EUROPEAN COMMISSION

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Brussels, 17.5.2018

SWD(2018) 189 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

IMPACT ASSESSMENT

Accompanying the document

Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council

on the labelling of tyres with respect to fuel efficiency and other essential parameters, and repealing Regulation (EC) No 1222/2009

{COM(2018) 296 final}

{SEC(2018) 234 final}

{SWD(2018) 188 final}

ANNEXES OF THE IMPACT ASSESSMENT

ON THE REVIEW OF THE TYRE LABELLING

REGULATION (EC) No 1222/2009/EC

Table of Content

Annex 1: Procedural information3

Annex 2: Stakeholder consultation6

1.Overview of the respondents to the OPC6

2.Overall results8

3.Detailed results9

3.1.Evaluation of existing tyre label9

3.2.Possible Improvements and additions14

4.In extenso comments from all respondents34

Annex 3: Who is affected and how?56

1.Practical implications of the initiative56

2.Summary of costs and benefits57

3.Estimation of administrative costs58

Annex 4: Analytical methods64

1.General assumptions64

2.Information effect65

3.Stock model assumption65

4.BAU Scenario assumptions66

5.Policy Option 2 scenario assumptions70

6.Policy Option 3 Scenario assumptions70

7.Policy Option 4 scenario assumptions72

8.Effect of Rolling resistance on fuel consumption72

9.Effect of Wet grip on safety74

10.Societal costs78

11.Economy and employment78

12.Label re-adjustment81

12.1Wet Grip81

12.2Rolling Resistance / Fuel Efficiency82

12.3Rolling resistance / Wet grip cross distributions84

12.4Noise (dB)85

12.5Noise (Classes)86

13.Proposal to new label intervals87

13.1Scenario 187

13.2Scenario 292

Annex 5: Evaluation96

1.Introduction - Purpose and scope of the evaluation98

2.Background to the intervention99

2.1.Description of the intervention and its objectives99

2.2.Baseline and points of comparison (BAU)102

3.Implementation / state of Play104

4.Method105

4.1.Short description of methodology105

4.2.Interviews and end-user survey107

4.3.Limitations and robustness of findings108

5.Analysis and answers to the evaluation questions108

5.1.Effectiveness108

5.2.Efficiency116

5.3.Relevance123

5.4.Coherence128

5.5.EU added value132

6.Conclusions134

6.1.What is/is not working and why?134

6.2.The Lessons learnt135

6.3.Actual performance compared to expectations135

6.4.Actions to be taken136

Appendix 1: Stakeholder consultation137

Appendix 2: Methods and analytical models179

Annex 6: Results193

1.List of policy options, including modified policy option193

2.End user expenditure193

3.Economy: Business turnover197

4.Safety and safety costs200

5.Energy and GHG emissions204

Annex 7: Glossary206

Annex 1: Procedural information

1. Lead DG, Decide Planning/CWP references:

Lead DG: Directorate-General for Energy (DG ENER).

The initiative is included in the Commission Work Programme 2018 as agenda planning item: 2016/ENER/040

2. Organisation and timing:

The Inter Service Steering Group met three times: 29 January, 21 February and 6 March 2018. The Inter Service Steering Group included representatives of DGs Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs (GROW), Mobility and Transport (MOVE), Justice and Consumers (JUST), Environment (ENV), Climate Action (CLIMA), the Joint Research Centre (JRC) and the Secretariat General (SG).

3. Consultation of the RSB: The Regulatory Scrutiny Board (RSB) delivered a positive opinion with reservations on a draft of the Impact Assessment on 23 March 2018 after the meeting on 21 March. The following table gives an overview of its main comments and how they have been addressed in the report.

|

RSB Opinion 23.03.2018 : Main comments

|

Where and how the comments have been taken into account

|

|

The report does not adequately present the context of the Tyre Labelling Regulation (TLR), e.g. how it works together with the General Safety Regulation (GSR), Energy Labelling Directive and market surveillance frameworks. It does not present the actual and potential contribution of the labelling scheme to the efficiency and safety of tyres, beyond the requirements put in place by the GSR.

|

An explanation of the Energy Labelling Regulation and the Market Surveillance Regulation, and their relevance, has been added to Section 1.2 on page 4.

The actual contribution of the TLR has been added to the problem definition on page 7.

|

|

The presentation of policy options is not sufficiently clear, nor does it appear to cover the full range of policy issues addressed in the proposal.

|

The table at the beginning of section 5 (page 15) now presents the all the options, and the presentation of the options in section 5.2 (pages 15-26) has been improved. A new Table 4 has been added (page 28) to summarise the options that were discarded at an early stage and options that were modelled.

A more detailed explanation of why Option 4 is the preferred option has been added at page 41 and Table 18 has been made more exact (the mathematical calculations from Table 17 have been translated into half “+” s).

|

|

The report calculates impacts using behavioural assumptions that are neither transparently presented nor accompanied by a sensitivity analysis.

|

A summary of the underlying assumptions of the modelling has been added at the beginning of section 6 (page 29).

A sensitivity analysis on the key behavioural assumptions of consumers has been added to section 8 on the preferred option.

|

|

Specific objectives are missing, as are a good representation of stakeholder views on the different policy options.

|

The specific policy options have been added at the beginning of section 4.2 on page 12. Their monitoring and evaluation has been added to section 9.

A summary of the views of stakeholders by category (industry, Member States and consumers) has been added to Annex 2. Views of stakeholders, from the consumer survey during the review study and the OPC have been added throughout the text where appropriate.

|

4. Evidence, sources and quality:

The impact assessment draws on an extensive amount of desk research, external studies, targeted consultations, interviews, focus groups, workshops and other

This impact assessment is based on the findings from the Review Study carried out in 2016 and the subsequent Open Public Consultation (OPC) , but with market data updated to 2017. The calculations are based on a stock model, determining the number of tyres of each type (C1, C2, C3) in the EU, which is built on annual sales provided by the European Tyre and Rubber Manufacturers Association, ETRMA, combined with ACEA’s (European Automobile Manufacturers Association) annual numbers on vehicles in use in the EU. As part of the 2016 Review Study an extensive stakeholder consultation was performed to assess the efficiency and effectiveness of the label scheme. Stakeholders from across the supply chain were approached to assess their role and whether the TLR was serving its intended purpose. The stakeholder consultation thus included:

·Tyre suppliers;

·Tyre distributors;

·Vehicle suppliers and distributors;

·End users in each tyre segment: C1, C2 and C3.

