'.

This evaluation covers the period from 2010 (date of application of the Regulation) until 2015, compared to the situation before 2010. It is part of the Commission's work programme, according to which 'the Commission will act to strengthen the single market in goods, notably by facilitating the mutual recognition and addressing the increasing amount of non-compliant products on the EU market through REFIT revisions of the relevant legislation. This will allow entrepreneurs to offer their products more easily across borders while offering incentives to boost regulatory compliance and restoring a level playing field to the benefit of businesses and citizens.'

The findings of the evaluation suggest that while its main goal to ensure that products sold on EU market are safe and compliant with applicable rules remains extremely relevant, the Regulation has been only partly effective in achieving its objectives. As a consequence the legal framework for product controls and its implementation should be further improved.

|

2.Background to the initiative

|

2.1.Description of the initiative and its objectives

2.1.1.Objectives and roles of the market surveillance provisions

The intervention logic of Regulation (EC) No 765/2008 could be summarised as follows. Three main needs or drivers led to the definition of the Regulation’s strategic objectives: (1) to address the lack of market surveillance enforcement within the EU; (2) to increase credibility of CE marking in the internal market; and (3) to ensure the free movement of goods within the EU, together with product safety and the protection of public interests. The two strategic objectives of the Regulation – aiming to respond to the abovementioned needs - are to (1) ensure a level playing field among economic operators through the elimination of unfair competition of non-compliant products and to (2) strengthen the protection of public interests through the reduction of the number of non-compliant products. The strategic objectives are then disaggregated into three specific objectives representing the operational orientations of the EU action. In order to achieve the strategic and specific objectives, the EC has defined a set of activities to be implemented, including those in the Regulation in the form of provisions. For instance, in order to achieve a reduction in the number of non-compliant products, the Regulation sets the framework for controls of products on the internal market (Ch. III, section 2) and of those imported from third countries (Ch. III, section 3). These provisions are expected to produce a number of key results and to eventually trigger the Regulation’s impacts. For instance, the resulting lower number of non-compliant products will generate a higher and more uniform protection of consumers across the EU.

The figure below outlines the Regulation’s intervention logic in relation to the evaluation criteria and questions that guided the study and that will be further described in the following chapter. The arrows represent the links/trigger mechanisms between needs and objectives, and objectives, provisions and results.

The intervention logic below also presents the evaluation questions (and related criteria) helping in the assessment of the overall performance of the market surveillance provisions, having identified its working mechanisms. As shown in the figure below, the evaluation questions relating to relevance assess whether the objectives of the market surveillance provisions are still adequate in the current context. The effectiveness questions are based on measurements of the market surveillance provisions’ results to determine whether it has achieved its objectives. The efficiency questions assess whether the market surveillance provisions have proportionally delivered their results, given the established provisions. In order to better understand how the interaction among the above elements works and delivers the expected changes over time, the intervention logic needs to consider external factors (including other EU legislation) that may influence the performance of the market surveillance provisions: the coherence questions evaluate whether these provisions are consistent with those factors. The EU added value questions aim at understanding if the provisions set out have served to obtain the expected impacts.

Figure 1: Intervention logic

2.1.2.Scope of the evaluation

This evaluation only relates to the market surveillance provisions, i.e. the following parts of the Regulation:

·Chapter I – General provisions: This Chapter specifies the scope of the Regulation and the main definitions relevant for market surveillance.

·Chapter III – EU market surveillance framework and controls of products entering the EU market. Chapter III covers the functioning of market surveillance of products subject to the EU harmonisation legislation. It defines the products covered by the market surveillance infrastructures and programmes, as well as the roles and responsibilities of the European Commission, Member States, national Market surveillance authorities and other relevant actors.

–In particular, Section 1 defines the scope of application of the provisions on market surveillance and control of imported products. It also sets out the general obligation to carry out market surveillance and take restrictive measures for products found to be dangerous or in any case non-compliant in relation to any product categories subject to EU harmonisation law and to inform the European Commission and other Member States.

–Section 2 “EU market surveillance framework” sets out the obligations of the EU MS regarding the organisation of national authorities and measures to be adopted in the case of products presenting a serious risk. The Section provides an overview of the duties of national Market surveillance authorities and their cooperation with competent authorities in other EU MS or in third countries. The Regulation also states the principles of cooperation and exchange of information between all relevant actors in the field of market surveillance.

–Section 3 “Controls of products entering the EU market” entrusts powers and resources to authorities in charge of external border control of products entering the EU market and defines in which situations such authorities shall not release a product for free circulation or, in case of suspension, shall release the product. Moreover, Section 3 defines the measures to be taken by Market surveillance authorities if a product presents a serious risk or does not comply with the EU harmonisation legislation.

·Chapter V – EU Financing. Includes provisions on the financing system for obtaining the results expected by the Regulation. More specifically, it lists the activities eligible for financing and the arrangements on financial procedures. The Regulation also foresees the possibility of covering administrative expenses for all management and monitoring activities necessary for the achievement of its objectives.

·Chapter VI – Final provisions. The last two provisions subject to the evaluation are Article 38, which refers to the possibility of the adoption by the EC of non-binding guidelines on the Regulation implementation, and Article 41, which obliges the EU MS to lay down rules on penalties for economic operators applicable to infringements of the provisions of this Regulation.

2.1.3.Complementary nature of the market surveillance provisions

Some market surveillance rules are laid down in sector specific Union legislation. They set out in detail how and when a market surveillance authority should intervene when a non-compliant product is found. Market surveillance authorities should check the compliance of the product with the legal requirements applicable at the moment of the placing of the market or, if relevant, putting into service. The first level of control are usually documentary and visual checks, for example regarding the CE marking and its affixing, the availability of the EU declaration of conformity, the information accompanying the product and the correct choice of conformity assessment procedures. More profound checks may be however necessary to verify the conformity of the product, for example regarding the correct application of the conformity assessment procedure, the compliance with the applicable essential requirements, and the contents of the EU declaration of conformity.

The market surveillance provisions in the Regulation complement and strengthen existing provisions in Union harmonisation legislation providing more general principles for the organisation and tools for the implementation of control activities. The Regulation indicates that, in accordance with the principle of lex specialis, it should apply only in so far as there are no specific provisions with the same objective, nature or effect in other existing or future rules of Union harmonisation legislation. The corresponding provisions of the Regulation therefore do not apply in the areas covered by such specific provisions.

The Regulation does not affect the substantive rules of existing Union legislation setting out the rules and procedures to be observed by authorities and businesses when market surveillance is performed, but it should nonetheless enhance their operation.

The complementarity between the market surveillance provisions in the Regulation and those in Union harmonisation legislation has been remarkably improving over the last years through the alignment of sector-specific rules to those of Decision No 768/2008/EC, which was adopted together with the Regulation. The Decision includes reference provisions to be incorporated whenever product legislation is revised, working as a “template” for future product harmonisation legislation. The relation between the two sets of markets surveillance rules is illustrated in the following table. At the time of writing, several sector-specific directives and regulations were aligned with these reference provisions and further aligning proposals are pending.

|

Table 1: Market surveillance provisions in Regulation (EC) No 765/2008 and new sector legislation

|

|

MARKET SURVEILLANCE MEASURES AND STRUCTURES

|

REGULA-TION (EC) No 765/2008

|

NEW SECTOR LEGISLATION

|

|

MARKET SURVEILLANCE PROCEDURES

|

|

Obligations of economic operators vis-à-vis market surveillance authorities (information and cooperation)

|

No

|

Yes

|

|

Identification of economic operators (obligation for economic operators to identify the economic operators who supplied the product and the economic operator to whom the product was supplied)

|

No

|

Yes

|

|

Definition of formal non-compliance (e.g. markings wrongly or not affixed, declaration of conformity missing, technical documentation not available or incomplete etc.)

|

No

|

Yes

|

|

Procedures for dealing with non-compliant products (i.e. corrective actions, information obligations, restrictive measures, recalls etc.)