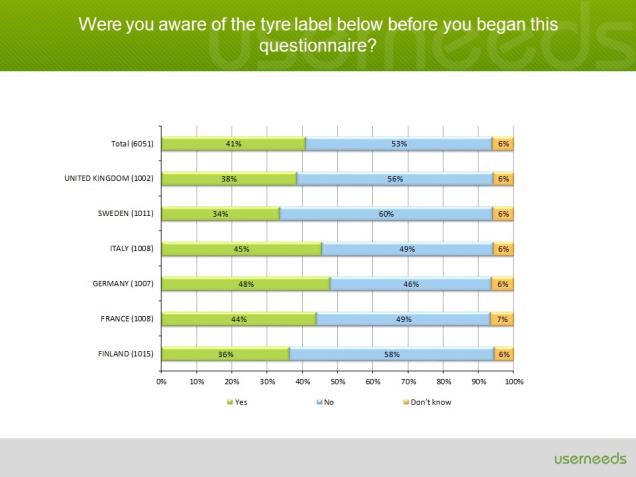

Interviews and questionnaires were conducted with organisations in each segment, and a more thorough consumer survey was carried out in the largest end-user segment: private car owners of C1 vehicles. The C1 consumer survey included 6,000 respondents, a thousand from each of the following six Member States:

•

Germany (~42 million cars)

•

England (~29 million cars)

•

France (~32 million cars)

•

Italy (~37 million cars)

•

Sweden (~4.5 million cars)

•

Finland (~3 million cars)

External expertise was used where necessary, for example the Expert Group on Laboratory alignment for the measurement of tyre rolling resistance under Regulation (EC) No 1222/2009, the International Organization for Standardization, tyre specialists, the European Tyre & Rubber Manufacturers’ Association, the Platform for cooperation between National Road Authorities as well as other studies.

https://www.iso.org/standard/65530.html

,

https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:23671:ed-2:v1

:

http://www.etrma.org

http://www.retyre-project.eu

http://www.transportengineer.org.uk/transport-engineer-news/goodyear-unveils-first-aa-grade-steer-concept-tyre/45469

http://www.cedr.eu

https://www.ecofys.com/files/files/fraunhofer-ecofys-2014-impact-of-ecodesign-energy-labelling-on-innovation.pdf

Annex 2: Stakeholder consultation

The stakeholder consultation took the form of the publication of the combined Evaluation Roadmap and the Inception Impact Assessment for the review of the tyres labelling Regulation in July 2017 and the Open Public Consultation (OPC) that ran from 10 October 2017 to 8 January 2018. The Review study also included an extensive stakeholder consultation, details are given in Appendix 1 to Annex 5.

A.Combined Evaluation Roadmap and Inception Impact Assessment

The roadmap was published on 12 July 2017 with a feedback period till 9 August 2017. Eight feedbacks were received from the following stakeholders:

·Consumer organisations: ANEC and BEUC (Belgium), Deutsche Umwelthilfe e.V. (Germany),

·Company/business organisations: ExxonMobil Petroleum & Chemical B.V.B.A. (Belgium), ENPA & EMMA (Belgium)

·Business associations: Imported Tyre Manufacturers' Association (United Kingdom), BIPAVER (Netherlands), European Tyre & Rubber Manufacturers Association (Belgium), EurEau European Federation of NAtional Associations of Water Services (Belgium)

Stakeholder comments in extenso are available at

http://ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation/initiatives/ares-2017-3509962_en

.

B.Open Public Consultation (OPC)

The Open Public Consultation (OPC) was launched on 10 October 2017 and ended on 8 January 2018 (

https://ec.europa.eu/info/consultations/public-consultation-evaluation-and-review-eu-tyres-labelling-scheme_en

).

1.Overview of the respondents to the OPC

70 responses were received. 20 respondents identified themselves as citizens/consumers (one anonymous), 7 identified themselves as representing commercial tyre business, and 44 identified themselves as working for either an interest organisation or local/national authority (one anonymous). In addition, one stakeholder provided only a written statement (The Association of European Radios). See the list of stakeholder respondents in

Table

1.

Table 1 Overview of stakeholder respondents

|

Category

|

Stakeholder ID

|

Member State

|

|

Tyre suppliers

|

1.Apollo Tyres

|

International

|

|

|

2.Continental Reifen Deutschland GmbH

|

Germany

|

|

|

3.ExxonMobil Petroleum & Chemical BVBA

|

International

|

|

|

4.Goodyear Dunlop Tires B.V.

|

Netherlands

|

|

|

5.Michelin Nordic AB

|

Sweden

|

|

|

6.Nokian Tyres Plc

|

International

|

|

Retailer

|

7.BOVAG

|

Netherlands

|

|

Market surveillance authority

|

8.Swedish Energy Agency in cooperation with other agencies

|

Sweden

|

|

|

9.Swedish Transport Agency

|

Sweden

|

|

Member State government

|

10.Federal Ministry of Environment

|

Belgium

|

|

|

11.Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management

|

Netherlands

|

|

Member State regional or local government authority

|

12.City of Helsinki

|

Finland

|

|

|

13.DCMR EPA/EUROCITIES

|

Netherlands

|

|

|

14.Federal Office for the Environement (FOEN)

|

Switzerland

|

|

|

15.Gemeente Den Haag

|

Netherlands

|

|

|

16.The City of Oslo, Department for Urban Environment

|

Norway

|

|

Non-governmental organisations representing societal interests

|

17.ACP Automóvel Clube

|

Portugal

|

|

|

18.Allgemeiner Deutscher Automobil Club e.V. (ADAC e.V.)

|

Germany

|

|

|

19.ANEC and BEUC

|

EU

|

|

|

20.Association of Austrian Newspapers

|

Austria

|

|

|

21.Association of Dutch Water Companies and the Association of Dutch Water Authorities

|

Netherlands

|

|

|

22.Austrian Journal and Trade Association (ÖZV)

|

Austria

|

|

|

23.Deutscher Verkehrssicherheitsrat e.V.

|

Germany

|

|

|

24.European Association for Accident Research and Analysis (EVU)

|

Austria

|

|

|

25.European Environmental Citizen's Organisation for Standardisation

|

EU

|

|

|

26.Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA Region I)

|

Luxembourg

|

|

|

27.Quercus ANCN

|

Portugal

|

|

|

28.The European Environmental Bureau

|

EU

|

|

|

29.Transport & Environment (T & E)

|

EU

|

|

|

30.ZERO - Associação Sistema Terrestre Sustentável

|

Portugal

|

|

Industry organisations

|

31.Advertising Association

|

United Kingdom

|

|

|

32.Advertising Information Group

|

Germany

|

|

|

33.BDEW Bundesverband der Energie- und Wasserwirtschaft

|

Germany

|

|

|

34.Däckbranschen Sverige AB

|

Sweden

|

|

|

35.European association of television and radio sales houses (EGTA)

|

EU

|

|

|

36.European Caravan Federation

|

Germany

|

|

|

37.European Magazine Media Association

and European Newspaper Publishers' Association (EMMA& ENPA)

|

EU

|

|

|

38.European Tyre & Rubber Manufacturers Association (ETRMA)

|

EU

|

|

|

39.German Insurance Association (GDV)

|

Germany

|

|

|

40.Nordic Logistics Association

|

Norway, Denmark, Sweden

|

|

|

41.Swedish Water and Wastewater Association

|

Sweden

|

|

|

42.The Danish Chamber of Commerce

|

Denmark

|

|

|

43.The European Federation of National Association of Water Services (EurEau)

|

EU

|

|

|

44.Verband der TÜV e.V.

|

Germany

|

|

|

45.Wirtschaftsverband der deutschen Kautschukindustrie e.V.

|

Germany

|

|

|

46.Zentralverband der deutschen Werbewirtschaft ZAW e.V.

|

Germany

|

|

Other

|

47.Commodity producer for tires

|

Germany

|

|

|

48.Solvay Silica (Manufacture of silica for the tire industry)

|

Belgium

|

|

|

49.Type Approval Authority

|

Netherlands

|

|

|

50.Water supply plant

|

Finland

|

|

Citizens / consumers

|

20 respondents identified themselves as citizens and/or private consumers

|

|

Respondents mainly originate from northern/western European countries which are not fully representative of the whole European Union. However it provides some basis for full extrapolation to the rest of EU-28 countries.

2.Overall results

The first part of the questionnaire (question 7 to 10) covered the respondent’s opinion on and experience with the current tyre label. A clear majority of respondents found the label useful and helpful when making a purchasing decision and 83% of respondents found an EU-wide label covering all EU countries a good thing. Understanding the label and its parameters is essential in order for the label to have its intended effect. For people having problems understanding the label parameters, the external noise parameter was the most difficult. 77% did not have any problem understanding any label parameters. 29% considered the wet grip parameter the most important, compared to 16% for rolling resistance and 4% for external noise.

The awareness of the label is high, and a majority of respondents had seen the label in use when purchasing tyres. However, this may be expected given the high share of stakeholder respondents and the results should therefore not be used as a general consumer opinion. 43% did not even see the label beforehand in relation to their last tyre purchase. Either they have purchased through an online shop, which is not covered by the regulation, or the physical shop simply did not have the tyre on display and had to order from stock, in which case the consumer will only see the label when receiving the tyre. A final possibility is that the dealer simply did not comply with the regulation, hence not showing the label.

The second part of the questionnaire (question 11 to 21) covered the respondents' opinion on measures and parameters which could improve the current label. Other safety parameters such as snow and ice grip were considered important to include by the respondents, but opinion was divided whether this information should be mandatory or voluntary. The emphasis on safety parameters is consistent with respondents finding the wet grip parameter the most important in the current label, oppose to environmental and economic parameters such as rolling resistance and external noise. 67% of respondents agreed that re-treaded tyres should be included in the labelling scheme, but only if a reliable methodology can be developed. Opinion was divided on whether studded tyres should be included. The possible reason is that this tyre type is not widespread throughout the EU and therefore only relevant in some countries.

Only 21% believed abrasion was an important parameter to include, the remaining respondents considered it more appropriate to regulate abrasion through other forms of regulation or only include it if accuracy of measurements can be ensured. A slight majority were against mileage being included in the label and respondents in favour emphasized the need for an accurate and economically viable testing method.

The consensus was a need to improve awareness of the label through awareness campaigns, mandatory online labelling, and labelling of OEM

tyres. To improve consumer confidence, respondents agreed on increasing market surveillance and creating a better platform for the authorities to enforce and coordinate activities. Almost all respondents were in favour of establishing a digital registration database. Another measure to improve confidence would be by introducing third-party verification of tyre test results. It was widely agreed by the respondents that this would improve confidence and should be made mandatory.

3.Detailed results

As described in the previous section, the first part of the questionnaire covers the opinion on and experience with the current tyre label used in the evaluation. The second part covers opinion on improvements and additions for a revised regulation subject to this impact assessment. Relevant comments have been selected for each theme. Full comments from all respondents are listed in the end of the annex. Comments from respondents wishing anonymity have been excluded. Questions and selected comments have been themed as follows.

3.0.Evaluation of existing tyre label

Question 7a: Are you aware of the EU labelling scheme for tyres?

Question 7b: In your opinion, is the label a helpful piece of information when deciding which tyres to buy?

Question 7c: Do you think it is a good thing that a single EU-wide label covers tyres sold in all EU countries?

Question 8: Clarity of label. The study found that some consumers did not understand the pictures on the label representing different characteristics of the label (see images below). Which, if any, of the images below do you think is difficult to understand?

Please tick the box(es) above the image(s), if difficult to understand:

|

Figure_1_-

_Fuel_efficiency_pictogram.png

|

Figure_2_-

_Wet_grip_pictogram.png

|

Figure_3_-

_External_rolling_noise_pictogram. png

|

Question 9a: When purchasing your last tyre, did you see the tyre itself beforehand?

Question 9b: Did you see the EU label?

Question 10: Relative importance of label characteristics. Which of the tyre's characteristics currently shown on the label do you consider to be the most important when purchasing a tyre?

Comments on question 10

|

Respondent ID

|

Respondent category

|

|

|

Fazilet Cinaralp

|

An organisation representing industry views

|

All three performances are key for informed decision by the consumer.

|

|

Stephan Rau

|

An organisation representing industry views

|

All three performances are key for informed decision making by the consumer.

|

|

Jos de Gier

|

An organisation representing industry views

|

Most important Wet Grip, secondly RR and less Noise. Overall, these key performances are a good basis for a well-founded buy-decision.

|

|

Christoffer Greenfort

|

An organisation representing industry views

|

Road safety performance.

|

|

Soren Larsen

|

An organisation representing industry views

|

We believe fuel efficiency, wet and winter grip and noise are important characteristics.

|

|

Martina Petkova

|

A business manufacturing or involved in the trading of tyres

|

All three performances contribute to increase the safety as well as the economic and environmental efficiency of road transport and are thus equally important. Consumers should decide based on needs.

|

|

Susanne Buchholz

|

A business manufacturing or involved in the trading of tyres

|

As in tyre development various performances need to be balanced, it is important to show at least two conflicting characteristics - e.g. fuel efficiency (environment) and wet grip (safety).

|

|

Andrew Bassett

|

A business manufacturing or involved in the trading of tyres

|

A critical parameter is absent that affects all aspects of tire performance: air retention. This parameter could be accounted for without necessarily being shown as an additional label criterion.

|

|

Hans Norén

|

Swedish Transport Agency, regulatory authority for tires (MSA)

|

Ice grip.

|

|

Schneuwly Dominique

|

A Member State regional or local government authority

|

One characteristic is only valuable if the others are visible too.

|

|

Johan Sliggers

|

A Member State government

|

It is customer choice what characteristic he finds most important. In the tyre awareness campaign in the NLs the choice is often safety (wet grip).

|

|

Marina Lukovnikova

|

A Member State government

|

We provide the answer as the authority, not as a consumer. All parameters are important, in different aspects.

|

|

Guido Gielen

|

A non-governmental organisation representing societal interests (for example, environmental or consumer interests)

|

1) Its wet grip performance; 2) wear/life and 3) price seem to be the most important considerations for many

|

|

|

Citizen/consumer (NL)

|

All three characteristics, as well as the wear factor.

|

|

|

Citizen/consumer (IT)

|

Its grip on dry surfaces, its grip on wet surfaces and its performance in terms of fuel economy.

|

General comments related to evaluation of existing tyre label

ANEC/BEUC (Consumer association): “External rolling noise performance does not deliver useful consumer information.”

FOEN (Member State regional or local government authority):“Reconsider noise pictogram (smileys? :-) / :-I / :-( , add colour?)”

3.1.Possible Improvements and additions

3.1.0.Awareness and online labelling

The following table gives an overview of the answers provided by each main stakeholder group regarding awareness raising and online labelling. Detailed answers can be seen after the summary table.

|

Respondent category

|

Summary of answers

|

|

Industry

|

Most of the respondents representing industry agree that label information should always be provided before purchase, also by businesses selling vehicles. To improve the awareness of the label they believe the most beneficial option would be to encourage Member States to run awareness campaigns and that online labelling would improve the visibility of the label.

|

|

Governmental organisations

|

Most of the respondents representing governmental organisations agree that label information should always be provided before purchase, also by businesses selling vehicles and that online labelling would improve the visibility of the label. Regarding how to improve the awareness of the label the governmental organisations have no preferred option as their answers are divided on different suggestions.

|

|

Non-governmental organisations

|

Most of the respondents representing non-governmental organisations agree that label information should always be provided before purchase, also by businesses selling vehicles. To improve the awareness of the label they believe the most beneficial option would be to encourage Member States to run awareness campaigns and that online labelling would improve the visibility of the label.

|

|

Consumers

|

Most of the consumers agree that label information should always be provided before purchase, also by businesses selling vehicles. To improve the awareness of the label they believe the most beneficial option would be to encourage Member States to run awareness campaigns and that online labelling would improve the visibility of the label.

|

Survey results:

Question 11: Information on all tyres. The study found that most people are not offered a choice of tyres when purchasing a vehicle. Do you agree that businesses selling a vehicle should always provide tyre labelling information for the tyres fitted on that vehicle, including in situations when the customer is not given a choice of tyres?