|

No

|

Yes

|

|

Market surveillance measures (i.e. role of market surveillance authorities)

|

Yes

|

No but legislation refers to Regulation (EC) No 765/2008

|

|

Products presenting a serious risk (i.e. Member States must ensure that products which present a serious risk requiring rapid intervention, are recalled, withdrawn or that their being made available on their market is prohibited)

|

|

|

|

Restrictive measures (i.e. procedural safeguards, statement of reasons, right to be heard, remedies etc.)

|

|

|

|

Exchange of information — Rapid Information System for products presenting a serious risk

|

|

|

|

General information support system (ICSMS) on issues relating to market surveillance activities, programmes and related information on non-compliance with Union harmonisation legislation, including identification of risks, results of testing carried out, provisional restrictive measures taken, contacts with the economic operators concerned and justification for action or inaction

|

|

|

|

Union safeguard procedure

|

No

|

Yes

|

|

Procedure for compliant products which present a risk to health and safety

|

No

|

Yes

|

|

MARKET SURVEILLANCE STRUCTURES

|

|

General requirements for market surveillance

|

Yes

|

No but legislation refers to Regulation (EC) No 765/2008

|

|

Information obligations about market surveillance authorities

|

|

|

|

Obligations of the Member States as regards organisation of market surveillance

|

|

|

|

Principles of cooperation between the Member States and the Commission

|

|

|

|

Sharing of resources

|

|

|

|

Cooperation with the competent authorities of third countries

|

|

|

|

Controls of products entering the Union market

|

|

|

|

Release of products

|

|

|

|

National measures on products entering the Union market

|

|

|

|

Financing provisions for market surveillance

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Penalties

|

Penalties for economic operators applicable to infringe-ments of the provisions of the Regulation

|

Penalties for economic operators applicable to infringements of the provisions of sector legislation

|

2.2.Consumer Safety and Market Surveillance Package (2013)

The Commission proposed in 2013 a major overhaul of the market surveillance framework for non-food products through a new single regulation on market surveillance. Its aim was to combine the market surveillance rules currently spread across the Union harmonisation legislation. All products would be subject to the same rules except where the specific characteristics of a category of products would state otherwise. Furthermore, procedures for the notification by Member States of information about products presenting a risk and corrective measures taken would be streamlined.

However, the negotiations between the European Parliament, the Council and the Commission have stalled for a long time. In its session of 26-27 May 2016, the 'Council took note of a request made by eleven member states to renew efforts with a view to moving forward negotiations on the Consumer Safety/Market Surveillance package (8985/16). The package is currently blocked in the Council because of a proposed provision on the introduction of a mandatory marking of origin on industrial products, known as the "Made in" provision (article 7 of the Consumer Safety draft regulation). In March, eleven member states in favour of maintaining the "Made in" provision, presented a compromise proposal based on the deletion of article 7 and the introduction of mandatory marking of origin in a limited amount of sectorial legislation, combined with a revision clause. The presidency verified that positions within the Council remain unchanged.' The discussions on this proposal were not resumed and it is reasonable to assume that any progress on this proposal in view of its adoption by the co-legislator is highly unlikely.

2.3.Baseline

2.3.1.Regulatory aspects

Before the Regulation, the framework for product controls to assure their conformity with EU rules was incomplete and inhomogeneous. This was based on:

·Regulation (EEC) No 339/93 that set up common procedures for controlling the products coming from non-EU countries but it did not contain an explicit obligation to carry out those controls;

·the General Product Safety Directive 2001/95/EC (hereinafter 'GPSD') that exclusively concerns controls of conformity of consumer products with safety requirements, i.e. only part of EU acquis and

·few scattered provisions embedded in sector-specific EU harmonisation legislation.

Being the responsibility (and a prerogative) of Member States, enforcement only had an ancillary role in EU harmonisation legislation until the adoption of the Regulation. The harmonisation legislation that existed in 2007 did not in general address market surveillance. Most instruments contain a very general clause obliging Member States to ensure that only products in compliance with the requirements of the directive are placed on the market. In the New Approach directives the safeguard clause procedure obliged national authorities to notify the Commission whenever they take a measure restricting the free circulation of a potentially dangerous product. The Commission had to issue an opinion on whether the measure is justified or not.

In respect of consumer goods, these general provisions in the sector directives were completed by the provisions of the General Product Safety Directive 2001/95/EC ('GPSD'). The GPSD has created a horizontal framework ensuring the safety of consumer products. To this end it sets out a number of obligations for manufacturers, importers and distributors as well as certain obligations for Member States as regards the organisation of market surveillance. The GPSD also established a network of authorities of the Member States competent for product safety aimed at facilitating operational collaboration on market surveillance and other enforcement activities. Moreover, the GPSD set up a European rapid alert system for dangerous non-food products for the rapid exchange of information requiring rapid intervention (RAPEX). It ensures information about dangerous products identified in the Member States is quickly circulated between the Member States and the Commission. The GPSD applies to the harmonised sectors like toys, cosmetics, etc., in so far as the relevant harmonisation directives have themselves not provided for specific rules.

However, the mechanisms established by the GPSD were not sufficient to ensure a coherent level of enforcement of Union harmonisation legislation throughout the EU. While harmonisation legislation covers both consumer and non-consumer products, the GPSD focuses on consumer protection. Therefore, its mechanisms are not applicable to whole range of products covered by Union harmonisation legislation. Hence RAPEX did not allow for exchange of information on dangerous industrial products like machinery or lifts, which present a risk for workers or users. Furthermore only health and safety aspects were covered by this system, and environmental risks were not taken into consideration.

While the GPSD contains an obligation for Member States to take part in the cooperation mechanism, the obligations it imposes on Member States to organise and perform market surveillance are rather general. For this reason differences in the various Member States still continued to persist, leading to a different level of protection and enforcement within the EU.

2.3.2.Level of non-compliance in 2008

According to the impact assessment of 2008, the share of non-compliant products could only be crudely estimated and the situation differed very much from sector to sector and from Member State to Member State. Nevertheless, the available information indicated that a significant proportion of the products on the market do not comply with the legal requirements. In 2004, for example, 33% of industrial products were found not to be in conformity with the legislation in Germany. The following table summarises the findings.

|

Table 2: Indications from stakeholders on the share of non-compliant products on the market in 2008.

|

|

Source

|

Share of non-compliant products on the market

|

|

SME Test panel

|

The majority of SMEs could not provide figures. Where figures were given, they differed considerably from sector to sector as well as between Member States. The figures ranged from 4%-51%, the average being 24%.

|

|

Enterprise questionnaire

|

Most respondents could not provide figures but indicated that the problem was important. However, below is an overview of the estimates provided:

Electro-technical sector: 10-30% (up to 50 % in the luminaires sector)

Mechanical sector: 5-7 %

Medical devices: 10-30%

Construction products: 10-30%

|

|

Market surveillance authorities

|

Electro-technical 10-70 %

Medical Devices 2-20 %,

Construction products 2-30 %

Recreational Craft 1 %

|

There are some indications in ICSMS, although the system was only used by a smaller group of Member States:

|

Table 3: Indications from stakeholders on the share of non-compliant products on the market.

|

|

Year

|

0 - No defects identified

|

1 - Low risk

|

2 - Medium risk

|

3 - High risk

|

4 - Serious risk

|

|

2008

|

574

|

1.034

|

1.153

|

927

|

0

|

|

2009

|

476

|

1.094

|

1.069

|

888

|

0

|

The following box presents eighteen evaluation questions, framed within the five evaluation criteria that have been answered to assess the market surveillance provisions of the Regulation.

|

Effectiveness

EQ1.Are the results in line with what is foreseen in the impact assessment for the Regulation, notably as to the specific objectives of (i) enhanced cooperation among Member States/within Member States, (ii) uniform and sufficiently rigorous level of market surveillance, (iii) border controls of imported products?