Question 12: Raising awareness. The study found that some consumers and organisations were not aware of tyre labelling or the benefits of investing in fuel-efficient tyres. Which of the following options (if any) would you like to see included in the Regulation in order to raise awareness?

Comments on question 12

|

Respondent ID

|

Respondent category

|

|

|

Bertrand Vallet

|

An organisation representing industry views

|

Microplastics release during the use phase

|

|

Soren Larsen

|

An organisation representing industry views

|

Marking 3PMSF for winter tyres, tested in accordance with UNECE R117 Annex 7. And categorise tyres in general: A, B, C...

|

|

Ines Nitsche

|

An organisation representing industry views

|

There should be no extension of the system to other types of advertising media as this would threaten the refinancing of the media and thus the editorial reporting.

|

|

Katja Heintschel von Heinegg

|

An organisation representing industry views

|

Under no circumstances should the requirement to disclose relevant environmental properties in media advertising be extended in the course of any revision of the Regulation.

|

|

Marie De Cordier

|

An organisation representing industry views

|

Raise awareness through more effective provision of information at the point of sales when the consumer is in the process of making a purchasing decision.

|

|

Martina Petkova

|

A business manufacturing or involved in the trading of tyres

|

Further encourage Member States to offer purchasing incentives for tyres of label grades A-C (rolling resistance, wet grip) and aim for such tyres in public procurement.

|

|

Andrew Bassett

|

A business manufacturing or involved in the trading of tyres

|

Label criteria should be tested under 'in-use' conditions. Most tyres in the EU don't run at optimum pressure. Consumer confidence will increase if reported performance is closer to actual performance

|

|

Johan Sliggers

|

A Member State government

|

The NLs is facilitating a campaign to raise awareness of the importance of tyres: www.kiesdebesteband.nl

|

|

Schneuwly Dominique

|

A Member State regional or local government authority

|

Reconsider information on the tyres (is everything still needed?), add and highlight label data ON tyre.

|

|

Guido Gielen

|

A non-governmental organisation representing societal interests (for example, environmental or consumer interests)

|

Tyre choice has some influence on fuel economy but tyre pressures and driver behaviour are bigger, more significant factors. Label would need to offer better consumer relevant information

|

|

Aline Maigret

|

An NGO representing societal interests (for example, environmental or consumer interests)

|

There is a need for campaigns promoting the label but also explaining the meaning of the parameters/logos (including the safety and environmental benefits) especially if new parameters are added.

|

|

Verband Österreichischer Zeitungen

|

Other

|

Awareness-raising measures are useful, but should be carried out on a private-sector basis, not by additional. Labelling rules relating to advertising media.

|

Question 13: Pre-sale provision of information. The study found that the label is often not visible to customers when they buy tyres. Which of the following options (if any) would in your opinion improve the visibility of the label to customers?

General comment related to awareness and online labelling

ANEC/BEUC (Consumer association):“There is a need for better visibility of the label, hence awareness raising campaigns are necessary.”

3.1.1.Market surveillance and third-party verification

The following table gives an overview of the answers provided by each main stakeholder group regarding market surveillance and third-party verification. Detailed can be seen after the summary table.

|

Respondent category

|

Summary of answers

|

|

Industry

|

The industry respondents are divided in terms of whether third-party verification would improve the accuracy of the information on the label and whether to introduce third-party verification as a requirement. Furthermore, they are divided on how to improve market surveillance and no preferred option for industry can be identified.

|

|

Governmental organisations

|

Most of the respondents representing a governmental organisation believe that third-party verification would improve the accuracy of the information on the label and it should be introduced as a requirement. Regarding market surveillance they believe that better sharing of results between surveillance authorities could improve market surveillance.

|

|

Non-governmental organisations

|

Most of the non-governmental organisation respondents believe that third-party verification would improve the accuracy of the information on the label and it should be introduced as a requirement. Regarding market surveillance they believe it would be beneficial if the wet grip testing is updated and the results between surveillance authorities are shared with the industry.

|

|

Consumers

|

Most of the consumers believe that third-party verification would improve the accuracy of the information on the label and it should be introduced as a requirement. Regarding market surveillance they believe that better sharing of result between surveillance authorities could improve market surveillance.

|

Survey results

Question 14a: Would you be more confident of the accuracy of the label's information if third-party verification of tyre test results were mandatory?

Question 14b: In your opinion, should third-party verification of tyre test results be introduced as a requirement?

Question 15: Market surveillance. The study found that some areas and some Member State authorities were not as good as others at checking if labels were accurate or were being shown to customers. Which of the following options (if any) would in your opinion improve market surveillance?

Comments on question 15

|

Respondent ID

|

Respondent category

|

|

|

Fazilet

Cinaralp

|

An organisation representing industry views

|

MSAs should build skills and testing capabilities to make regular, more coordinated and more visible enforcement actions through market surveillance. This market surveillance activity should involve all 28 MSAs. Meaningful penalties must be established by Member States in case of non-compliance

|

|

Stephan Rau

|

An organisation representing industry views

|

MSAs should build up skills and testing capabilities. This to make regular, more coordinated and more visible enforcement actions through market surveillance. This market surveillance activity should involve all 28 MSAs in Europe. Meaningful penalties must be established by Member States in case of non-compliance.

|

|

Jos de Gier

|

An organisation representing industry views

|

Test spread reduction of the current Wet Grip test, by modifying the test method and/or calculation method for the final result. Meaningful penalties in case of non-compliance.

|

|

Martina Petkova

|

A business manufacturing or involved in the trading of tyres

|

The further development of market surveillance capability and capacity at member state level would best support to improve market surveillance. The launch of the joint market surveillance initiative MSTyr15 is an excellent tool to enhance a high level surveillance system in Europe.

|

|

Susanne Buchholz

|

A business manufacturing or involved in the trading of tyres

|

Continental is convinced that market surveillance of label performance through regular spot check testing (not simply verification of documents) with meaningful penalties provide the most effective and efficient tool to ensure reliable labelling and a level playing field. The self-certification requirements reflect the available testing infrastructure. If only third party testing was allowed, this would create unacceptable delays/costs for the tyre industry and disadvantages also to consumers.

|

|

Johan Sliggers

|

A Member State government

|

On testing: Fuel efficiency and noise get better when tyres wear. This is not the case with wet grip. There, the braking distance increases with wear. The standard for wet grip should include a maximum detoriation for worn tyres.

On labels on each batch: every new batch need new testing and possibly a different label

On better sharing of test results: make all test data available in an uniform format on the internet.

See document Tyres in Europe for more detail.

|

|

Henk Wolfert

|

A Member State regional or local government authority

|

Maybe tests under real driving conditions could change the order of A-G labels?

|

|

Aline Maigret

|

A non-governmental organisation representing societal interests (for example, environmental or consumer interests)

|

-A centralised registration database that provides solid information to consumers in order to make an informed choice. As the Commission is setting up a database for the Energy label, the possibility of using it to tyre labelling information should be investigated.

-Non-compliant manufacturers should be fined with penalties that are dissuasive and in proportion to the damage caused to consumers and the environment. Several consumer tests have shown discrepancies with manufacturer's test results

|

|

Nerea Ruiz

|

A non-governmental organisation representing societal interests (for example, environmental or consumer interests)

|

Inclusion on the automotive database

|

|

Stephane Arditi

|

A non-governmental organisation representing societal interests (for example, environmental or consumer interests)

|

For better sharing of results, go beyond industry and make them available to all, notably by publishing on the automotive database

|

|

Laura Carvalho

|

A non-governmental organisation representing societal interests (for example, environmental or consumer interests)

|

Inclusion in the automotive database

|

|

|

Citizen/consumer (NL)

|

Does enforcement also monitor the values on the label? Perhaps EU-wide joint check and publish results (perhaps à la EURO-NCAP by a consumer organization)

|

|

|

Citizen/consumer (FI)

|

Randomly check if the claimed performance on the label matches the performance of the tyres when sold.

|

General comments related to market surveillance and third-party verification

Consumer: “[…] it was a suspicion that lower quality brands were not as diligent when obtaining data; this needs to be thoroughly audited in all companies supplying the EU.”

ETRMA (industry organisation):“Industry does not support introducing independent third party testing of the tyre performance. [Instead market surveillance should be] “Increased, more coordinated, more visible enforcement actions through market surveillance is needed.”

ANEC/BEUC (consumer association): "Market surveillance is not adequately carried out and therefore enforcement of the legislation must be improved. Sanctions must be applied in case of non-compliances.”

Goodyear (manufacturer): "[…] efforts should be dedicated to further increase awareness and market surveillance efforts. […] A highly developed market surveillance system with regular surveillance activities at Member States’ level as well as a meaningful set of penalties is important to ensure compliance with the regulation. […] third party testing might be disproportionate to the available infrastructure of testing institutes/type approval authorities’ laboratories, [and] create unacceptable delays and costs for the tyre industry […]”

FOEN (other):“Independent testing is needed in order to guarantee some degree of credibility of the label information.”

Verband der TÜV e.V. (industry association): A label based on the neutrality and competence of a third party organization would make a positive contribution to the confidence of market participants and provide the consumer with a valuable means of orientation, enabling them to compare products realistically. Therefore a system of mandatory confirmation tests such as Conformity of Production (CoP), performed by third-party laboratories, should be implemented.

3.1.2.Ice and snow grip

The following table gives an overview of the answers provided by each main stakeholder group regarding ice and snow. The detailed answers can be found after the summary table.

|

Respondent category

|

Summary of answers

|

|

Industry

|

The respondents representing industry think that information on snow and ice performance of a tyre should be included in the label, but are divided on whether it should be mandatory or voluntary.

|

|

Governmental organisations

|

The respondents representing governmental organisations think that information on snow and ice performance of a tyre should be included in the label but are divided on whether it should be mandatory or voluntary.

|

|

Non-governmental organisations

|

The respondents representing non-governmental organisations think that information on snow and ice performance of a tyre should be included in the label but are divided on whether it should be mandatory or voluntary.

|

|

Consumers

|

Consumers think that information on snow and ice performance of a tyre should be included in the label as a mandatory requirement.

|

Survey results:

Question 16: Snow and ice performance. The tyre label does not currently include information on tyres primarily designed to perform better in ice and/or snow conditions. Do you think that information on snow and ice performance of a tyre should be included in the label?

General comments related to ice and snow grip

ANEC/BEUC (consumer association):“Although good grip on icy road is one of the most important characteristic, there is no information on this in the current label. According to a study from Nokia tyres, the wet grip pictogram is misleading in Nordic countries.”

Goodyear (manufacturer):“[…] either category of winter tyres, i.e. snowflake-marked tyres, and ice tyres (with their future official marking) should be entitled to only one extra logo on the EU label. [and] should be added to the EU tyre label on a voluntary basis […]”

Solvay (“To ensure people safety (wet grip) in winter conditions, we recommend to create a Snow and Ice label”

Swedish Energy/Chemical/Transport Agencies: “Without complementary information about tyre performance under snowy and icy conditions, consumers could choose the wrong type of winter tyre. This is particularly true when consumers buy tyres on the internet without the possibility of speaking with a representative who can answer questions about the product.”

3.1.3.Studded and retreaded tyres

The following table gives an overview of the answers provided by each main stakeholder group regarding studded and retreaded tyres. Detailed answers and question phrasings can be seen after the summary table.

|

Respondent category

|

Summary of answers

|

|

Industry

|

Most respondents representing the industry suggest including retreated tyres if accuracy of the measurement methods can be ensured. Regarding studded tyres most industry respondents had no opinion.

|

|

Governmental organisations

|

Most respondents representing a governmental organisation suggest including retreated tyres if the accuracy of the measurement can be ensured, but they do not believe that studded tyres should be included.

|

|

Non-governmental organisations

|

Most respondents representing a non-governmental organisation suggest including retreated tyres if the accuracy of the measurement can be ensured but they have no opinion whether studded tyres should be included.

|

|

Consumers

|

Most consumers suggest including retreated tyres if the accuracy of the measurement can be ensured but they have no clear opinion whether studded tyres should be included.

|

Survey results:

Question 17: Re-treaded bus and truck/lorry tyres ("C3"). Currently, a label is not required for re-treaded tyres. Re-treading tyres can extend the life of used tyres by replacing worn-out tyre tread, contributing to the circular economy. The study found that there was currently no widely accepted method for measuring the fuel efficiency of re-treaded tyres. Should re-treaded tyres be included in the labelling scheme?

Question 20: Studded tyres. The study found that in countries where studded tyres are used frequently, national measures to ensure their safety and reduce their environmental impact already exist. In some EU Member States, studded tyres are banned. In addition, no method exists for comparing studded tyres to regular tyres for fuel efficiency and wet grip. Should studded tyres be included in the labelling scheme?

General comments related to studded and retreaded tyres:

City of Helsinki: “In Helsinki, 75-80% of C1 and C2 vehicles use studded tyres during winter. This has significant local environmental impacts mainly in the form of elevated noise levels and PM10 dust particles from road and tyre wear. City of Helsinki aims to mitigate the harmful effects of studded tyre use by raising awareness on the matter and providing citizens with fact-based information to help them make more environmentally friendly decisions when choosing winter tyres (non-studded winter tyres over studded tyres). Providing information on snow and ice performance, and possibly abrasion in the tyre label, as well as including studded tyres in the labelling scheme would contribute to that cause.”

3.1.4.Mileage and abrasion

The following table gives an overview of the answers provided by each main stakeholder group regarding mileage and abrasion. Detailed answers and question phrasings can be seen after the summary table.

|

Respondent category

|

Summary of answers

|

|

Industry

|

Most respondents representing the industry do not suggest including mileage information or abrasion information on the label, and there is general agreement that concerns about abrasion are more appropriately addressed through other forms of regulation.

|

|

Governmental organisations

|

Respondents representing a governmental organisation suggest including abrasion information if the accuracy of the measurement can be ensured. The governmental organisation respondents are divided regarding whether mileage information should be included on the label.

|

|

Non-governmental organisations

|

Most respondents representing a non-governmental organisation suggest including both mileage information and abrasion information on the label.

|

|

Consumers

|

The consumers answers are very divided and there is no clear opinion on information on mileage and abrasion on the label.

|

Survey results

Question 18: Mileage. Currently, tyre mileage information (the total distance that tyres can be expected to last for) is not included in the label. The study found that mileage in tyres is very difficult to test or monitor accurately. The tests that do exist are expensive and tend to be bad at measuring "real-life" mileage (that is, outside laboratory conditions). Should mileage information be included in the label?