EQ2.Are there specific forms of the implementation of the Regulation at Member State level that render certain aspects of the Regulation more or less effective than others, and – if there are – what lessons can be drawn from this?

EQ3.To what extent has the different implementation (i.e. discrepancies in the implementation) of the initiative in Member States impacted on the effectiveness of the measures on the objective?

EQ4.How effective was the measure as a mechanism and means to achieve a high level of protection of public interests, such as health and safety in general, health and safety at workplace, the protection of consumers, protection of the environment and security? What have been the quantitative and qualitative effects of the measure on its objectives?

EQ5.How effective was the measure as a mechanism and means to achieve a level playing field among businesses trading in goods subject to EU harmonisation legislation? What have been the quantitative and qualitative effects of the measure on its objectives?

Efficiency

EQ6.What are the regulatory (including administrative) costs for the different stakeholders (businesses, consumers/users, national authorities, Commission)?

EQ7.What are the main benefits for stakeholders and civil society that derive from the Regulation?

EQ8.To what extent have the market surveillance provisions been cost effective?

EQ9.Are there any significant differences in costs (or benefits) between Member States? If so, what is causing them?

Relevance

EQ10.To what extent are market surveillance provisions of the Regulation still relevant in light of for instance of increasing online trade, the increase in imports from third countries, shortening product life, increasing budgetary constraints at national level, etc.?

EQ11.To what extent do the effects of the market surveillance provisions satisfy (or not) stakeholders' needs? How much does the degree of satisfaction differ according to the different stakeholder groups?

EQ12.Is there an issue on the scope (i.e. all EU product harmonisation legislation) of the measure or some of its provisions?

EQ13.Is the concept of lex specialis still a suitable interface between the market surveillance provisions in the Regulation and those in other (notably sector) legislation?

Coherence

EQ14.To what extent are the market surveillance provisions coherent internally?

EQ15.To what extent are the market surveillance provisions above still coherent with other Union legislation on market surveillance on non-food products?

EQ16.To what extent are these provisions coherent with wider EU policy?

EU added value

EQ17.What is the additional value resulting from the market surveillance provisions at EU level, compared to what could be achieved by Member States at national and/or regional levels?

EQ18.To what extent do these provisions support and usefully supplement market surveillance policies pursued by the Member States? Do the provisions allow some sort of 'control' by the EU on the way national authorities carry out market surveillance?

|

4.1.Sources

This evaluation builds partly on an external study carried out by a consultant. The methodology of the study consisted of desk research, field research and case studies. The results of the study and its methodology are set out in Annex 4 which builds on, and analysed Annexes 1 to 3 and 5 to 9.

In addition, this evaluation uses the market surveillance programmes of Member States, the results of the review and the assessment set out in Annex 7, the first report on the implementation of the Regulation, and other documents set out in the Annex of this evaluation, including the evaluation of Union harmonisation legislation.

Yet, it is important to keep in mind the complementary nature of the market surveillance provisions and the fact that Union harmonisation legislation has evolved fundamentally, especially with regard to market surveillance. As mentioned in section 2.1.3 Regulation (EC) No 765/2008 and Decision 768/2008/EC were the starting point for the introduction of specific market surveillance procedures in Union harmonisation legislation. Since their adoption, almost twenty directives and regulations with market surveillance procedures were adopted by the European Parliament and the Council and referring directly to the market surveillance provisions.

Therefore, it is quite difficult to separate the effectiveness, the efficiency, the relevance and the EU added value of, on the one hand, the market surveillance provisions in the Regulation and, on the other, the market surveillance procedures in these directives and regulations. Nonetheless, this evaluation focuses specifically on the market surveillance provisions in the Regulation and will separate them from any other elements set out in other legal instruments. Their coherence will be examined in the section on coherence.

4.2.Limitations – robustness of findings

The baseline data are quite limited and are hardly comparable with the current data. In addition, Union harmonisation legislation was amended for several products since 2008, which may have an impact on the findings on formal non-compliance since this type of non-compliance was less prominent in the previous legislation. Formal non-compliance also includes, for example, missing warnings and information for consumers on the packaging. Therefore, it could also lead to safety problems.

There were some significant data gaps, especially as regards availability, reliability and structure. Triangulation was used wherever possible. In particular:

(1) Significant gaps in data availability make it difficult to provide a complete picture of the dimension of product non-compliance across the EU. In light of this constraint, it is difficult to draw robust conclusions on the effectiveness of the Regulation in reducing product non-compliance with respect to the years prior to its entry into force. In order to have at least a partial overview of the issue, two solutions have been implemented:

·RAPEX notifications were used as a proxy for measuring product non-compliance, although they only relate to products that pose (serious or “other”) risks to the health of consumers/users and thus represent an underestimation of the real dimension of non-compliance,

·some indicators provided in national reports (number of product-related accidents/user complaints, corrective actions taken by economic operators, inspections resulting in findings of non-compliance, inspections resulting in restrictive measures taken by MSAs) were also be used as proxies for product non-compliance, where information was available.

(2) The analysis of the implementation and the cost-benefits analysis encountered main difficulties due to the differing levels of detail in the information provided by Member States' authorities, as to market surveillance activities carried out and available resources. Information was only partially or not available at all for a large number of countries.

Finally all the steps presented for the market analysis were subject to the following issues: (i) Definitions of sectors/products in the regulation are usually different from nomenclatures used within statistics; (iii) Statistics at the sectorial/product level use different nomenclatures (e.g. intra EU trade uses the Standard International Trade Classification [SITC], production values use the PRODuction COMmunautaire [PRODCOM] nomenclature, business demographics uses the Statistical Classification of Economic Activities in the European Community [NACE]); (iii) Difficulties in identifying harmonised sectors in case EU legislation introduced harmonised rules that apply only to some products within sectors. As a result, the outcomes of this analysis are to be regarded as indicative estimates.

|

5.Implementation state of play (Results)

|

5.1.Market surveillance structures and measures

According to Article 16(1) of the Regulation, “Member States shall organise and carry out market surveillance as provided for in this Chapter [i.e. on General requirements]”. The Regulation does not set out explicit obligations as to how market surveillance shall be organised at the national level, this being left to Member States’ prerogative. Therefore, market surveillance is organised differently at the national level in terms of the sharing of competences and powers between Market surveillance authorities. In this regard, three types of overall organisation models have been implemented by Member States, although with a number of additional country-specific nuances:

–Centralised, where activities are carried out by one or few Market surveillance authorities. This model is applied in Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Luxembourg, Malta, Portugal, and Slovakia.

–Decentralised at the sectoral level, where several Market surveillance authorities operate and have different competences, depending on the sector where they perform market surveillance activities. This model is adopted in Belgium, Cyprus, Croatia, Denmark, Estonia, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the Netherlands, Romania, Slovenia and Sweden.

–Decentralised at the regional/local level, where numerous Market surveillance authorities have enforcement responsibilities on specific geographical areas of competence. Austria, Finland, Germany, Hungary, Spain and the United Kingdom follow this organisational structure.

The following boxes provide an overview of the organisation models implemented respectively by Italy and Germany.

Box 1: The Italian organisational model of market surveillance

The Italian model of market surveillance is decentralised at the sectoral level. The Ministry of Economic Development (MISE) is the main national MSA and acts as a coordination body for the different enforcement authorities conducting market surveillance in the field, for relations and negotiations at the EU level, for the use of Rapid Exchange of Information System (RAPEX) and Information and Communication System for Market Surveillance (ICSMS), and for the establishment of ad hoc budgets and objectives. The MISE has general responsibilities over all sectors covered by Regulation 765/2008. Different ministries are in charge of market surveillance in various sectors within the scope of the Regulation. For instance, the Ministry of the Interior is responsible for market surveillance of explosives, while chemicals fall under the responsibility of the Ministry of Health. The Ministry of Infrastructure and Transportation controls the largest number of product categories. Each ministry organises its own market surveillance enforcement system.