Question 19: Abrasion and microplastics. Currently, information about abrasion (the removal of material from the tyre when it interacts with the road surface) is not included in the label. Abrasion contributes to a significant percentage of microplastics (small plastic particulates) in the ocean and to air pollution through so-called tyre road wear particles. The study found that there was currently no accurate way of measuring abrasion, and that other legislation already exists to regulate the chemical content of tyre materials. Should abrasion information be included in the label?

General comments related to mileage and abrasion

T&E (NGO): “As regards test methodology on mileage, much progress has been made at UNECE level since the Commission study on the EU Tyre Label was commissioned. […] the Real-world Driving Emissions (RDE) tests recently introduced for cars, it is possible to test tyres' durability in real world conditions and the costs will come down as the tests are more widely used.”

ETRMA (industry organisation):"ETRMA believes that the labelling scheme is by no means appropriate to address this [abrasion] complex question.”

ZERO - Associação Sistema Terrestre Sustentável (NGO):“If these [mileage and abrasion] parameters are not included in the current regulation, the Commission should now, at the very least, request that robust and representative methods are developed for these parameters.”

The European Environmental Bureau (NGO):“As regards measurement methodologies not being developed or agreed yet, a mandate should be issued asap to standardisation bodies by EC to make sure this situation will not be perpetuated and used as an argument to not take action in the future. In the meantime, transitional methods could be suggested and/or simple information provided (e.g on abrasion and microplastics).”

BDEW Bundesverband der Energie- und Wasserwirtschaft (industry organisation):“Incentives should be created to develop tires with less microplastic abrasion. With regard to microplastic abrasion, grading / differentiation in labelling would be important in order to provide the consumer with information for a purchase decision.” [Machine translated]

EurEau (industry organisation):“We would highlight that abrasion contibutes to microplastics in WATER RESOURCES, and not directly water supply. Since the tyres are an important source of microplastics emitted to the aquatic environment, the labelling scheme should include microplastics emissions during normal wear and tear as an indicator.”

3.1.5.Digital registration database

The following table gives an overview of the answers provided by each main stakeholder group regarding a digital registration database. Detailed answers can be seen after the summary table.

|

Respondent category

|

Summary of answers

|

|

Industry

|

The majority of respondents representing industry are in favour of setting up a digital registration database and providing public information about tyres to inform consumers and also provide information about tyres to make it easier for authorities to check that labels are correct.

|

|

Governmental organisations

|

All respondents representing governmental organisations suggest that a digital registration database should be set up and provide public information about tyres to inform consumers and also provide information about tyres to make it easier for authorities to check that labels are correct.

|

|

Non-governmental organisations

|

Most respondents representing a non-governmental organisation suggest that a digital registration database should be set up and provide public information about tyres to inform consumers and also provide information about tyres to make it easier for authorities to check that labels are correct.

|

|

Consumers

|

The vast majority of consumers suggest that a digital registration database should be set up and provide public information about tyres to inform consumers and also provide information about tyres to make it easier for authorities to check that labels are correct.

|

Survey results

Question 21a: Should a digital registration database providing information about tyres be set up?

Question 21b: If a digital registration database should be set up, what sort of information should it provide?

General comments related to digital registration database

ANEC/BEUC (consumer association):“The possibility of using the database currently being set up for the EU energy label should be investigated for the tyre labelling scheme.”

Goodyear (manufacturer):“[…] in light of additional management and administrative cost involved we do not deem it necessary to introduce another database at European level.“

FOEN (Swiss federal office for environment):“A public database containing data of all sold tyres is needed (for information AND controlling purpose) […]”.

3.1.6.Small and Medium Sized Enterprises (SMEs)s

General comments related to SMEs:

European Caravan Federation (industry organisation):“Motor caravans are generally built by SMEs using multi-stage builds. The tyres for the completed vehicle are provided as part of the base vehicle and not by the final stage manufacturer. Any requirements for provision of information to the consumer must therefore be carefully considered in respect of these vehicles to ensure that undue burden is not placed onto these SMEs.”

3.1.7.Advertisement

General comments related to advertisement

The Association of European Radios“AER believes that, especially when it comes to radio, advertising is not the right place to insert detailed information. It does not and cannot provide all information necessary for the final purchase decision. The consumers’ decision is based on many other sources, such as brochures and websites, and information collected at the point of sale. […] Consequently, AER calls for the status quo regarding advertising rules contained in the Tyre Labelling Regulation: i.e. no labels or terms and conditions inserted in tyre advertisements in billboards, newspapers, magazines, radio broadcasting, television and similar online formats.”

EMMA/ENPA (industry organisation):“We would in particular like to comment on the suggestion to extend technical information on tyre efficiency to advertising, specifically in magazines and newspapers. It is our view that a mandatory inclusion of such information would be inefficient and would in the process have negative effects on the value of advertising in both print media and digital media.”

ÖZV (NGO): “A widening of the requirements for compulsory information in advertisements leads to a situation that makes the advertising as a whole unattractive.” [Machine translated]

European association of television and radio sales houses (industry organisation):“[…] TV and radio advertisements [..] are not optimal platforms for conveying technical information in a meaningful way to consumers. […] the potential negative impact that mandatory information messages would have on TV and radio revenues could be significant”

Zentralverband der deutschen Werbewirtschaft (industry organisation):“[The label should be] made available to the consumer only where he / she takes note of the information in a manner relevant to the purchase decision. This does not usually take place via the media advertising […]”

3.1.8.Rescaling

General comments related to readjustment:

ETRMA (industry organisation):“It is considered premature to revise the labelling scale requirements for both wet grip and fuel efficiency, and even noise, while efforts should be dedicated to increase awareness and market surveillance efforts”

Goodyear (manufacturer):“Goodyear supports the conclusion of the Viegand Maagoe study stating that it is premature to revise the labelling scale for any of the three tyre label performances […]”

3.1.9.Testing standards

General comments related to testing standards

“The boundary conditions are too broadly defined (road test surface, temperatures, test vehicle.”, “The label says nothing about the absolute, achievable braking distances” [FIA]

ExxonMobil Petroleum & Chemical BVBA (tyre supplier):“A revised rolling resistance coefficient (RRC) standard test and rating that requires RRC average over time vs. a single data point under optimal conditions”

ETRMA (industry organisation): ETRMA is recommending introducing the new revised test method [for wet grip] at the current planned revision of the tyre label scheme.”

3.1.10.Additional suggestions

Däckbranschen Sverige AB (industry organisation):“It would be desirable to investigate the possibility of also obtaining information in the tire label regarding performance throughout the lifetime.”

Solvay Silicia“It is important to monitor how the overall tire performances (Rolling Resistance, Wet Grip, Noise) age during the tire lifecycle (e.g.: performance variation after 10 000 Km, 20 000 Km, above 30 000 Km)”.

ExxonMobil Petroleum & Chemical BVBA (tyre supplier):“A key aspect is inflation pressure loss rate (IPLR) performance. Specifying tyres with a maximum IPLR of e.g. 2% or 2.5% (which could also be progressively reduced in response to market demands and technology developments) should promote improved IPLR performance of tyres in the EU.

“The regulation should integrate a clear obligation to manufacturer (supplier) to fulfil compliance evaluation procedure, including periodical control of production.”

“The text of regulation may be improved for more clarity. Market surveillance authorities and even laboratories have sometimes difficulties to interpret the text in the same way.” [Federal Ministry of Environment]

4.In extenso comments from all respondents

“As an ex-employee of a large tyre company, I know the vast sums of money invested in getting data for these types of test & it was a suspicion that lower quality brands were not as diligent when obtaining data; this needs to be thoroughly audited in all companies supplying the EU.” [Consumer]

The European Caravan Federation (ECF) is the umbrella organisation representing the national organisations of the European Caravanning Industry. Membership of the ECF consists of 12 caravanning federations and numerous national members of the caravanning industry within the EU member states. These members are involved in the production, the sales and the use of touring caravans, motor caravans and the supply of specialist parts and services to the industry.Motor caravans are manufactured by small and medium sized manufacturers in quantities from 10 to 10.000 annually. Motor caravans are generally built by SMEs using multi-stage builds. The tyres for the completed vehicle are provided as part of the base vehicle and not by the final stage manufacturer. Any requirements for provision of information to the consumer must therefore be carefully considered in respect of these vehicles to ensure that undue burden is not placed onto these SMEs. [European Caravan Federation]

In Helsinki, 75-80% of C1 and C2 vehicles use studded tyres during winter. This has significant local environmental impacts mainly in the form of elevated noise levels and PM10 dust particles from road and tyre wear. City of Helsinki aims to mitigate the harmful effects of studded tyre use by raising awareness on the matter and providing citizens with fact-based information to help them make more environmentally friendly decisions when choosing winter tyres (non-studded winter tyres over studded tyres). Providing information on snow and ice performance, and possibly abrasion in the tyre label, as well as including studded tyres in the labelling scheme would contribute to that cause. [City of Helsinki]

As regards test methodology on mileage, much progress has been made at UNECE level since the Commission study on the EU Tyre Label was commissioned. Thus Question 18 above somewhat prejudges the answers and influences the audience by claiming that the tests are "expensive and inaccurate"; this is a subjective view. Similarly to the Real-world Driving Emissions (RDE) tests recently introduced for cars, it is possible to test tyres' durability in real world conditions and the costs will come down as the tests are more widely used. Most drivers fall within the 70-80% of all driving conditions, and so called boundary conditions to mirror the on-road use can be introduced, as was successfully done in RDE. As regards question 21 on database, synergies should be sought with the provisions on online exchange platforms agreed as part of the new Type Approval and Market Surveillance regulation - the information on tyres should be added into one common EU database on type approval of vehicles, their parts and components. [Transport & Environment]

An ice-labelling mark is very important for the Nordic market [Michelin Nordic AB]

“Although the tyre label is an important tool for consumers across Europe to take an informed decision, there is a need to review the current regulation, and to launch the impact assessment. We reiterate our position:

- the methodology used to define the energy classes of tyres must reflect real life performance, hence providing accurate and transparent information to consumers. Currently, we fear that manufacturers are often using loopholes in the methodology as well as tolerances in order to reach higher energy classes. It is misleading information for consumers. The methodology needs to be updated.

-There is a need for better visibility of the label, hence awareness raising campaigns are necessary.

-Market surveillance is not adequately carried out and therefore enforcement of the legislation must be improved. Sanctions must be applied in case of non-compliances.

-Regarding the current criteria, we believe that wet grip performance is the most important parameter because of its impact on safety. Fuel efficiency performance is important as long as there is no trade-off between rolling resistance and wet breaking because they can put conflicting demands on tyres which should be prevented. Innovation in recent years has shown that it is possible to improve wet grip and fuel efficiency simultaneously. External rolling noise performance does not deliver useful consumer information.

-The range of performance parameters on the label is too limited. The label could be extended to snow and ice grip. Although good grip on icy road is one of the most important characteristic, there is no information on this in the current label. According to a study from Nokia tyres, the wet grip pictogram is misleading in Nordic countries.

-the impact assessment should consider sustainability and that additional comprehensive tyre wear tests are needed.

- the logo representing the parameter must be tested among consumers to ensure the comprehensibility. Overall the whole label should be tested upfront through consumer survey.

- Manufacturers and dealers need to make the label available to consumers before the purchase decision (alignment with the Energy labelling Directive).

- the possibility of using the database currently being set up for the EU energy label should be investigated for the tyre labelling scheme.” [ANEC/BEUC]

For the parameters where it is indicated that measurement methods do not exist, or are not accepted/reliable, further investigation may be required. If these parameters are not included in the current regulation, the Commission should now, at the very least, request that robust and representative methods are developed for these parameters. Considering that the standardisation community might not be interested in developing those without a request (or may even not have an interest in “widely accepting” methods that are available), such a Commission request would at least attempt to avoid facing exactly the same situation when a future review or revision takes place.Additionally, consumer understanding of the label should remain a priority, and hence, we invite the Commission to have a consumer understanding assessment, as for other Energy Labels under discussion. [European Environmental Citizen's Organisation for Standardisation]

The Label aims to encourage the market uptake of energy saving products and aims to encourage the manufactures in technological development. However, the tyre particularity is safety: tyre is the only contact between the vehicle and road. Therefore it is necessary to have a safety performance presented in the EU tyre labelling. Currently it is the information on the wet grip performance of a tyre. Wet grip and ice grip are technically nearly opposite tyre performances and in Nordic winter weather conditions the ice grip is the most critical tyre performance. From this it follows that the Label may offer a wrong view compared to what Nordic citizens need and the consumer may become mislead and buy a wrong tyre for his or hers needs. In this way the winter time road traffic safety is decreased and the inapplicability of the tyre Label may question the credibility of the EU energy efficiency policy in Nordic countries. The above-mentioned, however, concerns mainly the C1 class tyres. Tyres in class C2 could be added in the scope later when such test method specification has been developed. Tyres in class C3 should be left out of the ice grip marking.Winter tyre technologies improve road traffic safety and help to decrease the number of traffic accidents. There are big differences between different types of winter tyres. EU Tyre Labelling may create a safety risk in Nordic countries’ winter time road traffic. Snow and/or ice grip markings should be added to the EU Tyre Label. According to the Article 11 of the Reg. EC/1222/2009 it is possible to amend the Regulation to add information regarding ice and/or snow performance through delegated powers of the European Commission. [Nokian Tyres Plc]

“General Comment on Market Transformation: Goodyear supports the conclusion of the Viegand Maagoe study stating that it is premature to revise the labelling scale for any of the three tyre label performances, while efforts should be dedicated to further increase awareness and market surveillance efforts. Tyre development faces a multiple set of customer-oriented performance requirements which often conflict with each other. Tyre technology has been evolving and the EU tyre label has been a driver for that. According to the report from the European Commission (COM 2017-658/final) market penetration for the best energy efficiency classes (A and B) in fuel efficiency and wet grip is still very low (<1% for all tyre types). This reflects that the current scaling system of the three performance categories is already challenging and will remain such in the foreseeable future.

Third Party Verification: A highly developed market surveillance system with regular surveillance activities at Member States’ level as well as a meaningful set of penalties is important to ensure compliance with the regulation. In this context third party testing might be disproportionate to the available infrastructure of testing institutes/type approval authorities’ laboratories, while not proven as a need from effectiveness and efficiency perspectives. If only third party was allowed, this would create unacceptable delays and costs for the tyre industry, with disadvantages also to customers and end-consumers.

Snow/Ice Performance: When an ice performance test and logo are available, either category of winter tyres, i.e. snowflake-marked tyres, and ice tyres (with their future official marking) should be entitled to only one extra logo on the EU label. This is important to ensure parity in information for users of winter tyres in the Continental part of Europe and in Scandinavia. This is the finding of a consumer survey that Goodyear conducted in 2015 on consumers’ reactions to possible winter tyre information on the official tyre label. An extra logo (either an ice performance or the existing three-peak-mountain snowflake logo) should be added to the EU tyre label on a voluntary basis, provided that tyres pass the legal thresholds for relevant performance, with official test methods.