Other relevant enforcement bodies are:

·The Institute for Environmental Protection and Research – ISPRA, under the Ministry of the Environment, which is in charge of enforcing Regulation 765/2008 regarding noise emissions for outdoor equipment.

·The Italian Economic and Financial Police – Guardia di Finanza (GdF), under the Ministry of Economy and Finance. Market surveillance activities are undertaken by the Special Unit for the Protection of Markets which exercises its powers on toys, personal protective equipment, low-voltage electronics and electromagnetic compatibility. The Guardia di Finanza operates autonomously within the territory or in collaboration with the Customs Authority. It can also file RAPEX notifications.

·The Chamber of Commerce, coordinated by Unioncamere that report to the Ministry of Economic Development. Their activities are based on annual bilateral agreements, establishing the number and the sectors of the planned inspections. Inspected sectors vary from year to year and can include toys, textile and footwear labelling, as well as electrical equipment.

·The Local Health Units (Azienda Sanitaria Locale, ASL), under the Ministry of Health. They carry out health and safety inspections in the workplace. Although their core mission is not primarily related to market surveillance, they can sometimes find evidence of non-compliance in plants, machinery, medical devices or personal protective equipment during their inspections.

·The special unit of the Italian Police Carabinieri, NAS. It is a law enforcement body under the Ministry of Health, focused on health and safety controls covering several product categories. In particular, this unit of the Carabinieri monitors activities under the General Product Safety Directives (GPSD), toys, medical devices, plant protection products, as well as health products – all within the scope of the Regulation 765/2008.

The National Customs Authority is responsible for product checks at the border and it is mainly active near airports and harbours through its local offices.

The analysis of the Italian system has identified certain strengths and weaknesses of this model of organisation. First of all, while it is organised in a pyramidal way, with the MISE as the main body responsible for national market surveillance and in charge of coordination. Overall, however, it seems that there are no formal channels or established standard procedures through which the different ministries can coordinate their activities. As a consequence, although the MISE may have the formal powers over MSAs’ activities, in practice it has no power of control over their budgets and therefore on priority setting. Indeed, it seems that market surveillance, in the context of Regulation 765/2008, is just one of the many tasks that each enforcement body has to deal with on a daily basis. Second, sectoral decentralisation has led to different product sectors being under the responsibility of the most appropriate ministry or institution, thus providing a higher level of specific knowledge. However, this adds complexity to the management and uniformity of market surveillance at the national level. In particular, the fact that every ministry internally organises its own market surveillance structure for each product category leads to variation in the ways the different sectors are controlled and managed. Moreover, fragmentation throughout the territory may hinder authorities’ response times. In this context, an overlap of competences may also happen. A critical operational issue is the integration of Regulation 765/2008 with other sectoral legislation, given that the primary responsibility for the enforcement of the Regulation is under the MISE, while the enforcement of some sectoral laws is under the responsibility of the relevant ministries. Moreover, some sectors can be controlled by multiple authorities, as in the case of GPSD. Therefore, there may be cases where products need multiple evaluations and validations in order to be allowed to enter the market.

Box 2: The German organisational model of market surveillance

Germany is characterised by a structure decentralised at the regional/local level, where competences are shared among various Land authorities. Germany is a Federal Republic made up of 16 Länder whose ministries are separate from the Federal Government, both from a policy and financial point of view. The Federal Government and Federal Ministries are responsible for the overall legislation (laws and regulations), while the 16 Länder are in charge of the enforcement of this legislation. Resources for market surveillance are therefore provided by the Länder themselves.

The 16 Länder coordinate their enforcement action through several committees, where representatives from the Land ministries and MSAs regularly meet. Committees are focused on selected sectors. The biggest committee is the Working Committee on Market Surveillance – AAMÜ, which covers the largest number of sectors within the scope of Regulation 765/2008. Another coordination body is the Central Authority of the Länder for Technical Safety (ZLS). The ZLS was set up to centralise some market surveillance tasks, such as the creation of product risk profiles and the forwarding of RAPEX notifications, instead of having them repeated for all of the 16 Länder. The ZLS has more operational tasks than the other coordination committees and can even enforce the law under special conditions and following the Länder’s requests (for instance, when a market surveillance case involves several Länder or has international relevance). Another pillar of the German coordination strategy is represented by the extensive use of ICSMS, which national authorities are very familiar with, as it was first developed in Germany. As already mentioned, ICSMS is crucial to avoiding duplication of work, a possible deficiency of decentralised structures.

At the central level, three Federal MSAs enforce market surveillance in specific product sectors:

·The Federal Network Agency – BNetzA, under the Federal Ministry of Economy and Energy, is responsible for market surveillance in two sectors: electrical equipment under the Electro-Magnetic Compatibility Directive and radio and telecommunications equipment under the Radio and Telecommunication Terminal Equipment Directive;

·The Federal Authority for Maritime Equipment and Hydrography – BSH, under the Federal Ministry of Transport and Digital Infrastructure, is responsible for the marine equipment sector;

·The Federal Motor Transport Authority – KBA, under the Federal Ministry of Transport and Digital Infrastructure, is responsible for motor vehicles.

Three additional Federal agencies are also involved in the context of market surveillance, though they are not responsible for enforcement in individual product sectors, the Federal Institute for Occupational Safety and Health – BAuA, the Federal Institute for Materials Research and Testing – BAM, and the Federal Agency for Environment – UBA.

The Central Customs Authority (Generalzolldirektion) is responsible for many fields other than those related to the Regulation (e.g. drugs, weapons, human health, and environment). It also coordinates, manages and supervises the 270 local Customs offices, which are in charge of border controls.

The analysis of the German system has identified certain strengths and weaknesses of this model of organisation. A clear strength of the system is that the German organisational structure establishes a responsible authority for each product sector where tasks are well defined and competences clearly split. Therefore no overlapping occurs between the Federal and the Land level in terms of market surveillance responsibilities in all sectors covered by the Regulation. Nonetheless, substantial resources are required to replicate a market surveillance system in 16 Länder. Furthermore, particularly in the case of Customs, the high number of organisational entities involved in the organisation of market surveillance makes difficult to identify the ‘right partner’ to deal with market surveillance issues. Even more importantly this organisational model has required many efforts to ensure the necessary level of coordination (e.g. the establishment of permanent, ad hoc coordination bodies such as the ZLS, the organisation of workshops, meetings and events to create an ‘informal’ network of market surveillance actors). The efficiency of the several coordination tools seems also to be an issue. Germany is indeed planning to create a single, general coordination board covering all product categories and ensuring further alignment between the Federal, the Land and the European level that would rationalise the existing coordination mechanisms.

Section 5.2 of Annex 4 and section 2 of Annex 7 provide a detailed country-by-country overview of the current situation in terms of structures relevant to the implementation of the market surveillance provisions with regards to the organisation of market surveillance at the national level, the market surveillance activities to detect non-compliant products, the existing coordination and cooperation mechanisms within/among Member States, and the measures taken against non-compliant products.

Figure 2: The Italian organisational model of market surveillance

Figure 3: The German organisational model of market surveillance

5.2.Additional information

5.2.1.Exchange of information (ICSMS, notifications of restrictive measures, national market surveillance programmes and reports on activities)

The market surveillance provisions in the Regulation foresee instruments for the exchange of information between Member States

. They include RAPEX

and ICSMS

as key tools for the cross-border exchange of information and work sharing between market surveillance authorities.

While RAPEX is successfully used for dangerous consumer products posing a risk to the health and safety in the context of the GPSD, it is much less used for the other serious risks covered by Article 20 of Regulation (EC) No 765/2008:

|

Table 4: RAPEX notifications under Regulation (EC) No 765/2008

|

|

Year

|

Professional Products

|

Electromagnetic disturbance

|

Incorrect measurement

|

Environmental risk

|

|

2012

|

31

|

0

|

0

|

4

|

|

2013

|

53

|

8

|

1

|

63

|

|

2014

|

32

|

1

|

0

|

32

|

|

2015

|

24

|

1

|

0

|

35

|

|

2016

|

47

|

0

|

0

|

41

|

|

Total

|

187

|

10

|

1

|

175

|

Almost all Member States now use ICSMS, after a slow take-up. More than 7,000 products are encoded in the system every year. In 2015 the database contained information on around 70,000 products and more than 250,000 files stored (i.e.: test lab reports, declarations of conformity, pictures, etc.). However, Member States use the system to different degrees, as illustrated in the diagram below which shows the numbers of product information put into the ICSMS system during 2016. Clearly the system is not used very well by many market surveillance authorities and some are not using the system at all. Even within Member States, such as the UK and Germany, there is a great variation between different market surveillance authorities on their use of the system.

Figure 4: Use of ICSMS by all EU/EEA Member States in 2016 :

Figure 5: Use of ICSMS by EU/EEA Member States excluding Germany in 2016:

In addition to this, it is worth mentioning that sector specific Union legislation also sets out an obligation for Member States' competent authorities to communicate to the other Member States restrictive measures taken against non-compliant products. This procedure is often referred to as the 'safeguard clause procedure'. Furthermore, receiving Member States then have an obligation to 'follow up' on those notifications, i.e. adopt in turn appropriate measures in respect of their national territory. In many cases they also have the possibility to object to the measures notified and in this case the Commission will assess whether it was justified

. Recent guidance discussed at expert's working group level clarifies principles for cooperation based on the existing legal framework and the link between these obligations and the use of the RAPEX and ICSMS tools

. However, with the exception of few sectors (notably low voltage equipment) only few notifications of restrictive measures are actually officially sent by national market surveillance authorities. Furthermore, even in these 'best case scenarios' sectors many Member States do not actually notify any measures and the number of notifications is decreasing overtime.

The market surveillance provisions in the Regulation require Member States to draw market surveillance programmes and to periodically review and assess the functioning of their activities at least every four years (Articles 18(5) and 18(6)). All Member States communicated market surveillance national programmes and reports to review and assessed the functioning of market surveillance activities during the first four years of application of the Regulation. However, since the Regulation does not provide any details on the content of the programmes and reports, the sectorial coverage and the quality of information contained in this documentation varies remarkably from Member States to Member State. Comparability of information is also an issue.

5.2.2.Cooperation

Since 2013, on the basis of the Regulation financing provisions, the European Commission provides logistical and financial support for informal cooperation between national authorities that takes place by means of the so-called Administrative Cooperation groups (hereinafter 'AdCos')

in a number of sectors. AdCos participants discuss several issues related to the market surveillance, elaborate common guidance documents and sometimes carry out joint enforcement actions. According to the feedback received from AdCos this support has proven beneficial in increasing and stabilising the rate of participation of national authorities in the meetings.

|

Table 5: Participation in AdCo meetings

|

|

AdCo

|

2014

|

2015

|

2016 (1st semester)

|

|

|

Partici-pants

|

Represented countries

|

Partici-pants

|

Represented countries

|

Partici-pants

|

Represented countries

|

|

|

|

MSs

|

Other

|

Total

|

|

MSs

|

Other

|

Total

|

|

MSs

|

Other

|

Total

|

|

ATEX

|

35

|

15

|

3

|

18

|

33

|

17

|

3

|

20

|

33

|

21

|

2

|

23

|

|

|

33

|

17

|

3

|

20

|

33

|

17

|

2

|

19

|

33

|

14

|

2

|

16

|

|

CABLE

|

23

|

12

|

3

|

15

|

21

|

10

|

2

|

12

|

26

|

12

|

3

|

15

|

|

CIVEX

|

no data for 2014

|

30

|

20

|

1

|

21

|

October/November

|

|

COEN

|

no data for 2014

|

no data for 2015

|

no data for 2016

|

|

CPR

|

31

|

20

|

2

|

22

|

43

|

21

|

4

|

25

|

36

|

15

|

4

|

19

|

|

|

46

|

23

|

3

|

26

|

44

|

25

|

2

|

27

|

|

|

|

|

|

EMC

|

38

|

20

|

4

|

24

|

37

|

21

|

5

|

26

|

40

|

18

|

4

|

27

|

|

|

36

|

19

|

4

|

23

|

34

|

22

|

4

|

26

|

|

|

|

|

|

ENERLAB / ECOD

|

no data for 2014

|

32

|

22

|

1

|

23

|

43

|

21

|

1

|

22

|

|

|

|

34

|

18

|

3

|

21

|

|

|

|

|

|

GAD

|

18

|

14

|

0

|

14

|

15

|

8

|

2

|

10

|

19

|

12

|

2

|

14

|

|

|

14

|

11

|

0

|

11

|

16

|

11

|

2

|

13

|

|

|

|

|

|

LIFT

|

25

|

12

|

3

|

15

|

24

|

14

|

3

|

17

|

25

|

17

|

2

|

19

|

|

|

21

|

14

|

2

|

16

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LVD

|

31

|

15

|

4

|

19

|

32

|

20

|

4

|

24

|

36

|

17

|

4

|

21

|

|

|

33

|

19

|

3

|

22

|

34

|

22

|

3

|

25

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

31

|

18

|

4

|

22

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

MACHINE

|

32

|

17

|

3

|

20

|

33

|

20

|

3

|

23

|

38

|

20

|

4

|

24

|

|

|

33

|

15

|

3

|

18

|

30

|

19

|

3

|

22

|

|

|

|

|

|

NOISE

|

22

|

10

|

2

|

12

|

23

|

9

|

2

|

11

|

Meeting October 2016

|

|

PED/SVPD

|

22

|

13

|

3

|

16

|

25

|

15

|

4

|

19

|

24

|

15

|

4

|

19

|

|

|

25

|

18

|

3

|

21

|

15

|

11

|

1

|

12

|

|

|

|

|

|

PPE

|

44

|

21

|

4

|

25

|

39

|

19

|

4

|

23

|

39

|

20

|

5

|

25

|

|

|

37

|

19

|

4

|

23

|

40

|

21

|

4

|

25

|

|

|

|

|

|

PYROTEC

|

30

|

14

|

0

|

14

|

34

|

17

|

0

|

17

|

32

|

19

|

1

|

20

|

|

|

30

|

15

|

0

|

15

|

34

|

19

|

0

|

19

|

|

|

|

|

|

RCD

|

35

|

17

|

2

|

19

|

22

|

15

|

2

|

17

|

31

|

19

|

2

|

21

|

|

|

33

|

16

|

3

|

19

|

30

|

19

|

1

|

20

|

|

|

|

|

|

RED

|

23

|

12

|

2

|

14

|

41

|

25

|

4

|

28

|

41

|

23

|

2

|

25

|

|

|

40

|

24

|

2

|

26

|

41

|

22

|

4

|

26

|

40

|

25

|

2

|

27

|

|

|

39

|

19

|

4

|

23

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

44

|

22

|

3

|

25

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TOYS

|

no data for 2014

|

37

|

18

|

5

|

23

|

32

|

15

|

4

|

19

|

|

|

|

40

|

25

|

3

|

28

|

|

|

|

|

|

TPED

|

12

|

9

|

0

|

9

|

23

|

12

|

1

|

13

|

21

|

8

|

3

|

11

|

|

|

13

|

5

|

1

|

6

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

WELMEC

|

no data for 2014

|

31

|

21

|

1

|

22

|

33

|

19

|

4

|

23

|

|

|

|

36

|

19

|

4

|

23

|

|

|

|

|

As regards the development of common market surveillance projects, the following table summarises the joint actions carried out or launched within different AdCos during the 2013-2016 period and number of countries participating in the action:

|

Table 6: Joint actions organised within AdCos and number of Member States (MS) participating

|

|

AdCo

|

2013

|

2014

|

2015

|

2016

|

|

ATEX

|

|

|

|

|

|

CABLE

|

|

|

|

|

|

CIVEX

|

|

|

|

|

|

COEN

|

|

|

Information and instructions on reprocessable products (12 MS)

|

Clinical data (7-8)