Registration Database: Consumers already have comprehensive access to tyre label grades through various tools in the current system: physical stickers (for C1 and C2 tyres), and availability of the label grades in the digital systems of tyre manufacturers, distributors, and dealers. Market surveillance authorities already have opportunity to share information on market surveillance initiatives via the existing ICSMS tool. Therefore and in light of additional management and administrative cost involved we do not deem it necessary to introduce another database at European level.“ [Goodyear]

“Independent testing is needed in order to guarantee some degree of credibility of the label information.

A public database containing data of all independently tested tyre with results and divergences (pressure on the manufacturers).

A public database containing data of all sold tyres is needed (for information AND controlling purpose), please check “Swiss solution”, established by the TCS (www.tcs.ch): http://www.bfe.admin.ch/energieetikette/00886/04758/05701/index.html).

Label information of each tyre belongs ON that specific tyre: not all the “same” tyres really are the “same” (year or even season/week of the production, country of origin of components, tyres already mounted on new cars SERIOUSLY! vary from the “same” tyres one can purchase…).

IDEA: as manufacturer, you can “certify” your tyre if tested by an independent authority, add shiny symbol to the label.

Reconsider noise pictogram (smileys? :-) / :-I / :-( , add colour?)

Reconsider noise evaluation scheme: make it absolute, not relative to the tyre dimension. Loud is loud, e.g. >71dB. Why should a loud tyre outperform a quieter one just because it’s wider? In terms of health annoyance, this makes no sense.

Please NOTE: as long as label values cannot be trusted (aka today’s situation), it is impossible to enforce “hard” and efficient measures (e.g. tax cuts).” [FOEN]

“Criticism of the EU tire labelling:

Wet grip characteristics: Basically, it can be stated that direct mapping of EU tire label data is not or only partially possible within the ADAC tire test, although the specific test procedures (wet braking from 80 to 20 km / h) are largely similar , This means that the ranking determined in the ADAC tire test by direct comparison of several tire models under identical conditions does not or only partially corresponds to the EU tire label classification of these tires. This highlights a specific weakness of the EU tire label classification method. The manufacturer's own tests of tires for the EU tire label classification cannot be carried out under the same conditions as in the ADAC tire test. The tests are carried out at different locations on routes with different coefficients of friction and under different climatic conditions. Admitted limits are given for the friction coefficients of the roadways and the climatic conditions. Also, the properties of the test tracks were set in relation to each other by means of ring comparisons. Nevertheless, the allowed differences should be normalized by using correction factors. When comparing the ADAC tire test results with the tire label classifications, it does not always appear to be guaranteed that these corrections to the raw data can adequately compensate for the differences in the framework conditions mentioned. This applies in particular to the correction factors of temperature and road friction coefficient.

Rolling resistance / fuel efficiency: The rolling resistance and fuel efficiency data also show differences between the ADAC tire test ranking and the EU tire label classifications. However, there are sometimes significantly different measuring methods in this test point. While determining the fuel efficiency classification of the EU tire label, the rolling resistance coefficient of the test tire is determined on a certified chassis dynamometer. The ADAC directly measures the fuel consumption of the same vehicle (within one test dimension) with the different test tires under the same conditions, The tires are loaded with 50 to 60%. Regardless of these differences in measurement methods, it remains to be proposed to reduce the tire load in rolling resistance measurements from the current 80% to a more realistic 50 to 60%.” [ADAC] [Machine translated]

As a representative of the media industry, we are fundamentally critical of labelling requirements insofar as they concern advertisements. In recent years, such EU legal acts have repeatedly intervened in protected fundamental rights positions - the right to freedom of communication and the right to freedom of occupation - by compelling the advertising industry to provide compulsory information on all kinds of products. A widening of the requirements for compulsory information in advertisements leads to a situation that makes the advertising as a whole unattractive.

If the European Commission considers that there is a need for media education to promote tire labelling, this should not happen again as a result of the burdensome media industry. Even if labelling requirements in technical advertising media can make sense in order to provide interested consumers with information about the product, they must by no means be extended to classic advertising media. In our opinion, e.g. also the creation of an online database (see question 21), where all relevant information for consumers can be retrieved, an appropriate measure to relieve the provisions on compulsory disclosures.

A more fundamental, proportionate and, on top of that, strengthening the European media sector's access to awareness raising and information for citizens would also be information campaigns by the European Union or its member states on classical media channels on a private-sector basis. [Verband Österreichischer Zeitungen] [Machine translated]

“As a representative of the media industry, we are fundamentally critical of labelling requirements insofar as they concern advertisements. In recent years, such EU legal acts have repeatedly intervened in protected fundamental rights positions - the right to freedom of communication and the right to freedom of occupation - by compelling the advertising industry to provide compulsory information on all kinds of products. A widening of the requirements for compulsory information in advertisements leads to a situation that makes the advertising as a whole unattractive.

If the European Commission considers that there is a need for media education to promote tire labelling, this should not happen again as a result of the burdensome media industry. Even though labelling requirements in technical advertising media may well make sense in order to provide interested consumers with information about the product, they must by no means be extended to classic advertising media. In our opinion, e.g. also the creation of an online database (see question 21), where all relevant information for consumers can be retrieved, an appropriate measure to relieve the provisions on compulsory disclosures.

A more fundamental, proportionate and, on top of that, strengthening the European media sector's access to awareness raising and information for citizens would also be information campaigns by the European Union or its member states on classical media channels on a private-sector basis.” [Österreichischer Zeitschriften- und Fachmedienverband (ÖZV)] [Machine translated]

The evaluation and update of the Regulation on Tyre labelling is closely linked to the Regulation on General Safety (EC no 661/2009). In the Regulation on General Safety the tyre limits for fuel efficiency, wet grip and noise are set. In July 2017 the Netherlands ministry of environment sent a letter to 4 director generals of the European Commission asking to start working on strengthening of the tyre limits and interest the Commission to a number of other tyre related issues among which improving the tyre label. Q 7b: The information on the label is limited to letters and colours. One of the reasons to start an public awareness raising campaign in the Netherlands is that the label gives very little information. We propose more information on the label to encourage a discussion between people buying tyres and retail. See the background document ‘Tyres in Europe’ that was attached to the letter to the Commission for an example how this can be done. Having a label as proposed by the Netherland would almost make the campaign redundant.Q 9a/b: In the Netherlands the tyre label is mandatory both in the shops and on the internet. That is not a problem. Another thing is whether garages/workshops advise people when their car is brought for inspection/maintenance and new tyres are necessary. Then usually just a phone call is made and information on label values is not transmitted. The customer would in most cases not be informed about the tyre label of the new tyres when picking up the car.Q 16: See the background document Tyres in Europe attached to the letter to the Commission for an example how this can be done.Q 18: The Netherlands is greatly concerned about microplastics in the environment. We do favour a limit on abrasion of tyres but not on mileage. And we would like to see a proposal for that from the Commission. Yet, we are very reluctant to put anything on the tyre label. The most important argument would be that the consumer would look at any indicator regarding wear/durability/abrasion as an indicator for mileage. Tyre manufacturers could get a better label when they increase the tyre tread. And as a result the emission of microplastics would increase. See for more details the document Tyres in Europe.Q 19: See the comment to Q 18 above. An argument of a lesser importance is that the label would be more difficult to understand and to interpret. Including an indicator for snow/ice (see answer to Q16) would make five indicators on the label. A5th indicator on the tyre label would be too much information. “[Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management]

“Tyre labelling scheme should follow the same rules as any other energy label, notably be tested on consumers to check proper understanding when being designed/reviewed.