Harmonising inspections (7-8 MS)

|

|

CPR

|

2012-2013: EPS (10 MS)

|

Smoke alarms (10 MS)

|

Windows (7 MS)

|

|

|

ECOD / ENERLAB / ROHS

|

ECOD: Lighting and chain lighting (10 MS)

ROHS: Toys (8 MS) and Kitchen appliances (10 MS)

|

ROHS: Cheap products (10 MS)

|

ROHS: Cables/USB/others (6 MS)

|

ECOD: Defeat devices (4 MS)

ENERLAB: Collecting inspection data methodologies (6 MS)

|

|

EMC

|

Switching power supplies (19 MS)

|

Solar inverters (14 MS)

|

|

|

|

GAD

|

|

|

|

Gas appliances (8 MS)

|

|

LIFT

|

|

|

|

|

|

LVD

|

|

|

LED

Floodlights* (13 MS)

|

|

|

MACHINE

|

2012-2013: Log Splitters (about 8 MS)

2012-2015: Firewood Processors (about 7-8 MS)

(1) 2011-2015: Impact Post Drivers (3-4 MS)

|

Boom saws (3 MS)

|

|

Portable chain-saws and vehicle servicing lifts* (9-10 MS)

|

|

NOISE

|

|

|

|

|

|

PED

|

|

Air receivers for compressors (2 MS)

|

|

|

|

PPE

|

|

|

|

|

|

PYROTEC

|

|

|

|

|

|

REACH

|

1 big action/year involving all Member States. Additional pilot actions on a smaller scale

|

|

RED

|

|

Mobile phone repeaters (14 MS)

|

Drones (18 MS)

|

|

|

RCD

|

|

|

Small inflatable crafts (6 MS)

|

|

|

TOYS

|

|

|

|

|

|

TPED

|

|

|

|

|

|

WELMEC WG5

|

|

Electric energy meters* (11)

|

Heat meters* (10)

|

|

* project co-financed by the European Commission.

Some joint market surveillance campaigns were financed by the European Commission on the basis of financing provisions included in the market surveillance provisions. In particular, the following calls for proposals were issued since 2013:

·In 2013 the Commission launched the first call for proposals for joint enforcement actions under the multi-annual plan for market surveillance of products in the EU. The grant was awarded to a project focussed specifically on active electrical energy meters and heat meters. The grant took the form of a 70% reimbursement by the Commission of the eligible costs of the action (amount approximately allocated 350 000 EUR) and was fully managed by Member States. The action was carried out by a consortium of authorities under the coordination of a Spanish authority.

·In 2014 a new call for proposals for joint enforcement actions was launched and led to funding by the Commission of two proposed actions respectively in the field of machinery safety and LED floodlights. The grants that have been awarded are in the form of an 80% reimbursement by the Commission of the eligible costs of the actions (total amount allocated is approximately 1000 000 EUR). One of the actions was coordinated by a Finnish authority, while the other was coordinated by the "Prosafe" foundation

.

·In July 2015 a call for proposals was launched with a maximum budget foreseen for EU financing of 500 000 EUR. One proposal was received by the deadline of 1 October 2015 but did not lead to the award of any grant since the proposal received did not address the objectives as stipulated in the call.

·In March 2016 two calls for proposals were launched with a higher maximum budget foreseen for EU financing of 750 000 EUR and 540 000 EUR respectively, but no proposals were received.

5.2.3.Infringement proceedings

The Commission did not launch any infringement proceedings related to the market surveillance provisions. There have been two complaints from economic operators but both cases were closed in the absence of a clear breach of the Regulation.

It is unclear whether the limited number of complaints is due, either to the clarity of the provisions, or to the fact that the market surveillance provisions are not very known with businesses. The fact that these provisions only set minimum requirements for market surveillance leaving Member States with high discretion in their implementation, and the relative uncertainty on the precise scope of the Regulation may also have had an impact.

Furthermore, there were no judgements from the Court of Justice about the provisions.

|

6.Answers to the evaluation questions

|

6.1.Effectiveness

EQ1 -

Are the results in line with what is foreseen in the impact assessment for the Regulation, notably with regards to the specific objectives of (i) enhanced cooperation among Member States, (ii) uniform and sufficiently rigorous level of market surveillance, (iii) border controls of imported products?

6.1.1.Enhanced cooperation among Member States

The impact assessment for the Regulation foresaw that cooperation and information exchanged would be considerably improved under the preferred option. The market surveillance provisions have indeed improved substantially the cooperation between Member States which nevertheless often remains difficult due to the high degree of fragmentation in market surveillance competences and the slow take up of the different tools to share information and coordinate enforcement work

.

6.1.1.1.Exchange of information (ICSMS, notifications of restrictive measures, national market surveillance programmes and reports on activities)

Statistics presented in section 5 and information gathered from stakeholders show that the use of ICSMS by Market surveillance authorities is still limited, or that some Member States do not even use ICSMS at all. Even within Member States there is a great variation between Market surveillance authorities in their use of the system. This hampers the possibility of capitalising the work carried out by other authorities and creates a duplication of effort, which is the case when the system is properly used, as shown by the German practice analysed in case study 2. Also, the possibility for Market surveillance authorities and Customs to make use of test reports drafted by Market surveillance authorities in other EU countries seems to be limited. On the other hand a number of Market surveillance authorities pointed out the burden due to the filling-in of both ICSMS and internal/national databases because of compatibility issues.. Further frequent issues concern the lack of adaptations to insert sector-specific information into ICSMS and there being no opportunity to update information along the progress of the case. The low user-friendliness to ease data entry, difficulties in finding instructions on how to use ICSMS and linguistic barriers are also reported as minor issues that could be improved.

As for RAPEX, its use has significantly increased over the years, both in terms of the number of notifications and follow-up actions. Moreover, the number of follow-ups outweighed the number of total notifications from 2014, this possibly indicating that RAPEX is more and more recognised and used as an information tool for enforcing market surveillance. However, the use of RAPEX across Member States differs, indicating that some Member States are more proactive while others are more reactive in dealing with notifications. Yet, there are doubts on the full use of RAPEX considering that the number of notifications made in the system is not proportionate to the size of the national markets. For instance, Cyprus notifies on average more than Poland, Sweden and Romania. An obstacle to the use of RAPEX is the perceived redundancy of having different notification procedures and communication tools: some market surveillance authorities think that ICSMS, RAPEX and the safeguard clause should be integrated within a single information system to avoid double encoding of information and inconsistencies. On the other hand, as mentioned in section 5 the safeguard clause procedure set out in sector specific Union legislation appears largely underexploited by Member States.

The market surveillance programmes are considered potentially very useful by stakeholders because they are an opportunity to define market surveillance strategies and to inform consumers. The programmes are also useful to avoid overlapping of market surveillance actions, working as a tool for cooperation between market surveillance authorities. They can even contribute to ensuring a level playing field in Europe, since they allow Member States to acknowledge the differences in the enforcement actions and possibly to eliminate them. The national 'review and assessment' reports can importantly contribute to improving the effectiveness and efficiency of market surveillance activities since they help in verifying and monitoring implemented activities.

However, the requirements of the provision on these programmes and reports are rather general, and this has led to the development of different practices in the preparation of these documents and hindered the provision of relevant information. Several efforts were made at experts' level to build common templates and procedures to capitalise the tools, which led to increasing uniformity in the content of the programmes. Nevertheless, information contained therein is often too generic to serve as a planning tool. Furthermore, many programmes are shared by Member States too late (i.e. months after the start of the period they refer to) to be able to learn from each other’s experience and enhancing collaboration

. As regards national reports, important information gaps and issues of comparability of data limit the possibility to have a complete overview of market surveillance activities in the internal market.

6.1.1.2.Cooperation

The sub-optimal use of information systems to exchange information hampers also cooperation between Member States - that is mainly based on the use of those systems and on European-level initiatives (namely ability to respond and/or complement each other enforcement action, cooperation through AdCos, and joint actions).

Besides the sub-optimal use of information systems, cooperation between Member States faces additional challenges. Even if the majority (77%) of Market surveillance authorities and Customs consulted state that they cooperate with authorities based in other Member States and the large majority of Market surveillance authorities declare that they notify other Member States (75%), most of the Market surveillance authorities (78%) rarely restrict the marketing of a product following the exchange of information on measures adopted by another EU MSA against the same product.

The respondents to the Public Consultation indicate that market surveillance authorities rarely restrict the marketing of a product following the exchange of information about measures adopted by another market surveillance authority in the EU against the same product. This occurs “sometimes” according to 34% of stakeholders and "never " according to 8% of respondents, while a minority declare that it occurs “very often” (12%) or “always” (6%). Cross-border cooperation remains problematic, according to the respondents

.

According to informal feedback from national experts, requests for mutual assistance among authorities in different Member States to supply each other with information or documentation and to carry out appropriate investigations are made and followed up only occasionally.

Furthermore, a closer look at ICSMS shows that, more than 80% of the cases transferred from one market surveillance authority to another ('baton passing') through the system are done within the same country. In addition, many of the cases that one market surveillance authority wishes to transfer to its colleagues in another Member State are rejected. The main reason for many rejections is that the 'target authority' considers itself as geographically or materially not competent to handle the case; a lack of resources was also frequently argued.

Figure 6: Baton passing in ICSMS among Member States (status December 2016):

Figure 7: Rejections of baton passing in ICSMS (December 2016):

Figure 8: Baton passing initiated in ICSMS (December 2016):

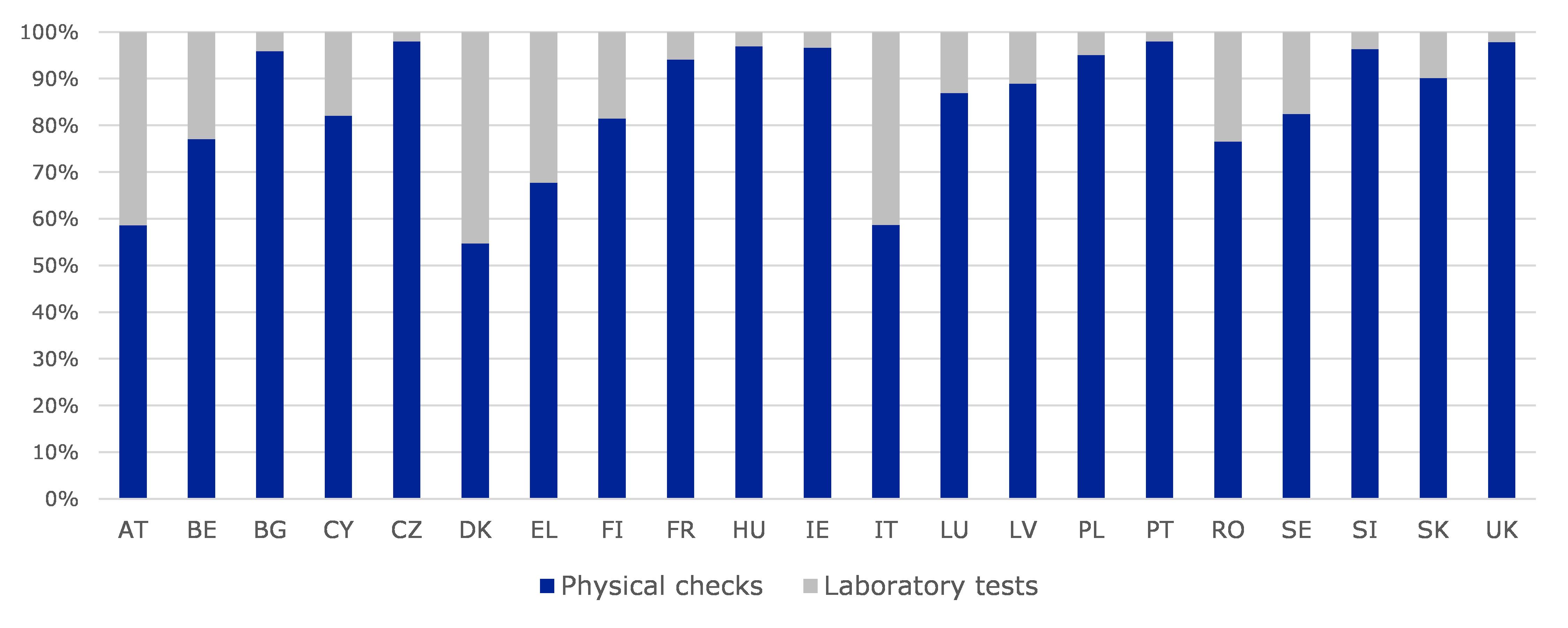

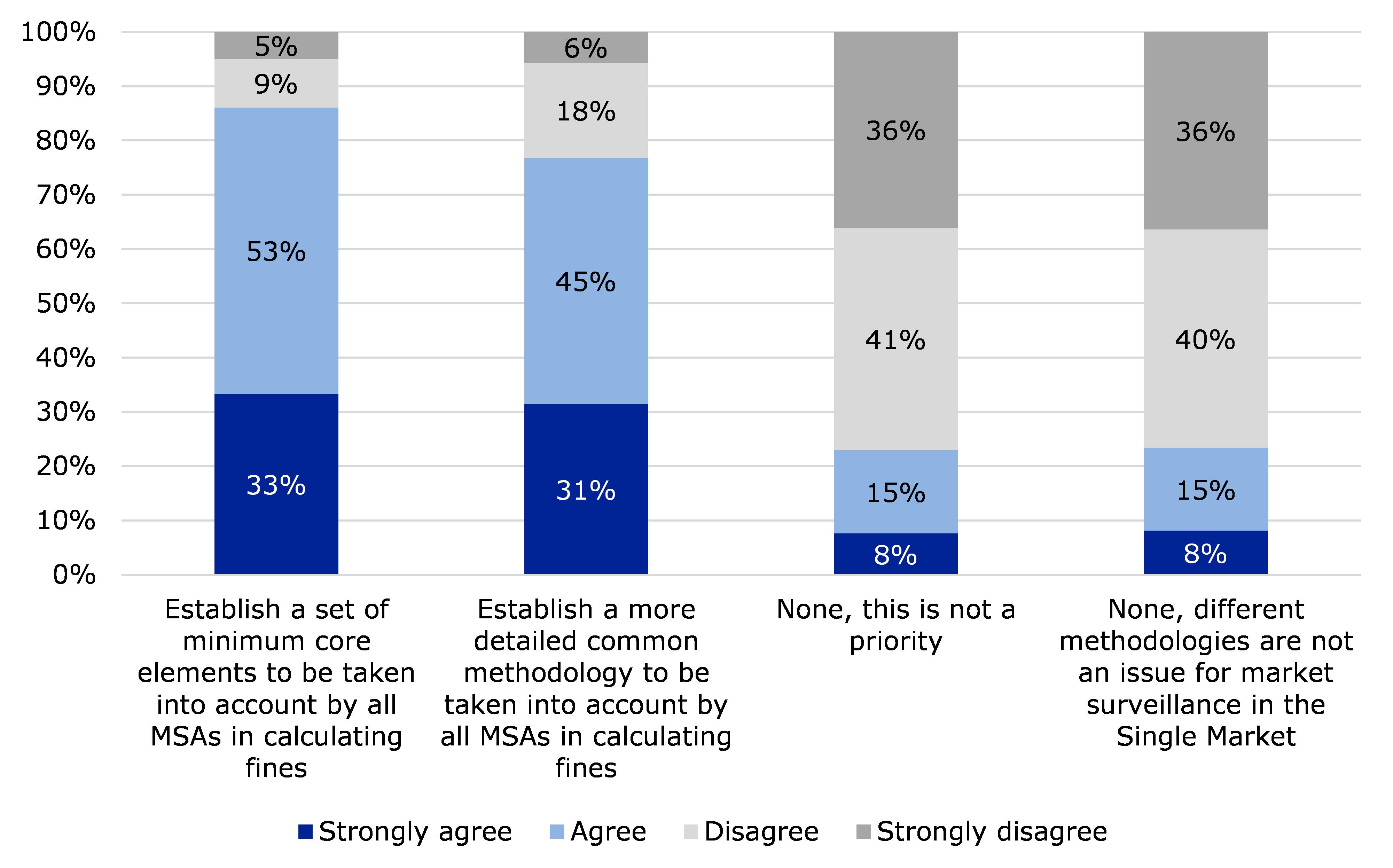

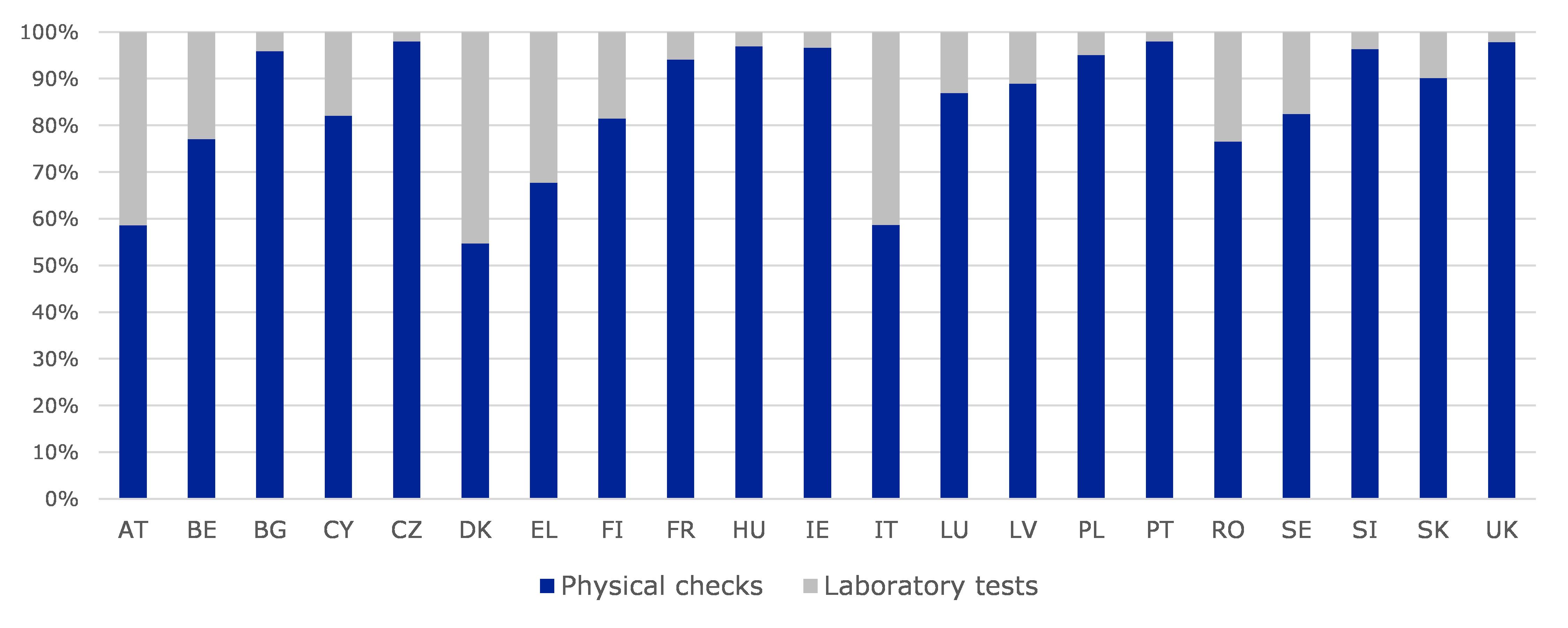

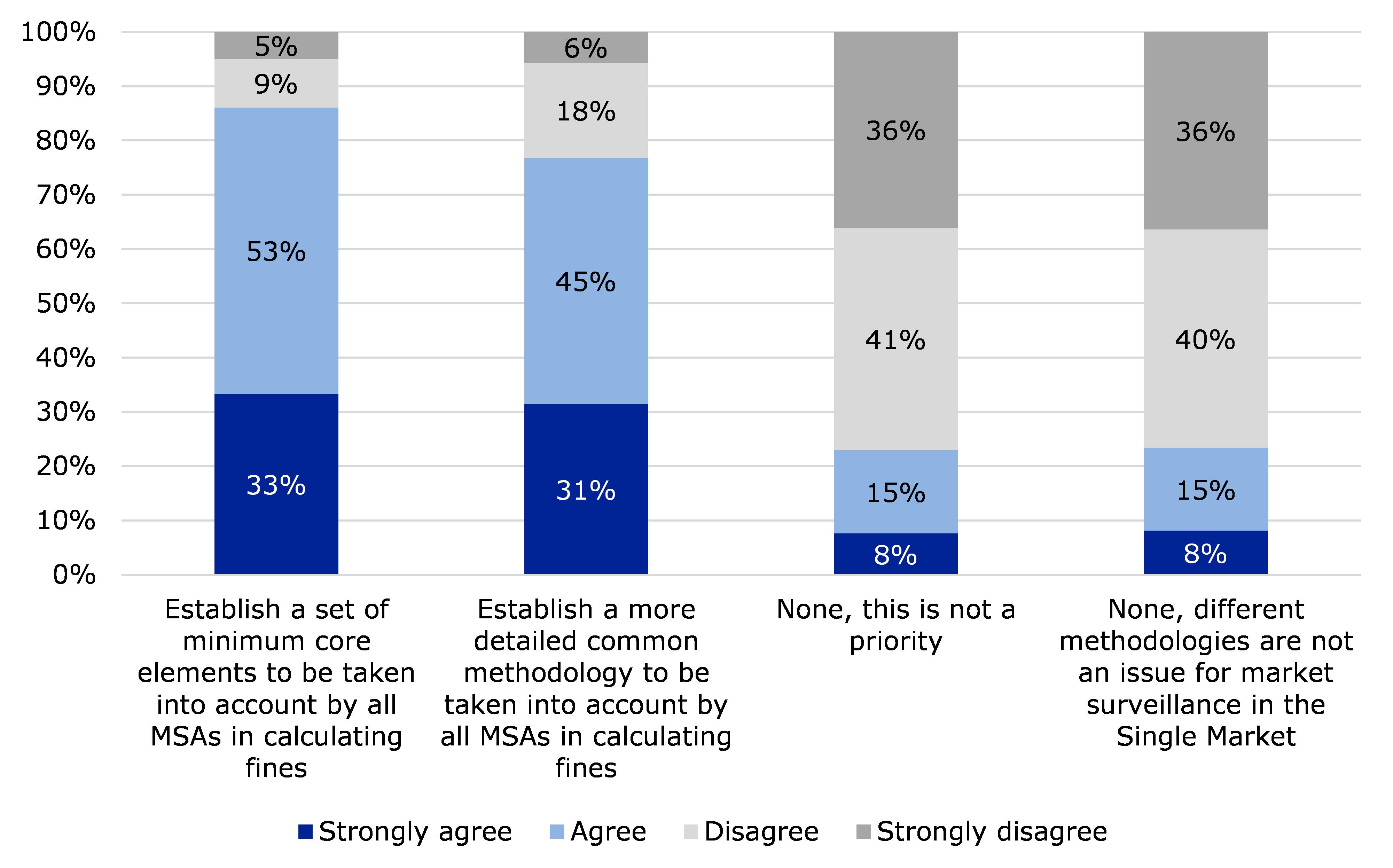

6.1.1.3.AdCos